Introduction

Image classification is one of the central problems in computer vision, forming the foundation for applications such as facial recognition, medical diagnostics, autonomous driving, content-based image retrieval and surveillance [

1,

2,

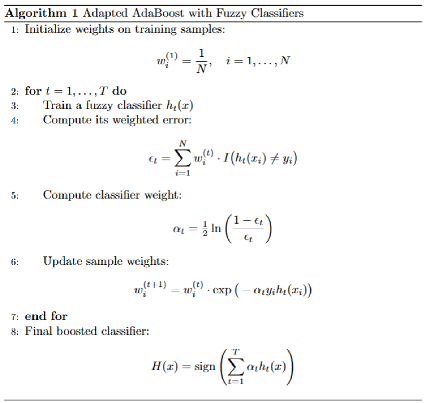

3]. For classifying images, the core task requires assigning a label to an input image based on the visual content present in it for example, a medical image labeled as “tumor” vs. “healthy tissue.” The general process of image classification is illustrated in

Figure 1, where raw images are transformed into features, processed by a classifier, and ultimately mapped to output labels. While the problem may appear straightforward, it presents several essential and inherent challenges. Images are high-dimensional data, often represented by thousands or even millions of pixel values. This high dimensionality increases computational complexity and makes it difficult to identify which features are truly relevant for classification. Also, there is always variability in visual features [

4]. For example, the same object can appear in different orientations, lighting conditions, scales, or levels of occlusion. Further to this, real-world images are more often corrupted by noise, compression artifacts, or background clutter, all of which further complicate the classification process.

Traditional machine learning approaches attempt to overcome these issues by extracting hand-crafted features and applying statistical classification techniques. However, such approaches can struggle when faced with uncertainty or imprecision in the data. This motivates the use of fuzzy logic, a framework designed to model approximate reasoning. Fuzzy classifiers can capture ambiguous or overlapping class boundaries, allowing them to handle the uncertainty inherent in visual data more effectively than rigid, rule-based methods. For instance, instead of forcing a pixel feature to belong strictly to a class, fuzzy logic allows for partial membership, reflecting the gradual transitions that often occur in real images.

At the same time, fuzzy classifiers on their own may not always achieve high accuracy, especially when dealing with very complex image distributions. This is where boosting becomes relevant. Boosting is an ensemble learning technique that combines multiple weak classifiers into a single, stronger classifier. By iteratively focusing on difficult-to-classify examples, boosting improves the overall performance and robustness of the system. When applied to fuzzy classifiers, boosting offers a promising way to build ensembles that are both resilient to uncertainty and capable of achieving high predictive accuracy.

The goal of this paper is to explore how boosting-generated fuzzy classifiers can be applied to visual object classification. By combining the interpretability and uncertainty-handling strengths of fuzzy logic with the accuracy-enhancing power of boosting, we aim to provide a framework that is well-suited for tackling the inherent challenges of image classification. Specifically, we will examine how this hybrid approach can address the issues of high-dimensionality, feature variability, and noise, thereby advancing the development of robust and adaptive computer vision systems.

In this work, we proposed a boosted fuzzy classification framework that went beyond a simple boosted classifier by embedding fuzzy logic into the base learners. This allowed the ensemble to better handle uncertainty and overlapping class boundaries, which are common in image data. The contributions of the paper can be summarized as follows:

We examined the role of different visual features such as color intensity, texture, shape descriptors, size, and edge properties, showing how they contributed to classification performance in an interpretable way.

We demonstrated that the framework was more robust to noise compared to conventional boosting methods, which are particularly valuable for real-world datasets such as medical images.

We validated the effectiveness of the approach through a comparative analysis with other classifiers, and although we focused on normal versus cancer cell classification, the method was designed to be generalizable to other visual recognition tasks.

The remainder of this paper was organized as follows. Section 2 reviewed related work on image classification, fuzzy classifiers, and boosting methods. Section 3 presented the proposed boosted fuzzy classification framework and explained the algorithmic details. Section 4 described the datasets, feature extraction process, and evaluation setup. Section 5 reported and discussed the experimental results. Finally, Section 6 concluded the paper and outlined possible directions for future research.

Literature Review

In this section, we discuss previous related work to image classification with a focus on three main areas:

(1) traditional feature-based methods such as SIFT descriptors and classical classifiers,

(2) approaches that apply fuzzy logic to handle uncertainty in visual features, and

(3) ensemble learning techniques, particularly boosting, that improve weak classifiers. We then highlight research that integrates these approaches, leading to the development of boosting-generated fuzzy classifiers.

Traditional Feature-Based Methods

These methods played a dominant role in early image classification systems before the rise of deep learning. Techniques such as the Scale-Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT) provided robust local descriptors that were invariant to scale, rotation, and illumination changes, making them highly effective for representing key points in images [

5].

Sometimes these descriptors are combined with Bag-of-Features models and fed into classical classifiers such as Support Vector Machines (SVMs) or k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN) to perform recognition tasks. For example, Scherer (2019) described how local features such as SIFT and SURF were critical for building automatic indexing and retrieval systems based on fuzzy rules and weak classifiers [

6]. Korytkowski et al. (2016) noted that simple local descriptors could be effectively leveraged within boosted fuzzy classifiers for fast image classification [

7,

8]. While such feature-based methods provided strong baselines and interpretability, they struggled with high intra-class variability and complex image distributions, motivating the shift toward ensemble and fuzzy logic based approaches.

Boosting arose as a powerful ensemble learning technique in the 1990s and has since become a staple in both research and practice. Islam et al. formalized gradient boosting and demonstrated its capacity to transform weak classifiers into strong ensembles by iteratively reweighting training samples and focusing on hard-to-classify instances [

9]. In environmental applications, Adhikari et al. (2014) demonstrated how applying boosting improved class mapping accuracy, highlighting its value in geospatial classification tasks [

10].

Boosting has also been applied to time-sensitive applications, such as Internet of Things (IoT)-based monitoring. Kasetty et al. (2024) implemented a gradient boosting regressor for air quality index prediction, showing superior forecasting accuracy compared to other regression techniques [

11]. Similarly, Murdhiono et al. (2025) employed extreme gradient boosting for audio-based mental health disorder detection, achieving significant improvements in binary classification problems [

12]. These examples illustrate the adaptability of boosting across domains, from regression in IoT systems to healthcare classification tasks.

Fuzzy Logic for Image Classification

Fuzzy logic offers a way to represent and process uncertainty through membership functions and fuzzy rules. Compared to traditional classifiers, fuzzy systems allow elements to belong partially to multiple classes, capturing the ambiguity often present in real-world data. The early applications of fuzzy logic in classification used simple membership functions, but research has expanded into more sophisticated models.

Azam et al. (2021) proposed generating type-1 fuzzy triangular and trapezoidal membership functions to improve classification accuracy [

13]. They emphasized the importance of designing appropriate membership functions, as the choice of shape like Gaussian, triangular, or trapezoidal which directly affects classifier performance. Belhadj (2022) introduced fuzzy simple linear regression based on Gaussian membership functions, presenting an alternative to ordinary least squares for handling uncertainty in regression problems [

14]. Similarly, Leandry et al. (2022) applied fuzzy arithmetic operations using α-cuts for Gaussian membership functions, demonstrating the usefulness of fuzzy methods in classification and information processing [

15].

The adoption of fuzzy systems in image analysis has also been seen in Earth observation. Moola et al. (2021) used fuzzy classification of Dynamic Time Warping distances from Sentinel-1A images for vegetable mapping [

16]. Their approach assigned fuzzy memberships to pixels, showcasing the ability of fuzzy systems to model gradual transitions in land cover. Wang et al. (2022) extended fuzzy systems to remote sensing by developing an interval type-2 fuzzy neural network combined with Gaussian regression, achieving high-resolution land cover classification [

17]. Khairuddin et al. (2021) presented a structured literature review on clustering-based interval fuzzy type-2 membership functions, highlighting their role in complex classification tasks such as cervical spondylosis diagnosis [

18]. Cholleti et al. (2020) extended this work by developing fuzzy rule-based retrieval systems enhanced by boosting and metaheuristic optimization [

19].

Ensemble Learning for Classification

Ensemble classification has emerged as a powerful strategy in machine learning and computer vision, addressing the limitations of individual classifiers by combining multiple models to achieve higher predictive accuracy, robustness, and generalization. The core idea of ensemble methods is that a collection of diverse, weak, or moderately accurate learners can, when aggregated, outperform any single model alone [

20]. Techniques such as bagging, boosting, stacking, and voting represent the most widely used ensemble approaches, each differing in how base classifiers are trained and combined [

21]. Bagging reduces variance through resampling, while boosting sequentially emphasizes difficult-to-classify samples, and stacking exploits meta-learners to integrate diverse classifiers [

22]. These approaches have been successfully applied across domains, including disease prediction [

23], lung cancer prognosis [

24], and diabetic retinopathy severity grading [

25], where ensemble models consistently outperformed single classifiers. In the medical imaging context, [

26] demonstrated that ensemble learning, particularly when combined with deep convolutional neural networks, significantly improved classification accuracy and reliability. Beyond healthcare, ensemble learning has also been leveraged for intrusion detection in IoT and smart grid security, where class imbalance and heterogeneous data pose major challenges [

27]. Collectively, these studies underline the versatility of ensemble methods, reinforcing their role as a cornerstone in modern classification pipelines.

Summary of Literature Review and Research Gap

While boosted fuzzy classifiers have shown promising results, several research gaps remain. The design of fuzzy membership functions still relies on heuristics, with no standard approach across tasks [

28,

29,

30]. Most studies focus on narrow datasets, limiting generalizability, and boosting, while improving accuracy, often increases computational cost [

31,

32,

33]. Finally, the trade-off between interpretability and predictive power remains unresolved [

34,

35,

36]. Future progress depends on automatic membership function generation, broader benchmarks, and hybrid designs that balance transparency with performance [

37,

38,

39].

Methodology

This section presents the proposed boosted fuzzy classification framework for visual object recognition. The framework integrates fuzzy logic for handling uncertainty with boosting techniques for improving classification accuracy [

40]. The methodology is organized into the following steps: feature extraction, fuzzy rule generation, boosting of fuzzy classifiers, and final decision making.

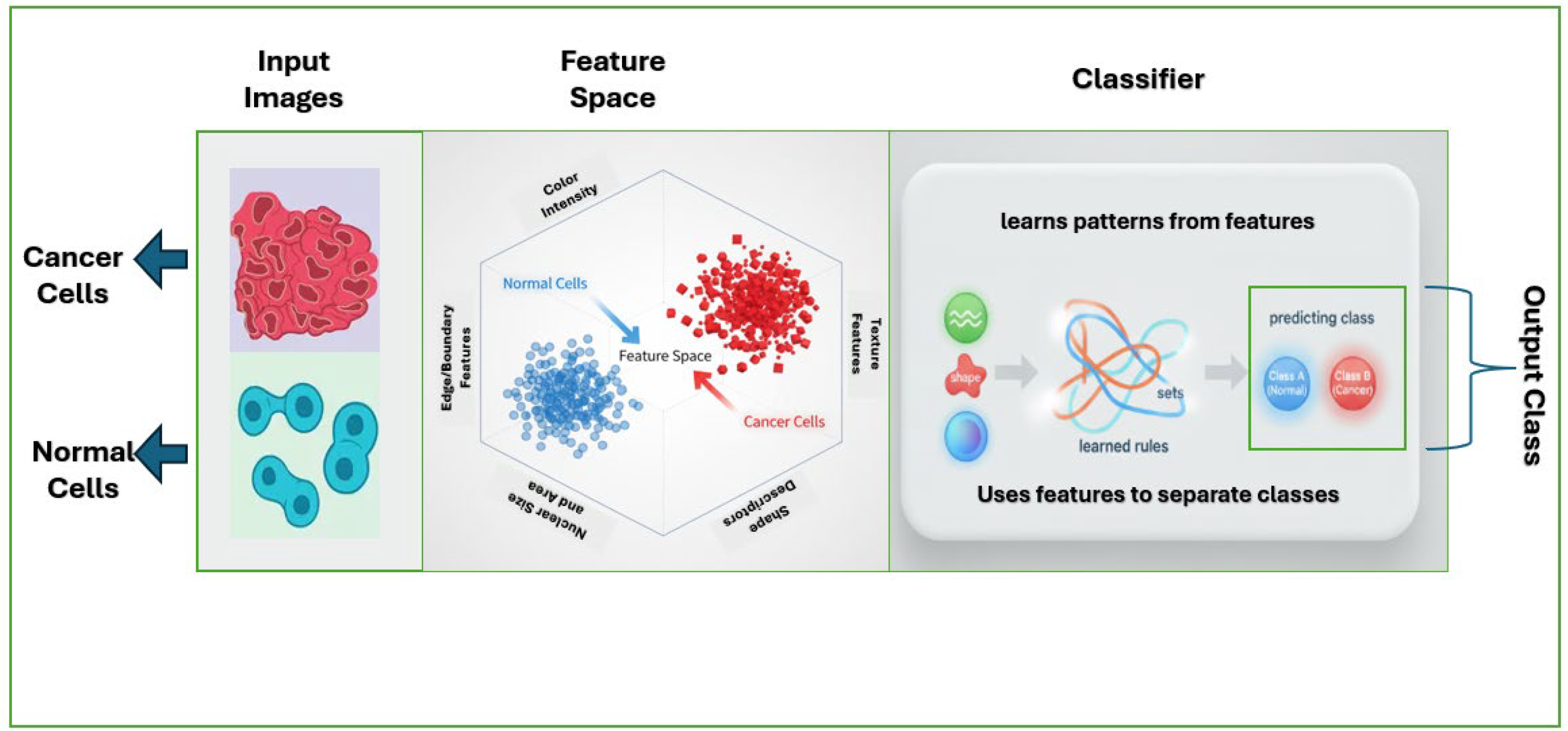

Fuzzy Membership Functions

To handle uncertainty in the extracted features, fuzzy membership functions [

43] are applied. Each feature dimension is mapped into linguistic terms such as

Low,

Medium, or

High. Common membership functions include triangular, trapezoidal, and Gaussian.

A Gaussian membership function for a feature value

is defined as:

where

is the center and

controls the spread.

A triangular membership function is defined as:

Figure 3 shows the graphs of Gaussian vs. Triangular membership functions applied to a feature dimension.

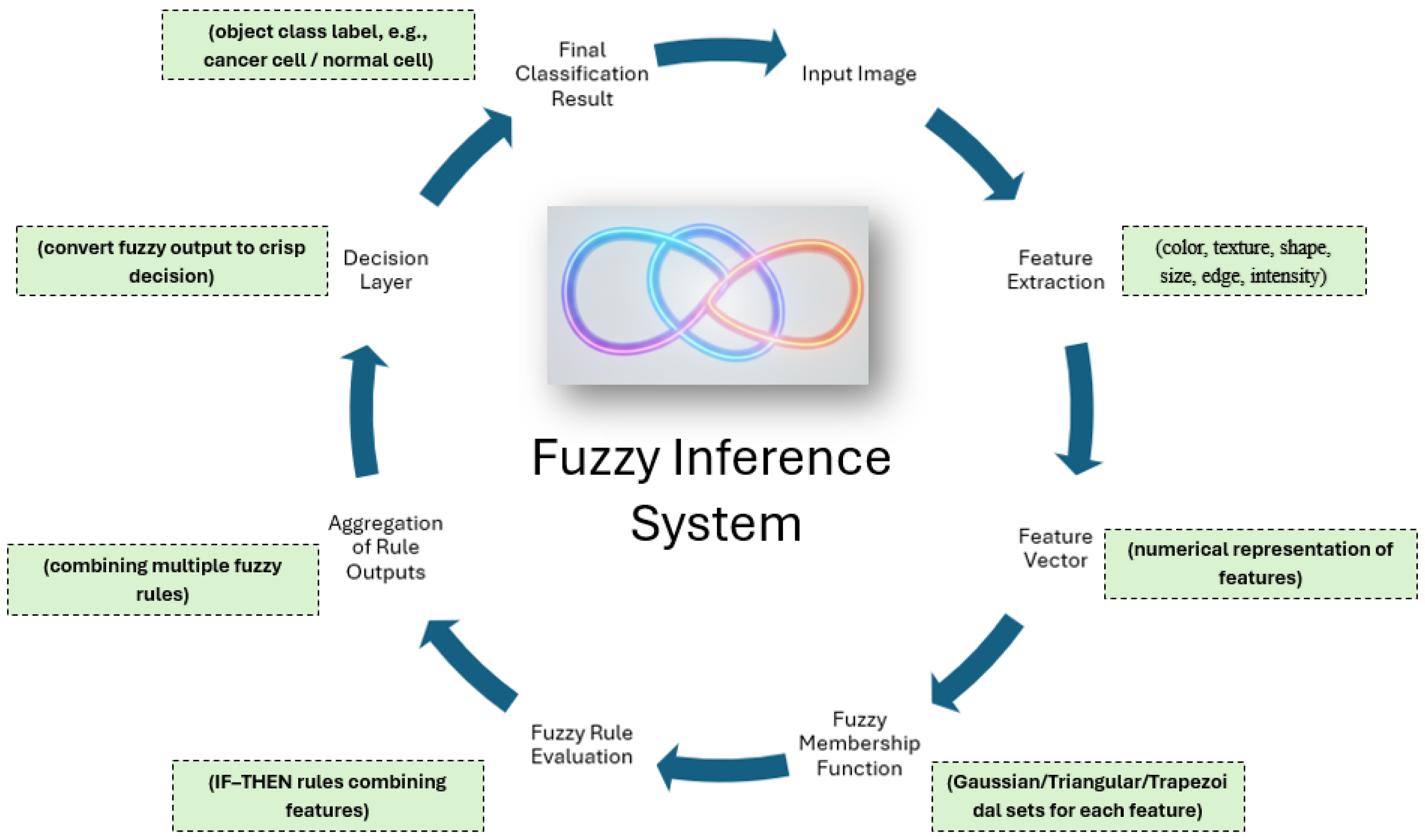

Fuzzy Rule Generation

Fuzzy rules are constructed to classify patterns into different classes. A typical fuzzy rule has the form:

where

are fuzzy sets associated with feature values and

is the class label.

The firing strength of a rule is computed as:

where

denotes the membership of feature

to fuzzy set

The predicted class of an input is the one with the highest aggregated firing strength across all rules.

Figure 4 illustrates how an image feature vector activates fuzzy rules leading to classification.

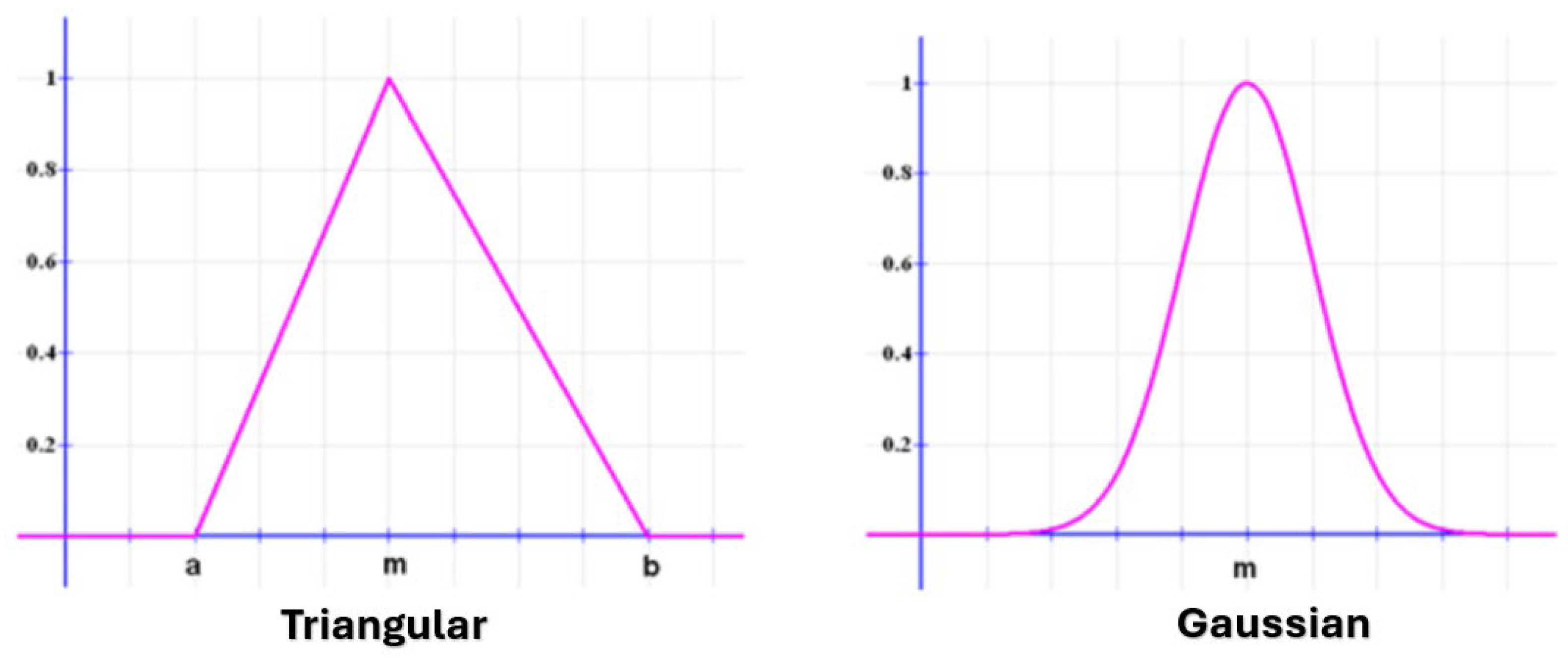

Boosting Fuzzy Classifiers

Boosting is employed to enhance the performance of fuzzy classifiers. Instead of relying on a single fuzzy rule base, multiple weak fuzzy classifiers are trained sequentially. Each classifier focuses on examples misclassified by the previous ones.

The AdaBoost algorithm is follows:

Decision Making

The final classification decision is based on the ensemble of boosted fuzzy classifiers. For an input image, each fuzzy classifier produces a decision, which is weighted by its corresponding boosting coefficient. The aggregated decision determines the predicted label.

This step balances fuzzy interpretability with the accuracy of boosting, offering both transparency and predictive strength.

Results

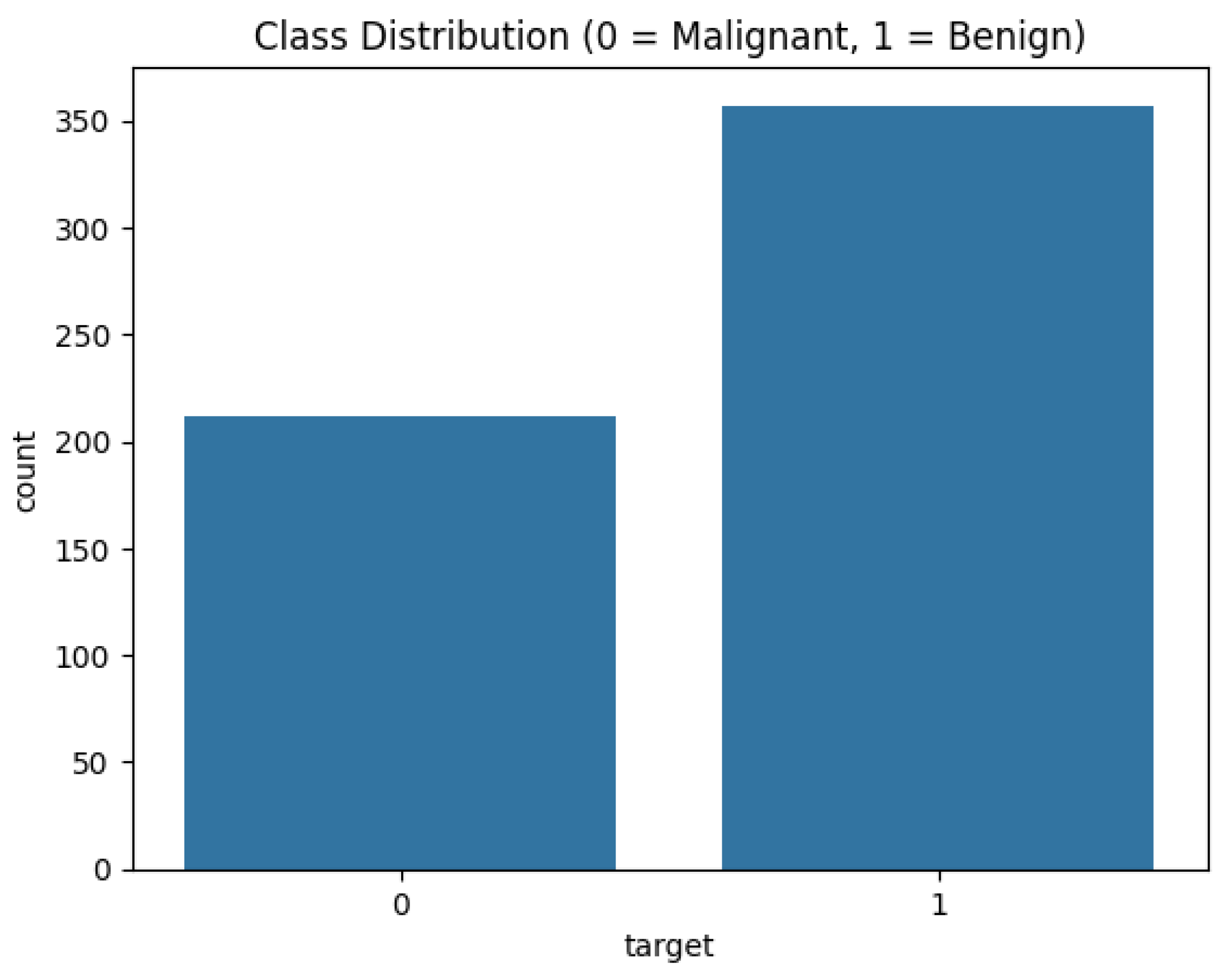

To begin the results analysis, we first explore the dataset through basic visualizations. The class distribution plot (

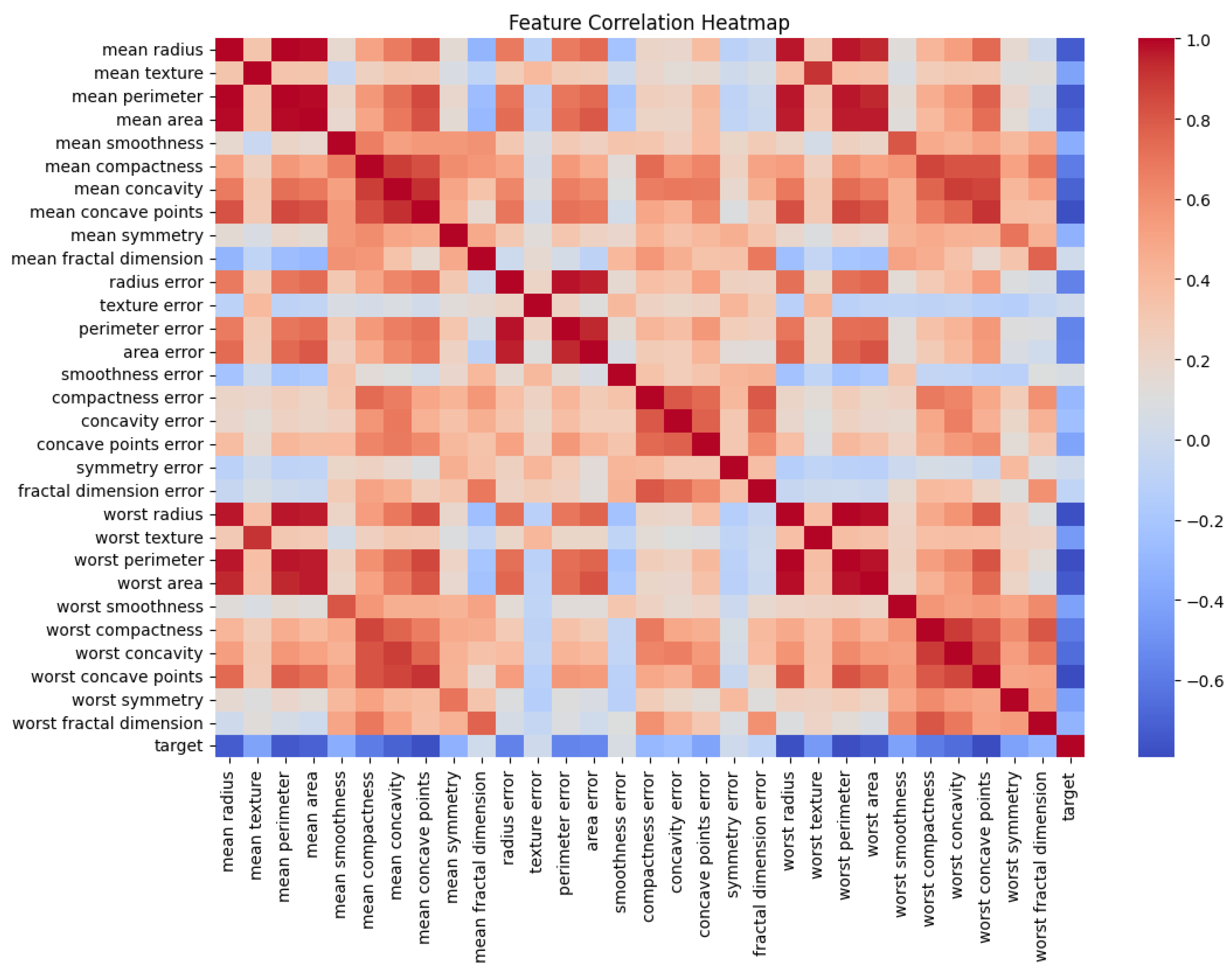

Figure 5) clearly shows the balance between malignant (0) and benign (1) cases, which is essential for understanding potential bias in the classification process. A relatively balanced dataset ensures that classifiers are not overly skewed toward predicting the majority class, thereby providing a fairer evaluation of model performance. In addition, the feature correlation heatmap (

Figure 6) offers insights into the interdependence of attributes. Strongly correlated features may carry redundant information, while weakly correlated ones highlight unique predictive signals. These preliminary visualizations not only establish the data characteristics but also provide context for interpreting the subsequent machine learning results.

The performance of the proposed fuzzy classifier was evaluated alongside baseline decision tree and boosted decision tree models using the breast cancer dataset. All input features were normalized to the range [0,1] [0,1] [0,1] prior to training to facilitate the fuzzy rule definitions. Three metrics were used for evaluation: overall accuracy, confusion matrices, and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis.

Table 1 summarizes the classification accuracy of the three models. The baseline decision tree achieved an accuracy of

0.90, demonstrating that a shallow decision tree is already capable of capturing relevant discriminative patterns in the dataset. Boosting the decision tree further improved performance, yielding an accuracy of

0.94, which reflects the benefit of ensemble learning in reducing bias and variance. In contrast, the boosted fuzzy classifier achieved an accuracy of

0.70, which is substantially lower than both decision tree models.

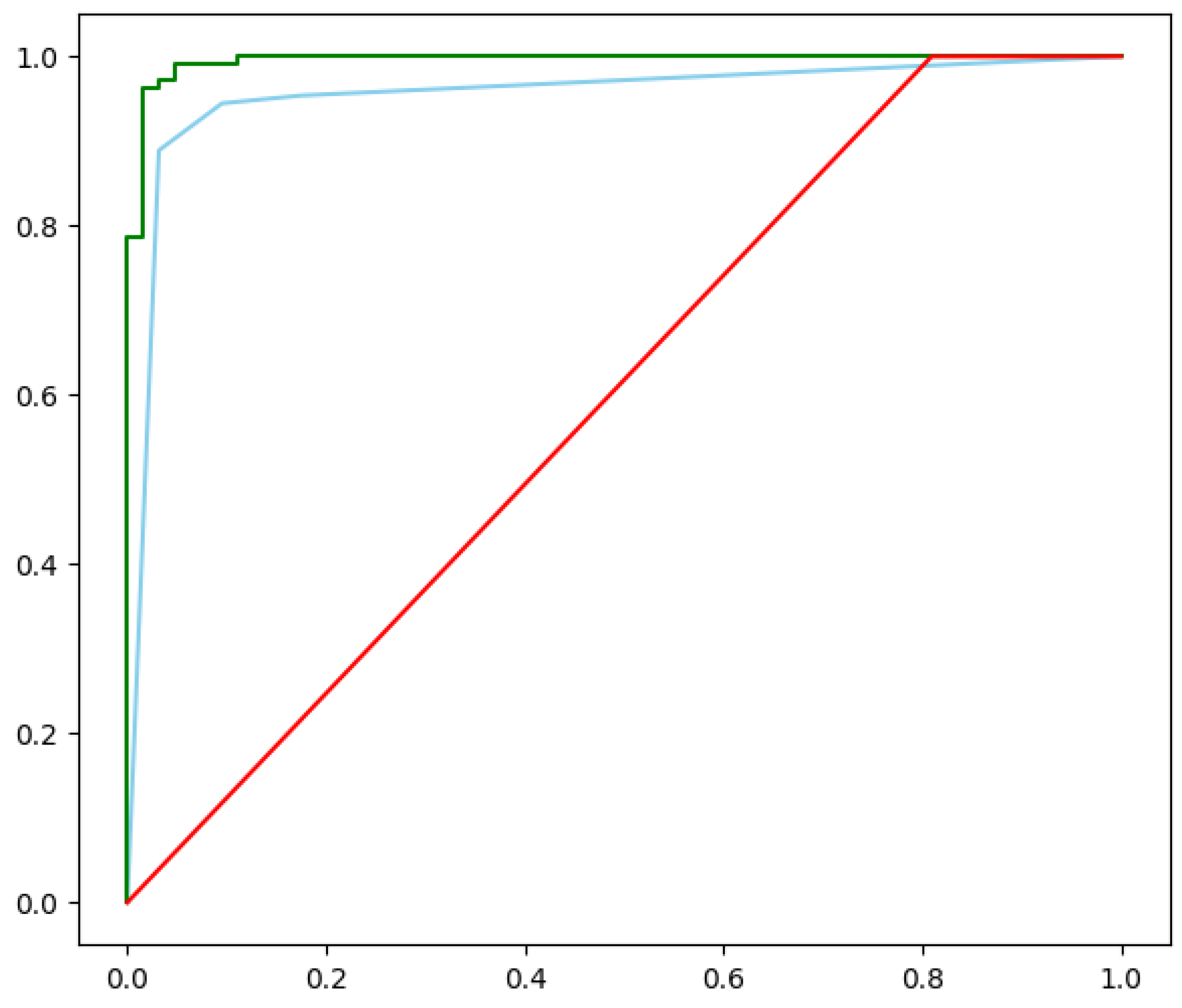

To better illustrate classifier behavior,

Figure 7 presents the ROC curves for all three models. The boosted decision tree achieved the highest area under the curve (AUC = 0.97), followed by the baseline decision tree (AUC = 0.95). The boosted fuzzy classifier obtained a considerably lower AUC of 0.75, consistent with its reduced accuracy. This indicates that, while fuzzy membership rules can provide interpretable decision boundaries, their simple voting structure was insufficient to capture the complexity of the breast cancer dataset.

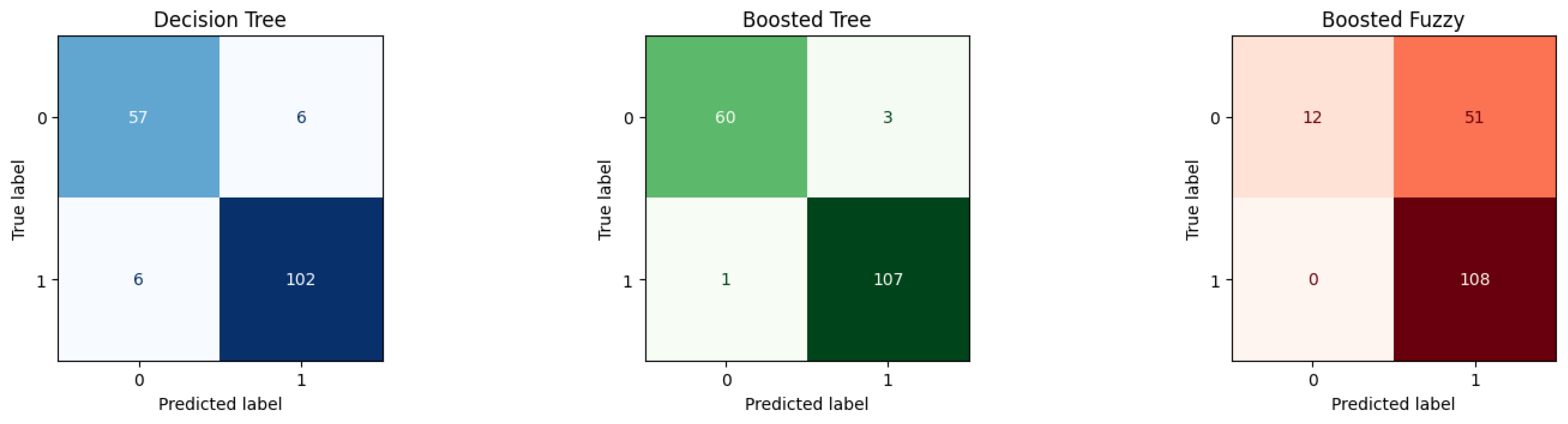

The confusion matrices in

Figure 8 further confirm these findings. Both decision tree models correctly classified the majority of malignant and benign cases, with the boosted variant reducing false negatives compared to the baseline. Conversely, the fuzzy boosted classifier misclassified a larger proportion of benign samples, suggesting that its triangular membership functions require refinement or the inclusion of additional features to achieve competitive performance.

The results demonstrate that ensemble tree-based approaches provide superior predictive performance on the breast cancer dataset, while the boosted fuzzy approach, in its current form, performs below state-of-the-art baselines. Nonetheless, the fuzzy classifier remains valuable as an interpretable alternative, and its performance could potentially be enhanced by optimizing membership functions, expanding the feature set, or integrating hybrid fuzzy–neural learning schemes. Including the fuzzy model, even with modest accuracy, is important because it offers a different perspective on decision-making that emphasizes interpretability over raw predictive power. This distinction is particularly relevant in sensitive domains like healthcare, where transparency and human-understandable reasoning can complement purely statistical models. Moreover, reporting weaker results provides valuable insights into the limitations of fuzzy systems when applied to high-dimensional, complex datasets. Such transparency not only strengthens the credibility of the study but also guides future researchers to refine fuzzy-based methods, explore alternative membership function designs, or integrate hybrid ensembles that balance accuracy with interpretability. In this way, the fuzzy classifier contributes to a more comprehensive evaluation framework rather than being viewed solely as an underperforming model.

Conclusion

This study evaluated the effectiveness of decision trees, boosted trees, and a boosted fuzzy classifier for breast cancer prediction. The results consistently showed that ensemble tree-based methods achieved the highest predictive performance, confirming their robustness and reliability on biomedical datasets. While the boosted fuzzy classifier underperformed in terms of accuracy, its inclusion provided important insights into interpretability and the potential role of fuzzy reasoning in medical decision support systems. These findings highlight that high-performance models such as boosted decision trees are suitable for immediate application, whereas fuzzy-based models remain promising for future exploration, particularly when interpretability and transparent decision-making are prioritized. Further research may focus on refining fuzzy membership functions, hybridizing fuzzy logic with deep learning, or leveraging feature engineering to bridge the current performance gap. Ultimately, this comparative study underscores the importance of balancing predictive accuracy with model interpretability in medical AI systems.

References

- Alourani, A., Ashfaq, F., Jhanjhi, N. Z., & Ali Khan, N. (2023). BiLSTM-and GNN-Based Spatiotemporal Traffic Flow Forecasting with Correlated Weather Data. Journal of Advanced Transportation, 2023(1), 8962283. [CrossRef]

- Turay, T., & Vladimirova, T. (2022). Toward performing image classification and object detection with convolutional neural networks in autonomous driving systems: A survey. IEEE access, 10, 14076-14119. [CrossRef]

- Sergyan, S. (2008, January). Color histogram features based image classification in content-based image retrieval systems. In 2008 6th international symposium on applied machine intelligence and informatics (pp. 221-224). IEEE.

- Alshudukhi, K. S. S., Ashfaq, F., Jhanjhi, N. Z., & Humayun, M. (2024). Blockchain-enabled federated learning for longitudinal emergency care. IEEE Access, 12, 137284-137294. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q., & Wang, X. (2018, June). Image classification based on SIFT and SVM. In 2018 IEEE/ACIS 17th International Conference on Computer and Information Science (ICIS) (pp. 762-765). IEEE.

- Ashfaq, F., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Khan, N. A., Javaid, D., Masud, M., & Shorfuzzaman, M. (2025). Enhancing ECG Report Generation With Domain-Specific Tokenization for Improved Medical NLP Accuracy. IEEE Access. [CrossRef]

- Azhar, R., Tuwohingide, D., Kamudi, D., & Suciati, N. (2015). Batik image classification using SIFT feature extraction, bag of features and support vector machine. Procedia Computer Science, 72, 24-30. [CrossRef]

- Korytkowski, M., Scherer, R., Szajerman, D., Połap, D., & Woźniak, M. (2020, July). Efficient visual classification by fuzzy rules. In 2020 IEEE international conference on fuzzy systems (FUZZ-IEEE) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Korytkowski, M., Šenkeřík, R., Scherer, M. M., Angryk, R. A., Kordos, M., & Siwocha, A. (2020). Efficient image retrieval by fuzzy rules from boosting and metaheuristic. Journal of Artificial Intelligence and Soft Computing Research. [CrossRef]

- Korytkowski, M., Scherer, R., & Szajerman, D. (2020). Efficient visual classification by fuzzy rules. IEEE Conference on Fuzzy Systems.

- Islam, S. S., Haque, M. S., Miah, M. S. U., Sarwar, T. B., & Nugraha, R. (2022). Application of machine learning algorithms to predict the thyroid disease risk: an experimental comparative study. PeerJ Computer Science, 8, e898. [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, K., Minasny, B., Greve, M.B., & Greve, M.H. (2014). Constructing a soil class map of Denmark based on the FAO legend using digital techniques. Geoderma. Elsevier.

- Kasetty, S.B., Margret, I.N., & Sudha, N. (2024). Internet of Things based air quality index monitoring using XGradient Boosting regressor model. In Multifaceted Approaches for Smart Environments. Taylor & Francis.

- Murdhiono, W.R., Riska, H., Khasanah, N., et al. (2025). Mentalix: stepping up mental health disorder detection using Gaussian CNN algorithm. Iran Journal of Computer Science. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Azam, M.H., Hasan, M.H., Kadir, S.J.A., et al. (2021). Prediction of sunspots using fuzzy logic: A triangular membership function-based fuzzy C-Means approach. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence. ResearchGate.

- Belhadj, B. (2022). Fuzzy simple linear regression using Gaussian membership functions minimization problem. Journal of Fuzzy Extension and Applications.

- Leandry, L., Sosoma, I., & Koloseni, D. (2022). Basic fuzzy arithmetic operations using α–cut for the Gaussian membership function. Journal of Fuzzy Extension and Applications.

- Moola, W.S., Bijker, W., Belgiu, M., & Li, M. (2021). Vegetable mapping using fuzzy classification of Dynamic Time Warping distances from Sentinel-1A images. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation. Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., Wang, X., Wu, D., Kuang, M., & Li, Z. (2022). Meticulous land cover classification of high-resolution images based on interval type-2 fuzzy neural network with Gaussian regression model. Remote Sensing. MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Khairuddin, S.H., Hasan, M.H., Hashmani, M.A., & Azam, M.H. (2021). Generating clustering-based interval fuzzy type-2 triangular and trapezoidal membership functions: A structured literature review. Symmetry. MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Cholleti, S.R., Goldman, S.A., Blum, A., et al. (2009). Veritas: Combining expert opinions without labeled data. International Journal on Artificial Intelligence Tools. World Scientific. [CrossRef]

- Mienye, I. D., & Sun, Y. (2022). A survey of ensemble learning: Concepts, algorithms, applications, and prospects. Ieee Access, 10, 99129-99149. [CrossRef]

- Dasari, A. K., Biswas, S. K., Thounaojam, D. M., Devi, D., & Purkayastha, B. (2023, March). Ensemble learning techniques and their applications: an overview. In International Conference on Communications and Cyber Physical Engineering 2018 (pp. 897-912). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

- Mahajan, P., Uddin, S., Hajati, F., & Moni, M. A. (2023, June). Ensemble learning for disease prediction: A review. In Healthcare (Vol. 11, No. 12, p. 1808). MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Mamun, M., Farjana, A., Al Mamun, M., & Ahammed, M. S. (2022, June). Lung cancer prediction model using ensemble learning techniques and a systematic review analysis. In 2022 IEEE World AI IoT Congress (AIIoT) (pp. 187-193). IEEE.

- Müller, D., Soto-Rey, I., & Kramer, F. (2022). An analysis on ensemble learning optimized medical image classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Ieee Access, 10, 66467-66480. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M., Singhal, S., Shekhar, S., Sharma, B., & Srivastava, G. (2022). Optimized stacking ensemble learning model for breast cancer detection and classification using machine learning. Sustainability, 14(21), 13998. [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, A., & Lohiya, R. (2023). Attack classification of imbalanced intrusion data for IoT network using ensemble-learning-based deep neural network. IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 10(13), 11888-11895. [CrossRef]

- Sikder, N., Masud, M., Bairagi, A. K., Arif, A. S. M., Nahid, A. A., & Alhumyani, H. A. (2021). Severity classification of diabetic retinopathy using an ensemble learning algorithm through analyzing retinal images. Symmetry, 13(4), 670. [CrossRef]

- N. Jhanjhi, “Comparative Analysis of Frequent Pattern Mining Algorithms on Healthcare Data,” 2024 IEEE 9th International Conference on Engineering Technologies and Applied Sciences (ICETAS), Bahrain, Bahrain, 2024, pp. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Jhanjhi, N.Z. (2025). Investigating the Influence of Loss Functions on the Performance and Interpretability of Machine Learning Models. In: Pal, S., Rocha, Á. (eds) Proceedings of 4th International Conference on Mathematical Modeling and Computational Science. ICMMCS 2025. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol 1399. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- JingXuan, C., Tayyab, M., Muzammal, S. M., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Ray, S. K., & Ashfaq, F. (2024, November). Integrating AI with Robotic Process Automation (RPA): Advancing Intelligent Automation Systems. In 2024 IEEE 29th Asia Pacific Conference on Communications (APCC) (pp. 259-265). IEEE.

- Faisal, A., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Ashraf, H., Ray, S. K., & Ashfaq, F. (2025). A Comprehensive Review of Machine Learning Models: Principles, Applications, and Optimal Model Selection. Authorea Preprints.

- Maleki, F., Ovens, K., Gupta, R., Reinhold, C., Spatz, A., & Forghani, R. (2022). Generalizability of machine learning models: quantitative evaluation of three methodological pitfalls. Radiology: Artificial Intelligence, 5(1), e220028. [CrossRef]

- Tran, A. T., Zeevi, T., & Payabvash, S. (2025). Strategies to improve the robustness and generalizability of deep learning segmentation and classification in neuroimaging. BioMedInformatics, 5(2), 20. [CrossRef]

- Javed, D., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Ashfaq, F., Khan, N. A., Das, S. R., & Singh, S. (2024, July). Student Performance Analysis to Identify the Students at Risk of Failure. In 2024 International Conference on Emerging Trends in Networks and Computer Communications (ETNCC) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Attaullah, M., Ali, M., Almufareh, M. F., Ahmad, M., Hussain, L., Jhanjhi, N., & Humayun, M. (2022). Initial stage COVID-19 detection system based on patients’ symptoms and chest X-ray images. Applied Artificial Intelligence, 36(1), 2055398. [CrossRef]

- Humayun, M., Khalil, M. I., Almuayqil, S. N., & Jhanjhi, N. Z. (2023). Framework for detecting breast cancer risk presence using deep learning. Electronics, 12(2), 403. [CrossRef]

- Bora, P. S., Sharma, S., Batra, I., Malik, A., & Ashfaq, F. (2024, July). Identification and classification of rare medicinal plants. In 2024 International Conference on Emerging Trends in Networks and Computer Communications (ETNCC) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Ashfaq, F., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Khan, N. A., Muzafar, S., & Das, S. R. (2024, March). CrimeScene2Graph: Generating Scene Graphs from Crime Scene Descriptions Using BERT NER. In International Conference on Computational Intelligence in Pattern Recognition (pp. 183-201). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

- Xie, L., Tian, Q., Wang, J., & Zhang, B. (2015, April). Image classification with Max-SIFT descriptors. In International conference on acoustics, speech and signal processing.

- Du, Y., Hooley, R. J., Lewin, J., & Dvornek, N. C. (2024, May). Sift-dbt: Self-supervised initialization and fine-tuning for imbalanced digital breast tomosynthesis image classification. In 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI) (pp. 1-5). IEEE.

- Ahmed, V. A., Jouini, K., Tuama, A., & Korbaa, O. (2024). A fusion approach for enhanced remote sensing image classification. Proceedings Copyright, 554, 561.

- Feilong, Q., Khan, N. A., Jhanjhi, N. Z., Ashfaq, F., & Hendrawati, T. D. (2025). Improved YOLOv5 Lane Line Real Time Segmentation System Integrating Seg Head Network. Engineering Proceedings, 107(1), 49.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).