Submitted:

26 September 2025

Posted:

29 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Gut Microbiota

2. Gut-Brain Axis (GBA)

2.1. Microbiota and Neurotransmitters Synthesis

2.2. Microbiota and Enteroendocrine Signaling

2.3. Microbiota Metabolites

3. Barriers to Microbiota-Gut-Brain (MGB) Signaling

3.1. Intestinal Barrier

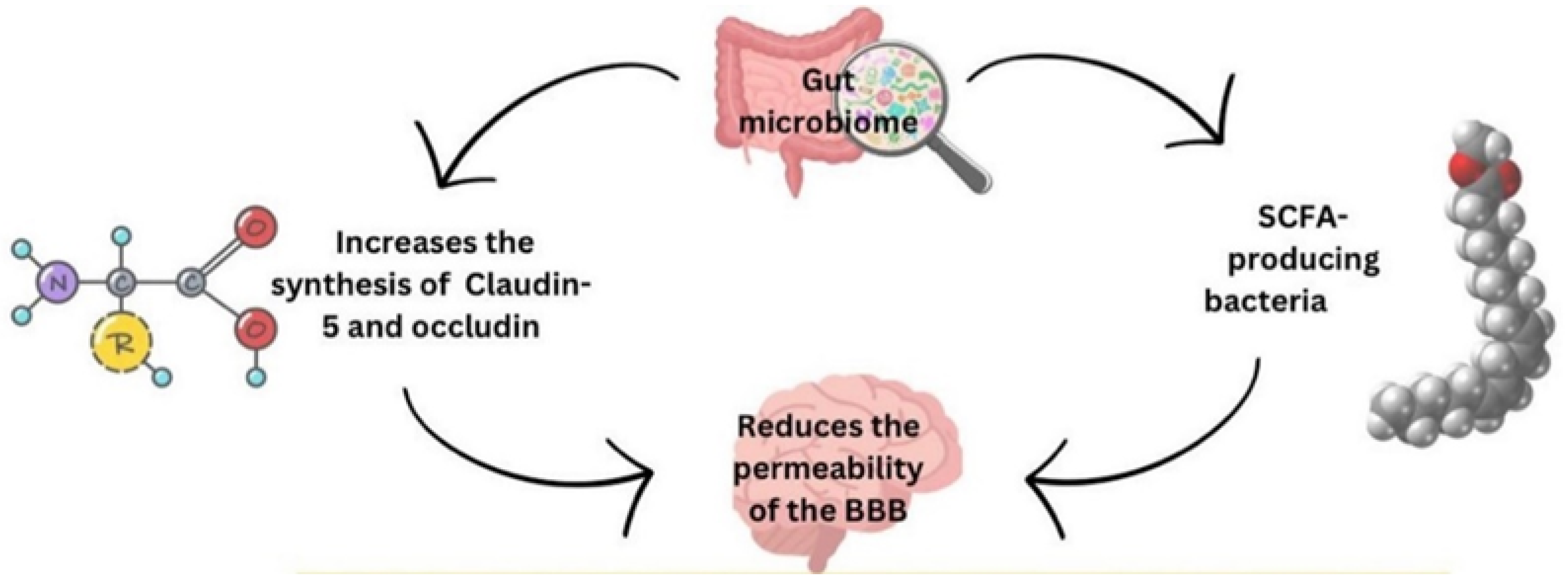

3.2. Blood–Brain Barrier (BBB)

4. Role of the Gut Microbiota in Health

5. Role of GBA in Health

6. Dysbiosis of the Gut Microbiome Contributes to Metabolic Dysfunction

6.1. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)

6.2. Bile Acids

6.3. Short Chain Fatty Acid (SCFAs)

6.4. Gut Hormone Secretion

6.5. Microbial Synthesis of Amino Acids

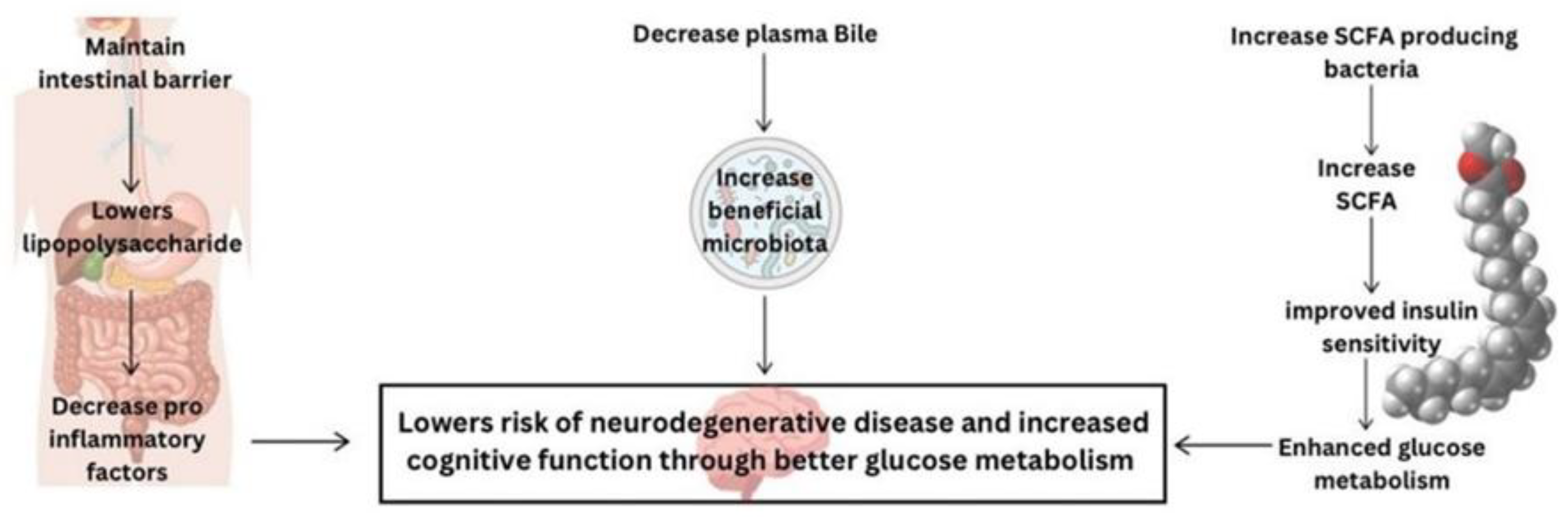

7. The Role of Metformin in Modulating the Gut Microbiome

7.1. Metformin Mechanism of Action

7.2. Effects of Metformin on Cognition

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- de Vos WM, Tilg H, Van Hul M, Cani PD: Gut microbiome and health: mechanistic insights. Gut 2022, 71, 1020–1032. [CrossRef]

- Chiang MC, Cheng YC, Chen SJ, Yen CH, Huang RN: Metformin activation of AMPK-dependent pathways is neuroprotective in human neural stem cells against Amyloid-beta-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. Exp. Cell Res. 2016, 347, 322–331. [CrossRef]

- Arumugam M, Raes J, Pelletier E, Le Paslier D, Yamada T, Mende DR, Fernandes GR, Tap J, Bruls T, Batto JM et al: Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature 2011, 473, 174–180. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang X, Huang H, Zhu Y, Li S, Zhang P, Jiang J, Xi C, Wu L, Gao X, Fu Y et al: Metformin acts on the gut-brain axis to ameliorate antipsychotic-induced metabolic dysfunction. Biosci. Trends 2021, 15, 321–329. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khosravi F, Amiri Z, Masouleh NA, Kashfi P, Panjizadeh F, Hajilo Z, Shanayii S, Khodakarim S, Rahnama L: Shoulder pain prevalence and risk factors in middle-aged women: A cross-sectional study. Journal of bodywork and movement therapies 2019, 23, 752–757. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller PA, Schneeberger M, Matheis F, Wang P, Kerner Z, Ilanges A, Pellegrino K, Del Marmol J, Castro TBR, Furuichi M et al: Microbiota modulate sympathetic neurons via a gut-brain circuit. Nature 2020, 583, 441–446.

- Carabotti M, Scirocco, A., Maselli, M.A. and Severi, C.: The gut-brain axis: interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems. Annals of Gastroenterology 2015, 28(2):203.

- Mitrea L, Nemes SA, Szabo K, Teleky BE, Vodnar DC: Guts Imbalance Imbalances the Brain: A Review of Gut Microbiota Association With Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders. Front Med (Lausanne), 2022, 9:813204.

- Dong TS, Mayer E: Advances in Brain-Gut-Microbiome Interactions: A Comprehensive Update on Signaling Mechanisms, Disorders, and Therapeutic Implications. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 18, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Tsigos C, Chrousos GP: Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, neuroendocrine factors and stress. J. Psychosom. Res. 2002, 53, 865–871. [CrossRef]

- Foster JA MNK: Gut-brain axis: how the microbiome influences anxiety and depression. Trends Neurosci. 2013, 36, 305–312. [CrossRef]

- Mayer EA, Savidge T, Shulman RJ: Brain-gut microbiome interactions and functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, 1500–1512. [CrossRef]

- Martin CR, Osadchiy V, Kalani A, Mayer EA: The Brain-Gut-Microbiome Axis. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 6, 133–148. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holzer P, Farzi A: Neuropeptides and the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Advances in experimental medicine and biology 2014, 817:195-219.

- Lyte M: Microbial endocrinology in the microbiome-gut-brain axis: how bacterial production and utilization of neurochemicals influence behavior. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003726.

- Obrenovich M, Sankar Chittoor Mana, T., Rai, H., Shola, D., Sass, C., McCloskey, B. and Levison, B.S.: Recent findings within the microbiota–gut–brain–endocrine metabolic interactome. Pathology and Laboratory Medicine International.

- Ignatow G: The microbiome-gut-brain and social behavior. Journal for the Theory of Social. Behaviour 2022, 52, 164–182. [CrossRef]

- Sorboni SG, Moghaddam HS, Jafarzadeh-Esfehani R, Soleimanpour S: A Comprehensive Review on the Role of the Gut Microbiome in Human Neurological Disorders. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2022, 35, e0033820.

- Cryan JF, O’Riordan KJ, Sandhu K, Peterson V, Dinan TG: The gut microbiome in neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 179–194. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Xu J, Chen Y: Regulation of Neurotransmitters by the Gut Microbiota and Effects on Cognition in Neurological Disorders. Nutrients 2021, 13.

- Boyd CA: Amine uptake and peptide hormone secretion: APUD cells in a new landscape. J Physiol, 2001, 531(Pt 3):581.

- Worthington JJ, Reimann F, Gribble FM: Enteroendocrine cells-sensory sentinels of the intestinal environment and orchestrators of mucosal immunity. Mucosal Immunol. 2018, 11, 3–20. [CrossRef]

- Levy M, Thaiss CA, Elinav E: Metabolites: messengers between the microbiota and the immune system. Genes. Dev. 2016, 30, 1589–1597. [CrossRef]

- Yu Y, Yang W, Li Y, Cong Y: Enteroendocrine Cells: Sensing Gut Microbiota and Regulating Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2020, 26, 11–20. [CrossRef]

- Morbe UM, Jorgensen PB, Fenton TM, von Burg N, Riis LB, Spencer J, Agace WW: Human gut-associated lymphoid tissues (GALT); diversity, structure, and function. Mucosal Immunol. 2021, 14, 793–802. [CrossRef]

- Man AWC, Zhou Y, Xia N, Li H: Involvement of Gut Microbiota, Microbial Metabolites and Interaction with Polyphenol in Host Immunometabolism. Nutrients 2020, 12.

- Duan T, Du Y, Xing C, Wang HY, Wang RF: Toll-Like Receptor Signaling and Its Role in Cell-Mediated Immunity. Front Immunol, 2022, 13:812774.

- Yiu JH, Dorweiler B, Woo CW: Interaction between gut microbiota and toll-like receptor: from immunity to metabolism. J Mol Med (Berl) 2017, 95, 13–20. [CrossRef]

- Carlson NG WW, Chen J, Bacchi A, Rogers SW, Gahring LC: Inflammatory cytokines IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α impart neuroprotection to an excitotoxin through distinct pathways. J. Immunol. 1999, 163, 3963–3968. [CrossRef]

- Schwarz MJ: Cytokines, neurophysiology, neuropsychology, and psychiatric symptoms. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2003, 5, 139–153. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker AW, Ince J, Duncan SH, Webster LM, Holtrop G, Ze X, Brown D, Stares MD, Scott P, Bergerat A et al: Dominant and diet-responsive groups of bacteria within the human colonic microbiota. ISME J. 2011, 5, 220–230. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrieze A, Van Nood E, Holleman F, Salojarvi J, Kootte RS, Bartelsman JF, Dallinga-Thie GM, Ackermans MT, Serlie MJ, Oozeer R et al: Transfer of intestinal microbiota from lean donors increases insulin sensitivity in individuals with metabolic syndrome. Gastroenterology.

- Rooks MG, Garrett WS: Gut microbiota, metabolites and host immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 341–352. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu J, Tan Y, Cheng H, Zhang D, Feng W, Peng C: Functions of Gut Microbiota Metabolites, Current Status and Future Perspectives. Aging Dis. 2022, 13, 1106–1126. [CrossRef]

- Thursby E, Juge N: Introduction to the human gut microbiota. Biochem. J. 2017, 474, 1823–1836. [CrossRef]

- Silva YP, Bernardi A, Frozza RL: The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids From Gut Microbiota in Gut-Brain Communication. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2020, 11:25.

- Kim CH: Complex regulatory effects of gut microbial short-chain fatty acids on immune tolerance and autoimmunity. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2023, 20, 341–350. [CrossRef]

- Daneman R, Rescigno M: The gut immune barrier and the blood-brain barrier: are they so different? Immunity 2009, 31, 722–735. [CrossRef]

- Scalise AA, Kakogiannos N, Zanardi F, Iannelli F, Giannotta M: The blood-brain and gut-vascular barriers: from the perspective of claudins. Tissue Barriers 2021, 9, 1926190. [CrossRef]

- Vancamelbeke M, Vermeire S: The intestinal barrier: a fundamental role in health and disease. Expert. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 11, 821–834. [CrossRef]

- Johansson ME, Phillipson M, Petersson J, Velcich A, Holm L, Hansson GC: The inner of the two Muc2 mucin-dependent mucus layers in colon is devoid of bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2008, 105, 15064–15069. [CrossRef]

- Pelaseyed T, Bergstrom JH, Gustafsson JK, Ermund A, Birchenough GM, Schutte A, van der Post S, Svensson F, Rodriguez-Pineiro AM, Nystrom EE et al: The mucus and mucins of the goblet cells and enterocytes provide the first defense line of the gastrointestinal tract and interact with the immune system. Immunol. Rev. 2014, 260, 8–20.

- Herath M, Hosie S, Bornstein JC, Franks AE, Hill-Yardin EL: The Role of the Gastrointestinal Mucus System in Intestinal Homeostasis: Implications for Neurological Disorders. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2020, 10:248.

- Lian P, Braber S, Garssen J, Wichers HJ, Folkerts G, Fink-Gremmels J, Varasteh S: Beyond Heat Stress: Intestinal Integrity Disruption and Mechanism-Based Intervention Strategies. Nutrients 2020, 12.

- Tsiaoussis GI, Assimakopoulos SF, Tsamandas AC, Triantos CK, Thomopoulos KC: Intestinal barrier dysfunction in cirrhosis: Current concepts in pathophysiology and clinical implications. World J. Hepatol. 2015, 7, 2058–2068. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin Y, Han S, Kwon J, Ju S, Choi TG, Kang I, Kim SS: Roles of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nutrients 2023, 15.

- Schreiner TG, Romanescu C, Popescu BO: The Blood-Brain Barrier-A Key Player in Multiple Sclerosis Disease Mechanisms. Biomolecules 2022, 12.

- Hawkins BT, Davis TP: The blood-brain barrier/neurovascular unit in health and disease. Pharmacol. Rev. 2005, 57, 173–185. [CrossRef]

- Tscheik C, Blasig IE, Winkler L: Trends in drug delivery through tissue barriers containing tight junctions. Tissue Barriers 2013, 1, e24565. [CrossRef]

- Fock E, Parnova R: Mechanisms of Blood-Brain Barrier Protection by Microbiota-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids. Cells 2023, 12.

- Fusco W, Lorenzo MB, Cintoni M, Porcari S, Rinninella E, Kaitsas F, Lener E, Mele MC, Gasbarrini A, Collado MC et al: Short-Chain Fatty-Acid-Producing Bacteria: Key Components of the Human Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2023, 15.

- Bested AC, Logan AC, Selhub EM: Intestinal microbiota, probiotics and mental health: from Metchnikoff to modern advances: Part II - contemporary contextual research. Gut Pathog. 2013, 5, 3. [CrossRef]

- Rogers GB, Keating DJ, Young RL, Wong ML, Licinio J, Wesselingh S: From gut dysbiosis to altered brain function and mental illness: mechanisms and pathways. Mol. Psychiatry 2016, 21, 738–748. [CrossRef]

- Roy CC, Kien CL, Bouthillier L, Levy E: Short-chain fatty acids: ready for prime time? Clin. Pract. 2006, 21, 351–366.

- den Besten G, van Eunen K, Groen AK, Venema K, Reijngoud DJ, Bakker BM: The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 2013, 54, 2325–2340. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogal A, Valdes, A.M. and Menni, C.: The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between gut microbiota and diet in cardio-metabolic health. Gut microbes 2021, 13(1):1-24.

- LeBlanc JG MC, de Giori GS, Sesma F, van Sinderen D, Ventura M.: Bacteria as vitamin suppliers to their host: a gut microbiota perspective. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2013, 24(2):160-168.

- Watanabe F, Bito T: Vitamin B(12) sources and microbial interaction. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2018, 243, 148–158. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pompei A, Cordisco L, Amaretti A, Zanoni S, Matteuzzi D, Rossi M: Folate production by bifidobacteria as a potential probiotic property. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 179–185. [CrossRef]

- Hill MJ: Intestinal flora and endogenous vitamin synthesis. Eur, S: Prev 1997, 6 Suppl 1, 1997.

- Ivanov, II, Honda K: Intestinal commensal microbes as immune modulators. Cell Host Microbe 2012, 12, 496–508. [CrossRef]

- Zheng A, Fowler JR: The Effectiveness of Preoperative Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Ulnar Nerve Release at the Cubital Tunnel. Hand (N Y) 2024, 19(2):224-227.

- Huo R, Zeng B, Zeng L, Cheng K, Li B, Luo Y, Wang H, Zhou C, Fang L, Li W et al: Microbiota Modulate Anxiety-Like Behavior and Endocrine Abnormalities in Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2017, 7:489.

- Schatzberg AF, Keller J, Tennakoon L, Lembke A, Williams G, Kraemer FB, Sarginson JE, Lazzeroni LC, Murphy GM: HPA axis genetic variation, cortisol and psychosis in major depression. Mol. Psychiatry 2014, 19, 220–227. [CrossRef]

- Fries GR, Vasconcelos-Moreno MP, Gubert C, dos Santos BT, Sartori J, Eisele B, Ferrari P, Fijtman A, Ruegg J, Gassen NC et al: Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction and illness progression in bipolar disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2014, 18.

- Tetel MJ, de Vries GJ, Melcangi RC, Panzica G, O’Mahony SM: Steroids, stress and the gut microbiome-brain axis. J Neuroendocrinol 2018, 30.

- Mayer EA: The neurobiology of stress and gastrointestinal disease. Gut 2000, 47, 861–869. [CrossRef]

- Lyte M, Li W, Opitz N, Gaykema RP, Goehler LE: Induction of anxiety-like behavior in mice during the initial stages of infection with the agent of murine colonic hyperplasia Citrobacter rodentium. Physiol. Behav. 2006, 89, 350–357. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng ZH, Zhu Y, Li QL, Zhao C, Zhou PH: Enteric Nervous System: The Bridge Between the Gut Microbiota and Neurological Disorders. Front Aging Neurosci, 8104.

- Appleton J: The Gut-Brain Axis: Influence of Microbiota on Mood and Mental Health. Integr Med (Encinitas) 2018, 17, 28–32.

- Maffei ME: 5-Hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP): Natural Occurrence, Analysis, Biosynthesis, Biotechnology, Physiology and Toxicology. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 22.

- Dorszewska J F-WJ, Kowalska M, Stanski M, Kowalewska A, Kozubski W: Serotonin in Neurological Diseases. In Serotonin - A Chemical Messenger Between All Types of Living Cells. 2017.

- Wu SC, Cao, Z.S., Chang, K.M. and Juang, J.L.: Intestinal microbial dysbiosis aggravates the progression of Alzheimer’s disease in Drosophila. Nature communications 2017, 8(1):24.

- Scheperjans F, Aho V, Pereira PA, Koskinen K, Paulin L, Pekkonen E, Haapaniemi E, Kaakkola S, Eerola-Rautio J, Pohja M et al: Gut microbiota are related to Parkinson’s disease and clinical phenotype. Mov. Disord. 2015, 30, 350–358.

- Zhai CD, Zheng JJ, An BC, Huang HF, Tan ZC: Intestinal microbiota composition in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: establishment of bacterial and archaeal communities analyses. Chin Med J (Engl) 2019, 132, 1815–1822. [CrossRef]

- Brial F, Le Lay A, Dumas ME, Gauguier D: Implication of gut microbiota metabolites in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2018, 75, 3977–3990. [CrossRef]

- Ethanic M, Stanimirov B, Pavlovic N, Golocorbin-Kon S, Al-Salami H, Stankov K, Mikov M: Pharmacological Applications of Bile Acids and Their Derivatives in the Treatment of Metabolic Syndrome. Front Pharmacol, 1382.

- Jia X, Xu W, Zhang L, Li X, Wang R, Wu S: Impact of Gut Microbiota and Microbiota-Related Metabolites on Hyperlipidemia. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2021, 11:634780.

- Facchin S, Bertin L, Bonazzi E, Lorenzon G, De Barba C, Barberio B, Zingone F, Maniero D, Scarpa M, Ruffolo C et al: Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Human Health: From Metabolic Pathways to Current Therapeutic Implications. Life (Basel) 2024, 14.

- Utzschneider KM, Kratz M, Damman CJ, Hullar M: Mechanisms Linking the Gut Microbiome and Glucose Metabolism. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 101, 1445–1454. [CrossRef]

- Fukui H, Xu X, Miwa H: Role of Gut Microbiota-Gut Hormone Axis in the Pathophysiology of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2018, 24, 367–386. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leeuwendaal NK, Cryan JF, Schellekens H: Gut peptides and the microbiome: focus on ghrelin. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2021, 28, 243–252. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajiri K, Shimizu Y: Branched-chain amino acids in liver diseases. Transl, 4: Hepatol 2018, 3, 2018.

- Zhou M, Shao J, Wu CY, Shu L, Dong W, Liu Y, Chen M, Wynn RM, Wang J, Wang J et al: Targeting BCAA Catabolism to Treat Obesity-Associated Insulin Resistance. Diabetes 2019, 68, 1730–1746. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agus A, Clement K, Sokol H: Gut microbiota-derived metabolites as central regulators in metabolic disorders. Gut 2021, 70, 1174–1182. [CrossRef]

- Meseguer V, Alpizar YA, Luis E, Tajada S, Denlinger B, Fajardo O, Manenschijn JA, Fernandez-Pena C, Talavera A, Kichko T et al: TRPA1 channels mediate acute neurogenic inflammation and pain produced by bacterial endotoxins. Nat Commun 2014, 5:3125.

- Mazgaeen L, Gurung P: Recent Advances in Lipopolysaccharide Recognition Systems. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21.

- Pavlov VA: The evolving obesity challenge: targeting the vagus nerve and the inflammatory reflex in the response. Pharmacol, 1: 222, 1077.

- Fedulovs A, Pahirko L, Jekabsons K, Kunrade L, Valeinis J, Riekstina U, Pirags V, Sokolovska J: Association of Endotoxemia with Low-Grade Inflammation, Metabolic Syndrome and Distinct Response to Lipopolysaccharide in Type 1 Diabetes. Biomedicines 2023, 11.

- Metz CN, Brines M, Xue X, Chatterjee PK, Adelson RP, Roth J, Tracey KJ, Gregersen PK, Pavlov VA: Increased plasma lipopolysaccharide-binding protein and altered inflammatory mediators reveal a pro-inflammatory state in overweight women. BMC Womens Health 2025, 25, 57.

- Qin J, Li Y, Cai Z, Li S, Zhu J, Zhang F, Liang S, Zhang W, Guan Y, Shen D et al: A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature 2012, 490, 55–60. [CrossRef]

- Salguero MV, Al-Obaide MAI, Singh R, Siepmann T, Vasylyeva TL: Dysbiosis of Gram-negative gut microbiota and the associated serum lipopolysaccharide exacerbates inflammation in type 2 diabetic patients with chronic kidney disease. Exp. Ther. Med. 2019, 18, 3461–3469.

- Meng L, Song Z, Liu A, Dahmen U, Yang X, Fang H: Effects of Lipopolysaccharide-Binding Protein (LBP) Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) in Infections, Inflammatory Diseases, Metabolic Disorders and Cancers. Front Immunol, 6818.

- Di Tommaso N, Gasbarrini A, Ponziani FR: Intestinal Barrier in Human Health and Disease. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18.

- Di Vincenzo F, Del Gaudio A, Petito V, Lopetuso LR, Scaldaferri F: Gut microbiota, intestinal permeability, and systemic inflammation: a narrative review. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2024, 19, 275–293. [CrossRef]

- Poto R, Fusco W, Rinninella E, Cintoni M, Kaitsas F, Raoul P, Caruso C, Mele MC, Varricchi G, Gasbarrini A et al: The Role of Gut Microbiota and Leaky Gut in the Pathogenesis of Food Allergy. Nutrients 2023, 16.

- Resta-Lenert S, Barrett KE: Probiotics and commensals reverse TNF-alpha- and IFN-gamma-induced dysfunction in human intestinal epithelial cells. Gastroenterology 2006, 130, 731–746. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virk MS, Virk MA, He Y, Tufail T, Gul M, Qayum A, Rehman A, Rashid A, Ekumah JN, Han X et al: The Anti-Inflammatory and Curative Exponent of Probiotics: A Comprehensive and Authentic Ingredient for the Sustained Functioning of Major Human Organs. Nutrients 2024, 16.

- Ridlon JM, Harris SC, Bhowmik S, Kang DJ, Hylemon PB: Consequences of bile salt biotransformations by intestinal bacteria. Gut Microbes 2016, 7, 22–39. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urdaneta V, Casadesus J: Interactions between Bacteria and Bile Salts in the Gastrointestinal and Hepatobiliary Tracts. Front Med (Lausanne) 2017, 4:163.

- Stofan M, Guo GL: Bile Acids and FXR: Novel Targets for Liver Diseases. Front Med (Lausanne) 2020, 7:544.

- Chiang JYL, Ferrell JM: Discovery of farnesoid X receptor and its role in bile acid metabolism. Mol Cell Endocrinol, 2022, 548:111618.

- Wean JB, Smith BN: Fibroblast Growth Factor 19 Increases the Excitability of Pre-Motor Glutamatergic Dorsal Vagal Complex Neurons From Hyperglycemic Mice. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2021, 12, 765359.

- Li K, Zou J, Li S, Guo J, Shi W, Wang B, Han X, Zhang H, Zhang P, Miao Z et al: Farnesoid X receptor contributes to body weight-independent improvements in glycemic control after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery in diet-induced obese mice. Molecular metabolism 2020, 37:100980.

- Boland BB, Mumphrey MB, Hao Z, Townsend RL, Gill B, Oldham S, Will S, Morrison CD, Yu S, Munzberg H et al: Combined loss of GLP-1R and Y2R does not alter progression of high-fat diet-induced obesity or response to RYGB surgery in mice. Molecular metabolism 2019, 25:64-72.

- Fleishman JS, Kumar S: Bile acid metabolism and signaling in health and disease: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 97. [CrossRef]

- Ruze R, Song J, Yin X, Chen Y, Xu R, Wang C, Zhao Y: Mechanisms of obesity- and diabetes mellitus-related pancreatic carcinogenesis: a comprehensive and systematic review. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 139. [CrossRef]

- Masse KE, Lu VB: Short-chain fatty acids, secondary bile acids and indoles: gut microbial metabolites with effects on enteroendocrine cell function and their potential as therapies for metabolic disease. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 1169.

- Lun W, Yan Q, Guo X, Zhou M, Bai Y, He J, Cao H, Che Q, Guo J, Su Z: Mechanism of action of the bile acid receptor TGR5 in obesity. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2024, 14, 468–491. [CrossRef]

- Tolhurst G, Heffron H, Lam YS, Parker HE, Habib AM, Diakogiannaki E, Cameron J, Grosse J, Reimann F, Gribble FM: Short-chain fatty acids stimulate glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion via the G-protein-coupled receptor FFAR2. Diabetes 2012, 61, 364–371. [CrossRef]

- Margolis KG, Cryan JF, Mayer EA: The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis: From Motility to Mood. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 1486–1501. [CrossRef]

- May KS, den Hartigh LJ: Modulation of Adipocyte Metabolism by Microbial Short-Chain Fatty Acids. Nutrients 2021, 13.

- Mishra SP, Karunakar P, Taraphder S, Yadav H: Free Fatty Acid Receptors 2 and 3 as Microbial Metabolite Sensors to Shape Host Health: Pharmacophysiological View. Biomedicines 2020, 8.

- Arora T, Tremaroli V: Therapeutic Potential of Butyrate for Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2021, 12:761834.

- Mayorga-Ramos A, Barba-Ostria C, Simancas-Racines D, Guaman LP: Protective role of butyrate in obesity and diabetes: New insights. Front Nutr, 2022, 9:1067647.

- Abou-Samra M, Venema K, Ayoub Moubareck C, Karavetian M: The Association of Peptide Hormones with Glycemia, Dyslipidemia, and Obesity in Lebanese Individuals. Metabolites 2022, 12.

- Bahne E, Sun EWL, Young RL, Hansen M, Sonne DP, Hansen JS, Rohde U, Liou AP, Jackson ML, de Fontgalland D et al: Metformin-induced glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion contributes to the actions of Metformin in type 2 diabetes. JCI Insight 2018, 3.

- Hansen LS, Gasbjerg LS, Bronden A, Dalsgaard NB, Bahne E, Stensen S, Hellmann PH, Rehfeld JF, Hartmann B, Wewer Albrechtsen NJ et al: The role of glucagon-like peptide 1 in the postprandial effects of Metformin in type 2 diabetes: a randomized crossover trial. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2024, 191, 192–203.

- Loh K, Herzog H, Shi YC: Regulation of energy homeostasis by the NPY system. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 26, 125–135. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larraufie P, Martin-Gallausiaux C, Lapaque N, Dore J, Gribble FM, Reimann F, Blottiere HM: SCFAs strongly stimulate PYY production in human enteroendocrine cells. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 74.

- Kuhre RE, Wewer Albrechtsen NJ, Larsen O, Jepsen SL, Balk-Moller E, Andersen DB, Deacon CF, Schoonjans K, Reimann F, Gribble FM et al: Bile acids are important direct and indirect regulators of the secretion of appetite- and metabolism-regulating hormones from the gut and pancreas. Molecular metabolism 2018, 11:84-95.

- Metges CC: Contribution of microbial amino acids to amino acid homeostasis of the host. J Nutr 2000, 130, 1857S–1864S. [CrossRef]

- Wang TJ, Larson MG, Vasan RS, Cheng S, Rhee EP, McCabe E, Lewis GD, Fox CS, Jacques PF, Fernandez C et al: Metabolite profiles and the risk of developing diabetes. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 448–453. [CrossRef]

- Yang G, Wei J, Liu P, Zhang Q, Tian Y, Hou G, Meng L, Xin Y, Jiang X: Role of the gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes and related diseases. Metabolism, 2021, 117:154712.

- Crudele L, Gadaleta RM, Cariello M, Moschetta A: Gut microbiota in the pathogenesis and therapeutic approaches of diabetes. EBioMedicine, 2023, 97:104821.

- Zhou G, Myers R, Li Y, Chen Y, Shen X, Fenyk-Melody J, Wu M, Ventre J, Doebber T, Fujii N et al: Role of AMP-activated protein kinase in mechanism of metformin action. J. Clin. Invest. 2001, 108, 1167–1174. [CrossRef]

- Giannarelli R, Aragona M, Coppelli A, Del Prato S: Reducing insulin resistance with Metformin: the evidence today. Diabetes Metab, 2003, 29(4 Pt 2):6S28-35.

- Cao G, Gong T, Du Y, Wang Y, Ge T, Liu J: Mechanism of metformin regulation in central nervous system: Progression and future perspectives. Biomed Pharmacother, 2022, 156:113686.

- Lin H, Ao H, Guo G, Liu M: The Role and Mechanism of Metformin in Inflammatory Diseases. J Inflamm Res, 2023, 16:5545-5564.

- Zhang Q, Hu N: Effects of Metformin on the Gut Microbiota in Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes, 2020, 13:5003-5014.

- He R, Zheng R, Li J, Cao Q, Hou T, Zhao Z, Xu M, Chen Y, Lu J, Wang T et al: Individual and Combined Associations of Glucose Metabolic Components With Cognitive Function Modified by Obesity. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021, 12:769120.

- Rosell-Diaz M, Fernandez-Real JM: Metformin, Cognitive Function, and Changes in the Gut Microbiome. Endocr. Rev. 2024, 45, 210–226. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung MM, Chen YL, Pei D, Cheng YC, Sun B, Nicol CJ, Yen CH, Chen HM, Liang YJ, Chiang MC: The neuroprotective role of Metformin in advanced glycation end product treated human neural stem cells is AMPK-dependent. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1852, 720–731. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta A, Bisht B, Dey CS: Peripheral insulin-sensitizer drug metformin ameliorates neuronal insulin resistance and Alzheimer’s-like changes. Neuropharmacology 2011, 60, 910–920. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Mir MY, Detaille D, G RV, Delgado-Esteban M, Guigas B, Attia S, Fontaine E, Almeida A, Leverve X: Neuroprotective role of antidiabetic drug metformin against apoptotic cell death in primary cortical neurons. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2008, 34, 77–87. [CrossRef]

- Hwang IK, Kim IY, Joo EJ, Shin JH, Choi JW, Won MH, Yoon YS, Seong JK: Metformin normalizes type 2 diabetes-induced decrease in cell proliferation and neuroblast differentiation in the rat dentate gyrus. Neurochem. Res. 2010, 35, 645–650. [CrossRef]

- Tang X, Brinton RD, Chen Z, Farland LV, Klimentidis Y, Migrino R, Reaven P, Rodgers K, Zhou JJ: Use of oral diabetes medications and the risk of incident dementia in US veterans aged >/=60 years with type 2 diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2022, 10.

- Loan A, Syal C, Lui M, He L, Wang J: Promising use of Metformin in treating neurological disorders: biomarker-guided therapies. Neural Regen. Res. 2024, 19, 1045–1055. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).