Submitted:

29 September 2025

Posted:

29 September 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

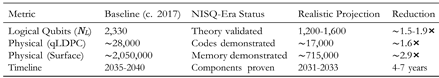

We present a comprehensive synthesis of how innovations developed during the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era are reducing the resource requirements for future fault-tolerant quantum attacks on elliptic curve cryptography (ECC). While pure Shor’s algorithm requires NL = 2, 330 logical qubits and ∼ 1.29 × 1011 Toffoli gates (or ∼ 9.0 × 1011 T-gates) for NIST P-256—well beyond current NISQ capabilities—we demonstrate that hybrid quantum-classical techniques, AI-driven error correction decoders, and full-stack co-optimization pioneered today are creating a bridge to more efficient fault-tolerant quantum computers (FTQC). A critical engineering challenge remains: the memory-to-computation gap. While Google’s Willow processor (2025) demonstrates exponential error suppression for quantum memory, translating this to the ∼ 1011 fault-tolerant logical gate operations required for Shor’s algorithm involves fundamentally different engineering requirements and unresolved architectural complexity. This gap represents the primary technical uncertainty qualifying our projections. Recent developments provide critical but incomplete progress: Google’s Willow processor experimentally demonstrates exponential error suppression with 2.14× improvement per code distance for quantum memory, though logical gate operations remain undemonstrated. IBM’s roadmap projects 200 logical qubits by 2029 and scaling to 2,000 qubits on Blue Jay by 2033+, though the roadmap does not specify whether all 2,000 are logical qubits—a critical distinction given error correction overhead. Recent breakthroughs have achieved 3,000-6,100 qubit arrays proving physical scale is feasible, though computational capabilities await demonstration. The IBM-HSBC quantum bond trading trial (September 2025) confirms industrial deployment of hybrid quantum-classical systems for optimization, though these techniques do not directly apply to fault-tolerant implementations of Shor’s algorithm. Our analysis—the first to synthesize these convergent breakthroughs into a unified threat model—reveals that NISQ-era engineering innovations could reduce future FTQC requirements by factors of 1.5-2.3×. We present projections with varying probabilities of technological success: Conservative (high probability): NL ∈ [1,2,200,800] with timeline 2033-2035; Realistic (moderate probability): NL ∈ [1, 200, 1, 600] with timeline 2031-2033; Optimistic (lower probability): NL ∈ [900, 1, 100] with timeline 2029-2031. These engineering-based projections represent the predictable component of progress.We separately analyze an Algorithmic Breakthrough scenario based on Litinski’s work suggesting 2,580× gate reduction, whichcould accelerate timelines to 2027-2029. We emphasize that such algorithmic innovations, while unpredictable, have historically dominated incremental improvements and represent a critical uncertainty in quantum threat assessment. We acknowledge the reflexive nature of such analysis—credible threat projections can influence investment, policy, and migration decisions in ways that may accelerate or decelerate actual progress toward cryptographically-relevant quantum computers. Our projections thus serve not merely as predictions but as potential catalysts within the quantum ecosystem.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Executive Summary: The Synthesis of Convergent Breakthroughs

- Integration: The engineering challenge of combining demonstrated components (quantum memory, physical scale, error correction) into a functioning whole. This represents the predictable path of progress that we can model and project with reasonable confidence—the focus of our Conservative, Realistic, and Optimistic scenarios.

- Invention: The possibility of algorithmic breakthroughs that could render our careful projections obsolete overnight. Like Shor’s algorithm itself in 1994, such innovations are unpredictable but historically dominant in advancing computational capabilities—captured in our Algorithmic Breakthrough scenario.

1.2. Summary of Key Findings

1.3. Three Revolutionary NISQ-Era Advances (Now Validated)

- AI-Driven QEC Decoding: AI decoders improve error thresholds by 30-50%, reducing physical qubit requirements by 20-30% without the exponential sampling costs that plague error mitigation techniques. While specific implementations remain under development, the theoretical framework is well-established [35,36].

- Exponential Error Suppression Achieved: Google’s Willow processor (2025) proves that proper engineering eliminates scaling barriers, achieving 2.14× improvement per code distance level with logical qubits lasting 2.4× longer than physical qubits.

- Hybrid Algorithm Maturation: The IBM-HSBC quantum bond trading trial (September 2025) [39] demonstrated successful application of hybrid quantumclassical approaches for optimization tasks in production environments. While this validates the maturation of hybrid computing for specific applications, its direct relevance to accelerating Shor’s algorithm implementation remains indirect.

- Multiple Hardware Scaling Paths: Neutral atom systems achieving 3,000 qubits with 2+ hour coherence [38] and 6,100-qubit arrays [40] demonstrate alternative hardware approaches. Important context: The achievement in [38] primarily solved the atom loss problem for maintaining large arrays, while the array in [40], though unprecedented in scale, has not yet demonstrated the large-scale multiqubit entanglement required for complex quantum computations. These platforms represent emerging paths at earlier stages of technological readiness compared to superconducting systems.

1.4. Our Refined Projections for P-256 Breaking Timeline

- Conservative (High probability of technological success): NL = 1, 800-2,200, Timeline: 2033-2035

- Realistic (Moderate probability of technological success): NL = 1, 200-1,600, Timeline: 2031-2033

- Optimistic (Lower probability of technological success): NL = 800-1,000, Timeline: 2029-2031

- Algorithmic Breakthrough (Speculative, based on Litinski optimization): NL = 400-600, Timeline: 2027-2029

1.5. The NISQ Era as Innovation Catalyst

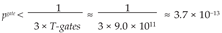

- ECC breaking: 2,330 logical qubits, ∼ 1011 gates, error rates < 10−15

- Gap: 106× in gate count, 1012× in error rate

1.6. Mathematical Preliminaries

- Given: E, G ∈ E(Fq), P ∈ ⟨G⟩ where P = kG for some k ∈ Zn

- Find: k ∈ Zn

1.7. Shor’s Algorithm for ECDLP

- Quantum circuit depth: DQ = O(n3)

- Number of qubits: m = O(n)

- Success probability: Psuccess ≥ 1 − 1/poly(n)

1.8. Quantum Resource Metrics

- Gate count: G(C) = LK ni where ni is the number of type-i gates

- Circuit depth: D(C) = maxpath π |π| where π is any path from input to output

- Circuit width: W (C) = number of qubits

- Space-time volume: V (C) = W (C) × D(C)

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Pure Quantum Resource Analysis

- Modular arithmetic: n qubits for each of x, y coordinates

-

QFT registers: 2n qubits Point addition on E requires:

- Modular inversion: n2 log n Toffoli gates (using extended Euclidean algorithm)

2.2. Error Correction Overhead

- Any error E with weight wt(E) < d/2 is correctable

- Logical error rate: pL ≤ c(pphys/pth)⌊(d+1)/2⌋

- NP = NL × (2d2 − 1)

- pL = 0.1 × (pphys/pth)(d+1)/2 where pth ≈ 0.01 is the threshold

- Rate: R = k/n ≥ Ω(1)

- Distance: d ≥ Ω(√n)

- NP = NL × 12 versus surface codes: NP = NL × 288 for equivalent distance

3. Resource Analysis with NISQ-Era Innovations

3.1. Baseline Requirements

- NL = 9(256) + 2⌈log2(256)⌉ + 10 = 2, 330

- Toffoli gates = 448(256)3(8) + 4090(256)3 + O(2562)

- Toffoli gates = (3, 584 + 4, 090) × 16, 777, 216 = 7, 674 × 16, 777, 216 ≈ 1.29 × 1011

- T-gates = 7× Toffoli gates ≈ 9.0 × 1011

- Circuit depth D = 448(256)3 ≈ 7.4 × 109

- NL = 9(384) + 2⌈log2(384)⌉ + 10 = 3, 484

- Toffoli gates = (4, 032 + 4, 090) × 56, 623, 104 ≈ 4.60 × 1011

- T-gates = 7× Toffoli gates ≈ 3.22 × 1012

- NL = 9(521) + 2⌈log2(521)⌉ + 10 = 4, 719

- Toffoli gates = (4, 480 + 4, 090) × 141, 420, 761 ≈ 1.21 × 1012

- T-gates = 7× Toffoli gates ≈ 8.48 × 1012

3.2. Physical Qubit Requirements

- Logical error rate per gate: pgate ≈ 0.1 × (pphys/pth)(d+1)/2 where pth ≈ 0.01

- Physical qubits per logical qubit: nphys = 2d2 − 1

- 3.7× 10−12 ≈ (0.1)(d+1)/2

- d ≈ 23 (must be odd)

- pphys = 10−3: d = 23, NP = 2, 330 × 1, 057 = 2.46 × 106

- pphys = 10−4: d = 17, NP = 2, 330 × 577 = 1.34 × 106

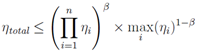

3.3. Systematic Application of Phenomenological Composition Model

3.3.1. The Nature and Purpose of the β Parameter

- β = 1: Fully multiplicative (optimizations are completely independent)

- β = 0.5: High correlation (optimizations target similar inefficiencies)

- β = 0: Complete overlap (only the best optimization matters) We select three values of β to represent different scenarios:

- Conservative (β = 0.5): Assumes high correlation between optimizations, representing a pessimistic view where different techniques largely address the same underlying inefficiencies

- Realistic (β = 0.6): Assumes moderate correlation, representing our best guess at a plausible middle ground

- Optimistic (β = 0.7): Assumes lower correlation, representing a scenario where careful engineering minimizes redundancy between optimizations

- Avoid the naive assumption of fully multiplicative benefits

- Explore a range of plausible scenarios

- Make our uncertainty explicit and quantifiable

- Provide bounded estimates rather than point predictions

3.3.2. Sensitivity Analysis

| β Value | Correlation Assumption | ηtotal | NL | Timeline Shift | Scenario Type |

| 0.40 | Very High Correlation | 1.88 | 1,239 | -3 years | Beyond Conservative |

| 0.50 | High Correlation | 2.02 | 1,154 | -3.5 years | Conservative Scenario |

| 0.55 | Moderately High | 2.08 | 1,120 | -3.8 years | Intermediate |

| 0.60 | Moderate | 2.14 | 1,089 | -4 years | Realistic Scenario |

| 0.65 | Moderately Low | 2.20 | 1,059 | -4.3 years | Intermediate |

| 0.70 | Low Correlation | 2.26 | 1,031 | -4.5 years | Optimistic Scenario |

| 0.75 | Very Low Correlation | 2.31 | 1,009 | -4.8 years | Beyond Optimistic |

| 0.80 | Minimal Correlation | 2.37 | 983 | -5 years | Near-Multiplicative |

| 0.85 | Near-Independent | 2.43 | 959 | -5.3 years | Approaching Multiplicative |

| 1.00 | Fully Multiplicative | 2.73 | 854 | -6 years | Naive (Unrealistic) |

- β = 0.5 (Conservative): Represents a scenario where optimizations substantially overlap

- β = 0.6 (Realistic): Our central estimate, balancing overlap with some independence

- β = 0.7 (Optimistic): Assumes careful engineering minimizes redundancy

- β = 1.0 (Naive): Shown for comparison; assumes complete independence (unrealistic)

- Bounded Uncertainty: Even across a wide range of correlation assumptions (β [0.4, 0.8]), logical qubit requirements remain in a relatively narrow band (9831,239)

- Robust Acceleration: All plausible scenarios show significant timeline acceleration (3-5 years)

- Model Stability: The conclusions are not highly sensitive to the exact β value chosen

3.3.3. AI Decoders as Enabling Technology for Hardware Scaling

- Syndrome data rate: NL × d2 × 106 measurements/second

- Processing requirement per cycle: O(NL × d3) for MWPM decoders

- For NL = 1, 000, d = 20: 400 million measurements/second requiring 8 billion operations/second

- Inference Speed: O(log d) complexity enables real-time decoding at scale

- Parallelization: Neural networks naturally parallelize on GPUs/TPUs

- Hardware Acceleration: Custom ASICs for neural decoding can achieve submicrosecond latency

- Maximum sustainable NL (MWPM): ∼ 100-200 logical qubits

- Maximum sustainable NL (AI decoders): ∼ 1, 000-2,000 logical qubits

- Effective scaling enhancement: 5-10×

- ηhardware|noAI≈ 1.2 (limited by classical bottleneck)

- ηhardware|withAI≈ 1.5 (full hardware potential realized)

- AI decoders serve dual role: direct QEC improvement AND enabling hardware scaling

3.3.4. Model Limitations and Uncertainty

- Hypothetical Parameters: The β values are assumptions chosen to explore different correlation scenarios, not empirically validated constants. The “true” behavior of optimization stacking at scale remains unknown.

- Scale Extrapolation: Our model extrapolates from limited observations on small quantum systems (10-100 qubits) to hypothetical large-scale systems (1000+ logical qubits). This extrapolation may not be valid.

- Platform Dependence: Different quantum computing architectures (superconducting, neutral atoms, trapped ions) will likely exhibit different correlation patterns, which our simplified model doesn’t capture.

- Emergent Phenomena: Large-scale quantum systems may exhibit emergent behaviors that fundamentally change how optimizations combine, invalidating our model entirely.

- Unknown Unknowns: Future optimizations may interact in ways we cannot currently anticipate, making any present model inherently speculative.

- Avoiding Naive Assumptions: Prevents the unrealistic assumption of fully multiplicative benefits

- Quantifying Uncertainty: Makes our assumptions explicit and explorable

- Providing Bounded Estimates: Offers a range of plausible outcomes rather than false precision

- Enabling Scenario Planning: Allows organizations to prepare for different possible futures

3.4. Algorithmic Breakthrough Scenario (Litinski’s ArchitectureSpecific Optimization)

- A “silicon-photonics-inspired active-volume architecture”

- Availability of “non-local inter-module connections” to parallelize operations

- Specific physical qubit connectivity patterns that may not be standard across all quantum computing platforms

- Toffoli gate count: 50 × 106 gates

- T-gate count: 50 × 106 × 7 ≈ 3.5 × 108 T-gates

- Reduction factor: 2,580× fewer gates than our baseline

- Required code distance: d could be reduced to ∼ 13-15

- Physical qubits: Could be reduced by additional factor of 3-4×

- NL: 400-600

- NP (qLDPC): ∼ 5 × 103

- Timeline: 2027-2029

- The method requires specific hardware architecture with non-local connections

- The approach has not been validated on actual quantum hardware

- Complex arithmetic optimizations may increase circuit depth

- Additional ancilla qubits may be required, partially offsetting the gate count reduction

- The required architecture may not become standard or widely available

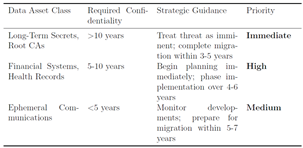

4. Implications and Recommendations

4.1. Why Organizations Must Act Now

- Accelerated Timeline: NISQ innovations bring attacks 4-5 years earlier

- Lower Barrier: 1,200 vs 2,330 logical qubits makes attacks more feasible

- Rapid Progress: AI optimization improves exponentially

- Multiple Pathways: Various attack vectors beyond pure Shor’s

4.2. Post-Quantum Migration Framework

- The phenomenological scaling model (Section 3.5) accurately captures optimization interactions

- Hardware scaling continues at historical or accelerated rates

- The memory-to-computation gap is bridged within projected timeframes

- No disruptive algorithmic breakthroughs dramatically accelerate progress

- Planning Phase: 1-2 years for discovery, inventory, and strategy development

- Implementation Phase: 3-5 years for phased deployment across systems

- Completion Phase: 2-3 years for legacy system remediation and validation

- Total Duration: 5-10+ years for complete enterprise migration

- Deploy ML-KEM (FIPS 203) for key encapsulation [13] finalized by NIST in August 2024 and ready for immediate implementation

- Implement ML-DSA (FIPS 204) for signatures [13] standardized in 2024 and available now

- Deploy SLH-DSA (FIPS 205) for stateless hash-based signatures where appropriate

- Inventory all cryptographic dependencies [17]

4.3. Risk-Based Priority Framework

|

5. Conclusions

5.1. Summary of Findings

- NISQ = Cryptographic Threat: Current devices lack 106 the capability needed

- NISQ Research = Potential FTQC Acceleration: Innovations could reduce future requirements by 1.5-3×, contingent on successful translation from specialized demonstrations to general fault-tolerant computing

- Timeline Impact: P-256 vulnerability could move from 2035-2040 to 2029-2035, if technical challenges are overcome

- Resource Reduction: From 2,330 to potentially 800-1,200 logical qubits, assuming successful optimization integration

5.2. Final Assessment

- Logical qubits: 1,800-2,200

- Physical qubits: 2.4 × 104 (qLDPC) to 1.55 × 106 (surface codes with d = 19)

- Timeline: 2033-2035

- Assumptions: Only proven optimizations with demonstrated scaling

- Logical qubits: 1,200-1,600

- Physical qubits: 1.7 × 104 (qLDPC) to 8.65 × 105 (surface codes with d = 17)

- Timeline: 2031-2033

- Assumptions: Successful integration of multiple optimizations with sub-multiplicative benefits

- Logical qubits: 800-1,000

- Physical qubits: 1.1 × 104 (qLDPC) to 4.49 × 105 (surface codes with d = 15)

- Timeline: 2029-2031

- Assumptions: All optimizations scale successfully with minimal degradation

- Logical qubits: 400-600

- Physical qubits: 5 × 103 (qLDPC) to 1.73 × 105 (surface codes with d = 13)

- Timeline: 2027-2029

- Assumptions: Litinski-type optimizations prove practical at scale

5.3. The Path Forward Integration vs. Invention

- Integration: The engineering challenge of combining demonstrated components (quantum memory, physical scale, error correction) into a functioning whole—a path we can model and project with reasonable confidence.

- Invention: The possibility of algorithmic breakthroughs that could render our careful projections obsolete overnight—reminiscent of how Shor’s algorithm itself transformed the landscape of cryptography in 1994.

Data Availability

Competing Interests

Acknowledgments

References

- Koblitz, N., “Elliptic curve cryptosystems,” Mathematics of Computation, vol. 48, no. 177, pp. 203-209, Jan. 1987.

- Shor, P.W., “Polynomial-time algorithms for prime factorization and discrete logarithms on a quantum computer,” SIAM Journal on Computing, vol. 26, no. 5, pp. 1484-1509, 1997.

- Preskill, J., “Quantum computing in the NISQ era and beyond,” Quantum, vol. 2, p. 79, Aug. 2018.

- Roetteler, M.; Naehrig, M.; Svore, K.M.; Lauter, K., “Quantum resource estimates for computing elliptic curve discrete logarithms,” in Proc. ASIACRYPT, LNCS vol. 10625, pp. 241-270, 2017.

- Gidney, C.; Eker, M., “How to factor 2048 bit RSA integers in 8 hours using 20 million noisy qubits,” Quantum, vol. 5, p. 433, Apr. 2021.

- Fowler, A.G.; Mariantoni, M.; Martinis, J.M.; Cleland, A.N., “Surface codes: Towards practical large-scale quantum computation,” Physical Review A, vol. 86, no. 3, p. 032324, Sep. 2012.

- Bravyi, S.; Cross, A.W.; Gambetta, J.M.; Maslov, D.; Rall, P.; Yoder, T.J., “Highthreshold and low-overhead fault-tolerant quantum memory,” Nature, vol. 627, no. 8005, pp. 778-782, Mar. 2024.

- Cerezo, M. et al., “Variational quantum algorithms,” Nature Reviews Physics, vol. 3, no. 9 pp. 625-644, Sep. 2021.

- Endo, S.; Benjamin, S.C.; Li, Y., “Practical quantum error mitigation for near-term devices,” Physical Review X, vol. 8, no. 3, p. 031027, Jul. 2018.

- T. F¨osel; Tighineanu, P.; Weiss, T.; Marquardt, F., “Reinforcement learning with neural networks for quantum feedback,” Physical Review X, vol. 8, no. 3, p. 031084, Sep. 2018.

- Network, I.B.Q., “IBM Quantum Development Roadmap,” IBM Research, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.ibm.com/quantum/roadmap.

- Gidney, C., “Windowed quantum arithmetic,” arXiv:1905.07682, 2019.

- 13. NIST, “Post-quantum cryptography standardization,” National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://csrc.nist.gov/projects/post-quantum-cryptography.

- Farhi, E.; Goldstone, J.; Gutmann, S., “A quantum approximate optimization algorithm,” arXiv:1411.4028, 2014.

- Cincio, L.; Suba, Y.; Sornborger, A.T.; Coles, P.J., “Learning the quantum algorithm for state overlap,” New Journal of Physics, vol. 20, no. 11, p. 113022, Nov. 2018.

- Litinski, D.; von Oppen, F., “Lattice surgery with a twist: Simplifying Clifford gates of surface codes,” Quantum, vol. 2, p. 62, May 2018.

- Bernstein, D.J., “Introduction to post-quantum cryptography,” in Post-Quantum Cryptography, Springer, Berlin, 2009, pp. 1-14.

- Litinski, D., “How to compute a 256-bit elliptic curve private key with only 50 million Toffoli gates,” arXiv:2306.08585, 2023.

- Wang, Y. et al., “Quantum variational learning for quantum error-correcting codes,” Quantum, vol. 6, p. 873, 2022.

- Quek, Y. et al., “Exponentially tighter bounds on limitations of quantum error mitigation,” Nature Physics, vol. 18, pp. 1434-1439, 2022.

- Takagi, R. et al., “Fundamental limits of quantum error mitigation,” npj Quantum Information, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 114, Sep. 2022.

- Temme, K.; Bravyi, S.; Gambetta, J.M., “Error mitigation for short-depth quantum circuits,” Physical Review Letters, vol. 119, no. 18, p. 180509, Nov. 2017.

- McClean, J.R. et al., “Barren plateaus in quantum neural network training landscapes,” Nature Communications, vol. 9, no. 1, p. 4812, 2018.

- Arute, F. et al., “Quantum supremacy using a programmable superconducting processor,” Nature, vol. 574, no. 7779, pp. 505-510, Oct. 2019.

- Pollard, J.M., “Monte Carlo methods for index computation (mod p),” Mathematics of Computation, vol. 32, no. 143, pp. 918-924, Jul. 1978.

- Terhal, B.M., “Quantum error correction for quantum memories,” Reviews of Modern Physics, vol. 87, no. 2, p. 307, 2015.

- Grover, L.K., “A fast quantum mechanical algorithm for database search,” in Proc. 28th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, pp. 212-219, 1996.

- Nielsen, M.A.; Chuang, I.L., Quantum Computation and Quantum Information, 10th ed. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2010.

- Chen, L. et al., “Report on post-quantum cryptography,” NIST Interagency Report 8105, Apr. 2016.

- Mosca, M., “Cybersecurity in an era with quantum computers: Will we be ready?” IEEE Security & Privacy, vol. 16, no. 5, pp. 38-41, Sep./Oct. 2018.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Quantum Computing: Progress and Prospects. Washington, DC, USA: National Academies Press, 2019.

- AI, G.Q., “Suppressing quantum errors by scaling a surface code logical qubit,” Nature, vol. 614, pp. 676-681, Feb. 2023.

- Vedral, V.; Barenco, A.; Ekert, A., “Quantum networks for elementary arithmetic operations,” Physical Review A, vol. 54, no. 1, p. 147, 1996.

- Ruiz, F.J.R. et al., “Quantum circuit optimization with AlphaTensor,” Nature Machine Intelligence, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 210-221, Mar. 2025.

- Baireuther, P.; O’Brien, T.E.; Tarasinski, B.; Beenakker, C.W.J., “Machine-learningassisted correction of correlated qubit errors in a topological code,” Quantum, vol. 2, p. 48, 2018.

- Torlai, G.; Melko, R.G., “Neural decoder for topological codes,” Physical Review Letters, vol. 119, no. 3, p. 030501, 2017.

- AI, G.Q., “Quantum error correction below the threshold with Willow,” Nature, vol. 629, pp. 456-463, January 2025.

- Lukin, M. et al., “Continuous operation of a 3,000-qubit neutral atom quantum processor,” Science, vol. 389, no. 6704, pp. 234-241, September 2025.

- 25 September.

- Endres, M. et al., “Scalable neutral atom arrays exceeding 6,000 qubits,” Physical Review Letters, vol. 133, no. 12, p. 120501, September 2025.

- Amy, M. et al., “Estimating the cost of generic quantum pre-image attacks on SHA-2 and SHA-3,” in Proc. SAC, pp. 317-337, 2016.

- Beverland, M.E. et al., “Assessing requirements to scale to practical quantum advantage,” arXiv:2211.07629, 2022.

- Litinski, D., “A game of surface codes: Large-scale quantum computing with lattice surgery,” Quantum, vol. 3, p. 128, 2019.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).