Submitted:

28 September 2025

Posted:

30 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Diagnosis and Management

3. MRI Imaging in Detecting High Risk Malignancy in IPMN

4. Computed Tomography in Detecting Malignancy in IPMN

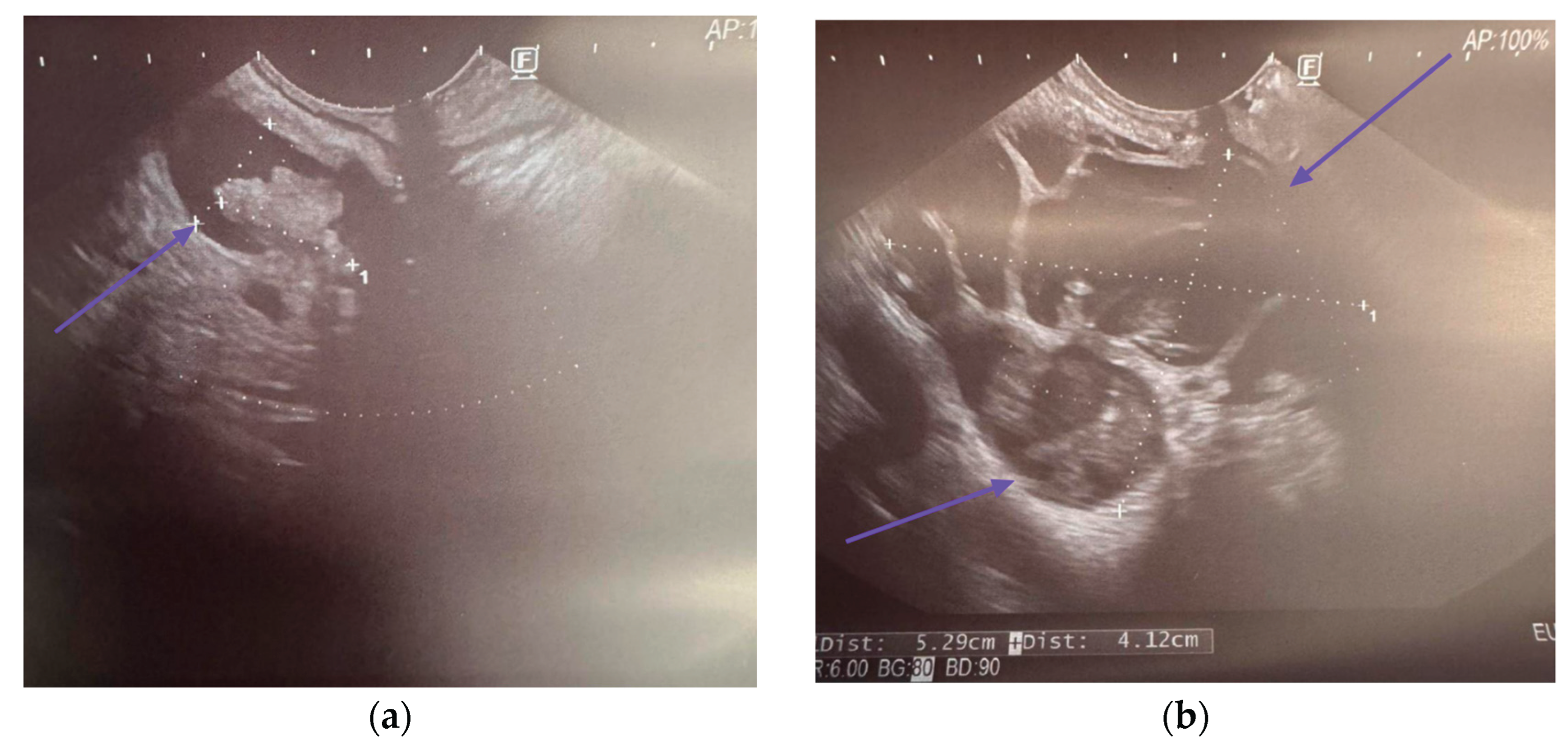

5. Endoscopic Ultrasound in Detecting Malignancy in IPMN

5.1. EUS-Guided Fine Needle Aspiration

5.1.1. Cyst Fluid Analysis

5.1.2. Cytology

5.2. EUS-Guided Through the Needle Biopsy

5.3. EUS-Guided Needle-Based Confocal Laser Endomicroscopy

6. New Emerging Markers for Malignancy in IPMN

7. Pancreatoscopy

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, K.; Talar-Wojnarowska, R.; Dąbrowski, A.; Degowska, M.; Durlik, M.; Gąsiorowska, A.; Głuszek, S.; Jurkowska, G.; Kaczka, A.; Lampe, P.; et al. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Recommendations in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Recommendations of the Working Group of the Polish Pancreatic Club. Gastroenterol. Rev. 2019, 14, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erratum to “Cancer Statistics, 2024. ” CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 203–203. [CrossRef]

- Kolbeinsson, H.M.; Chandana, S.; Wright, G.P.; Chung, M. Pancreatic Cancer: A Review of Current Treatment and Novel Therapies. J. Invest. Surg. 2023, 36, 2129884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbrook, C.J.; Lyssiotis, C.A.; Pasca Di Magliano, M.; Maitra, A. Pancreatic Cancer: Advances and Challenges. Cell 2023, 186, 1729–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, J.; Scheifele, C.; Hinz, U.; Leonhardt, C.-S.; Hank, T.; Koenig, A.-K.; Tjaden, C.; Hackert, T.; Bergmann, F.; Büchler, M.W.; et al. IPMN-Associated Pancreatic Cancer: Survival, Prognostic Staging and Impact of Adjuvant Chemotherapy. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 48, 1309–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Hong, S.-M. Precursor Lesions of Pancreatic Cancer. Oncol. Res. Treat. 2018, 41, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elta, G.H.; Enestvedt, B.K.; Sauer, B.G.; Lennon, A.M. ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Pancreatic Cysts. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 113, 464–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.Y.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, P.Y.; Chen, J. RNF43 Mutations in IPMN Cases: A Potential Prognostic Factor. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2020, 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, T.B.; Park, W.G.; Allen, P.J. Diagnosis and Management of Pancreatic Cysts. Gastroenterology 2024, 167, 454–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerboni, G.; Signoretti, M.; Crippa, S.; Falconi, M.; Arcidiacono, P.G.; Capurso, G. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: Prevalence of Incidentally Detected Pancreatic Cystic Lesions in Asymptomatic Individuals. Pancreatology 2019, 19, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonda, T.A.; Cahen, D.L.; Farrell, J.J. Pancreatic Cysts. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 832–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, J.; Brown, L.; Loveday, B.P. Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm: Overview of Management. Aust. J. Gen. Pract. 2024, 53, 835–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Erning, F.N.; Mackay, T.M.; Van Der Geest, L.G.M.; Groot Koerkamp, B.; Van Laarhoven, H.W.M.; Bonsing, B.A.; Wilmink, J.W.; Van Santvoort, H.C.; De Vos-Geelen, J.; Van Eijck, C.H.J.; et al. Association of the Location of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (Head, Body, Tail) with Tumor Stage, Treatment, and Survival: A Population-Based Analysis. Acta Oncol. 2018, 57, 1655–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabłońska, B.; Szmigiel, P.; Mrowiec, S. Pancreatic Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms: Current Diagnosis and Management. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2021, 13, 1880–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, T.; Klöppel, G.; Volkan Adsay, N.; Albores-Saavedra, J.; Fukushima, N.; Horii, A.; Hruban, R.H.; Kato, Y.; Klimstra, D.S.; Longnecker, D.S.; et al. Classification of Types of Intraductal Papillary-Mucinous Neoplasm of the Pancreas: A Consensus Study. Virchows Arch. 2005, 447, 794–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, S.; Naitoh, Y.; Mino-Kenudson, M.; Sakurai, T.; Kuroda, M.; Koyama, I.; Lauwers, G.Y.; Shimizu, M. Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm (IPMN) of the Pancreas: Its Histopathologic Difference Between 2 Major Types. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2006, 30, 1561–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basturk, O.; Hong, S.-M.; Wood, L.D.; Adsay, N.V.; Albores-Saavedra, J.; Biankin, A.V.; Brosens, L.A.A.; Fukushima, N.; Goggins, M.; Hruban, R.H.; et al. A Revised Classification System and Recommendations From the Baltimore Consensus Meeting for Neoplastic Precursor Lesions in the Pancreas. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2015, 39, 1730–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furukawa, T.; Fukushima, N.; Itoi, T.; Ohike, N.; Mitsuhashi, T.; Nakagohri, T.; Notohara, K.; Shimizu, M.; Tajiri, T.; Tanaka, M.; et al. A Consensus Study of the Grading and Typing of Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms of the Pancreas. Pancreas 2019, 48, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, K.; Kanemitsu, S.; Hatori, T.; Maguchi, H.; Shimizu, Y.; Tada, M.; Nakagohri, T.; Hanada, K.; Osanai, M.; Noda, Y.; et al. Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Derived From IPMN and Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Concomitant With IPMN. Pancreas 2011, 40, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, E.M.; Khatri, G.; Morgan, D.; Kang, S.; Bhosale, P.R.; Francis, I.R.; Gandhi, N.S.; Hough, D.M.; Huang, C.; Luk, L.; et al. Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm (IPMN) of the Pancreas: Recommendations for Standardized Imaging and Reporting from the Society of Abdominal Radiology IPMN Disease Focused Panel. Abdom. Radiol. 2021, 46, 1586–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohtsuka, T.; Fernandez-del Castillo, C.; Furukawa, T.; Hijioka, S.; Jang, J.-Y.; Lennon, A.M.; Miyasaka, Y.; Ohno, E.; Salvia, R.; Wolfgang, C.L.; et al. International Evidence-Based Kyoto Guidelines for the Management of Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm of the Pancreas. Pancreatology 2024, 24, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjaden, C.; Sandini, M.; Mihaljevic, A.L.; Kaiser, J.; Khristenko, E.; Mayer, P.; Hinz, U.; Gaida, M.M.; Berchtold, C.; Diener, M.K.; et al. Risk of the Watch-and-Wait Concept in Surgical Treatment of Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm. JAMA Surg. 2021, 156, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvia, R.; Burelli, A.; Perri, G.; Marchegiani, G. State-of-the-Art Surgical Treatment of IPMNs. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2021, 406, 2633–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pretis, N.; Martinelli, L.; Amodio, A.; Caldart, F.; Crucillà, S.; Battan, M.S.; Zorzi, A.; Crinò, S.F.; Conti Bellocchi, M.C.; Bernardoni, L.; et al. Branch Duct IPMN-Associated Acute Pancreatitis in a Large Single-Center Cohort Study. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The European Study Group on Cystic Tumours of the Pancreas European Evidence-Based Guidelines on Pancreatic Cystic Neoplasms. Gut 2018, 67, 789–804. [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.; Ali, K.; Vyas, S.; Dezsi, K.; Strickland, D.; Basinski, T.; Chen, D.-T.; Jiang, K.; Centeno, B.; Malafa, M.; et al. Comparison of Imaging Modalities for Measuring the Diameter of Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms of the Pancreas. Pancreatology 2020, 20, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Onofrio, M.; Tedesco, G.; Cardobi, N.; De Robertis, R.; Sarno, A.; Capelli, P.; Martini, P.T.; Giannotti, G.; Beleù, A.; Marchegiani, G.; et al. Magnetic Resonance (MR) for Mural Nodule Detection Studying Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms (IPMN) of Pancreas: Imaging-Pathologic Correlation. Pancreatology 2021, 21, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, S.; Tang, T.; Su, Q.; Wang, Y.; Shu, Z.; Yang, W.; Gong, X. Radiomic Nomogram Based on MRI to Predict Grade of Branching Type Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms of the Pancreas: A Multicenter Study. Cancer Imaging 2021, 21, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, J.H.; Kim, Y.K.; Kim, S.K.; Kim, H.; Ahn, S. Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm of the Pancreas: Diagnostic Performance of the 2017 International Consensus Guidelines Using CT and MRI. Eur. Radiol. 2021, 31, 4774–4784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Choi, S.-Y.; Min, J.H.; Yi, B.H.; Lee, M.H.; Kim, S.S.; Hwang, J.A.; Kim, J.H. Determining Malignant Potential of Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm of the Pancreas: CT versus MRI by Using Revised 2017 International Consensus Guidelines. Radiology 2019, 293, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Cui, Y.; Shao, J.; Shao, Z.; Su, F.; Li, Y. The Diagnostic Role of CT, MRI/MRCP, PET/CT, EUS and DWI in the Differentiation of Benign and Malignant IPMN: A Meta-Analysis. Clin. Imaging 2021, 72, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.B.; Lee, N.K.; Kim, S.; Seo, H.-I.; Park, Y.M.; Noh, B.G.; Kim, D.U.; Han, S.Y.; Kim, T.U. Diagnostic Performance of Magnetic Resonance Image for Malignant Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms: The Importance of Size of Enhancing Mural Nodule within Cyst. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2022, 40, 1282–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Cao, Y.; Ren, S.; Guo, K.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, T.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, Z. Threshold of Main Pancreatic Duct Diameter in Identifying Malignant Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm by Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2023, 22, 15330338231170942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobaly, D.; Santinha, J.; Sartoris, R.; Dioguardi Burgio, M.; Matos, C.; Cros, J.; Couvelard, A.; Rebours, V.; Sauvanet, A.; Ronot, M.; et al. CT-Based Radiomics Analysis to Predict Malignancy in Patients with Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm (IPMN) of the Pancreas. Cancers 2020, 12, 3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, J.; Midya, A.; Gazit, L.; Attiyeh, M.; Langdon-Embry, L.; Allen, P.J.; Do, R.K.G.; Simpson, A.L. CT Radiomics to Predict High-risk Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms of the Pancreas. Med. Phys. 2018, 45, 5019–5029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, F.; Li, M.; Chu, T.; Duan, H.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Duan, K.; Liu, H.; Wei, F. Comprehensive Analysis of Clinical Data and Radiomic Features from Contrast Enhanced CT for Differentiating Benign and Malignant Pancreatic Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 17218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacelli, M.; Celsa, C.; Magro, B.; Barchiesi, M.; Barresi, L.; Capurso, G.; Arcidiacono, P.G.; Cammà, C.; Crinò, S.F. Diagnostic Performance of Endoscopic Ultrasound Through-the-needle Microforceps Biopsy of Pancreatic Cystic Lesions: Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. Dig. Endosc. 2020, 32, 1018–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, R.; Thosani, N.; Annangi, S.; Guha, S.; Bhutani, M.S. Diagnostic Yield of EUS-FNA-Based Cytology Distinguishing Malignant and Benign IPMNs: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pancreatology 2014, 14, 380–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.-X.; Xiao, J.; Orange, M.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, Y.-Q. EUS-Guided FNA for Diagnosis of Pancreatic Cystic Lesions: A Meta-Analysis. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 36, 1197–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Heckler, M.; Liu, B.; Heger, U.; Hackert, T.; Michalski, C.W. Cytologic Analysis of Pancreatic Juice Increases Specificity of Detection of Malignant IPMN-A Systematic Review. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Off. Clin. Pract. J. Am. Gastroenterol. Assoc. 2019, 17, 2199–2211.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckler, M.; Brieger, L.; Heger, U.; Pausch, T.; Tjaden, C.; Kaiser, J.; Tanaka, M.; Hackert, T.; Michalski, C.W. Predictive Performance of Factors Associated with Malignancy in Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasia of the Pancreas: Factors Associated with Malignancy in Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasia of the Pancreas. BJS Open 2018, 2, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno, E.; Balduzzi, A.; Hijioka, S.; De Pastena, M.; Marchegiani, G.; Kato, H.; Takenaka, M.; Haba, S.; Salvia, R. Association of High-Risk Stigmata and Worrisome Features with Advanced Neoplasia in Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms (IPMN): A Systematic Review. Pancreatology 2024, 24, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsumura, A.; Hirono, S.; Kawai, M.; Okada, K.; Miyazawa, M.; Kitahata, Y.; Kobayashi, R.; Hayami, S.; Ueno, M.; Yanagisawa, A.; et al. Surgical Indication for Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm without Mural Nodule ≥5 Mm. Surgery 2021, 169, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Liu, F.; Li, J.; Cao, K.; Wang, T.; Zhang, H.; Li, Q.; Meng, Y.; Yu, J.; Feng, X.; et al. Computed Tomography Nomogram to Predict a High-Risk Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm of the Pancreas. Abdom. Radiol. 2021, 46, 5218–5228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.K.; Kim, J.H.; Yoo, J.; Kim, J.-E.; Park, S.J.; Han, J.K. Assessment of Malignant Potential in Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms of the Pancreas Using MR Findings and Texture Analysis. Eur. Radiol. 2021, 31, 3394–3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megibow, A.J.; Baker, M.E.; Morgan, D.E.; Kamel, I.R.; Sahani, D.V.; Newman, E.; Brugge, W.R.; Berland, L.L.; Pandharipande, P.V. Management of Incidental Pancreatic Cysts: A White Paper of the ACR Incidental Findings Committee. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2017, 14, 911–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vege, S.S.; Ziring, B.; Jain, R.; Moayyedi, P.; Adams, M.A.; Dorn, S.D.; Dudley-Brown, S.L.; Flamm, S.L.; Gellad, Z.F.; Gruss, C.B.; et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on the Diagnosis and Management of Asymptomatic Neoplastic Pancreatic Cysts. Gastroenterology 2015, 148, 819–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.A.; Choi, S.-Y.; Lee, J.E.; Kim, S.S.; Lee, S.; Moon, J.Y.; Heo, N.H. Pre-Operative Nomogram Predicting Malignant Potential in the Patients with Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm of the Pancreas: Focused on Imaging Features Based on Revised International Guideline. Eur. Radiol. 2020, 30, 3711–3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.H.A.; Oba, A.; Beaty, L.; Colborn, K.L.; Rodriguez Franco, S.; Harnke, B.; Meguid, C.; Negrini, D.; Valente, R.; Ahrendt, S.; et al. Ductal Dilatation of ≥5 Mm in Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm Should Trigger the Consideration for Pancreatectomy: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review of Resected Cases. Cancers 2021, 13, 2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.J.; Jang, J.; Lee, S.; Park, T.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, S. Clinicopathological Meaning of Size of Main-Duct Dilatation in Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm of Pancreas: Proposal of a Simplified Morphological Classification Based on the Investigation on the Size of Main Pancreatic Duct. World J. Surg. 2015, 39, 2006–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.S.; Park, T.; Han, Y.; Lee, S.; Lim, H.; Kim, H.; Kim, S.H.; Kwon, W.; Kim, S.-W.; Jang, J.-Y. Clinical Validation of the 2017 International Consensus Guidelines on Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm of the Pancreas. Ann. Surg. Treat. Res. 2019, 97, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, W.T.; Lawson, R.D.; Hunt, G.; Fehmi, S.M.; Proudfoot, J.A.; Xu, R.; Giap, A.; Tang, R.S.; Gonzalez, I.; Krinsky, M.L.; et al. Rapid Growth Rates of Suspected Pancreatic Cyst Branch Duct Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms Predict Malignancy. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2015, 60, 2800–2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelga, P.; Hernandez-Barco, Y.G.; Qadan, M.; Ferrone, C.R.; Kambadakone, A.; Horick, N.; Jah, A.; Warshaw, A.L.; Lillemoe, K.D.; Balakrishnan, A.; et al. Number of Worrisome Features and Risk of Malignancy in Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2022, 234, 1021–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Radiology, Hacettepe University School of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey; Idilman, I. S. Proton Density Fat Fraction: Magnetic Resonance Imaging Applications beyond the Liver. Diagn. Interv. Radiol. 2022, 28, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukui, H.; Hori, M.; Fukuda, Y.; Onishi, H.; Nakamoto, A.; Ota, T.; Ogawa, K.; Ninomiya, K.; Tatsumi, M.; Osuga, K.; et al. Evaluation of Fatty Pancreas by Proton Density Fat Fraction Using 3-T Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Its Association with Pancreatic Cancer. Eur. J. Radiol. 2019, 118, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotozono, H.; Kanki, A.; Yasokawa, K.; Yamamoto, A.; Sanai, H.; Moriya, K.; Tamada, T. Value of 3-T MR Imaging in Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm with a Concomitant Invasive Carcinoma. Eur. Radiol. 2022, 32, 8276–8284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swauger, S.E.; Fashho, K.; Hornung, L.N.; Elder, D.A.; Thapaliya, S.; Anton, C.G.; Trout, A.T.; Abu-El-Haija, M. Association of Pancreatic Fat on Imaging with Pediatric Metabolic Co-Morbidities. Pediatr. Radiol. 2023, 53, 2030–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, R.J.; Kinahan, P.E.; Hricak, H. Radiomics: Images Are More than Pictures, They Are Data. Radiology 2016, 278, 563–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Shi, H.; Lu, M.; Wang, C.; Duan, S.; Xu, Q.; Shi, H. Radiomics Analysis for Predicting Malignant Potential of Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms of the Pancreas: Comparison of CT and MRI. Acad. Radiol. 2022, 29, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attiyeh, M.A.; Chakraborty, J.; Gazit, L.; Langdon-Embry, L.; Gonen, M.; Balachandran, V.P.; D’Angelica, M.I.; DeMatteo, R.P.; Jarnagin, W.R.; Kingham, T.P.; et al. Preoperative Risk Prediction for Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms by Quantitative CT Image Analysis. HPB 2019, 21, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.C.; Kim, J.H.; Jeon, S.K.; Kang, H.-J. CT Findings and Clinical Effects of High Grade Pancreatic Intraepithelial Neoplasia in Patients with Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0298278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, W.; Han, Y.; Byun, Y.; Kang, J.S.; Choi, Y.J.; Kim, H.; Jang, J.-Y. Predictive Features of Malignancy in Branch Duct Type Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm of the Pancreas: A Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2020, 12, 2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouladi, D.F.; Raman, S.P.; Hruban, R.H.; Fishman, E.K.; Kawamoto, S. Invasive Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms: CT Features of Colloid Carcinoma Versus Tubular Adenocarcinoma of the Pancreas. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2020, 214, 1092–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.T.; Sadler, T.J.; Whitley, S.; Brais, R.; Godfrey, E. The CT Fish Mouth Ampulla Sign: A Highly Specific Finding in Main Duct and Mixed Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms. Br. J. Radiol. 2019, 92, 20190461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa-Gallego, C.; Miyasaka, Y.; Hozaka, Y.; Nishino, H.; Kawamoto, M.; Vieira, D.L.; Ohtsuka, T.; Wolfgang, C. Surveillance after Resection of Non-Invasive Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms (IPMN). A Systematic Review. Pancreatology 2023, 23, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kin, T.; Shimizu, Y.; Hijioka, S.; Hara, K.; Katanuma, A.; Nakamura, M.; Yamada, R.; Itoi, T.; Ueki, T.; Masamune, A.; et al. A Comparative Study between Computed Tomography and Endoscopic Ultrasound in the Detection of a Mural Nodule in Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm –Multicenter Observational Study in Japan. Pancreatology 2023, 23, 550–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, Y.; Kawaji, Y.; Shimokawa, T.; Yamazaki, H.; Tamura, T.; Hatamaru, K.; Itonaga, M.; Ashida, R.; Kawai, M.; Kitano, M. Usefulness of Contrast-Enhanced Harmonic Endoscopic Ultrasonography for Diagnosis of Malignancy in Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno, E.; Kawashima, H.; Ishikawa, T.; Iida, T.; Suzuki, H.; Uetsuki, K.; Yashika, J.; Yamada, K.; Yoshikawa, M.; Gibo, N.; et al. Can Contrast-Enhanced Harmonic Endoscopic Ultrasonography Accurately Diagnose Main Pancreatic Duct Involvement in Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms? Pancreatology 2020, 20, 887–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Jiang, F.; Zhu, J.; Du, Y.; Jin, Z.; Li, Z. Assessment of Morbidity and Mortality Associated with Endoscopic Ultrasound-guided Fine-needle Aspiration for Pancreatic Cystic Lesions: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Dig. Endosc. 2017, 29, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pflüger, M.J.; Jamouss, K.T.; Afghani, E.; Lim, S.J.; Rodriguez Franco, S.; Mayo, H.; Spann, M.; Wang, H.; Singhi, A.; Lennon, A.M.; et al. Predictive Ability of Pancreatic Cyst Fluid Biomarkers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pancreatology 2023, 23, 868–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, T.R.; Garg, R.; Rustagi, T. Pancreatic Cyst Fluid Glucose in Differentiating Mucinous from Nonmucinous Pancreatic Cysts: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2021, 94, 698–712.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, S.; Takahashi, C.; Snyder, R.A.; Parikh, A.A. Stratifying Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms by Cyst Fluid Analysis: Present and Future. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, W.G.-U.; Mascarenhas, R.; Palaez-Luna, M.; Smyrk, T.C.; O’Kane, D.; Clain, J.E.; Levy, M.J.; Pearson, R.K.; Petersen, B.T.; Topazian, M.D.; et al. Diagnostic Performance of Cyst Fluid Carcinoembryonic Antigen and Amylase in Histologically Confirmed Pancreatic Cysts. Pancreas 2011, 40, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Waaij, L.A.; Van Dullemen, H.M.; Porte, R.J. Cyst Fluid Analysis in the Differential Diagnosis of Pancreatic Cystic Lesions: A Pooled Analysis. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2005, 62, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, C.G.; Wood, L.D. From Somatic Mutation to Early Detection: Insights from Molecular Characterization of Pancreatic Cancer Precursor Lesions. J. Pathol. 2018, 246, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Takeda, Y.; Ono, Y.; Isomoto, H.; Mizukami, Y. Current Status of Molecular Diagnostic Approaches Using Liquid Biopsy. J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 58, 834–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesali, S.; Demir, M.A.; Verbeke, C.S.; Andersson, M.; Bratlie, S.O.; Sadik, R. EUS Is Accurate in Characterizing Pancreatic Cystic Lesions; a Prospective Comparison with Cross-Sectional Imaging in Resected Cases. Surg. Endosc. 2021, 35, 6650–6659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitman, M.B.; Centeno, B.A.; Ali, S.Z.; Genevay, M.; Stelow, E.; Mino-Kenudson, M.; Fernandez-del Castillo, C.; Max Schmidt, C.; Brugge, W.; Layfield, L. Standardized Terminology and Nomenclature for Pancreatobiliary Cytology: The Papanicolaou Society of Cytopathology Guidelines. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2014, 42, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitman, M.B.; Layfield, L.J. The Papanicolaou Society of Cytopathology System for Reporting Pancreaticobiliary Cytology: Definitions, Criteria and Explanatory Notes; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015; ISBN 978-3-319-16588-2. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, S.; Del Portillo, A.; Gonda, T.A.; Kluger, M.D.; Tiscornia-Wasserman, P.G. Update on Risk Stratification in the Papanicolaou Society of Cytopathology System for Reporting Pancreaticobiliary Cytology Categories: 3-Year, Prospective, Single-institution Experience. Cancer Cytopathol. 2020, 128, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, P.K.; Shelton, D.A.; Holbrook, M.R.; Thiryayi, S.A.; Narine, N.; Slater, D.; Rana, D.N. Outcomes of Endoscopic Ultrasound-guided Pancreatic FNAC Diagnosis for Solid and Cystic Lesions at Manchester Royal Infirmary Based upon the Papanicolaou Society of Cytopathology Pancreaticobiliary Terminology Classification Scheme. Cytopathology 2018, 29, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitman, M.B.; Centeno, B.A.; Reid, M.D.; Siddiqui, M.T.; Layfield, L.J.; Perez-Machado, M.; Weynand, B.; Stelow, E.B.; Lozano, M.D.; Fukushima, N.; et al. The World Health Organization Reporting System for Pancreaticobiliary Cytopathology. Acta Cytol. 2023, 67, 304–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, A.M.; Bohra, M.; More, N.M.; Naik, L.P. Papanicolaou Society of Cytopathology System for Reporting Pancreaticobiliary Cytology: Risk Stratification and Cytology Scope - 2.5-Year Study. Cytojournal 2022, 19, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Ramírez, A.N.; Villegas-González, L.F.; Serrano-Arévalo, M.L.; Flores-Hernández, L.; Lino-Silva, L.S.; González-Mena, L.E. Reclassification of Lesions in Biopsies by Fine-Needle Aspiration of Pancreas and Biliary Tree Using Papanicolaou Classification. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2018, 9, 847–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saieg, M.A.; Munson, V.; Colletti, S.; Nassar, A. The Impact of the New Proposed Papanicolaou Society of Cytopathology Terminology for Pancreaticobiliary Cytology in Endoscopic US-FNA : A single-Institutional Experience. Cancer Cytopathol. 2015, 123, 488–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.L.; Abdul-Karim, F.W.; Goyal, A. Cytologic Categorization of Pancreatic Neoplastic Mucinous Cysts with an Assessment of the Risk of Malignancy: A Retrospective Study Based on the P Apanicolaou S Ociety of C Ytopathology Guidelines. Cancer Cytopathol. 2016, 124, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serinelli, S.; Khurana, K.K. Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms of the Pancreas: Cytologic-Histologic Correlation Study and Evaluation of the Cytologic Accuracy in Identifying High-Grade Dysplasia/Invasive Adenocarcinoma. Cytojournal 2024, 21, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, J.; Samanta, J.; Nabi, Z.; Aggarwal, M.; Conti Bellocchi, M.C.; Facciorusso, A.; Frulloni, L.; Crinò, S.F. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Pancreatic Tissue Sampling: Lesion Assessment, Needles, and Techniques. Medicina (Mex.) 2024, 60, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilas-Boas, F.; Ribeiro, T.; Macedo, G.; Dhar, J.; Samanta, J.; Sina, S.; Manfrin, E.; Facciorusso, A.; Conti Bellocchi, M.C.; De Pretis, N.; et al. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Through-the-Needle Biopsy: A Narrative Review of the Technique and Its Emerging Role in Pancreatic Cyst Diagnosis. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacevic, B.; Klausen, P.; Rift, C.V.; Toxværd, A.; Grossjohann, H.; Karstensen, J.G.; Brink, L.; Hassan, H.; Kalaitzakis, E.; Storkholm, J.; et al. Clinical Impact of Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided through-the-Needle Microbiopsy in Patients with Pancreatic Cysts. Endoscopy 2021, 53, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, Z.; Pan, C.; Wu, C.; Li, Z.; Jin, Z.; Wang, K. Comparative Performance of Endoscopic Ultrasound-Based Techniques in Patients With Pancreatic Cystic Lesions: A Network Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 118, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Trindade, A.J.; Yachimski, P.; Benias, P.; Nieto, J.; Manvar, A.; Ho, S.; Esnakula, A.; Gamboa, A.; Sethi, A.; et al. Histologic Analysis of Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Through the Needle Microforceps Biopsies Accurately Identifies Mucinous Pancreas Cysts. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 17, 1587–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Lusong, M.A.A.; Pajes, A.N.N.I. Evaluation of Fine Needle Biopsy (FNB) for Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS)-Guided Tissue Acquisition of Pancreatic Masses to Negate the Need for Rapid On-Site Evaluation: A Randomized Control Trial. Acta Med. Philipp. 2024, 58, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barresi, L.; Tarantino, I.; Traina, M.; Granata, A.; Curcio, G.; Azzopardi, N.; Baccarini, P.; Liotta, R.; Fornelli, A.; Maimone, A.; et al. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Fine Needle Aspiration and Biopsy Using a 22-Gauge Needle with Side Fenestration in Pancreatic Cystic Lesions. Dig. Liver Dis. 2014, 46, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facciorusso, A.; Arvanitakis, M.; Crinò, S.F.; Fabbri, C.; Fornelli, A.; Leeds, J.; Archibugi, L.; Carrara, S.; Dhar, J.; Gkolfakis, P.; et al. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Tissue Sampling: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Technical and Technology Review. Endoscopy 2025, 57, 390–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishna, S.; Abdelbaki, A.; Hart, P.A.; Machicado, J.D. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Needle-Based Confocal Endomicroscopy as a Diagnostic Imaging Biomarker for Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms. Cancers 2024, 16, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Chao, W.-L.; Cao, T.; Culp, S.; Napoléon, B.; El-Dika, S.; Machicado, J.D.; Pannala, R.; Mok, S.; Luthra, A.K.; et al. Improving Pancreatic Cyst Management: Artificial Intelligence-Powered Prediction of Advanced Neoplasms through Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Confocal Endomicroscopy. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, S.G.; Hart, P.A.; DeWitt, J.M.; DiMaio, C.J.; Kongkam, P.; Napoleon, B.; Othman, M.O.; Yew Tan, D.M.; Strobel, S.G.; Stanich, P.P.; et al. EUS-Guided Confocal Laser Endomicroscopy: Prediction of Dysplasia in Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms (with Video). Gastrointest. Endosc. 2020, 91, 551–563.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machicado, J.D.; Napoleon, B.; Lennon, A.M.; El-Dika, S.; Pereira, S.P.; Tan, D.; Pannala, R.; Girotra, M.; Kongkam, P.; Bertani, H.; et al. Accuracy and Agreement of a Large Panel of Endosonographers for Endomicroscopy-Guided Virtual Biopsy of Pancreatic Cystic Lesions. Pancreatology 2022, 22, 994–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheesman, A.R.; Zhu, H.; Liao, X.; Szporn, A.H.; Kumta, N.A.; Nagula, S.; DiMaio, C.J. Impact of EUS-Guided Microforceps Biopsy Sampling and Needle-Based Confocal Laser Endomicroscopy on the Diagnostic Yield and Clinical Management of Pancreatic Cystic Lesions. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2020, 91, 1095–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghir, S.M.; Dhindsa, B.S.; Daid, S.G.S.; Mashiana, H.S.; Dhaliwal, A.; Cross, C.; Singh, S.; Bhat, I.; Ohning, G.V.; Adler, D.G. Efficacy of EUS-Guided Needle-Based Confocal Laser Endomicroscopy in the Diagnosis of Pancreatic Lesions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Endosc. Ultrasound 2022, 11, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maker, A.V.; Katabi, N.; Gonen, M.; DeMatteo, R.P.; D’Angelica, M.I.; Fong, Y.; Jarnagin, W.R.; Brennan, M.F.; Allen, P.J. Pancreatic Cyst Fluid and Serum Mucin Levels Predict Dysplasia in Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms of the Pancreas. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2011, 18, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiles, Z.E.; Khan, S.; Patton, K.T.; Jaggi, M.; Behrman, S.W.; Chauhan, S.C. Transmembrane Mucin MUC13 Distinguishes Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms from Non-Mucinous Cysts and Is Associated with High-Risk Lesions. HPB 2019, 21, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maker, A.V.; Hu, V.; Kadkol, S.S.; Hong, L.; Brugge, W.; Winter, J.; Yeo, C.J.; Hackert, T.; Büchler, M.; Lawlor, R.T.; et al. Cyst Fluid Biosignature to Predict Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms of the Pancreas with High Malignant Potential. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2019, 228, 721–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthaei, H.; Wylie, D.; Lloyd, M.B.; Dal Molin, M.; Kemppainen, J.; Mayo, S.C.; Wolfgang, C.L.; Schulick, R.D.; Langfield, L.; Andruss, B.F.; et al. miRNA Biomarkers in Cyst Fluid Augment the Diagnosis and Management of Pancreatic Cysts. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 4713–4724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utomo, W.K.; Looijenga, L.H.; Bruno, M.J.; Hansen, B.E.; Gillis, A.; Biermann, K.; Peppelenbosch, M.P.; Fuhler, G.M.; Braat, H. A MicroRNA Panel in Pancreatic Cyst Fluid for the Risk Stratification of Pancreatic Cysts in a Prospective Cohort. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2016, 5, e350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirakami, Y.; Iwashita, T.; Uemura, S.; Imai, H.; Murase, K.; Shimizu, M. Micro-RNA Analysis of Pancreatic Cyst Fluid for Diagnosing Malignant Transformation of Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm by Comparing Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Adenoma and Carcinoma. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boroughs, L.K.; DeBerardinis, R.J. Metabolic Pathways Promoting Cancer Cell Survival and Growth. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015, 17, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Gangi, I.M.; Mazza, T.; Fontana, A.; Copetti, M.; Fusilli, C.; Ippolito, A.; Mattivi, F.; Latiano, A.; Andriulli, A.; Vrhovsek, U.; et al. Metabolomic Profile in Pancreatic Cancer Patients: A Consensus-Based Approach to Identify Highly Discriminating Metabolites. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 5815–5829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayers, J.R.; Wu, C.; Clish, C.B.; Kraft, P.; Torrence, M.E.; Fiske, B.P.; Yuan, C.; Bao, Y.; Townsend, M.K.; Tworoger, S.S.; et al. Elevation of Circulating Branched-Chain Amino Acids Is an Early Event in Human Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma Development. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 1193–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, K.Y.; Wu, H.-J.; Menon, S.S.; Fallah, Y.; Zhong, X.; Rizk, N.; Unger, K.; Mapstone, M.; Fiandaca, M.S.; Federoff, H.J.; et al. Metabolomic Biomarkers of Pancreatic Cancer: A Meta-Analysis Study. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 68899–68915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaiser, R.A.; Pessia, A.; Ateeb, Z.; Davanian, H.; Fernández Moro, C.; Alkharaan, H.; Healy, K.; Ghazi, S.; Arnelo, U.; Valente, R.; et al. Integrated Targeted Metabolomic and Lipidomic Analysis: A Novel Approach to Classifying Early Cystic Precursors to Invasive Pancreatic Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K.K.; Xiao, H.; Geng, X.; Fernandez-del-Castillo, C.; Morales-Oyarvide, V.; Daglilar, E.; Forcione, D.G.; Bounds, B.C.; Brugge, W.R.; Pitman, M.B.; et al. mAb Das-1 Is Specific for High-Risk and Malignant Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm (IPMN). Gut 2014, 63, 1626.1–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K.K.; Geng, X.; Brown, J.W.; Morales-Oyarvide, V.; Huynh, T.; Pergolini, I.; Pitman, M.B.; Ferrone, C.; Al Efishat, M.; Haviland, D.; et al. Cross Validation of the Monoclonal Antibody Das-1 in Identification of High-Risk Mucinous Pancreatic Cystic Lesions. Gastroenterology 2019, 157, 720–730.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luca, L.D.; Repici, A.; Koçollari, A.; Auriemma, F.; Bianchetti, M.; Mangiavillano, B. Pancreatoscopy: An Update. World J. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2019, 11, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, D.M.; Stassen, P.M.C.; Groot Koerkamp, B.; Ellrichmann, M.; Karagyozov, P.I.; Anderloni, A.; Kylänpää, L.; Webster, G.J.M.; Van Driel, L.M.J.W.; Bruno, M.J.; et al. The Role of Pancreatoscopy in the Diagnostic Work-up of Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Endoscopy 2023, 55, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vehviläinen, S.; Fagerström, N.; Valente, R.; Seppänen, H.; Udd, M.; Lindström, O.; Mustonen, H.; Swahn, F.; Arnelo, U.; Kylänpää, L. Single-Operator Peroral Pancreatoscopy in the Preoperative Diagnostics of Suspected Main Duct Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms: Efficacy and Novel Insights on Complications. Surg. Endosc. 2022, 36, 7431–7443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miura, T.; Igarashi, Y.; Okano, N.; Miki, K.; Okubo, Y. Endoscopic Diagnosis of Intraductal Papillary-Mucinous Neoplasm of the Pancreas by Means of Peroral Pancreatoscopy Using a Small-Diameter Videoscope and Narrow-Band Imaging. Dig. Endosc. Off. J. Jpn. Gastroenterol. Endosc. Soc. 2010, 22, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishimoto, Y.; Okano, N.; Ito, K.; Takuma, K.; Hara, S.; Iwasaki, S.; Yoshimoto, K.; Yamada, Y.; Watanabe, K.; Kimura, Y.; et al. Peroral Pancreatoscopy with Videoscopy and Narrow-Band Imaging in Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms with Dilatation of the Main Pancreatic Duct. Clin. Endosc. 2022, 55, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koshita, S.; Noda, Y.; Kanno, Y.; Ogawa, T.; Kusunose, H.; Sakai, T.; Yonamine, K.; Miyamoto, K.; Kozakai, F.; Okano, H.; et al. Digital Peroral Pancreatoscopy to Determine Surgery for Patients Who Have Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms of the Pancreas with Mural Nodules. Endosc. Int. Open 2024, 12, E1401–E1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Technique | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC | PPV | NPV | References |

| MRI | 73.4-90.8% | 64.4-94.8% | 0.811-0.903 | 71% | 82.4% | [28,29,30,31,32] |

| MRCP | 38.3-94.1% | 62.5-93.1% | N/A | N/A | N/A | [28,32,33,34] |

| CT | 62-90.4% | 57-86% | 0.71-0.904 | 48-80% | 58-90% | [30,31,32,35,36,37] |

| EUS | 60% | 80% | 0.79 | N/A | N/A | [32] |

| EUS-FNA cytology | 28.7-64.8% | 84-94% | 0.84-0.94 | N/A | N/A | [38,39,40,41] |

| EUS-TTNB | 69.5% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | [38] |

| Risk factors | Sensitivity | Specificity | Guidelines | References | |

| jaundice | 26-83% | 61-97% | IAP European ACG ACR |

[22,42] | |

| enhancing mural nodule or solid component | ≥ 5 mm | 64.6-100% | 73-87.5% | IAP European ACG* ACR* AGA* |

[22,43,49] |

| < 5 mm | N/A | N/A | IAP European ACG* ACR* AGA* |

- | |

| main pancreatic duct dilation | ≥ 10 mm | 28.2-51.7% | 78.7-87.5% | IAP European ACR AGA* |

[43,49,50] |

| ≥ 7 mm | 53.8% | 80.7% | ACR AGA* |

[51] | |

| > 5 mm | 54.7-74.8% | 58.6-78% | ACG AGA* |

[50,52] | |

| ≥ 5 mm and < 10 mm | N/A | N/A | IAP European AGA* |

- | |

| positive cytology | 28.7-64.8% | 84-94% | IAP European ACG AGA |

[38,39,40,41] | |

| acute pancreatitis | 32-42.6% | 86-86.1% | IAP European ACG |

[42,49] | |

| new-onset or worsening diabetes | 46% | 83% | IAP European ACG |

[42] | |

| increased serum level of CA19-9 | > 37 U/mL | 41-74% | 85-96% | IAP European ACG |

[22,42,49] |

| cyst diameter | ≥ 40 mm | N/A | N/A | European | - |

| ≥ 30 mm | 56.1-64% | 53.7-69% | IAP ACG ACR AGA |

[42,52] | |

| thickened/enhancing cyst walls | 23-38.5% | 89.7-95% | IAP ACR |

[42,52] | |

| abrupt change in caliber of pancreatic duct with distal pancreatic atrophy (IAP) focal dilation of pancreatic duct concerning for MD-IPMN or an obstructing lesion (ACG) |

19.3% | 95.9% | IAP ACG |

[52] | |

| lymphadenopathy | 5.2-20% | 93-99.6% | IAP | [42,52[ | |

| cystic growth rate | ≥ 5 mm/year | 56% | 97% | European | [53] |

| > 3 mm/year | N/A | N/A | ACG | - | |

| ≥ 2.5 mm/year | 60.9% | 70.3% | IAP | [52] | |

| abdominal pain | N/A | N/A | European | - | |

| non-enhancing mural nodule | N/A | N/A | ACR | - | |

| Technique | Additional features assessed | Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy | PPV | NPV | AUC | References |

| CT | HRS, WF (2017 ICG Fukuoka) | 79.5-86% | 67.8-74% | 73.7-78% | 71.4% | 76.6% | - | [30,31] |

| CT + radiomics | - | 68-82% | 57-84% | 64-78% | 48-80% | 58-90% | 0.71-0.84 | [35,36,37] |

| HRS, WF (2017 ICG Fukuoka, 2018 European) | 69-80% | 65-72% | 67-76% | 72-78% | 61-75% | 0.75-0.83 | [35] | |

| age, cyst size, presence of solid component, symptoms, gender | 19-93% | 35-100% | 50-80% | 36-97% | 78-95% | 0.74-0.81 | [36,61] | |

| Type of IPMN, cyst size, cystic solid, CA199, CA125, bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, gamma-ggtt, diabetes | 90.4% | 74% | 80% | - | - | 0.904 | [37] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).