1. INTRODUCTION

Virtual Reality (VR) is an emerging technology that creates immersive and interactive environments simulated by computers, with which users can explore and interact, mainly through VR headsets [

1]. This technology relies on three characteristics: presence (the feeling of physically being “there”), interactivity (the ability to influence the virtual environment), and immersion (the blurring of the boundary between the physical and digital worlds) [

2].

Pedagogical Advantages of VR in Primary School

1). Enhanced Engagement and Motivation

VR significantly increases student engagement and motivation, making learning dynamic and interactive [

2]. This enhanced engagement stems from VR’s ability to create immersive multisensory experiences that reduce distractions and foster emotional connections with the content [

5].

2). Improved Learning Outcomes and Knowledge Retention

Students who learn in virtual environments achieve significantly higher academic scores. VR can improve knowledge retention by up to 75% compared to traditional methods, with some studies reporting nearly 80% retention after one year [

5].

3). Fostering Cognitive Development

VR aids in the understanding of complex and abstract concepts (e.g., STEM and geometry) by making them tangible and interactive within a three-dimensional environment [

2]. It enhances visual thinking skills, spatial awareness, memory retention and problem-solving abilities. VR is particularly effective for procedural knowledge acquisition because it allows students to manipulate virtual objects and conduct experiments [

3].

4). Promoting Socio-Emotional Skills

VR is described as an “empathy-inducing medium” [

6] that enables users to “step into someone else’s shoes,” thereby enhancing empathy and cultural understanding [

5]. It encourages collaboration and teamwork through shared virtual experiences and multiplayer functions [

5].

5). Accessible and Safe Experiential Learning

VR provides risk-free environments for practicing dangerous or costly scenarios [

3],[

5]. It also offers educational accessibility to students who are unable to attend school in person (e.g., due to illness). Virtual field trips serve as a cost-effective alternative to traditional excursions, ensuring 100% participation and inclusion [

7],[

5]. Despite these advantages, studies focusing on Primary Education remain comparatively limited [

4].

3. Proposed Solution

The aim of my research is to measure the effectiveness of VR headsets in Primary Education. For this purpose, I selected appropriate software and hardware resources to assess the student performance. Avantis ClassVR headsets were chosen, with my school owning eight of them. During the experimental process, students were divided into subgroups to engage with the teaching materials.

ClassVR provides teachers with central control over headsets. It also offers its own content through Eduverse, an online platform that grants educators immediate access to educational resources. Furthermore, teachers and students can create and upload their own content. This content may include 3D models in GLB or STL format (produced with software such as Paint3D or ThingLink) or 360° photos and videos generated with a 3D camera.

Some software resources were provided by the VR headset company and were available only by subscription. I created the material for the first set of experiments using a 3D camera, which can be accessed via a video link. Additionally, my research team and I developed worksheets to guide the teaching process and assessment sheets to evaluate learning outcomes (available in the VR scenarios link).

For research purposes, students of the same age and learning background were selected and divided into two groups, one serving as the control group.

3.1. First Set of experiments

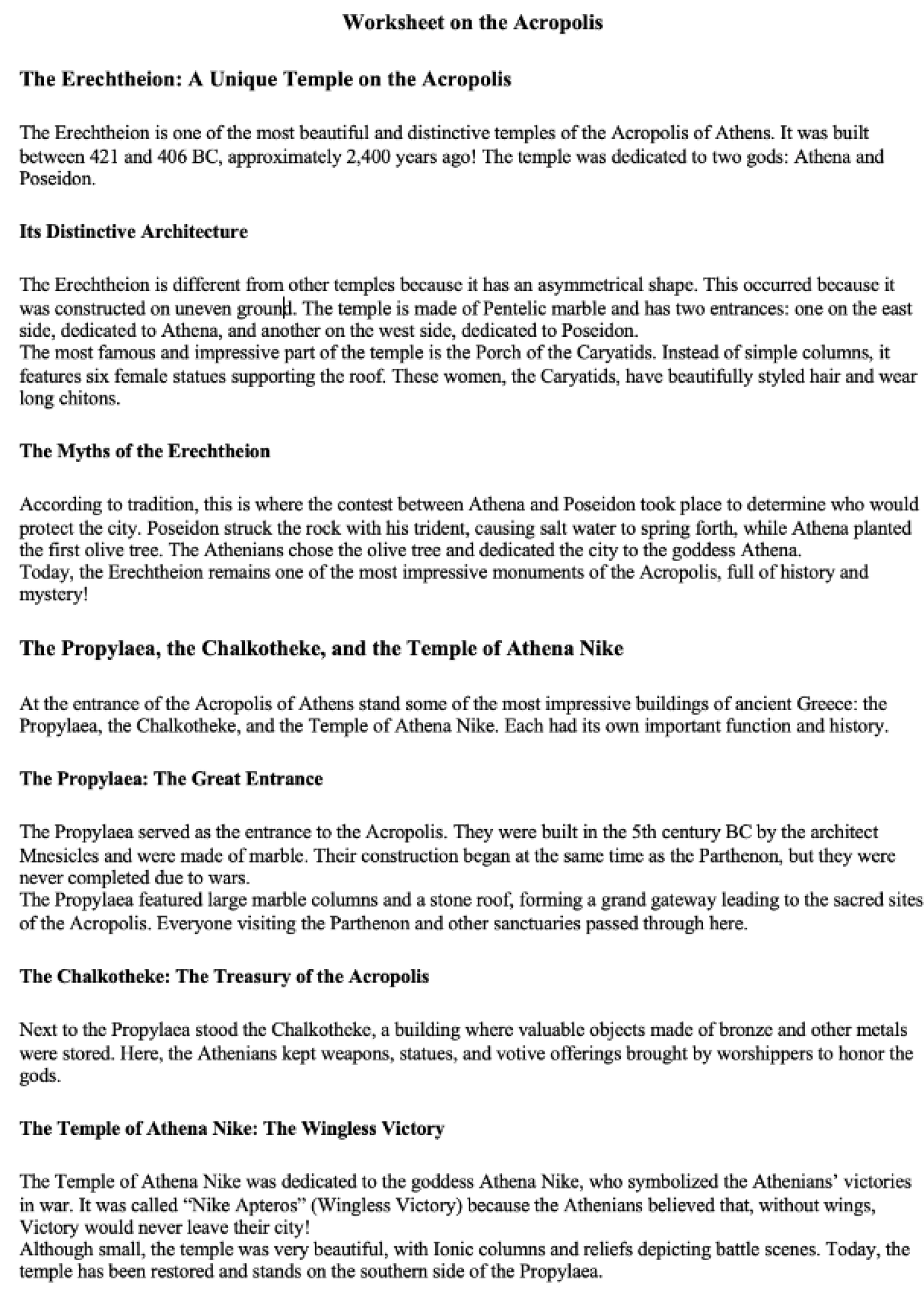

The first set of experiments was conducted with a fifth-grade class of 24 students divided into two subgroups. This experimental series focused on history, specifically a virtual tour of the Acropolis. This study provided the opportunity to design and implement educational material primarily intended to transmit information to children, with the subsequent objective of evaluating learners’ capacity for information recall, corresponding to the first level of Bloom’s Taxonomy. This focus was selected because the assessment of information recall represents one of the most straightforward and reliably measurable cognitive skills.One group of students was given six minutes to read a text about the Propylaea and the Erechtheion, as shown in

Figure 1.

Afterwards, students watched a VR 3D video of a duration of four minutes accompanied by the narrated text. The video, as shown in

Figure 2, was captured with the school’s 3D camera during an excursion.

On the other hand, the control group studied the same text for the same total duration (10 minutes). Both groups then completed the same assessment sheet within eight minutes (

Figure 3).

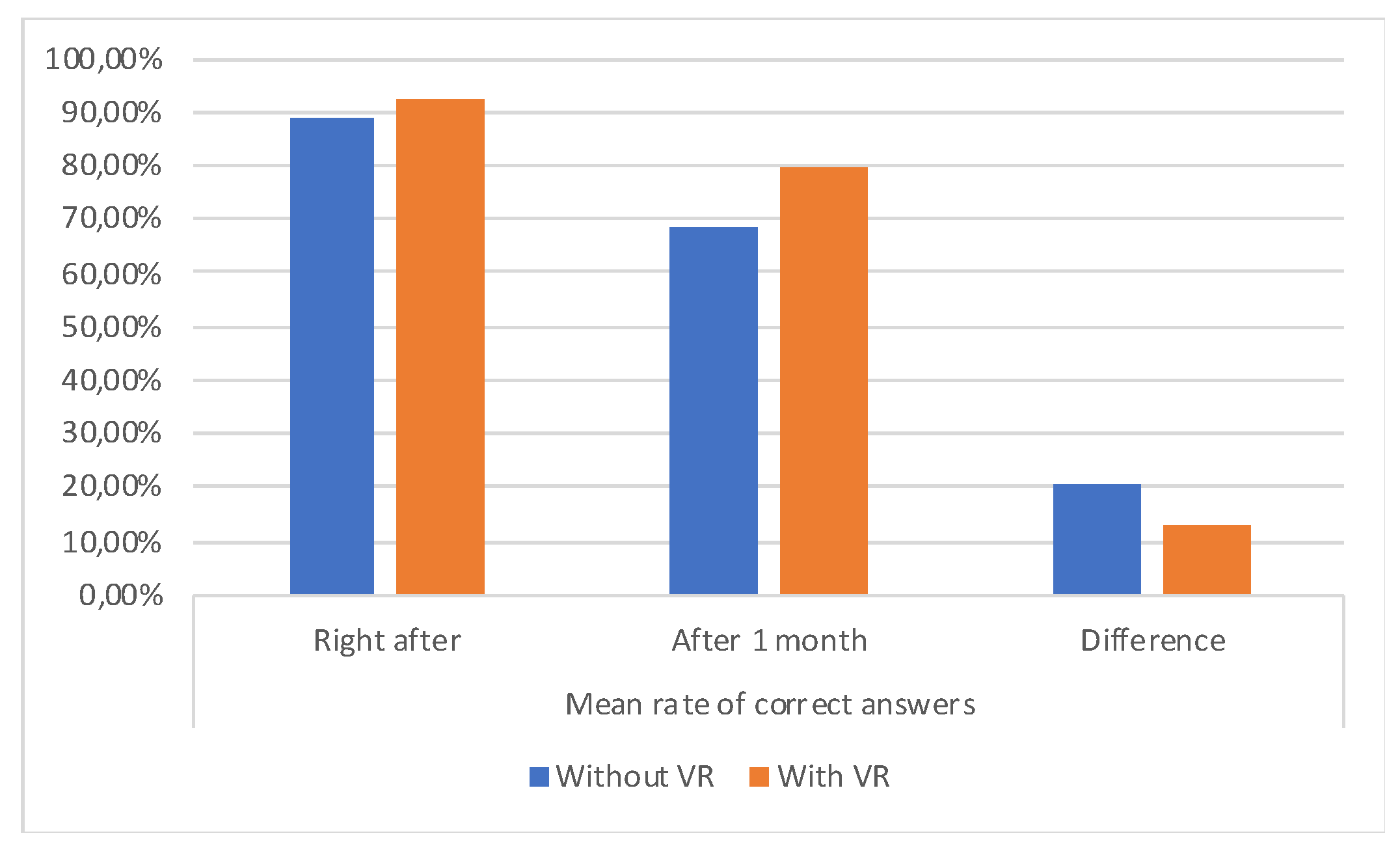

During the evaluation phase, the first group, which had the opportunity to use VR during instruction, achieved an average rate of correct responses of 92.3%. The control group, which spent the same amount of instructional time but had access only to the text ( note that the text was identical to that accompanying the 3D video presented in VR), achieved an average of 88.6% correct responses. This study revealed a small performance difference of 3.7% on a specific standardized closed-ended assessment (Table II).

| Method of Teaching |

Mean rate of Correct Answers |

| Right after |

After 1 month |

Difference through time |

| Without VR |

88,60% |

68,20% |

20,40% |

| With VR |

92,30% |

79,60% |

12,70% |

| Difference through method |

3,70% |

11,40% |

|

The non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test was applied to investigate whether there was a statistically significant difference in performance between the control group (without the use of VR) and the experimental group (with the use of VR). The results indicated that the difference between the two groups was not statistically significant (U = 62.5, p = 0.61). This finding suggests that, based on a specific student sample, the use of virtual reality did not lead to a measurable improvement in performance compared to conventional teaching.

In the second phase, after an interval of one month, students from both groups were administered the same assessment. As expected, the percentage of correct responses decreased in both the groups. However, the VR group showed a smaller decline, achieving 79.6% correct response. In contrast, the control group demonstrated a significantly greater decrease, achieving only 68.2% of correct responses. Thus, the performance gap between the two groups increased substantially, to 11.4%. This difference was considerably larger than the initial measurement, indicating that the group instructed using VR retained knowledge more effectively. Indeed, correct responses in the non-VR group dropped by 20.4%, whereas in the VR group, the decrease was only 12.7%.

The analysis using the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test showed that the performance of the students in the VR group was higher than that of the control group; however, the difference did not reach the level of statistical significance (U = 41.5, p = 0.084, slightly above the critical value of p = 0.05). The results indicated a trend in favor of the VR group, which may become statistically significant with a larger sample size.

These initial results are illustrated in

Figure 4, where it becomes even clearer that the VR group achieved slightly better outcomes than the other groups. The difference in performance between the two groups became more pronounced when a time gap was introduced between instruction and assessment, indicating that the group taught using VR retained knowledge significantly better.

Analyzing this first series of experiments and attempting to interpret why the observed performance difference is noticeable but not striking, we concluded that both the learning material and the assessed skills primarily pertained to the first level of Bloom’s taxonomy—information recall. Moreover, the instructional material in both teaching methods (with and without VR) was identical according to our research methodology, which may have limited the comparative advantage that VR could potentially offer.

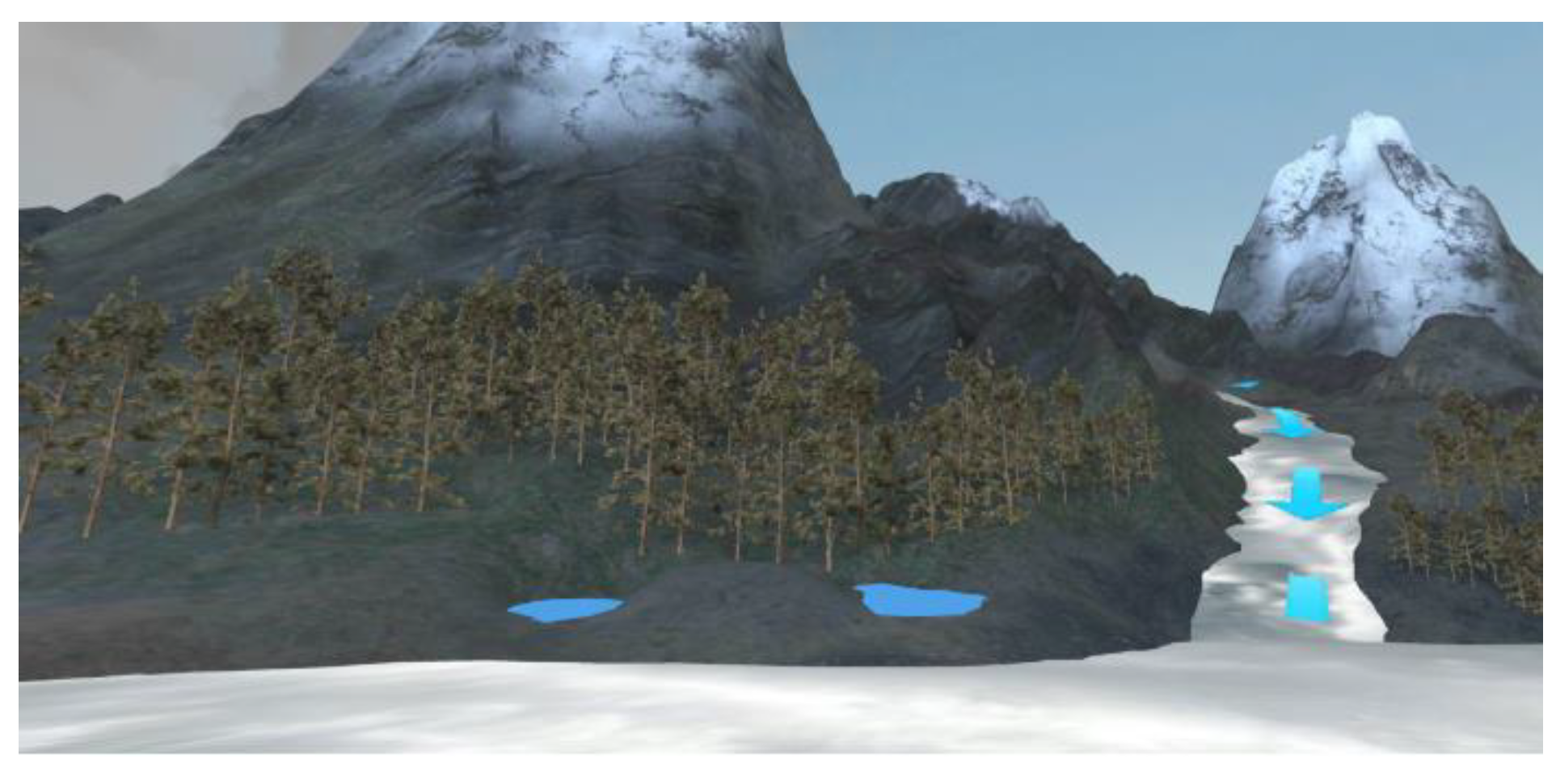

3.2. Second Set of experiments

Therefore, we are currently developing instructional materials targeting higher-order Bloom skills, such as studying the water cycle. In this phase, two third-grade classes with 17 students each were studied, one serving as the control group. The VR group explored an interactive virtual environment for 10 min, showing water phase transformations in nature, using pre-designed material allowing high interactivity. Students can travel through the scene and observe the transformations of water and the conditions under which every transformation occurs, as shown in

Figure 5.

The control group studied the corresponding theory through a text describing water transformations in a playful way (

Figure 6).

Both groups then completed the same assessment sheet within eight minutes (

Figure 7). The assessment sheet used for this measurement included open-ended responses. To ensure the reliability of the measurement, the research team predetermined specific keywords and phrases, the presence of which in the students’ answers awarded points.

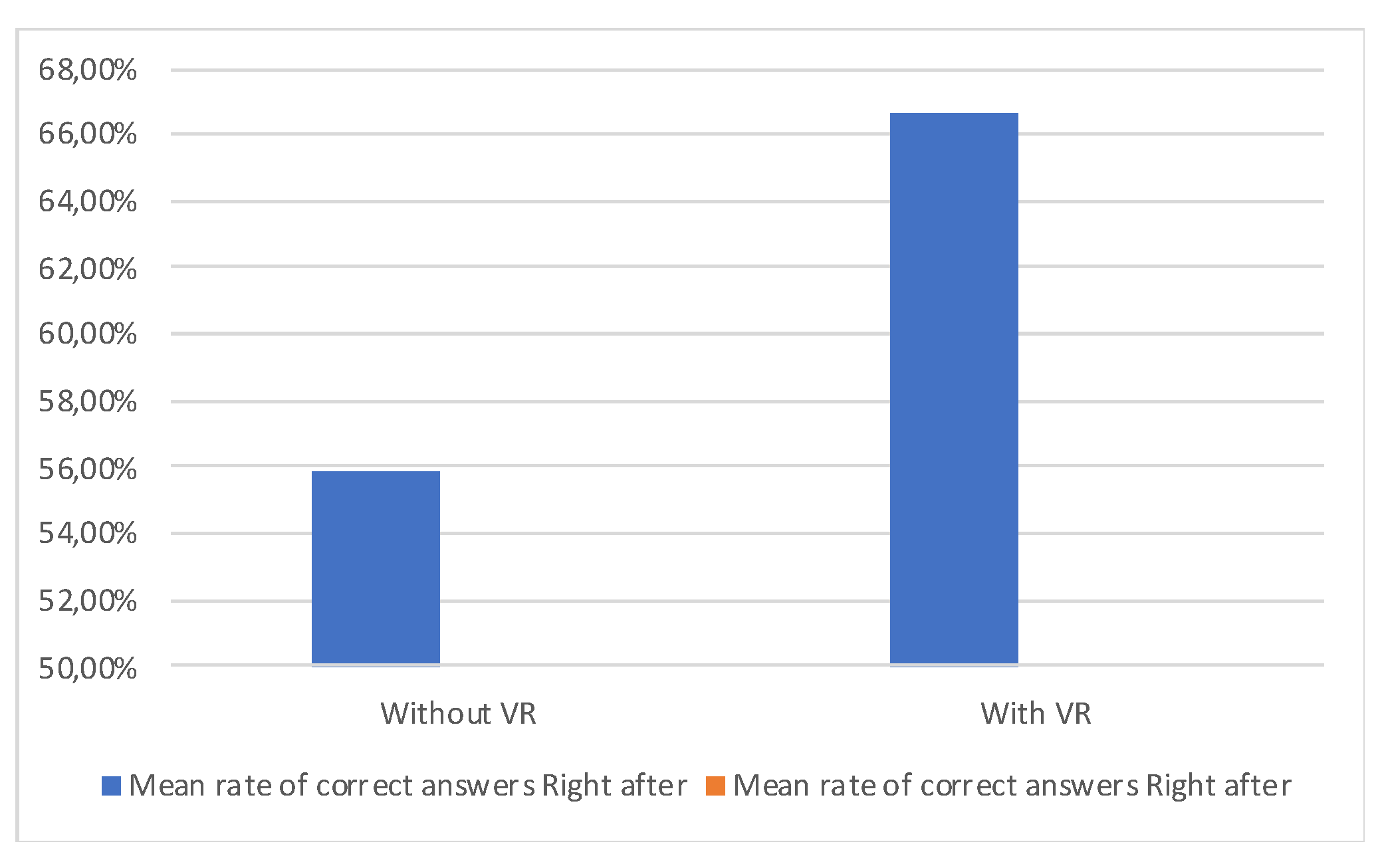

This process is ongoing, but the initial measurements indicate significantly greater discrepancies between the two groups of students, reaching 10.78%, as shown in

Table 3. This greater difference is attributed to the fact that the assessed skills pertain to the second level of Bloom's taxonomy. Moreover, the instructional material was not identical between the two teaching methods but contained the same information. However, VR is more interactive, as the user engages with the environment, providing a comparative advantage for this teaching method.

We do not yet have results regarding the percentage of correct answers from the students one month after instruction, as was the case in the first measurement. This measurement will be conducted in the future.

Figure 8.

Results of teaching with VR and without VR.

Figure 8.

Results of teaching with VR and without VR.

4. Conclusions

The conclusions of this study are still in progress. Several challenges remain in this research. Measuring higher-order skills requires software capable of providing meaningful interactions (e.g., manipulating objects, solving puzzles, and interacting with characters) and a strong sense of presence, which is not always readily available. Both teachers and students require specialized knowledge and content creation skills to maximize VR’s educational potential of VR.

Further measurements must also consider age, general student performance, and preferred learning styles. While the sample size used so far is significant, it is not yet sufficient for fully reliable conclusions to be drawn. Adjustments must also align with the Greek national curriculum.

I believe that this scientific field offers fertile ground for new interdisciplinary research.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my professor at the Department of Informatics and Telecommunications of the University of the Peloponnese, Professor Manolis Wallace, for his invaluable guidance. I would also like to thank my colleagues at the school, Antonia Konstantinopoulou and Ioannis Maltezos, with whom I initiated the use of VR and collaboratively designed and implemented teaching sessions using VR headsets.

References

- Allcoat, D., & von Mühlenen, A. (2018). The effect of virtual reality on learning and retention of knowledge: A meta-analysis. Computers & Education, 126, 172-184.

- Bailenson, J. N. (2018). Experience on demand: What virtual reality is, how it works, and what it can do. WW Norton & Company.

- Dalgarno, B., & Lee, M. J. W. (2020). What are the learning affordances of 3D virtual environments? British Journal of Educational Technology, 51(3), 834-850. [CrossRef]

- Freina, L., & Ott, S. (2015). A literature review on immersive virtual reality in education: State of the art and perspectives. The International Journal of Virtual Reality, 15(2), 1-10.

- Merchant, Z., Goetz, E. T., Cifuentes, L., Keeney-Kennicutt, W., & Kwok, O. (2014). Effectiveness of virtual reality-based instruction on students' learning outcomes: A meta-analysis. Computers & Education, 70, 29-40. [CrossRef]

- Slater, M. (2009). Slater, M. (2009). Place illusion and plausibility can lead to realistic behaviour in immersive virtual environments Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B36435493557 . [CrossRef]

- ClassVR. (2023). ClassVR: Immersive Learning for K-12. Retrieved from https://www.classvr.com/.

- Nadine Bisswang, Dimitri Petrik, Erich Heumüller and Sebastian Richter. What is Your VR Use Case for Educational Like: A State-Of-The-Art Taxonomy - ERIC, πρόσβαση Μαΐου 25, 2025, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1425397.pdf.

- Heba Fasihuddin, Bloom's Taxonomy and VR Technology [5] | Download Scientific Diagram - ResearchGate, πρόσβαση Μαΐου 25, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Blooms-Taxonomy-and-VR-Technology-5_fig2_378257107.

- Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A revision of Bloom's taxonomy: An overview. Theory into Practice, 41(4), 212-218. [CrossRef]

- M. Paolanti, M. Puggioni, E. Frontoni, and R. Pierdicca, “Evaluating Learning Outcomes of Virtual Reality Applications in Education: A Proposal for Digital Cultural Heritage,” ACM Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage, Vol. 16, No. 2, Article 36. Publication date: June 2023. [CrossRef]

- Michael W. Timm , Benefits and Applications of Learning with Virtual Reality, πρόσβαση Μαΐου 25, 2025, https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1851&context=honorstheses.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).