Submitted:

28 September 2025

Posted:

29 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Preparation of the Reference Star Catalog

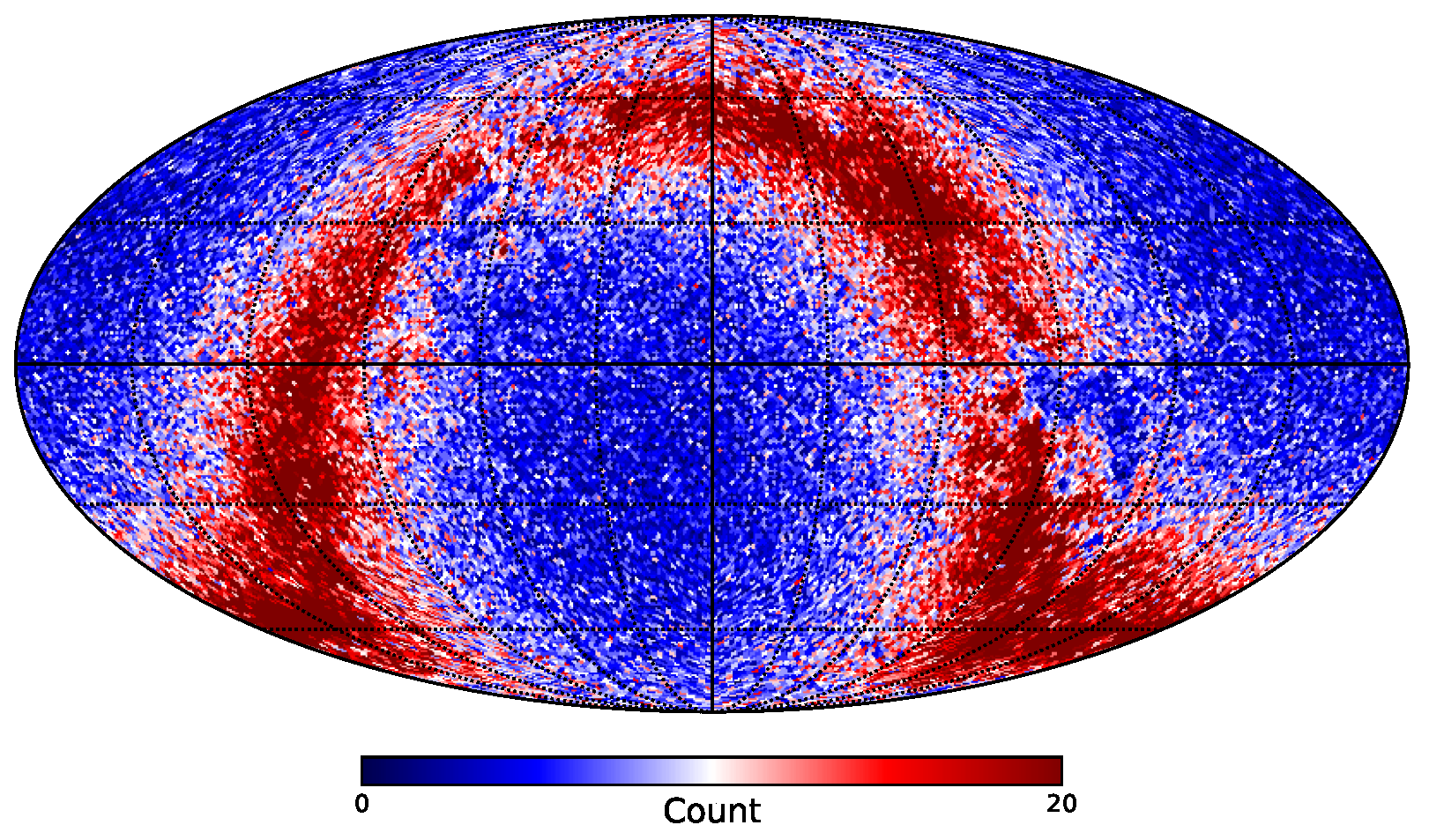

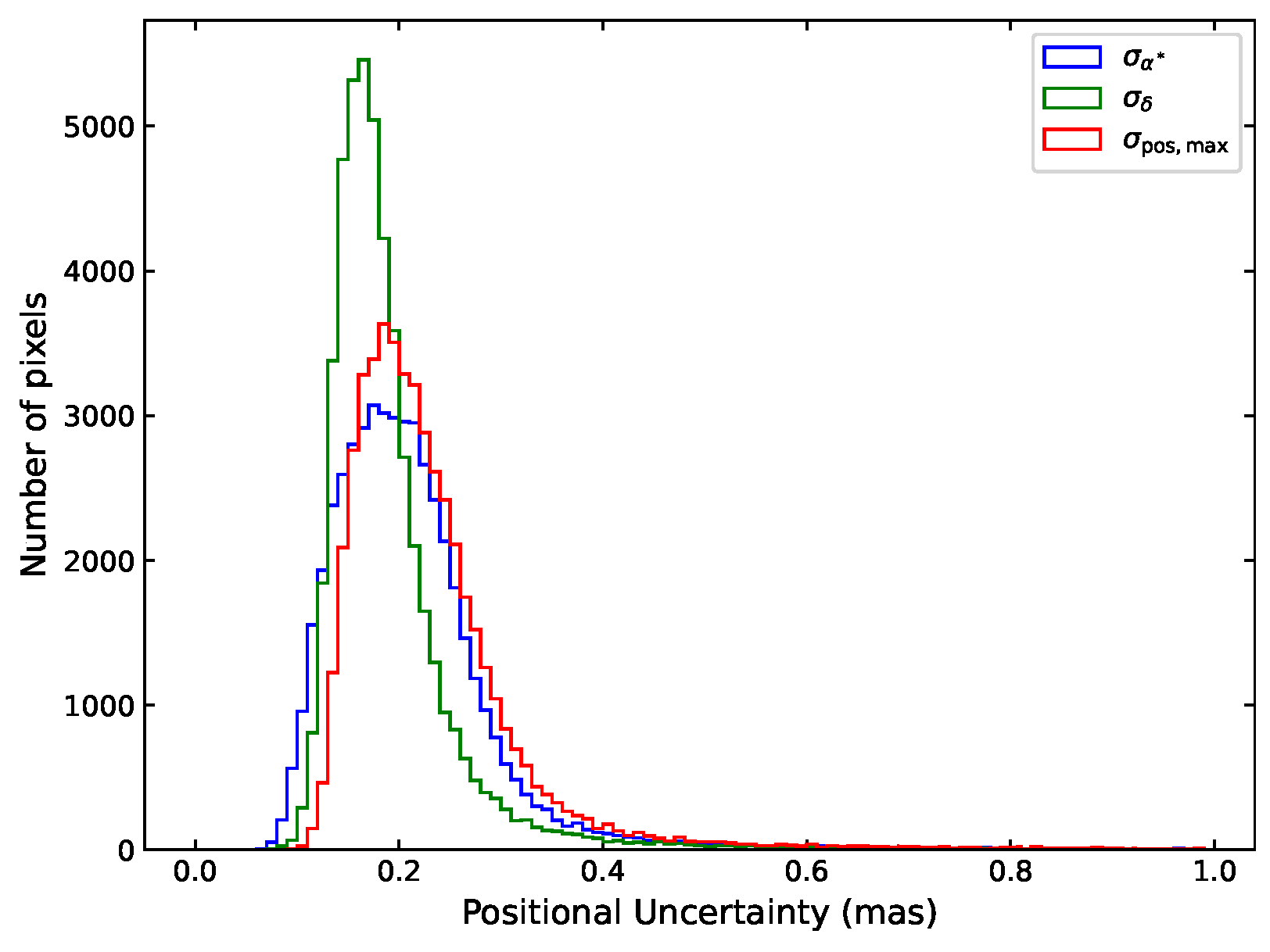

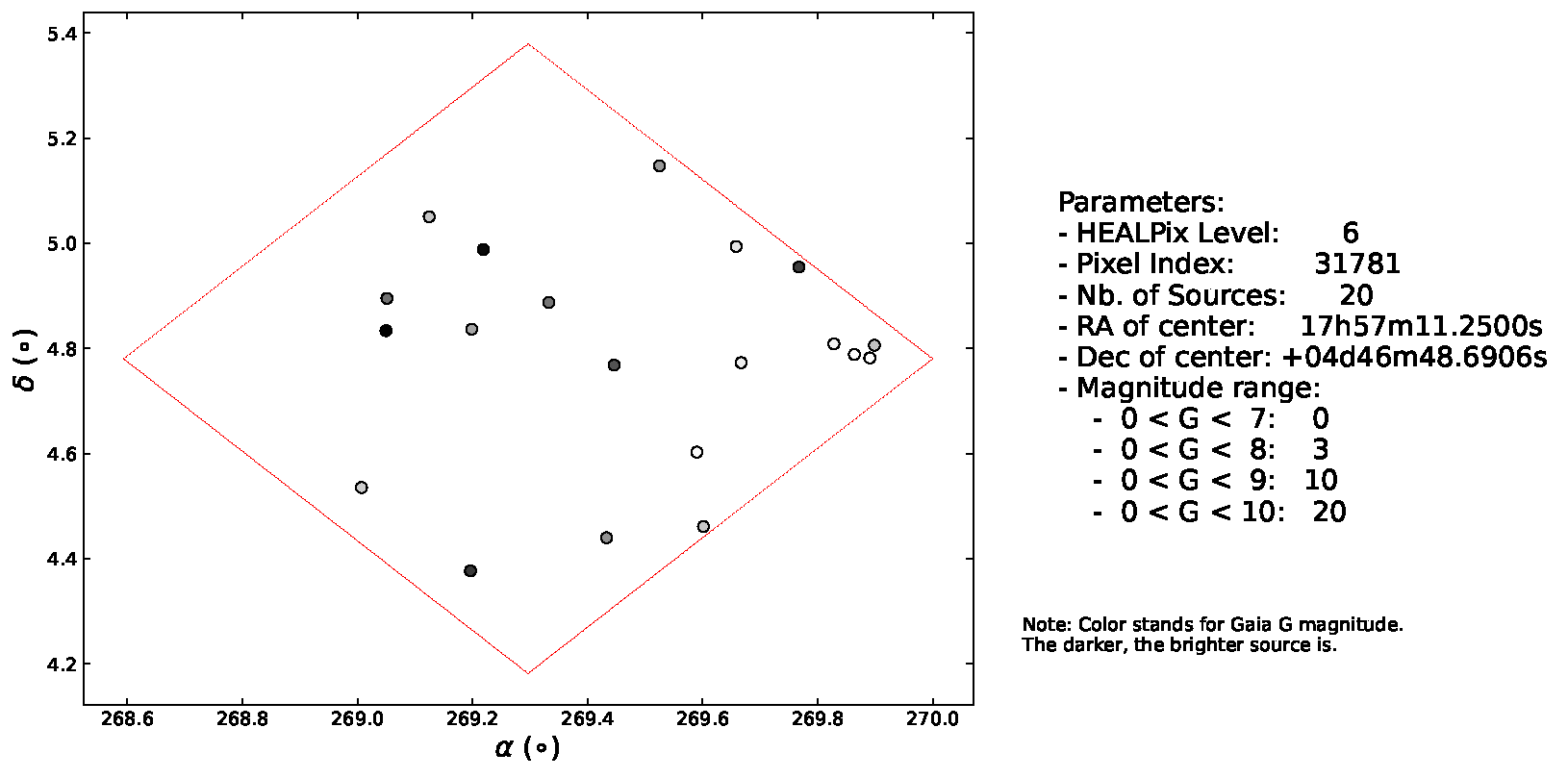

2.1. HEALPix Pixelization

2.2. Epoch Propagation of Navigation Star Positions

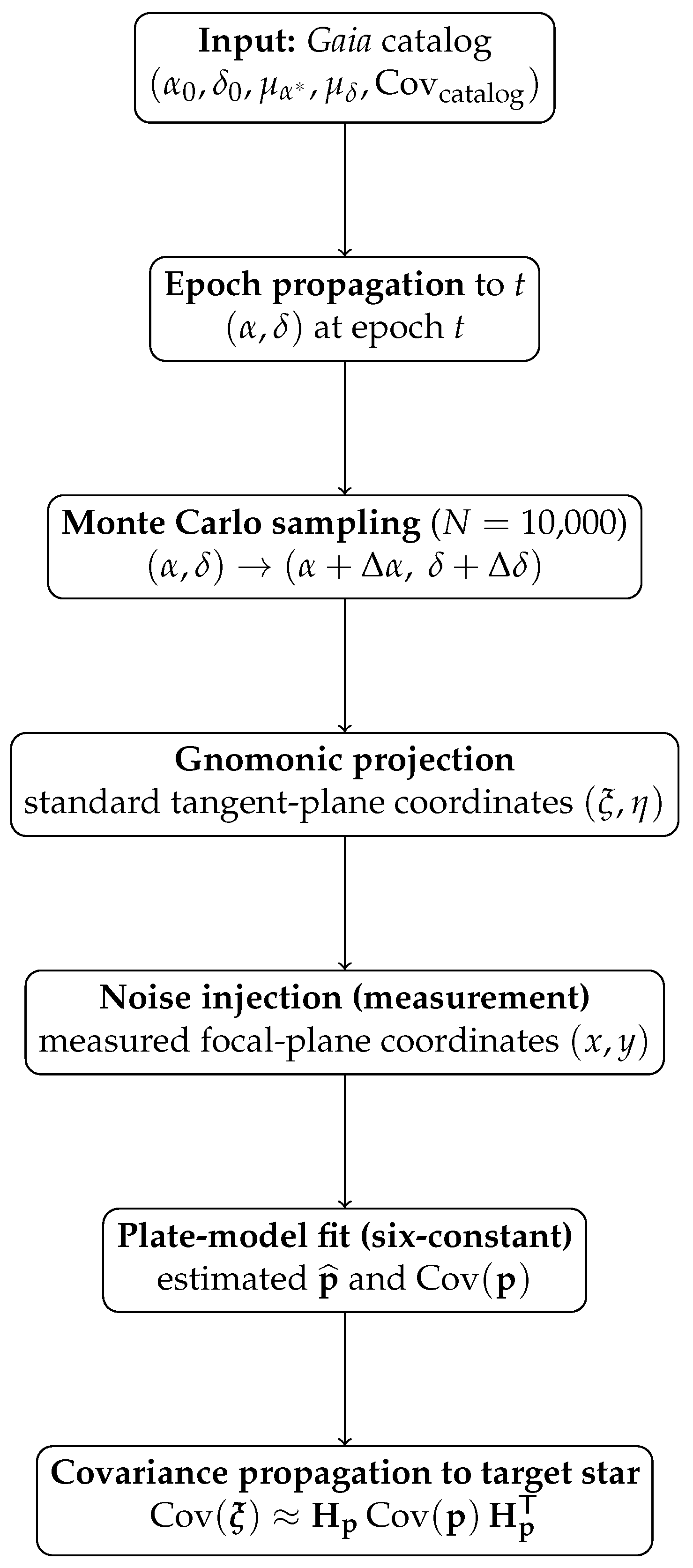

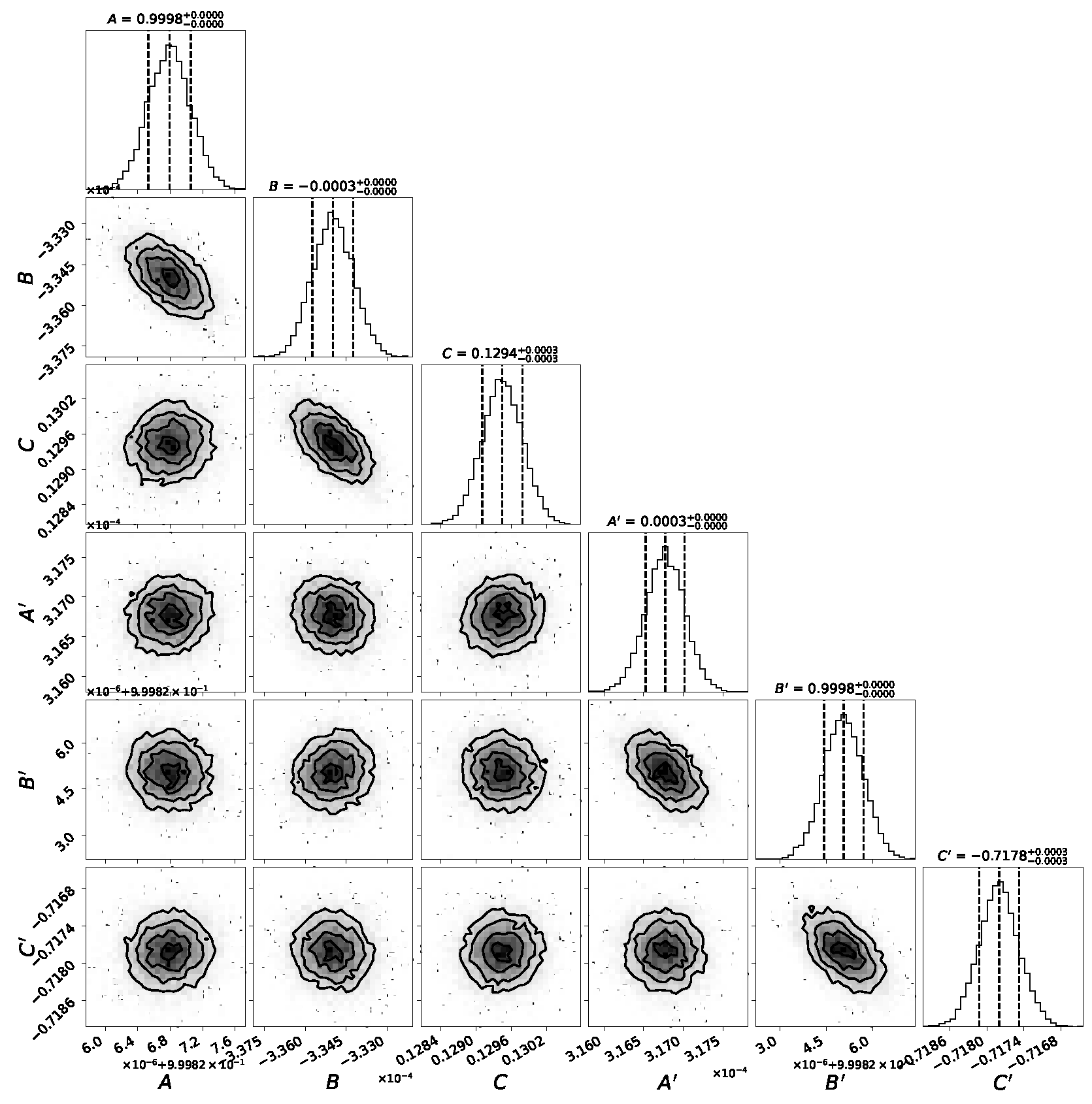

3. Simulation of Plate-Model Error Propagation

3.1. Projection and Plate Model

3.2. Plate-Model Error Propagation

4. Simulation Results and Analysis

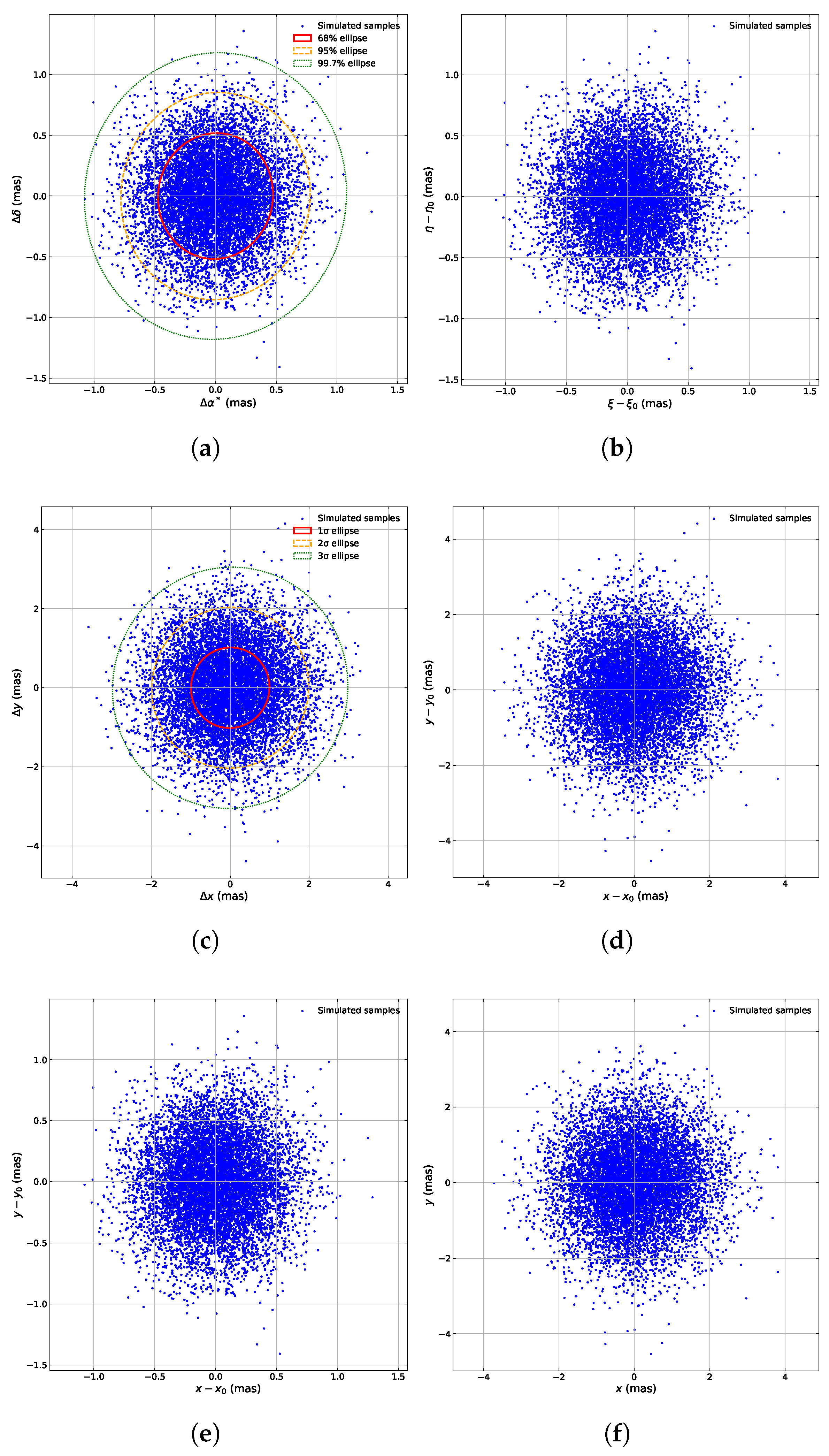

4.1. Single-Star Simulation: Barnard’s Star

- With distortion and noise: distorted coordinates are further perturbed by measurement noise. The final distribution in Figure 4f represents the simulated measured coordinates of Barnard’s Star in a realistic navigation observation.

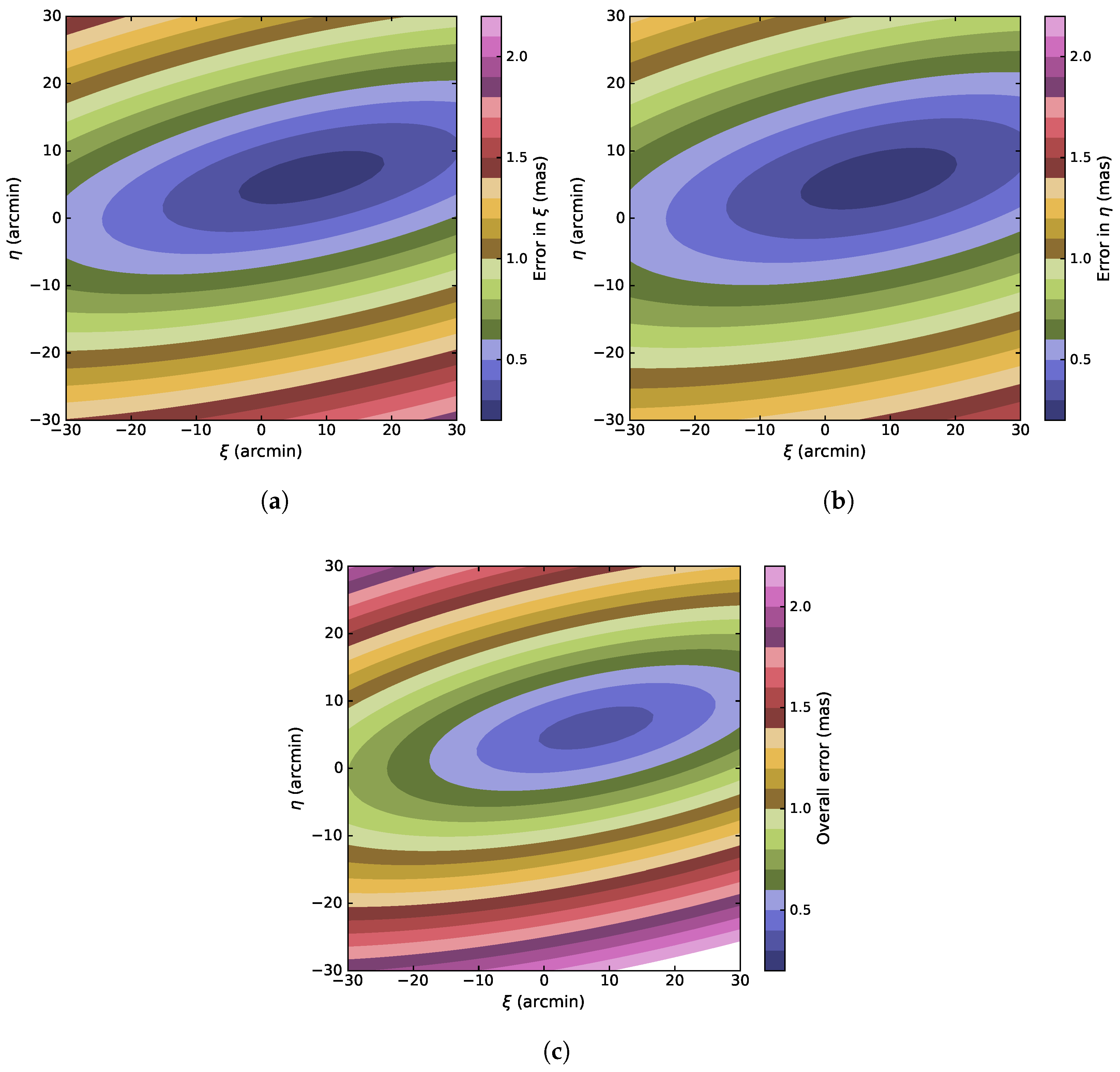

4.2. Plate-Model Error Distribution in a Representative Field

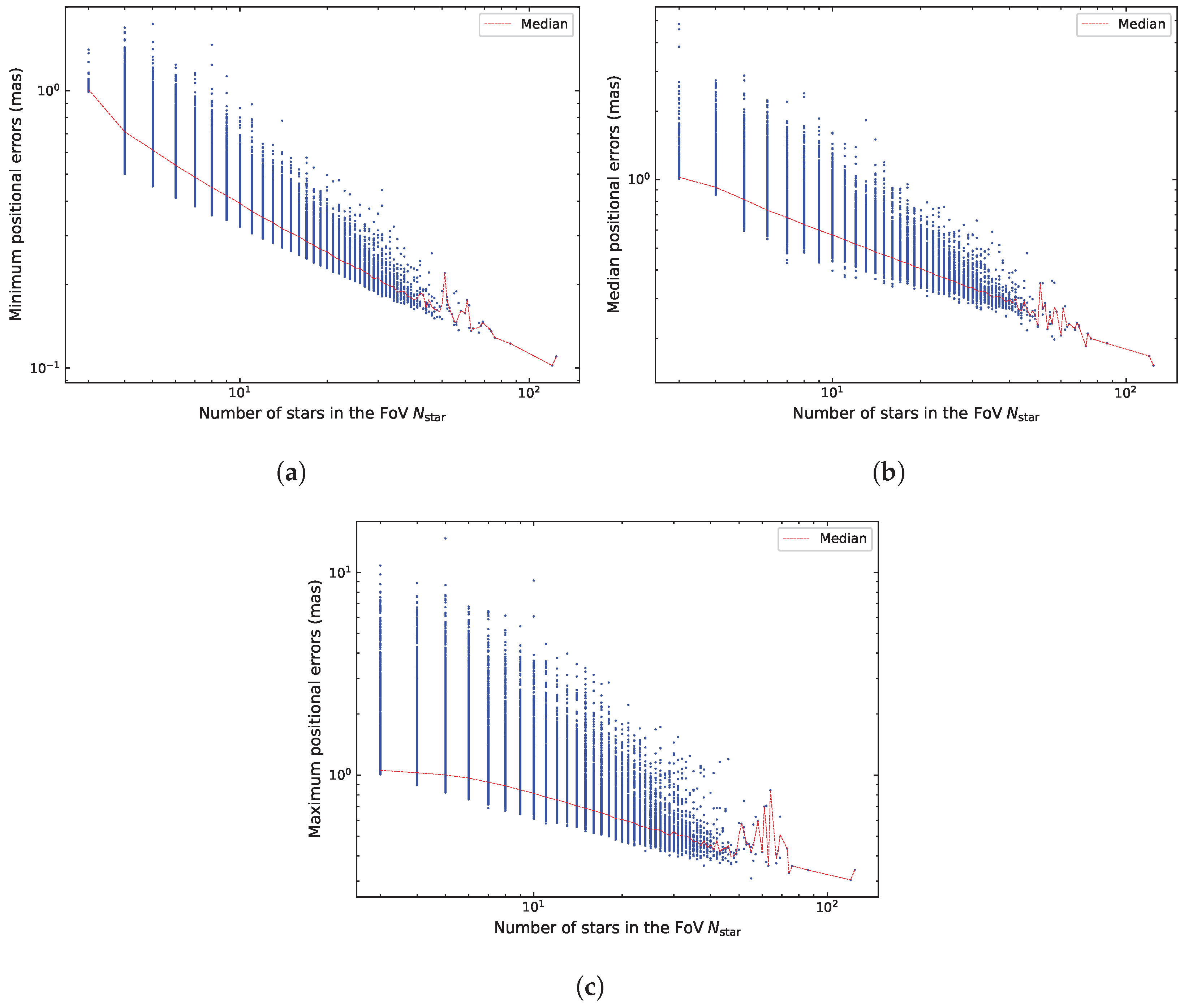

4.3. All-Sky Distribution of Plate-Model Errors

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McKee, P.; Kowalski, J.; Christian, J.A. Navigation and star identification for an interstellar mission. Acta Astronautica 2022, 192, 390–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Ning, X.; Ma, X.; Liu, J.; Gui, M. A survey of autonomous astronomical navigation technology for deep space detectors. Flight Control & Detection 2018, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Xu, J.; Huang, Q.; Chen, X. Survey of Autonomous Celestial Navigation Technology for Deep Space. Flight Control & Detection 2020, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Christian, J.A. StarNAV: Autonomous Optical Navigation of a Spacecraft by the Relativistic Perturbation of Starlight. Sensors 2019, 19, 4064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Sun, J.; Peng, Y.; Liu, J. Observability and Performance Analysis of Spacecraft Autonomous Navigation Using Stellar Aberration Observation. In Proceedings of the 2021 5th International Conference on Vision, Image and Signal Processing (ICVISP), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; 2021; pp. 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, K.; Wei, C.; Zhou, P. Integrated Autonomous Optical Navigation Using Q-Learning Extended Kalman Filter. Aircraft Engineering and Aerospace Technology: An International Journal 2022, 94, 848–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Li, M.; Liu, N. Construction of Aberration Navigation Catalog Based on the Gaia Catalog. Flight Control & Detection 2025. In press. [Google Scholar]

- Gaia Collaboration; Prusti, T.; de Bruijne, J.H.J.; Brown, A.G.A.; Vallenari, A.; Babusiaux, C.; Bailer-Jones, C.A.L.; Bastian, U.; Biermann, M.; Evans, D.W.; et al. The Gaia mission. A&A 2016, 595, A1, [arXiv:astro-ph.IM/1609.04153]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaia Collaboration; Brown, A.G.A.; Vallenari, A.; Prusti, T.; de Bruijne, J.H.J.; Babusiaux, C.; Biermann, M.; Creevey, O.L.; Evans, D.W.; Eyer, L.; et al. Gaia Early Data Release 3. Summary of the contents and survey properties. A&A 2021, 649, A1, [arXiv:astro-ph.GA/2012.01533]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhurina-Platais, V.; Grogin, N.A.; Sabbi, E. Astrometric Calibrations of HST Images in the Era of Gaia. In Proceedings of the American Astronomical Society Meeting Abstracts #232, 2018, Vol. 232, American Astronomical Society Meeting Abstracts, p. 119.13.

- Eichhorn, H.; Williams, C.A. On the systematic accuracy of photographic astrographic data. AJ 1963, 68, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, H.C. Note on the Influence of the Plate Constants on the Accuracy of the Position of an Object measured on a Photograph. MNRAS 1904, 64, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von der Heide, K. On the reduction model of astrographic plates. A&A 1979, 72, 324–331. [Google Scholar]

- Scholz, R.D.; Odenkirchen, M.; Hirte, S.; Irwin, M.J.; Borngen, F.; Ziener, R. Absolute proper motions and Galactic orbits of M5, M12 and M15 from Schmidt plates. MNRAS 1996, 278, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferys, W.H. Quaternions as Astrometric Plate Constants. AJ 1987, 93, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bienayme, O. Field astrometry using orthogonal functions. A&A 1993, 278, 301–306. [Google Scholar]

- Makarov, V.V.; Veillette, D.R.; Hennessy, G.S.; Lane, B.F. The Worst Distortions of Astrometric Instruments and Orthonormal Models for Rectangular Fields of View. PASP 2012, 124, 268, [arXiv:astro-ph.IM/1110.2967]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.W.; Peng, Q.Y.; Wang, N. An improved solution to geometric distortion using an orthogonal method. Research in Astronomy and Astrophysics 2017, 17, 21, [arXiv:astro-ph.IM/1612.05801]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindegren, L.; Klioner, S.A.; Hernández, J.; Bombrun, A.; Ramos-Lerate, M.; Steidelmüller, H.; Bastian, U.; Biermann, M.; de Torres, A.; Gerlach, E.; et al. Gaia Early Data Release 3. The astrometric solution. A&A 2021, 649, A2, [arXiv:astro-ph.IM/2012.03380]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górski, K.M.; Hivon, E.; Banday, A.J.; Wandelt, B.D.; Hansen, F.K.; Reinecke, M.; Bartelmann, M. HEALPix: A Framework for High-Resolution Discretization and Fast Analysis of Data Distributed on the Sphere. ApJ 2005, 622, 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindegren, L.; Lammers, U.; Bastian, U.; Hernández, J.; Klioner, S.; Hobbs, D.; Bombrun, A.; Michalik, D.; Ramos-Lerate, M.; Butkevich, A.; et al. Gaia Data Release 1. Astrometry: one billion positions, two million proper motions and parallaxes. A&A 2016, 595, A4, [arXiv:astro-ph.GA/1609.04303]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Altena, W.F. Astrometry for astrophysics: methods, models, and applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.J.; Peng, Q.Y.; Lin, F.R. Using Gaia DR2 to make a systematic comparison between two geometric distortion solutions. MNRAS 2021, 502, 6216–6224, [arXiv:astro-ph.IM/2108.10478]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).