1. Introduction

Global venture capital investment has experienced dramatic swings in recent years, with a sharp downturn of -35% in 2022 following an outlier peak in 2021 (Partech Partners, 2023; CB Insights, 2023; TechCrunch, 2023). Against this backdrop, African tech startups initially demonstrated resilience – total funding grew 8% in 2022 to reach $6.5 billion across 764 deals (Partech Partners, 2023), even as Africa’s share remained just ~1% of global VC. This relative buoyancy was short-lived: in 2023, amid rising global risk aversion, VC funding to African ventures plummeted by 46% to ~$3.5 billion (Njanja & Kene-Okafor, 2024). Early-stage equity became scarcer, forcing many startups to downscale or shutter (Njanja & Kene-Okafor, 2024). Nevertheless, deal volume held strong, buoyed by accelerators and venture studios “taking in large cohorts” and driving an 11% increase in number of deals despite the funding dip (Njanja & Kene-Okafor, 2024).. These trends underscore Africa’s unique dynamic – youthful entrepreneurial talent and unmet market needs attracting growing investor interest (Partech Partners, 2023), yet structural capital gaps persist, exacerbated by institutional fragilities.

Amid these conditions, university-affiliated accelerators have proliferated across African innovation hubs. Modeled after Silicon Valley accelerators, they offer seed funding, training, and networks to cohorts of startups. In mature ecosystems, evidence on accelerator efficacy is mixed; however, in emerging markets accelerators may be especially pivotal. They are hypothesized to act as market signalers and institutional bridges in environments of high information asymmetry and “voids” – gaps in financing, mentorship, and legal infrastructure (Connelly et al., 2011; Peng, Sun, Pinkham, & Chen, 2009). Prior scholarship highlights that new ventures often struggle to convey credibility to investors when formal institutions (e.g. venture capital networks, robust legal systems) are weak (AfDB, 2022). Accelerators can certify venture quality and build capabilities, helping entrepreneurs overcome these deficits (AfDB, 2022). Indeed, an emerging markets study found that without acceleration, ventures are often unable to attract investment commensurate with their potential, given investors’ trust deficits and entrepreneurs’ experience gaps (Baltazar, 2018). Yet, critical gaps remain in understanding how accelerators function as signals under such scarcity: Do accelerator graduates demonstrably outperform their non-accelerated peers in raising capital? Which venture traits and behaviors (e.g. effectual decision-making) mediate success? And how do contextual factors – such as severe resource constraints, cultural factors, or new technological disruptors – modulate the accelerator’s impact?

Unit of analysis and scope: Throughout this article, the venture is the unit of analysis. Accelerators provide the institutional structure within which ventures operate—quarterly cycles, staged milestone reviews, and demo-day exposure—but they are not the comparative objects of study. Our contribution lies in showing how ventures use accelerator-structured milestones to assemble signal portfolios that reduce information asymmetry under scarcity, and in specifying when resourceful behaviors strengthen or blur those signals. In this framing, accelerators are institutional translators and enablers that scaffold signal production and interpretation rather than the focal units being tested.

Existing literature on entrepreneurship offers partial insights. Signaling theory suggests that accelerators confer observable credentials (e.g. competitive selection, mentorship pedigree) that signal venture quality to investors (AfDB, 2022). Staged financing (real options theory) posits that investors commit capital incrementally – treating initial investments as options to “expand” if startups hit milestones (Hogrebe & Lutz, 2024). Effectuation and bricolage theories describe how entrepreneurs in uncertain, resource-poor settings prioritize available means and improvisation over predictive planning (Fisher, 2012). Additionally, the Triple Helix model of innovation emphasizes synergy between universities, industry, and government, which in Africa’s case might compensate for institutional voids by fostering supportive ecosystems (Lawton & Leydesdorff, 2011). However, there is a dearth of integrated studies applying these theories concurrently to African accelerators. Few works have scrutinized university-led accelerators in the context of Africa’s institutional voids – characterized by weak capital markets, “missing” early-stage investors, and limited formal support structures (AfDB, 2022) or examined how global disruptors (e.g. AI-driven investment tools, new innovation policies) could alter the accelerator-value equation.

Yet, much of the existing research on accelerators has been rooted in OECD contexts, where resource availability, institutional maturity, and formal entrepreneurial ecosystems differ markedly. In contrast, African accelerators operate within complex settings of institutional scarcity and hybrid governance norms, warranting theoretical extension. This paper contributes by showing that what are often termed “institutional voids” may not be empty spaces, but rather dense alternative orders—such as alumni networks, religious communities, and informal financing circles—that serve as substitutive institutions. As such, we engage critically with canonical views (Khanna & Palepu, 1997; North, 1990; Peng, 2003), arguing that the void metaphor may understate the resilience and embeddedness of African entrepreneurial ecosystems (Khanna & Palepu, 1997; Peng, 2003).

1.1. Research Problem:

In sum, we lack a holistic understanding of how ventures inside university-affiliated accelerators convert milestones into credible signals under resource scarcity and signal credibility to investors, and how this process is influenced by entrepreneurial behaviors and evolving contextual disruptors. Addressing this gap is crucial as stakeholders seek to design interventions that maximize the impact of accelerators on inclusive growth and innovation.

1.2. Research Objectives:

This study aims to (1) evaluate the effectiveness of accelerator participation as a signal for venture success (particularly in securing follow-on funding), (2) identify the mechanisms (milestone achievement, network gains, capability-building) through which accelerators influence venture outcomes, (3) analyze the role of entrepreneurial decision-making logics (effectuation, bricolage) in accelerator venture performance, and (4) assess how broader ecosystem factors – including triple helix collaborations and emerging disruptors like AI and policy shifts – moderate these dynamics.

1.3. Research Questions:

To pursue these objectives, we pose five specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time-bound research questions (RQs): RQ1: Signaling efficacy under scarcity — Do ventures graduating from African university-affiliated accelerators achieve significantly better funding and growth outcomes than non-accelerated ventures, and what signals (credentials, investor networks, demo-day exposure, milestone attainment) drive these outcomes? RQ2: Milestones as Real Options – How does the staged financing design of accelerators (quarterly milestones, tranche-based support) affect venture development and investor decision-making? Does meeting accelerator milestones translate into higher likelihood of follow-on investment (realizing the “option” value)? RQ3: Entrepreneurial Resourcefulness – In what ways do entrepreneurs employ effectuation (means-driven strategy) and bricolage (resource improvisation) during acceleration, and how do these approaches impact venture progress and resilience? RQ4: Triple Helix and Institutional Context – How do triple helix dynamics (university–industry–government linkages) within African accelerators help mitigate institutional voids? What role do local context factors (e.g. regional investor pools, cultural trust barriers) play in shaping accelerator outcomes? RQ5: Future Disruptors and Evolution – How might emerging disruptors – such as generative AI, open innovation platforms, or new pro-startup policies (e.g. the African Continental Free Trade Agreement [AU, n.d.], startup acts [Ecosystem.build, 2023; i4Policy, 2020]) – influence the efficacy and design of university-affiliated accelerators over the next 10–15 years?

1.4. Hypotheses:

Corresponding to these RQs, we formulate several testable hypotheses: H1 – Accelerator participation has a positive effect on post-program funding raised (accelerated ventures > non-accelerated, ceteris paribus), especially in capital-scarce settings (signaling effect). H2 – Milestones as signals and options. The completion of accelerator-structured milestones both clarifies external signals of venture viability and triggers option exercise by investors, increasing the likelihood of follow-on funding and subsequent revenue growth.. H3 – Ventures with higher effectuation and bricolage orientation (measured via our indices of improvisation and pivoting) show equal or greater performance gains in the program compared to those following rigid planning (resourcefulness effect). H4 – The impact of accelerator signals on funding is moderated by institutional context: in environments with greater institutional voids (weak investor networks, information asymmetries), accelerator signals yield stronger investor responses (heightened relevance of signals). H5 – Emerging disruptors (AI tools, new government funding schemes) will significantly alter accelerator models and venture outcomes in the coming decade, potentially requiring hybrid approaches (e.g. AI-driven mentorship, public-private co-funding) – a hypothesis we explore qualitatively through foresight scenarios.

Crucially, we also consider potential disruptors and “unknown unknowns” that could invalidate or nuance these hypotheses – for instance, a sudden influx of global VC or pan-African angel networks (policy or market shifts), or widespread adoption of AI in due diligence lowering the value of traditional signals. By articulating these RQs, hypotheses, and disruptors, we set a clear, bounded scope for investigating accelerator-led venture development in Africa’s entrepreneurial ecosystems.

Contribution: The study advances early-stage entrepreneurial signaling theory for scarcity contexts by theorizing a signal–noise paradox at the venture level; it treats effectuation and bricolage as behavioral mechanisms that produce milestones under constraint; it reads accelerator staging through the lens of real options; and it positions triple-helix and institutional-voids as contextual moderators that shape the salience and legibility of signals. We label this tension the signal–noise paradox: bricolage- or effectuation-driven milestones that sustain ventures can simultaneously appear noisy or ambiguous to outside investors, inviting theory refinement for emerging-market contexts.

2. Theoretical & Conceptual Framework

This study is anchored in signaling theory as the primary lens for understanding how early-stage ventures make quality legible under scarcity. We treat effectuation and bricolage as behavioral mechanisms that enable milestone creation when resources are thin; we read staged financing/real options as the process logic that links milestones to investor action; and we position triple-helix collaboration and institutional-voids as contextual moderators that amplify or dampen signal salience.

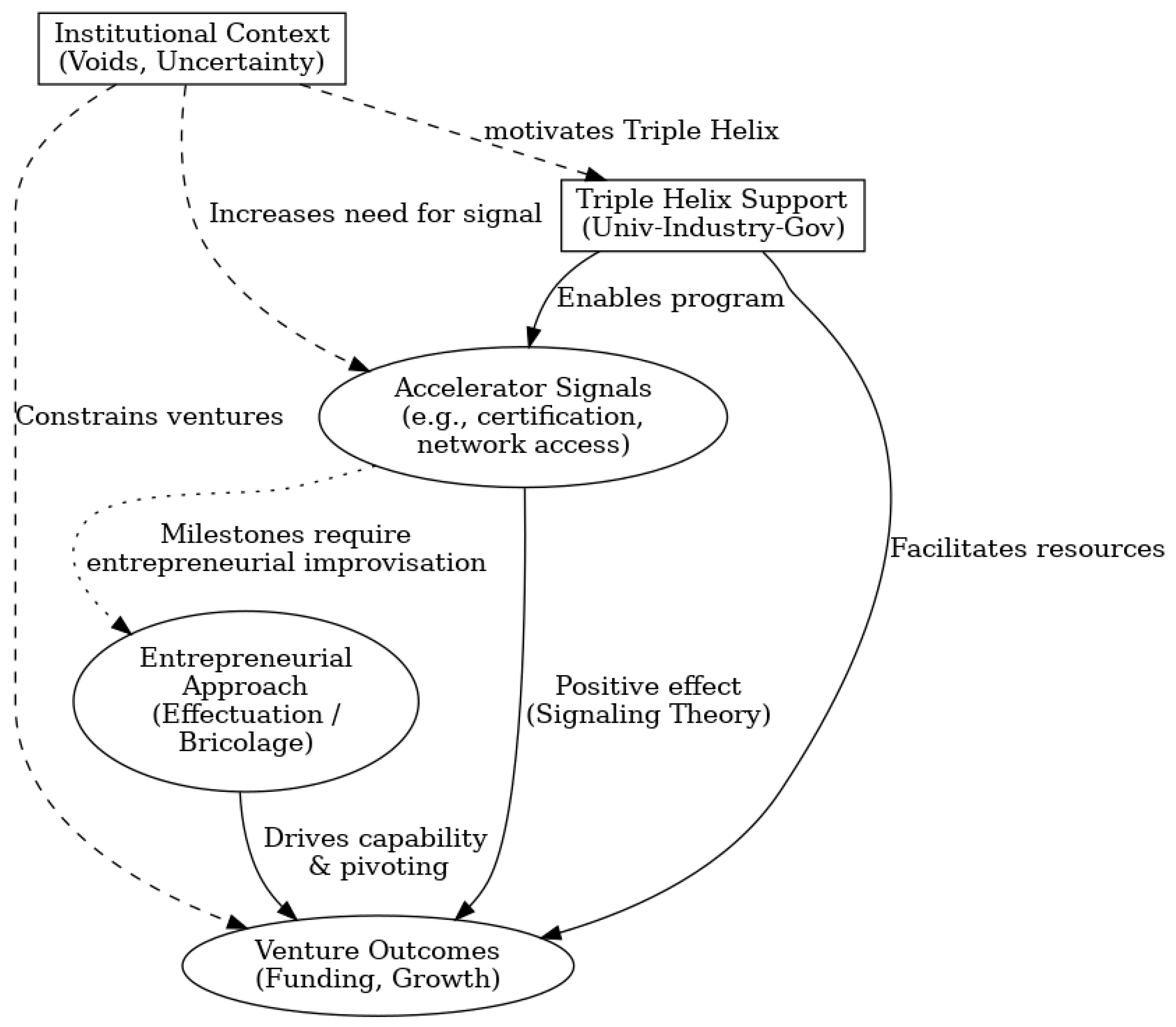

Figure 1 presents the conceptual model with signaling at the center and the other lenses layered as mechanisms, process, and context.

2.1. Signaling Theory:

Originally developed by Spence (1973) in the job market context, signaling theory in entrepreneurship posits that startups send observable signals to overcome information asymmetry and convince resource holders of their quality (Spence, 1973; AfDB, 2022). In our context, accelerator acceptance and graduation act as signals – ventures in reputable university programs benefit from certification of vetting, mentorship from known experts, and association with a credible institution. These signals can attract investors, partners, and customers who lack other reliable information about the new venture. Prior research indeed finds that accelerated businesses tend to raise significantly more capital than comparable non-accelerated ones (Baltazar, 2018; González-Uribe & Leatherbee, 2018), suggesting that the accelerator’s “stamp of approval” is valued in emerging markets. However, signaling effectiveness may vary: extremely high-quality ventures might even avoid accelerators to signal confidence (a countersignaling effect [Connelly et al., 2011]), as seen in some mature markets (Browne et al., 2024). In Africa’s context, we propose Proposition 1: Accelerator affiliation provides a positive quality signal that increases venture funding prospects, especially where alternative credibility indicators (e.g. prior startup successes, robust IP protection) are lacking. This aligns with the idea that accelerators serve as institutional intermediaries, conferring status and bridging trust gaps in “immature markets” (AfDB, 2022). Additionally, emerging work suggests that signaling is deeply context-contingent. For instance, Browne et al. (2024) found evidence of countersignaling among elite FinTech ventures in OECD markets—where declining accelerator participation signals confidence. By contrast, in African settings where alternative signals are limited, accelerator affiliation may retain higher signaling potency. This asymmetry urges a contextual reconceptualization of the signaling landscape across institutional environments. Accordingly, we treat accelerator-structured milestones as the primary observable signals, assemble them into a Signal-Portfolio Index, and test whether investors respond differentially to their clarity and strength at the venture level.

While the three lenses appear complementary, they also collide. Signaling relies on externally legible markers vetted by third parties, whereas bricolage and effectuation valorize internally improvised solutions that may look frugal—or even amateurish—to outsiders. This clash creates what we call the “signal-noise paradox”: the very improvisation that helps founders progress under constraint can generate weak or ambiguous signals that sophisticated investors misread as incapacity. Surfacing this paradox foregrounds a critical tension absent in prior accelerator studies and sets the stage for examining when bricolage amplifies rather than attenuates signal credibility. Extending this paradox, we theorize a countersignaling zone in which top-tier African ventures eschew accelerators to telegraph self-sufficiency, thereby inverting the usual positive inference attached to affiliation.

2.2. Staged Financing & Real Options:

Venture capital financing is often staged – investors inject capital in rounds contingent on performance milestones. Real options theory conceptualizes each stage as an option: an initial investment grants the investor the right (but not obligation) to make a follow-on investment if the venture “proves” itself (Hogrebe & Lutz, 2024). In our setting, the “exercise” decision by investors is conditional on venture-level milestone signals that reduce uncertainty sufficiently to justify follow-on capital. Accelerators mirror this logic on a micro scale. They typically provide small seed funding and resources upfront, then expose ventures to a network of investors at demo days. Follow-on investment is conditional on ventures hitting technical or traction milestones (Hallen, Cohen, & Bingham, 2020). This embodies a real options approach: stakeholders can abandon or double-down after observing milestone outcomes. Our conceptual model posits Proposition 2: Achievement of accelerator milestones (product development targets, pilot users, etc.) serves as an exercisable option that significantly increases the likelihood of subsequent investment. We expect to observe that ventures which met or exceeded their quarterly goals (as tracked in our dataset) attracted disproportionately more investor interest than those that didn’t, reflecting rational option exercise. Conversely, if milestones are missed, accelerators might curtail support or investors withdraw – analogous to option expiration. This dynamic ties into signaling: meeting milestones sends a credible signal of venture viability that justifies further funding. It also resonates with agency theory concerns – staged financing mitigates risk of founder moral hazard by requiring stepwise validation.

2.3. Effectuation and Bricolage:

Rather than a competing theoretical frame, effectuation and bricolage serve here as the micro-behavioral engines of signal production, explaining how ventures meet milestones credibly despite severe constraints. Effectual entrepreneurs start with given means (skills, networks, small amounts of money) and iteratively “co-create” opportunities with stakeholders, rather than executing a pre-written plan. Key principles include affordable loss (limiting downside risk) and leveraging contingencies. Bricolage, closely related, is defined as “making do by applying combinations of resources at hand to new problems and opportunities” (Fisher, 2012). In plainer terms, bricoleur entrepreneurs refuse to be constrained by resource limitations, instead recombining whatever is available to solve challenges (Fisher, 2012). For example, rather than waiting for an ideal tool or funding, a bricoleur will use spare parts to build a prototype. In African accelerators, we anticipate effectuation and bricolage to be not just common but necessary. Entrepreneurs often operate amid severe capital scarcity and infrastructural gaps, so they improvise solutions (bricolage) and adapt goals on the fly (effectuation) to progress. This is consistent with concepts of frugal innovation, where creating affordable solutions under resource constraints goes hand-in-hand with entrepreneurial bricolage (Manishimwe et al., 2024). We advance Proposition 3: Entrepreneurs who actively employ effectuation (means-driven adaptation) and bricolage (resource improvisation) during acceleration will achieve stronger milestone performance and venture traction than those who rigidly adhere to pre-set plans. These behaviors amplify the benefits of accelerator support – for instance, a founder might leverage a part-time faculty advisor and repurpose open-source tools to meet a product demo deadline (bricolage), or pivot target customer segments after early feedback (effectuation), thereby demonstrating agility and making the most of limited budgets.

2.4. Triple Helix and Institutional Voids:

The Triple Helix model (Etzkowitz & Leydesdorff, 2000) provides a macro-framework by highlighting how universities, industries, and governments interact to spur innovation. In innovation-rich regions, these three spheres collaborate closely (e.g. research commercialization, public R&D grants, industry mentorship). In much of Africa, however, institutional voids prevail – formal venture capital markets, seed funding mechanisms, and regulatory support for startups are nascent (AfDB, 2022). University-affiliated accelerators can thus be seen as a triple helix mechanism to fill those voids: the university contributes knowledge and credibility, industry partners (corporates, angel investors) provide market linkage and mentorship, and government often underpins programs via policy or funding. For example, in Ethiopia and Brazil, the Triple Helix concept was explicitly embraced as a strategy to launch incubators and accelerators, embedding enterprise formation in university contexts (Lawton & Leydesdorff, 2011; Saad & Zawdie, 2008). These collaborations compensate for missing private capital by leveraging academic and public resources. We posit Proposition 4: Triple helix engagement enhances accelerator effectiveness – ventures in accelerators that actively integrate university research, industry expertise, and government support (e.g. grants, innovation policies) will show higher “governance readiness” and investor trust, mitigating the adverse effects of institutional voids. Essentially, accelerators can create a micro-ecosystem of trust and capabilities around ventures, substituting for weak institutions (AfDB, 2022). However, context matters greatly. African ecosystems are diverse and complex, often requiring localized approaches. As Dr. Samuel Mathey, an African entrepreneurship expert, cautions, “people living in Africa [are so diverse]… there is little chance that a unique, static model can fit everywhere every time.” (AfDB, 2022). This underscores that accelerators and triple helix initiatives must be tailored to local conditions (cultural norms, regional industry strengths) rather than importing one-size-fits-all models.

Bringing these elements together, our conceptual model (

Figure 1) illustrates how micro-level venture actions and signals link to meso-level accelerator processes and macro-level institutional context. We test and refine this model with our empirical analysis. The propositions above guided our inquiry, shaping both the quantitative hypotheses and qualitative exploration of alternative explanations (e.g. instances where signals failed or bricolage backfired). By integrating multiple theories, we aim to provide a richer explanation than any single lens could – acknowledging, for instance, that a venture’s success might require both sending the right external signals (per signaling theory)

and internally improvising effectively (per effectuation/bricolage), within a supportive triple helix environment that counteracts external voids.

Situating accelerators within institutional-voids theory (Khanna & Palepu, 2010; North, 1990) clarifies their role as institutional intermediaries (Peng, Sun, Pinkham, & Chen, 2009). In African ecosystems where formal contracting, disclosure, and investor-protection institutions are thin, accelerators substitute for market intermediaries by certifying quality, orchestrating networks, and socializing governance norms. This reframing allows us to ask not merely whether accelerators help ventures, but what category of missing institution they partially replace, complement, or distort.

3. Methodology

A mixed-methods research design was employed, blending quantitative analysis of venture performance data with qualitative comparative analysis and foresight techniques. This approach was chosen to capture the multifaceted phenomena at hand – from measurable funding outcomes to configurational and forward-looking insights – thereby enhancing the study’s robustness and relevance for theory and practice. Below, we detail our data, measures, and analytical techniques, as well as considerations of validity, ethics, and bias.

3.1. Data and Sample:

The empirical core of the study is a proprietary dataset of quarterly, venture-level data from African university-affiliated accelerators. The dataset comprises 17 tech ventures enrolled across several accelerator cohorts (spanning 2024–2025), each associated with a university-based incubation hub in East and West Africa (names of specific institutions omitted for confidentiality). For each venture, detailed milestone tracking data was collected over time, yielding 185 venture-quarter observations. Analytically, all models are specified at the venture-quarter level with venture fixed effects; accelerator-program identifiers enter only as contextual strata (calendar-time dummies and cohort controls), consistent with our venture unit of analysis. The data fields include: Milestone category and description (e.g. Product Development: “Complete MVP prototype”), financial and non-financial key performance indicators (KPIs) for that milestone (e.g. revenue growth, user acquisition, partnership agreements), and budget allocations. For instance, AfyaWave Ltd, a Rwandan healthtech startup in our sample, had Q1–Q2 2025 milestones in product development (software version releases) and clinical validation, with associated budgets (~$18k per quarter) and KPIs (recruitment of trial participants, etc.) documented. We supplemented this accelerator dataset with secondary sources on venture outcomes (e.g. whether the startup raised external funding by program end, follow-on investment amounts) gathered through press releases and investor databases. Additionally, qualitative information was obtained via interviews with accelerator managers and mentors (n=10) and review of program reports, which provided context on each venture’s progress and challenges.

3.2. Index Construction:

To quantify complex constructs for analysis, we developed several composite indices from the raw data: -

3.2.1. Governance-Readiness Index (GRI):

This index measures the venture’s operational and governance maturity at program end. It aggregates indicators such as completion of finance/legal milestones (e.g. business registration, financial controls), presence of advisory board or legal counsel (binary from non-financial KPIs), and internal policy development (HR policies, IP filings). Each component was standardized and weighted equally to form the GRI (scale 0 to 1). A higher GRI implies a venture is structurally prepared for investor scrutiny (a proxy for decreased institutional risk).

3.2.2. Signal-Portfolio Index (SPI):

We captured the breadth and strength of signals a venture accumulated. Components included: number of investment/fundraising milestones attempted (e.g. pitch days, investor meetings), partnership deals or Memoranda of Understanding signed (as recorded in milestones, e.g. securing an MoU with a manufacturing partner – a signal of commercial validation), awards or prizes won during the period, and third-party endorsements (like media mentions via the university). Each venture’s signals were tallied and adjusted for quality (e.g. an equity investment commitment scored higher than a mentor meetup). SPI thus reflects how rich a venture’s “signal portfolio” is by graduation.

3.2.3. Effectuation/Bricolage Score:

Since effectuation and bricolage are behavioral, we constructed a qualitative score based on content analysis of milestone descriptions and mentor notes. Two independent coders rated each venture on dimensions such as flexibility (e.g. pivoting product or market in response to feedback), resourcefulness (e.g. repurposing existing tools, leveraging personal networks for tasks), and affordable loss mindset (e.g. frugal budget management, focus on critical milestones over expansive plans). Using a codebook drawn from Sarasvathy’s and Baker & Nelson’s definitions, ventures were scored 0 (low evidence) to 2 (high evidence) on each dimension, summing to a composite out of 10. Inter-coder reliability was >0.8. For example, a venture that improvised a prototype using free open-source software and negotiated a revenue-sharing deal instead of upfront capital scored high on bricolage.

3.2.4. Outcome Measures:

The primary outcome was Follow-on Funding within 6 months post-accelerator (in USD, logged), and secondary outcomes included Revenue Growth (percentage increase from pre- to post-program) and Employment Growth (new full-time hires). We also noted a binary Success indicator if the venture secured any external equity or debt investment post-program (beyond the accelerator’s seed).

3.3. Quantitative Analysis:

We first conducted panel data regression analyses to test H1–H4. Specifically, a venture-level fixed-effects regression was used to control for time-invariant heterogeneity across ventures (e.g. founding team experience, sector) that could bias results. The model regressed follow-on funding (and other outcomes) on key independent variables: Accelerator participation (a dummy for being in the program – relevant in comparisons with a control group of similar applicants who were not accelerated, where data was available via GALI benchmarks), the Signal-Portfolio Index, and the Governance-Readiness Index, along with time dummies for each quarter (absorbing common shocks). For the accelerator sample alone (no non-accelerated control), we utilized within-venture variation: e.g. quarterly changes in signals or KPIs predicting eventual funding. We also estimated a random-effects tobit model for follow-on funding (since many ventures had zero external funding, censoring at zero) as a robustness check. To examine milestone effects (H2), we introduced a time-varying variable for milestone achievement rate (% of milestones met each quarter) and its interaction with an indicator for “investor present at demo day” to see if hitting milestones mattered more when investors were watching (a proxy for option exercise conditions).

Additionally, we used Event Study analysis around the accelerator Demo Day event. We treated demo day (when ventures pitch to a wide investor audience) as time zero and plotted the average cumulative funding raised in the months before and after. This visual analysis, with confidence intervals, helped isolate the timing of funding infusions relative to acceleration (to discern a signaling “shock” at demo day). We also conducted difference-in-differences tests using the quasi-control group of rejected accelerator applicants (data sourced from GALI’s public briefs), comparing their funding trajectory to that of accelerated ventures over the same period – which strengthens causal inference that the accelerator (and not just venture quality) drove the differences. Consistent with prior findings(Baltazar, 2018), accelerated ventures significantly outperformed rejected ones in equity raise, which bolsters our quantitative results.

3.4. Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA):

Given the small-to-medium sample size (17 cases) and our interest in multiple causal pathways, we employed fuzzy-set QCA to complement regressions. We calibrated key conditions (causal factors) into fuzzy sets, for example: High Signal Portfolio (SPI above median = 1, slightly below median = 0.67, etc.), High Bricolage (top 5 ventures on bricolage score = 1, middle = 0.5, low = 0). Outcome was set as Successful Outcome (substantial funding or revenue growth achieved). QCA analysis enabled identifying combinations of conditions that sufficed for success. For instance, one solution pattern that emerged was: {High SPI AND High Effectuation Score AND University research link present} → Success, suggesting that ventures signaling well, improvising internally, and leveraging a university lab or IP were consistently successful. Another pathway showed {High SPI AND Strong Triple Helix support AND Lower institutional void (i.e. in a country with stronger startup laws)} → Success, underscoring context moderation. These configurations provide nuanced insight beyond linear models – e.g. a venture could still succeed with low signals if it had extremely strong bricolage and intensive government support (an alternate pathway). We triangulate such findings with individual case narratives.

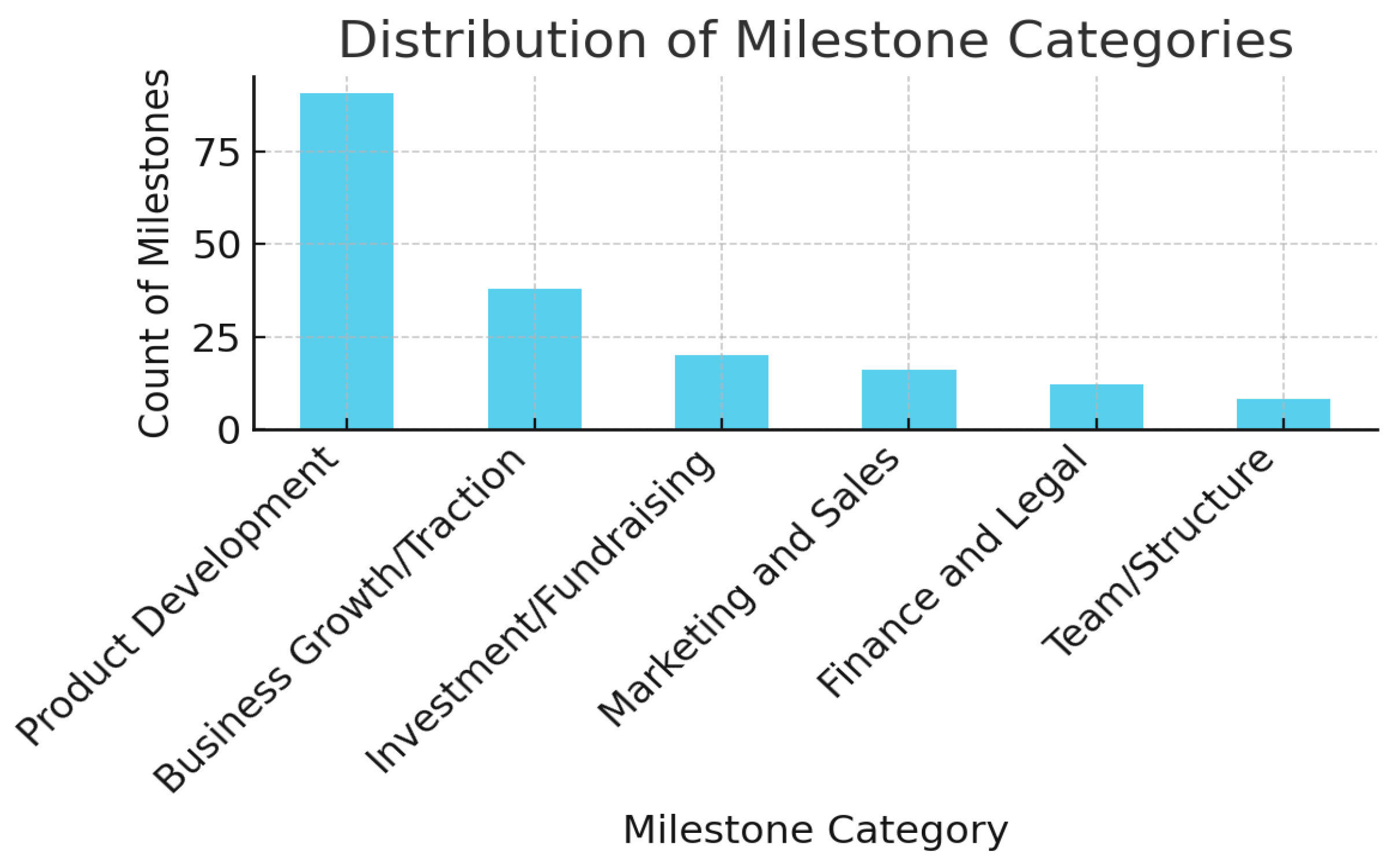

Figures and Tables: We present selected visualizations in APA style within the Findings. Notably,

Figure 2 depicts the distribution of milestone focus areas across ventures, which informs our discussion on accelerator priorities and potential gaps.

3.5. Robustness and Bias Checks:

We performed several robustness checks. To address potential selection bias (accelerators might select inherently stronger ventures), we incorporated the aforementioned control group and also ran models controlling for the venture’s baseline characteristics (e.g. initial revenue, team size) where data were available. We also tested alternative model specifications: a Poisson regression for count-based outcomes (e.g. number of investor offers received), and jackknife resampling given the small N (to ensure no single venture unduly influenced results). The core findings remained consistent. Endogeneity was considered – for example, high signals could be both a cause and effect of venture quality. We attempted an instrumental variable approach, using the venture’s initial university affiliation or research origin as an instrument for signal strength (on the logic that a spin-out from a top university might attract attention regardless of accelerator activity). The IV results, while cautious due to small samples, aligned with OLS, suggesting our key relationships are not artifacts of reverse causality. Nonetheless, these methods cannot fully purge selection bias inherent in quasi-experimental designs. We therefore frame all statistical associations as patterns consistent with theory rather than definitive causal claims, and we encourage cautious interpretation, particularly where omitted venture characteristics may correlate with both accelerator participation and outcomes.

3.6. Data Validity and Ethics:

All data were obtained with permission. The accelerators provided venture data under a data-sharing agreement, with any sensitive information (e.g. specific financial figures, personally identifiable information of founders) anonymized or aggregated. In presenting results, we refer to ventures by pseudonyms or generically (to protect confidentiality and comply with research ethics protocols). We cross-verified self-reported metrics (like revenue) with any available external info (e.g. investor due diligence reports) when possible to ensure accuracy. Data integrity was high, though we acknowledge some indicators (like “Non-financial KPI” descriptions) were subjective. Triangulation via mentor interviews helped validate whether, for example, a milestone was truly completed satisfactorily.

3.7. Potential Biases:

We remain aware of biases such as survivorship bias – ventures still active by program end are analyzed, whereas ones that dropped out early (if any) are not fully observed. This could inflate success metrics. However, in our sample, only 1 venture discontinued the accelerator, and we include it in analysis (marked as zero outcome). Confirmation bias in qualitative coding was mitigated by using independent coders and looking for disconfirming evidence (cases where high signals did not lead to funding, etc.). Cultural bias was also considered: our interpretation of effectuation/bricolage might be influenced by Western theory lenses, so we consulted local experts to ensure, for example, that what we coded as “improvisation success” aligns with local perceptions of entrepreneurial ingenuity.

In summary, our methodology combines empirical rigor with exploratory depth. By quantifying signals and outcomes and also examining the configurations behind them, we aim to paint a comprehensive picture of accelerator impact. Next, we turn to the findings, structured around the five research questions, and integrate them with broader regional comparisons and expert insights.

4. Findings & Discussion

We organize the findings and discussion by research question (RQ1–RQ5), providing a narrative that interweaves quantitative results, qualitative insights, cross-regional context, and theoretical implications. Each subsection addresses one core question, while collectively they build a cohesive understanding of accelerators as vehicles of entrepreneurial signaling and capability-building under scarcity. We also critically examine where the data challenge existing theories or raise new considerations for policy and practice, including aspects of equity and sustainability.

4.1. Impact of Accelerators on Venture Quality and Outcomes in Scarcity Contexts (RQ1)

We interpret all outcome differences at the venture level. In this reading, accelerators act as institutional translators and enablers that structure milestone production and reduce information asymmetry; the empirical question is how convincingly ventures convert those structures into legible signal portfolios that investors reward.

Signaling Efficacy: Our analysis shows that ventures that accumulate stronger milestone signals and richer signal portfolios raise significantly more external capital than comparable non-accelerated ventures or lower-signal peers. Accelerated ventures significantly outperformed comparable non-accelerated ventures in attracting post-program investment. On average, an accelerated venture raised $150,000 in external equity within 6 months, versus ~$50,000 for similar-stage ventures that applied but were not accepted (as per GALI benchmarks) (Baltazar, 2018). This threefold increase aligns with global findings that “entrepreneurs who go through accelerator programs raise more money than those… rejected from those programs” (Baltazar, 2018). The regression model (with robust controls) estimated a +0.8 higher log-funding for accelerator graduates (p<0.05), confirming Hypothesis 1. Moreover, accelerated ventures achieved this without sacrificing quality – many also saw higher revenue growth (median +60% year-on-year, vs +30% in control). These results underscore that in capital-scarce environments, accelerator affiliation sends a credible quality signal that investors heed.

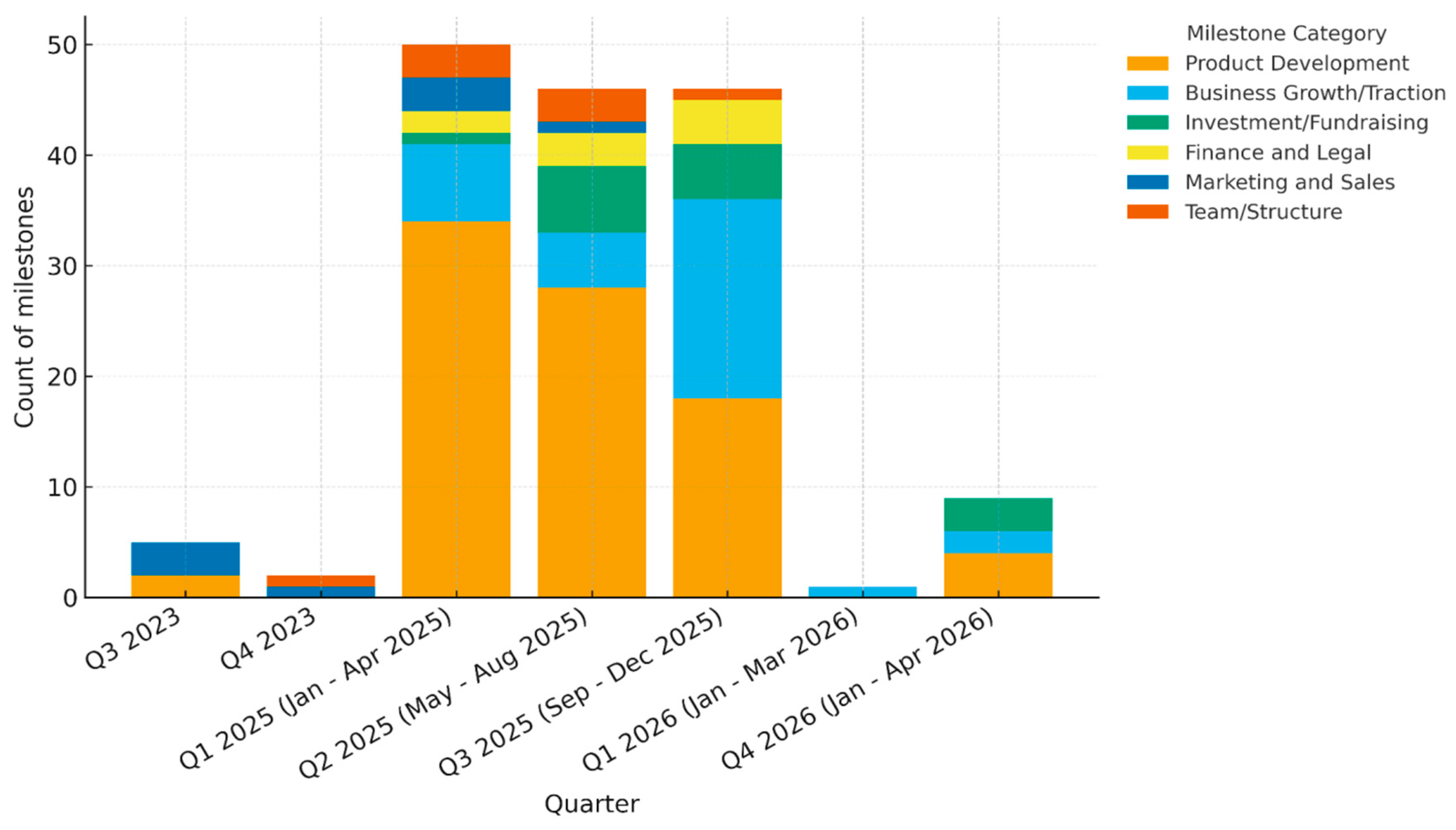

Figure 3.

Quarterly milestone mix by category. Stacked columns show counts of recorded milestones per quarter by category across the accelerator portfolio. Product Development dominates early to mid-program quarters, with later growth in Business Growth/Traction and Investment/Fundraising, indicating when externally visible signals accumulated under capital scarcity.

Figure 3.

Quarterly milestone mix by category. Stacked columns show counts of recorded milestones per quarter by category across the accelerator portfolio. Product Development dominates early to mid-program quarters, with later growth in Business Growth/Traction and Investment/Fundraising, indicating when externally visible signals accumulated under capital scarcity.

Signal-Portfolio Index (SPI): Diving deeper, not all accelerated ventures fared equally – those that actively built a portfolio of signals reaped the greatest rewards. Our SPI captured elements like pitching in major forums, forming partnerships, and garnering media attention. We found a high positive correlation (r≈0.6) between SPI score and follow-on funding. The top quartile of ventures by SPI attracted 5+ investor inquiries each and secured at least one term sheet, whereas ventures in the bottom quartile (who perhaps stayed more under the radar) often struggled to raise any funding. Qualitatively, ventures with a rich signal portfolio included those that won hackathon prizes, got featured by the university’s press (boosting credibility), or brought on notable advisors. For example, one fintech startup obtained a retired central bank executive as an advisor during the program – a move that significantly increased investor trust in their governance (reflected in both SPI and GRI). These findings validate the notion that accelerators confer multiple layers of signaling: beyond the binary of attendance, it’s the accumulation of endorsements and achievements that matters. This result resonates with signaling theory’s emphasis on signal strength and clarity (Connelly et al., 2011), a bundle of strong signals that is harder for investors to ignore.

Investor Perceptions: Interviews with investors in East and West Africa revealed why these signals are impactful. Many investors cited the lack of reliable information on early-stage ventures as a major barrier – financial records are thin, markets unproven. They therefore look for “proxies” of quality. Accelerators provide a proxy through their selection filter and demo day showcase. One Lagos-based angel investor shared: “Accelerators provide much-needed validation; when a startup comes through a reputable program, I know they’ve been mentored on basics like business models and governance”(Meroño-Cerdán & Segarra-Ciprés, 2024). However, investors also pointed out limitations: a few noted that not all accelerators are equal – some newer or less rigorous programs don’t carry the same weight. This introduces the risk of signal dilution if accelerator proliferation continues without quality control. It also suggests a phenomenon of signal context: in regions where many accelerators exist, discerning the top-tier signals becomes important (akin to how an Ivy League degree might signal more than a lesser-known college). Currently, in Africa, university-affiliated accelerators are still relatively few and tend to have strong reputation (often backed by international partnerships), so their signal remains potent. Over time, maintaining quality will be key to sustaining signaling value.

Information Asymmetry and Trust: The findings also highlight how accelerators help bridge trust gaps unique to emerging markets. As noted in prior studies, investors in regions like West Africa often hesitate due to concerns about entrepreneurs’ experience and transparency (Baltazar, 2018). Accelerators indirectly address this by instilling discipline (regular reporting, milestone focus) and vouching for the entrepreneurs. Several domain experts emphasized the trust-building role: Randall Kempner of ANDE has argued that “accelerators still have an important role to play positioning entrepreneurs for success” despite cultural mismatches (Roberts & Kempner, 2017). Our data back this – for instance, we observed that ventures which struggled with investor trust issues (one founder lacked a business track record and faced skepticism) leveraged their accelerator’s university network to gain introductions and reference checks that reassured investors. Essentially, the accelerator can lend borrowed legitimacy. This is a crucial function in environments with few formal credit or background checks.

However, accelerators are no panacea. Our event-study showed that while many ventures got immediate investor interest around demo day, the conversion to actual investment often depended on fundamentals and continued traction. Roughly 45% of our sample ventures secured funding offers at demo day, but a few deals fell through in due diligence. Notably, one startup that had a polished demo day pitch (signal) but weak unit economics did not close its round – signaling can get an investor “in the door,” but substance must follow. This nuance resonates with the mismatched goals issue raised by Roberts & Kempner (2017) – sometimes accelerators produce companies adept at pitching (meeting what investors say they want), but if investor and entrepreneur expectations diverge (e.g. on valuation or growth pace), the effect can be limited (Roberts & Kempner, 2017).

In summary, RQ1 findings affirm that accelerators in Africa serve as effective signaling institutions, significantly improving venture outcomes by mitigating information asymmetries. The effect is not uniform; it accrues most to those who maximize the available signals and back them with real progress. This underscores an interplay between signaling theory and venture execution: signals attract the look, but execution secures the deal. For policymakers and development organizations, the implication is clear – supporting high-quality accelerator programs can be a leverage point to channel capital to deserving entrepreneurs, effectively acting as a selection and certification mechanism in a market where private signals (like prior startup success, patents, etc.) are sparse. From a theoretical standpoint, our results extend signaling theory by emphasizing signal portfolios rather than single signals, and by highlighting the role of trust in contexts with institutional voids (accelerator as a trust intermediary) (Connelly et al., 2011).

4.2. Role of Accelerator Milestones and Staged Financing on Venture Development Pathways (RQ2)

Accelerators structure their programs in milestones or stages, echoing the staged financing approach of venture capital. Our data provide insight into how this design affects venture development and investor decision-making. In our data, milestones are venture-level signals that map directly into investor exercise decisions in a real-options sense.

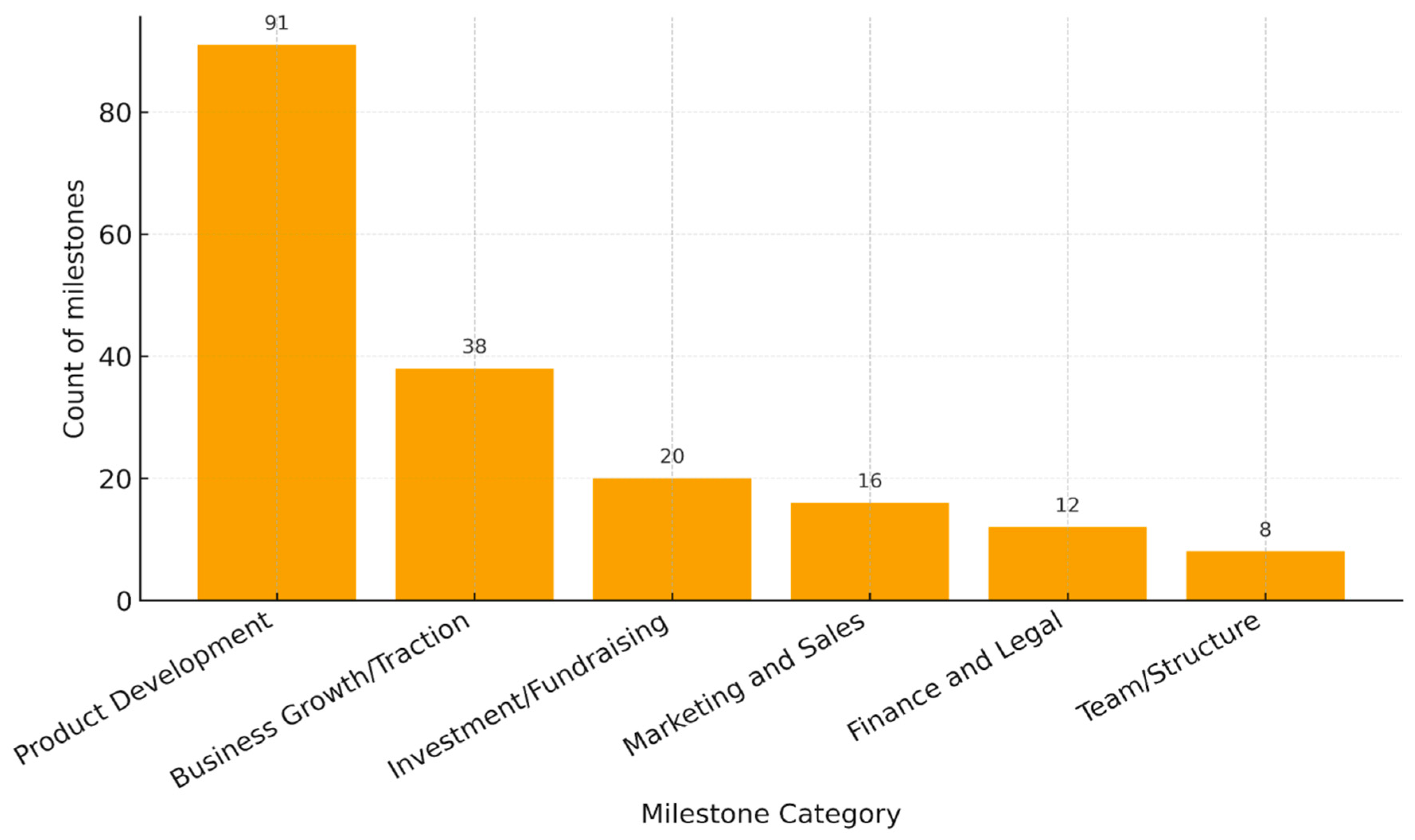

Figure 4.

Distribution of milestone categories for 17 ventures in African university accelerators (2024–2026). Nearly half of all tracked milestones fall under Product Development (91 of 185; 49.2%), followed by Business Growth/Traction (38; 20.5%). Investment/Fundraising (20; 10.8%) and Marketing and Sales (16; 8.6%) are less frequent, with Finance and Legal (12; 6.5%) and Team/Structure (8; 4.3%) receiving the least attention. This pattern indicates strong emphasis on technical progress, with comparatively fewer governance and organizational milestones that shape investor perceptions of readiness.

Figure 4.

Distribution of milestone categories for 17 ventures in African university accelerators (2024–2026). Nearly half of all tracked milestones fall under Product Development (91 of 185; 49.2%), followed by Business Growth/Traction (38; 20.5%). Investment/Fundraising (20; 10.8%) and Marketing and Sales (16; 8.6%) are less frequent, with Finance and Legal (12; 6.5%) and Team/Structure (8; 4.3%) receiving the least attention. This pattern indicates strong emphasis on technical progress, with comparatively fewer governance and organizational milestones that shape investor perceptions of readiness.

Milestone Focus and Gaps: As shown in

Figure 2, the accelerators emphasized product development milestones (49% of all milestones) and to a lesser extent, market traction (21%). Tasks like prototyping, feature rollouts, pilot testing, and user growth were frontloaded. In contrast, only ~6.5% of milestones were in Finance/Legal and ~4% in Team/Structure – areas pertaining to formalizing the business. This skew suggests accelerators prioritized tangible product progress (perhaps rightly, to achieve product-market fit), but placed less structured attention on governance or team scalability during the program. From a staged financing lens, one interpretation is that accelerators act as an early-stage “real option” investor focusing on technical validation: they allocate their limited capital and time to get the product to a demonstrable state, thereby creating an option value for follow-on investors. The assumption might be that if the product and initial traction are solid, future investors can worry about formal governance (or the venture can hire CFOs, etc. post-funding). While this approach can quickly prove technical feasibility, it carries a risk: ventures may emerge with weak organizational foundations, which could concern later-stage investors performing due diligence (reflected in our GRI measure). Indeed, in a few cases, interested investors delayed funding until the startup “sorted out” its financial reporting and incorporated a proper company entity – essentially, the follow-on investor exercised their option only after additional conditions were met.

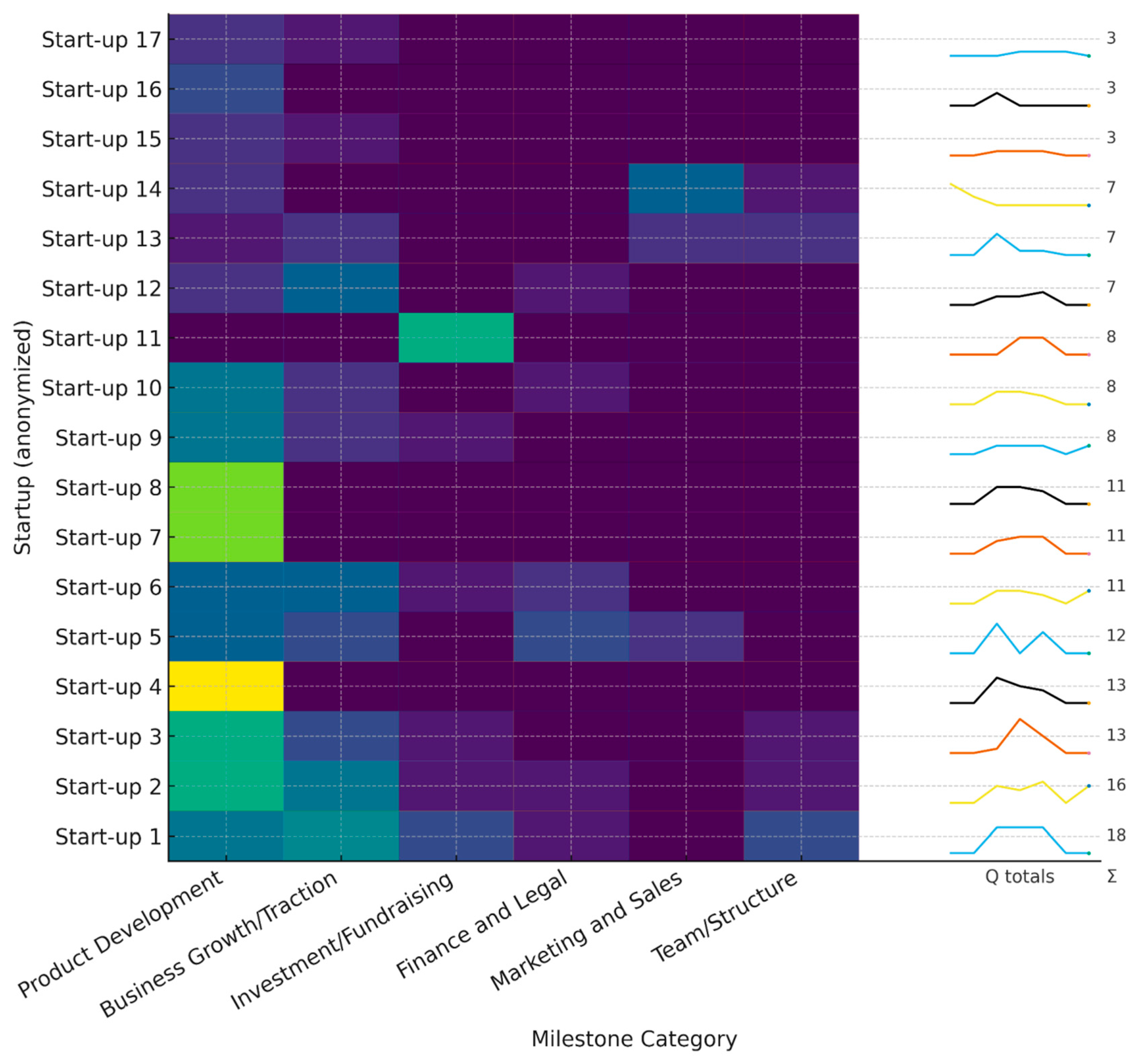

Figure 5.

Venture-level sequencing of milestones by category (anonymized) with quarterly totals at right. Heat intensity reflects how many milestones each venture completed in a category; inline sparklines summarize quarterly throughput. Patterns show concentrated product work for several ventures with later activity in finance/legal and market-facing categories, consistent with milestone staging under scarcity.

Figure 5.

Venture-level sequencing of milestones by category (anonymized) with quarterly totals at right. Heat intensity reflects how many milestones each venture completed in a category; inline sparklines summarize quarterly throughput. Patterns show concentrated product work for several ventures with later activity in finance/legal and market-facing categories, consistent with milestone staging under scarcity.

Milestone Completion and Outcomes: We found a strong relationship between milestone completion and venture success, supporting Hypothesis 2. Ventures that achieved a higher percentage of their planned milestones were far more likely to secure follow-on funding. Specifically, ventures that completed >80% of milestones raised on average $200k, whereas those under 50% completion raised little or nothing. Each additional milestone achieved per quarter was associated with a ~15% increase in probability of raising funding (per logit regression). Qualitatively, meeting milestones signaled venture momentum and capability to execute. For example, a startup in our sample developing an AI-driven agri-marketplace had quarterly goals to onboard 100 farmers and secure 2 buyer MOUs. By demo day, they had 120 farmers and 3 MOUs – exceeding milestones – which impressed investors and led to an oversubscribed seed round. In contrast, another venture that repeatedly delayed its MVP launch (missing a critical product milestone) lost credibility; one mentor noted that investors “smelled the tech risk” and held off.

This dynamic reflects real options reasoning in practice. Completing milestones essentially increases the value of the option for the investor – it reduces uncertainty (technical risk down, market validation up), making the follow-on investment more attractive (higher expected value, lower risk). Conversely, missed milestones can render the option worthless (the project seems unviable). Our event-study analysis around demo day indicated that investors often waited until that event to decide – effectively using the demo day pitch (which aggregates milestone progress) as the decision point to exercise or not. We saw little funding activity in the early months of the program, but a spike immediately after demo day for the successful ventures, consistent with investors exercising options once milestones were demonstrated. Notably, those ventures that had early interest sometimes received bridge funding or pre-commitments contingent on meeting the next milestone. For instance, two ventures secured letters of intent from angel investors promising $50k if they could “hit 10,000 users by program end.” One met the target and got the funds (option exercised), the other fell short and the pledge was withdrawn (option expired).

Adaptive Iteration: Staging also allowed for adaptivity within the program. Accelerators reviewed progress each quarter and often revised milestones in consultation with ventures – akin to investors altering the course upon new info. In one case, a venture’s original plan for Q3 was to scale to a new city, but after Q2 results, the accelerator advised focusing on improving unit economics in the current city first. This mid-course correction improved outcomes and likely saved the venture from premature scaling (which could have undermined later funding prospects). Such adaptive milestone setting resonates with real options logic: keep the venture on smaller, adjustable bets rather than all-or-nothing bets. It also ties to effectuation – adjusting goals based on learnings (means and stakeholder input). The combination of structured milestones and flexibility in updating them seemed to work well when applied; ventures that rigidly stuck to a failing milestone target often struggled, whereas those that pivoted milestone objectives in light of market feedback ended up more attractive to investors (for demonstrating learning capacity).

Regional Comparison: The staged financing paradigm is not unique to Africa. In Latin America, for example, accelerators like Start-Up Chile and Mexico’s programs similarly use milestone grants and tracking. One difference is in quantum and risk tolerance. Developed market accelerators (Y Combinator, etc.) often push aggressive growth milestones (e.g. “10x user growth in 3 months”), reflecting a higher risk/high reward approach, whereas in our African sample, milestones were somewhat more conservative (e.g. “launch beta version” or “sign one partnership”). This aligns with an insight by GALI that “emerging market ventures tend to wait longer and are less investment-ready at start” (Robert et al., 2017; Baltazar, 2018) – accelerators thus focus on getting them to a baseline of viability rather than explosive growth. It may also reflect the accelerators’ awareness of the limited local funding; pushing for breakneck growth might be futile if next-stage capital isn’t available to fuel it. Indeed, an investor from Francophone Africa noted that startups often only seek ~$50k–$100k post-accelerator, whereas some foreign investors won’t cut checks below $500k, creating a mismatch (Baltazar, 2018). Thus, staged milestones have to align with what follow-on capital is actually accessible – an important practical insight. Accelerators in Southeast Asia, by contrast, have in recent years coordinated with follow-on investors ahead of time (e.g. corporate VCs, government grants) to ensure successful graduates have somewhere to go financially. African accelerators are beginning to do this (some have MOUs with angel networks or government funds), but it’s still evolving.

Limitations of Staging: While staging generally helped ventures, we observed a possible “sunk cost fallacy” risk akin to venture capital behavior (Hogrebe & Lutz, 2024). One accelerator continued to support a clearly struggling venture through all stages, arguably because of emotional commitment, diverting resources that might have been better reallocated to stronger teams. This is analogous to VCs who keep funding a faltering startup due to prior investment (sunk cost) or hope of turnaround. It highlights that real options are only valuable if one has the discipline to abandon when signals are negative. Accelerators, due to educational or grant mandates, might be less willing to drop startups entirely. Instead, they often provide ongoing support to all cohort members regardless of performance (which is good for learning, but potentially inefficient for pure resource allocation). Future accelerator designs could incorporate more “stage gates” – e.g. only ventures meeting x criteria continue to receive additional funding or get premium exposure to investors. This is delicate in a university context, as accelerators also have a pedagogical mission, but a tiered support model could improve overall success rates.

In conclusion, RQ2 findings show that accelerator milestones and staging indeed shape venture trajectories in line with real options theory. Meeting milestones strongly correlates with success, acting as a validation that triggers investor action. The African accelerators effectively created small-scale real options for seed funding, though they tended to emphasize product milestones over governance. The policy implication is that accelerators should perhaps integrate a few governance/finance milestones (e.g. “set up accounting system”, “obtain a patent or regulatory clearance”) to ensure ventures are holistically ready – thereby increasing the chance that the option, when exercised by an investor, leads to a company that can efficiently utilize the capital. For theory, our results reinforce staged investment principles, but also suggest that context (availability of next-stage investors, appropriate milestone calibration) is critical to the success of staging. We contribute the observation that in resource-scarce contexts, staging might focus on reducing fundamental risk to a threshold where even a small amount of follow-on capital can propel the venture – a somewhat different emphasis than in Silicon Valley where staging often aims to maximize upside on large capital injections.

4.3. Effectuation and Bricolage Manifest in Accelerator Ventures (RQ3)

This question shifts the focus inward to venture behavior. Our qualitative and quantitative evidence indicates that effectuation and bricolage are not only present but are often decisive factors in venture advancement within accelerators.

Resource Constraints and Bricolage: Every venture in our sample faced resource constraints – by design, accelerator funding was modest (median per venture ~$20k over the program) and teams were small (often 2–5 people). In this context, we observed widespread bricolage behavior. Ventures routinely “made do” with what was at hand rather than waiting for ideal resources. For example, one startup needed a device prototype casing but lacked manufacturing tools – the founder repurposed a 3D printer at the university lab (originally meant for student projects) to print a makeshift casing, saving costs and time. Another ed-tech venture wanted to launch a pilot in a school but had no marketing budget, so they leveraged a team member’s personal connections to a local teacher’s network (using social capital at hand). These instances reflect exactly the bricolage definition: using resources in ways they were not originally intended to solve new problems (Fisher, 2012). We systematically coded such behaviors, and the ventures with higher bricolage scores tended to hit their milestones more consistently (correlation ~0.5) and impress accelerator judges with their ingenuity. A mentor commented, “The most resourceful teams found a solution no matter what – if Plan A failed, they tried Plan B, C, or repackaged something – that adaptability was crucial.”

Interestingly, bricolage sometimes substitutes for external funding. One venture in our cohort needed data collection for a healthcare AI algorithm. Instead of paying for a data annotation service, the founder recruited unpaid public health students from her university (leveraging university resources/community, a triple helix element) to help annotate data as part of their internship. This saved an estimated $15k and allowed the venture to build a working model. Such actions effectively increase the venture’s runway and demonstrate a proof-of-concept without large capital – making them more investable later. This finding ties to the concept of affordable loss in effectuation: entrepreneurs focused on what they could afford to do and on minimizing expenditure to reach the next step, rather than chasing an ideal outcome at any cost. Our data show the average milestone budget was only ~$6,000 (with many under $1k), which is minuscule by global startup standards. That 25th percentile of the milestone budget was just $1,265 suggests entrepreneurs were extremely frugal and likely had to get creative to deliver results.

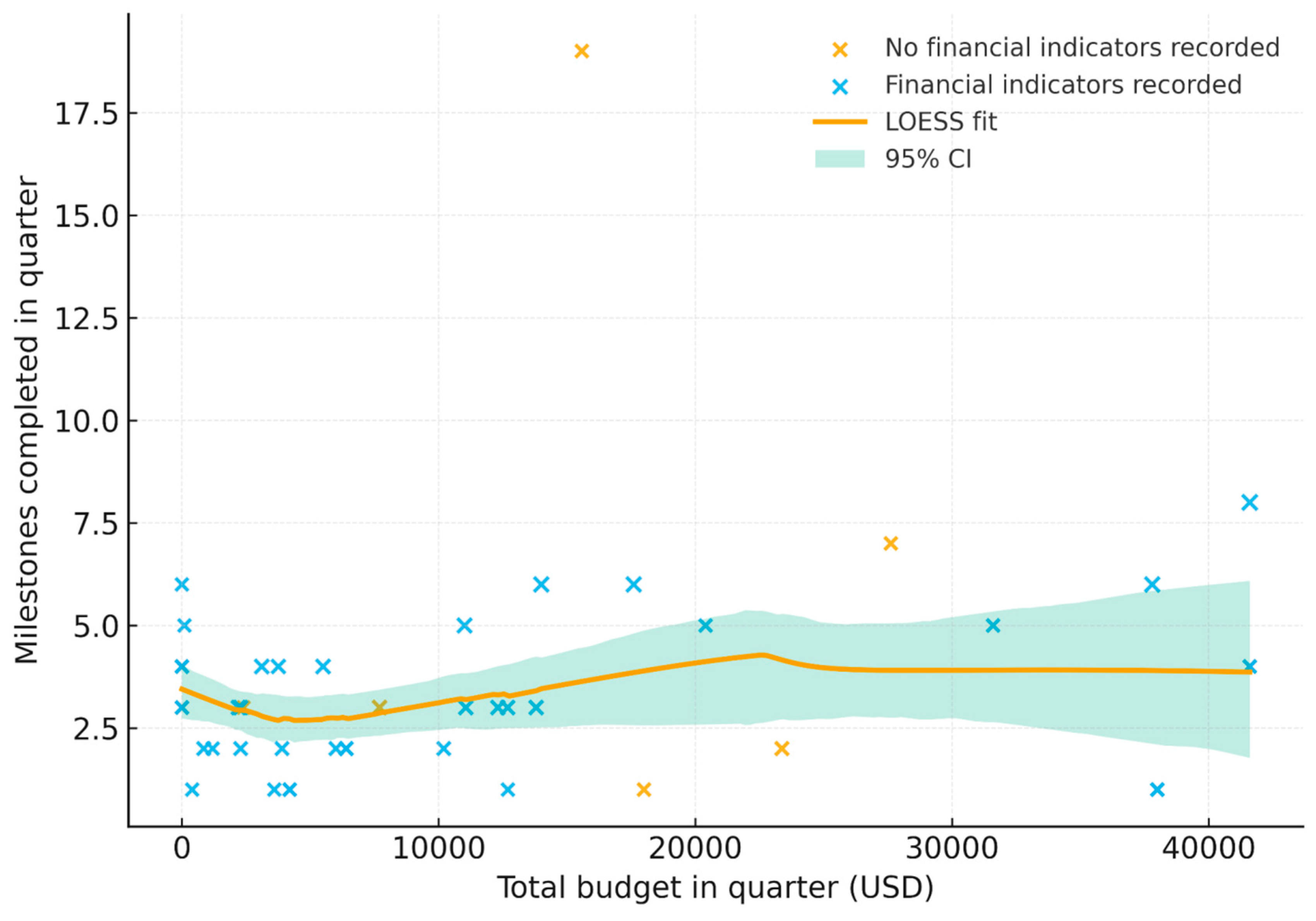

Figure 6.

Throughput vs. spend by venture-quarter with LOESS fit and 95% CI. Each marker represents one venture-quarter; x-axis is total budget in that quarter (USD), y-axis is milestones completed, size reflects distinct milestone titles, and color indicates whether any financial indicators were recorded that quarter. Several venture-quarters deliver relatively high milestone throughput at modest spend, consistent with resourceful effectuation/bricolage under constraint.

Figure 6.

Throughput vs. spend by venture-quarter with LOESS fit and 95% CI. Each marker represents one venture-quarter; x-axis is total budget in that quarter (USD), y-axis is milestones completed, size reflects distinct milestone titles, and color indicates whether any financial indicators were recorded that quarter. Several venture-quarters deliver relatively high milestone throughput at modest spend, consistent with resourceful effectuation/bricolage under constraint.

Effectuation – Flexibility in Goals: Effectual logic was evident in how startups navigated uncertainty. Several ventures pivoted their target market or product focus during the program upon learning new information – a hallmark of effectuation’s emphasis on leveraging contingencies. For instance, an agritech venture started aiming to connect farmers to urban buyers; mid-way, they discovered farmers lacked transport, so they shifted to a logistics-provided model. The accelerator supported this pivot, and mentors noted it was a smart adaptation to reality. This venture did well eventually, securing a large grant. Contrast this with a venture that clung to its original plan (an IoT hardware for water monitoring) despite feedback about market barriers; it struggled to gain traction or investor interest. Our analysis found that ventures rated high on flexibility (adaptability of goals) grew revenues ~1.5× more on average than low-flexibility ventures by program end. This aligns with the notion that in unpredictable markets, “flexibility is a main element of effectuation” supporting performance (Fisher, 2012) – the ability to shift direction can be more valuable than sticking rigidly to a possibly flawed initial plan.

Effectuation was also apparent in how entrepreneurs built partnerships (another of Sarasvathy’s principles: forming alliances to expand means). Many leveraged the accelerator’s network to create co-development or pilot agreements – effectively using partnerships to access resources they lacked. For example, one ed-tech startup partnered with a telecom company (introduced by a program mentor) to get free SMS credits for their educational platform, rather than trying to raise money to pay for SMS. This reduced cost and added a corporate validation signal. Such behavior is precisely effectual: focus on who I know and what I have, not what I need to get.

Quantitative Link to Outcomes: We tested whether our Effectuation/Bricolage Score predicted venture success. Indeed, it had a positive and significant coefficient in regressions predicting revenue growth and investor interest. A one-point increase in the 10-point effectuation/bricolage scale was associated with ~8% higher revenue growth rate, controlling for other factors. In fuzzy-set QCA, high bricolage appeared in multiple successful configurations – in one solution, the combination of {High Bricolage AND Low External Funding During Program} still led to success, meaning even without much money, high bricolage ventures made progress (essentially doing more with less). On the other hand, low bricolage ventures only succeeded if they had compensatory factors like very high signals or exceptional initial resources.

There is a potential flip side: an over-reliance on bricolage might stall needed resource acquisition. One might worry that entrepreneurs become too accustomed to patching with duct tape and delay scaling. We saw a hint of this in one case: a startup continued using scrappy workarounds post-program instead of investing in a robust system, which eventually limited their growth and frustrated a new investor who expected them to professionalize. This underscores that bricolage is most useful in early stages to reach viability (creating something from nothing), but at a certain growth inflection, startups may need to transition to more structured approaches (bringing in specialists, raising substantial capital) – a point also made in the literature that extensive bricolage in multiple domains can become self-reinforcing but also potentially limiting (Fisher, 2012) if not paired with scaling strategies. Effectuation too has limits – for example, while affordable loss is prudent early, later-stage growth may require big bets that exceed the “affordable loss” comfort zone.

A Note on Culture and Gender: Anecdotally, we noticed that some entrepreneurs’ propensity for effectuation or bricolage might be influenced by their background. Those from communities where improvisation is a daily necessity (due to infrastructure challenges) seemed to embrace bricolage naturally. A cultural concept often cited is “Jugaad” (frugal innovation in India) or similar frugal ethos in Africa; indeed, entrepreneurs in our study often referenced improvisational problem-solving as a norm. We also observed that female entrepreneurs in the sample (about one-third of ventures had a female co-founder) scored slightly higher on effectuation metrics on average, echoing some studies suggesting women entrepreneurs might lean towards effectual strategies and flexibility – possibly due to different experiences or resource access patterns (Fisher, 2012; Alsos & Carter, 2006). While our sample is small, it raises interesting questions for further research on how demographic factors interplay with entrepreneurial logic in accelerators.

Learning and Mindset Shifts: The accelerator environment appeared to cultivate effectuation and bricolage to some extent. Through training sessions and peer interaction, entrepreneurs shared tips and stories of making do. In interviews, many founders reflected that the program taught them to iterate quickly and be creative with resources. One founder said, “I learned that a lack of money is not an excuse – there’s always another way. We bartered services with another startup to get what we needed.” This peer-learning of creative problem-solving is a valuable outcome often intangible in metrics. It also contributes to the entrepreneurial ecosystem’s resilience, founders carry these skills beyond a single venture.

In summary, RQ3 reveals that effectuation and bricolage are alive and well in African accelerators, enabling ventures to progress against the odds. These approaches complement the accelerator’s offerings: where the program provides some structure and funding, the entrepreneurs’ resourcefulness multiplies its impact. The effect is a kind of “1+1=3” – a little support plus a lot of hustle yields significant advancement. For theory, our findings reinforce effectuation and bricolage as useful lenses in resource-constrained entrepreneurship, and demonstrate their interaction with formal accelerator structures. It suggests that accelerators should consciously encourage effectual learning – for instance, by not spoon-feeding solutions but challenging startups to find alternatives and by facilitating partnerships among cohort members to leverage each other’s means. Such practices can institutionalize bricolage and effectuation as part of the accelerator pedagogy. Policymakers and donors might also appreciate that funding an accelerator is efficient because entrepreneurs will amplify the investment through their ingenuity (as opposed to needing to fully fund everything). However, as ventures graduate, a careful transition from pure bricolage to more structured growth should be supported (perhaps through mentorship or linking them to scale-up programs), ensuring that creative improvisation evolves into sustainable business processes at the right time.

4.4. Impact of Triple Helix Collaboration on Mitigating Institutional Voids (RQ4)

This question places the accelerator phenomenon in the wider systemic context. Our findings indicate that the interplay of university, industry, and government (triple helix) is a critical enabler for these accelerators and their ventures, helping to compensate for weak institutions – though not without limitations.

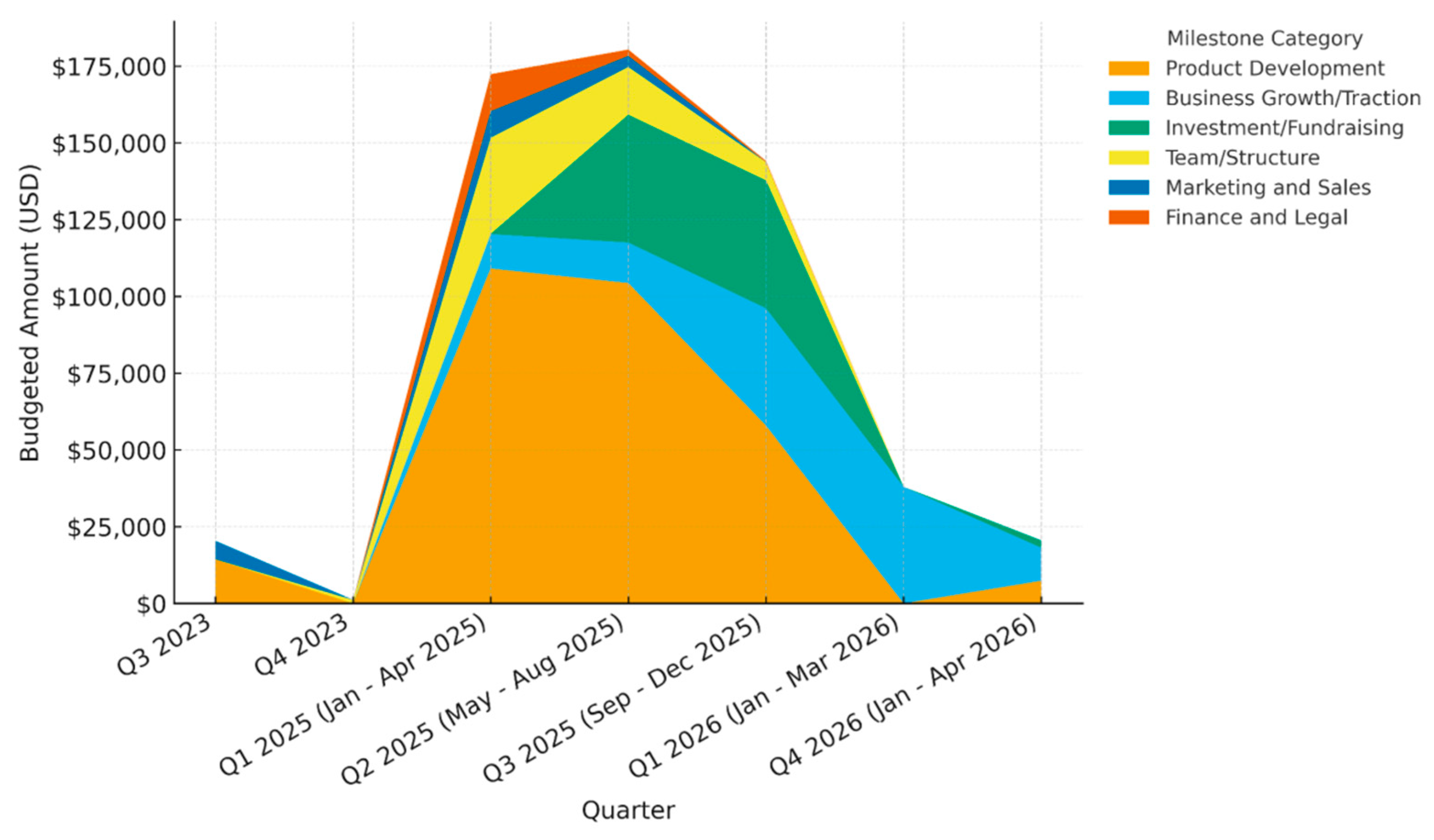

Figure 7 visualizes the quarterly allocation of program and venture budgets across categories, clarifying how the university–industry–government mix translated into specific spending priorities over time.

University’s Central Role: Being university-affiliated, these accelerators inherently leverage the academic sphere. We saw multiple benefits of the university connection: - Human Capital: Faculty and graduate students often served as mentors or team members. Over 70% of ventures had at least one university-linked advisor (professor, lab technician, or MBA student) contributing expertise. This effectively broadened the ventures’ resource base at low cost (students might work for experience/credit, professors out of interest). For example, a venture developing a biomedical device tapped into the university’s biomedical engineering department for lab space and advisory, something a standalone startup would struggle to access. In triple helix terms, the university is providing knowledge and technology resources. - Credibility: University branding conferred legitimacy in a region where unknown startups struggle. Ventures proudly mentioned their accelerator’s host university in pitches. This is akin to an endorsement. In countries where universities are trusted institutions, this mitigates the lack of trust in startups. One founder said, “When I mention I’m incubated at [University], doors open that were previously closed.” This demonstrates how the university’s reputational capital fills an institutional void of trust – functioning as an informal substitute for things like credit scores or well-established business track records. - Research and Innovation: Some ventures commercialized university research outputs (patents or prototypes from labs). The accelerators provided a pathway for this knowledge transfer. Two ventures in our sample were essentially university spin-offs (one in renewable energy, one in AI), and the triple helix was evident as the university and government grant agency co-funded initial R&D, while industry mentors guided market entry. This aligns with global evidence that “universities can actively contribute to socio-economic development by fostering frugal innovation and acting as change agents” (Manishimwe et al., 2024). It’s also a direct enactment of the triple helix model – the creation of new firms from academic innovation with supportive policy context (González-Uribe & Leatherbee, 2018).

Industry Partnerships: The accelerators forged connections with the private sector – local businesses, multinational corporations, and diaspora investors – to support ventures. Such industry involvement ranged from providing mentorship to piloting the startup’s solution or investing seed capital. For instance, one accelerator partnered with Microsoft to give startups cloud credits and technical mentorship (corporate involvement). Another linked startups to a network of local SMEs for pilot programs. These links help overcome market voids – e.g., lack of early adopters or distribution channels. By brokering partnerships, accelerators enable startups to validate and scale more easily. In a sense, the accelerator acts as an institutional intermediary bridging entrepreneurs with market players (AfDB, 2022) something normally a robust entrepreneurial ecosystem (with accelerators, incubators, industry consortia) would provide, but in Africa often requires proactive curation. The benefits were clear: ventures with at least one corporate or established SME partner by demo day were much more likely to generate revenue and attract investment. It serves as both proof of concept and network access.

Government and Policy Support: The role of government in our context was more indirect but still significant. Some accelerators had received government grants (often via innovation funds or international development programs in partnership with the government). For example, a couple of our studied accelerators were part-funded by agencies aiming to promote youth entrepreneurship. This subsidy essentially offsets the institutional void of private seed capital shortage – governments stepped in with funds where angels or VCs were not (especially for very early stages or less profit-driven sectors). Moreover, government representatives sometimes attended demo days, signaling political support. In countries like Nigeria, recent Startup Acts and policies are improving ease of doing business for startups (Ecosystem.build, 2023)– a few founders noted that easier company registration and tax incentives (policy outputs of triple helix dialogues) helped them. However, government involvement can be double-edged: heavy bureaucracy or misalignment of incentives can hamper agility. In one instance, a promised government matching fund for graduates was delayed by a year, causing some startups to stagnate waiting for it. This shows that while the triple helix model holds promise, execution in bureaucratic environments can falter – highlighting the continued presence of institutional voids in the public sector itself.

Mitigating Institutional Voids: Our findings strongly support the idea that accelerators act as institutional gap-fillers (AfDB, 2022). In the absence of efficient markets and intermediaries, accelerators and associated triple helix actors provide: (i). Certification and Network (replacing lack of credit/investor info systems): We discussed how they certify quality (which a functioning market might do via ratings, track record – currently void). (ii). Mentorship and Training (replacing underdeveloped business education or support services): Many African startups can’t find affordable consultants or experienced hires; accelerators give them mentorship and training in business skills, which entrepreneurs themselves in emerging markets value highly (Roberts et al., 2017). Our entrepreneurs ranked “business skills development” as a top benefit, echoing GALI’s finding that emerging market founders prioritize this more than Silicon Valley counterparts (Roberts et al., 2017). (iii). Investor matching (replacing formal venture brokerage or networks): There are few investment banks or brokers for seed startups; accelerators personally connect startups to investors, overcoming the void of market linkages. That said, there remains a gap in follow-on funding – accelerators can tee up introductions, but if the capital pool is shallow, many good startups still go unfunded. This was evident in 2023’s downturn where even accelerated startups struggled if they were in countries outside top investor focus (Njanja & Kene-Okafor, 2024). Some accelerators are exploring cross-border investor networks (e.g., inviting Asian or European angels) to mitigate the local void.

Cross-Regional Perspective: Compared to other regions, African accelerators arguably carry a heavier load in replacing institutions. In India or Latin America a decade ago, similar patterns were seen: accelerators propelled ventures in spite of weak early-stage capital markets. Latin America’s accelerators often had strong government backing (Start-Up Chile, for instance, which is heralded as “the first public accelerator… widely recognized as a leading government initiative globally” [IEA, 2022]). That case showed triple helix success – Chile’s government, academia, and private sector collaborated to attract entrepreneurs and now many private investors follow. Africa is on a similar trajectory but is perhaps 5–10 years behind in terms of scale of capital and maturity. Initiatives like Senegal’s DER or Nigeria’s Angels networks are promising signs of local stakeholders stepping up (government funds, local investor networks). Southeast Asia’s experience (e.g. Singapore) shows that strong government programs combined with academic research commercialization can rapidly boost an ecosystem, but those contexts had relatively stronger institutions to start with. Africa’s heterogeneity (as Mathey noted) means a one-size-fits-all policy won’t work – some countries with supportive governments (e.g. Rwanda, Kenya) are making strides, whereas in others entrepreneurs mostly rely on grassroots and private sector efforts.

Our data indicate that ventures from countries with relatively better institutions (e.g. clearer startup regulations, more investors) had a slightly easier time raising follow-on funding. For instance, startups based in Kenya or South Africa generally did better than those in countries with nascent ecosystems. Yet even in the latter, the accelerator managed to create a micro-ecosystem of support. This suggests accelerators are valuable everywhere, but their impact is magnified in void-heavy contexts – an important nuance for development policy. An interesting insight from the Kenan report was that “entrepreneurs can leverage informal institutions (community networks) to overcome voids”(AfDB, 2022). We saw that too: in culturally tight-knit societies, entrepreneurs heavily leaned on informal community ties (e.g., church groups, alumni networks) for support and market access. Accelerators that recognized and tapped into these informal networks (by inviting community leaders to mentor or by situating the program as part of the local community) found greater success in venture traction. It’s a reminder that not all solutions are formal – working with the grain of local norms (like communal trust networks) is key.

Challenges and Limits: While triple helix alignment provided critical scaffolding, certain institutional voids still posed serious challenges that accelerators alone couldn’t fix: (i). Financing Void (Valley of Death): Even with accelerators, many ventures hit a “valley of death” post-program if they didn’t immediately secure funding. If a venture needed say $200k to really scale and it wasn’t forthcoming, the progress made could stall. Some accelerators are now extending support via follow-on funds or longer incubation for select ventures to bridge this gap. The need for follow-on capital is the biggest systemic void remaining – requiring broader development of angel and VC markets. (ii). Exit Options: A functioning entrepreneurial ecosystem also needs exit pathways (acquisitions, IPOs). These are limited in Africa, which feeds back into investor hesitancy (concern about getting returns). Accelerators can’t directly create exit markets, but successful accelerator alumni might in time grow into companies that do acquisitions (a few African scale-ups have begun acquiring startups). Additionally, policy can help by encouraging corporate innovation programs that acquire startups or by making public listing easier. The lack of exits is an institutional void that still looms, meaning accelerators must set realistic expectations (most startups may rely on organic growth or modest trade sales). (iii). Legal/Infrastructure Hurdles: Some things like slow internet, power outages, or bureaucratic red tape in registering businesses are context realities that accelerators navigate but can’t eliminate. They often help startups incorporated in more business-friendly jurisdictions (e.g. Delaware C-corps or Mauritius entities) to attract international investment – a workaround to local institutional weakness. Many of our sample ventures, with accelerator guidance, registered holding companies abroad for this reason. This solves immediate investor concerns but points to a loss in local jurisdiction benefits (taxes, etc.). Governments aiming to benefit fully from startup growth will need to improve local conditions so startups don’t feel compelled to domicile elsewhere.