Submitted:

26 September 2025

Posted:

28 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Pulses and Pseudocereals

1.2. Structural and Physicochemical Characteristics of Bioactive Peptides

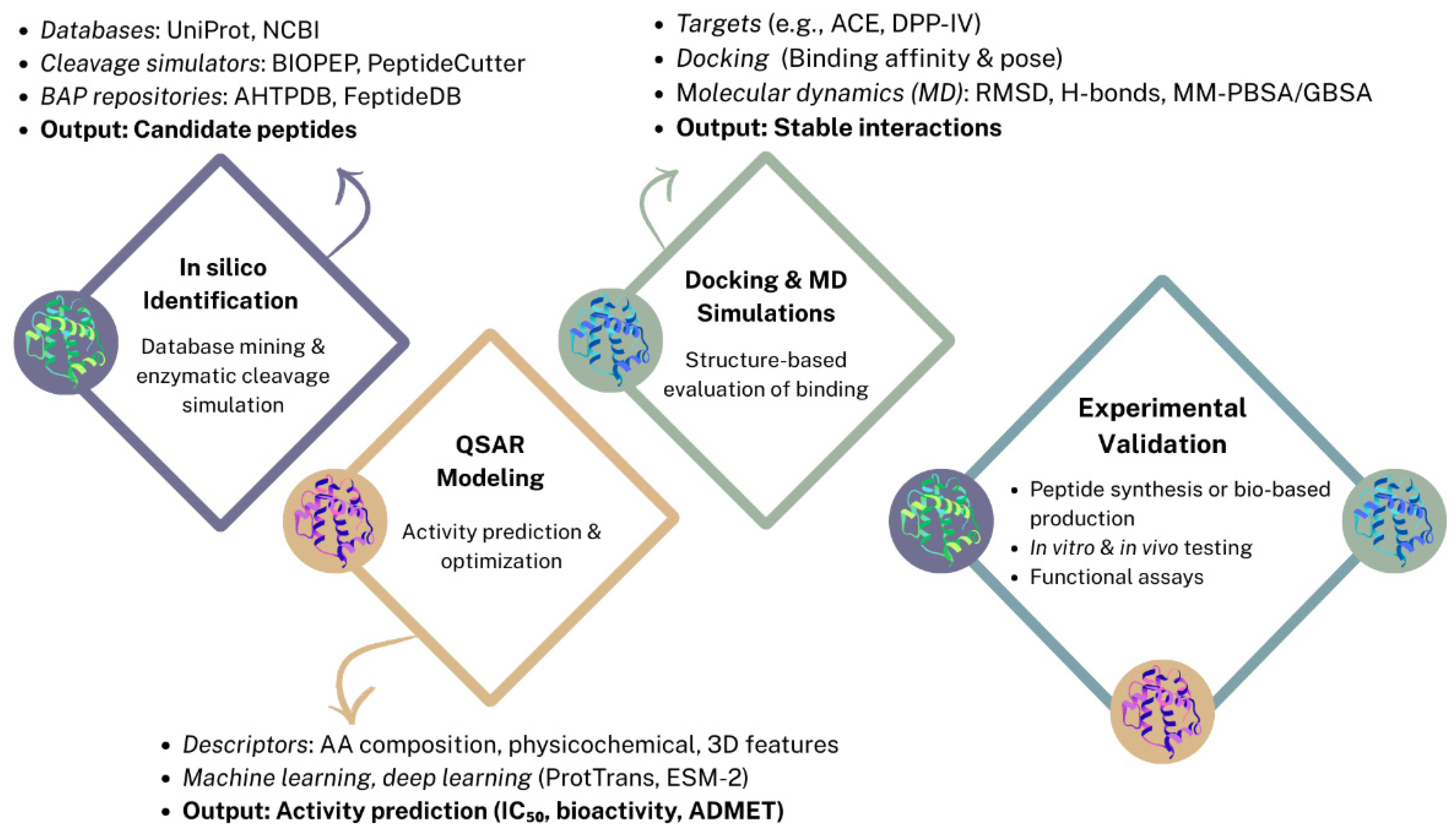

2. Bio-Informatic Approaches for Bioactivity Prediction

2.1. In Silico Identification of BAPs

2.2. Activity Prediction and Peptide Optimization via QSAR Modeling

2.3. Structure-Based Approaches: Molecular Docking and Dynamics

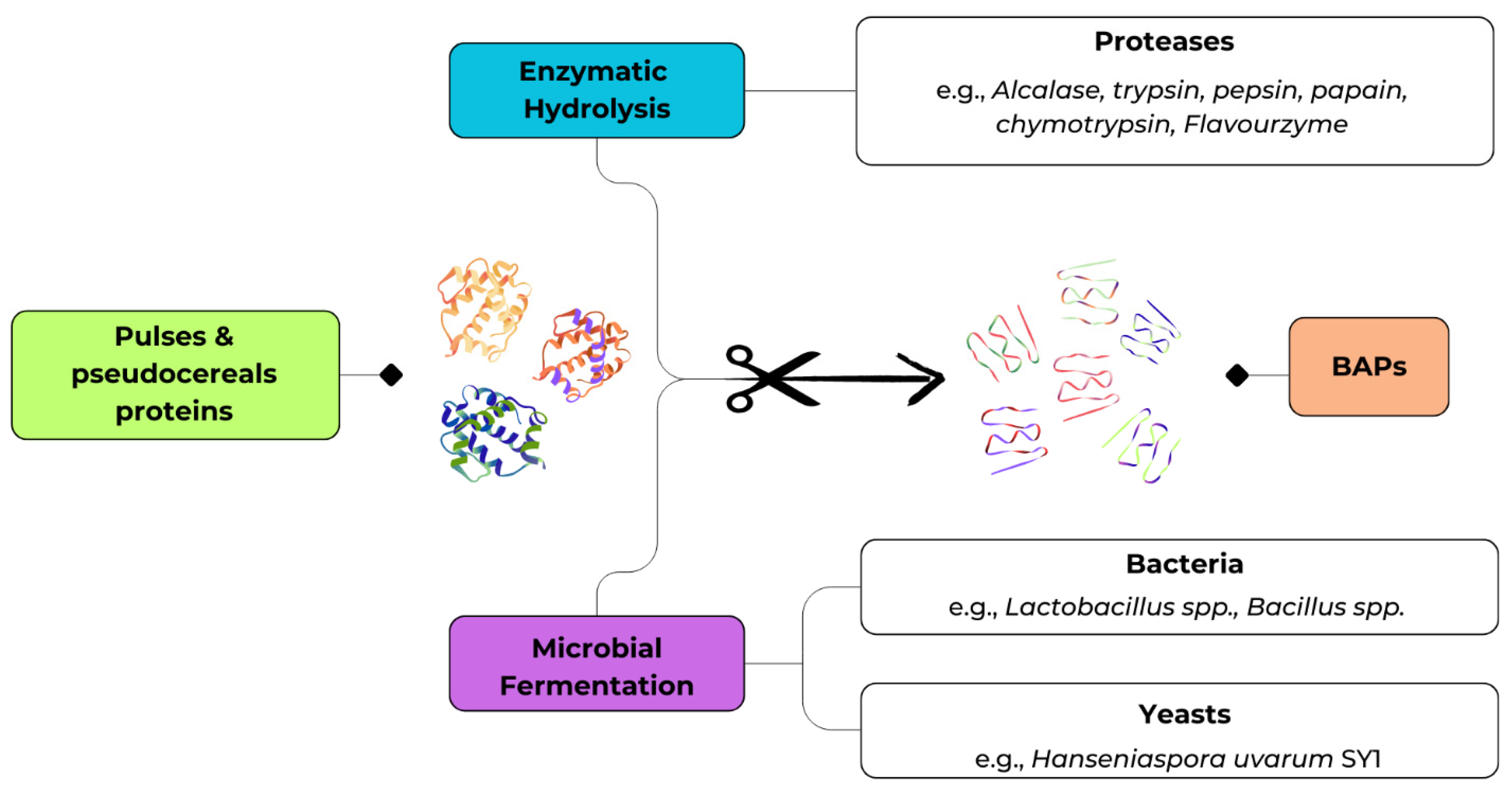

3. Bio-Based Approaches for the Production of BAPs

3.1. Enzymatic Treatments

| Source | BAPs production | Bioactivity | Ref | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatements | Outcome | Type | Dosage | Control | Outcome | |||

| Adzuki bean | Flavourzyme | Adzuki F2 fraction | Antimicrobial | 2 mg/mL | Gentamicin, chloramphenicol | S. typhimurium inhibition (76%) | [47] | |

| Amaranth | Sequential Alcalase + Flavourzyme hydrolysis | Bioactive peptides identified in fraction “45” (e.g., HVQLGHY, SQIDTGS, NWACTL) | Antihypertensive/ Antithrombotic/ Antioxidant | 10 mg/mL amaranth protein hydrolysate | Hippuric acid; thrombin; unhydrolyzed amaranth proteins | Multifunctional: ACE inhibition (IC₅₀ = 0.134–0.808 mg/mL), thrombin inhibition (IC₅₀ = 0.155–0.167 mg/mL), ABTS antioxidant SC₅₀ = 0.992–6.931 mg/mL; | [41] | |

| Chickpea | In silico enzymatic hydrolysis (papain and trypsin) | Prediction of ninety-two peptides with potential DPP-IV and ACE inhibition activity | Antidiabeitc/ Antihypertensive | NA | Omarigliptin (PDB ID: 4PNZ) | His–Phe identified as most potent; in silico predicted DPP-IV and ACE-inhibitory | [33] | |

| Chickpea | Alcalase hydrolysis of albumin and globulin; chromatographic purification | Bioactive sequences identified (e.g., FEI, FIE, FEL and FGKG) | Antioxidant/ Antidiabeitc | 1 mg/mL for hydrolysate; 0.2 mg/mL for peptide fraction; 0.1 mg/mL for α-amylase inhibition assay | Acarbose (1 mmol/L); reaction buffer | High radical scavenging (ABTS and DPPH) ; FEI, FIE FEL had DPP-IV inhibition (IC₅₀ = 4.20 µg/mL) while FGKG showed α-glucosidase and α-amylase inhibition (56% and 54%) | [34] | |

| Cowpea seed | Enzymatic hydrolysis on the protein isolate with Alcalase, 1:200 (E:S), 4h, 55°C, pH 7.8; SEC purification | Cowpea seed protein hydrolysate (< 1 kDa) | Antimicrobial | 25–150 μg/mL | Ciprofloxacin | Broad-spectrum antimicrobial, membrane disruption confirmed | [48] | |

| Faba bean | Simulated digestion with human gastric & duodenal juices (INFOGEST) | 268 BAPs predicted | Anti-inflammatory | 0.1–1000 µM | IL-1β with positive, negative (Fresh serum-free growth medium), and IL-1Rα controls | Selected peptides (e.g., QQGPPPPPPPISL, ATPPPPPPPPMSL) reduced IL-8 up to ~40%, indicating immunomodulatory activity | [38] | |

| Black Jampa bean | Hydrolysis on protein isolate (5%, w/v) using pepsin (90 min, pH 2.5) followed by pancreatin (120 min, pH 7.5) at 1:20 w/w, E:S | Bean protein hydrolysate fractions (phaseolin-rich) | Antioxidant | 100 μg hydrolysates or 50 μg peptide fractions | Blank | 0.7–1.0 kDa peptides had highest Cu²⁺ chelation and moderate Fe²⁺ binding | [49] | |

| Lentil | In vitro simulated GI digestion of lentil flour; ion-exchange and gel filtration fractionation | Fraction 5 contained peptides KLRT, TLHGMV, VNRLM | Antihypertensive | 50 µL of the peptide sample | Hippuryl-His-Leu solutions (1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0 and 10.0 mm) | ACE inhibition, IC₅₀ = 0.0197 mg/mL | [35] | |

| Lentil | Protamex, Savinase, Corolase and Alcalase hydrolysis assisted with high-pressure | The process increased the concentration of peptides under 3 kDa, particularly with pressurization at 300 MPa by all enzymes tested | Antihypertensive/Antioxidant | 0.5 mg/mL (for ACE inhibition assay) | Non-hydrolysed lentil proteins | Highest ACE-inhibitory (69.46%) and antioxidant activity (403.86 μM TE/g) through Savinase treatment at 300 MPa | [36] | |

| Lupin | Enzymatic in silico prediction/ peptide synthesis | LTFPGSAED (Lup1), IC₅₀=228 µM | Antidiabetic | Concentrations ranging from 10 to 1000 μM | Sitagliptin (0.1 μM) | DPP-IV inhibitory; docking confirmed binding; other lupin peptides inactive | [43] | |

| Lupin | Lupin protein isolate (10% w/v) hydrolysed with Alcalase 2.4L (15 min at pH 8, 50 °C, and E/S = 0.3 AU/g protein) | Lupin protein hydrolysate | Antidiabetic | 100 mg/kg (mice), 1 g/day 28 days (human) | Placebo | Inhibited DPP-IV, improved glucose control in mice and humans | [50] | |

| Lupin | Sequentially digested with pancreatin (pH 7.5) and pepsin (pH 2.0), in a ratio 1:20 w/w (E:S) at 37 °C for 1 h | Andean lupin γ-conglutin hydrolysate | Antidiabetic | 5 mg/mL | Untreated cells; metformin (1 mM) and insulin (100 nM) | Inhibited DPP-IV, ↑GLUT4 translocation, ↓gluconeogenesis | [51] | |

| Lupin | Alcalase hydrolysis for 15 min at pH 8, 50 °C, and E/S = 0.3 AU/g protein | Lupin protein hydrolysate | Anti-inflammatory | 0.1–0.5 mg/mL | LPS-treated co-culture, unstimulated cells | Blunted TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 upregulation, IL-1β below baseline | [52] | |

| Lupin | Alcalase hydrolysis on lupin protein isolate for 15 min | Lupin protein hydrolysate | Anti-inflammatory | 100 mg/kg oral prophylactic | EAE mice untreated | Reduced severity, better neurologic function | [53] | |

| Lupin | Alcalase 2.4L (E:S = 0.3 AU/g protein); pH 8.0 at 50°C for 15 min | Lupin protein hydrolysate | Prebiotic | 100 mg/kg/day | HFD mice untreated | Reduced obesity, improved metabolism, restored Akkermansia abundance | [54] | |

| Mung bean | Flavourzyme | Mung bean F4 fraction | Antimicrobial | 2 mg/mL | Gentamicin, chloramphenicol | S. aureus inhibition (71%) | [47] | |

| Pea | Industrial hydrolysis, ultrafiltration | < 3 kDa peptide fraction | Antidiabetic / Antihypertensive | DPP-IV inhibitory assay: in vitro = 0.01 to 2.0 mg/mL; cellular assay = 1.0, 2.5, and 5.0 mg/mL; ACE inhibitory activity: in vitro = 0.08, 0.17, 0.35, 0.7, and 1.0 mg/mL; cellular assay = 0.1 to 5.0 mg/mL | control (C) sample; growth medium and H2O | Inhibited DPP-IV (IC₅₀ = 1.33 mg/mL; < 3 kDa fraction IC₅₀ = 1.0 mg/mL) and ACE (IC₅₀ = 0.61 mg/mL; < 3 kDa fraction IC₅₀ = 0.43 mg/mL); active in Caco-2 cells | [37] | |

| Pea | Simulated digestion with human gastric & duodenal juices (INFOGEST) | 275 BAPs predicted | Anti-inflammatory | 0.1–1000 µM | IL-1β with positive, negative (Fresh serum-free growth medium), and IL-1Rα controls | Selected peptides (e.g., DKPWWPK, NEPWWPK) reduced IL-8 up to ~40%, indicating immunomodulatory activity | [38] | |

| Pea | Pepsin hydrolysis of total protein extract (18 h, E/S = 1:100), ultrafiltration <3 kDa | Peptide mixtures with ACE-inhibitory activity | Antihypertensive | 861 μg/ml | Inhibitor Blank (AIB): enzyme but no inhibitor; Reaction Blank (ARB): highest inhibitor concentration but no enzyme. | ACE inhibition: IC₅₀ = 0.595 mg/mL; maximum inhibition 71% at the highest concentration tested (0.861 mg/mL) | [44] | |

| Quinoa | Papain digestion of quinoa bran globulin powder | Quinoa bran globulin hydrolysate (SAPPP fraction) | Antihypertensive | IC₅₀ = 915 μM | ND | Stable ACE inhibition after digestion, pH fluctuations (2.0–10.0), pasteurization conditions, addition of ions | [55] | |

| Quinoa | Chymotrypsin hydrolysis (QPI, 2 h) | Peptides identified (e.g. QHPHGLGALCAAPPST) | Anti-hypercholesterolemic | 25 – 50 μL of sample | p-nitrophenyl butyrate | Highest inhibition of cholesterol esterase (IC₅₀=0.51 mg/mL) and pancreatic lipase (IC₅₀=0.78 mg/mL | [32] | |

| Quinoa | Simulated GI digestion of protein isolates | Peptide fractions < 5 kDa and > 5 kDa | Antioxidant | ND | Trolox (0.2–1.6 nmol); | Peptides with antioxidant and colon cancer cell viability inhibitory activity identified; hydrolysates showed strong radical-scavenging activity | [39] | |

| Quinoa | Alcalase and trypsin hydrolysis; MW cut-off = 3, 10 kDa | Different molecular weight peptide fractions | Antidiabetic | ND | pNPG substrates | Highest α-glucosidase inhibition (44.8%) obtained with 0.5 h hydrolysis time and 3 kDa ≥ MW. | [40] | |

| Quinoa | High pressure-assisted enzymatic hydrolysis with 0.14 AU of Alcalase/ g protein (1:20 w/v E:S) | Quinoa protein hydrolysate (< 3 kDa) | Antihypertensive | 0.1–0.5 mg/mL | Blank, non-hydrolyzed proteins, conventional hydrolysis | High-pressure hydrolysis improved ACE inhibition | [56] | |

| Quinoa | Simulated gastro-intestinal digestion, only pepsin and pancreatin | Quinoa albumin peptides (lunasin-rich) | Anti-inflammatory | 1 mg/mL | IL-1β-treated cells | Up to 74% reduction in NF-κB activity. In vitro digestion enhanced the effect | [57] | |

| Red quinoa | Hydrolysis with Alcalase 2.4 LFG, 2 h. | Red quinoa protein hydrolysate | Antioxidant/ Antihypertensive |

1000 mg/kg/day (8 weeks) |

Hypertensive rats untreated (water) or with vitamin C | Increased glutathione, decreased MDA, improved systemic antioxidant status, reduction systolic blood pressure | [58] | |

| Soy | Hydrolysis with pepsin and trypsin; ultrafiltration (<3 kDa) | Peptic (P) and tryptic (T) soybean hydrolysates | Antidiabetic | Range of 0.5–2.5 mg/mL | NA | HMG-CoA reductase inhibition (up to −77%), ↑LDL receptor expression and LDL uptake, DPP-IV inhibition (up to 43% in Caco-2); peptides characterized by LC-MS/MS | [42] | |

| Soy | Enzymatic in silico prediction/ peptide synthesis | Glycinin hydrolysis (Soy1 = IAVPTGVA), IC₅₀=106 µM | Antidiabetic | Concentrations ranging from 10 to 1000 μM | Sitagliptin (0.1 μM) | DPP-IV inhibitory peptide; docking confirmed binding | [43] | |

| Soy | Industrial hydrolysis, ultrafiltration | < 3 kDa peptide fraction | Antidiabetic/ Antihypertensive | DPP-IV inhibition: 0.01–2.0 mg/mL (in vitro), 1.0–5.0 mg/mL (cells); ACE inhibition: 0.08–1.0 mg/mL (in vitro), 0.1–5.0 mg/mL (cells). | Control (C) sample; growth medium and H2O | Inhibited DPP-IV (IC₅₀ = 1.15 mg/mL; < 3 kDa fraction IC₅₀ = 0.82 mg/mL) and ACE (IC₅₀ = 0.33 mg/mL; < 3 kDa fraction IC₅₀ = 0.40 mg/mL); active in Caco-2 cells | [37] | |

| Soy | Corolase PP hydrolysis (1% E:S, 4h, 50 °C) | Soy protein hydrolysate as biofunctional ingredient | Antihypertensive/ Antioxidant | 40 μL of sample | Trolox; ACE + Abz-Gly-Phe(NO2)-Pro | Improved antioxidant activity (3.9 ± 0.1 μmol TE/mg) and ACE inhibitory peptides (IC50 = 52 μg/mL) | [45] | |

| Soy | Pepsin hydrolysis of total protein extract (18 h, E/S = 1:100), ultrafiltration <3 kDa | Peptide mixtures with ACE-inhibitory activity | Antihypertensive | 983 μg/mL | Inhibitor Blank (AIB): enzyme but no inhibitor; Reaction Blank (ARB): highest inhibitor concentration but no enzyme. | ACE inhibition: IC₅₀ = 0.224 mg/mL; maximum inhibition 88% at the highest concentration tested (0.983 mg/mL) | [44] | |

| Soy | Simulation of Gastrointestinal Digestion | Germinated soybean peptides (5–10 kDa) | Antidiabetic | IC₅₀ 0.91 mg/mL | Diprotin A- | DPP-IV inhibition, active sequences from β-conglycinin, glycinin, P34 | [59] | |

| Soy | Proteinase PROTIN SD-NY10 (EC 3.4.24.28), 0.05% w/w, 50–55°C for 16 h | Soymilk hydrolysate tetrapeptide | Antihypertensive | 80 μg/kg/day (3 weeks) | Untreated SHR | Lowered BP, strong ACE inhibition | [60] | |

3.2. Production of BAPs Through Fermentation

| Source | BAPs production | Bioactivity | Ref | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatements | Outcome | Type | Dosage | Control | Outcome | ||

| Amaranth | Fermentation with various lactic acid bacteria and Bacillus spp | Multi potential dought | Antihypertensive/ Antimicrobial | 5-10 µL of sample for antioxidant and ACE-inhibtiory assays; 50 µL for antimicrobial activity assay |

Control time 0 min (unfermented amaranth dough) and 24 min (spontaneously fermented dough) | antioxidant (9.18 μM TE/L), ACE-inhibitory (80.65 %) and antimicrobial activities against pathogens | [62] |

| Amaranth seed protein hydrolysates | Fermentation with Enterococcus faecium vs. enzymatic hydrolysis | Protein hydrolysates contain novel peptides with antihypertensive activity | Antihypertensive | 0.00625 mg/mL | Blank | Enterococcus faecium hydrolysate strongest (79% inhibition) | [73] |

| Buckwheat | Solid-state fermentation with L. plantarum (12.87% inoculum, 60% moisture, 31.4 °C, 6 d) | Peptide content 22.18 mg/mL under optimal conditions; fermentation produced high peptide levels (and better flavor) | NA | NA | NA | NA | [72] |

| Chickpea | Fermentation of 20% chickpea puree with 14 LAB strains; 48 h; flours obtained by freeze-drying | Flour with enhanced bioactive peptides | Antidiabetic/ Antihypertensive | 200 µL of the sample extract | Trolox | Higher polyphenolic content; BAPs incl. DPP-IV/ACE-inhibitor candidates | [65] |

| Chickpea | Fermentation with selenium-enriched Bacillus natto | Under optimized condition (2% inoculum, 19:1 liquid-to-solid ratio (mL/g), and 40 °C) | Antihypertensive | 40 μL | HEPES (80 mmol/L) | ACE-inhibition rate ~80.7% | [66] |

| Chickpea | Solid-state fermentation with Bacillus subtilis lwo (SSF) | Peptides with MW < 10 kDa produced after 12h of fermentation (25.8 mg/g). | Antioxidant | 0.5-1 mL of extract | Control groups (blank or without extract/salicylic acid) | Antioxidant activity increases with fermentation time. | [64] |

| Chickpea | L. acidophilus fermentation of pretreated dried chickpeas | Fermented chickpea protein peptides | Antidiabetic | 5 mg/mL | Unfermented chickpea | L. acidophilus–fermented peptides suppressed α-glucosidase by >58% | [74] |

| Faba bean | Fermentation of faba bean flour with L. plantarum 299v (30 °C, 3 d) | 6 peptide sequences; most active fraction (3 kDa) contained di-/tripeptide motifs (e.g. GL, DA, MY) | Antihypertensive | NA | Control sample (without fermentation) | 3.5–7.0 kDa peptides with higher ACE inhibitory activity (IC50 of 0.28 mg/mL); | [67] |

| Lentil | Red-lentil protein isolate fermented with multiple LAB and yeasts | H. uvarum SY1 led to the highest abundance of BAPs | Antioxidant/ Antihypertensive | Different concentrations | Trolox; unfermented red lentil protein isolate | Antioxidant and ACE-inhibitory activities | [69] |

| Lupin | Solid-state fermentation with L. plantarum K779 (35 °C, 72 h) | Fermentation liberates peptides and phytochemicals | Antioxidant/ Antihypertensive | 20-200 µL | Non-inoculated samples | Enhanced antioxidant and ACE-inhibitory activity compared to raw | [70] |

| Pea | Fermentation of pea seeds with L. plantarum 299v (22 °C, 7 d) | LC fractions yielded peptide KEDDEEEEQGEEE | Antihypertensive | NA | Sample without fermentation process | After fermentation + simulated digestion, ACE inhibition IC₅₀ = 0.19 mg/mL (vs 0.37 control); | [68] |

| Quinoa | Solid-state fermentation with L. plantarum K779 (35 °C, 72 h) | Fermentation liberates peptides and phytochemicals | Antihypertensive | 20-200 µL of sample | non-inoculated samples | Enhanced antioxidant and ACE-inhibitory activity compared to raw | [70] |

| Quinoa | Solid fermentation of quinoa flour with Lactobacillus paracasei CICC 20241 | 5 potential ACE inhibitory peptides | Antihypertensive | 0.05 and 0.1 mg/mL | ACE without peptides | NIFRPFAPEL: IC50 = 49.02 µM; AALEAPRILNL IC50 = 79.72 µM) | [71] |

| Soy | Prozyme pretreated soy protein isolate fermented with Lactobacillus rhamnosus EBD1 (48 h at 37°C) | Fermented soy protein hydrolysate | Antihypertensive/ Prebiotic |

10-100 mg/kg hydrolysate per kg BW/day (6 weeks) | Spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) water or captopril | Rapid BP reduction, inhibited ACE, improved NO and SOD, remodelled gut microbiota (↓Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio) | [75] |

| Soybean peptides | NA | Novel peptides identified | Prebiotic | NA | Undigested protein, MRS, FOS | Stimulated L. reuteri growth, unique fermentation profile | [76] |

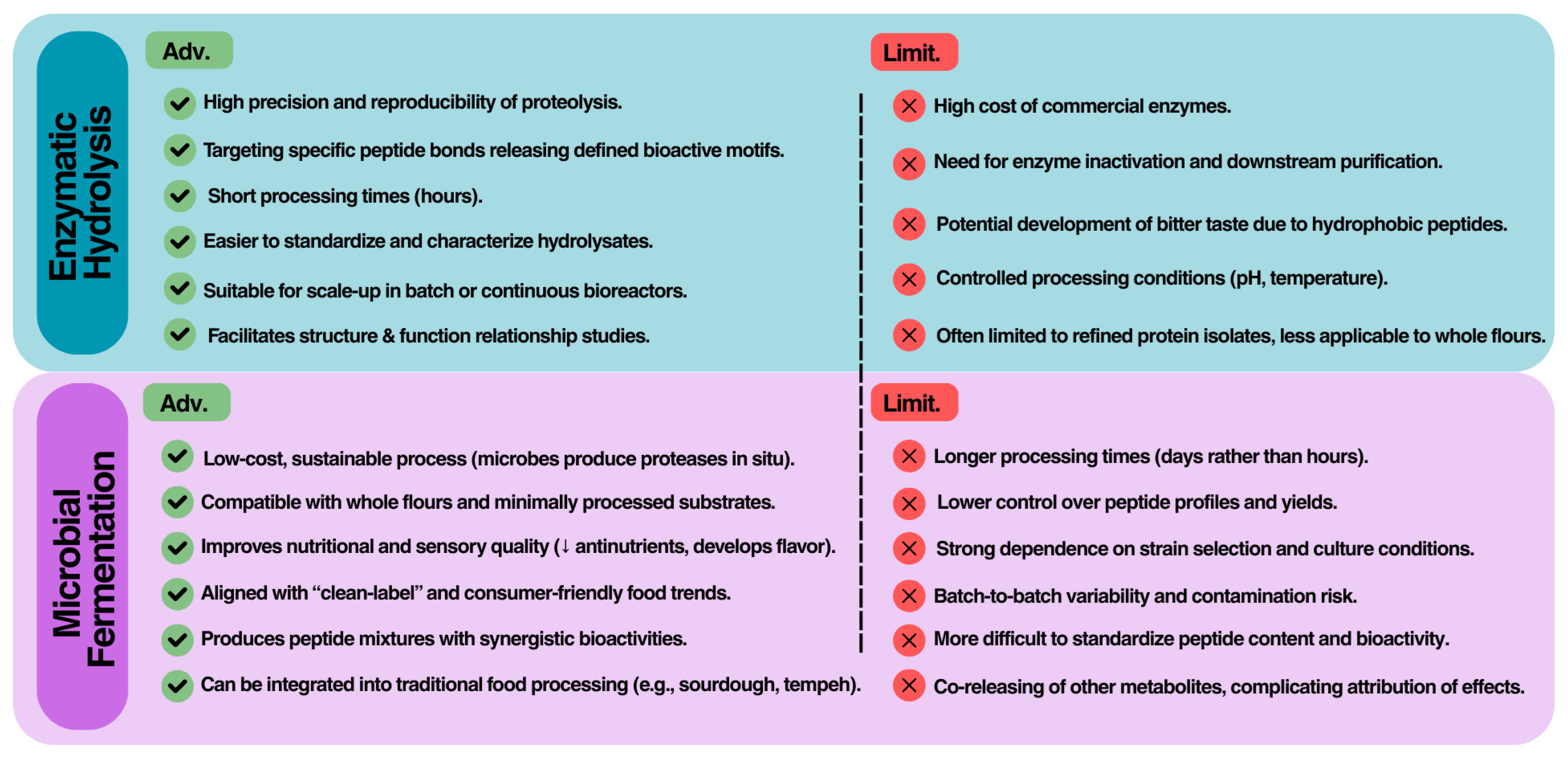

3.3. Comparative Perspective

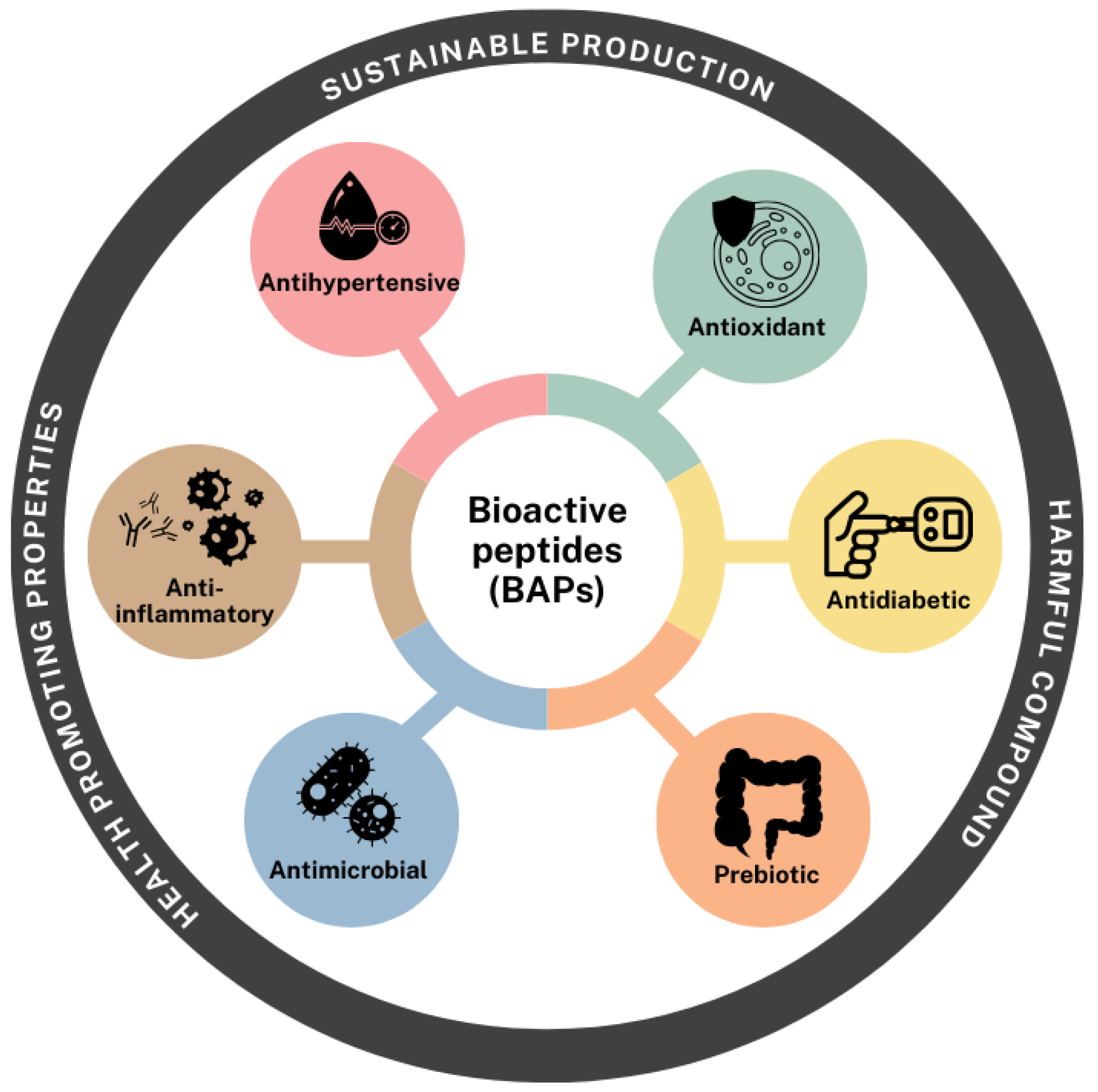

4. Bioactivities

4.1. Antioxidant Activity

4.2. Anti-Inflammatory Effect

4.3. Antihypertensive Effect

4.4. Antidiabetic Effect

4.5. Antimicrobial Capacity

4.6. Prebiotic Effect

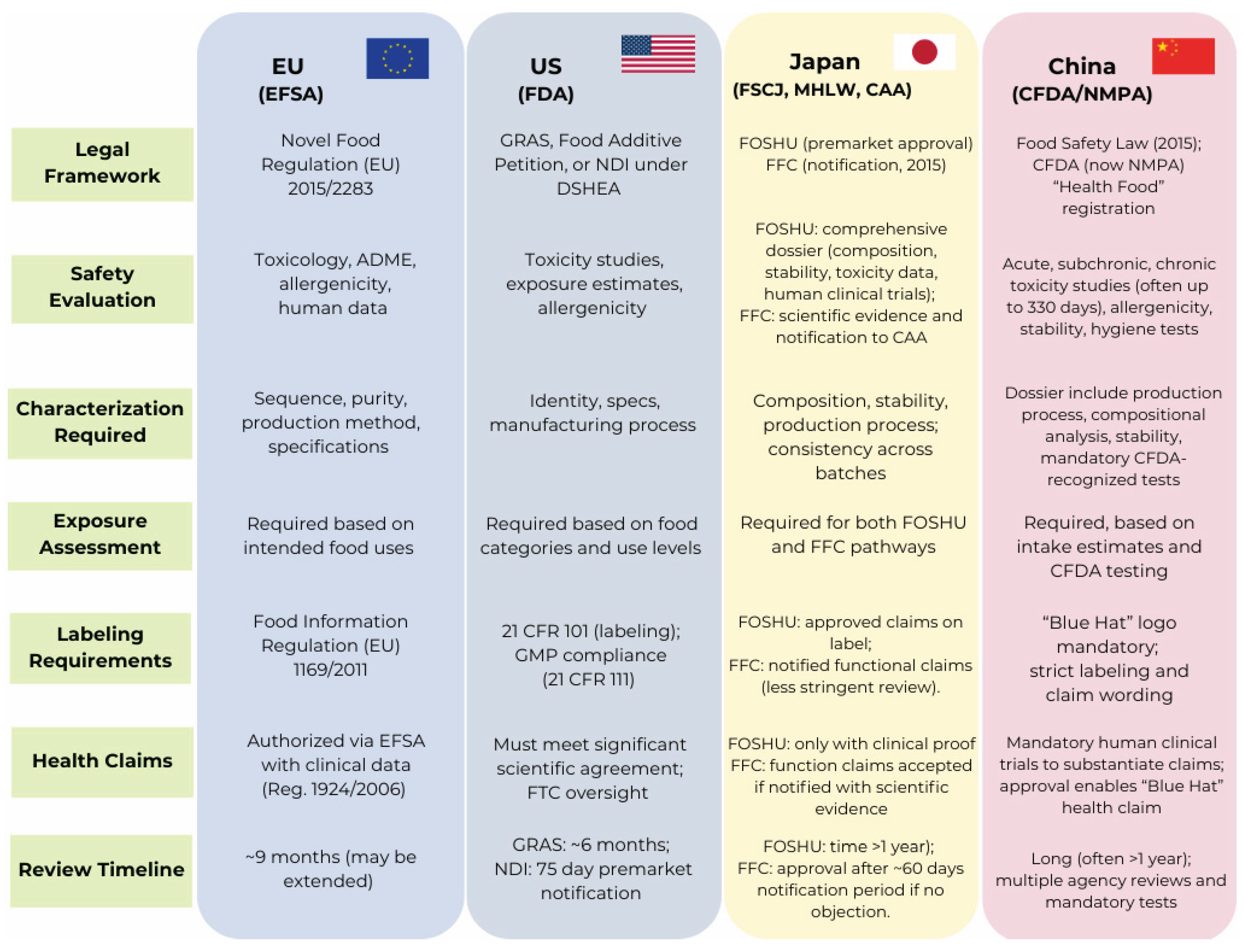

5. Regulatory Hurdles: Peptides as Novel Foods

5.1. European Regulatory Framework

5.2. United States Regulatory Framework

5.3. Japanese Regulatory Framework

5.4. Chinese Regulatory Framework

6. Challenges Limiting the Commercial Development of BAPs

7. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACE | Angiotensin-I-converting enzyme |

| ADMET | Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity |

| BAP | Bioactive peptide |

| BP | Blood pressure |

| BW | Body weight |

| Cgh | Hydrolyzed γ-conglutin |

| DPP-IV | Dipeptidyl peptidase-IV |

| E:S | Enzyme-substrate ratio |

| EAA | Essential amino acid |

| EAE | Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis |

| HFD | High-fat diet mice |

| IC₅₀ | Half-maximal Inhibitory Concentration |

| ICAM-1 | Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1 |

| IL-1β | Interleukin 1β |

| IL-6 | Interleukin 6 |

| IL-8 | Interleukin 8 |

| LAB | Lactic acid bacteria |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MD | Molecular dynamics |

| MM-GBSA | Molecular mechanics generalized Born surface area |

| MM-PBSA | Molecular mechanics Poisson–Boltzmann surface area |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| QSAR | Quantitative structure–activity relationship |

| RMSD | Root-mean-square deviation |

| SHR | Spontaneously hypertensive rats |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| TE | Tolox equivalents |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor α |

| VCAM-1 | Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule 1 |

References

- Boye, J.; Zare, F.; Pletch, A. Pulse Proteins: Processing, Characterization, Functional Properties and Applications in Food and Feed. Food Research International 2010, 43, 414–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosworthy, M.G.; Yu, B.; Zaharia, L.I.; Medina, G.; Patterson, N. Pulse Protein Quality and Derived Bioactive Peptides. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1429225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Cabrejas, M.A. Legumes: An Overview.

- Semba, R.D.; Ramsing, R.; Rahman, N.; Kraemer, K.; Bloem, M.W. Legumes as a Sustainable Source of Protein in Human Diets. Global Food Security 2021, 28, 100520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, J.; Kang, S.-I.; Lee, S.-W.; Amarasiri, R.P.G.S.K.; Nagahawatta, D.P.; Roh, Y.; Wang, L.; Ryu, B.; Jeon, Y.-J. Exploring the Potential of Olive Flounder Processing By-Products as a Source of Functional Ingredients for Muscle Enhancement. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Patil, P.J.; Mehmood, A.; Rehman, A.; Shah, H.; Haider, J.; Xu, K.; Zhang, C.; Li, X. Comparative Evaluation of Pseudocereal Peptides: A Review of Their Nutritional Contribution. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2022, 122, 287–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Shams, R.; Dash, K.K.; Dar, A.H. A Comprehensive Review of Pseudo-Cereals: Nutritional Profile, Phytochemicals Constituents and Potential Health Promoting Benefits. Applied Food Research 2023, 3, 100351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonaro, M.; Maselli, P.; Nucara, A. Structural Aspects of Legume Proteins and Nutraceutical Properties. Food Research International 2015, 76, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Patil, P.J.; Mehmood, A.; Rehman, A.; Shah, H.; Haider, J.; Xu, K.; Zhang, C.; Li, X. Comparative Evaluation of Pseudocereal Peptides: A Review of Their Nutritional Contribution. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2022, 122, 287–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, D.; Miguel, M.; Garcés-Rimón, M. Pseudocereals: A Novel Source of Biologically Active Peptides. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2021, 61, 1537–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capraro, J.; Benedetti, S.D.; Heinzl, G.C.; Scarafoni, A.; Magni, C. Bioactivities of Pseudocereal Fractionated Seed Proteins and Derived Peptides Relevant for Maintaining Human Well-Being. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Huang, H.; Li, H.; Wei, Y.; Yao, C. Legume-Derived Bioactive Peptides in Type 2 Diabetes: Opportunities and Challenges. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.K.C.; Zhang, Y.; Pechan, T. Structures, Antioxidant, and Angiotensin I-Converting Enzyme (ACE)-Inhibitory Activities of Peptides Derived from Protein Hydrolysates of Three Phenolics-Rich Legume Genera. Journal of Food Science 2025, 90, e70069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca Hernandez, D.; Mojica, L.; Gonzalez de Mejia, E. Legume-Derived Bioactive Peptides: Role in Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Control. Current Opinion in Food Science 2024, 56, 101132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawalbeh, D.; Al-U’datt, M.H.; Wan Ahmad, W.A.N.; Ahmad, F.; Sarbon, N.M. Recent Advances in In Vitro and In Vivo Studies of Antioxidant, ACE-Inhibitory and Anti-Inflammatory Peptides from Legume Protein Hydrolysates. Molecules 2023, 28, 2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aderinola, T.A.; Duodu, K.G. Production, Health-Promoting Properties and Characterization of Bioactive Peptides from Cereal and Legume Grains. BioFactors 2022, 48, 972–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, H.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, T.; Wang, D. Review on Plant-Derived Bioactive Peptides: Biological Activities, Mechanism of Action and Utilizations in Food Development. Journal of Future Foods 2022, 2, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharibzahedi, S.M.T.; Smith, B.; Altintas, Z. Bioactive and Health-Promoting Properties of Enzymatic Hydrolysates of Legume Proteins: A Review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2024, 64, 2548–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luzardo-Ocampo, I.; Gonzalez de Mejia, E. Plant Proteins and Peptides as Key Contributors to Good Health: A Focus on Pulses. Food Research International 2025, 211, 116346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho Oliveira, L.; Martinez-Villaluenga, C.; Frias, J.; Elena Cartea, M.; Francisco, M.; Cristianini, M.; Peñas, E. High Pressure-Assisted Enzymatic Hydrolysis Potentiates the Production of Quinoa Protein Hydrolysates with Antioxidant and ACE-Inhibitory Activities. Food Chemistry 2024, 447, 138887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvankhah, A.; Yarmand, M.S.; Ghanbarzadeh, B.; Mirzaee, H. Development of Lentil Peptides with Potent Antioxidant, Antihypertensive, and Antidiabetic Activities along with Umami Taste. Food Science & Nutrition 2023, 11, 2974–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Wang, Q.; Shao, Z.; Wang, X.; Cao, H.; Huang, K.; Sun, Q.; Sun, Z.; Guan, X. In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion of Buckwheat ( Fagopyrum Esculentum Moench) Protein: Release and Structural Characteristics of Novel Bioactive Peptides Stimulating Gut Cholecystokinin Secretion. Food & Function 2023, 14, 7469–7477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, T.; Yu, W.; Zhou, J.; Bian, Y.; Li, S.; Chen, Y. Pea Power against Microbes: Elucidating the Characteristics and Antimicrobial Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Peptides Obtained through Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Pea Protein Isolate. Food Bioscience 2025, 65, 106075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Comer, J.; Li, Y. Bioinformatics Approaches to Discovering Food-Derived Bioactive Peptides: Reviews and Perspectives. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2023, 162, 117051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FitzGerald, R.J.; Cermeño, M.; Khalesi, M.; Kleekayai, T.; Amigo-Benavent, M. Application of in Silico Approaches for the Generation of Milk Protein-Derived Bioactive Peptides. Journal of Functional Foods 2020, 64, 103636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, W.; Chen, L.; Qin, D.; Geng, S.; Li, J.; Mei, H.; Li, B.; Liang, G. Application of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship to Food-Derived Peptides: Methods, Situations, Challenges and Prospects. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2021, 114, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Limon, A.; Aguilar-Toalá, J.E.; Liceaga, A.M. Integration of Molecular Docking Analysis and Molecular Dynamics Simulations for Studying Food Proteins and Bioactive Peptides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 934–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandes, N.; Ofer, D.; Peleg, Y.; Rappoport, N.; Linial, M. ProteinBERT: A Universal Deep-Learning Model of Protein Sequence and Function. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 2102–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peredo-Lovillo, A.; Hernández-Mendoza, A.; Vallejo-Cordoba, B.; Romero-Luna, H.E. Conventional and in Silico Approaches to Select Promising Food-Derived Bioactive Peptides: A Review. Food Chemistry: X 2022, 13, 100183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Shen, X.; Chen, W.; Wu, D.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, P.; Liu, Y.; Li, W.; Yang, Y. A Screening Strategy for Bioactive Peptides from Enzymolysis Extracts of Lentinula Edodes Based on Molecular Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Journal of Future Foods 2025, 5, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres Fabbri, L.; Cavallero, A.; Vidotto, F.; Gabriele, M. Bioactive Peptides from Fermented Foods: Production Approaches, Sources, and Potential Health Benefits. Foods 2024, 13, 3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, F.F.; Mudgil, P.; Jobe, A.; Antony, P.; Vijayan, R.; Gan, C.-Y.; Maqsood, S. Novel Plant-Protein (Quinoa) Derived Bioactive Peptides with Potential Anti-Hypercholesterolemic Activities: Identification, Characterization and Molecular Docking of Bioactive Peptides. Foods 2023, 12, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Melgem, J.A.; Arámburo-Gálvez, J.G.; Cárdenas-Torres, F.I.; Gonzalez-Santamaria, J.; Ramírez-Torres, G.I.; Arvizu-Flores, A.A.; Figueroa-Salcido, O.G.; Ontiveros, N. Dipeptidyl Peptidase IV Inhibitory Peptides from Chickpea Proteins (Cicer Arietinum L.): Pharmacokinetics, Molecular Interactions, and Multi-Bioactivities. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero-Soto, M.F.; Chávez-Ontiveros, J.; Garzón-Tiznado, J.A.; Salazar-Salas, N.Y.; Pineda-Hidalgo, K.V.; Delgado-Vargas, F.; López-Valenzuela, J.A. Characterization of Peptides with Antioxidant Activity and Antidiabetic Potential Obtained from Chickpea (Cicer Arietinum L.) Protein Hydrolyzates. Journal of Food Science 2021, 86, 2962–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubczyk, A.; Baraniak, B. Activities and Sequences of the Angiotensin I-Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitory Peptides Obtained from the Digested Lentil (Lens Culinaris) Globulins. International Journal of Food Science & Technology 2013, 48, 2363–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Mora, P.; Peñas, E.; Frias, J.; Gomez, R.; Martinez-Villaluenga, C. High-Pressure Improves Enzymatic Proteolysis and the Release of Peptides with Angiotensin I Converting Enzyme Inhibitory and Antioxidant Activities from Lentil Proteins. Food Chemistry 2015, 171, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollati, C.; Xu, R.; Boschin, G.; Bartolomei, M.; Rivardo, F.; Li, J.; Arnoldi, A.; Lammi, C. Integrated Evaluation of the Multifunctional DPP-IV and ACE Inhibitory Effect of Soybean and Pea Protein Hydrolysates. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asledottir, T.; Vegarud, G.E.; Picariello, G.; Mamone, G.; Lea, T.E.; Røseth, A.; Ferranti, P.; Devold, T.G. Bioactive Peptides Identified in Pea and Faba Bean after in Vitro Digestion with Human Gastrointestinal Enzymes. Journal of Functional Foods 2023, 102, 105445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilcacundo, R.; Miralles, B.; Carrillo, W.; Hernández-Ledesma, B. In Vitro Chemopreventive Properties of Peptides Released from Quinoa (Chenopodium Quinoa Willd.) Protein under Simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion. Food Research International 2018, 105, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasi, S.; Moslehishad, M.; Salami, M. Antioxidant and Alpha-Glucosidase Enzyme Inhibitory Properties of Hydrolyzed Protein and Bioactive Peptides of Quinoa. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2022, 213, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala-Niño, A.; Rodríguez-Serrano, G.M.; González-Olivares, L.G.; Contreras-López, E.; Regal-López, P.; Cepeda-Saez, A. Sequence Identification of Bioactive Peptides from Amaranth Seed Proteins (Amaranthus Hypochondriacus Spp.). Molecules 2019, 24, 3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammi, C.; Arnoldi, A.; Aiello, G. Soybean Peptides Exert Multifunctional Bioactivity Modulating 3-Hydroxy-3-Methylglutaryl-CoA Reductase and Dipeptidyl Peptidase-IV Targets in Vitro. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 4824–4830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammi, C.; Zanoni, C.; Arnoldi, A.; Vistoli, G. Peptides Derived from Soy and Lupin Protein as Dipeptidyl-Peptidase IV Inhibitors: In Vitro Biochemical Screening and in Silico Molecular Modeling Study. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 9601–9606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boschin, G.; Scigliuolo, G.M.; Resta, D.; Arnoldi, A. ACE-Inhibitory Activity of Enzymatic Protein Hydrolysates from Lupin and Other Legumes. Food Chemistry 2014, 145, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coscueta, E.R.; Campos, D.A.; Osório, H.; Nerli, B.B.; Pintado, M. Enzymatic Soy Protein Hydrolysis: A Tool for Biofunctional Food Ingredient Production. Food Chemistry: X 2019, 1, 100006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiersnowska, K.; Jakubczyk, A. Bioactive Peptides Obtained from Legume Seeds as New Compounds in Metabolic Syndrome Prevention and Diet Therapy. Foods 2022, 11, 3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, Z.; Muangnapoh, C.; Suthienkul, O.; Suriyarak, S.; Duangmal, K. Exploring Novel Peptides in Adzuki Bean and Mung Bean Hydrolysates with Potent Antibacterial Activity. Int J Food Sci Tech 2024, 59, 4829–4840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.; Enan, G.; Al-Mohammadi, A.-R.; Abdel-Shafi, S.; Abdel-Hameid, S.; Sitohy, M.Z.; El-Gazzar, N. Antibacterial Peptides Produced by Alcalase from Cowpea Seed Proteins. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco-Castilla, J.; Hernández-Álvarez, A.J.; Jiménez-Martínez, C.; Jacinto-Hernández, C.; Alaiz, M.; Girón-Calle, J.; Vioque, J.; Dávila-Ortiz, G. Antioxidant and Metal Chelating Activities of Peptide Fractions from Phaseolin and Bean Protein Hydrolysates. Food Chemistry 2012, 135, 1789–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Chamorro, I.; Santos-Sánchez, G.; Bollati, C.; Bartolomei, M.; Capriotti, A.L.; Cerrato, A.; Laganà, A.; Pedroche, J.; Millán, F.; del Carmen Millán-Linares, M.; et al. Chemical and Biological Characterization of the DPP-IV Inhibitory Activity Exerted by Lupin (Lupinus Angustifolius) Peptides: From the Bench to the Bedside Investigation. Food Chemistry 2023, 426, 136458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, E.B.; Luna-Vital, D.A.; Fornasini, M.; Baldeón, M.E.; Gonzalez de Mejia, E. Gamma-Conglutin Peptides from Andean Lupin Legume (Lupinus Mutabilis Sweet) Enhanced Glucose Uptake and Reduced Gluconeogenesis in Vitro. Journal of Functional Foods 2018, 45, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montserrat-de la Paz, S.; Villanueva, A.; Pedroche, J.; Millan, F.; Martin, M.E.; Millan-Linares, M.C. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Bioavailable Protein Hydrolysates from Lupin-Derived Agri-Waste. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Chamorro, I.; Álvarez-López, A.I.; Santos-Sánchez, G.; Álvarez-Sánchez, N.; Pedroche, J.; Millán-Linares, M. del C.; Lardone, P.J.; Carrillo-Vico, A. A Lupin (Lupinus Angustifolius) Protein Hydrolysate Decreases the Severity of Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis: A Preliminary Study. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce-España, E.; Cruz-Chamorro, I.; Santos-Sánchez, G.; Álvarez-López, A.I.; Fernández-Santos, J.M.; Pedroche, J.; Millán-Linares, M.C.; Bejarano, I.; Lardone, P.J.; Carrillo-Vico, A. Anti-Obesogenic Effect of Lupin-Derived Protein Hydrolysate through Modulation of Adiposopathy, Insulin Resistance and Gut Dysbiosis in a Diet-Induced Obese Mouse. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2024, 178, 117198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zheng, Y.; Xu, J.; Sang, S.; Liu, Y. A Novel Antihypertensive Pentapeptide Identified in Quinoa Bran Globulin Hydrolysates: Purification, In Silico Characterization, Molecular Docking with ACE and Stability against Different Food-Processing Conditions. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho Oliveira, L.; Martinez-Villaluenga, C.; Frias, J.; Elena Cartea, M.; Francisco, M.; Cristianini, M.; Peñas, E. High Pressure-Assisted Enzymatic Hydrolysis Potentiates the Production of Quinoa Protein Hydrolysates with Antioxidant and ACE-Inhibitory Activities. Food Chemistry 2024, 447, 138887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capraro, J.; Benedetti, S.D.; Heinzl, G.C.; Scarafoni, A.; Magni, C. Bioactivities of Pseudocereal Fractionated Seed Proteins and Derived Peptides Relevant for Maintaining Human Well-Being. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Moreno, M.; Jiménez-Moreno, E.; Márquez Gallego, A.; Vera Pasamontes, G.; Uranga Ocio, J.A.; Garcés-Rimón, M.; Miguel-Castro, M. Red Quinoa Hydrolysates with Antioxidant Properties Improve Cardiovascular Health in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Montoya, M.; Hernández-Ledesma, B.; Mora-Escobedo, R.; Martínez-Villaluenga, C. Bioactive Peptides from Germinated Soybean with Anti-Diabetic Potential by Inhibition of Dipeptidyl Peptidase-IV, α-Amylase, and α-Glucosidase Enzymes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2018, 19, 2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alauddin, M.; Amin, M.R.; Siddiquee, M.A.; Hiwatashi, K.; Shimakage, A.; Takahashi, S.; Shinbo, M.; Komai, M.; Shirakawa, H. In Silico and in Vivo Experiment of Soymilk Peptide (Tetrapeptide - FFYY) for the Treatment of Hypertension. Peptides 2024, 175, 171170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, M.J.; Bala, A.; Khan, M.R.; Mukherjee, A.K. Functional Impact of Bioactive Peptides Derived from Fermented Foods on Diverse Human Populations. Food Chemistry 2025, 492, 145416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Casas, D.E.; Aguilar, C.N.; Ascacio-Valdés, J.A.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R.; Chávez-González, M.L.; Flores-Gallegos, A.C. Bioactive Protein Hydrolysates Obtained from Amaranth by Fermentation with Lactic Acid Bacteria and Bacillus Species. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzello, C.G.; Nionelli, L.; Coda, R.; Gobbetti, M. Synthesis of the Cancer Preventive Peptide Lunasin by Lactic Acid Bacteria During Sourdough Fermentation. Nutrition and Cancer 2012, 64, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Wang, T. Effect of Solid-State Fermentation with Bacillus Subtilis Lwo on the Proteolysis and the Antioxidative Properties of Chickpeas. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2021, 338, 108988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiacchio, M.F.; Tagliamonte, S.; Pazzanese, A.; Vitaglione, P.; Blaiotta, G. Lactic Acid Fermentation Improves Nutritional and Functional Properties of Chickpea Flours. Food Research International 2025, 203, 115899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Che, J.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, B.; Wei, L.; Rong, L.; Li, R. ACE Inhibitory Peptides and Flavor Compounds from Se-Enriched Bacillus Natto Fermented Chickpea. LWT 2025, 215, 117190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubczyk, A.; Karaś, M.; Złotek, U.; Szymanowska, U. Identification of Potential Inhibitory Peptides of Enzymes Involved in the Metabolic Syndrome Obtained by Simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion of Fermented Bean (Phaseolus Vulgaris L.) Seeds. Food Research International 2017, 100, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubczyk, A.; Karaś, M.; Baraniak, B.; Pietrzak, M. The Impact of Fermentation and in Vitro Digestion on Formation Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitory Peptides from Pea Proteins. Food Chemistry 2013, 141, 3774–3780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonini, S.; Tlais, A.Z.A.; Galli, B.D.; Helal, A.; Tagliazucchi, D.; Filannino, P.; Zannini, E.; Gobbetti, M.; Di Cagno, R. Lentils Protein Isolate as a Fermenting Substrate for the Production of Bioactive Peptides by Lactic Acid Bacteria and Neglected Yeast Species. Microbial Biotechnology 2024, 17, e14387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyash, M.; Johnson, S.K.; Liu, S.-Q.; Mesmari, N.; Dahmani, S.; Al Dhaheri, A.S.; Kizhakkayil, J. In Vitro Investigation of Bioactivities of Solid-State Fermented Lupin, Quinoa and Wheat Using Lactobacillus Spp. Food Chemistry 2019, 275, 50–58. Food Chemistry 2019, 275, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Du, G.; Shi, J.; Zhang, L.; Yue, T.; Yuan, Y. Preparation of Antihypertensive Peptides from Quinoa via Fermentation with Lactobacillus Paracasei. eFood 2022, 3, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Ma, T. Production of Bioactive Peptides from Tartary Buckwheat by Solid-State Fermentation with Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum ATCC 14917. Foods 2024, 13, 3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Casas, D.E.; Ramos-González, R.; Prado-Barragán, L.A.; Iliná, A.; Aguilar, C.N.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R.; Tsopmo, A.; Flores-Gallegos, A.C. Protein Hydrolysates with ACE-I Inhibitory Activity from Amaranth Seeds Fermented with Enterococcus Faecium-LR9: Identification of Peptides and Molecular Docking. Food Chemistry 2025, 464, 141598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Fan, X.; Wang, D.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Yang, J.; Qiu, C.; Liu, X.; Pang, G.; Abra, R.; et al. Study on Preparation of Chickpea Peptide and Its Effect on Blood Glucose. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daliri, E.B.-M.; Ofosu, F.K.; Chelliah, R.; Lee, B.H.; An, H.; Elahi, F.; Barathikannan, K.; Kim, J.-H.; Oh, D.-H. Influence of Fermented Soy Protein Consumption on Hypertension and Gut Microbial Modulation in Spontaneous Hypertensive Rats. Bioscience of Microbiota, Food and Health 2020, 39, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xia, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, S.; Li, H.; Liu, X. Identification of Soybean Peptides and Their Effect on the Growth and Metabolism of Limosilactobacillus Reuteri LR08. Food Chemistry 2022, 369, 130923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nongonierma, A.B.; Le Maux, S.; Dubrulle, C.; Barre, C.; FitzGerald, R.J. Quinoa (Chenopodium Quinoa Willd.) Protein Hydrolysates with in Vitro Dipeptidyl Peptidase IV (DPP-IV) Inhibitory and Antioxidant Properties. Journal of Cereal Science 2015, 65, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihlanto, A. Antioxidative Peptides Derived from Milk Proteins. International Dairy Journal 2006, 16, 1306–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, M.; Yuan, P.; Xu, W.; Jiang, T.; Huang, J. Tartary Buckwheat Peptides Prevent Oxidative Damage in Differentiated SOL8 Cells via a Mitochondria-Mediated Apoptosis Pathway. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Liu, X. Purification, Identification and Evaluation of Antioxidant Peptides from Pea Protein Hydrolysates. Molecules 2023, 28, 2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Zhu, Y.; Shi, Z.; Li, J. Detection of Lunasin in Quinoa (Chenopodium Quinoa Willd.) and the in Vitro Evaluation of Its Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activities. J Sci Food Agric 2017, 97, 4110–4116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, S.; Majumder, K. Efficacy of Great Northern Beans-Derived Bioactive Compounds in Reducing Vascular Inflammation. Food Bioscience 2024, 57, 103524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieffer, T.J.; McIntosh, C.H.; Pederson, R.A. Degradation of Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide and Truncated Glucagon-like Peptide 1 in Vitro and in Vivo by Dipeptidyl Peptidase IV. Endocrinology 1995, 136, 3585–3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tetteh, J.; Wereko Brobbey, D.-Y.; Osei, K.J.; Ayamah, A.; Laryea, M.K.; Darko, G.; Borquaye, L.S. Peptide Extract from Red Kidney Beans, Phaseolus Vulgaris (Fabaceae), Shows Promising Antimicrobial, Antibiofilm, and Quorum Sensing Inhibitory Effects. Biochemistry Research International 2024, 2024, 4667379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, G.R.; Hutkins, R.; Sanders, M.E.; Prescott, S.L.; Reimer, R.A.; Salminen, S.J.; Scott, K.; Stanton, C.; Swanson, K.S.; Cani, P.D.; et al. Expert Consensus Document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) Consensus Statement on the Definition and Scope of Prebiotics. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017, 14, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Precup, G.; Marini, E.; Zakidou, P.; Beneventi, E.; Consuelo, C.; Fernández-Fraguas, C.; Garcia Ruiz, E.; Laganaro, M.; Magani, M.; Mech, A.; et al. Novel Foods, Food Enzymes, and Food Additives Derived from Food by-Products of Plant or Animal Origin: Principles and Overview of the EFSA Safety Assessment. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vettorazzi, A.; López de Cerain, A.; Sanz-Serrano, J.; Gil, A.G.; Azqueta, A. European Regulatory Framework and Safety Assessment of Food-Related Bioactive Compounds. Nutrients 2020, 12, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalamaiah, M.; Keskin Ulug, S.; Hong, H.; Wu, J. Regulatory Requirements of Bioactive Peptides (Protein Hydrolysates) from Food Proteins. Journal of Functional Foods 2019, 58, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation - 1924/2006 - EN - EUR-Lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2006/1924/oj/eng (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Regulation - 2015/2283 - EN - EUR-Lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2015/2283/oj/eng (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA); Turck, D. ; Bresson, J.-L.; Burlingame, B.; Dean, T.; Fairweather-Tait, S.; Heinonen, M.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.I.; Mangelsdorf, I.; McArdle, H.J.; et al. Scientific and Technical Guidance for the Preparation and Presentation of a Health Claim Application (Revision 2). EFSA Journal 2017, 15, e04680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA) Products; Nutrition; (nda), A. ; Turck, D.; Bresson, J.-L.; Burlingame, B.; Dean, T.; Fairweather-Tait, S.; Heinonen, M.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.I.; et al. Guidance on the Preparation and Submission of an Application for Authorisation of a Novel Food in the Context of Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 (Revision 1)2. EFSA Journal 2021, 19, e06555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Program, H.F. New Dietary Ingredient (NDI) Notification Process. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/dietary-supplements/new-dietary-ingredient-ndi-notification-process (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Program, H.F. Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS). Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/food-ingredients-packaging/generally-recognized-safe-gras (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- 21 CFR Part 101 -- Food Labeling. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/part-101 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- 21 CFR Part 111 -- Current Good Manufacturing Practice in Manufacturing, Packaging, Labeling, or Holding Operations for Dietary Supplements. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/part-111 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Hobbs, J.E.; Malla, S.; Sogah, E.K. Regulatory Frameworks for Functional Food and Supplements. Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics/Revue canadienne d’agroeconomie 2014, 62, 569–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, P.J.; Usman, M.; Zhang, C.; Mehmood, A.; Zhou, M.; Teng, C.; Li, X. An Updated Review on Food-Derived Bioactive Peptides: Focus on the Regulatory Requirements, Safety, and Bioavailability. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2022, 21, 1732–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.; Dufour, Y.; Domigan, N. Functional Food and Nutraceutical Registration Processes in Japan and China: A Diffusion of Innovation Perspective. Journal of Pharmacy & Pharmaceutical Sciences 2008, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, S.; Guha, S.; Majumder, K. Food-Derived Bioactive Peptides in Human Health: Challenges and Opportunities. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, H.; Tao, X.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Y.; Yu, Q.; Xie, J. Food-Derived Bioactive Peptides: Production, Biological Activities, Opportunities and Challenges. Journal of Future Foods 2022, 2, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barati, M.; Javanmardi, F.; Mousavi Jazayeri, S.M.H.; Jabbari, M.; Rahmani, J.; Barati, F.; Nickho, H.; Davoodi, S.H.; Roshanravan, N.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A. Techniques, Perspectives, and Challenges of Bioactive Peptide Generation: A Comprehensive Systematic Review. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2020, 19, 1488–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tagliamonte, S.; Oliviero, V.; Vitaglione, P. Food Bioactive Peptides: Functionality beyond Bitterness. Nutr Rev 2025, 83, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezvankhah, A.; Yarmand, M.S.; Ghanbarzadeh, B.; Mirzaee, H. Characterization of Bioactive Peptides Produced from Green Lentil (Lens Culinaris) Seed Protein Concentrate Using Alcalase and Flavourzyme in Single and Sequential Hydrolysis. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation 2021, 45, e15932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Görgüç, A.; Gençdağ, E.; Yılmaz, F.M. Bioactive Peptides Derived from Plant Origin By-Products: Biological Activities and Techno-Functional Utilizations in Food Developments – A Review. Food Research International 2020, 136, 109504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Huang, H.; Li, H.; Wei, Y.; Yao, C. Legume-Derived Bioactive Peptides in Type 2 Diabetes: Opportunities and Challenges. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).