Submitted:

26 September 2025

Posted:

02 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

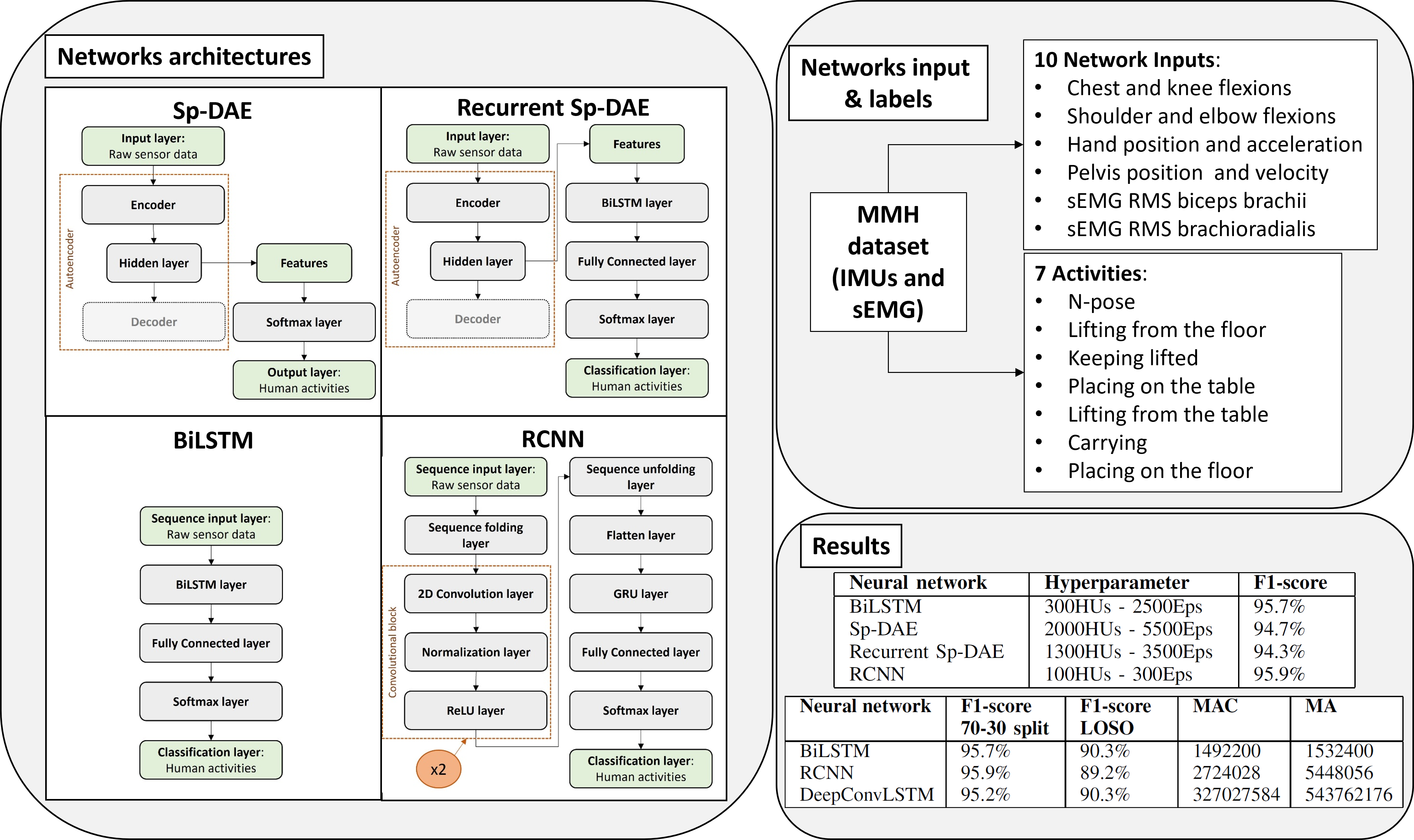

- BiLSTM;

- Sparse Denoising Autoencoder (Sp-DAE);

- Recurrent Sp-DAE;

- Recurrent CNN (RCNN).

2. Background

2.1. Recurrent Neural Network

2.2. Autoencoder

2.3. Convolutional Neural Networks

2.4. Hybrid Networks

2.4.1. Recurrent Convolutional Neural Networks

2.4.2. Recurrent Autoencoder Networks

2.5. Selected Architectures

3. Methods and Materials

3.1. Dataset and Networks Input

3.2. Network Architectures

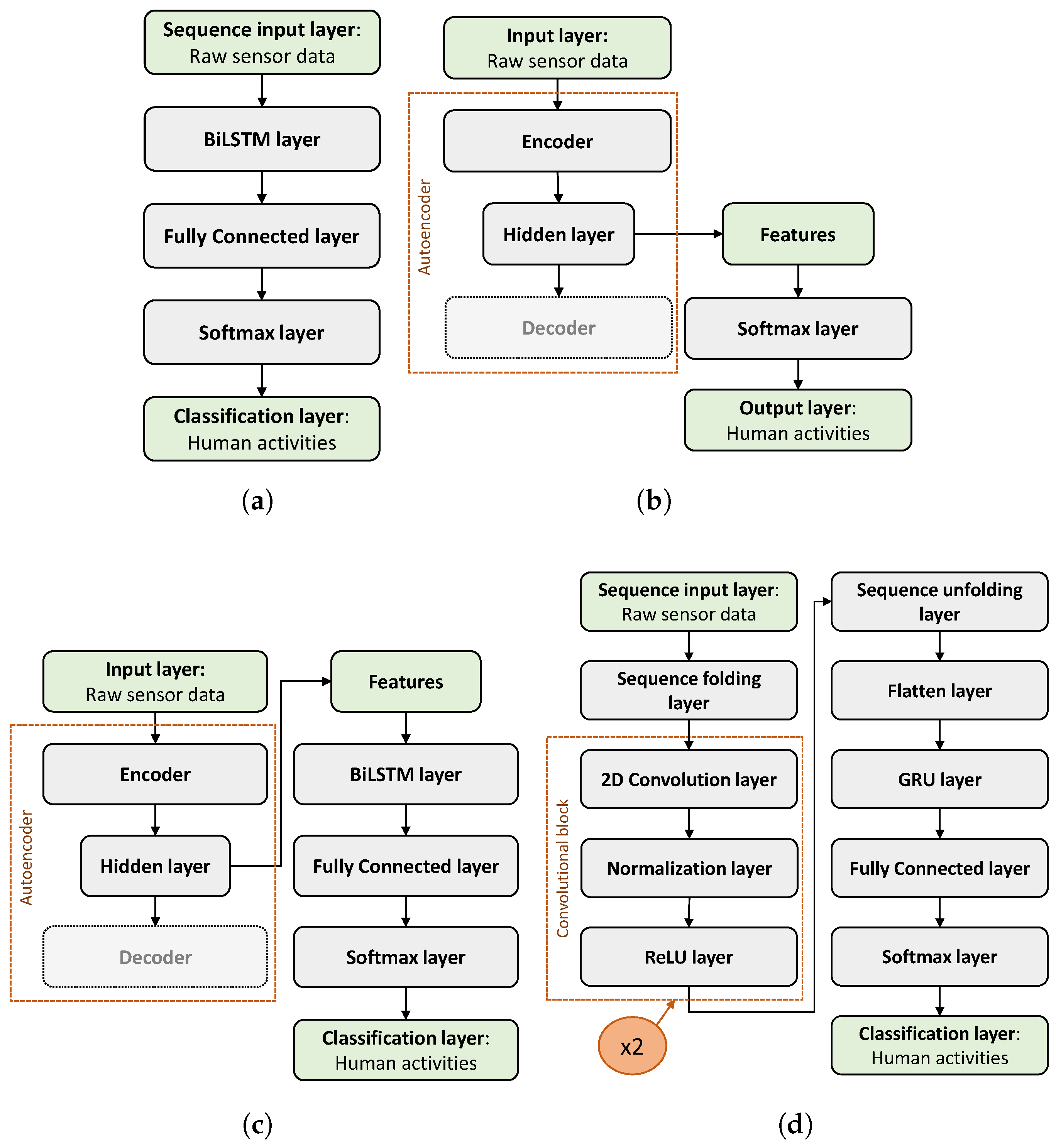

3.2.1. BiLSTM

3.2.2. Autoencoder

3.2.3. Recurrent Sp-DAE

3.2.4. RCNN

3.3. Networks Training and Testing

3.3.1. Metrics

4. Results

4.1. Best parameters selection

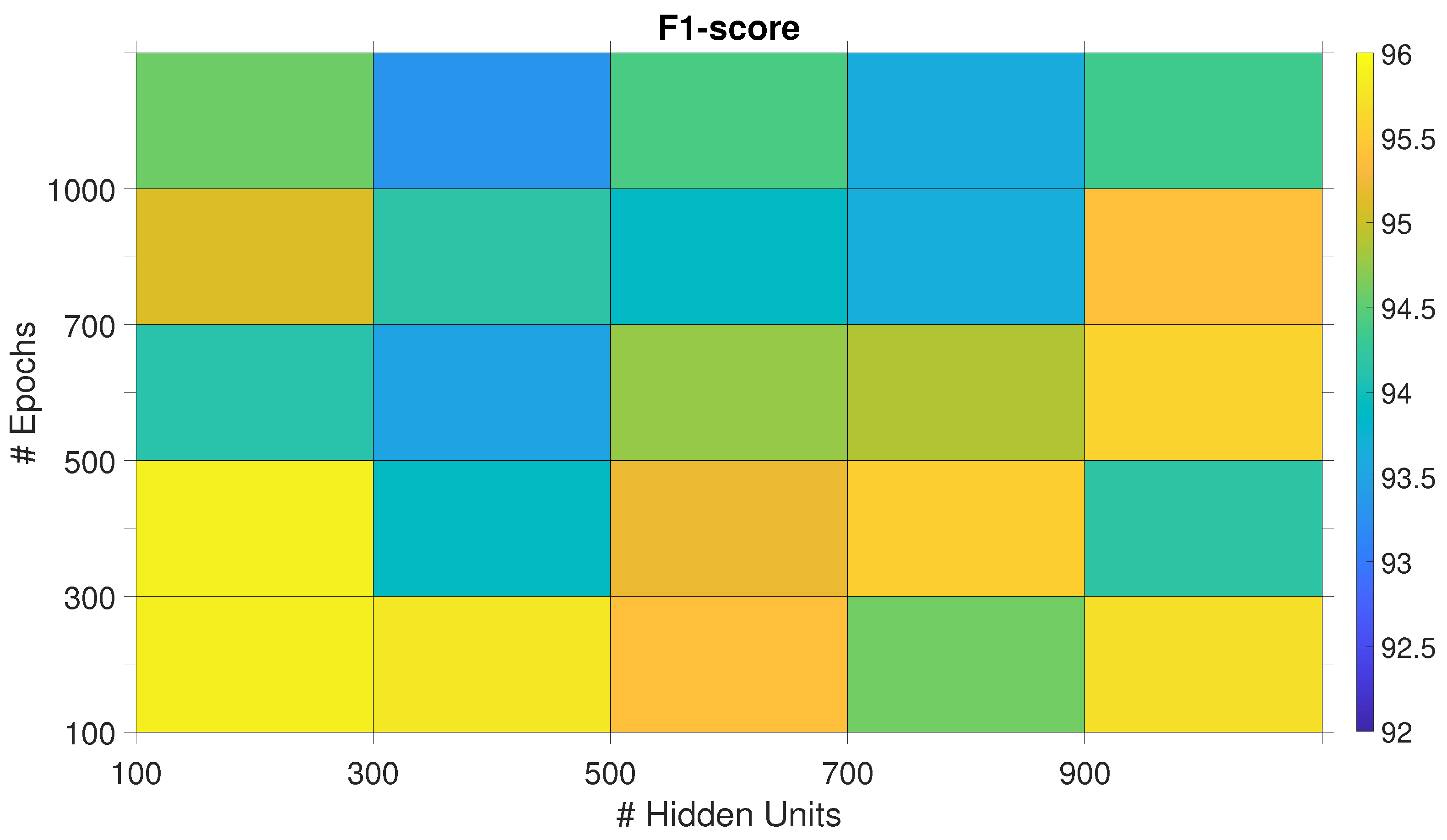

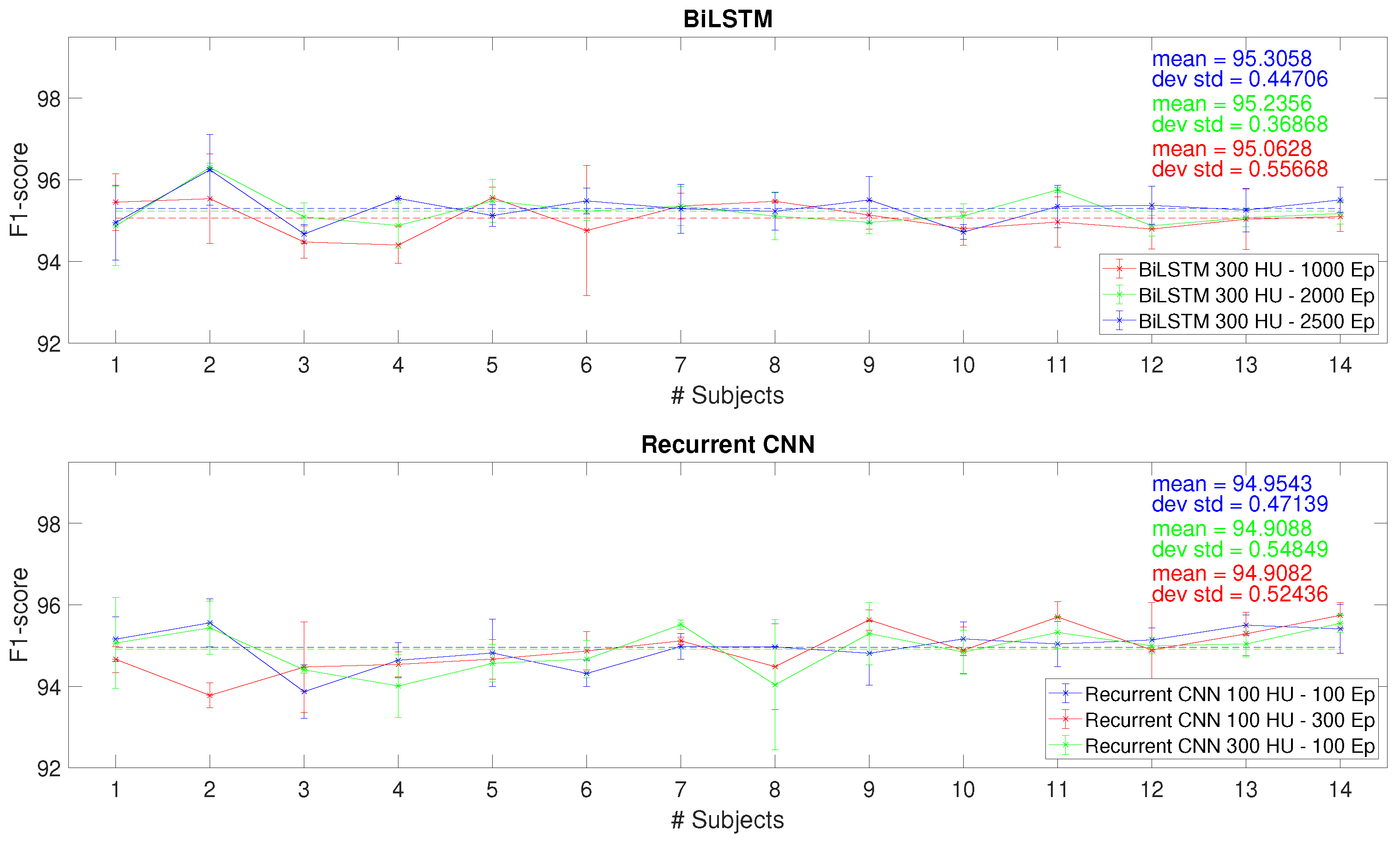

4.1.1. BiLSTM

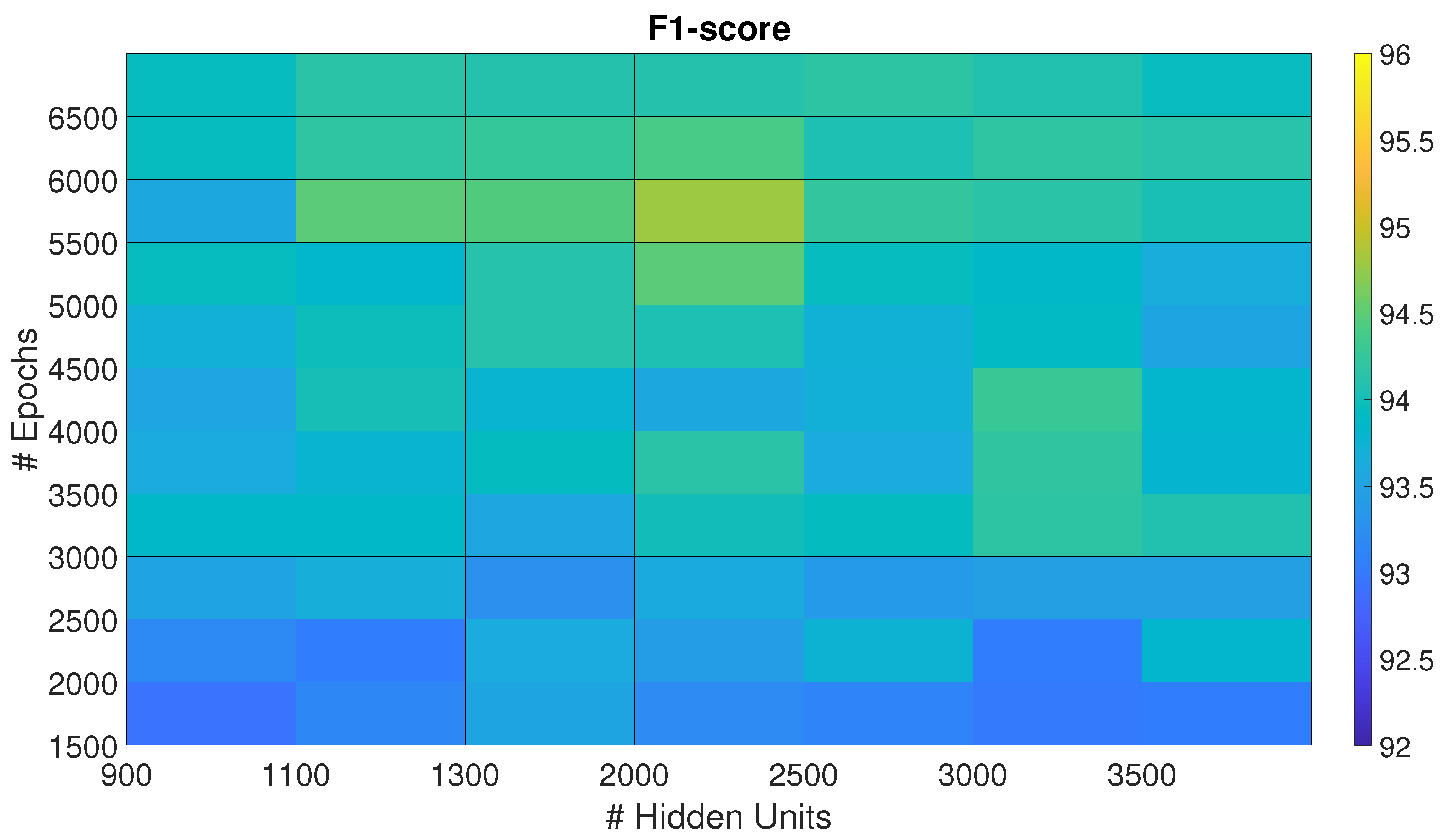

4.1.2. Sp-DAE

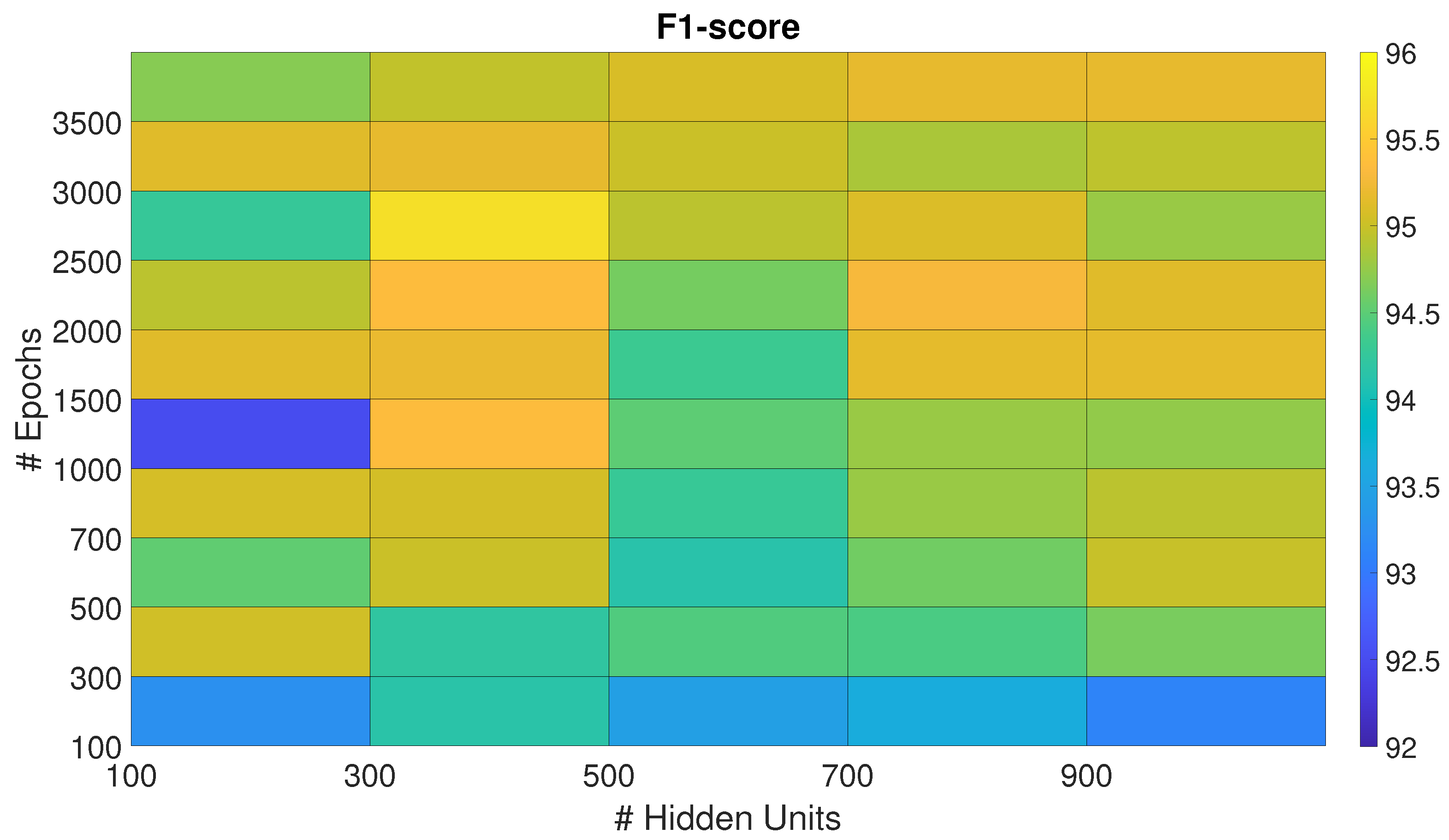

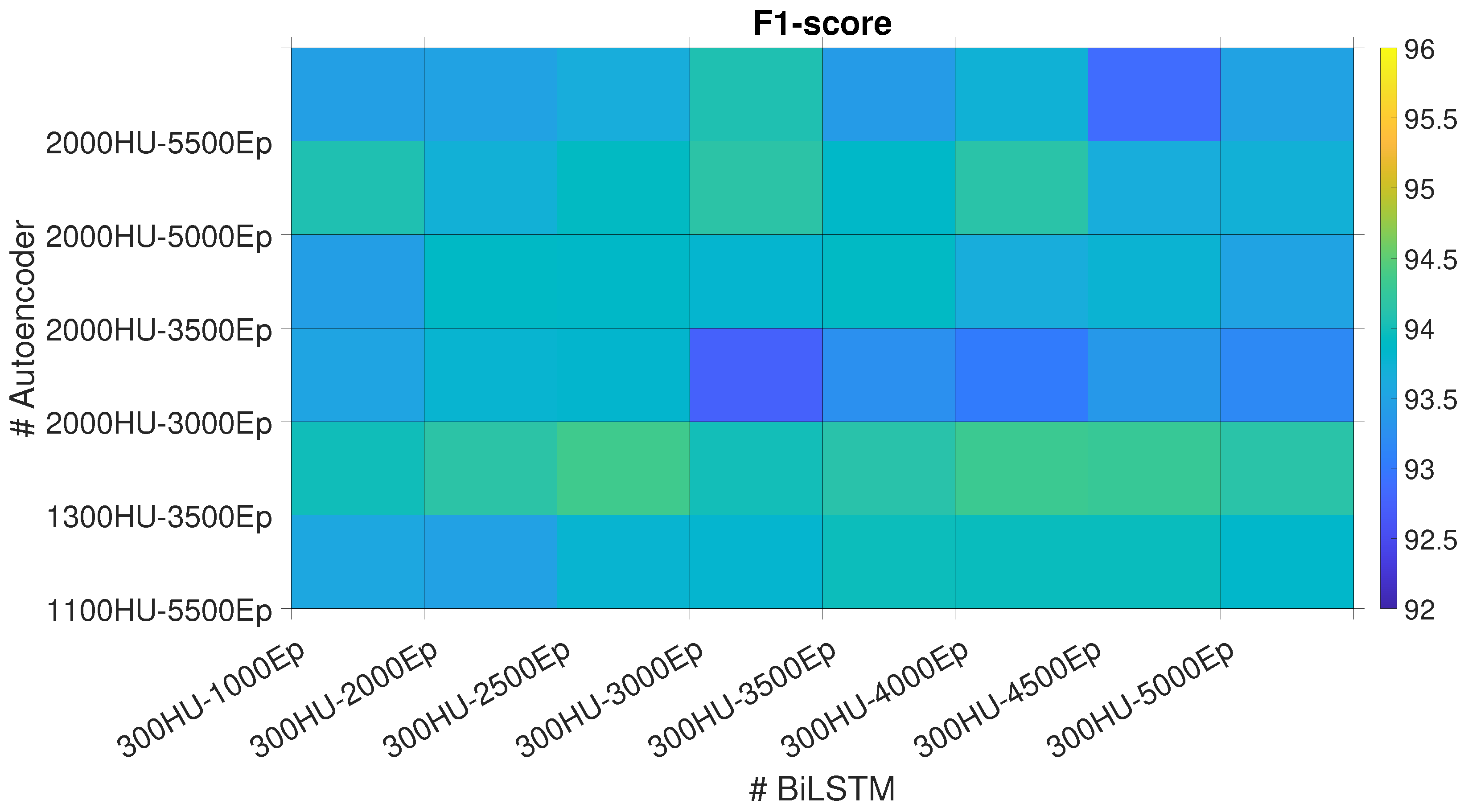

4.1.3. Recurrent Sp-DAE

4.1.4. RCNN

4.2. Network architectures comparison

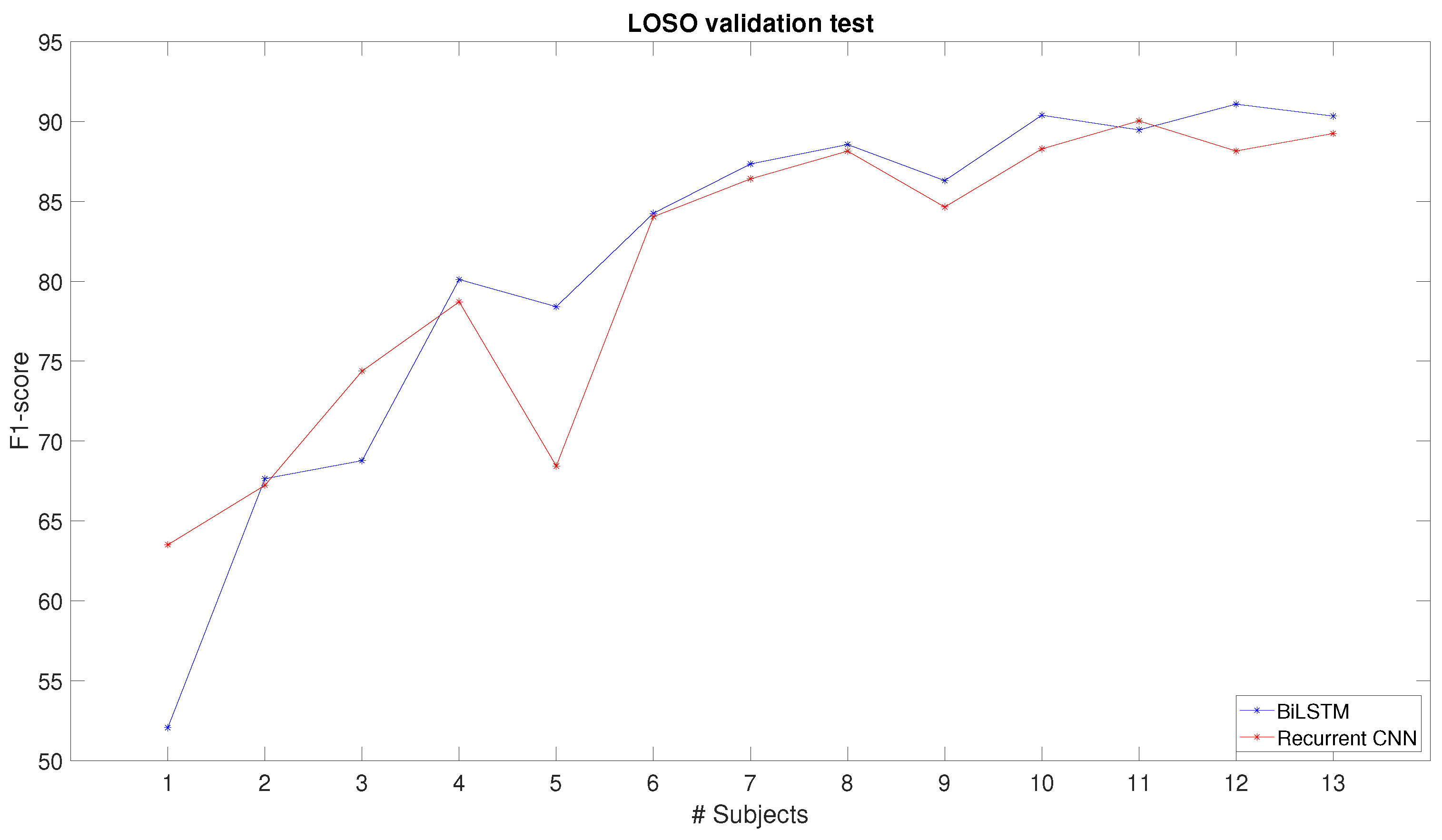

4.3. Performance of the selected networks with LOSO validation

4.4. Comparison of the selected networks with SoA

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

References

- Singh, D.; Merdivan, E.; Psychoula, I.; Kropf, J.; Hanke, S.; Geist, M.; Holzinger, A. Human activity recognition using recurrent neural networks. In Proceedings of the CD-MAKE. Springer; 2017; pp. 267–274. [Google Scholar]

- Schrader, L.; Toro, A.V.; Konietzny, S.; Rüping, S.; Schäpers, B.; Steinböck, M.; Krewer, C.; Müller, F.; Güttler, J.; Bock, T. Advanced sensing and human activity recognition in early intervention and rehabilitation of elderly people. Journal of Population Ageing 2020, 13, 139–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaisé, A.; Maurice, P.; Colas, F.; Ivaldi, S. Activity recognition for ergonomics assessment of industrial tasks with automatic feature selection. RA-L 2019, 4, 1132–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Villaseñor, L.; Ponce, H. A concise review on sensor signal acquisition and transformation applied to human activity recognition and human–robot interaction. IJDSN 2019, 15, 1550147719853987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, S.; Yazdi, P.G.; Humairi, A.A.; Alsami, M.; Rashdi, B.A.; Zakwani, Z.A.; Sheikaili, S.A. Design and fabrication of intelligent material handling system in modern manufacturing with industry 4.0 approaches. IRATJ 2018, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conforti, I.; Mileti, I.; Prete, Z.D.; Palermo, E. Measuring biomechanical risk in lifting load tasks through wearable system and machine-learning approach. Sensors 2020, 20, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, R. Manual material handling: A classification scheme. Procedia Technology 2016, 24, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zhang, D.; Yao, L.; Guo, B.; Yu, Z.; Liu, Y. Deep learning for sensor-based human activity recognition: Overview, challenges, and opportunities. CSUR 2021, 54, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nweke, H.F.; Teh, Y.W.; Al-Garadi, M.A.; Alo, U.R. Deep learning algorithms for human activity recognition using mobile and wearable sensor networks: State of the art and research challenges. Expert Systems with Applications 2018, 105, 233–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luzheng, B.; Genetu, F.A.; Cuntai, G. A review on EMG-based motor intention prediction of continuous human upper limb motion for human-robot collaboration. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2019, 51, 113–127. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, S.; Baek, Y.; Lee, J.; Eun, Y.; Son, S.H. Korean sign language recognition using EMG and IMU sensors based on group-dependent NN models. In Proceedings of the SSCI. IEEE; 2017; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Totah, D.; Ojeda, L.; Johnson, D.; Gates, D.; Provost, E.M.; Barton, K. Low-back electromyography (EMG) data-driven load classification for dynamic lifting tasks. PloS one 2018, 13, e0192938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attal, F.; Mohammed, S.; Dedabrishvili, M.; Chamroukhi, F.; Oukhellou, L.; Amirat, Y. Physical human activity recognition using wearable sensors. Sensors 2015, 15, 31314–31338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulling, A.; Blanke, U.; Schiele, B. A tutorial on human activity recognition using body-worn inertial sensors. CSUR 2014, 46, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Hao, S.; Peng, X.; Hu, L. Deep learning for sensor-based activity recognition: A survey. Pattern recognition letters 2019, 119, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dentamaro, V.; Gattulli, V.; Impedovo, D.; Manca, F. Human activity recognition with smartphone-integrated sensors: A survey. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 246, 123143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmessabih, T.; Slama, R.; Havard, V.; Baudry, D. Online human motion analysis in industrial context: A review. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2024, 131, 107850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trkov, M.; Stevenson, D.T.; Merryweather, A.S. Classifying hazardous movements and loads during manual materials handling using accelerometers and instrumented insoles. Applied ergonomics 2022, 101, 103693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syed, A.S.; Syed, Z.S.; Shah, M.; Saddar, S. Using wearable sensors for human activity recognition in logistics: A comparison of different feature sets and machine learning algorithms. IJACSA 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassani, G.; Filippeschi, A.; Avizzano, C.A. A Dataset of Human Motion and Muscular Activities in Manual Material Handling Tasks for Biomechanical and Ergonomic Analyses. Sensors Journal 2021, 21, 24731–24739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez, F.J.; Roggen, D. Deep convolutional and lstm recurrent neural networks for multimodal wearable activity recognition. Sensors 2016, 16, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, N.; Morales, J.; Maekawa, T.; Hara, T. Openpack: A large-scale dataset for recognizing packaging works in iot-enabled logistic environments. In Proceedings of the PerCom. IEEE; 2024; pp. 90–97. [Google Scholar]

- Hochreiter, S. The vanishing gradient problem during learning recurrent neural nets and problem solutions. IJUFKS 1998, 6, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; van Merrienboer, B.; Gulcehre, C.; Bahdanau, D.; Bougares, F.; Schwenk, H.; Bengio, Y. Learning phrase representations using RNN encoder-decoder for statistical machine translation. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1406.1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greff, K.; Srivastava, R.K.; Koutník, J.; Steunebrink, B.; Schmidhuber, J. LSTM: A search space odyssey. IEEE transactions on neural networks and learning systems 2016, 28, 2222–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, M.; Paliwal, K.K. Bidirectional recurrent neural networks. IEEE transactions on Signal Processing 1997, 45, 2673–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murad, A.; Pyun, J. Deep recurrent neural networks for human activity recognition. Sensors 2017, 17, 2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porta, M.; Kim, S.; Pau, M.; Nussbaum, M.A. Classifying diverse manual material handling tasks using a single wearable sensor. Applied Ergonomics 2021, 93, 103386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab, A.; Schmidt, A.; Aufderheide, D. Human Activity Recognition Using Sensor Fusion and Deep Learning for Ergonomics in Logistics Applications. In Proceedings of the IoTaIS. IEEE; 2023; pp. 254–260. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L. Recognition of human activities using continuous autoencoders with wearable sensors. Sensors 2016, 16, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almaslukh, B.; AlMuhtadi, J.; Artoli, A. An effective deep autoencoder approach for online smartphone-based human activity recognition. IJCSNS 2017, 17, 160–165. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent, P.; Larochelle, H.; Bengio, Y.; Manzagol, P.A. Extracting and composing robust features with denoising autoencoders. In Proceedings of the ICML; 2008; pp. 1096–1103. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, F.; Khoshelham, K.; Valaee, S.; Shang, J.; Zhang, R. Locomotion activity recognition using stacked denoising autoencoders. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2018, 5, 2085–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Nooruddin, S.; Karray, F.; Muhammad, G. Human activity recognition using tools of convolutional neural networks: A state of the art review, data sets, challenges, and future prospects. Computers in biology and medicine 2022, 149, 106060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemann, F.; Lüdtke, S.; Bartelt, C.; Hompel, M.T. Context-aware human activity recognition in industrial processes. Sensors 2021, 22, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, A.S.; Syed, Z.S.; Memon, A.K. Continuous human activity recognition in logistics from inertial sensor data using temporal convolutions in CNN. IJACSA 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, K.; Huang, J.; Wang, H. LSTM-CNN architecture for human activity recognition. Access 2020, 8, 56855–56866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.L.; Wang, J.H.; Lo, C.M.; Jiang, Z. Human Activity Recognition via Attention-Augmented TCN-BiGRU Fusion. Sensors 2025, 25, 5765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Luo, H.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, F.; Ye, L.; Zhang, Y. A human activity recognition algorithm based on stacking denoising autoencoder and lightGBM. Sensors 2019, 19, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shi, D.; Ding, B.; Liu, D. Unsupervised feature learning for human activity recognition using smartphone sensors. In Proceedings of the MIKE. Springer; 2014; pp. 99–107. [Google Scholar]

- Bassani, G.; Filippeschi, A.; Avizzano, C.A. A wearable device to assist the evaluation of workers health based on inertial and sEMG signals. In Proceedings of the MED. IEEE; 2021; pp. 669–674. [Google Scholar]

- Losey, D.P.; McDonald, C.G.; Battaglia, E.; O’Malley, M.K. A review of intent detection, arbitration, and communication aspects of shared control for physical human–robot interaction. AMR 2018, 70, 010804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Shahabi, F.; Xia, S.; Deng, Y.; Alshurafa, N. Deep learning in human activity recognition with wearable sensors: A review on advances. Sensors 2022, 22, 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, Y.; Plötz, T. Ensembles of deep lstm learners for activity recognition using wearables. IMWUT 2017, 1, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buda, M.; Maki, A.; Mazurowski, M.A. A systematic study of the class imbalance problem in convolutional neural networks. Neural Networks 2018, 106, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. NeurIPS 2012, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzeszick, R.; Lenk, J.M.; Rueda, F.M.; Fink, G.A.; Feldhorst, S.; Hompel, M.T. Deep neural network based human activity recognition for the order picking process. In Proceedings of the iWOAR; 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P.; Srivallapanondh, S.; Spinnler, B.; Napoli, A.; Costa, N.; Prilepsky, J.E.; Turitsyn, S.K. Computational complexity optimization of neural network-based equalizers in digital signal processing: a comprehensive approach. JLT 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Lin, S.; Wang, N.; Dai, G.; Xie, Y.; Zhou, J. TSE-CNN: A two-stage end-to-end CNN for human activity recognition. JBHI 2019, 24, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales, J.; Yoshimura, N.; Xia, Q.; Wada, A.; Namioka, Y.; Maekawa, T. Acceleration-based human activity recognition of packaging tasks using motif-guided attention networks. In Proceedings of the PerCom. IEEE; 2022; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kuschan, J.; Filaretov, H.; Krüger, J. Inertial measurement unit based human action recognition dataset for cyclic overhead car assembly and disassembly. In Proceedings of the INDIN. IEEE; 2022; pp. 469–476. [Google Scholar]

- Giannini, P.; Bassani, G.; Avizzano, C.A.; Filippeschi, A. Wearable sensor network for biomechanical overload assessment in manual material handling. Sensors 2020, 20, 3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefana, E.; Marciano, F.; Rossi, D.; Cocca, P.; Tomasoni, G. Wearable devices for ergonomics: A systematic literature review. Sensors 2021, 21, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Hyperparameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Input size | 10 |

| Optimizer | Adam |

| Maximum epochs | 100, 300, 500, 700, 1000, 1500, 2000, 2500, 3000, 3500 |

| Hidden units | 100, 300, 500, 700, 900 |

| Batch size | 128 |

| Initial Learning rate | |

| Learning rate drop factor | |

| Learning rate drop period | 10 |

| L2 regularization | |

| Loss function | Cross-entropy loss |

| Hyperparameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Input size | 10 |

| Maximum epochs | 100, 300, 500, 700, 1000, 1300, 1500, 2000, 2500, 3000, 3500, 4000, 4500, 5000, 5500, 6000, 6500 |

| Hidden units | 100, 300, 500, 700, 900, 1100, 1300, 2000, 2500, 3000, 3500 |

| Training algorithm | Conjugate gradient descent |

| Sparsity Regularization | 1 |

| Sparsity proportion | |

| L2 regularization | |

| Transfer function | log-sigmoid |

| Loss function | Sparse mse |

| Hyperparameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Input size | 10x240 |

| Filter size | 3x3 |

| Filter dimension | 32 |

| Padding | 0 |

| 1° CNN layer stride | 1x1 |

| 2° CNN layer stride | 1x4 |

| 1° CNN layer dilation factor | 1x1 |

| 2° CNN layer dilation factor | 2x2 |

| Maximum epochs | 100, 300, 500, 700, 1000 |

| Hidden units | 100, 300, 500, 700, 900 |

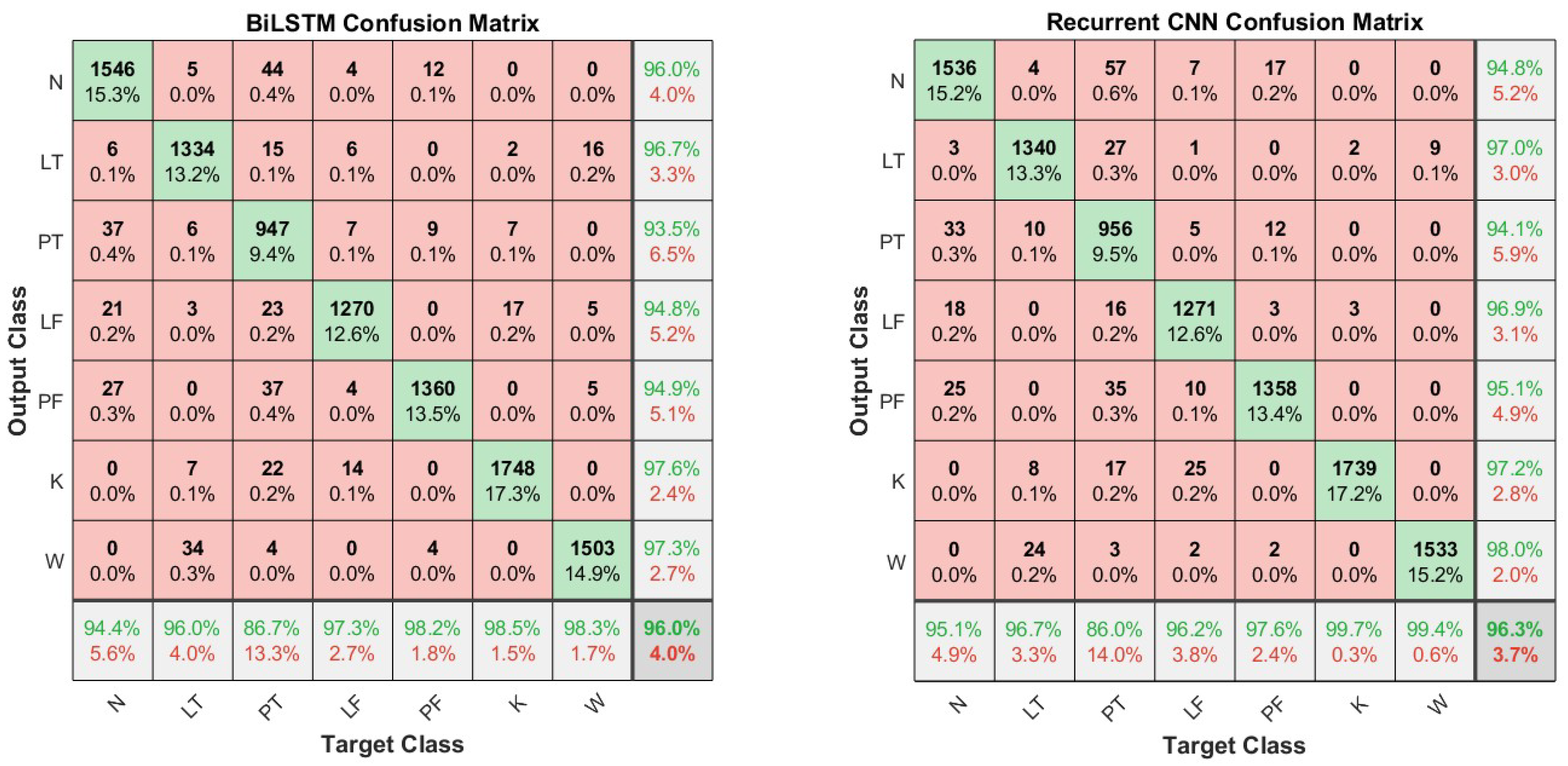

| Action | BiLSTM | RCNN |

|---|---|---|

| N-pose (N) | 89.1% | 90.1% |

| Lifting from the Table (LT) | 94.5% | 92.4% |

| Placing on the Table (PT) | 84% | 85.1% |

| Lifting from the Floor (LF) | 90.3% | 88.7% |

| Placing on the Floor (PF) | 88.8% | 86.7% |

| Keeping lifted (K) | 92.3% | 91.4% |

| Carrying (W) | 93.4% | 90.2% |

| Neural network | F1-score 70-30 split | F1-score LOSO | MAC | MA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BiLSTM | 95.7% | 90.3% | 1492200 | 1532400 |

| RCNN | 95.9% | 89.2% | 2724028 | 5448056 |

| DeepConvLSTM | 95.2% | 90.3% | 327027584 | 543762176 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).