Submitted:

24 September 2025

Posted:

26 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

3.1. Robotics and Surgery

3.2. AI in Surgical Robotics

3.3. Actuators in Minimally Invasive Surgery

2. Background

3. Methods

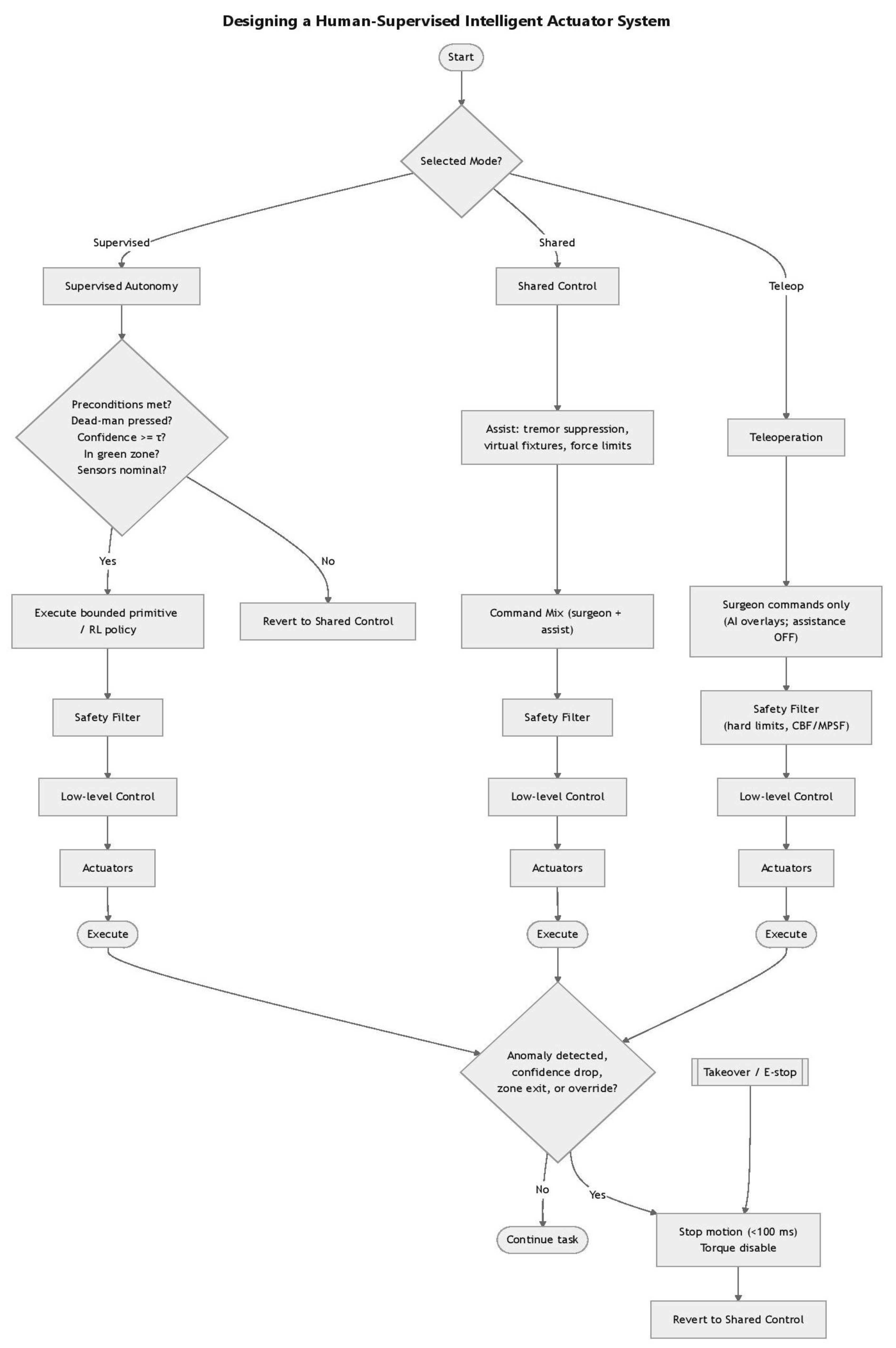

| Algorithm 1: Human-Supervised Intelligent Surgical Actuator System |

| Input: • Selected mode ∈ {Teleoperation, Shared Control, Supervised Autonomy} • Surgeon commands • Sensor feedback (force, position, safety signals) • System confidence estimate (τ threshold) • Dead-man switch state Output: • Safe execution of motion commands through actuators • Possible reversion to Shared Control or system stop on anomaly 1: function SurgicalControl(Mode, SurgeonCommands, Sensors) 2: switch Mode do 3: case Teleoperation: 4: Commands ← SurgeonCommands 5: Commands ← SafetyFilter(Commands) 6: Actuators ← LowLevelControl(Commands) 7: Execute(Actuators) 8: 9: case Shared Control: 10: Assist ← Assistance(SurgeonCommands) 11: Commands ← CommandMix(SurgeonCommands, Assist) 12: Commands ← SafetyFilter(Commands) 13: Actuators ← LowLevelControl(Commands) 14: Execute(Actuators) 15: 16: case Supervised Autonomy: 17: if not PreconditionsMet(Sensors) then 18: return SurgicalControl(Shared, SurgeonCommands, Sensors) 19: end if 20: Commands ← ExecutePolicy(Sensors) 21: Commands ← SafetyFilter(Commands) 22: Actuators ← LowLevelControl(Commands) 23: Execute(Actuators) 24: end switch 25: 26: while TaskNotComplete do 27: if AnomalyDetected(Sensors) or OverrideDetected() then 28: StopMotion(<100 ms) 29: DisableTorque() 30: return SurgicalControl(Shared, SurgeonCommands, Sensors) 31: end if 32: end while 33: end function 34: 35: function EStop() 36: StopMotion(<100 ms) 37: DisableTorque() 38: return SurgicalControl(Shared, SurgeonCommands, Sensors) 39: end function 40: function Assistance(SurgeonCommands) 41: // Apply tremor suppression, virtual fixtures, and force limits 42: return AssistedCommands 43: end function 44: 45: function CommandMix(SurgeonCommands, Assist) 46: // Combine raw surgeon input with assistive corrections 47: return MixedCommands 48: end function 49: 50: function SafetyFilter(Commands) 51: // Enforce safety constraints (e.g., hard limits, CBF, MPSF) 52: return SafeCommands 53: end function 54: 55: function LowLevelControl(Commands) 56: // Convert commands into actuator-level signals 57: return ActuatorSignals 58: end function 59: 60: function Execute(Actuators) 61: // Send actuator signals for motion execution 62: end function 63: 64: function PreconditionsMet(Sensors) 65: if DeadManPressed(Sensors) = false then return false 66: if Confidence(Sensors) < Threshold then return false 67: if not InGreenZone(Sensors) then return false 68: if not SensorsNominal(Sensors) then return false 69: return true 70: end function 71: 72: function ExecutePolicy(Sensors) 73: // Choose bounded primitive or learned RL policy 74: return PolicyCommands 75: end function 76: 77: function AnomalyDetected(Sensors) 78: // Check for anomaly, confidence drop, or zone exit 79: return Boolean 80: end function 81: 82: function OverrideDetected() 83: // Detect explicit surgeon override 84: return Boolean 85: end function |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

References

- Wah, J.N.K. Revolutionizing Surgery: AI and Robotics for Precision, Risk Reduction, and Innovation. J. Robot. Surg. 2025, 19, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairag, M.; Almahdi, R.H.; Siddiqi, A.A.; Alharthi, F.K.; Alqurashi, B.S.; Alzahrani, N.G.; Alsulami, A.; Alshehri, R. Robotic Revolution in Surgery: Diverse Applications Across Specialties and Future Prospects. Cureus 2024, 16, e52148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, R.; Khan, A. Assessing the Practicality of Designing a Comprehensive Intelligent Conversation Agent to Assist in Dementia Care. In Kim, J. (Ed.) Proceedings of the 17th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025), Volume 2: HEALTHINF, Rome, Italy, 16–18 February 2025; SCITEPRESS: Setúbal, Portugal, 2025; pp. 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, R.; Khan, A. Machine Learning-Based Clinical Decision Support Systems in Dementia Care In: Kim, J. (Ed.) Proceedings of the 17th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025), Volume 2: HEALTHINF, Rome, Italy, 16–18 February 2025; SCITEPRESS: Setúbal, Portugal, 2025; pp. 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wah, J.N.K. The rise of robotics and AI-assisted surgery in modern healthcare. J. Robot. Surg. 2025, 19, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K.; Gharde, P.; Tayade, H.; Patil, M.; Reddy, L.S.; Surya, D. Advancements in robotic surgery: A comprehensive overview of current utilizations and upcoming frontiers. Cureus 2023, 15, e50415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergenç, M. Artificial intelligence in surgical practice: Truth beyond fancy covering. Turk. J. Surg. 2025, 41, 118–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.I.; Spooner, B.; Isherwood, J.; Lane, M.; Orrock, E.; Dennison, A. A Systematic Review of the Barriers to the Implementation of Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare. Cureus 2023, 15, e46454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, R.R.; Khan, A. Modernizing Medicine Through a Proof of Concept that Studies the Intersection of Robotic Exoskeletons, Computational Capacities and Dementia Care. In Alsadoon, A.; Shenavarmasouleh, F., Amirian, S., Ghareh Mohammadi, F., Arabnia, H.R., Eds.; Deligiannidis, L. (Eds.) Health Informatics and Medical Systems and Biomedical Engineering. CSCE 2024. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol. 2259; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deo, N.; Anjankar, A. Artificial Intelligence With Robotics in Healthcare: A Narrative Review of Its Viability in India. Cureus 2023, 15, e39416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maleki Varnosfaderani, S.; Forouzanfar, M. The Role of AI in Hospitals and Clinics: Transforming Healthcare in the 21st Century. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, X.; Sang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Wang, Y.; Shi, B.; Fan, Y. Evolution of surgical robot systems enhanced by artificial intelligence: A review. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2024, 6, 2300268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, E.I.; Brand, T.C.; LaPorta, A.; Marescaux, J.; Satava, R.M. Origins of robotic surgery: From skepticism to standard of care. JSLS 2018, 22, e2018.00039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zirafa, C.C.; Romano, G.; Key, T.H.; Davini, F.; Melfi, F. The evolution of robotic thoracic surgery. Ann. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2019, 8, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basic Medical Key. The History of Robotic Surgery. Available online: https://basicmedicalkey.com/the-history-of-robotic-surgery/ (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Smithsonian Magazine. The Past, Present, and Future of Robotic Surgery. Available online: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/the-past-present-and-future-of-robotic-surgery-180980763/ (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Pugin, F.; Bucher, P.; Morel, P. History of robotic surgery: From AESOP® and ZEUS® to da Vinci®. J. Visc. Surg. 2011, 148, e3–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamura, H.; Mizuno, Y.; Ohwaki, A.; Ito, M.; Nishio, E.; Nishizawa, H. Comparison of single-port robotic surgery using the Da Vinci SP surgical system and single-port laparoscopic surgery for benign indications. Gynecol. Minim. Invasive Ther. 2025, 14, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manabe, Y.; Murai, T.; Ogino, H.; Tamura, T.; Iwabuchi, M.; Mori, Y.; Iwata, H.; Suzuki, H.; Shibamoto, Y. CyberKnife Stereotactic Radiosurgery and Hypofractionated Stereotactic Radiotherapy as First-Line Treatments for Imaging-Diagnosed Intracranial Meningiomas. Neurol. Med.-Chir. 2017, 57, 627–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maris, B.; Tenga, C.; Vicario, R.; Palladino, L.; Murr, N.; De Piccoli, M.; Calanca, A.; Puliatti, S.; Micali, S.; Tafuri, A.; Fiorini, P. Toward Autonomous Robotic Prostate Biopsy: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2021, 16, 1393–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faulkner, J.; Arora, A.; McCulloch, P.; Robertson, S.; Rovira, A.; Ourselin, S.; Jeannon, J.P. Prospective development study of the Versius Surgical System for use in transoral robotic surgery: An IDEAL stage 1/2a first in human and initial case series experience. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2024, 281, 2667–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Badre, A.; Alambeigi, F.; Tavakoli, M. Robotic Systems and Navigation Techniques in Orthopedics: A Historical Review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ureel, M.; Augello, M.; Holzinger, D.; Wilken, T.; Berg, B.I.; Zeilhofer, H.F.; Millesi, G.; Juergens, P.; Mueller, A.A. Cold ablation robot-guided laser osteotome (CARLO®): From bench to bedside. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arezzo, A. Endoluminal robotics. Surgery 2024, 176, 1542–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulla, J.; Small, A.; Kaplan-Marans, E.; Palese, M. Magnetic-assisted robotic and laparoscopic renal surgery: Initial clinical experience with the Levita Magnetic Surgical System. J. Endourol. 2020, 34, 1242–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Wang, S.; Shen, Y.; Hu, J. The Application of Augmented Reality Technology in Perioperative Visual Guidance: Technological Advances and Innovation Challenges. Sensors 2024, 24, 7363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Dai, Y.; Zeng, Y. Intelligent robot-assisted fracture reduction system for the treatment of unstable pelvic fractures. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2024, 19, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, G.; Zhao, B.; Xie, D.; Du, H.; Duan, X.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L. Advances of surgical robotics: Image-guided classification and application. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2024, 11, nwae186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, X.; Song, Y.; Liu, D.; Wang, Y.; Guo, X.; Wu, B.; Zhang, N. Motion planning and control of active robot in orthopedic surgery by CDMP-based imitation learning and constrained optimization. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, S. Robotic surgery. J. Oral Biol. Craniofac. Res. 2013, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, P.; Stramiello, J.; Funk, E.K.; Richter, F.; Yip, M.C.; Orosco, R.K. Remote telesurgery in humans: A systematic review. Surg. Endosc. 2022, 36, 2771–2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Baishya, N.J.; Bhattacharya, B. A review on tele-manipulators for remote diagnostic procedures and surgery. CSI Trans. ICT 2023, 11, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fracczak, L.; Szaniewski, M.; Podsedkowski, L. Share control of surgery robot master manipulator guiding tool along the standard path. Int. J. Med. Robot. Comput. Assist. Surg. 2019, 15, e1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, S.K.; Sharma, V. Robotics and ophthalmology: Are we there yet? Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 67, 988–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walgrave, S.; Oussedik, S. Comparative assessment of current robotic-assisted systems in primary total knee arthroplasty. Bone Jt. Open 2023, 4, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liow, M.H.L.; Chin, P.L.; Pang, H.N.; Tay, D.K.; Yeo, S.J. THINK surgical TSolution-One® (Robodoc) total knee arthroplasty. SICOT J. 2017, 3, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.Z.; Liu, D.F.; Yang, A.C.; Zhang, K.; Meng, F.G.; Zhang, J.G.; Liu, H.G. Application of the robot-assisted implantation in deep brain stimulation. Front. Neurorobot. 2022, 16, 996685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeganathan, J.R.; Jegasothy, R.; Sia, W.T. Minimally invasive surgery: A historical and legal perspective on technological transformation. J. Robot. Surg. 2025, 19, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, P.; Sikander, S.; Kulkarni, P. Recent advances in robot-assisted surgical systems. Biomed. Eng. Adv. 2023, 6, 100109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thamm, O.C.; Eschborn, J.; Schäfer, R.C.; Schmidt, J. Advances in modern microsurgery. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, P.J. Stereotactic surgery: What is past is prologue. Neurosurgery 2000, 46, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Li, H.; Pu, T.; Yang, L. Microsurgery robots: Applications, design, and development. Sensors 2023, 23, 8503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malzone, G.; Menichini, G.; Innocenti, M.; Ballestín, A. Microsurgical robotic system enables the performance of microvascular anastomoses: A randomized in vivo preclinical trial. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iftikhar, M.; Saqib, M.; Zareen, M.; Mumtaz, H. Artificial intelligence: Revolutionizing robotic surgery: Review. Ann. Med. Surg. 2024, 86, 5401–5409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.; Vasisht, S.; Hashimoto, D.A. Artificial Intelligence in Surgery: What Is Needed for Ongoing Innovation. Surg. (Oxford) 2025, 43, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, R.R.; Saxena, R. Applying Graph Neural Networks in Pharmacology. TechRxiv 2024, 25 June. [CrossRef]

- Schmidgall, S.; Opfermann, J.D.; Kim, J.W.; Krieger, A. Will Your Next Surgeon Be a Robot? Autonomy and AI in Robotic Surgery. Sci. Robot. 2025, 10, eadt0187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, J.E.; Ghaffar, U.; Ma, R.; Hung, A.J. Clinical applications of artificial intelligence in robotic surgery. J. Robot. Surg. 2024, 18, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habuza, T.; Navaz, A.N.; Hashim, F.; Alnajjar, F.; Zaki, N.; Serhani, M.A.; Statsenko, Y. AI applications in robotics, diagnostic image analysis and precision medicine: Current limitations, future trends, guidelines on CAD systems for medicine. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2021, 24, 100596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, R.R.; Nieters, E.; Mamudu, I. Pokémondium: A Machine Learning Approach to Detecting Images of Pokémon. TechRxiv 2025, 27 June. [CrossRef]

- Saxena, R.R. AI-Driven Forensic Image Enhancement. TechRxiv, 08 May. [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.X.; Fiocco, D.; Caneva, T.; Yiapanis, P.; Orgill, D.P. Current and Future Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Surgery: Implications for Clinical Practice and Research. Front. Surg. 2024, 11, 1393898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Liang, H.; et al. Digitalization of surgical features improves surgical accuracy via surgeon guidance and robotization. NPJ Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knez, D.; Nahle, I.S.; Vrtovec, T.; Parent, S.; Kadoury, S. Computer-assisted pedicle screw trajectory planning using CT-inferred bone density: A demonstration against surgical outcomes. Med. Phys. 2019, 46, 3543–3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shadid, O.; Seth, I.; Cuomo, R.; Rozen, W.M.; Marcaccini, G. Artificial Intelligence in Microsurgical Planning: A Five-Year Leap in Clinical Translation. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Gong, Y.; Hannaford, B.; Seibel, E.J. Path planning for semi-automated simulated robotic neurosurgery. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Hamburg, Germany, 28 September–2 October 2015; pp. 2639–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, F.; Durr, N.J. Deep learning and conditional random fields-based depth estimation and topographical reconstruction from conventional endoscopy. Med. Image Anal. 2018, 48, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oettl, F.C.; Zsidai, B.; Oeding, J.F.; Samuelsson, K. Artificial intelligence and musculoskeletal surgical applications. HSS J. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Premarket Notification 510(k). Available online: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/premarket-submissions-selecting-and-preparing-correct-submission/premarket-notification-510k (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- European Commission. CE marking – obtaining the certificate, EU requirements. Your Europe. Available online: https://europa.eu/youreurope/business/product-requirements/labels-markings/ce-marking/index_en.htm (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Górriz, J.M.; Álvarez-Illán, I.; Álvarez-Marquina, A.; Arco, J.E.; Atzmueller, M.; Ballarini, F.; Barakova, E.; Bologna, G.; Bonomini, P.; Castellanos-Dominguez, G.; et al. Computational Approaches to Explainable Artificial Intelligence: Advances in Theory, Applications and Trends. Inf. Fus. 2023, 100, 101945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, M.; Gharde, P.; Reddy, K.; Nayak, K. Comparative Analysis of Laparoscopic Versus Open Procedures in Specific General Surgical Interventions. Cureus 2024, 16, e54433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepolina, F.; Razzoli, R. Review of Robotic Surgery Platforms and End Effectors. J. Robot. Surg. 2024, 18, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.H.; Mani, K.; Panigrahi, B.; Hajari, S.; Chen, C.Y. A Shape Memory Alloy-Based Miniaturized Actuator for Catheter Interventions. Cardiovasc. Eng. Technol. 2018, 9, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Sun, L.; Liu, Z.; Sun, N.; Zhang, J. Actuators and Variable Stiffness of Flexible Surgical Actuators: A Review. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2025, 390, 116588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deivayanai, V.C.; Swaminaathanan, P.; Vickram, A.S.; Saravanan, A.; Bibi, S.; Aggarwal, N.; Kumar, V.; Alhadrami, A.H.; Mohammedsaleh, Z.M.; Altalhi, R.; et al. Transforming Healthcare: The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Diagnostics, Pharmaceuticals, and Ethical Considerations – A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Surg. 2025, 111, 4666–4693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Zhou, S.; Hong, C.; Xiao, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, X.; Zeng, L.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, X. Piezo-Actuated Smart Mechatronic Systems for Extreme Scenarios. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2025, 7, 022003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, T.; Vyas, D. Robotic Surgery: Applications. Am. J. Robot. Surg. 2014, 1, 1–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batailler, C.; Shatrov, J.; Sappey-Marinier, E.; Servien, E.; Parratte, S.; Lustig, S. Artificial Intelligence in Knee Arthroplasty: Current Concept of the Available Clinical Applications. Arthroplasty 2022, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wah, J.N.K. The Robotic Revolution in Cardiac Surgery. J. Robot. Surg. 2025, 19, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brzeski, A.; Blokus, A.; Cychnerski, J. An Overview of Image Analysis Techniques in Endoscopic Bleeding Detection. Int. J. Innov. Res. Comput. Commun. Eng. 2013, 1, 1350–1357. [Google Scholar]

- Rahbar, M.D.; Reisner, L.; Ying, H.; Pandya, A. An Entropy-Based Approach to Detect and Localize Intraoperative Bleeding During Minimally Invasive Surgery. Int. J. Med. Robot. Comput. Assist. Surg. 2020, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, V.; Misuriello, F.; Piras, E.; Nesci, C.; Chiarello, M.M.; Brisinda, G. Ethical Considerations on the Role of Artificial Intelligence in Defining Futility in Emergency Surgery. Int. J. Surg. 2025, 111, 3178–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemzadeh, H.; Raman, J.; Leveson, N.; Kalbarczyk, Z.; Iyer, R.K. Adverse Events in Robotic Surgery: A Retrospective Study of 14 Years of FDA Data. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonnell, C.; Devine, M.; Kavanagh, D. The General Public’s Perception of Robotic Surgery – A Scoping Review. Surgeon 2025, 23, e49–e62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ida, Y.; Sugita, N.; Ueta, T.; et al. Microsurgical Robotic System for Vitreoretinal Surgery. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2012, 7, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parekattil, S.J.; Gudeloglu, A. Robotic Assisted Andrological Surgery. Asian J. Androl. 2013, 15, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilvawala, G.; Wen, J.; Santiago-Dieppa, D.; Yan, B.; Pannell, J.; Khalessi, A.; Norbash, A.; Friend, J. Soft Robotic Steerable Microcatheter for the Endovascular Treatment of Cerebral Disorders. Sci. Robot. 2021, 6, eabf0601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza, T.; Bokhari, S.F.H. Partnering With Technology: Advancing Laparoscopy With Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning. Cureus 2024, 16, e56076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, Z.; Chauhan, V.; Devi, K.; Patil, S. Artificial Intelligence, the Digital Surgeon: Unravelling Its Emerging Footprint in Healthcare – The Narrative Review. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2024, 17, 4011–4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feizi, N.; Tavakoli, M.; Patel, R.V.; Atashzar, S.F. Robotics and AI for Teleoperation, Tele-Assessment, and Tele-Training for Surgery in the Era of COVID-19: Existing Challenges, and Future Vision. Front. Robot. AI 2021, 8, 610677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.K.; Kakakhel, M.M.; Ashraf, M.F.; Shahab, M.; Ahmad, F.; Luqman, F.; Ahmad, M.; Mohammed Nour, A.; Varrassi, G.; Kinger, S. Innovative Approaches to Safe Surgery: A Narrative Synthesis of Best Practices. Cureus 2023, 15, e49723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elendu, C.; Amaechi, D.C.; Elendu, T.C.; Jingwa, K.A.; Okoye, O.K.; Okah, M.J.; Ladele, J.A.; Farah, A.H.; Alimi, H.A. Ethical Implications of AI and Robotics in Healthcare: A Review. Med. (Baltimore) 2023, 102, e36671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.S.; Wu, Y.; Zheng, B. A Review of Cognitive Support Systems in the Operating Room. Surg. Innov. 2024, 31, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquer, A.; Ducarroz, S.; Lifante, J.C.; Skinner, S.; Poncet, G.; Duclos, A. Operating Room Organization and Surgical Performance: A Systematic Review. Patient Saf. Surg. 2024, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heider, S.; Schoenfelder, J.; Koperna, T.; Brunner, J.O. Balancing Control and Autonomy in Master Surgery Scheduling: Benefits of ICU Quotas for Recovery Units. Health Care Manag. Sci. 2022, 25, 311–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research. J. Am. Coll. Dent. 2014, 81, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, E.R.; Halter, R.; Paulsen, K.D.; Pogue, B.W.; Elliott, J.; LaRochelle, E.; Ruiz, A.; Jiang, S.; Streeter, S.S.; Samkoe, K.S.; et al. Onward to Better Surgery – The Critical Need for Improved Ex Vivo Testing and Training Methods. Proceedings of SPIE--The International Society for Optical Engineering, San Francisco, CA, USA, 2024; 12825, 1282506., 3–7 February 2024; SPIE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Kyeremeh, J.; Luo, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, K.; Cao, F.; Asciak, L.; Kazakidi, A.; Stewart, G.D.; Shu, W. A Numerical Simulation Study of Soft Tissue Resection for Low-Damage Precision Cancer Surgery. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2025, 270, 108937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A. Reinforcement Learning for Robotic-Assisted Surgeries: Optimizing Procedural Outcomes and Minimizing Post-Operative Complications. Int. J. Res. Publ. Rev. 2025, 6, 5669–5684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, R.R. Applications of Natural Language Processing in the Domain of Mental Health. TechRxiv, 28 October. [CrossRef]

- Javed, H.; El-Sappagh, S.; Abuhmed, T. Robustness in Deep Learning Models for Medical Diagnostics: Security and Adversarial Challenges Towards Robust AI Applications. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, R.R. Beyond Flashcards: Designing an Intelligent Assistant for USMLE Mastery and Virtual Tutoring in Medical Education (A Study on Harnessing Chatbot Technology for Personalized Step 1 Prep). arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.10540. https://arxiv.org/abs/2409, 10540. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena, R.R. Intelligent Approaches to Predictive Analytics in Occupational Health and Safety in India. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.16038. https://arxiv.org/abs/2412, 16038. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, A.; Cardoso, S.A.; Suyambu, J.; Abdus Saboor, H.; Cardoso, R.P.; Husnain, A.; Isaac, N.V.; Backing, H.; Mehmood, D.; Mehmood, M.; et al. Future of Artificial Intelligence in Surgery: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e51631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindegger, D.J.; Wawrzynski, J.; Saleh, G.M. Evolution and Applications of Artificial Intelligence to Cataract Surgery. Ophthalmol. Sci. 2022, 2, 100164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | Techniques | Examples | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preprocessing | Noise reduction | Gaussian Blur, Median filtering | Limited adaptability; cannot handle diverse noise patterns in clinical imagery |

| Contrast enhancement | Histogram equalization | Global adjustment lacks contextual awareness | |

| Color space conversion | RGB converted to Grayscale or HSV | Reduces dimensional richness; may lose clinically relevant details | |

| Segmentation & Localization | Region-based segmentation | Region growing, watershed methods | Sensitive to noise and initialization; poor generalization |

| Thresholding | Otsu’s method | Performance drops with non-uniform illumination | |

| Edge detection | Canny operator, Sobel operator | Prone to spurious edges; limited robustness in complex anatomy | |

| Feature Extraction & Description | Shape and geometric features | Contours, boundary descriptors | Not invariant to scale, rotation, or deformation |

| Texture analysis | Gabor filters, Local Binary Patterns (LBP) | Sensitive to noise; limited capture of multi-scale texture | |

| Interest point detectors | SIFT, SURF | Computationally intensive; not scalable for real-time guidance | |

| Mathematical Morphology | Basic operations | Erosion, Dilation | Over-simplifies structures; loses context |

| Advanced transforms | Top-hat, Black-hat | Effective only in constrained scenarios; poor adaptability to variability | |

| General Limitation | — | — | Cannot capture richness and variability of clinical imagery; poor scalability for real-time, context-aware guidance |

| Dimension | Key Components | Implementation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Model Development | Explainability and Determinism | • Enhance interpretability |

| • Improve reproducibility | ||

| • Use transparent algorithms | ||

| Real-time Performance | • Model compression | |

| • Hardware-optimized deployment | ||

| • Graceful degradation mechanisms for uncertainty | ||

| Data Availability | Multi-institutional Collaboration | • Standardized annotation frameworks |

| • Dataset amalgamation | ||

| • Cross-institution partnerships | ||

| Privacy & Sharing | • Federated learning | |

| • Privacy-preserving strategies | ||

| • Secure data protocols | ||

| Synthetic Data | • High-fidelity surgical simulation | |

| • Generative models | ||

| • Pretraining capabilities | ||

| • Data augmentation for downstream tasks | ||

| Human-Robot Coordination | Interface Design | • Intuitive surgeon interfaces |

| • Advanced feedback modalities | ||

| Haptic Feedback | • Objectify subjective judgments | |

| • Quantify ambiguous intraoperative indicators | ||

| • Automate repetitive actions | ||

| Trust & Clinical Adoption | Safety Establishment | • Measurable safety improvements |

| • Transparent oversight mechanisms | ||

| Accountability | • Robust logging for auditability | |

| • Clearly defined autonomy boundaries | ||

| Control Mechanisms | • Reliable manual handover pathways | |

| • Balance between trust and autonomy | ||

| • Evolving safeguards |

| Actuator Type | Mechanism | Examples in MIS | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electromechanical Actuators | Electric motors (DC, stepper, servo) convert electrical energy into precise rotary/linear motion | Motor-driven robotic arms (e.g., da Vinci system) | High precision, controllability, reliable integration with control algorithms | Bulky compared to other actuators; limited miniaturization in very small instruments |

| Piezoelectric Actuators | Use piezoelectric crystals that deform under electric field to generate motion | Ultrasonic scalpels, micro-manipulators for ophthalmic and neurosurgery | Very high precision, fast response, compact size | Limited stroke length; requires high-frequency driving voltage |

| Pneumatic Actuators | Compressed air generates pressure to drive linear or rotary motion | Soft robotic grippers, inflatable balloons for dilation | Lightweight, compliant, safe for tissue interaction | Less precise, nonlinear behavior, dependency on external air supply |

| Hydraulic Actuators | Pressurized fluid drives pistons or chambers for motion | High-force surgical tools, orthopedic robots | High force density, smooth motion | Requires fluid lines; potential risk of leakage inside patient environment |

| SMA Actuators | Metals (e.g., NiTi alloys) change shape when heated and return when cooled | Steerable catheters, flexible endoscopic tools | Miniaturization potential, silent operation, compact integration | Slow response time, hysteresis, limited durability under cycling |

| Magnetic Actuators | External magnetic fields manipulate embedded magnets in instruments | Levita’s MARS (magnet-assisted surgical system), capsule endoscopy | Wireless control, minimally invasive manipulation, reduced mechanical linkages | Limited force at depth, requires careful control of magnetic fields |

| Electrostatic Actuators | Electric field generates force between charged plates/elements | Micro-electro-mechanical systems (MEMS) for microsurgery | High precision, scalable to micro-scale | Very low force output, sensitive to environmental conditions |

| Hybrid Actuation Systems | Combine two or more actuation methods for optimized performance | Pneumatic–hydraulic soft robots, piezoelectric–electromagnetic micromanipulators | Balance of precision, compliance, and force | Complexity in design and control integration |

| Layer | Description | AI Function | Human Oversight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Teleoperation | Surgeon drives robot manually | Annotation and measurement only | Full human control; no autonomy |

| Shared Control | Surgeon specifies goals; system assists in realizing the goals | Stabilizes motion, suppresses tremor, enforces virtual fixtures, modulates force/velocity | Surgeon remains decision-maker; real-time assistance |

| Supervised Autonomy | Short, bounded subtasks, such as following a cut path, maintaining safe force | Executes subtasks under confidence and safety gating | Surgeon holds the dead-man switch; instant reversion on pedal release, override, or detection of an anomaly |

| Component | Subsystem or Function | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Instrumentation & Actuation | Actuators | Miniature BLDC or piezo stacks with high reduction, backdrivable stages; integrated brakes for safe hold |

| Sensing | 6-axis force/torque at the wrist, motor currents, tip pose from stereo/endoscopic vision + EM tracker, temperature (cautery), and tissue impedance | |

| Virtual Fixtures | Software “guard rails” that constrain tool motion to safe corridors or planes (anatomy-aware) | |

| AI/ML Stack (Assistive) | Perception | Foundation vision model fine-tuned on endoscopic video to segment tools, tissue layers, and vessels; uncertainty quantification (MC-Dropout/Deep Ensembles) surfaces confidence to UI and safety layer |

| Control | Safety-filtered RL with CBF and Model Predictive Safety Filters rejecting unsafe actions; adaptive impedance control learning tissue stiffness online; learned skill primitives for short, bounded maneuvers (knot-pull, micro-cut) | |

| Anomaly Detection | Multimodal change-point detection on force + vision to flag slip, bleeding, or delamination; triggers slow-down, haptic cue, and visual alert; requires human confirmation | |

| Human Factors & UI | Visualization | Confidence-aware overlays: segmentation masks and planned trajectories fade with lower confidence; threshold surgeon-tunable; three-line status display (Mode, Safety, Confidence) |

| Haptics | Tremor suppression, force reflection, gentle repulsion near no-go zones | |

| Takeover Affordances | Foot pedal, clutch button, and voice “Hold” command; immediate AI disengage (<10 ms torque disable, <100 ms motion stop) |

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Safety Envelope | Hard limits on tip speed, force, and workspace enforced via control barrier functions (CBFs); software cannot override hardware interlocks |

| Action Shields | All reinforcement learning outputs pass through a safety supervisor that enforces constraints and rate limits |

| Mode Guarding | Autonomy permitted only in labeled “green zones” with verified anatomy; exiting a zone forces immediate reversion to shared control |

| Explainability | On-demand “Why now?” cards display planned path, top segmented structures, confidence, and active constraints; post-hoc counterfactuals show what the controller would have done without safety filters |

| Audit & Traceability | Black-box recorder logs sensor data, commands, model versions, and surgeon inputs to support quality assurance and root-cause analysis |

| Standards-aligned Development | Compliance with ISO 14971 (risk management), IEC 62366 (usability engineering), IEC 60601 (electrical/EMC), IEC 62304 (software lifecycle), and FDA cybersecurity guidance; human supervision is formally required in hazard analysis and design inputs, and autonomy cannot be enabled without active human engagement |

| Category | Description | Metrics / Evaluation |

|---|---|---|

| Datasets | Curated endoscopic/laparoscopic pictures/videos with pixel-wise labels (tissue layers, vessels), Microscopic biopsy images etc. may also be used; synchronized force/position logs and adverse-event tags should be used for training. | Supports perception training and RL supervision; enables anomaly detection |

| Training Protocols | Pretrain perception on large surgical video corpora; fine-tune per organ/site. Train RL in digital twin simulation (photo-real endoscopy + tissue Finite Element Method or FEM) with domain randomization; deploy with safety filter | Accuracy of segmentation, RL adherence to force/velocity constraints, confidence calibration |

| Bench Tests | Assess accuracy, peak force, path error; Ex-vivo tissue: evaluate cut quality, hemostasis using synthetic phantoms (artificial models that simulate human tissues, organs, or anatomical structures). | Path error, peak and mean force, tissue damage, constraint violations |

| User Studies | Novice and expert surgeons perform tasks across modes. Simulate novice and expert surgeon performance in a realistic, reproducible way using human-in-the-loop testing on synthetic phantoms combined with adjustable system parameters and AI-augmented tools. | Task time, path error, max/mean force, tissue damage score, constraint violations, override frequency, NASA-TLX workload |

| Stopping Rules | If any safety-filter intervention exceeding threshold per minute; if any unacknowledged anomaly pauses autonomy | Ensures safe human oversight; triggers session pause |

| Proposed Milestones (M) | Description | Evaluation / Deliverable |

|---|---|---|

| M1: Teleoperation | Baseline teleoperation with full sensing and virtual fixtures on bench phantom | Verify accurate motion, force limits, and path following; initial usability feedback |

| M2: Shared Control | Tremor suppression, force limits, and anatomy-aware virtual fixtures | Measure path error, force adherence, and surgeon workload reduction; refine UI overlays |

| M3: Supervised Autonomy Primitives | Short micro-task automation under pedal-hold and confidence gating | Evaluate task execution accuracy, safety filter performance, and override response |

| M4: Ex-vivo Evaluation | Complete system tested on ex-vivo tissue models | Assess cut quality, hemostasis, constraint violations, and human-factors outcomes |

| M5: Cadaver Lab & Regulatory Prep | IRB-approved cadaver studies; refine risk controls; pre-submission to regulators | Document compliance with safety standards; produce human-factors report and prepare submission package |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).