Introduction

Among Canadian provinces, Alberta stands out for its polarized political discourse and public response to the Covid-19 pandemic, particularly regarding the vaccination of healthcare workers (HCWs). Before the national rollout of Covid-19 vaccines, Alberta already had the highest rate of vaccine refusal in the country: according to polling data, 28% of Albertans - nearly twice the national average of 16% - reported that they would never take the vaccine (Angus Reid Institute, 2021). Even after the rollout, Alberta continued to trail behind most other provinces, with only 71.2% of eligible individuals vaccinated, placing it second-lowest in the country behind Nunavut (Rieger, 2021), and well below the national rate—79.6% of the eligible population in September 2021 (

https://health-infobase.canada.ca/covid-19/vaccination-coverage/archive/2021-09-24/index.html). Despite this clear signal of public reticence, the province’s healthcare institutions and government officials implemented measures that increasingly compelled compliance, including workplace vaccine mandates for HCWs.

Alberta’s policy landscape was also marked by a series of contradictory and often confusing public statements and decisions, as well as tensions within the healthcare labour force, and sectors of it and public health authorities, professional colleges, and unions. In September 2021, as Covid-19 cases reportedly rose sharply, straining intensive care units, Premier Jason Kenney blamed unvaccinated individuals for jeopardizing the healthcare system, describing the crisis as a “pandemic of the unvaccinated” and claiming that unvaccinated people were “50 to 60 times more likely to be hospitalized” (Kaufmann, 2021). These sentiments were echoed by Alberta’s Health Minister Tyler Shandro (Snowdon, 2022) and several physicians – one of whom, Dr. Yael Moudssadji, described unvaccinated patients as “testing” HCWs’ “bank of compassion” (Epp, 2021). Calls for stricter measures also came from multiple medical organizations, including the Alberta Medical Association and the Canadian Pediatric Society (Junker, 2021), with Medicine Hat physicians signing a public letter demanding that all frontline HCWs be vaccinated (Tate, 2021).

Responding to this pressure, on August 31, 2021, Alberta Health Services announced a Covid-19 vaccination requirement for all employees and contractors with a compliance deadline of October 31 (Alberta Health Services, 2021). In the lead-up to implementation, Alberta Health Services reported that 96% of its employees and 99% of its physicians were vaccinated, using these numbers to suggest broad support for the mandate, even as it subsequently extended the deadline to mitigate potential, mandate-driven staffing shortages, especially in rural areas already facing long-standing recruitment challenges (Lee, 2021). For its part, United Nurses of Alberta also endorsed mandated workplace vaccination, albeit criticizing its framing as a labour and political, rather than a public health, issue, and proffering that vaccination requirements should be “determined by public health experts [and not by] an employer or a union”, nor should they be “an item of negotiation between employers and unions” (United Nurses of Alberta, 2021).

Nevertheless, the actual rollout of vaccine mandates sparked vocal opposition. Demonstrations were held outside hospitals in Calgary and other Alberta cities, prompting sharp rebukes from pro-mandate officials and commentators. At Alberta Children’s Hospital, two pediatricians publicly opposed the vaccine mandate, raising concerns about coercion and the erosion of informed consent, and as a result facing criticism from the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Alberta, which accused them of spreading “misinformation about vaccines” and undermining their duty as physicians (Herring, 2021). Legal challenges ensued. In one case, four Alberta physicians sued Alberta Health Services, arguing that the mandate violated constitutional rights and bioethical norms. The plaintiffs requested testing alternatives and objected to the scapegoating of unvaccinated individuals (Gibson, 2021). Though a temporary injunction was denied, Alberta Health Services later modified its policy, allowing approximately 1,400 of the over 1600 employees— out of 121,000— who had been placed on unpaid leave for noncompliance to return to work under a testing regime (Alberta Health Services, 2022).

By early 2022, Premier Kenney had reversed his stance. On February 8, 2022, he publicly asked Alberta Health Services to “bring forward options to eliminate the policy,” proposing that because both vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals could transmit the SARS-CoV2 virus, mandates were no longer scientifically justifiable (Snowdon, 2022). Danielle Smith, who became Premier in October 2022, took this further. She campaigned on ending mandates and initiated a task force to review Alberta’s Covid-19 response. The task force— which included Stanford professor and current National Institutes of Health director Dr. Jay Bhattacharya—recommended halting Covid vaccination for healthy children, and exploring non-mainstream treatments like ivermectin (Strasser, 2025). The recommendations were denounced by opposition parties, medical experts, and public health authorities as “abusive, anti-science and conspiratorial” (The Canadian Press, 2022).

Premier Smith also introduced proposals to amend Alberta’s Human Rights Act and Bill of Rights to prohibit discrimination based on Covid vaccination status. She further claimed that the unvaccinated were “the most discriminated-against group” she had seen in her lifetime (French, 2022), an assertion that many condemned on grounds that they downplayed systemic forms of discrimination and oppression—for instance, against Indigenous Canadians (Markusoff, 2022). Meanwhile, the province introduced compensation for HCWs who had been placed on leave, and on July 18, 2022, Alberta Health Services officially rescinded its mandatory vaccination policy (Alberta Health Services, 2022).

Alberta’s trajectory thus reflects a particularly turbulent and politicized response to Covid-19 workplace vaccination mandates. It also underscores the divisive nature of a policy that has significantly impacted the work conditions, professional relationships, and personal circumstances of hundreds of thousands of HCWs across Canada. This study examined the views and experience of mandated vaccination of close to 200 HCWs in Alberta subject to such mandates. It complements our prior qualitative analysis of these same workers (Chaufan et al., 2025d) and builds on earlier survey-based studies in the provinces of Ontario and British Columbia (Chaufan et al., 2024a, 2025a), similarly exploring personal, institutional and systemic aspects of Covid-related health care workplace policies. As our study will show, in contrast to Ontario and British Columbia, Alberta exhibited a broader spectrum of responses, including some strong support for mandates among a small yet vocal minority of HCWs, which we examine through this province-wide survey.

Methods

The online survey was conducted with a convenience sample of Alberta HCWs. As of 2022, 309,100 people were employed in any capacity in the healthcare and social assistance industry in the province (Government of Alberta, 2023). Eligible respondents included anyone working or having worked in Alberta in a healthcare setting during the vaccination mandate period – whether in patient care, administrative and support roles - from all professions, regardless of age, gender, years of experience, socioeconomic background, race/ethnicity, or vaccination status. Exclusion criteria included not having worked in Alberta in a healthcare setting under mandated vaccination. The initial survey was promoted through social media platforms and the professional networks of the research team using a snowball sampling approach that encouraged respondents to share the invitation with other eligible HCWs (Makwana et al., 2023). Recruitment took place over March and April 2025, with invitations redistributed at seven-day intervals. As noted by Aleck and Settle (2003), a minimum sample size of n=100 is generally considered adequate to generate meaningful data in studies involving large populations (Alreck & Settle, 2003). For the purposes of this exploratory survey, the target sample size was between 100 and 400 respondents. This objective was achieved, with a final sample of n=189 HCWs recruited in Alberta.

Respondents were informed about the purpose of the research and the confidentiality of the data. They completed the online survey after providing their consent at the outset by clicking yes to the question "Do you consent to participate?" and confirming that they currently worked, or had previously worked, in a healthcare setting in Alberta. Following the survey, respondents were entered into a raffle to have the chance to receive a $100 value gift card. The survey consisted of 15 sections, with some automatically skipped depending on vaccination status or whether respondents were terminated for not complying with a workplace vaccination policy. Respondents were asked about their employment status and history, their experience making vaccination decisions and of vaccine mandates in healthcare, and the impacts on patient care. The survey consisted of 88 questions including multiple choice, short answer and Likert style questions The sections included: demographics (8 questions); employment (5 questions); Covid-19 experiences (2 questions); informed consent (11 questions); vaccination decision making (1 question); decision to become vaccinated (2 questions); vaccine side effects (3 questions); accommodations and equity considerations (3 questions); personal impact of vaccination policies (9 questions); self -rated health changes (4 questions); vaccination requirements and employment status (2 questions); impacts of job termination (10 questions); impacts on patient care (23 questions); experiences of HCWs who administered Covid-19 vaccines (4 questions); and a narrative question for providing further comments (1 question).

Given the exploratory nature of this research, only a descriptive analysis was conducted. Survey data were organized and analyzed using Microsoft Excel. Data are reported following APA guidelines for numbers and statistics, which recommend rounding survey or questionnaire data to one decimal place (American Psychological Association., 2024). The research team met regularly to review the data, discuss the analytical approach, and interpret emerging findings. The study was approved by the York University Office of Research Ethics (ORE).

Findings

Demographics

Most respondents (102/189, 54%) were ages 45 - 54 (52/189, 27.5%) or 35 - 44 (50/189, 26.5%), followed by ages 25 - 34 (37/189, 19.6%); 55 - 64 (33/189, 17.5%); over 65 years old (10/189, 5.3%); and 18 - 24 years (2/189, 1.1%). There were more women (159/189, 84.1%) than men (22/189, 11.6%), with two respondents opting not to report their gender (2/189, 1.1%). Most respondents reported Canada as their country of birth (163/189, 86.2%), followed by “other” (country of birth unspecified) (10/189, 5.3%), South Africa (3/189, 1.6%), USA (2/189, 1.1%), Poland (2/189, 1.1%), UK (2/189, 1.1%), and South Korea (2/189, 1.1%). Most respondents were Caucasian / White (163/189, 86.2%), followed by Indigenous (11/189, 5.8%), Filipino (4/189, 2.1%), Chinese (3/189, 1.6%), and European (3/189, 1.6%). Most respondents were married or living with a partner (135/189, 71.4%), while fewer were single (37/189, 19.6%) or widowed (5/189, 2.6%). Most respondents reported some form of caretaking responsibilities - over one third children or stepchildren (70/189, 37.0%), both children and parents (29/189, 15.3%) or only parents (17/189, 9.0%). Most respondents reported some form of nursing credentials – the most common one Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BScN) (75/189, 39.7%), followed by Registered Nurse (RN) or Licensed Practical Nurse (LPN) or Registered Practical Nurse (RPN) diploma (24/189, 12.7%); Nursing Assistant Diploma (8/189, 4.2%); Master of Science in Nursing (MScN) or Master of Nursing (MN) (7/189, 3.7%). Less common credentials included Doctor of Medicine (18/189, 9.5%) and Paramedical or Emergency Medical Technician (EMT) (5/189, 2.6%) (

Table 1).

For socioeconomic status (SES), most respondents reported a middle-income SES (103/189, 54.5%), followed by high middle-income (59/189, 31.2%). Fewer respondents reported a low-income (10/189, 5.3%) or high-income (10/189, 5.3%) SES. Most respondents were employed full time (74/189, 39.2%), followed by part-time employment (66/189, 34.9%), self-employed (17/189, 9.0%); casual (16/189, 8.5%), unemployed (4/189, 2.1%), and contractor (3/189, 1.6%) status. The most commonly reported profession / area of occupation was as a registered nurse or psychiatric nurse (84/189, 44.4%), followed by licensed practical nurse (17/189, 9.0%); and general practitioner / family physician (15/189, 7.9%). About one fourth of respondents reported being in clinical practice (47/189, 24.9%) while a small minority was not (5/189, 2.6%) and another small minority reported an academic appointment / university affiliation (11/189, 5.8%). Most respondents reported between 5 and 9 years of education / training (70/189, 37.0%), followed by 0-4 years (65/189, 34.4%) and 10 or more (49/189, 25.9%). Finally, regarding years of experience in their most recent career, most respondents reported 11 - 15 years (38/189, 20.1%), followed by 6 - 10 years (33/189, 17.5%), 16 - 20 years (27/189, 14.3%), 0 - 5 years (23/189, 12.1%), 26 - 30 years (20/189, 10.6%), and 21 - 25 years (17/189, 9.0%). (

Table 1).

Vaccination Status

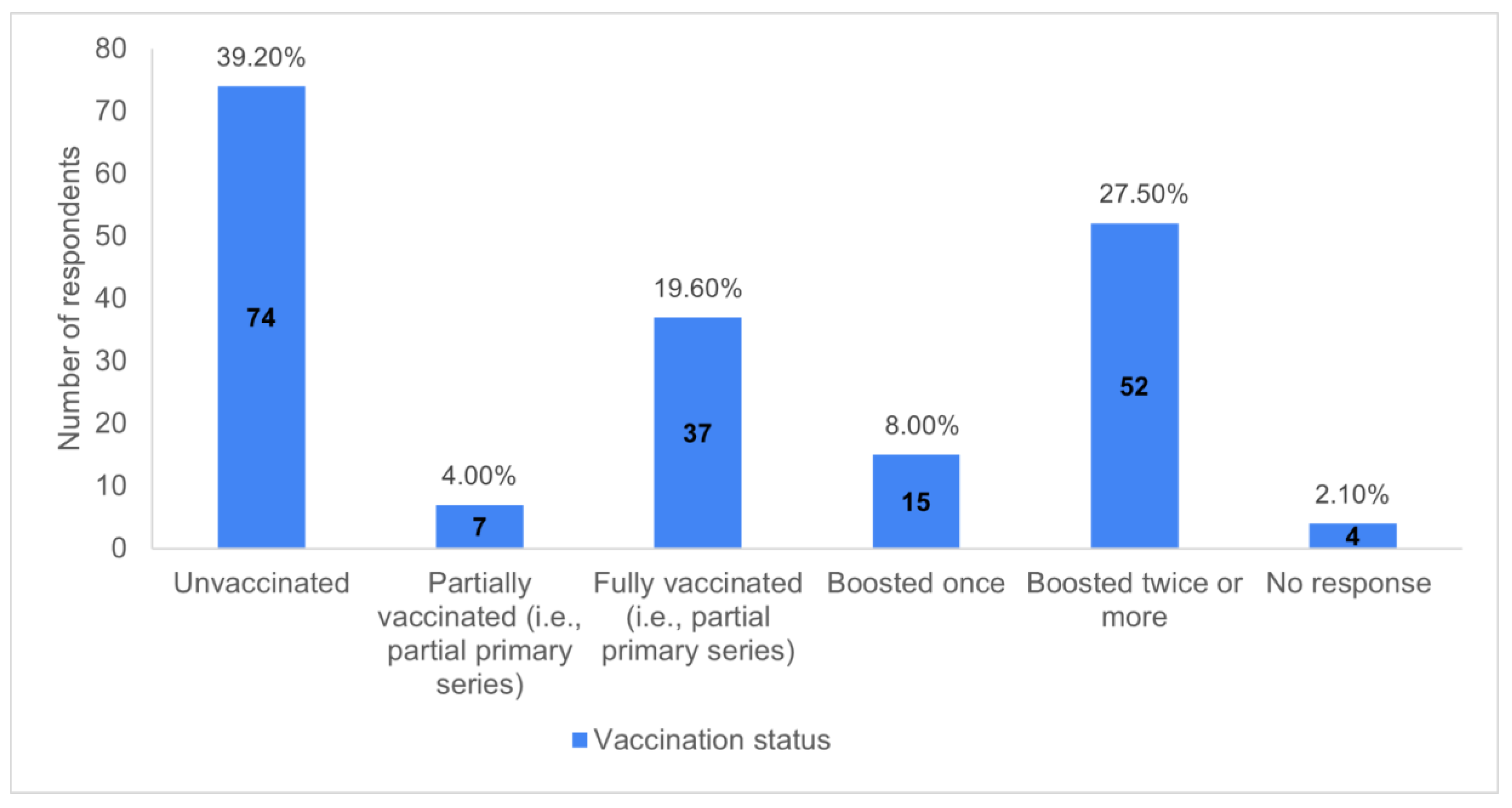

Most respondents had received a Covid-19 vaccine (111/189, 58.7%), and more than one - third were unvaccinated (74/189, 39.2%). Of those who were vaccinated, over one quarter of respondents had received two or more boosters (52/189, 27.5%), nearly one fifth had completed a partial primary series (37/189, 19.6%), less than one tenth had been boosted once (15/189, 7.9%), and a small minority were partially vaccinated (7/189, 3.7%). (

Chart 1).

Vaccination Decision and Experiences

Among those who received Covid-19 vaccines, the main reported reason was to protect themselves from severe outcomes (37/111, 33.3%). The second most common reason was because it was mandated at work (33/111, 29.7%). Other frequently cited reasons included to protect the larger community from severe outcomes (18/111, 16.2%), to protect loved ones from severe outcomes (15/111, 13.5%), or because it was mandated by an educational institution (2/111, 1.8%). (

Table 2).

Mild reactions were reported by nearly one third of vaccinated respondents after the first dose (32/111, 28.8%), nearly one third of respondents after the second dose (34/111, 30.6%), and no respondents after the third or later dose. Moderate reactions were reported in a small number of respondents after the first dose (7/111, 6.3%), one tenth of respondents after the second dose (11/111, 10.0%), and two respondents after a third or later dose (2/111, 1.8%). Severe reactions were reported in a small number of respondents after the first dose (6/111, 5.4%), the second dose (3/111, 2.7%), and the third of later dose (3/111, 2.7%), whereas one third (41/111, 36.9%) reporting having had no adverse reactions. (

Table 2).

When asked if they had communicated adverse reactions to a general practitioner (GP) or family doctor or other medical personnel, only a small percentage (6/111, 5.4%) reported that they had communicated their reaction and that a report had been filed, roughly the same percentage (5/111, 4.5%) communicated their reaction, but no report was filed, and a similar proportion (6/111, 5.4%) communicated a reaction but did not know if a report had been filed. Over one-third of respondents (38/111, 34.2%) never communicated their reaction to a doctor. Finally, over tenth (14/111, 12.6%) of vaccinated respondents reported that they had experienced an adverse reaction post vaccination yet had still been required to take additional doses. (

Table 2).

Accommodations & Equity Considerations

About one quarter (48/189, 25.4%) of respondents reported that they had been terminated or laid off due to their decision to not receive the Covid-19 vaccine – either first or subsequent doses. Over three quarters of respondents (145/189, 76.7%) reported that they had not been offered any alternatives to vaccination - such as testing, working offsite, or proving natural immunity. Some HCWs had requested exemptions – the most common grounds being religious (40/189, 21.2%), followed by medical (16/189, 8.5%) and conscientious objection (12/189, 6.3%). However, about one quarter of respondents (46/189, 24.3%) who had sought exemptions were denied, and only a small number received one (3/189, 1.6%). Finally, nearly one fifth of respondents (36/189, 19.1%) reported that they had not requested an exemption because they believed that they did not meet official eligibility criteria. (

Table 3).

Personal Impact of Vaccination Policies

A small minority of respondents (32/189, 16.9%) agreed (14/189, 7.4%) or strongly agreed (18/189, 9.5%) that their income was less than it was prior to the introduction of vaccination mandates. The percentage was higher among terminated respondents – nearly one third of the sample (61/189 - 32.2%) - most of whom (45/61, 73.8%) agreed (12/61, 19.7%) or strongly agreed (33/61, 54.1%) with the statement “Losing my job significantly reduced my income”. As well, a small minority of respondents (20/189, 10.6%) agreed (8/189, 4.2%) or strongly agreed (12/189, 6.3%) that they had suffered chronic physical ailments due to employer vaccination requirements. Again, the percentage was higher among terminated respondents, most of whom (35/61, 57.4%) agreed (17/61, 27.9%) or strongly agreed (18/61, 29.5%) that losing their job had negatively impacted their physical health. Also, a small minority of respondents (9/189, 4.7%) agreed (4/189, 2.1%) or strongly agreed (5/189, 2.6%) that they had suffered from a physical disability due to employer vaccination requirements.

Negative mental health impacts were even more pronounced than physical ones. Over one third of respondents (71/189, 37.6%) agreed (22/189, 11.6%) or strongly agreed (49/189, 25.9%) that they had experienced anxiety or depression due to employer vaccination requirements. Again, the impact was greater among terminated respondents, most of whom (44/61, 72.1%) agreed (13/61, 21.3%) or strongly agreed (31/61, 50.8%) that losing their job had a negative impact on their mental health. Also, a minority of respondents (14/189, 7.4%) agreed (5/189, 2.6%) or strongly agreed (9/189, 4.8%) with the statement “I have experienced suicidal thoughts due to employer vaccination requirements.” Similarly, approximately one fifth of respondents (41/189, 21.7%) agreed (16/189, 8.5%) or strongly agreed (25/189, 13.2%) that they had sought help from a counsellor due to situations arising from vaccination requirements. Nearly half of respondents (89/189, 47.1%) agreed (25/189, 13.2%) or strongly agreed (64/189, 33.9%) that their personal relationships had suffered due to situations arising from vaccination requirements. Finally, nearly one half of respondents (89/189, 47.1%) agreed (15/189, 7.9%) or strongly agreed (74/189, 39.2%) with the statement “I feel I have been unfairly treated by my employer regarding vaccination requirements.” (

Table 5).

Self—Rated Health Changes

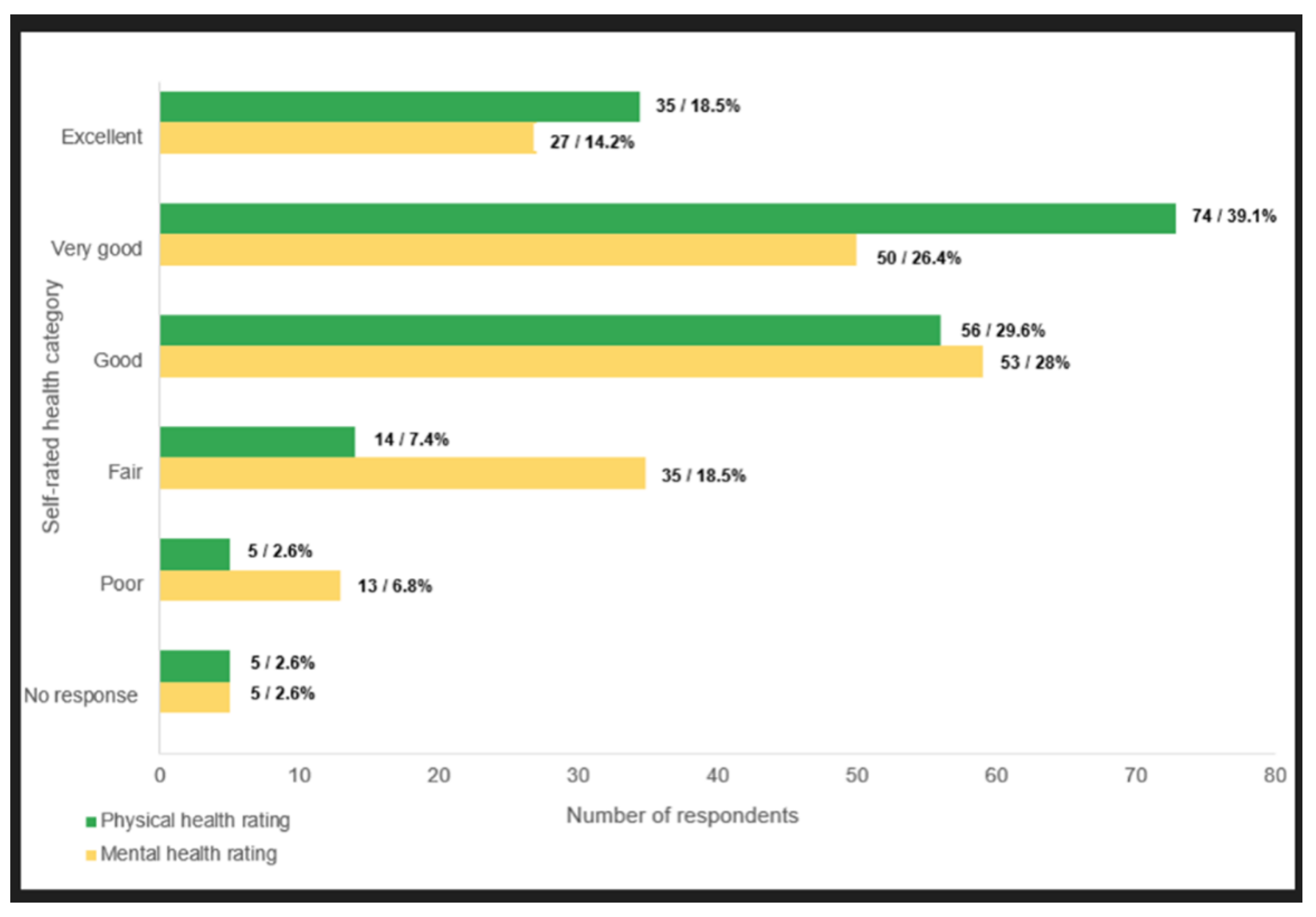

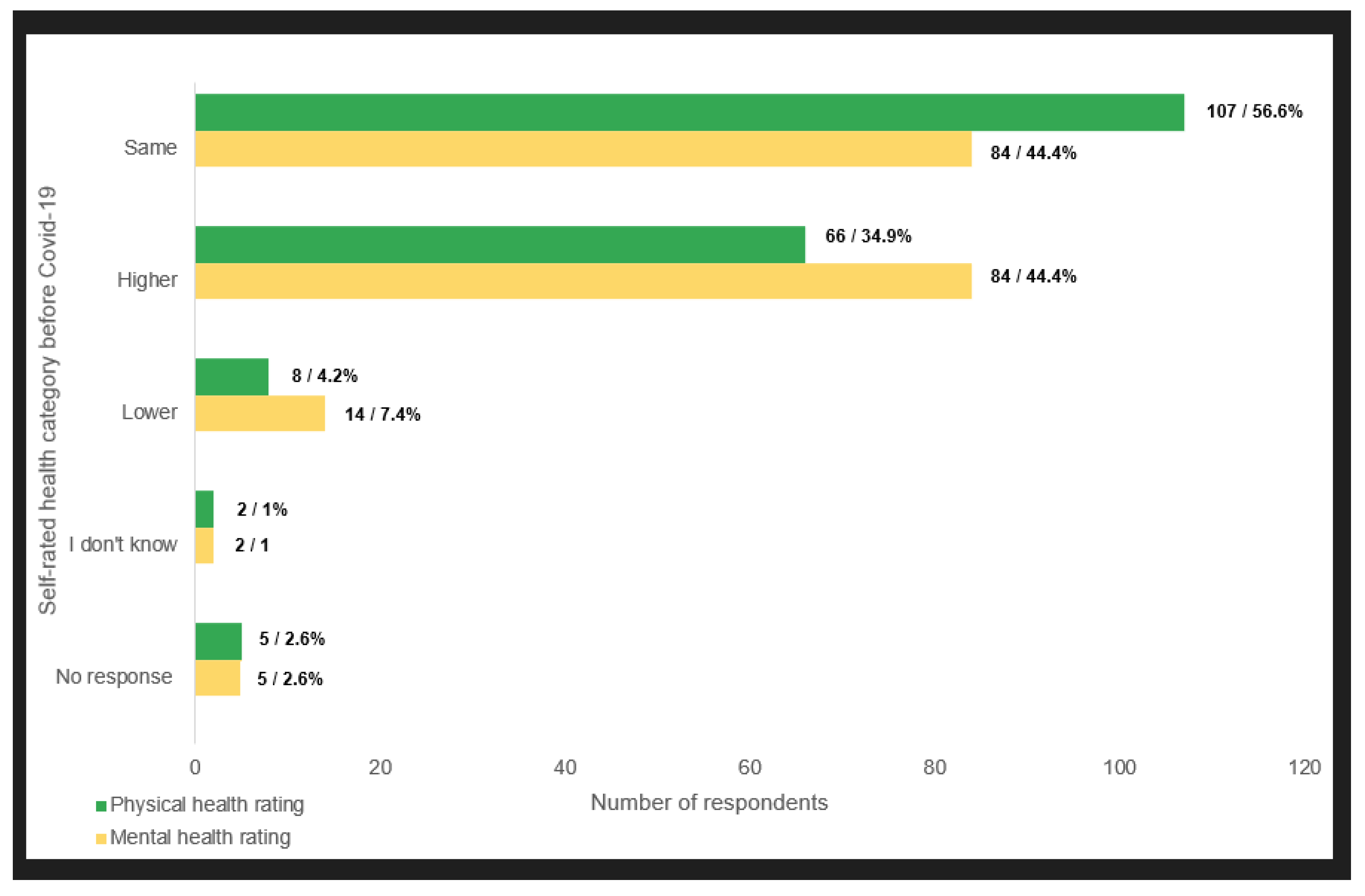

Over one third of respondents (66/189, 34.9%) reported that their physical health rating was higher before the Covid crisis. An equal proportion of respondents (84/189, 44.4% each) self - rated their mental health as having been the same as, or higher, before Covid (

Chart 2 and

Chart 3).

Vaccination Requirements and Employment Status and Conditions

One quarter (48/189, 25.4%) of respondents reported that they were terminated or laid off due to their decision to not receive the Covid-19 vaccine – either a first or subsequent doses. In addition, about one fifth (37/189, 19.6%) reported that they were subjected to disciplinary measures other than termination, such as being accused of professional misconduct, reported to licensing colleges, temporary suspension of pay, exclusion from pension plan, or having their professional license withdrawn. A small minority (10/189, 5.3%) reported being rehired in Alberta after having been terminated in another province (e.g. British Columbia) for refusing to accept mandated vaccination. (

Table 6).

Most respondents (121/189, 64.1%) agreed (43/189, 22.8%) or strongly agreed (78/189, 41.3%) that they had experienced conflict among colleagues at work after the introduction of vaccines and / or vaccination policies, and most (110/189, 58.2%) also agreed (37/189, 19.6%) or strongly agreed (73/189, 38.6%) that they had experienced conflict between employees and management at work after the introduction of vaccines and / or vaccination policies. As well, most respondents (123/189, 65.0%) agreed (39/189, 20.6%) or strongly agreed (84/189, 44.4%) that they knew of HCWs who had taken early retirement due to Covid-19 policies. Most (125/189, 66.1%) also agreed (33/189, 17.5%) or strongly agreed (92/189, 48.7%) that they knew of HCWs who had been laid off due to failure to comply with vaccination requirements. An even greater proportion (131/189, 69.3%) agreed (37/189, 19.6%) or strongly agreed (94/189, 49.7%) that they knew of HCWs who had resigned because they did not wish to take the vaccine. In addition, over one third of respondents (66/189, 34.9%) agreed (20/189, 10.6%) or strongly agreed (46/189, 24.3%) that they knew of students in the health professions who had been deregistered due to non-compliance with vaccination policies. Finally, among terminated workers nearly one third of respondents (18/61, 29.5%) disagreed (2/61, 3.3%) or strongly disagreed (16/61, 26.2%) with the statement: “I would return to my previous role if possible / if mandates were dropped.” Finally, about one fifth of respondents (40/189, 21.5%) agreed (18/89, 9.5%) or strongly agreed (22/189, 11.6%) with the statement “I intend to leave my occupation / the healthcare sector/industry due to my experiences with the Covid-19 policy response”. (

Table 7).

Impact on Patient Care

Over three quarters (150/189, 79.4%) of respondents had worked with Covid-19 positive or suspected patients’ pre - vaccine mandate. Most (124/189, 65.6%) agreed (55/189, 29.1%) or strongly agreed (69/189, 36.5%) that they had observed concerning patient care or procedural changes coinciding with the onset of the Covid-19 crisis, and a slightly lower proportion (114/189, 60.3%) agreed (39/189, 20.6%) or strongly agreed (75/189, 39.7%) that they had observed concerning patient care changes upon the introduction of vaccines. Similarly, most respondents (107/189, 56.6%) agreed (29/189, 15.3%) or strongly agreed (78/189, 41.3%) that they had observed differential treatment of patients based on their vaccination status and about half of respondents (94/189, 49.7%) agreed (27/189, 14.3%) or strongly agreed (67/189, 35.4%) that they had observed an increase in patient harms associated with the Covid-19 vaccines.

Over half of respondents (104/189, 55.0%) disagreed (29/189, 15.3%) or strongly disagreed (75/189, 39.7%) with the statement “I felt free to express any concerns I had about patient care or potential vaccine harms with my employer.” Additionally, a large minority of respondents (72/189, 38.1%) disagreed (11/189, 5.8%) or strongly disagreed (61/189, 32.3%) that if they expressed concerns about patient care or potential vaccine harms, these concerns were documented and acted upon by their employer. Most (113/189, 59.8%) also disagreed (35/189, 18.5%) or strongly disagreed (78/189, 41.3%) with the statement “From the perspective of a potential patient, I am confident that the current healthcare system will provide adequate and quality care while respecting my personal preferences and values.”

A large minority of respondents (71/189, 37.6%) agreed (23/189, 12.2%) or strongly agreed (48/189, 25.4%) that they had been accused of undermining the Covid-19 public health response / patient care due to their views / decisions about vaccination, and just under one quarter (43/189, 22.8%) agreed (17/189, 9.0%) or strongly agreed (26/189, 13.8%) that they had been disciplined for that same reason. A minority (31/189, 16.4%) agreed (15/189, 7.9%) or strongly agreed (16/189, 8.5%) that they had been coerced into recommending / administering Covid-19 vaccines against their best clinical judgment (e.g., patient may experience an adverse event, has experienced an adverse event post vaccination, patient too young / old to benefit from vaccination, patient experienced Covid-19 and likely has strong natural immunity).

Over half of HCWs (106/189, 56.1%) responded “no” when asked if they had been encouraged to report adverse events post vaccination if observed. A similar percentage reported “no” when asked if they had been trained to report such events (102/189, 54.0%) and one third reported that they had been encouraged to tell patients that the vaccines were safe and effective (63/189, 33.3%) or to trust health officials and sources (63/189, 33.3%). Finally, one quarter of respondents also reported being encouraged to dismiss non - officially approved information as ‘misinformation’ (48/ 189, 25.4%) (

Table 8 and

Table 9).

For Healthcare Workers Who Administered COVID—19 Vaccines

A small minority of respondents (30/189, 15.9%) administered Covid-19 vaccines. Of these, one third (10/30, 33.3%) reported that they received compensation for the task, with one respondent (1/30, 3.3%) strongly agreeing that the compensation received was greater than what they would otherwise have received for comparable practices. As well, most of these respondents (21/30, 70.0%) agreed (10/30, 33.3%) or strongly agreed (11/30, 36.7%) that they believed that Covid vaccines could cause serious or life - threatening injuries, including death. Finally, when asked about their feelings upon administering vaccines, the most common selections were either “Energized; I was part of the solution for a serious public health problem” (18/30, 60.0%) or “Uneasy; I did not know what might happen to vaccine recipients” (17/30, 56.7%) (other options included: “accepting; it was part of my responsibility”; “prefer not to answer”; and “other”) . Notably, over one quarter of these respondents (8/30, 26.7%) agreed (3/30, 10.0%) or strongly agreed (5/30, 16.7%) with the statement “I was coerced into recommending/administering Covid-19 vaccines against my best clinical judgment” (

Table 8).

Discussion

In our Alberta survey, most respondents had been vaccinated, with more than one-quarter receiving two or more boosters. However, nearly one-third reported workplace mandates as a primary reason for vaccination, suggesting that institutional pressure—rather than informed and autonomous decision-making—played a significant role. A considerable number also reported a lack of written information and a perceived lack of freedom of choice, raising concerns about the erosion of informed consent, a foundational principle of biomedical ethics both in contemporary Canada (Canadian Medical Protective Association, 2024) and historically (Shuster, 1997).

While reports of severe reactions were relatively rare, nearly two-thirds of vaccinated respondents reported experiencing some form of adverse event. Among these, several indicated being required to take additional doses despite prior adverse reactions. However, formal reporting of adverse events was uncommon, and most participants who experienced them noted the absence of formal follow-up or documentation by occupational health services. These gaps may reflect structural disincentives to reporting, a broader climate of institutional distrust, or fear of professional retaliation, observed in some settings (Ansah et al., 2025). Consistent with prior research, the joint effect of these structural barriers and the absence of institutional response undermine confidence in accountability structures and damage the trust that healthcare institutions rely on, particularly in times of crisis (Kumah, 2025).

Many respondents described their vaccination decisions as driven by fear of losing their jobs or by explicit employer coercion. This confirms earlier findings from our Ontario and British Columbia surveys, in which HCWs who complied with mandates often described doing so under duress, without trust in the intervention, and while harbouring deep ethical unease (Chaufan et al., 2024b, 2025a). Although mandates were presented as a public health necessity, the experiences of respondents suggest a breakdown of ethical norms within healthcare employment practices, including violations of bodily autonomy, professional judgment, and clinical discretion. This echoes traditional concerns raised in the literature regarding the use of coercive /manipulative strategies under the guise of public health rationality (Green & Fazi, 2023; Lupton, 1995).

The Alberta data also offer insights into the consequences of such mandates for institutional functioning. Several respondents noted that mandate enforcement strained already fragile staffing levels, led to the exclusion of experienced personnel, and reduced morale among remaining staff. These outcomes were not peripheral but central to the policy’s implementation and aftermath. While proponents justified mandates as necessary for patient safety and healthcare system resilience, our findings do not support this narrative. Instead, the data suggest that mandates exacerbated precisely the vulnerabilities they were intended to address — contributing to workforce instability, deteriorating team cohesion, and erosion of trust in management — patterns that have also been observed in other studies (Hatch et al., 2023; Heyerdahl et al., 2023).

Justifications for vaccine mandates often rested on claims about protecting vulnerable patients and ensuring workplace safety. However, these claims became increasingly difficult to sustain as evidence mounted early on that Covid-19 vaccines did not prevent infection or transmission (Brown et al., 2021; Hetemäki et al., 2021; Singanayagam et al., 2021; Subramanian & Kumar, 2021) and were associated with significant harms (Faksova et al., 2024; Fraiman et al., 2022; Hulscher et al., 2023; Mead1 et al., 2025; Polykretis et al., 2023) — particularly among low-risk populations, where no compelling benefit–risk justification has been established (Bardosh, Krug, et al., 2022; Chua et al., 2021; Ioannidis, 2021).

The mismatch between official rationales and workers’ lived experience undermined the credibility of both policy and leadership. It also contributed to a broader epistemic breakdown, where healthcare workers reported feeling censored or silenced when raising legitimate clinical or ethical concerns—a finding consistent with growing documentation of institutional suppression. during the pandemic era (Agamben, 2021; Martin, 2025; Shir-Raz et al., 2023).

These patterns raise fundamental questions about the governance of healthcare and the boundaries of professional autonomy. In many accounts, healthcare workers described not only personal injury or coercion but a deeper disillusionment with the ethical architecture of their profession. The policy environment, they suggested, had transformed core ethical commitments—such as “do no harm,” informed consent, and bodily autonomy—into liabilities. Particularly concerning was the sense that dissent, even when grounded in clinical reasoning or observed harm, was met not with debate but with punitive enforcement. This not only degrades morale but risks long-term damage to healthcare systems that depend on open dialogue, ethical judgment, and mutual trust (Bardosh, Figueiredo, et al., 2022).

Limitations and Strengths of the Study

This study has several limitations. First, it relied on a convenience sample of HCWs. Although we promoted the study through multiple channels and invited participation from HCWs of all vaccination statuses, over half of respondents were vaccinated—consistent with the rates of vaccination among HCWs in Alberta. Most participants were also women, aligning with the demographic composition of the Canadian healthcare workforce (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2025) . In addition, most respondents were mid-to late- career professionals, a demographic likely to have been disproportionately affected by employment policies tied to vaccination status, due to financial, professional, and family responsibilities. Taken together, the findings from this convenience sample may not be representative or generalizable to all HCWs in the province.

However, this limitation is not unique to our study. The largest national survey of Canadian HCWs conducted during the Covid-19 pandemic—by Ipsos for the Public Health Agency of Canada—also relied on a convenience sample (Ipsos & Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), 2023). That cross-sectional survey of 5,372 HCWs found that for approximately half of respondents, the threat of job loss was a key driver of vaccination, challenging the widespread assumption that vaccine uptake reflects “acceptance” rather than coercion (Chaufan & Hemsing, 2024). Finally, another limitation is the cross-sectional design of our survey and the use of descriptive statistical analyses. As such, we are unable to examine changes in patterns over time or to explore associations between variables.

Despite these limitations, the study has several notable strengths. Most importantly, it addresses a gap in the literature. Previous studies on HCWs’ attitudes toward mandatory vaccination have overwhelmingly focused on vaccinated respondents. For example, a recent systematic review acknowledged that all included studies were based on highly vaccinated samples—a limitation the authors identified as a potential source of bias (Politis et al., 2023). By contrast, although more than half of our respondents were vaccinated, our sample captured a broader range of perspectives, including many critical of vaccine mandates. This was possible because we did not recruit through medical institutions—which would have limited the sample to employed (and therefore vaccinated) HCWs—but instead used social media channels, which enabled access to a wider cross-section of the healthcare workforce. In doing so, we were able to include the voices of those most directly affected by vaccination policies.

Conclusions

Our findings contribute to a growing body of empirical evidence—now encompassing three Canadian provinces—documenting that vaccine mandates for HCWs did not meet core scientific or ethical standards (Chaufan et al., 2024a, 2025a, 2025c, 2025b, 2025d). While such mandates were justified by their proponents as necessary to protect patients and preserve healthcare capacity, our data offer no support for either claim. On the contrary, mandates appear to have intensified workforce strain, eroded workplace trust, and undermined the principle of informed consent without demonstrable benefit to patient outcomes or public health. Future policy responses to public health crises must be grounded in transparent scientific reasoning and uphold the ethical foundations of healthcare practice, including the right of workers to make voluntary medical decisions free from coercion.

Author Contributions

(CRediT taxonomy) Conceptualization: Claudia Chaufan; Methodology: Claudia Chaufan; Writing – Original Draft: Claudia Chaufan; Writing – Review & Editing: Claudia Chaufan, Natalie Hemsing, Rachael Moncrieffe; Investigation: Natalie Hemsing and Claudia Chaufan; Formal Analysis: Claudia Chaufan, Natalie Hemsing & Rachael Moncrieffe.

Acknowledgments

CC thanks the professional and lay organizations, students, trainees, and friends who have afforded spaces of reflection and debate over the past years, and especially Julian Field, for his continuing support. NH thanks her family and friends for their encouragement and support, and Dr. Chaufan for her mentorship. RM thanks her friends, family, and Dr. Chaufan for their support and guidance. All authors are grateful to the participants for sharing with us their life experiences and making this study possible. This work was supported by a New Frontiers in Research Fund (NFRF) 2022 Special Call, NFRFR-2022-00305. The funders played no role in the conception, conduction, or publication of this study

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare

Ethical Statement

The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was approved by the York University Office of Research Ethics (No. 2023-389).

References

- Agamben, G. (with Dani, V.). (2021). Where Are We Now? The Epidemic as Politics.

- Alberta Health Services. (2021, August 31). Alberta Health Services implementing immunization policy for physicians, staff and contracted providers, 31 August.

- Alberta Health Services. (2022, July 18). AHS will no longer require COVID-19 immunization as condition of employment, 18 July.

- Alreck, P. , & Settle, R. (2003). Survey Research Handbook.

- American Psychological Association. (2024). APA Style numbers and statistics guide.

- Angus Reid Institute. (2021). Vaccine Vacillation: Confidence in AstraZeneca jumps amid increased eligibility; trust in Johnson & Johnson tumbles.

- Ansah, N. A. , Weibel, D., Chatio, S. T., Oladokun, S. T., Duah, E., Ansah, P., Oduro, A., Hollestelle, M., & Sturkenboom, M. Barriers and strategies to improve vaccine adverse events reporting: Views from health workers and managers in Northern Ghana. BMJ Public Health 2025, 3, e001464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardosh, K. , Figueiredo, A. de, Gur-Arie, R., Jamrozik, E., Doidge, J., Lemmens, T., Keshavjee, S., Graham, J. E., & Baral, S. The unintended consequences of COVID-19 vaccine policy: Why mandates, passports and restrictions may cause more harm than good. BMJ Global Health 2022, 7, e008684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardosh, K. , Krug, A., Jamrozik, E., Lemmens, T., Keshavjee, S., Prasad, V., Makary, M. A., Baral, S., & Høeg, T. B. (2022). COVID-19 vaccine boosters for young adults: A risk benefit assessment and ethical analysis of mandate policies at universities. Journal of Medical Ethics. [CrossRef]

- Brown, C. M. , Vostok, J., Johnson, H., Burns, M., Gharpure, R., Sami, S., Sabo, R. T., Hall, N., Foreman, A., Schubert, P. L., Gallagher, G. R., Fink, T., Madoff, L. C., Gabriel, S. B., MacInnis, B., Park, D. J., Siddle, K. J., Harik, V., Arvidson, D., … Laney, A. S. Outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 Infections, Including COVID-19 Vaccine Breakthrough Infections, Associated with Large Public Gatherings—Barnstable County, Massachusetts, July 2021. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2021, 70, 1059–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2025). Health workforce in Canada: Overview.

- Canadian Medical Protective Association. (2024). Consent A guide for Canadian physicians 4th edition, /: Medical Protective Association. https.

- Chaufan, C. , & Hemsing, N. Is resistance to Covid-19 vaccination a “problem”? A critical policy inquiry of vaccine mandates for healthcare workers. AIMS Public Health 2024, 11, Article publichealth–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaufan, C. , Hemsing, N., & Moncrieffe, R. (2024a). Covid-19 vaccination decisions and impacts of vaccine mandates: A cross sectional survey of healthcare workers in Ontario, Canada. medRxiv, 2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaufan, C. , Hemsing, N., & Moncrieffe, R. (2024b). COVID-19 vaccination decisions and impacts of vaccine mandates: A cross sectional survey of healthcare workers in Ontario, Canada. Journal of Public Health and Emergency. [CrossRef]

- Chaufan, C. , Hemsing, N., & Moncrieffe, R. (2025a). COVID-19 vaccination decisions and the impact of vaccination mandates: An exploratory cross-sectional survey of healthcare workers in British Columbia, Canada. Global Health Economics and Sustainability. [CrossRef]

- Chaufan, C. , Hemsing, N., & Moncrieffe, R. (2025b). “If all of this was about health, I’d still be working:” Lived experiences of healthcare workers under COVID-19 vaccine mandates in British Columbia, Canada. Global Health Economics and Sustainability, 2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaufan, C. , Hemsing, N., & Moncrieffe, R. (2025c). “It isn’t about health, and it sure doesn’t care”: A qualitative exploration of healthcare workers’ lived experience of the policy of vaccination mandates in Ontario, Canada. Journal of Public Health and Emergency. [CrossRef]

- Chaufan, C. , Hemsing, N., & Moncrieffe, R. (2025d). “When I had concerns about my own patients…I was told to keep quiet”: Moral Injury in the Era of Mandates Among Healthcare Workers in Alberta, Canada, 2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, G. T. , Kwan, M. Y. W., Chui, C. S. L., Smith, R. D., Cheung, E. C.-L., Tian, T., Leung, M. T. Y., Tsao, S. S. L., Kan, E., Ng, W. K. C., Man Chan, V. C., Tai, S. M., Yu, T. C., Lee, K. P., Wong, J. S. C., Lin, Y. K., Shek, C. C., Leung, A. S. Y., Chow, C. K., … Ip, P. (2021). Epidemiology of Acute Myocarditis/Pericarditis in Hong Kong Adolescents Following Comirnaty Vaccination. Clinical Infectious Diseases. [CrossRef]

- Epp, C. (2021, August 30). Inoculation frustration: Compassion of doctors, nurses tested treating Alberta’s unvaccinated COVID-19 patients. CTV News, 30 August.

- Faksova, K. , Walsh, D., Jiang, Y., Griffin, J., Phillips, A., Gentile, A., Kwong, J. C., Macartney, K., Naus, M., Grange, Z., Escolano, S., Sepulveda, G., Shetty, A., Pillsbury, A., Sullivan, C., Naveed, Z., Janjua, N. Z., Giglio, N., Perälä, J., … Hviid, A. (2024). COVID-19 vaccines and adverse events of special interest: A multinational Global Vaccine Data Network (GVDN) cohort study of 99 million vaccinated individuals. Vaccine. [CrossRef]

- Fraiman, J. , Erviti, J., Jones, M., Greenland, S., Whelan, P., Kaplan, R. M., & Doshi, P. (2022). Serious adverse events of special interest following mRNA COVID-19 vaccination in randomized trials in adults. Vaccine. [CrossRef]

- French, J. (2022, October 11). New Alberta premier says unvaccinated “most discriminated against group” after swearing-in CBC News.pdf. CBC News, 11 October 6612. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J. (2021, October 25). 4 Alberta doctors launch lawsuit over mandatory COVID-19 vaccine policy. CBC News, 25 October.

- Government of Alberta. (2023). Alberta Health Care and Social Assistance Industry Profile, 2021 and 2022.

- Green, T. , & Fazi, T. (2023). The Covid Consensus: The Global Assault on Democracy and the Poor?a Critique from the Left.

- Hatch, B. A. , Kenzie, E., Ramalingam, N., Sullivan, E., Barnes, C., Elder, N., & Davis, M. M. Impact of the COVID-19 vaccination mandate on the primary care workforce and differences between rural and urban settings to inform future policy decision-making. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0287553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herring, J. (2021, September 24). Alberta Children’s Hospital doctors face criticism for letters opposing vaccine mandate. Calgary Herald, 24 September.

- Hetemäki, I. , Kääriäinen, S., Alho, P., Mikkola, J., Savolainen-Kopra, C., Ikonen, N., Nohynek, H., & Lyytikäinen, O. An outbreak caused by the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant (B. 1.617. 2) in a secondary care hospital in Finland, May 2021. Eurosurveillance 2021, 26, 2100636. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Heyerdahl, L. W. , Dielen, S., Dodion, H., Van Riet, C., Nguyen, T., Simas, C., Boey, L., Kattumana, T., Vandaele, N., & Larson, H. J. Strategic silences, eroded trust: The impact of divergent COVID-19 vaccine sentiments on healthcare workers’ relations with peers and patients. Vaccine 2023, 41, 883–891. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hulscher, N. , Hodkinson, R., Makis, W., Malhotra, A., & McCullough, P. (2023). Autopsy Proven Fatal COVID-19 Vaccine-Induced Myocarditis. [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, J. P. A. COVID-19 vaccination in children and university students. European Journal of Clinical Investigation 2021, 51, e13678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ipsos & Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). (2023). National cross-sectional survey of health workers’ perceptions of COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness, acceptance, and drivers of vaccine decision-making, /: Health Agency of Canada (PHAC); Registration Number: 127-22 (HC POR 22-28). https, 2024.

- Junker, A. (2021, September 28). “Life and death”: Alberta Medical Association calls for “5re-breaker” COVID-19 public health measures. Edmonton Journal, 28 September.

- Kaufmann, B. (2021, September 3). Anti-vaccine protesters harassing health care workers, patients: AHS president. Calgary Herald, 3 September.

- Kumah, A. Adverse event reporting and patient safety: The role of a just culture. Frontiers in Health Services 2025, 5, 1581516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J. (2021, November 19). 96% of AHS workers immunized but holdouts remain as COVID-19 vaccine mandate deadline looms. CBC News, 19 November 6255. [Google Scholar]

- Lupton, D. (1995). The Imperative of Health: Public Health and the Regulated Body.

- Makwana, D. , Engineer, P., Dabhi, A., & Chudasama, H. (2023). Sampling Methods in Research A Review.

- Markusoff, J. (2022, October 14). Danielle Smith wants vaccine status to be a human right. Expect a petri dish of problems. CBC News, 14 October 6615. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, B. Covid Cover-up: Secrecy, Censorship and Suppression during the Pandemic. Secrecy and Society 2025, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead1, M. N. , Rose2, J., Makis3, W., Milhoan4, K., & McCullough6, N. H. 5 and P. A. (2025). Myocarditis after SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination: Epidemiology, outcomes, and new perspectives. International Journal of Cardiovascular Research & Innovation, 3738. [Google Scholar]

- Politis, M. , Sotiriou, S., Doxani, C., Stefanidis, I., Zintzaras, E., & Rachiotis, G. Healthcare Workers’ Attitudes towards Mandatory COVID-19 Vaccination: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines. [CrossRef]

- Polykretis, P. , Donzelli, A., Lindsay, J. C., Wiseman, D., Kyriakopoulos, A. M., Mörz, M., Bellavite, P., Fukushima, M., Seneff, S., & McCullough, P. A. Autoimmune inflammatory reactions triggered by the COVID-19 genetic vaccines in terminally differentiated tissues. Autoimmunity 2023, 56, 2259123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieger, S. (2021, September 13). Calgary hospitals cancel surgeries for 2nd week as protesters outside defend right to be unvaccinated. CBC News, 13 September 6174. [Google Scholar]

- Shir-Raz, Y. , Elisha, E., Martin, B., Ronel, N., & Guetzkow, J. Censorship and Suppression of Covid-19 Heterodoxy: Tactics and Counter-Tactics. Minerva 2023, 61, 407–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuster, E. Fifty Years Later: The Significance of the Nuremberg Code. New England Journal of Medicine 1997, 337, 1436–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singanayagam, A. , Hakki, S., Dunning, J., Madon, K. J., Crone, M. A., Koycheva, A., Derqui-Fernandez, N., Barnett, J. L., Whitfield, M. G., Varro, R., Charlett, A., Kundu, R., Fenn, J., Cutajar, J., Quinn, V., Conibear, E., Barclay, W., Freemont, P. S., Taylor, G. P., … Lackenby, A. Community transmission and viral load kinetics of the SARS-CoV-2 delta (B.1.617.2) variant in vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals in the UK: A prospective, longitudinal, cohort study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. [CrossRef]

- Snowdon, W. (2022, March 1). Premier calls for end to vaccine mandate for Alberta Health Services sta! CBC News, 1 March 6369. [Google Scholar]

- Strasser, S. (2025, January 25). Alberta’s “contrarian” COVID-19 review task force releases final report. Calgary Herald, 25 January.

- Subramanian, S. V. , & Kumar, A. (2021). Increases in COVID-19 are unrelated to levels of vaccination across 68 countries and 2947 counties in the United States. European Journal of Epidemiology. [CrossRef]

- Tate, R. (2021, August 24). Medicine Hat doctors want mandatory vaccines for those who deal directly with patients CHAT News Today.pdf, 24 August 2021. [Google Scholar]

- The Canadian Press, N. (2022, November 18). “Warped stance on COVID”: Fired Alberta Health Services board member calls out Smith. The Canadian Press, 18 November 2022. [Google Scholar]

- United Nurses of Alberta. (2021, September 1). United Nurses of Alberta response to Alberta Health Services mandatory COVID-19 vaccination policy, 1 September.

Chart 1.

Vaccination status. Unvaccinated: 74; Partially or fully vaccinated or boosted: 111; Non-responders: 4; Total: 189.

Chart 1.

Vaccination status. Unvaccinated: 74; Partially or fully vaccinated or boosted: 111; Non-responders: 4; Total: 189.

Chart 2.

Physical and mental health self-rating.

Chart 2.

Physical and mental health self-rating.

Chart 3.

Physical and mental health self-rating before Covid-19. Interpretation: Over one third (N; 66; 34.9%) of respondents rated their physical health, and nearly half (N; 84; 44.4%) of respondents rated their mental health as higher before Covid-19.

Chart 3.

Physical and mental health self-rating before Covid-19. Interpretation: Over one third (N; 66; 34.9%) of respondents rated their physical health, and nearly half (N; 84; 44.4%) of respondents rated their mental health as higher before Covid-19.

| Category |

Value |

N |

% |

| Age |

18-24 |

2/189 |

1.1% |

| 25 to 34 |

37/189 |

19.6% |

| 35 to 44 |

50/189 |

26.5% |

| 45 to 54 |

52/189 |

27.5% |

| 55 to 64 |

33/189 |

17.5% |

| 65 or older |

10/189 |

5.3% |

| Total respondents |

184/189 |

97.4% |

| No response |

5/189 |

2.6% |

| |

| Gender |

Woman |

159/189 |

84.1% |

| Man |

22/189 |

11.6% |

| Prefer not to answer |

2/189 |

1.1% |

| Total respondents |

184/189 |

97.4% |

| No response |

5/189 |

2.6% |

| |

|

Socioeconomic status (total household income and other non-employment sources of income) |

Very low-income |

1/189 |

0.5% |

| Low-income |

10/189 |

5.3% |

| Middle-income |

103/189 |

54.5% |

| High middle-income |

59/189 |

31.2% |

| High-income |

10/189 |

5.3% |

| Prefer not to answer |

1/189 |

0.5% |

| Total respondents |

184/189 |

97.4% |

| No Response |

5/189 |

2.6% |

| |

| Country of birth |

Canada |

163/189 |

86.2% |

| USA |

2/189 |

1.1% |

| Poland |

2/189 |

1.1% |

| UK |

2/189 |

1.1% |

| South Korea |

2/189 |

1.1% |

| South Africa |

3/189 |

1.6% |

| Other |

10/189 |

5.3% |

| Total respondents |

184/189 |

97.4% |

| No response |

10/189 |

5.3% |

| |

| Ethnic or Cultural Background |

Caucasian or White |

163/189 |

86.2% |

| Black |

1/189 |

0.5% |

| Indigenous |

11/189 |

5.8% |

| South Asian (Indian, Pakistani, Sri Lankan, etc.) |

2/189 |

1.1% |

| Chinese |

3/189 |

1.6% |

| Korean |

2/189 |

1.1% |

| Filipino |

4/189 |

2.1% |

| European |

3/189 |

1.6% |

| Other |

5/189 |

2.6% |

| No response |

5/189 |

2.6% |

| |

| Domestic status |

Married or living with a partner |

135/189 |

71.4% |

| Single |

37/189 |

19.6% |

| Widow (er) |

5/189 |

2.6% |

| Other |

7/189 |

3.7% |

| Total respondents |

184/189 |

97.4% |

| No response |

5/189 |

2.6% |

| |

| Caretaking responsibilities |

Only Children / Stepchildren |

70/189 |

37.0% |

| Only Parents / Elderly relatives |

17/189 |

9.0% |

| Both Children / Stepchildren and Parents / Elderly Relatives |

29/189 |

15.3% |

| None |

66/189 |

34.9% |

| Other |

2/189 |

1.1% |

| No response |

5/189 |

2.6% |

| |

| Education level |

Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BScN) or Bachelor of Nursing (BN) |

75/189 |

39.7% |

| Other |

26/189 |

13.8% |

| Registered / Diploma Nurse (RN) or Licensed Practical Nurse (LPN) or Registered Practical Nurse (RPN) diploma |

24/189 |

12.7% |

| Doctor of Medicine (MD) |

18/189 |

9.5% |

| Nursing Assistant Diploma |

8/189 |

4.2% |

| Master of Science in Nursing (MScN) / Master of Nursing (MN) |

7/189 |

3.7% |

| Paramedical or Emergency Medical Technician (EMT) program |

5/189 |

2.6% |

| No response |

5/189 |

2.6% |

| Bachelor of Science (BSc) (General, Psychology, Kinesiology, Occupational Therapy, Psychiatric Nursing) |

3/189 |

1.6% |

| Bachelor of Arts |

3/189 |

1.6% |

| PhD (any field) |

3/189 |

1.6% |

| Bachelor of Physical Education |

2/189 |

1.1% |

| Bachelor of Science in Nutrition or Food Sciences / Dietetics |

2/189 |

1.1% |

| Master of Health Sciences (MHSc) |

2/189 |

1.1% |

| Master of Science in Occupational Therapy (MScOT) |

2/189 |

1.1% |

| Bachelor or advanced degree, Health Administration/ Systems Management (e.g., BHAD) |

2/189 |

1.1% |

| Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) diploma |

2/189 |

1.1% |

| Medical Laboratory Technology Diploma |

1/189 |

0.5% |

| Bachelor of Health Sciences (BHSc) |

1/189 |

0.5% |

| Bachelor of Social Work |

1/189 |

0.5% |

| Bachelor or Doctor of Pharmacy |

1/189 |

0.5% |

| Acupuncture diploma |

1/189 |

0.5% |

| Phytotherapy (herbal medicine) diploma |

1/189 |

0.5% |

| |

| Profession/area of occupation |

Registered nurse/ Registered psychiatric nurse |

84/189 |

44.4% |

| In clinical practice |

47/189 |

24.9% |

| Licensed practical nurse |

17/189 |

9.0% |

| General practitioner/ Family physician |

15/189 |

7.9% |

| Other |

12/189 |

6.3% |

| Academic appointment/ University affiliation |

11/189 |

5.8% |

| Nurses aide/ Orderly/ Patient services associate (e.g., health care aide, long-term care aide, nursing assistant) |

8/189 |

4.2% |

| Medical technologist/ Technician (e.g., medical laboratory technologist, respiratory therapist) |

7/189 |

3.7% |

| Paramedical occupation (e.g., EMT, ambulance attendant, advanced care paramedic) |

6/189 |

3.2% |

| Not in clinical practice |

5/189 |

2.6% |

| No response |

5/189 |

2.6% |

| Specialist physician |

4/189 |

2.1% |

| Allied primary health practitioner (e.g., nurse practitioner, midwife, physician assistant) |

3/189 |

1.6% |

| Occupational therapist or Occupational therapy Assistant (OTA) |

3/189 |

1.6% |

| Pharmacist or Registered Pharmacy Technician |

3/189 |

1.6% |

| Nursing Coordinator/ Supervisor |

2/189 |

1.1% |

| Dietician/ Nutritionist |

2/189 |

1.1% |

| Natural healing practitioner (e.g. acupuncturist, traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) practitioner) |

2/189 |

1.1% |

| Dental care - technical occupation (e.g., dental hygienist, denturist, dental assistant) |

2/189 |

1.1% |

| Health profession student |

1/189 |

1.1% |

| Social Worker |

1/189 |

0.5% |

| Physiotherapist or Physiotherapy Assistant (PTA) |

1/189 |

0.5% |

| |

| Years of experience in most recent career |

0-5 years |

23/189 |

12.1% |

| 6-10 years |

33/189 |

17.5% |

| 11-15 years |

38/189 |

20.1% |

| 16-20 years |

27/189 |

14.3% |

| 21-25 years |

17/189 |

9.0% |

| 26-30 years |

20/189 |

10.6% |

| 31-35 years |

12/189 |

6.3% |

| 36-39 years |

6/189 |

3.2% |

| 40+ years |

7/189 |

3.7% |

| Total respondents |

183/189 |

96.8% |

| No response |

6/189 |

3.2% |

| |

| Years of education/training |

0-4 years |

65/189 |

34.4% |

| 5-9 years |

70/189 |

37.0% |

| 10+ years |

49/189 |

25.9% |

| Total respondents |

184/189 |

97.4% |

| No response |

5/189 |

2.6% |

| |

| Alberta health affiliation |

Central Zone: Code 4833 |

62/189 |

32.8% |

| Edmonton Zone: Code 4834 |

51/189 |

27.0% |

| Calgary Zone: Code 4832 |

49/189 |

25.9% |

| North Zone: Code 4835 |

29/189 |

15.3% |

| South Zone: Code 4831 |

8/189 |

4.2% |

| No response |

184/189 |

6% |

| Other |

1/189 |

0.5% |

| |

| Employment status |

Employed full-time |

74/189 |

39.2% |

| Employed part-time |

66/189 |

34.9% |

| Self-employed |

17/189 |

9.0% |

| Casual |

16/189 |

8.5% |

| Contractor |

3/189 |

1.6% |

| Travel nurse |

1/189 |

0.5% |

| Retired |

4/189 |

2.1% |

| Unemployed |

4/189 |

2.1% |

| Other |

1/189 |

0.5% |

| No response |

5/189 |

2.6% |

Table 2.

Vaccination decision and experience. Some answers allow for multiple options, so totals do not always amount to 100%.

Table 2.

Vaccination decision and experience. Some answers allow for multiple options, so totals do not always amount to 100%.

| Question |

Options |

N |

% |

Primary reason for getting vaccinated

|

To protect myself from severe outcomes (e.g., severe disease, hospitalization, death) |

37/111 |

33.3% |

| It was mandated at work |

33/111 |

29.7% |

| To protect the larger community from severe outcomes (e.g., severe disease, hospitalization, death) |

18/111 |

16.2% |

| To protect my loved ones from severe outcomes (e.g., severe disease, hospitalization, death) |

15/111 |

13.5% |

| It was mandated at school/ university |

2/111 |

1.8% |

| It was mandated for travel (e.g., visiting family or vacations) |

1/111 |

0.9% |

| I did it to avoid rejection from friends/ family members/ members of the community |

1/111 |

0.9% |

| It was mandated at social venues (e.g., restaurants) |

0/111 |

0% |

| It was mandated to visit vulnerable loved ones (e.g., grandparent in nursing home) |

0/111 |

0% |

| It was mandated at places of worship (e.g., church, temple, mosque) |

0/111 |

0% |

| Other |

3/111 |

2.7% |

| Total respondents |

110/111 |

99.1% |

| |

| Recommended the vaccine (if vaccinated) |

Family members / relatives |

70/111 |

63.1% |

| Friends and acquaintances |

61/111 |

55.0% |

| People I did not know |

3/111 |

2.7% |

| I did not recommend it |

31/111 |

27.9% |

| Other |

4/111 |

3.6% |

| Prefer not to answer |

6/111 |

5.4% |

| No response |

1/111 |

0.9% |

| |

Vaccine side effects (if vaccinated)

|

N/A (no reactions ever) |

41/111 |

36.9% |

| Mild reaction after 1st dose |

32/111 |

28.8% |

| Mild reaction after 2nd dose |

34/111 |

30.6% |

| Mild reaction after 3rd or later dose |

0/111 |

0% |

| Moderate reaction after 1st dose |

7/111 |

6.3% |

| Moderate reaction after 2nd dose |

11/111 |

10.0% |

| Moderate reaction after 3rd or later dose |

2/111 |

1.8% |

| Severe reaction after 1st dose |

6/111 |

5.4% |

| Severe reaction after 2nd dose |

3/111 |

2.7% |

| Severe reaction after 3rd or later dose |

3/111 |

2.7% |

| Life-threatening after 1st dose |

0/111 |

0% |

| Life-threatening after 2nd dose |

0/111 |

0% |

| Life-threatening after 3rd dose or later dose |

0/111 |

0% |

| Other |

2/111 |

1.8% |

| No response |

1/111 |

0.9% |

| |

Communicated adverse reactions to GP / family doctor or other medical personnel

|

N/A (no adverse reaction) |

54/111 |

48.6% |

| No, I did not communicate my reaction to GP / other medical personnel |

38/111 |

34.2% |

| Yes, I communicated my reaction to GP / other medical personnel, and they filed a report |

6/111 |

5.4% |

| Yes, I communicated my reaction to GP / other medical personnel, but they did not file a report |

5/111 |

4.5% |

| Yes, I communicated my reaction to GP / other medical personnel, and I do not know if they filed a report |

6/111 |

5.4% |

| Other |

1/111 |

0.9% |

| Total respondents |

110/111 |

99.1% |

| No response |

1/111 |

0.9% |

| |

| Experienced an adverse reaction after Covid-19 vaccine and still required to take additional doses |

Yes |

14/111 |

12.6% |

| No |

96/111 |

86.5% |

| Prefer not to answer |

0/111 |

0% |

| Total respondents |

110/111 |

99.1% |

| No response |

1/111 |

0.9% |

Table 3.

Accommodations, EDI considerations & informed consent.

Table 3.

Accommodations, EDI considerations & informed consent.

| Question |

Options |

N |

% |

| Employer or regulatory authorities offered alternatives to vaccination |

Yes, testing on site paid for by employer |

18/189 |

9.5% |

| Yes, test off site at your cost |

19/189 |

10.1% |

| Yes, remote work |

1/189 |

0.5% |

| Yes, educational training |

0/189 |

0% |

| Yes, proof of natural immunity |

1/189 |

0.5% |

| No, they did not offer any alternatives to vaccination |

145/189 |

76.7% |

| Total respondents |

184/189 |

97.4% |

| No response |

5/189 |

2.6% |

| |

| Requested exemption from vaccination |

N/A (e.g., my employer did not request mandatory vaccination and I did not need an exemption) |

9/189 |

4.8% |

| No, I was not interested in requesting an exemption |

74/189 |

39.2% |

| Yes, and I received an exemption |

3/189 |

1.6% |

| Yes, but I did not receive an exemption |

46/189 |

24.3% |

| No, I did not request an exemption (e.g., because I was intimidated to ask for one) |

36/189

|

19.1% |

| Other |

16/189 |

8.5% |

| No response |

5/189 |

2.6% |

| |

| Category of exemption |

N/A (did not apply for exemption) |

132/189 |

69.8% |

| Medical |

16/189 |

8.5% |

| Religious |

40/189 |

21.2% |

| Conscientious |

12/189 |

6.3% |

| Other |

4/189 |

2.1% |

| No response |

5/189 |

2.6% |

| |

Employer (or professional college or public health authority if self-employed) provided written information about the vaccines

|

Yes, I was provided a package insert from the vaccine manufacturer(s) |

15/189 |

7.9% |

| Yes, I was provided information from public health agencies or equivalent |

60/189 |

31.8% |

| No, they never provided me with written information about the vaccines |

111/189 |

58.7% |

| Other |

9/189 |

4.8% |

| No response |

5/189 |

2.6% |

| |

| If you received written information from your employer (or professional college or public health authority if self-employed) did it enable you to make an informed decision about vaccination? |

Yes |

46/189 |

24.3% |

| No |

29/189 |

15.3% |

| I did not receive written information |

104/189 |

55.0% |

| Other |

5/189 |

2.6% |

| Total respondents |

184/189 |

97.4% |

| No response |

5/189 |

2.6% |

Table 4.

Level of agreement with statements on vaccination requirements & impact on employment status and conditions. Only respondents who replied “yes/prefer not to answer” to the question confirming whether or not they were terminated from their job were included in this table.

Table 4.

Level of agreement with statements on vaccination requirements & impact on employment status and conditions. Only respondents who replied “yes/prefer not to answer” to the question confirming whether or not they were terminated from their job were included in this table.

| Statement |

Strongly disagree (N; %) |

Disagree

(N; %) |

Neutral

(N; %) |

Agree

(N; %) |

Strongly agree

(N; %) |

N. A |

No response |

I experienced conflict among colleagues at work after the introduction of vaccines and/or vaccination policies

|

19/189; 10.1% |

23/189; 12.2% |

16/189; 8.5% |

43/189; 22.8% |

78/189; 41.3% |

5/189; 2.6% |

5/189; 2.6% |

I experienced conflict between employees and management at work after the introduction of vaccines and/or vaccination policies

|

21/189; 11.1% |

30/189; 15.9% |

13/189; 6.9% |

37/460; 19.6% |

73/189; 38.6% |

10/189; 5.3% |

5/189; 2.6% |

I know of health workers who have taken early retirement due to Covid-19 policies

|

27/189; 14.3% |

14/189; 7.4% |

11/189; 5.8% |

39/189; 20.6% |

84/189; 44.4% |

9/189; 4.8% |

5/189; 2.6% |

I know of health workers who have been laid off due to failure to comply with vaccination

|

28/189; 14.8% |

16/189; 8.5% |

7/189; 3.7% |

33/189; 17.5% |

92/189; 48.6% |

8/189; 4.2% |

5/189; 2.6% |

I know of health workers who have resigned because they did not wish to take the vaccine

|

22/189; 11.6% |

11/189; 5.8% |

11/189; 5.8% |

37/189; 19.6% |

94/189; 49.7% |

9/189; 4.8% |

5/189; 2.6% |

| I know of students in the health professions who were deregistered due to non-compliance with vaccination policies |

46/189; 24.3% |

20/189; 10.6% |

18/189; 9.5% |

20/189; 10.6% |

47/189; 24.9% |

33/189; 17.5% |

5/189; 2.6% |

| I would return to my previous role if possible/ if mandates were dropped (Only respondents who replied “yes/prefer not to answer” to the question confirming whether or not they were terminated from their job were included in this table) |

16/61; 26.2% |

2/61; 3.3% |

2/61; 3.3% |

10/61; 16.4% |

9/61; 14.8% |

22/61; 36.1% |

0/61 ; 0% |

I intend to leave my occupation/ the healthcare sector/industry due to my experiences with the Covid-19 policy response

|

62/189; 32.8% |

44/189; 23.3% |

26/189; 13.8% |

18/189; 9.5% |

22/189; 11.6% |

12/189; 6.3% |

5/189; 2.6% |

Table 5.

Personal and family impact of vaccination policies. Only respondents who replied “yes/prefer not to answer” to the question confirming whether or not they were terminated from their job were included in this table.

Table 5.

Personal and family impact of vaccination policies. Only respondents who replied “yes/prefer not to answer” to the question confirming whether or not they were terminated from their job were included in this table.

| Statement |

Strongly disagree (N; %) |

Disagree

(N; %) |

Neutral

(N; %) |

Agree

(N; %) |

Strongly agree

(N; %) |

N. A |

No response |

| My income is less than it was prior to the introduction of vaccination policies / mandates |

63/189; 33.3% |

48/189; 25.4% |

29/189; 15.3% |

14/189; 7.4% |

18/189; 9.5% |

12/189; 6.3% |

5/189; 2.6% |

| Losing my job significantly reduced my income |

4/61;

6.6% |

0/61; 0% |

2/61; 3.3% |

12/61; 19.7% |

33/61; 54.1% |

10/61; 16.4% |

0/61; 0% |

| I have suffered chronic physical ailments due to employer vaccination requirements |

73/189; 38.6% |

32/189; 16.9% |

16/189; 8.5% |

8/189; 4.2% |

12/189; 6.3% |

43/189; 22.8% |

5/189; 2.6% |

| I have suffered physical disability due to employer vaccination requirements |

80/189; 42.3% |

37/189; 19.6% |

11/189; 5.8% |

4/189; 2.1% |

5/189;

2.6% |

47/189; 24.9% |

5/189; 2.6% |

| I have suffered anxiety and/ or depression due to employer vaccination requirements |

64/189; 33.9% |

22/189; 11.6% |

16/189;

8.5% |

22/189; 11.6% |

49/189; 25.9% |

11/189; 5.8% |

5/189; 2.6% |

| I have experienced suicidal thoughts due to employer vaccination requirements |

96/189; 50.8% |

34/189; 18.0% |

15/189; 7.9% |

5/189; 2.6% |

9/189; 4.8% |

25/189; 13.2% |

5/189; 2.6% |

| I have sought help from a counsellor due to situations arising from vaccination requirements |

75/189; 39.7% |

28/189; 14.8% |

15/189; 7.9% |

16/189; 8.5% |

25/189; 13.2% |

25/189; 13.2% |

5/189; 2.6% |

| My personal relationships (spouses, friends) suffered due to situations arising from vaccination requirements |

54/189; 28.6% |

22/189; 11.6% |

15/189; 7.9% |

25/189; 13.2% |

64/189; 33.9% |

4/189; 2.1% |

11/189; 5.8% |

| I feel I have been unfairly treated by my employer regarding vaccination requirements. |

62/189; 32.8% |

14/189; 7.4% |

13/189; 6.9% |

15/189; 7.9% |

74/189; 39.1% |

6/189; 3.2% |

5/189; 2.6% |

| Losing my job had a negative impact on my physical health |

1/61;

1.6% |

6/61; 9.8% |

9/61; 14.8% |

17/61; 27.9% |

18/61; 29.5% |

10/61; 16.4% |

0/61; 0% |

| Losing my job had a negative impact on my mental health |

3/61;

4.9% |

2/61; 3.3% |

2/61; 3.3% |

13/61; 21.3% |

31/61; 50.8% |

10/61; 16.4% |

0/61; 0% |

Table 6.

Vaccination requirements & impact on employment status and conditions.

Table 6.

Vaccination requirements & impact on employment status and conditions.

| Question |

Options |

N |

% |

| Terminated or laid off due to the decision to not receive the Covid-19 vaccine (first or subsequent doses)? |

Yes |

48/189 |

25.4% |

| No |

123/189 |

65.1% |

| Prefer not to answer |

13/189 |

6.9% |

| Total respondents |

184/189 |

97.4% |

| No response |

5/189 |

2.6% |

| |

| Subject to disciplinary measures other than layoffs (e.g., accusations of “professional misconduct”; reports to licensing colleges; temporary suspension of pay; exclusion from pension plan; withdrawal of professional license). |

Yes |

37/189 |

19.6% |

| No |

123/189 |

65.1% |

| Prefer not to answer |

5/189 |

2.6% |

| Other |

19/189 |

10.1% |

| No response |

5/189 |

2.6% |

| |

| Rehired in Alberta after being terminated in another province (e.g., BC) for refusing to accept mandated vaccination entirely or in part |

Yes |

10/189 |

5.3% |

| No |

139/189 |

73.5% |

| Prefer not to answer |

6/189 |

3.2% |

| Other |

27/189 |

14.3% |

| Total respondents |

182/189 |

96.3% |

| No response |

7/189 |

3.7% |

Table 7.

Level of agreement with statements on vaccine concerns & informed consent.

Table 7.

Level of agreement with statements on vaccine concerns & informed consent.

Statement

Level of agreement with the following related to the decision on Covid-19 vaccines |

Strongly disagree (N; %) |

Disagree

(N; %) |

Neutral

(N; %) |

Agree

(N; %) |

Strongly agree (N; %) |

N. A

(N; %) |

No response |

| I felt entirely free to choose whether or not to get vaccinated |

99/189; 52.4% |

28/189; 14.8% |

8/189;

4. 2%

|

17/189; 9.0% |

31/189; 16.4%

|

1/189; 0.5% |

5/189; 2.6% |

| I had safety concerns with the Covid-19 vaccines |

38/189; 20.1% |

17/189; 9.0% |

14/189; 7.4% |

14/189; 7.4% |

100/189; 52.9% |

1/189; 0.5% |

5/189; 2.6% |

| I had personal medical concerns with the Covid-19 vaccines (e.g., I have an autoimmune disorder) |

53/189; 28.0% |

28/189; 14.8% |

19/189; 10.1% |

20/189; 10.6% |

41/189; 21.7% |

23/189; 12.2% |

5/189; 2.6% |

| I had religious concerns with the Covid-19 vaccines. |

67/189; 35.4% |

18/189; 9.5% |

19/189; 10.1% |

14/189; 7.4% |

51/189; 27.0% |

15/189; 7.9% |

5/189; 2.6% |

| I felt comfortable expressing safety concerns about the Covid-19 vaccines with my employer |

85/189; 45.0% |

17/189; 9.0% |

16/189; 8.5% |

14/189; 7.4% |

21/189; 11.1% |

31/189; 16.4% |

5/189; 2.6% |

| I did my own research to determine the safety and efficacy of the Covid-19 vaccines |

7/189; 4% |

6/189; 3.2% |

8/189; 4.2% |

42/189; 22.2% |

116/189; 61.4% |

5/189; 2.6% |

5/189; 2.6% |

Table 8.

Impact on patient care.

Table 8.

Impact on patient care.

| Question |

Options |

N |

% |

| Worked with Covid-19 positive or suspected patients’ pre-vaccine mandate |

Yes |

150/189 |

79.4% |

| No |

16/189 |

8.5% |

| Not sure |

18/189 |

9.5% |

| Other |

0/189 |

0% |

| Total respondents |

184/189 |

97.4% |

| No response |

5/189 |

2.6% |

| Encouraged to report adverse events post vaccination if observed |

Yes |

78/189 |

41.3% |

| No |

106/189 |

56.1% |

| Total respondents |

184/189 |

97.4% |

| No response |

5/189 |

2.6% |

| Trained to report adverse events post-vaccination if observed |

Yes |

82/189 |

43.4% |

| No |

102/189 |

54.0% |

| Total |

184/189 |

97.4% |

| No response |

5/189 |

2.6% |

Asked, encouraged, or coerced to minimize vaccine hesitancy by:

|

Not providing exemptions when requested by patients |

17/189 |

9.0% |

| Not prescribing off label prescriptions |

15/189 |

7.9% |

| Telling patients that the vaccines were safe and effective |

63/189 |

33.3% |

| Encouraging patients to trust health officials and sources |

63/189 |

33.3% |

| Dismissing non-officially approved information as ‘misinformation’ |

48/189 |

25.4% |

| I was not asked to do any of these things |

95/189 |

50.3% |

| Other |

5/189 |

2.6% |

| Prefer not to answer |

16/189 |

8.5% |

| No response |

7/189 |

3.7% |

| Personally administered Covid-19 vaccines |

Yes |

30/189 |

15.9% |

| No |

154/189 |

81.5% |

| Total respondents |

184/189 |

97.4% |

| No response |

5/189 |

2.6% |

| If administered Covid-19 vaccines, received compensation |

Yes |

10/30 |

33.3% |

| No |

18/30 |

60.0% |

| Other |

2/30 |

6.7% |

| Total Respondents |

30/30 |

100% |

| No response |

0/30 |

0% |

| Feeling upon administering Covid-19 vaccines |

Accepting; it was part of my responsibility |

14/30 |

46.7% |

| Energized; I was part of the solution for a serious public health problem |

18/30 |

60.0% |

| Uneasy; I did not know what might happen to vaccine recipients |

17/30 |

56.7% |

| Other |

3/30 |

10.0% |

| Prefer not to answer |

0/30 |

0% |

| Total respondents |

0/30 |

0% |

| No response |

14/30 |

46.7% |

Table 9.

Level of agreement with statements on impact on patient care.

Table 9.

Level of agreement with statements on impact on patient care.

| |

|---|

| Statement |

Strongly disagree (N; %) |

Disagree

(N; %) |

Neutral

(N; %) |

Agree

(N; %) |

Strongly agree (N; %) |

N. A |

No response |