1. Introduction

Physical activity (PA) is recognized as a key factor in the growth and development of children [

1]. In young children, PA provides numerous benefits, including maintaining a healthy weight, regulating blood pressure, developing motor skills, and improving psychological well-being [

2]. The prevalence of overweight and obesity among children is an increasing public health concern in Tunisia [

3,

4]. A study conducted in the metropolitan area of Tunis reported that 19.7% of elementary schoolchildren were overweight, and 5.7% were obese [

5]. Moreover, excessive consumption of bread, snacks, and sugary drinks, as well as insufficient physical activity, were identified as contributing factors to overweight and obesity among school-aged children [

5]. However, further studies are needed to confirm the relevance of these findings for preschool-aged children [

4].

In 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) established guidelines for PA in children under 5 years, emphasizing the importance of adherence for healthy growth [

6]. In Tunisia, where childhood overweight is on the rise, the international study of movement behaviors (SUNRISE) study assessed compliance with these guidelines regarding activity, sedentary behavior, and sleep [

7]. The findings highlight the urgent need to promote healthy behaviors from preschool age, integrating PA and reducing screen time into public health initiatives [

4]. Indeed, numerous studies, driven by advances in neuroscience and embodied cognitive science have examined the impact of PA programs (PAP) on children’s cognitive functions [

8,

9,

10,

11]. The majority of these research highlighted positive correlations between PA and improved cognitive abilities in children [

8,

12,

13].

Executive function (EF) refers to the advanced cognitive ability to coordinate and regulate a set of cognitive processes in order to achieve a specific goal [

14] . EF in preschool children is a key component of their individual development, as it can influence their future academic success [

15] and social interaction skills [

16]. Recent studies have shown that PA interventions can have beneficial effects on children’s EF [

17,

18,

19]. Experimental research indicates that both acute and chronic aerobic exercises can effectively improve EF in children [

20]. However, these findings have yet to be generalized to school or other natural environments, whether urban or rural [

3], or across different gender (boys and girls), particularly for preschool-aged children. Furthermore, research suggests that not all forms of PA equally promote EF [

20].

Mavilidi et al. (2015) [

21] reported that children participating in a 4-week foreign language vocabulary program incorporating PA achieved better learning outcomes than those in a traditional learning setting [

21]. Further research is needed to strengthen the evidence on the effects of different PA practices on the development of EF, particularly during early childhood. Trampoline, often referred to as "air ballet," is a form of gymnastics that is very popular among preschool children in China [

22]. This activity involves acrobatic movements as children bounce on the trampoline, requiring constant adjustments in posture to adapt to changes in gravity with each jump [

22]. It is a motivating practice for young children, combining enjoyment with motor skill development, creating an engaging and dynamic learning experience [

22]. Trampoline activities have notable effects on children's sensory organs and nervous system, enhancing aspects such as spatial awareness, vision, proprioception, and motor control as well as on their physical fitness, including strength, balance, and coordination [

23,

24]. Previous studies have shown that a 12-week trampoline training program, with individualized daily sessions of 20 minutes, can significantly improve motor skills and balance in school-aged children [

23,

24]. Moreover, mini-trampoline exercises offer a multi-faceted approach that positively impacts physical conditioning aspects such as balance, flexibility, and strength [

23,

24], as well as enhancing muscle coordination and spatial awareness [

22]. Performing exercises on a flexible surface like a mini-trampoline may also reduce neuromuscular stress, potentially lowering the risk of injury [

25], while simultaneously improving postural stability and jump performance [

25,

26] These characteristics make mini-trampoline exercises both beneficial and safe for younger children [

27].

Trampoline exercises, popular among preschool children [

24], are considered an ideal activity for enhancing both EFs and motor development. Given the limited research focusing on Tunisian children under five that simultaneously evaluates cognitive and motor skills, this study aimed to fill this gap and contribute to the global understanding of PA's benefits. Specifically, the objective was to assess the effects of a mini-trampoline PA program on EF (e.g., attention, inhibitory control) and motor skills (e.g., balance, coordination) in Tunisian preschoolers. The hypothesis was that such a program will significantly improve both EF and motor development, offering an engaging solution to support healthy growth in the context of rising childhood overweight trends.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

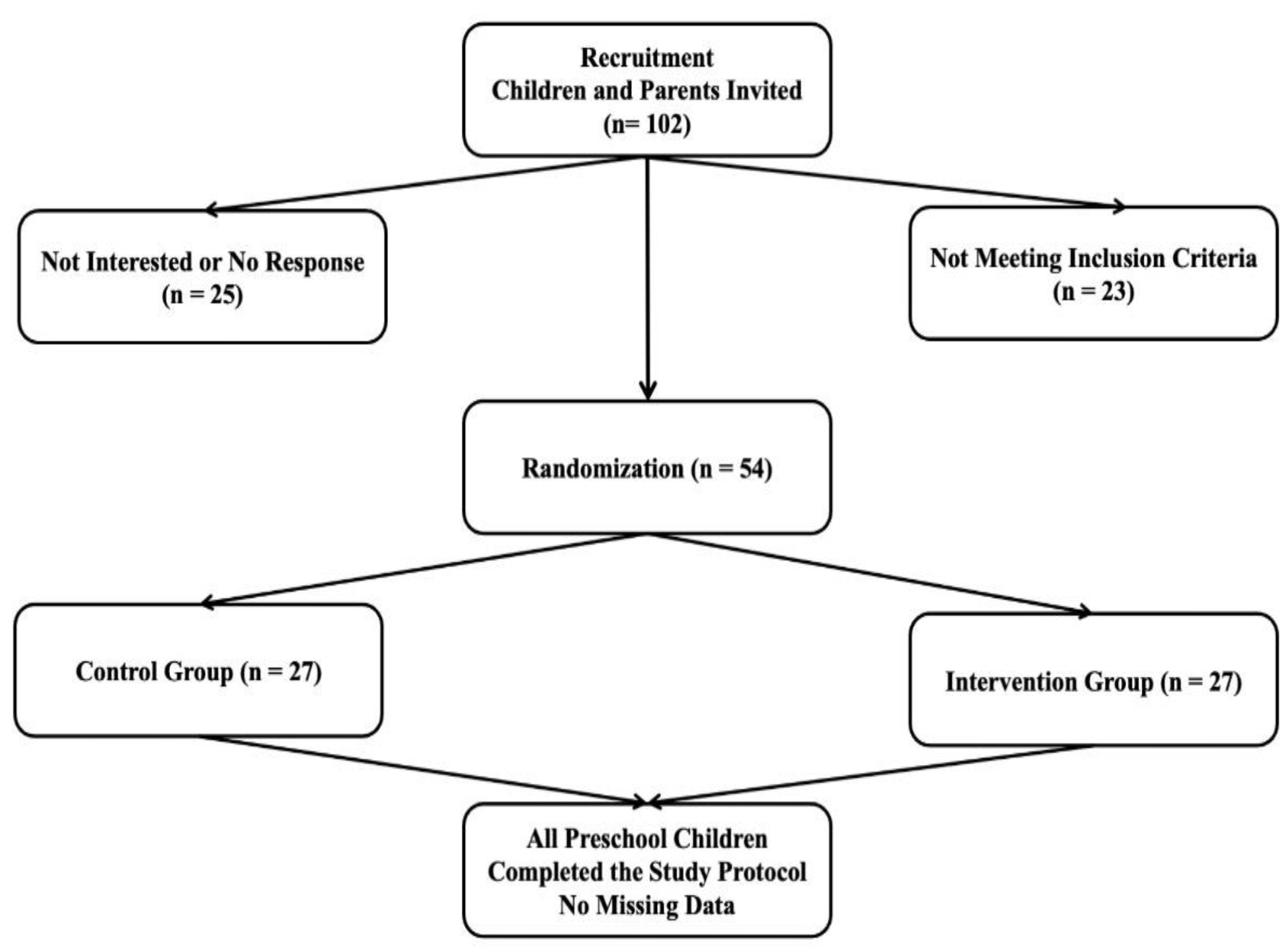

As illustrated in

Figure 1, the eligibility of preschool children was assessed, with a total of 102 children evaluated for participation in the study. Among them, 25 parents refused to allow their children to participate, and 23 children did not meet the inclusion criteria. In total, 54 children (26 boys and 28 girls) with a mean age of 3.87 ± 0.47 years were included in the study. The children were randomly assigned to either the experimental group (27 children; 14 boys) or the control group (27 children; 12 boys) using a random number generator.

2.2. Participants

Participants included fifty-four preschool children (age 3.87 ± 0.47 years; body mass 14.66 ± 2.58 kg; stature: 106 ± 6 cm). Participants in this study were recruited from a nursery school École La Fontaine, located in the El Menzah 7 district of Tunis, Tunisia, for this study. The inclusion criteria for the children were strict, allowing only those without psychological or mental disorders or physical disabilities. This ensured that the study groups were comparable at the start of the trial. An introductory meeting was held with the school's physical education teachers and the children's parents to explain the research objectives and the procedures. Parents provided informed consent by signing a written form after being informed of the potential risks and benefits of the study. Parents also completed a detailed questionnaire regarding their children's mental and physical health.

Participants were allocated into two groups (control group: age 3.99 ± 0.45 years; experimental group: age 3.76 ± 0.47 years) using simple randomization through a coin toss between the two groups. To maintain the confidentiality of the randomization, the process was carried out by an independent researcher not involved in the study. While the control group followed standard PAs, the experimental group was engaged in rebound exercises on a mini-trampoline. Descriptive data for the participants as age and anthropometric characteristics were presented in

Table 1.

The participants contributed in a 12-week intervention, with assessments conducted before and after the program. They were tested twice in a pre-test followed by a post-test to measure motor skills as functional mobility (FM), postural steadiness (PS), upper and lower balance stability, work memory, Dexterity’s inhibition, work memory and inhibitory control.

2.3. Ethical Approval

All procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of Sousse (CEFMS 121/2022). Written consent from parents and assent from participants were obtained before the study began. All participants, along with their parents or legal representatives, were fully informed about the study protocol and the potential risks and benefits involved.

2.4. Training Program: General Warm-Up and Mini-Trampoline Program

The interventions were performed after a general 10-minute general warm-up, followed by a 20 minutes mini-trampoline exercises session (

Table 2).

The mini-trampoline training program, designed exclusively for the experimental group, features simple exercises tailored to the motor abilities of preschool children. Activities such as basic jumps with either feet, or coordinated arm movements are easy to perform and progressively evolve into more complex exercises, such as jumps with rotations, respecting the children’s capacity for gradual learning [

22,

23]. Short recovery periods (15 to 60 seconds) prevent excessive fatigue while maintaining participant engagement [

25]. This program aligns with the physiological characteristics of children under five years old and adheres to fundamental training principles [

28]. By promoting overall motor development, coordination, and balance, it ensures an age-appropriate, safe, and progressive approach that enhances skills without imposing undue stress [

22,

23].

2.5. Testing Procedures

2.5.1. Anthropometry

Anthropometric measurements involved using repositionable adhesive measuring tapes to assess children's height, accurate to 0.1 cm. Each height measurement was repeated twice, and if there was a discrepancy greater than 0.5 cm between the two readings, a third measurement was taken using the same method. Children's weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg on a calibrated SECA 750 Viva scale (Hamburg, Germany), with a third reading required if the initial two differed by more than 0.25 kg. Measurements were conducted with children in light clothing and without shoes to ensure accuracy. Body mass index (kg/m²) was then calculated from height and weight, based on WHO reference standards [

29].

2.5.2. Executive Function

Inhibition and WM (WM), two key indicators of cognitive function, were assessed using the early years toolbox [

30]. The French version of the games was translated verbatim into Arabic by a field worker, who was also a physical education teacher. A forward translation method was used to ensure accurate adaptation of the content. The translated versions had been previously used [

4], confirming their acceptability and understandable for the target group. The primary goal was for children to understand the task requirements during the practice phase. Each game took approximately 10 minutes to complete. EF tests assessed children’s behavioral impulse control and inhibition (Go/No-Go) and visuospatial WM [

30]. The research assistant explained each game, which included a built-in practice period at the start. The tasks were performed in a quiet environment.

2.5.3. Lower Body Strength (LBS) and Mobility: Standing Long Jump

In this test, a line is marked on the ground, and the child stands behind it. The child then jumps forward with both feet as far as possible. One practice jump is allowed, followed by two official attempts. The final score is calculated as the average of the recorded distances from the two attempts [

31].

2.5.4. Mobility and Posture: Supine-Timed Up And go

In this test, a line is drawn three meters from a wall, and a large target is marked on the wall at the child’s eye level. The child starts lying on their back with their feet on the line. At the signal, the child gets up as quickly as possible, runs to touch the target, then runs back to the line. One practice trial is allowed, followed by two official attempts.

2.5.5. One-Leg Standing Balance Test

In this test, the child stands on one leg with their arms alongside their body. The free leg must not touch or wrap around the standing leg, though the arms can move for balance. Timing starts when the free leg lifts off the floor. The test is stopped if the child moves the standing leg or hooks the free leg around it. If the child maintains balance for 30 seconds, the test was repeated on the other leg. The time balanced on each leg was recorded, and the average time is used as the final score [

31].

2.5.6. Upper Body Strength (UBS): Hand Grip Dynamometer

This test assesses the ability of the hand and arm muscles to generate the tension and strength needed to maintain posture [

31]. During the test, the child must squeeze the grip dynamometer with maximum force using their right hand for at least 3 seconds, ensuring that their arm does not touch their body. One practice trial and two test trials are performed with each hand.

2.5.7. Manipulation: 9-Hole Peg-Board Test

This test evaluates the speed and accuracy of hand movements by having the child pick up nine pegs one by one, place them into a pegboard, and then remove them. Timing starts when the child begins the task and stops when the last peg is removed. The child should use the non-tested hand to stabilize the board, and the evaluator may also help by placing their hand on the child’s hand for added stability. The child completes two trials and two practice sessions, one with each hand. This test has proven to be reliable and valid for assessing fine motor skills in children [

31].

2.6. Questionnaire

The questionnaire was given to the child’s parent or guardian (n = 54) and asked about the child’s usual sleep patterns, including sleep duration based on nighttime sleep. It also covered dietary diversity, eating habits, and household food insecurity. Socio-demographic information was collected using an adapted version of the WHO STEPS survey [

32]. Questions about children's movement behaviors were based on the 2017 Australian 24-hour movement behavior guidelines for early years [

31].

2.6.1. Center Information Questionnaire

The center information questionnaire was conducted through interviews with the kindergarten director. Like the parent and director questionnaires, the data collector read each question aloud, and participants gave verbal responses, which were recorded and entered directly into the questionnaire. The questionnaire collected information on the total number of eligible children at the center those who consented to participate, and the timing of the daily nap.

2.7. Exercise Intervention

The study was conducted in three phases: (i) a pre-test evaluating EF and motor development, (ii) a 12-week intervention, and (iii) a post-test assessing EF and motor development. First, a pre-test was administered to evaluate the children’s baseline EF and motor development before the intervention. Over the following 12 weeks, both control and experimental groups attended the same classes and daycare services in kindergarten but engaged in different activities. The control group followed the usual PA program, while the experimental group participated in rebound exercises on a mini-trampoline. At the end of the 12-week intervention, a post-test assessing EFs and motor development was realized using the same tools as the pre-test. This post-test aimed to measure the impact of the intervention on EFs, motor development, and cognitive skills in preschool children.

For the experimental group, the sessions consisted of three weekly rebound exercise sessions, lasting between 10 and 30 minutes each, over the 12-week period. Each session began with a 10-minute warm-up (

Table 2). The rebound exercises were conducted under the supervision of two qualified physical education teachers, with each child using a personal mini-trampoline surrounded by safety nets. Additionally, two female supervisors, as required by the kindergarten’s internal regulations, were present to ensure the safety of the preschool-aged children. Safety recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatrics (1999) [

33] were followed to prevent injuries.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS Statistics (Version 26) for Windows (SPSS, Inc., USA, IBM Corp) and expressed as means ± standard deviations. The analysis assessed within-group and between-group differences for the experimental and control groups across various motor and EF measures before and after the intervention. The normality of data distribution was verified using the Shapiro-Wilk test (

p < 0.05), and sphericity was assessed using Mauchly’s Test. Homogeneity of variances was tested with Levene’s Test. A two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (2×2; group×time) was used to evaluate the effects of the intervention on each parameter. Post-hoc comparisons were conducted where necessary to further explore significant interactions. Statistical significance was set at

p < 0.05. The effect size was reported as Cohen's

d for within-group changes and partial eta squared (

ηp²) for ANOVA results to determine the magnitude of effects. Cohen’s

d was interpreted as small (0.2), medium (0.5), or large (0.8), while ηp² was classified as small (0.01 < ηp² < 0.06), medium (0.06 < ηp² < 0.14), or large (ηp² ≥ 0.14), based on Cohen’s guidelines [

34] .

The sample size for this study was calculated to ensure sufficient statistical power to detect within- and between-group differences in motor and EF measures. A two-way repeated measures ANOVA (Group × Time) was selected, with assumptions including a medium effect size (f = 0.25), an alpha level of 0.05, a power of 0.80, two groups (i.e.; experimental and control), and two measurements (i.e.; pre- and post-test). Using G*Power software (version 3.1.9.2, Heinrich Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany), the minimum required sample size was 34 participants (17 per group). To account for potential dropout or non-compliance, the target was increased by 20%, resulting in a required sample size of 42 participants. This study included 54 children (27 per group), exceeding the minimum required sample size and ensuring robust representation for assessing the intervention’s effects on age, anthropometric characteristics, and gross and fine motor skills.

3. Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive data for participants' demographic characteristics and PA manipulation in both control and experimental groups. The average age in the control group is slightly higher compared to the experimental group. In terms of gender distribution, girls represent a comparable proportion in both groups, with 55.56% in the control group and 48.15% in the experimental group (

Table 1). Children in the experimental group have a higher average body mass index compared to the control group.

The statistical analysis results reveal notable changes between pre- and post- measurements in the experimental and control groups. In the experimental group, significant improvements were observed in FM (p < 0.001), postural steadiness (p < 0.001), and LBS (p < 0.001) (

Table 3). In contrast, the control group demonstrated stability or marginal changes, particularly in LBS (p = 0.036). No significant improvements were observed in either group for UBS (experimental group: p = 0.787; control group: p = 0.425), dexterity (experimental group: p = 0.161; control group: p = 0.769), or WM (experimental group: p = 0.711; control group: p = 0.658). However, the experimental group exhibited a significant enhancement in inhibition (p < 0.001), while no change was observed in the control group (p = 0.230). These findings highlight the positive impact of the intervention on specific functional and motor abilities, particularly in the experimental group.

The results of the ANOVA group × time interaction reveal varying levels of significance and effect sizes across the measured variables. No significant interaction effects were observed for FM (p = 0.696, d = 0.063), UBS (p = 0.986, d = 0.00), dexterity (p = 0.988, d = 0.00), or WM (p = 0.943, d = 0.00), indicating minimal or no effect of the intervention in these areas. However, a marginal interaction was found for postural steadiness (p = 0.062, d = 0.369), suggesting a trend toward a significant effect. Similarly, LBS (p = 0.368, d = 0.179) and inhibition (p = 0.366, d = 0.179) showed moderate effect sizes but did not reach statistical significance. These findings reflect the nuanced impact of the intervention, with notable improvements in specific areas but no significant interaction effects when considering the group × time factor.

4. Discussion

The study revealed that the 12-week mini-trampoline exercise program significantly improved key motor skills such as FM, postural stability, and LBS, as well as inhibitory control of EFs in preschool children in Tunisia. However, the results of the group × time ANOVA interaction showed varying levels of significance and effect sizes (Cohen's d) across the measured variables. No significant interaction was observed for the majority of EFs and motor skills, but a marginal trend was noted for postural stability.

Numerous cross-sectional studies have investigated the relationship between PA and cognitive functions in both children and adults [

35,

36]. However, limited intervention studies have utilized PA, specifically rebound exercises on a mini-trampoline, to simultaneously enhance cognition and both gross and fine motor skills in preschool-aged children [

10,

37,

38]. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this study is among the limited interventions investigating the effects of PA, through rebound exercises on a mini-trampoline, on EF and motor development in Tunisian preschool children.

4.1. Effects of the 12-Week Mini-Trampoline Intervention on EFs

The observed improvement in inhibition within the experimental group aligns with findings suggesting that targeted PA programs can enhance inhibitory control, a core component of EFs [

20]. The significant improvement might reflect the impact of the intervention on attentional focus and self-regulation, skills often stimulated through structured PAs. However, the absence of a significant group × time interaction indicates that these gains may not be exclusively attributable to the intervention, highlighting the need for further exploration of confounding factors.

For WM, the lack of significant improvement in both groups is consistent with research indicating that this EF develops gradually and may require more extended and diverse interventions to show measurable changes in preschool-aged children [

39]. In the Tunisian context, this lack of effect may be attributed to several factors, such as the still-developing EFs in preschool-aged children, which require repeated and adapted activities to achieve noticeable improvements. Moreover, the short duration of the intervention and the possible lack of cognitive challenge in the tasks might have limited its impact on WM.

The results revealed an improvement in inhibition among young children after 12 weeks of trampoline training. However, the study did not show a positive effect of this training on WM. In the Tunisian context, this lack of effect may be attributed to several factors, such as the still-developing EFs in preschool-aged children, which require repeated and adapted activities to achieve noticeable improvements. Additionally, socio-cultural and educational conditions may also play a role, affecting children's ability to transfer acquired skills to more formal learning contexts [

4,

24]. Furthermore, the duration and intensity of PA are considered key moderators in the relationship between PA and cognitive functions [

24,

36].

The relatively short duration of the intervention in the present study (12 weeks) may not have been the primary reason for the lack of significant improvement in certain EFs. While some authors [

40], reported improvements in EF with an 8-week coordinative PA intervention (two 35-minute sessions per week), others [

36,

41] observed benefits with just 4 weeks of task-integrated activities. These findings highlight that the type, intensity, and structure of the PA play a crucial role.

It has been reported that high-intensity PA may further promote cognitive development in preschool children [

28]. A possible explanation for the lack of significant improvement in WM among Tunisian children in this study could be an insufficient intensity of PA to stimulate cognitive development [

28]. In fact, data from other studies involving trampoline exercises suggest that the intensity of trampoline training is unlikely to be the reason for the null results observed [

21,

27].

The type of PA is another key factor that can influence the effectiveness of an intervention. Over the past decade, the effects of various types of PA on EF have been explored [

10]. Indeed, some studies have shown that aerobic exercises and coordinated PA are beneficial for EF development in preschool children [

28,

40].

The positive effects of PA on EFs can be specific to the type of task, and the diversity in measurement methods presents challenges in consolidating the findings [

31,

36]. These tasks, specifically designed for children aged 3 to 5 years [

11,

42], are widely used to assess EF in young children in Western countries and China [

43,

44,

45].

Children in the experimental group showed a greater increase in scores on the Go/No-Go test compared to those in the control group, suggesting that PA may be especially beneficial for enhancing inhibitory control in Tunisian preschoolers. Additionally, these results indicate that trampoline activity is highly engaging for children, which may contribute to observed improvements in their ability to control impulses and respond thoughtfully [

24].

This study is the first in Tunisia to analyze the effects of mini-trampoline rebound exercises on preschoolers' EF, offering an original contribution to research for this age group. Further studies with larger samples are needed to confirm these findings and improve generalizability. Longitudinal and multi-center designs could also explore sustained effects and the influence of factors like socio-economic status, gender, and baseline motor skills.

4.2. Effects of the 12-Week Mini-Trampoline Intervention On Gross And Fine Motor Skills

The 12-week mini-trampoline intervention showed significant improvements in several aspects of gross motor skills in the experimental group compared to the control group. The most notable gains were observed in FM, PS, and LBS, highlighting the effectiveness of this specific PA. In contrast, no significant changes were observed in fine motor skills or UBS, with both groups remaining stable on these parameters. The results of the ANOVA group × time interaction revealed varying levels of significance across the measured variables. No significant interaction effects were observed for FM, UBS, dexterity, or WM, indicating that the intervention had minimal or no impact when considering the group × time interaction. However, a marginal interaction was noted for PS, showing a trend toward a significant effect. Similarly, LBS and inhibition showed moderate effect sizes but did not reach statistical significance.

The results of this study demonstrate the effectiveness of mini-trampoline exercises in improving certain gross motor skills, notably balance, mobility, and LBS. These improvements align with the findings of Giagazoglou et al. (2013) [

23] who reported significant gains in motor performance following a similar training protocol. Similarly, Arabatzi (2018) [

37] highlighted the crucial role of trampoline activities in physical development across various contexts.

The improvements observed in the experimental group can be attributed to the continuous activation of the proprioceptive and sensory systems (vestibular, visual, and somatosensory) during the exercises. These stimulations promote real-time postural adjustments, thereby enhancing neuromuscular control and balance stability [

25,

26]. The engagement of trunk and lower body muscles also contributes to muscular coordination and functional strength, while the repetitive nature of the exercises supports motor learning and optimizes movement patterns [

15,

23]. However, the lack of significant changes in UBS and fine motor skills can be explained by the targeted nature of the exercises. Indeed, mini-trampoline activities primarily focus on lower body stability and coordination. As suggested by Di Stefano et al. (2010) [

46] and Mandelbaum et al. [

47], although training on unstable surfaces strengthens the trunk and lower limb muscles, it may not provide sufficient stimulus for neuromuscular adaptations in upper body muscles. Moreover, fine motor skills, such as precision and hand movement speed, require specific stimulation, which is not addressed in trampoline rebound exercises [

24].

Our results showed no significant effect of the intervention on fine motor skills, likely due to the mini-trampoline PAP primarily targeting gross motor skills development [

24]. The lack of specific stimulation for precise hand and finger movements may account for the absence of observed improvements. Further research is needed to explore the potential impact of PA, particularly mini-trampoline exercises, on fine motor skills.

The lack of significant group × time interactions in this study may be attributed to the biological and neuromuscular development stage of preschool-aged children, whose sensory and proprioceptive systems are still maturing [

20,

24,

39]. This developmental stage is characterized by rapid growth but also high variability, making adaptations to physical interventions less pronounced compared to older children or adults [

48]. Gross motor skills, such as balance and coordination, are more responsive to physical interventions as they involve large muscle groups, while fine motor skills like dexterity require more targeted and prolonged stimulation [

25,

26]. Additionally, the physiological responses to PA in preschool children differ significantly from those of prepubescent or adult populations due to differences in muscular, hormonal, and cardiovascular development [

49]. These factors likely influence the magnitude of adaptations observed in this age group [

49].

Additionally, the high variability in motor and cognitive development among children in this age group may have affected the consistency of responses, reducing the likelihood of detecting significant effects in group analyses [

50]. Lastly, the intervention's duration may have been insufficient to produce lasting changes in areas such as fine motor skills and WM, which demand extended cognitive and sensory integration [

51].

Finally, the duration of the intervention may have been insufficient to produce significant changes in areas such as WM or dexterity, which require not only physical stimulation but also prolonged cognitive and sensory integration [

20]. These areas are known to be influenced by repeated, tailored, and longer-term interventions [

24].

4.3. Study Limitations

This study has some limitations to consider. First, the absence of objective PA measurements, such as the use of accelerometers, hinders an accurate assessment of the level of stimulation provided to EFs during the mini-trampoline exercises. Second, while the 12-week intervention is a considerable duration, it is possible that the program's design or frequency of sessions may not have been optimized to observe more pronounced effects across all dimensions of motor and cognitive development. Future studies should address these limitations by incorporating objective intensity measurements, and refining program designs to maximize their impact.

4.4. Practical Applications

Given the accessibility and engaging nature of mini-trampoline activities, they can be integrated into preschool physical education programs to support fundamental movement skills in a playful and motivating environment. Despite the absence of significant effects on working memory and fine motor skills, the results indicate that trampoline-based exercises primarily benefit balance, coordination, and inhibitory control. Educators and coaches can implement structured trampoline sessions to foster physical and cognitive development while ensuring safety and age-appropriate progressions. Future research should explore long-term adaptations and consider combining mini-trampoline training with other motor-cognitive activities to maximize developmental benefits in young children.

5. Conclusions

This study provides valuable insights into the benefits of a mini-trampoline physical activity program for Tunisian preschool children, highlighting improvements in motor skills and certain executive functions, particularly inhibitory control. Significant gains in functional mobility, postural steadiness, and lower balance stability underscore the program’s effectiveness in promoting physical development in this age group. However, no notable improvement was observed in working memory, upper balance stability, or fine motor skills, suggesting that the intervention primarily supports gross motor development rather than fine motor skills or complex cognitive functions. The lack of significance in the group × time interactions can be explained by several factors related to the biological and neuromuscular development of preschool-aged children, as their sensory and motor systems are still maturing. These findings help bridge the research gap regarding the impact of physical activity on motor and cognitive development in young Tunisian children, enriching our understanding of trampoline-based programs. Longer and more diverse studies are needed to further explore these effects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.L. and M.S.C.; methodology, M.A.L., D.I.A. and M.S.C.; software, M.A.L., E.A.P., and Y.C.; validation, M.A.L., H.B.S., Y.C., C.I.A., D.I.A. and M.S.C.; formal analysis, M.A.L., A.M.V. and C.I.A.; investigation, M.A.L.; Y.C. and H.B.S.; resources, M.A.L., E.A.P., C.I.A. and A.M.V.; data curation, Y.C., C.I.A. and A.M.V.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.L.; writing—review and editing, M.A.L., E.A.P., C.I.A., Y.C., H.B.S., D.I.A., A.M.V. and M.S.C.; visualization, M.A.L., E.A.P., H.B.S., C.I.A. and A.M.V.; supervision, M.S.C. and D.I.A.; project administration, M.A.L., D.I.A. and C.I.A.; funding acquisition, E.A.P., C.I.A., D.I.A. and A.M.V.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of Sousse (CEFMS 121/2022) and adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author, who was an organizer of the study.

Acknowledgments

A special thank you to Professor of Physical Education, Ghaith Ben-Bouzaiene, for their invaluable assistance throughout the implementation of the study in the kindergarten. Elena Adeina Panaet, Cristina Ioana Alexe, Ana Maria Vulpe and Dan Iulian Alexe thank the “Vasile Alecsandri” University of Bacău, Romania, for their support and assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EF |

Executive Function |

| FM |

Functional Mobility |

| LBS |

Lower Body Strength |

| PA |

Physical Activity |

| PAP |

Physical Activity Program |

| PS |

Postural Steadiness |

| UBS |

Upper Body Strength |

| WM |

Working Memory |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

References

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R.; et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vale, S.; Trost, S.G.; Rêgo, C.; Abreu, S.; Mota, J. Physical Activity, Obesity Status, and Blood Pressure in Preschool Children. J Pediatr 2015, 167, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ltifi, M.A.; Turki, O.; Ben-Bouzaiene, G.; Chong, K.H.; Okely, A.D.; Chelly, M.S. Exploring urban-rural differences in 24-h movement behaviours among tunisian preschoolers: Insights from the SUNRISE study. Sports Med Health Sci 2025, 7, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ltifi, M.A.; Turki, O.; Ben-Bouzaiene, G.; Pagaduan, J.C.; Okely, A.; Chelly, M.S. Exploring 24-Hour Movement Behaviors in Early Years: Findings From the SUNRISE Pilot Study in Tunisia. Pediatr Exerc Sci 2025, 37, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukthir, S.; Essaddam, L.; Mazigh Mrad, S.; Ben Hassine, L.; Gannouni, S.; Nessib, F.; Bouaziz, A.; Brini, I.; Sammoud, A.; Bouyahia, O.; et al. Prevalence and risk factors of overweight and obesity in elementary schoolchildren in the metropolitan region of Tunis, Tunisia. Tunis Med 2011, 89, 50–54. [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines, W. WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee. In Guidelines on Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour and Sleep for Children under 5 Years of Age; World Health Organization © World Health Organization 2019.: Geneva, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ltifi, M.A.; Chong, K.H.; Ben-Bouzaiene, G.; Okely, A.D.; Chelly, M.S. Observed relationships between nap practices, executive function, and developmental outcomes in Tunisian childcare centers. Sports Med Health Sci 2025, 7, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, J.E.; Lambourne, K. Classroom-based physical activity, cognition, and academic achievement. Prev Med 2011, 52 Suppl S1, S36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solis-Urra, P.; Sanchez-Martinez, J.; Olivares-Arancibia, J.; Castro Piñero, J.; Sadarangani, K.P.; Ferrari, G.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, F.; Gaya, A.; Fochesatto, C.F.; Cristi-Montero, C. Physical fitness and its association with cognitive performance in Chilean schoolchildren: The Cogni-Action Project. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2021, 31, 1352–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Z.; Zhao, W.; Jie, J.; Bao, L. Effect of Mini-Trampoline Physical Activity on Executive Functions in Preschool Children. Biomed Res Int 2018, 2018, 2712803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willoughby, M.T.; Pek, J.; Blair, C.B. Measuring executive function in early childhood: a focus on maximal reliability and the derivation of short forms. Psychol Assess 2013, 25, 664–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedewa, A.L.; Ahn, S. The effects of physical activity and physical fitness on children's achievement and cognitive outcomes: a meta-analysis. Res Q Exerc Sport 2011, 82, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomporowski, P.D.; Davis, C.L.; Miller, P.H.; Naglieri, J.A. Exercise and Children's Intelligence, Cognition, and Academic Achievement. Educ Psychol Rev 2008, 20, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyake, A.; Friedman, N.P.; Emerson, M.J.; Witzki, A.H.; Howerter, A.; Wager, T.D. The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex "Frontal Lobe" tasks: a latent variable analysis. Cogn Psychol 2000, 41, 49–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, X.; Legare, C.H.; Ponitz, C.C.; Li, S.; Morrison, F.J. Investigating the links between the subcomponents of executive function and academic achievement: a cross-cultural analysis of Chinese and American preschoolers. J Exp Child Psychol 2011, 108, 677–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriguchi, Y. The early development of executive function and its relation to social interaction: a brief review. Front Psychol 2014, 5, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkarim, O.; Aly, M.; ElGyar, N.; Shalaby, A.M.; Kamijo, K.; Woll, A.; Bös, K. Association between aerobic fitness and attentional functions in Egyptian preadolescent children. Front Psychol 2023, 14, 1172423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, R.; Leahy, A.A.; Lubans, D.R.; Diallo, T.M.O.; Beauchamp, M.R.; Smith, J.J.; Hillman, C.H.; Wade, L. Mediators of the association between physical activity and executive functions in primary school children. J Sports Sci 2024, 42, 2029–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latomme, J.; Calders, P.; Van Waelvelde, H.; Mariën, T.; De Craemer, M. The Role of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) in the Relation between Physical Activity and Executive Functioning in Children. Children (Basel) 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, J.R. Effects of Physical Activity on Children's Executive Function: Contributions of Experimental Research on Aerobic Exercise. Dev Rev 2010, 30, 331–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavilidi, M.; Okely, A.; Chandler, P.; Cliff, D.; Paas, G. Effects of integrated physical exercises and gestures on preschool children's foreign language vocabulary learning. 2024.

- Aragão, F.A.; Karamanidis, K.; Vaz, M.A.; Arampatzis, A. Mini-trampoline exercise related to mechanisms of dynamic stability improves the ability to regain balance in elderly. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 2011, 21, 512–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giagazoglou, P.; Kokaridas, D.; Sidiropoulou, M.; Patsiaouras, A.; Karra, C.; Neofotistou, K. Effects of a trampoline exercise intervention on motor performance and balance ability of children with intellectual disabilities. Res Dev Disabil 2013, 34, 2701–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okemuo, A.J.; Gallagher, D.; Dairo, Y.M. Effects of rebound exercises on balance and mobility of people with neurological disorders: A systematic review. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0292312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muehlbauer, T.; Besemer, C.; Wehrle, A.; Gollhofer, A.; Granacher, U. Relationship between strength, balance and mobility in children aged 7-10 years. Gait Posture 2013, 37, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taube, W.; Gruber, M.; Gollhofer, A. Spinal and supraspinal adaptations associated with balance training and their functional relevance. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2008, 193, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, R.A.; Riethmuller, A.; Hesketh, K.; Trezise, J.; Batterham, M.; Okely, A.D. Promoting fundamental movement skill development and physical activity in early childhood settings: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Exerc Sci 2011, 23, 600–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, N.; Ayyub, M.; Sun, H.; Wen, X.; Xiang, P.; Gao, Z. Effects of Physical Activity on Motor Skills and Cognitive Development in Early Childhood: A Systematic Review. Biomed Res Int 2017, 2017, 2760716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Broeck, J.; Willie, D.; Younger, N. The World Health Organization child growth standards: expected implications for clinical and epidemiological research. Eur J Pediatr 2009, 168, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, S.J.; Melhuish, E. An Early Years Toolbox for Assessing Early Executive Function, Language, Self-Regulation, and Social Development: Validity, Reliability, and Preliminary Norms. J Psychoeduc Assess 2017, 35, 255–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okely, T.; Reilly, J.J.; Tremblay, M.S.; Kariippanon, K.E.; Draper, C.E.; El Hamdouchi, A.; Florindo, A.A.; Green, J.P.; Guan, H.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; et al. Cross-sectional examination of 24-hour movement behaviours among 3- and 4-year-old children in urban and rural settings in low-income, middle-income and high-income countries: the SUNRISE study protocol. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e049267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, L.; Guthold, R.; Cowan, M.; Savin, S.; Bhatti, L.; Armstrong, T.; Bonita, R. The World Health Organization STEPwise Approach to Noncommunicable Disease Risk-Factor Surveillance: Methods, Challenges, and Opportunities. Am J Public Health 2016, 106, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivara, F.P. Pediatric injury control in 1999: where do we go from here? Pediatrics 1999, 103, 883–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. The Effect Size. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Abingdon: Routledge 1988, 77-83, 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, E.P.; O'Dwyer, N.; Cook, R.; Vetter, M.; Cheng, H.L.; Rooney, K.; O'Connor, H. Relationship between physical activity and cognitive function in apparently healthy young to middle-aged adults: A systematic review. J Sci Med Sport 2016, 19, 616–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnelly, J.E.; Hillman, C.H.; Castelli, D.; Etnier, J.L.; Lee, S.; Tomporowski, P.; Lambourne, K.; Szabo-Reed, A.N. Physical Activity, Fitness, Cognitive Function, and Academic Achievement in Children: A Systematic Review. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2016, 48, 1197–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arabatzi, F. Adaptations in movement performance after plyometric training on mini-trampoline in children. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2018, 58, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giagazoglou, P.; Sidiropoulou, M.; Mitsiou, M.; Arabatzi, F.; Kellis, E. Can balance trampoline training promote motor coordination and balance performance in children with developmental coordination disorder? Res Dev Disabil 2015, 36, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. Executive functions. Annu Rev Psychol 2013, 64, 135–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.K.; Tsai, Y.J.; Chen, T.T.; Hung, T.M. The impacts of coordinative exercise on executive function in kindergarten children: an ERP study. Exp Brain Res 2013, 225, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trampolines at home, school, and recreational centers. American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Injury and Poison Prevention and Committee on Sports Medicine and Fitness. Pediatrics 1999, 103, 1053–1056.

- Willoughby, M.T.; Blair, C.B.; Wirth, R.J.; Greenberg, M. The measurement of executive function at age 3 years: psychometric properties and criterion validity of a new battery of tasks. Psychol Assess 2010, 22, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, D.; Blair, C.; Ursache, A.; Willoughby, M.T.; Granger, D.A. Early childcare, executive functioning, and the moderating role of early stress physiology. Dev Psychol 2014, 50, 1250–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willoughby, M.T.; Kupersmidt, J.B.; Voegler-Lee, M.E. Is preschool executive function causally related to academic achievement? Child Neuropsychol 2012, 18, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.; Wang, M.; Wang, Z. Parental corporal punishment in relation to children's executive function and externalizing behavior problems in China. Soc Neurosci 2018, 13, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiStefano, L.J.; Padua, D.A.; Blackburn, J.T.; Garrett, W.E.; Guskiewicz, K.M.; Marshall, S.W. Integrated injury prevention program improves balance and vertical jump height in children. J Strength Cond Res 2010, 24, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandelbaum, B.R.; Silvers, H.J.; Watanabe, D.S.; Knarr, J.F.; Thomas, S.D.; Griffin, L.Y.; Kirkendall, D.T.; Garrett, W., Jr. Effectiveness of a neuromuscular and proprioceptive training program in preventing anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female athletes: 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med 2005, 33, 1003–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A., Pigou, D. , Clarke, L. and McLachlan, C. Literature Review on Motor Skill and Physical Activity in Preschool Children in New Zealand. Advances in Physical Education. Advances in Physical Education 2017, 7, 10-26. [CrossRef]

- Falk, B.; Dotan, R. Child-adult differences in the recovery from high-intensity exercise. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 2006, 34, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulf, G.; Lewthwaite, R. Optimizing performance through intrinsic motivation and attention for learning: The OPTIMAL theory of motor learning. Psychon Bull Rev 2016, 23, 1382–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lephart, S.M.; Pincivero, D.M.; Giraldo, J.L.; Fu, F.H. The role of proprioception in the management and rehabilitation of athletic injuries. Am J Sports Med 1997, 25, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).