Submitted:

24 September 2025

Posted:

25 September 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

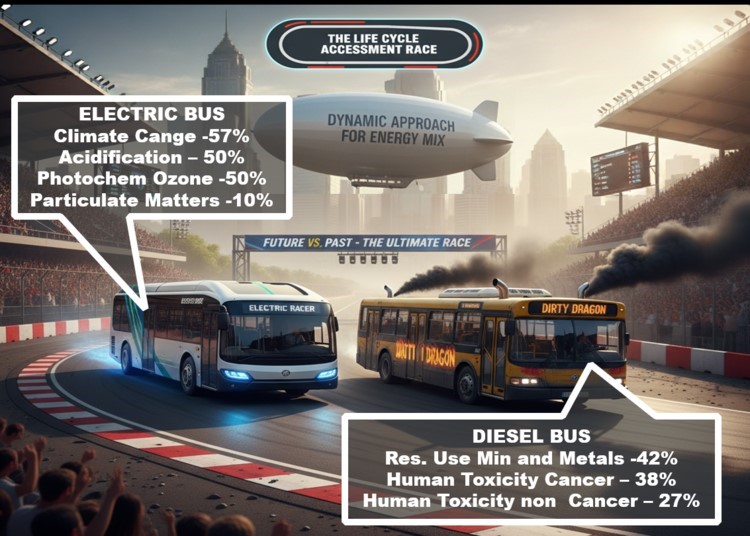

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Goal and Scope

2.1. Functional Unit

2.2. System Boundaries

2.3. Allocation

2.4. Environmental Impact Categories

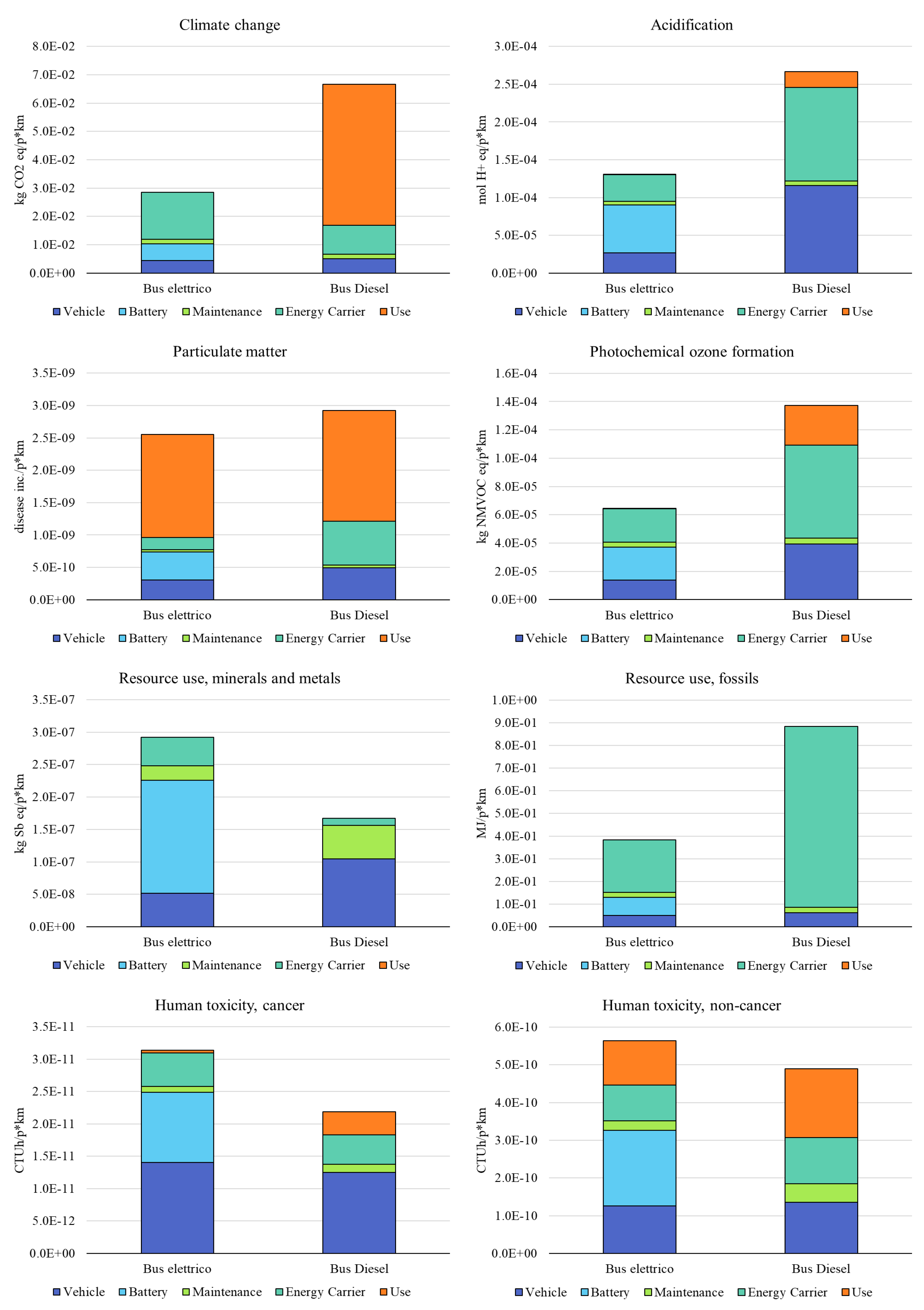

3. Life Cycle Inventory

3.1. Vehicles and Batteries Production

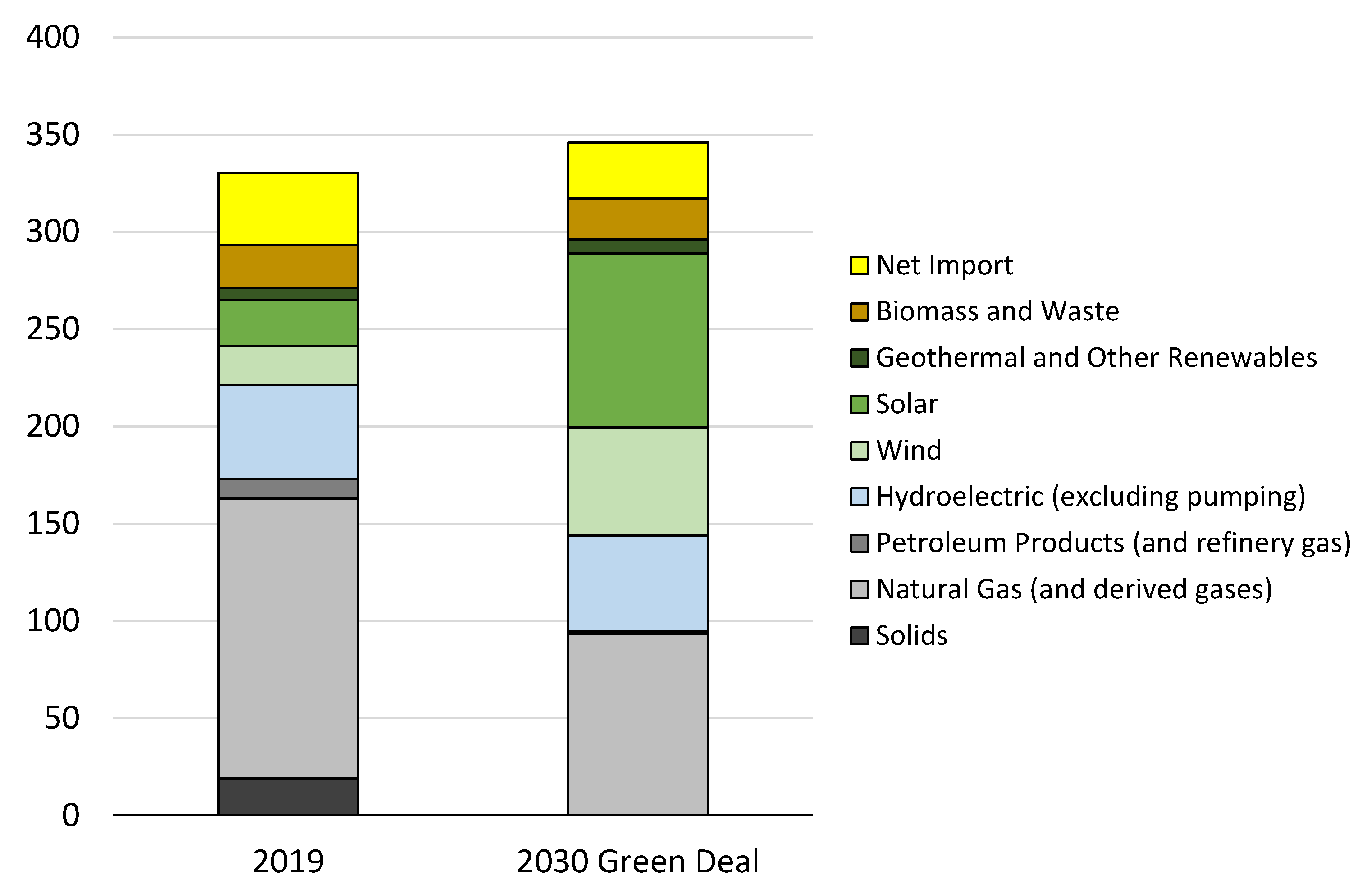

3.2. Electricity and Fossil Fuels

3.3. Use Phase

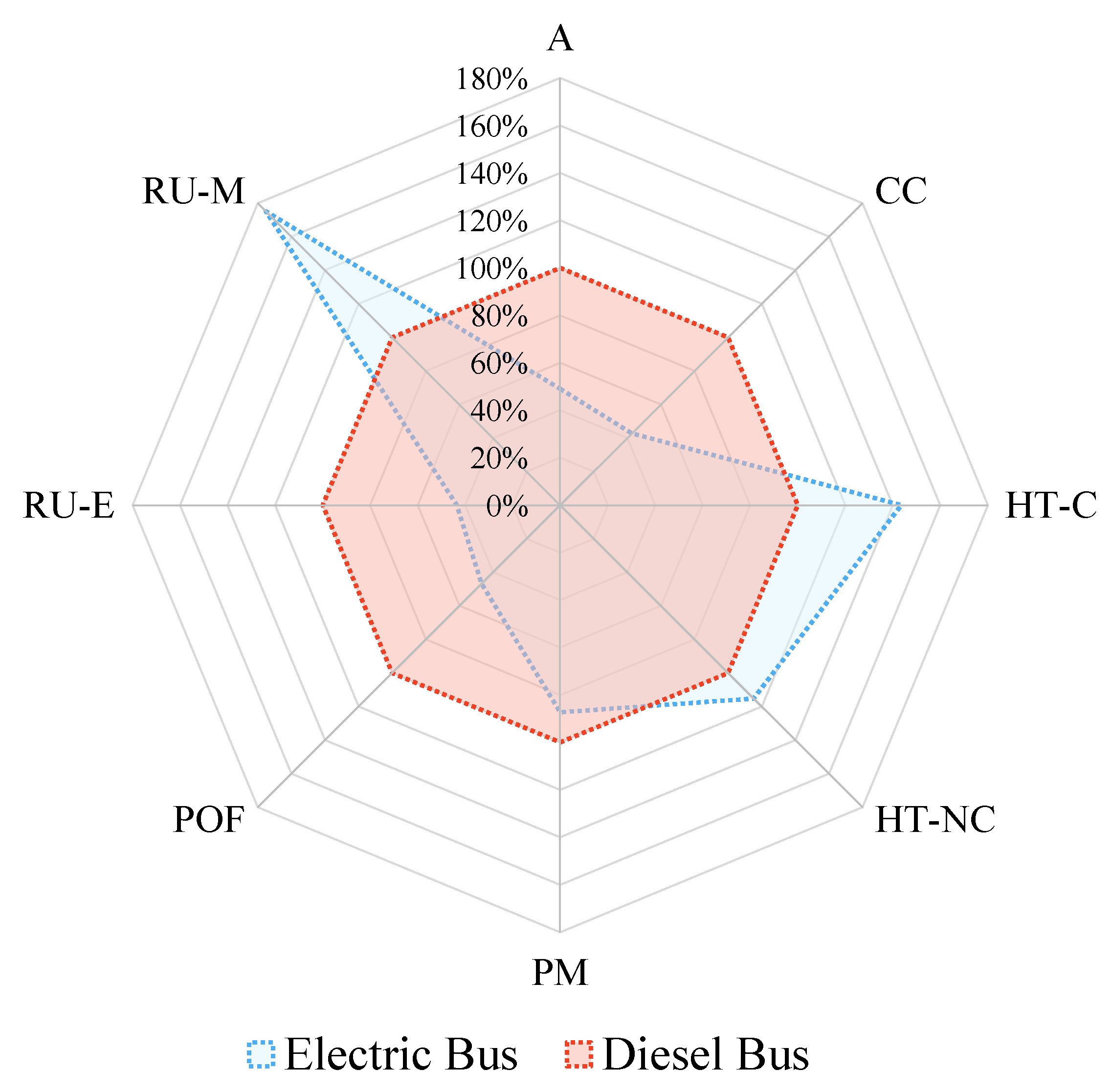

4. Results – Life Cycle Impact Assessment

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A | Acidification |

| AE | Accumulated Exceedance |

| BMS | Battery Management System |

| BOM | Bill Of Materials |

| CC | Climate Change |

| CLCC | Commodity Life Cycle Costing |

| CTUh | Comparative Toxic Unit for human |

| EEA | European Environment Agency |

| EF | Environmental Footprint |

| EMEP | European Monitoring and Evaluation Programme |

| EPD | Environmental product Declaration |

| GREET | The Greenhouse gases, Regulated Emissions, and Energy use in Technologies Model |

| GWP100 | Global Warming Potential 100 years |

| HT-C | Human toxicity, cancer |

| HT-NC | Human toxicity, non-cancer |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| LCIA | Life Cycle Impact Assessment |

| MHDV | Medium Heavy-Duty Vehicles |

| NMC 712 | Lithium Nickel Manganese Cobalt oxide LiNi0.7Mn0.1Co0.2 |

| PM | Particulate matter |

| POF | Photochemical ozone formation |

| RU-F | Resource use, fossils |

| RU-M | Resource use, minerals and metals |

| RdS | Ricerca di Sistema |

| RSE | Ricerca Sistema Energetico |

| TPL | Trasporto Pubblico Locale |

Appendix A. Life Cycle Inventory Additional Information

Busses Composition

| System | Subsystems | Description of Individual Parts |

|---|---|---|

| Body system | Cab-in-white | Primary MHDV structure, i.e., a single-body assembly to which the other major components are attached |

| Body Panels and Fairings | Closure and hang-on panels, including hood, roof, decklid, doors, quarter panels, and fenders, as well as fairings | |

| Front/Rear Bumpers | Impact bars, energy absorbers, and mounting hardware | |

| Glass | Front windshield, and windows (door, side, and sleeper) | |

| Lighting | Exterior: Head lamps, fog lamps, turn signals, side markers, front top markers, and rear light assemblies Interior: Wiring and controls for interior lighting, instrumentation, and power accessories |

|

| Heating, Ventilation, Air Conditioning (HVAC) Module | Air flow system, heating system, and air conditioning system (includes a condenser, fan, heater, ducting, and controls) | |

| Seating and Restraint System | Seat tracks, seat frames, foam, trim, restraints, anchors, head restraints, arm rests, seat belts, tensioners, clips, air bags, and sensor assemblies | |

| Door Module | Door insulation, trim assemblies, speaker grills, and switch panels and handles (door panels are part of body panels) | |

| Instrument Panel | Panel structure, knee bolsters and brackets, instrument cluster (including switches), exterior surface, console storage, glove box panels, glove box assembly and exterior, and top cover | |

| Trim and Insulation | Emergency brake cover, switch panels, ash trays, cup holders, headliner assemblies, overhead console assemblies, assist handles, overhead storage, pillar trim, sun visors, carpet/rubber, padding, insulation, and accessory mats | |

| Body Hardware | Miscellaneous body components | |

| Powertrain system | Engine Unit | Engine block, cylinder heads, shafts, fuel injection, engine air system, ignition system, manifolds, alternator, containers and pumps for the lubrication system, gaskets, and seals |

| Engine Fuel Storage System | Fuel tank, tank mounting straps, tank shield, insulation, filling piping, and supply piping | |

| Powertrain Thermal System | Water pump, radiator, and fan | |

| Exhaust System | Catalytic converter, muffler, heat shields, and exhaust piping | |

| Powertrain Electrical System | Control wiring, sensors, switches, and processors | |

| Emission Control Electronics | Sensors, processors, and engine emission feedback equipment | |

| Transmission Unit | Clutch, gear box, final drive, and controls Use of automated manual transmission system |

|

| Chassis system | Cradle | Frame assembly, front rails and cross-members, and cab and body brackets (the cradle bolts to cab-in-white and supports the mounting of engine) |

| Driveshaft/Axle/ Inter-axle Shaft | Propeller shaft that connects gearbox to the differential Half shaft that connects wheels to the differential; Shafts that connect front and rear parts of a tandem drive axle | |

| Axles | Steer (single) and drive (tandem) axles | |

| Differential | A gear set that transmits energy from driveshaft to axles and allows for each of the driving wheels to rotate at different speeds while supplying them with an equal amount of torque | |

| Suspensions | Upper and lower shock brackets, shock absorbers, springs, steering knuckle, and stabilizer shaft | |

| Braking System | Hub, disc, rotor, splash shield, and calipers | |

| Wheels and Tires | Steer and drive axle wheels and tires | |

| Auxiliary | Steering wheel, column, joints, linkages, bushes, housings, and hydraulic- assist equipment | |

| Electric drive system | Generator | Power converter that takes mechanical energy from the engine and produces electrical energy to recharge batteries and power the electric motor for series |

| Electric drive system | Traction Motor | Electric motor used to drive the wheels |

| Electric drive system | Electronic Controller | Power controller/phase inverter system that converts power between the batteries and motor/generators for electric drive vehicles |

| Battery system | ICEV | Pb-acid battery to handle startup and accessory load |

| Battery system | EV | Pb-acid battery to handle mainly startup load, Li-ion battery for use in electric drive system |

| Fluid system | ICEV | Engine oil, engine/powertrain coolant with coolant cleaner, brake fluid, windshield fluid, transmission fluid, power steering fluid, lubricant oils, and adhesives |

| Fluid system | EV | Powertrain coolant with coolant cleaner, power steering fluid, brake fluid, transmission fluid, windshield fluid, lubricant oils, adhesives |

| Van/Box system | Body | Front, sides, floor, and roof of van/box, along with auxiliary parts |

| Lift-gates system | Lift-gates | Gates used for loading/unloading of goods, along with their hydraulic systems and other constituent parts |

| System | Material | Mass (kg) |

|---|---|---|

| Body | 5.05E+03 | |

| Cast aluminum | 2.39E+02 | |

| Copper | 2.37E+01 | |

| Cotton paper | 6.21E+00 | |

| Glass | 3.63E+02 | |

| Glass fiber-reinforced plastic | 7.65E+02 | |

| Graphite | 7.50E+00 | |

| Latex | 2.21E+02 | |

| Leather | 1.15E+02 | |

| Plastic | 6.76E+02 | |

| Rubber | 1.36E+02 | |

| Silica | 7.50E+00 | |

| Stainless steel | 1.84E+02 | |

| Steel | 1.88E+03 | |

| Wrought aluminum | 4.27E+02 | |

| Chassis (w/o battery) | 3.72E+03 | |

| Brass | 2.78E-01 | |

| Cast aluminum | 1.89E+02 | |

| Cast iron | 3.43E+02 | |

| Copper | 8.83E-01 | |

| Magnet | 5.37E-01 | |

| Plastic | 2.17E+00 | |

| Rubber | 2.50E+02 | |

| Steel | 2.93E+03 | |

| Electronic Controller | 1.30E+01 | |

| Alumina | 3.89E-02 | |

| Average Plastic | 1.31E-01 | |

| Cast aluminum | 6.95E+00 | |

| Copper/Brass | 3.95E+00 | |

| Epoxy resin | 2.55E-02 | |

| Fiberglass | 8.04E-02 | |

| Nickel | 2.14E-02 | |

| Nylon | 9.38E-03 | |

| PET | 3.59E-01 | |

| Polypropylene | 5.12E-01 | |

| Polyurethane | 2.55E-01 | |

| Rubber | 1.61E-01 | |

| Steel | 3.66E-01 | |

| Zinc | 1.33E-01 | |

| Zinc oxide | 2.68E-03 | |

| Lead-Acid Battery | 3.13E+01 | |

| Fiberglass | 6.63E-01 | |

| Lead | 2.18E+01 | |

| Plastic (polypropylene) | 1.92E+00 | |

| Sulfuric Acid | 2.49E+00 | |

| Water | 4.45E+00 | |

| Li-Ion Battery | 3.00E+03 | |

| Traction Motor | 1.34E+02 | |

| Cast aluminum | 4.23E+01 | |

| Copper/Brass | 1.16E+01 | |

| Enamel | 5.23E-01 | |

| Epoxy resin | 1.03E+00 | |

| Glass fiber | 1.34E-02 | |

| Methacrylate ester resin | 1.74E-01 | |

| Mica | 4.02E-02 | |

| Nd(Dy)FeB magnet | 3.85E+00 | |

| Nickel | 4.02E-02 | |

| Nylon | 1.34E-02 | |

| Paint/Varnish | 4.29E-01 | |

| PBT | 2.14E-01 | |

| PET | 4.29E-01 | |

| Phenolic resin | 6.70E-02 | |

| Silicone | 5.36E-02 | |

| Stainless steel | 8.98E-01 | |

| Steel | 7.23E+01 | |

| Zinc | 1.34E-02 | |

| Transmission System/Gearbox | 9.00E+01 | |

| Brass | 1.95E-01 | |

| Cast aluminum | 5.28E+00 | |

| Cast iron | 2.18E+01 | |

| Magnet | 1.90E-02 | |

| Plastic | 9.55E-02 | |

| Rubber | 9.55E-02 | |

| Steel | 6.21E+01 | |

| Wrought aluminum | 3.60E-01 | |

| Fluids | 8.76E+01 | |

| Steer axle | 7.00E+00 | |

| Drive axle | 5.87E+00 | |

| Inter-axle/Drive shafts | 1.40E+01 | |

| Wheel-end: Steer axle | 8.62E+00 | |

| Wheel-end: Drive axle | 8.62E+00 | |

| Transmission Fluid | 2.35E+00 | |

| Powertrain Coolant | 1.68E+01 | |

| Coolant cleaner | 1.71E+01 | |

| Windshield Fluid | 7.19E+00 | |

| Total | 1.21E+04 |

| System | Material | Mass(kg) |

|---|---|---|

| Body | 5.05E+03 | |

| Cast aluminum | 2.39E+02 | |

| Copper | 2.37E+01 | |

| Cotton paper | 6.21E+00 | |

| Glass | 3.63E+02 | |

| Glass fiber-reinforced plastic | 7.65E+02 | |

| Graphite | 7.50E+00 | |

| Latex | 2.21E+02 | |

| Leather | 1.15E+02 | |

| Magnet | 0.00E+00 | |

| Plastic | 6.76E+02 | |

| Rubber | 1.36E+02 | |

| Silica | 7.50E+00 | |

| Stainless steel | 1.84E+02 | |

| Steel | 1.88E+03 | |

| Wrought aluminum | 4.27E+02 | |

| Chassis (w/o battery) | 3.72E+03 | |

| Brass | 2.78E-01 | |

| Cast aluminum | 1.89E+02 | |

| Cast iron | 3.43E+02 | |

| Copper | 8.83E-01 | |

| Magnet | 5.37E-01 | |

| Plastic | 2.17E+00 | |

| Rubber | 2.50E+02 | |

| Steel | 2.93E+03 | |

| Lead-Acid Battery | 6.26E+01 | |

| Fiberglass | 1.33E+00 | |

| Lead | 4.35E+01 | |

| Plastic (polypropylene) | 3.85E+00 | |

| Sulfuric Acid | 4.98E+00 | |

| Water | 8.90E+00 | |

| Powertrain System (including BOP) | 6.45E+02 | |

| Bronze | 5.05E-02 | |

| Cast aluminum | 2.69E+01 | |

| Cast iron | 2.37E+02 | |

| Ceramic | 4.75E+01 | |

| Copper & Brass | 1.96E-01 | |

| Graphite | 1.88E-02 | |

| Nichrome | 1.68E+00 | |

| Plastic | 4.29E+01 | |

| Platinum | 3.16E-01 | |

| Rubber | 2.06E+00 | |

| Stainless steel | 2.67E+01 | |

| Steel | 1.85E+02 | |

| Wrought aluminum | 7.42E+01 | |

| Transmission System/Gearbox | 2.21E+02 | |

| Brass | 4.78E-01 | |

| Cast aluminum | 1.30E+01 | |

| Cast iron | 5.36E+01 | |

| Magnet | 4.67E-02 | |

| Plastic | 2.35E-01 | |

| Rubber | 2.35E-01 | |

| Steel | 1.53E+02 | |

| Wrought aluminum | 8.84E-01 | |

| Fluids | 1.24E+02 | |

| Engine Oil | 1.53E+01 | |

| Steer axle | 7.00E+00 | |

| Drive axle | 5.87E+00 | |

| Inter-axle/Drive shafts | 1.40E+01 | |

| Wheel-end: Steer axle | 8.62E+00 | |

| Wheel-end: Drive axle | 8.62E+00 | |

| Transmission Fluid | 7.65E+00 | |

| Powertrain Coolant | 2.45E+01 | |

| Coolant cleaner | 2.50E+01 | |

| Windshield Fluid | 7.19E+00 | |

| Total | 9.82E+03 |

| Type of component | Spare parts | N. substitution |

|---|---|---|

| Fluids | ||

| Engine Oil (ICEB only) | 13 | |

| Steer axle | 6 | |

| Drive axle | 0 | |

| Inter-axle/Drive shafts | 16 | |

| Wheel-end: Steer axle | 0 | |

| Wheel-end: Drive axle | 0 | |

| Transmission Fluid | 5 | |

| Powertrain Coolant | 2 | |

| Coolant cleaner | 2 | |

| Windshield Fluid | 73 | |

| Battery | ||

| Lead Acid | 6 | |

| Li-Ion | 1 | |

| Tyre | ||

| Steer Tire | 3 | |

| Drive Tyre | 2 | |

| Other components | ||

| Windshield Wiper Blades | 25 | |

| Engine oil filter (ICEB only) | 10 |

Appendix B. Monte Carlo Analysis

| Diesel (l/100km) |

Elettrico (kWh/100km) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Nordelöf et al, 2019 [6] | 45 | 110 |

| Basma et al., 2020 [59] | 55.7 | 170 |

| ISPRA 2020 [54] | 38.04 | n.a. |

| Ecoinvent [40] | 63.17 | n.a. |

| et al., 2022 [8] | 42 | 150 |

| Luu et al., 2022 [30] | 26 | 136 |

| Mastinu e Solari, 2022 [18] | n.a. | 125 |

| Green Bocconi, 2021 [60] | n.a. | 115 |

| Söderena et al., 2019 [61] | 28 | n.a. |

| Motus-E, 2022 [5] | n.a. | 127 |

| Zhou et al., 2016 [62] | 138 | |

| Zhou et al 2016 [62] | 175 | |

| Zhao et al., 2021 [7] | 29.20 | 120 |

| Doulgeris et al., 2024 [63] | n.a. | 96 |

| Doulgeris et al., 2024 [63] | n.a. | 220 |

| Min value | 26 | 96 |

| Max value | 63.17 | 220 |

| Best guess value | 38.04 | 115 |

References

- European Environment Agency. Digitalisation in the Mobility System: Challenges and Opportunities; Transport and environment report; European Environment Agency: Luxembourg, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Mobility and Transport EU Transport in Figures – Statistical Pocketbook 2023 2023.

- The European Green Deal - European Commission. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (accessed on 29 December 2023).

- Transport and the Green Deal - European Commission Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/transport-and-green-deal_en.

- Motus-E Autobus Elettrici Nel Trasporto Pubblico. Un Vademecum 2022.

- Nordelöf, A.; Romare, M.; Tivander, J. Life Cycle Assessment of City Buses Powered by Electricity, Hydrogenated Vegetable Oil or Diesel. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 2019, 75, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, E.; Walker, P.; Surawski, N. Emissions Life Cycle Assessment of Diesel, Hybrid and Electric Buses. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part D: Journal of Automobile Engineering 2021, 236, 095440702110343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczurowski, J.; Lubeck, A.; Bałys, M.; Brodawka, E.; Zarębska, K. Life Cycle Assessment Study on the Public Transport Bus Fleet Electrification in the Context of Sustainable Urban Development Strategy. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 824, 153872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubecki, A.; Szczurowski, J.; Zarębska, K. A Comparative Environmental Life Cycle Assessment Study of Hydrogen Fuel, Electricity and Diesel Fuel for Public Buses. Applied Energy 2023, 350, 121766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooney, G.; Hawkins, T.R.; Marriott, J. Life Cycle Assessment of Diesel and Electric Public Transportation Buses. Journal of Industrial Ecology 2013, 17, 689–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DIRETTIVA (UE) 2019/1161 DEL PARLAMENTO EUROPEO E DEL CONSIGLIO Del 20 Giugno 2019 Che Modifica La Direttiva 2009/33/CE Relativa Alla Promozione Di Veicoli Puliti e a Basso Consumo Energetico Nel Trasporto Su Strada; 2019; Vol. PE/57/2019/REV/2;

- Decreto Legislativo Del 09/11/2021 n. 187 - Attuazione Della Direttiva (UE) 2019/1161 Che Modifica La Direttiva 2009/33/CE Relativa Alla Promozione Di Veicoli Puliti e a Basso Consumo Energetico Nel Trasporto Su Strada.; 284AD.

- Commission Recommendation (EU) 2021/2279 of 15 December 2021 on the Use of the Environmental Footprint Methods to Measure and Communicate the Life Cycle Environmental Performance of Products and Organisations; 2021; Vol. 471.

- Garcia, R.; Marques, P.; Freire, F. Life-Cycle Assessment of Electricity in Portugal. Applied Energy 2014, 134, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannuzzi, L.; Hilbert, J.A.; Silva Lora, E.E. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) for Use on Renewable Sourced Hydrogen Fuel Cell Buses vs Diesel Engines Buses in the City of Rosario, Argentina. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 29694–29705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelti, F.; Allouhi, A.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G.; Saadani, R.; Jamil, A.; Rahmoune, M. Environmental Life Cycle Assessment of Alternative Fuels for City Buses: A Case Study in Oujda City, Morocco. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 25308–25319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, N.R.; Martin, K.K.; Haslam, S.J.; Faile, J.C.; Kamens, R.M.; Gheewala, S.H. A Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Electric, Compressed Natural Gas, and Diesel Buses in Thailand. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 314, 128013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastinu, G.; Solari, L. Electric and Biomethane-Fuelled Urban Buses: Comparison of Environmental Performance of Different Powertrains. Int J Life Cycle Assess 2022, 27, 238–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ogaili, A.S.; Al-Shetwi, A.Q.; Sudhakar Babu, T.; Hoon, Y.; Abdullah, M.A.; Alhasan, A.; Al-Sharaa, A. Electric Buses in Malaysia: Policies, Innovations, Technologies and Life Cycle Evaluations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, E.; Walker, P.; Surawski, N. Emissions Life Cycle Assessment of Diesel, Hybrid and Electric Buses. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part D: Journal of Automobile Engineering 2021, 236, 095440702110343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargiulo, A.; Carvalho, M.L.; Girardi, P. Life Cycle Assessment of Italian Electricity Scenarios to 2030. Energies 2020, 13, 3852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.L.; Marmiroli, B.; Girardi, P. Life Cycle Assessment of Italian Electricity Production and Comparison with the European Context. Energy Reports 2022, 8, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, C.; Marmiroli, B.; Carvalho, M.L.; Girardi, P. Life Cycle Assessment of Photovoltaic Electricity Production in Italy: Current Scenario and Future Developments. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 948, 174846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García, A.; Monsalve-Serrano, J.; Lago Sari, R.; Tripathi, S. Life Cycle CO₂ Footprint Reduction Comparison of Hybrid and Electric Buses for Bus Transit Networks. Applied Energy 2022, 308, 118354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO - International Organization for Standardization ISO 14040:2006: Environmental Management — Life Cycle Assessment — Principles and Framework; ISO 14040:2006; 2006.

- Ekvall, T.; Azapagic, A.; Finnveden, G.; Rydberg, T.; Weidema, B.P.; Zamagni, A. Attributional and Consequential LCA in the ILCD Handbook. Int J Life Cycle Assess 2016, 21, 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The International EPD System Environmental Product Declaration According to ISO 14025 for: Solaris Urbino 12 Hybrid Bus; S-P-05600; 2022.

- Directorate-General for Climate Action (European Commission); Ricardo Energy & Environment; Hill, N.; Amaral, S.; Morgan-Price, S.; Nokes, T.; Bates, J.; Helms, H.; Fehrenbach, H.; Biemann, K.; et al. Determining the Environmental Impacts of Conventional and Alternatively Fuelled Vehicles through LCA: Final Report; Publications Office of the European Union: LU, 2020; ISBN 978-92-76-20301-8.

- Wernet, G.; Bauer, C.; Steubing, B.; Reinhard, J.; Moreno-Ruiz, E.; Weidema, B. The Ecoinvent Database Version 3 (Part I): Overview and Methodology. Int J Life Cycle Assess 2016, 21, 1218–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, L.Q.; Riva Sanseverino, E.; Cellura, M.; Nguyen, H.-N.; Tran, H.-P.; Nguyen, H.A. Life Cycle Energy Consumption and Air Emissions Comparison of Alternative and Conventional Bus Fleets in Vietnam. Energies 2022, 15, 7059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delle Monache, A.; Marmiroli, B.; Luciano, N.; Carvalho, M.L.; Girardi, P.; Dotelli, G.; Franzò, S. Influence of Thermoelectric Generation Primary Data and Allocation Methods on Life Cycle Assessment of the Electricity Generation Mix: The Case of Italy. In Proceedings of the Sustainable Development with Renewable Energy; Caetano, N.S., Ed.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024; pp. 417–428.

- Fazio, S.; Biganzoli, F.; De Laurentiis, V.; Zampori, L.; Sala, S.; Diaconu, E. Supporting Information to the Characterisation Factors of Recommended EF Life Cycle Impact Assessment Methods; European Union, Luxembourg, 2018, 2019.

- Stocker, T.F.; Qin, D.; Plattner, G.-K.; Tignor, M.; Allen, S.K.; Boschung, J.; Nauels, A.; Xia, Y.; Bex, V.; Midgley, P.M. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 1535 pp;

- van Zelm, R.; Huijbregts, M.A.J.; den Hollander, H.A.; van Jaarsveld, H.A.; Sauter, F.J.; Struijs, J.; van Wijnen, H.J.; van de Meent, D. European Characterization Factors for Human Health Damage of PM10 and Ozone in Life Cycle Impact Assessment. Atmospheric Environment 2008, 42, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posch, M.; Seppälä, J.; Hettelingh, J.-P.; Johansson, M.; Margni, M.; Jolliet, O. The Role of Atmospheric Dispersion Models and Ecosystem Sensitivity in the Determination of Characterisation Factors for Acidifying and Eutrophying Emissions in LCIA. Int J Life Cycle Assess 2008, 13, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seppälä, J.; Posch, M.; Johansson, M.; Hettelingh, J.-P. Country-Dependent Characterisation Factors for Acidification and Terrestrial Eutrophication Based on Accumulated Exceedance as an Impact Category Indicator (14 Pp). Int J Life Cycle Assessment 2006, 11, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantke, P.; Evans, J.R.; Hodas, N.; Apte, J.S.; Jantunen, M.J.; Jolliet, O.; McKone, T.E. Health Impacts of Fine Particulate Matter. In Global guidance for life cycle impact assessment indicators; SETAC, 2016; Vol. 1, pp. 76–99 ISBN 978-92-807-3630-4.

- Rosenbaum, R.K.; Bachmann, T.M.; Gold, L.S.; Huijbregts, M.A.J.; Jolliet, O.; Juraske, R.; Koehler, A.; Larsen, H.F.; MacLeod, M.; Margni, M.; et al. USEtox—the UNEP-SETAC Toxicity Model: Recommended Characterisation Factors for Human Toxicity and Freshwater Ecotoxicity in Life Cycle Impact Assessment. Int J Life Cycle Assess 2008, 13, 532–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oers, L.; De Koning, A.; Guinée, J.B.; Huppes, G. Abiotic Resource Depletion in LCA. Road and Hydraulic Engineering Institute, Ministry of Transport and Water, Amsterdam 2002.

- Wernet, G.; Bauer, C.; Steubing, B.; Reinhard, J.; Moreno-Ruiz, E.; Weidema, B. The Ecoinvent Database Version 3 (Part I): Overview and Methodology. Int J Life Cycle Assess 2016, 21, 1218–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, R.K.; Kelly, J.C.; Elgowainy, A. Vehicle-Cycle Inventory for Medium- and Heavy-Duty Vehicles; Argonne National Laboratory (ANL), Argonne, IL (United States), 2021.

- Carvalho, M.L.; Temporelli, A.; Girardi, P. Life Cycle Assessment of Stationary Storage Systems within the Italian Electric Network. Energies 2021, 14, 2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.L.; Temporelli, A.; Brivio, E.; Brambilla, P.C.; Mela, G.; Girardi, P. Batteries in Motion: A Life Cycle Assessment and Critical Resource Use Analysis of Micromobility Vehicles with Primary Li-Ion Battery Data. Journal of Energy Storage 2025, 125, 116965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brambilla, P.C.; Temporelli, A.; Mela, G.; Brivio, E.; Marmiroli, B. LCA della mobilità urbana dalle persone alle merci. 2021.

- Santini, A.; Morselli, L.; Passarini, F.; Vassura, I.; Di Carlo, S.; Bonino, F. End-of-Life Vehicles Management: Italian Material and Energy Recovery Efficiency. Waste Management 2011, 31, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The International EPD System Environmental Product Declaration According to ISO 14025 for: Solaris Urbino 12 Hybrid Bus; S-P-05600; 2022.

- Cusenza, M.A.; Bobba, S.; Ardente, F.; Cellura, M.; Di Persio, F. Energy and Environmental Assessment of a Traction Lithium-Ion Battery Pack for Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 215, 634–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmiroli, B.; Carvalho, M.L.; Mela, G.; Molocchi, A.; Girardi, P. Life Cycle Assessment and Evaluation of External Costs of the Italian Electricity Mix. In Proceedings of the The 9th International Conference on Energy and Environment Research; Caetano, N.S., Felgueiras, M.C., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2023; pp. 203–213.

- Ferrara, C.; Marmiroli, B.; Carvalho, M.L.; Girardi, P. Life Cycle Assessment of Photovoltaic Electricity Production in Italy: Current Scenario and Future Developments. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 948, 174846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.N.I. Ente Nazionale Italiano di Unificazione UNI EN 590:2017 - Combustibili per Autotrazione - Gasolio per Motori Diesel - Requisiti e Metodi Di Prova; 2017.

- Brambilla, P.C.; Brivio, E.; Marmiroli, B.; Mela, G.; Molocchi, A.; Temporelli, A. LCA Della Mobilità Urbana Dalle Persone Alle Merci; Ricerca di Sistema, RSE, n. 21010643: Milano, 2021.

- GSE Energia Nel Settore Trasporti 2005-2019; 2020.

- Mastinu, G.; Solari, L. Electric and Biomethane-Fuelled Urban Buses: Comparison of Environmental Performance of Different Powertrains. Int J Life Cycle Assess 2022, 27, 238–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISPRA La Banca Dati Dei Fattori Di Emissione Medi per Il Parco Circolante in Italia (FE2020) 2020.

- European Environment Agency EMEP/EEA Air Pollutant Emission Inventory Guidebook - 2009; 2009.

- Ntziachristos, L.; Boulter, P. Road Vehicle Tyre and Brake Wear. Road Surface Wear. In EMEP/CORINAIR emission inventory guidebook; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2009.

- O’Connell, A.; Pavlenko, N.; Bieker, G.; Searle, S. A Comparison of the Life-Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions of European Heavy-Duty Vehicles and Fuels. International Council on Clean Transportation.

- Syré, A.M.; Shyposha, P.; Freisem, L.; Pollak, A.; Göhlich, D. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Battery and Fuel Cell Electric Cars, Trucks, and Buses. World Electric Vehicle Journal 2024, 15, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basma, H.; Mansour, C.; Haddad, M.; Nemer, M.; Stabat, P. Comprehensive Energy Modeling Methodology for Battery Electric Buses. Energy 2020, 207, 118241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, Università Bocconi Scenari e Prospettive Dell’elettrificazione Del Trasporto Pubblico Su Strada; Research Report Series; 2021.

- Söderena, P.; Nylund, N.-O.; Mäkinen, R. City Bus Performance Evaluation; VTT Customer Report; VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland, 2019.

- Zhou, B.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, B.; Wang, R.; Ke, W.; Zhang, S.; Hao, J. Real-World Performance of Battery Electric Buses and Their Life-Cycle Benefits with Respect to Energy Consumption and Carbon Dioxide Emissions. Energy 2016, 96, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doulgeris, S.; Zafeiriadis, A.; Athanasopoulos, N.; Tzivelou, Ν.; Michali, M.E.; Papagianni, S.; Samaras, Z. Evaluation of Energy Consumption and Electric Range of Battery Electric Busses for Application to Public Transportation. Transportation Engineering 2024, 15, 100223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Impact Categories | Functional Unit | Midpoint Indicator | Characterization Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Climate change (CC) | kg CO2eq | Total global warming potential over the 100-year time horizon (GWP100). | IPCC 2013 [33] |

| Photochemical ozone formation (POF) | kg NMVOCeq | Potential for photochemical ozone formation. | LOTOS-EUROS come applicato in ReCiPe 2008 [34] |

| Acidification (A) | Mol H+eq | Accumulated exceedance of the critical load of acidifying substances in terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems. | Superamento accumulato AE (Accumulated Exceedance) [35,36] |

| Particulate matter (PM) | Disease incidence. | Impact on human health due to exposure to PM2.5 particulate matter (disease incidence) | UNEP-SETAC Task Force (TF) on PM [37] |

| Human toxicity, non-cancer (HT-NC) | CTUh(*) | Increase in non-carcinogenic morbidity in the total population per unit of chemical compound emitted | USEtox, UNEP/SETAC Life Cycle Initiative [38] |

| Human toxicity, cancer (HT-C) | CTUh | Increase in carcinogenic morbidity in the total population per unit of chemical compound emitted | USEtox, UNEP/SETAC Life Cycle Initiative [38] |

| Resource use, fossils (RU-E) | MJ | Depletion of abiotic resources, fossil fuels (MJ) | Abiotic Resource Depletion, “ultimate reserves” [39] |

| Resource use, minerals and metals (RU-M) | kg Sbeq | Depletion of abiotic resources, minerals and metals (kg Sb eq.) | Abiotic Resource Depletion, “ultimate reserves” [39] |

| Systems | BEB (kg) | ICEB (kg) |

|---|---|---|

| Body | 5046.53 | 5046.53 |

| Chassis (w/o battery) | 3717.56 | 3717.56 |

| Electronic Controller | 13.00 | 0.00 |

| Fluids | 87.60 | 123.75 |

| Lead-Acid Battery | 31.30 | 62.60 |

| Li-Ion Battery | 2995.00 | 0.00 |

| Powertrain System (including BOP) | 0.00 | 644.96 |

| Traction Motor | 134.00 | 0.00 |

| Transmission System/Gearbox | 90.00 | 221.00 |

| Totale complessivo | 12115.00 | 9816.40 |

| Pollutant | Emission Factor [t/t] Urban |

|---|---|

| CO | 8.85E-04 |

| NOx | 1.64E-03 |

| NMVOC | 1.29E-04 |

| CH4 | 1.65E-05 |

| N2O | 1.31E-04 |

| NH3 | 2.83E-05 |

| PM exhaust | 2.80E-05 |

| CO2 | 3.16E+00 |

| SO2 | 1.43E-05 |

| Pb Exhaust | 4.89E-11 |

| Cadmium exhaust | 6.76E-09 |

| Copper exhaust | 1.15E-06 |

| Chromium exhaust | 3.68E-08 |

| Nickel exhaust | 4.72E-08 |

| Selenium exhaust | 6.79E-09 |

| Zinc exhaust | 6.81E-07 |

| Benzene | 9.04E-08 |

| Indeno(1,2,3-cd)pyrene | 4.65E-09 |

| Benzo(k)fluoranthene | 2.02E-08 |

| Benzo(b)fluoranthene | 1.81E-08 |

| Benzo(a)pyrene | 2.99E-09 |

| Dioxins | 5.31E-16 |

| Furans | 7.97E-16 |

| Study | Year | Scenario | Original Value | Original Unit | Original Useful Life | Original Occupancy Factor | Harmonized Value (g CO₂eq/pkm) | ||

| This study (RSE) | Dynamyc 2019-2030 | E-bus (Dynamic IT mix) | 28.5 | g/pkm | 800,000 | 20.4 | 28.5 | ||

| Nordelöf et al. [6] | 2019 | Electric (EU mix) | 48 | g/pkm | 780,000 | 16 | 37.7 | ||

| O’Connell et al [57] | 2021-2040 | BEV (EU grid) | 22.9 | g/pkm | 881000 | 20.4 | 22.9 | ||

| Syré et al [58]. | 2024 | BEV bus (EU) | n.d. | g/km | 70000 |

39 (60*65%) | 24.25 (for Urbino 12 in EU scenario) |

||

| Luu et al. [30] | 2022 | E-bus (Vietnam) | 108.11 | g/pkm | 320000 | 17.8 | 37.8 | ||

| García et al. [24] | 2022 | Electric Bus (total LCA, current) | 12.5 | g/km.passenger | 800,000 | 80 | 49.02 | ||

| Jelti et al. [16] | 2021 | Electric Bus (total WTW) | 5,174 | T CO2 eq/year (fleet) | n.d. | n.d. | 47.02 | ||

| Gabriel et al. [17] | 2021 | Electric Bus (total LCA) | 6.14 × 10⁵ | kg CO2-eq (per bus) | 930,750 | 46 | 32.34 | ||

| Zhao et al. [20] | 2021 | Electric Bus (total LCA, incl. infrastructure) | 690,549.6 | kgCO2e (per station/bus) | 650,000 | n.d. | 52.06 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).