1. Introduction

Classical context. Foundational results on NP-completeness and reductions include Cook’s theorem, Karp’s reductions, and the standard references [

18,

28,

48,

74].

Intractability remains a central obstacle in combinatorial optimization, planning, and decision making. Many canonical problems (such as TSP

1) are, in practice, NP–hard and after decades of effort no polynomial–time algorithm is known for any NP–complete problem. The absence of success is not evidence: proofs of complexity separations are hard, and history warns against arguments from ignorance [

27]. More compelling is the accumulation of

barriers indicating that standard techniques will not resolve the question. Relativization shows that many proof strategies behave the same in oracle worlds where

and where

[

10]; the Natural Proofs framework explains why many combinatorial circuit arguments cannot yield strong lower bounds under widely believed cryptographic assumptions [

66]; and algebrization extends relativization to cover many algebraic techniques [

1]. In parallel, the PCP theorem and its refinements account for the pervasive hardness of approximation [

6,

25,

41]. Together these results suggest that any resolution of

may require ideas well beyond our current toolkit.

This paper does not attempt to settle . Instead, it makes two claims. First, discoverability asymmetry: even if efficient algorithms for NP–complete problems exist, their minimal descriptions may be large (high-K), placing them outside typical human design priors and bounded working memory. Second, pragmatism via automated discovery: with modern compute, we can now systematically search rich program spaces for heuristics, approximation algorithms, and exponential–time improvements, and we can demand machine–checkable certificates so that even opaque artifacts are auditable.

We formalize a time–relative description complexity

for decision, search, and optimization problems (

Section 2), use it to frame the high–

K hypothesis (

Section 2.4), survey automated discovery paradigms with a certificate

2–first protocol (

Section 4), add empirical context from large language models (

Section 4.6), and present concise case studies (

Section 5). We conclude with implications for

and close with a summary of the paper’s main points (

Section 6 and

Section 7).

Terminology.

Throughout this paper we use the phrase certificate-first to denote a discovery workflow in which candidate algorithms or heuristics are only considered scientifically valid when accompanied by machine-checkable evidence (certificate) of correctness or quality. Examples include DRAT/FRAT logs for SAT, LP/SDP dual solutions for optimization, or explicit approximation ratios. In short, discovery may be opaque or high-K (high Kolmogorov complexity), but acceptance requires certificates that can be independently, and efficiently, verified.

2. Background

Algorithmic landscapes. For parameterized algorithms and exact exponential techniques, see [

19,

26]. For a broad overview of computability and complexity notions relevant here, see [

21].

This section lays the theoretical groundwork by defining the complexity classes NP, NP-completeness, and NP-hardness. It provides a detailed discussion of decision problems, the role of oracles, and the importance of polynomial-time verification. Following this, Kolmogorov complexity is defined and extended to include its application to time-complexity asymptotic classes, setting the stage for a discussion of human cognitive limits and algorithmic discoverability.

Dynamic programming is the archetypal example of a low-description but powerful technique, dating back to Bellman’s formulation [

13].

Rice’s theorem reminds us that no algorithm can decide every nontrivial semantic property of programs [

67]; this underlies the uncomputability of

.

2.1. Complexity Classes: NP, NP-Completeness, and NP-Hardness

The study of computational complexity involves classifying problems based on their inherent difficulty and the resources required to solve (optimally, in the case of NP-hard problems) or verify them. This section focuses on the class NP, which consists of decision problems where solutions can be verified in polynomial time, and explores NP-completeness and NP-hardness, which formalize the notions of the most challenging problems within NP and beyond. These classifications form the foundation for understanding the question and the complexity landscape of many practical and theoretical problems.

2.1.1. Decision Problems and the Class NP

Informally, a decision problem is a computational problem where the answer is either "yes" or "no." For example:

Given a Boolean formula, is there an assignment of truth values that satisfies it?

Given a graph G, does there exist a Hamiltonian cycle of length k or less in G?

Given a graph G, does there exist a clique of size k or more in G?

Formally, fix a binary encoding of instances. A

decision problem is a function

We write

for the bit-length of the instance

x.

Problem instances and running time.

Fix a binary encoding of instances; let denote the bit length of a problem instance x. An algorithm runs in polynomial time if its number of steps is for some constant k.

Definition 1 (The Class P.). A decision problem belongs to the class if there exists a deterministic algorithm that, for every input instance x, outputs the correct YES/NO answer in time polynomial in .

Definition 2 (Class NP (via verification).). A decision problem belongs to if there exist (i) a polynomial and (ii) a deterministic Boolean verifier {YES, NO} that runs in time polynomial in , such that the following holds for every instance x:

If the correct answer on x is YES, then there exists a certificate (witness) y with for which accepts.

If the correct answer on x is NO, then for all strings y with , returns NO.

Equivalently,

consists of problems decidable by a

nondeterministic algorithm that halts in polynomial time on every branch and accepts an input iff

there exists at least one accepting branch. Intuitively, the machine “guesses” a short certificate

y and then performs the same polynomial-time check as

. The verifier and nondeterministic definitions coincide; see, e.g., [

74] [Ch. 7].

Thus, for problems in , a short certificate, when it exists, can be checked quickly (in polynomial time).

Example: SAT.

An instance x is a Boolean formula. A certificate y is an assignment to its variables. The verifier evaluates the formula under y and returns YES iff the formula is true. V runs in time polynomial in (and in , which is itself polynomial in ).

Remark. This verifier definition is equivalent to the standard nondeterministic-machine view of , but it avoids machine and language-membership notation and requires no oracle model.

Example (Traveling Salesman Problem). Consider the decision version of the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP-DEC):

Instance. A complete weighted graph on labeled vertices with nonnegative integer edge weights , and a threshold .

Question. Is there a Hamiltonian tour (a permutation of V) whose total weight is at most k?

Certificate (witness). A permutation of the vertices.

Verifier .

All steps run in time polynomial in the input length. Therefore TSP-DEC belongs to via polynomial-time verification.

2.1.2. NP-Completeness

Definition 3 (The Class NP-complete (NPC)). A decision problem L is NP-Complete if:

A Karp reduction transforms, in time that is polynomial in the size of the instance, instances of one problem into instances of another problem .

Definition 4 (

Karp Reduction)

. Let

and

be decision problems. A Karp reduction from

to

, denoted

, is a polynomial-time computable function

f such that for every input instance

x of

, the following holds:

In other words, solving on the transformed input allows us to solve on the original input x, and the transformation f takes time polynomial in the size of x.

Intuitively, this means that if we have an algorithm for , and we can transform any instance of into an instance of using the function f, then we can solve by first applying f and then invoking the algorithm for . The reduction ensures that the "yes"/"no" answer is preserved and that the transformation is efficient (i.e., runs in polynomial time). Note that Karp reduction is a preorder (reflexive and transitive relation).

2.1.3. NP-Hardness

Definition 5. A problem L is NP-hard if every problem in NP can be Karp-reduced to L in polynomial time. Unlike NP-complete problems, NP-hard problems are not required to be in NP, may not be decision problems, and may not have polynomial-time verifiability. For example:

Decision Problems: NP-complete problems, such as SAT, are also NP-hard.

Optimization Problems: Finding the shortest Hamiltonian cycle in a graph is NP-hard but not a decision problem.

Undecidable Problems: Problems such as the Halting Problem are NP-hard but not computable.

NP-hardness generalizes the concept of NP-completeness, capturing problems that are computationally at least as hard as the hardest problems in NP. Note that NP-hard problems may lie outside NP altogether and include problems that are undecidable (such as the Halting Problem, the Busy Beaver Problem, Post’s Correspondence Problem, and others).

2.2. Lemmas and Consequences of Karp Reductions

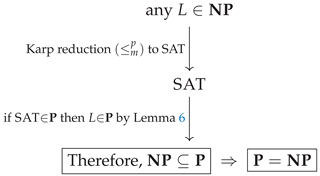

Lemma 6 (Easy-in ⇒ Easy-out). If and , then .

Proof. Given x, compute in polynomial time and run the polynomial-time decider for B on . The composition of two polynomial-time procedures is polynomial. □

Definition 7 (The Class NP-complete (NPC)). A decision problem C is NP-complete iff (i) and (ii) for every , .

Corollary 8. If some NP-complete problem C lies in , then .

Proof. For any , by Definition 7 we have . Since , Lemma 6 implies . Thus , and trivially . □

Why NP-complete problems matter. A single polynomial-time algorithm for any NP-complete problem collapses and by Corollary 8.

Remark (On the use of “collapse”). In complexity theory, a

collapse means that two or more complexity classes that are believed to be distinct are shown to be equal. For example, if any NP-complete problem (such as SAT) admits a polynomial-time algorithm, then every problem in

reduces to it in polynomial time, implying

—a collapse of the two classes. Similarly, the Karp–Lipton theorem shows that if

, then the entire polynomial hierarchy

collapses to its second level,

[

50].

2.2.1. The question

The question asks whether every efficiently

verifiable decision problem is also efficiently

decidable:

If , then all NP-complete problems, such as SAT, would have polynomial-time algorithms. This is precisely because all NP-complete problems can be Karp-reduced to each other. If , then all NP-Hard problems which are non-decision search versions of NP-complete problems will also then have a polynomial time solution.

Why does “one NP-complete problem” suffice?

If C is NP-complete and , then for any problem we have a polynomial-time Karp reduction , so (compose the reduction with the decider for C). Hence . Note that this result is due to the transitivity of .

Consequences if .

All NP-complete problems (e.g.,

SAT,

3-SAT,

Clique,

Hamiltonian Cycle) admit polynomial-time algorithms. Moreover, the associated

search/optimization versions for the usual NP problems also become polynomial-time solvable: using standard

self-reductions, one can reconstruct a witness (or an optimal solution when the decision version is in

P) via polynomially many calls to the decider and polynomial-time bookkeeping.

3

Consequences if .

Then no NP-complete problem lies in P (otherwise the previous paragraph would force ). NP-complete problems are therefore those whose YES answers can be verified quickly (in polynomial time) but, in the worst case, cannot be decided quickly.

2.3. Kolmogorov Complexity

We begin with the original definition of Kolmogorov complexity, which quantifies the informational content of strings based on the length of the shortest algorithm that generates them. We then extend this concept to computational problems, focusing on the complexity of describing solutions or algorithms for such problems. Finally, we further refine the definition to account for the complexity of algorithms within specific asymptotic time classes, particularly polynomial and exponential, in the context of the question.

2.3.1. Definition for Strings

The Kolmogorov complexity

of a string

s[

54] is defined as the length of the shortest (in bits) program

p that outputs

s when executed on a universal Turing machine

U:

This measures the information content or compressibility of the string. For example:

A highly structured string (e.g., "1010101010...") has low Kolmogorov complexity.

A random string has high Kolmogorov complexity because it cannot be compressed.

2.3.2. Kolmogorov (Descriptive) Complexity for Problems

We now extend the definition of Kolmogorov complexity to problems instead of strings.

Fix a universal

prefix Turing machine (TM)

U. The (prefix) Kolmogorov complexity of a finite binary string

s is

By the invariance theorem [

54], changing

U alters

by at most an additive

;

is not computable nor semicomputable [

54] [Chs. 2–3]. We

lift this description-length viewpoint from strings to

problems by measuring the shortest program that solves the problem under a prescribed time budget (complexity class).

Time-relative description complexity (decision/search/optimization).

Let

be a time class (e.g.,

,

). For a decision problem

L with Boolean answer,

with

if no such program runs within

. The same template extends to search relations

(require

to output some valid

y when one exists), to exact optimization (output an optimal feasible solution), and to approximation (output an

-approximate solution), always under the same time budget [

54].

Two special cases.

We will use

that is, the shortest

polynomial-time and

exponential-time solvers, respectively. Concretely, one may write

Remark (Notation). Throughout the paper we use the symbol “” to denote definition by equality. For example, writing means that A is defined to be B, rather than asserting an equation that could be true or false.

Examples.

Sorting has short classical polynomial-time algorithms, so

(and small in absolute terms). For an NP-complete decision problem such as

TSP-DEC, there is a

short exponential-time template: enumerate all candidate certificates of polynomial length and verify each in polynomial time. Hence

and is small up to encoding, whereas the finiteness of

hinges on

[

54,

74] [Thm. NP⊆EXP].

Key properties (decision problems; analogous forms hold for search/optimization).

Finiteness characterizes classes.; . In particular, since , every NP problem (hence every NP-complete problem) has . In simpler terms: if a problem has a finite polynomial-time description length, it means the problem can be solved efficiently; if it only has a finite exponential-time description, then it can be solved (perhaps very slowly) but not efficiently. NP problems fall into the latter category at minimum.

NP via short exponential templates. For any

with polynomial-time verifier

of witness length

, a fixed “enumerate-and-verify’’ schema yields a deterministic

decider; thus

In simpler terms: every NP problem can be solved by the brute-force strategy of trying all possible certificates and checking them. This always gives an exponential-time algorithm with a short description.

Dependence on . If and C is NP-complete, then while ; if , then every has (take the shortest polynomial-time decider). In simpler terms: whether short polynomial-time descriptions exist for NP-complete problems depends on the outcome of the question itself.

Monotonicity across budgets. Whenever both are finite, (a looser time budget cannot increase the shortest description length). In simpler terms: if you allow yourself more time, you never need a longer program to solve the same problem.

Karp Reduction sensitivity. If

and

, then

and

by composing the shortest

C-solver for

B with the polynomial-time Karp reduction

f.

In simpler terms: if problem

A reduces to problem

B, then the complexity of describing a solver for

A is at most the complexity of

B plus the size of the Karp reduction. Karp reductions don’t make things harder to describe.

Orthogonality to running time. Small programs can have huge runtime (e.g., exhaustive certificate enumeration), so description length and time are logically independent—hence the value of the time–relative refinement. In simpler terms: having a short program does not guarantee it runs fast; and running time does not fully capture how complex the program is to describe.

Uncomputability. In general,

cannot be computed or even bounded algorithmically on arbitrary inputs (by standard Kolmogorov arguments; cf. Rice’s theorem on nontrivial semantic properties) [

54].

In simpler terms: there is no algorithm that can always tell you the exact description complexity of a problem, just as there is no algorithm that can decide every nontrivial property of programs.

Low-K exponential templates for NP.

Every

has a constant-length “enumerate certificates and verify” solver running in

time [

74] [§7.3]. This formalizes the intuition that NP-complete problems admit

low-description exponential (often brute-force) algorithms even when efficient ones are unknown [

54].

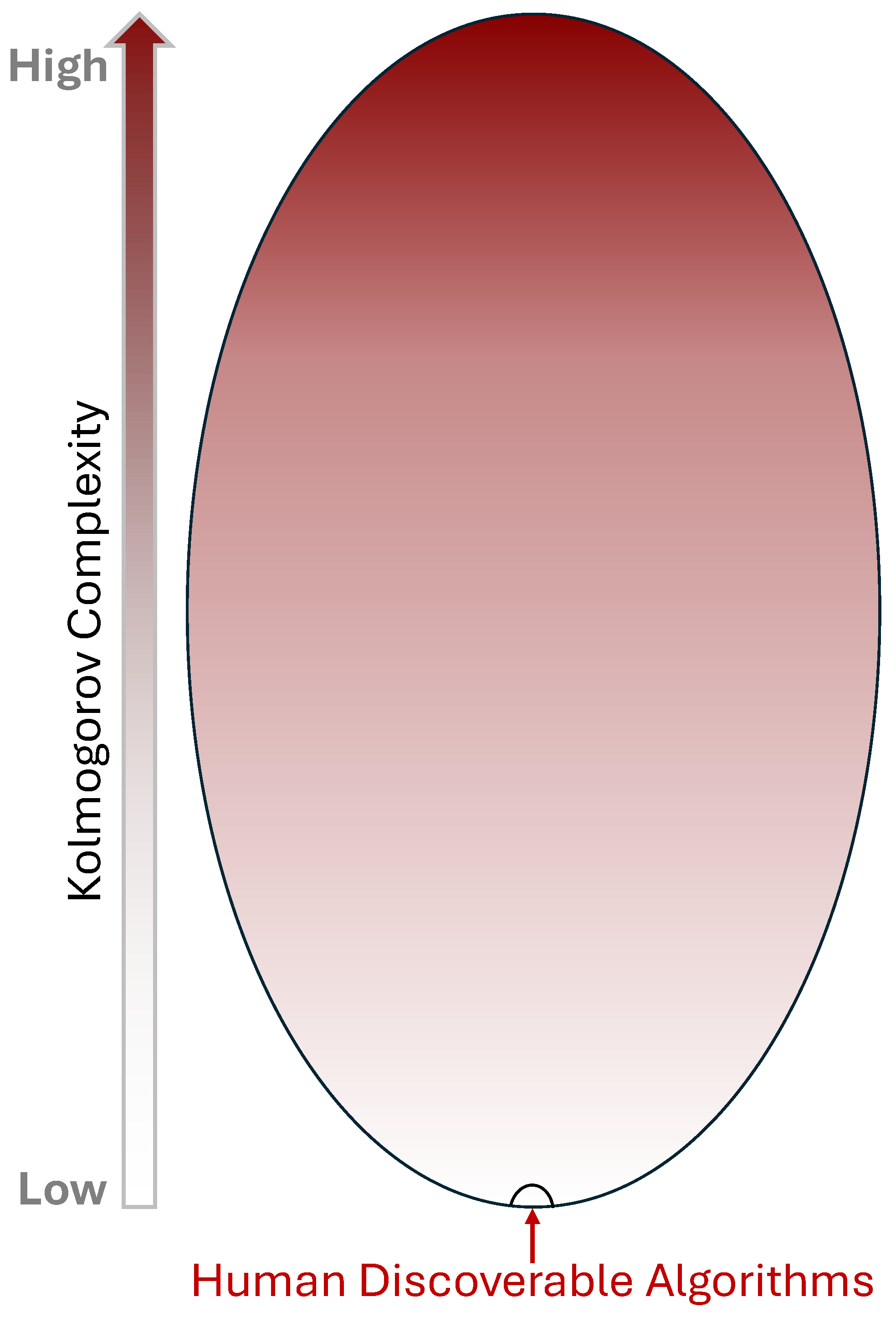

2.4. Human Discoverability of High-Description-Complexity Algorithms (High-K)

The central heuristic of this paper is that

human-discoverable algorithms occupy a tiny, structured region of the full algorithmic design space for problems in

(See

Figure 1). We make this precise by appealing to (i) description complexity, (ii) elementary counting arguments, and (iii) human cognitive limits.

Low description vs. high description.

Let

denote time-relative description complexity (

Section 2.3.2). An algorithm of

low description complexity has a short specification (few lines or a compact program); a

high-

K description algorithm requires a long, intricate specification. Kolmogorov’s framework makes this formal for strings/programs and is machine-independent up to

by the invariance theorem [

54].

Counting intuition.

There are only

binary strings of length

, so only that many programs can be “short.” In contrast, the number of Boolean functions on

n inputs is

, which is astronomically larger. Therefore, almost every function cannot be realized by a short program or a small circuit [

71]. Thus, “most’’ computable behaviors are of high description (or circuit) complexity. Equivalently, concise specifications are rare and high description complexity is typical. We should thus expect many useful procedures to lack short descriptions and to have high Kolmogorov complexity (high-

K).

Cognitive constraints.

Human reasoning favors short, chunkable procedures; working memory and intrinsic cognitive load bound how much unstructured detail we can manipulate [

59,

76]. This induces a discovery bias toward low-

K descriptions with clear modularity, reuse, and mnemonic structure—algorithms we can devise, verify, and teach. By contrast, the program space overwhelmingly contains behaviors whose shortest correct descriptions are long and non-obvious; hence many effective procedures may sit in high-Kolmogorov-complexity regions (high-

K) that exceed routine human synthesis. It is therefore plausible that a significant subset of practically valuable algorithms are high-

K and rarely found by unaided insight. A pragmatic response is to employ large-scale computational search—program synthesis, evolutionary search, neural/architecture search, meta-learning—under constraints and certificates (tests, proofs, invariants) to explore these regions safely. In short, cognitive bounds shape our algorithmic priors toward brevity and structure, while powerful compute can systematically probe beyond them to surface useful but non-succinct procedures.

NP problems as a case study.

Every

admits a

low-description a short exponential-time template that enumerates certificates and verifies them in polynomial time.

is therefore finite and typically small up to encoding [

54,

74] [Thm. NP⊆EXP]. For an NP-complete

C,

Hence the empirical asymmetry: short

inefficient algorithms are easy (templates exist), whereas any

efficient algorithm, if it exists, might sit at high description complexity, beyond typical human cognitive limits and discoverability.

Interpretation and limits.

This “high-K efficient algorithm’’ hypothesis is heuristic, not a statement about the truth of . It offers a plausible explanation for why decades of human effort have yielded powerful heuristics and proofs of hardness/limits, but no general polynomial-time algorithms for NP-complete problems. It also motivates automated exploration of high-description code spaces, coupled with machine-checkable verification (certificates, proofs, oracles in the promise sense when appropriate), to make discovery scientifically testable.

With these preliminaries in place, we now review structural barriers (relativization, Natural Proofs, algebrization, PCP-driven hardness) that temper expectations of simple polynomial-time solutions and motivate the later emphasis on capacity-driven automated discovery with machine-checkable certificates.

3. Structural Barriers to the Existence of Efficient Algorithms for NP-Hard Problems

It is well known that if a single NP-complete problem were to be solved in polynomial time, then all problems in NP would be solvable in polynomial time. Therefore,

. The implications of such a result would be profound. Many cryptographic protocols rely on problems that are believed to be hard on average [

7]. If

, then these assumptions could no longer be sustained.

Despite decades of effort by leading researchers, no polynomial-time algorithm has been discovered for any NP-complete problem. This sustained lack of progress is often interpreted as indirect evidence that

, but such an argument remains speculative. The absence of success does not constitute a proof, and history provides examples where long-standing open problems were eventually resolved in unexpected ways [

3,

4,

35,

79].

However, there are deeper theoretical reasons why many in theoretical computer science believe that . A number of landmark results appear to impose structural barriers to proving or to the existence of simple polynomial-time algorithms for NP-complete problems. In particular, the following are frequently cited:

The

Karp–Lipton theorem, which shows that if

, then the polynomial hierarchy collapses to its second level [

49].

The

Natural Proofs barrier, introduced by Razborov and Rudich (1997), which argues that many existing circuit-lower-bound techniques are unlikely to resolve the

question under standard cryptographic assumptions [

66].

The

Probabilistically Checkable Proofs (PCP) theorem, which underlies strong hardness-of-approximation results for many NP-hard problems [

6].

3.1. The ETH/SETH Context

ETH. There is no

-time algorithm for 3-SAT [

44].

SETH. For every

there exists

k such that

k-SAT cannot be solved in time

[

43].

These conjectures provide a calibrated backdrop for “better-exponent’’ goals: under ETH, many classic NP-hard problems are unlikely to admit subexponential-time algorithms, and SETH yields fine-grained lower bounds for k-SAT and related problems. This paper’s methodology—capacity-driven automated discovery in high-K spaces, coupled with machine-checkable certificates—is compatible with ETH and SETH: we target smaller exponential bases, improved constants, and broader fixed-parameter tractability, without asserting subexponential algorithms where these conjectures preclude them.

Interpretive note. ETH/SETH concern running time, not descriptional complexity. They do not imply that any efficient algorithm for an NP-complete problem must have high Kolmogorov complexity. Our claim is heuristic: taken together with known proof-technique barriers, these conjectures suggest that if polynomial-time algorithms for NP-complete problems exist, they are unlikely to arise from today’s simple, low-description techniques. In that sense, such algorithms—if they exist—may reside in high-K regions of the design space, beyond unaided human discoverability.

The remainder of this section expands on the above theoretical results in turn.

3.2. The Karp–Lipton Theorem

The

Karp–Lipton Theorem, established in 1982, provides a significant structural implication regarding the class

and non-uniform computation. It states that if

, then the polynomial hierarchy (PH) collapses to its second level:

If

, then

.

4

In other words, if nondeterministic polynomial-time problems can be solved by deterministic polynomial-time machines with polynomial-size advice strings (non-uniform circuits), then the polynomial hierarchy, which is believed to be infinite, collapses very low. This would be a surprising outcome, since it would contradict the presumed richness of PH. Given that

is often used to model the power of non-uniform algorithms or hardware circuits, the theorem suggests that any proof of

via circuit complexity must overcome this potential collapse. This result is one of the early indications that nontrivial structural implications follow from seemingly local containments.

3.3. The Natural Proofs Barrier

Razborov and Rudich introduced the

Natural Proofs framework to explain why many circuit-lower-bound techniques may not scale to separate

from

[

66] (see also [

7] [§20.4]). A

property of Boolean functions on

n inputs (i.e., a subset

of all truth tables of size

) is called:

Large if it holds for a non-negligible fraction of functions, e.g., .

Constructive if, given a function’s truth table (length ), membership can be decided in time (equivalently, by circuits of size ).

Useful against a circuit class (e.g., ) if no function computable by -circuits of size lies in , yet some explicit hard family satisfies for infinitely many n.

Barrier (conditional).

Assuming the existence of strong pseudorandom objects secure against -circuits, there is no property that is simultaneously large, constructive, and useful against

[

66]. In particular, under these cryptographic assumptions one cannot prove super-polynomial circuit lower bounds for

via

natural properties.

Scope and limits.

The barrier explains why many “combinatorial’’ methods (which typically yield large and constructive properties) are unlikely to resolve by circuit lower bounds. It does not show that is unprovable: it leaves room for (i) non-constructive arguments, (ii) non-large (very sparse) properties, and (iii) targets for which the requisite pseudorandom objects are not known to exist. Consequently, progress likely requires techniques that avoid naturalness relative to the targeted circuit class or that circumvent the cryptographic assumptions.

3.4. The PCP Theorem and the Hardness of Approximation

The

Probabilistically Checkable Proofs (PCP) theorem revolutionized our view of

: membership can be verified by inspecting only a few proof bits at random. The canonical form states

i.e., there are constants

such that every

has a proof that a verifier checks using

random bits and

q queries, with completeness 1 and soundness

; see [

6].

Consequences for approximation.

PCP machinery yields gap reductions showing that even approximate solutions are hard:

Max-3SAT: No polynomial-time algorithm can achieve a ratio better than

for any

unless

[

41].

Vertex Cover: Approximating within factor

is NP-hard [

20]; the best known ratio is 2.

Set Cover: Approximating within

is hard unless

[

25].

Max Clique/Chromatic Number: -approximation is NP-hard for any fixed

[

84].

Thus, even under relaxed objectives (constant or logarithmic factors), many classic -complete problems remain intractable to approximate in polynomial time. This strengthens the view that exact polynomial-time algorithms are unlikely and motivates the search for problem-structured heuristics with provable—yet necessarily limited—approximation guarantees.

4. Automated Algorithm/Heuristic Discovery: A New Frontier

Automated discovery, as used here, grows out of familiar lines of work. From empirical algorithms comes the idea of portfolios and automatic configuration, where strength comes from choosing well rather than insisting on a single universal solver [

32,

83]. From learning-augmented algorithms comes the view that predictions can serve as advice, with safeguards that limit the damage when the advice is wrong [

56,

60,

63]. From implicit computational complexity comes polytime-by-construction design, in which the language itself carries the resource discipline [

12].

The aim is not to propose a fixed pipeline but to suggest a change in perspective. With modern compute it now becomes feasible to explore program spaces that extend far beyond what can be examined by hand. What matters is not opacity for its own sake, but reach: compact templates and systematic search may surface high–K procedures that would be hard for humans to invent directly. Credibility then follows from what travels with the code—logs, proofs, and dual bounds—so that claims can be checked and trusted on an instance-by-instance basis.

What follows offers a shared vocabulary and a few recurring patterns of discovery. The targets remain concrete: better approximations within known floors, broader fixed-parameter regimes, and smaller exponential bases, together with the evidence that allows such results to enter practice.

4.1. Definitions (Model-Agnostic)

For clarity, we use the following terms informally and in line with standard texts.

-

Heuristic.

A polynomial-time procedure that returns a feasible decision or solution on every input, typically without a worst-case optimality bound [

62]. Randomized variants run in expected polynomial time or succeed with high probability.

-

Approximation algorithm.

For minimization with optimum

, an algorithm

A is an

-approximation if

for all instances of size

n, with polynomial running time (and analogously for maximization). Canonical regimes include constant-factor, PTAS/EPTAS, and polylogarithmic-factor approximations [

77,

81].

-

Meta-heuristic.

A higher-level search policy—e.g., evolutionary schemes, simulated annealing, or reinforcement learning—that explores a space of concrete heuristics or pipelines adapted to a target distribution [

22,

51].

-

Algorithmic discovery system.

Given a design space

(programs, relaxations, proof tactics), a distribution

, and an objective

J (e.g., certified gap or runtime), the system searches for

that scores well under

J within resource limits, and emits

certificates when applicable (dual bounds, proof logs) [

7,

14].

4.2. Discovery Paradigms

There is no single road to discovery; several strands point in the same direction. One is

search and synthesis: local or stochastic search over code and algorithmic skeletons with equivalence checking (Massalin’s

Superoptimizer; STOKE) [

58,

70], SAT/SMT-guided construction of combinatorial gadgets such as optimal sorting networks [

16], and recent reinforcement-learning setups for small algorithmic kernels [

57].

Another is

learning-guided generation. Systems that generate or repair code by tests and specifications (e.g., AlphaCode) and program search guided by LLMs with formal validation (e.g., FunSearch) show how statistical guidance and verification can coexist [

53,

68].

A third strand is

neuro-symbolic structure. Syntax-guided synthesis (SyGuS), equality saturation with e-graphs, and wake–sleep library growth (DreamCoder) combine search with inductive bias from symbolic structure [

2,

23,

82].

Finally,

evolutionary and RL approaches remain natural for routing, scheduling, and solver control (e.g., learned branching or cutting policies), where compact policies can be discovered and then judged by certificates [

22,

29,

52,

61]. Across these cases the theme is consistent: capacity broadens the search; structure and checking keep results grounded.

4.3. Targets for Approximation and Heuristics

Reductions and relaxations. Automated reductions, LP/SDP relaxations, and learned policies for branching and cutting provide a flexible substrate. Dual-feasible solutions and lower bounds certify quality, while SAT-family problems admit independently checkable proof logs [

7,

14].

Rounding schemes. Classical rounding ideas can be viewed as templates to explore, with guarantees inherited from the template: randomized rounding [

64], SDP-based rounding such as Goemans–Williamson for MAX-CUT [

31], and metric embeddings that translate structure into approximation [

24].

Algorithmic skeletons. Sound skeletons—local search with a potential function, primal–dual methods, greedy with exchange arguments—set the envelope of correctness. Searched or learned choices (moves, neighbors, tie-breaks) then tune behavior within that envelope [

77,

81].

4.4. Evidence and Evaluation

Because this is a position paper, the emphasis is on what tends to constitute persuasive evidence. Correctness comes first: constraint checks for feasibility; for decision tasks, proof logs or cross-verified certificates where available. When worst-case guarantees exist they should be stated; where they are out of reach, per-instance certified gaps via primal–dual bounds are informative. Efficiency is often clearer from anytime profiles—solution quality over time on fixed hardware—than from a single headline number. Generalization benefits from clean train/test splits, stress outside the training distribution, and simple ablations for learned components. Reproducibility follows from releasing code, seeds, models, datasets, and the verification artifacts (certificates and any auxiliary material needed to independently check results such as proofs, logs, or even counterexamples) themselves.

4.5. High-K Perspective, Limits, and Compute as an Enabler

High-

K artifacts—large parameterizations or intricate codelets—may lie beyond familiar design priors yet remain straightforward to

verify. The working view is that worst-case optimality for canonical NP-hard problems is unlikely, so practice leans on heuristics and approximations; automated discovery, constrained by polytime-by-construction scaffolds and paired with certificates, offers a way to surface stronger ones and, at times, to tighten provable bounds. Compute changes what is plausible: modern compute clusters make it realistic to explore vast program spaces, from code optimization to small-scale algorithm design [

53,

57,

68,

70]. The same scale brings predictable risks—benchmark overfitting, reward hacking, unverifiable “speedups,” distribution shift—that are best mitigated by certified outputs, standard verification tools, and transparent reporting.

4.6. Observations from LLMs and Scaling

Large language models (LLMs) illustrate how increased capacity (number of model parameters) can unlock qualitatively new behavior and abilities. Empirical scaling laws show that test loss decreases in a predictable way with more parameters, more data, and more compute, and compute-optimal training balances these factors [

40,

47]. In practice, models exhibit

emergent properties: abilities that do not appear in small systems but manifest once scale crosses a threshold. A natural interpretation is that the learned mapping from input tensors to output tensors is often

high in description complexity (high–

K). Larger parameter budgets can encode more intricate, complex, functions, and scaling increases the probability that training discovers such mappings. This is not evidence about

, but it is an empirical lesson about search: higher capacity explores larger regions of algorithmic space. A natural hypothesis is that the learned mappings may be high in description complexity; larger parameter budgets (capacity) increase the probability of reaching such functions.

Human neurobiology points in the same direction. The human brain contains approximately

neurons, is estimated to have

–

synaptic connections, and consumes about

of the body’s resting metabolic energy [

8,

17,

39,

46,

65]. Humans also have a high encephalization quotient [

39,

45] relative to body size. It is reasonable to view human intelligence itself as a high–

K phenomenon: large capacity and dense connectivity are, it appears, required to support it.

Nature and modern machine learning both suggest that capacity and scale matter (but may not necessarily be sufficient to achieve AGI). It is therefore reasonable to hypothesize that the high–K space of algorithms—too intricate for humans to discover unaided—may contain useful heuristics and approximation algorithms for many hard problems.

5. Case Studies: Applying the Workflow

This section is illustrative. It shows how the certificate-first workflow may apply to canonical problems. It does not present experiments. The goal is to make the method concrete without prescribing one toolchain.

A workable protocol.

(1) Fix a task and an instance distribution. (2) Choose baselines users already trust. (3) Specify a compact search space or DSL and a proxy for description length (e.g., AST nodes or compressed size). (4) Require machine-checkable certificates. (5) Report practical metrics: gap, time-to-target, success rate, fraction certified.

5.1. SAT (CNF)

Targets. Better branching, clause learning, and clause-deletion policies.

Search space. Small policies over clause and variable features; proxy-

K by AST size or token count.

Certificates. Verify UNSAT with DRAT/FRAT; validate SAT by replaying assignments [

9,

15,

78].

Context. Portfolios and configuration improve robustness; they integrate naturally with certificate-first outputs [

32,

83].

Outcome. A discovered policy is acceptable once it produces proofs or checkable models on the target distribution.

5.2. Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP)

Targets. Lower tour gaps and stronger anytime behavior.

Search space. Insertion rules or LKH parameter templates; proxy-

K by rule length [

38].

Certificates. Use 1-tree and related relaxations as lower bounds; export tours and bounds with Concorde-style utilities [

5,

37].

Outcome. A policy is credible when tours come with lower bounds that certify the reported gaps.

5.3. Vertex Cover and Set Cover

Targets. Simple rounding and local-improvement templates.

Search space. Short heuristics that map LP or greedy features to choices; proxy-

K by template length.

Certificates. Dual-feasible solutions certify costs; hardness thresholds calibrate expectations [

11,

20,

25,

64].

Outcome. New templates are useful when they offer certified gaps or better anytime profiles on the intended distribution.

5.4. Learning-Augmented and Discovery Tools

Role. Predictions serve as advice with robustness guarantees; portfolios hedge uncertainty [

56,

60,

63,

83]. Program search and RL can propose compact rules; superoptimization and recent discovery systems show feasibility on small domains [

16,

53,

57,

58,

68,

70]. Certificate-first turns such proposals into auditable artifacts.

Scope.

This is a position paper. The section does not claim superiority over mature solvers. It shows how to pair capacity and search with certificates and structure so that high-description solutions—if found—are scientifically usable.

6. Implications for

If , then the longstanding intuition is confirmed: exact polynomial-time algorithms for NP-complete problems are, in the worst case, out of reach. This does not close off progress, but it shifts what “progress” means. Advances then come from approximation, from exploiting structure through parameterized approaches, from tightening exponential-time algorithms, or from combining diverse methods into robust portfolios. Each of these directions represents ways of doing better even when the ultimate barrier remains.

Seen in this light, the focus moves away from hoping for a breakthrough algorithm that overturns complexity theory, and toward a pragmatic exploration of what can be achieved within known limits. Certificates and verifiable relaxations are valuable because they allow even opaque or high-complexity procedures to be trusted. If P were ever shown equal to , the same emphasis on auditable artifacts would still matter: high-K algorithms would need to be made scientifically usable.

The broader implication is that the question, while unresolved, should not dominate practice. Assuming encourages a reframing: instead of waiting for resolution, we can treat complexity-theoretic limits as the backdrop against which useful heuristics, approximations, and verifiable improvements are sought.

7. Discussion and Conclusions

This paper encourages a pragmatic way of thinking about algorithm design: to look beyond human discoverability and explore high-description-complexity (high-K) spaces, while at the same time keeping the search anchored to certificates. Even without resolving the celebrated question of , this pairing—capacity for discovery combined with auditable evidence—suggests a pathway to heuristics and approximation procedures that improve practice and, in some cases, may, in some cases, tighten known bounds.

The emphasis here is less on deriving algorithms that are simple to narrate and more on treating discovery itself as an object of study. Capacity-rich systems can explore design spaces that are beyond the reach of manual reasoning. When such explorations are paired with epistemic safeguards—SAT proof logs such as DRAT and FRAT, LP and SDP dual bounds, 1-tree relaxations, or equivalence checking—artifacts become auditable, examinable and, therefore, trustworthy. In this reframing, understanding shifts from producing hand-crafted algorithms to verifying the correctness of artifacts and bounding their behavior.

Assuming , exact polynomial-time algorithms for NP-complete problems do not exist. Progress must then be understood in other terms: stronger approximation methods within known hardness floors, parameterized techniques that exploit hidden structure, incremental improvements to exponential-time algorithms, or more robust combinations of solvers into portfolios. What counts as success in this setting is not a definitive breakthrough but the production of efficiently computable procedures whose reliability is guaranteed by independent certification rather than by intuitive transparency.

The practical implications are wide-ranging but deliberately domain-agnostic. In Satisfiability and related constraint settings, proof logs render unsatisfiability claims independently checkable. In graph optimization and routing, dual bounds and relaxations serve the same purpose. Discovery costs can be absorbed offline; what is ultimately deployed remains polynomial-time and auditable instance by instance. This way, even when artifacts are opaque or high-K, their use can be grounded in verifiable evidence.

Of course, there are limitations and risks. High-K artifacts may be brittle, or they may conceal dependencies that are difficult to manage. Certification mitigates some of these issues but does not eliminate them. Benchmarks can be overfit; distributions may shift; compute and energy costs are real. Claims of speed or optimality carry weight only when they are tied to released artifacts—code, seeds, models, and certificates—so that they can be checked, validated, and reproduced.

Several open directions suggest themselves. Polytime-by-construction DSLs might be extended with richer expressivity. Neuro-symbolic approaches could combine relaxations and rounding with machine-checked proofs. Transfer across problems may be possible through embeddings or e-graphs, provided certification is preserved. Learning-augmented and portfolio methods can offer robustness against distributional uncertainty. Community benchmarks, finally, would benefit from requiring not only solutions but also certificates of correctness.

The broader message is a methodological shift. For too long, algorithm design has tacitly assumed an anthropocentric stance: that useful algorithms are, by necessity, those that humans can both discover and comprehend. We suggest that this is a limiting assumption. Experience from AI systems such as AlphaGo [

72,

73], whose non-intuitive, high complexity, strategies surpass human design patterns, demonstrates that effective procedures need not be low complexity and thus human-discoverable. This challenges the implicit (or unconscious) assumption that usefulness coincides with human discoverability. An often quoted example of how AI (in this case AlphaGo) finds strong, non-intuitive strategies is the now famous

Move 37 [

36]. Nature itself, with the scale and complexity of the human brain, makes a similar point –

capacity does matter. Structural results such as the Karp–Lipton theorem, the Natural Proofs barrier, and the PCP theorem indicate that general polynomial-time breakthroughs for NP-complete problems are unlikely. Yet with modern compute, it now becomes possible to systematically search high-dimensional spaces for heuristics and approximations that are high-

K and beyond unaided human reach. If paired with verification, these opaque discoveries can still be rendered scientifically usable.

Lineage. Our stance follows a long tradition of algorithmic discovery by search and learning: from superoptimization and code synthesis [

58,

70], through syntax-guided and neuro-symbolic methods [

2,

23,

82], portfolio/configuration approaches [

32,

83], and recent large-scale program-search systems [

53,

57,

68]. Our contribution is not the idea of discovery by compute, but a consolidated

capacity + certificates perspective that treats high–

K exploration as routine and insists that new artifacts arrive with machine-checkable evidence.

In short, progress can be made systematic by bringing together capacity and search with certificates and structure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, JA; methodology, JA; validation, JA, CL, and EC; formal analysis, JA; investigation, JA; resources, JA, CL, and EC; writing—original draft preparation, JA; writing—review and editing, JA, CL, EC; visualization, JA; supervision, JA, CL, EC; project administration, JA, CL, and EC. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the use of ChatGPT

5 during the preparation of this manuscript, specifically for validating and formatting the bibliography and for suggestions to improve the clarity of the prose. All generated material was reviewed and edited by the authors, who accept full responsibility for the final content.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| AST |

Abstract Syntax Tree |

| B&B |

Branch-and-Bound |

| CP |

Constraint Programming |

| DP |

Dynamic Programming |

| DRAT |

Deletion/Resolution Asymmetric Tautology |

| DSL |

Domain-Specific Language |

| DTIME |

Deterministic Time |

| EXP |

Exponential Time |

| FFD |

First-Fit Decreasing |

| FNP |

Function Nondeterministic Polynomial Time |

| FP |

Function Polynomial Time |

| FRAT |

Flexible RAT |

| FPTAS |

Fully Polynomial-Time Approximation Scheme |

| GP |

Genetic Programming |

| high-K

|

High Kolmogorov Complixity |

| IL |

Imitation Learning |

| LKH |

Lin–Kernighan–Helsgaun heuristic |

| LP |

Linear Programming |

| low-K

|

Low Kolmogorov Complixity |

| MaxSAT |

Maximum Satisfiability |

| MDL |

Minimum Description Length |

| MIP |

Mixed-Integer Programming |

| NP |

Nondeterministic Polynomial Time |

| NPC |

NP-Complete |

| OOD |

Out-of-Distribution |

| P |

Polynomial Time |

| PCP |

Probabilistically Checkable Proofs |

| PH |

Polynomial Hierarchy |

| PTAS |

Polynomial-Time Approximation Scheme |

| P/poly |

Polynomial-Size Advice (Non-uniform) |

| RL |

Reinforcement Learning |

| SAT |

Boolean Satisfiability |

| SDP |

Semidefinite Programming |

| TM |

Turing Machine |

| TSP |

Travelling Salesman Problem |

| TSP-DEC |

Travelling Salesman Problem (Decision) |

|

Second Level of the Polynomial Hierarchy (Pi) |

|

Second Level of the Polynomial Hierarchy (Sigma) |

| TTT ()Time-to-target) |

Time to reach a pre-set quality threshold |

References

- Aaronson S. and Wigderson A. “Algebrization: A New Barrier in Complexity Theory.” ACM Transactions on Computation Theory 1, no. 1 (2009): Article 2. [CrossRef]

- Alur R., et al. “Syntax-Guided Synthesis.” In FMCAD 2013: Formal Methods in Computer-Aided Design, 1–8. Austin, TX: FMCAD, 2013.

- Appel K., and Haken W. “Every Planar Map Is Four Colorable. Part I: Discharging.” Illinois Journal of Mathematics 21, no. 3 (1977): 429–490. [CrossRef]

- Appel K., Haken W., and Koch J. “Every Planar Map Is Four Colorable. Part II: Reducibility.” Illinois Journal of Mathematics 21, no. 3 (1977): 491–567. [CrossRef]

- Applegate D.L., Bixby R.E., Chvátal V., and Cook W.J. The Traveling Salesman Problem: A Computational Study. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006.

- Arora S., Lund C., Motwani R., Sudan M., and Szegedy M. “Proof Verification and the Hardness of Approximation Problems.” Journal of the ACM 45, no. 3 (1998): 501–555. [CrossRef]

- Arora S., and Boaz B. Computational Complexity: A Modern Approach. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Azevedo F.A.C., Carvalho L.R.B, Grinberg L.T., et al. “Equal Numbers of Neuronal and Nonneuronal Cells make the Human Brain an Isometrically Scaled-up Primate Brain.” Journal of Comparative Neurology 513, no. 5 (2009): 532–541. [CrossRef]

- Baek S., Carneiro M., and Heule M.J.H. “A Flexible Proof Format for SAT Solver-Elaborator Communication (FRAT).” Logical Methods in Computer Science 18, no. 2 (2022): 3:1–3:21. [CrossRef]

- Baker T., Gill J., and Solovay J. “Relativizations of the P =? NP Question.” SIAM Journal on Computing 4, no. 4 (1975): 431–442. [CrossRef]

- Bar-Yehuda R., and Even S. “A Local Ratio Theorem for Approximating the Weighted Vertex Cover Problem.” Annals of Discrete Mathematics 25 (1985): 27–46. (Preliminary version, 1981. [CrossRef]

- Bellantoni S., and Cook S. “A New Recursion-Theoretic Characterization of the Polytime Functions.” Computational Complexity 2 (1992): 97–110. [CrossRef]

- Bellman R. Dynamic Programming. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1957.

- Bertsimas D., Tsitsiklis J.N. Introduction to Linear Optimization. Belmont, MA: Athena Scientific, 1997.

- Biere A., Heule M., van Maaren H., and Walsh T., eds. Handbook of Satisfiability. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence and Applications 185. Amsterdam: IOS Press, 2009.

- Bundala D., and Závodný J. “Optimal Sorting Networks.” In SAT 2014: Theory and Applications of Satisfiability Testing, 236–250. Berlin: Springer, 2014.

- Clarke D.D., and Sokoloff L. “Circulation and Energy Metabolism of the Brain.” In Basic Neurochemistry: Molecular, Cellular and Medical Aspects, 6th ed., edited by G. J. Siegel et al. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1999.

- Cook S.A. “The Complexity of Theorem-Proving Procedures.” In Proceedings of the Third Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing (STOC ’71), 151–158. New York: ACM, 1971.

- Cygan M, Fomin F.V., Kowalik T., Lokshtanov D., Marx D., Pilipczuk M., Pilipczuk M., and Saurabh S. Parameterized Algorithms. Cham: Springer, 2015.

- Dinur I., and Safra S. “On the Hardness of Approximating Minimum Vertex Cover.” Annals of Mathematics 162, no. 1 (2005): 439–485. [CrossRef]

- Downey R. “Computational Complexity.” In Computability and Complexity: Foundations and Tools for Pursuing Scientific Applications, 159–176. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Eiben A. E., and Smith J. E. Introduction to Evolutionary Computing. Berlin: Springer, 2003.

- Ellis K., Wong C., Nye M., et al. “DreamCoder: Growing Libraries of Concepts with Wake-Sleep Program Induction.” In PLDI 2021: Proceedings of the 42nd ACM SIGPLAN Conference on Programming Language Design and Implementation, 835–850. New York: ACM, 2021.

- Fakcharoenphol J., Rao S., and Talwar K. “A Tight Bound on Approximating Arbitrary Metrics by Tree Metrics.” Journal of Computer and System Sciences 69, no. 3 (2004): 485–497. [CrossRef]

- Feige U. “A Threshold of ln n for Approximating Set Cover.” Journal of the ACM 45, no. 4 (1998): 634–652. [CrossRef]

- Fomin F.V., and Kratsch D. Exact Exponential Algorithms. Berlin: Springer, 2010.

- Fortnow L. “The Status of the P versus NP Problem.” Communications of the ACM 52, no. 9 (2009): 78–86. [CrossRef]

- Garey M.R., and Johnson D.S. Computers and Intractability: A Guide to the Theory of NP-Completeness. New York: W. H. Freeman, 1979.

- Gasse M. Chételat D., Ferroni N., Charlin L., and Lodi A. “Exact Combinatorial Optimization with Graph Convolutional Neural Networks.” In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2019), 15554–15566. 2019.

- Gilmore P.C., and Gomory R.E. “A Linear Programming Approach to the Cutting-Stock Problem.” Operations Research 9, no. 6 (1961): 849–859. [CrossRef]

- Goemans M.X., and Williamson D.P. “Improved Approximation Algorithms for Maximum Cut and Satisfiability Problems Using Semidefinite Programming.” Journal of the ACM 42, no. 6 (1995): 1115–1145. [CrossRef]

- Gomes C.P., and Selman B. “Algorithm Portfolios.” Artificial Intelligence 126, no. 1–2 (2001): 43–62. [CrossRef]

- Gomory R.E. “A Linear Programming Approach to the Cutting Stock Problem-Part II.” Operations Research 11, no. 6 (1963): 863–888. [CrossRef]

- Gonthier G. “Formal Proof-The Four-Color Theorem.” Notices of the American Mathematical Society 55, no. 11 (2008): 1382–1393. [CrossRef]

- Hales T.C. “A Proof of the Kepler Conjecture.” Annals of Mathematics 162, no. 3 (2005): 1065–1185. [CrossRef]

- Hassabis D. “What We Learned in Seoul with AlphaGo.” Google The Keyword (blog), March 16, 2016. https://blog.google/technology/ai/what-we-learned-in-seoul-with-alphago/.

- Held M. and Karp R.M. “The Traveling-Salesman Problem and Minimum Spanning Trees.” Operations Research 18, no. 6 (1970): 1138–1162. [CrossRef]

- Helsgaun K. “An Effective Implementation of the Lin–Kernighan Traveling Salesman Heuristic.” European Journal of Operational Research 126, no. 1 (2000): 106–130. [CrossRef]

- Herculano-Houzel S. “The remarkable, yet not extraordinary, human brain as a scaled-up primate brain.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109, suppl. 1 (2012): 10661–10668. [CrossRef]

- arXiv:2203.15556.Hoffmann J., Borgeaud S., Mensch A., Buchatskaya E., Cai T., Rutherford E., de Las Casas D., et al. “Training Compute-Optimal Large Language Models.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35 (NeurIPS 2022). Also available as arXiv:2203.15556.

- Håstad J. “Some Optimal Inapproximability Results.” Journal of the ACM 48, no. 4 (2001): 798–859. [CrossRef]

- Ibarra O.H., and Kim C.E.. “Fast Approximation Algorithms for the Knapsack and Sum of Subset Problems.” Journal of the ACM 22, no. 4 (1975): 463–468. [CrossRef]

- Impagliazzo R., Paturi R., and Zane F. "Which Problems Have Strongly Exponential Complexity?" Journal of Computer and System Sciences 63, no. 4 (2001): 512–530. [CrossRef]

- Impagliazzo R., Paturi R. "On the Complexity of k-SAT." Journal of Computer and System Sciences 62, no. 2 (2001): 367–375. [CrossRef]

- Jerison H.J. Evolution of the Brain and Intelligence. New York: Academic Press, 1973.

- Kandel E.R., Schwartz J.H., Jessell T.M., Siegelbaum S.A, and Hudspeth A.J., eds. Principles of Neural Science. 5th ed. New York: McGraw–Hill Medical, 2013.

- arXiv:2001.08361, 2020.Kaplan J., McCandlish S., Henighan T, Brown T.B., Chess B., Child R., Gray S., Radford A., Wu J., and Amodei D. “Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2001.08361, 2020.

- Karp R.M. "Reducibility Among Combinatorial Problems.” In Complexity of Computer Computations, edited by R. E. Miller and J. W. Thatcher, 85–103. New York: Plenum Press, 1972.

- Karp R.M., and Lipton R.J. “Some Connections Between Nonuniform and Uniform Complexity Classes.” In Proceedings of the Twelfth Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing (STOC ’80), 302–309. New York: ACM, 1980.

- Karp R.M., and Lipton R.J. “Turing Machines That Take Advice.” L’Enseignement Mathématique 28, no. 3–4 (1982): 191–209. [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick S., Gelatt Jr. C.D., and Vecchi M.P. “Optimization by Simulated Annealing.” Science 220, no. 4598 (1983): 671–680. [CrossRef]

- Kool W., van Hoof H., and Welling M. “Attention, Learn to Solve Routing Problems!” International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2019. [CrossRef]

- Li Y., Choi D., Chung J., et al. “Competition-Level Code Generation with AlphaCode.” Science 378, no. 6624 (2022): 1092–1097. [CrossRef]

- Li M., and Vitányi P. An Introduction to Kolmogorov Complexity and Its Applications. 4th ed. New York: Springer, 2019.

- Lovász L. “On the Shannon Capacity of a Graph.” IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 25, no. 1 (1979): 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Lykouris T., and Vassilvitskii S. “Competitive Caching with Machine Learned Advice.” In Proceedings of NeurIPS 2018, 3303–3312. [CrossRef]

- Mankowitz D.J., Michi A., Zhernov A., et al. “Faster Sorting Algorithms Discovered Using Deep Reinforcement Learning.” Nature 618 (2023): 257–263. [CrossRef]

- Massalin H. “Superoptimizer: A Look at the Smallest Program.” In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems (ASPLOS-II), 122–126. New York: ACM, 1987.

- Miller G.A. “The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information.” Psychological Review 63, no. 2 (1956): 81–97. [CrossRef]

- Mitzenmacher M., and Vassilvitskii S. “Algorithms with Predictions.” Communications of the ACM 64, no. 6 (2021): 86–96. [CrossRef]

- Paulus M., Paulus M.B., Goodman N.D., and Yue Y. “Learning to Cut by Looking Ahead: Cutting Plane Selection via Imitation Learning.” In International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML 2022), 17573–17593. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Pearl J. Heuristics: Intelligent Search Strategies for Computer Problem Solving. Reading, MA: Addison–Wesley, 1984.

- Purohit M., Svitkina Z., and Kumar R.. “Improving Online Algorithms via ML.” In Proceedings of NeurIPS 2018, 9661–9670. [CrossRef]

- Raghavan P., and Thompson C.D. “Randomized Rounding: A Technique for Provably Good Algorithms and Algorithmic Proofs.” Combinatorica 7, no. 4 (1987): 365–374. [CrossRef]

- Raichle M.E. “Appraising the Brain’s Energy Budget.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 99, no. 16 (2002): 10237–10239. [CrossRef]

- Razborov A.A., and Rudich S. “Natural Proofs.” Journal of Computer and System Sciences 55, no. 1 (1997): 24–35. [CrossRef]

- Rice, H. G. “Classes of Recursively Enumerable Sets and Their Decision Problems.” Transactions of the American Mathematical Society 74, no. 2 (1953): 358–366. [CrossRef]

- Romera-Paredes B., Barekatain M., Novikov A., et al. “Mathematical Discoveries from Program Search with Large Language Models.” Nature 625 (2024): 468–475. [CrossRef]

- Roughgarden T. Beyond the Worst-Case Analysis of Algorithms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

- Schkufza E., Sharma R., and Aiken A. “Stochastic Superoptimization.” In PLDI ’13: Proceedings of the 34th ACM SIGPLAN Conference on Programming Language Design and Implementation, 305–316. New York: ACM, 2013.

- Shannon C.E. “The Synthesis of Two-Terminal Switching Circuits.” Bell System Technical Journal 28, no. 1 (1949): 59–98. [CrossRef]

- Silver D., Huang A., Maddison C.J., et al. “Mastering the Game of Go with Deep Neural Networks and Tree Search.” Nature 529, no. 7587 (2016): 484–489. [CrossRef]

- Silver D., Schrittwieser J., Simonyan K., et al. “Mastering the Game of Go without Human Knowledge.” Nature 550, no. 7676 (2017): 354–359. [CrossRef]

- Sipser M. Introduction to the Theory of Computation. 3rd ed. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning, 2013.

- Spielman D.A., and Teng S.H. “Smoothed Analysis of Algorithms: Why the Simplex Algorithm Usually Takes Polynomial Time.” Journal of the ACM 51, no. 3 (2004): 385–463. [CrossRef]

- Sweller J. “Cognitive Load During Problem Solving: Effects on Learning.” Cognitive Science 12, no. 2 (1988): 257–285. [CrossRef]

- Vazirani V.V. Approximation Algorithms. Berlin: Springer, 2001.

- Wetzler N., Heule M.J.H, and Hunt W.A. Jr. “DRAT-trim: Efficient Checking and Trimming Using Expressive Clausal Proofs.” In SAT 2014, 422–429. Cham: Springer, 2014.

- Wiles A. “Modular Elliptic Curves and Fermat’s Last Theorem.” Annals of Mathematics 141, no. 3 (1995): 443–551. [CrossRef]

- Williams R. "Nonuniform ACC Circuit Lower Bounds." Journal of the ACM 61, no. 1 (2014): 2:1–2:32. [CrossRef]

- Williamson D.P., and Shmoys D.B. The Design of Approximation Algorithms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Willsey M., Wang Y.R., Flatt O., et al. “egg: Fast and Extensible Equality Saturation.” Proceedings of the ACM on Programming Languages 5 (POPL) (2021): 1–29. [CrossRef]

- Xu L., Hutter F., Hoos H.H., and Leyton-Brown K. “SATzilla: Portfolio-based Algorithm Selection for SAT.” Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 32 (2008): 565–606. [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman D. “Linear Degree Extractors and the Inapproximability of Max Clique and Chromatic Number.” Theory of Computing 3, no. 1 (2007): 103–128. [CrossRef]

| 1 |

A list of abbreviations is at the end of the paper |

| 2 |

We use the term certificate broadly to mean any machine-checkable evidence that supports an algorithmic claim (e.g., a satisfying assignment as a witness, a DRAT/FRAT proof log for UNSAT, or an LP/SDP dual bound for optimization). |

| 3 |

Formally, implies ; for common NP problems (SAT, TSP decision to TSP optimization, etc.) the reconstruction uses well-known self-reduction schemes. |

| 4 |

Karp and Lipton, “Turing Machines That Take Advice,” L’Enseignement Mathématique, 1982 [ 50]. |

| 5 |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).