Submitted:

23 September 2025

Posted:

24 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- They require manual feature engineering.

- They are highly subjective.

- They do not generalize well in other scenarios.

- They require a high level of expertise.

- They are time-consuming during the data preprocessing with more than 50% of the whole data processing process.

- They are influenced by human factors.

2. Review of Related Work and Basic Methods

2.1. Definitions

- Univariate time series: only one descriptive variable/feature has been measured and observed over time.

- Multivariate time series: several descriptive variables/features have been measured and observed over time.

2.2. Imaging Time-Series Techniques

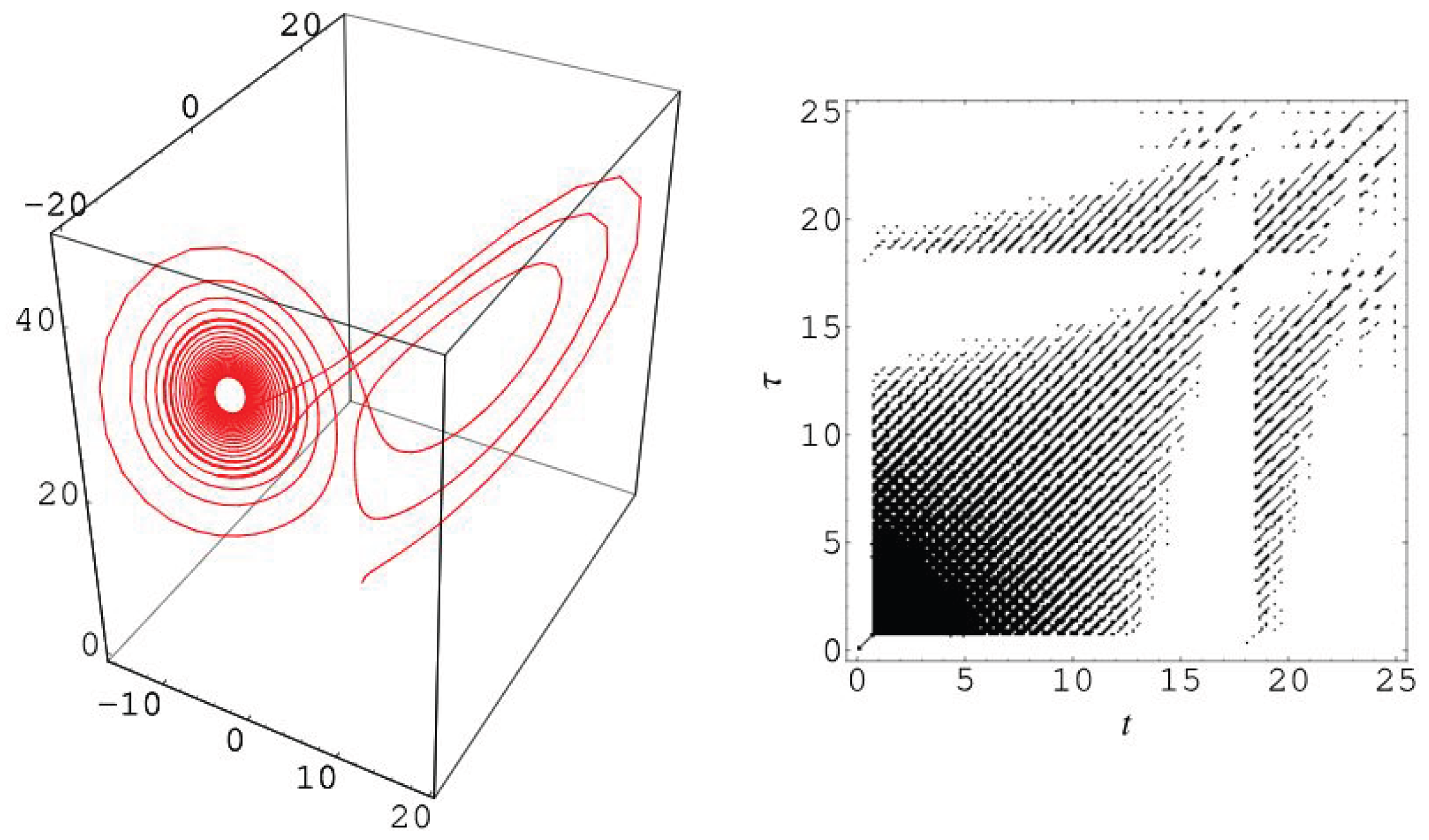

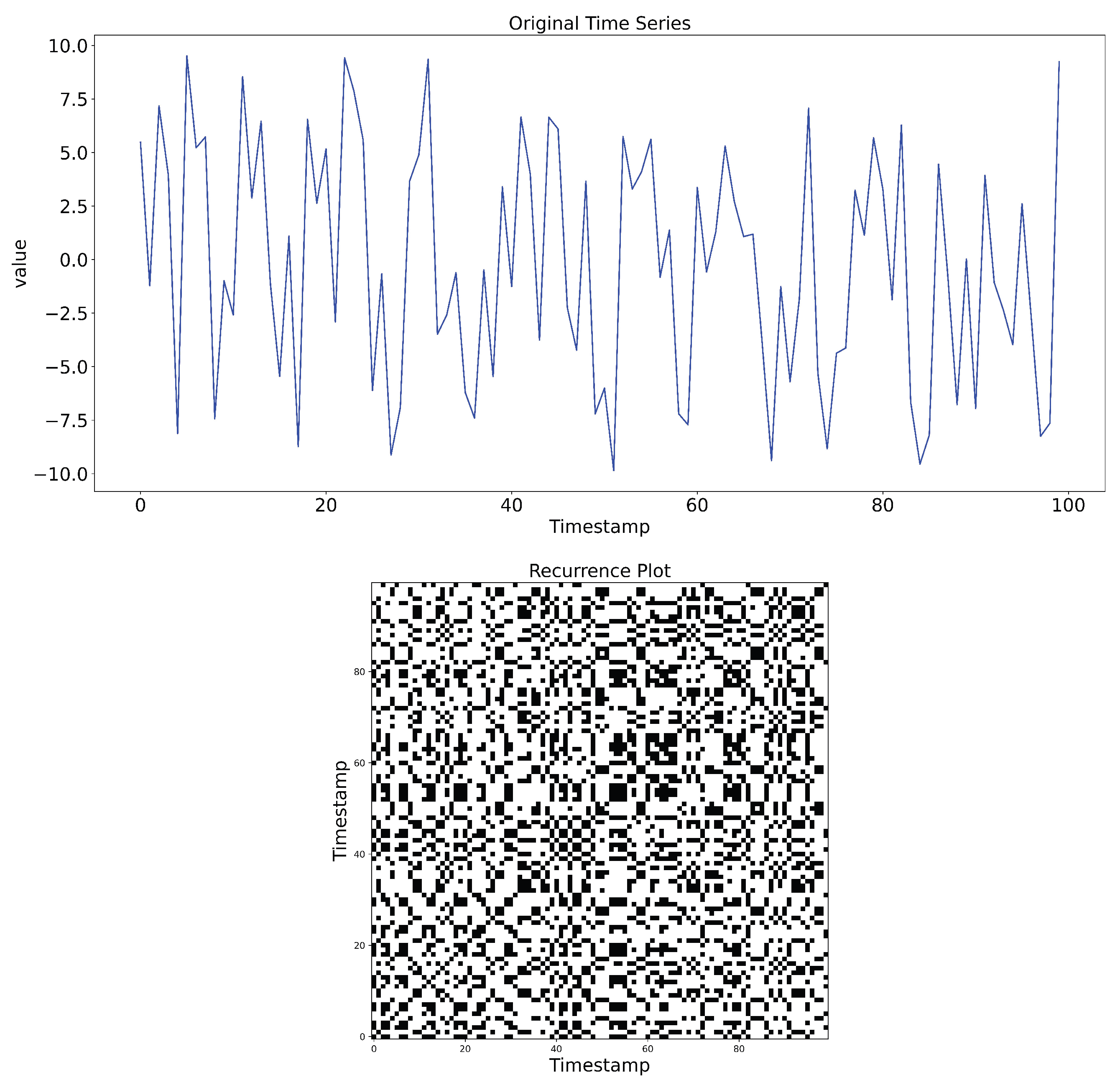

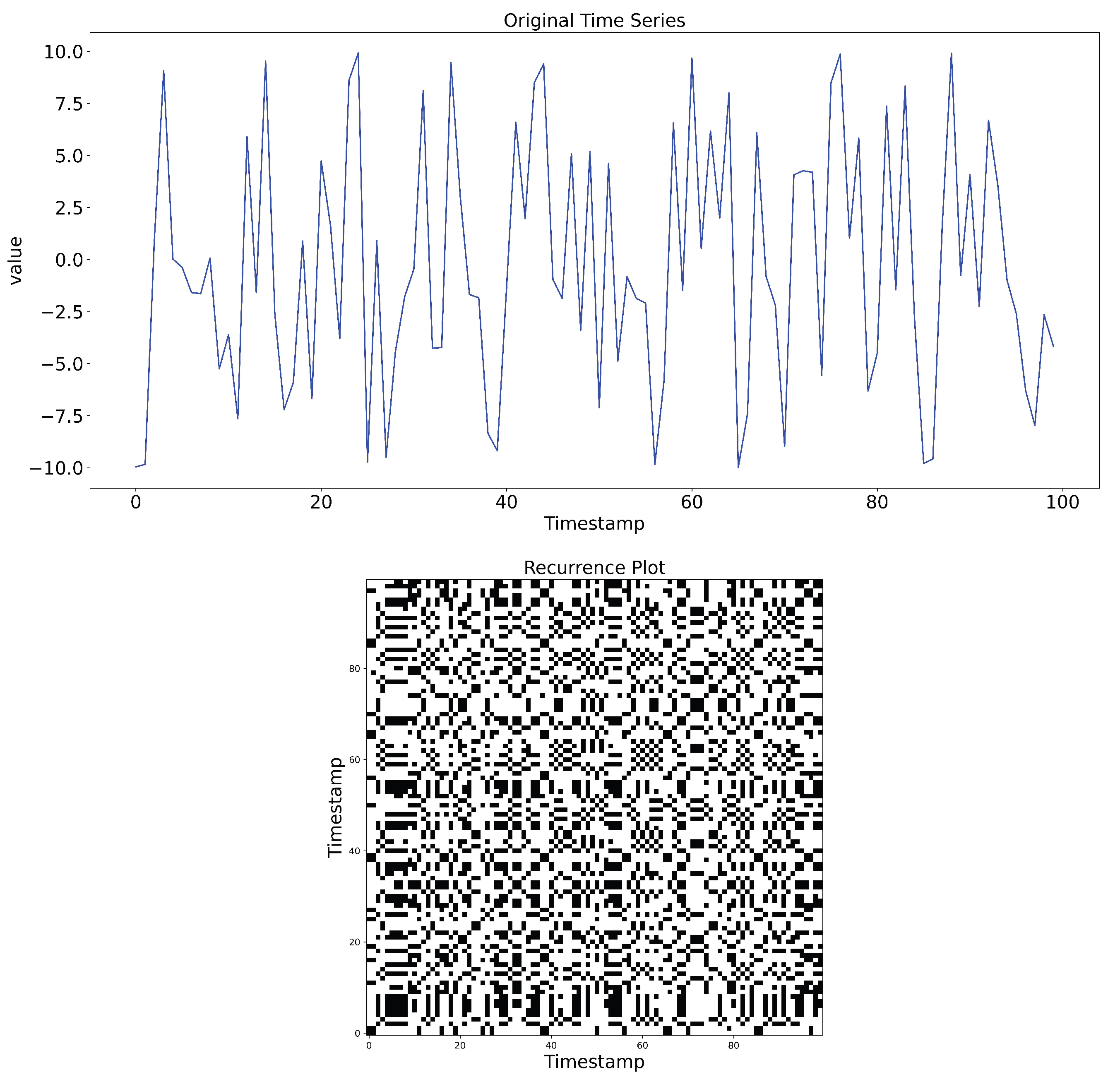

2.2.1. Recurrence Plot (RP)

- Ones (recurrent state: and

- Zeros (transient state: .

- m is the dimensions of the considered phase space.

- n is the length of the trajectory through the phase space/number of the future states resulting from a given initial state in phase space.

- : Considered time delay.

- is the binarized pairwise distance matrix of the trajectory of the recurrence of a state () between the initial time point i and the time point j over time in the m-dimensional phase space.

- is the Heaviside function.

- is the recurrence threshold.

- is the norm operator (normally the Euclidean norm is used).

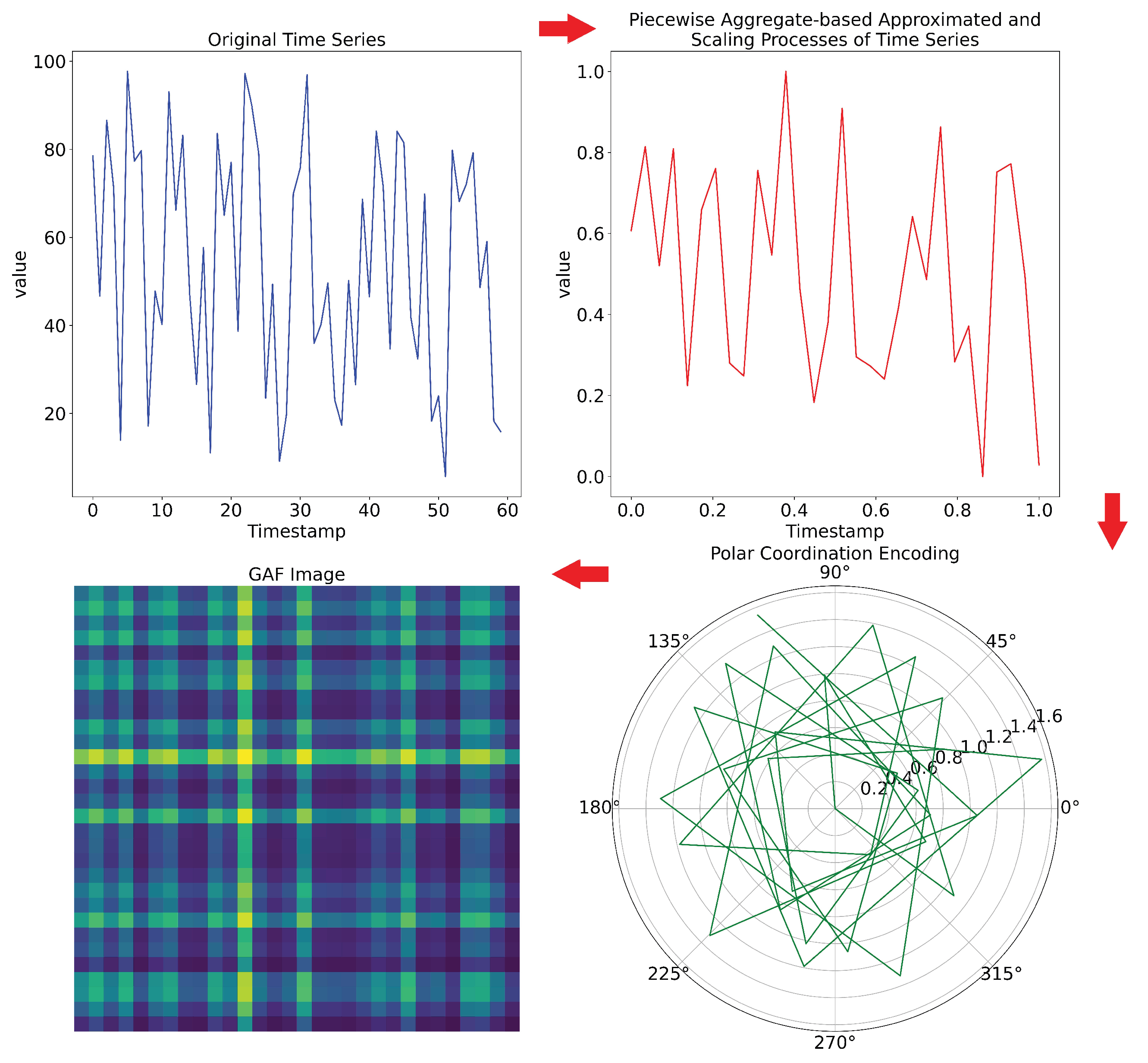

2.2.2. Gramian Angular Field (GAF)

- , these two vectors are similar.

- , these two vectors are orthogonal.

- , these two vectors are opposite.

- A Min-Max Scaling process is applied to transfer the time series onto the range;

- A Polar Encoding of each sample () within the scaled time series is calculated by:whre is the time stamp.

-

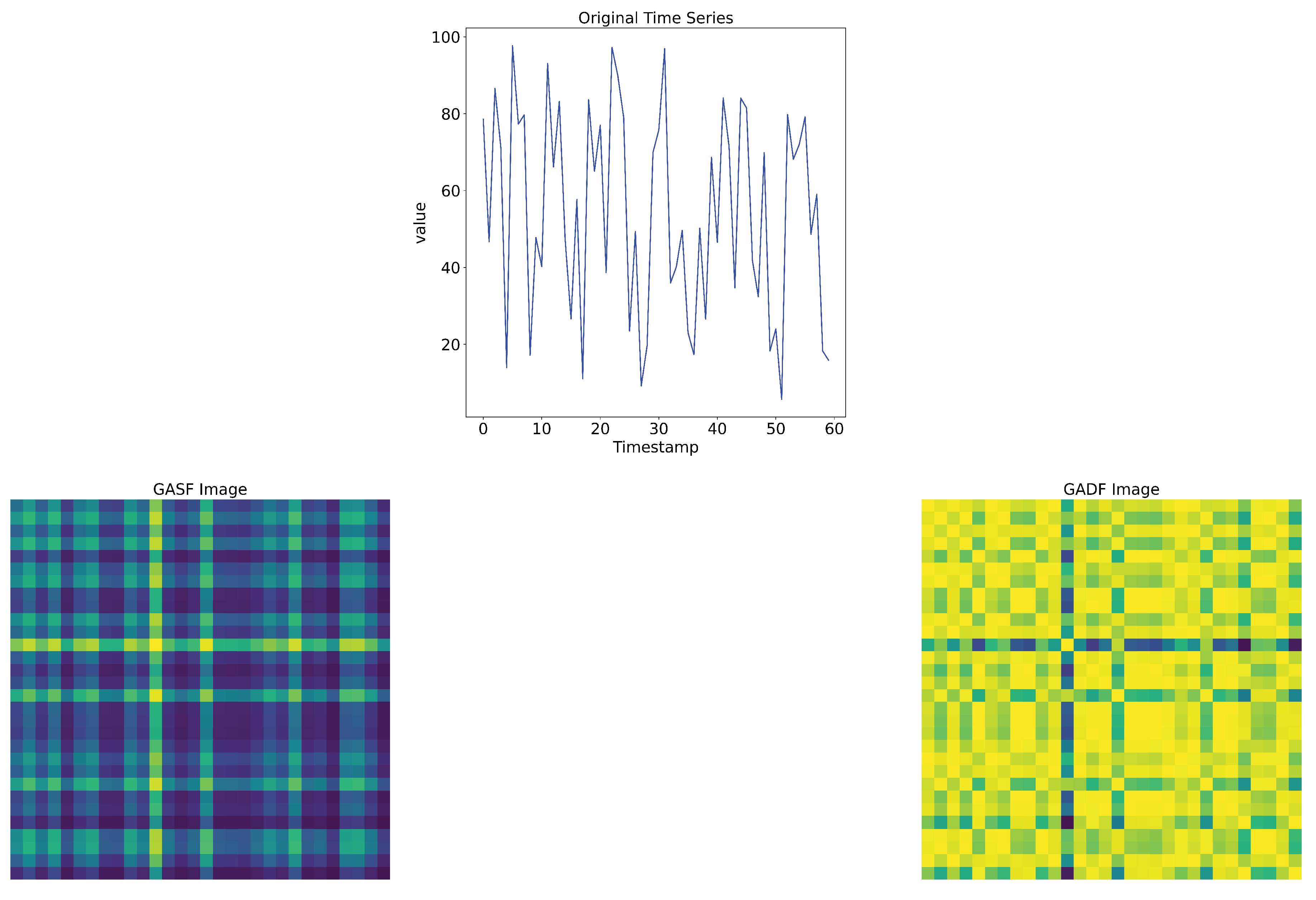

The Gramian matrix can be defined by two types of fields that encode the time series signals into images:

- Gramian Angular Summation Field (GASF) matrix:

- Gramian Angular Difference Field (GADF) matrix:

- Generation of the related GAF Image.

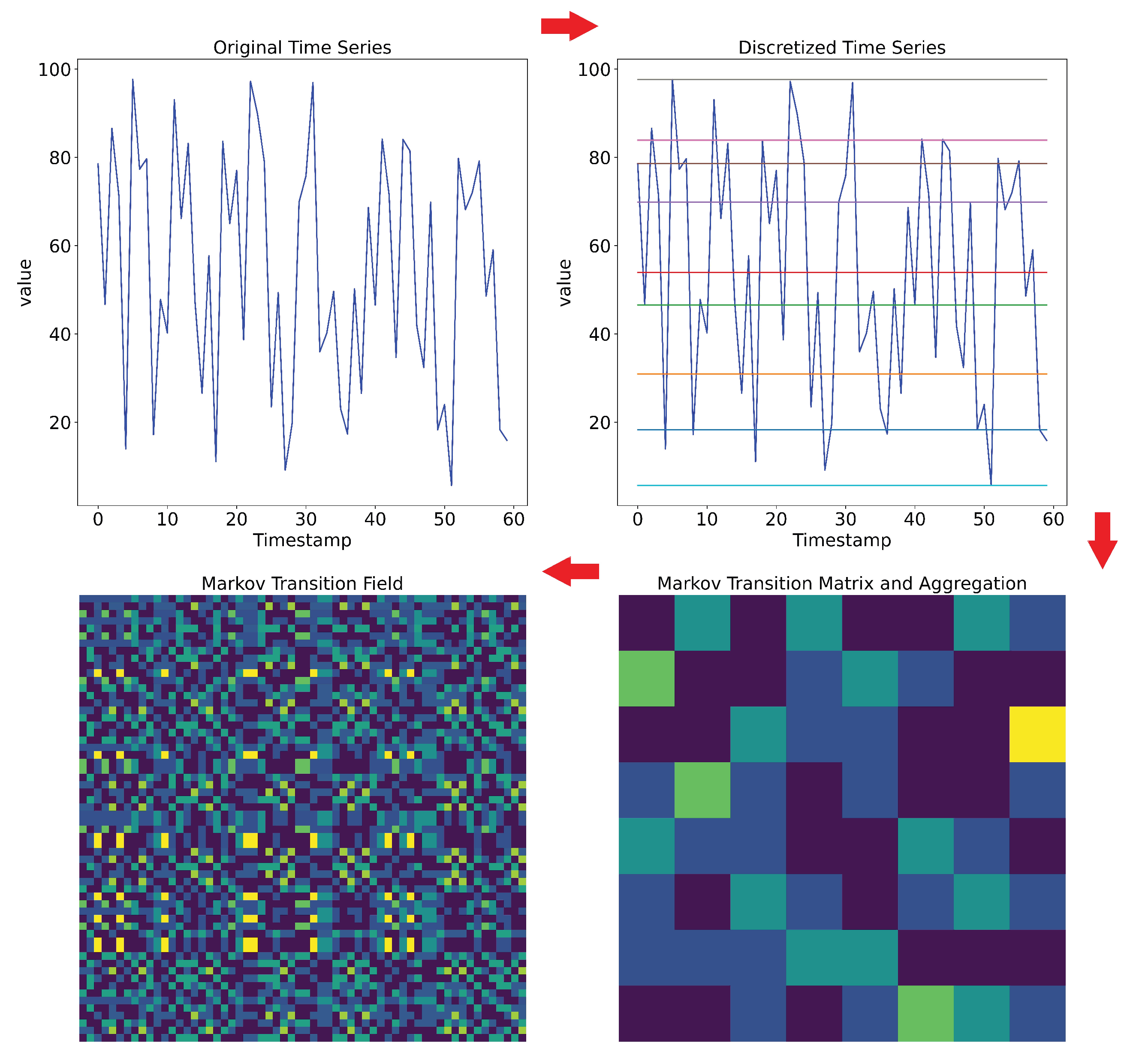

2.2.3. Markov Transition Field (MTF)

- is the probability of the transition of the () form (i) state to (j) state during one time step/unit of motion in the state space.

- Q is the number of states in/size of the state space of the considered dynamical system.

- Discretize the time series to Q quantile bins (e.g., A, B, C and D as in Figure 7).

- Build the Markov transition matrix.

- Compute transition probabilities.

- Compute the Markov transition field.

- Compute an aggregated MTF.

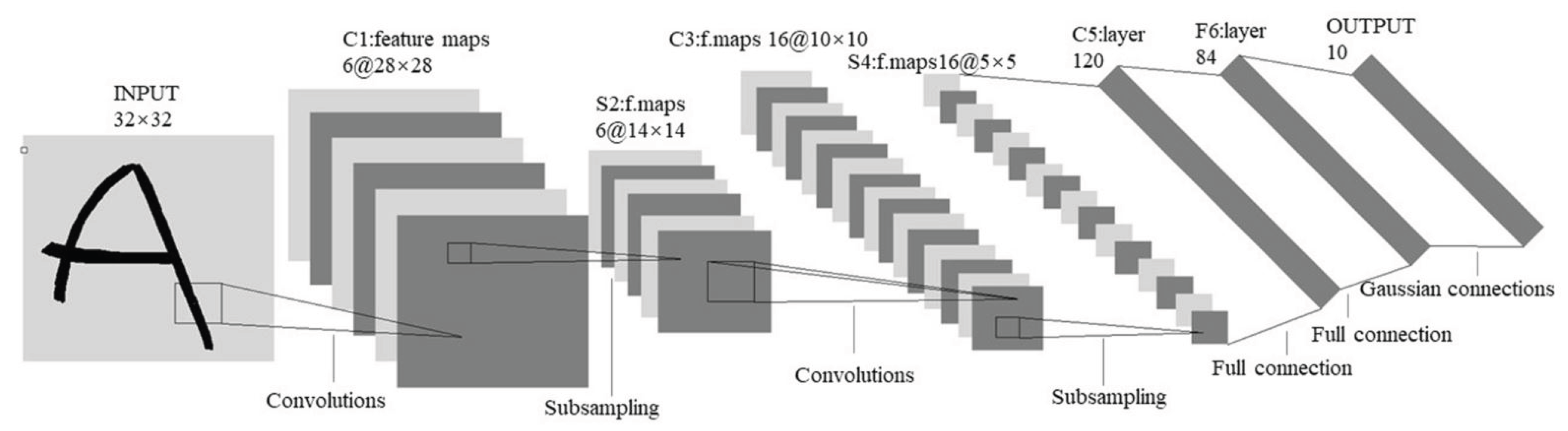

2.3. Convolutional Neural Networks as Deep Learning Systems Applied to Imaging Time-Series Datasets

2.3.1. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN)

-

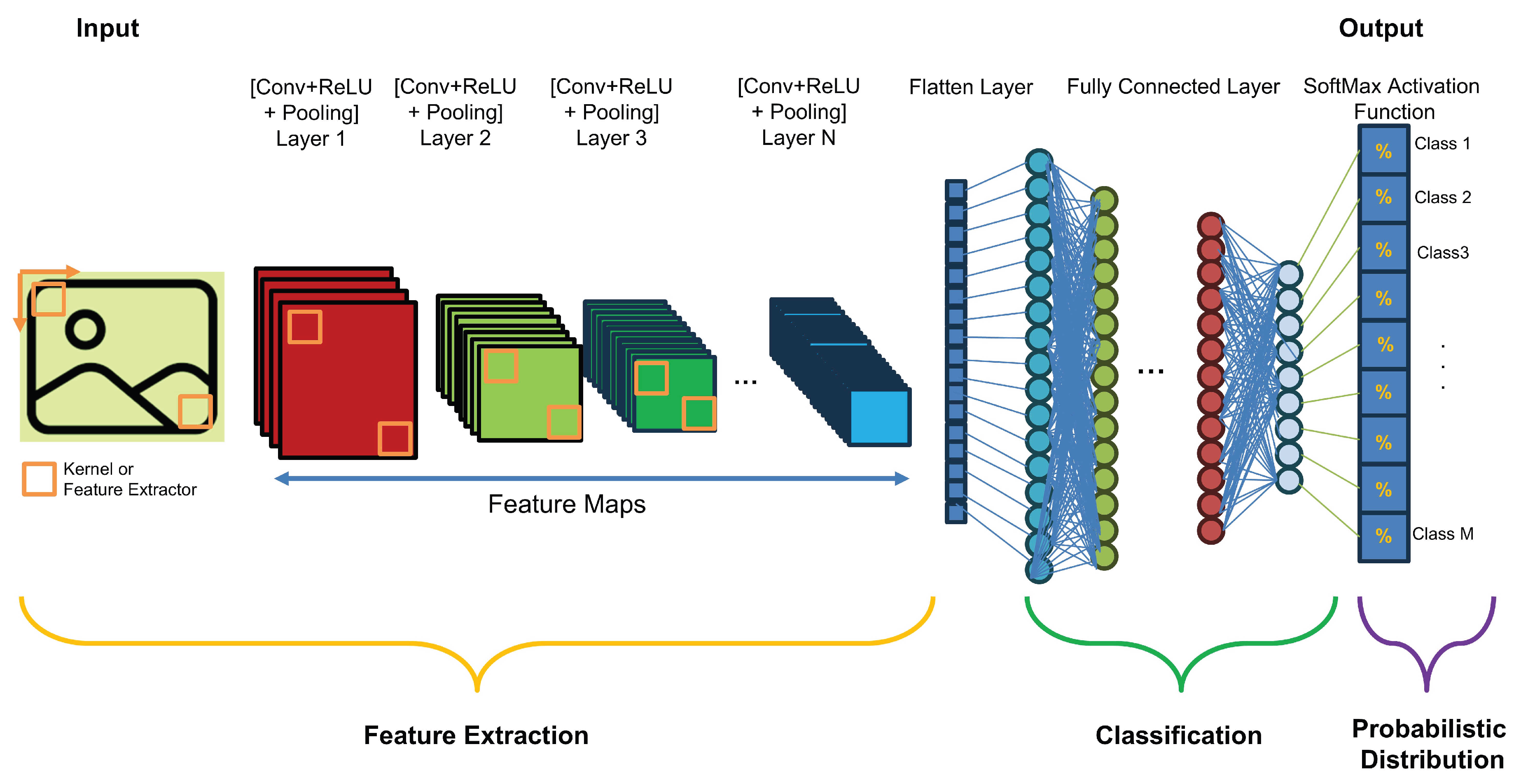

Feature Extraction:

- Convolution Layer: Basically, a convolution is defined as a mathematical operation in which two sets of information are merged to create a new set that contains more informative information about the task at hand. In this sense, the first information set is considered as an image represented by a 2D matrix with one or three channels. The second information set is a convolution filter, usually a square matrix with dimensions of 2, 3, etc., that extracts specific features. These features can be low-level (such as contours, edges, angles, and colors) or high-level (such as shapes and objects). The extracted features are collected together to create a 2D "feature map." The convolution process can also be applied to the feature map generated from the previous layer to create a new feature map with more complex and intricate features than the original.

- Nonlinear Activation Layer: It consists of nonlinear functions, such as the rectified linear unit (ReLU) and sigmoid functions. The correlation between the convolution process and the nonlinearity process can perform the following tasks: 1) enable the network/model to learn/build complex representations and relationships with a "nonlinearity property" of the input/output data/information and 2) prevent the exponential growth of the computations required to run the neural network.

- Pooling Layer: In this step, the size of the feature map generated by the (Convolution + ReLU) layer is subsampled by aggregating features from local regions to learn invariant features and reduce computational complexity. In this process, the m-square matrix (usually or ) is shifted over the processed feature map using a predefined step called stride. For each shift, a value (e.g., average, maximum, or minimum) is computed and substituted in place of the originally processed values in the new feature map.

The sequence of layers (convolutional layer, nonlinear activation function, and pooling), called hidden layers, can be stacked several times, and their final output yields the feature map. The deeper the feature extraction block of the CNN, the more complex the feature map, i.e., the feature map starts with low-level features and then becomes more complex as it passes through each hidden layer until it reaches high-level features at the end of the feature extraction block. - Flattening Layer: Since the final output of the last (Convolution + ReLU + Pooling) sequence as the last layer in the feature extraction stage has the format of a 2D matrix and also the input of the classification stage in the CNN model has the format of a 1D matrix, the process "Flatten" should be applied.

- Classification: The extracted and flattened features maps of the considered states will be processed by the Fully Connected (FC) network, which consists of the several feedforward layers

- Probabilistic Distribution: To bring probabilistic distribution of the considered classes, a SoftMax Activation function is usually applied.

2.3.2. CNN Classification Systems Based on Time Series-to-Image Encoding

-

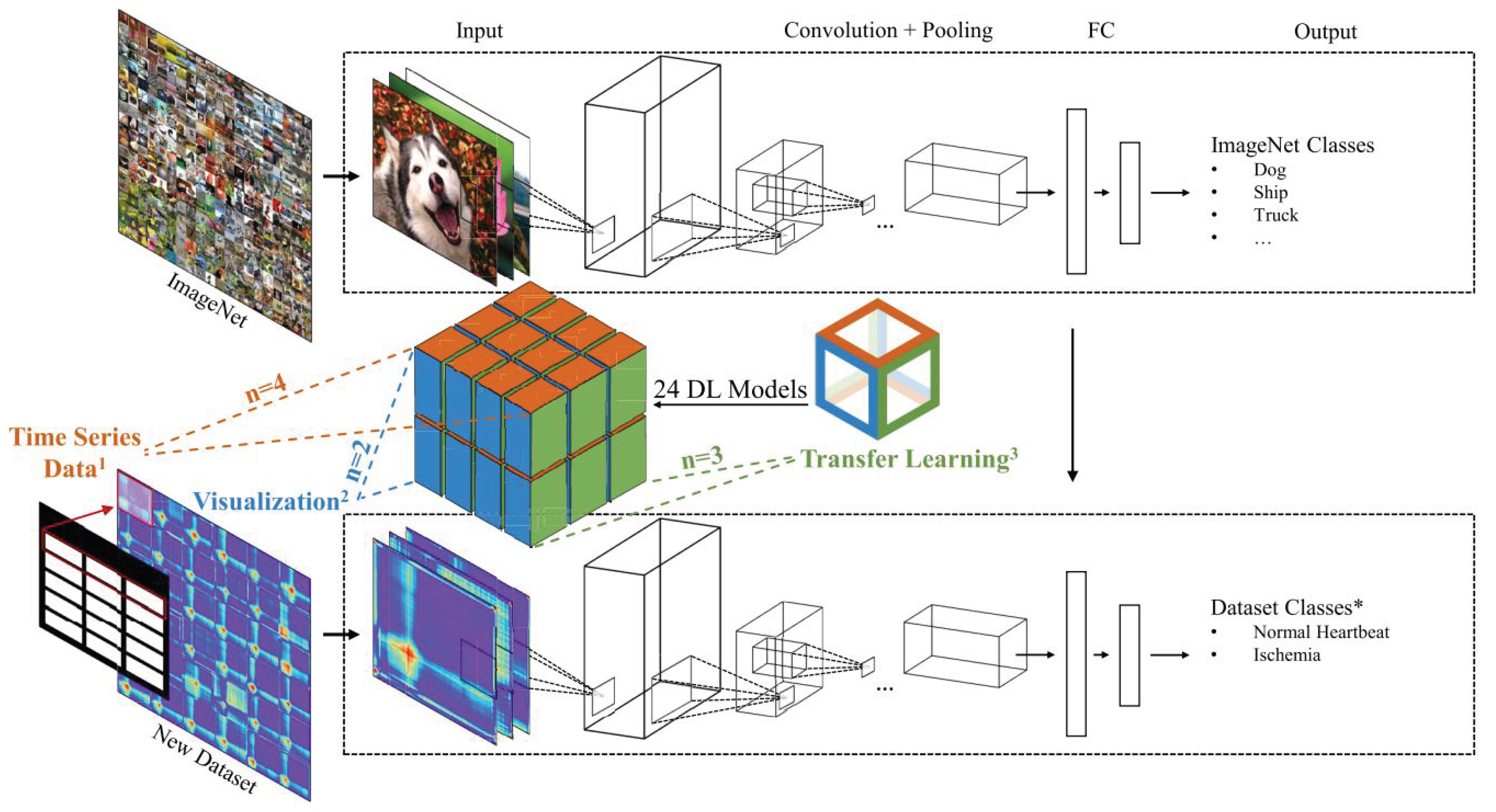

Gross et al. [1] suggested the following concepts for building the classification system of the time series as illustrated in Figure 10 [1]:

- GAF, GASF, and GADF as time-series imaging techniques, which will be separately used to image the considered time-series dataset and

- Benchmarking transfer learning strategies, which aims to improve the learning of new task through the transfer of knowledge from a related task that has already been learned (such as VGG16, VGG19, ResNet50V2 and Xception).

To evaluate the transfer learning strategies for benchmarking time-series imaging, the following datasets were used, whose numerical specifications are listed in Table 1 [35]:- (a)

- Computers: These problems were taken from data recorded as part of government sponsored study called Powering the Nation. The intention was to collect behavioral data about how consumers use electricity within the home to help reduce the UK’s carbon footprint. The data contains readings from 251 households, sampled in two-minute intervals over a month. Each series is length 720 (24 hours of readings taken every 2 minutes). Classes are Desktop and Laptop.

- (b)

- DodgerLoopGame: The traffic data are collected with the loop sensor installed on ramp for the 101 North freeways in Los Angeles. This location is close to Dodgers Stadium; therefore the traffic is affected by volume of visitors to the stadium.- Class 1: Normal Day - Class 2: Game Day.

- (c)

- ECG200: Each series traces the electrical activity recorded during one heartbeat. The two classes are a normal heartbeat and a Myocardial Infarction.

- (d)

- AbnormalHeartbeat: Heartbeat recordings were gathered from both the iStethoscope Pro iPhone app and from clinical trials using digital stethoscope DigiScope. The time series represent the change in amplitude over time during an examination of patients suffering from any four common arrhythmias.

-

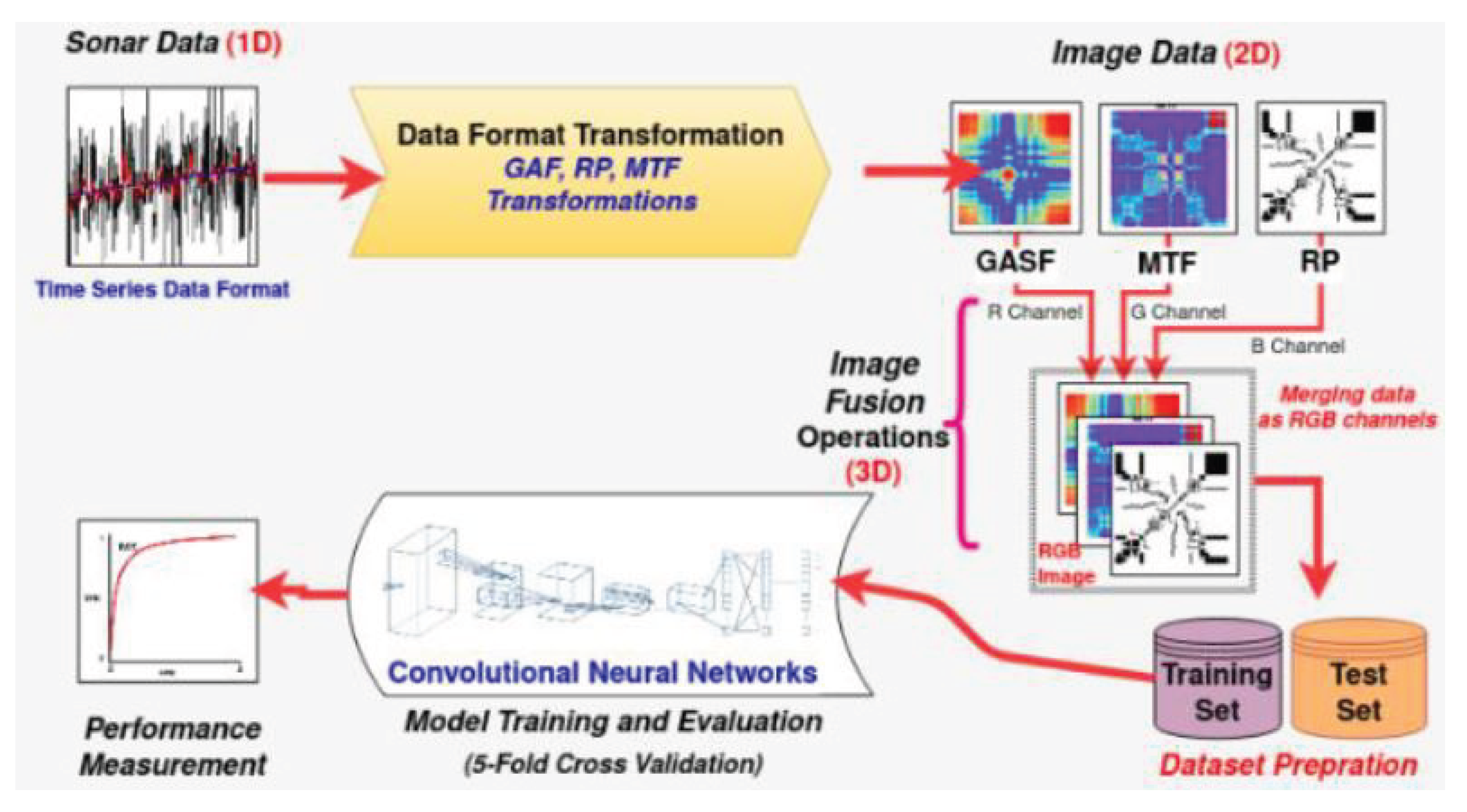

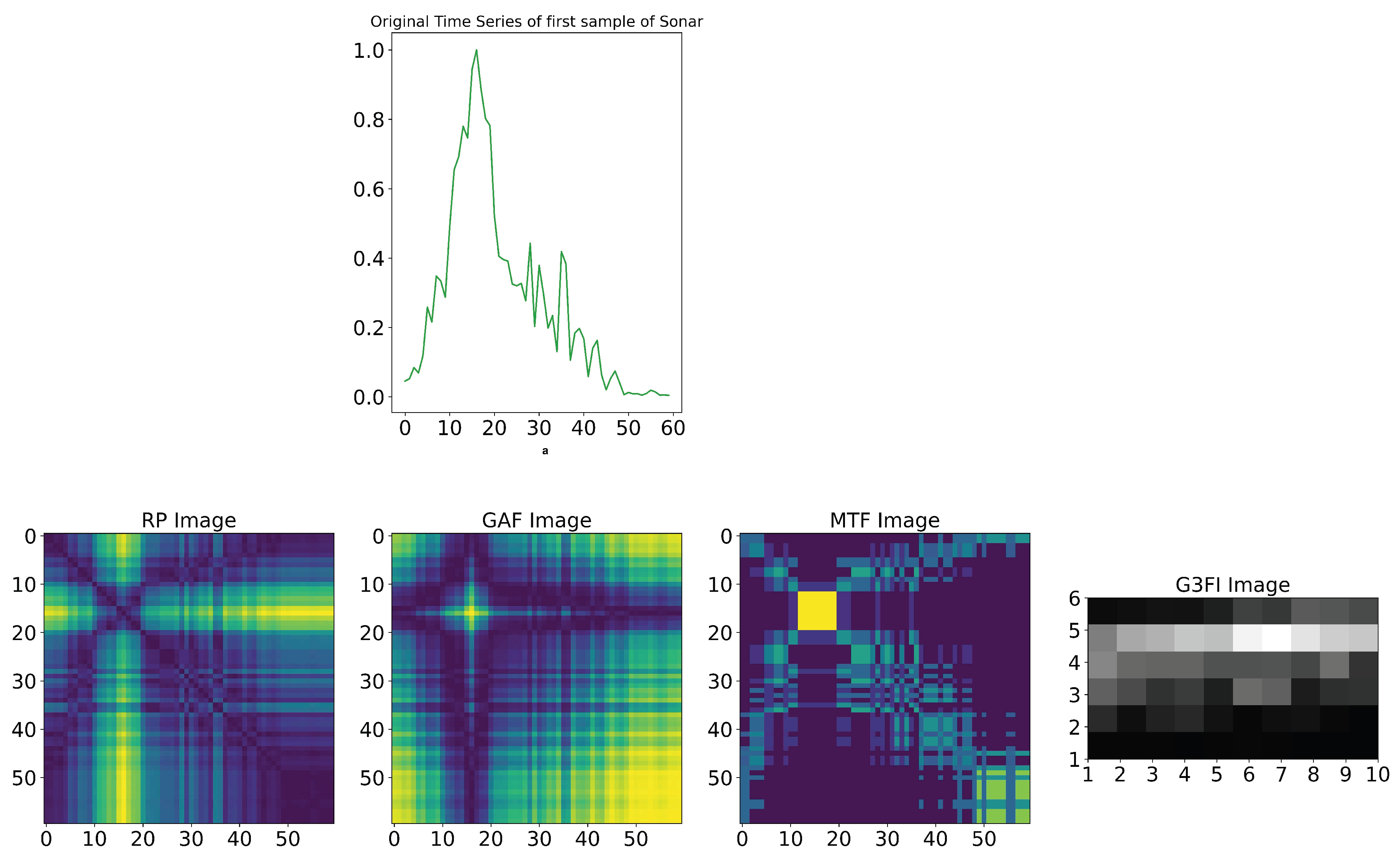

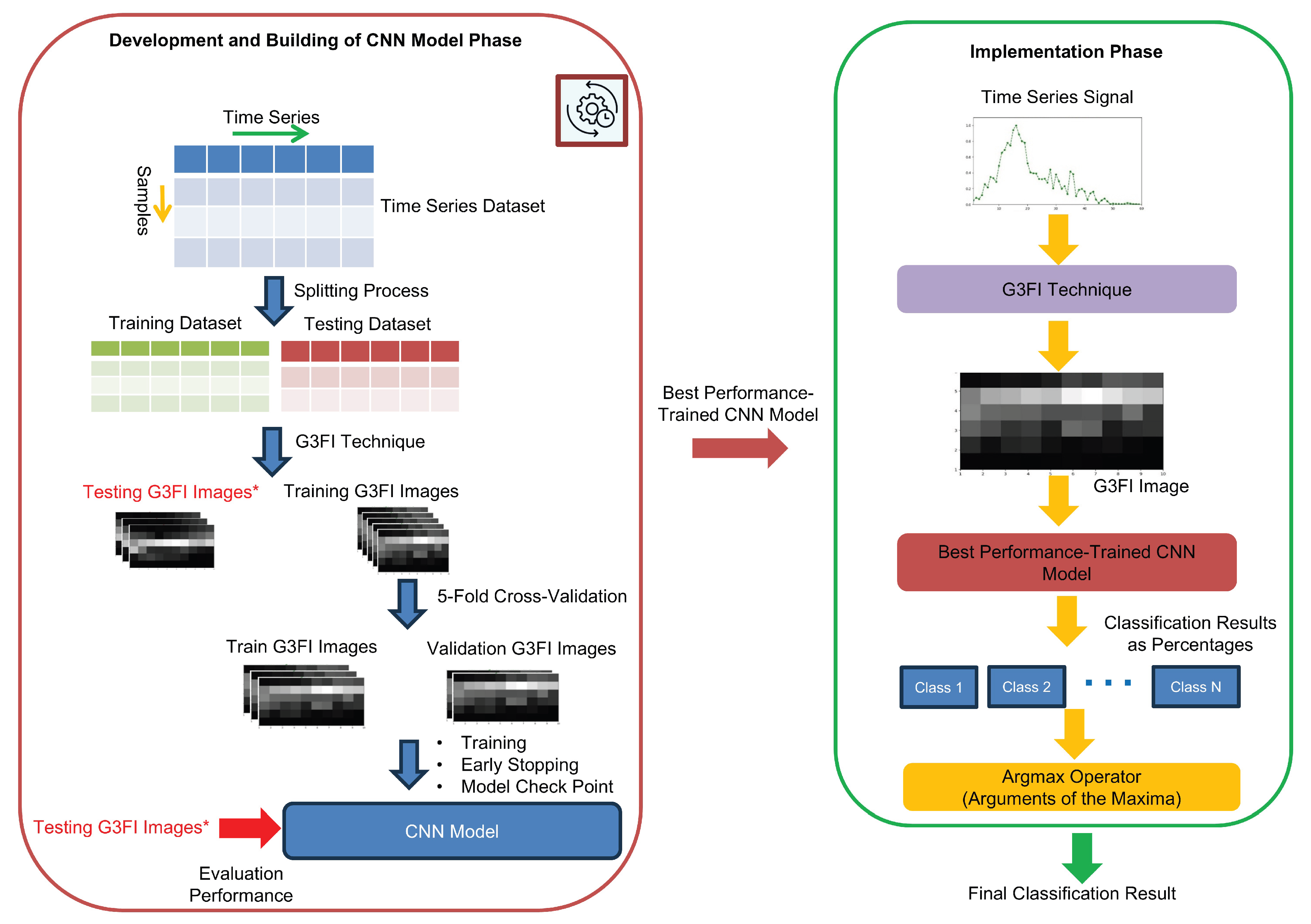

Buz et al. [21] developed another approach and application of time series-to-image transformation methods for classifying underwater objects (sonar signals), as shown in Figure 11. The sonar dataset developed by Gorman et al. [36] was used to evaluate the Buz et al.’s method. This dataset contains the signals reflected from cylindrical mines and cylindrical rocks resembling these mines from different angles. The size of the dataset is 208 samples in the format of the time series, where 111 samples belong to cylindrical mines and 97 samples to cylindrical rocks. The length of each time series is 60 numbers, ranging from 0.0 to 1.0. Each number represents the energy collected over a fixed period in a given frequency band [36].The core of the comparative analysis is the conversion of the sonar time-series dataset into the related and individual 2D image dataset by means of the separate application of the GASF, MTF, and RP techniques. Then, the three related 2D image datasets are merged to generate the 3D image for each sample in the sonar dataset, as shown in Figure 14. The resulting 3D image dataset is used to train and evaluate the CNN architecture shown in Figure 12.

3. Novel Approach of Time Series-to-Image Encoding for Convolutional Neural Networks-based Classification

3.1. Grayscale Fingerprint Features Field Imaging Techniques

3.1.1. Motivation

- The transformation processes are characterized by a high degree of complexity.

- The resulting image structure exhibits diagonal symmetry, resulting in the presence of redundant and duplicated information.

- The resolution of the image is directly proportional to the square of the number of descriptive features of the time-series data under consideration. Consequently, as the number of features increases, the image resolution improves. However, this enhancement in resolution necessitates a proportional increase in the time required to process the image, thereby achieving the desired objectives, such as classification.

- Only two simple steps-based transformation process is applied to transfer the descriptive features/variables of each sample of the time series into the 2D image.

- The resulting image has a non-symmetric property and its resolution is equal to the number of descriptive features/variables of the transformed sample.

3.1.2. Methodology

- is the descriptive feature.

- l is the number of the used descriptive features/number of the columns of the multivariate time-series dataset.

-

Grayscale-based normalizing process of descriptive features of each considered sample by:leading to new feature values between zero (black) and 255 (white), with:

- is the normalized/scaled vector of the descriptive features of each considered sample.

- is the minimum value of the descriptive features of each considered sample.

- is the maximum value of the descriptive features of each considered sample.

- 255 is the scalar of grayscale processing.

-

Generation process of G3FI image () by reshaping (Reshape) the grayscale normalized vector of each considered sample into the () matrix as follows:where

- is the reshaping process of the grayscale normalized/scaled vector into () matrix to generate G3FI Image.

- K is the number of rows in the G3FI image matrix().

- L is the number of columns in the G3FI image matrix ().

3.2. Comparison of Images of State-of-Art and Novel G3FI Techniques

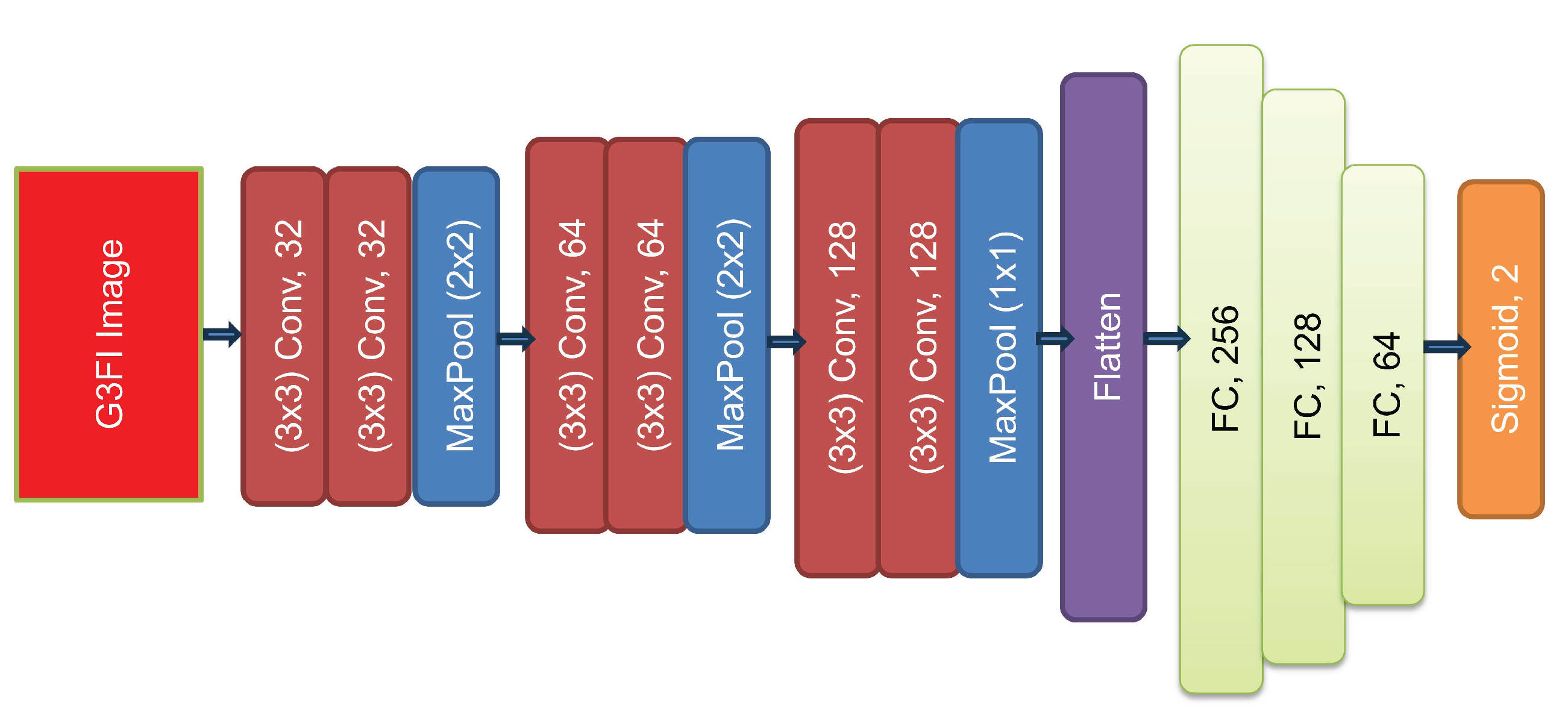

3.3. CNN Classification System Based on G3FI-Image-Encoded Time-Series

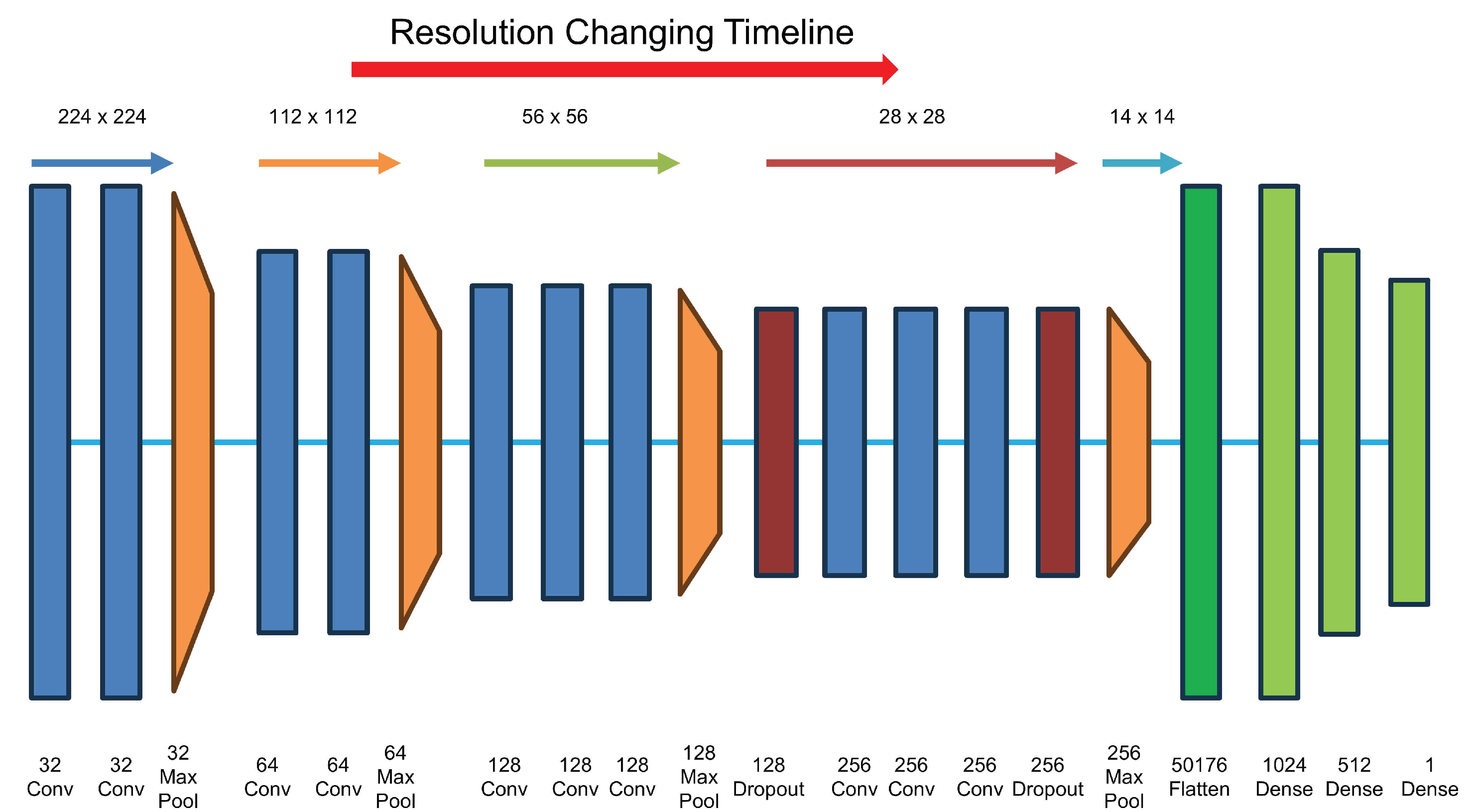

- The ReLU is incorporated as the activation function in all applied layers.

- The batch normalization (BN) technique is implemented prior to the ReLU activation function of the convolutional layers. This implementation is intended to avoid the phenomenon of vanishing gradients and to speed up the training of the model.

- The Same is employed for the padding.

- The optimizer is Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) with a learning rate of 0.01 and a momentum of 0.9.

- The loss function is Binary Cross Entropy.

- For Early Stopping, the monitoring criterion is the minimum value of the validation loss function.

- For Model Checkpoint, the maximum value of the validation accuracy is employed as monitoring criterion.

4. Results and Discussion

- Comparative results for the Computer and DodgerLoopGame datasets.

- Superior results for the ECG200 and AbnormalHeartbeat datasets.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gross, J.; Baumgartl, R.; Hermann, B. Benchmarking Transfer Learning Strategies in Time-Series Imaging: Recommendations for Analyzing Raw Sensor Data. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 16977–16991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferencz, K.; Domokos, J.; Kovács, L. Analysis of time series data for anomaly detection. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 22nd International Symposium on Computational Intelligence and Informatics and 8th IEEE International Conference on Recent Achievements in Mechatronics, Automation, Budapest, Hungary, November 21–22 2022., Computer Science and Robotics (CINTI-MACRo). [CrossRef]

- Jantawong, P.; Hnoohom, N.; Jitpattanakul, A.; Mekruksavanich, S. Time Series Classification Using Deep Learning for HAR Based on Smart Wearable Sensors. In Proceedings of the 26th International Computer Science and Engineering Conference (ICSEC), Sakon Nakhon, Thailand, December 21–23 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, T. A review on time series data mining. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2011, 24, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottou, L. From machine learning to machine reasoning. Machine Learning 2011, 94, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artemios-Anargyros, S.; Evangelos, S.; Vassilios, A. Image-based time series forecasting: A deep convolutional neural network approach. Neural Networks 2023, 157, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, I.H. AI-Based Modeling: Techniques, Applications and Research Issues Towards Automation, Intelligent and Smart Systems. SN Computer Science 2022, 3, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Li, J.; Luo, Z.; Chapman, M. Spectral-spatial residual networks for hyperspectral image classification: a 3-D deep learning framework. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2018, 56, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silberzahn, R.; Uhlmann, E.L.; Martin, D.P.; Anselmi, P.; Aust, F.; Awtrey, E.; Bahník, S.; Bai, F.; Bannard, C.; Bonnier, E.; et al. Many analysts, one data set: Making transparent how variations in analytic choices affect results. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science 2018, 1, 337–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, T.; Khemchandani, V. Feature engineering (FE) tools and techniques for better classification performance. International Journal of Innovations in Engineering and Technology (IJIET) 2017, 8, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.; Marques, M.R.G.; Botti, S.; Marques, M.A.L. Recent advances and applications of machine learning in solid-state materials science. NPJ Computational Materials 2019, 5, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, O.; Slavkovikj, V.; Vervisch, B.; Stockman, K.; Loccuer, M.; Verstockt, S.; Van de Walle, R.; Van Hoecke, S. Convolutional Neural Network Based Fault Detection for Rotating Machinery. Journal of Sound and Vibration 2016, 377, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz-Valckenberg, S.; Göbel, A.P.; Saur, S.; Steinberg, J.; Thiele, S.; Wojek, C.; Russmann, C.; Holz, F.G. Automated retinal image analysis for evaluation of focal hyperpigmentary changes in intermediate age-related macular degeneration. Translational Vision Science & Technology 2016, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Gallego, V.; Krawczyk, B.; García, S.; Woniak, M.; Herrera, F. A survey on data preprocessing for data stream mining: Current status and future directions. Neurocomputing 2017, 239, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawaz, H.I.; Forestier, G.; Weber, J.; Idoumghar, L.; Müller, P.A. Deep learning for time series classification: a review. Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery 2019, 33, 917–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 512, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Blincoe, K.; Kempa-Liehr, A.W. Enriching feature engineering for short text samples by language time series analysis. EPJ Data Science 2020, 9, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyl, S. A hybrid method of exponential smoothing and recurrent neural networks for time series forecasting. International Journal of Forecasting 2020, 36, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Oates, T. Encoding Time Series as Images for Visual Inspection and Classification Using Tiled Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Workshops at the 29th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Austin, Texas, USA, January 25–30 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hatami, N.; Gavet, Y.; Debayle, J. Classification of Time-Series Images Using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. 2017; arXiv:cs.CV/1710.00886]. [Google Scholar]

- Buz, A.C.; Demirezen, M.U.; Yavanoglu, U. Novel Approach and Application of Time Series to Image Transformation Methods on Classification of Underwater Objects. Gazi Journal of Engineering Sciences 2021, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barra, S.; Carta, S.M.; Corriga, A.; Podda, A.S.; Recupero, D.R. Deep learning and time series-to-image encoding for financial forecasting. IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica 2020, 7, 683–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiangala, K.; Wang, Z. An effective predictive maintenance framework for conveyor motors using dual time-series imaging and convolutional neural network in an industry 4.0 environment. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 121033–121049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PYTS. A Python Package for Time Series Classification. https://pyts.readthedocs.io/en/stable/user_guide.html. accessed on 31.10.2023.

- Mitiche, I.; Morison, G.; Nesbitt, A.; Hughes-Narborough, M.; Stewart, B.G.; Boreham, P. Imaging Time Series for the Classification of EMI Discharge Sources. Sensors 2018, 18, 3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckmann, J.P.; Kamphorst, S.O.; Ruelle, D. Recurrence Plots of Dynamical System. Europhysics Letters 1987, 4, 973–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Amaro, K.; Figueroa-Nazuno, J. Recurrence Plot Analysis and its Application to Teleconnection Patterns. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Computing, Mexico City, Mexico, November 21–24 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caraiani, P.; Haven, E. The Role of Recurrence Plots in Characterizing the Output-Unemployment Relationship: An Analysis. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e56767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MathWorld, W. Recurrence Plot. https://mathworld.wolfram.com/RecurrencePlot.html. accessed on 16.09.2025.

- Wang, Z.; Oates, T. Imaging Time-Series to Improve Classification and Imputation. 2015; arXiv:cs.LG/1506.00327]. [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima, K. Neocognitron: A self-organizing neural network model for a mechanism of pattern recognition unaffected by shift in position. Biological Cybernetics 1980, 36, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demertzis, K.; Demertzis, S.; Iliadis, L. A Selective Survey Review of Computational Intelligence Applications in the Primary Subdomains of Civil Engineering Specializations. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Géron, A. Hands-On Machine Learning with Scikit-Learn, Keras, and TensorFlow: Concepts, Tools, and Techniques to Build Intelligent Systems, 2nd ed.; O’Reilly Media: Canada, 2019; pp. 445–480. [Google Scholar]

- UCR Time Series Classification Archive. The UCR Time Series Classification Archive. https://www.cs.ucr.edu/~eamonn/time_series_data_2018/. accessed on 31.10.2023.

- Gorman, R.P.; Sejnowski, T.J. Analysis of hidden units in a layered network trained to classify sonar targets. Neural Networks 1988, 1, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Number of Samples | Length of Time Series | Classes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computers | 500 | 720 | 1: Desktop, 2: Laptop |

| DodgerLoopGame | 158 | 288 | 1: Normal Day, 2: Game Day |

| ECG200 | 200 | 96 | 1: Normal, 2: Ischemia |

| AbnormalHeartbeat | 606 | 3053 | 1: Normal, 2: Arrhythmias |

| Dataset | Total number of the parameters of trained G3FI-CNN model |

|---|---|

| AbnormalHeartbeat | 5,866,658 |

| Computers | 1,705,122 |

| DodgerLoopGame | 853,154 |

| ECG200 | 525,474 |

| Sonar | 394,402 |

| Name of Dataset | Gross et al. [1] | Buz et al. [21] | Our System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computers | 74.4% | – | 71.8% |

| DodgerLoopGame | 93.7% | – | 93.4% |

| AbnormalHeartbeat | 66.5% | – | 73.1% |

| ECG200 | 86.5% | – | 94.9% |

| Sonar | – | 97.6% | 98.5% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).