Submitted:

23 September 2025

Posted:

24 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

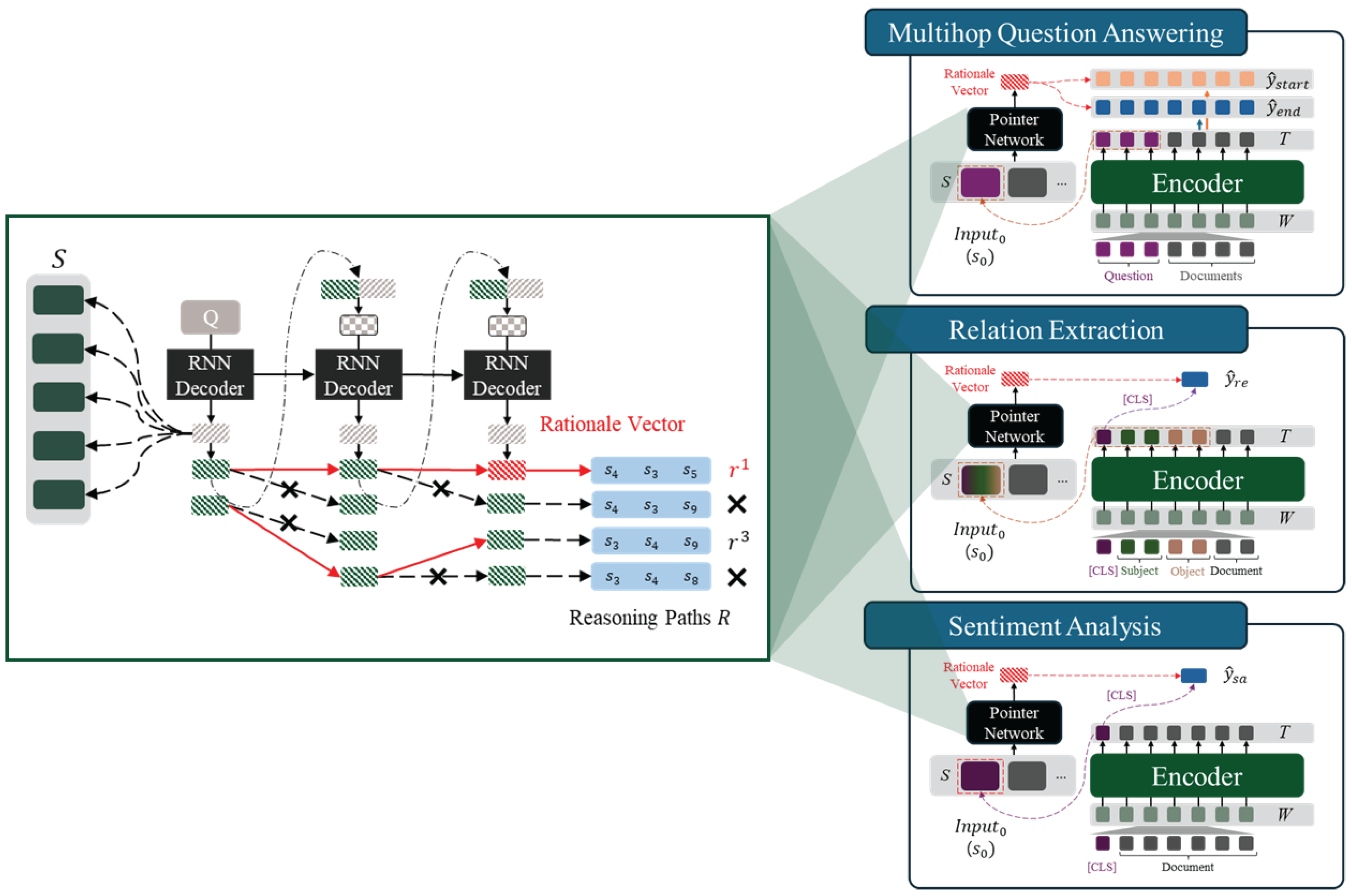

3. Methodology

4. Experiments

4.1. Dataset and Experimental Setup

4.2. Baseline

4.3. Metrics

- 0 points: The provided rationale does not substantiate or is irrelevant to the model’s prediction at all.

- 1 point: The provided rationale somewhat supports the model’s prediction but is not decisive; it is partially inferred but unclear.

- 2 points: The provided rationale fully substantiates the model’s prediction, and the same answer can be inferred solely based on the given rationale.

4.3.1. Prompt Details for GPT-Based Evaluation

- Task Description: A clear explanation of the evaluation task.

- Predicted Answer: The model’s predicted answer for the given question.

- Rationale Sentences: The evidence sentences inferred by the model, to be evaluated by GPT-4o mini.

4.4. Comparison Models

4.5. Experimental Results

4.5.1. Quantitative Evaluation

4.5.2. GPT Score Evaluation

4.5.3. Ablation Study

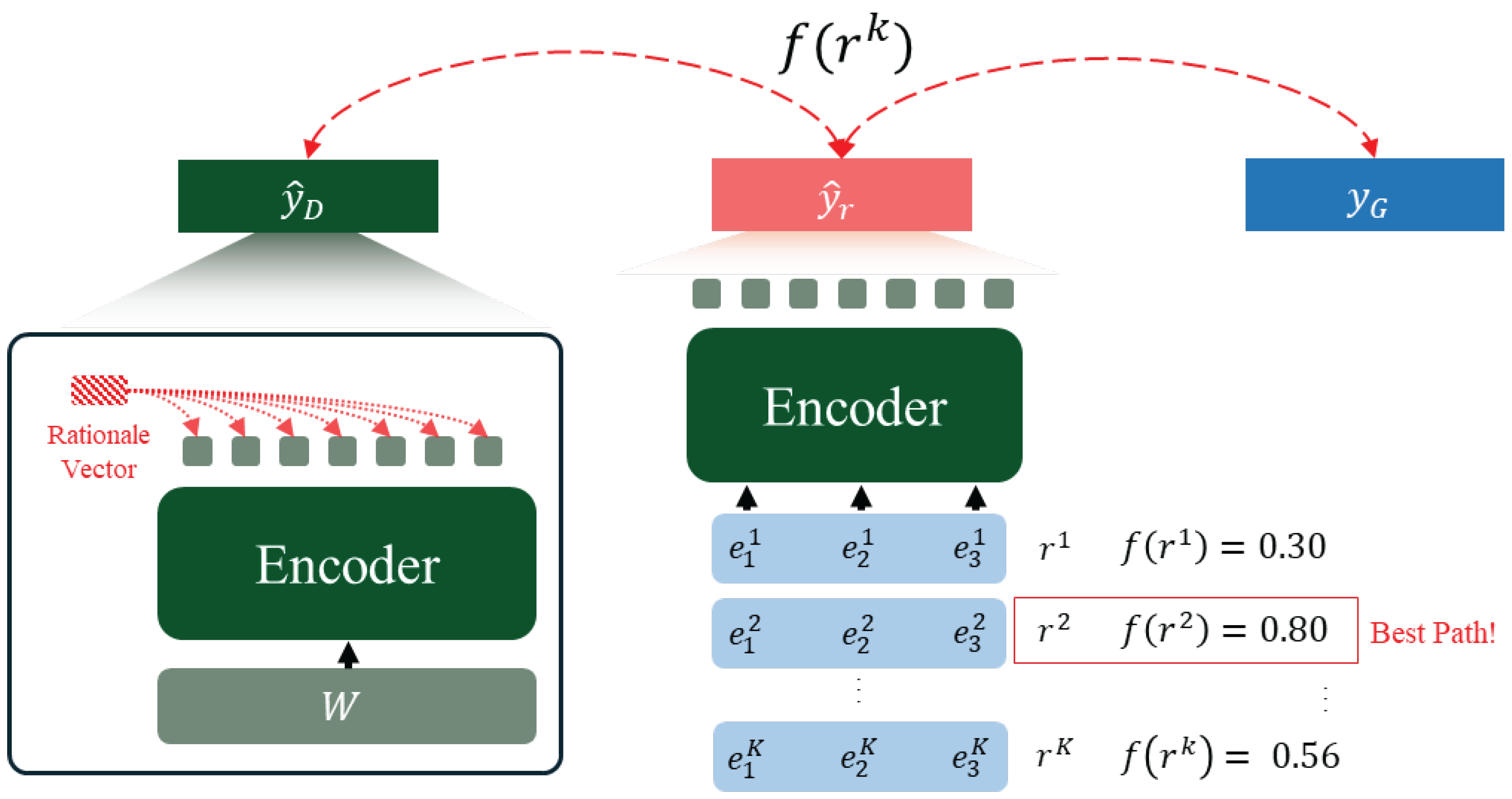

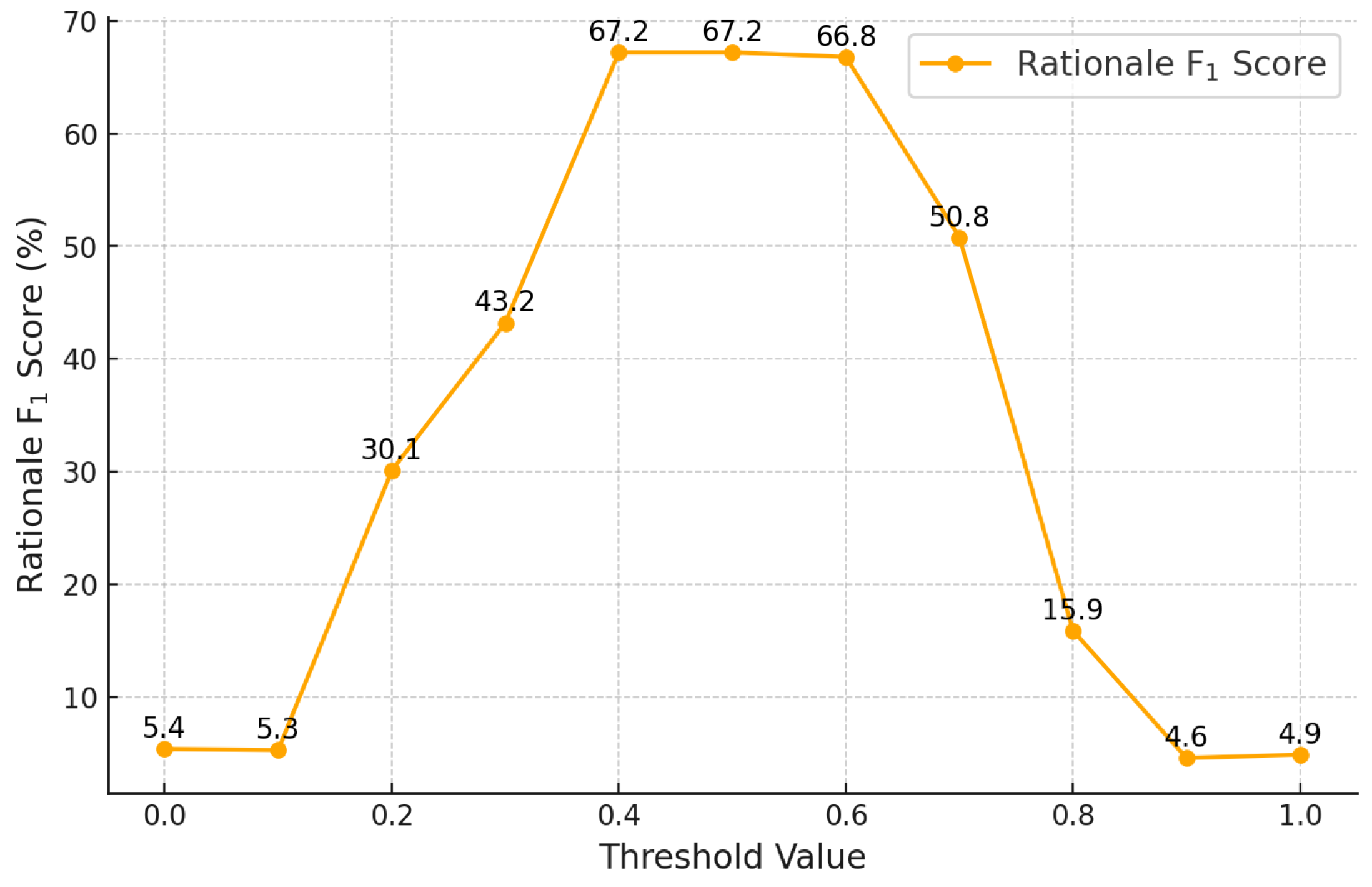

4.5.4. Further Analysis

5. Conclusion

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Implementation Details

-

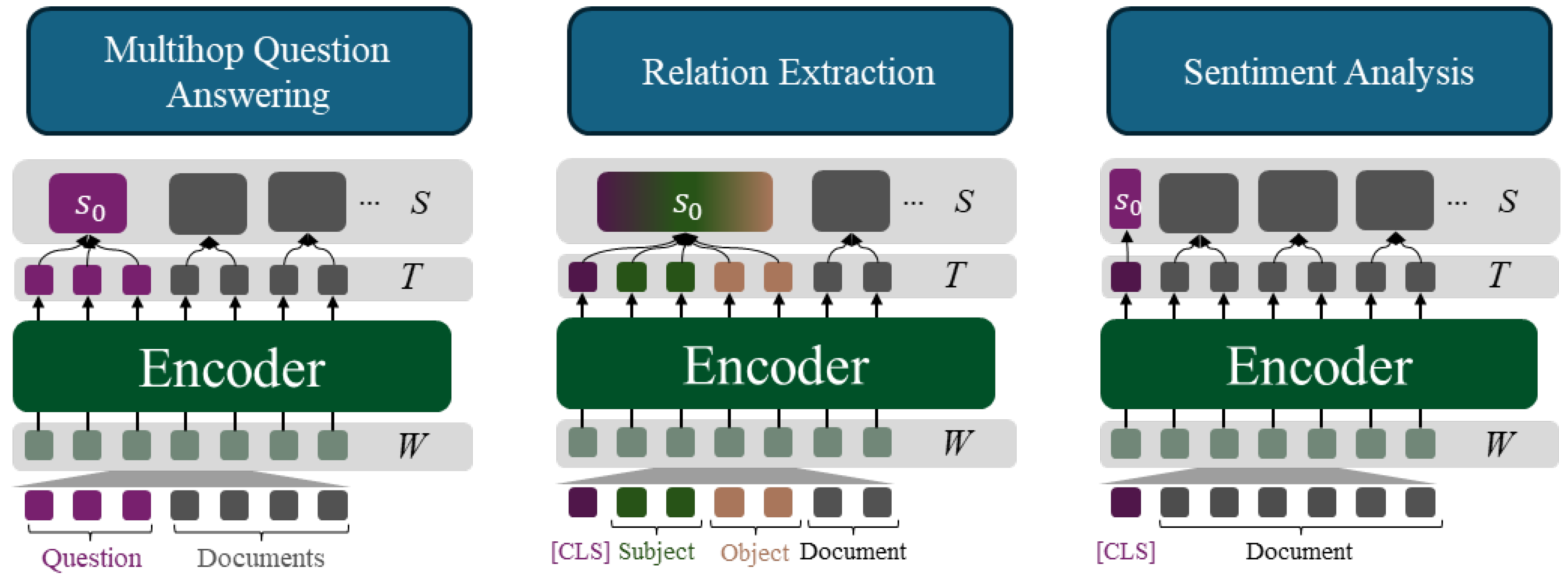

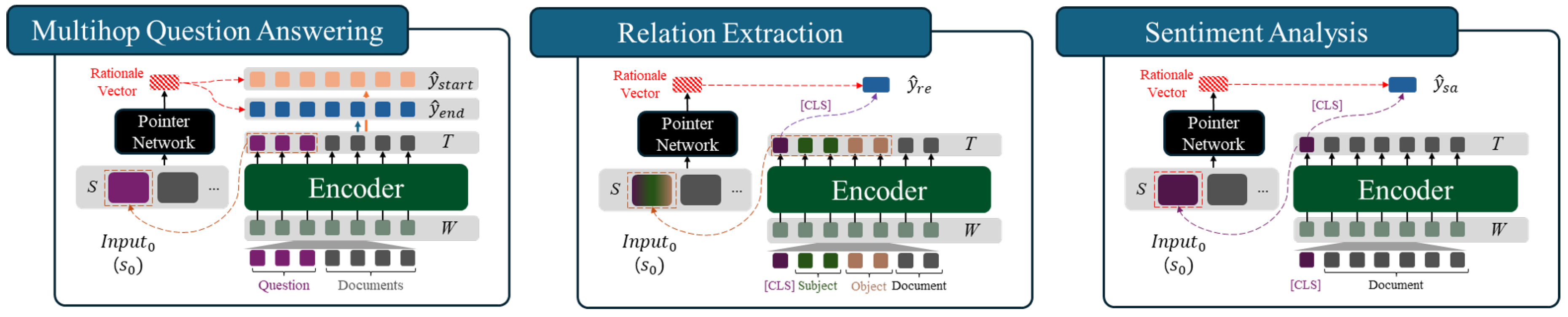

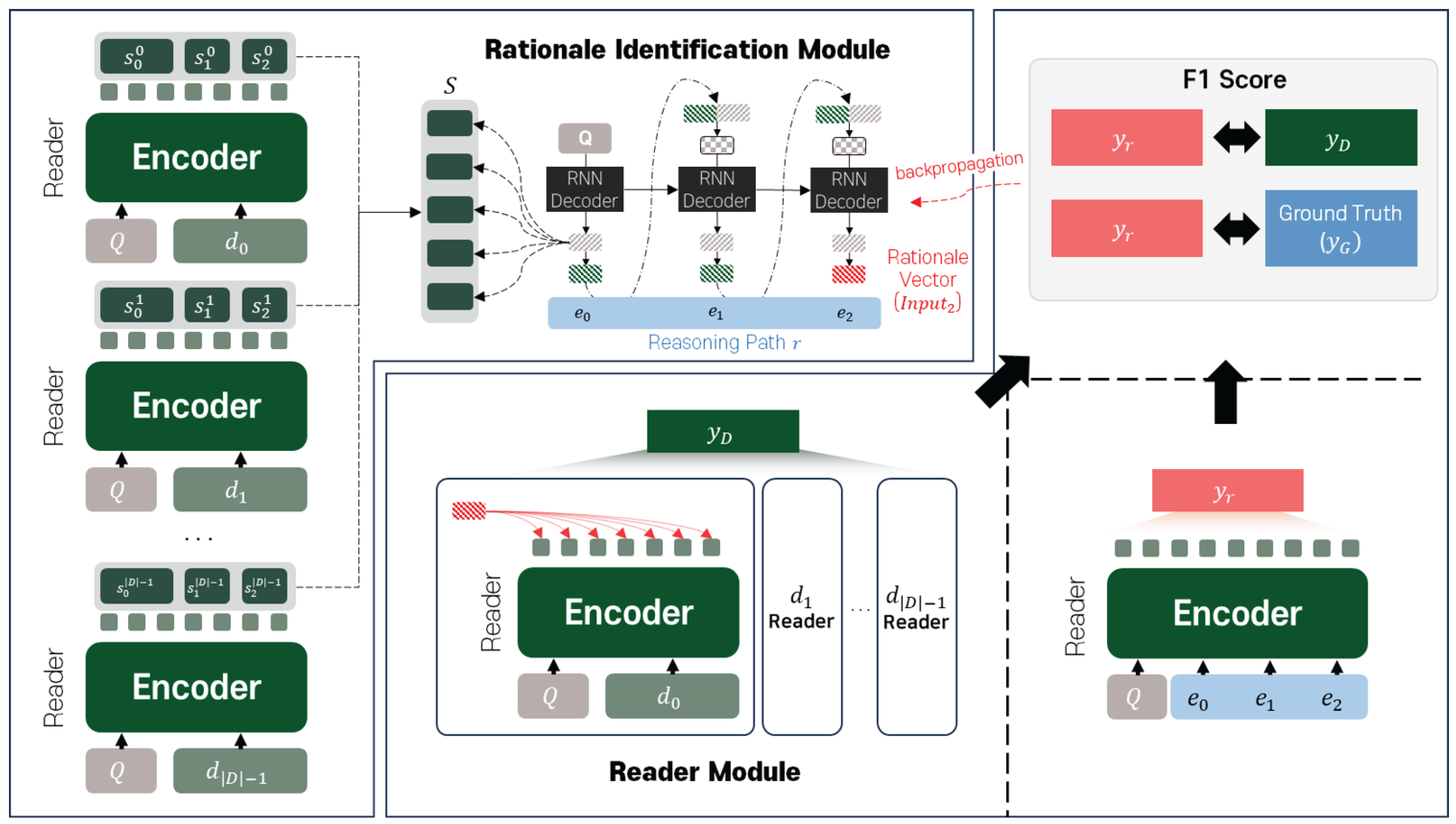

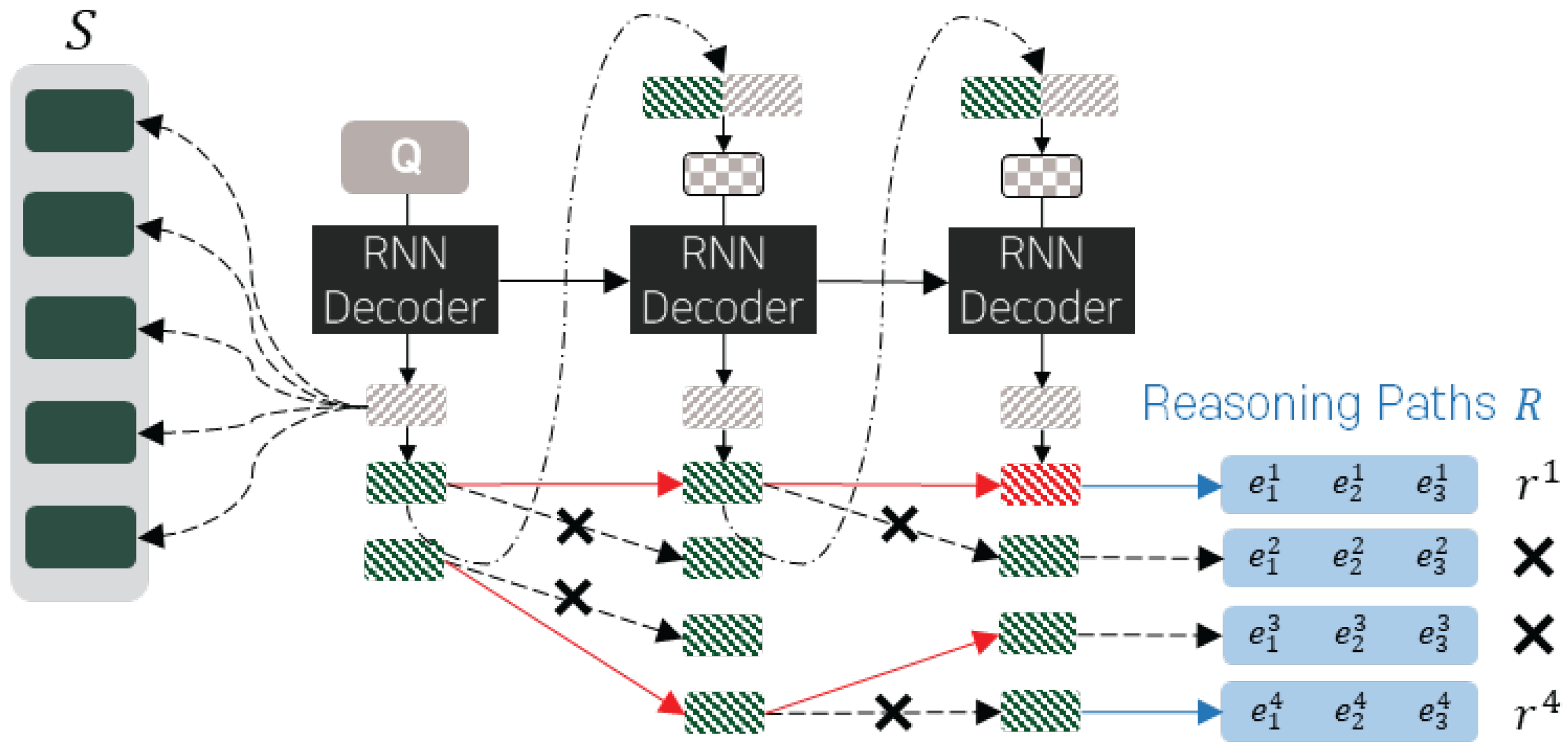

Multi-Hop Question Answering:

- –

- The input sequence T follows the format: ’ Question Document ’. The encoded token representations T are further processed to extract key evidence for reasoning.

- –

- Since each question is associated with multiple documents, each mini-batch contains multiple document-question pairs for the same question.

-

Document-Level Relation Extraction:

- –

- The input T consists of one or more sentences containing entity mentions, where the relationships between entities must be inferred. ELECTRA encodes these token embeddings V, capturing contextual information to analyze entity relationships.

- –

- In this task, each data sample is processed as an individual document, and the mini-batch contains different documents.

-

Binary Sentiment Classification:

- –

- The input T consists of a review text or a short comment, where the final token representations V are used for sentiment classification.

- –

- Similar to relation extraction, each sample corresponds to a single document, and the mini-batch contains different texts.

- For detailed implementation equations of multi-hop question answering, refer to Equation 6.

- Relation extraction involves classifying the relationship between a subject and an object within a given sentence or document. To achieve this, the input sequence follows the structure shown in Figure A2. A probability distribution over relation labels is then computed based on , which contains the contextual information of the input sequence. This process is represented by Equation A1 below.

- Sentiment analysis, as a form of sentence classification, identifies the sentiment within the input text and categorizes it as positive, negative, or neutral. The input and output structure for this task is shown in Figure A2. Similar to relation extraction, a probability distribution over sentiment labels is generated according to Equation A2.

Appendix B. GPT-Based Evaluation Instructions and Inputs for All Tasks

| Instruction |

|---|

| Determine how validly the provided <Sentences>support the given <Answer>to the <Question>. Your task is to assess the supporting sentences based on their relevance and strength in relation to the answer, regardless of whether the answer is correct. The focus is on evaluating the validity of the evidence itself. Even if the answer is incorrect, a supporting sentence can still be rated highly if it is relevant and strong. <Score criteria> - 0 : The sentences do not support the answer. They are irrelevant, neutral, or contradict the answer. - 1 : The sentences provide partial or unclear support for the answer. The connection is weak, lacking context, or not directly related to the answer. - 2 : The sentences strongly support the answer, making it clear and directly inferable from them. <Output format> <Score>: <0, 1, or 2> |

| Input |

| <Question> When did the park at which Tivolis Koncertsal is located open? </Question> <Answer> 15 August 1843 </Answer> <Sentences> Tivolis Koncertsal is a 1,660-capacity concert hall located at Tivoli Gardens in Copenhagen, Denmark. The building, which was designed by Frits Schlegel and Hans Hansen, was built between 1954 and 1956. The park opened on 15 August 1843 and is the second-oldest operating amusement park in the world, after ... </Sentences> <Score>: |

| Instruction |

|---|

| Determine whether the relationship between the given <Subject> and <Object> can be inferred solely from the provided <Sentences>. The <Relationship>may not be explicitly stated, and it might even be incorrect. However, your task is to evaluate whether the sentences themselves suggest the given relationship, regardless of its accuracy. <Score criteria> - 0: The sentences do not suggest the relationship at all. The sentences are neutral, irrelevant, or contradict the relationship. - 1: The sentences somewhat suggest the relationship but are not conclusive. The relationship is partially inferred but not clearly established. - 2: The sentences fully suggest the relationship. The relationship can be clearly and directly inferred from the sentences alone. <Output format> Score: <0, 1, or 2> |

| Input |

| <Sentences> The discovery of the signal in the chloroplast genome was announced in 2008 by researchers from the University of Washington. Somehow, chloroplasts from V. orcuttiana, swamp verbena ( V. hastata) or a close relative of these had admixed into the G. bipinnatifida genome. </Sentences> <Subject> mock vervains </Subject> <Object> Verbenaceae </Object> <Relationship> parent taxon : closest of the taxon in question </Relationship> <Score>: |

| Instruction |

|---|

| Determine whether the given <Sentiment> can be derived solely from the <Supporting Sentences> for the given <Review>. The given <Sentiment>may not be the correct answer, but evaluate whether the <Supporting Sentences> alone can support it. <Score criteria> - 0: The supporting sentences do not support the sentiment at all. The facts are neutral, irrelevant to the sentiment, or contradict the sentiment. - 1: The supporting sentences somewhat support the sentiment but are not conclusive. The sentiment is partially inferred but not clearly. The facts suggest the sentiment but do not decisively establish it. - 2: The supporting sentences fully support the sentiment. The sentiment can be clearly and directly inferred from the facts alone. <Output format> Score: <0, 1, or 2> |

| Input |

| <Sentiment> positive </Sentiment> <Supporting Sentences> A trite fish-out-of-water story about two friends from the midwest who move to the big city to seek their fortune. They become Playboy bunnies, and nothing particularly surprising happens after that. </Supporting Sentences> <Score>: |

Appendix C. GPT-Based Answer and Supporting Sentence Extraction for All Tasks

| Instruction |

|---|

| Answer the given <Question> using only the provided <Reference documents>. Some documents may be irrelevant. Keep the answer concise, extracting only key terms or phrases from the <Reference documents> rather than full sentences. Extract exactly 3 supporting sentences—no more, no less. For each supporting sentence, provide its sentence number as it appears in the reference documents. <Output format> <Answer>: <Generated Answer> <Supporting Sentences>: <Sentence Number 1>, <Sentence Number 2>, <Sentence Number 3> |

| Input |

| <Question> When did the park at which Tivolis Koncertsal is located open? </Question> <Reference documents> Document 1 : Tivolis Koncertsal [1] Tivolis Koncertsal is a 1,660-capacity concert hall located at Tivoli Gardens in Copenhagen, Denmark. [2] The building, which was designed by Frits Schlegel and Hans Hansen, was built between 1954 and 1956. Document 2 : Tivoli Gardens [3] Tivoli Gardens (or simply Tivoli) is a famous amusement park and pleasure garden in Copenhagen, Denmark. [4] The park opened on 15 August 1843 and is the second-oldest operating amusement park in the world, after ... Document 3 : Takino Suzuran Hillside National Government Park [5] Takino Suzuran Hillside National Government Park is a Japanese national government park located in Sapporo, Hokkaido. [6] It is the only national government park in the northern island of Hokkaido. [7] The park area spreads over 395.7 hectares of hilly country and ranges in altitude between 160 and 320 m above sea level. [8] Currently, 192.3 is accessible to the public. ... </Reference documents> <Answer>: <Supporting Sentences>: |

| Instruction |

|---|

| Determine the relationship between the given <Subject>and <Object>. The relationship must be selected from the following list: ‘head of government’, ‘country’, ‘place of birth’, ‘place of death’, ‘father’, ‘mother’, ‘spouse’, ... After selecting the appropriate relationship, provide two key sentence numbers that best support this relationship. <Output format> <Relationship>: <Extracted Relationship> <Supporting Sentences>: <Sentence Number 1>, <Sentence Number 2> |

| Input |

| <Document> [1] Since the new chloroplast genes replaced the old ones, it may be that the possibly ... [2] Glandularia, common name mock vervain or mock verbena, is a genus of annual and perennial herbaceous flowering ... [3] They are native to the Americas. [4] Glandularia species are closely related to the true vervains and sometimes still ... ... </Document> <Subject> mock vervains </Subject> <Object> Verbenaceae </Object> <Relationship>: <Supporting Sentences>: |

| Instruction |

|---|

| Classify the sentiment of the given <Sentence> as either `positive’ or `negative’. After selecting the appropriate sentiment, extract **only two** key sentences that best support this sentiment. <Output format> <Sentiment>: <Extracted Sentiment> <Supporting Sentences>: <Sentence Number 1>, <Sentence Number 2> |

| Input |

| <Document> [1] This movie was awful. [2] The ending was absolutely horrible. [3] There was no plot to the movie whatsoever. [4] The only thing that was decent about the movie was the acting done by Robert ... ... </Document> <Sentiment>: <Supporting Sentences>: |

References

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; Anadkat, S.; et al. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.08774, arXiv:2303.08774 2023.

- Touvron, H.; Martin, L.; Stone, K.; Albert, P.; Almahairi, A.; Babaei, Y.; Bashlykov, N.; Batra, S.; Bhargava, P.; Bhosale, S.; et al. Llama 2: Open foundation and fine-tuned chat models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.09288, arXiv:2307.09288 2023.

- Zhao, W.X.; Zhou, K.; Li, J.; Tang, T.; Wang, X.; Hou, Y.; Min, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, J.; Dong, Z.; et al. A survey of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.18223, arXiv:2303.18223 2023.

- Dubey, A.; Jauhri, A.; Pandey, A.; Kadian, A.; Al-Dahle, A.; Letman, A.; Mathur, A.; Schelten, A.; Yang, A.; Fan, A.; et al. The llama 3 herd of models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.21783, arXiv:2407.21783 2024.

- Bender, E.M.; Gebru, T.; McMillan-Major, A.; Shmitchell, S. On the dangers of stochastic parrots: Can language models be too big? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 ACM conference on fairness, accountability, and transparency; 2021; pp. 610–623. [Google Scholar]

- Bommasani, R.; Hudson, D.A.; Adeli, E.; Altman, R.; Arora, S.; von Arx, S.; Bernstein, M.S.; Bohg, J.; Bosselut, A.; Brunskill, E.; et al. On the opportunities and risks of foundation models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2108.07258, arXiv:2108.07258 2021.

- Rudin, C.; Chen, C.; Chen, Z.; Huang, H.; Semenova, L.; Zhong, C. Interpretable machine learning: Fundamental principles and 10 grand challenges. Statistic Surveys 2022, 16, 1–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shwartz, V.; Choi, Y. Do neural language models overcome reporting bias? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Computational Linguistics; 2020; pp. 6863–6870. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Lin, S.t.; Durrett, G. Multi-hop question answering via reasoning chains. arXiv preprint arXiv:1910.02610, arXiv:1910.02610 2019.

- Wu, H.; Chen, W.; Xu, S.; Xu, B. Counterfactual supporting facts extraction for explainable medical record based diagnosis with graph network. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 conference of the north American chapter of the association for computational linguistics: human language technologies, 2021, pp.

- Zhao, W.; Chiu, J.; Cardie, C.; Rush, A.M. Supervision. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2023, pp.

- Yang, Z.; Qi, P.; Zhang, S.; Bengio, Y.; Cohen, W.; Salakhutdinov, R.; Manning, C.D. Answering. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2018, pp.

- Qi, P.; Lin, X.; Mehr, L.; Wang, Z.; Manning, C.D. Answering Complex Open-domain Questions Through Iterative Query Generation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP), 2019, pp.

- Lewis, P.; Perez, E.; Piktus, A.; Petroni, F.; Karpukhin, V.; Goyal, N.; Küttler, H.; Lewis, M.; Yih, W.t.; Rocktäschel, T.; et al. Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, 33, 9459–9474. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. " Explaining the predictions of any classifier. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining, 2016, pp.

- DW, G.D.A. DARPA’s explainable artificial intelligence program. AI Mag 2019, 40, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.; Xu, F.F.; Araki, J.; Neubig, G. How can we know what language models know? Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2020, 8, 423–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arras, L.; Montavon, G.; Müller, K.R.; Samek, W. Explaining Recurrent Neural Network Predictions in Sentiment Analysis. In Proceedings of the 8th Workshop on Computational Approaches to Subjectivity, Sentiment and Social Media Analysis WASSA 2017: Proceedings of the Workshop.

- Scott, M.; Su-In, L.; et al. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30, 4765–4774. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Melis, D.; Jaakkola, T.S. On the Robustness of Interpretability Methods. arXiv e-prints, 1806. [Google Scholar]

- Gilpin, L.H.; Bau, D.; Yuan, B.Z.; Bajwa, A.; Specter, M.; Kagal, L. Explaining explanations: An overview of interpretability of machine learning. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 5th International Conference on data science and advanced analytics (DSAA). IEEE; 2018; pp. 80–89. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Liu, K. Alignment rationale for natural language inference. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers), 2021, pp.

- Atanasova, P.; Simonsen, J.G.; Lioma, C.; Augenstein, I. Diagnostics-guided explanation generation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2022, Vol.

- Welbl, J.; Stenetorp, P.; Riedel, S. Constructing datasets for multi-hop reading comprehension across documents. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2018, 6, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Min, S.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Hajishirzi, H. Presuppositions. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), 2023, pp.

- Glockner, M.; Habernal, I.; Gurevych, I. Why do you think that? exploring faithful sentence-level rationales without supervision. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.03384, arXiv:2010.03384 2020.

- Min, S.; Zhong, V.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Hajishirzi, H. Multi-hop Reading Comprehension through Question Decomposition and Rescoring. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2019, pp.

- Mao, J.; Jiang, W.; Wang, X.; Liu, H.; Xia, Y.; Lyu, Y.; She, Q. Explainable question answering based on semantic graph by global differentiable learning and dynamic adaptive reasoning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2022, pp.

- Groeneveld, D.; Khot, T. HotpotQA. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP). [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Wang, Y.; Hu, X.; Wu, Y.; Yan, H.; Zhang, X.; Cao, Z.; Huang, X.; Qiu, X. Rethinking label smoothing on multi-hop question answering. In Proceedings of the China National Conference on Chinese Computational Linguistics. Springer; 2023; pp. 72–87. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, K. Electra: Pre-training text encoders as discriminators rather than generators. arXiv preprint arXiv:2003.10555, arXiv:2003.10555 2020.

- Vinyals, O.; Fortunato, M.; Jaitly, N. Pointer networks. Advances in neural information processing systems 2015, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, J.; Gulcehre, C.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Empirical evaluation of gated recurrent neural networks on sequence modeling. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.3555, arXiv:1412.3555 2014.

- Brown, P.F.; Della Pietra, S.A.; Della Pietra, V.J.; Mercer, R.L. The mathematics of statistical machine translation: Parameter estimation. Computational linguistics 1993, 19, 263–311. [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi, H.; Balasubramanian, N.; Khot, T.; Sabharwal, A. MuSiQue: Multihop Questions via Single-hop Question Composition. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2022, 10, 539–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Ye, D.; Li, P.; Han, X.; Lin, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Huang, L.; Zhou, J.; Sun, M. Dataset. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2019, pp.

- Maas, A.L.; Daly, R.E.; Pham, P.T.; Huang, D.; Ng, A.Y.; Potts, C. Learning Word Vectors for Sentiment Analysis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 49th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, 2011, pp.

- Kullback, S.; Leibler, R.A. On information and sufficiency. The annals of mathematical statistics 1951, 22, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, S.E.; Walker, S.; Jones, S.; Hancock-Beaulieu, M.M.; Gatford, M.; et al. Okapi at TREC-3. Nist Special Publication Sp 1995, 109, 109. [Google Scholar]

- You, H. Multi-grained unsupervised evidence retrieval for question answering. Neural Computing and Applications 2023, 35, 21247–21257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. Gpt-4o mini: advancing cost-efficient intelligence, 2024. https://openai.com/index/gpt-4o-mini-advancing-cost-efficient-intelligence/.

| Dataset | Train set | Test set | Sampled Test set |

|---|---|---|---|

| HotpotQA | 90,564 | 7,405 | 1000 |

| MuSiQue | 25,494 | 3,911 | 1000 |

| DocRED | 56,195 | 17,803 | 1000 |

| IMDB | 25,000 | - | 1000 |

| Models | Answer | Rationale | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precision | Recall | |||

| BM25 | - | - | - | 40.5 |

| RAG-small | 62.8 | - | - | 49.0 |

| Semi-supervised | 66.0 | - | - | 64.5 |

| You (2023) | 50.9 | - | 74.2 | - |

| HUG | 66.8 | - | - | 67.1 |

| Proposed Model | 60.2 | 60.1 | 76.5 | 67.2 |

| Upperbound | 61.1 | 82.8 | 80.5 | 80.7 |

| Models | Answer | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| BM25 | - | 12.9 |

| RAG-small | 24.2 | 32.0 |

| HUG | 25.1 | 34.2 |

| Proposed Model | 25.0 | 35.4 |

| Models | Answer | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| GPTpred | 41.8 | 21.8 |

| Proposed Model | 81.8 | 54.9 |

| Models | Dataset | Overall | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HotpotQA | MuSiQue | DocRED | IMDB | ||

| GPTpred | 92.4 | 81.0 | 51.0 | 95.4 | 79.9 |

| GPTgold | 95.5 | 82.6 | 65.0 | - | - |

| Proposed Model | 87.5 | 55.9 | 87.2 | 88.7 | 79.8 |

| Models | Answer | Evidence | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precision | Recall | |||

| Proposed Model | 60.2 | 60.1 | 76.5 | 67.2 |

| - Loss | 60.5 | 47.7 | 61.1 | 52.9 |

| - Beam | 60.8 | 55.3 | 68.2 | 61.1 |

| - Loss & Beam | 60.4 | 47.3 | 60.9 | 52.7 |

| Models | Test set | Sampled Test set |

|---|---|---|

| Proposed Model (All Document Input ⇔ Only Rationale Sentences Input) |

84.9 | 93.3 |

| Proposed Model (Ground Truth ⇔ Only Rationale Sentences Input) |

60.2 | 90.3 |

| Proposed Model (All Document Input ⇔ Ground Truth) |

60.2 | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).