1. Introduction

Sheep reproductive efficiency is a primary determinant of flock profitability and global meat production. Among indigenous breeds, Hu sheep are renowned for their exceptionally high litter size (average 2.5–3.0 lambs per parturition); however, the molecular drivers of this prolificacy remain unclear. Endometrial receptivity and stromal cell (ESC) plasticity are rate-limiting factors for embryo survival and conceptus elongation; however, the genetic determinants governing these processes remain elusive.

Oestrogen receptor α (encoded by ESR1) is a pivotal nuclear receptor that transduces oestradiol signals essential for uterine growth, stromal proliferation, and decidualization. The functions of protein-coding genes are primarily determined by their protein products. ESR1 gene encodes oestrogen receptor α (ERα), a subtype of oestrogen receptors (ERs) [

1], predominantly expressed in the organs of the reproductive system, such as the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, uterus, cervix, vagina, and mammary gland [

2].

ESR1 is crucial for various physiological functions, such as reproduction, and is involved in several diseases. During reproduction, when ESR1 is knocked out in the uterine epithelium, no embryo implantation occurs following either natural mating or embryo transfer, indicating its crucial role in establishing uterine receptivity [

3]. During the oestrus cycle, the effects of oestrogen and ERα, encoded by ESR1, are required for the development of the luteolytic mechanism in the epithelium of the uterine endometrial luminal and superficial ductal glands [

4]. The expression level of ERα in the uterine artery endothelium during the luteal phase is 40% of that during the follicular phase [

5,

6]. Due to anovulation and a lack of corpora lutea, ESR1 null (αERKO) female mice are infertile. By 50 days of age, αERKO mice exhibit reproductive abnormalities, such as increased gonadotropin and gonadotropin receptor levels and theca cell hypertrophy [

7,

8]. Additionally, ERα can be detected in male tissues, and its localisation differs among species[9-11]. ERα exists in the caput, corpus, cauda, and testis of ovine and is crucial for spermatogenesis [

12]. In summary, ESR1 plays a key role in animal reproduction. Our earlier transcriptome analysis of the endometrial epithelium at the oestrus stage revealed the differential expression of ESR1 in high- and low-fertility Hu sheep. However, most studies have focused on ovarian or hypothalamic expression, and a direct functional link between endometrial ESR1 and fecundity has not yet been established. Critically, Hu sheep exhibit markedly higher endometrial ESR1 mRNA and ERα protein abundance than low-fecundity breeds, suggesting a tissue-specific role in reproductive outcomes.

ESCs are the principal cellular substrates for embryo attachment and subsequent placentation, and their proliferation, apoptosis, and migratory capacities are tightly regulated by steroid hormones. Dysregulation of ESC fate decisions has been implicated in early embryonic loss, recurrent implantation failure, and reduced litter size. Despite these clinical and economic implications, the molecular circuitry through which ESR1 modulates ESC function in sheep remains unclear.

To fill this knowledge gap, we conducted a multilevel investigation combining transcript profiling of the Hu sheep endometrium with loss-of-function studies of primary ovine ESCs.

2. Results

2.1. Expression and Location of ESR1/ERα

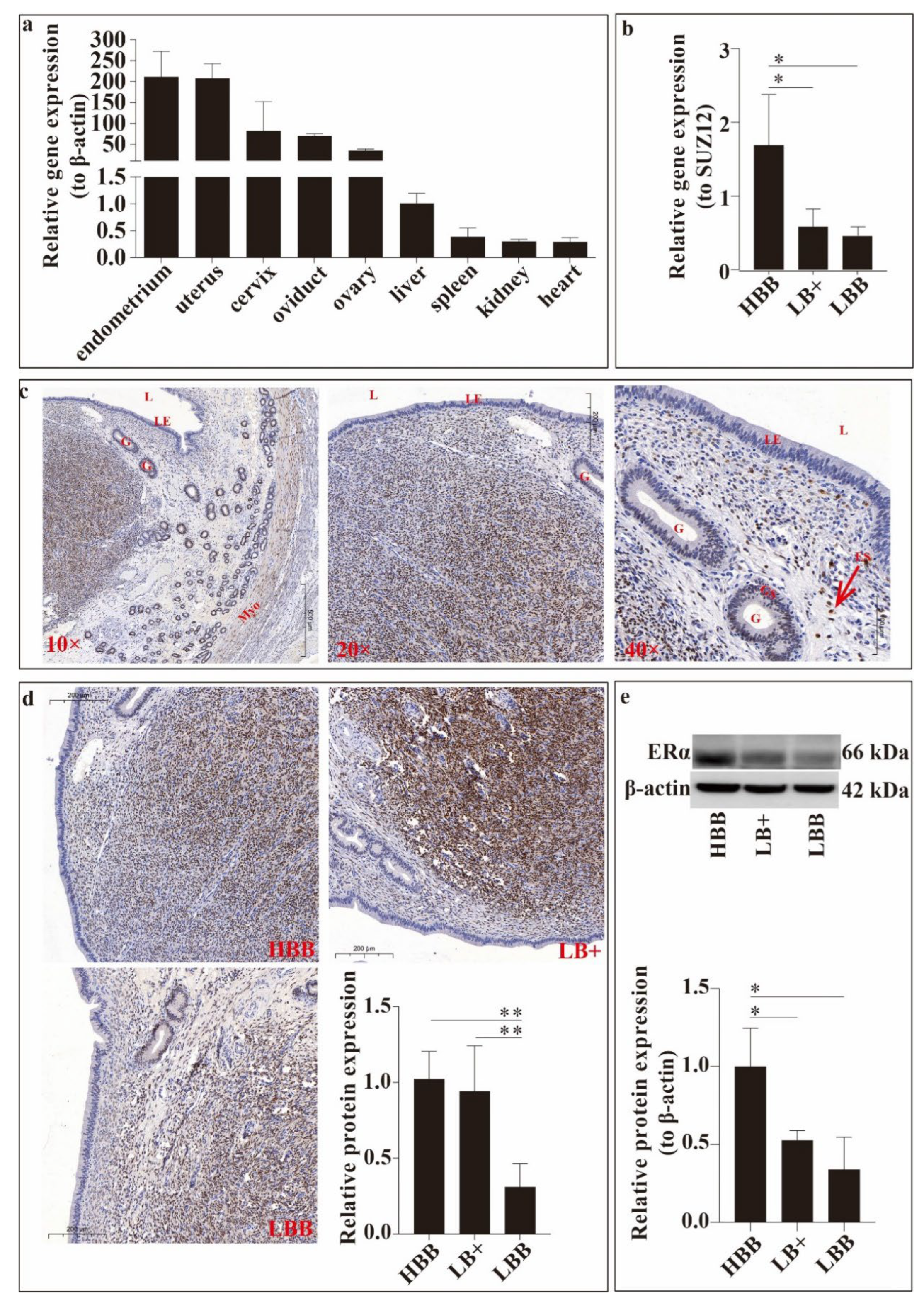

ESR1 expression was detected in the liver, heart, spleen, kidneys, cervix, uterus, oviduct, and ovary. As shown in

Figure 1, the relative expression of ESR1 varied between samples. The relative expression level of ESR1 was observed to be the highest in the uterus and endometrium, and the relative expression in the cervix, oviduct, and ovary was the second highest, followed by that in the liver, heart, spleen, and kidney (

Figure 1a).

Second, we compared the relative expression of ESR1 in Hu sheep endometria with different fecundities using Real-Time Quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) (

Figure 1b). ESR1 expression in the endometrial group HBB endometrium was significantly higher than that in the other groups (

P < 0.05).

Subsequently, the localisation of ERα in the uterine horn was detected using immunocytochemistry staining (

Figure 1c). ERα immunoreactivity was detected in the glandular epithelium, myometrium, and endometrial stroma of the uterus.

Finally, we compared endometrial ERα expression at the organizational and molecular levels in Hu sheep with different fecundities using immunocytochemical staining (

Figure 1d) and western blotting (

Figure 1e). As shown in

Figure 1d, ERα expression levels in the HBB and LB+ groups were significantly higher than those in the LBB group (

P < 0.01). The same trend was observed at the molecular level (

Figure 1e), and the expression level in the HBB group was significantly higher than that in the LB+ and LBB groups (

P < 0.05).

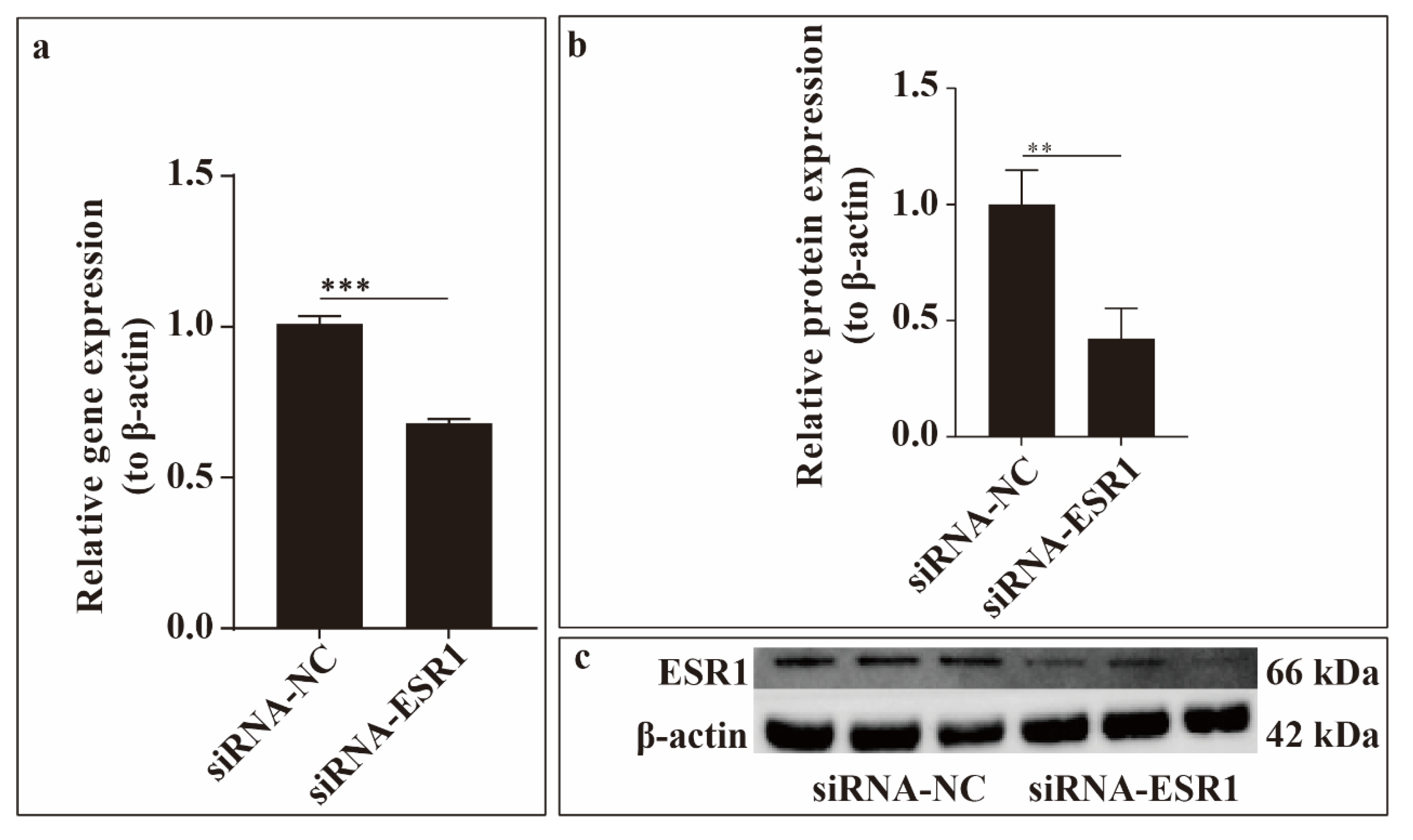

2.2. Verification of siRNA-ESR1 Transfection Efficiency

To investigate the effect of ESR1 inhibition on ESCs

in vitro, we constructed siRNA-ESR1. We then performed ESR1 loss-of-function assays to validate transfection efficiency in ESCs. The results shown in the figure revealed that ESR1 expression was significantly decreased after siRNA-ESR1 transfection compared to the negative control (NC) at the gene (using qRT-PCR) and protein (using western blotting) levels (

Figure 2). Therefore, siRNA-ESR1 was used in subsequent experiments.

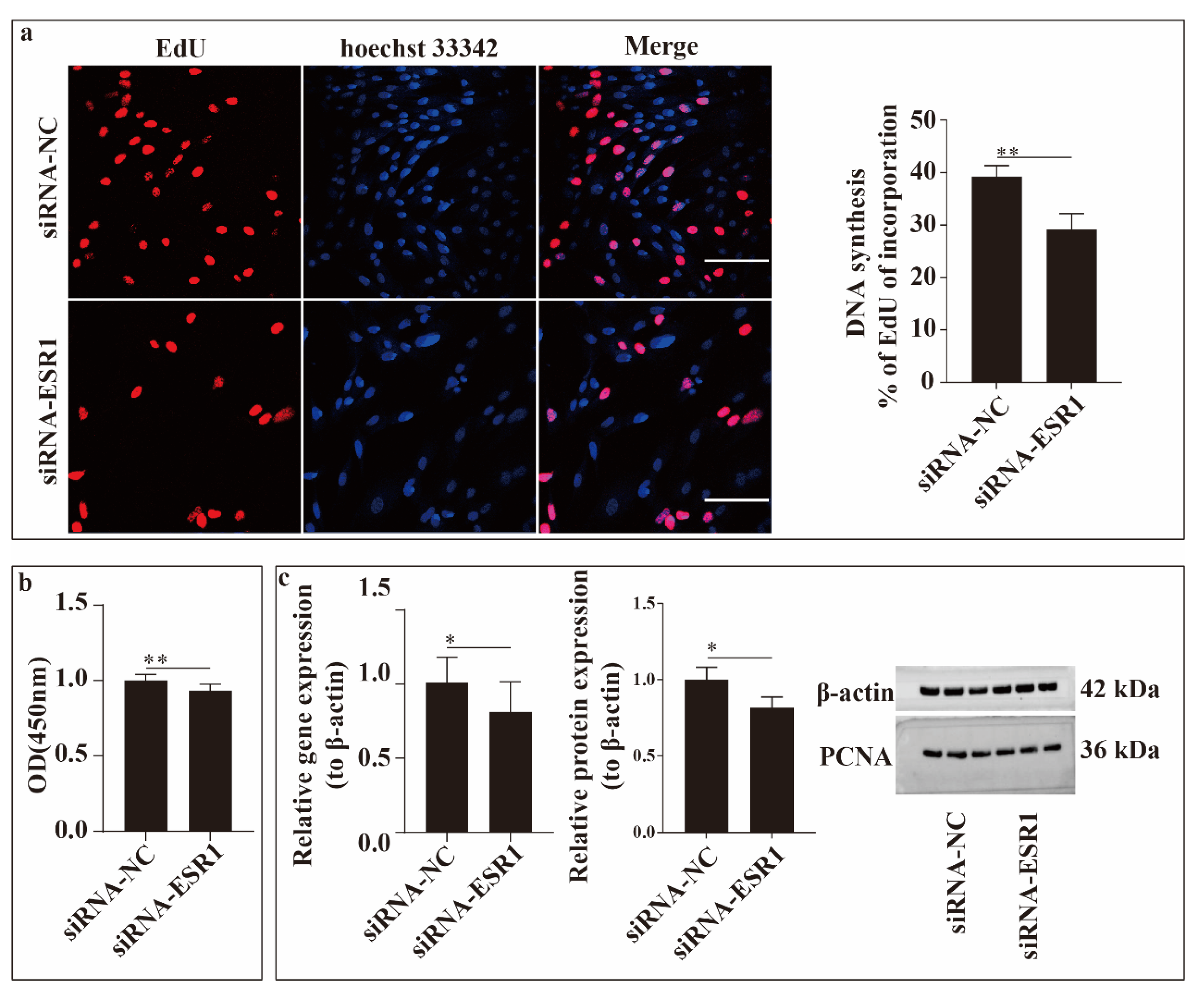

2.3. ESR1 Knockdown Inhibits ESCs Proliferation In Vitro

To study the function of ESR1 in ESCs proliferation

in vitro, EdU incorporation and CCK-8 assays were conducted (

Figure 3). As shown in

Figure 3a, ESR1 knockdown significantly reduced (

P < 0.01) the number of proliferating cells (

P < 0.01). Cell viability was assessed using the CCK-8 assay, and it significantly decreased (

P < 0.01) when ESR1 was knocked down (

Figure 3b). Additionally, the expression of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), a key gene in cell proliferation, was detected at the gene (using qRT-PCR) and protein (using western blotting) levels. The results of the two levels shown in the figure suggest that PCNA expression was downregulated (

P < 0.05) when ESR1 expression was knocked down (

Figure 3c). Thus, from these results, we can infer that downregulating the expression of ESR1 in ESC cultured

in vitro inhibits cell proliferation and that ESR1 can promote cell proliferation.

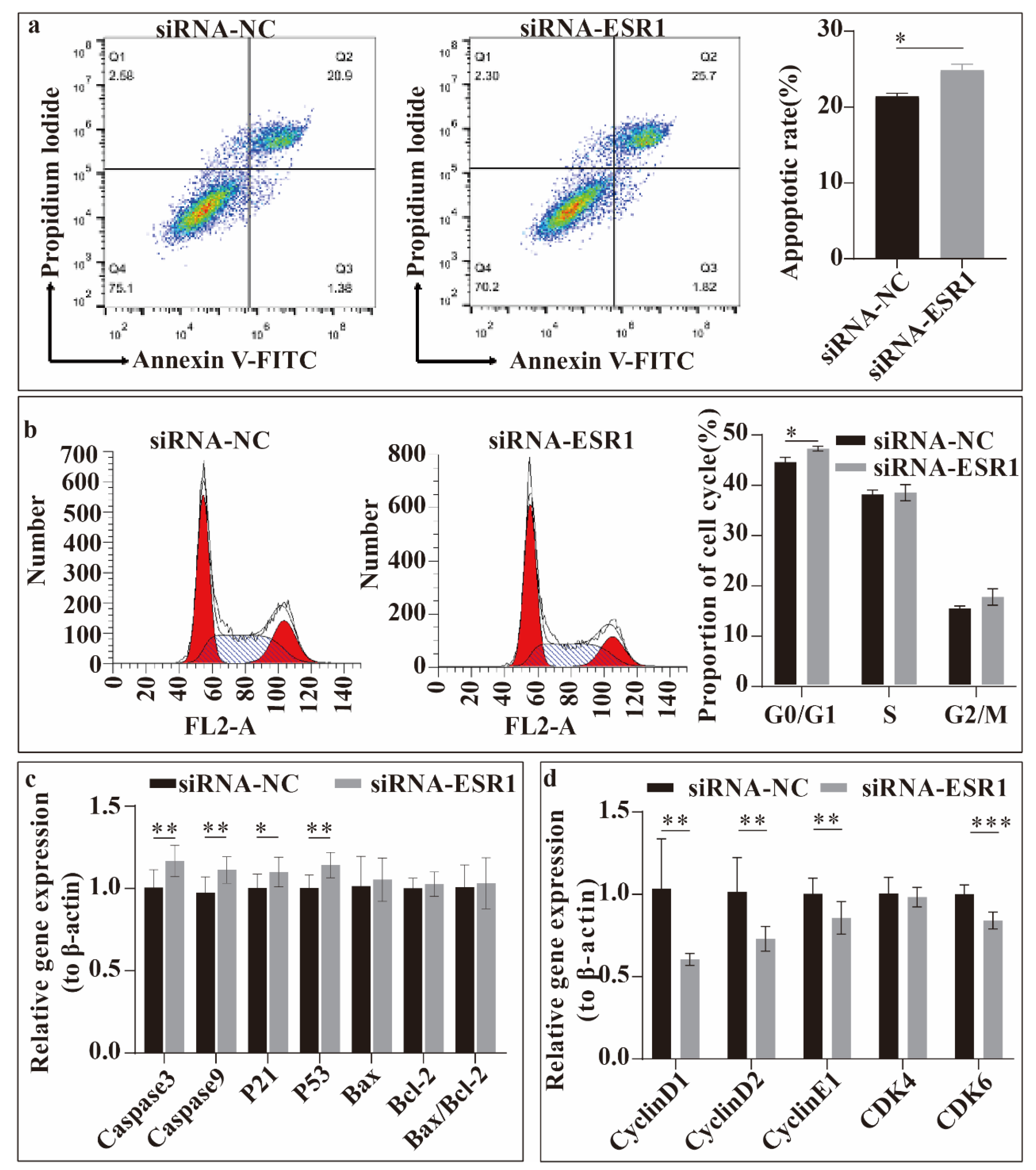

2.4. ESR1 Knockdown Accelerated Cell Apoptosis and Arrested Cell Cycle Progress in Hu Sheep ESCs

Then, we studied the effect of ESR1 gene on ESCs apoptosis and cell cycle progress

in vitro (

Figure 4), and the apoptosis rate was detected firstly. FACS analysis showed that the ESCs apoptosis rate was significantly increased (

P < 0.05) after transfection with siRNA-ESR1 (

Figure 4a). Second, the cell cycles of sheep ESCs transfected with siRNA-ESR1 were compared. When transfected with siRNA-ESR1, the percentage of cells was significantly decreased (

P < 0.05) in G0/G1 phase (

Figure 4b). The relative expression levels of apoptosis-and cell cycle-related genes were evaluated. As shown in

Figure 4c,d, the relative expression of genes Caspaes3 (

P < 0.01), Caspase9 (

P < 0.01), P21 (

P < 0.05), and P53 (

P < 0.01) increased once ESR1 gene was interfered (

Figure 4c). The relative expression of several genes related to the cell cycle, including Cyclin D1, Cyclin D2, Cyclin E1, CDK4, CDK6, was tested. Transfection with siRNA-ESR1 significantly decreased the expression of Cyclin D1, Cyclin D2, Cyclin E1 and CDK6 (

P < 0.01) (

Figure 4d). Thus, ESR1 suppresses Hu sheep ESCs apoptosis

in vitro. Transfection with siRNA-ESR1 inhibited cell cycle progression, indicating that ESR1 promotes cell-cycle progression.

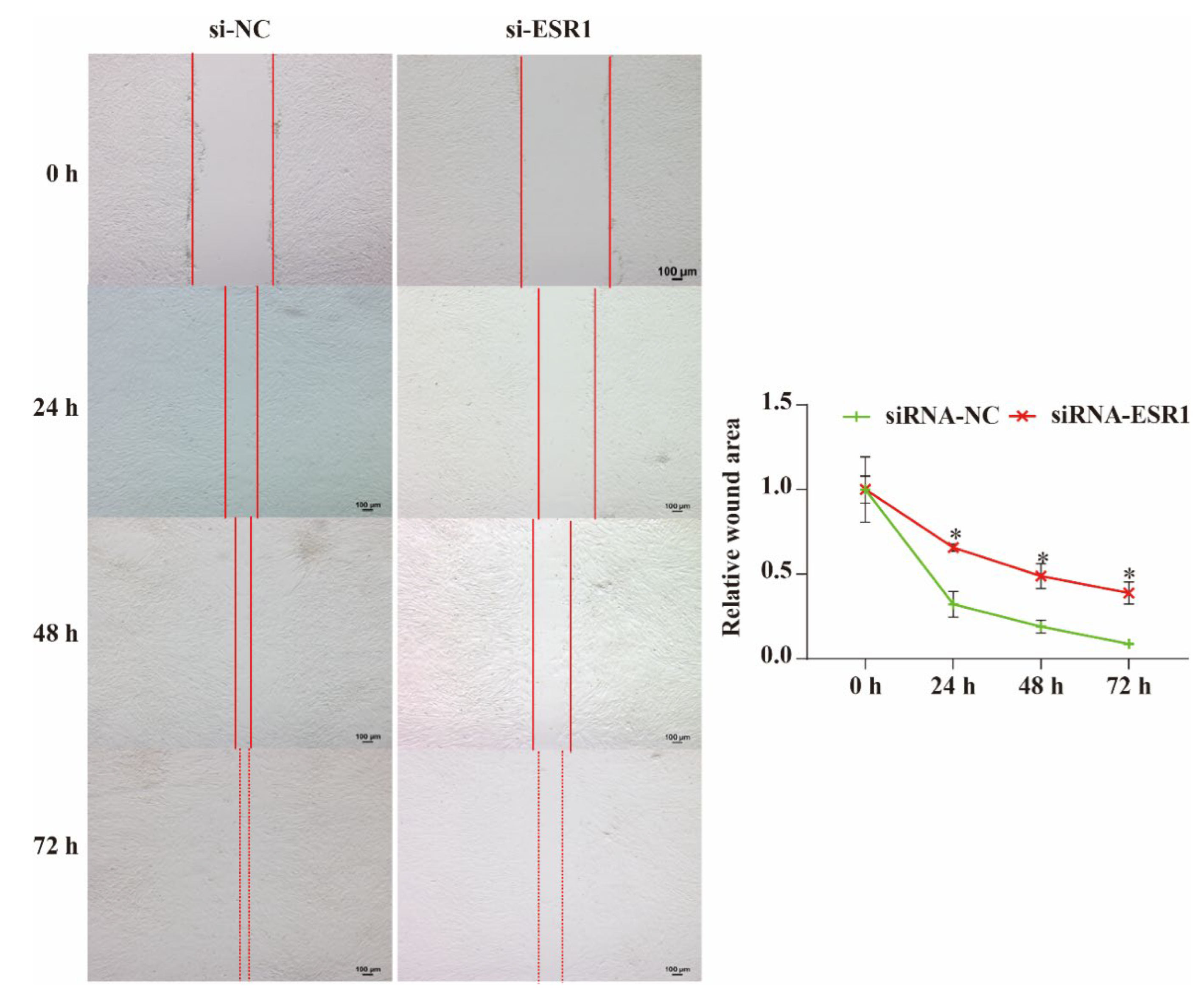

2.5. ESR1 Knockdown Inhibits Migration of Hu Sheep ESCs In Vitro

The wound assay results showed that the relative scratch width gradually decreased as the incubation time increased (

Figure 5). If ESR1 of ESCs was knocked down, the relative scratch widths at 24, 48, and 72 h were significantly larger (

P < 0.05) than those of the non-knocked down cells. Therefore, we can conclude that ESCs migration is inhibited when ESR1 is disrupted and that ESR1 can promote ESCs migration

in vitro.

3. Discussion

In mice, oestrogen acts on uterine stromal and epithelial cells by binding to its receptor ERα, which is encoded by the ESR1 gene [

13]. ESR1 knockout in the endometrial epithelium, stroma, cavity, and glandular epithelium leads to abnormal decidualization in mice [

14]. This indicates that ESR1 plays a crucial role in uterine function. In this study, we detected the relative expression levels of ESR1 in different organs of Hu sheep and observed that ESR1 was highly expressed in reproductive organs such as the endometrium, uterus, cervix, oviduct, and ovary. The relative expression levels of ESR1 and ERα encoded by it in the endometrium of high-reproductive Hu sheep were higher than those in low-reproductive Hu sheep, suggesting that ESR1 may play an important role in sheep reproductive performance. To investigate the function of ESR1 in the sheep uterus, ESCs were selected as the research subjects based on

Figure 1b, and ESR1 gene function was investigated by comparing the differences between ESCs with and without ESR1 knockdown.

The expression of ESR1/ERα is a marker of uterine gland formation in sheep, which involves changes in the epithelial phenotype [

15]. Endometriosis is caused by the retrograde movement of shed endometrium to the abdominal cavity and other locations. Oestrogen, through its receptor ERα, leads to a significant increase in cell height and proliferation, indicating that ERα promotes endometrial proliferation [

16]. PCNA plays an important role in regulating cell proliferation, DNA repair, and replication [

17] and is used as a biomarker for cell proliferation [

18]. In our study, ESR1 knockdown resulted in a decrease in PCNA expression in ESC at both the gene and protein levels, indicating that ESC proliferation was inhibited, which is consistent with the results of EdU and CCK-8 detection.

Apoptosis is a form of cell death regulated by intracellular caspases 3/7 [

19]. Caspase3/7 is activated in response to extracellular cell death-inducing cytokines [

20]. In addition, apoptosis dependent on Caspase9 is initiated by DNA damage, endoplasmic reticulum stress, reactive oxygen species accumulation, and growth factor deficiency [

21]. A critical step in the Caspase9-mediated apoptotic pathway is the regulation of Bcl-2 family proteins [

22]. Bcl-2 and Bax belong to the Bcl-2 family [

23], and their interaction maintains the integrity of the outer mitochondrial membrane [

24] to inhibit the release of apoptotic proteins that activate caspases [

25]. Knocking down ESR1 gene expression in ESCs resulted in increased expression of Caspase3 gene and Caspase9 gene, leading to an increase in cell apoptosis, as detected using flow cytometry. No remarkable changes were observed in the expression of Bcl-2 and Bax, indicating that the mitochondria may not have been affected by treatment.

The cell cycle can be classified into three phases: G0/G1, S, and G2/M, according to the number of chromosomes. The eukaryotic cell cycle is mainly regulated by the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDKs)-cyclin complex [

26]. In mammalian cells, the CDK4/CDK6-Cyclin D complex activates and drives G1 phase progression and the CDK2-Cyclin E complex regulates the transition from the G1 to S phase, the CDK2-Cyclin A complex controls the S and G2 phases [

27]. P53 is a transcription factor, and P21, a CDK1/2/4/6 inhibitor that halts cell cycle progression, is one of the main transcriptional targets of P53 [

28]. P53/P21 pathway can inhibit cell cycle progression by blocking CDKs activity [

29]. In the current study, the cell cycle was arrested in the G0/G1 phase after interference with ESR1, possibly because of the upregulation of P53 and P21 expression, which inhibited CDK4/6 activity.

Normally, cells migrate collectively to form tissues and organs and to heal wounds [

30]. Studies have shown that a thin endometrium is an important risk factor for implantation failure [

31]. When the endometrial thickness is less than 7 mm, a positive correlation exists between thickness and implantation failure [

32]. In mice, enhanced ESC activity and migration promote the recovery of endometrial function and increase fertility, possibly due to the enhanced mesenchymal epithelial transition of ESC [

31]. In our study, after reducing the expression of ESR1 in ESC, the healing speed of scratches decreased, suggesting that ESR1 can promote the migration of ESC, which is beneficial for maintaining the normal function of the endometrium. However, it should be pointed out that this article only studied the phenotypic effects of ESR1 gene knockdown on ESC, and did not investigate the overexpression of ESR1 gene, which makes the research results slightly flawed. Further research should be conducted in vivo, and the ESR1 gene should be knocked down and overexpressed to clarify the mechanism by which this gene affects sheep fertility.

4. Materials and Methods

All animal studies were conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals formulated by Nanjing Agricultural University (SYXK 2011-0036).

4.1. Tissue Sample Collection

According to the three successive lambing records and FecB genotype [

33], nine healthy multiparous ewes (approximately 55 kg) were divided into three groups: HBB, LBB, and LB+, with three ewes in each group; HBB indicates high prolificacy and is homozygous for the FecB mutation (litter size = 3). LBB or LB+ indicates low prolificacy with homozygous or heterozygous FecB mutations (litter size = 1). To ensure that the ewes were in a similar physiological state when the samples were collected, sampling was conducted during the subsequent oestrus period after synchronous oestrus. The ewes were treated with vaginal sponge suppositories containing progesterone for 11 days. Each ewe was injected with 0.2 mg cloprostenol at the time of sponge removal. A ram was used to determine whether the ewes were in oestrus, and the time spent in oestrus was recorded. The ewes were slaughtered during the next oestrus to collect samples. After slaughter, endometrial samples were scraped from one of the uterine horns on the same side and position of each sheep and immediately stored in liquid nitrogen for subsequent analysis. The other horn was secured with 4% paraformaldehyde for immunohistochemical analysis [

34]. Simultaneously, approximately 1 cm3 of samples were collected from other visceral tissues, including the liver, heart, spleen, kidney, cervix, uterus, oviduct, and ovary, and stored in liquid nitrogen.

4.2. Cell Isolation and Culture

A uterine horn was collected from a non-pregnant ewe and transported to the laboratory under aseptic conditions. Sheep ESCs were obtained and identified as previously reports [

35,

36,

37]. DMEM/F12 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with a foetal bovine serum volume fraction of 15% was used to culture the cells. Culture conditions: temperature was 37 °C and CO2 density was 5%.

4.3. Total RNAs of Tissue and Cell Isolation and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from the samples using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Waltham, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and evaluated for concentration and purity [

38]. Subsequently, qualified total RNA samples were used to synthesise cDNA using reverse transcriptase (Vazyme, Nanjing, China), and the samples were frozen at −20 °C for future use.

Primers were designed and assessed using the NCBI database. Primer pairs were used for quantification when the PCR amplification efficiency was between 0.9 and 1.1. The primer pairs used in this study are listed in

Table 1. SYBR Green (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) was used for RT-qPCR in a reaction volume of 20 μL [

39].

The relative gene expression levels of SUZ12 (endometrial tissue samples) or β-actin (other samples) were quantified using the 2-ΔΔCT method. The PCR amplifications were carried out in three stages: the 1st stage was the hold stage, with the temperature maintained at 95 °C for 5 min; the 2nd stage was the PCR stage, with a program cycle of 40 cycles at 95 °C for 10 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 95 °C for 15 s; the 3rd stage was the melt curve stage, with the temperature maintained at 95 °C for 15 s.

4.4. Immunohistochemistry

Uterine horn samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and paraffin sections were then prepared. The samples were baked at 60 °C for 30 min to fix them, then de-paraffinised with xylene, and hydrated using a gradient ethanol solution. Next, the slices were boiled in citrate buffer solution for 10 min and allowed to cool naturally for antigen retrieval. The cells were then treated with 3% H2O2 for 10 min and blocked with 5% BSA for 20 min to block endogenous peroxidase and reduce nonspecific binding. The sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-ERα primary monoclonal mouse antibodies (1:250 dilution, Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX, USA). After incubation, the sections were rinsed three times with 1×PBS and then incubated with a secondary antibody (diluted 200 times, Biosynthesis Biotechnology, Beijing, China), homologous to the primary antibody, at 37 °C. PBS was used as the primary antibody in negative controls. Finally, paraffin sections were stained with 3, 3’- diaminobenzidine (Beyotime, Haimen, China) at room temperature, and images were captured using a microscope (Nikon, Japan).

4.5. Western Blot

First, tissue or cell samples were lysed with an appropriate amount of RIPA protein lysis buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China), and 1 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride was added a few minutes before use. This step was performed on ice for 30 min, and the tissue samples were homogenised before lysis. Second, the samples were centrifuged, and the supernatant was collected for subsequent experiments. The protein concentration in the supernatant was determined using the BCA method (BCA assay kit; Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Third, proteins were separated based on their molecular size using a 12% polyacrylamide gel containing sodium dodecyl sulphate. After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), and the membranes were sealed with 5% (w/v) skim milk powder prepared with TBST for 2 h for blocking the non-specific binding sites. The membranes were then incubated sequentially with primary and secondary antibodies. The PVDF membranes were imaged using an imaging system (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan), and the relative expression levels of the target proteins were analysed using image J software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) based on the grayscale values in the image. The details of the antibodies used for immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence are listed in

Table 2.

4.6. siRNA Transfection in ESCs

The cells were cultured in 6-well plates after resuscitation. Small interfering RNAs (siRNA) were synthesised according to the sequences shown in

Table 3. When the degree of growth convergence reached 70–90%, the cells were transfected with siRNAs-ESR1 using the Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were collected 24 h after transfection for further analysis.

4.7. Analysis of Cell Proliferation

Proliferation capacities were assessed in both ESR1-knockdown and control ESCs to evaluate gene function by detecting cell metabolic activity (CCK-8 assay) and DNA synthesis (EdU assay) (KeyGen, Nanjing, China), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

4.8. Analysis of Apoptosis and Cell Cycle

Changes in apoptosis and cell cycle were detected using flow cytometry after interfering with the ESR1 gene in ESC. Briefly, cells transfected with siRNA-ESR1 were collected and rinsed three times with DPBS. To detect apoptosis, the cells were resuspended in pre-cooled 1× binding buffer, and the concentration was adjusted to 1 × 106 cells/mL. A 100 μL cell suspension (approximately 1 × 10⁵ cells) was transferred to a flow tube, mixed with 5 μL of Annexin V-FITC reagent, and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. Next, 5 μL of propidium iodide reagent (PI) was added, mixed gently, and the samples were incubated on ice for 5 min. All experiments were conducted in the dark. Finally, 400 μL of binding buffer was added, gently mixed, and the samples were immediately analysed to assess apoptosis (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lake, NJ, USA). For cell cycle analysis, harvested cells were first resuspended in DPBS, followed by dropwise addition of ice-cold 70% ethanol (−20 °C) with continuous vortexing. After overnight fixation at 4 °C, the samples were centrifuged to remove ethanol and washed 1–2 times with DPBS. Subsequently, 500 μL of RNase A (final concentration 50–100 μg/mL) was added, followed by incubation in a 37 °C water bath for 30 min. Finally, PI staining solution (final concentration 50 μg/mL) was added to the system, and the cells were incubated at room temperature for 15–30 min before flow cytometry analysis to evaluate the cells and identify their stages. To ensure reliability, cell cycle detection requires at least 10000 cells in each sample.

4.9. Wound Assay

After thawing, ESCs were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 10⁶ cells/mL and cultured in a 37 °C, 5% CO₂ incubator. Upon reaching complete monolayer adherence, straight lines were scratched vertically to the bottom of the plate using a sterile 1 mL pipette tip. The wells were then gently washed 2–3 times with DPBS to remove detached cells and debris. Finally, the medium was replaced with a serum-free medium to minimise the effects of proliferation on cell migration. After scratching, images were captured every 24 h to document the wound’s width. The relative scratch width was defined as the ratio of the scratch width at different time points to the initial scratch width. Wound width was quantified using the Image-Pro Plus image processing and analysis tools (Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD, USA).

4.10. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 17.0; SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL, USA). Each experiment was conducted a minimum of three times, and the data were expressed as the mean ± SD. Student's t-tests were used for comparisons between two independent groups. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the results of this study indicate that ESR1 plays a significant role in sheep endometrial growth and development. Interference with ESR1 in ESC led to changes in cell proliferation, apoptosis, G0/G1 phase arrest, related gene expression, and alterations in cell migration. Based on the expression levels of ESR1 in the endometrium of sheep with different reproductive abilities, we speculated that it might be associated with a high reproductive ability in sheep; however, further research is required to confirm this.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Kang Li and Xiaoxiao Gao; formal analysis, Kang Li and Zhibo Wang; validation, Kang Li; writing—original draft preparation, Kang Li; resources, Xiaoxiao Gao and Xiaodan Li; writing—review, and editing, Xiaodan Li; Investigation, Dongxu Li and Jiahe Guo; Funding acquisition, Feng Wang and Tianlong Guo; supervision, Feng Wang and Tianlong Guo.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 32261143734; Earmarked Fund for China Agriculture Research System, grant number CARS-38.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All animal studies were conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals formulated by Nanjing Agricultural University (SYXK 2011-0036).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Wang Feng's team members provided significant help and guidance during the experiment and writing of this article. The High-Performance Computing Platform of the Bioinformatics Center of Nanjing Agricultural University provided support for data analysis. The authors thank all the reviewers. We would like to thank Editage (

www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Osz, J.; Brélivet, Y.; Peluso-Iltis, C.; Cura, V.; Eiler, S.; Ruff, M.; Bourguet, W.; Rochel moras, N.; Moras, D. Structural basis for a molecular allosteric control mechanism of cofactor binding to nuclear receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, E588–E594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couse, J.F.; Lindzey, J.; Grandien, K.; Gustafsson, J.A.; Korach, K.S. Tissue distribution and quantitative analysis of estrogen receptor-alpha (ERalpha) and estrogen receptor-beta (ERbeta) messenger ribonucleic acid in the wild-type and ERalpha-knockout mouse. Endocrinology 1997, 138, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, K.; Huang, Z.Y.; Xu, X.L.; Li, J.; Fu, X.W.; Deng, S.L. Estrogen Receptor Function: Impact on the Human Endometrium. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022, 13, 827724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. A. McCracken, W.S., W.C. Okulicz. Hormone receptor control of pulsatile secretion of PGF2α from the ovine uterus during luteolysis and its abrogation in early pregnancy. animal reproduction science 1984, 7, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Byers, M.J.; Zangl, A.; Phernetton, T.M.; Lopez, G.; Chen, D.B.; Magness, R.R. Endothelial vasodilator production by ovine uterine and systemic arteries: ovarian steroid and pregnancy control of ERalpha and ERbeta levels. J Physiol 2005, 565, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, M.B.; Jobe, S.O.; Ramadoss, J.; Magness, R.R. Estrogen receptor-α and estrogen receptor-β in the uterine vascular endothelium during pregnancy: functional implications for regulating uterine blood flow. Semin Reprod Med 2012, 30, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couse, J.F.; Korach, K.S. Contrasting phenotypes in reproductive tissues of female estrogen receptor null mice. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2001, 948, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couse, J.F.; Korach, K.S. Estrogen receptor null mice: what have we learned and where will they lead us? Endocr Rev 1999, 20, 358–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, R.A. Estrogen in the adult male reproductive tract: a review. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2003, 1, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlevliet, J.M.; Pearl, C.A.; Hess, M.F.; Famula, T.R.; Roser, J.F. Immunolocalization of estrogen and androgen receptors and steroid concentrations in the stallion epididymis. Theriogenology 2006, 66, 755–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, R.A.; Bunick, D.; Bahr, J. Oestrogen, its receptors and function in the male reproductive tract - a review. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2001, 178, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, W.; Xiao, L.; Duan, H.; Jiang, Y.; Lv, J.; Ding, Z.; Hu, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y. Androgen receptor, aromatase, oestrogen receptor alpha/beta and G protein-coupled receptor 30 expression in the testes and epididymides of adult sheep. Reprod Domest Anim 2020, 55, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winuthayanon, W.; Lierz, S.L.; Delarosa, K.C.; Sampels, S.R.; Donoghue, L.J.; Hewitt, S.C.; Korach, K.S. Juxtacrine Activity of Estrogen Receptor α in Uterine Stromal Cells is Necessary for Estrogen-Induced Epithelial Cell Proliferation. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 8377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawar, S.; Laws, M.J.; Bagchi, I.C.; Bagchi, M.K. Uterine Epithelial Estrogen Receptor-α Controls Decidualization via a Paracrine Mechanism. Mol Endocrinol 2015, 29, 1362–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.M.; Gray, C.A.; Joyce, M.M.; Stewart, M.D.; Bazer, F.W.; Spencer, T.E. Neonatal ovine uterine development involves alterations in expression of receptors for estrogen, progesterone, and prolactin. Biol Reprod 2000, 63, 1192–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, K.A.; Rodriguez, K.F.; Hewitt, S.C.; Janardhan, K.S.; Young, S.L.; Korach, K.S. Role of estrogen receptor signaling required for endometriosis-like lesion establishment in a mouse model. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 3960–3971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wang, Z. Targeting the "Undruggable": Small-Molecule Inhibitors of Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen (PCNA) in the Spotlight in Cancer Therapy. J Med Chem 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, A.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Liu, F.; Song, W.; Zheng, J. Anti-Müllerian hormone regulates ovarian granulosa cell growth in PCOS rats through SMAD4. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Y.; Meng, Y.; Yan, B.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, X. The biochemical pathways of apoptotic, necroptotic, pyroptotic, and ferroptotic cell death. Mol Cell 2024, 84, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldin, M.P.; Varfolomeev, E.E.; Pancer, Z.; Mett, I.L.; Camonis, J.H.; Wallach, D. A Novel Protein That Interacts with the Death Domain of Fas/APO1 Contains a Sequence Motif Related to the Death Domain (∗). Journal of Biological Chemistry 1995, 270, 7795–7798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pihán, P.; Carreras-Sureda, A.; Hetz, C. BCL-2 family: integrating stress responses at the ER to control cell demise. Cell Death Differ 2017, 24, 1478–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czabotar, P.E.; Lessene, G.; Strasser, A.; Adams, J.M. Control of apoptosis by the BCL-2 protein family: implications for physiology and therapy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2014, 15, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.R. The Mitochondrial Pathway of Apoptosis Part II: The BCL-2 Protein Family. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, M.J.; McArthur, K.; Metcalf, D.; Lane, R.M.; Cambier, J.C.; Herold, M.J.; van Delft, M.F.; Bedoui, S.; Lessene, G.; Ritchie, M.E.; et al. Apoptotic caspases suppress mtDNA-induced STING-mediated type I IFN production. Cell 2014, 159, 1549–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, J.S.; Quarato, G.; Cloix, C.; Lopez, J.; O'Prey, J.; Pearson, M.; Chapman, J.; Sesaki, H.; Carlin, L.M.; Passos, J.F.; et al. Mitochondrial inner membrane permeabilisation enables mtDNA release during apoptosis. Embo j 2018, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. Cell Cycle Progression and Synchronization: An Overview. Methods Mol Biol 2022, 2579, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashir, T.; Pagano, M. Cdk1: the dominant sibling of Cdk2. Nat Cell Biol 2005, 7, 779–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kastenhuber, E.R.; Lowe, S.W. Putting p53 in Context. Cell 2017, 170, 1062–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manohar, S.; Estrada, M.E.; Uliana, F.; Vuina, K.; Alvarez, P.M.; de Bruin, R.A.M.; Neurohr, G.E. Genome homeostasis defects drive enlarged cells into senescence. Mol Cell 2023, 83, 4032–4046.e4036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpa, E.; Mayor, R. Collective cell migration in development. J Cell Biol 2016, 212, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, Q.; Liang, Y.; Xu, X.; Halbiyat, Z.; Wang, X.; Cheng, J.; Liu, J.; Huang, T.; Peng, Z.; Wang, L.; et al. Sodium alginate hydrogel integrated with type III collagen and mesenchymal stem cell to promote endometrium regeneration and fertility restoration. Int J Biol Macromol 2023, 253, 127314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashiri, A.; Halper, K.I.; Orvieto, R. Recurrent Implantation Failure-update overview on etiology, diagnosis, treatment and future directions. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2018, 16, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Li, F.; Wang, F.; Zhang, G.; Pang, J.; Ren, C.; Zhang, T.; Yang, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y. Genome-wide differential expression profiling of mRNAs and lncRNAs associated with prolificacy in Hu sheep. Biosci Rep 2018, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.X.; Li, X.H.; Zhang, Q.F.; Zhu, M.; Guo, Y.X.; Deng, K.P.; Zhang, G.M.; Wang, F. Effects of l-arginine on endometrial microvessel density in nutrient-restricted Hu sheep. Theriogenology 2018, 119, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, X.; Liu, J.; Ma, X.; Zhou, Z.; Song, Y.; Cao, B. miR-26a promoted endometrial epithelium cells (EECs) proliferation and induced stromal cells (ESCs) apoptosis via the PTEN-PI3K/AKT pathway in dairy goats. J Cell Physiol 2018, 233, 4688–4706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, K.; Hennes, A.; Vriens, J. Isolation of Mouse Endometrial Epithelial and Stromal Cells for In Vitro Decidualization. J Vis Exp 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayako MASUDA, N.K. , Kazuhiko NAKABAYASHI, et al. An improved method for isolation of epithelial and stromal cells from the human endometrium. Journal of Reproduction and Development 2016, 62, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Yuan, X.; Chen, L.; Wang, T.; Wang, Z.; Sun, G.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Liu, G. Histamine Induces Bovine Rumen Epithelial Cell Inflammatory Response via NF-κB Pathway. Cell Physiol Biochem 2017, 42, 1109–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.X.; Nie, H.T.; Sun, L.W.; Zhang, G.M.; Deng, K.P.; Fan, Y.X.; Wang, F. Effects of diet and arginine treatment during the luteal phase on ovarian NO/PGC-1alpha signaling in ewes. Theriogenology 2017, 96, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Short Biography of Authors

The author Kang Li is an employee of Inner Mongolia Academy of Agricultural & Animal Husbandry Sciences (affiliation 2 to which the author belongs) and began pursuing a doctoral degree at Jiangsu Livestock Embryo Engineering Laboratory, Nanjing Agricultural University (affiliation 3 to which the author belongs) in 2020, and the supervisor is Professor Feng Wang.

Nanjing Agricultural University and Sanya City (Hainan Province, China) jointly established the Sanya Research Institute in 2021, and Professor Feng Wang was selected to work there. The cell culture and molecular biology experiments involved in this article were conducted on the experimental platforms of Sanya Research Institute (affiliation 1 to which the author belongs) and Jiangsu Livestock Embryo Engineering Laboratory. The experimental research funding is provided by Feng Wang, affiliated with Sanya Research Institute of Nanjing Agricultural University and Jiangsu Livestock Embryo Engineering Laboratory of Nanjing Agricultural University, and Tianlong Guo, affiliated with Inner Mongolia Academy of Agricultural & Animal Husbandry Sciences.

The contributions made by authors Zhibo Wang, Dongxu Li, and Jiahe Guo during the research process of this article have been stated in the ‘author contributions’ section. They are also doctoral students of Professor Feng Wang, conducting scientific research at Jiangsu Livestock Embryo Engineering Laboratory and Sanya Research Institute. Author Xiaoxiao Gao belongs to the College of Animal Science and Technology, Qingdao Agricultural University. In this study, some ESC cells were obtained with his assistance.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).