Submitted:

23 September 2025

Posted:

23 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

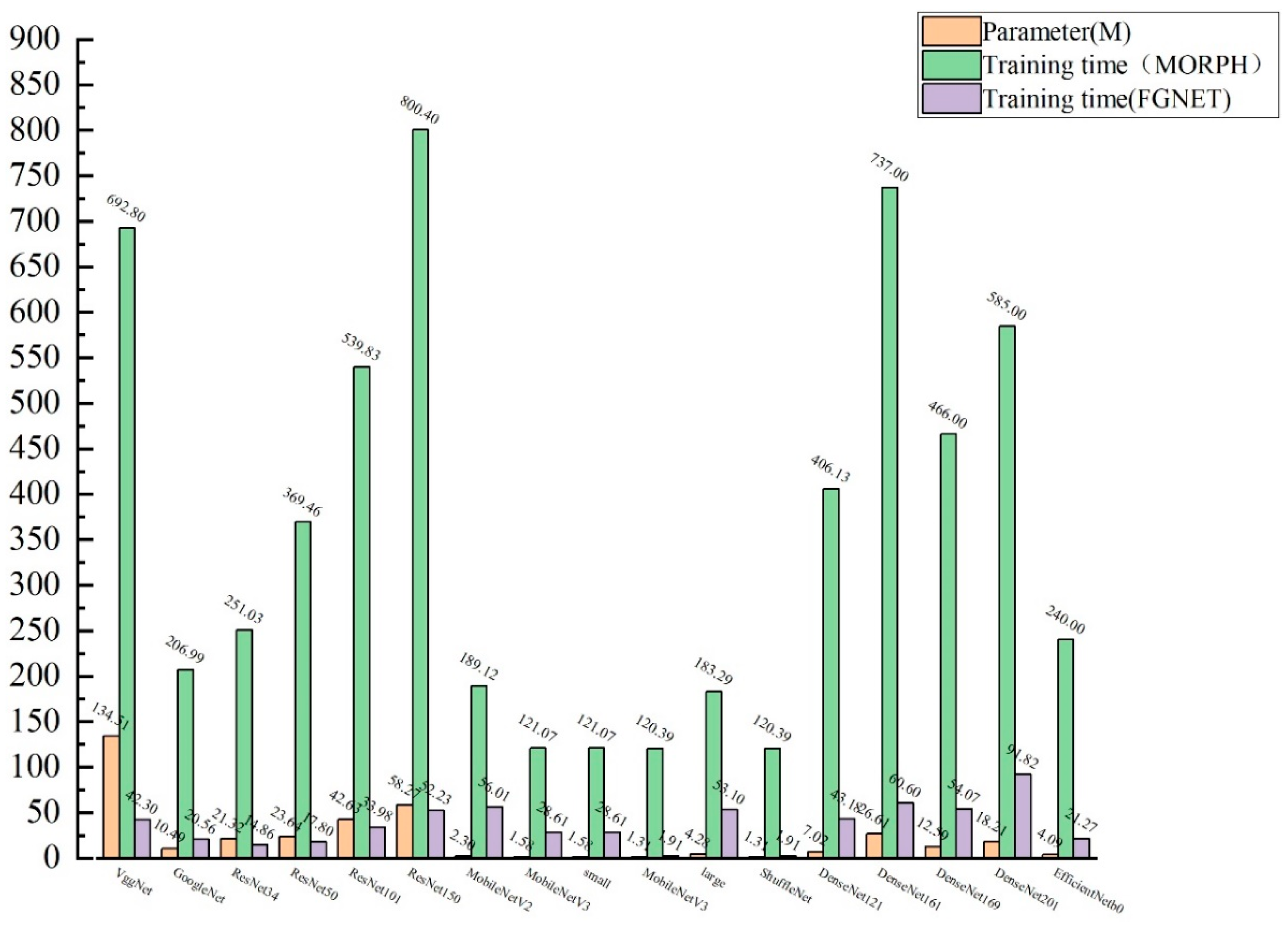

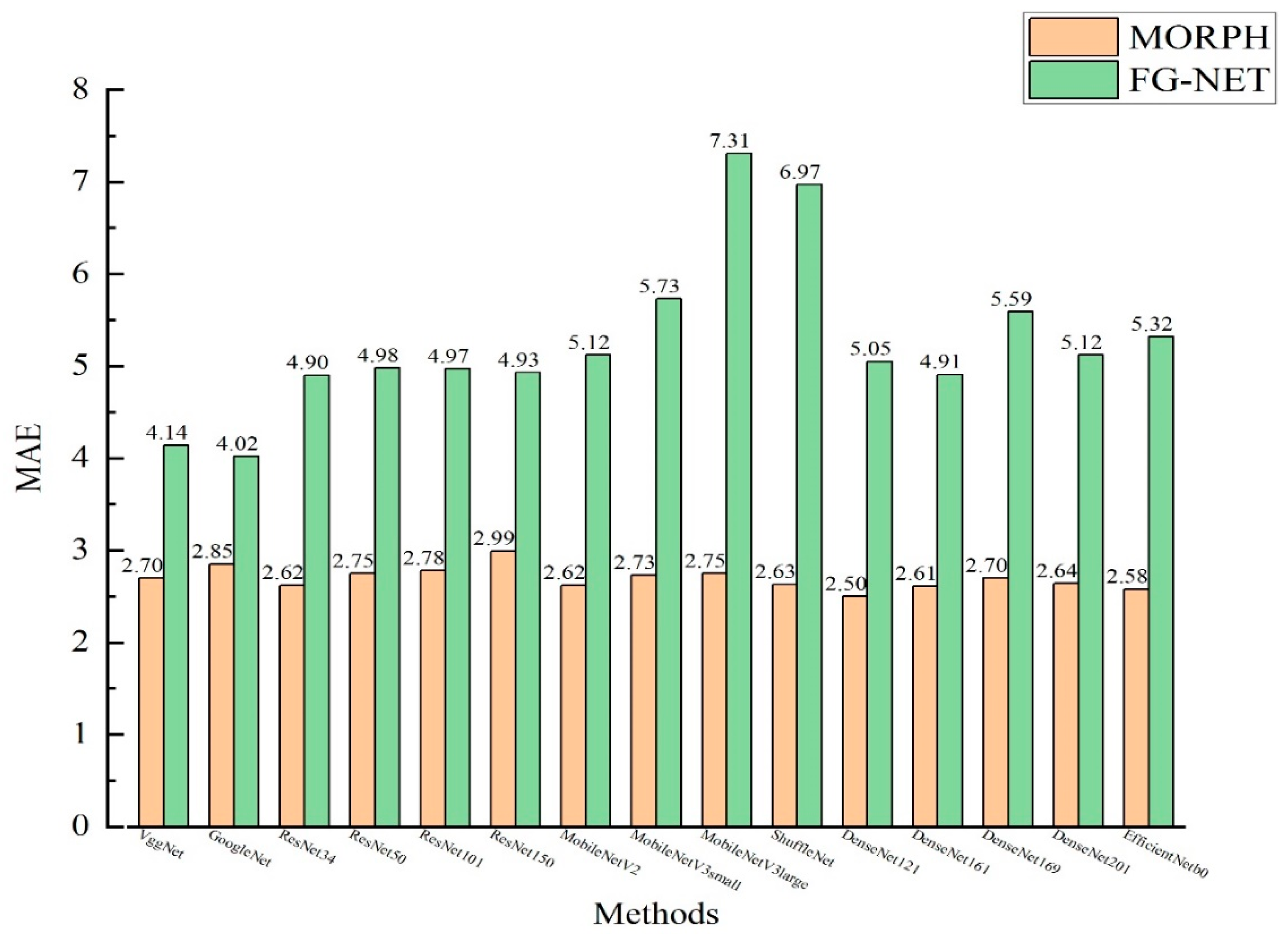

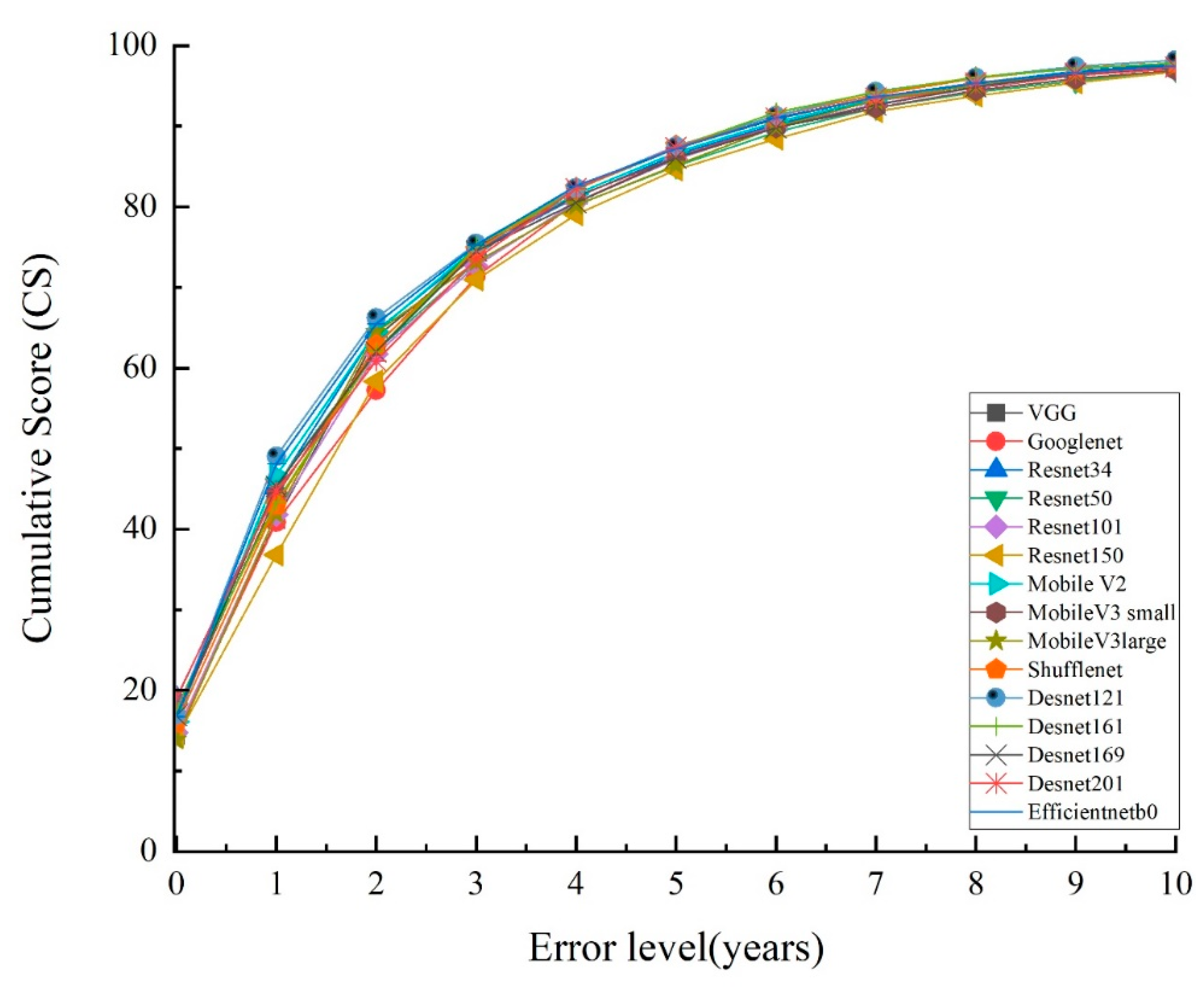

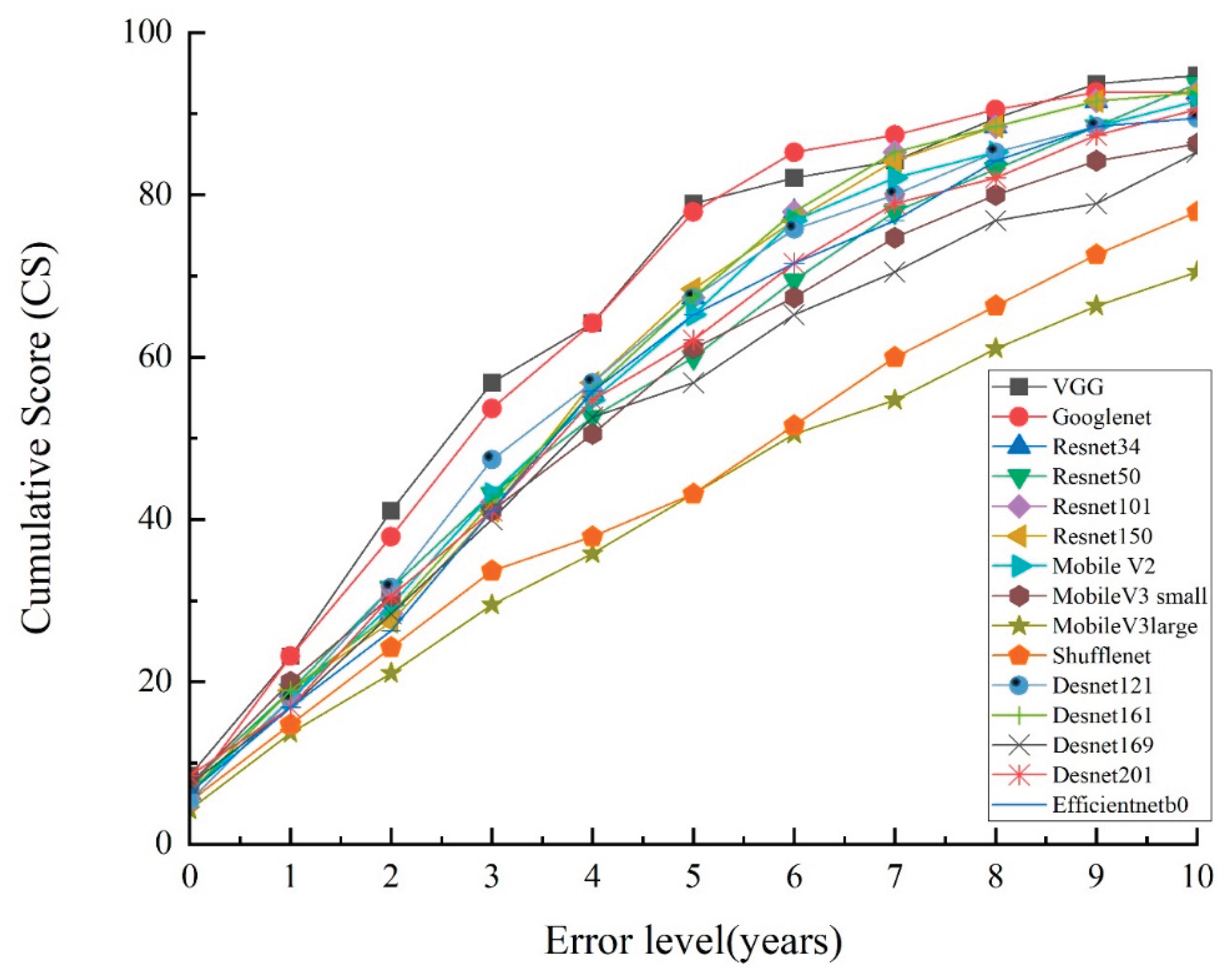

Facial age recognition, as an important research in the field of computer vision, has broad application prospects in areas such as security monitoring and human-computer interaction. This study aims to compare the performance of classic (VGGNet, GoogleNet, DenseNet) and lightweight (MobileNet, EfficientNet) deep learning frameworks in facial age recognition, providing a scientific basis for model selection. The research is based on the public datasets MORPH (large-scale) and FG-NET (small-scale), comprehensively evaluating from dimensions of accuracy, model efficiency (parameter scale, training time), and resource consumption. Experimental results show that there is no significant linear relationship between model parameters, accuracy, and training time. DenseNet121 achieves the best accuracy with MAE is 2.50 on MORPH, suitable for high-precision requirements; GoogleNet performs best on FG-NET with MAE is 4.02; MobileNet and other lightweight models are suitable for mobile devices but have slightly lower accuracy than large models. This study quantifies the adaptation characteristics of different models, providing core evidence for the selection of scenario-based face age recognition models, facilitating the practical application of this technology.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- The mainstream CNN architectures were systematically compared, filling the gap in horizontal evaluation across multiple models. The experimental results show that the performance of the models is closely related to the dataset size and structural design. The number of parameters is not linearly correlated with accuracy. Feature reuse mechanisms (such as dense connections) and multi-scale feature fusion (such as Inception modules) have greater advantages in specific scenarios.

- Combining model efficiency metrics (parameter size, training time) with accuracy metrics (MAE, CS) for the first time, a comprehensive evaluation system was established. This provides clear selection criteria for re-source-constrained scenarios such as mobile device deployment.

- Revealed the pattern of model structure adaptation to dataset characteristics, quantified the impact of sample size on model performance, and provided a new direction for cross-dataset generalization research.

- This study systematically verified the practicality of lightweight models in age recognition, providing theo-retical support for the design of real-time age recognition systems.

2. Related Work

3. Introduction to Classic Models

- 1)

- VGG [37] was proposed by the University of Oxford and performed exceptionally well in the ImageNet competition in 2014. Its core design involves uniformly using 3x3 convolution stacks instead of large-sized convolu-tions, combined with 2x2 pooling layers, to achieve deepening through a modular structure. Although it has a large number of parameters, its structure is simple and can stably capture multi-scale features, making it a classic benchmark model in the field of deep learning.

- 2)

- GoogLeNet [38] was the champion in the ImageNet classification task in 2014. Its core innovation was the Inception module, which used parallel multi-scale convolutions (1x1, 3x3, 5x5) and pooling, and concatenated the outputs to fuse multi-scale information; by using 1x1 convolutions to reduce dimensions and introduce auxiliary classifiers to alleviate gradient vanishing, it abandoned fully connected layers and replaced them with global aver-age pooling, significantly reducing parameters and overfitting risks.

- 3)

- ResNet [39] is a milestone model proposed in 2015, with the core being residual connections: through re-sidual blocks, allowing gradients to propagate directly, solving the problem of gradient vanishing and performance decline in deep models. The modular design (BasicBlock, Bottleneck) increases depth while controlling the number of parameters, has extremely strong generalization ability, and has become the standard backbone model for com-puter vision tasks.

- 4)

- MobileNet [40] is a lightweight model designed by Google for mobile devices, with the core being depth-wise separable convolutions (depthwise convolutions capture spatial features + 1x1 pointwise convolutions for channel fusion), combined with the width multiplier α to flexibly scale the number of channels, significantly re-ducing parameters and computational costs while maintaining accuracy, achieving a balance between efficiency and performance.

- 5)

- ShuffleNet [41] is a lightweight model proposed by Megvii, with the core being group convolutions fol-lowed by channel shuffling to break the information barriers between groups; by dynamically adjusting the model size through scaling factors, it enhances cross-channel fusion while retaining the advantages of lightweight design, adapting to different scenarios with limited computing resources.

- 6)

- DenseNet [42] innovates in dense connections, where each layer is directly connected to all previous layers, achieving maximum feature reuse through channel concatenation, promoting information and gradient flow, effec-tively alleviating gradient vanishing, and significantly reducing parameters while improving performance, suitable for training deep models.

- 7)

- EfficientNet [43] achieves breakthroughs in accuracy and efficiency through systematic design: adjusting the model depth, width, and input resolution in a fixed proportion, combining the MBConv module (inverted bottle-neck structure + depthwise convolutions) and the SE attention mechanism, enhancing feature expression without significantly increasing computational costs, becoming a benchmark for efficient model design.

4. Experiments

4.1. Datasets

4.2. Image Preprocessing

4.3. Experimental Settings

4.4. Evaluation Criteria

4.5. Models Training and Experimental results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bekhouche, S.E.; Benlamoudi, A.; Dornaika, F.; Telli, H.; Bounab, Y. Facial age estimation using multi-stage deep mod-els. Electronics 2024, 13, 3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumbadkar, R.; Kamble, V.; Parate, M. Development of facial age estimation using modified distance-based regressed CNN model. Traitement du Signal 2025, 42( 2), 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, Z. H.; Shaker, S.H. Prediction of human age based on face image using deep convolutional neural network.AIP Con-ference Proceedings, 2024, 3009(1):11. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shou, Y.; Ai, W.; et al. GroupFace: imbalanced age estimation based on multi-hop attention graph convolutional network and group-aware margin optimization. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2025, 20, 605–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Qiu, M.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Enhancing facial age estimation with local and global multi-attention mechanisms. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2025, 189, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbes, A.; Ouarda, W.; Ayed, Y.B. Age-API: are landmarks-based features still distinctive for invariant facial age recognition? Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 67599–67625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang,H. Y.;Zhang,Y.;Geng,X.Recurrent age estimation.Pattern Recognition Letter. 2019, 125, 271–277.

- Geng, X.; Zhou, Z.H.; Smith-Miles, K. Automatic age estimation based on facial aging patterns. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2007, 29, 2234–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Geng, X.; Chen, F.Y. Practical age estimation using deep label distribution learning. Frontiers of Computer Science. 2021, 15(3), 73–78. [CrossRef]

- Babu, A.A.; Sudhavani, G.; Madhav, P.V.; Sadharmasasta, P.; Chowdary, K.U.; Balaji, T.; Jaya, N. Deep learning centered methodology for age guesstimate of facial images. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Information Technology. 2024, 102, 2568–2572. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Yin, S.; Cao, L. Age-invariant face recognition based on identity-age shared features.The Visual Computer, 2024, 40(8):5465-5474. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Mu, G.; Guo, G. A study on apparent age estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Int. Conf. Comput. Vis. Workshop, Santiago, Chile, 267–273., 07 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, B.B.; Xing, C.; Xie, C.W.; Wu, J.; Geng, X. Deep label distribution learning with label ambiguity. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing, 2017, 26, 2825–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Y.; Lin, J.; Zhou, L.; et al. Facial age recognition based on deep manifold learning. Mathematical Biosciences & Engineering. 2024, 21, 4485–4500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit., Las Vegas, NV, USA,770–778., 27 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, B,; Li, L.; Hu,X.,et al.DEFOG: Deep Learning with attention mechanism enabled cross-age face recognition.Tsinghua Science and Technology, 2025, 30(3):1342-1358. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zou, Y.; Kuang, H.; Ma, X. Face Image Age estimation based on data augmentation and lightweight convolutional neural network. Symmetry 2020, 12, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruleba, I.; Viriri, S. Deep learning for age estimation using efficientnet. In Advances in Computational Intelligence, 1st ed.; Rojas, I., Joya, G., Català, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021, 12861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Y.; Sheng, W. An optimized algorithm for facial age recognition based on label adaptation. Computer Engineering. 2024, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Miles, K.; Geng, X. Revisiting facial age estimation with new insights from instance space analysis. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2022, 44, 2689–2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.K.; Nain, N. Review: Single attribute and multi attribute facial gender and age estimation. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 1289–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.H.; Vitoria Lobo, N. Age classification from facial images. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 1999, 74, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aakash, S.; Kumar, S.V. A hybrid transformer–sequencer approach for age and gender classification from in-wild facial images. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 1149–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.; Mu, G.; Fu, Y.; Huang, T.S. Human age estimation using bio-inspired features. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit., Miami, FL, USA,112–119., 20 June 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lanitis, A.; Taylor, C.J.; Cootes, T.F. Toward automatic simulation of aging effects on face images. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2002, 24, 442–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Wang, D.; Zhang, K.; et al. Age estimation from facial images based on Gabor feature fusion and the CIASO-SA al-gorithm. CAAI Transactions on Intelligence Technology. 2023, 8, 518–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo,G.; Mu,G.; Fu,Y. ; Huang,T. S. Human age estimation using bio-inspired features,In 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Florida, Miami, 20 -25 June,2009, 112–119. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. Y.; Sheng, W. S.; Zeng Y., Z. Face age recognition algorithm based on label distribution learning, Journal of Jiangsu University. 2023,44(02), 180–185. [CrossRef]

- An, W.X.; Wu, G.S. Hybrid spatial-chanel attention mechanism for cross-age face recognition. Electronics 2024, 13(7), 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muliawan, N.H.; Angky, E.V.; Prasetyo, S.Y. Age estimation through facial images using deep CNN pretrained model and particle swarm optimization. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 426, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.H.; Luo, Y.T.; Tan, Z.C.; et al. Deep domain-invariant learning for facial age estimation. Neurocomputing 2023, 534, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, Z.H.; Shaker, S.H. Prediction of human age based on face image using deep convolutional neural network. AIP Conference Proceedings 2024, 3009(1), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naaz, S.; Pandey, H.; Lakshmi, C. Deep Learning based age and gender detection using facial images. In: 2024 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communication and Applied Informatics (ACCAI). 0 [2025-09-11]. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Liu, J.; Wei, W. Mixture of deep models for facial age estimation. Information Sciences,2024,679. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Ji, Q.; Shi, H.; et al. Spatial correlation guided cross scale feature fusion for age and gender estimation. Scientific Reports 2025, 15(1). [CrossRef]

- Liu,X.; Qiu, M.; Zhang, Z.;et al.Enhancing facial age estimation with local and global multi-attention mecha-nisms.Pattern Recognition Letters, 2025, 189(000),71-77. [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional models for large-scale image recognition. In Proceedings of the Int. Conf. Learn. Representations, Banff, Canada, 14 April 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; et al. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Com-puter Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA,1–9., 07 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; et al. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, USA, 770–778., 26-30 June 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; et al. MobileNets: Efficient convolutional neural models for mobile vision applica-tions. In Proc. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition,Hawaii Convention Center, USA, 21 - 26 July 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, X.; Lin, M.; et al. ShuffleNet: An extremely efficient convolutional neural network for mobile de-vices. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Hawaii Convention Cen-ter, USA, 21 - 26 July 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Laurens, V.D.M.; et al. Densely connected convolutional models. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Las Vegas, USA, 26-30 June 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q.V. EfficientNet: rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural models.Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, California, USA, 9-15 June, 2019, 6105-6114. [CrossRef]

- FG-NET Database. Available online: https://yanweifu.github.io/FG_NET_data/index.html (accessed on 04 January 2020).

- MORPH Database. Available online: https://ebill.uncw.edu/C20231_ustores/web/store_main.jsp?STOREID=4 (accessed on 17 May 2019).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).