Submitted:

23 September 2025

Posted:

23 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

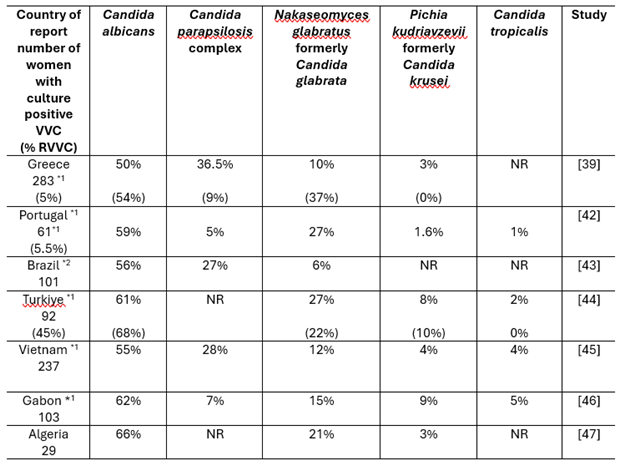

2. The Etiological Agents of VVC

3. The Role of Inflammation in the Host Response

3.1. Early Steps in Infection

3.2. Internalisation by Macrophages and Subsequent Escape

3.3. The Influx of Neutrophils

3.4. The Role of Adaptive Immunity

3.5. VVC as an Immunopathology

3.6. Opportunities to Mitigate Against Immunopathology

4. The Impact of Biofilm Formation in VVC

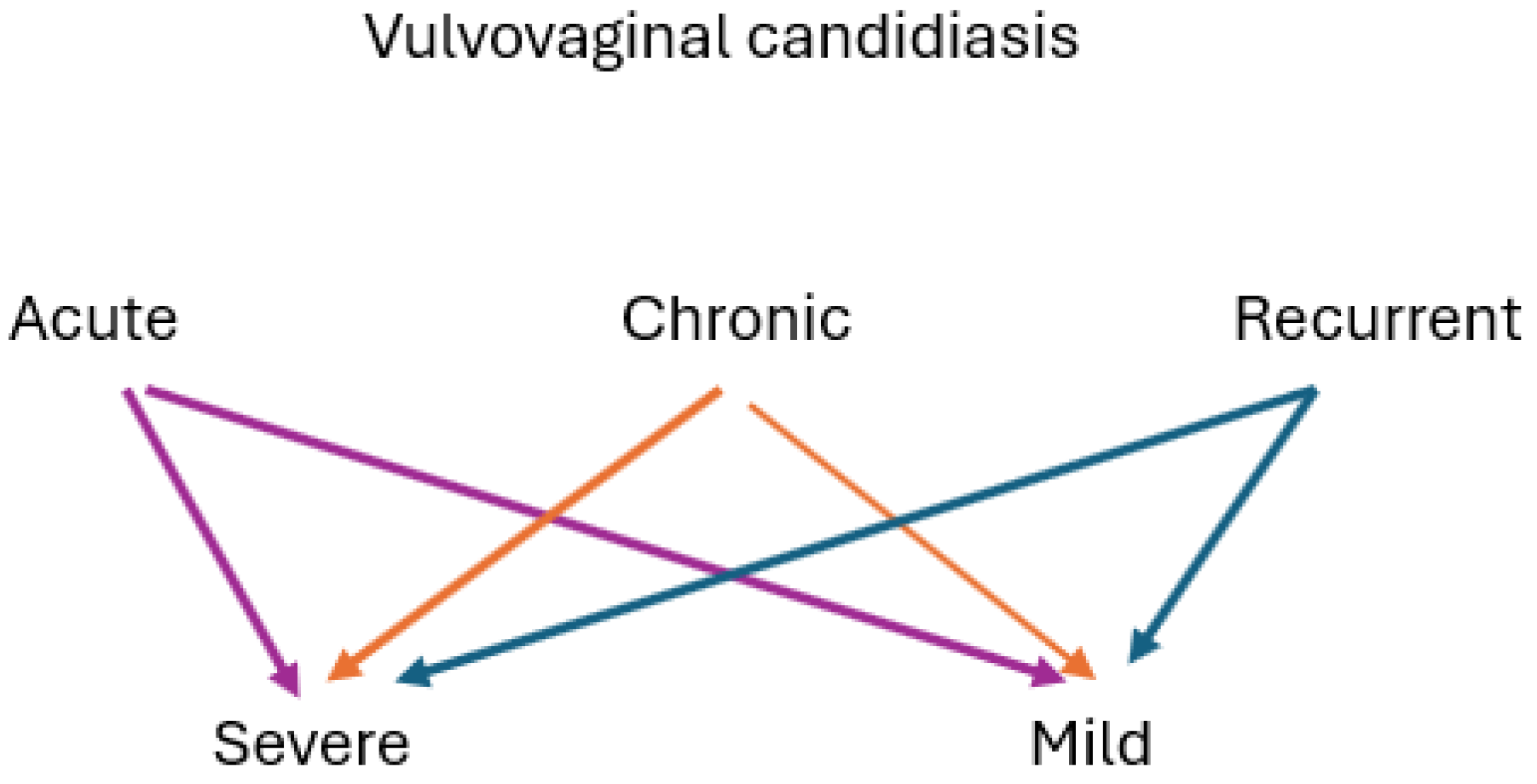

5. Clinical Management of VVC

5.1. Initial Evaluation

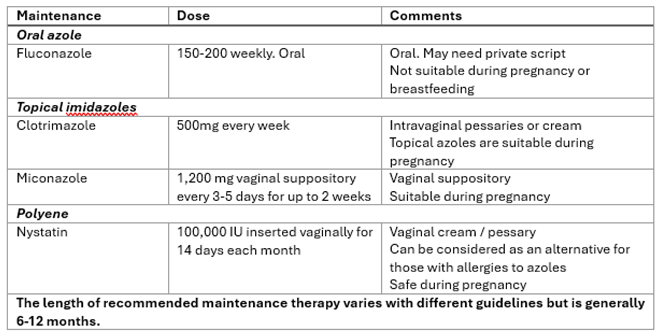

5.2. Management of RVVC

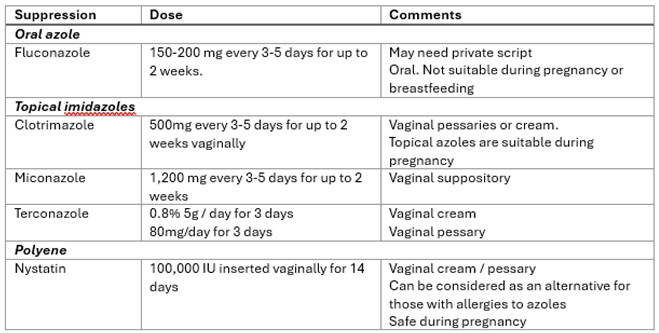

5.3. Antifungal Agents Used in VVC

5.4. New Drugs on the Horizon

5.5. Management of VVC in Challenging Conditions

- Pregnancy

- b. Diabetes

- c. Immunocompromise

- d. Fluconazole and other azole resistance

- e. Co-existing infection with bacterial vaginosis

5.6. Complementary and Alternative Therapies

6. The Influence of Vaginal Microbiota on Candidiasis Outcomes

6.1. Intestinal Carriage of Candida spp.

6.2. The Importance of Community State Types

6.3. The Use of Probiotics to Improve Vaginal Health

6.4. Efforts to Manipulate the Local Vaginal Microbiota

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BV | bacterial vaginosis |

| CAM | complementary and alternative medicine |

| CST | community state types |

| GBS | Group B streptococcal |

| GP | General Practioner |

| NAC | non-albicans Candida |

| SCFA | short chain fatty acids |

| RVVC | recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis |

| VVC | vulvovaginal candidiasis |

References

- Sobel, J.D. Vulvovaginal Candidosis. Lancet 2007, 369, 1961–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MSHC. Candidiasis (vulvovaginal) Treatment Guidelines. Melbourne Sexual Health Centre Guidelines. 2021. Available online: https://www.mshc.org.au/health-professionals/treatment-guidelines/candidiasis-vulvovaginal-treatment-guidelines (accessed on 4th June 2025).

- Sobel, J.D.; Wiesenfeld, H.C.; Martens, M.; Danna, P.; Hooton, T.M. , Rompalo, A.; Sperling, M.; Livengood, C. 3rd.; Horowitz, B.; Von Thron, J.; et al. Maintenance Fluconazole Therapy for Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 876–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrström, S.; Kornfeld, D.; Rylander, E. Perceived Stress in Women with Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2007, 28, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aballéa, S.; Guelfucci, F.; Wagner, J.; Khemiri, A.; Dietz, J.P.; Sobel, J.; Toumi, M. Subjective Health Status and Health-related Quality of Life Among Women with Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidosis (RVVC) in Europe and the USA. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2013, 11, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, C.J.; Pirotta, M.; Myers, P. Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine in Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis-Results of a Practitioner Survey. Complement. Ther. Med. 2012, 20, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahedpoor, Z.; Abastabar, M.; Sehat, M. Vaginal and Oral Use of Probiotics as Adjunctive Therapy to Fluconazole in Patients with Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: A Clinical Trial on Iranian Women. Curr. Med. Mycol. 2021, 7, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foxman, B.; Muraglia, R.; Dietz, J.P.; Sobel, J.D.; Wagner, J. Prevalence of Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis in 5 European Countries and the United States: Results from an Internet Panel Survey. J. Low. Genit. Tract. Dis. 2013, 17, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denning, D.W.; Kneale, M.; Sobel, J.D.; Rautemaa-Richardson, R. Global Burden of Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: A Systematic Review. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, e339–e347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willems, H.M.E.; Ahmed, S.S.; Liu, J.; Xu, Z.; Peters, B.M. Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: A Current Understanding and Burning Questions. J. Fungi (Basel). 2020, 6, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vazquez, J.A.; Sobel, J.D.; Demitriou, R.; Vaishampayan, J.; Lynch, M.; Zervos, M.J. Karyotyping of Candida albicans Isolates Obtained Longitudinally in Women with Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis. J. Infect. Dis. 1994, 170, 1566–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Cerdeira, C.; Martínez-Herrera, E.; Carnero-Gregorio, M.; López-Barcenas, A.; Fabbrocini, G.; Fida, M.; El-Samahy, M.; González-Cespón, J.L. Pathogenesis and Clinical Relevance of Candida Biofilms in Vulvovaginal Candidiasis. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 544480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchaim, D.; Lemanek, L.; Bheemreddy, S.; Kaye, K.S.; Sobel, J.D. Fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans Vulvovaginitis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 120, 1407–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, J.A.; Seidu, L. Chronic Vulvovaginal Candida Hypersensitivity: An Underrecognized and Undertreated Disorder by Allergists. Allergy Rhinol. (Providence). 2015, 6, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidel, P.L. Jr; Barousse, M.; Espinosa, T.; Ficarra, M.; Sturtevant, J.; Martin, D.H.; Quayle, A.J.; Dunlap, K. An Intravaginal Live Candida Challenge in Humans Leads to New Hypotheses for the Immunopathogenesis of Vulvovaginal Candidiasis. Infect. Immun. 2004, 72, 2939–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobel, J.D.; Faro, S.; Force, R.W.; Foxman, B.; Ledger, W.J.; Nyirjesy, P.R.; Reed, B.D.; Summers, P.R. Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: Epidemiologic, Diagnostic, and Therapeutic Considerations. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1998, 178, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyirjesy, P.; Sobel, J.D. Advances in Diagnosing Vaginitis: Development of a New Algorithm. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2005, 7, 458–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin Lopez, J.E. Candidiasis (vulvovaginal). BMJ Clin. Evid. 2015, 16, 0815. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Zhang, X.; Li, Q.; Zhong, W.; Zou, H. The Increasing Trend of Triazole-Resistant Candida from Vulvovaginal Candidiasis. Infect. Drug Resist. 2024, 17, 4301–4310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, K.; Ilkit, M.; Ates. , A.; Turac-Bicer, A.; Demirhindi, H. Performance of Chromogenic Candida agar and CHROMagar Candida in Recovery and Presumptive Identification of Monofungal and Polyfungal Vaginal Isolates. Med. Mycol. 2010, 48, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratner, J.C.; Wilson, J.; Roberts, K.; Armitage, C.; Barton, R.C. Increasing Rate of non-Candida albicans Yeasts and Fluconazole Resistance in Yeast Isolates from Women with Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis in Leeds, United Kingdom. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2025, 101, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, D.G.; Dekle, C.; Litaker, M.S. Women's Use of Over-the-counter Antifungal Medications for Gynecologic Symptoms. J. Fam. Pract. 1996, 42, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fisher, M.C.; Hawkins, N.J.; Sanglard, D.; Gurr, S.J. Worldwide Emergence of Resistance to Antifungal Drugs Challenges Human Health and Food Security. Science 2018, 360, 739–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, J.; Krysan, D.J. Drug Resistance and Tolerance in Fungi. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 319–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyirjesy, P.; Brookhart, C.; Lazenby, G.; Schwebke, J.; Sobel, J.D. Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: A Review of the Evidence for the 2021 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 74 (Suppl_2), S162–S168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarathna, D.H.; Lukey, J.; Coppin, J.D.; Jinadatha, C. Diagnostic Performance of DNA Probe-based and PCR-based Molecular Vaginitis Testing. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0162823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillis, R.A.; Parker, R.L.; Ackerman, R.; Ackerman, J.; Young, S.; Weissfeld, A.; Trevino, E.; Nachamkin, I.; Crane, L.; Brown, J.; et al. Clinical Evaluation of a New Molecular Test for the Detection of Organisms Causing Vaginitis and Vaginosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2023, 61, e0174822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morovati, H.; Kord, M.; Ahmadikia, K.; Eslami, S.; Hemmatzadeh, M.; Kurdestani, K.M.; Khademi, M.; Darabian, S. A Comprehensive Review of Identification Methods for Pathogenic Yeasts: Challenges and Approaches. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2023, 12, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharmann, U.; Kirchhoff, L.; Chapot, V.L.S.; Dziobaka, J.; Verhasselt, H.L.; Stauf, R.; Buer, J.; Steinmann, J.; Rath, P.M. Comparison of Four Commercially Available Chromogenic Media to Identify Candida albicans and Other Medically Relevant Candida species. Mycoses 2020, 63, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, M.N.; Ortiz, S.O.; Mello, M.M.; Oliveira Fde, M.; Severo, L.C.; Goebel, C.S. Comparison Between Four Usual Methods of Identification of Candida species. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 2015, 57, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, C.J.; Grando, D.; Fairley, C.K.; Chondros, P.; Garland, S.M.; Myers, S.P.; Pirotta, M. The Effects of Oral Garlic on Vaginal Candida Colony Counts: a Randomised Placebo Controlled Double-blind Trial. BJOG 2014, 121, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitew, A.; Abebaw, Y. Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: Species Distribution of Candida and their Antifungal Susceptibility Pattern. BMC Womens Health 2018, 18, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posteraro, B.; Martucci, R.; La Sorda, M.; Fiori, B.; Sanglard, D.; De Carolis, E.; Florio, A.R.; Fadda, G.; Sanguinetti, M. Reliability of the Vitek 2 Yeast Susceptibility Test for Detection of in vitro Resistance to Fluconazole and Voriconazole in Clinical Isolates of Candida albicans and Candida glabrata. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009, 47, 1927–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, M.G.; Cornet, M.; Hennebique, A.; Rasamoelina, T.; Caspar, Y.; Pondérand, L.; Bidart, M.; Durand, H.; Jacquet, M.; Garnaud, C.; Maubon, D. MALDI-TOF MS in a Medical Mycology Laboratory: On Stage and Backstage. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teke, L.; Barış, A.; Bayraktar, B. Comparative Evaluation of the Bruker Biotyper and Vitek MS Matrix-assisted Laser Desorption Ionization-time of Flight Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) systems for Non-albicans Candida and Uncommon Yeast Isolates. J. Microbiol. Methods 2021, 185, 106232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasani, E.; Rafat, Z.; Ashrafi, K.; Salimi, Y.; Zandi, M.; Soltani, S.; Hashemi, F.; Hashemi, S.J. Vulvovaginal Candidiasis in Iran: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis on the Epidemiology, Clinical Manifestations, Demographic Characteristics, Risk Factors, Etiologic Agents and Laboratory Diagnosis. Microb. Pathog. 2021, 154, 104802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, B.; Ferreira, C.; Alves, C.T.; Henriques, M.; Azeredo, J.; Silva, S. Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: Epidemiology, Microbiology and Risk Factors. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 42, 905–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboagye, G.; Waikhom, S.; Asiamah, E.A.; Tettey, C.O.; Mbroh, H.; Smith, C. , Osei, G.Y.; Asafo Adjei, K.; Asmah, R.H. Antifungal Susceptibility Profiles of Candida and non-albicans Species Isolated from Pregnant Women: Implications for Emerging Antimicrobial Resistance in Maternal Health. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 2, e0078725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroustali, V.; Resoulai, E.; Kanioura, L.; Siopi, M.; Meletiadis, J.; Antonopoulou, S. Epidemiology of Vulvovaginal Candidiasis in Greece: A 2-Year Single-Centre Study. Mycoses 2025, 68, e70026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshnia, F.; de Almeida Júnior, J.N.; Ilkit, M.; Lombardi, L.; Perry, A.M.; Gao, M.; Nobile, C.J.; Egger, M.; Perlin, D.S.; Zhai, B.; et al. Worldwide Emergence of Fluconazole-resistant Candida parapsilosis: Current Framework and Future Research Roadmap. Lancet Microbe 2023, 4, e470–e480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szekely, J.; Rakchang, W.; Rattanaphan, P.; Kositpantawong, N. Fluconazole and Echinocandin Resistance of Candida species in Invasive Candidiasis at a University Hospital During pre-COVID-19 and the COVID-19 Outbreak. Epidemiol. Infect. 2023, 151, e146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, Â.; Azevedo, N.; Valente, A.; Dias, M.; Gomes, A.; Nogueira-Silva, C.; Henriques, M.; Silva, S.; Gonçalves, B. Vulvovaginal Candidiasis and Asymptomatic Vaginal Colonization in Portugal: Epidemiology, Risk Factors and Antifungal Pattern. Med. Mycol. 2022, 60, myac029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trajano, D.T.M.; Melhem, M.S.C.; Takahashi, J.P.F.; Bonfietti, L.X.; de Araújo, M.R.; Corrêa, V.B.; Araújo, K.B.O.; Barnabé, V.; Fernandes, C.G. Species and Antifungal Susceptibility Profile of Agents Causing Vulvovaginal Candidiasis in a Military Population: A Cross-sectional Study. Med. Mycol. 2023, 61, myad025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakoyun, A.S.; Unal, N.; Sucu, M.; Bingöl, O.; Unal, I.; Ilkit, M. Integrating Clinical and Microbiological Expertise to Improve Vaginal Candidiasis Management. Mycopathologia 2024, 189, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anh, D.N.; Hung, D.N.; Tien, T.V.; Dinh, V.N.; Son, V.T.; Luong, N.V.; Van, N.T.; Quynh, N.T.N.; Van Tuan, N.; Tuan, L.Q.; et al. Prevalence, Species Distribution and Antifungal Susceptibility of Candida albicans Causing Vaginal Discharge Among Symptomatic Non-pregnant Women of Reproductive Age at a Tertiary Care Hospital, Vietnam. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bignoumba, M.; Onanga, R.; Kumulungui, B.S.; Kassa, R.F.K.; Ndzime, Y.M.; Moghoa, K.M.; Stubbe, D.; Becker, P. High Diversity of Yeast Species and Strains Responsible for Vulvovaginal Candidiasis in South-East Gabon. J. Mycol. Med. 2023, 33, 101354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhadj, M.; Menasria, T.; Ranque, S. MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry Identification and Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts Causing Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (VVC) in Tebessa (Northeastern Algeria). Ann. Biol. Clin. (Paris) 2024, 81, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donders, G.; Bellen, G.; Byttebier, G.; Verguts, L.; Hinoul, P.; Walckiers, R.; Stalpaert, M.; Vereecken, A.; Van Eldere, J. Individualized Decreasing-dose Maintenance Fluconazole Regimen for Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (ReCiDiF trial). Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 199, 613.e1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobel, J.D.; Vempati, Y.S. Bacterial Vaginosis and Vulvovaginal Candidiasis Pathophysiologic Interrelationship. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Y.; Lee, A.; Fischer, G. 2017. Management of Chronic Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: A Long Term Retrospective Study. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2017, 58, e188–e192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, P.G.; Kauffman, C.A.; Andes, D.R.; Clancy, C.J.; Marr, K.A.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Reboli, A.C.; Schuster, M.G.; Vazquez, J.A.; Walsh, T.J.; et al. Executive Summary: Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria-Gonçalves, P.; Rolo, J.; Gaspar, C.; Oliveira, A. S.; Pestana, P. G.; Palmeira-de-Oliveira, R.; Gonçalves, T.; Martinez-de-Oliveira, J.; Palmeira-de-Oliveira, A. Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candida spp Isolates Phenotypically Express Less Virulence Traits. Microb, Pathog. 2020, 148, 104471. [CrossRef]

- Desai, J.V. Candida albicans Hyphae: From Growth Initiation to Invasion. J. Fungi (Basel) 2018, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyes, D.L.; Richardson, J.P.; Naglik, J.R. Candida albicans-epithelial Interactions and Pathogenicity Mechanisms: Scratching the Surface. Virulence 2015, 6, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camilli, G.; Griffiths, J.S.; Ho, J.; Richardson, J.P.; Naglik, J.R. Some Like it Hot: Candida Activation of Inflammasomes. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vande Walle, L.; Lamkanfi, M. Pyroptosis. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, R568–R572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, C.G.; Koser, U.; Lewis, L.E.; Bain, J.M.; Mora-Montes, H.M.; Barker, R.N.; Gow, N.A.; Erwig, L.P. Contribution of Candida albicans Cell Wall Components to Recognition by and Escape from Murine Macrophages. Infect. Immun. 2010, 78, 1650–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickramasinghe, D.N.; Lyon, C.M.; Lee, S.; Hepworth, O.W.; Priest, E.L.; Maufrais, C.; Ryan, A.P.; Permal, E.; Sullivan, D.; McManus, B.A.; et al. Variations in Candidalysin Amino Acid Sequence Influence Toxicity and Host Responses. mBio. 2024, 15, e0335123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, A.; Zajta, E.; Csonka, K.; Vágvölgyi, C.; Netea, M.G.; Gácser, A. Specific Pathways Mediating Inflammasome Activation by Candida parapsilosis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konwar, A.; Mathur, K.; Pandey, S.; Bhorali, K.; Thakur, A.; Puria, R. Insights into the Evolution of Candidalysin and Recent Developments. Arch. Microbiol. 2025, 207, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branzk, N.; Lubojemska, A.; Hardison, S.E.; Wang, Q.; Gutierrez, M.G.; Brown, G.D.; Papayannopoulos, V. Neutrophils Sense Microbe Size and Selectively Release Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Response to Large Pathogens. Nat. Immunol. 2014, 15, 1017–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Sun, Y.; Chen, L.; Cheng, Y.; Jin, P.; Zhang, W.; Zheng, L.; Liu, J.; Zhou, T.; Xu, Z.; et al. Candida Causes Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis by Forming Morphologically Disparate Biofilms on the Human Vaginal Epithelium. Biofilm 2023, 6, 100162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seider, K.; Gerwien, F.; Kasper, L.; Allert, S.; Brunke, S.; Jablonowski, N.; Schwarzmüller, T.; Barz, D.; Rupp, S.; Kuchler, K.; Hube, B. Immune Evasion, Stress Resistance, and Efficient Nutrient Acquisition are Crucial for Intracellular Survival of Candida glabrata Within Macrophages. Eukaryot. Cell 2014, 13, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, A.; Németh, T.; Csonka, K.; Horváth, P.; Vágvölgyi, C.; Vizler, C.; Nosanchuk, J.D.; Gácser, A. Secreted Candida parapsilosis Lipase Modulates the Immune Response of Primary Human Macrophages. Virulence 2014, 5, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulig, K.; Karnas, E.; Woznicka, O.; Kuleta, P.; Zuba-Surma, E.; Pyza, E.; Osyczka, A.; Kozik, A.; Rapala-Kozik, M.; Karkowska-Kuleta, J. Insight into the Properties and Immunoregulatory Effect of Extracellular Vesicles Produced by Candida glabrata, Candida parapsilosis, and Candida tropicalis Biofilms. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 879237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pezak, C.M.; Iosue, C.L.; Wykoff, D.D. Simplified J774A.1 Macrophage Assay for Fungal Pathogenicity Demonstrates Non-clinical Nakaseomyces glabratus Strains Survive Better Than Lab Strains. MicroPubl. Biol. 2024, 22, 2024–10.17912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.P.; Willems, H.M.E.; Moyes, D.L.; Shoaie, S.; Barker, K.S.; Tan, S.L.; Palmer, G.E.; Hube, B.; Naglik, J.R.; Peters, B.M. Candidalysin Drives Epithelial Signaling, Neutrophil Recruitment, and Immunopathology at the Vaginal Mucosa. Infect. Immun. 2018, 86, e00645–e00717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willems, H.M.E.; Lowes, D.J.; Barker, K.S.; Palmer, G.E.; Peters, B.M. Comparative Analysis of the Capacity of the Candida Species to Elicit Vaginal Immunopathology. Infect. Immun. 2018, 86, e00527–e00618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netea, M.G.; Joosten, L.A.; van der Meer, J.W.; Kullberg, B.J.; van de Veerdonk, F.L. Immune Defence Against Candida Fungal Infections. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 630–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.P.; Moyes, D.L.; Ho, J.; Naglik, J.R. Candida Innate Immunity at the Mucosa. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 89, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, J.; Peters, B.M.; Noverr, M.C.; Fidel, P.L. Jr. Novel Mechanism behind the Immunopathogenesis of Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: "Neutrophil Anergy". Infect. Immun. 2018, 86, e00684–e00717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosati, D.; Bruno, M.; Jaeger, M.; Ten Oever, J.; Netea, M.G. Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: An Immunological Perspective. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.F.; Rodrigues, M.E.; Henriques, M. Candida sp. Infections in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, B.M.; Yano, J.; Noverr, M.C.; Fidel, P.L. Jr. Candida Vaginitis: When Opportunism Knocks, the Host Responds. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1003965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashman, R.B. Protective and Pathologic Immune Responses against Candida albicans Infection. Front. Biosci. 2008, 13, 3334–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wozniak, K.L.; Wormley, F.L. Jr; Fidel, P.L. Jr. Candida-specific Antibodies During Experimental Vaginal Candidiasis in Mice. Infect. Immun. 2002, 70, 5790–5799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linhares, L.M.; Witkin, S.S.; Miranda, S.D.; Fonseca, A.M.; Pinotti, J.A.; Ledger, W.J. Differentiation Between Women with Vulvovaginal Symptoms who are Positive or Negative for Candida species by Culture. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 9, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosen, H. Chronic Monilial Vaginitis. Ann. Allergy 1971, 29, 499. [Google Scholar]

- Kudelko, N.M. Allergy in Chronic Monilial Vaginitis. Ann. Allergy 1971, 29, 266–267. [Google Scholar]

- Witkin, S.S.; Jeremias, J.; Ledger, W.J. A Localized Vaginal Allergic Response in Women with Recurrent Vaginitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1988, 81, 412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.X.; Li, T.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.X.; Liu, Z.H. Lactobacillus crispatus Modulates Vaginal Epithelial Cell Innate Response to Candida albicans. Chin. Med. J. (Engl). 2017, 130, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldo, P.C.; de Carvalho, J.B.; do Amaral, R.L.; da Silveira Gonçalves, A.K.; Eleutério, J. Jr; Guimarães, F. Identification of Immune Cells by Flow Cytometry in Vaginal Lavages from Women with Vulvovaginitis and Normal Microflora. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2012, 67, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricchi, F.; Kenno, S.; Pedretti, N.; Brenna, G.; De Seta, F.; Ardizzoni, A.; Pericolini, E. Cutibacterium acnes Lysate Improves Cellular Response against Candida albicans, Escherichia coli and Gardnerella vaginalis in an in vitro Model of Vaginal Infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1578831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassone, A.; De Bernardis, F.; Santoni, G. Anticandidal Immunity and Vaginitis: Novel Opportunities for Immune Intervention. Infect. Immun. 2007, 75, 4675–4686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wychrij, D.A.; Chapman, T.I.; Rayens, E.; Rabacal, W.; Willems, H.M.E.; Oworae, K.O.; Peters, B.M.; Norris, K.A. Protective Efficacy of the Pan-fungal Vaccine NXT-2 Against Vulvovaginal Candidiasis in a Murine Model. NPJ Vaccines 2025, 10, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadifar, F.; Balali, E.; Khadivi, R.; Hashemi, M.; Jebali, A. The Evaluation of a Novel Multi-epitope Vaccine Against Human Papillomavirus and Candida albicans. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2025, 23, 100489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Barbosa, A.; Pacheco, M.I.; Gomes, A.C.; Collins, T.; Vilanova, M.; Pais, C.; Correia, A.; Sampaio, P. Pre-clinical Evaluation of a Divalent Liposomal Vaccine to Control Invasive Candidiasis. NPJ Vaccines 2025, 10, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Bernardis, F.; Amacker, M.; Arancia, S.; Sandini, S.; Gremion, C.; Zurbriggen, R.; Moser, C.; Cassone, A. A Virosomal Vaccine Against Candidal Vaginitis: Immunogenicity, Efficacy and Safety Profile in Animal Models. Vaccine 2012, 30, 4490–4498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.E. Jr; Schwartz, M.M.; Schmidt, C.S.; Sobel, J.D.; Nyirjesy, P.; Schodel, F.; Marchus, E.; Lizakowski, M.; DeMontigny, E.A.; Hoeg, J.; et al. A Fungal Immunotherapeutic Vaccine (NDV-3A) for Treatment of Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis-A Phase 2 Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 66, 1928–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.A.; Khan, A.; Alnuqaydan, A.M.; Albutti, A.; Alharbi, B.F.; Owais, M. Targeting Azole-Resistant Candida albicans: Tetrapeptide Tuftsin-Modified Liposomal Vaccine Induces Superior Immune Protection. Vaccines (Basel) 2025, 13, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.A.; Mousa, A.M.; Alradhi, A.E.; Allemailem, K. Efficacy of Lipid Nanoparticles-based Vaccine to Protect Against Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (VVC): Implications for Women's Reproductive Health. Life Sci. 2025, 361, 123312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Barros, P.P.; Rossoni, R.D.; de Souza, C.M.; Scorzoni, L.; Fenley, J.C.; Junqueira, J.C. Candida Biofilms: An Update on Developmental Mechanisms and Therapeutic Challenges. Mycopathologia 2020, 185, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, M.; Nobile, C.J. Candida albicans Biofilms: Development, Regulation, and Molecular Mechanisms. Microbes Infect. 2016, 18, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, T.; Meng, Y.; Zhao, C.; Sheng, D.; Yang, S.; Dai, J.; Wei, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, G.; Liu, Y.; et al. Genome-scale Metabolic Modelling Reveals Specific Vaginal Lactobacillus Strains and Their Metabolites as Key Inhibitors of Candida albicans. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e0298424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tortelli, B.A.; Lewis, W.G.; Allsworth, J.E.; Member-Meneh, N.; Foster, L.R.; Reno, H.E.; Peipert, J.F.; Fay, J.C.; Lewis, A.L. Associations Between the Vaginal Microbiome and Candida Colonization in Women of Reproductive Age. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 222, 471.e1–471.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parolin, C.; Croatti, V.; Giordani, B.; Vitali, B. Vaginal Lactobacillus Impair Candida Dimorphic Switching and Biofilm Formation. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.N.; Lopes, L.C.; Cordero, R.J.; Nosanchuk, J.D. Sodium Butyrate Inhibits Pathogenic Yeast Growth and Enhances the Functions of Macrophages. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2011, 66, 2573–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, M.M.; Watson, C.; Grando, D. Garlic Alters the Expression of Putative Virulence Factor Genes SIR2 and ECE1 in Vulvovaginal C. albicans Isolates. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donlan, R.M. Biofilms: Microbial Life on Surfaces. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2002, 8, 881–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKloud, E.; Delaney, C.; Sherry, L.; Kean, R.; Williams, S.; Metcalfe, R.; Thomas, R.; Richardson, R.; Gerasimidis, K.; Nile, et al. Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: A Dynamic Interkingdom Biofilm Disease of Candida and Lactobacillus. mSystems 2021, 6, e0062221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarnowski, R.; Noll, A.; Chevrette, M.G.; Sanchez, H.; Jones, R.; Anhalt, H.; Fossen, J.; Jaromin, A.; Currie, C.; Nett, et al. Coordination of Fungal Biofilm Development by Extracellular Vesicle Cargo. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravel, J.; Gajer, P.; Abdo, Z.; Schneider, G.M.; Koenig, S.S.K.; McCulle, S.L.; Karlebach, S.; Gorle, R.; Russell, J.; Tacket, C.O.; et al. Vaginal Microbiome of Reproductive-age Women. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2011, 108, 4680–4687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordani, B.; Naldi, M.; Croatti, V.; Parolin, C.; Erdoğan, Ü.; Bartolini, M.; Vitali, B. Exopolysaccharides from Vaginal Lactobacilli Modulate Microbial Biofilms. Microb. Cell Fact. 2023, 22, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, W.Y.; Lee, Y.J.; Jo, S.; Shin, S.L.; Kim, T.R.; Sohn, M.; Seol, H.J. Effects of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum LM1215 on Candida albicans and Gardnerella vaginalis. Yonsei Med. J. 2024, 65, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, A.; Ghanem, K. G.; Rogers, L.; Zinalabedini, A.; Brotman, R. M.; Zenilman, J.; Tuddenham, S. Clinicians' Use of Intravaginal Boric Acid Maintenance Therapy for Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis and Bacterial Vaginosis. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2019, 46, 810–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Seta, F.; Schmidt, M.; Vu, B.; Essmann, M.; Larsen, B. Antifungal Mechanisms Supporting Boric acid Therapy of Candida vaginitis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2009, 63, 325–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, Q.; Feng, Y.; Li, J.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ke, X. A "Three-in-one" Thermosensitive Gel System that Enhances Mucus and Biofilm penetration for the Treatment of Vulvovaginal Candidiasis. J. Control. Release 2025, 382, 113666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, C.J.; Grando, D.; Garland, S.M.; Myers, S.; Fairley, C.K.; Pirotta, M. Premenstrual Vaginal Colonization of Candida and Symptoms of Vaginitis. J. Med. Microbiol. 2012, 61, 1580–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC, 2021. Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment. Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (VVC). 2021. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/candidiasis.htm (accessed on 4th June 2025).

- ASHM, The Australasian Society for HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexual Health Medicine (ASHM). Australian STI management guidelines for use in primary care. Candidiasis. 2024. Available online: https://sti.guidelines.org.au/sexually-transmissible-infections/candidiasis/ (accessed on 4th June 2025).

- Farr, A.; Effendy, I.; Frey Tirri, B.; Hof, H.; Mayser, P.; Petricevic, L.; Ruhnke, M.; Schaller, M.; Schaefer, A.P.A.; Sustr, V.; et al. Guideline: Vulvovaginal Candidosis (AWMF 015/072, level S2k). Mycoses 2021, 64, 583–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donders, G.; Sziller, I.O.; Paavonen, J.; Hay, P. , de Seta, F.; Bohbot, J.M.; Kotarski, J.; Vives, J.A.; Szabo, B.; Cepuliené, R.; Mendling, W. Management of Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidosis: Narrative Review of the Literature and European Expert Panel Opinion. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 934353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quindos, G.; Marcos-Arias, C.; Miranda-Cadena, K. The Future of Non-invasive Azole Antifungal Treatment Options for the Management of Vulvovaginal Candidiasis. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2025, 23, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, T.; Sobel, J.D. Genital Cutaneous Candidiasis versus Chronic Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: Distinct Diseases, Different Populations. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2025, 38, e0002025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Katz, H.I.; Shear, N.H. Drug Interactions with Itraconazole, Fluconazole, and Terbinafine and their Management. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1999, 41, 237–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, I.W. The Value of Chronic Suppressive Therapy with Itraconazole versus Clotrimazole in Women with Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis. Genitourin. Med. 1992, 68, 374–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denison, H.J.; Worswick, J.; Bond, C.M.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Mayhew, A.; Gnani Ramadoss, S.; Robertson, C.; Schaafsma, M.E.; Watson, M.C. Oral versus Intra-vaginal Imidazole and Triazole Anti-fungal Treatment of Uncomplicated Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (Thrush). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 8, CD002845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, G.; Watson, C.; Deckx, L.; Pirotta, M.; Smith, J.; van Driel, M.L. Treatment for Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (Thrush). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 1, CD009151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sobel, J. D.; Sobel, R. Current Treatment Options for Vulvovaginal Candidiasis Caused by Azole-resistant Candida species. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2018, 19, 971–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobel, J.D. New Antifungals for Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: What is their Role? Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 76, 783–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kriegl, L.; Eggar, M.; Bayer, J.; Hoenigl, M.; Krause, R. New Treatment Options for Critically Important WHO Fungal Priority Pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2025, 31, 922–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Phase 11b / 111 Study of prof-001 for the Treatment of Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (RVVC). Available online: https://ctv.veeva.com/study/a-phase-iib-iii-study-of-prof-001-for-the-treatment-of-patients-with-recurrent-vulvovaginal-candidia (accessed on 4th June 2025).

- Chayachinda, C.; Thamkhantho, M.; Rekhawasin, T.; Klerdklinhom, C. Sertaconazole 300 mg versus Clotrimazole 500 mg Vaginal Suppository for Treating Pregnant Women with Acute Vaginal Candidiasis: A Double-blinded, Randomized Trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Cássia Orlandi Sardi, J.; Silva, D.R.; Anibal, P.C.; de Campos Baldin, J.J.C.M.; Ramalho, S.R.; Rosalen, P.L.; Macedo, M.L.R.; Hofling, J.F. Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: Epidemiology and Risk Factors, Pathogenesis, Resistance, and New Therapeutic Options. Curr. Fungal Infect. Rep. 2021, 15, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howley, M.M.; Carter, T.C.; Browne, M.L.; Romitti, P.A.; Cunniff, C.M.; Druschel, C.M. National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Fluconazole use and Birth Defects in the National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 214, e1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, E.A.; Howley, M.M.; Fisher, S.C.; Van Zutphen, A.R.; Werler, M.M.; Romitti, P.A.; Browne, M.L. National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Antifungal Medication Use During Pregnancy and the Risk of Selected Major Birth Defects in the National Birth Defects Prevention Study, 1997-2011. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2024, 33, e5741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mølgaard-Nielsen, D.; Pasternak, B.; Hviid, A. Use of Oral Fluconazole During Pregnancy and the Risk of Birth Defects. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 830–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachum, Z.; Suleiman, A.; Colodner, R.; Battino, S.; Wattad, M.; Kuzmin, O.; Yefet, E. Oral Probiotics to Prevent Recurrent Vulvovaginal Infections During Pregnancy-Multicenter Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nutrients. 2025, 17, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burhanuddin, H.; Enggi, C.K.; Tangdilintin, F.; Saputra, R.R.; Putra, P.P.; Sartini, S.; Aliyah, A.; Agustina, R.; Domínguez-Robles, J.; Aswad, M.; Permana, A.D. Development of Amphotericin B Inclusion Complex Formulation in Dissolvable Microarray Patches for Intravaginal Delivery. Daru 2024, 33, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, M.U.; Rajput, A.P.; Belgamwar, V.S.; Chalikwar, S.S. Development and Characterization of Amphotericin B Nanoemulsion-loaded Mucoadhesive Gel for Treatment of Vulvovaginal Candidiasis. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornely, O.; Sprute, R.; Bassetti, M.; Chen, S.C.; Groll, A.H.; Kurzai, O.; Lass-Flörl, C.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L. , Rautemaa-Richardson, R. , Revathi, G.; et al. Global Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Candidiasis: An Initiative of the ECMM in Cooperation with ISHAM and ASM. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, e280–e293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radesca Moncayo, Y. Vaginal Candidiasis, Predisposing Factors, Symptoms and Treatment. SCT Proc. Interdiscip. Insights Innov. 2024, 2, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Li, P.; Lu, J.; Li, X.; Li, M.; Wu, Y.; Zheng, M.; Cao, Y.; Liao, Q.; Ge, Z.; Zhang, L. A Non-antibiotic Antimicrobial Drug, a Biological Bacteriostatic Agent, is useful for Treating Aerobic Vaginitis, Bacterial Vaginosis, and Vulvovaginal Candidiasis. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1341878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhof, M.; Lipovac, M.; Kurz, C.; Barta, J.; Verhoeven, H.C.; Huber, J.C. Propolis Solution for the Treatment of Chronic Vaginitis. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2005, 89, 127–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Cerecero, O.; Islas-Garduño, A.L.; Zamilpa, A.; Tortoriello, J. Effectiveness of Ageratina pichinchensis Extract in Patients with Vulvovaginal Candidiasis. A Randomized, Double-blind, and Controlled Pilot Study. Phytother. Res. 2017, 31, 885–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimy, F.; Dolatian, M.; Moatar, F.; Alavi, M.H. Comparison of the Therapeutic Effects of Garcin® and Fluconazole on Candida Vaginitis. Singapore Med. J. 2015, 56, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatfield, J. , Saad, S., Housewright, C. Dietary Supplements and Bleeding. Proc. (Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent). 2022, 35, 802–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertholf, M.E.; Stafford, M.J. Colonization of Candida albicans in Vagina, Rectum, and Mouth. J. Fam. Pract. 1983, 16, 919–924. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Delavy, M.; Sertour, N.; Patin, E.; Le Chatelier, E.; Cole, N.; Dubois, F.; Xie, Z.; Saint-André, V.; Manichanh, C.; Walker, A.W.; et al. Unveiling Candida albicans Intestinal Carriage in Healthy Volunteers: The role of Micro- and Mycobiota, Diet, Host Genetics and Immune Response. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2287618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrory, C. , Lenardon, M., Traven, A. Bacteria-derived Short-chain Fatty Acids as Potential Regulators of Fungal Commensalism and Pathogenesis. Trends Microbiol. 2024, 32, 1106–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, P.; Joyce, S.A.; O'Toole, P.W.; O'Connor, E.M. Dietary Fibre Modulates the Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djusse, M.E.; Prinelli, F.; Camboni, T.; Ceccarani, C.; Consolandi, C.; Conti, S.; Dall'Asta, M.; Danesi, F.; Laghi, L.; Curatolo, F.M.; et al. Dietary Habits and Vaginal Environment: Can a Beneficial Impact be Expected? Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1582283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.C.; McAndrew, T.; Chen, Z.; Harari, A.; Barris, D.M.; Viswanathan, S.; Rodriguez, A.C.; Castle, P.; Herrero, R.; Schiffman, M.; Burk, R.D. The Cervical Microbiome over 7 Years and a Comparison of Methodologies for its Characterization. PLoS One 2012, 7, e40425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Lee, S.; Kwon, M.Y.; Kim, M. Clinical Significance of Composition and Functional Diversity of the Vaginal Microbiome in Recurrent Vaginitis. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 851670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepsen, I.E.; Saxtorph, M.H.; Englund, A.L.M.; Petersen, K.B.; Wissing, M.L.M.; Hviid, T.V.F.; Macklon, N. Probiotic Treatment with Specific Lactobacilli does not Improve an Unfavorable Vaginal Microbiota Prior to Fertility Treatment - A Randomized, Double-blinded, Placebo-controlled Trial. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2022, 13, 1057022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koedooder, R.; Singer, M.; Schoenmakers, S.; Savelkoul, P.H.M.; Morré, S.A.; de Jonge, J.D.; Poort, L.; Cuypers, W.J.S.S.; Beckers, N.G.M.; Broekmans, F.J.M.; et al. The Vaginal Microbiome as a Predictor for Outcome of in Vitro Fertilization with or without Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection: A Prospective Study. Hum. Reprod. 2019, 34, 1042–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, M.; Armengol, E.; Del Casale, A.; Campedelli, I.; Aldea-Perona, A.; Pérez Otero, M.; Rodriguez-Palmero, M.; Espadaler-Mazo, J.; Huedo, P. Lactobacillus gasseri CECT 30648 Shows Probiotic Characteristics and Colonizes the Vagina of Healthy Women after Oral Administration. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e0021125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- France, M.; Alizadeh, M.; Brown, S.; Ma, B.; Ravel, J. Towards a Deeper Understanding of the Vaginal Microbiota. Nat. Microbiol. 2022, 7, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Houdt, R.; Ma, B.; Bruisten, S.M.; Speksnijder, A.G.C.L.; Ravel, J. , de Vries, H.J.C. Lactobacillus iners-dominated Vaginal Microbiota is Associated with Increased Susceptibility to Chlamydia trachomatis Infection in Dutch Women: A case-control Study. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2018, 94, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, E.; Hemmerling, A.; Miller, S.; Huibner, S.; Kulikova, M.; Crawford, E.; Castañeda, G.R.; Coburn, B.; Cohen, C.R.; Kaul, R. Vaginal Lactobacillus crispatus Persistence Following Application of a Live Biotherapeutic Product: Colonization Phenotypes and Genital Immune Impact. Microbiome. 2024, 12, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, C.R.; Wierzbicki, M.R.; French, A.L.; Morris, S.; Newmann, S.; Reno, H.; Green, L.; Miller, S.; Powell, J.; Parks, T.; Hemmerling, A. Randomized Trial of Lactin-V to Prevent Recurrence of Bacterial Vaginosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1906–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gosmann, C.; Anahtar, M.N.; Handley, S.A.; Farcasanu, M.; Abu-Ali, G.; Bowman, B.A.; Padavattan, N.; Desai, C.; Droit, L.; Moodley, A.; et al. Lactobacillus-Deficient Cervicovaginal Bacterial Communities Are Associated with Increased HIV Acquisition in Young South African Women. Immunity. 2017, 46, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Nood, E.; Vrieze, A.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Fuentes, S.; Zoetendal, E.G.; de Vos, W.M.; Visser, C.E.; Kuijper, E.J.; Bartelsman, J.F.; Tijssen, J.G.; et al. Duodenal Infusion of Donor Feces for Recurrent Clostridium difficile. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B.C.; Zuppi, M.; Derraik, J.G.B.; Albert, B.B.; Tweedie-Cullen, R.Y.; Leong, K.S.W.; Beck, K.L.; Vatanen, T.; O'Sullivan, J.M.; Cutfield, W.S.; Gut Bugs Study Group. Long-term Health Outcomes in Adolescents with Obesity Treated with Faecal Microbiota Transplantation: 4-year Follow-up. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev-Sagie, A.; Goldman-Wohl, D.; Cohen, Y.; Dori-Bachash, M.; Leshem, A.; Mor, U.; Strahilevitz, J.; Moses, A.E.; Shapiro, H.; Yagel, S.; Elinav, E. Vaginal Microbiome Transplantation in Women with Intractable Bacterial Vaginosis. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1500–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrønding, T.; Vomstein, K.; Bosma, E.F.; Mortensen, B.; Westh, H.; Heintz, J.E.; Mollerup, S.; Petersen, A.M.; Ensign, L.M.; DeLong, K.; et al. Antibiotic-free Vaginal Microbiota Transplant with Donor Engraftment, Dysbiosis Resolution and Live Birth After Recurrent Pregnancy Loss: A Proof of Concept Case Study. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 61, 102070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wu, F.; Chen, J.; Luo, J.; Wu, C.; Chen, T. Effectiveness of Vaginal Probiotics Lactobacillus crispatus chen-01 in Women with High-risk HPV infection: A Prospective Controlled Pilot Study. Aging (Albany NY) 2024, 16, 11446–11459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- So, K.A.; Yang, E.J.; Kim, N.R.; Hong, S.R.; Lee, J.H.; Hwang, C.S.; Shim, S.H.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, T.J. Changes of Vaginal Microbiota During Cervical Carcinogenesis in Women with Human Papillomavirus Infection. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0238705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemmerling, A.; Mitchell, C.M.; Demby, S.; Ghebremichael, M.; Elsherbini, J.; Xu, J.; Xulu, N.; Shih, J.; Dong, K.; Govender, V.; et al. Effect of the Vaginal Live Biotherapeutic LACTIN-V (Lactobacillus crispatus CTV-05) on Vaginal Microbiota and Genital Tract Inflammation Among Women at High Risk of HIV Acquisition in South Africa: A Phase 2, Randomised, Placebo-controlled Trial. Lancet Microbe 2025, 6, 101037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Baz, N.; Kyser, A.; Mahmoud, M.Y.; Farrell, C.Z.; Ginocchio, S.; Frieboes, H.B.; Doster, R.S. Modulation of Group B Streptococcus Infection and Vaginal Cell Inflammatory signaling in vitro by Lactobacillus crispatus-loaded Electrospun Fibers. Infect. Immun. 2025, 0, e0017025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravel, J.; Simmons, S.; Jaswa, E.G.; Gottfried, S.; Greene, M.; Kellogg-Spadt, S.; Gevers, D.; Harper, D.M. Impact of a Multi-strain L. crispatus-based Vaginal Synbiotic on the Vaginal Microbiome: A Randomized Placebo-controlled Trial. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2025, 11, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).