1. Introduction

Carbon fiber reinforced plastics (CFRP) are polymer matrix composites that combine high strength carbon fibers with a thermosetting epoxy resin, yielding materials with a high strength to weight ratio and high elastic module due to the low density of the fibers and the rigid polymer network [

1,

2,

3]. In addition to their mechanical advantages, CFRP demonstrates excellent corrosion and chemical resistance, thermal stability, and the capability to form complex geometries, which explains their widespread adoption in aerospace, marine, automotive, construction, and energy applications, for example wind turbine blades [

4,

5,

6]. Compared to metallic structural materials, CFRP often provide higher stiffness and strength at a lower mass with superior fatigue and corrosion performance, motivating their increasing use in weight sensitive engineering structures [

7].

Conventional processing methods for CFRP, including mechanical cutting, milling, drilling, waterjet, and abrasive-jet machining, are mature and scalable but also have limitations. Mechanical methods cause tool wear, induce microcracks, fiber pull-out, interlaminar delamination, and generate damage in the polymer matrix [

8]. Waterjet and abrasive-jet techniques reduce thermal loading but often produce tapered profiles, require high energy input, and impose costs for abrasive handling and disposal [

9]. Laser processing, as a non-contact technique, offers high precision, speed and repeatability without tool wear and with reduced dust emissions. These advantages make it an attractive alternative for CFRP machining [

10,

11]. Ultrashort-pulse (femtosecond) lasers can minimize heat diffusion during interaction and can substantially shrink the heat-affected zone (HAZ) relative to nanosecond and picosecond laser systems, enabling thermal ablation regimes and higher quality cuts in polymer-based composites [

12,

13,

14].

The interaction of a laser and CFRP is governed by the optical and thermal contrasts between carbon fibers and the epoxy matrix, as well as by the laser parameters (wavelength, fluence, pulse duration, and repetition rate). Carbon fibers strongly absorb infrared (IR) radiation, whereas typical epoxy matrices exhibit much lower absorption in the IR. Also, UV laser wavelengths can directly break polymer bonds and promote photochemical mechanisms of ablation [

10,

15,

16]. Pulse duration critically determines the balance between non-thermal (photo-induced) and thermal mechanisms: nanosecond pulses favor heat accumulation, melting, and a wide HAZ, while picosecond and femtosecond pulses confine energy deposition temporally and reduce collateral heating, improving cut quality when parameters are optimized [

17].

Despite these advantages, laser cutting of CFRP still faces practical challenges. Selective degradation of the epoxy matrix, formation of HAZ, rough cut surfaces, and tapering of the kerf are frequently reported, all of which can expose fibers, reduce interfacial adhesion, and degrade mechanical performance of the processed part [

18,

19,

20]. Polymer degradation under intense irradiation proceeds via bond scission and pyrolysis pathways that generate small volatile species and carbonaceous residues. These processes are exacerbated by heat conduction along fibers into the surrounding matrix, causing additional local thermal damage and delamination [

21,

22].

To mitigate matrix damage and improve cut quality, several strategies have been explored. Optimization of laser parameters (reduced pulse energy, increased scanning speed, multi-pass strategies), control of the processing atmosphere (oxygen or inert gas assist), and implementation of water-jet-guided laser techniques have demonstrated reductions in HAZ and improved kerf characteristics [

14,

23,

24]. Complementary to these operational measures, modification of the polymer matrix by incorporation of light-absorbing additives offers a route to redistribute deposited energy, limit localized overheating and steer the ablation mechanism towards more controlled removal. Such absorbers include inorganic oxides and salts, metal nanoparticles, carbonaceous fillers (carbon black, carbon nanotubes, graphene), and phosphate-based compounds. Experimental studies report that these fillers can reduce char formation, smooth the kerf, and improve fiber-matrix adhesion after laser processing [

25,

26].

Copper hydroxyphosphate (Cu

2(OH)PO

4) emerges as a promising absorber for epoxy-based composites. Structurally, Cu

2(OH)PO

4 consists of alternating Cu octahedron and trigonal bipyramid coordination units and PO

4 tetrahedra with bridging hydroxyls, that yields notable optical activity and thermal stability [

27,

28]. Copper hydroxyphosphate and related copper phosphates exhibit absorption bands extending into the visible and near infrared region can be synthesized by straightforward wet-chemical or hydrothermal routes, which facilitates their incorporation as micro-/nano-fillers in epoxy matrix [

29,

30,

31]. The combination of favorable spectral response, chemical robustness and intrinsic thermal transport of copper-based phases suggests that Cu

2(OH)PO

4 may serve as an efficient local energy absorber for laser irradiation, moderating matrix heating and improving the material removal homogeneity.

In summary, while advances in ultrashort-pulse laser processing and parameter control have improved CFRP machining, thermal degradation of the epoxy matrix, the resulting defects continue to limit cut quality and structural performance. The targeted introduction of laser-absorbing fillers, particularly copper hydroxyphosphate, represents a promising strategy to redistribute laser energy, reduce localized damage and enhance process reproducibility. Motivated by these considerations, the present study focuses on the synthesis of copper hydroxyphosphate particles and their incorporation into epoxy and CFRP systems, with the aim of assessing their influence on femtosecond laser ablation efficiency, kerf morphology and the uniformity of matrix removal.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. CFRP Materials and Copper Hydroxyphosphate Synthesis

To obtain CFRP the epoxy resin CHS-EPOXY 619 (Viscosity 0.4–0.9 Pa·s, 25 °C, EEW 155–170) and cycloaliphatic hardener TELALIT 0600 (HEW 62 g/mol, Amine number 450–500 mg KOH/g) were used. Both purchased from local supplier (Spolchemie, Usti nad Labem, Czech Republic). Carbon fabric 3K, 200 g/m2, twill was used as reinforcing fibers.

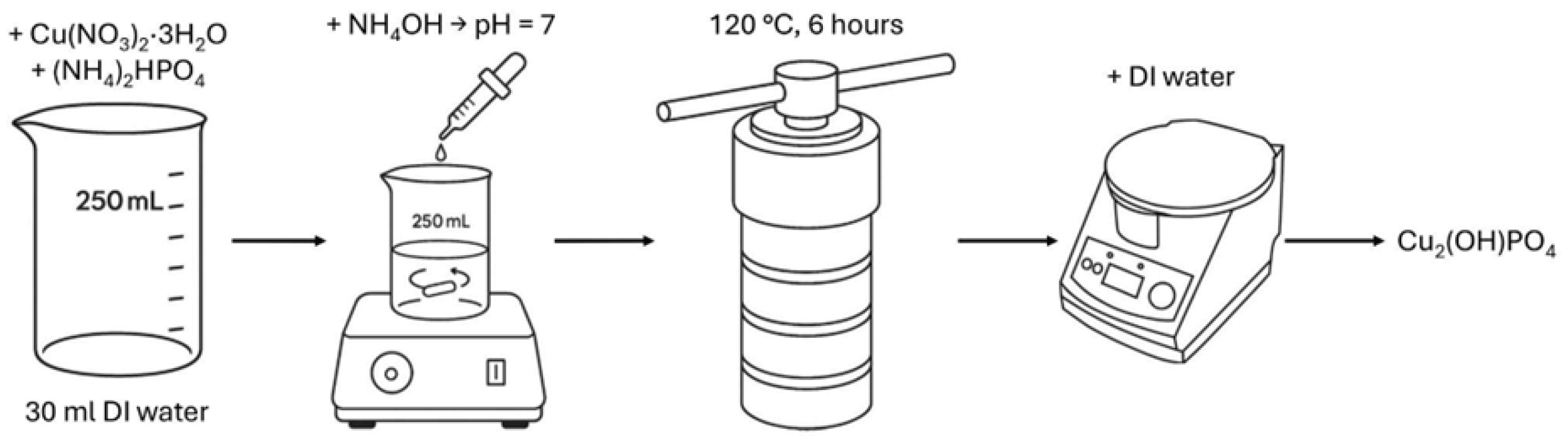

Copper hydroxyphosphate (Cu

2(OH)PO

4) was synthesized using a modified hydrothermal method, based on papers [

26,

31,

32,

33]. Initially, 0.02 mol of copper(II) nitrate trihydrate (Cu(NO

3)

2·3H

2O) and 0.01 mol of diammonium phosphate ((NH

4)

2HPO

4) were dissolved in 30 mL of deionized water. Copper(II) nitrate trihydrate was chosen as the precursor owing to the high photocatalytic activity of Cu

2(OH)PO

4 synthesized from this compound [

33]. The pH of the solution was adjusted to 7 by the dropwise addition of aqueous ammonia, followed by continuous stirring with a magnetic stirrer for 10 min. All named substances were purchased from the local supplier HLR Ukraine (Chemlaborreactiv LLC, Brovary, Ukraine). The resulting mixture was then transferred into a polytetrafluoroethylene-lined stainless-steel autoclave (BAOSHISHAN, Zhengzhou, China) and subjected to hydrothermal treatment at 120 °C for 6 h. The obtained precipitate was collected, thoroughly washed with deionized water, separated by centrifugation (CF-10, Daihan Scientific, Daejeon, Korea), and subsequently dried at 60 °C for 2 h to yield the copper hydroxyphosphate product.

Figure 1.

Scheme of copper hydroxyphosphate synthesis procedure.

Figure 1.

Scheme of copper hydroxyphosphate synthesis procedure.

2.2. CFRP Preparation

Carbon fiber reinforced plastic (CFRP) laminates were manufactured using an epoxy resin matrix modified with copper hydroxyphosphate additive. A pre-weighed amount of copper hydroxyphosphate powder (1 wt. %) was dispersed in the epoxy oligomer by mechanical stirring at 2000 rpm for 10 minutes. The mixture was then vacuumed to remove entrapped air bubbles. After dispersion, a curing agent was added in the stoichiometric ratio recommended by the supplier, and the mixture was stirred for another 5 minutes at 200 rpm.

The carbon fiber fabric was impregnated with the epoxy system by hand lay-up and compressed under pressure to expel air bubbles. The laminates were made from 1 layer with a fiber volume fraction of approximately ~60%. The curing process was carried out at room temperature for 72 hours, followed by post-curing at 50 °C for 2 hours to ensure complete cross-linking of the epoxy resin system. The prepared CFRP laminates were cut into samples of sizes suitable for femtosecond laser ablation experiments (50 x 30 mm).

2.3. Optical Setup

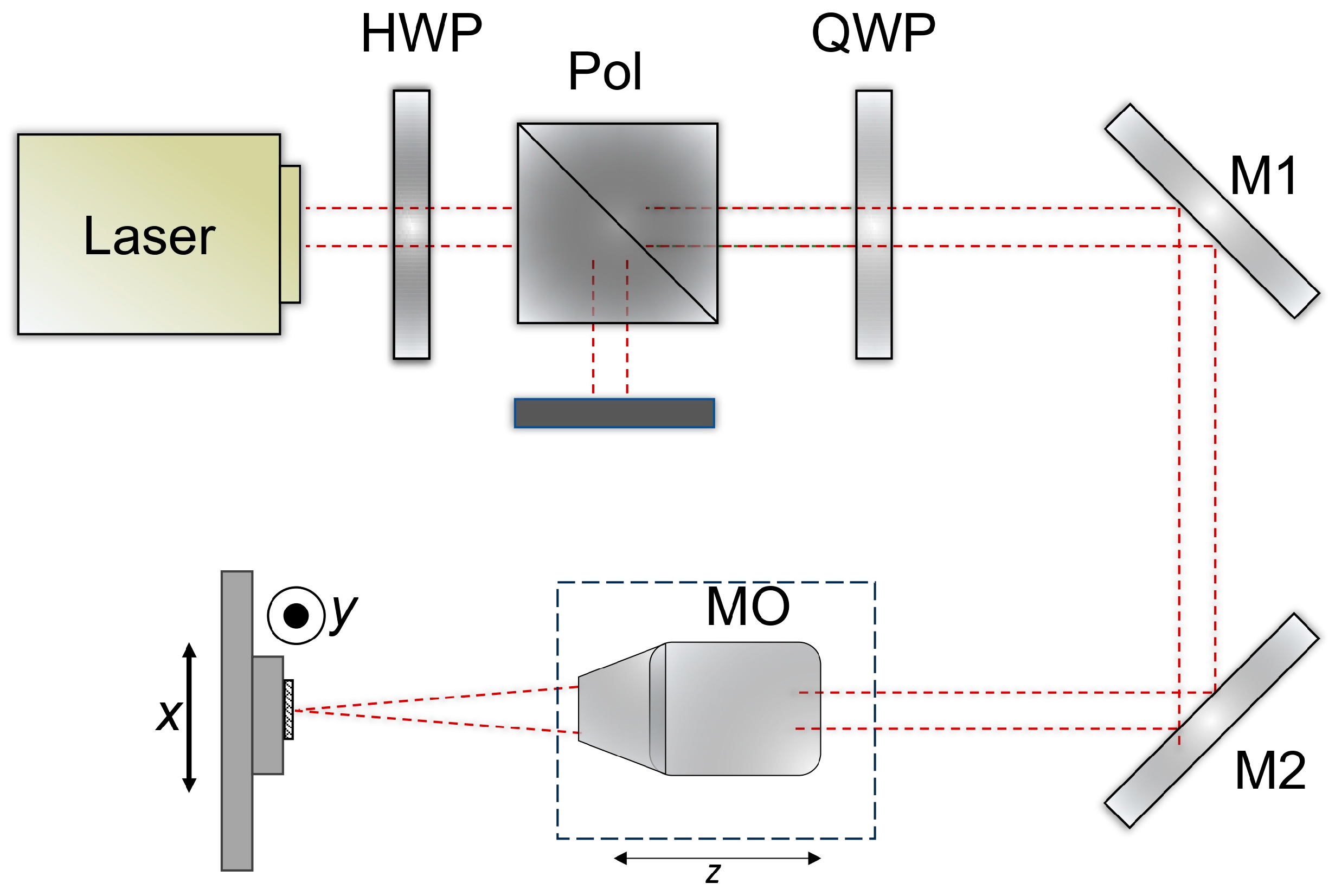

The optical setup is shown in

Figure 2. A laser beam with a wavelength of 1030 nm (Pharos laser, Light Conversion, Vilnius, Lithuania) and a diameter of approximately 4.1 mm (1/e

2) was passed through a quarter-wave plate (QWP) and directed into a 10× Plan Apo NIR microscope objective (MO) (10X Mitutoyo Plan Apo NIR, Kawasaki, Japan) mounted on a motorized z-stage. The power was controlled by an external attenuator – half-wave plate (HWP) and a polarizer (Pol). The beam was focused to a spot size of ~3.9 μm on the surface of the CFRP sample, which was fixed on XY linear stages (Aerotech ant130-xy, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). The laser system can operate at powers up to 6 W and repetition rates up to 200 kHz. The output power was further adjusted using an external attenuator consisting of a half-wave plate (HWP) and a polarizer. Optimal parameters were evaluated in previous work [

34].

During the experiments, the CFRP samples were processed by a bidirectional hatching motion of the stages, with a hatch spacing of 1.4 μm and a pulse-to-pulse overlap of ~82% along each line for the best pulse duration and fluence. Square patterns of 0.5 × 0.5 mm were fabricated without repeating the hatch. The single-pulse energy applied within the squares ranged from 0.5 μJ to 16 μJ. Pulse duration was the shortest pulse duration available for our femtosecond laser, equal to 190 fs. After laser processing, the samples were cleaned in an ultrasonic bath using distilled water. The ablated square volumes were subsequently measured with an optical profiler (Sensofar S neox, Barcelona, Spain), and the energy-specific volume was then calculated.

2.4. Characterization

Chemical analysis was performed via FTIR in ATR mode on IRSpirit spectrometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan), UV-VIS-NIR spectroscopy on UV-3600i Plus spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan), XPS on K-Alpha X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and XRD on Ultima-IV (Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

The surface topography of CFRP materials and copper hydroxyphosphate additive was studied using MIRA3 LMU scanning electron microscope (Tescan, Brno, Czech Republic). The samples were coated with a 15 nm thick Au-Pd layer using a precision coating and etching system (682 PECS, Gatan, Pleasanton, CA, USA) to reduce the surface charge, t. For ablation efficiency analysis was used optical profilometer Sensofar S neox with SensoVIEW 1.8.0 software (Sensofar metrology, Barcelona, Spain).

2.5. Ablation Efficiency Calculation

Ablation efficiency calculation was performed according to papers [

35,

36]. The ablation efficiency is expressed as the specific energy ΔV/ΔE, defined by the following relation [

35,

36]:

where

δ denotes the effective penetration depth of the laser energy,

ϕ0 represents the peak fluence of the incident beam, and

ϕth is the threshold fluence required to initiate ablation.

3. Results

3.1. Copper Hydroxyphosphate Characterization

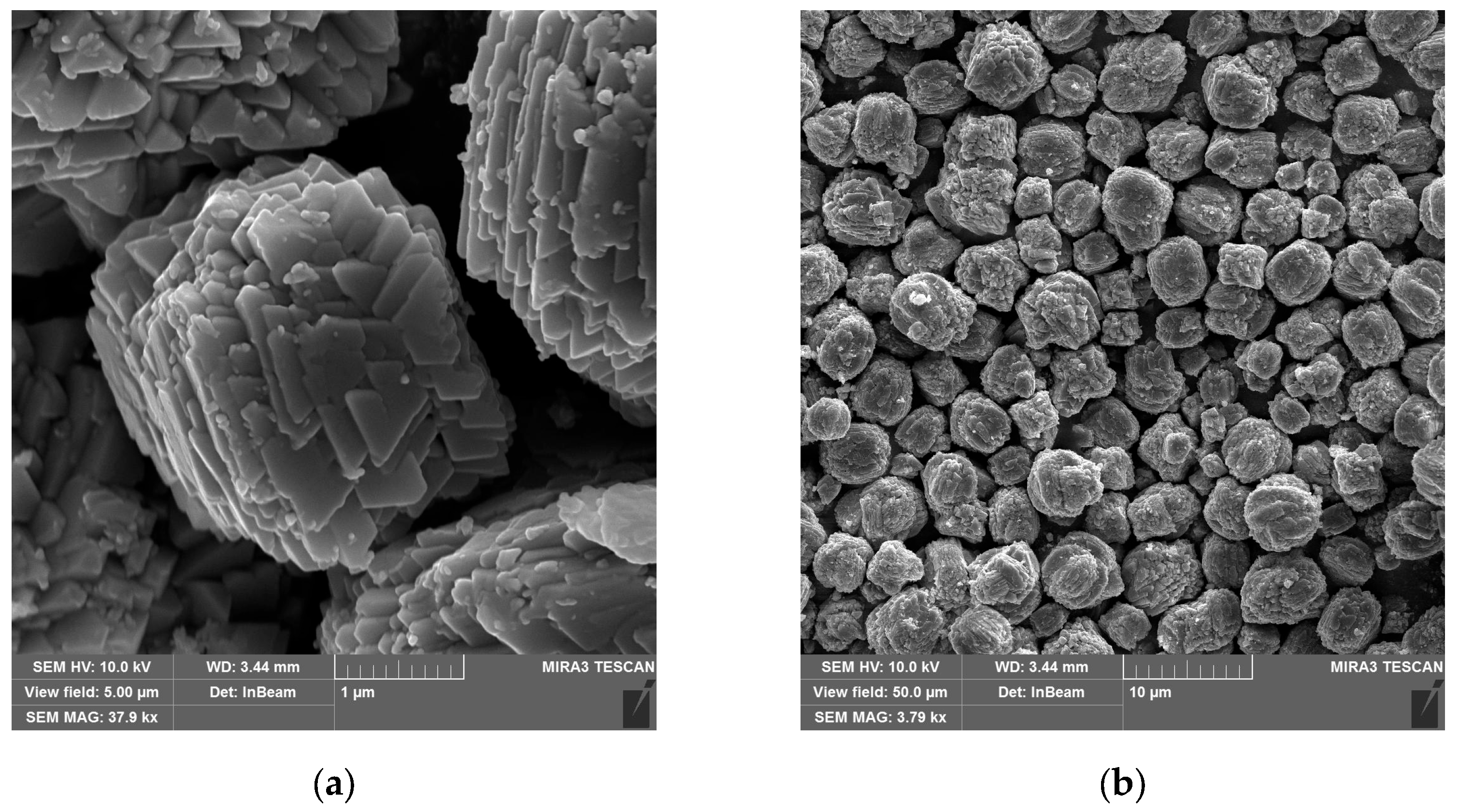

Figure 3 shows scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of the synthesized copper hydroxyphosphate particles. These particles exhibit distinct morphology in the form of cuboid microaggregates with stepped plates on their surfaces (

Figure 3a). The diameter of the microaggregates ranges from ~1 to ~6 µm, with an average size of ~3 µm (

Figure 3b). The size of the plates on the surface ranges from 0.4 to 0.8 µm (

Figure 3a). This hierarchical structure is consistent with the anisotropic crystal growth of Cu

2(OH)PO

4 in the hydrothermal synthesis method described in reference [

28].

The cuboid aggregate morphology with lamellar crystallites of the copper hydroxyphosphate particle surface provides a large specific area, ensuring particle adhesion to the epoxy matrix through mechanical interlocking. Additionally, this stepped, hierarchical structure should ensure the local absorption and distribution of energy during femtosecond ablation, creating local hot spots and changes in porosity and defect density. This will potentially affect the ablation threshold and the morphology of the formed relief [

37,

38].

The analysis of XRD copper hydroxyphosphate powders (

Figure 4) shows that diffractogram corresponding to the diffraction pattern of Cu

2(OH)PO

4 as reported [

28,

32,

39,

40]. All the peaks can be referred to libethenite (orthorhombic copper hydroxyphosphate) [

32].

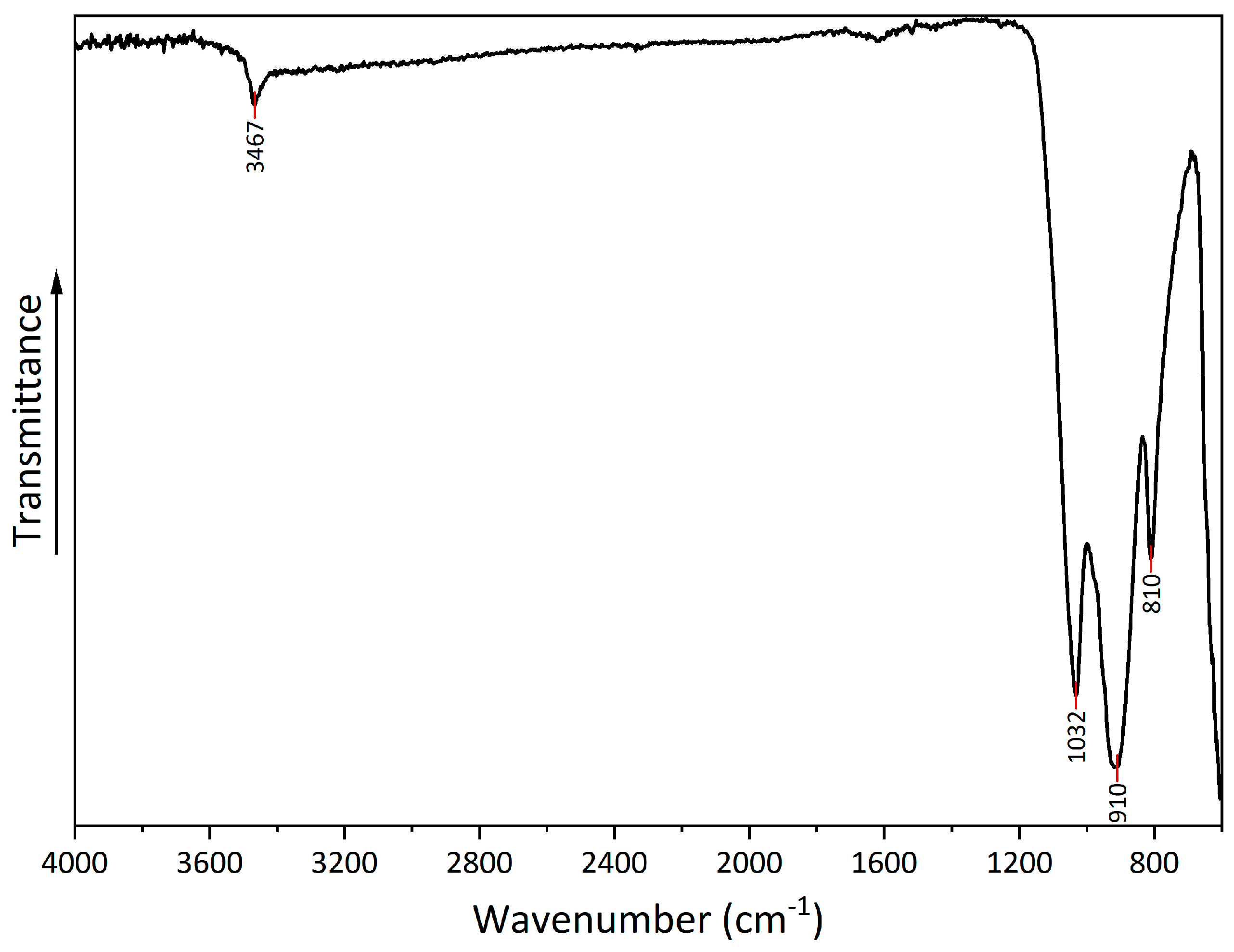

The FTIR spectrum (

Figure 5) shows a number of peaks that can be attributed to copper hydroxyphosphate. At 3467 cm

-1, there is a peak from the OH bond, which corresponds to adsorbed water. Additionally, at 1620 cm

-1, there is a low-intensity peak, which corresponds to the bending of the OH bond. A series of peaks at 1032, 910, and 810 cm

-1 can be attributed to symmetric stretching vibrations of (PO

4)

3- [

41,

42].

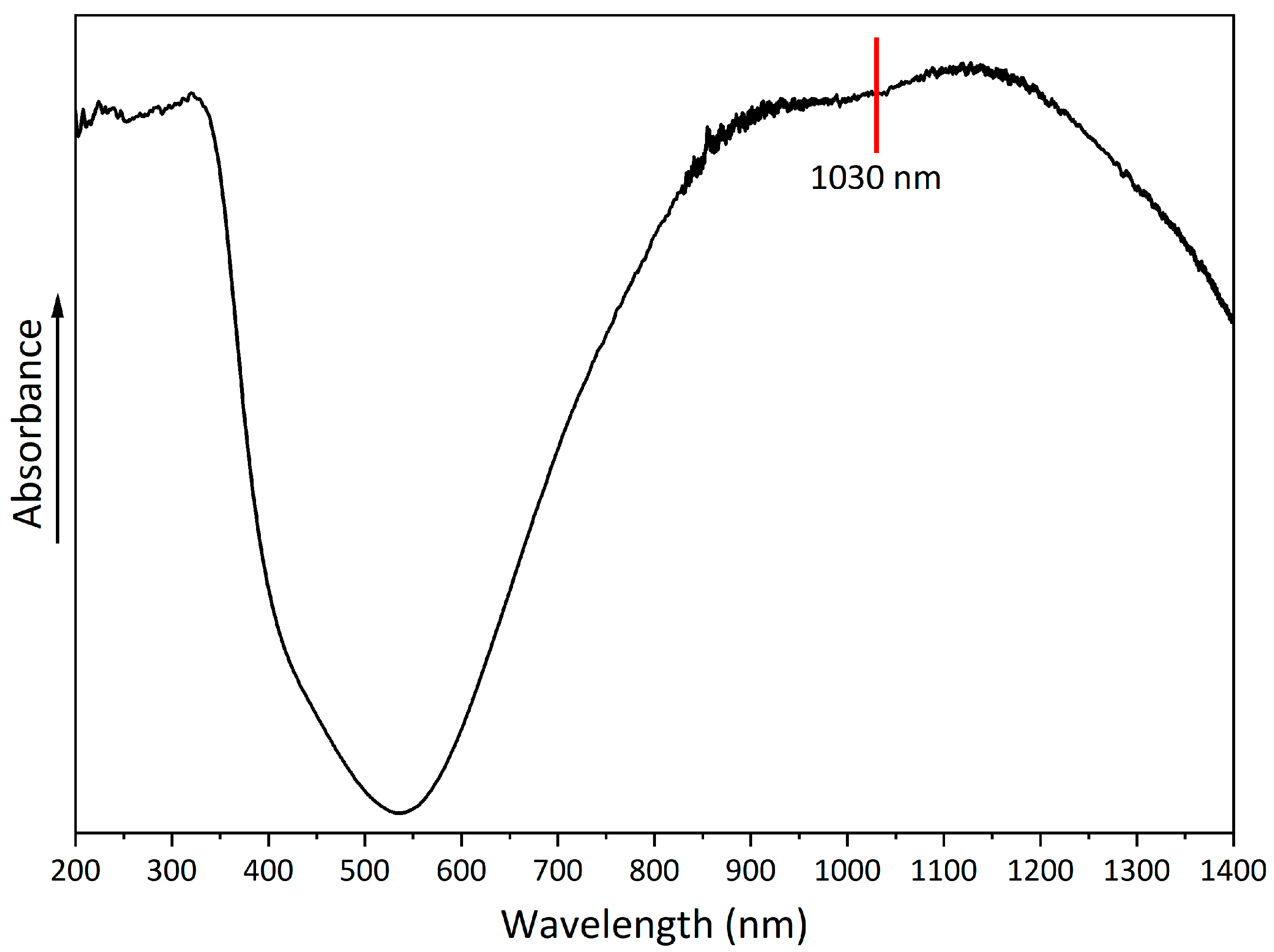

A UV-ViS-NIR spectrum was obtained to evaluate the absorption properties of copper hydroxyphosphate (

Figure 6). The spectrum shows a broad absorption band with a peak at 530-540 nm. In the 850-1250 nm range, there is absorption in the near-infrared region of the spectrum, which indicates the possible use of copper hydroxyphosphate as an additive for absorbing laser radiation [

43].

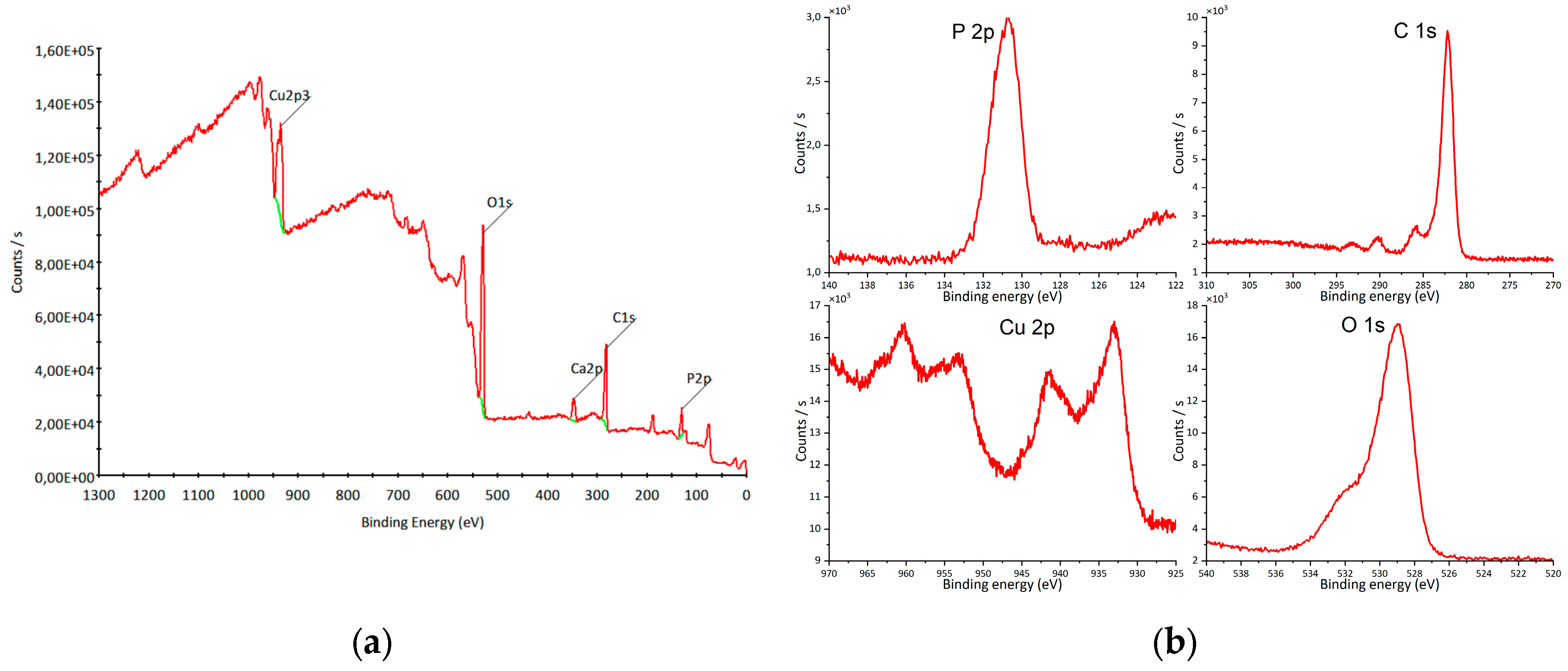

XPS analysis was performed to examine the elemental composition and chemical states of O, P, and Cu (

Figure 7a). The peak at 130 eV corresponds to P 2p (

Figure 7b), confirming the presence of P

5+ [

44,

45]. The Cu 2p region exhibits peaks at 933 eV (2p

3/2) and 953 eV (2p

1/2) (

Figure 7b), characteristic of Cu

+ [

46], together with shake-up satellite peaks at 943 eV and 963 eV (

Figure 7b), indicative of Cu

2+ species [

47,

48]. The O 1s peak at 529 eV (

Figure 7b) corresponds to lattice oxygen [

49]. The overall spectral features are consistent with previously reported copper hydroxyapatite spectra [

32,

50].

3.2. Femtosecond Laser Ablation Efficiency

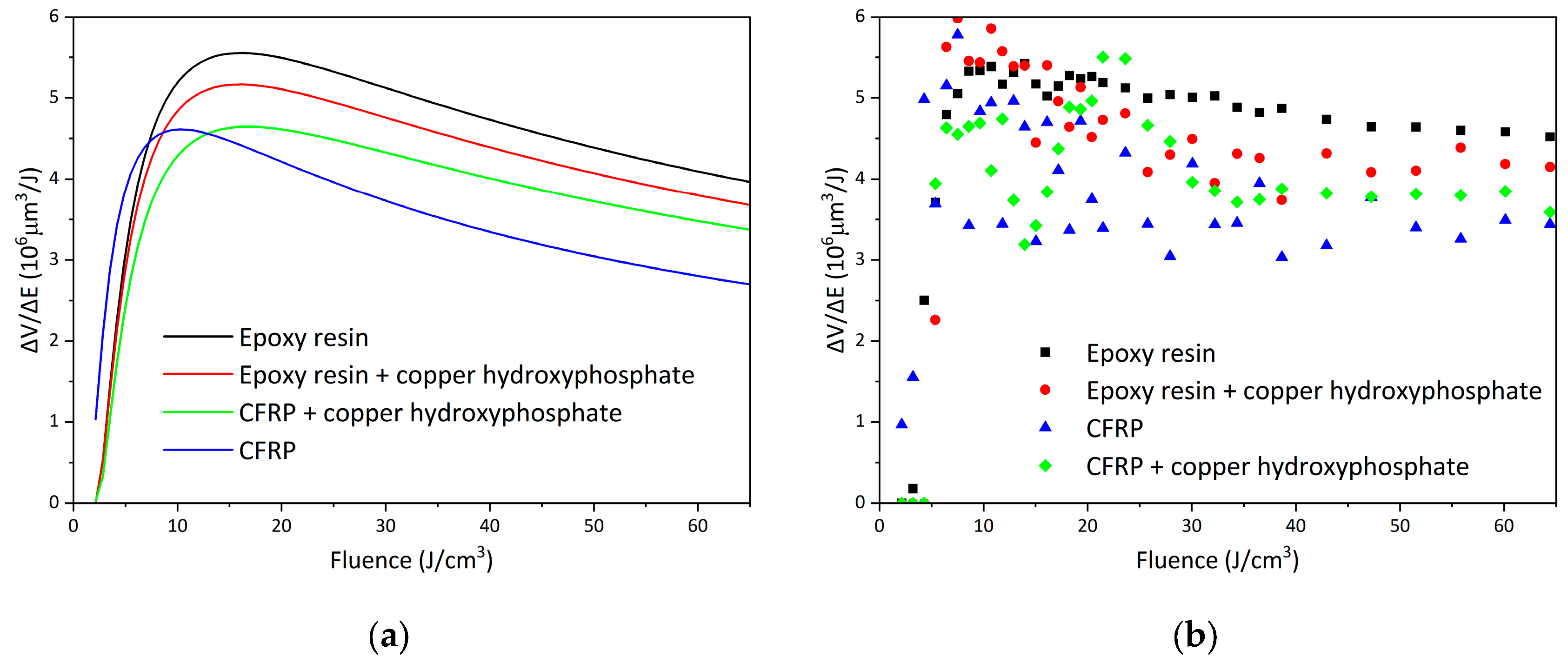

The efficiency curves of femtosecond laser ablation for epoxy and CFRP systems are presented on

Figure 8, and the corresponding fitted parameters are summarized in

Table 1. For neat epoxy resin, the maximum efficiency of 5.55 × 106 μm

3/J is achieved at an optimal fluence of 16.09 J/cm

3, which is the highest among all studied samples. The addition of copper hydroxyphosphate particles to the epoxy resin reduces the efficiency to 4.65 × 106 μm

3/J (a decrease of ~16.2%) at a similar optimal fluence of 16.76 J/cm

3. This reduction is also reflected in the fitted energy penetration depth (δ), which decreases from 44.68 to 38.94 μm.

In contrast, the neat CFRP exhibits lower ablation efficiency, reaching only 4.61 × 106 μm3/J at an optimal fluence of 10.31 J/cm3, with a penetration depth of 23.77 μm. The incorporation of copper hydroxyphosphate into CFRP, however, leads to an opposite trend: the efficiency increases by ~10.8%, reaching 5.17 × 106 μm3/J at an optimal fluence of 15.98 J/cm3, accompanied by a significant increase in δ to 41.28 μm. This indicates that copper hydroxyphosphate not only enhances the laser–material interaction but also improves the stability of the ablation process in heterogeneous fiber-reinforced composites.

Analysis of the non-approximated data confirms that ablation volumes in CFRP strongly depend on fiber distribution, resulting in higher variability. In contrast, homogeneous systems yield more stable and reproducible values. Thus, while the addition of copper hydroxyphosphate decreases the efficiency of laser ablation in pure epoxy resin, it plays a beneficial role in CFRP, improving efficiency and processing uniformity.

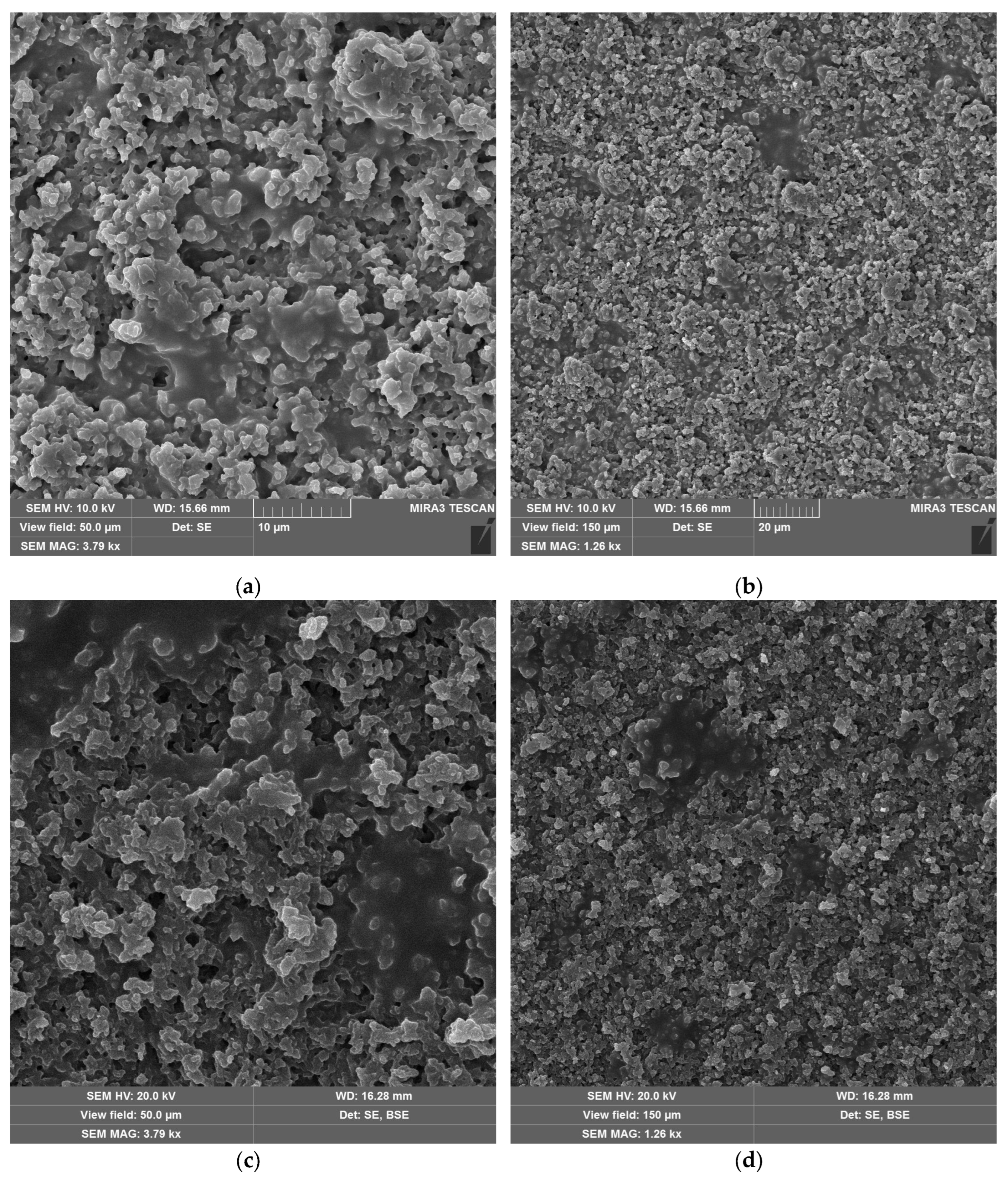

3.3. Morphological Changes of Materials

SEM micrographs of the laser-treated samples at the optimal fluence values for maximum efficiency are shown in

Figure 9. For neat epoxy resin (

Figure 9a,b) and epoxy resin containing copper hydroxyphosphate (

Figure 9c,d), the laser irradiation produces an irregular porous morphology on the epoxy matrix. The epoxy + copper hydroxyphosphate sample exhibit smoother regions with fewer damaged areas and reduced porosity compared to neat epoxy.

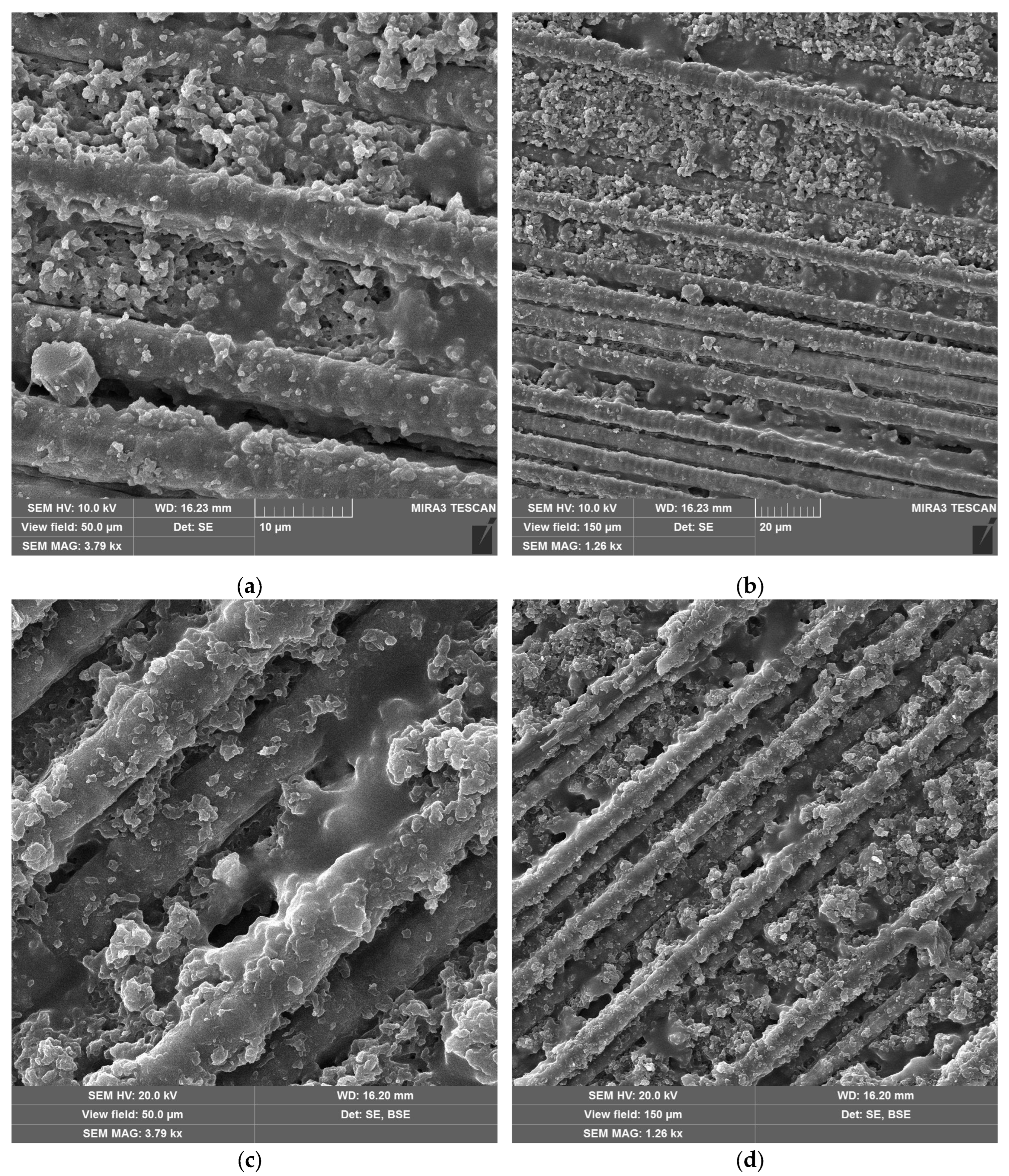

SEM images of CFRP without (

Figure 10a,b) and with copper hydroxyphosphate (

Figure 10c,d) demonstrate that laser ablation exposes the carbon fibers. The addition of copper hydroxyphosphate leads to more uniform ablation. At low magnification, the additive containing sample has more consistently covered fibers with epoxy resin residues, while the sample without additive has some fibers completely exposed. Additionally, SEM images of exposed carbon fibers revealed the formation of laser-induced periodic surface structures (LIPSS), consistent with previous reports [

15] obtained using a 1064 nm laser. Such structures are characteristic of ultrashort pulse laser processing and are known to depend on irradiation wavelength, incidence angle, beam polarization, and fluence [

51].

The EDS analysis (

Table 2) shows changes in the surface composition of epoxy- and CFRP-based samples before and after femtosecond laser ablation. For neat epoxy, ablation increases carbon (from 57.1% to 59.1%) and decreases oxygen (from 29.6% to 26.1%) and nitrogen (from 13.3% to 11.3%). This suggests decomposition of the polymer matrix and oxygen loss due to localized heating [

52,

53]. In epoxy resin containing copper hydroxyphosphate, the surface after ablation shows an increase in carbon (from 63.3% to 65.9%) and a decrease in oxygen (from 26.9% to 24.8%), similar to a neat epoxy sample. Copper content slightly decreases from 1.9% to 1.6%, indicating redistribution or possible removal of copper hydroxyphosphate particles during ablation.

For neat CFRP, laser treatment reduces the nitrogen concentration significantly (from 13.6% to 9.5%) while oxygen slightly increases (from 25.8% to 27.7%). The carbon fraction remains almost unchanged, consistent with exposure of carbon fibers and partial oxidation of the surrounding epoxy matrix [

54]. In CFRP with copper hydroxyphosphate additive, carbon content remains stable (from 63.8% to 64.0%), whereas oxygen decreases (from 26.6% to 25.5%). At the same time, copper increases from 1.3% to 1.8% after ablation, which may be related to better retention or exposure of copper hydroxyphosphate particles on the surface under the influence of femtosecond laser radiation. The data show that femtosecond laser processing increases carbon and reduces oxygen in epoxy-based systems, while in CFRP, the process is influenced by fiber exposure and copper hydroxyphosphate redistribution.

4. Discussion

The copper hydroxyphosphate particles with cuboid microaggregates and stepped plate-like structures have hierarchical morphology that increases surface area, enhancing adhesion between the epoxy resin and the particles. The particles effectively absorb the 1030 nm laser radiation used in this study, converting it into localized heat.

The introduction of copper hydroxyphosphate into the epoxy resin led to a slight decrease in ablation efficiency, reflected in the reduced penetration depth (δ) from 44.7 to 38.9 μm. This is due to the absorption of part of the incident laser energy by copper hydroxyphosphate particles. Instead of contributing to volumetric material removal, part of the energy is dissipated as local heating of the resin and subsequent thermal decomposition. Thus, in neat epoxy resin, copper hydroxyphosphate acts as an additional energy absorber, lowering the net intensity of ablation. SEM micrographs support this interpretation: the surfaces treated with copper hydroxyphosphate show less pronounced porosity and fewer localized defects, which are distributed more evenly compared to the neat epoxy. This correlation between morphology and reduced efficiency highlights a trade-off between surface quality and volumetric removal rate.

For neat CFRP, ablation efficiency remained relatively low, with a penetration depth of ~23.8 μm. This is consistent with the heterogeneous nature of the composite: carbon fibers and the epoxy matrix differ in their optical absorption and thermal responses, which leads to highly variable ablation behavior [

55,

56,

57]. Such structural heterogeneity is one of the key limitations for stable femtosecond laser processing of CFRPs.

Adding copper hydroxyphosphate to CFRP increased penetration depth to 41.3 μm, while the scatter in efficiency values was reduced. This suggests that copper hydroxyphosphate modifies the interaction between the epoxy matrix and the carbon fibers, enabling more uniform absorption of laser energy. As a result, the ablation process becomes more stable and less dependent on local fiber distribution. SEM images confirm this effect: in CFRP + copper hydroxyphosphate samples, carbon fibers are less frequently fully exposed, and resin residues remain more consistently covering the fibers. This indicates that copper hydroxyphosphate facilitates controlled and homogeneous matrix removal, which directly translates into higher quality cuts.

Elemental analysis shows that neat epoxy resin has more carbon after laser processing, accompanied by oxygen depletion, a typical signature of polymer decomposition under high-intensity irradiation. In CFRP systems, the changes in elemental composition are less pronounced and appear primarily influenced by the redistribution of resin and copper hydroxyphosphate around the fiber network. This again reflects the stabilizing role of the additive in balancing the matrix–fiber interactions under laser exposure.

Overall, copper hydroxyphosphate is an effective absorber of laser energy; its influence depends on the system. In pure epoxy, it reduces ablation efficiency but improves surface quality. In CFRP, it plays a more critical role: it homogenizes the energy distribution, mitigates the heterogeneity of fiber–matrix interactions, and enhances penetration depth and uniformity of ablation. These results demonstrate that incorporating copper hydroxyphosphate can improve the precision and quality of femtosecond laser processing of CFRPs, offering an efficient and defect-free laser cutting of advanced composites.

5. Conclusions

The copper hydroxyphosphate particles were successfully synthesized in the form of cuboid aggregates with stepped plates. Their hierarchical structure increases the specific surface area and ensures strong interfacial interaction with the epoxy matrix. Structural analysis confirmed the phase as copper hydroxyphosphate – libethenite, and optical characterization demonstrated its ability to absorb laser radiation at 1030 nm. In epoxy resin, copper hydroxyphosphate reduced the ablated volume (−16% efficiency) and penetration depth due to enhanced surface absorption and localized heating. Laser-treated surfaces exhibited smoother morphology, reduced porosity, and more uniform matrix degradation. For CFRP, the additive had a positive effect: ablation efficiency and penetration depth increased, while data variability decreased. SEM observations confirmed more homogeneous matrix removal and better preservation of resin residues on carbon fibers, which resulted in improved process stability and cut quality. Overall, copper hydroxyphosphate acts as an effective laser-absorbing additive that enhances the uniformity and accuracy of CFRP laser cutting, contributing to the development of advanced composite machining technologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.M., E.V. and P.Š.; methodology, D.B., O.M., E.V. and P.Š.; software, P.Š. and O.U.; validation, O.M. and E.V.; formal analysis, D.B. and S.O.; investigation, D.B., A.B., P.Š., O.U. and J.M.; resources, O.M., P.Š., O.U. and S.O.; data curation, D.B., P.Š., O.U. and J.M.; writing—original draft preparation, D.B.; writing—review and editing, D.B. and O.M.; visualization, D.B., P.Š., O.U. and J.M.; supervision, O.M. and E.V.; project administration, O.M. and E.V.; funding acquisition, O.M. and E.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research and APC were funded by the Research Council of Lithuania, grant number P-LU-24-46, and by the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine, agreement number M/50-2024, reg. number 0124U003362.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT, version GPT-5 for icon creation in scheme of copper hydroxyphosphate synthesis procedure (Figure 1). The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.”

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CFRP |

Carbon fiber reinforced plastic |

| HAZ |

Heat-affected zone |

| fs |

Femtosecond |

| FTIR |

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy |

| XPS |

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy |

| XRD |

X-ray diffraction |

| UV-VIS-NIR |

Ultraviolet/Visible/Near Infrared spectroscopy |

References

- Karataş, M.A.; Gökkaya, H. A Review on Machinability of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymer (CFRP) and Glass Fiber Reinforced Polymer (GFRP) Composite Materials. Defence Technology 2018, 14, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.; Kumar, A.; Rana, S.; Guadagno, L. An Overview on Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Epoxy Composites: Effect of Graphene Oxide Incorporation on Composites Performance. Polymers 2022, 14, 1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, S.; Shenoy, B.S.; Chethan, K.N. Review on Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymer (CFRP) and Their Mechanical Performance. Materials Today Proceedings 2019, 19, 658–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.L.; Zhang, C.; Chen, X.; Zheng, D. Galvanic Activity of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymers and Electrochemical Behavior of Carbon Fiber. Corrosion Communications 2021, 1, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, D.S.; Sivasuriyan, A.; Devarajan, P.; Stefańska, A.; Wodzyński, Ł.; Koda, E. Carbon Fibre-Reinforced Polymer (CFRP) Composites in Civil Engineering Application—A Comprehensive Review. Buildings 2023, 13, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, A.M.; Górny, T.; Dopierała, Ł.; Paczos, P. The Use of CFRP for Structural Reinforcement—Literature Review. Metals 2022, 12, 1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atescan-Yuksek, Y.; Mills, A.; Ayre, D.; Koziol, K.; Salonitis, K. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Aluminium and CFRP Composites: The Case of Aerospace Manufacturing. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2024, 131, 4345–4357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaśkiewicz, R. Comparison of Composite Laminates Machining Methods and Its Influence on Process Temperature and Edge Quality. Transactions of the Institute of Aviation 2019, 2019, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartal, F. Abrasive Water Jet Machining of Carbon Fiber-Reinforced PLA Composites: Optimization of Machinability and Surface Integrity for High-Precision Applications. Polymers 2025, 17, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Cheng, X.; Wang, J.; Sheng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.; Jing, C.; Sun, S.; Xia, H.; Ru, H. A Review of Research Progress on Machining Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Composites with Lasers. Micromachines 2022, 14, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Guo, B.; Jiang, L.; Liu, Z.; Qian, Q. Analysis and Optimization of the Heat Affected Zone of CFRP by Femtosecond Laser Processing. Optics & Laser Technology 2023, 167, 109756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Ma, Z.; Sun, J.; Zhu, L. Femtosecond Laser Drill High Modulus CFRP Multidirectional Laminates with a Segmented Arc-Based Concentric Scanning Method. Composite Structures 2023, 329, 117769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Ma, C.; Li, M.; Cao, Z. Femtosecond Laser Drilling of Cylindrical Holes for Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polymer (CFRP) Composites. Molecules 2021, 26, 2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Huang, M.; Dong, L. Comparison of the Effects of Femtosecond and Nanosecond Laser Tailoring on the Bonding Performance of the Heterojunction between PEEK/CFRP and Al–Li Alloy. International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives 2023, 126, 103483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebauer, J.; Burkhardt, M.; Franke, V.; Lasagni, A.F. On the Ablation Behavior of Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Plastics during Laser Surface Treatment Using Pulsed Lasers. Materials 2020, 13, 5682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Ma, Y.; Yuan, B.; Wu, C.; Li, C.; Sun, S. Development of Laser Processing Carbon-Fiber-Reinforced Plastic. Sensors 2023, 23, 3659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, M.; Ohkawa, H.; Somekawa, T.; Otsuka, M.; Maeda, Y.; Matsutani, T.; Miyanaga, N. Wavelength and Pulsewidth Dependences of Laser Processing of CFRP. Physics Procedia 2016, 83, 1031–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.P.; Vilar, R. Femtosecond Laser Micromachining of Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Epoxy Matrix Composites. Journal of Manufacturing Processes 2022, 84, 1568–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Ren, Y.; Li, W.; Li, S.; Chai, N.; Zeng, Z.; Chen, X.; Yue, Y.; Zhou, L.; et al. Passive Deicing CFRP Surfaces Enabled by Super-Hydrophobic Multi-Scale Micro-Nano Structures Fabricated via Femtosecond Laser Direct Writing. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, P.; Liu, T.; Li, F.; Wang, G.; Zhang, K.; Li, X.; Han, W.; Tian, H.; Hu, L.; Huang, H.; et al. Controllable Fabrication of Hydrophilic Surface Micro/Nanostructures of CFRP by Femtosecond Laser. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 20988–20996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Bi, R.; Jiang, S.; Wen, Z.; Luo, C.; Yao, J.; Liu, G.; Chen, C.; Wang, M. Laser Ablation Mechanism and Performance of Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Poly Aryl Ether Ketone (PAEK) Composites. Polymers 2022, 14, 2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.Y.; Lu, J.R.; Li, K.M.; Hu, J. Experimental Study of CFRP Laser Surface Modification and Bonding Characteristics of CFRP/Al6061 Heterogeneous Joints. Composite Structures 2021, 283, 115030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kononenko, T.V.; Freitag, C.; Komlenok, M.S.; Onuseit, V.; Weber, R.; Graf, T.; Konov, V.I. Oxygen-Assisted Multipass Cutting of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Plastics with Ultra-Short Laser Pulses. Journal of Applied Physics 2014, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, H.; Diboine, J.; Chingwena, K.; Mason, B.; Marimuthu, S. Water Jet Guided Nanosecond Laser Cutting of CFRP. Optics & Laser Technology 2023, 171, 110460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, J.; Zaeh, M.F.; Conrad, M. Remote Laser Cutting of CFRP: Improvements in the Cut Surface. Physics Procedia 2012, 39, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Barrado, E.; Darton, R.J. Synthesis and Applications of Near-Infrared Absorbing Additive Copper Hydroxyphosphate. MRS Communications 2018, 8, 1070–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Wang, R.; Wu, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, A.; Zhang, Z.; Qiu, S. Synthesis of Cu2(OH)PO4 Crystals with Various Morphologies and Their Catalytic Activity in Hydroxylation of Phenol. Chemistry Letters 2013, 42, 772–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Xue, D. Fabrication of Copper Hydroxyphosphate with Complex Architectures. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2006, 110, 7750–7756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Teng, F.; Xu, J.; Liu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Yao, W. Facile Synthesis of Cu2PO4OH Hierarchical Nanostructures and Their Improved Catalytic Activity by a Hydroxyl Group. RSC Advances 2015, 5, 100934–100942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X. Hydrothermal Synthesis of Copper Hydroxyphosphate Hierarchical Architectures. Chemical Engineering & Technology 2012, 35, 2189–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othmani, M.; Bachoua, H.; Ghandour, Y.; Aissa, A.; Debbabi, M. Synthesis, Characterization and Catalytic Properties of Copper-Substituted Hydroxyapatite Nanocrystals. Materials Research Bulletin 2017, 97, 560–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Jiao, X.; Chen, D. Hydrothermal Synthesis and Characterization of Copper Hydroxyphosphate Hierarchical Superstructures. Journal of Dispersion Science and Technology 2011, 32, 591–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Li, P.; Zhang, W.; Che, Y.; Sun, Y.; Chi, F.; Ran, S.; Liu, X.; Lv, Y. Effect of Cupric Salts (Cu (NO3)2, CuSO4, Cu(CH3COO)2) on Cu2(OH)PO4 Morphology for Photocatalytic Degradation of 2,4-Dichlorophenol under Near-Infrared Light Irradiation. Materials Research 2017, 20, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šlevas, P.; Minkevičius, J.; Ulčinas, O.; Orlov, S.; Vanagas, E.; Bilousova, A.; Baklan, D.; Myronyuk, O. An Investigation of Carbon-Fiber-Reinforced Plastic Ablation by Femtosecond Laser Pulses for Further Material Cutting. Coatings 2025, 15, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förster, D.J.; Jäggi, B.; Michalowski, A.; Neuenschwander, B. Review on Experimental and Theoretical Investigations of Ultra-Short Pulsed Laser Ablation of Metals with Burst Pulses. Materials 2021, 14, 3331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuenschwander, B.; Kramer, Th.; Lauer, B.; Jaeggi, B. Burst Mode with Ps- and Fs-Pulses: Influence on the Removal Rate, Surface Quality, and Heat Accumulation. Proceedings of SPIE, the International Society for Optical Engineering/Proceedings of SPIE 2015, 9350, 93500U. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Peng, J.; Cai, Z.; Weng, J.; Luo, Z.; Chen, N.; Xu, H. Gold Nanoparticles as a Saturable Absorber for Visible 635 Nm Q-Switched Pulse Generation. Optics Express 2015, 23, 24071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrebdi, T.A.; Sadiq, S.; Tian, S.-C.; Asghar, M.; Saghir, I.; Asghar, H. Applications of Prepared MnMoO4 Nanoparticles as Saturable Absorbers for Q-Switched Erbium-Doped Fiber Lasers: Experimental and Theoretical Analysis. Photonics 2025, 12, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, I.; Kim, D.W.; Lee, S.; Kwak, C.H.; Bae, S.; Noh, J.H.; Yoon, S.H.; Jung, H.S.; Kim, D.; Hong, K.S. Synthesis of Cu2PO4OH Hierarchical Superstructures with Photocatalytic Activity in Visible Light. Advanced Functional Materials 2008, 18, 2154–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, Y. Copper Hydroxyphosphate as Catalyst for the Wet Hydrogen Peroxide Oxidation of Azo Dyes. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2010, 180, 481–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, A.Q.; Liao, S.; Tong, Zh.F.; Wu, J.; Huang, Z.Y. Synthesis of Nanoparticle Zinc Phosphate Dihydrate by Solid State Reaction at Room Temperature and Its Thermochemical Study. Materials Letters 2006, 60, 2110–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klähn, M.; Mathias, G.; Kötting, C.; Nonella, M.; Schlitter, J.; Gerwert, K.; Tavan, P. IR Spectra of Phosphate Ions in Aqueous Solution: Predictions of a DFT/MM Approach Compared with Observations. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 2004, 108, 6186–6194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, J.; Schulz, A.; Olowinsky, A.; Dohrn, A.; Poprawe, R. Laser Welding of Laser-Structured Copper Connectors for Battery Applications and Power Electronics. Welding in the World 2020, 64, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Gong, K.; Zhao, G.; Lou, W.; Wang, X.; Liu, W. Mechanical Synthesis of Chemically Bonded Phosphorus–Graphene Hybrid as High-Temperature Lubricating Oil Additive. RSC Advances 2018, 8, 4595–4603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Shang, Y.; Chen, H.; Cao, S.; Zhu, Q.; Liu, S.; Wei, S.; Lu, X. Toward Highly Active Electrochemical CO2 Reduction to C2H4 by Copper Hydroxyphosphate. Journal of Solid State Electrochemistry 2023, 27, 1279–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesinger, M.C. Advanced Analysis of Copper X-ray Photoelectron Spectra. Surface and Interface Analysis 2017, 49, 1325–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Pan, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Cao, Y.; Su, C.; Gao, P.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, G.; Wang, Q.; et al. Room-Temperature Synthesis of Nonstoichiometric Copper Sulfide (Cu2−xS) for Sodium Ion Storage. Inorganic Chemistry Frontiers 2024, 11, 3811–3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, P.V.F.; De Oliveira, A.F.; Da Silva, A.A.; Lopes, R.P. Environmental Remediation Processes by Zero Valence Copper: Reaction Mechanisms. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2019, 26, 14883–14903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sydorchuk, V.; Poddubnaya, O.I.; Tsyba, M.M.; Zakutevskyy, O.; Khyzhun, O.; Khalameida, S.; Puziy, A.M. Photocatalytic Degradation of Dyes Using Phosphorus-Containing Activated Carbons. Applied Surface Science 2020, 535, 147667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.Y.; Lu, S.T.; Li, Y.Y.; Li, C.; Cao, K.Z.; Fan, Y. Copper Hydroxyphosphate Cu2(OH)PO4 as Conversion-Type Anode Material for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Ionics 2023, 29, 2209–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, V.; Sharma, S.P.; De Moura, M.F.S.F.; Moreira, R.D.F.; Vilar, R. Surface Treatment of CFRP Composites Using Femtosecond Laser Radiation. Optics and Lasers in Engineering 2017, 94, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhumanazarova, G.M.; Sarsenbekova, A.Zh.; Abulyaissova, L.K.; Figurinene, I.V.; Zhaslan, R.K.; Makhmutova, A.S.; Sotchenko, R.K.; Aikynbayeva, G.M.; Hranicek, J. Study of Mathematical Models Describing the Thermal Decomposition of Polymers Using Numerical Methods. Polymers 2025, 17, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.; Cooney, R.P. Thermal Degradation of Polymer and Polymer Composites. In Elsevier eBooks; 2012; pp. 213–242.

- Yatim, N.M.; Shamsudin, Z.; Shaaban, A.; Sani, N.A.; Jumaidin, R.; Shariff, E.A. Thermal Analysis of Carbon Fibre Reinforced Polymer Decomposition. Materials Research Express 2020, 7, 015615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALYousef, J.; Yudhanto, A.; Tao, R.; Lubineau, G. Laser Ablation of CFRP Surfaces for Improving the Strength of Bonded Scarf Composite Joints. Composite Structures 2022, 296, 115881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Bai, J.; Wang, F.; Qian, L. Performance and Mechanisms of Ultraviolet Laser Ablation of Plain-Woven CFRP Composites. Composite Structures 2023, 328, 117744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, L.; Yang, W.; Wang, W.; Wang, D.; Li, Z.; Teng, Z. Layer Ablation and Surface Textured of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Plastics by Infrared Pulsed Laser. Polymer Composites 2023, 45, 763–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).