1. Introduction

Jellyfish, the representative of cnidarians among plankton, are characterized by their remarkable species diversity and wide geographical distribution. As one of the most common venomous marine organisms, jellyfish stings can induce a broad spectrum of clinical symptoms, including localized pain, pruritus, erythema and edema. In severe cases, there may even be limb swelling, tachypnea, cardiac arrest and even death [

1,

2,

3]. Studies have shown that jellyfish toxins exhibit diverse toxic effects including neurotoxicity, myotoxicity, hemolytic activity, and a wide range of other biological activities [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. However, due to the instability of jellyfish toxins, the research on jellyfish venom obviously lags behind that on the venoms derived from other common toxic animals, and its precise composition and mechanisms of action remain still unclear [

10].

Nematocysts, featuring robust capsule walls, are a type of sac-like organelles unique to cnidarians. They integrate sensory and secretory functions while playing pivotal roles in predation, defense, and locomotion [

11,

12]. To date, more than 30 types of nematocysts have been identified in cnidarians [

13,

14], which can be functionally classified into four categories [

15]. The first category is responsible for prey immobilization; the second category facilitates prey penetration while simultaneously injecting venom - these two categories of nematocysts cooperate to complete the predation process and can be collectively referred to as predatory nematocysts [

16]; the third category is associated with locomotion, enabling adhesion to other marine organisms or substrate surfaces to assist movement; and the fourth category serves defensive purposes. Based on the morphological classification [

17,

18], nematocysts can be divided into open-thread type and closed-thread type according to whether the top of thread is open. The open-thread type can be further categorized into nematocysts with a central axis thread and those without a central axis thread. The former includes euryteles, mastigophores, stenoteles, etc., and the latter includes isorhizas (such as O-isorhizas, etc.) and Anisorhizas, etc.

The nematocysts of jellyfish exhibit remarkable diversity according to their morphological characteristics and biological functions, and their venomous contents are highly complex, predominantly comprising protein/peptide toxins [

19,

20]. However, the current researches on the components and effects of monomorphic nematocysts remain relatively limited, with most investigations focusing on predatory nematocysts (penetrating/venom-injecting types) and their discharge mechanisms and toxic effects. For example, Brinkman et al. [

21] successfully isolated and purified two distinct types of nematocysts, mastigophores and a mixed sample of isorhizas with trirhopaloids, from

Chironex fleckeri. Through integrated transcriptomics and proteomic analysis of their contents, the study revealed significant compositional and functional relationships between these nematocyst subtypes. Notably, comparative analysis demonstrated minimal differences in the toxin profiles, providing novel insights into potential synergistic mechanisms underlying jellyfish nematocyst function. Wang et al. [

10] isolated and purified predatory nematocysts, namely isorhizas and mastigophores from

Cyanea capillata and

N. nomurai respectively. Through combined transcriptomic and proteomic analysis of their contents, the compositional differences between these predatory nematocysts were elucidated, thereby providing a molecular basis for understanding the underlying mechanisms of distinct jellyfish sting symptoms and developing targeted treatments. Nevertheless, except for predatory nematocysts, the research on other types of nematocysts is still largely confined to descriptive level, with their composition characteristics, bioactivities and functions remaining poorly characterized. Therefore, the isolation and purification of monomorphic nematocysts is of great importance for gaining deeper insights into the functional diversity of jellyfish nematocysts and advancing the prevention and treatment of jellyfish sting.

N. nomurai is a large toxic jellyfish commonly found in China seas, with a wide distribution and medical importance [

1,

2,

3,

22,

23]. Current research on

N. nomurai venom primarily adopts the method of direct extraction from the tentacles [

10,

21,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31], which not only risk toxin denaturation but also fail to elucidate specific nematocyst functions. The obtainment of monomorphic nematocysts enables precise characterization of specific nematocyst function while minimizing the variability between sample batches during toxin research. In this study, we isolated two monomorphic nematocysts from

N. nomurai tentacles, characterized their microstructures and discharge capacities, and subsequently analysed the toxic effects and bioactivities of their contents to explore the potential relationships between the morphological structures and biological functions thereby providing a deeper understanding of jellyfish nematocysts and their functional diversity.

3. Discussion

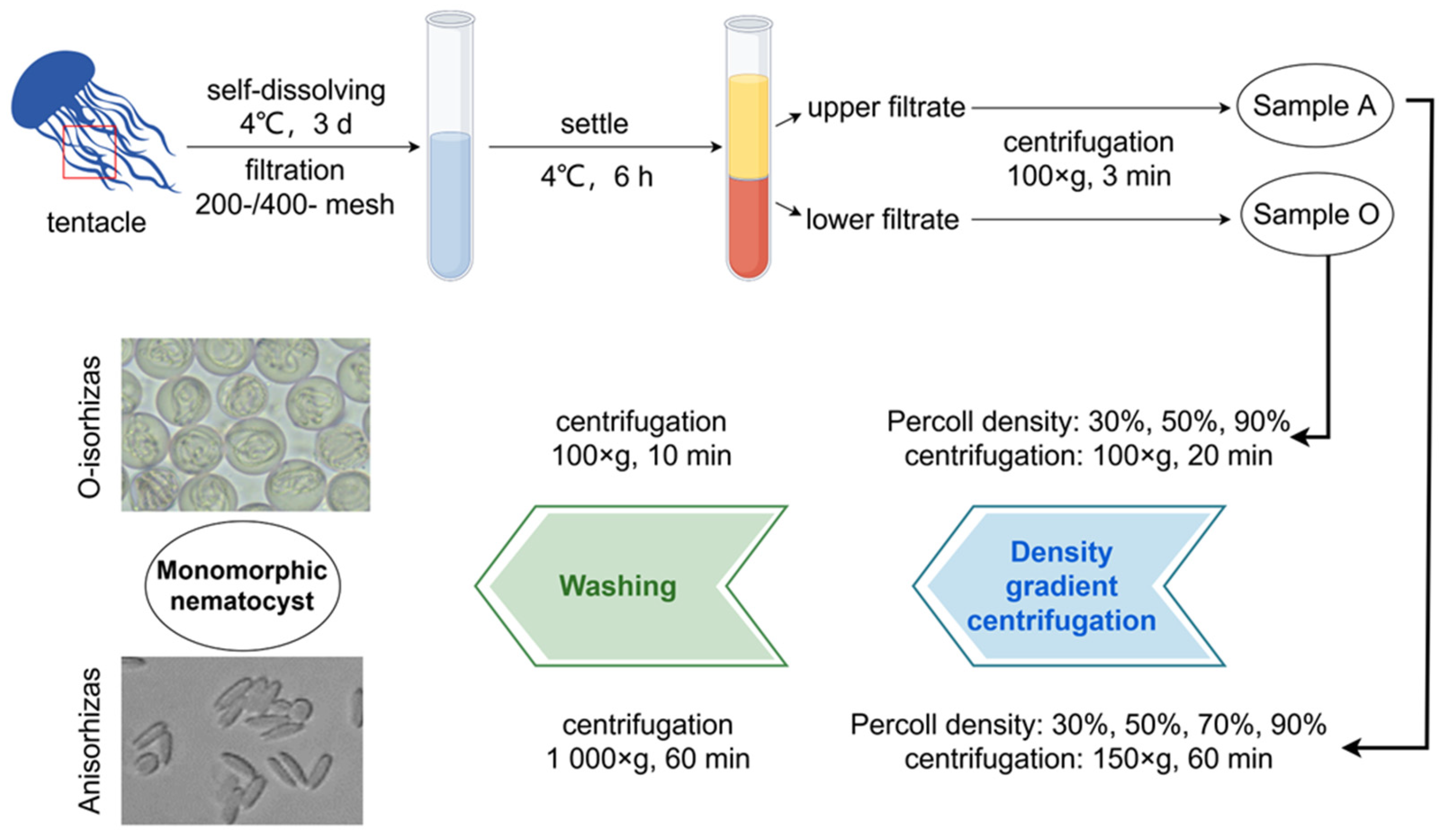

Jellyfish are common venomous marine organisms, characterized by their specialized nematocysts that serve as venom reservoirs for prey capture and defense. Compared to the toxic apparatuses of other venomous organisms, jellyfish nematocysts are diverse in types, presenting technical challenges for isolation due to their structural heterogeneity. A single nematocyst contains only a small amount of toxins, which is unstable and easy to inactivate. These factors delayed research on jellyfish venoms. Therefore, the isolation of monomorphic nematocyst is a prerequisite for investigating nematocyst classification, functional characteristics, and venom composition. In this study, we established an optimized density gradient centrifugation protocol for efficient isolation of monomorphic nematocysts from N. nomurai, yielding two distinct types of nematocysts: O-isorhizas and Anisorhizas. The purified nematocysts demonstrated morphological integrity and functional viability, as confirmed by microscopic examination and discharge assays.

O-isorhizas and Anisorhizas displayed significant differences in physical parameters including volume and diameter, which makes them particularly amenable for isolation via density gradient centrifugation. Taking Anisorhizas as an example, the optimized isolation protocol involves sequential steps: initial primary separation through collection of tentacle autolysis filtrates via centrifugation, followed by density gradient optimization, which is the key to obtain high-purity monomorphic nematocysts. Through comparative evaluation of the media including sucrose, Ficoll, and Percoll, we identified Percoll as the optimal medium due to its low osmolarity and viscosity, rapid gradient formation, easy removability through washing, and exceptional stability against temperature and pH fluctuations. The purification stage employs a discontinuous gradient of Percoll (30%, 50%, 70%, 90%, respectively) with centrifugation at 150×g for 60 minutes to yield high-purity Anisorhizas, which are subsequently subjected to seawater washes (1000×g, 60 minutes) for complete medium removal. Through this optimized protocol, we successfully obtained a large amount of Anisorhizas nematocysts of high purity.

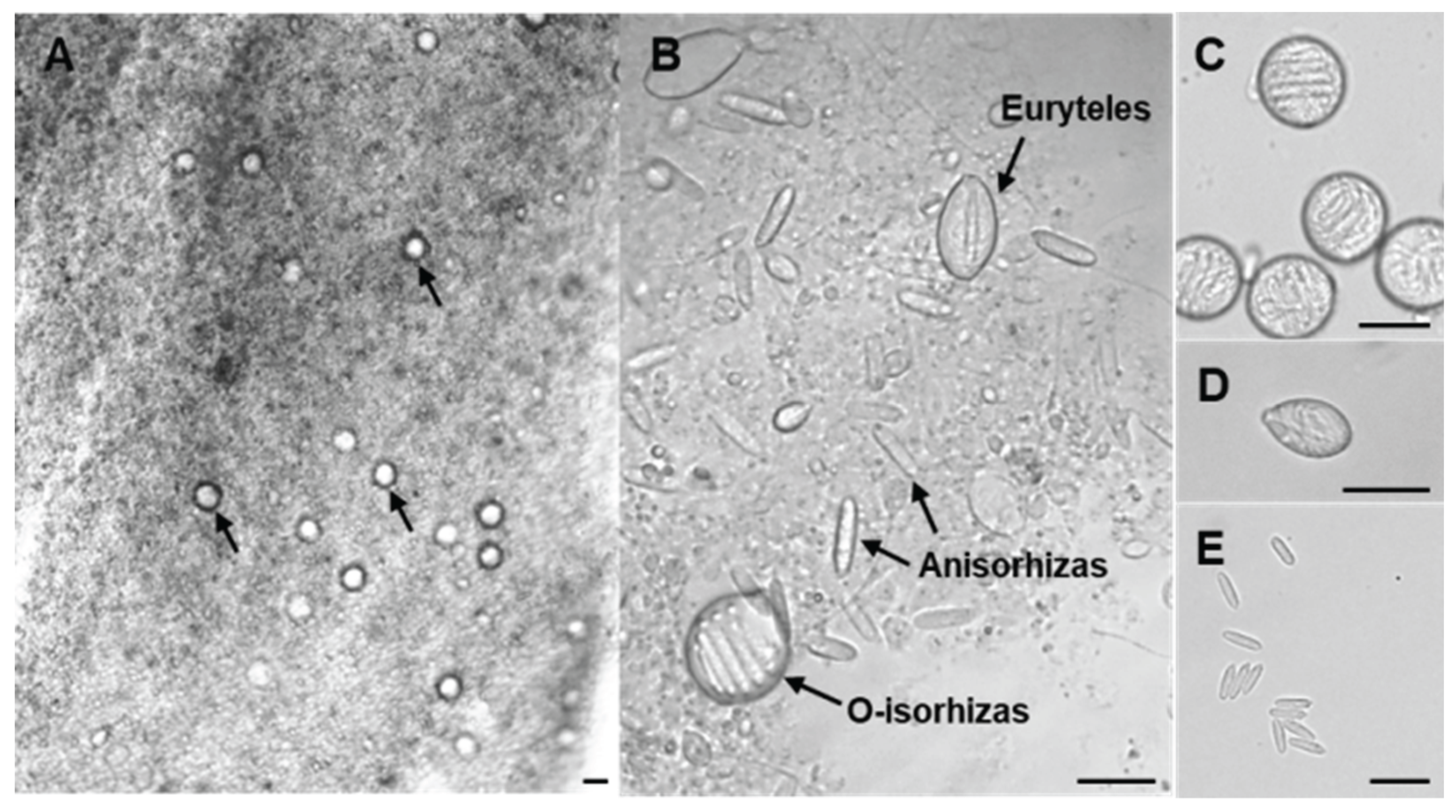

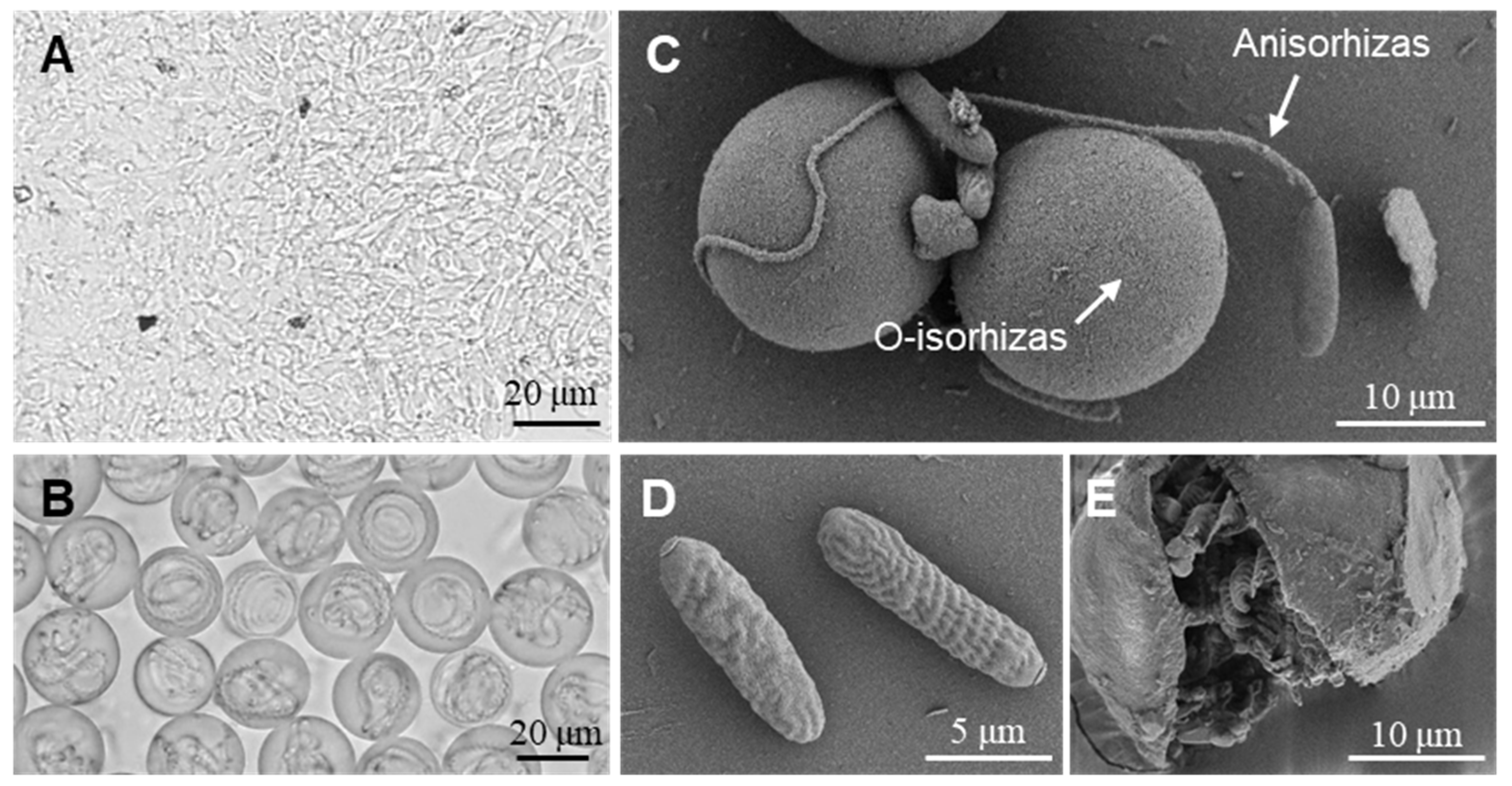

Microscopic observation revealed distinct morphological differences between the two nematocyst types. Compared with Anisorhizas, O-isorhizas has a larger volume, and the spread inside the capsule exhibits an obvious spiral structure. Both O-isorhizas and Anisorhizas could be induced to discharge through osmotic pressure changes, with O-isorhizas exhibiting greater discharge capability upon deionized water stimulation. These results indicate some correlation between the morphological structures and biological functions of nematocysts, suggesting that the spiral structure of the thread inside O-isorhizas and its large volume may endow O-isorhizas with superior discharge and penetrating abilities, enabling efficient accumulation and transfer of energy to promote rapid discharge of the thread, which can break through the defensive barriers of prey and natural enemies. Therefore, O-isorhizas likely serves as the primary offensive/defensive mechanism during jellyfish stinging. Although Anisorhizas demonstrate relatively weaker discharge ability compared to O-isorhizas, they appear to play a complementary role in the stinging process, potentially involved in coordinated venom delivery to enhance venom injecting effects and improve prey capture and defensive efficiency.

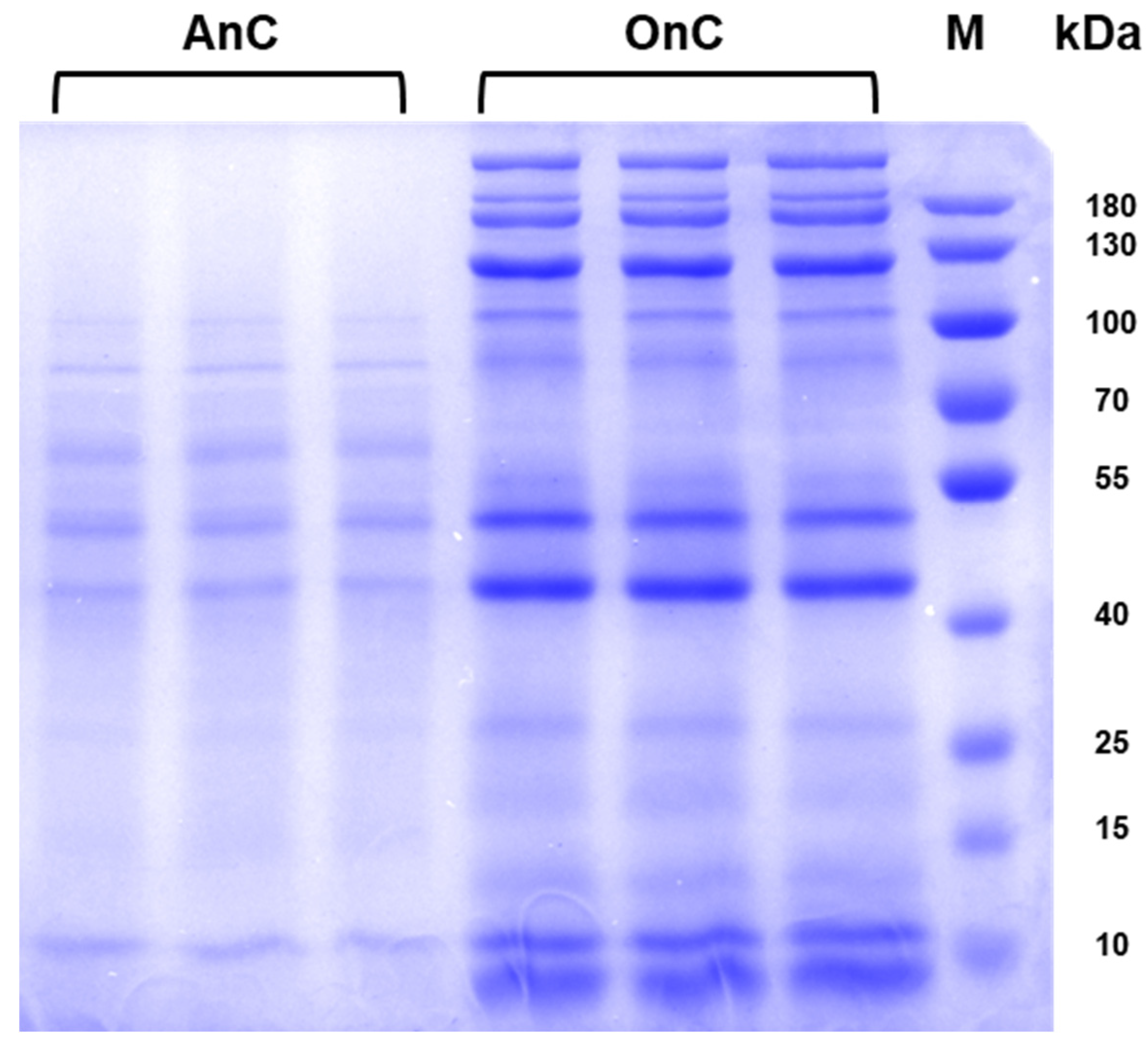

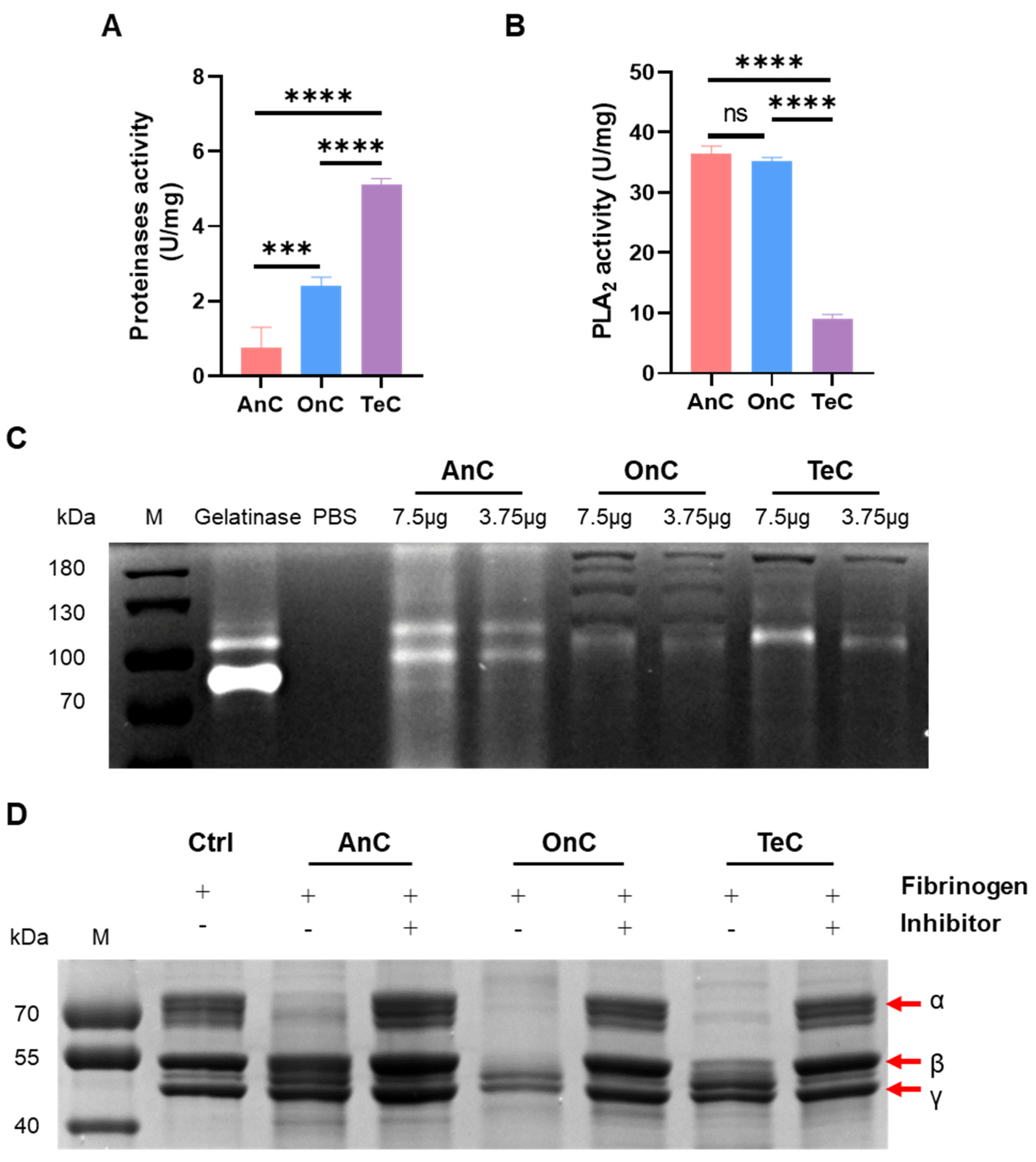

Through ultrasonication-mediated disruption, we successfully obtained the intracapsular contents from O-isorhizas and Anisorhizas. SDS-PAGE analysis revealed generally similar but distinct protein banding patterns between the two nematocysts, suggesting potential functional specialization. Previous studies have shown that the composition of jellyfish venom in nematocysts is complex, including both proteinaceous (up to 220 kDa) and non-proteinaceous components [

41]. Notably, multiple enzymatic constituents have been identified in jellyfish venoms, with phospholipases, metalloproteinases, and serine proteases representing the most prominent components [

4].

PLA

2, a ubiquitous component of animal venoms, exerts hemolytic effects through hydrolysis of membrane phospholipids into lysophospholipids, thereby disrupting erythrocyte membrane integrity and directly causing hemolysis [

42,

43]. While both AnC and OnC demonstrated comparable PLA

2 activity that significantly exceeded TeC, only OnC exhibited marked hemolytic activity. The reason may be that the phospholipases in AnC have substrate selectivity. It may also be that, due to the structural constraints of AnC phospholipases, optimal membrane interaction in murine systems was prevented [

44,

45].

Metalloproteinases represent a typical toxin family in the venoms of jellyfish and various other venomous organisms. They can induce hemorrhage and necrosis through modulation of coagulation factors, platelet function, fibrinolytic activity, and vascular integrity [

46,

47,

48]. Our results revealed significantly stronger metalloproteinase activity in OnC than in AnC. Gelatin zymographic analysis demonstrated that while both AnC and OnC possessed gelatinolytic activity, distinct banding patterns were observed in AnC and OnC. The gelatinases mainly including MMP-2 (gelatinase A, 72 kDa) and MMP-9 (gelatinase B, 92 kDa), which are both key matrix metalloproteinase family members, and the band variability in the gel potentially attributes to their proenzyme/activated forms and post-translational modifications (e.g., glycosylation). Notably, the observed lytic bands at ~110 kDa for AnC and ~100 kDa for both OnC and TeC may reflect either glycosylated MMP-9 variants or the presence of additional MMP isoforms contributing to the collective gelatin degradation activity [

32,

49].

Serine proteases, characterized by their catalytically active serine residues, represent a toxin family capable of inducing coagulopathy, hemorrhage, and hemodynamic shock through interfering with the coagulation and fibrinogenolytic system [

50,

51,

52]. Notably, fibrinogenolytic serine proteases, particularly those with plasmin-like activity, mediate fibrinogen degradation through multisite cleavage, generating soluble fibrin degradation products. This fibrinolytic activity exhibits functional synergy with metalloproteinases in venom systems [

53]. Both AnC and OnC exhibit fibrinogenolytic activity mediated by serine protease, with the enzymatic activity of OnC being significantly higher than that of AnC, and these proteolytic effects can be effectively inhibited by the addition of 1,10-phenanthroline.

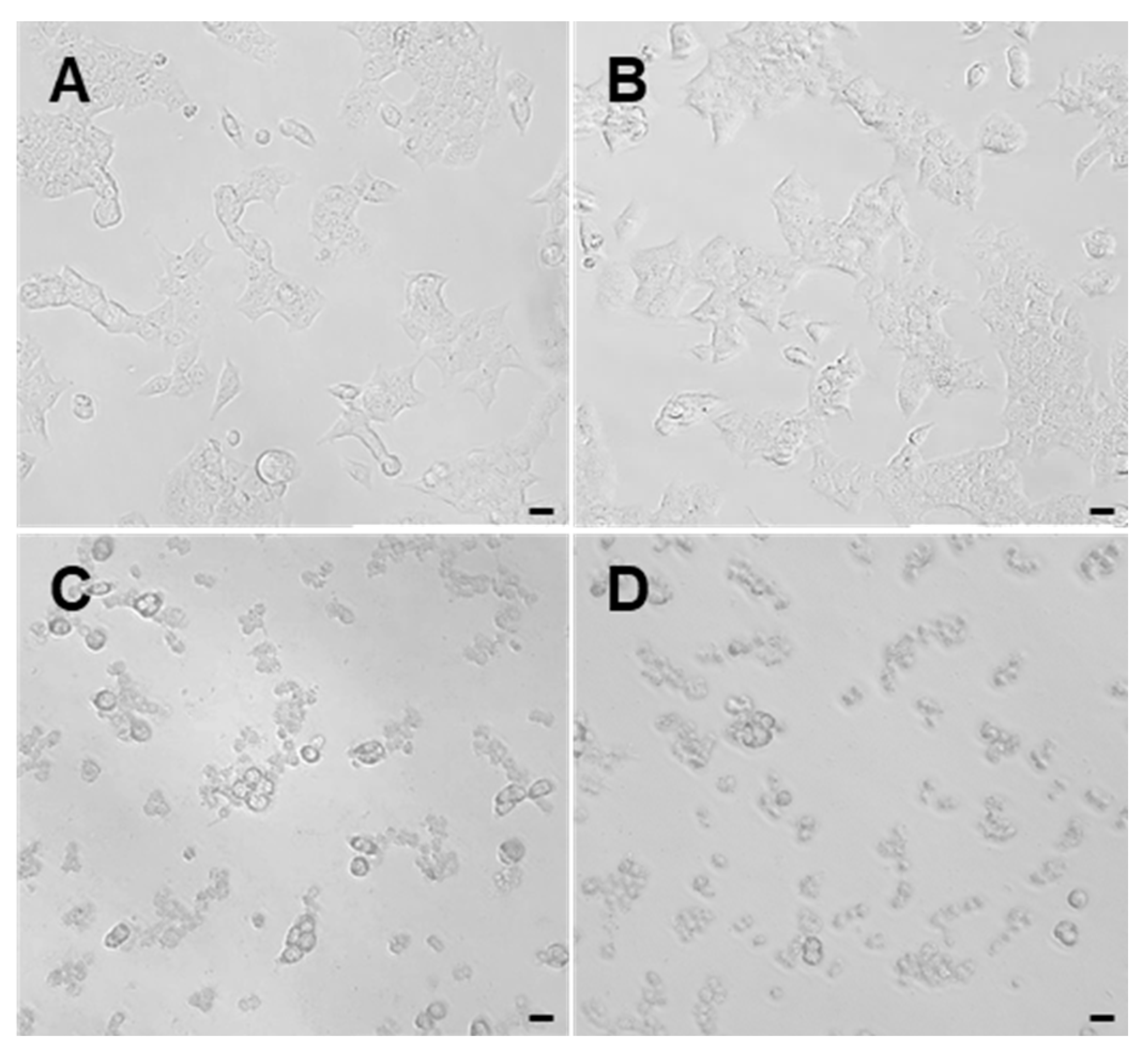

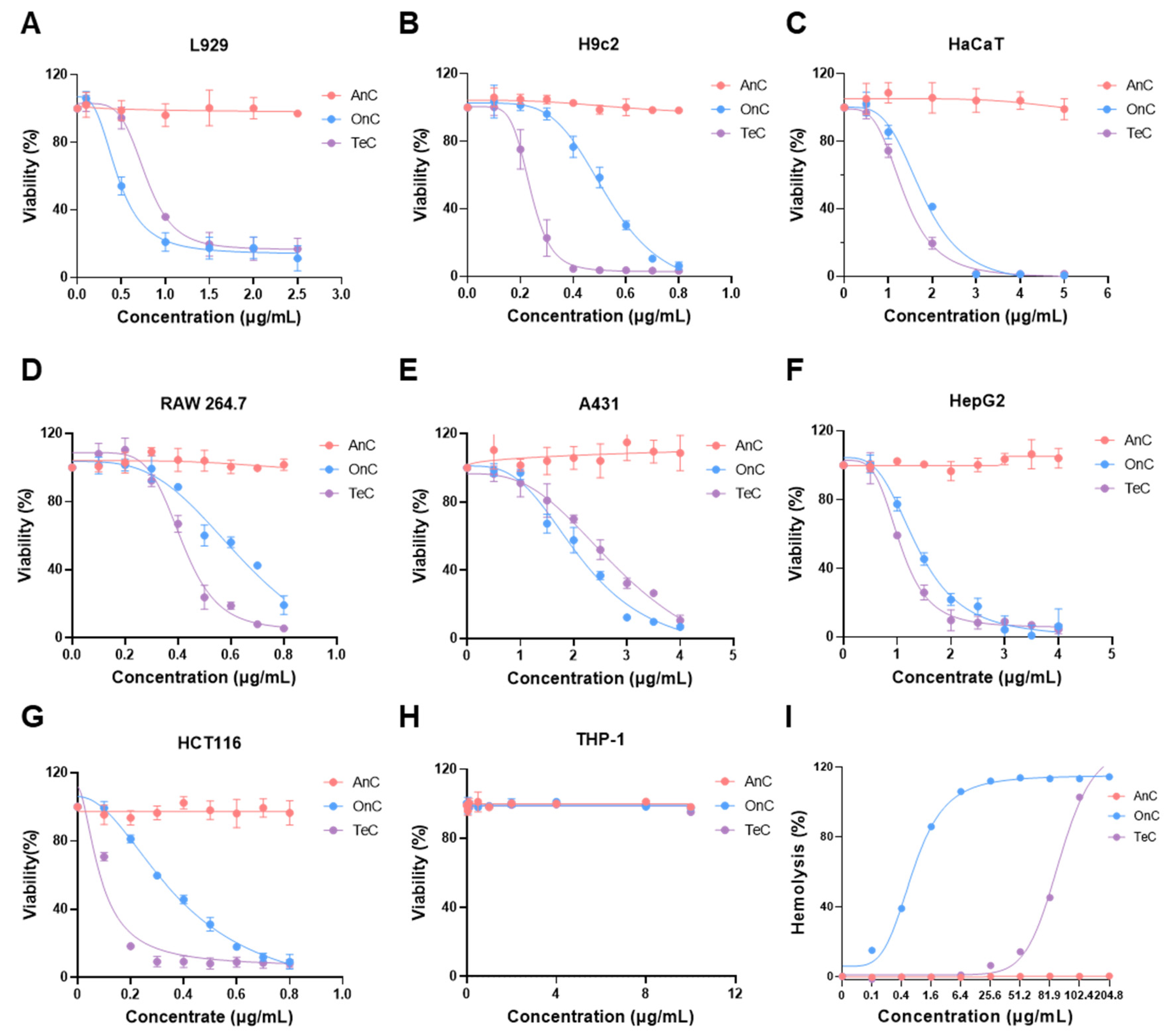

Cnidarian venoms have been reported to exert cytotoxic effects across diverse cell lineages. For example, the venom of Rhopilema nomadica showed dose-dependent cytotoxicity to human hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2), human breast adenocarcinoma (MDA-MB-231), human normal fibroblast (HFB4), and human normal lung fibroblast (WI-38) cell lines [

54], along with the cytotoxic activity of Pelagia noctiluca, Phyllorhiza punctata, and Cassiopea andromeda venoms toward L929 cells [

55]. In this study, AnC failed to demonstrate significant cytotoxicity against all three tested normal cell lines and five tumor cell lines, whereas OnC exhibited concentration-dependent cytotoxicity in all evaluated cell lines except THP-1. These findings are consistent with the results of the demonstrated enzymatic activity profiles mentioned above, suggesting that OnC possesses substantially stronger toxic potential compared to AnC.

Morphological and biochemical analysis both demonstrated distinct functional specialization between these two nematocyst types. O-isorhizas, with their spiral-structured nematocyst threads, exhibited superior penetration and discharge capacity. Furthermore, OnC demonstrated significantly higher metalloprotease, serine protease, and hemolytic activities, suggesting its potential dominant role in the processes such as prey capture and defense, tissue degradation, coagulation disruption, and hemorrhage induction. In contrast, Anisorhizas is relatively small in size, with significantly weaker discharge capacity as well as metalloproteinase and serine protease activities, and the toxic effects and tissue damage induced by Anisorhizas may be milder. However, it may have preferentially enhanced other functions such as cooperative predation and balancing energy consumption. The synergistic effect among different types of nematocysts may be an optimized predatory strategy, balancing immediate attack (O-isorhizas) with sustained metabolic efficiency (Anisorhizas).

In addition to their toxic effects, jellyfish venoms exhibit multiple biological activities, including antioxidant activity, antiarrhythmic activity and antimicrobial properties. Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) such as aurelin, CgDef, and tregencin A/B have been identified in various jellyfish species including Aurelia aurita, Chrysaora quinquecirrha, Carybdea marsupialis, and Rhopilema esculentum [

34,

35,

36,

37,

56]. Notably, for the 10 tested pathogenic bacteria, AnC and OnC exhibited significant inhibition against Vibrios mimicus, a clinically relevant pathogen causing gastroenteritis and cholera-like diarrhea characterized by abdominal pain, diarrhea and vomiting [

57]. These results indicate that the antimicrobial effects of AnC and OnC are likely related to the unique cell wall structure or the metabolic pathways of pathogenic bacteria. Further studies on their antimicrobial spectrums and molecular mechanisms of the antimicrobial effects may provide new leads for marine drug discovery.

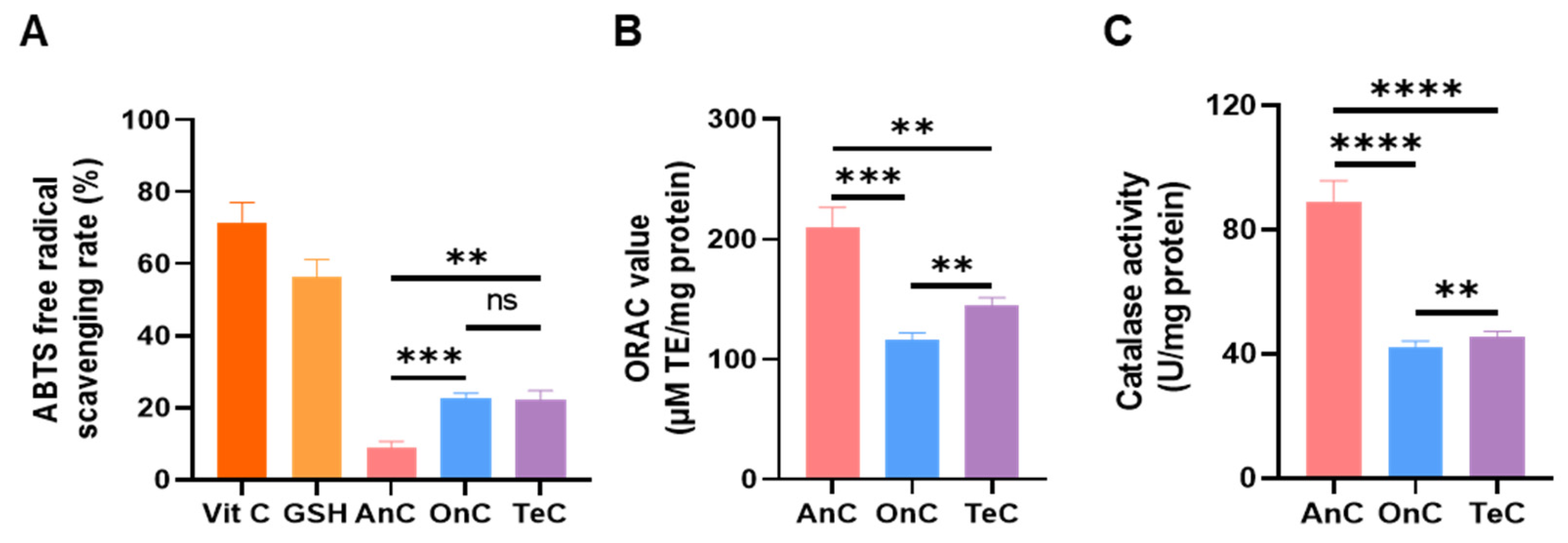

Previous studies by Kazuki et al. [

58] reported a relatively low antioxidant activity in

N. nomurai umbrella tissue (0.00541 μM trolox equivalent (TE)/mg by ORAC assay), whereas our investigation demonstrated significantly higher antioxidant activity for nematocyst extracts (AnC: 209.7±16.99 μM TE/mg; OnC: 116.0±6.07 μM TE/mg by ORAC assay), suggesting that nematocysts may have evolved enhanced antioxidant systems to protect their venom integrity, maintain symbiotic relationships, and counteract environmental oxidative stress. Suganthi et al. [

59] isolated Frc-3 and Fre-3 from the venom of Chrysaora quinquecirrha, with Frc-3 demonstrating scavenging activity against hydroxyl radicals (·OH) and nitric oxide radicals (NO·). Fre-3 also exhibited potent antioxidant properties, effectively eliminating DPPH radicals, superoxide anions (O2·

⁻), and ·OH [

60]. This study revealed that AnC exhibits superior oxygen radical scavenging capacity and catalase activity compared to OnC. The potent antioxidant activity of Anisorhizas nematocysts likely represents a multifunctional adaptive mechanism that not only preserves venom efficacy and structural integrity but may also participate in modulating microenvironmental redox homeostasis and environmental stress adaptation.

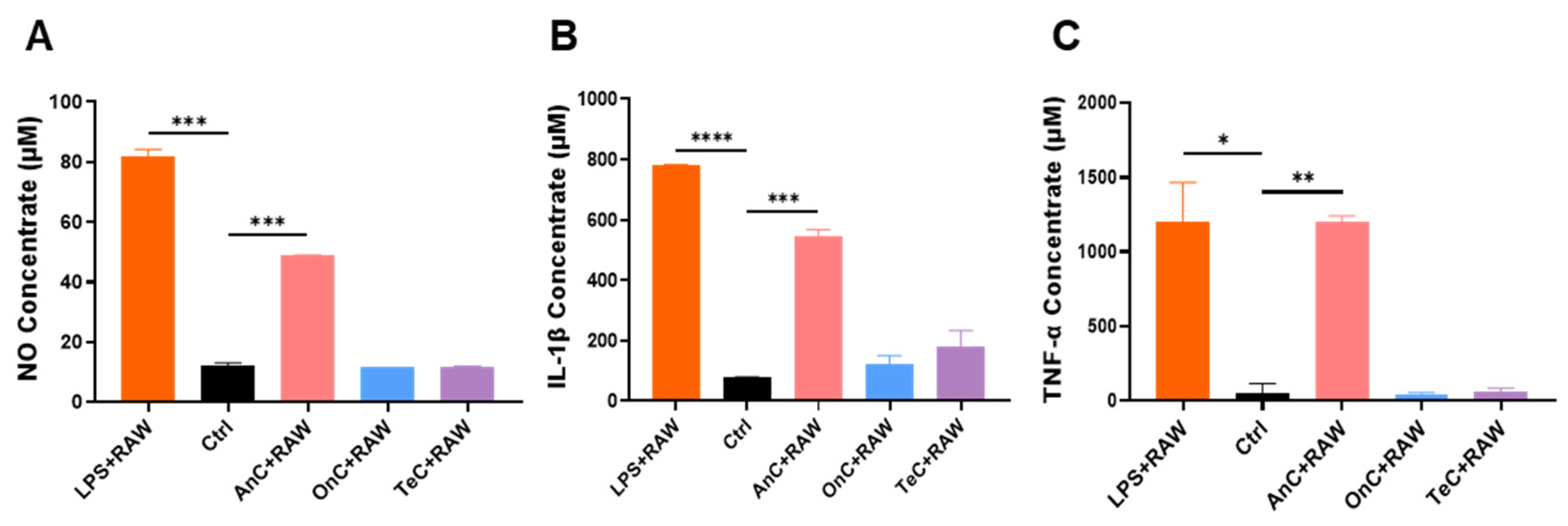

Jellyfish venom induces cutaneous inflammatory responses, with potential systemic toxicity when entering circulation, though the molecular mechanisms underlying these effects remain poorly characterized [

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68]. This study provides the first comparative analysis of inflammatory responses induced by isolated monomorphic nematocysts. The results revealed that AnC exhibited significantly greater proinflammatory activity than OnC, as evidenced by its capacity to markedly elevate key inflammatory mediators. These findings suggest that AnC may contain special inflammatory components capable of specific immune receptor recognition and subsequent activation of proinflammatory signaling pathways. It potentially plays a role in the inflammatory rection of jellyfish stings. However, OnC may lack such proinflammatory components with high-affinity, or may not be able to effectively trigger such reactions due to structural differences. The specific proinflammatory molecules in AnC and their mechanisms need to be further analyzed in depth through component research.

4. Materials and Methods

5.1. Chemicals and Reagents

Percoll was purchased from GE Healthcare (Chicago, Illinois, United States). A Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK8) was purchased from Dojindo Molecular Technologies Inc. (Kumamoto, Japan). Azocasein, 4-nitro-3-octanoyloxybenzoic acid (NOBA) and lipopolysaccharide were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Catalase assay kit and NO assay kit were purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Mouse IL-1β ELISA kit and mouse TNF-α ELISA kit were purchased from UPPBIO Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). All the other reagents used were of analytical grade.

5.2. Jellyfish Collection

Specimens of the jellyfish N. nomurai were collected from Laoshan Bay in Qingdao, China, in August 2023. The jellyfish tentacles were excised immediately. The isolated tentacles were placed in plastic bags with dry ice and immediately transported to the laboratory, where the samples were stored in a −80 ℃ freezer until use.

5.3. Isolation and Purification of Two Monomorphic Nematocysts

Figure 11 illustrates the isolation and purification protocol for monomorphic nematocysts from

N. nomurai. Tentacle tissues were homogenized with high-Mg²⁺ artificial seawater (1:1.5 w/v, 0.6 M Mg²⁺) and subjected to 3-day autolysis at 4°C in a chromatography cabinet to maintain nematocyst stability, with bi-daily agitation (15 min/session). The lysate was sequentially filtered through 200- and 400-mesh sieves, followed by 6-hour static sedimentation in the cabinet. The resulting biphasic solution was separated into upper (sample A) and lower (sample O) fractions for collection.

5.2.1. Isolation and Purification of Anisorhizas

The sample A suspension was centrifuged at 100×g for 3 min at 4°C. The resulting pellet was resuspended in high-Mg²⁺ artificial seawater (1:2 w/v) and stored at 4°C. A discontinuous Percoll gradient was prepared by sequentially layering 2 mL each of 90%, 70%, 50%, and 30% Percoll solutions (pre-chilled at 4°C) in 15 mL centrifuge tubes, either by careful pipetting along the tube wall or by low-speed centrifugation to establish distinct interphase boundaries. The resuspended sample (2 mL) was then carefully loaded onto the gradient and centrifuged at 150×g for 60 min at 4°C. The white suspension collected from the 50-70% interface was diluted with 10 volumes of high-Mg²⁺ artificial seawater and centrifuged at 1,000×g for 60 min at 4°C. This washing procedure was repeated 3-5 times to completely remove Percoll, yielding undischarged Anisorhizas nematocysts from N. nomurai.

5.2.2. Isolation and Purification of O-Isorhizas

The Sample O suspension was subjected to primary centrifugation (100×g, 3 min, 4°C), with the resulting pellet resuspended in high-Mg²⁺ artificial seawater (1:2 w/v) and stored at 4°C. A discontinuous Percoll density gradient was prepared in 15 mL centrifuge tubes by sequential layering of 90%, 50%, and 30% Percoll solutions. The resuspended sample (2 mL) was loaded onto the gradient and centrifuged (100×g, 20 min, 4°C). The bottom-layer pellet was collected and washed through 3-5 cycles of resuspension in 10-fold volume of high-Mg²⁺ artificial seawater followed by centrifugation (100×g, 10 min, 4°C), ultimately yielding undischarged O-isorhizas nematocysts from N. nomurai.

5.4. Assessment of Nematocyst Discharge Capacity

The purified Anisorhizas and O-isorhizas nematocyst pellets were resuspended in an appropriate volume of high-Mg²⁺ artificial seawater using gentle pipetting. A 10 μL aliquot of the nematocyst suspension was transferred to a microscope slide, and excess moisture was removed from around the coverslip edges with absorbent paper. After 1 min of air-drying to ensure surface adherence, a microscopic field was selected for observation. Using a microinjector, 2 μL of deionized water was introduced into the field, and nematocyst discharge events were immediately recorded under optical microscopy.

5.5. Nematocyst Content Extraction and SDS-PAGE Analysis

The contents from Anisorhizas and O-isorhizas were extracted using the method by Li et al. [

69], with a slight modification. Briefly, the two nematocysts were suspended in deionized water and then ultrasonicated using a Misonix Sonicator (S-4000-010, Qsonica LLC, The Meadows, FL, USA) at 400 W until more than 90% nematocysts were released or broken under a microscope. After centrifugation at 1,000×g for 15 min at 4℃, the supernatant was then dialyzed against phosphate buffer saline (PBS, 0.01 mol/L, pH 7.4) for 8 h before use. The contents of two nematocysts were named AnC and OnC, respectively, and the protein concentration of AnC and OnC was determined by BCA method. Then, AnC and OnC (10 μg total protein of AnC and 4 μg protein of OnC, respectively) were loaded onto 12% reducing sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gels. Electrophoresis was performed according to the methods described by Wang et al. [

10] using a PowerPac Universal Power Supply system (Bio-Rad, CA, USA). Protein bands were visualized with Coomassie brilliant blue staining.

5.6. N. nomurai Tentacle Extraction

Tentacle extracted content (TeC) was extracted from

N. nomurai tentacles (contain all types of nematocysts) according to the method described by Li et al. [

69], with a slight modification. Briefly, the frozen tentacles were thawed at 4 ℃ in artificial seawater (NaCl 28 g, MgCl

2·6H

2O 5 g, KCl 0.8 g, and CaCl

2 1.033 g, added distilled water to 1000 mL) at a quality and volume ratio of 1:1 for autolysis. After 4 d, the mixtures were filtered through a 400-mesh sieve to remove large tissue debris. The filtrate was then centrifuged at 500× g for 3 min at 4 ℃, and sediments were washed three times with artificial seawater. The 50% and 90% Percoll solutions prepared with artificial seawater were placed at 2 mL per concentration from high to low in a 15 mL centrifuge tube, and then, the washed sediments were loaded at 2 mL. The centrifuge tube was centrifuged horizontally at 1000× g for 15 min at 4 ℃, and then, the white sediments at the bottom were collected and washed three times with artificial seawater to obtain nematocysts containing venom. The sediments were used immediately for content extraction or, alternatively, frozen at -80 ℃ until use.

5.7. Cytotoxicity Assays

Cells were cultured in incubator at 37°C with 5% CO₂ until reaching 80% confluence. Cell digestion was performed using 0.25% trypsin (with gentle pipetting for semi-adherent RAW 264.7 cells, while suspension THP-1 cells required no enzymatic treatment). Cell suspensions were seeded in 96-well plates at densities of 5,000-12,000 cells/well (100 µL/well), followed by 24-hour incubation. After medium removal, cells were treated with 100 µL of serially diluted AnC, OnC, and TeC in basal medium, with PBS and basal medium serving as negative and blank controls, respectively. Following 4-hour treatment, 10% (v/v) CCK-8 reagent was added to each well for 1-3 hours. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader, with triplicate wells per condition. Cell viability was calculated as: [(OD₄₅₀ treatment - OD₄₅₀ blank)/(OD₄₅₀ control - OD₄₅₀ blank)] × 100%.

5.8. Enzyme Activity Assays

5.8.1. Metalloproteinase Activity

Metalloproteinase activity was measured using a previously described azocasein-based assay [

10]. Briefly, 50 mg of azocasein was accurately weighed and dissolved in 10 mL of buffer solution (50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, containing 100 mmol/L NaCl and 5 mmol/L CaCl₂) with gentle stirring to prepare a clear 5 mg/mL azocasein reaction solution. Then, 15 μL of AnC (stock solution, 1.32 mg/mL), OnC (stock solution, 2.88 mg/mL) and TeC (stock solution, 2.53 mg/mL) was mixed with 85 μL of the reaction solution respectively, while Tris-HCl buffer served as the negative control. After thorough mixing, the samples were incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The reaction was terminated by adding 200 μL of 5% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid (TCA), followed by incubation at room temperature for 30 min. The mixture was then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C, and 150 μL of the supernatant was transferred to a 96-well plate. An equal volume of 0.5 M NaOH was added to each well to neutralize residual TCA. The absorbance was determined at 450 nm using a microplate reader. One unit of proteolytic activity was defined as an increase of 0.01 unit of absorbance at 450 nm, and the specific activity was expressed in units per milligram of protein (U/mg).

5.8.2. Zymography of Proteases

The protease activity of AnC and OnC were examined according to the method by Li et al. [

69], with minor modifications. Gelatin was purchased from Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Briefly, Gelatin (2 mg/mL) was dissolved in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and copolymerized with 10% polyacrylamide to prepare zymography gels. AnC (stock solution, 1.32 mg/mL), OnC (stock solution, 2.88 mg/mL) and TeC (stock solution, 2.53 mg/mL) were prepared in nonreducing sample buffer and then run on gels at 150V/gel for 1 h at 4℃. After electrophoresis, the gels were washed for 30 min twice with renaturing buffer and incubated for an additional 18 h at 37 ℃ for enzymatic reaction in zymography reaction buffer. The gel was then stained with Coomassie staining solution. Clear zones in the gel indicate regions of proteolytic activity.

5.8.3. PLA2 Activity

PLA

2 activity was measured using a previously described assay [

10]. Briefly, 25 μL of AnC (stock solution, 1.32 mg/mL), OnC (stock solution, 2.88 mg/mL) and TeC (stock solution, 2.53 mg/mL) was added to a 96-well plate, followed by 250 μL of reaction buffer (10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, containing 10 mmol/L CaCl₂ and 100 mmol/L NaCl), with Tris-HCl buffer serving as the negative control. Subsequently, 25 μL of NOBA was added, and the mixture was thoroughly mixed and incubated at 37°C for 20 min. The reaction was terminated by adding 200 μL of Triton X-100 in an ice bath. Absorbance at 425 nm was measured using a microplate reader, with each sample analyzed in triplicate. An increase of 0.1 absorbance units (AU) at 425 nm corresponds to the release of 25.8 nmol of the chromophore 3-hydro-4-nitrobenzoic acid. PLA

2 specific activity was expressed as nmol/min/mg.

5.8.4. Fibrinogenolytic Assay

Fibrinogenolytic activity was measured according to the method by Bae et al. [

53], with minor modifications, AnC, OnC, and TeC (100 μg/mL) were mixed with fibrinogen at a 10:1 ratio (sample:substrate) respectively. For inhibitor groups, samples were pre-incubated with 1,10-phenanthroline (10:1:10 ratio of sample: substrate: inhibitor), while fibrinogen alone served as the negative control. All reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 16 h. Following incubation, samples were mixed with loading buffer, boiled at 100°C for 5 min, and analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The extent of fibrinogen degradation or residual substrate levels indirectly reflects serine protease activity.

5.9. Hemolysis Assays

Hemolytic activity was evaluated using erythrocytes from male ICR mice (30±1 g body weight). Whole blood was collected via retro-orbital bleeding and mixed with PBS, followed by centrifugation at 1,000× g for 10 min at 4°C. After removing the serum and leukocyte layers, the washing procedure was repeated 2-3 times. Subsequently, 200 μL of the erythrocyte suspension was gently mixed with 9.8 mL PBS to prepare a 2% erythrocyte suspension, which was stored at 4°C for subsequent experiments. For the assay, 100 μL of the erythrocyte suspension was mixed with an equal volume of AnC, OnC, or TeC at various concentrations (0.1, 0.4, 1.6, 6.4, 25.6, 51.2, 81.92, 102.4, and 204.8 μg/mL). PBS and Triton X-100 served as the negative and positive controls, respectively. The mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 1,500× g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant (100 μL) was transferred to a 96-well plate (triplicate wells per sample), and absorbance at 540 nm was measured using a microplate reader. Hemolytic activity was expressed as % absorbance.

5.10. Antimicrobial Activity

All procedures were performed under sterile conditions in a biosafety cabinet. The frozen bacterial strains were first revived and then inoculated into appropriate liquid medium, followed by incubation in a constant temperature incubator for 12-36 h until reaching the logarithmic growth phase (OD600≈0.6-1). For the assay, 20 μL of the logarithmic-phase bacterial suspension was mixed with 20 μL of the tested samples (AnC 1.32 mg/mL, OnC 2.88 mg/mL, and TeC 2.53 mg/mL) in 100 μL of liquid medium, while a control group was prepared by mixing bacterial suspension with an equal volume of PBS buffer. The inoculated culture systems were then continuously cultured under appropriate conditions in a shaking incubator. The optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was measured at 0 h, 4 h, 8 h, 12 h, and 16 h time points to monitor bacterial growth. All data were processed using GraphPad Prism 9.0 software. Differences in growth kinetics among groups were analyzed and compared through nonlinear regression analysis.

5.11. Antioxidant Activity Assay

5.11.1. ABTS·+ Scavenging Assay

Total Antioxidant Capacity (T-AOC) Assay Kit (ABTS Method, Microplate) (#D799298-0100) was purchased from Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The ABTS radical cation (ABTS·+) scavenging assay was performed strictly according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The working solution was prepared by adding 7 mL of Reagent 1 to one vial of Reagent 2, followed by vigorous vortex mixing for 20 min and subsequent equilibration at room temperature. For the assay, the blank control consisted of 10 μL extraction buffer mixed with 190 μL working solution, while the sample groups contained 10 μL sample (1 mg/mL) mixed with 190 μL working solution. After thorough mixing and 20 min incubation at room temperature, the absorbance at 734 nm was measured with triplicate determinations for each group. The ABTS·+ scavenging activity was expressed as % absorbance.

5.11.2. Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity

The oxygen radical absorbance capacity of AnC and OnC quantified by ORAC method was performed as previously described, with slight modification [

70]. In brief, 25 μL each of sample (AnC 1.32 mg/mL, OnC 2.88 mg/mL, and TeC 2.53 mg/mL), various concentrations of trolox standard solution (for construction of a standard curve) or blank buffer (as a control) were placed in the individual wells of a 96-well transparent microplate. Fluorescein working solution (150 μL) was added and the wells were agitated at 37℃ for 30 min. Subsequently, 25 μL of AAPH solution was added to each of the wells to initiate the reaction. The total volume of each reaction solution was 200 μL. The fluorescence intensity [480 nm (extraction)/520 nm (emission)] was then measured every 5 min over 60 min at 37℃. As the reaction progressed, fluorescenin was consumed and the fluorescence intensity decreased. The inhibition of fluorescence decay was taken to indicate the presence of an antioxidant. The area under the kinetic curve (AUC) of the standards and samples was calculated as follows:

The ORAC value, expressed as μM Trolox equivalents per milligram of protein (μM TE/mg protein), was obtained by normalizing the measured antioxidant activity to the protein content of each sample, representing its peroxyl radical scavenging capacity [

59].

5.11.3. Catalase Activity Assay

The catalase (CAT) activity was measured using a commercial Catalase Assay Kit (#S0051, Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 3 μL of AnC, OnC, or TeC (1 mg/mL) was added to 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes respectively, followed by the addition of assay buffer to a final volume of 40 μL, while the blank control contained only 40 μL assay buffer. After thorough mixing, 10 μL of 250 mM hydrogen peroxide solution was added and immediately mixed by pipetting. The reaction proceeded at 25°C for 3 min before termination with 450 μL stop solution. Subsequently, 40 μL assay buffer was aliquoted into new 1.5 mL tubes, followed by addition of 10 μL of the terminated reaction mixture. After mixing, 10 μL of this solution was transferred to a 96-well microplate and mixed with 200 μL chromogenic working solution. Following 15 min incubation at 25°C, the absorbance at 520 nm was measured with triplicate determinations for each sample. Catalase activity was calculated as: Catalase activity = (μmol hydrogen peroxide consumed × dilution factor)/(reaction time in minutes × sample volume × protein concentration), expressed in standard enzyme activity units.

5.12. Proinflammatory Effect Assays

The proinflammatory effects of AnC and OnC were quantified according to a previously reported method [

63], with slight modifications. RAW 264.7 (1 × 10

4 cells/well) were seeded in a 48-well culture plate and cultured for 24 h, treated with AnC, OnC and TeC (0.1 μg/mL) or LPS (1 μg/mL) and incubated for 24 h. NO concentrations in medium were determined using a Griess assay; Griess reagent (50 μL) was added to media supernatants (50 μL) and then incubated at 37 °C for 20 min in the dark. Absorbance was measured at 520 nm. NO concentrations were determined using 0−100 μM sodium nitrite standards. TNF-α and IL-1β expression levels in culture media were quantified using sandwich-type ELISA kits.

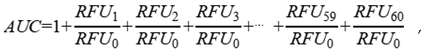

Figure 1.

Light microscopic observation of nematocysts in N. nomurai tentacles. (A) Microscopic image of jellyfish tentacle (magnification 10×). (B) Three types of nematocysts observed in the tentacles (magnification 40×). (C) O-isorhizas. (D) Euryteles. (E) Anisorhizas. Bar scale, 20 μm.

Figure 1.

Light microscopic observation of nematocysts in N. nomurai tentacles. (A) Microscopic image of jellyfish tentacle (magnification 10×). (B) Three types of nematocysts observed in the tentacles (magnification 40×). (C) O-isorhizas. (D) Euryteles. (E) Anisorhizas. Bar scale, 20 μm.

Figure 2.

Microscopic morphology of Anisorhizas and O-isorhizas. (A) Anisorhizas observed under light microscope (40× magnification). (B) O-isorhizas observed under light microscope (40× magnification). (C) O-isorhizas(undischarged) and Anisorhizas(discharged) observed under SEM, respectively. (D) Anisorhizas(undischarged) observed under SEM. (E) Ruptured O-isorhizas observed under SEM.

Figure 2.

Microscopic morphology of Anisorhizas and O-isorhizas. (A) Anisorhizas observed under light microscope (40× magnification). (B) O-isorhizas observed under light microscope (40× magnification). (C) O-isorhizas(undischarged) and Anisorhizas(discharged) observed under SEM, respectively. (D) Anisorhizas(undischarged) observed under SEM. (E) Ruptured O-isorhizas observed under SEM.

Figure 3.

Discharge abilities of Anisorhizas and O-isorhizas. (A) Discharged Anisorhizas and (B) discharged O-isorhizas were observed during isolation. (C) Undischarged Anisorhizas and (E) undischarged O-isorhizas were observed before stimulation with deionized water. (D) Discharged Anisorhizas and (F) discharged O-isorhizas were observed after treatment with deionized water. Bar scale, 20 μm.

Figure 3.

Discharge abilities of Anisorhizas and O-isorhizas. (A) Discharged Anisorhizas and (B) discharged O-isorhizas were observed during isolation. (C) Undischarged Anisorhizas and (E) undischarged O-isorhizas were observed before stimulation with deionized water. (D) Discharged Anisorhizas and (F) discharged O-isorhizas were observed after treatment with deionized water. Bar scale, 20 μm.

Figure 4.

SDS-PAGE ananlysis of AnC and OnC. AnC (10 μg of total protein) and OnC (4 μg of total protein) were separated in a 12% polyacrylamide gel and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. M indicates the protein molecular marker (Beyotime), and the molecular masses of the protein standards are shown in kilodaltons (kDa).

Figure 4.

SDS-PAGE ananlysis of AnC and OnC. AnC (10 μg of total protein) and OnC (4 μg of total protein) were separated in a 12% polyacrylamide gel and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. M indicates the protein molecular marker (Beyotime), and the molecular masses of the protein standards are shown in kilodaltons (kDa).

Figure 5.

Morphological characterization of HCT116 cells after treatment with AnC, OnC and TeC. HCT116 cell suspension was seeded in a 96-well plate and incubated in an incubator for 24 h. The medium was discarded, 100 μL of (A) PBS and 0.5 μg/mL of (B) AnC, (C) OnC, and (D) TeC were added respectively, and the incubation continued for 4 h. The morphology of the cells was observed under a microscope. Bar scale, 20 μm.

Figure 5.

Morphological characterization of HCT116 cells after treatment with AnC, OnC and TeC. HCT116 cell suspension was seeded in a 96-well plate and incubated in an incubator for 24 h. The medium was discarded, 100 μL of (A) PBS and 0.5 μg/mL of (B) AnC, (C) OnC, and (D) TeC were added respectively, and the incubation continued for 4 h. The morphology of the cells was observed under a microscope. Bar scale, 20 μm.

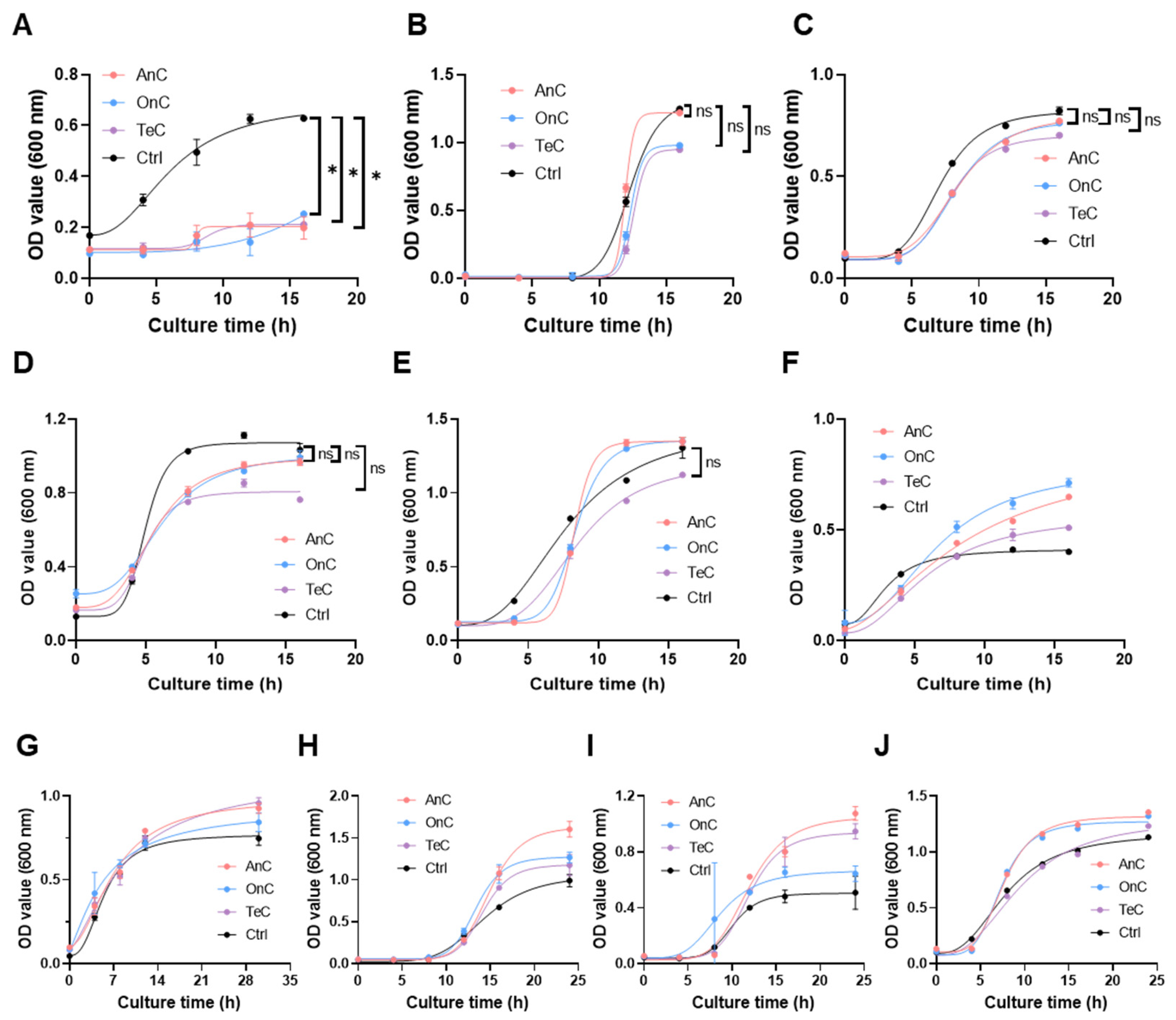

Figure 6.

Cytotoxicity and hemolytic activity of AnC, OnC and TeC. The Cell Counting Kit-8 assay was used to detect the cytotoxicity of AnC, OnC and TeC to different cell lines, including 3 normal cell lines such as (A) L929, (B) H9c2 and (C) HaCaT, and 5 tumor cell lines such as (D) RAW 264.7, (E) A431, (F) HepG2, (G) HCT116 and (H) THP-1. (I) Mouse erythrocytes were used to measure hemolytic effect of AnC, OnC and TeC. The results are expressed as the means ± SD of three independent experiments.

Figure 6.

Cytotoxicity and hemolytic activity of AnC, OnC and TeC. The Cell Counting Kit-8 assay was used to detect the cytotoxicity of AnC, OnC and TeC to different cell lines, including 3 normal cell lines such as (A) L929, (B) H9c2 and (C) HaCaT, and 5 tumor cell lines such as (D) RAW 264.7, (E) A431, (F) HepG2, (G) HCT116 and (H) THP-1. (I) Mouse erythrocytes were used to measure hemolytic effect of AnC, OnC and TeC. The results are expressed as the means ± SD of three independent experiments.

Figure 7.

Enzyme activity of AnC, OnC and TeC. (A) Azocasein degradation assay (U/mg, mean ± SD, n = 3). One unit of activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to cause an increase in OD by 0.01 at 450 nm. (B) PLA2 activity of AnC, OnC and TeC (U/mg, mean ± SD, n = 3). A change in absorbance of 0.10 AU at 425 nm was equivalent to the release of 25.8 nanomoles of chromophore (3-hydroxy-4-nitrobenzoic acid). (C) Gelatin enzyme assay. (D) Serine proteases activity of AnC, OnC and TeC (U/mg, mean ± SD, n = 3). (ns: p>0.05, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001).

Figure 7.

Enzyme activity of AnC, OnC and TeC. (A) Azocasein degradation assay (U/mg, mean ± SD, n = 3). One unit of activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to cause an increase in OD by 0.01 at 450 nm. (B) PLA2 activity of AnC, OnC and TeC (U/mg, mean ± SD, n = 3). A change in absorbance of 0.10 AU at 425 nm was equivalent to the release of 25.8 nanomoles of chromophore (3-hydroxy-4-nitrobenzoic acid). (C) Gelatin enzyme assay. (D) Serine proteases activity of AnC, OnC and TeC (U/mg, mean ± SD, n = 3). (ns: p>0.05, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001).

Figure 8.

Inhibitory effects of AnC, OnC and TeC on the growth of common terrestrial pathogenic bacteria and pathogenic vibrios. (A) Vibrio mimicus. (B) Pseudomonas aeruginosa. (C) Vibrio vulnificus. (D) Vibrio natriegens. (E) Vibrio parahaemolyticus. (F) Vibrio anguillarum. (G) Escherichia coli. (H) Staphylococcus aureus. (I) Bacillus subtilis. (J) Vibrio alginolyticu. The asterisks indicate a significance difference from the control value, with ns p>0.05, *p<0.05.

Figure 8.

Inhibitory effects of AnC, OnC and TeC on the growth of common terrestrial pathogenic bacteria and pathogenic vibrios. (A) Vibrio mimicus. (B) Pseudomonas aeruginosa. (C) Vibrio vulnificus. (D) Vibrio natriegens. (E) Vibrio parahaemolyticus. (F) Vibrio anguillarum. (G) Escherichia coli. (H) Staphylococcus aureus. (I) Bacillus subtilis. (J) Vibrio alginolyticu. The asterisks indicate a significance difference from the control value, with ns p>0.05, *p<0.05.

Figure 9.

Antioxidant capacity of AnC, OnC and TeC. (A) ABTS·+ scavenging capacity (T-AOC ABTS assay). (B) Oxygen radical scavenging capacity activity (ORAC). (C) Catalase activity. ns p>0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

Figure 9.

Antioxidant capacity of AnC, OnC and TeC. (A) ABTS·+ scavenging capacity (T-AOC ABTS assay). (B) Oxygen radical scavenging capacity activity (ORAC). (C) Catalase activity. ns p>0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

Figure 10.

Proinflammatory effect of AnC, OnC and TeC. (A) The levels of NO, (B) The levels of IL-1β, (C) The levels of TNF-α. The asterisks indicate a significance difference from the control value, with *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

Figure 10.

Proinflammatory effect of AnC, OnC and TeC. (A) The levels of NO, (B) The levels of IL-1β, (C) The levels of TNF-α. The asterisks indicate a significance difference from the control value, with *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

Figure 11.

Flow chart of isolation and purification of two nematocysts from N. nomurai tentacles.

Figure 11.

Flow chart of isolation and purification of two nematocysts from N. nomurai tentacles.