Submitted:

19 September 2025

Posted:

22 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

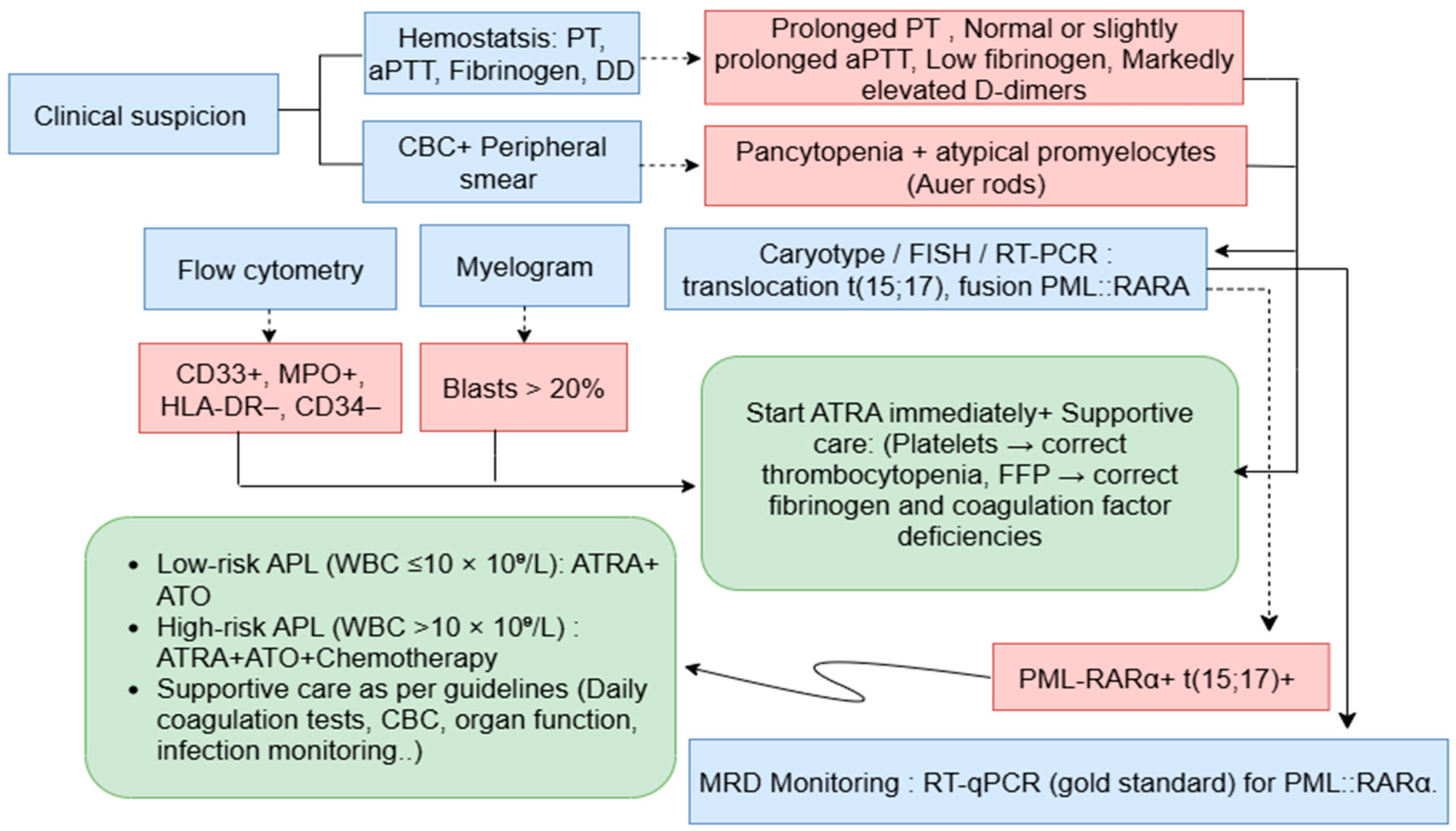

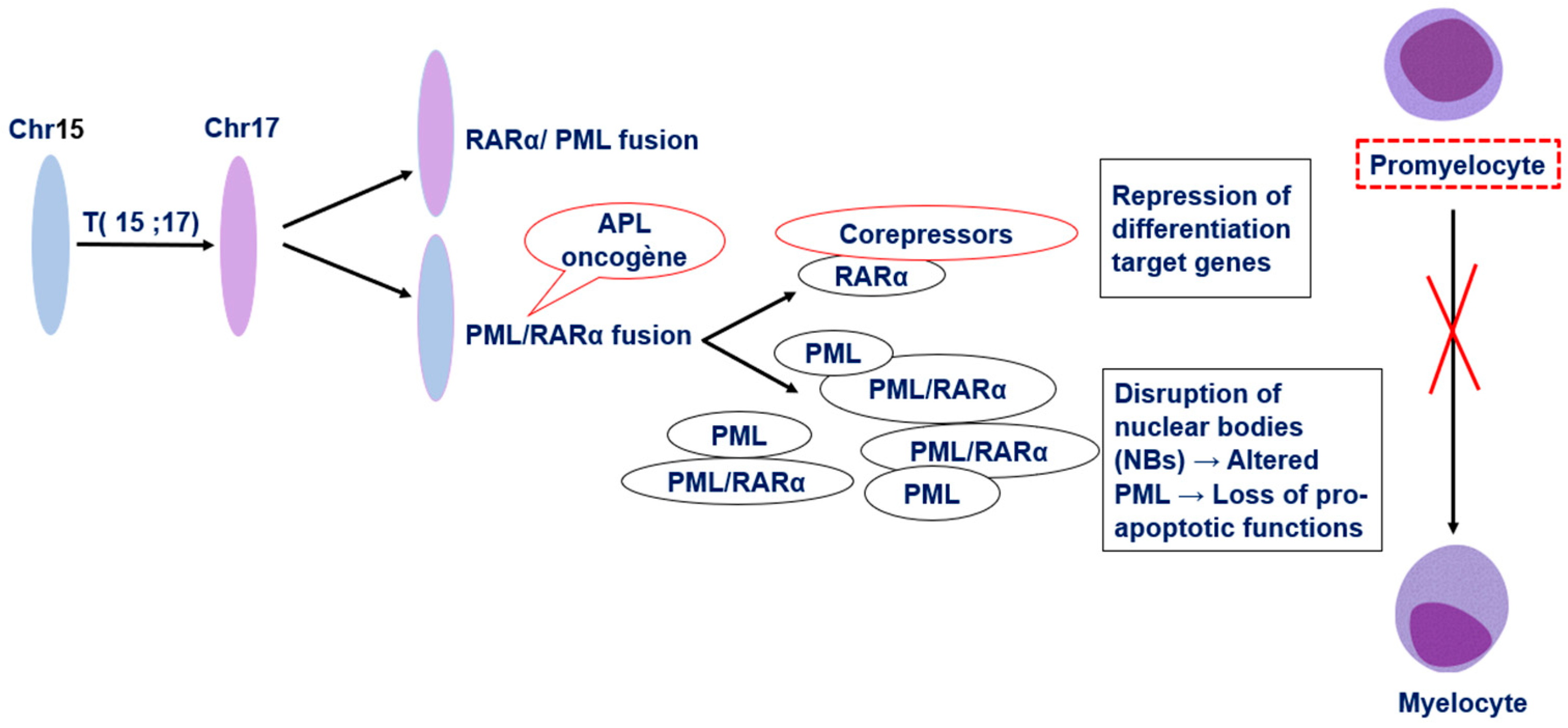

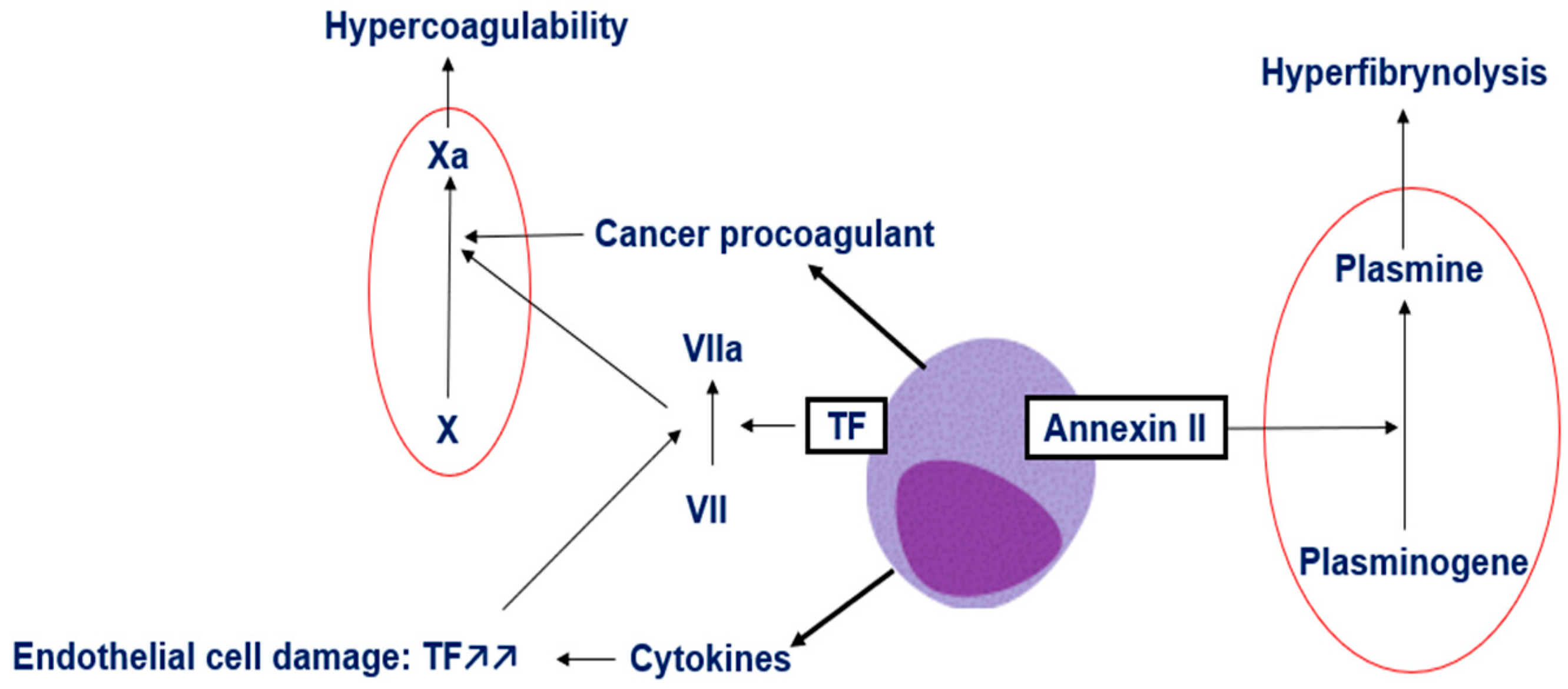

Background/Objectives: Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) is a distinct subtype of acute myeloid leukemia characterized by the t(15;17)(q24;q21) translocation, generating the PML-RARα fusion gene that blocks myeloid differentiation and drives leukemogenesis. Despite advances in therapy, early mortality remains a major challenge due to severe coagulopathy. This review aims to summarize recent insights into APL pathophysiology, diagnostic approaches, and management strategies. Methods: We performed a comprehensive review of the literature addressing the molecular mechanisms of APL, its associated coagulopathy, and current diagnostic and therapeutic standards, with a focus on evidence-based recommendations for clinical practice. Results: The hallmark PML-RARα oncoprotein disrupts nuclear body function and retinoic acid signaling, resulting in differentiation arrest and apoptosis resistance. APL-associated coagulopathy arises from overexpression of tissue factor, release of cancer procoagulant, inflammatory cytokines, and annexin II-mediated hyperfibrinolysis. Diagnosis requires integration of cytomorphology, immunophenotyping, coagulation studies, and molecular confirmation. Immediate initiation of all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA) upon clinical suspicion, combined with aggressive supportive care, is critical to control bleeding risk. Conclusions: APL is now a highly curable leukemia when recognized early and treated with targeted therapy. Rapid diagnosis, prompt ATRA administration, and meticulous hemostatic support are essential to reduce early mortality. Further refinements in minimal residual disease monitoring are expected to improve patient outcomes.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Pathophysiology of Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia

3. Mechanisms of Coagulopathy in APL

4. Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia Diagnosis

Clinical and Morphological Assessment

Immunophenotyping by Flow Cytometry

Coagulation Studies

Molecular and Cytogenetic Analyses

5. Clinical Management

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bidikian, A.; Bewersdorf, J.P.; Kewan, T.; Stahl, M.; Zeidan, A.M. Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia in the Real World: Understanding Outcome Differences and How We Can Improve Them. Cancers 2024, 16, 4092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana-Hernández, J.; Corona-Rivera, A.; Mendoza-Maldonado, L.; Santana-Bejarano, U.F.; Cuero-Quezada, I.; Marquez-Mora, A.; Serafín-Saucedo, G.; Brukman-Jiménez, S.A.; Corona-Rivera, R.; Ortuño-Sahagún, D.; et al. Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia with <em>PML/RARA</Em> (Bcr1, Bcr2 and Bcr3) Transcripts in a Pediatric Patient. Oncol. Lett. 2024, 27, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckardt, J.-N.; Schmittmann, T.; Riechert, S.; Kramer, M.; Sulaiman, A.S.; Sockel, K.; Kroschinsky, F.; Schetelig, J.; Wagenführ, L.; Schuler, U.; et al. Deep Learning Identifies Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia in Bone Marrow Smears. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Sun, J.; Yu, W.; Jin, J. Current Views on the Genetic Landscape and Management of Variant Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia. Biomark. Res. 2021, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, X.-D.; Mao, J.-H.; Wang, K.-K.; Caen, J.; Chen, S.-J. Hémorragie dans la leucémie aiguë promyélocytaire et au-delà: les rôles du facteur tissulaire et des mécanismes de régulation sous-jacents. Bull. Académie Natl. Médecine 2023, 207, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermsen, J.; Hambley, B. The Coagulopathy of Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia: An Updated Review of Pathophysiology, Risk Stratification, and Clinical Management. Cancers 2023, 15, 3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhry, A.; DeLoughery, T.G. Bleeding and Thrombosis in Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia. Am. J. Hematol. 2012, 87, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabljic, N.; Thachil, J.; Pantic, N.; Mitrovic, M. Hemorrhage in Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia—Fibrinolysis in Focus. Res. Pract. Thromb. Haemost. 2024, 8, 102499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odetola, O.; Tallman, M.S. How to Avoid Early Mortality in Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia. Hematology 2023, 2023, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kankhaw, S.; Owattanapanich, W.; Promsuwicha, O.; Thong-ou, T.; Ruchutrakool, T.; Khuhapinant, A.; Paisooksantivatana, K.; Kungwankiattichai, S. Immunophenotypic Profiling of Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia: Insights From a Large Cohort. Cancer Rep. 2025, 8, e70198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klausner, M.; Stinnett, V.; Ghabrial, J.; Morsberger, L.; DeMetrick, N.; Long, P.; Zhu, J.; Smith, K.; James, T.; Adams, E.; et al. Optical Genome Mapping Reveals Complex and Cryptic Rearrangement Involving PML::RARA Fusion in Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia. Genes 2024, 15, 1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, S.G.; Elias, L.; Stanchina, M.; Watts, J. The Treatment of Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia in 2023: Paradigm, Advances, and Future Directions. Front. Oncol. 2023, 12, 1062524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voisset, E.; Moravcsik, E.; Stratford, E.W.; Jaye, A.; Palgrave, C.J.; Hills, R.K.; Salomoni, P.; Kogan, S.C.; Solomon, E.; Grimwade, D. Pml Nuclear Body Disruption Cooperates in APL Pathogenesis and Impairs DNA Damage Repair Pathways in Mice. Blood 2018, 131, 636–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shima, Y.; Honma, Y.; Kitabayashi, I. PML-RARα and Its Phosphorylation Regulate PML Oligomerization and HIPK2 Stability. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 4278–4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhuo, Z.; Ma, X.; Yin, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Cong, Y.; Meng, G. Cryo-EM Structure of PML RBCC Dimer Reveals CC-Mediated Octopus-like Nuclear Body Assembly Mechanism. Cell Discov. 2024, 10, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, J.J.; Chale, R.S.; Abad, A.C.; Schally, A.V. Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia (APL): A Review of the Literature. Oncotarget 2020, 11, 992–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhry, R.; Killeen, R.B.; Babiker, H.M. Physiology, Coagulation Pathways. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Park, J.K. Back to Basics: The Coagulation Pathway. Blood Res. 2024, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liquori, A.; Ibañez, M.; Sargas, C.; Sanz, M.Á.; Barragán, E.; Cervera, J. Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia: A Constellation of Molecular Events around a Single PML-RARA Fusion Gene. Cancers 2020, 12, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Sun, J.; Yan, L.; Jin, B.; Hou, W.; Cao, F.; Li, H.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y. Tissue Factor–Bearing Microparticles Are a Link between Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia Cells and Coagulation Activation: A Human Subject Study. Ann. Hematol. 2021, 100, 1473–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambley, B.C.; Tomuleasa, C.; Ghiaur, G. Coagulopathy in Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia: Can We Go Beyond Supportive Care? Front. Med. 2021, 8, 722614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabljic, N.; Thachil, J.; Pantic, N.; Mitrovic, M. Hemorrhage in Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia—Fibrinolysis in Focus. Res. Pract. Thromb. Haemost. 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.; Nonas, S. A DIFFERENT KILLER: EARLY DEATH IN ACUTE PROMYELOCYTIC LEUKEMIA PRESENTING WITH SEPTIC SHOCK. CHEST 2020, 158, A903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, S.G.; Elias, L.; Stanchina, M.; Watts, J. The Treatment of Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia in 2023: Paradigm, Advances, and Future Directions. Front. Oncol. 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arber, D.A.; Orazi, A.; Hasserjian, R.P.; Borowitz, M.J.; Calvo, K.R.; Kvasnicka, H.-M.; Wang, S.A.; Bagg, A.; Barbui, T.; Branford, S.; et al. International Consensus Classification of Myeloid Neoplasms and Acute Leukemias: Integrating Morphologic, Clinical, and Genomic Data. Blood 2022, 140, 1200–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehgal, T.; Sharma, P. Auer Rods and Faggot Cells: A Review of the History, Significance and Mimics of Two Morphological Curiosities of Enduring Relevance. Eur. J. Haematol. 2023, 110, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladak, N.; Liu, Y.; Burke, A.; Lin, O.; Chan, A. Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia: A Rare Presentation without Systemic Disease. Hum. Pathol. Rep. 2024, 37, 300753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheli, E.; Chevalier, S.; Kosmider, O.; Eveillard, M.; Chapuis, N.; Plesa, A.; Heiblig, M.; Andre, L.; Pouget, J.; Mossuz, P.; et al. Diagnosis of Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia Based on Routine Biological Parameters Using Machine Learning. Haematologica 2022, 107, 1466–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Lan, H.; Yi, D.; Xian, B.; Zidan, L.; Li, J.; Liao, Z. Flow Cytometry in Acute Myeloid Leukemia and Detection of Minimal Residual Disease. Clin. Chim. Acta 2025, 564, 119945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Wang, S.A.; Hu, S.; Konoplev, S.N.; Mo, H.; Liu, W.; Zuo, Z.; Xu, J.; Jorgensen, J.L.; Yin, C.C.; et al. Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia: Immunophenotype and Differential Diagnosis by Flow Cytometry. Cytometry B Clin. Cytom. 2022, 102, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Noto, R.; Mirabelli, P.; Del Vecchio, L. Flow Cytometry Analysis of Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia: The Power of ‘Surface Hematology. ’ Leukemia 2007, 21, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röhnert, M.A.; Kramer, M.; Schadt, J.; Ensel, P.; Thiede, C.; Krause, S.W.; Bücklein, V.; Hoffmann, J.; Jaramillo, S.; Schlenk, R.F.; et al. Reproducible Measurable Residual Disease Detection by Multiparametric Flow Cytometry in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Leukemia 2022, 36, 2208–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahmarvand, N.; Oak, J.S.; Cascio, M.J.; Alcasid, M.; Goodman, E.; Medeiros, B.C.; Arber, D.A.; Zehnder, J.L.; Ohgami, R.S. A Study of Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation in Acute Leukemia Reveals Markedly Elevated D-Dimer Levels Are a Sensitive Indicator of Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia. Int. J. Lab. Hematol. 2017, 39, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Figueiredo-Pontes, L.L.; Catto, L.F.B.; Chauffaille, M.D.L.L.F.; Pagnano, K.B.B.; Madeira, M.I.A.; Nunes, E.C.; Hamerschlak, N.; De Andrade Silva, M.C.; Carneiro, T.X.; Bortolheiro, T.C.; et al. Diagnosis and Management of Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia: Brazilian Consensus Guidelines 2024 on Behalf of the Brazilian Association of Hematology, Hemotherapy and Cellular Therapy. Hematol. Transfus. Cell Ther. 2024, 46, 553–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Döhner, H.; Wei, A.H.; Appelbaum, F.R.; Craddock, C.; DiNardo, C.D.; Dombret, H.; Ebert, B.L.; Fenaux, P.; Godley, L.A.; Hasserjian, R.P.; et al. Diagnosis and Management of AML in Adults: 2022 Recommendations from an International Expert Panel on Behalf of the ELN. Blood 2022, 140, 1345–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, M.A.; Fenaux, P.; Tallman, M.S.; Estey, E.H.; Löwenberg, B.; Naoe, T.; Lengfelder, E.; Döhner, H.; Burnett, A.K.; Chen, S.-J.; et al. Management of Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia: Updated Recommendations from an Expert Panel of the European LeukemiaNet. Blood 2019, 133, 1630–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, M.A.; Fenaux, P.; Tallman, M.S.; Estey, E.H.; Löwenberg, B.; Naoe, T.; Lengfelder, E.; Döhner, H.; Burnett, A.K.; Chen, S.-J.; et al. Management of Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia: Updated Recommendations from an Expert Panel of the European LeukemiaNet. Blood 2019, 133, 1630–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantarjian, H.M.; DiNardo, C.D.; Kadia, T.M.; Daver, N.G.; Altman, J.K.; Stein, E.M.; Jabbour, E.; Schiffer, C.A.; Lang, A.; Ravandi, F. Acute Myeloid Leukemia Management and Research in 2025. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 46–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhu, H.; Dong, F.; Li, Y.; Liu, Q.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, J.; Hu, J.; Liu, T.; et al. Recommendations on Minimal Residual Disease Monitoring in Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia Treated with Combination of All- Trans Retinoic Acid and Arsenic Trioxide. Blood 2023, 142, 2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).