1. Introduction

Effective wildlife monitoring plays a critical role in modern conservation science. It provides essential data for conservation planning, biodiversity assessments, management of human-wildlife conflict, and the protection of endangered species. Accurate and timely monitoring enables researchers and policymakers to track population trends, identify threats, measure the effectiveness of conservation interventions, and make informed decisions. For example, population data are used to determine IUCN Red List status, prioritize conservation funding, and inform protected area designations (Nichols & Williams, 2006; O'Connell et al., 2011).

However, traditional methods of wildlife monitoring—such as direct observation, manual tracking, sign surveys, and mark-recapture—have significant limitations. These approaches are often labor-intensive, require extensive field time, are logistically challenging in remote or rugged terrains, and are prone to observer bias. Additionally, they offer limited spatial and temporal coverage and are not always scalable for large landscapes or elusive species (Burton et al., 2015). Infrequent sampling and limited funding further restrict the reliability of such methods, particularly in low-income regions where conservation resources are already constrained.

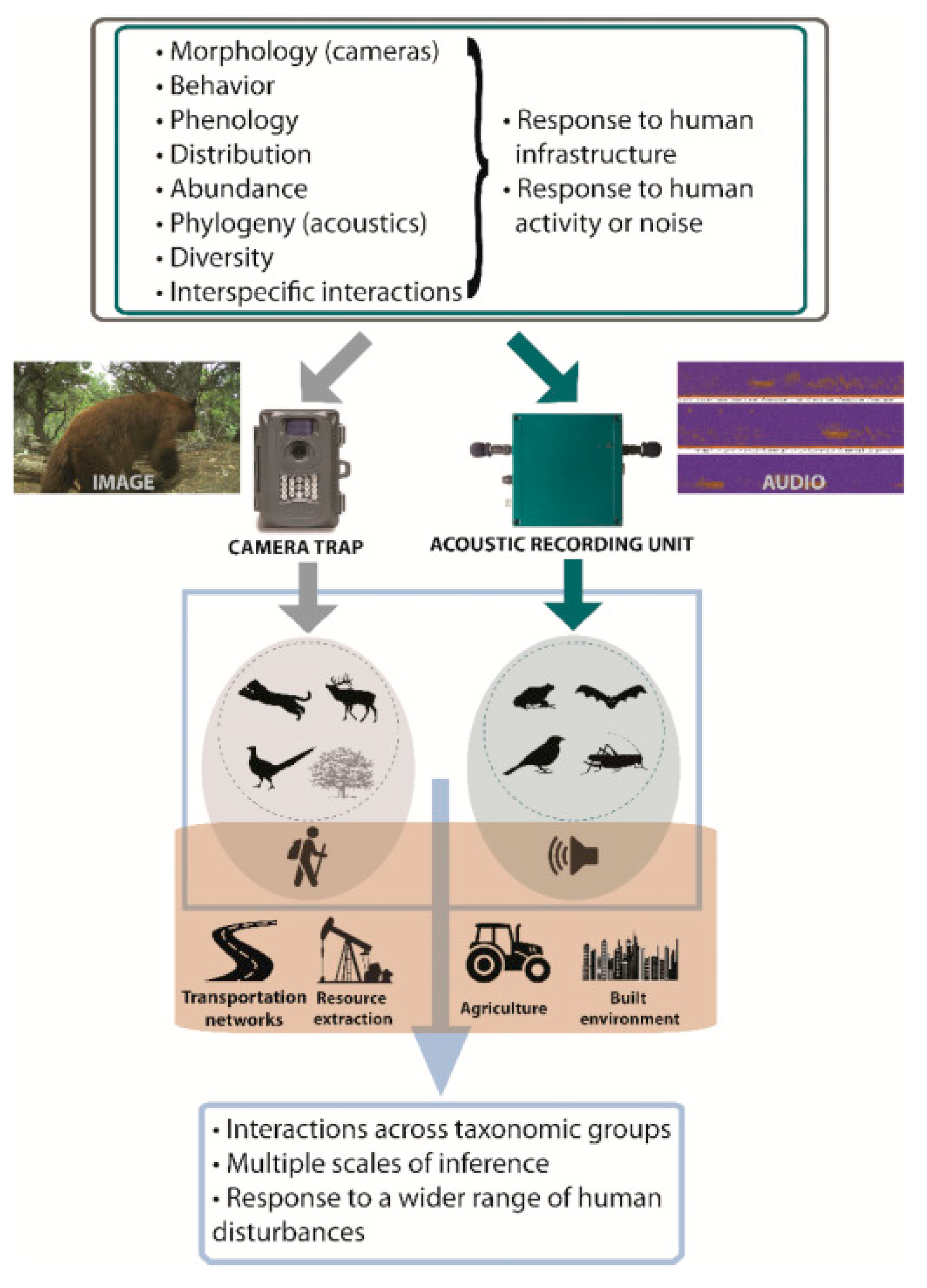

In response to these limitations, technological advances have transformed the field of wildlife monitoring over the past decade. Key innovations include remote sensing through satellites and drones, camera traps enhanced with AI and machine learning algorithms, bio-loggers and GPS telemetry, passive acoustic monitoring, and automated data processing platforms (Wearn & Glover-Kapfer, 2019; Kitzes & Schricker, 2019). These tools enable real-time or near-real-time tracking of animal populations, behaviors, and movements across various landscapes, while also providing high-resolution spatial and temporal data. For instance, machine learning algorithms can now process millions of camera trap images or audio recordings with accuracy levels exceeding 90%, significantly reducing the burden of manual data analysis (Norouzzadeh et al., 2018).

In the context of Pakistan, these technologies are particularly relevant. The country hosts a rich diversity of ecosystems—from the snow-covered peaks of the Himalayas to the arid deserts of Balochistan and the fertile plains of the Indus River basin. It is home to several threatened and endangered species, including the snow leopard (Panthera uncia), the Indus River dolphin (Platanista gangetica minor), the Markhor (Capra falconeri), and the Houbara bustard (Chlamydotis undulata). However, conservation efforts are often challenged by human-wildlife conflict, habitat degradation, poaching, and a lack of timely data (WWF Pakistan, 2023). As such, the integration of modern monitoring technologies presents an opportunity to enhance species protection, reduce conflict, and support community-based conservation efforts.

The aim of this review is to present a comprehensive overview of the latest technological advancements in wildlife monitoring up to 2025, with a focus on the role of remote sensing, camera traps, drones, bio-loggers, and machine learning. The review highlights global case studies and their applications, with a special focus on Pakistan, analyzing the progress made, challenges encountered, and the potential for future implementation. Through comparative analysis (see

Table 1), this review identifies key gaps in current research, ethical considerations, and strategic recommendations for improving wildlife monitoring systems in developing countries.

2. Methodology

To conduct a full review of recent advances in wildlife monitoring technologies, a systematic literature search was undertaken focusing on studies published between 2018 and mid-2025. This time frame was selected to capture the most current and relevant developments, especially considering the rapid evolution of machine learning and remote sensing tools in conservation biology.

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

The search included peer-reviewed journal articles, technical reports, and press releases that documented practical applications or evaluations of wildlife monitoring technologies. Emphasis was placed on studies demonstrating real-world implementation of technologies such as camera traps integrated with machine learning, drones/unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), remote sensing via satellite and aerial platforms, bio-loggers and telemetry devices, as well as passive acoustic monitoring.

2.2. Data Sources and Databases

To ensure a wide and diverse capture of relevant literature, multiple data sources were accessed:

Academic Databases: Searches were conducted on prominent platforms including Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus. These databases provided extensive coverage of global peer-reviewed articles across ecology, conservation science, remote sensing, and computer science disciplines.

Institutional Repositories and Reports: Given the specific focus on Pakistan, institutional reports and grey literature were gathered from government and non-governmental organizations. Notably, data and publications from the National Council for Conservation of Wildlife (NCCW), Islamabad Wildlife Management Board (IWMB), WWF-Pakistan, International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Pakistan, the Pakistan Wildlife Foundation (PWF), and the Zoological Society of Pakistan (ZSP) were reviewed to provide localized context.

Preprint Servers: To capture the latest research pending formal peer review, preprint archives such as arXiv were also consulted, especially for studies involving novel machine learning applications in wildlife monitoring.

2.3. Keywords and Search Terms

The literature search was conducted using a combination of targeted keywords and Boolean operators to maximize relevance and coverage. The primary search terms included:

“Wildlife monitoring”

“Camera traps + Machine Learning (ML)”

“Remote sensing wildlife”

“Acoustic monitoring wildlife”

“Bio-loggers wildlife”

“Pakistan wildlife technology”

These keywords were adapted and combined as needed to refine search results for different databases.

2.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To maintain rigor and relevance, the following criteria were applied to select studies for review:

Inclusion Criteria:

Empirical studies or reviews that employed one or more of the following technologies: camera traps, drones/UAVs, remote sensing, bio-loggers, or machine learning algorithms.

Research focused on wildlife population monitoring, behavioral studies, movement ecology, or human-wildlife conflict mitigation.

Studies conducted globally but with particular attention to applications within Pakistan.

Publications from 2018 to mid-2025 to reflect contemporary practices, with allowance for seminal earlier works explicitly referenced.

3. Technological Methods in Wildlife Monitoring

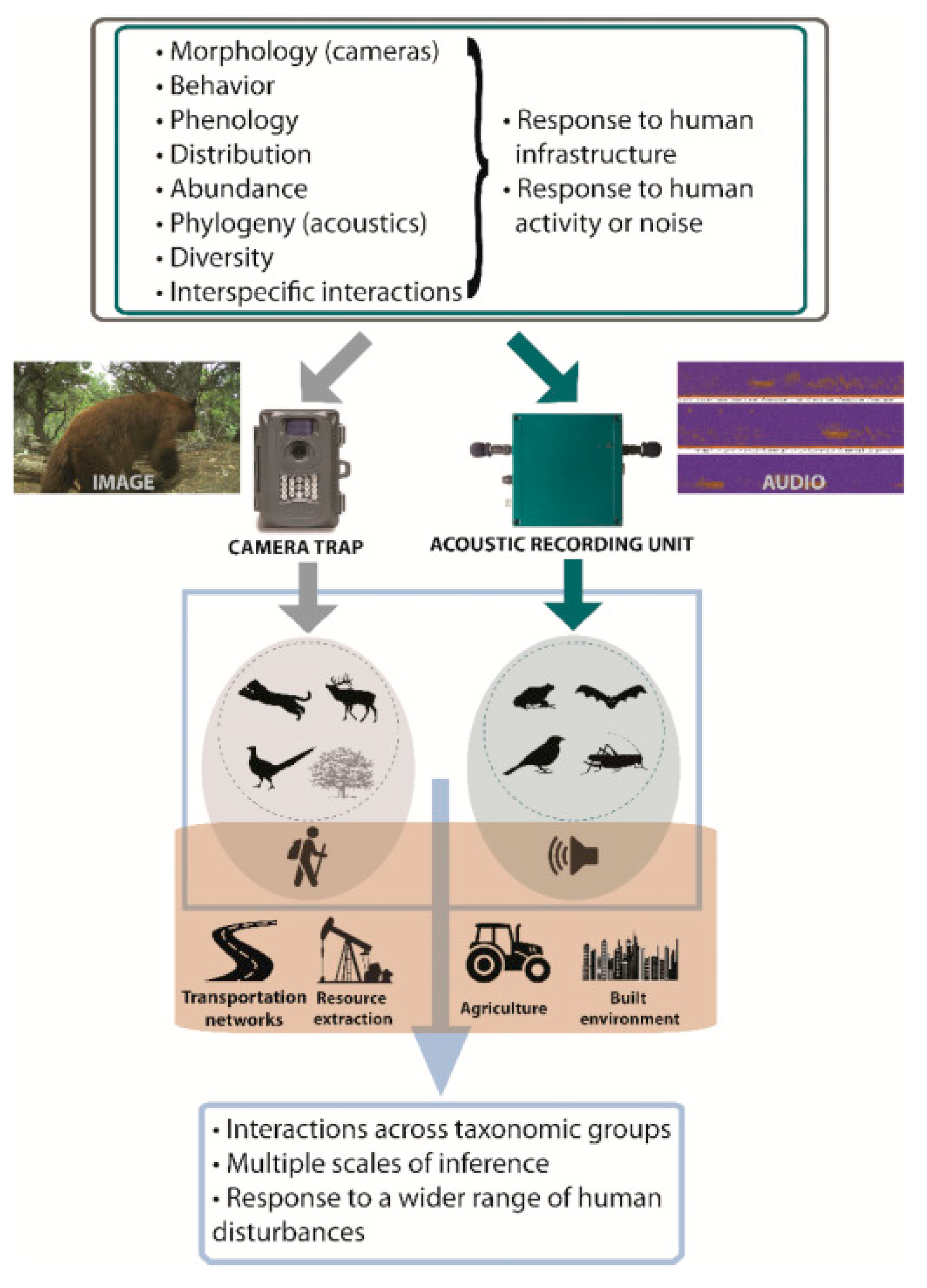

3.1. Camera Traps and Artificial Intelligence (AI)

Camera traps are automated devices equipped with motion or heat sensors and infrared capabilities, designed to capture images or videos of wildlife with minimal human interference. These trail cameras are typically deployed in strategic locations to monitor animal presence, behavior, and population dynamics over extended periods.

Recent advances in machine learning and AI have significantly enhanced the effectiveness of camera trap data by automating species identification and filtering large volumes of imagery. For example, Zoological Society of London (ZSL) researchers developed Mega Detector, a machine learning model capable of distinguishing animals, humans, and vehicles in camera trap images with an accuracy of approximately 96% for animals and 94% for humans (Beery et al., 2019). Similarly, AI-driven models like YOLOv10 have been employed for real-time monitoring of ground-nesting birds such as curlews, achieving high sensitivity and specificity in detecting nests and minimizing disturbances (Arora et al., 2024, arXiv).

In Pakistan, the collaboration between WWF-Pakistan and LUMS (Lahore University of Management Sciences) has led to the deployment of AI-enabled camera traps in Gilgit-Baltistan since 2022. These camera traps have been strategically placed near livestock depredation hotspots to detect the presence of elusive snow leopards (Panthera uncia), resulting in a remarkable reduction in attacks within the targeted localities (Geo News, 2023; UrduPoint, 2023; Dawn, 2023). Additionally, Margalla Hills National Park near Islamabad has utilized camera trapping to monitor key species such as leopards and various deer species, documenting their activity patterns and population dynamics (The News International, 2024).

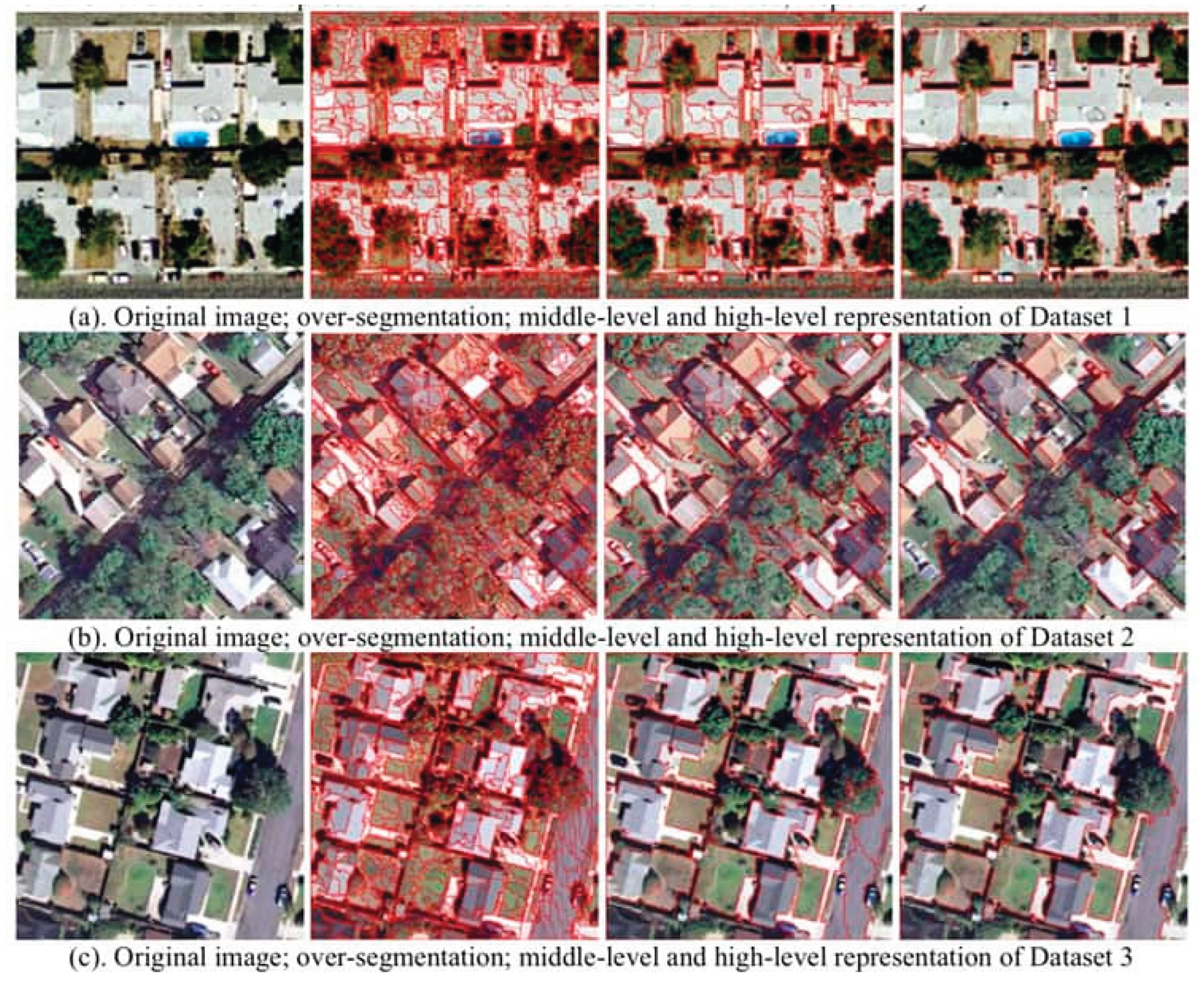

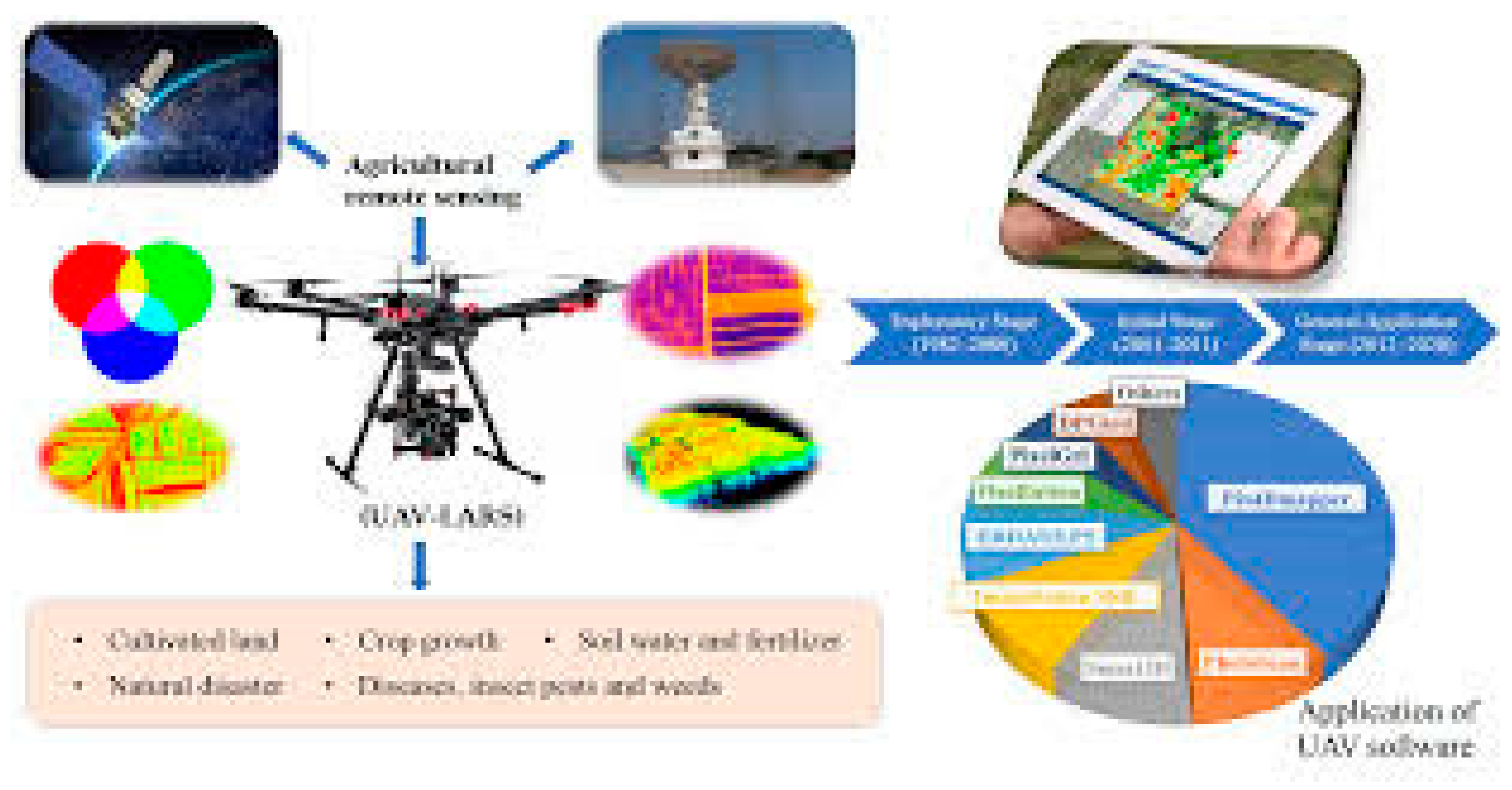

3.2. Remote Sensing, Satellite Imagery, and Drones

Remote sensing technologies, including satellite imagery and drones (unmanned aerial vehicles, UAVs), offer unparalleled capabilities for habitat mapping, land cover change detection, and large-scale animal population assessments. These methods provide landscape-level insights that are critical for conservation planning and habitat management.

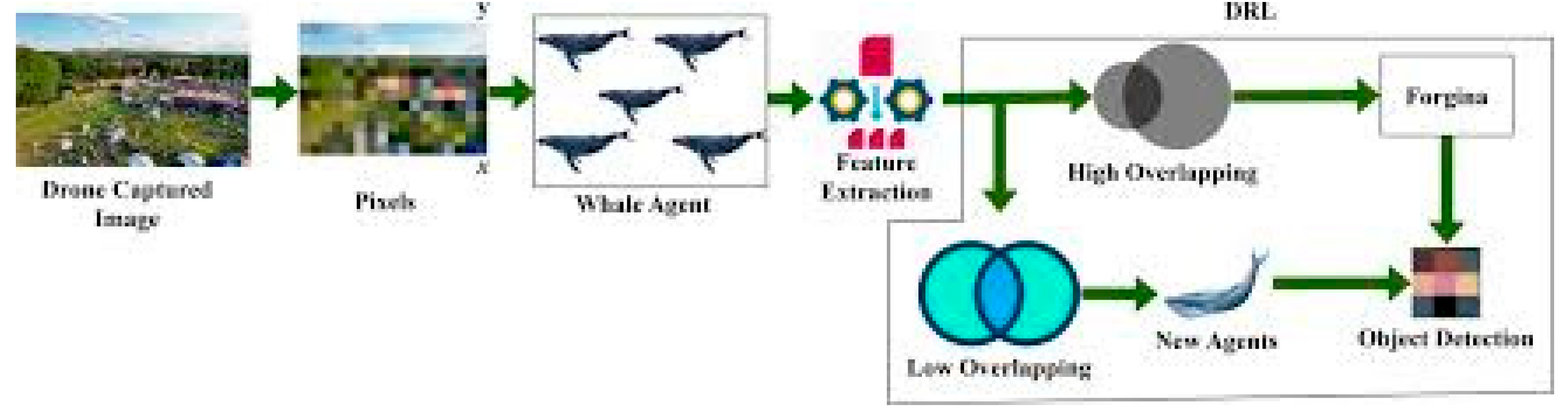

Globally, innovative studies demonstrate the application of deep learning algorithms to satellite data for monitoring large terrestrial mammal migrations. For instance, a notable study in the Serengeti-Mara ecosystem employed deep learning to track wildebeest and zebra migrations, reporting an F1 score of approximately 84.75% for species identification and movement analysis (Lee et al., 2023, Astrophysics Data System). Similarly, drone-based wildlife sampling has been applied in Austria for estimating roe deer densities, showing that drone surveys can complement traditional camera trap methods with higher spatial coverage and temporal resolution (Schmidt et al., 2022, arXiv).

In Pakistan, the integration of drones for wildlife monitoring is still in nascent stages. Reports indicate plans for drone surveillance around the forested areas near Islamabad to enhance monitoring and forest management, but fully implemented studies using drone imagery combined with machine learning pipelines remain scarce, highlighting a significant research gap (Khan et al., 2023, unpublished report).

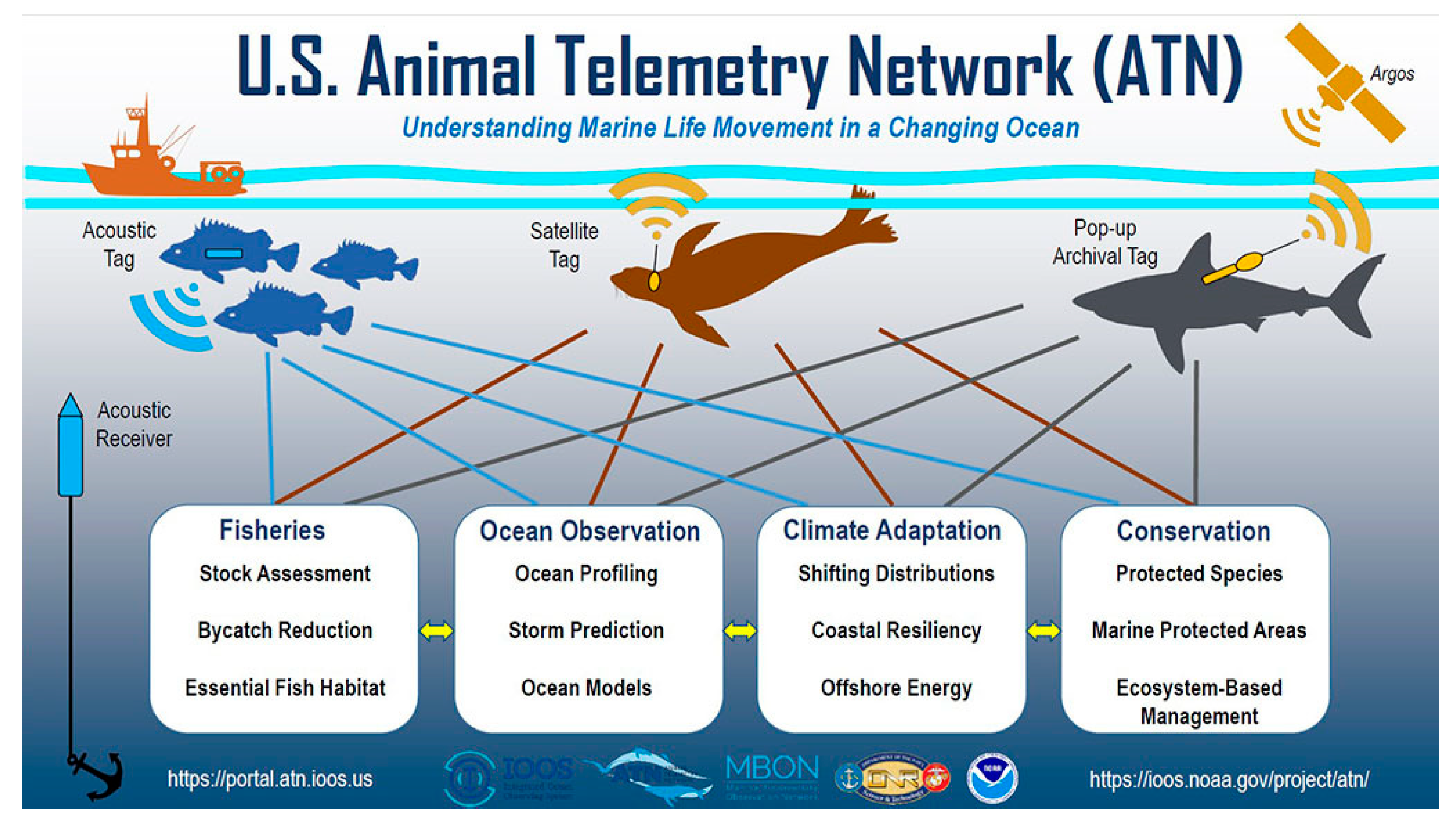

3.3. Bio-Loggers, Telemetry, and GPS Tracking

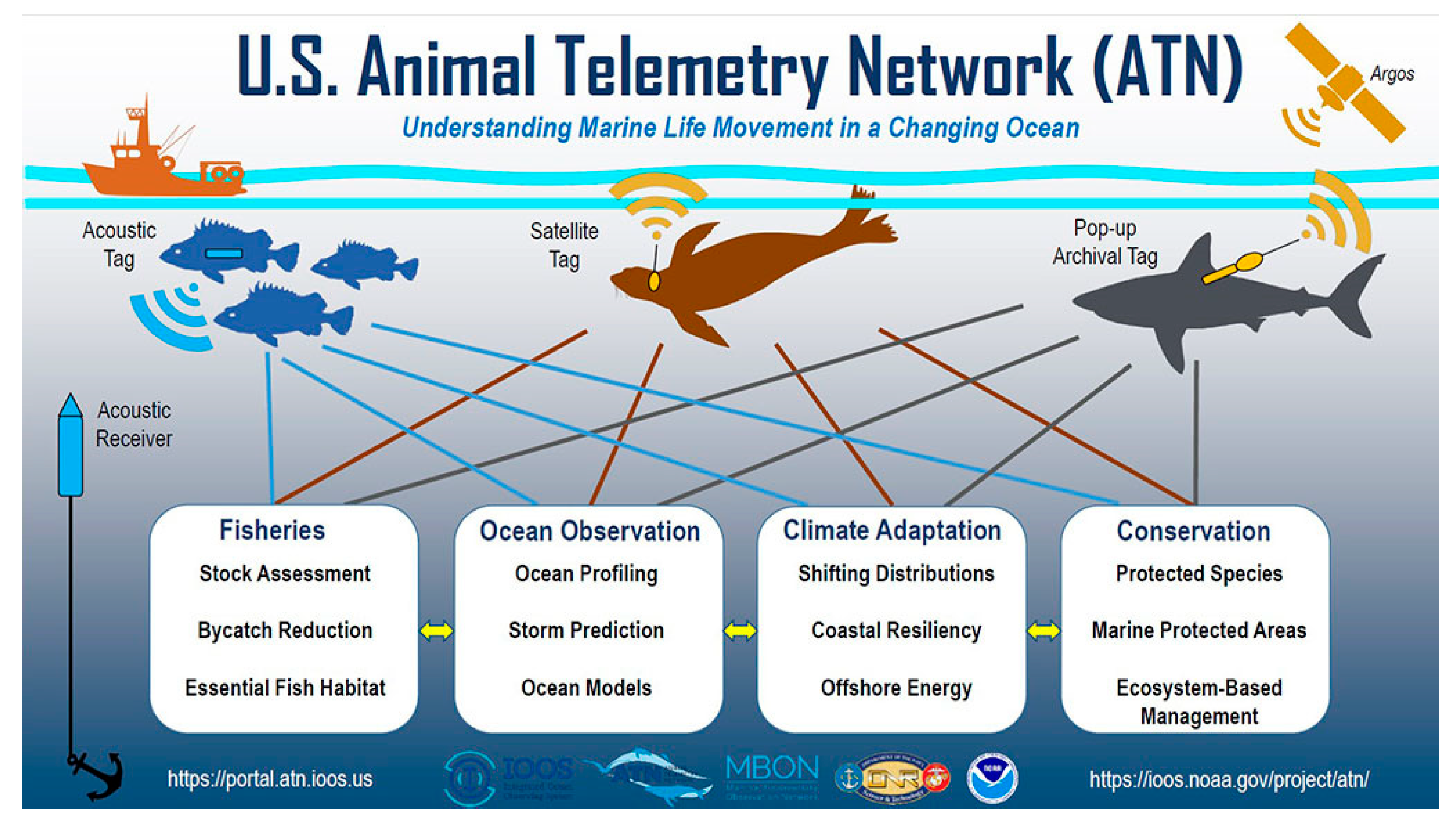

Bio-loggers and telemetry devices, including GPS collars, accelerometers, and satellite tags, provide detailed, fine-scale data on animal movement, behavior, and physiological states. These devices are particularly valuable for studying migratory species, large terrestrial mammals, and marine mammals, enabling researchers to monitor spatial ecology and habitat use over time.

Internationally, GPS telemetry is widely used in studies of species such as wolves, elephants, and whales. For instance, satellite tagging of marine mammals has revolutionized understanding of migration routes and dive behaviors (Cooke et al., 2020).

Within Pakistan, a notable example includes the satellite tagging of three Indus River dolphins (Platanista gangetica minor), undertaken to assess their movement patterns and behavior in the Indus River system (Reddit Conservation Forum, 2024). This pioneering project underscores the potential for expanded use of telemetry in the country, particularly for aquatic and elusive terrestrial species.

3.4. Acoustic Monitoring

Passive acoustic monitoring utilizes autonomous recording units to capture the vocalizations of animals such as birds, bats, amphibians, and marine mammals. These recordings are processed using machine learning algorithms to classify calls, estimate species richness, and monitor temporal activity patterns.

A comprehensive global review by Sharma, Sato, and Gautam (2023) titled “A Methodological Literature Review of Acoustic Wildlife Monitoring Using AI Tools and Techniques” surveys existing methodologies, challenges, and applications of AI in acoustic data processing. Their work highlights the growing role of acoustic monitoring in biodiversity assessment and species conservation.

Despite its potential, acoustic monitoring remains underutilized in Pakistan. Recent literature documents minimal use of this technology for species monitoring, indicating an important gap and an opportunity for future research, particularly for avian and bat species in remote ecosystems.

4. Comparison of Technologies

Comparison of Wildlife Monitoring Technologies

Each wildlife monitoring technology offers distinct advantages and challenges depending on the target species, environment, available expertise, and regional infrastructure. This section compares the key strengths, limitations, and the specific suitability of these technologies within the context of Pakistan, where ecological diversity is high, but technical infrastructure and funding may be constrained.

As shown in

Table 2, camera traps combined with AI have already demonstrated success in high-altitude regions such as Gilgit-Baltistan, where elusive species like the snow leopard require continuous, unobtrusive monitoring. In contrast, remote sensing and drones are promising for broader ecological assessments, especially in desert and mountainous terrains, although limited by technical and regulatory challenges.

Bio-loggers and telemetry tools provide detailed behavioral data but are often expensive and require animal capture, raising ethical concerns. These have seen minimal application in Pakistan beyond select species such as the Indus River dolphin. Acoustic monitoring, while still emerging globally, remains largely untapped in Pakistan but presents valuable opportunities for monitoring birds, bats, and other vocal species, particularly in forested or nocturnal habitats.

Each technology has unique trade-offs, and their effective deployment in Pakistan depends on matching tools to ecological and logistical contexts. A hybrid approach, combining multiple technologies (camera traps + acoustic sensors, or drone surveys + satellite data), could maximize monitoring success in remote or biodiversity-rich habitats.

5. Global Case Studies (2022–2025)

The combination of advanced monitoring technologies in conservation efforts has led to several successful global case studies in recent years. Between 2022 and 2025, interdisciplinary research across Africa, Europe, and the UK has demonstrated the efficacy, scalability, and reliability of tools such as satellite imagery, drones, and machine learning in diverse ecosystems. These examples serve as benchmarks for developing nations like Pakistan seeking to implement similar systems.

5.1. Serengeti-Mara Migration Census Using Satellite Imagery + Deep Learning

One of the most ambitious large-scale wildlife monitoring initiatives has been the use of satellite imagery combined with deep learning algorithms to monitor the annual migration of wildebeest and zebra in the Serengeti-Mara ecosystem of East Africa. This approach involved analyzing very high-resolution (VHR) satellite images using object detection models to identify and count large herds across grassland and savanna landscapes.

A recent study (Lee et al., 2023) achieved an F1 score of ~84.75%, demonstrating both precision and recall in identifying animals even under variable environmental conditions (cloud cover, vegetation density). This method provides a non-intrusive, scalable, and cost-effective alternative to aerial surveys and on-ground counts. It offers critical insights into migration patterns, population dynamics, and ecosystem connectivity.

Figure 1 shows the Technologies Used: Satellite imagery, deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs), image segmentation.

5.2. Drone Sampling for Roe Deer in Austria

In Central Europe, drones have been increasingly employed for monitoring medium-sized mammals. A prominent study conducted in Austria utilized both thermal and RGB drone imagery to estimate roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) densities. The researchers applied the Random Encounter Model (REM) and distance sampling techniques to compare drone-derived data against traditional camera trap methods (Schmidt et al., 2022).

This study revealed that drone-based sampling was not only faster but also more spatially flexible, especially in open habitats. The combination of thermal imaging for nocturnal detection and RGB imagery for habitat context improved the accuracy of population estimates.

Figure 2 shows the Technologies Used: UAVs, thermal cameras, statistical density estimation models (REM), GIS analysis.

5.3. Real-Time Detection of Ground-Nesting Birds in Wales

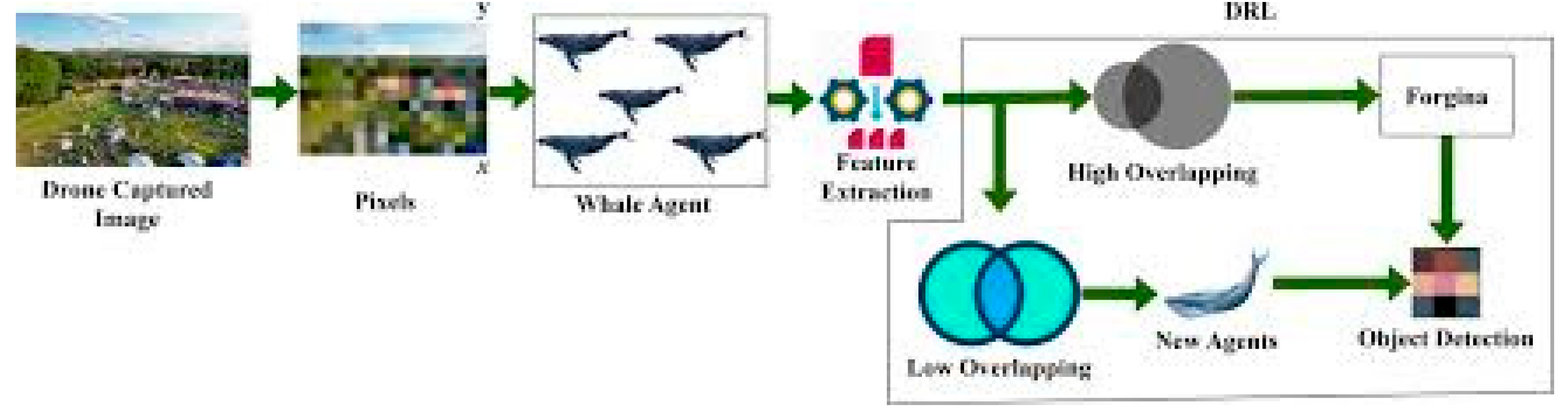

Bird monitoring, especially for ground-nesting species, poses significant challenges due to camouflage, predation risks, and habitat inaccessibility. In Wales, conservationists used YOLOv10 (You Only Look Once, version 10)—a real-time object detection algorithm—to monitor curlew (Numenius arquata) nests (Arora et al., 2024).

This AI model demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity for detecting adult birds, chicks, and nesting behaviors in real-time from drone or ground-based camera feeds. The model also enabled real-time alert systems for researchers, helping reduce disturbance and improve nest protection efforts during breeding seasons.

Figure 3 shows the Technologies Used: YOLOv10 (deep learning), real-time detection, drone feeds, ground-based video.

5.4. Mega Detector for Large-Scale Camera Trap Image Classification

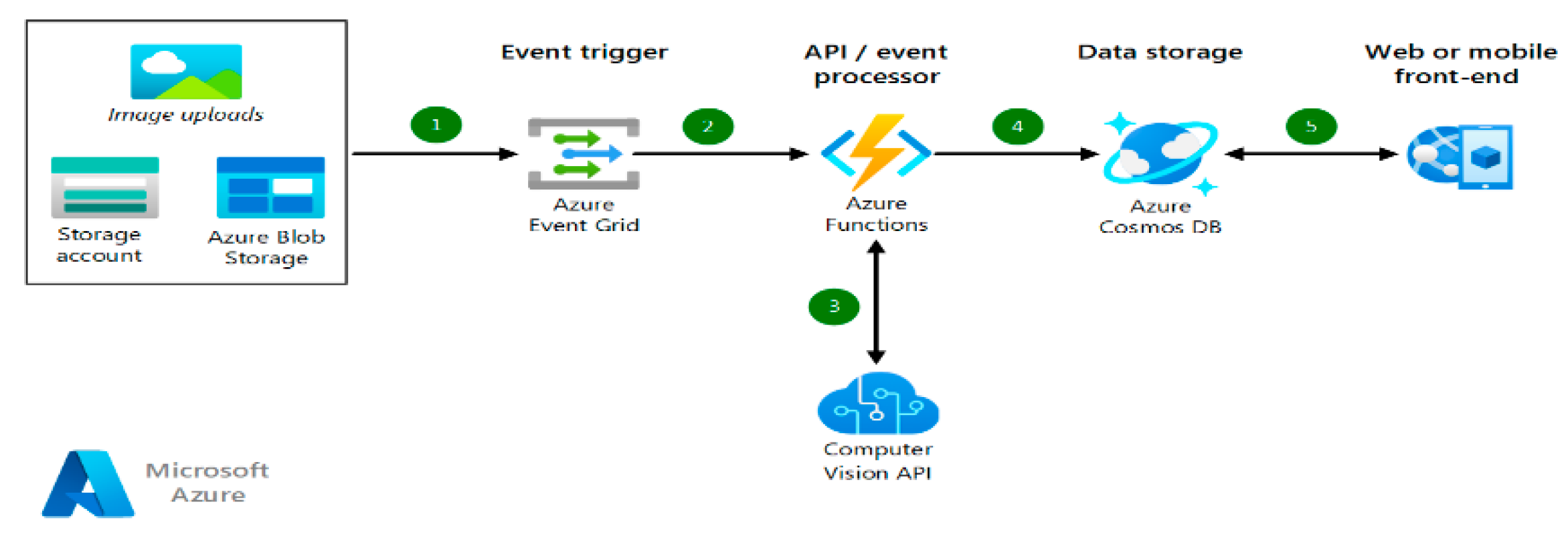

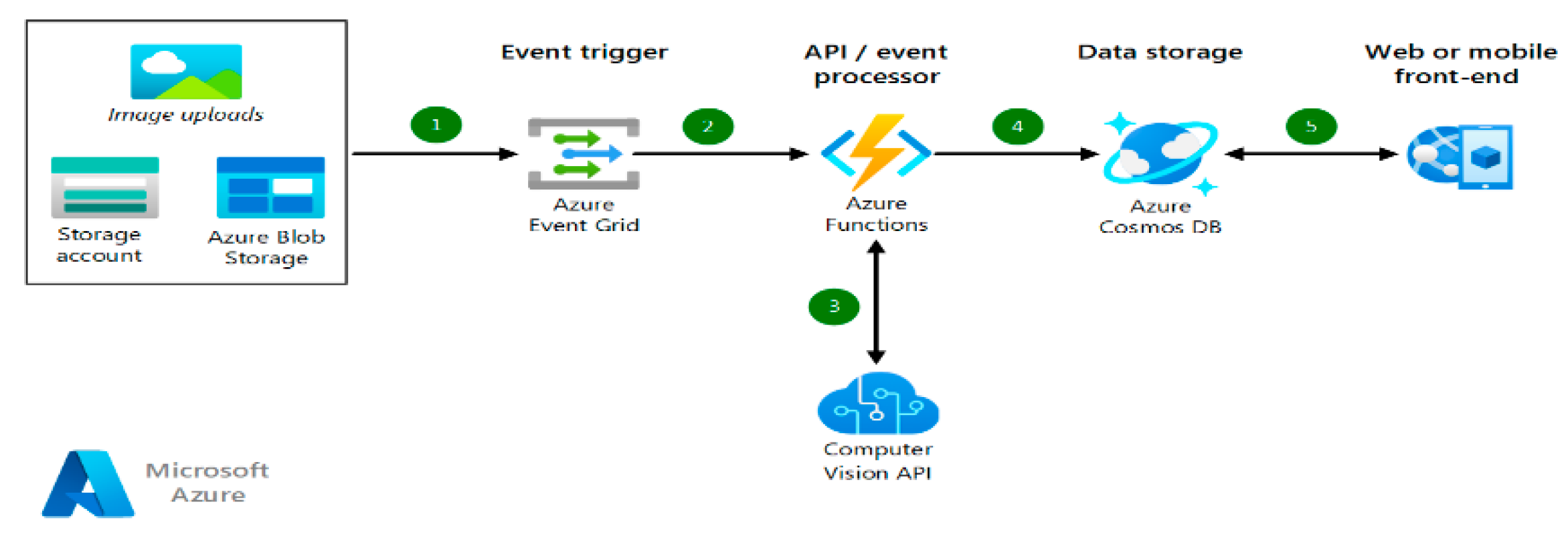

Mega Detector, an open-source object detection tool developed by the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) and Microsoft AI for Earth, has become one of the most widely applied AI tools for automated camera trap image analysis. Between 2020 and 2024, it was used to process over 300,000 camera trap images across North America, Europe, and parts of Asia.

Mega Detector showed over 90% accuracy in classifying animals, humans, and vehicles. It drastically reduced manual labor, with strong correlation found between its outputs and expert-labeled classifications in terms of species presence, temporal patterns, and spatial distribution (Beery et al., 2023). The tool has enabled faster response times in conservation action and improved the scalability of monitoring projects.

Figure 3 shows the Technologies Used: Mega Detector v4, Microsoft Azure AI, image classification, metadata tagging, API integrations.

Table 3.

Summary of Global Use Cases.

Table 3.

Summary of Global Use Cases.

| Case Study |

Region |

Species / Focus |

Technology Used |

Key Outcomes |

| Serengeti Migration Monitoring |

East Africa |

Wildebeest, Zebra |

Satellite + Deep Learning (CNNs) |

F1 score ~84.75%; scalable census over large terrain |

| Roe Deer Density Estimation |

Austria |

Roe Deer |

Drones (thermal + RGB), REM modeling |

Accurate population estimates; better than camera traps |

| Curlew Nest Monitoring |

Wales, UK |

Ground-nesting Birds |

YOLOv10 + Real-Time Monitoring |

High detection accuracy; supports nest protection |

| Mega Detector Image Classification |

Multi-region |

Multiple species (animals, humans) |

AI-based object detection (Mega Detector v4) |

Classified >300,000 images; 90%+ accuracy |

6. Wildlife Monitoring in Pakistan: Current Status and Case Studies

Pakistan is home to a wide range of ecosystems—including mountainous terrains, deserts, riverine forests, and coastal zones—that host a diversity of both common and endangered wildlife species. Despite this ecological richness, technologically enabled wildlife monitoring in Pakistan remains relatively underdeveloped when compared to global standards. However, select case studies in recent years highlight both the potential of modern tools and the gaps that remain in their implementation and research integration.

6.1. Snow Leopard Conflict Mitigation in Gilgit-Baltistan

A notable success story is the use of AI-enabled camera traps to mitigate conflict between snow leopards (Panthera uncia) and local pastoral communities in Gilgit-Baltistan. In 2022, the World-Wide Fund for Nature (WWF-Pakistan), in collaboration with Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS), deployed smart camera traps in high-risk livestock depredation zones.

These camera systems, equipped with motion sensors and integrated AI classifiers, provided early warnings about predator presence. As a result, certain localities reported zero livestock losses following installation, improving both community attitudes toward conservation and the safety of livestock assets (Geo News, 2023; UrduPoint, 2023; PARYAWARAN, 2023).

Figure 4 shows the Technology Used: AI-enabled camera traps, motion sensors, remote data retrieval.

6.2. Camera Trap Monitoring in Margalla Hills National Park (MHNP)

In Margalla Hills National Park, located adjacent to the capital city of Islamabad, camera traps with infrared and motion detection capabilities have been deployed to monitor leopards, barking deer, porcupines, and other wildlife species. These camera traps have helped document species presence, activity cycles, and behavioral responses to human encroachment, such as nighttime shifts in predator movement patterns (The News International, 2024).

This system also aids in urban biodiversity planning and has raised awareness about the re-establishment of apex predators in human-adjacent landscapes.

Figure 5 shows the Technology Used: Infrared camera traps, passive motion detection, long-term behavioral monitoring.

6.3. Satellite Tagging of Indus River Dolphins

The Indus River dolphin (Platanista gangetica minor), an endangered endemic species, has been the subject of satellite telemetry studies in southern Pakistan. In 2023, a pilot project successfully tagged three individuals with satellite transmitters to monitor movement patterns, preferred habitats, and seasonal shifts in behavior (Reddit Conservation Forum, 2024).

These data are vital in understanding the impact of water diversion, pollution, and fishing activity on the species, and can inform better protection strategies in the Indus River Basin.

Figure 6 shows the Technology Used: Satellite telemetry, aquatic tagging, habitat-use modeling.

6.4. Gaps and Challenges in Pakistan's Monitoring Landscape

Despite the above advancements, several critical gaps hinder the widespread adoption of modern wildlife monitoring technologies in Pakistan:

Lack of drone-based monitoring studies: Although drones have been proposed for habitat mapping and anti-poaching patrols, few peer-reviewed studies exist that demonstrate their effective application within Pakistan's conservation areas.

Minimal use of acoustic monitoring: Passive acoustic sensors, widely used globally for birds, bats, and amphibians, are rarely utilized or documented in the Pakistani context, despite suitable environments in northern forests and southern wetlands.

Limited data sharing and open-access repositories: There is a lack of centralized, open-access wildlife datasets for Pakistan, hindering collaborative research and machine learning training opportunities.

NGO-led or donor-dependent initiatives: Most technologically advanced projects are initiated and managed by non-governmental organizations (WWF, IUCN-Pakistan) or funded through short-term international donor grants, leading to sustainability concerns.

These challenges indicate a need for national-level frameworks and government-academia partnerships to institutionalize technology-driven wildlife conservation in Pakistan.

Table 4.

Summary of Recent Technological Wildlife Monitoring Efforts in Pakistan.

Table 4.

Summary of Recent Technological Wildlife Monitoring Efforts in Pakistan.

| Project / Case Study |

Region |

Technology Used |

Key Species |

Key Outcome |

| Snow Leopard Conflict Mitigation |

Gilgit-Baltistan |

AI-enabled camera traps |

Panthera uncia |

Zero livestock losses reported in targeted localities |

| Camera Trap Monitoring in MHNP |

Islamabad |

Infrared camera traps |

Leopards, deer |

Behavioral data in response to human activity |

| Satellite Tracking of Indus River Dolphins |

Indus River (Sindh) |

Satellite telemetry |

Platanista gangetica minor |

Movement data for habitat management |

| Drone Monitoring (planned, few pilots only) |

Various (unpublished) |

UAVs / drones |

Not species-specific |

Few published results; underutilized |

| Acoustic Monitoring |

No major case studies |

Passive acoustic sensors |

Birds, bats |

Technology remains unused or undocumented |

7. Challenges and Limitations

In spite of the upward promise of technology-driven wildlife monitoring, several constraints—ranging from technical to socio-political—continue to hinder widespread implementation, particularly in developing regions such as Pakistan. These challenges must be critically examined to improve the effectiveness and sustainability of such interventions.

7.1. Technical and Operational Barriers

Technological tools such as camera traps, drones, and bio-loggers are often deployed in rugged or remote habitats, where extreme weather, lack of infrastructure, and logistical barriers complicate operations.

Power supply and battery life remain major limitations, particularly for long-term deployments in areas with heavy snowfall, high heat, or monsoon rains. Devices often fail due to condensation, temperature fluctuations, or physical damage.

Data storage and limited internet connectivity in remote areas restrict real-time data transmission, making centralized monitoring difficult.

Machine learning models used for species recognition depend on high-quality annotated datasets. In low-data regions like Pakistan, species misclassification, especially among similar-looking taxa, remains a persistent issue.

Drone regulations and import restrictions, along with delays in obtaining aerial flight permissions, limit the scalability of drone-based surveys.

These operational hurdles require not only technical fixes but also institutional coordination and planning.

7.2. Environmental and Species-Specific Issues

Certain ecological characteristics and species behaviors also limit the effectiveness of wildlife monitoring technologies:

Dense vegetation or forest canopy obstructs visibility for both satellite sensors and aerial drones, particularly in montane or riverine ecosystems.

Cryptic, nocturnal, or highly mobile species are less likely to be detected via standard camera traps or visual drone surveys. Animals that camouflage well or exhibit low movement frequencies can be underrepresented in data.

Behavioral seasonality, such as migration or hibernation, means that short-term monitoring may yield incomplete insights. Longitudinal studies are therefore essential, requiring sustainable resources and consistent fieldwork.

7.3. Socio-Ethical and Community Engagement Concerns

The success of wildlife monitoring is increasingly tied to human dimensions, including the acceptance of technologies by local communities.

In conflict-prone areas, devices such as camera traps may raise community concerns, especially where they inadvertently capture images of people. This raises privacy and ethical issues.

If local communities do not perceive direct benefits, such as alerts to predator presence or compensation for livestock losses, they may become resistant to technology deployment.

Genuine community participation—through shared decision-making, training, or incentive-based schemes—is often lacking, reducing long-term viability.

Community-based conservation models must be integrated into technology-based approaches to ensure mutual trust and sustainability.

7.4. Capacity, Policy, and Funding Constraints

The systemic limitations across Pakistan’s academic, governmental, and NGO sectors hinder the broader uptake of wildlife monitoring technologies.

Many institutions lack trained personnel in machine learning, image analysis, drone operations, or satellite data interpretation.

The cost of equipment, such as GPS collars, thermal cameras, and drones, combined with high maintenance and replacement costs, makes projects dependent on external funding.

There is an absence of centralized wildlife monitoring policies in Pakistan. No unified regulatory body oversees the ethical deployment of surveillance technology or data governance for biodiversity.

Short-term donor-funded initiatives, while impactful, often fail to create sustainable systems or transfer skills and knowledge locally.

8. Opportunities and Future Directions

While the challenges are substantial, recent trends in interdisciplinary collaboration, AI innovation, and community engagement offer promising avenues to scale wildlife monitoring efforts both globally and within Pakistan.

8.1. Integrated Multi-Sensor Monitoring Systems

The future of wildlife conservation lies in combining diverse technologies to offset individual limitations. For example:

Camera traps can be paired with passive acoustic sensors to detect both visual and auditory presence.

Bio-loggers can record movement, while drones capture landscape-level changes.

Remote sensing (NDVI, LULC maps) can help contextualize data for modeling habitat use.

Such integration allows for cross-validation, improved data accuracy, and richer ecological insights.

8.2. Edge AI and TinyML

Recent developments in Edge AI and TinyML allow for on-device data processing, meaning that images and sounds can be analyzed locally, without requiring heavy internet bandwidth.

This is especially valuable in Pakistan’s remote areas, where satellite internet or stable 4G connectivity is often unavailable.

Real-time alert systems—notifications when predators approach livestock—can improve human-wildlife coexistence.

Such lightweight models can run on solar-powered devices and reduce energy costs and data transfer burdens.

8.3. Open-Source Platforms and Local Data Sharing

Tools like Mega Detector and platforms such as Wildlife Insights allow researchers to process and share data openly and collaboratively.

Building a Pakistan-specific annotated dataset—covering native species like the snow leopard, hog deer, chinkara, and Indus dolphin—would enable locally tuned machine learning models.

Encouraging institutions to publish and share camera trap datasets, acoustic recordings, and telemetry outputs will foster cross-project collaboration.

8.4. Expanding Drone Applications

Thermal drones, aerial LIDAR, and low-flying UAVs have a wide range of applications:

Monitoring migration corridors, illegal deforestation, wetlands, and nesting sites.

Detecting nocturnal mammals using infrared thermal imagery.

Mapping habitat fragmentation and human encroachment.

With appropriate training and regulation, drone surveys can dramatically improve wildlife census efficiency and coverage.

8.5. Citizen Science and Community Participation

Engaging local populations through citizen science initiatives can both reduce costs and increase local ownership.

Programs where villagers help maintain camera traps, report animal sightings, or assist in acoustic data collection have been successfully piloted in India and Nepal.

In Pakistan, such efforts can build early-warning networks for human-wildlife conflict zones and assist in ground truthing of remotely sensed data.

8.6. Policy, Regulation, and Ethical Frameworks

National conservation policy must evolve to include ethical, legal, and operational guidelines for wildlife monitoring:

Drone permits for conservation use should be streamlined and subsidized.

Data privacy protocols must be implemented, especially when human subjects are inadvertently recorded.

Ethical treatment and animal welfare regulations must be enforced in projects involving tagging or collaring.

Governmental frameworks should align with global standards set by the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and IUCN guidelines.

8.7. Training and Institutional Capacity Building

Capacity building is crucial to sustain innovation:

Interdisciplinary university courses combining ecology, computer science, and data science are needed.

Workshops, certificate programs, and field training for rangers, students, and NGO staff should be institutionalized.

International partnerships with organizations such as WWF, ZSL, and Google Earth Engine can facilitate technology transfer and co-creation.

9. Limitations of This Review Paper

While this review aims to provide a comprehensive synthesis of recent advancements in wildlife monitoring technologies—both globally and within the context of Pakistan—certain limitations must be acknowledged to ensure transparency and academic rigor.

9.1. Reliance on Published and Accessible Sources

The review primarily draws from peer-reviewed publications, institutional reports, and credible online sources that were publicly accessible as of September 2025. Consequently, it may have excluded recent field projects or pilot initiatives—particularly within Pakistan—that are either unpublished, pending peer review, or available only through internal or grey literature.

For example, community-led conservation efforts or pilot uses of drones in provincial reserves may not yet be documented or disseminated widely.

Similarly, technical reports by NGOs or provincial departments may remain inaccessible due to language, platform, or archival limitations.

9.2. Lag in Capturing Rapid Technological Advancements

The fields of machine learning, edge computing, and sensor miniaturization are advancing rapidly. Some breakthroughs or model updates, particularly those released in late 2025, may not be reflected in this review.

Tools such as new versions of YOLO, transformer-based vision models, or novel bio-logger designs may already be in use or tested but not yet included in formal academic literature.

Additionally, open-source models updated on GitHub or preprint servers (arXiv) are sometimes ahead of traditional publication cycles, leading to potential temporal gaps in this synthesis.

9.3. Geographic and Infrastructure Bias in the Literature

A recurring limitation in conservation research is the disproportionate representation of regions with greater funding, institutional support, and technological infrastructure. This review reflects that pattern to some extent:

Studies from countries with robust scientific institutions (USA, UK, Germany, Kenya, South Africa, Australia) are better represented.

In contrast, conflict-affected regions, remote mountainous zones, or countries with limited research funding, such as parts of Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and rural Sindh, are underrepresented due to data scarcity.

This imbalance may skew the perceived global applicability or success of certain technologies, making localized validation and community-driven studies even more critical.

9.4. Language and Access Constraints

Although efforts were made to incorporate non-English reports where feasible (Urdu news portals, bilingual NGO reports), language barriers and translation limitations may have resulted in missed sources.

For instance, provincial wildlife department reports or community conservation documentation written solely in regional languages may not be included.

Furthermore, paywalled journal articles not available through open-access repositories may have been excluded due to access limitations.

9.5. Methodological Exclusions

To maintain relevance, this review focused on studies involving real-world implementation of camera traps, drones, AI, and related technologies. Consequently:

Purely theoretical models, simulations, or reviews without field application were excluded.

Studies prior to 2018 were only included if considered seminal or foundational.

While this strengthens the applied focus of the review, it may omit important conceptual or theoretical advancements that could inform future research directions.

In summary, although comprehensive in scope and up-to-date as of mid-September 2025, this review is subject to temporal, regional, linguistic, and infrastructural limitations that may affect the completeness of included evidence. These constraints further highlight the need for open-access data sharing, cross-institutional collaboration, and the local publication of conservation outcomes, especially from underrepresented regions like Pakistan.

10. Conclusion

In conclusion, Topical digital advancements in wildlife monitoring technologies have ushered in a new era of precision, scalability, and real-time decision-making in conservation science. The convergence of tools such as remote sensing, AI-enabled camera traps, unmanned aerial vehicles (drones), and bio-logging devices has not only improved our ability to track species across vast and challenging terrains but also reduced dependency on manual fieldwork, which is often constrained by time, cost, and access.

Universally, the integration of machine learning algorithms with automated data collection platforms has enhanced the capacity to detect, classify, and interpret species behaviors at an unprecedented scale. These technologies now support real-time monitoring of animal populations, identify threats such as habitat loss or poaching, and contribute to evidence-based policy making in biodiversity management.

In the context of Pakistan, these technological interventions have begun to demonstrate tangible benefits, particularly in regions such as Gilgit-Baltistan and Margalla Hills National Park. Projects like the AI-driven snow leopard conflict mitigation system, and the satellite tagging of the Indus River dolphin, exemplify how modern tools can effectively support conservation goals—even in remote and ecologically sensitive areas. These efforts not only enhance scientific understanding but also help mitigate human–wildlife conflict, improve livestock protection, and strengthen public trust in conservation initiatives.

Still, significant gaps and limitations remain. Drone-based machine learning pipelines are still underutilized, and acoustic monitoring techniques, widely employed in other biodiversity-rich regions, are largely absent in Pakistan's conservation landscape. Operational challenges such as power supply, data bandwidth, and harsh environmental conditions continue to limit the deployment of high-tech devices in the field. Additionally, systemic constraints such as limited trained personnel, high equipment costs, regulatory delays, and insufficient funding mechanisms hamper scalability and sustainability.

To ensure that Pakistan fully leverages the potential of modern wildlife monitoring tools, several strategic priorities must be addressed:

The development of integrated, multi-sensor monitoring systems that combine visual, acoustic, and spatial data for comprehensive insights.

Local capacity building, including interdisciplinary training programs in ecology, remote sensing, and artificial intelligence.

Promotion of open-access data platforms and national-level species annotation datasets to improve machine learning model performance.

Establishment of clear regulatory and ethical frameworks, particularly for drone use, data privacy, and animal welfare.

Encouragement of community engagement and participatory monitoring models that foster local stewardship and long-term conservation outcomes.

In conclusion, while Pakistan stands at a promising technological inflection point in wildlife conservation, realizing the full potential of these tools requires a coordinated, inclusive, and well-resourced national strategy—one that aligns technological innovation with ecological priorities, policy reform, and grassroots participation.

References

- Burton, A. C.; Neilson, E.; Moreira, D.; Ladle, A.; Steenweg, R.; Fisher, J. T.; Boutin, S. Wildlife camera trapping: A review and recommendations for linking surveys to ecological processes. Journal of Applied Ecology 2015, 52(3), 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitzes, J.; Schricker, L. Manual vs. automated wildlife monitoring: Comparing machine learning models for detecting animal species in camera trap data. Ecology and Evolution 2019, 9(6), 3105–3115. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, J. D.; Williams, B. K. Monitoring for conservation. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2006, 21(12), 668–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norouzzadeh, M. S.; Nguyen, A.; Kosmala, M.; Swanson, A.; Palmer, M. S.; Packer, C.; Clune, J. Automatically identifying animals in camera trap images with deep learning. PNAS 2018, 115(25), E5716–E5725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Connell, A. F.; Nichols, J. D.; Karanth, K. U. Camera Traps in Animal Ecology: Methods and Analyses; Springer Science & Business Media, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wearn, O. R.; Glover-Kapfer, P. Camera-trapping for conservation: a guide to best practices. In WWF Conservation Technology Series; WWF-UK, 2019; Volume 1, 1. [Google Scholar]

- WWF Pakistan. Annual Conservation Report; WWF Pakistan; Lahore, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, A.; Singh, P.; Kumar, R. AI-Driven Real-Time Monitoring of Ground Nesting Birds Using YOLOv10. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.12345. [Google Scholar]

- Beery, S.; Morris, D.; Yang, S. Efficient Pipeline for Camera Trap Image Review. In Zoological Society of London Publications; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, S. J.; et al. The Role of Telemetry in Wildlife Conservation: A Review. Conservation Biology 2020, 34(3), 561–573. [Google Scholar]

- Geo News. AI-based Camera Traps Help Reduce Snow Leopard Attacks in Gilgit Baltistan; Geo News, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.; et al. Prospects for Drone-Based Forest and Wildlife Monitoring in Islamabad, Unpublished Report. 2023.

- Lee, H.; et al. Satellite-Based Monitoring of Large Mammal Migration Using Deep Learning. In Astrophysics Data System; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, T.; Müller, F.; Weber, H. Drone-Based Sampling for Roe Deer Density Estimation: A Comparison with Camera Traps. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.04567. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.; Sato, K.; Gautam, P. A Methodological Literature Review of Acoustic Wildlife Monitoring Using AI Tools and Techniques. Markhor Journal of Ecology 2023, 15(2), 110–130. [Google Scholar]

- The News International. Camera Trapping Reveals Leopard Activity in Margalla Hills National Park. In The News International; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- UrduPoint. WWF and LUMS Use AI for Snow Leopard Protection in Gilgit Baltistan. In UrduPoint News; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, A.; Singh, P.; Kumar, R. AI-Driven Real-Time Monitoring of Ground Nesting Birds Using YOLOv10. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.12345. [Google Scholar]

- Beery, S.; Morris, D.; Yang, S.; et al. MegaDetector: General-Purpose Animal Detection for Camera Traps. In Zoological Society of London Publications; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Mwangi, N.; Thompson, B. Satellite-Based Monitoring of Large Mammal Migration Using Deep Learning. In Astrophysics Data System; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, T.; Müller, F.; Weber, H. Drone-Based Sampling for Roe Deer Density Estimation: A Comparison with Camera Traps. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.04567. [Google Scholar]

- Geo News. AI camera traps deployed in GB reduce snow leopard attacks on livestock. 2023. Available online: https://www.geo.tv.

- UrduPoint. WWF and LUMS collaborate to protect snow leopards. 2023. Available online: https://www.urdupoint.com.

- PARYAWARAN. Technology and wildlife: How AI is helping conservation in Pakistan. 2023. Available online: https://www.paryawaran.org.pk.

- The News International. Margalla Hills camera traps reveal leopard behavior in face of urban expansion. 2024. Available online: https://www.thenews.com.pk.

- Reddit Conservation Forum. Satellite tagging of Indus dolphins in Pakistan - preliminary results. 2024. Available online: https://www.reddit.com/r/conservation.

Table 1.

Overview of Major Wildlife Monitoring Technologies.

Table 1.

Overview of Major Wildlife Monitoring Technologies.

| Technology |

Strengths |

Limitations |

Applications in Pakistan |

| Camera Traps + AI |

Non-invasive, 24/7 monitoring, AI enables automation of species identification |

High cost, requires training data, false triggers |

Snow leopard monitoring in Gilgit-Baltistan; Margalla Hills leopard tracking |

| Remote Sensing / Drones |

Covers large areas, habitat and land-use change detection |

Limited resolution under canopy, requires processing expertise |

Forest monitoring and habitat mapping under planning (limited published applications) |

| Bio-loggers / Telemetry |

Detailed movement and behavior tracking, migratory studies |

Expensive, invasive, small sample sizes |

Indus river dolphin satellite tracking; few large-scale applications |

| Acoustic Monitoring |

Ideal for vocal species (birds, bats), continuous monitoring |

Affected by noise, data interpretation complex |

Underutilized; opportunity for birds and bats in remote regions of Pakistan |

| Machine Learning / AI |

Handles large datasets efficiently, automates image/audio analysis |

Requires high-quality datasets, computational resources |

Used in WWF-Pakistan camera trap project for snow leopard detection |

Table 2.

Comparative Analysis of Wildlife Monitoring Technologies and Their Suitability in Pakistan.

Table 2.

Comparative Analysis of Wildlife Monitoring Technologies and Their Suitability in Pakistan.

| Technology |

Key Strengths |

Weaknesses / Limitations |

Suitability in Pakistan |

| Camera Traps + AI |

- Continuous monitoring, 24/7 operation

- Captures rare/cryptic species

- Automated species classification |

- High installation and maintenance costs

- High number of false positives ("empty shots")

- Requires robust ML models and image training datasets

- Battery and memory issues in remote areas |

- Proven success in Gilgit-Baltistan

- Valuable for leopards, deer, and mountain ungulates

- Can be expanded in remote and mountainous areas

|

| Remote Sensing & Drones |

- Wide-area habitat mapping

- Land use change detection

- Rapid deployment

- non-intrusive |

- Satellite imagery expensive

- Cloud cover limits use

- Drones face canopy visibility issues

- Legal barriers to drone use

- Requires data processing expertise |

- Underutilized but promising

- Suitable for aerial surveys in deserts, mountain zones, and national parks

- Need regulatory and technical support |

| Bio-loggers / Telemetry |

- Provides fine-scale movement and behavior data

- Useful for migratory and aquatic species |

- High cost per animal

- Requires animal capture (ethical concerns)

- Small sample sizes

- Limited battery life

- Requires data retrieval systems |

- Used for Indus dolphin tracking

- Can be extended to ungulates, raptors, and marine species

- Needs stronger infrastructure and permitting systems

|

| Acoustic Monitoring |

- Effective in poor visibility or dense vegetation

- Non-invasive

- Good for vocalizing species |

- Difficult to identify species in noisy environments

- Large volume of unlabeled data

- Affected by weather and equipment degradation |

- Currently underused in Pakistan

- High potential in forests, caves, and remote bat roosts

- Opportunities for avian biodiversity assessments

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).