1. Introduction

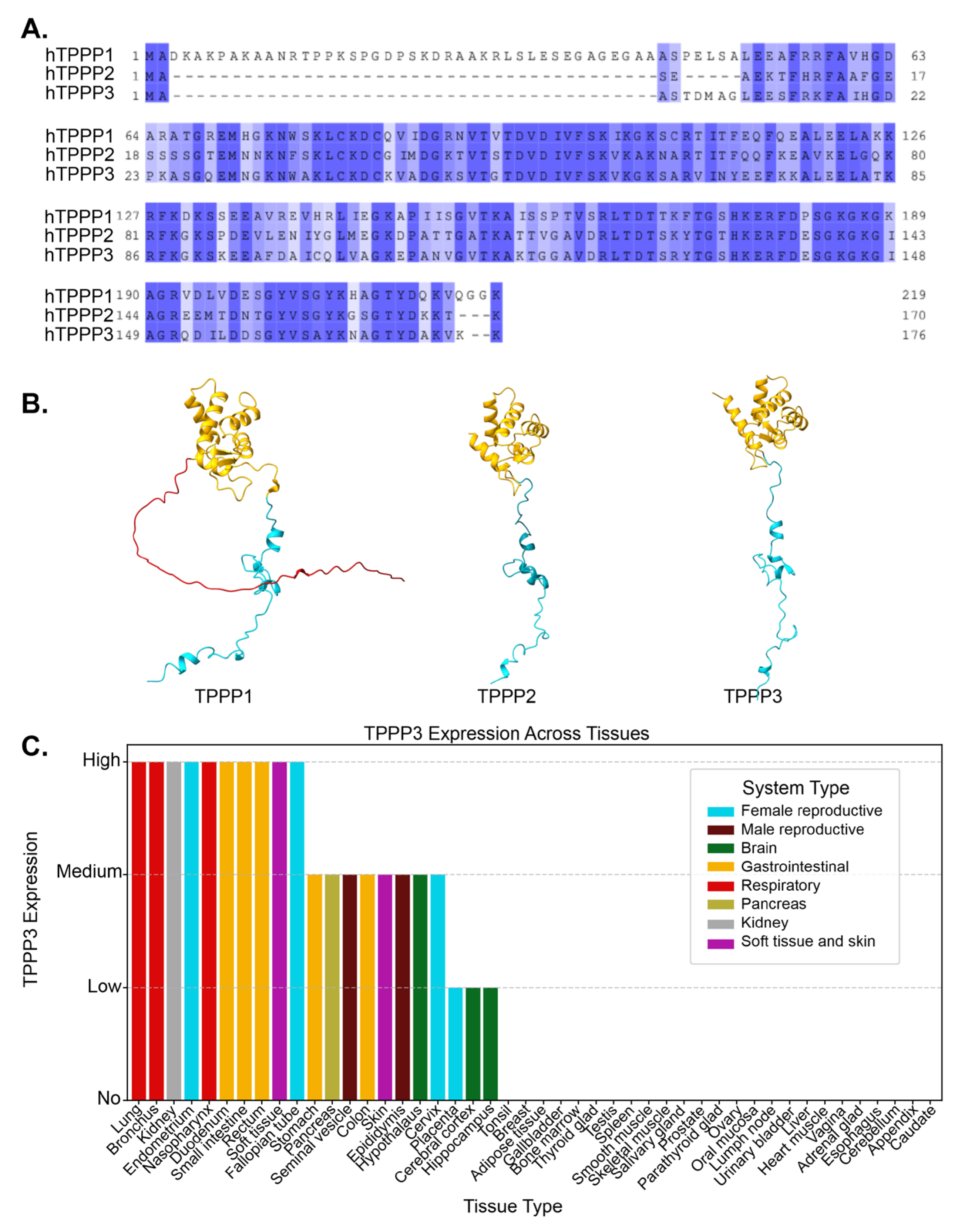

Tubulin polymerization promoting proteins (TPPPs) are a family of three microtubule associated proteins (MAPs) that were initially characterized as microtubule binding proteins [

1]. TPPP1, also referred to as TPPP/p25, was the first of these proteins to be isolated from bovine brain extracts and was originally thought of as brain specific protein as it was also found to localize in oligodendrocytes [

2,

3]. In oligodendrocytes, TPPP1 was able to nucleate microtubules from the golgi stacks [

4]. TPPP1 also bound to and promoted the assembly of microtubules [

5]. Two other members of the TPPP family, TPPP2 and TPPP3, were later identified due to their shared homology encoded by separate genes on distinct chromosomes [

1] (

Figure 1A). Functional analysis of the three proteins revealed that TPPP3 and TPPP1 bind, stabilize, and bundle microtubules, while TPPP2 is only able to weakly bind tubulin and did not have any bundling capacity[

1]. At the amino acid level, TPPP1 and TPPP3 share 81% sequence similarity excluding the N-terminal region as TPPP3 does not have the intrinsically disordered N-terminal region (

Figure 1B) [

6]. While TPPP2 and TPPP3 share a substantial 76% sequence similarity, differences in their sequences has resulted in reduced microtubule-binding affinity and inability to promote microtubule bundling [

1].

TPPP1 is the most extensively studied member of the TPPP family, with numerous in vitro [

5,

7,

8] and in vivo studies [

4,

9,

10], multiple knockout models in various organisms including

Drosophila and mice [

4,

9], and strong evidence linking it to the development of neurological disorders [

11,

12]. Given the TPPP3’s sequence similarity to TPPP1 and its shared ability to bundle microtubules, its normal biological functions have been sparsely studied. However, over the past nearly two decades, TPPP3 has been found to be implicated in a number of different diseases, with minimal microtubule association and acting on seemingly unrelated cellular pathways. TPPP3 is not expressed in most cell types, but are widely found in different tissues including the brain, gastrointestinal tract, airway, and reproductive tract (

www.proteinatlas.org) (

Figure 1C) [

13]. In this review, we have compiled findings related to TPPP3 and how its dysregulation is involved in various diseases.

Figure 1.

A. Alignment of protein sequences between TPPP1, TPPP2, and TPPP3. Residues are shaded by conservation. Dark blue shading indicates highly conserved residues. The degree of conservation decreases with lighter shades, and white indicating non-conserved regions. B. AlphaFold-predicted structures of TPPP1, TPPP2, and TPPP3, highlighting structural similarities among the three proteins. TPPP2 and TPPP3 lack the N-terminal region present in TPPP1. Red = N-terminus, Blue = C-terminus, Yellow = Ordered helical domain C. TPPP3 expression level in different tissues, taken from the proteinatlas.org. Each tissue type is composed of multiple different cell types.

Figure 1.

A. Alignment of protein sequences between TPPP1, TPPP2, and TPPP3. Residues are shaded by conservation. Dark blue shading indicates highly conserved residues. The degree of conservation decreases with lighter shades, and white indicating non-conserved regions. B. AlphaFold-predicted structures of TPPP1, TPPP2, and TPPP3, highlighting structural similarities among the three proteins. TPPP2 and TPPP3 lack the N-terminal region present in TPPP1. Red = N-terminus, Blue = C-terminus, Yellow = Ordered helical domain C. TPPP3 expression level in different tissues, taken from the proteinatlas.org. Each tissue type is composed of multiple different cell types.

2. Cancers

2.1. Cervical Cancer

TPPP3 was first implicated in cancer, shortly after its initial discovery. Zhou et al. sought to investigate endogenous functions of TPPP3 in the HeLa cervical cancer cell line. Using RNA interference (RNAi), they assessed the impact of TPPP3 knockdown on cell proliferation and apoptosis [

14]. Loss of TPPP3 expression resulted in an increase in cells in the G2-M phase of the cell cycle and a decrease of cells in S phase, indicating that more cells are getting stalled at the G2 checkpoint and less cells are entering the cell cycle. Loss of TPPP3 also leads to an increase in apoptotic cells. Cells with depleted TPPP3 were found to have a varying number of mitotic spindle poles, most with four or five. Multipolar cells can lead to aneuploidy which can ultimately lead to cell death [

15,

16]. They later expanded on this initial study in Lewis lung carcinoma, finding that TPPP3 depletion also inhibited tumor growth as well as metastasis [

17].

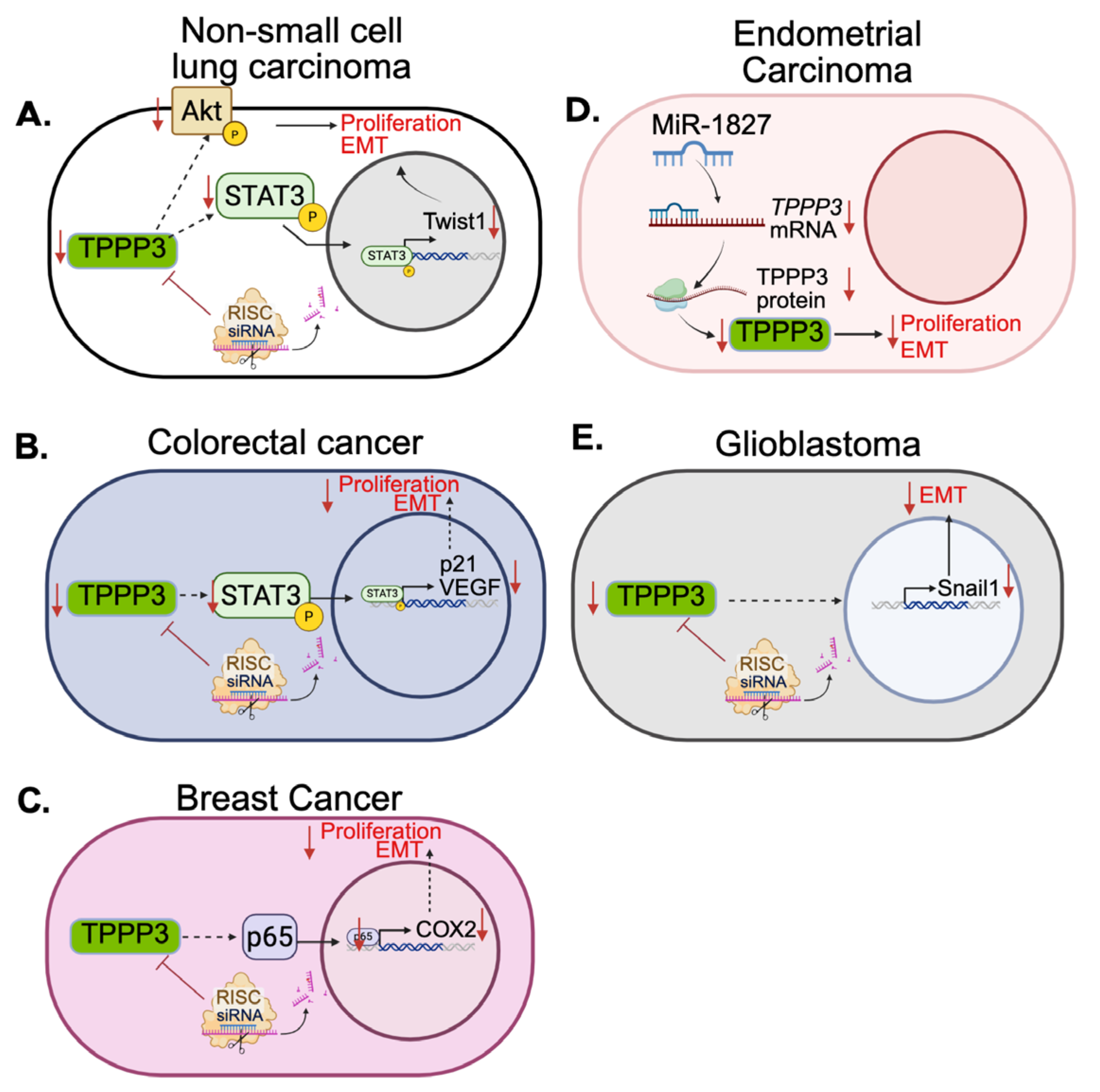

2.2. Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma

Furthermore, in 2016, the same group investigated the role of TPPP3 in non-small-cell lung carcinoma [

18]. They looked at patient survival data on non-small cell lung carbinoma showed that patients with high TPPP3 expression had worse overall survival. In vitro and in vivo experiments showed that loss of TPPP3 expression significantly decreased cell proliferation and tumor growth. In addition, TPPP3 knockdown also induced cell apoptosis and cell cycle arrest. Phosphorylation of AKT and STAT3, proteins involved in proliferation and apoptotic signaling, decreased after knockdown of TPPP3 [

19,

20,

21]. Consistent with this, in 2018 Li et al. also reported that TPPP3 promotes proliferation and invasion in non-small-cell lung carcinoma via the STAT3/TWIST1 pathway, providing further evidence to the potential role of TPPP3 in these cancers (

Figure 2A) [

22]. Overexpression of TPPP3 in non-small-cell lung carcinoma cell lines promoted cell proliferation as well as migration and invasion. There was an upregulation of transcription factors such as c-Myc and Twist1 as well as an increase in phosphorylation of STAT3. Another study from 2015 reported that cytoplasmic p27, also known as cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 1B (CDKN1B), can promote epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) and metastasis via the STAT3-TWIST1 pathway in human mammary epithelial cells, breast cancer, and bladder cancer [

23]. Phosphorylation of p27 is linked to PI3K/AKT and STAT3 activation whereby STAT3 induces Twist1, which promotes EMT. However, there is no current data linking p27 and AKT to TPPP3.

2.3. Colorectal Cancer

In 2017, it was reported that TPPP3 plays a similar role in colorectal cancer [

24]. In this study, analysis of 96 patient samples compared to patient-matched healthy tissue revealed that TPPP3 was significantly increased in colorectal cancer. Additionally, TPPP3 protein and mRNA levels were measured in five colorectal cancer cell lines compared to normal tissue and were significantly upregulated. High TPPP3 expression was also correlated with a worse overall survival in the 96 patients. The shRNA-mediated knockdown of TPPP3 decreased cell proliferation in vitro and also decreased migration and invasion in colorectal cancer cell lines, LOVO and SW620. In addition, phosphorylation of STAT3 decreased after knockdown and expression of anti-apoptotic protein, BCL-2, decreased while the expression of pro-apoptotic protein, Bax, increased, which aligns with their previous research in non-small-cell lung carcinoma. Cell cycle analysis revealed a decrease of S phase cells after TPPP3 knockdown accompanied by a downregulation of VEGF expression. When looking at the effect of TPPP3 knockdown on angiogenesis, they found that in HUVEC cells, loss of TPPP3 resulted in less tube structures when these cells were treated with colorectal cancer cell conditioned media. Protein analysis also revealed VEGF, a pro-angiogenesis factor, expression was decreased in the knockdown cell lines. The mechanism is illustrated in

Figure 2B.

2.4. Breast Cancer

In breast cancer, TPPP3 is also involved in cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis. However, it does so in the context of NF-κB/COX2 signaling [

25]. In breast cancer, Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) signaling is aberrantly activated and contributes to chemoresistance and metastasis [

26,

27]. Cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) is also upregulated in many cancers, including breast cancer, and its expression can induce NF-κB signaling [

28,

29]. Silencing of TPPP3 in breast cancer cell lines MCF-7 and T47D, decreased cell proliferation, invasion and migration [

25]. They also found that matrix metalloproteinases MMP-2 and MMP-9 were found to be significantly reduced after TPPP3 silencing. Both of these proteins are frequently upregulated in cancers and are associated with metastasis and tumor aggressiveness [

30]. NF-κB p65, also known as RelA, and COX2 expressions were also significantly downregulated after TPPP3 silencing, indicating that interfering with TPPP3 alters the malignant phenotype of breast cancer by downregulating the NF-κB/COX2 pathways (

Figure 2C). Additionally, TPPP3 has also been shown to be associated with breast cancer lung metastasis through Tppp3+ monocytes [

31]. Single cell RNA sequencing of breast cancer lung metastases in mice revealed a subpopulation of Tppp3+ monocytes that are highly associated with the metastases, likely through the promotion of angiogenesis [

31].

2.5. Endometrial Cancer

Similarly, in 2021, Shen et al. found that suppressing TPPP3 expression in endometrial cancer also inhibited proliferation, invasion and migration [

32]. When compared to normal endometrial tissue, endometrial cancer cell lines, as well as patient samples, exhibited elevated levels of TPPP3. ShRNA knockdown of TPPP3 attenuated proliferation, invasion, and migration potential, as seen in breast cancer [

33], colorectal cancer [

24], and non-small-cell lung carcinoma [

18,

22]. In addition to proliferation and metastasis, they also investigated how overexpression of microRNA 1827 (miR-1827) affects TPPP3 expression in endometrial cancer. MiRNAs have been studied for decades for their oncogenic/tumor suppressive role in cancer and potential therapeutic targets [

34,

35,

36]. Here, miR-1827 can target the 3’-UTR of TPPP3 mRNA leading to its degradation (

Figure 2D). Conversely, overexpression of TPPP3 in endometrial cancer cells with induced miR-1827 expression is able to maintain their proliferative, invasive, and migrative potential. Expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 are also significantly decreased after loss of TPPP3 expression via miR-1827 sequestration, suppressing tumorigenesis [

32]. Similar results were also seen in acute lymphoblastic leukemia where circular RNA circMUC16 targets miR-1182 which also targets the 3’ UTR of TPPP3 [

37]. Silencing of circMUC16 increased miR-1182 and decreased TPPP3 expression, exhibiting anti-tumor effects.

2.6. Glioblastoma

TPPP3 has also been associated with stemness and EMT in glioblastoma. In 2019, a study to characterize rare genes in glioblastoma found TPPP3 contributed to worse overall survival and was associated with increased invasiveness [

38]. It was later discovered that TPPP3 contributes to EMT via controlling the regulation of Snail family transcriptional repressor 1(SNAI1), a transcription factor that regulates the repression of E-cadherin, an adhesion molecule downregulated during EMT (

Figure 2E) [

39]. In glioblastoma, TPPP3 expression is elevated as compared to normal tissue, and its expression appears to increase with the grade of the tumor. Grade IV gliomas showed significantly higher levels of TPPP3 compared to grade I, and even more so to normal brain tissue. Glioblastoma cell lines that overexpressed TPPP3 showed decreased levels of epithelial marker E-Cadherin and increased levels of mesenchymal markers, N-cadherin and Vimentin. They also demonstrated an increased capacity for invasion and migration. Importantly, knockdown of TPPP3 lead to a decrease in Snail1 expression and overexpression of Snail1 in TPPP3-knockdown cells rescued its invasive and migrative potential. Snail1/2, ZEB1/2 and Twist1/2 are all core transcription factors that can activate the EMT program [

40]. Interestingly, in this study, Twist expression is not affected by TPPP3 knockdown like what was seen in non-small-cell lung carcinoma [

22]. TPPP3 appears to be able to regulate EMT in multiple different cancers, but through different mechanisms. Snail transcription factors are regulated by GSK3β while Twist transcription factors are regulated by MAPK [

40]. There is evidence that these transcription factors can regulate each other, i.e.

, Snail upregulating Twist [

41], however, it still remains unclear how TPPP3, a microtubule bundling protein, is involved in the expression of these transcription factors.

2.7. Liver Cancer

In 2024, Li et al. investigated how fluid shear stress, a mechanical force from blood circulation, impacts the metastatic potential of hepatocellular carcinoma [

42]. Fluid shear stress is one of the hurdles cancer cells have to overcome in order to successfully metastasize. They exposed hepatocellular carcinoma cell line HepG2 to fluidic shear stress for one, two and three hours in a microfluidics chamber and then analyzed changes in gene expression using RNA sequencing. A key finding was the significant upregulation of TPPP3 in cells subject to fluidic shear stress, with the three-hour exposure group showing an approximate 80-fold increase in TPPP3 mRNA. Further experiments revealed that overexpression of TPPP3 in HepG2 cells substantially increased their viability and metastatic potential in both in vitro and in vivo models [

42]. Conversely, knockdown of TPPP3 led to decreased colony formation and cell viability. Clinical data support these findings, demonstrating that high TPPP3 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma patients correlates with worse overall survival [

42].

2.8. Pancreatic Cancer

Thus far, we have discussed how TPPP3 has a pro-tumorigenic role in multiple different cancer types. However, in 2018, a research group sought to identify potential prognostic biomarkers in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [

43].They found that high expression of TPPP3 was found only in patients they deemed long survivors. Low TPPP3 was associated with significantly worse overall survival.

2.9. Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma

In 2020, Yang et al. carried out a pan cancer analysis of the role of TPPP3 in different cancer types [

44]. They found that in head and neck squamous carcinomas, specifically nasopharyngeal carcinoma, TPPP3 expression was significantly lower than that of normal tissue. Patient survival data also indicated that low-level of TPPP3 is associated with poor prognosis for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. In addition, they found that TPPP3 expression also correlated with levels of immune cell infiltration in the tumor. There was a negative correlation between CD8+ T cells and memory B cells, but a positive correlation to levels of dendritic cells. The authors hypothesized TPPP3 has a role in the regulation of immune cell infiltration in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. In 2022, Xiao et al. found that in oral cell squamous cell carcinoma, the most common type of head and neck cancer, higher TPPP3 expression was protective and was correlated with better overall survival and was also associated immune cell infiltration [

45]. This is further evidenced by a publication in 2024 that identified TPPP3, as well as Mucin4 (MUC4) and Chloride intracellular channel 6 (CLIC6) as three genes involved in the post-translational modification known as lactylation [

46]. Lactylation, the process of adding lactate groups to lysine residues, has been shown to modulate immune responses and metabolic adaptation as well as contribute to cell proliferation, and in nasopharyngeal carcinoma, may contribute to immune evasion and tumor aggressiveness [

47]. Similarly to what was found previously, all three of these genes, including TPPP3, were all downregulated in nasopharyngeal carcinoma and associated with worse survival.

TPPP3 appears to have differing roles in different cancers (Table 1). On one hand, it promotes tumorigenesis and metastasis in various cancers through similar pathways; on the other hand, it appears to play a protective role in others. This indicates that TPPP3 plays vastly different roles in different cell types and likely has other functions beyond microtubule polymerization and bundling. From modulation of STAT and AKT signaling, Snail and Twist signaling, NF-kB signaling, immune cell infiltration, and metastases promotion through TPPP3+ immune cells, further studies will need to be done to fully elucidate the role of TPPP3 across diverse biological and disease contexts.

| Cell type |

Cell line |

Role of TPPP3 |

Altered pathways |

Ref |

| Cervical cancer |

HeLa |

Tumorigenic

Proliferation

Mitosis |

|

[14] |

| Lewis lung carcinoma |

|

Tumorigenic

Proliferation

Mitosis

Suppression induces apoptosis |

|

[17] |

| Non-small cell lung cancer |

A549

H1229 |

Tumorigenic

Proliferation

Suppression induces apoptosis |

STAT3/AKT |

[18] |

| Non-small cell lung cancer |

95-C

SPC-A1

A549

H1229

Patient Samples (treatment naive) |

Tumorigenic

Proliferation

Invasion

Migration

Metastasis

Suppression induces apoptosis |

STAT3/Twist1 |

[22] |

| Colorectal cancer |

SW480

HT29

RKO

LOVO

SW620

HUVEC |

Tumorigenic

Proliferation

Invasion

Migration

Metastasis

Angiogenesis |

STAT3

VEGF/P21 |

[24] |

| Breast cancer |

MCF-7

T47D

Patient samples (treatment naïve) |

Tumorigenic

Proliferation

Invasion

Migration

|

NF-kB/COX2 |

[33] |

| Endometrial cancer |

Ishikawa

KLE

RL-95

AN3CA

Patient Samples (treatment naïve) |

Tumorigenic

Proliferation

Invasion

Migration

TPPP3 is targeted by mIR-1827 |

|

[32] |

| Glioblastoma |

U87ZMG

U118

A172

LN229

U251 |

Tumorigenic

Proliferation

Invasion

Migration

EMT

Suppression induces apoptosis |

SNAIL1 |

[39] |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma |

HepG2

SK-Hep-1 |

Tumorigenic

Metastasis |

|

[22] |

| Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma |

FFPE patient samples |

Protective

High expression associated with longer survival. |

|

[43] |

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma

|

Patient samples |

Protective

Lower TPPP3 expression in samples compared to normal tissue. Higher expression associated with better survival |

Immune cell infiltration into tumors |

[44] |

| Oral squamous cell carcinoma |

Patient samples |

Protective

Lower TPPP3 expression in samples compared to normal tissue. Higher expression associated with better survival |

Immune cell infiltration into tumors |

[45] |

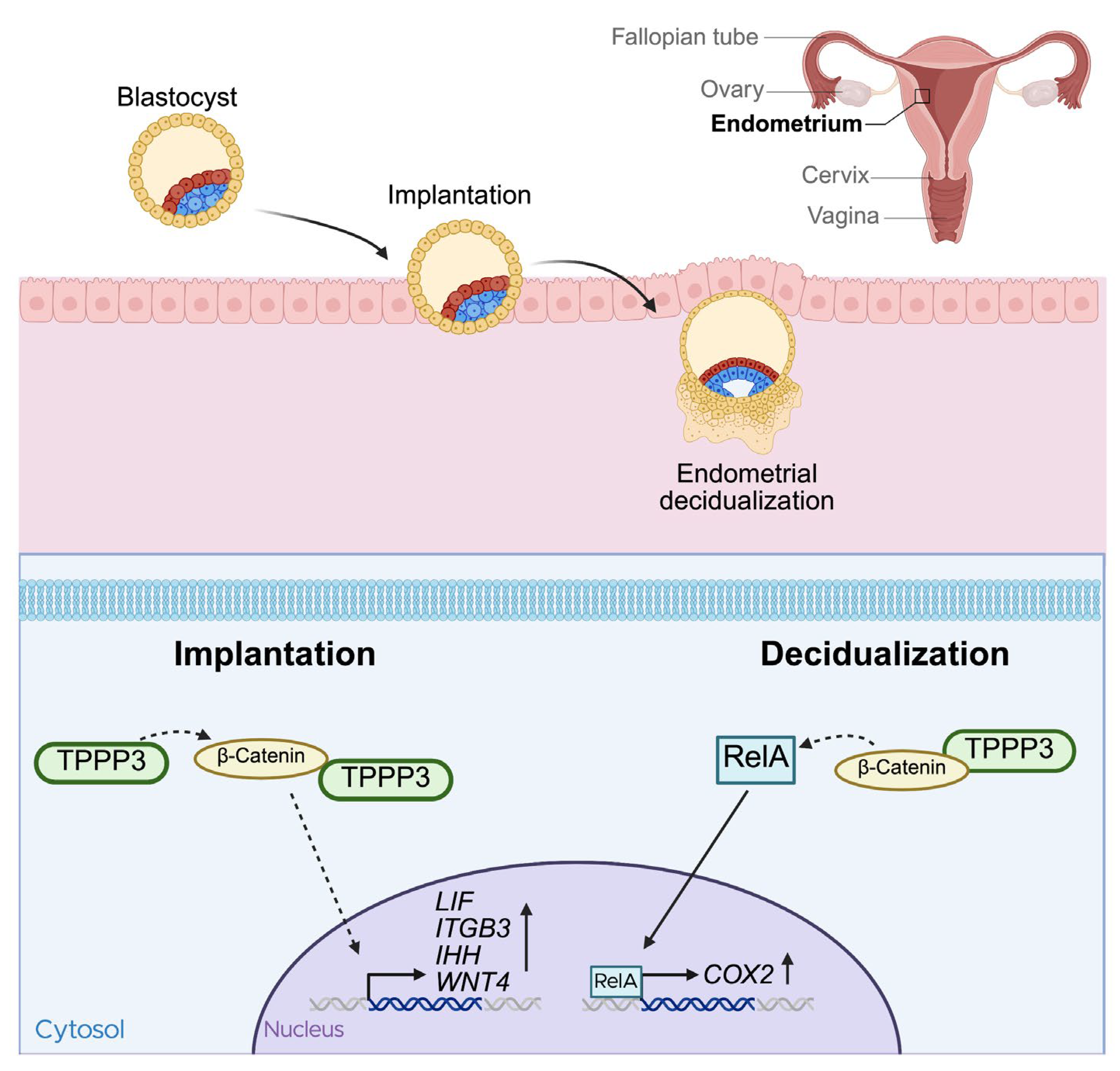

3. Reproduction

Two major phases of early pregnancy, blastocyst implantation and decidualization of the uterine lining, are crucial for establishing a viable pregnancy [

48]. These processes require an intricate network of signaling molecules and tight genetic control [

49,

50]. Following ovulation, the endometrium undergoes significant morphological changes, ultimately developing into the secretory endometrium, a stage at which it becomes receptive for embryo implantation [

51,

52]. Given how tightly regulated these processes are, disruption to any of these steps can lead to pregnancy failure [

53].

In 2014, Manohar et al. conducted a large proteomic analysis of uterine tissues from the early-secretory and mid-secretory phase from multiple different women with unexplained infertility, and compared the proteome to that of fertile women [

48]. TPPP3 expression was significantly decreased during the mid-secretory phase in infertile women. However, the exact role of TPPP3 during this phase was not elucidated during this study.

Subsequent research by the same group in 2018 investigated the role of TPPP3 during embryo implantation [

54]. TPPP3 protein expression steadily increased during the early-secretory phase, and into the secretory, or receptive phase. Crucially, knockdown of TPPP3 with siRNA significantly impacted the success of embryo implantation into the uterus. Known receptivity markers such as leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), Integrin-β3, Indian hedgehog signaling molecule (IHH), and Wnt4, which are typically upregulated during embryo implantation [

55,

56,

57,

58], were all found to be decreased after TPPP3 knockdown, further supporting the importance of TPPP3 on implantation. The study also revealed that TPPP3 regulates β-catenin signaling and is a direct binding partner of β-catenin. Wnt/ β-catenin signaling is a crucial pathway during early pregnancy[

59,

60] [

Figure 3].

Another important step of early pregnancy is decidualization. Decidualization is the transformation of endometrial stromal fibroblasts into secretory cells, that provide nutrients and support for the implanted embryo [

61]. TPPP3 is also highly important during this process [

25]. Shukla et al. performed in vitro experiments using human embryonic stem cells and in vivo studies in BALB/c mice. TPPP3 was highly expressed during decidualization, and siRNA-mediated knockdown significantly decreased endometrial decidualization. Consistent with their previous findings, TPPP3 co-localized with β-catenin, and TPPP3 knockdown reduced both their localization and expression of β-catenin. Moreover, TPPP3 knockdown also decreased the nuclear localization and activation of NF-κB subunit p65, also known as RelA, in decidual cells. Given that COX-2 deficiency in mice has been shown to result in decidualization failure [

62] and that the COX-2 promoter region contains multiple RelA binding sites [

63,

64], the observation that COX-2 expression was significantly decreased in TPPP3 siRNA-transfected human embryonic stem cells further highlights the role of TPPP3. In summary, the loss of TPPP3 expression during decidualization was found to result in decreased β-catenin signaling, a pathway capable of modulating inflammatory signaling via its components interacting with RelA. This reduction in β-catenin signaling led to less nuclear localization of RelA, subsequently decreasing the transcription of one of its targets, COX-2, which is essential for successful decidualization (

Figure 3).

4. Musculoskeletal System

Interestingly, TPPP3 is also associated with the musculoskeletal system, where it serves as a marker for specific tendon stem cell populations. In 2009, Steverovsky et al. identified tendon-specific genes during various stages of embryonic development [

65]. They found that TPPP3 was expressed in tissues surrounding the tendon, including the epitenon, paratenon, tendon sheath, and synovial joint cavitation sites. It was not until years later that TPPP3 was recognized as a marker of tendon stem cell populations [

66]. These Tppp3

+ populations that support tendon wound healing also coexpressed platelet-derived growth factor alpha (Pdgfra), a protein involved in tendon growth and remodeling [

67]. Interestingly, Tppp3

+Pdgfra

+ tenocytes were shown to support tendon wound healing, whereas Tppp3

+Pdgfra

− tenocytes were associated with fibrotic scarring in regeneration [

66].

Similarly, Yea et al. also investigated wound healing after trauma, specifically heterotopic ossification, or the deposition of aberrant bone in muscles tendons or ligaments[

68]. Heterotopic ossification is a common occurrence in traumatic conditions such as arthroplasty and fractures [

69]. They found that Tppp3

+ tendon sheath progenitor cells expanded rapidly after an Achilles injury in mice [

68]. Single-cell RNA sequencing of tendon-associated traumatic heterotopic ossification found Tppp3 may be an early progenitor marker for either tendon or bone producing cells. They investigated Tppp3

+Pdgfr

+ and Tppp3

+Pdgfr

- progenitor cell populations, and while the former was associated with trauma healing and the later associated with fibrosis, both of these populations gave rise to heterotopic ossification-associated cartilage [

68]. Thus far these studies were done in mouse models; however, a similar phenotype of TPPP3

+ chondrogenic cells was later described in human tissues as well [

70].

Moreover, another study investigated underlying mechanisms of tendon regeneration in neonatal mice [

71,

72]. They highlighted the tendon wound healing capabilities of young children are much better than that of adults and sought to identify the mechanism underlying this change [

71,

73]. Using neonatal mice, they revealed that Tppp3-expressing paratenon sheath cells are a key population of tendon-regenerating and PI3K-Akt signaling drives regeneration of injured tendons in neonatal mice. The PI3K-Akt pathway is associated with proliferation [

20,

74] and is more upregulated in the injury areas of neonatal mice as a opposed to adult mice [

72]. Additionally, suppression of PI3K-Akt signaling resulted in weakened and thinned tendons after regeneration, highlighting the role of PI3K-Akt signaling in these Tppp3

+ paratenon sheath cells.

Similarly, another group investigated underlying mechanisms of Dupuytren’s contracture, a fibrotic disease affecting flexion in affected fingers, impairing hand function [

75]. At the site of the contracture, there is an infiltration of Tppp3

+ cells. These cells had increased Wnt/ β-catenin signaling and activation of this pathway resulted in M2 macrophage infiltration via the Cxcl14 chemokine. This resulted in fibrosis. The authors reported that their findings suggest that the Cxcl14 stromal cell and macrophage interaction is a promising target for the treatment of fibrosis mediated by Wnt/ β-catenin signaling. Given the previous studies around the association of TPPP3 with β-catenin and downstream pathways, this interaction may also be a viable therapeutic target [

25,

54].

5. Endothelial Dysfunction

Palmitic acid is one of the most common free fatty acids in the body[

76] and is known to induce lipotoxicity, a primary cause of endothelial dysfunction [

77]. Using human umbilical vein endothelial cells, Liu et al. found that in the presence of palmitic acid, TPPP3 expression significantly increased [

78]. Additionally, reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation was significantly increased and lead to cell death and decreased tube formation. This was mediated by TPPP3 interacting with, and stabilizing voltage-dependent anion channel 1 (VDAC1). VDAC1 is the most abundant anion channel in the mitochondrial membrane and is responsible for the transport of metabolites in and out of the mitochondria, including ROS [

79].

Interestingly, they also found that TPPP3 promotes ROS formation and through mass spectrometry, found it has an interaction with VDAC1. While this leads to damage and apoptosis in endothelial cells, it is conceivable that this could also be cancer promoting as adequate ROS levels are important for cancer proliferation, differentiation and metastasis [

80]. However, similar to the findings in endothelial cells, high levels of ROS ultimately lead to cellular damage and cell death.

6. Neurodegenerative Diseases

TPPP3 has also been explored in the context of neuron regeneration and neurodegenerative diseases. A study in zebrafish found that

tppp3 is a target of miR-133b in the regulation of axonal regeneration [

81]. Further studies identified

Tppp3 as a marker of retinal ganglion cells and that

Tppp3 overexpression promotes retinal ganglion cell regeneration and neurite outgrowth [

82]. Despite its name, tubulin polymerization promoting protein, there is surprisingly little research associating TPPP3 with tubulin or microtubules. However, given that TPPP3 was originally identified as a neuron specific protein, similar to TPPP1 [

83], the role of TPPP3 in neuron regeneration is potentially due to its abilities to bundle and bind to microtubules, since microtubule bundling is extremely important for neuron structure [

84]. However, this has not been experimentally validated.

TPPP3 has also been investigated in the context of neurodegenerative disease, specifically in the context of alpha-synucleinopathies [

85]. Alpha-synucleinopathies are a group of neurodegenerative disease characterized by aggregates of hyperphosphorylated α-synuclein that lead to neuron death [

86]. Some of these diseases include Parkinson’s disease, multiple system atrophy, and diffuse Lewy body disease. In 2004, TPPP1 was identified as a common marker for alpha-synucleinopathies [

11]. They found that TPPP1 and α-synuclein were co-enriched and co-localized in patients with Parkinson’s disease and multiple system atrophy. However, they also found that TPPP3 will dimerize with itself and TPPP1 but had little binding to α-synuclein and therefore did little in the promotion of α-synuclein aggregation, like TPPP1. Although the strong affinity to TPPP1 resulted in the destruction of the TPPP1- α-synuclein complexes that promote these diseases, TPPP3 may have an inhibitory effect in alpha-synucleinopathies.

Together these studies indicate that TPPP3 may plays significant role in neuron biology and neurodegenerative disease and further research is needed to further characterize its roles in these cell types.

7. Conclusions

Several studies have supported the role of TPPP3 in promoting proliferation and metastasis. However, TPPP3 may operate through distinct, cancer-type-specific pathways. TPPP3 modulates STAT3/Twist1 signaling in non-small-cell lung carcinoma and colorectal cancer promoting proliferation, migration, and invasion [

18,

22,

24]. In breast cancer, loss of TPPP3 is also associated with decreased proliferation, migration and invasion. However, it is operating on the NF-kB/COX2 axis, a commonly altered pathway in breast cancer [

33]. Loss of TPPP3 in endometrial cancer also resulted in decreased proliferation, migration, and invasion; however, a mechanism was not proposed. However, they did identify TPPP3 as a target of microRNA-1827 which has the potential to be leveraged as a therapeutic option in cancers with aberrant TPPP3 expression [

32,

87]. In glioblastoma, TPPP3 affects the Snail pathway, a common marker of EMT [

39]. Snail and Twist are both promoters of EMT and can even modulate each other’s expression [

40]. However, even though TPPP3 has shown to be involved in both pathways, Twist1 in non-small-cell lung carcinoma and Snail1 in glioblastoma, there is no evidence that the expression of the other is modulated in these cancers. In hepatocellular carcinoma, TPPP3 is involved in a more structural context. TPPP3 allowed hepatocellular carcinoma cells to withstand fluid sheer stress better than TPPP3 knockdown cells, making them more viable during metastasis [

42]. Further studies are needed to elucidate the role of TPPP3 in enabling cells to withstand fluid shear stress.

Conversely, there are certain cancers where TPPP3 is associated with better survival. There are multiple head and neck cancers where tumor samples had lower TPPP3 expression than the surrounding area and was correlated with worse survival [

45,

46]. Interestingly, elevated levels of TPPP3 expression were associated with certain immune cell infiltration into the tumor. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma tumors also showed worse overall survival with lower TPPP3 expression [

43]. Further studies will be needed to understand the protective effects of TPPP3 in these tumors.

Even with all this research assessing the impact of TPPP3 on these different cancers, the question remains - what does TPPP3 do? It is involved in multiple pathways, but the actual role it plays in proliferation and metastasis in many of these cancers remains unknown. It can bundle microtubules, but it likely has many other binding partners that facilitate its role in tumorigenesis and metastasis.

However, in early pregnancy, it does seem to have a direct role in the β-catenin/NF-kB/Cox2 pathway [

25,

54]. TPPP3 is able to be pulled down with β-catenin, indicating that it is a binding partner, or at the very least binds to a complex that β-catenin binds to. Loss of TPPP3 decreases β-catenin signaling and results in embryo implantation failure and endometrial decidualization failure. This could potentially inform research about the role of TPPP3 in cancer, given it is already associated with NF-kB/COX2 pathway in breast cancer [

33]. Investigating how it interacts with the β-catenin pathway in cancer may potentially lead to an understanding of its role in cancer proliferation and invasion.

Consistent with its seemingly broad functions, it is also a marker of certain stem cell populations, specifically, Tppp3+ tendon stem cells are associated with wound healing/regeneration and fibrosis [

66,

68,

72]. The exact role of Tppp3 is still unknown. TPPP3 is not ubiquitously expressed throughout the body, so it must have unique functions as to be expressed in a specific tendon stem cell population.

We can further assess its functions through its physical interaction with VDAC1. TPPP3 can stabilize this channel to allow for the release of ROS in the presence of palmitic acid [

78]. This is very different function from its prior contexts in cancer, early pregnancy, and tendon injury. However, it provides further insight into the binding partners of TPPP3, furthering our understanding of it in normal physiology.

Beyond these broad categories, there have been a number of sequencing studies that has found significant changes in TPPP3 gene expression [

88,

89,

90,

91,

92,

93,

94,

95] (Table 2). These large datasets are extremely valuable as they allow for future hypothesis generation and inform the direction of new studies.

| Disease/Context |

Data type |

Regulation |

Ref |

| Diabetic Retinopathy |

Proteome-wide associate studies |

|

[88] |

| Epilepsy |

RNA-seq

iTRAQ proteomics |

Down-regulated in patients with epilepsy |

[89] |

| Lung cancer and COPD |

Proteomics |

Up-regulated in COPD, lung cancer, and COPD and lung cancer groups |

[90] |

| High blood pressure |

microarray |

Up-regulated in monocytes associated with increased blood pressure. |

[91] |

| Ulcerative colitis |

RNA-seq |

Down-regulated in ulcerative colitis group compared to control |

[92] |

| Non-ulcerative bladder pain syndrome |

RNA-seq |

Biomarker for non-ulcerative bladder pain syndrome |

[93] |

| Sarcopenia |

RNA-seq |

Up-regulated in patients with sarcopenia |

[94] |

| Alveolar regeneration |

RNA-seq |

Upregulated during AT2 cell differentiation. TPPP3 was reduced in Tert-\- mice. |

[95] |

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.W.L and S.H.; literature search, J.W.L and S.H; manuscript draft, J.W.L; manuscript edit, S.H., generation of figures, J.W.L and S.H; funding acquisition, J.W.L and S.H, supervision, S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Author Contributions

This research was funded by Michigan State University Outstanding Scholar Fellowship (J.W.L.), and Michigan State University Start-Up Fund (S.H.), and Spectrum Health (Corewell Health) – MSU Alliance Corp (S.H.).

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used BioRender to generate illustrations. We would like to thank Dr. Krishna Kishore Mahalingan for his expert opinion.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Vincze O, Tökési N, Oláh J, Hlavanda E, Zotter Á, Horváth I, et al. Tubulin Polymerization Promoting Proteins (TPPPs): Members of a New Family with Distinct Structures and Functions. Biochemistry. 2006 Nov 1;45(46):13818–26. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi M, Tomizawa K, Ishiguro K, Sato K, Omori A, Sato S, et al. A novel brain-specific 25 kDa protein (p25) is phosphorylated by a Ser/Thr-Pro kinase (TPK II) from tau protein kinase fractions. FEBS Letters. 1991;289(1):37–43. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi M, Tomizawa K, Fujita SC, Sato K, Uchida T, Imahori K. A Brain-Specific Protein p25 Is Localized and Associated with Oligodendrocytes, Neuropil, and Fiber-Like Structures of the CA3 Hippocampal Region in the Rat Brain. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1993;60(1):228–35. [CrossRef]

- Fu M meng, McAlear TS, Nguyen H, Oses-Prieto JA, Valenzuela A, Shi RD, et al. The Golgi Outpost Protein TPPP Nucleates Microtubules and is Critical for Myelination. Cell. 2019 Sept 19;179(1):132-146.e14. [CrossRef]

- Hlavanda E, Kovács J, Oláh J, Orosz F, Medzihradszky KF, Ovádi J. Brain-Specific p25 Protein Binds to Tubulin and Microtubules and Induces Aberrant Microtubule Assemblies at Substoichiometric Concentrations. Biochemistry. 2002 July 1;41(27):8657–64. [CrossRef]

- Jumper J, Evans R, Pritzel A, Green T, Figurnov M, Ronneberger O, et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 2021 Aug;596(7873):583–9. [CrossRef]

- Lehotzky A, Tirián L, Tökési N, Lénárt P, Szabó B, Kovács J, et al. Dynamic targeting of microtubules by TPPP/p25 affects cell survival. Journal of Cell Science. 2004 Dec 1;117(25):6249–59. [CrossRef]

- Tőkési N, Lehotzky A, Horváth I, Szabó B, Oláh J, Lau P, et al. TPPP/p25 Promotes Tubulin Acetylation by Inhibiting Histone Deacetylase 6. J Biol Chem. 2010 June 4;285(23):17896–906. [CrossRef]

- Mino RE, Rogers SL, Risinger AL, Rohena C, Banerjee S, Bhat MA. Drosophila Ringmaker regulates microtubule stabilization and axonal extension during embryonic development. J Cell Sci. 2016 Sept 1;129(17):3282–94. [CrossRef]

- Endres T, Duesler L, Corey DA, Kelley TJ. In vivo impact of tubulin polymerization promoting protein (Tppp) knockout to the airway inflammatory response. Sci Rep. 2023 July 28;13:12272. [CrossRef]

- Kovács GG, László L, Kovács J, Jensen PH, Lindersson E, Botond G, et al. Natively unfolded tubulin polymerization promoting protein TPPP/p25 is a common marker of alpha-synucleinopathies. Neurobiology of Disease. 2004 Nov 1;17(2):155–62. [CrossRef]

- Lindersson E, Lundvig D, Petersen C, Madsen P, Nyengaard JR, Højrup P, et al. p25α Stimulates α-Synuclein Aggregation and Is Co-localized with Aggregated α-Synuclein in α-Synucleinopathies*. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005 Feb 18;280(7):5703–15.

- Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, et al. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science. 2015 Jan 23;347(6220):1260419. [CrossRef]

- Zhou W, Wang X, Li L, Feng X, Yang Z, Zhang W, et al. Depletion of tubulin polymerization promoting protein family member 3 suppresses HeLa cell proliferation. Mol Cell Biochem. 2010 Jan 1;333(1):91–8. [CrossRef]

- Fukasawa, K. Centrosome amplification, chromosome instability and cancer development. Cancer Letters. 2005 Dec 8;230(1):6–19. [CrossRef]

- Nigg, EA. Origins and consequences of centrosome aberrations in human cancers. International Journal of Cancer. 2006;119(12):2717–23. [CrossRef]

- Zhou W, Li J, Wang X, Hu R. Stable knockdown of TPPP3 by RNA interference in Lewis lung carcinoma cell inhibits tumor growth and metastasis. Mol Cell Biochem. 2010 Oct 1;343(1):231–8. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Xu Y, Ye K, Wu N, Li J, Liu N, et al. Knockdown of Tubulin Polymerization Promoting Protein Family Member 3 Suppresses Proliferation and Induces Apoptosis in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Cancer. 2016 June 18;7(10):1189–96. [CrossRef]

- Xu N, Lao Y, Zhang Y, Gillespie DA. Akt: A Double-Edged Sword in Cell Proliferation and Genome Stability. J Oncol. 2012;2012:951724. [CrossRef]

- Zhou H, Li XM, Meinkoth J, Pittman RN. Akt Regulates Cell Survival and Apoptosis at a Postmitochondrial Level. J Cell Biol. 2000 Oct 30;151(3):483–94. [CrossRef]

- Tolomeo M, Cascio A. The Multifaced Role of STAT3 in Cancer and Its Implication for Anticancer Therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Jan 9;22(2):603. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Bai M, Xu Y, Zhao W, Liu N, Yu J. TPPP3 Promotes Cell Proliferation, Invasion and Tumor Metastasis via STAT3/ Twist1 Pathway in Non-Small-Cell Lung Carcinoma. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry. 2018 Nov 7;50(5):2004–16. [CrossRef]

- Zhao D, Besser AH, Wander SA, Sun J, Zhou W, Wang B, et al. Cytoplasmic p27 promotes epithelial–mesenchymal transition and tumor metastasis via STAT3-mediated Twist1 upregulation. Oncogene. 2015 Oct;34(43):5447–59. [CrossRef]

- Ye K, Li Y, Zhao W, Wu N, Liu N, Li R, et al. Knockdown of Tubulin Polymerization Promoting Protein Family Member 3 inhibits cell proliferation and invasion in human colorectal cancer. J Cancer. 2017;8(10):1750–8. [CrossRef]

- Shukla V, Kaushal JB, Sankhwar P, Manohar M, Dwivedi A. Inhibition of TPPP3 attenuates β-catenin/NF-κB/COX-2 signaling in endometrial stromal cells and impairs decidualization. 2019 Mar 1 [cited 2024 Dec 19]; Available from: https://joe.bioscientifica.com/view/journals/joe/240/3/JOE-18-0459.xml. [CrossRef]

- Dai XL, Zhou SL, Qiu J, Liu YF, Hua H. Correlated expression of Fas, NF-kappaB, and VEGF-C in infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the breast. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2012;33(6):633–9.

- Huber MA, Azoitei N, Baumann B, Grünert S, Sommer A, Pehamberger H, et al. NF-kappaB is essential for epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis in a model of breast cancer progression. J Clin Invest. 2004 Aug;114(4):569–81. [CrossRef]

- Xu H, Lin F, Wang Z, Yang L, Meng J, Ou Z, et al. CXCR2 promotes breast cancer metastasis and chemoresistance via suppression of AKT1 and activation of COX2. Cancer Lett. 2018 Jan 1;412:69–80. [CrossRef]

- Zatelli MC, Molè D, Tagliati F, Minoia M, Ambrosio MR, degli Uberti E. Cyclo-oxygenase 2 modulates chemoresistance in breast cancer cells involving NF-kappaB. Cell Oncol. 2009;31(6):457–65. [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo M, Eckhardt SG. Development of matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors in cancer therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001 Feb 7;93(3):178–93. [CrossRef]

- Huang Z, Bu D, Yang N, Huang W, Zhang L, Li X, et al. Integrated analyses of single-cell transcriptomics identify metastasis-associated myeloid subpopulations in breast cancer lung metastasis. Front Immunol. 2023 July 7;14:1180402. [CrossRef]

- Shen A, Tong X, Li H, Chu L, Jin X, Ma H, et al. TPPP3 inhibits the proliferation, invasion and migration of endometrial carcinoma targeted with miR-1827. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology. 2021;48(6):890–901. [CrossRef]

- Ren Q, Hou Y, Li X, Fan X. Silence of TPPP3 suppresses cell proliferation, invasion and migration via inactivating NF-κB/COX2 signal pathway in breast cancer cell. Cell Biochemistry and Function. 2020;38(6):773–81. [CrossRef]

- Calin GA, Dumitru CD, Shimizu M, Bichi R, Zupo S, Noch E, et al. Frequent deletions and down-regulation of micro- RNA genes miR15 and miR16 at 13q14 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002 Nov 26;99(24):15524–9. [CrossRef]

- Halim A, Kim B, Kenyon E, Moore A. miR-10b as a Clinical Marker and a Therapeutic Target for Metastatic Breast Cancer. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2025 June 1;24:15330338251339256. [CrossRef]

- Ho CS, Noor SM, Nagoor NH. MiR-378 and MiR-1827 Regulate Tumor Invasion, Migration and Angiogenesis in Human Lung Adenocarcinoma by Targeting RBX1 and CRKL, Respectively. J Cancer. 2018;9(2):331–45. [CrossRef]

- Tang J, Sun J, Liao J, Pu C, Yuan S, Li C, et al. Down-regulation of circMUC16 inhibited the progression of ALL via interaction with miR-1182 and TPPP3. Ann Hematol. 2025 June 1;104(6):3389–401. [CrossRef]

- Pang L, Hu J, Li F, Yuan H, Yan M, Liao G, et al. Discovering Rare Genes Contributing to Cancer Stemness and Invasive Potential by GBM Single-Cell Transcriptional Analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2019 Dec 16;11(12):2025. [CrossRef]

- Xu X, Hou Y, Long N, Jiang L, Yan Z, Xu Y, et al. TPPP3 promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition via Snail1 in glioblastoma. Sci Rep. 2023 Oct 20;13(1):17960. [CrossRef]

- Lamouille S, Xu J, Derynck R. Molecular mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014 Mar;15(3):178–96.

- Peinado H, Olmeda D, Cano A. Snail, Zeb and bHLH factors in tumour progression: an alliance against the epithelial phenotype? Nat Rev Cancer. 2007 June;7(6):415–28. [CrossRef]

- Li W, Guo Z, Zhou Z, Zhou Z, He H, Sun J, et al. Distinguishing high-metastasis-potential circulating tumor cells through fluidic shear stress in a bloodstream-like microfluidic circulatory system. Oncogene. 2024 July;43(30):2295–306. [CrossRef]

- Hu D, Ansari D, Pawłowski K, Zhou Q, Sasor A, Welinder C, et al. Proteomic analyses identify prognostic biomarkers for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget. 2018 Jan 3;9(11):9789–807. [CrossRef]

- Yang Z, Li X, Li J, Su Q, Qiu Y, Zhang Z, et al. TPPP3 Associated with Prognosis and Immune Infiltrates in Head and Neck Squamous Carcinoma. Biomed Res Int. 2020 Oct 6;2020:3962146. [CrossRef]

- Xiao T, Lin F, Zhou J, Tang Z. The expression and role of tubulin polymerization-promoting protein 3 in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Archives of Oral Biology. 2022 Nov 1;143:105519. [CrossRef]

- Liu C, Ni C, Li C, Tian H, Jian W, Zhong Y, et al. Lactate-related gene signatures as prognostic predictors and comprehensive analysis of immune profiles in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Transl Med. 2024 Dec 20;22(1):1116. [CrossRef]

- He Y, Song T, Ning J, Wang Z, Yin Z, Jiang P, et al. Lactylation in cancer: Mechanisms in tumour biology and therapeutic potentials. Clin Transl Med. 2024 Oct 25;14(11):e70070. [CrossRef]

- Manohar M, Khan H, Sirohi VK, Das V, Agarwal A, Pandey A, et al. Alteration in Endometrial Proteins during Early- and Mid-Secretory Phases of the Cycle in Women with Unexplained Infertility. PLoS One. 2014 Nov 18;9(11):e111687. [CrossRef]

- Singh M, Chaudhry P, Asselin E. Bridging endometrial receptivity and implantation: network of hormones, cytokines, and growth factors. 2011 July 1 [cited 2025 Sept 16]; Available from: https://joe.bioscientifica.com/view/journals/joe/210/1/5.xml. [CrossRef]

- Cyclic Decidualization of the Human Endometrium in Reproductive Health and Failure | Endocrine Reviews | Oxford Academic [Internet]. [cited 2025 July 8]. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/edrv/article/35/6/851/2354669.

- Psychoyos, A. Hormonal Control of Ovoimplantation*. In: Harris RS, Diczfalusy E, Munson PL, Glover J, Thimann KV, Wool IG, et al., editors. Vitamins & Hormones [Internet]. Academic Press; 1974 [cited 2025 July 8]. p. 201–56. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0083672908609991.

- Ferenczy A, Mutter GL. The Endometrial Cycle | GLOWM [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2025 July 8]. Available from: http://www.glowm.com/section-view/heading/The Endometrial Cycle/item/292.

- Cakmak H, Taylor HS. Implantation failure: molecular mechanisms and clinical treatment. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17(2):242–53. [CrossRef]

- Shukla V, Popli P, Kaushal JB, Gupta K, Dwivedi A. Uterine TPPP3 plays important role in embryo implantation via modulation of β-catenin†. Biology of Reproduction. 2018 Nov 1;99(5):982–99. [CrossRef]

- Aghajanova, L. Leukemia inhibitory factor and human embryo implantation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004 Dec;1034:176–83. [CrossRef]

- Lee K, Jeong J, Kwak I, Yu CT, Lanske B, Soegiarto DW, et al. Indian hedgehog is a major mediator of progesterone signaling in the mouse uterus. Nat Genet. 2006 Oct;38(10):1204–9. [CrossRef]

- Peng J, Monsivais D, You R, Zhong H, Pangas SA, Matzuk MM. Uterine activin receptor-like kinase 5 is crucial for blastocyst implantation and placental development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015 Sept 8;112(36):E5098–107. [CrossRef]

- Tei C, Maruyama T, Kuji N, Miyazaki T, Mikami M, Yoshimura Y. Reduced Expression of αvβ3 Integrin in the Endometrium of Unexplained Infertility Patients with Recurrent IVF-ET Failures: Improvement by Danazol Treatment. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2003 Jan;20(1):13–20. [CrossRef]

- Tepekoy F, Akkoyunlu G, Demir R. The role of Wnt signaling members in the uterus and embryo during pre-implantation and implantation. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2015 Mar;32(3):337–46. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed OA, Jonnaert M, Labelle-Dumais C, Kuroda K, Clarke HJ, Dufort D. Uterine Wnt/β-catenin signaling is required for implantation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2005 June 14;102(24):8579–84. [CrossRef]

- Gellersen B, Brosens JJ. Cyclic decidualization of the human endometrium in reproductive health and failure. Endocr Rev. 2014 Dec;35(6):851–905. [CrossRef]

- Lim H, Paria BC, Das SK, Dinchuk JE, Langenbach R, Trzaskos JM, et al. Multiple Female Reproductive Failures in Cyclooxygenase 2–Deficient Mice. Cell. 1997 Oct 17;91(2):197–208. [CrossRef]

- Pedram A, Razandi M, Aitkenhead M, Hughes CCW, Levin ER. Integration of the Non-genomic and Genomic Actions of Estrogen: MEMBRANE-INITIATED SIGNALING BY STEROID TO TRANSCRIPTION AND CELL BIOLOGY*. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002 Dec 27;277(52):50768–75.

- Schmedtje JF, Ji YS, Liu WL, DuBois RN, Runge MS. Hypoxia Induces Cyclooxygenase-2 via the NF-κB p65 Transcription Factor in Human Vascular Endothelial Cells*. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997 Jan 3;272(1):601–8. [CrossRef]

- Staverosky JA, Pryce BA, Watson SS, Schweitzer R. Tubulin polymerization-promoting protein family member 3, Tppp3, is a specific marker of the differentiating tendon sheath and synovial joints. Developmental Dynamics. 2009;238(3):685–92. [CrossRef]

- Harvey T, Flamenco S, Fan CM. A Tppp3+Pdgfra+ tendon stem cell population contributes to regeneration and reveals a shared role for PDGF signalling in regeneration and fibrosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2019 Dec;21(12):1490–503. [CrossRef]

- Sugg KB, Markworth JF, Disser NP, Rizzi AM, Talarek JR, Sarver DC, et al. Postnatal tendon growth and remodeling require platelet-derived growth factor receptor signaling. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2018 Apr 1;314(4):C389–403. [CrossRef]

- Yea JH, Gomez-Salazar M, Onggo S, Li Z, Thottappillil N, Cherief M, et al. Tppp3+ synovial/tendon sheath progenitor cells contribute to heterotopic bone after trauma. Bone Res. 2023 July 21;11(1):1–12. [CrossRef]

- Meyers C, Lisiecki J, Miller S, Levin A, Fayad L, Ding C, et al. Heterotopic Ossification: A Comprehensive Review. JBMR Plus. 2019 Feb 27;3(4):e10172. [CrossRef]

- Kendal AR, Layton T, Al-Mossawi H, Appleton L, Dakin S, Brown R, et al. Multi-omic single cell analysis resolves novel stromal cell populations in healthy and diseased human tendon. Sci Rep. 2020 Sept 3;10:13939. [CrossRef]

- Cooper L, Khor W, Burr N, Sivakumar B. Flexor tendon repairs in children: Outcomes from a specialist tertiary centre. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery. 2015 May 1;68(5):717–23. [CrossRef]

- Goto A, Komura S, Kato K, Maki R, Hirakawa A, Aoki H, et al. PI3K-Akt signalling regulates Scx-lineage tenocytes and Tppp3-lineage paratenon sheath cells in neonatal tendon regeneration. Nat Commun. 2025 Apr 20;16(1):3734. [CrossRef]

- Elhassan B, Moran SL, Bravo C, Amadio P. Factors That Influence the Outcome of Zone I and Zone II Flexor Tendon Repairs in Children. The Journal of Hand Surgery. 2006 Dec 1;31(10):1661–6. [CrossRef]

- Franke TF, Kaplan DR, Cantley LC. PI3K: Downstream AKTion Blocks Apoptosis. Cell. 1997 Feb 21;88(4):435–7. [CrossRef]

- Shih B, Bayat A. Scientific understanding and clinical management of Dupuytren disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010 Dec;6(12):715–26. [CrossRef]

- Carta G, Murru E, Banni S, Manca C. Palmitic Acid: Physiological Role, Metabolism and Nutritional Implications. Front Physiol. 2017 Nov 8;8:902. [CrossRef]

- Khan MJ, Rizwan Alam M, Waldeck-Weiermair M, Karsten F, Groschner L, Riederer M, et al. Inhibition of Autophagy Rescues Palmitic Acid-induced Necroptosis of Endothelial Cells. J Biol Chem. 2012 June 15;287(25):21110–20. [CrossRef]

- Liu N, Li Y, Nan W, Zhou W, Huang J, Li R, et al. Interaction of TPPP3 with VDAC1 Promotes Endothelial Injury through Activation of Reactive Oxygen Species. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020 Oct 2;2020:5950195. [CrossRef]

- Camara AKS, Zhou Y, Wen PC, Tajkhorshid E, Kwok WM. Mitochondrial VDAC1: A Key Gatekeeper as Potential Therapeutic Target. Front Physiol. 2017 June 30;8:460. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura H, Takada K. Reactive oxygen species in cancer: Current findings and future directions. Cancer Sci. 2021 Oct;112(10):3945–52. [CrossRef]

- Huang R, Chen M, Yang L, Wagle M, Guo S, Hu B. MicroRNA-133b Negatively Regulates Zebrafish Single Mauthner-Cell Axon Regeneration through Targeting tppp3 in Vivo. Front Mol Neurosci [Internet]. 2017 Nov 21 [cited 2025 July 22];10. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/molecular-neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnmol.2017.00375/full. [CrossRef]

- Rao M, Luo Z, Liu CC, Chen CY, Wang S, Nahmou M, et al. Tppp3 is a novel molecule for retinal ganglion cell identification and optic nerve regeneration. Acta Neuropathologica Communications. 2024 Dec 29;12(1):204. [CrossRef]

- Orosz, F. A New Protein Superfamily: TPPP-Like Proteins. PLoS One. 2012 Nov 14;7(11):e49276. [CrossRef]

- Kelliher MT, Saunders HAJ, Wildonger J. Microtubule control of functional architecture in neurons. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2019 Aug;57:39–45. [CrossRef]

- Oláh J, Lehotzky A, Szénási T, Berki T, Ovádi J. Modulatory Role of TPPP3 in Microtubule Organization and Its Impact on Alpha-Synuclein Pathology. Cells. 2022 Sept 27;11(19):3025. [CrossRef]

- Ross CA, Poirier MA. Protein aggregation and neurodegenerative disease. Nat Med. 2004 July;10(7):S10–7. [CrossRef]

- Zhang C, Liu J, Tan C, Yue X, Zhao Y, Peng J, et al. microRNA-1827 represses MDM2 to positively regulate tumor suppressor p53 and suppress tumorigenesis. Oncotarget. 2016 Jan 30;7(8):8783–96. [CrossRef]

- Mo Q, Liu X, Gong W, Wang Y, Yuan Z, Sun X, et al. Pinpointing Novel Plasma and Brain Proteins for Common Ocular Diseases: A Comprehensive Cross-Omics Integration Analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Sept 24;25(19):10236. [CrossRef]

- Zhu T, Zhou Y, Zhang L, Kong L, Tang H, Xiao Q, et al. A transcriptomic and proteomic analysis and comparison of human brain tissue from patients with and without epilepsy. Sci Rep. 2025 May 11;15(1):16369. [CrossRef]

- Pastor MD, Nogal A, Molina-Pinelo S, Meléndez R, Salinas A, González De la Peña M, et al. Identification of proteomic signatures associated with lung cancer and COPD. Journal of Proteomics. 2013 Aug 26;89:227–37. [CrossRef]

- Zeller T, Schurmann C, Schramm K, Müller C, Kwon S, Wild PS, et al. Transcriptome-Wide Analysis Identifies Novel Associations With Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2017 Oct;70(4):743–50. [CrossRef]

- Wen Y, Li C, Huang P, Liu Z, He Y, Liu B. Transcriptional landscape of intestinal environment in DSS-induced ulcerative colitis mouse model. BMC Gastroenterol. 2024 Feb 2;24:60. [CrossRef]

- Akshay A, Besic M, Kuhn A, Burkhard FC, Bigger-Allen A, Adam RM, et al. Machine Learning-Based Classification of Transcriptome Signatures of Non-Ulcerative Bladder Pain Syndrome. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Jan 26;25(3):1568. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Zhang Z, Hu X, Zhang Y. Epigenetic characterization of sarcopenia-associated genes based on machine learning and network screening. Eur J Med Res. 2024 Jan 16;29:54. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Shi M, Zhao X, Bin E, Hu Y, Tang N, et al. Telomere shortening impairs alveolar regeneration. Cell Prolif. 2022 Mar 11;55(4):e13211. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).