1. Introduction

Coeliac disease (CeD) is a T-cell mediated autoimmune enteropathy triggered by the consumption of gluten, a protein found in wheat, rye, and barley [

1]. During active CeD, individuals with underlying genetic risk suffer from small intestinal inflammation after the consumption of dietary gluten [

2]. This chronic inflammation causes villous atrophy, that can lead to symptoms including abdominal pain, diarrhoea, malabsorption, and malnutrition [

3]. Currently the only treatment for CeD is eliminating gluten from the diet of patients with CeD predisposition [

4].

The genetic background of CeD predisposition is still not fully understood, as only 50% of the genetic risk has been explored [

1]. The most well established CeD risk loci is the human leukocyte antigen (

HLA) complex [

1,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. The HLA-DQ2.5, HLA-DQ2.2, and HLA-DQ8 heterodimers are present in more than 80% of CeD patients [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. In contrast, about 20-30% of healthy controls have the CeD associated risk

HLA genotypes [

11,

12,

16]. These

HLA genotypes were estimated to explain about 30-40% of the total CeD genetic risk [

17,

18]. Recent evidence has shown the butyrophilin family of genes to be non-

HLA CeD risk loci of interest [

19,

20,

21].

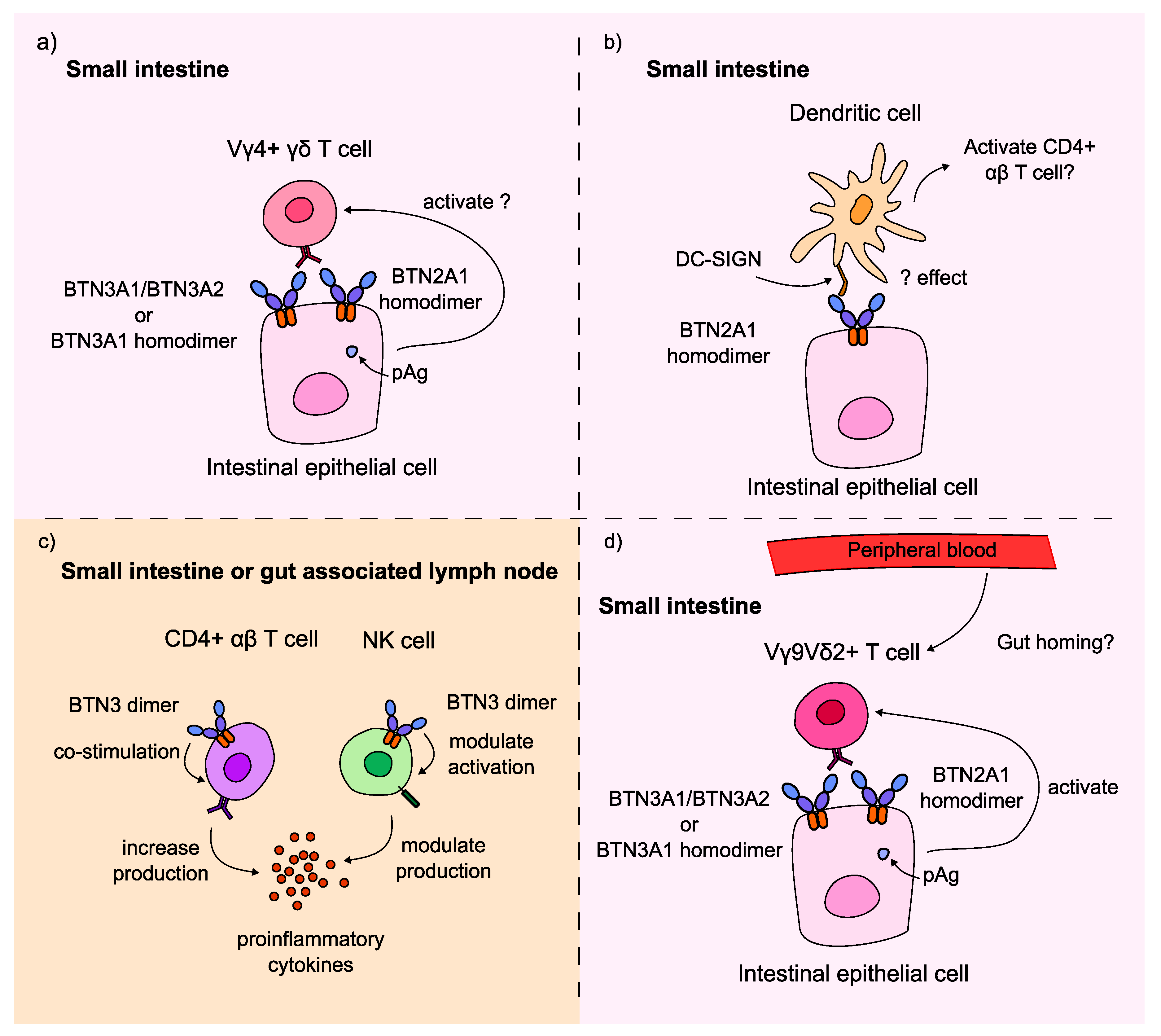

The butyrophilin proteins are a family of immunoglobulin-like cell surface receptors that have been shown to regulate both innate and adaptive immunity, including the activity of dendritic cells (DC), natural killer (NK) cells, αβ T cells, and γδ T cells [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Members of the butyrophilin family were found to maintain local γδ T-cell compartments in the blood and epithelia of both mice and humans (Table 1) [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. Hayday and Vantourout [

34] hypothesised that butyrophilin proteins serve as a steady state signal that maintains the local γδ T-cell population in a quiescent or inactive state. In the duodenum, the BTNL3/BTNL8 heterodimers act as the ligand for Vγ4+/Vδ1+ γδ intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) (Figure 1) [

21,

27,

28]. Specifically, the BTNL3/BTNL8 heterodimer binds the germline-encoded hypervariable region 4 (HV4) of T cell receptor gamma (TCR-γ), when the variable (V) gene segment encoding that TCR-γ is the

TRGV4 gene.

Table 1.

Butyrophilins maintain and activate the γδ T-cell compartments of mice and humans. Human butyrophilin family members are shortened with all letters capitalised, while only the first letter of mouse butyrophilins is capitalised [

24].

Table 1.

Butyrophilins maintain and activate the γδ T-cell compartments of mice and humans. Human butyrophilin family members are shortened with all letters capitalised, while only the first letter of mouse butyrophilins is capitalised [

24].

| |

Butyrophilins |

γδT-cell subset

|

Role of butyrophilins |

References |

| Peripheral blood |

Mouse unidentified |

Unidentified |

Unidentified |

NA |

| Alpaca BTN3 |

Vγ9Vδ2+ T cells |

No interaction has been identified |

[35,36] |

Human BTN3A homodimers/

heterodimers and BTN2A1 homodimer |

Vγ9Vδ2+ T cells |

Phosphoantigen mediated, CDR3-independent γδ T-cell activation |

[30,33,37,38] |

| Skin |

Mouse Skint1 and Skint2 |

Vγ5Vδ1+ DETC |

Thymic selection, tissue homing of dendritic epidermal T cells to the skin |

[27,28,32] |

| Human ? |

Vδ1+ T cells |

Unidentified, unknown if there is butyrophilin involvement |

[39] |

| Intestinal epithelium |

Mouse Btnl1 and Btnl6 |

Vγ7+ IEL |

Phenotypic maintenance of the intestinal IEL compartment |

[27,28] |

| Human BTNL3 and BTNL8 |

Vγ4Vδ1+ IEL |

Phenotypic maintenance of the intestinal IEL compartment |

[21,27,29] |

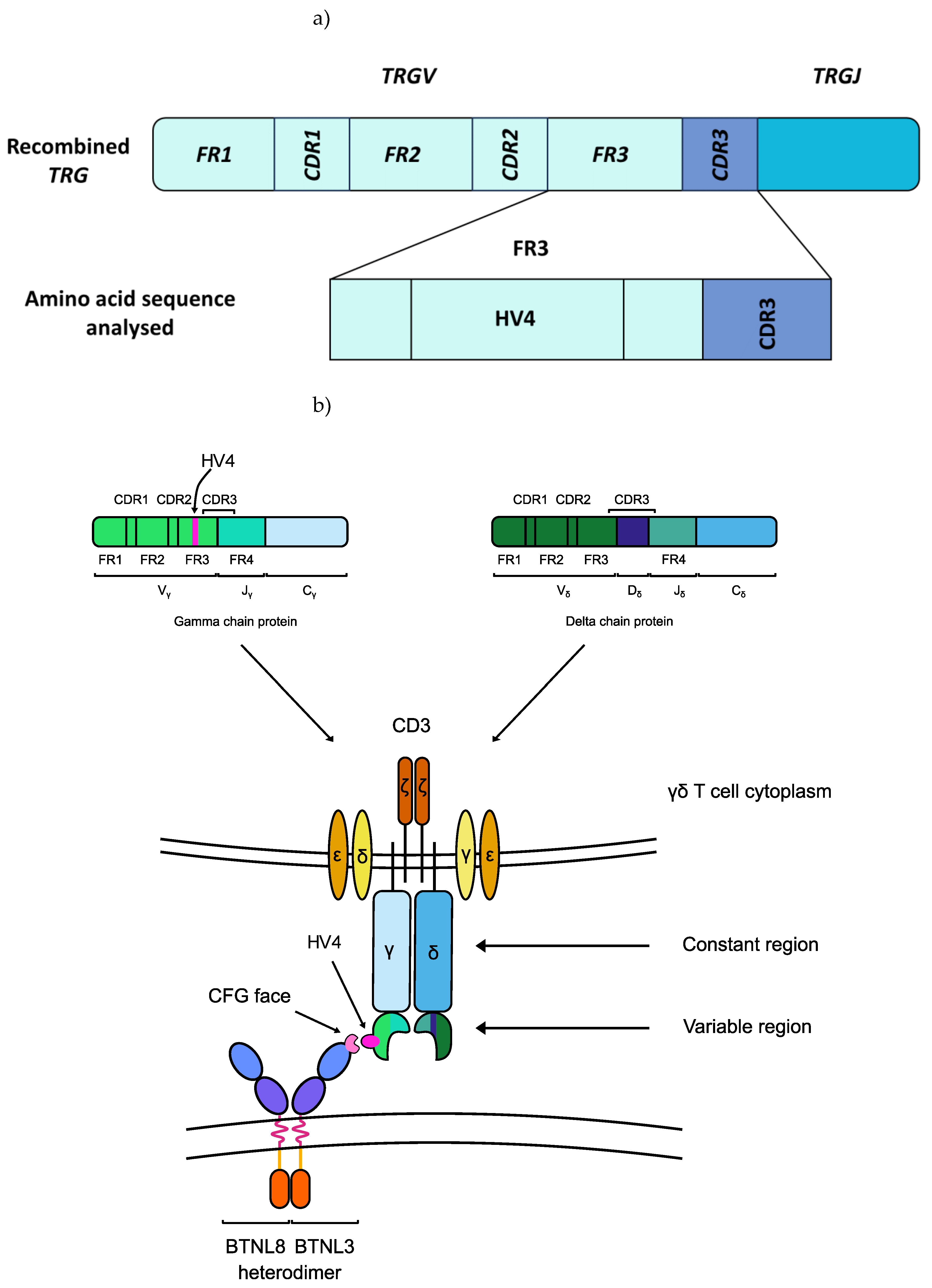

Figure 1.

The germline-encoded HV4 loop of the T cell receptor (TCR) of Vγ4+ γδ IELs directly binds to BTNL3. a) HV4 is located at amino acid positions 10-25 in the FR3 of the TRGV4 segment [

31]. b) The HV4 of Vγ4+ γδ T cells binds to the C, C”, F, and G canonical immunoglobulin-fold β-strands (CFG face) of the BTNL3 protein [

29]. Abbreviations: CDR: complementarity-determining region; FR: framework region; HV4: hypervariable region 4; TRGJ: T cell receptor γ joining region; TRGV: T cell receptor γ variable region.

Figure 1.

The germline-encoded HV4 loop of the T cell receptor (TCR) of Vγ4+ γδ IELs directly binds to BTNL3. a) HV4 is located at amino acid positions 10-25 in the FR3 of the TRGV4 segment [

31]. b) The HV4 of Vγ4+ γδ T cells binds to the C, C”, F, and G canonical immunoglobulin-fold β-strands (CFG face) of the BTNL3 protein [

29]. Abbreviations: CDR: complementarity-determining region; FR: framework region; HV4: hypervariable region 4; TRGJ: T cell receptor γ joining region; TRGV: T cell receptor γ variable region.

During active CeD, these γδ T cells, alongside CD4+ and CD8+ αβ IELs are activated by dietary gluten [

40]. Mayassi

, et al. [

21] showed the loss of interaction between BTNL3/BTNL8 heterodimers and the duodenal Vγ4+ γδ T cells as a characteristic of active CeD in a study of 62 active CeD, 57 gluten-free diet (GFD) treated CeD, and 99 control participants. During chronic inflammation induced by dietary gluten, the expression of the BTNL3/BTNL8 heterodimer was lost in the small intestine of patients having CeD predisposition. This was accompanied by the permanent loss of BTNL3/BTNL8-reactive Vγ4+/Vδ1+ γδ T cells. The chronic inflammation only subsided when patients followed a GFD. Although the BTNL3/BTNL8 expression recovered, the local γδ TCR repertoire was permanently reshaped: the innate-like Vγ4+/Vδ1+ γδ T cells and T cell receptor γ variable region 4 (

TRGV4) gene transcripts were significantly decreased [

21].

Recently, a common

BTNL8*BTNL3 56-kb deletion copy number variant (CNV) was described by Aigner

, et al. [

41] in a cohort of more than 4000 samples. The

BTNL3 and

BTNL8 loci are segmental duplications and share a high sequence similarity. During meiosis, highly identical sequences are prone to recombination, which can give rise to CNVs. Aigner

, et al. [

41] reported 58.4% of their 346 samples of European ancestry had at least one

BTNL8*BTNL3 deletion allele (Table 2). This CNV has been shown to encode a BTNL8*3 fusion protein, which consists of the transmembrane domain, the extracellular IgV and IgC domains of BTNL8, and the intracellular signalling domain of BTNL3. As the BTNL3-IgV domain is missing in the fusion protein, it is plausible that the BTNL8*3 fusion protein has an impaired ability to bind to the Vγ4Vδ1+ T cells in the small intestine [

31]. As Mayassi

, et al. [

21] observed a permanent shift in the duodenal γδ TCR repertoire when the interaction between the T cells and the BTNL3/BTNL8 heterodimer was disrupted, this fusion protein could predispose carriers to CeD.

Table 2.

The

BTNL8*BTNL3 copy number variation is present in 58.4% of individuals of European ancestry, as first described by Aigner

, et al. [

41]. Carriers are defined as individuals with at least one

BTNL8*BTNL3 deletion allele. Abbreviations: CEU: Utah residents with Northern and Western European ancestry; HapMap: International HapMap Project; het.: heterozygous; HGDP: Human Genome Diversity Panel; hom.: homozygous; N: number.

Table 2.

The

BTNL8*BTNL3 copy number variation is present in 58.4% of individuals of European ancestry, as first described by Aigner

, et al. [

41]. Carriers are defined as individuals with at least one

BTNL8*BTNL3 deletion allele. Abbreviations: CEU: Utah residents with Northern and Western European ancestry; HapMap: International HapMap Project; het.: heterozygous; HGDP: Human Genome Diversity Panel; hom.: homozygous; N: number.

| |

Population |

Hom. for deletion |

Het. for deletion |

Hom. for full sequences |

Deletion allele N |

Deletion allele frequency |

Group N |

Carriers N |

Carriers

%

|

| HapMap |

CEU |

17 |

56 |

68 |

90 |

0.319 |

141 |

73 |

51.8 |

| Toskani, Italia |

9 |

45 |

34 |

63 |

0.358 |

88 |

54 |

61.4 |

| HGDP |

France |

7 |

28 |

17 |

42 |

0.404 |

52 |

35 |

67.3 |

| Italy |

5 |

18 |

13 |

28 |

0.389 |

36 |

23 |

63.9 |

| Italy (Bergamo) |

3 |

2 |

9 |

8 |

0.286 |

14 |

5 |

35.7 |

| Orkney Islands |

1 |

11 |

3 |

13 |

0.433 |

15 |

12 |

80.0 |

| Total |

European ancestry |

42 |

160 |

144 |

244 |

0.353 |

346 |

202 |

58.4 |

Alongside

BTNL3 and

BTNL8,

BTNL2 and

BTN3A1 were also implicated in CeD risk. Goudey

, et al. [

19] have identified 14 SNPs associated with CeD, independent of the known CeD risk

HLA loci in a study of 763 CeD and 1420 control samples. One of the SNPs was located in the proximity of

BTNL2, a gene harbouring among the highest density of GWAS hits in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases from the butyrophilin family [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48]. Goudey

, et al. [

19] showed that this SNP was marked as being an expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) for the

BTNL2 gene in RegulomeDB, a database annotating the function of non-coding SNPs [

49,

50]. Furthermore, RegulomeDB also reported high evidence for transcription factor binding for this eQTL [

19].

In a separate a paediatric study of 26 active CeD, 5 treated CeD and 25 control subjects,

BTN3A1 expression was associated with active CeD in children [

20]. The study examined the differential expression of more than 25 defence-related genes in the three subject groups, demonstrating the upregulation of

BTN3A1 mRNA and protein expression in the intestinal epithelial cells of children with active CeD. This is an intriguing finding, as BTN3A1 is required for the phosphoantigen (pAg)-induced activation of Vγ9Vδ2+ T cells in peripheral blood, a subset of γδ T cells not previously been implicated in CeD. These two studies indicate that the full functions and roles of the butyrophilin family of proteins in immunomodulation remain to be explored.

These findings raise a previously unexplored question about CeD risk. Do certain individuals co-inherit polymorphisms in their TRGV4 gene segments and their butyrophilin family genes that predispose them to CeD. In this study, using a 94 patient discovery cohort and the UK Biobank’s genome-wide genotyping dataset of 25 192 participants for validation, we show that 14 BTN2A1, 10 BTN3A1, and 13 BTN3A2 SNPs are significantly associated with CeD status.

2. Results

2.1. BTN2A1 SNPs Were Significantly Associated with CeD Risk in a Study of 94 Samples

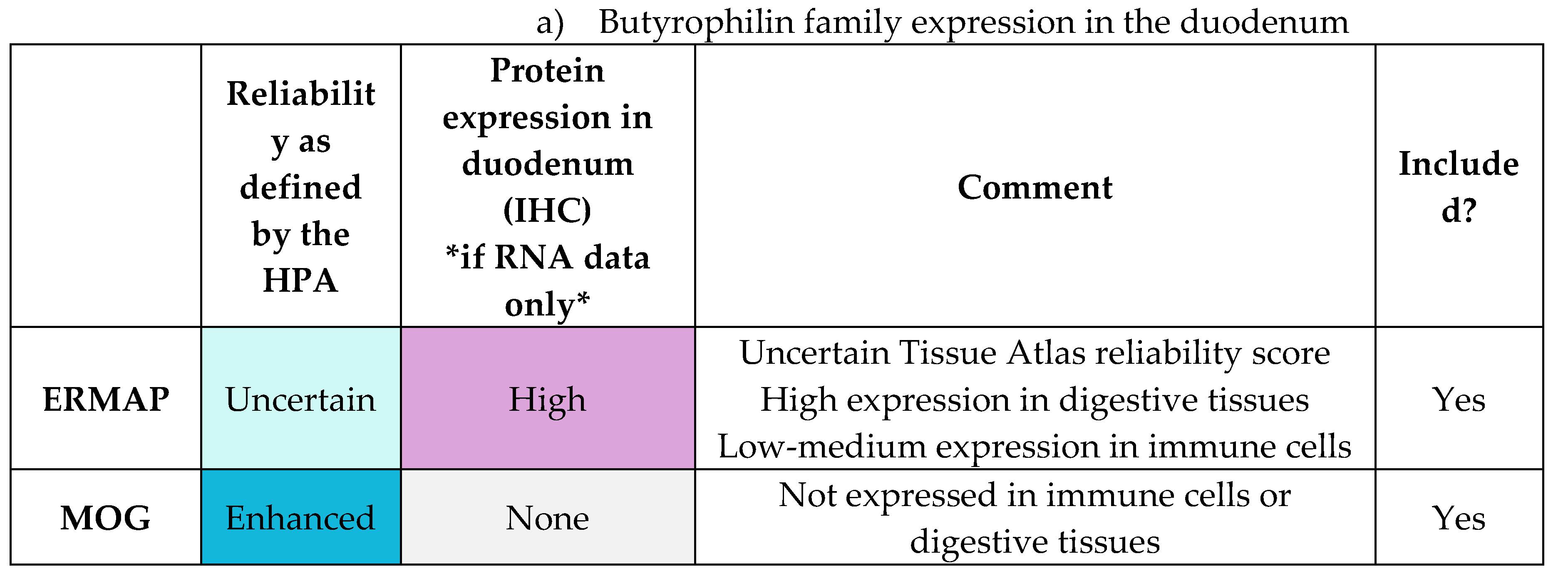

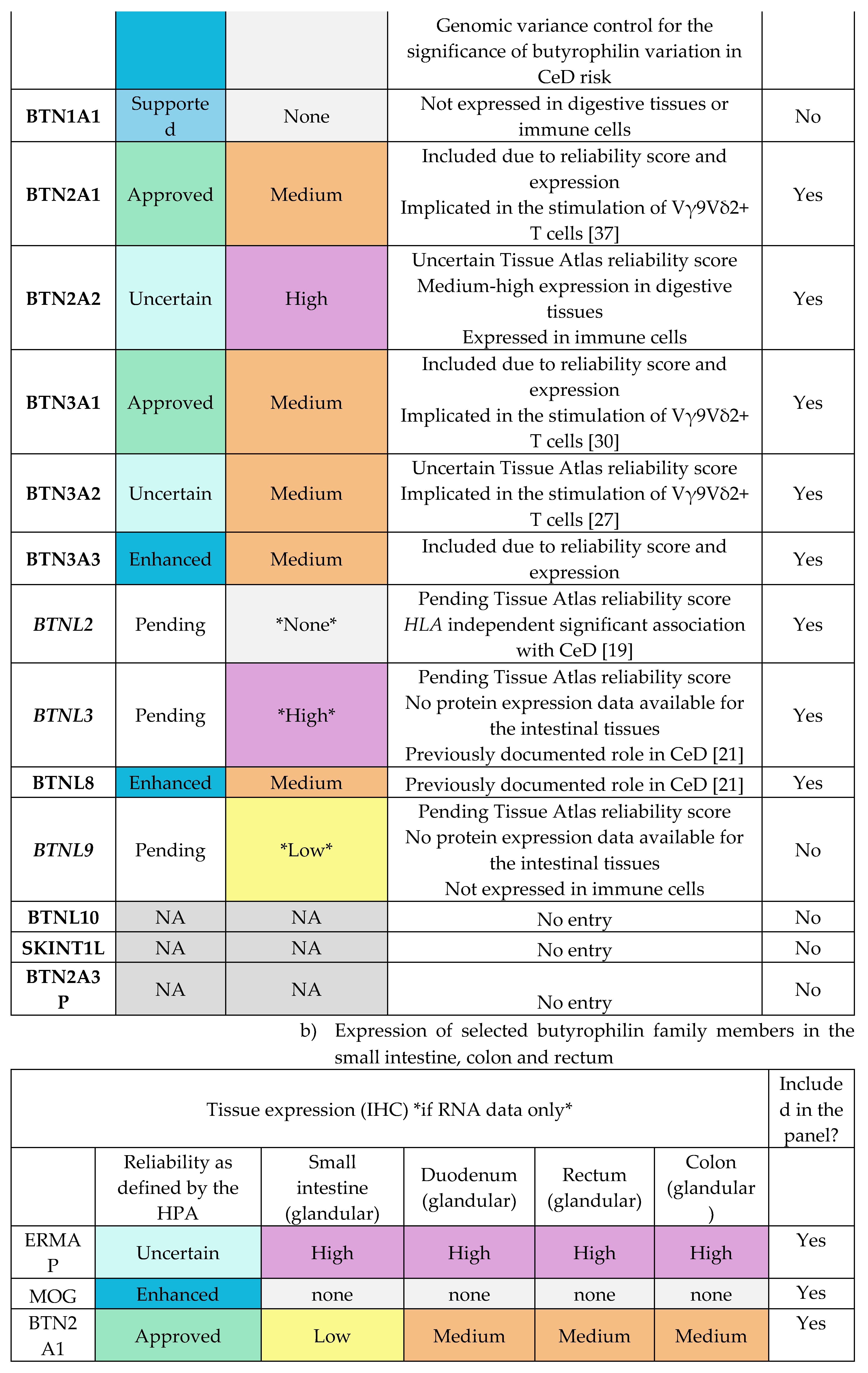

To investigate the association between butyrophilin genes and CeD risk, a cohort of 48 CeD and 46 control patients was examined. The HLA loci and selected butyrophilin genes of interests were sequenced from patient samples. The following butyrophilin genes were selected as putative CeD risk loci based on their gene expression profile in the duodenum, small intestines and immune cells (Table E1-E2) and their role in immunomodulation: BTN2A1, BTN2A2, BTN3A1, BTN3A2, BTN3A3, BTNL2, BTNL3, BTNL8, ERMAP, and MOG.

2.1.1. Risk Associated HLA Genotypes Were Significantly More Frequent in CeD Patients

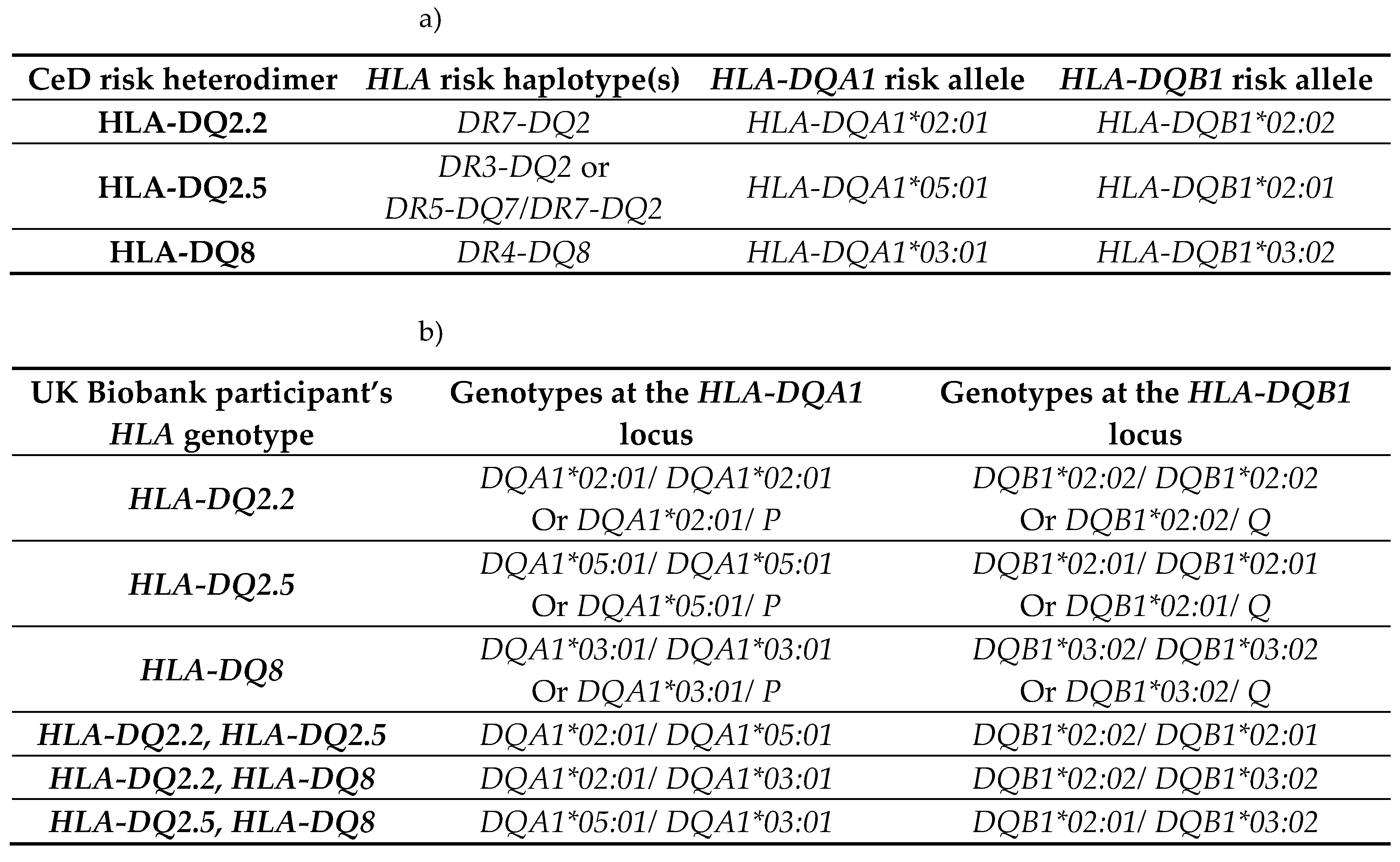

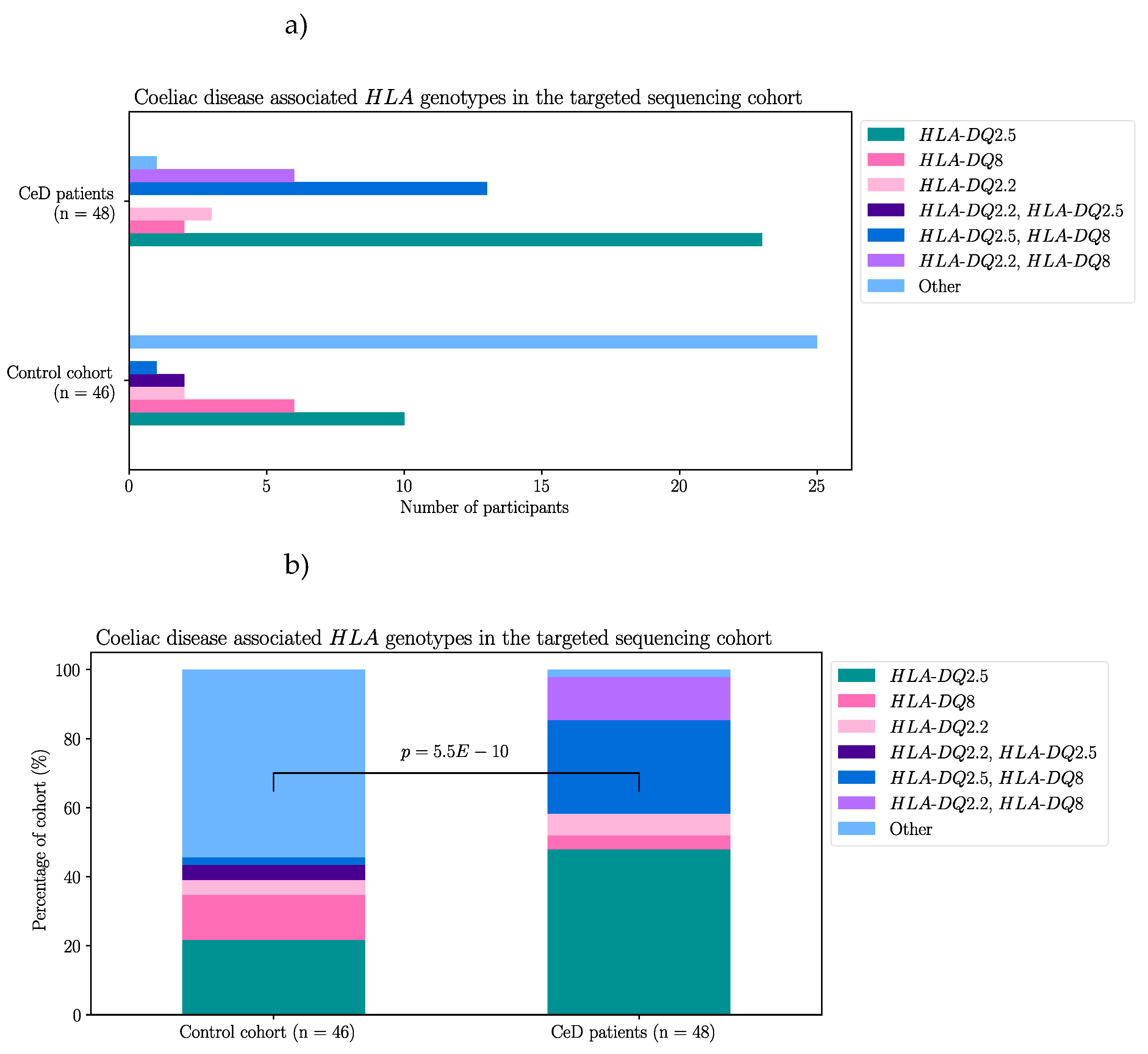

First, by way of data quality control, the

HLA genotypes of the samples were examined. In accordance with previous literature, the majority of the CeD patients had CeD risk associated

HLA genotypes (Table 3a) [

11,

13,

51]. The percentage of individuals identified as having one or more

HLA risk genotypes from the CeD group was 95.8% (46/48). Only two CeD patients had

HLA genotypes other than the CeD risk associated ones (4.17%) (Table 3b). In contrast, non-risk

HLA genotypes were the most frequent in the control group (54.3%, 25/46) (Figure A1, Fisher’s exact test,

p = 5.5E-10). To summarise, CeD risk associated

HLA genotypes were significantly more frequent in CeD patients than in the controls of this dataset.

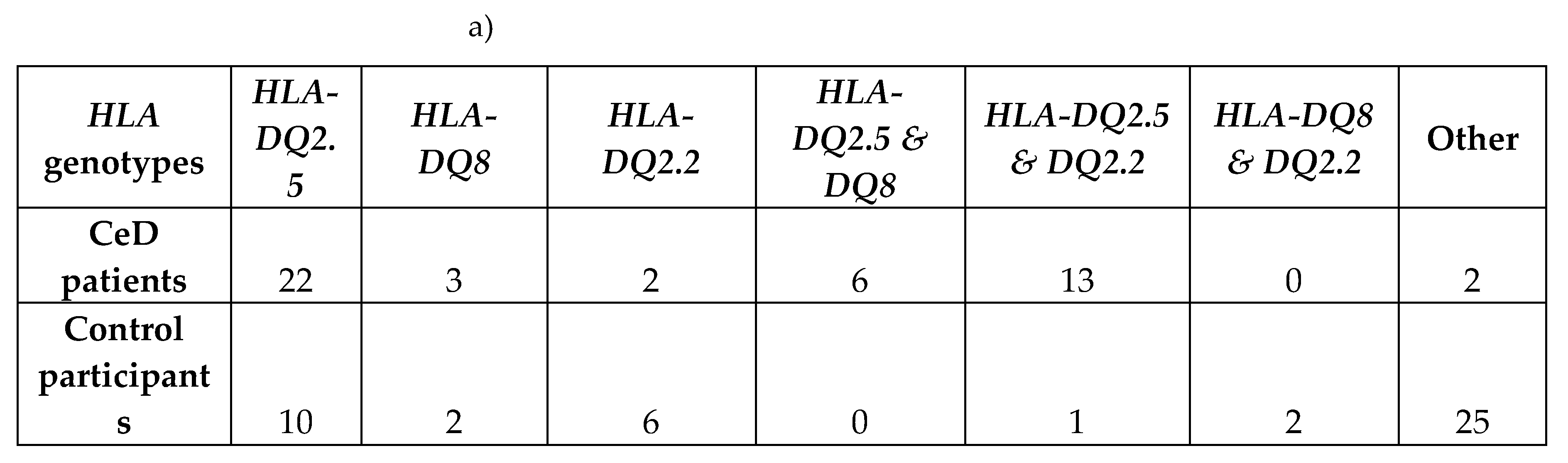

Table 3.

CeD associated HLA genotypes were found in 95.8% of CeD patients (n = 48) and 45.7% of controls (n = 46). a) The CeD risk associated

HLA genotypes were called using HLA-HD [

52]. b) The

HLA-DQA1 and

HLA-DQB1 alleles of the two CeD patients, who did not have CeD risk associated

HLA genotypes. The

HLA-DQA1 allele of sample CD1 could not be typed by HLA-HD. CeD patients possessed a significantly higher proportion of risk

HLA genotypes, when compared with controls in this dataset (Figure A1, Fisher’s exact test,

p = 5.5e-10).

Table 3.

CeD associated HLA genotypes were found in 95.8% of CeD patients (n = 48) and 45.7% of controls (n = 46). a) The CeD risk associated

HLA genotypes were called using HLA-HD [

52]. b) The

HLA-DQA1 and

HLA-DQB1 alleles of the two CeD patients, who did not have CeD risk associated

HLA genotypes. The

HLA-DQA1 allele of sample CD1 could not be typed by HLA-HD. CeD patients possessed a significantly higher proportion of risk

HLA genotypes, when compared with controls in this dataset (Figure A1, Fisher’s exact test,

p = 5.5e-10).

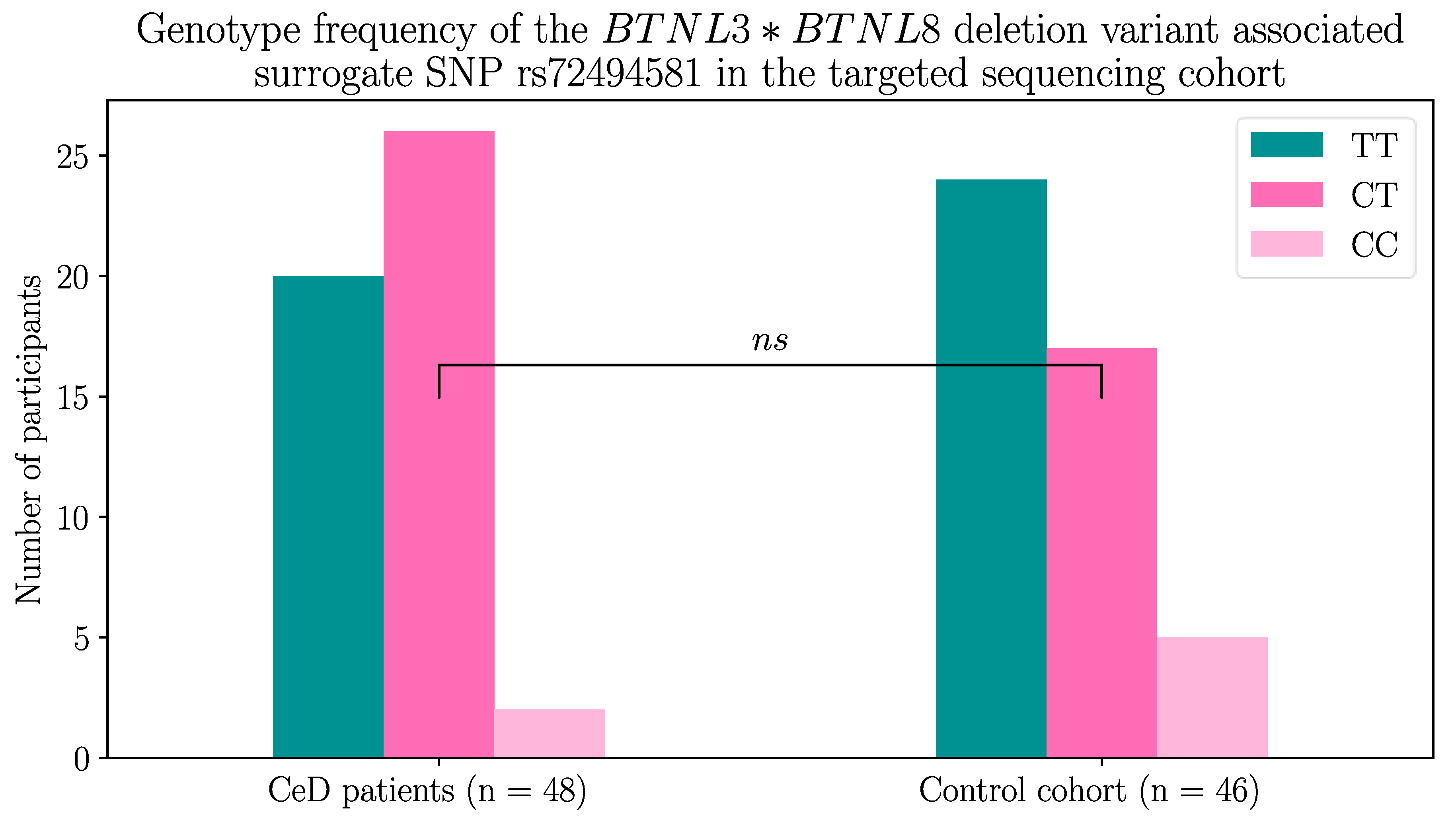

2.1.2. The BTNL8*BTNL3 Copy Number Variant Was not Associated with CeD

Next, the

BTNL8-BTNL3 loci were examined for the presence of the deletion CNV. This CNV encodes a truncated fusion protein lacking the BTNL3-IgV extracellular domain required for maintaining the duodenal Vγ4+ γδ T cells, which we hypothesised could increase CeD risk [

21,

29,

31,

41].

The presence of the CNV was determined using a surrogate SNP. Dart

, et al. [

53] identified the rs72494581 minor allele to be associated with the presence of the deletion variant. Using this method, 58.3% (28/48) of the CeD patients and 47.8% (22/46) of the control participants were found to possess at least one deletion variant, which is in accordance with the findings of Aigner

, et al. [

41] (Table 4). Interestingly, 10.9% (5/46) of controls were homozygous for the

BTNL8*BTNL3 deletion compared to only 4.2% (2/48) of CeD patients, but this did not reach statistical significance (Figure A2, Fisher’s exact test,

p = 0.2144).

Table 4.

At least 47% of CeD patients (n = 48) and controls (n = 46) had the

BTNL8*BTNL3 deletion variant using the rs72494581 surrogate SNP. The

BTNL8*BTNL3 deletion variant encodes a truncated BTNL8-BTNL3 fusion protein [

41]. Dart

, et al. [

53] identified rs72494581 in the intronic region of

BTNL3, which serves as a surrogate SNP and the alleles are associated with the

BTNL8*BTNL3 copy number variant. The major allele, the

T allele, is associated with the full length

BTNL3 and

BTNL8 genes, while the minor allele, the

C allele, is associated with the

BTNL8*BTNL3 deletion. The differences between the frequencies in CeD and control individuals failed to reach statistical significance (Figure A2, Fisher’s exact test,

p = 0.2144).

Table 4.

At least 47% of CeD patients (n = 48) and controls (n = 46) had the

BTNL8*BTNL3 deletion variant using the rs72494581 surrogate SNP. The

BTNL8*BTNL3 deletion variant encodes a truncated BTNL8-BTNL3 fusion protein [

41]. Dart

, et al. [

53] identified rs72494581 in the intronic region of

BTNL3, which serves as a surrogate SNP and the alleles are associated with the

BTNL8*BTNL3 copy number variant. The major allele, the

T allele, is associated with the full length

BTNL3 and

BTNL8 genes, while the minor allele, the

C allele, is associated with the

BTNL8*BTNL3 deletion. The differences between the frequencies in CeD and control individuals failed to reach statistical significance (Figure A2, Fisher’s exact test,

p = 0.2144).

| rs72494581 genotype |

TT |

CT |

CC |

|

BTNL8-BTNL3genes

|

Homozygous for full length sequence |

Heterozygous for BTNL8*BTNL3 deletion |

Homozygous for BTNL8*BTNL3 deletion |

| Coeliac disease patients |

20 |

26 |

2 |

| Control participants |

24 |

17 |

5 |

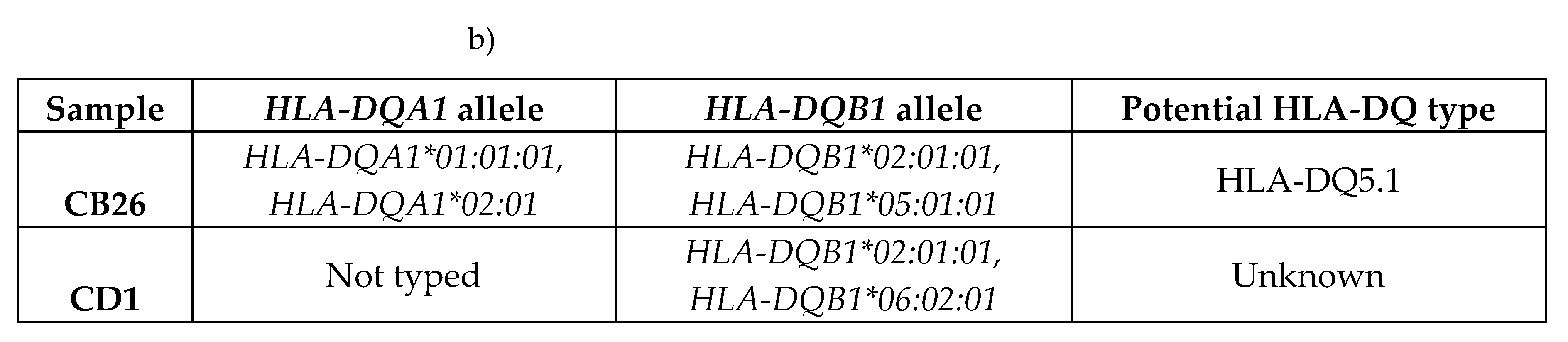

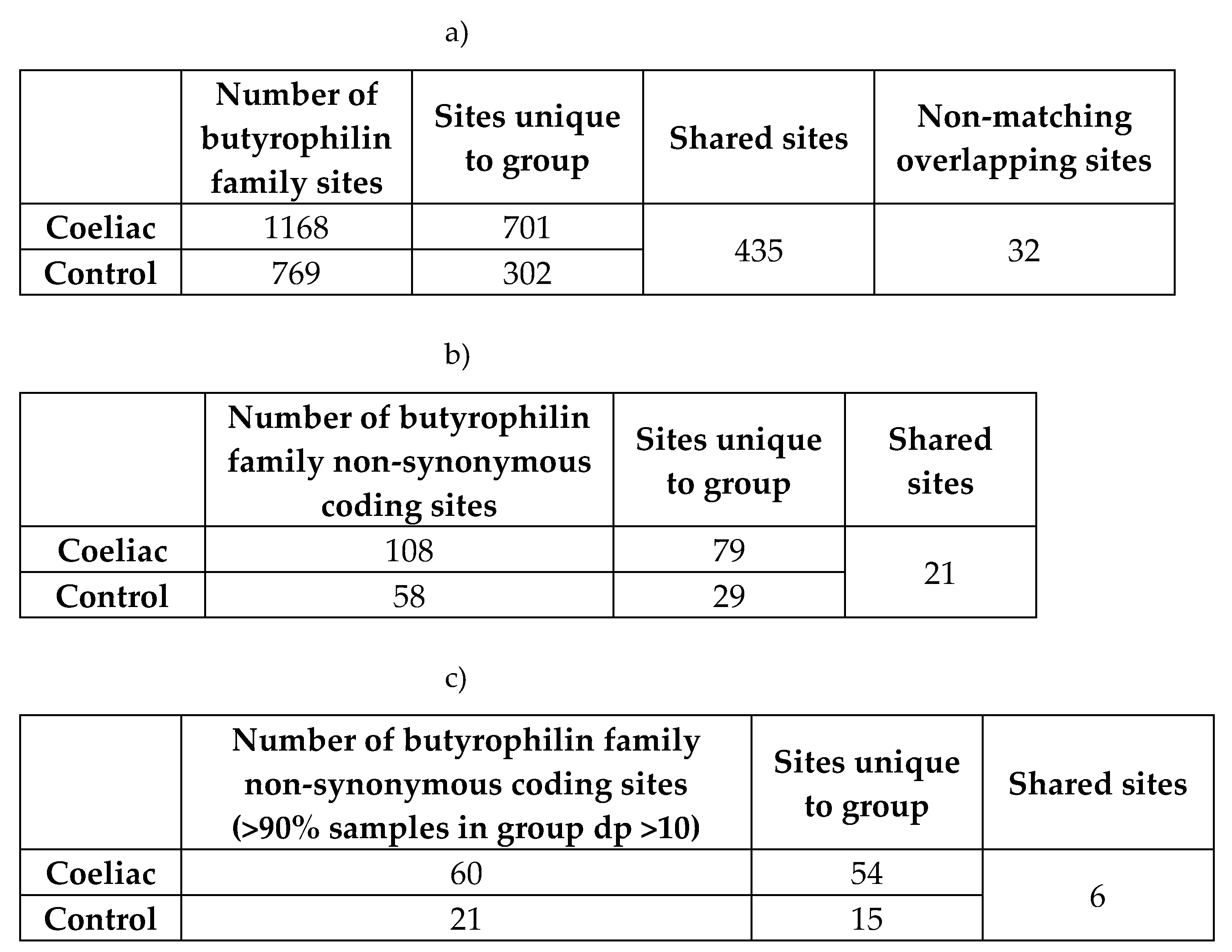

2.1.3. BTN2A1 Gene Burden was Significantly Higher in CeD Patients

To determine whether any of the butyrophilin family variants were associated with CeD risk, gene-based burden testing, using the TRAPD program [

54], was carried out on the non-synonymous coding variants identified in the CeD patients of the cohort. The variants identified in CeD samples were burden tested against variants present in the control samples.

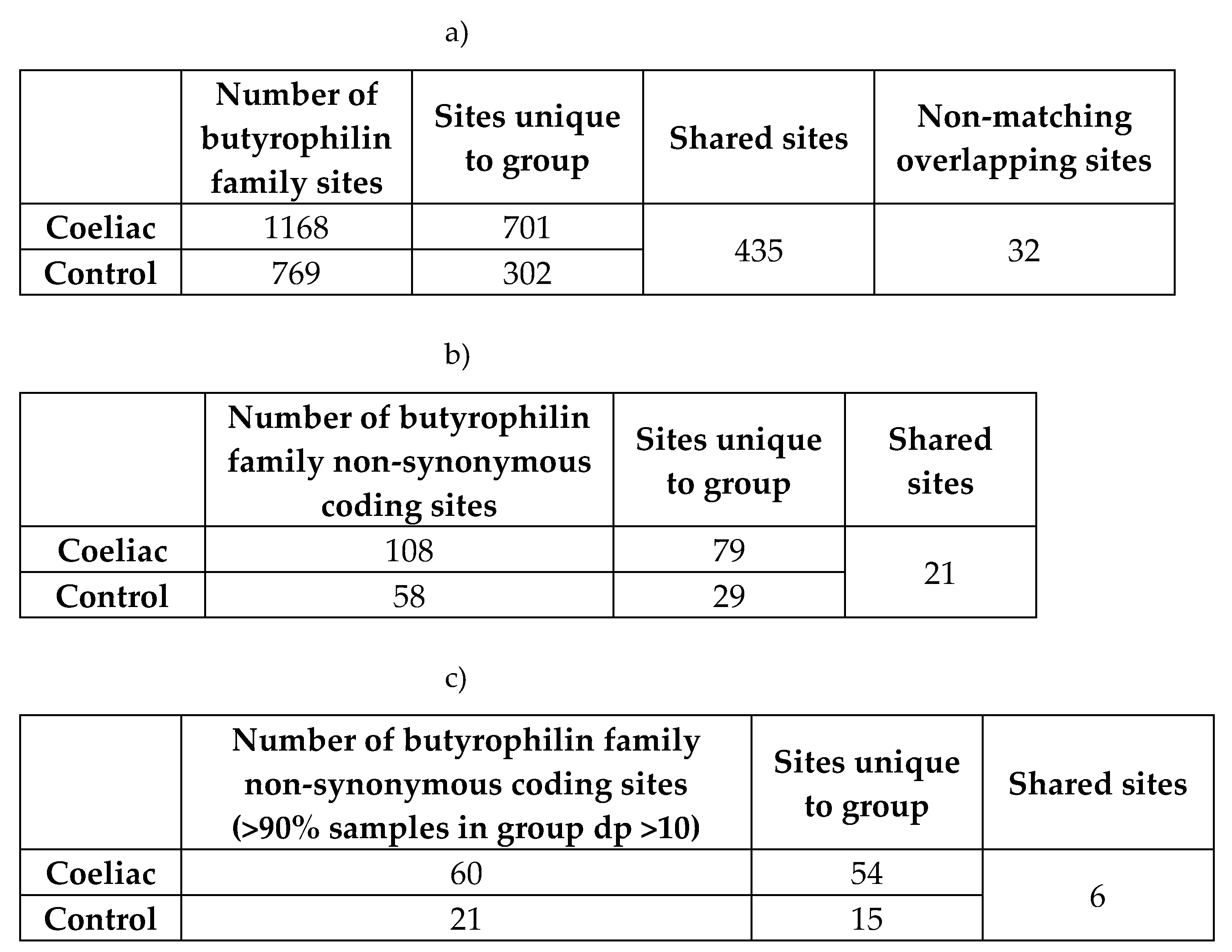

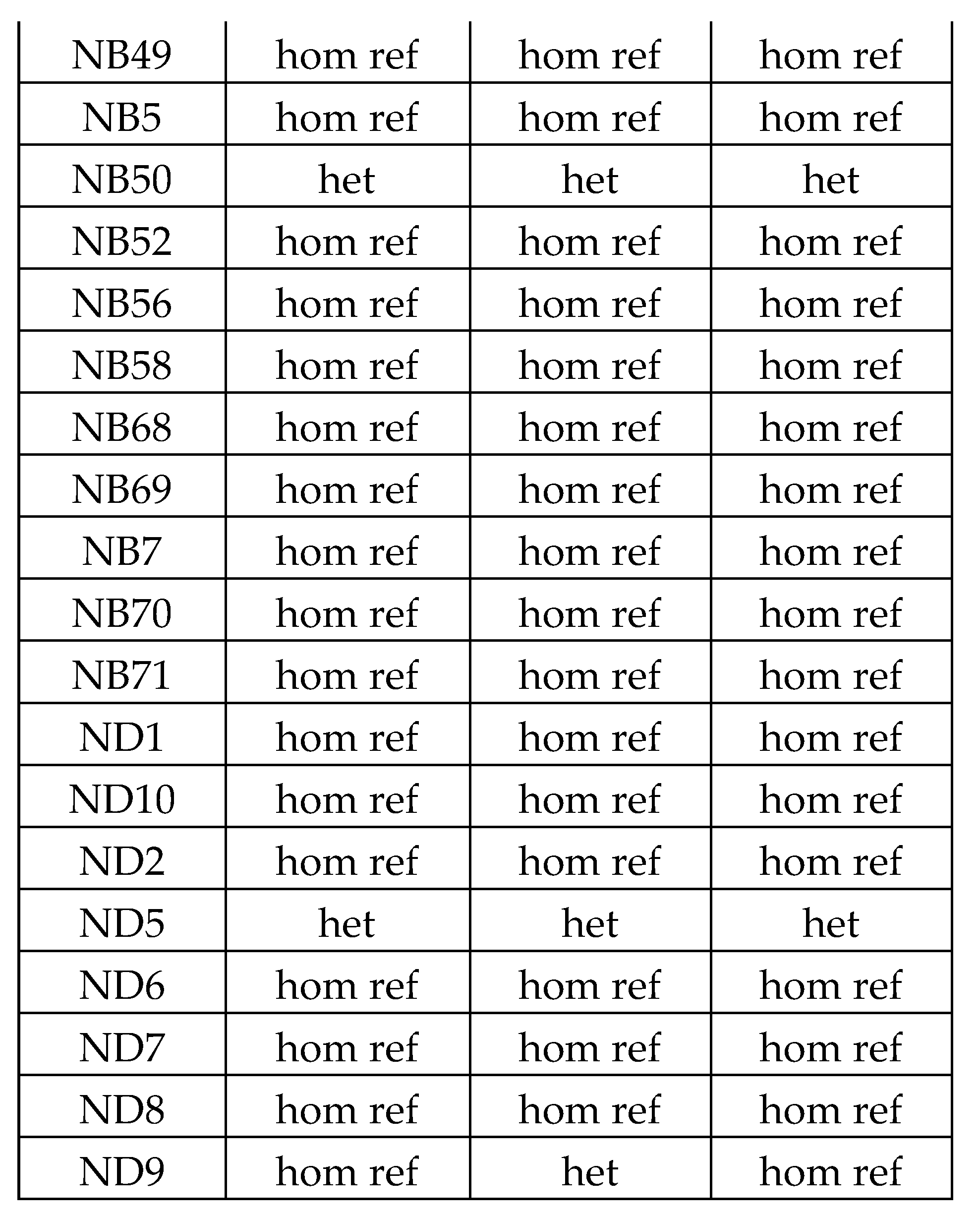

The analysis was carried out on the qualifying variants that passed read depth filtering. Of the 108 and 58 non-synonymous coding variants discovered in the CeD and control samples respectively, only 5 bi-allelic SNPs shared by both the CeD and control groups qualified for burden testing (Table 5, Table A1-A2). Only BTN2A1 variants were significantly associated with CeD risk gene burden in both the dominant (p = 1.46E-05) and the recessive (p = 3.70E-08) models, indicating that the presence of a single qualifying BTN2A1 SNP significantly increased CeD risk (Table 5b). BTN2A1 variants were more frequent in CeD patients, as 45.8% (22/48) of CeD participants had at least one qualifying BTN2A1 variant compared to 10.9% (5/46) of controls. To summarise, the gene burden analysis of butyrophilin genes in CeD patients compared with controls showed a significant association between BTN2A1 gene burden and CeD risk.

Table 5.

Gene-based burden testing of butyrophilin family non-synonymous coding variants in CeD patients (n = 48) against controls (n = 46) showed significant differences in the disease burden of BTN2A1 variants.

Table 5.

Gene-based burden testing of butyrophilin family non-synonymous coding variants in CeD patients (n = 48) against controls (n = 46) showed significant differences in the disease burden of BTN2A1 variants.

Non-synonymous coding variants that were predicted to be pathogenic or had low minor allele frequencies were considered qualifying variants for burden testing. a) Burden tests were carried out using the TRAPD program [

54] on butyrophilin family qualifying variants in CeD patients (n = 48) against controls (n = 46). Multiallelic sites were separated into bi-allelic SNPs, as required by the TRAPD documentation [

55]. Only sites where more than 90% of samples had a read depth coverage of >10 were selected.

The dominant model defines carriers for gene burden as individuals with at least one qualifying variant within a gene, while the recessive model requires at least two or more qualifying variants. Significant results were highlighted in bold. A version of table a) with the percentage of individuals and alleles within the CeD and the control groups can be found in Table A2.

b) shows the BTN2A1 qualifying SNPs having significant burden in CeD samples. Count data of individuals and alleles are in parentheses after the percentage value in columns 6-9 and columns 10-11 respectively. The percentage and count data were calculated from the per sample genotypes found in Table A3.

Abbreviations: Alt allele: alternative or minor allele; CeD: coeliac disease; GRCh38: Genome Reference Consortium Human Build 38; HET: heterozygous, HOM ALT: homozygous for alternative allele; N(≥1 HET): number of individuals carrying at least one heterozygous qualifying variant within the gene; N(≥2 HET): number of individuals carrying at least two heterozygous qualifying variant within the gene; N(HOM ALT): number of individuals carrying at least one homozygous qualifying variant within the gene; qual: qualifying; SNP: single nucleotide polymorphism

Although these results were promising, due to the

BTN2A1 gene being part of the extended MHC region and its close proximity (~4Mb) to the classical MHC region (6p21.3), we could not exclude the possibility that this significant association could be secondary to the risk associated

HLA genotypes of the CeD patients [

56,

57]. Therefore, these results were validated in a larger cohort using the UK Biobank dataset, by single variant testing

BTN3A1, BTN3A2, BTN2A1, BTNL3, and

BTNL8 SNPs present in the 500,000 genome-wide genotyping dataset.

2.2. BTN3A1, BTN3A2, and BTN2A1 Genes Were significantly Associated with CeD in HLA-DQ2.5-Matched Participants of the UK Biobank Database

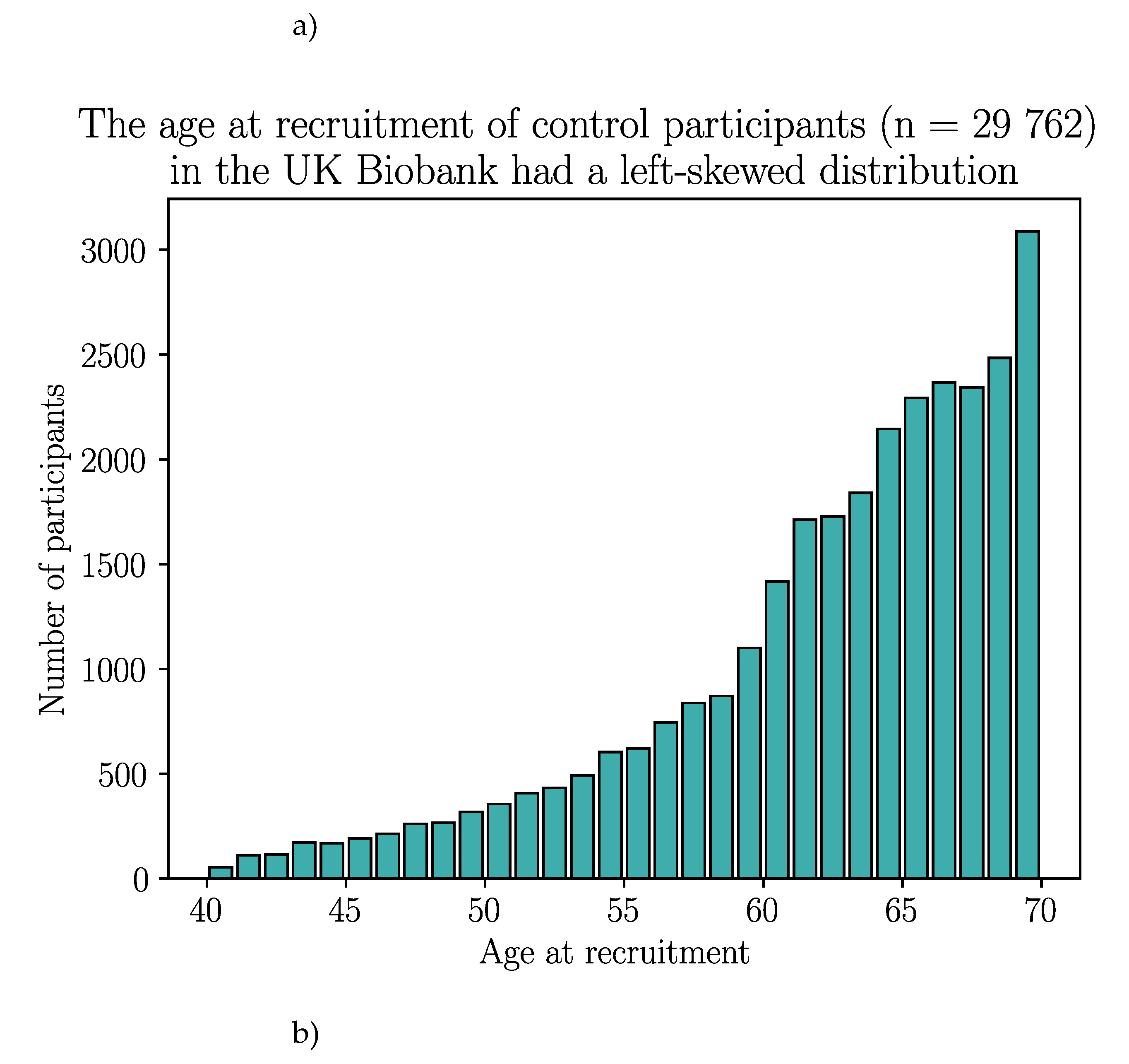

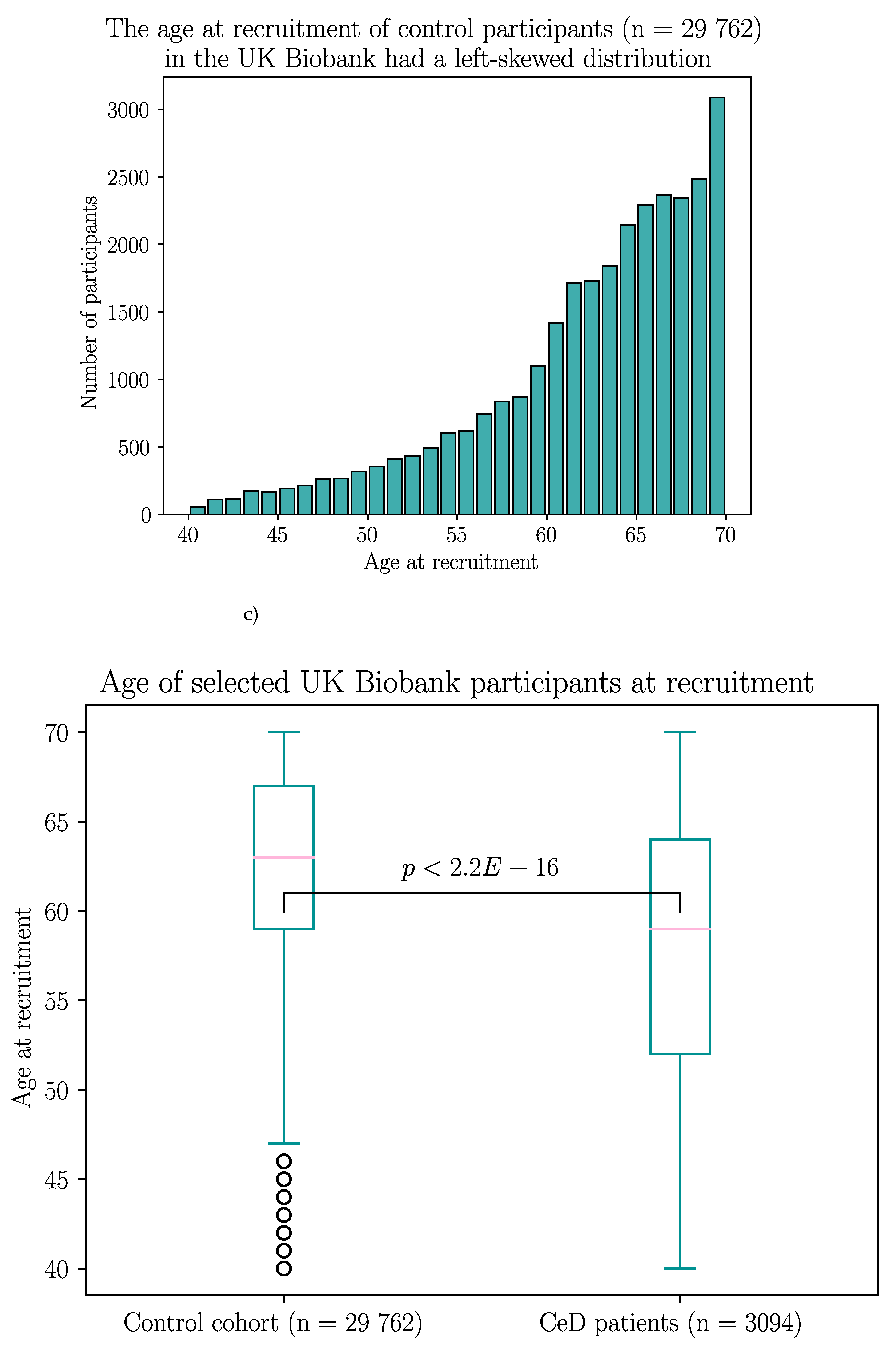

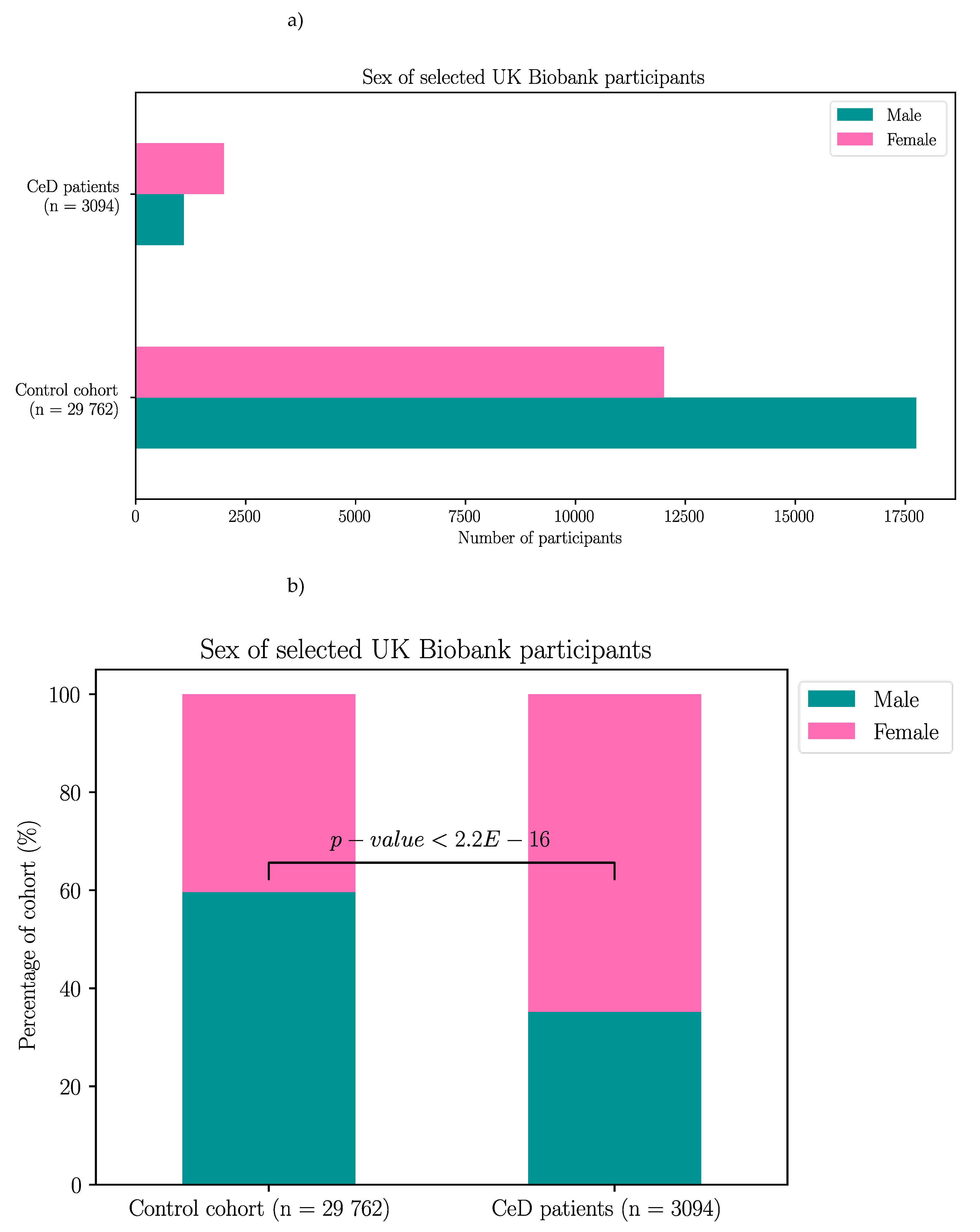

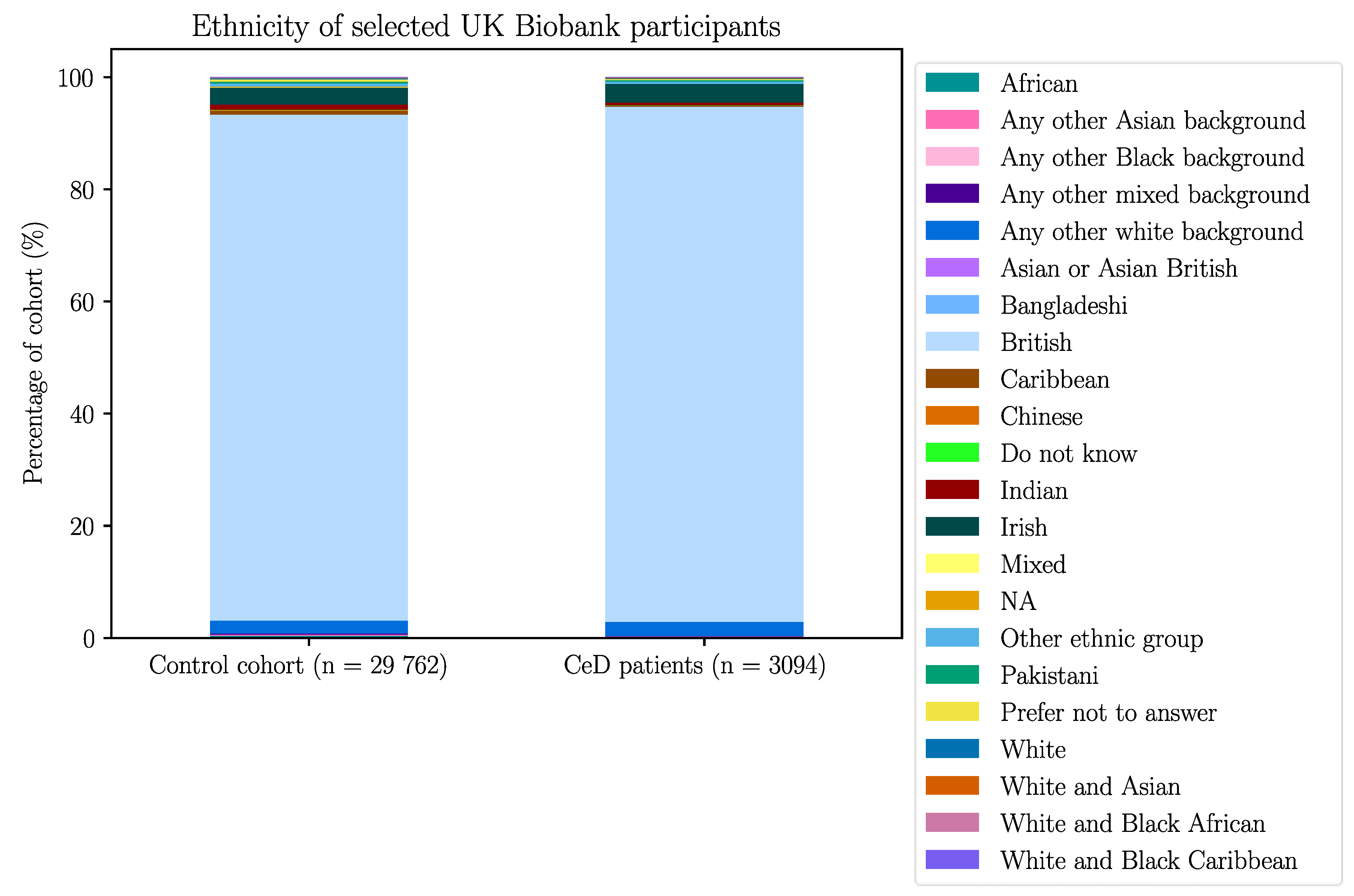

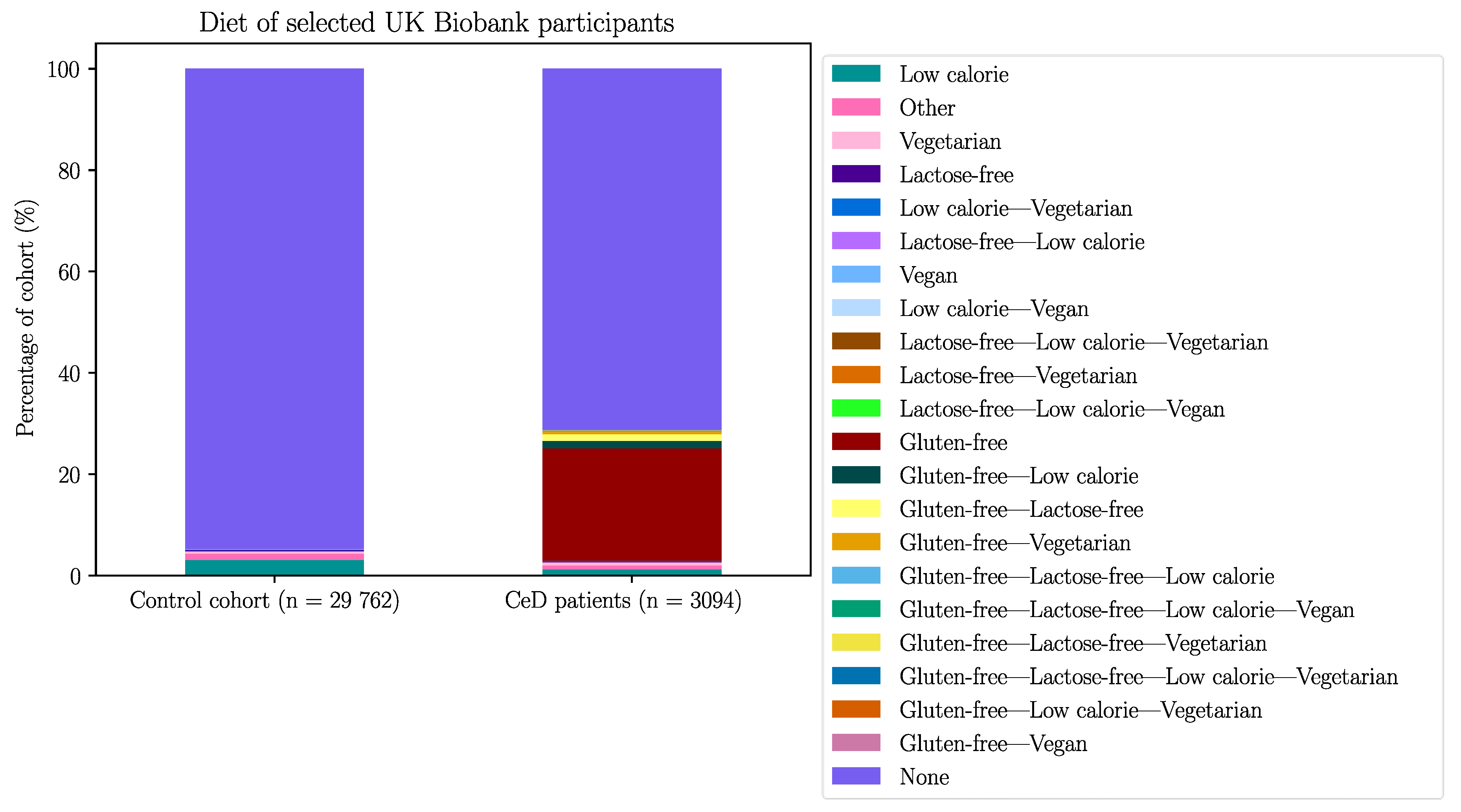

The UK Biobank dataset was used to validate the association between BTN2A1 and CeD risk, and to investigate the association between CeD and butyrophilin SNPs in potentially CeD-relevant genes. After removing participants with missing HLA imputation or genotype data, the final cohort consisted of 3094 CeD patients and 29 762 control participants (Appendix B).

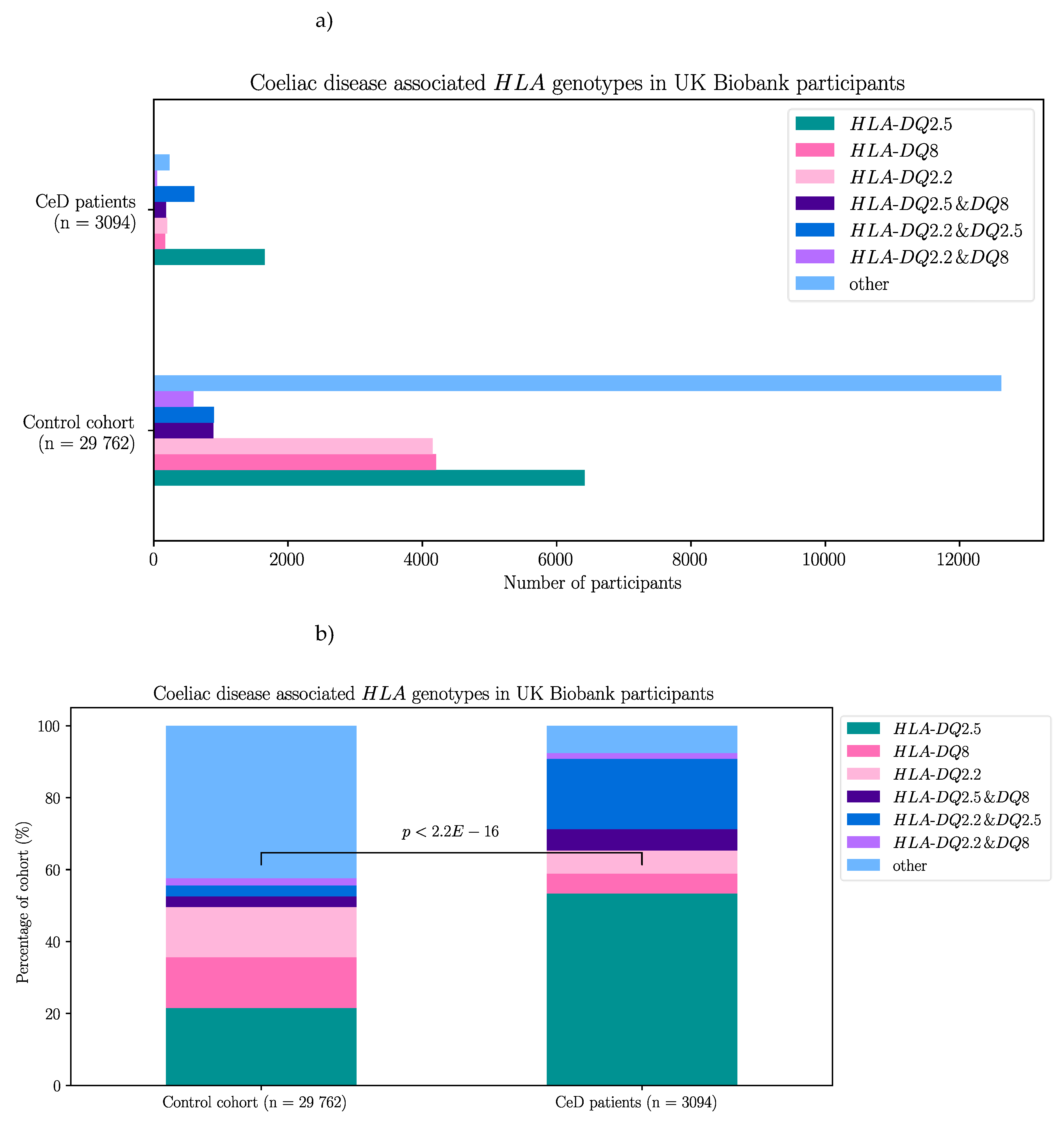

2.2.1. Risk Associated HLA Genotypes Were Significantly More frequent In CeD Patients of the UK Biobank

First, as a means of quality control for CeD diagnosis, the HLA genotypes of the CeD and control participants of the UK Biobank were examined. The majority of participants selected from the 500,000 genome-wide genotyping dataset had CeD risk HLA genotypes regardless of their CeD status (Table 6, Figure C1). Risk HLA genotypes were found in 92.4% (2860/3094) of CeD patients and 57.6% (17 144/29 762) of controls. In both control and CeD participants, HLA-DQ2.5 was the most frequent HLA genotype at 21.6% (6416/29 762) and 53.4% (1652/3094) respectively. Interestingly, HLA-DQ8 was the second most frequent risk genotype in controls at 14.1% (4203/29 762). Meanwhile individuals heterozygous for HLA-DQ2.5/HLA-DQ8 were the second most frequent in the CeD group, with 19.6% (606/3094) of participants possessing that risk HLA genotype.

Table 6.

CeD associated HLA genotypes were found in 92.4% of CeD (n = 3094) and 57.6% of control (n = 29 762) participants from the UK Biobank’s 500,000 genome-wide genotyping dataset. The HLA genotype of selected participants from the 500,000 genome-wide genotyping dataset were called using the HLA imputation values provided by the UK Biobank. CeD risk HLA genotypes were significantly more frequent in CeD patients compared to control participants (X-squared = 4062.5, df = 6, p < 2.2E-16).

Table 6.

CeD associated HLA genotypes were found in 92.4% of CeD (n = 3094) and 57.6% of control (n = 29 762) participants from the UK Biobank’s 500,000 genome-wide genotyping dataset. The HLA genotype of selected participants from the 500,000 genome-wide genotyping dataset were called using the HLA imputation values provided by the UK Biobank. CeD risk HLA genotypes were significantly more frequent in CeD patients compared to control participants (X-squared = 4062.5, df = 6, p < 2.2E-16).

|

HLA genotypes

|

HLA-DQ2.5 |

HLA-DQ8 |

HLA-DQ2.2 |

HLA-DQ2.5 & DQ8 |

HLA-DQ2.5 & DQ2.2 |

HLA-DQ8 & DQ2.2 |

Other |

| CeD participants |

1652 |

171 |

199 |

606 |

182 |

50 |

234 |

| Control participants |

6416 |

4203 |

4154 |

895 |

886 |

590 |

12618 |

To compare the proportion of CeD risk associated HLA genotypes in CeD and control participants in the 500,000 genome-wide genotyping dataset, a chi-square test of independence was used. Similar to the results from the targeted butyrophilin and HLA sequencing dataset, the CeD participants had significantly higher proportions of CeD risk HLA genotypes compared with controls (X-squared = 4062.5, df = 6, p < 2.2E-16).

Indeed, when the association between the CeD risk HLA genotypes and CeD status was investigated using a binomial regression model in the UK Biobank dataset, the association between the risk HLA genotypes and CeD status was confirmed. Interestingly in the regression analysis, all risk HLA genotypes were significantly associated with CeD (p ≤ 5.13E-04, Table C1) except the HLA-DQ8 genotype (p = 0.125).

2.2.2. BTN2A1, BTN3A1, and BTN3A2 SNPs Were Significantly Associated with CeD Status in the UK Biobank

Single variant analyses were carried out to test the association between CeD status and SNPs from the

BTN3A1, BTN3A2, BTNL3, and

BTNL8 genes in the UK Biobank [

58]. Due to the genotyping array used by the UK Biobank, the genetic information of only a limited number of SNPs from each gene was available. A total of 101 butyrophilin SNPs were selected for analysis (Table 7). As the

HLA loci were significantly associated with CeD risk [

1], and the

BTN3A1 and

BTN3A2 loci are in close proximity [

22,

24], the CeD risk

HLA genotypes were also taken into account for the single variant analyses by including the risk

HLA genotypes in the binomial models, and analysing the association between butyrophilin SNPs and CeD status in HLA-matched case-control groups as well. The genetic associations were tested by building binomial regression models, where the association between each variable and CeD status was examined.

Table 7.

SNPs of selected butyrophilin genes present in the UK Biobank.

Table 7.

SNPs of selected butyrophilin genes present in the UK Biobank.

| Gene |

SNPs in NCBI |

Unique SNPs in NCBI |

SNPs in UK Biobank |

| BTN2A1 |

7912 |

7605 |

30 |

| BTN3A1 |

5348 |

5164 |

27 |

| BTN3A2 |

5905 |

5611 |

21 |

| BTNL3 |

6164 |

5929 |

10 |

| BTNL8 |

18 889 |

18 197 |

13 |

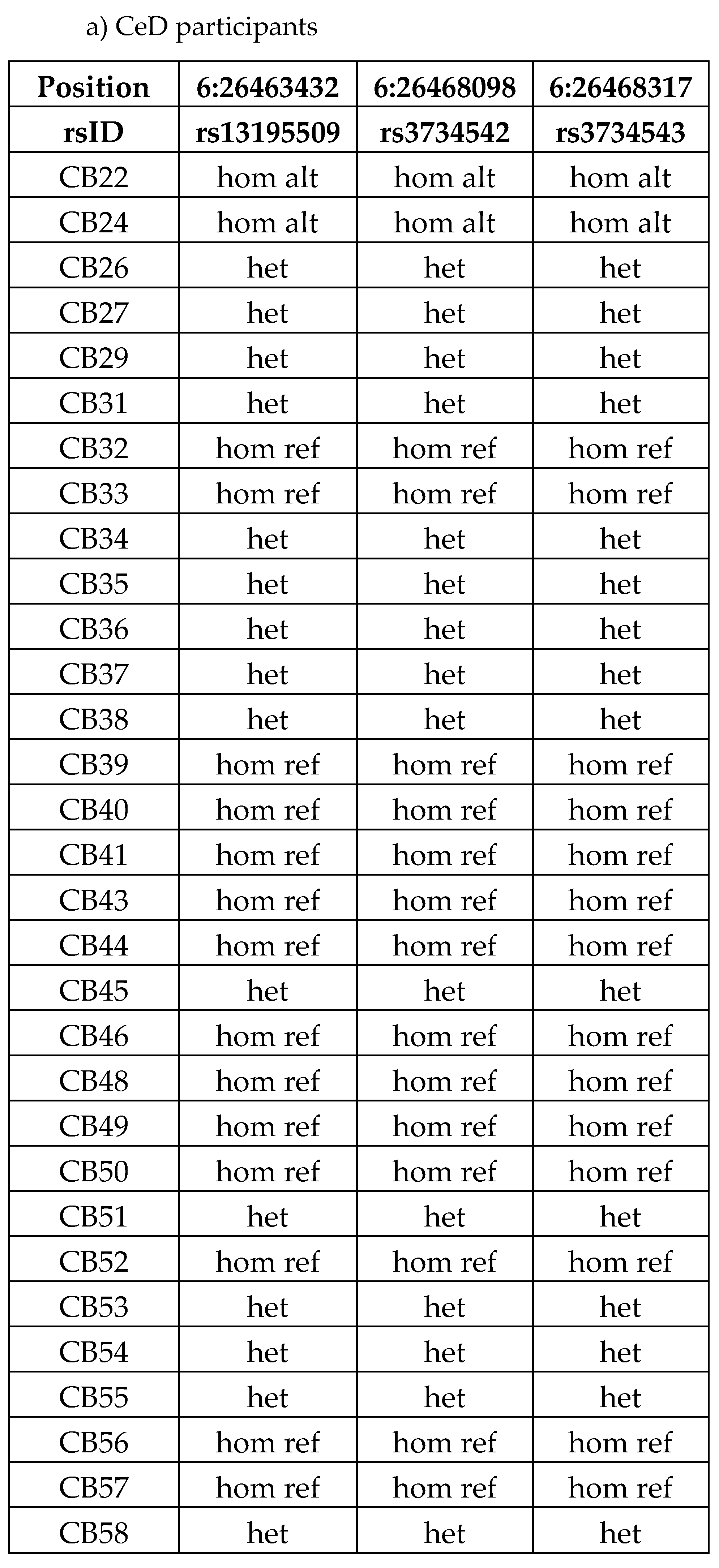

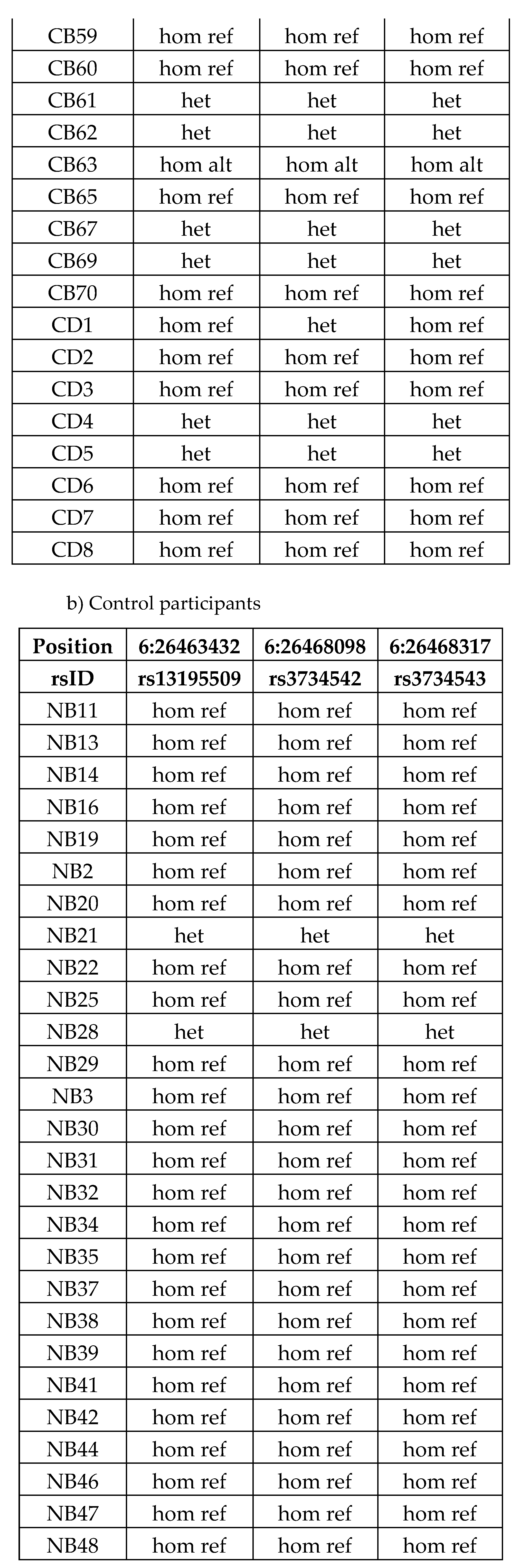

Each of the 101 selected SNPs were individually tested for association with CeD status in the UK Biobank. Thirty-seven SNPs were significantly associated with CeD status in the UK Biobank: 14 BTN2A1, 10 BTN3A1, and 13 BTN3A2 SNPs (adjusted p-value ≤ 0.05, Table 8, Table C2-C3). Most of the significant SNPs were non-coding, with 25 of the 37 SNPs being located in intronic regions. Only one BTN3A1 (rs41266839), and 3 BTN2A1 (rs13195509, rs3734542, rs3734543) SNPs were missense variants and one BTN2A1 (rs13195402) SNP encoded a STOP codon. Of the 37 SNPs, the reference alleles of 30 SNPs were associated with a decreased CeD risk. No BTNL3 nor BTNL8 SNPs were significant in predicting CeD status in the UK Biobank dataset, after Bonferroni correction.

Table 8.

SNPs from BTN2A1, BTN3A1, and BTN3A2 genes were significantly associated with CeD status in the UK Biobank. The name of the SNPs in the UK Biobank database is a combination of the reference SNP ID (rsID) from the SNP database (dbSNP) and the reference allele. All BTN2A1, BTN3A1, BTN3A2, BTNL3, and BTNL8 SNPs in the UK Biobank were subjected to single variant testing to examine their association with CeD. Due to multiple testing, Bonferroni correction was applied. SNPs with a negative ln(OR) are associated with lower CeD risk in this binomial model, meaning that the reference allele is less frequent in CeD patients. SNPs in bold remained significantly associated with CeD in the binomial regression models that also took the HLA genotype into account. SNP count and allele count data for the significant SNPs is found in Table C3.

Table 8.

SNPs from BTN2A1, BTN3A1, and BTN3A2 genes were significantly associated with CeD status in the UK Biobank. The name of the SNPs in the UK Biobank database is a combination of the reference SNP ID (rsID) from the SNP database (dbSNP) and the reference allele. All BTN2A1, BTN3A1, BTN3A2, BTNL3, and BTNL8 SNPs in the UK Biobank were subjected to single variant testing to examine their association with CeD. Due to multiple testing, Bonferroni correction was applied. SNPs with a negative ln(OR) are associated with lower CeD risk in this binomial model, meaning that the reference allele is less frequent in CeD patients. SNPs in bold remained significantly associated with CeD in the binomial regression models that also took the HLA genotype into account. SNP count and allele count data for the significant SNPs is found in Table C3.

| Position (GRCh38) |

SNP, reference allele |

Gene |

SNP consequence |

CeD allele freq |

Control allele freq |

Total allele freq |

ln(OR) |

CeD risk |

adjusted p-value |

| 6:26463347 |

rs13195402 |

BTN2A1 |

STOP gained |

0.768 |

0.892 |

0.880 |

-0.924 |

decrease |

4.67E-158 |

| 6:26463432 |

rs13195509 |

BTN2A1 |

missense |

0.754 |

0.879 |

0.867 |

-0.857 |

decrease |

1.61E-151 |

| 6:26475927 |

rs1407045 |

BTN2A1 |

intronic |

0.584 |

0.516 |

0.522 |

0.273 |

increase |

6.07E-22 |

| 6:26465807 |

rs2273558 |

BTN2A1 |

intronic |

0.583 |

0.677 |

0.667 |

-0.396 |

decrease |

1.69E-41 |

| 6:26460493 |

rs2893856 |

BTN2A1 |

intronic |

0.113 |

0.131 |

0.130 |

-0.175 |

decrease |

3.23E-03 |

| 6:26468098 |

rs3734542 |

BTN2A1 |

missense |

0.753 |

0.878 |

0.867 |

-0.855 |

decrease |

8.59E-151 |

| 6:26468317 |

rs3734543 |

BTN2A1 |

missense |

0.760 |

0.879 |

0.868 |

-0.844 |

decrease |

1.59E-140 |

| 6:26466954 |

rs3799380 |

BTN2A1 |

intronic |

0.683 |

0.790 |

0.780 |

-0.549 |

decrease |

8.59E-77 |

| 6:26474343 |

rs56296968 |

BTN2A1 |

intronic |

0.696 |

0.807 |

0.796 |

-0.604 |

decrease |

9.70E-89 |

| 6:26456215 |

rs6456724 |

BTN2A1 |

2kb upstream |

0.113 |

0.131 |

0.130 |

-0.176 |

decrease |

2.87E-03 |

| 6:26458037 |

rs6929846 |

BTN2A1 |

5’ UTR |

0.146 |

0.174 |

0.172 |

-0.206 |

decrease |

3.60E-06 |

| 6:26473816 |

rs7773938 |

BTN2A1 |

intronic |

0.696 |

0.806 |

0.796 |

-0.600 |

decrease |

1.15E-87 |

| 6:26469647 |

rs9358944 |

BTN2A1 |

intronic |

0.695 |

0.806 |

0.796 |

-0.604 |

decrease |

1.55E-89 |

| 6:26471886 |

rs9358945 |

BTN2A1 |

intronic |

0.694 |

0.806 |

0.796 |

-0.606 |

decrease |

4.37E-90 |

| 6:26404730 |

rs10456045 |

BTN3A1 |

intronic |

0.596 |

0.698 |

0.688 |

-0.448 |

decrease |

2.97E-57 |

| 6:26410572 |

rs1796520 |

BTN3A1 |

intronic |

0.405 |

0.474 |

0.467 |

-0.276 |

decrease |

2.40E-22 |

| 6:26404146 |

rs3799378 |

BTN3A1 |

intronic |

0.653 |

0.762 |

0.752 |

-0.535 |

decrease |

2.92E-75 |

| 6:26405825 |

rs3857549 |

BTN3A1 |

intronic |

0.948 |

0.935 |

0.936 |

0.221 |

increase |

1.53E-02 |

| 6:26409662 |

rs41266839 |

BTN3A1 |

missense |

0.764 |

0.892 |

0.880 |

-0.924 |

decrease |

2.12E-168 |

| 6:26407180 |

rs4609015 |

BTN3A1 |

intronic |

0.871 |

0.854 |

0.855 |

0.141 |

increase |

3.82E-02 |

| 6:26412860 |

rs6900725 |

BTN3A1 |

intronic |

0.870 |

0.853 |

0.855 |

0.139 |

increase |

4.33E-02 |

| 6:26401210 |

rs6912853 |

BTN3A1 |

2kb upstream |

0.863 |

0.844 |

0.846 |

0.153 |

increase |

7.85E-03 |

| 6:26413007 |

rs6920986 |

BTN3A1 |

intronic |

0.870 |

0.854 |

0.856 |

0.138 |

increase |

4.99E-02 |

| 6:26415409 |

rs742090 |

BTN3A1 |

500b downstream |

0.406 |

0.474 |

0.468 |

-0.276 |

decrease |

3.58E-22 |

| 6:26374321 |

rs11758089 |

BTN3A2 |

intronic |

0.866 |

0.844 |

0.846 |

0.176 |

increase |

6.30E-04 |

| 6:26372558 |

rs12176317 |

BTN3A2 |

intronic |

0.744 |

0.867 |

0.856 |

-0.809 |

decrease |

6.72E-140 |

| 6:26366990 |

rs12199613 |

BTN3A2 |

intronic |

0.514 |

0.612 |

0.602 |

-0.400 |

decrease |

1.76E-47 |

| 6:26377318 |

rs1977 |

BTN3A2 |

3’ UTR |

0.740 |

0.864 |

0.853 |

-0.808 |

decrease |

1.17E-136 |

| 6:26377363 |

rs1979 |

BTN3A2 |

3’ UTR |

0.743 |

0.867 |

0.855 |

-0.809 |

decrease |

8.23E-140 |

| 6:26375933 |

rs1985732 |

BTN3A2 |

intronic |

0.595 |

0.698 |

0.688 |

-0.457 |

decrease |

2.87E-59 |

| 6:26374430 |

rs2073526 |

BTN3A2 |

intronic |

0.370 |

0.442 |

0.435 |

-0.295 |

decrease |

9.15E-25 |

| 6:26363527 |

rs9358934 |

BTN3A2 |

2kb upstream |

0.744 |

0.866 |

0.855 |

-0.803 |

decrease |

2.34E-137 |

| 6:26364702 |

rs9379855 |

BTN3A2 |

2kb upstream |

0.743 |

0.866 |

0.855 |

-0.804 |

decrease |

8.85E-138 |

| 6:26367461 |

rs9379858 |

BTN3A2 |

intronic |

0.743 |

0.866 |

0.855 |

-0.802 |

decrease |

3.19E-137 |

| 6:26369321 |

rs9379859 |

BTN3A2 |

intronic |

0.744 |

0.867 |

0.855 |

-0.803 |

decrease |

5.37E-137 |

| 6:26373450 |

rs9393713 |

BTN3A2 |

intronic |

0.743 |

0.868 |

0.856 |

-0.814 |

decrease |

1.07E-141 |

| 6:26373512 |

rs9393714 |

BTN3A2 |

intronic |

0.743 |

0.868 |

0.856 |

-0.813 |

decrease |

6.99E-141 |

2.2.3. Twenty Butyrophilin SNPs from the UK Biobank Remained Significantly Associated with CeD Status When the Participants’ risk HLA Genotypes Were Taken into Account

To investigate whether the butyrophilin SNPs in the UK Biobank remained significantly associated with CeD status when taking the HLA loci into account, a second set of binomial regression models was produced. Single variant models were built for each of the 101 SNPs of interest, that included the risk HLA genotypes of the UK Biobank participants as an additional predictor variable (Table C4). Only 7 BTN2A1, 2 BTN3A1, and 11 BTN3A2 SNPs remained significantly associated with CeD status after applying Bonferroni correction (adjusted p ≤ 0.05, Table 9). Similarly to the previous model, the majority of the significant SNPs were non-coding with the exception of a STOP gained SNP (rs13195402) and 3 missense SNPs (rs13195509, rs3734542, rs3734543) in the BTN2A1 gene. Out of the 17 non-coding SNPs, 11 SNPs were located in intronic regions. The reference alleles for all 20 SNPs were associated with a decreased CeD risk, meaning that the alternate alleles were more frequent in CeD patients. As the HLA loci were taken into account, these SNPs are likely to be real associations with CeD status, instead of being caused by linkage disequilibrium (LD) due to the proximity of the BTN and HLA loci on chromosome 6.

Table 9.

Twenty SNPs from BTN2A1, BTN3A1, and BTN3A2 genes were significantly associated with CeD status in the UK Biobank when HLA genotypes were included in the single variant testing models. BTN2A1, BTN3A2, BTNL3, and BTNL8 SNPs in the UK Biobank were subjected to single variant testing to examine their association with CeD. Due to multiple testing, Bonferroni correction was applied. SNPs with a negative ln(OR) are associated with lower CeD risk in this binomial model.

Table 9.

Twenty SNPs from BTN2A1, BTN3A1, and BTN3A2 genes were significantly associated with CeD status in the UK Biobank when HLA genotypes were included in the single variant testing models. BTN2A1, BTN3A2, BTNL3, and BTNL8 SNPs in the UK Biobank were subjected to single variant testing to examine their association with CeD. Due to multiple testing, Bonferroni correction was applied. SNPs with a negative ln(OR) are associated with lower CeD risk in this binomial model.

| SNP, reference allele |

Gene |

SNP consequence |

ln(OR) |

CeD risk |

adjusted p-value |

| rs13195402 |

BTN2A1 |

STOP gained |

-0.20727 |

decrease |

8.15E-06 |

| rs13195509 |

BTN2A1 |

missense |

-0.19239 |

decrease |

1.62E-05 |

| rs3734542 |

BTN2A1 |

missense |

-0.18831 |

decrease |

2.94E-05 |

| rs3734543 |

BTN2A1 |

missense |

-0.16744 |

decrease |

8.23E-04 |

| rs56296968 |

BTN2A1 |

intronic |

-0.11753 |

decrease |

4.20E-02 |

| rs9358944 |

BTN2A1 |

intronic |

-0.11786 |

decrease |

3.83E-02 |

| rs9358945 |

BTN2A1 |

intronic |

-0.12018 |

decrease |

2.91E-02 |

| rs3799378 |

BTN3A1 |

intronic |

-0.14327 |

decrease |

7.04E-04 |

| rs41266839 |

BTN3A1 |

missense |

-0.21469 |

decrease |

1.06E-06 |

| rs12176317 |

BTN3A2 |

intronic |

-0.1974 |

decrease |

3.50E-06 |

| rs12199613 |

BTN3A2 |

intronic |

-0.12296 |

decrease |

3.31E-03 |

| rs1977 |

BTN3A2 |

3’ UTR |

-0.20238 |

decrease |

2.06E-06 |

| rs1979 |

BTN3A2 |

3’ UTR |

-0.19756 |

decrease |

3.40E-06 |

| rs1985732 |

BTN3A2 |

intronic |

-0.10975 |

decrease |

3.35E-02 |

| rs9358934 |

BTN3A2 |

2kb upstream |

-0.19286 |

decrease |

7.53E-06 |

| rs9379855 |

BTN3A2 |

2kb upstream |

-0.19406 |

decrease |

6.04E-06 |

| rs9379858 |

BTN3A2 |

intronic |

-0.19156 |

decrease |

8.99E-06 |

| rs9379859 |

BTN3A2 |

intronic |

-0.19261 |

decrease |

8.10E-06 |

| rs9393713 |

BTN3A2 |

intronic |

-0.2056 |

decrease |

9.27E-07 |

| rs9393714 |

BTN3A2 |

intronic |

-0.20087 |

decrease |

2.08E-06 |

2.2.4. Twenty-One Butyrophilin SNPs Were Significantly Associated with CeD Status in HLA-DQ2.5-Matched Case-Control Groups of UK Biobank Participants

The final set of analyses were carried out to investigate whether the butyrophilin SNPs were significantly associated with CeD status in all of the CeD risk HLA genotype patients. Therefore, the UK Biobank participants were separated into risk HLA-matched CeD and control groups (Table 10). All 101 butyrophilin SNPs were single variant tested for their association to CeD status in the HLA-matched groups.

Table 10.

Single variant testing in HLA-matched groups from the UK Biobank dataset only identified significant SNPs associated with CeD status in individuals with HLA-DQ2.5 genotypes. The CeD and control participants of the UK Biobank dataset were divided into HLA-matched case-control groups for single variant testing. The association between BTN2A1, BTN3A1, BTN3A2, BTNL3, and BTNL8 SNPs and CeD status was investigated. Significant association between the SNPs and CeD status was only present in HLA-DQ2.5-matched individuals (in bold).

Table 10.

Single variant testing in HLA-matched groups from the UK Biobank dataset only identified significant SNPs associated with CeD status in individuals with HLA-DQ2.5 genotypes. The CeD and control participants of the UK Biobank dataset were divided into HLA-matched case-control groups for single variant testing. The association between BTN2A1, BTN3A1, BTN3A2, BTNL3, and BTNL8 SNPs and CeD status was investigated. Significant association between the SNPs and CeD status was only present in HLA-DQ2.5-matched individuals (in bold).

|

HLA genotype of individuals in model

|

Number of CeD participants |

Number of controls |

Number of significant SNPs |

| HLA-DQ2.2 |

199 |

4154 |

0 |

| HLA-DQ2.5 |

1652 |

6416 |

21 |

| HLA-DQ8 |

171 |

4203 |

0 |

| HLA-DQ2.2, HLA-DQ2.5 |

606 |

895 |

0 |

| HLA-DQ2.2, HLA-DQ8 |

50 |

590 |

0 |

| HLA-DQ2.5, HLA-DQ8 |

182 |

886 |

0 |

| Other |

234 |

12618 |

0 |

HLA-DQ2.5 was the most common risk

HLA genotype in CeD patients both in the UK Biobank, as well as in previous studies [

11,

12]. Interestingly, significant association between butyrophilin SNPs and CeD status was only present in the

HLA-DQ2.5-matched UK Biobank participants. The

BTN2A1,

BTN3A1, and

BTN3A2 SNPs significantly associated with CeD status in the

HLA single variant testing models remained significant in the

HLA-DQ2.5-matched tests as well (Table 11, Table C5). Interestingly, rs7773938, an intronic

BTN2A1 SNP, is a novel SNP that was only significantly associated with CeD status in UK Biobank participants with the

HLA-DQ2.5 genotype. The reference alleles of all 21 significant SNPs were more frequent in controls compared to CeD individuals, meaning that having the alternate allele at these loci significantly increases an individual’s CeD risk. These results imply that butyrophilin SNPs could only explain additional CeD risk in HLA-DQ2.5-matched individuals of the UK Biobank. As the presence of these reference alleles remained significantly associated with decreased CeD risk even after

HLA-matching, the association with these SNPs was not likely to be caused by LD to the

HLA loci. Therefore, the 21 butyrophilin SNPs identified were significantly associated with CeD status and contributed to further CeD risk in UK Biobank participants possessing the

HLA-DQ2.5 genotype.

Table 11.

Butyrophilin SNPs only remained significantly associated with CeD status in the HLA-DQ2.5 restricted UK Biobank analysis. The name of the SNPs in the UK Biobank database are a combination of the SNP name and the reference allele. All BTN2A1, BTN3A1, BTN3A2, BTNL3, and BTNL8 SNPs in the UK Biobank were subjected to single variant testing to examine their association with CeD. Due to multiple testing, Bonferroni correction was applied. SNPs with a negative ln(OR) are associated with lower CeD risk in this binomial model. The SNP in bold was a novel SNP significantly associated with CeD unique to the HLA-DQ2.5 model, while the other SNPs were also significant in the non-HLA and the HLA models.

Table 11.

Butyrophilin SNPs only remained significantly associated with CeD status in the HLA-DQ2.5 restricted UK Biobank analysis. The name of the SNPs in the UK Biobank database are a combination of the SNP name and the reference allele. All BTN2A1, BTN3A1, BTN3A2, BTNL3, and BTNL8 SNPs in the UK Biobank were subjected to single variant testing to examine their association with CeD. Due to multiple testing, Bonferroni correction was applied. SNPs with a negative ln(OR) are associated with lower CeD risk in this binomial model. The SNP in bold was a novel SNP significantly associated with CeD unique to the HLA-DQ2.5 model, while the other SNPs were also significant in the non-HLA and the HLA models.

| SNP, reference allele |

Gene |

SNP consequence |

CeD allele freq |

Control allele freq |

Total allele freq |

ln(OR) |

CeD risk |

adjusted p-value |

| rs13195402 |

BTN2A1 |

STOP gained |

0.704 |

0.751 |

0.741 |

-0.27812 |

decrease |

5.10E-07 |

| rs13195509 |

BTN2A1 |

missense |

0.687 |

0.734 |

0.724 |

-0.25542 |

decrease |

1.75E-06 |

| rs3734542 |

BTN2A1 |

missense |

0.687 |

0.733 |

0.723 |

-0.25235 |

decrease |

2.52E-06 |

| rs3734543 |

BTN2A1 |

missense |

0.695 |

0.736 |

0.728 |

-0.23279 |

decrease |

5.43E-05 |

| rs56296968 |

BTN2A1 |

intronic |

0.640 |

0.673 |

0.666 |

-0.15928 |

decrease |

2.33E-02 |

| rs7773938 |

BTN2A1 |

intronic |

0.640 |

0.672 |

0.666 |

-0.15755 |

decrease |

2.66E-02 |

| rs9358944 |

BTN2A1 |

intronic |

0.638 |

0.671 |

0.664 |

-0.16238 |

decrease |

1.61E-02 |

| rs9358945 |

BTN2A1 |

intronic |

0.638 |

0.671 |

0.665 |

-0.16499 |

decrease |

1.26E-02 |

| rs3799378 |

BTN3A1 |

intronic |

0.596 |

0.637 |

0.628 |

-0.18712 |

decrease |

8.10E-04 |

| rs41266839 |

BTN3A1 |

missense |

0.697 |

0.747 |

0.737 |

-0.28267 |

decrease |

7.25E-08 |

| rs12176317 |

BTN3A2 |

intronic |

0.679 |

0.729 |

0.719 |

-0.26575 |

decrease |

2.82E-07 |

| rs12199613 |

BTN3A2 |

intronic |

0.459 |

0.500 |

0.491 |

-0.1717 |

decrease |

2.06E-03 |

| rs1977 |

BTN3A2 |

3’ UTR |

0.676 |

0.726 |

0.716 |

-0.268 |

decrease |

2.99E-07 |

| rs1979 |

BTN3A2 |

3’ UTR |

0.679 |

0.728 |

0.718 |

-0.26376 |

decrease |

3.63E-07 |

| rs1985732 |

BTN3A2 |

intronic |

0.539 |

0.574 |

0.567 |

-0.15063 |

decrease |

2.35E-02 |

| rs9358934 |

BTN3A2 |

2kb upstream |

0.680 |

0.729 |

0.719 |

-0.25825 |

decrease |

8.85E-07 |

| rs9379855 |

BTN3A2 |

2kb upstream |

0.680 |

0.728 |

0.718 |

-0.25967 |

decrease |

6.76E-07 |

| rs9379858 |

BTN3A2 |

intronic |

0.680 |

0.728 |

0.718 |

-0.25566 |

decrease |

1.18E-06 |

| rs9379859 |

BTN3A2 |

intronic |

0.681 |

0.729 |

0.719 |

-0.26105 |

decrease |

6.31E-07 |

| rs9393713 |

BTN3A2 |

intronic |

0.678 |

0.729 |

0.719 |

-0.27313 |

decrease |

1.06E-07 |

| rs9393714 |

BTN3A2 |

intronic |

0.679 |

0.729 |

0.719 |

-0.26778 |

decrease |

2.25E-07 |

2.3. HV4 Variation was Not Significantly Associated with CeD Risk in a Study of 379 Samples

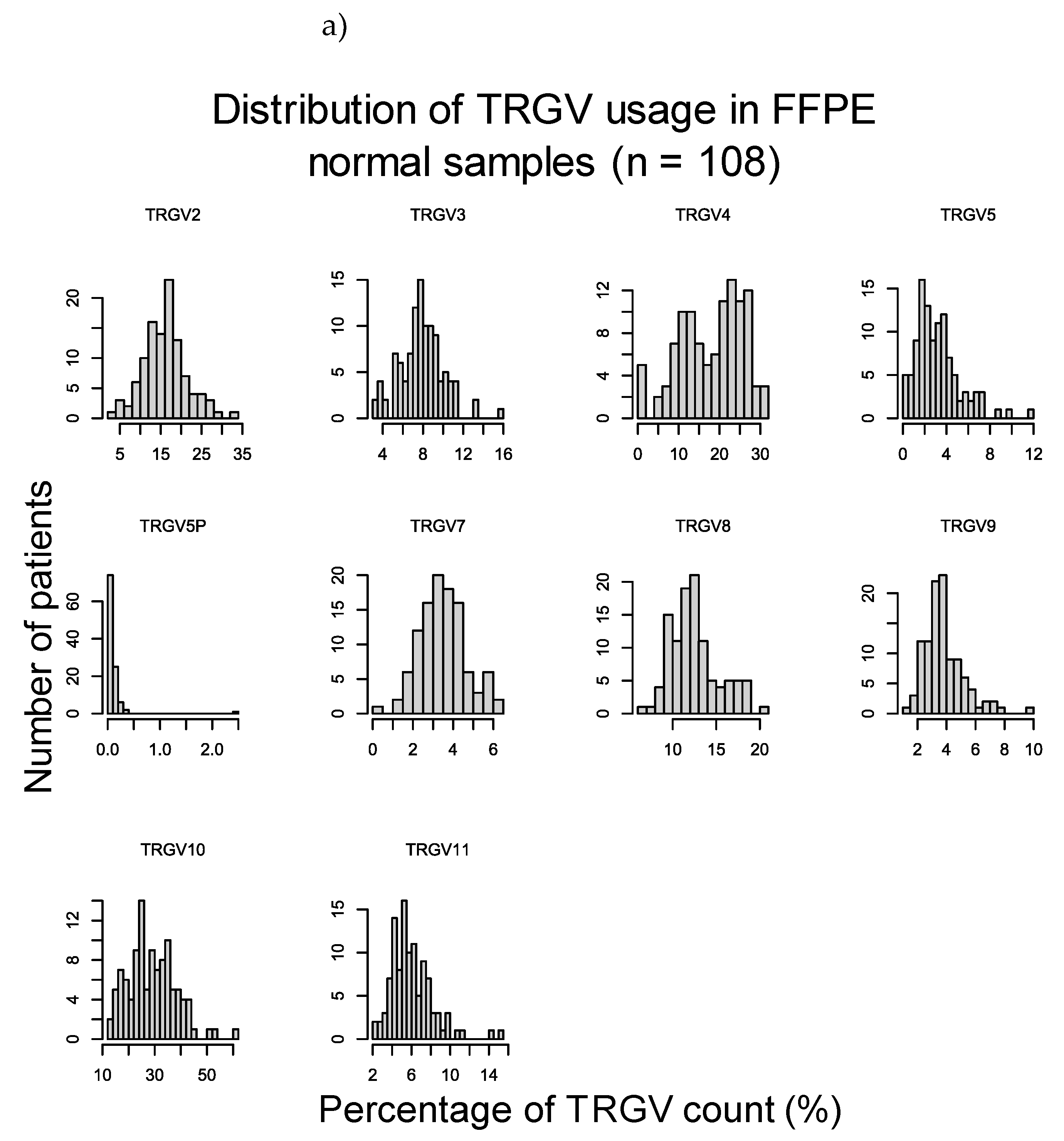

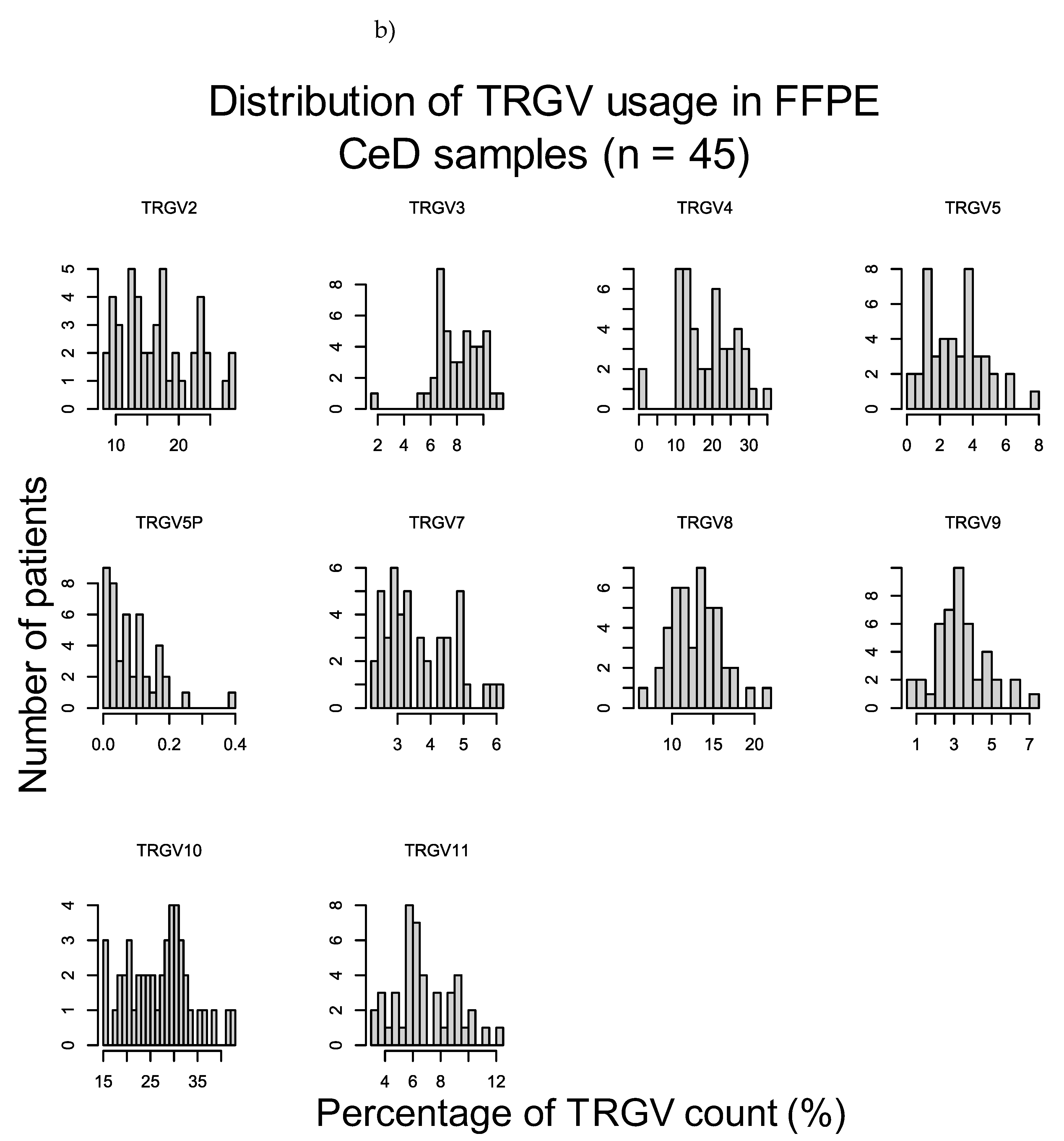

2.3.1. TRGV Usage Was not Significantly Different Between CeD and Control Samples

Previous evidence by our group showed that the γδ T-cell repertoire is permanently altered in the duodenum of CeD patients [

59]. Mayassi

, et al. [

21] also showed that the

TRGV4 transcripts are lost and the γδ TCR repertoire is permanently reconfigured in the duodenum after active CeD.

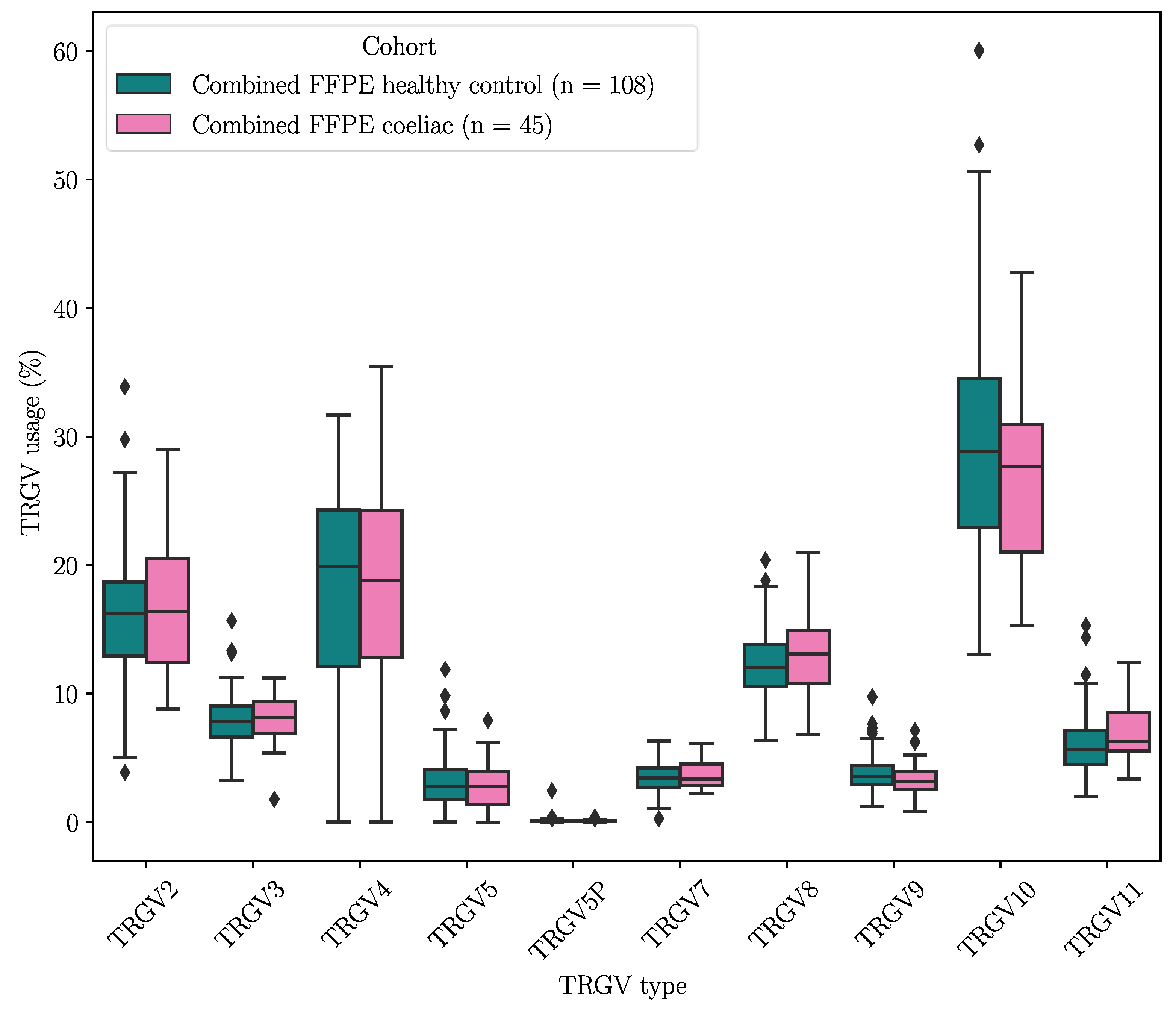

To verify these results, the duodenal TRG repertoires of 108 healthy controls and 45 CeD patients were examined for potential differences in TRGV usage, which was defined as the proportion of TRGV segment read counts present within the TCR repertoire of a tissue sample, using data derived from DNA extracted from formalin fixed, paraffin embedded (FFPE) duodenal samples and sequenced using the TRG Lymphotrack kit (Invivoscribe, Inc.) and a MiSeq platform (Illumina Inc.) (Table 14). The proportions of the TRGV genes present in duodenum samples from neither healthy controls nor CeD patients showed a normal distribution (Figure D1). The TRGV10, TRGV4, and TRGV2 variable (V) gene segments were the most frequent in this dataset. The mean usage proportion of the TRGV4 segment, which is capable of binding the BTNL3/BTNL8 heterodimer was 18.50% and 18.06% of the TRG repertoire in CeD and healthy control samples, respectively. When the proportion of TRGV segments was compared between the combined CeD and healthy control samples, no significant differences were found (Figure 2, Table D1).

Figure 2.

There were no significant differences in the TRGV usage of CeD (n = 45) and healthy control (n = 108) duodenal samples.

Figure 2.

There were no significant differences in the TRGV usage of CeD (n = 45) and healthy control (n = 108) duodenal samples.

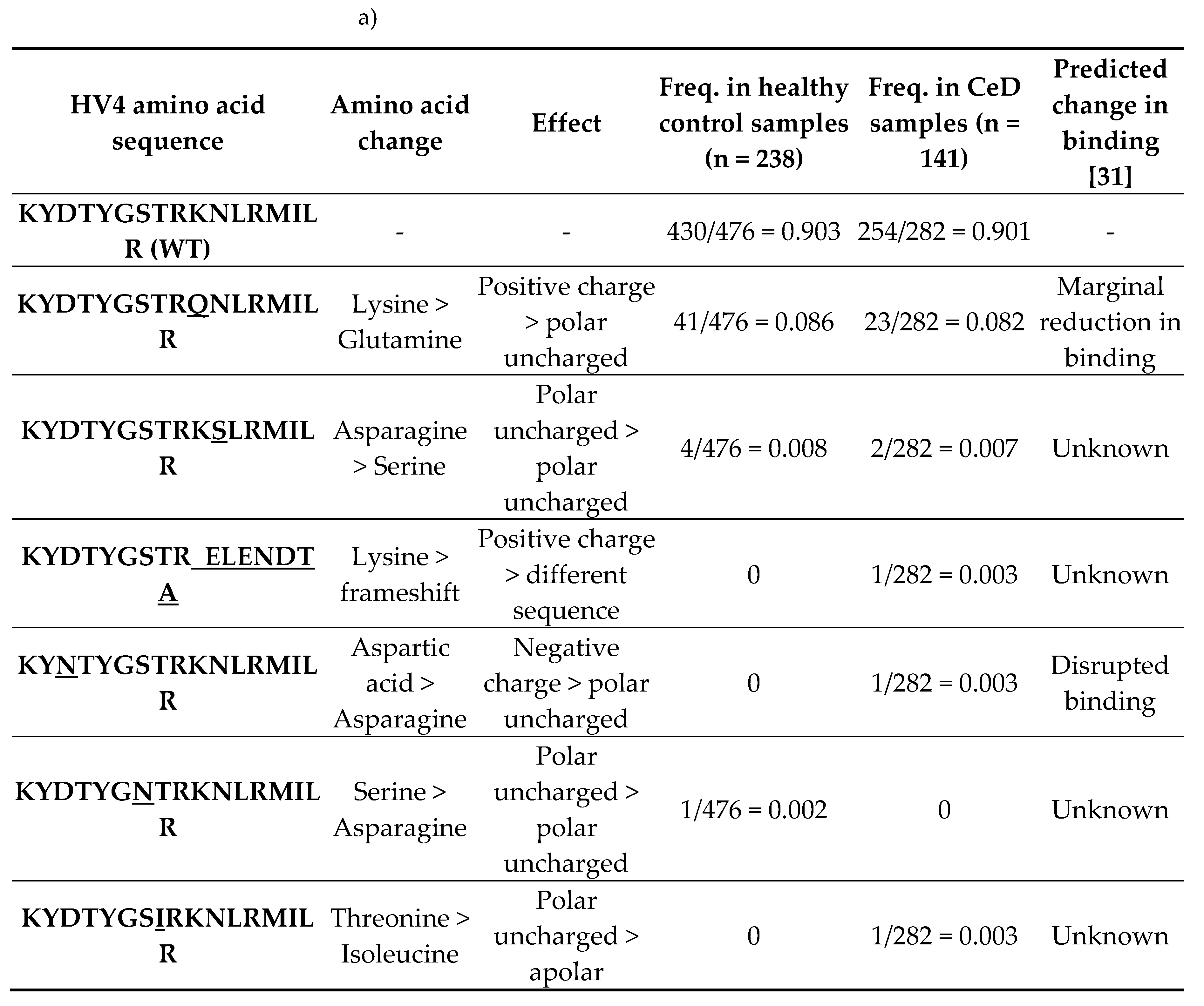

2.3.2. HV4 Sequence Variation Was not Significantly Associated with CeD Risk

Next, the TRGV4-HV4 amino acid sequences were examined in 141 CeD and 238 healthy control samples (Table 14). The

HV4 is germline-encoded, and is located in the

FR3 of the

TRGV4 gene. Neither the

FR3 nor the

HV4 undergo somatic recombination in T cells. As demonstrated by Melandri

, et al. [

29] and Willcox

, et al. [

31], only HV4 loops with the wild type (reference) KYDTYGSTRKNLRMILR amino acid sequence could directly bind BTNL3. Substitutions in the amino acids underlined (KY

DTY

GSTRKNLRMILR) were found to disrupt this direct binding between BTNL3 and Vγ4+ T cells, while substitutions in the following underlined amino acids (KYDTYGSTR

KNLR

MILR) only caused a marginal reduction in binding [

31]. As the HV4 is germline-encoded and does not undergo recombination, we hypothesised that variations in the germline-encoded TRGV4-HV4 amino acid sequence could alter the binding of the Vγ4+ γδ T cells to BTNL3 protein in the duodenum, predisposing to CeD.

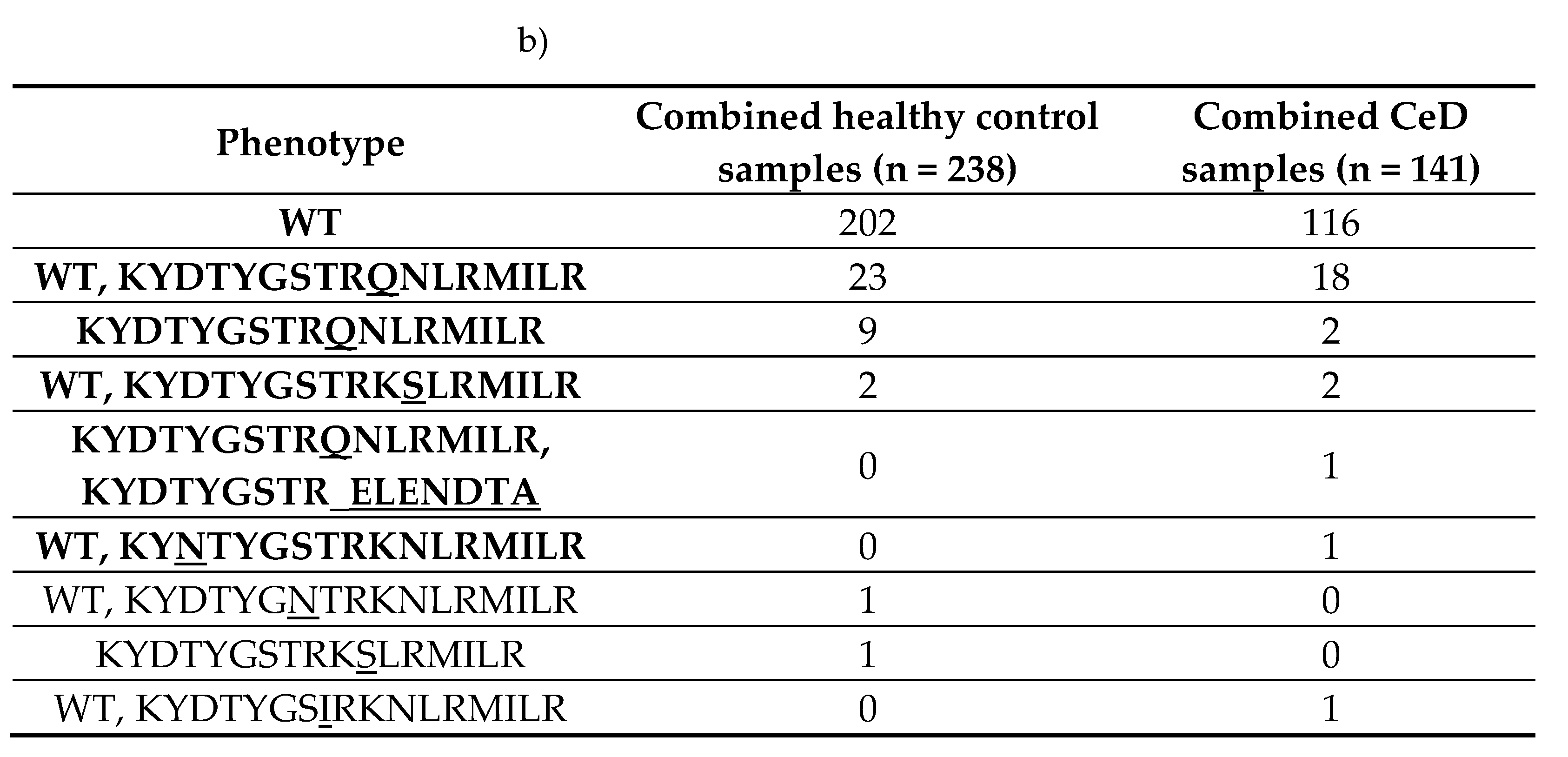

Seven unique HV4 amino acid sequences were identified in the dataset (Table 12). The reference HV4 sequence KYDTYGSTRKNLRMILR capable of binding the BTNL3 protein was the most frequent in both healthy control (95.8%, 228/238) and CeD (97.9%, 138/141) samples. Approximately 84.9% (202/238) of healthy control samples and 82.3% (116/141) of CeD were homozygous for the WT HV4 sequence. There were no significant differences in the HV4 amino acid sequence distribution between CeD and healthy control samples (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.26, Figure 3, Table D2).

Table 12.

More than 95% of participants possessed at least one reference HV4 loop regardless of their CeD status. The dataset consisted of 238 healthy control and 141 CeD samples. a) Seven unique HV4 amino acid sequences were identified in the dataset. b) The homozygous WT HV4 phenotype was the most frequent in both healthy control and CeD groups.

Table 12.

More than 95% of participants possessed at least one reference HV4 loop regardless of their CeD status. The dataset consisted of 238 healthy control and 141 CeD samples. a) Seven unique HV4 amino acid sequences were identified in the dataset. b) The homozygous WT HV4 phenotype was the most frequent in both healthy control and CeD groups.

Figure 3.

More than 82% of both healthy control and CeD samples were homozygous for the reference HV4 amino acid sequence in the combined cohort. The HV4 analysis was carried out on a cohort of 238 healthy control and 141 CeD samples. The homozygous, reference HV4 sequence was the most common phenotype in both CeD and healthy control samples. Only 10 healthy control and 3 CeD samples did not have any WT HV4 sequences.

Figure 3.

More than 82% of both healthy control and CeD samples were homozygous for the reference HV4 amino acid sequence in the combined cohort. The HV4 analysis was carried out on a cohort of 238 healthy control and 141 CeD samples. The homozygous, reference HV4 sequence was the most common phenotype in both CeD and healthy control samples. Only 10 healthy control and 3 CeD samples did not have any WT HV4 sequences.

To summarise, TRGV usage and HV4 amino acid sequence variation could not explain CeD risk in a dataset of 379 samples.

3. Discussion

Coeliac disease (CeD) is a T-cell mediated enteropathy triggered by the consumption of gluten, which is the collective name of a group of proteins found in wheat, rye, and barley [

1]. The genetic risk for CeD is not fully understood; an estimated 50% of genetic predisposition is still unexplored [

60]. Around 30% of genetic risk can be explained by the

HLA risk genotypes

HLA-DQ2.5, HLA-DQ8, and

HLA-DQ2.2, which were first connected to CeD risk in 1972 [

17,

18,

61,

62].

Recently, the butyrophilin family of genes were proposed as non-

HLA CeD risk loci [

19,

20,

21]. These genes encode transmembrane proteins that were implicated in regulating the activity of innate and adaptive immune cells, alongside maintaining characteristic epithelial γδ T-cell populations in mice and humans [

22,

24]. Prior to this study, four genes were associated with CeD:

BTN3A1, BTNL2, BTNL3, and

BTNL8 [

19,

20,

21].

Therefore, we investigated the association of butyrophilin family gene variation to CeD risk via targeted sequencing of 46 healthy control and 49 CeD samples. The non-synonymous coding butyrophilin SNP data of the 94 samples were subjected to gene-based burden testing. Comparing the CeD and control SNPs, BTN2A1 gene burden was significantly higher in CeD patients in both the dominant (p = 1.46E-05) and the recessive models (p = 3.70E-08).

The significant association between BTN2A1 SNPs and CeD risk was validated using the UK Biobank 500,000 genome-wide genotyping dataset. Fourteen BTN2A1, 10 BTN3A1, and 13 BTN3A2 SNPs were significantly associated with CeD, the majority of which were non-coding variants. When the risk associated HLA genotypes of these participants were taken into account, only 7 BTN2A1, 2 BTN3A1, and 11 BTN3A2 SNPs remained significant, showing HLA independent associations with CeD risk. Finally, butyrophilin SNPs were single variant tested in CeD risk HLA-matched groups. The 20 SNPs above alongside a novel intronic BTN2A1 SNP were significant in predicting CeD status in 1652 CeD and 6416 control participants with the HLA-DQ2.5 genotype. UK Biobank validation indicated that the BTN3A1 and BTN3A2 non-synonymous coding SNPs were not significantly associated with CeD risk in the hybridization capture cohort, likely due to the majority of significantly associated SNPs being non-coding, and thus excluded from the burden testing analysis.

Due to the association between butyrophilin family members and CeD status, and the involvement of butyrophilin heterodimers in shaping γδ T-cell repertoires, CeD risk was also examined from the angle of the duodenal Vγ4+ γδ T cells [

21,

27,

28]. To investigate any likely effects of polymorphisms in the TCR γ V segment, TRGV4, on the interaction between Vγ4+ γδ T cells and the BTNL3/BTNL8 heterodimer, the TRGV4-HV4 amino acid sequences of 379 samples were examined. Mutations in the reference HV4 sequence, KY

DTY

GSTR

KNLR

MILR, specifically in the DGKM residues

in vitro were previously shown to decrease the direct binding between BTNL3 and Vγ4+ γδ T cells [

31]. The aim of this analysis was to identify germline-encoded HV4 amino acid sequence variations, that were more frequent in CeD patients. The hypothesis was that individuals having HV4 variations, especially ones that affected the DGKM residues, had higher CeD risk due to the decreased BTNL3-HV4 binding affinity. There were no significant differences in the HV4 amino acid sequence variation between CeD and healthy control samples (

p = 0.2648). It is possible that the HV4 sequence is conserved via stabilising selection due to its interaction with BTNL3, which serves as the maintenance signal for the Vγ4+ γδ T cells in the duodenum [

21].

We thus identified

BTN2A1 and

BTN3A2 as novel CeD risk loci and corroborated

BTN3A1 as a CeD risk locus. The association between

BTN3A1 and CeD is in accordance with evidence showed by Pietz

, et al. [

20], who hypothesised that pAg presentation by intestinal epithelial cells in active CeD may contribute to IFN-γ production and T cell proliferation. Indeed, all three of these butyrophilin genes are involved in the pAg-mediated, innate-like activation of peripheral blood γδ T cells [

37,

38,

63,

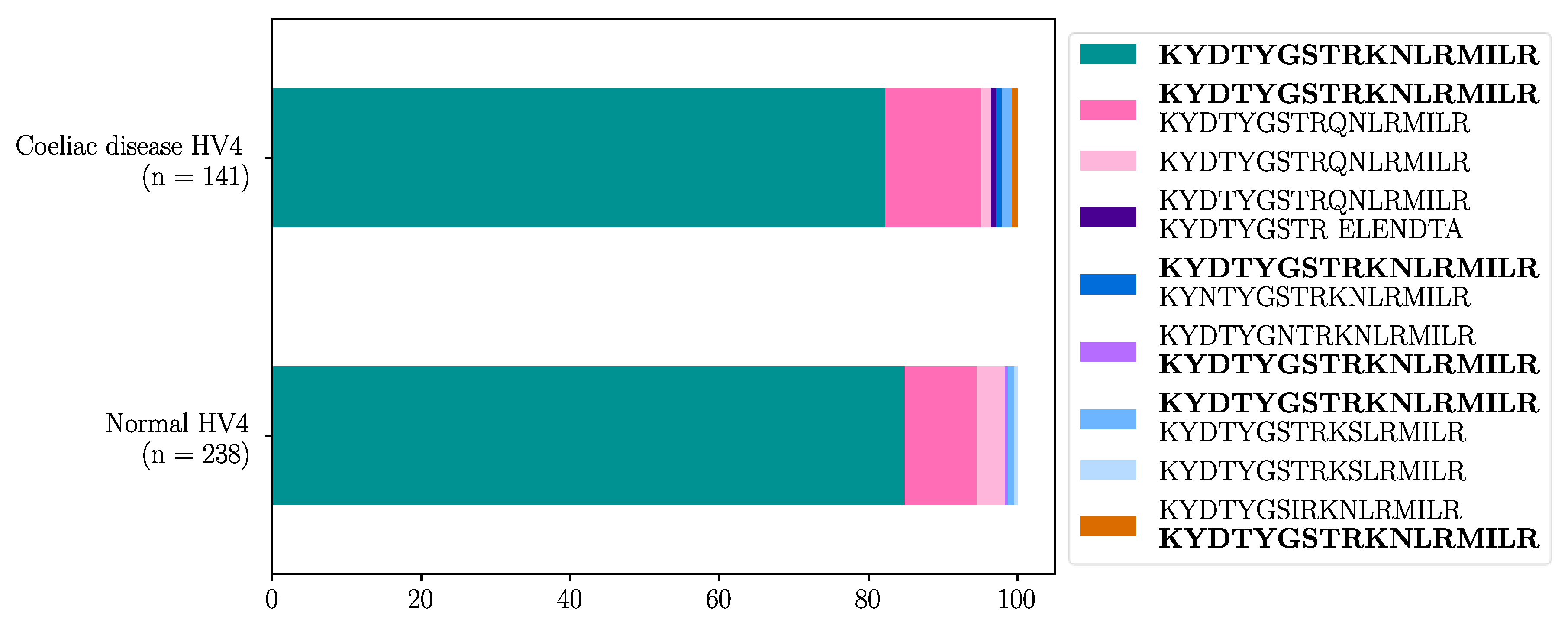

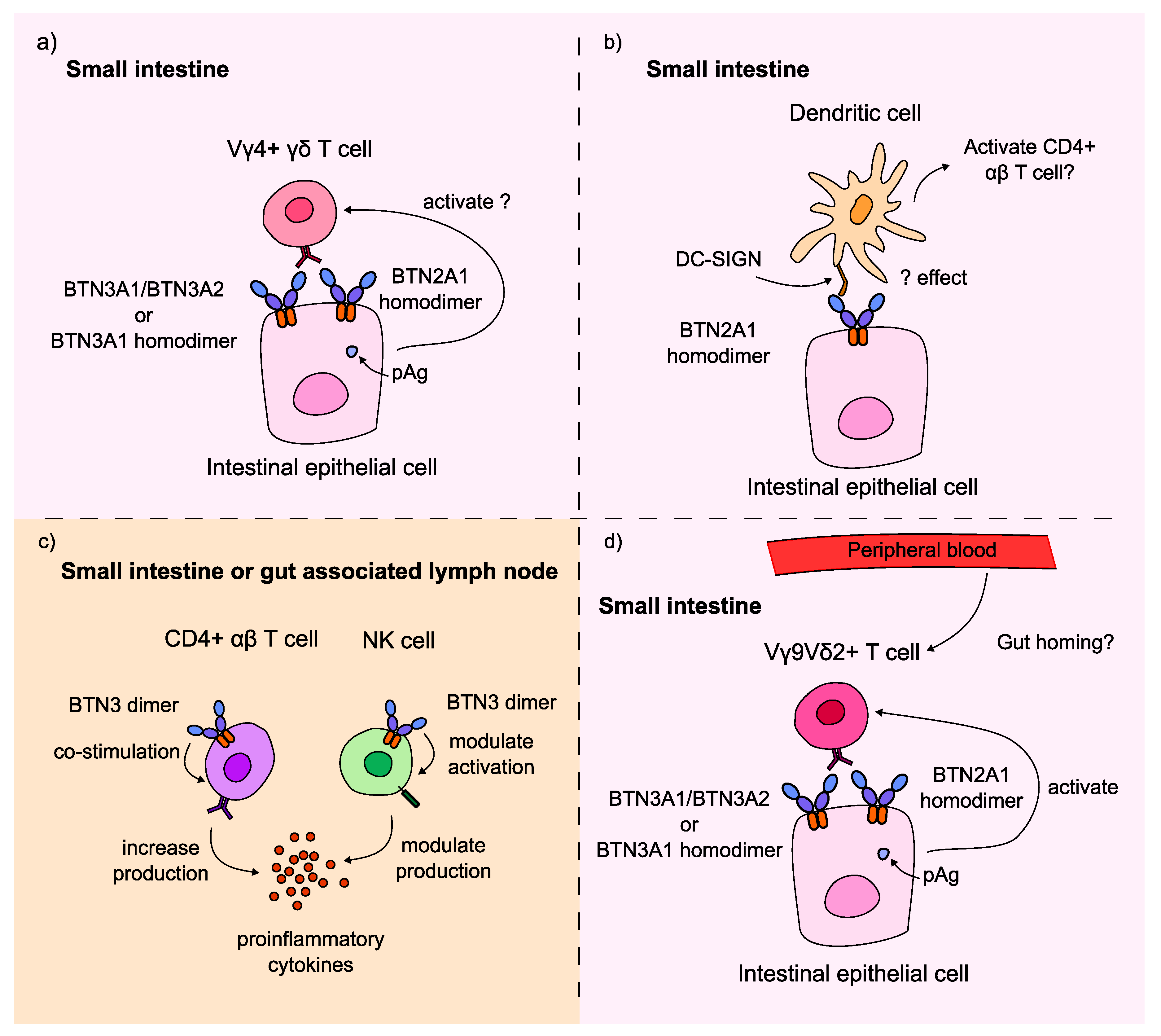

64]. Taking these results together, we provide a new hypothesis for the role of butyrophilins in CeD (Figure 4).

Firstly, these results could imply that BTN2A1 and BTN3A2 could also act on the duodenal Vγ4+ γδ T cells, which is a novel hypothesis as these proteins have only been implicated in activating peripheral blood Vγ9Vδ2+ γδ T cells (Figure 4a). The nature of this interaction is unexplored, and whether these proteins are responsible for pAg-dependent activation of Vγ4Vδ1+ T cells requires further research. This hypothesis could explain why the BTNL8*BTNL3 deletion variant, which encodes a BTNL8*3 fusion protein but no full length BTNL3 or BTNL8 proteins, was not significantly associated with CeD risk in the cohort of 94 samples. Participants who are homozygous for the deletion can only express the BTNL8*3 fusion protein, which is not hypothesised to bind the Vγ4+ TCR. If BTN2A1, BTN3A1, or BTN3A2 could provide a survival signal to the Vγ4Vδ1+ IELs in the healthy small intestine, this could explain why controls could be homozygous for the BTNL3/BTNL8 deletion variant without having CeD.

Secondly, the findings of this project could suggest that BTN2A1 and BTN3 regulate duodenal immune cell activity in the context of CeD. BTN2A1 was identified as a novel ligand for the receptors of DCs, which are important cells in displaying the gluten antigen to CD4+ αβ T cells to induce CeD pathogenesis [

24,

25]. Although the function of this interaction was not explored, taken together with the results of this project, it could explain the association between BTN2A1 and CeD risk, as the protein could regulate the autoimmune response in CeD indirectly via DC activity (Figure 4b). Additionally, previous evidence has shown that BTN3 proteins can provide co-stimulatory signals to αβ T cells, increasing their production of interferon-γ (IFN-γ), a proinflammatory cytokine [

26]. This same study showed the dual effect of butyrophilins on NK cell activity: BTN3A1 upregulated, while BTN3A2 downregulated IFN-γ production and NK cell activation (Figure 4c).

Figure 4.

BTN2A1, BTN3A1 and BTN3A2 may be involved in CeD pathogenesis by modulating T cell and innate immune cell activity. BTN2A1 gene burden was significantly higher in CeD patients in a cohort of 94 samples. Meanwhile,

BTN2A1,

BTN3A1, and

BTN3A2 SNPs were significantly associated with CeD status in the UK Biobank database. Based on our results and evidence on the immunomodulatory role of butyrophilins on innate and adaptive immune cells, butyrophilins could contribute to CeD pathogenesis in multiple potential manners [

25,

26,

37,

38,

63]. a) Via the novel, hypothesised pAg-dependent activation of Vγ4+ γδ T cells; b) via the interaction of BTN2A1 with dendritic cells through the DC-SIGN receptor on the DC cell surface; c) by increasing the co-stimulation and IFN-γ production of CD4+ αβ T cells, or by modulating the activity and IFN-γ production of NK cells depending on whether BTN3A1 or BTN3A2 is expressed predominantly on the surface of the NK cell; or d) via the pAg-dependent activation of potentially gut-homing Vγ9Vδ2+ γδ T cells in the small intestine.

Figure 4.

BTN2A1, BTN3A1 and BTN3A2 may be involved in CeD pathogenesis by modulating T cell and innate immune cell activity. BTN2A1 gene burden was significantly higher in CeD patients in a cohort of 94 samples. Meanwhile,

BTN2A1,

BTN3A1, and

BTN3A2 SNPs were significantly associated with CeD status in the UK Biobank database. Based on our results and evidence on the immunomodulatory role of butyrophilins on innate and adaptive immune cells, butyrophilins could contribute to CeD pathogenesis in multiple potential manners [

25,

26,

37,

38,

63]. a) Via the novel, hypothesised pAg-dependent activation of Vγ4+ γδ T cells; b) via the interaction of BTN2A1 with dendritic cells through the DC-SIGN receptor on the DC cell surface; c) by increasing the co-stimulation and IFN-γ production of CD4+ αβ T cells, or by modulating the activity and IFN-γ production of NK cells depending on whether BTN3A1 or BTN3A2 is expressed predominantly on the surface of the NK cell; or d) via the pAg-dependent activation of potentially gut-homing Vγ9Vδ2+ γδ T cells in the small intestine.

Thirdly, the results of this project could indicate the involvement of peripheral blood Vγ9Vδ2+ T cells in CeD (Figure 4d). Whether these T cells are recruited to infiltrate the small intestine from the peripheral blood or they contribute to CeD pathogenesis in a different way remains unclear. Interestingly, in the analysis of our cohort of 108 healthy control and 45 CeD duodenal samples, only 3-4% of γδ T cells were Vγ9+ T cells (Figure 2, Table 14,). There were no significant differences in the proportion of Vγ9+ T cells in CeD and healthy controls (p = 0.728). Further research is required to investigate the activity of these cells, and whether they interact with butyrophilins in the context of CeD.

In conclusion, the butyrophilin family of genes are promising immunomodulators involved in connecting the adaptive and innate immunity [

24]. Our results provide evidence that the butyrophilin genes

BTN2A1,

BTN3A1, and

BTN3A2 may be putative CeD risk loci. Due to their important roles in the maintenance, activation, and regulation of γδ T cells, the butyrophilins may be involved in the pathogenesis of other autoimmune and inflammatory disorders. Our work provides a clear rationale for further research into the role of the butyrophilin family of genes in CeD.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Participant Selection Criteria

All patient samples used in the HV4 analysis and the targeted sequencing cohort were collected, stored and fully anonymised in line with the Human Tissue Act (England and Wales), 2004, with full ethical approval by the Soilleux group (IRAS project ID: 162057, REC reference: 04/Q1604/21, PI: Prof. E. Soilleux).

CeD patient samples were selected using hospital records, while control samples were selected to exclude suspected CeD patients.

Control exclusion criteria:

Has CeD diagnosis

Malabsorption

Anaemia

Lymphocytosis

On a GFD

Diarrhoea

4.1.1. Participant Selection for the Butyrophilin Family Gene Sequencing

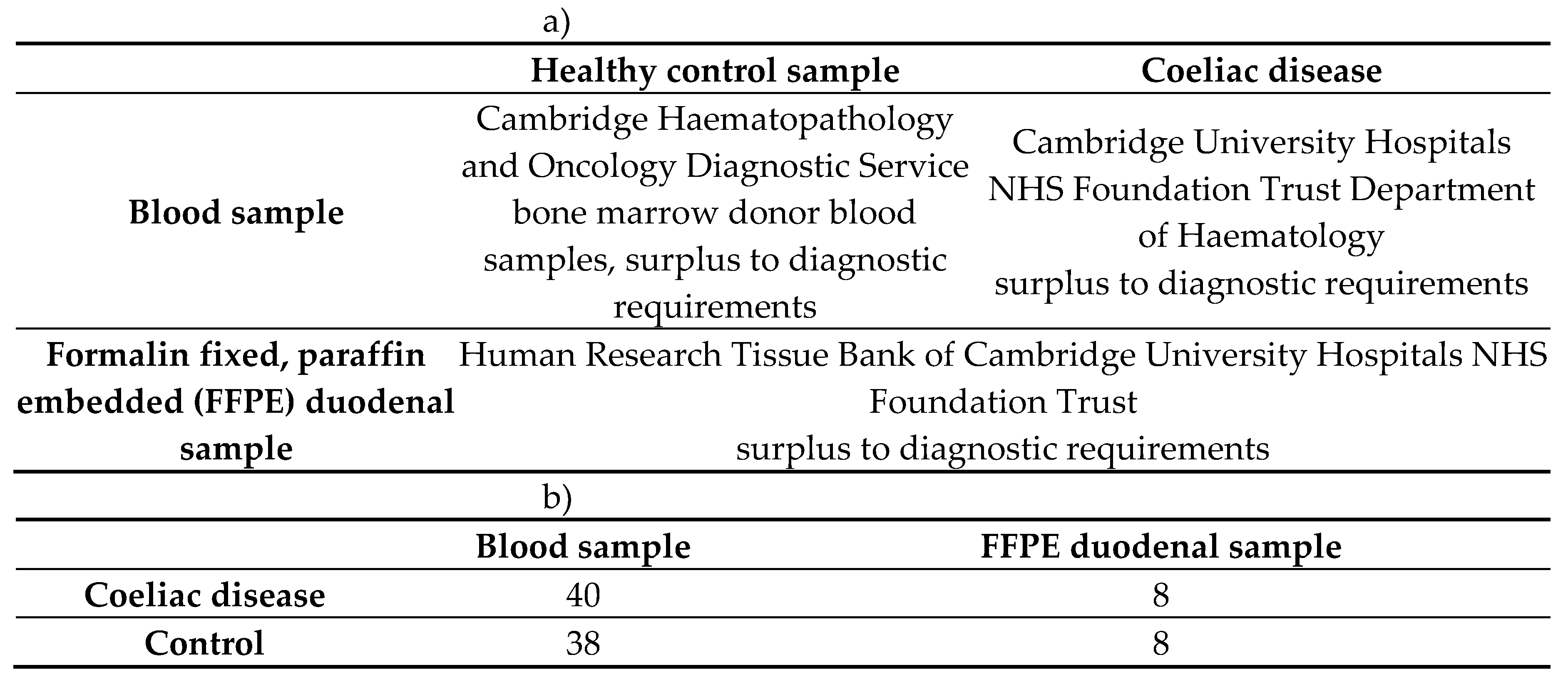

A total of 48 CeD samples and 46 control samples were sequenced for the butyrophilin family variance analysis (Table 13).

Table 13.

94 blood and duodenal samples were sequenced to investigate CeD risk loci. a) Samples were collected from diagnostic surplus samples. b) Both blood and FFPE duodenal samples were collected and sequenced.

Table 13.

94 blood and duodenal samples were sequenced to investigate CeD risk loci. a) Samples were collected from diagnostic surplus samples. b) Both blood and FFPE duodenal samples were collected and sequenced.

4.1.2. Participant Selection for the UK Biobank Single Variant Analysis

For the validation cohort, CeD patients and controls were selected from the anonymised UK Biobank online database using the online Research Analysis Platform (RAP,

https://ukbiobank.dnanexus.com/, application ID: 18532). Participants’ sociodemographic, lifestyle, hospital record information, HLA imputation and genome-wide genotyping data were available from the UK Biobank online resource centre (

https://biobank.ndph.ox.ac.uk/).

Control and CeD participants were identified using the Cohort Browser program on the RAP, which allowed the selection of participants using a graphical user interface. Control and CeD participants were selected based on their responses to the CeD online questionnaire (data-field 21068,

https://biobank.ctsu.ox.ac.uk/crystal/field.cgi?id=21086), the dietary web questionnaire (data-field 20086,

https://biobank.ctsu.ox.ac.uk/crystal/field.cgi?id=20086), and their health records, specifically, their hospital inpatient record (category 2000,

https://biobank.ctsu.ox.ac.uk/crystal/label.cgi?id=2000) and their death record (category 100093,

https://biobank.ctsu.ox.ac.uk/crystal/label.cgi?id=100093). All clinical data of participants were classified using the World Health Organisation’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD) system and made available by the UK Biobank [

65]. Although most of the hospital inpatient data were coded in ICD-10, some of the participants, whose data was collected in Scotland before 1997 were described using ICD-9, as outlined in resource 138483 (

https://biobank.ndph.ox.ac.uk/ukb/refer.cgi?id=138483).

Control exclusion criteria:

Coeliac disease inclusion criteria:

Hospital diagnosis record includes coeliac disease: ICD9 (5790), ICD10 (K90.0)

Cause of death includes coeliac disease: ICD10 (K90.0)

After removing individuals with missing data, the finalised UK Biobank cohort consisted of 3094 CeD patients and 29 762 control participants.

4.1.3. Samples Selected for the HV4 Analysis

The sequencing data from three different datasets were used that were selected using the same criteria. A total of 141 CeD and 238 healthy control tissue samples were selected for the HV4 analysis (Table 14).

Table 14.

The coeliac disease and healthy control patient TRG datasets analysed for TRGV usage and HV4 sequence variations. FFPE: formalin fixed, paraffin embedded.

Table 14.

The coeliac disease and healthy control patient TRG datasets analysed for TRGV usage and HV4 sequence variations. FFPE: formalin fixed, paraffin embedded.

| |

Coeliac disease |

Healthy control |

Sequencing method |

| Dataset 1 |

34 FFPE, 12 fresh frozen duodenal |

97 FFPE duodenal |

Illumina Miseq micro |

| Dataset 2 |

11 FFPE duodenal |

11 FFPE duodenal |

Illumina Miseq |

| Dataset 3 |

84 blood |

130 blood |

Illumina NextSeq |

| Combined |

84 blood,

48 FFPE duodenal,

12 fresh frozen duodenal |

130 blood,

108 FFPE duodenal |

NA |

4.2. Analysis of Butyrophilin Family Variation in the Targeted Sequencing Cohort

4.2.1. Gene Selection and Hybridization Probe Design

The Human Protein Atlas (HPA), alongside previous evidence was used to select the butyrophilin family genes of interest to investigate their potential association with CeD predisposition. The expression profiles of the 15 butyrophilin family members outlined by Rhodes

, et al. [

24] were examined in the HPA in tissues and immune cells that could be involved in CeD pathology. The protein expression in the duodenum, small intestine, rectum, and colon were accessed, or their mRNA expression profiles for gene entries where only the latter was available at the time of analysis (

Appendix E, Table E1). The mRNA expression of each butyrophilin gene was also accessed from the HPA in the following immune cell types: T cells, DCs, NK cells, macrophages, regulatory T-cells and γδ T cells (Table E2).

The reliability scores provided by the HPA for each entry was also considered, which is a value based on the reliability between the RNA sequencing and antibody staining data provided by the HPA.

The finalised list of 10 genes of interest were the following: BTN2A1, BTN2A2, BTN3A1, BTN3A2, BTN3A3, BTNL2, BTNL3, BTNL8, ERMAP, MOG.

The Genome Reference Consortium Human Build 38 patch release 12 (GRCh38.p12) genomic position of the 10 butyrophilin genes of interest were determined using the NCBI database [

66]. The regions targeted by the hybridization probes included the non-coding and coding regions of the gene, as described by their NCBI entry at the time of creating the hybridization panel. The regions of interest were uploaded to the online Nonacus probe design platform (panel id: 890, Table 15) [

67]. To ensure high coverage, 2x tiling was selected, so that each base was covered by 2 probes [

68]. Gap fill was selected to cover any repetitive regions in the genes of interest. The submitted custom panel was generated by the best in class integrated algorithms of Nonacus Ltd. These algorithms created probe panels that maximised coverage of the target regions, while avoiding under or over sequencing any regions [

69]. The finalised uniform coverage probe panel was approved and ordered for hybridization capture.

Table 15.

The GRCh38.p12 genomic location of the selected butyrophilin genes.

Table 15.

The GRCh38.p12 genomic location of the selected butyrophilin genes.

| Gene of interest |

Location (GRCh38.p12) |

| BTN2A1 |

chr6:26,457,955-26,476,622 |

| BTN2A2 |

chr6:26,382,893-26,394,874 |

| BTN3A1 |

chr6:26,402,269-26,415,216 |

| BTN3A2 |

chr6:26,365,170-26,378,320 |

| BTN3A3 |

chr6:26,440,504-26,453,415 |

| BTNL2 |

chr6:32,393,339-32,408,879 |

| BTNL3 |

chr5:180,988,846-181,006,727 |

| BTNL8 |

chr5:180,899,097-180,952,166 |

| ERMAP |

chr1:42,817,122-42,844,991 |

| MOG |

chr6:29,657,092-29,672,365 |

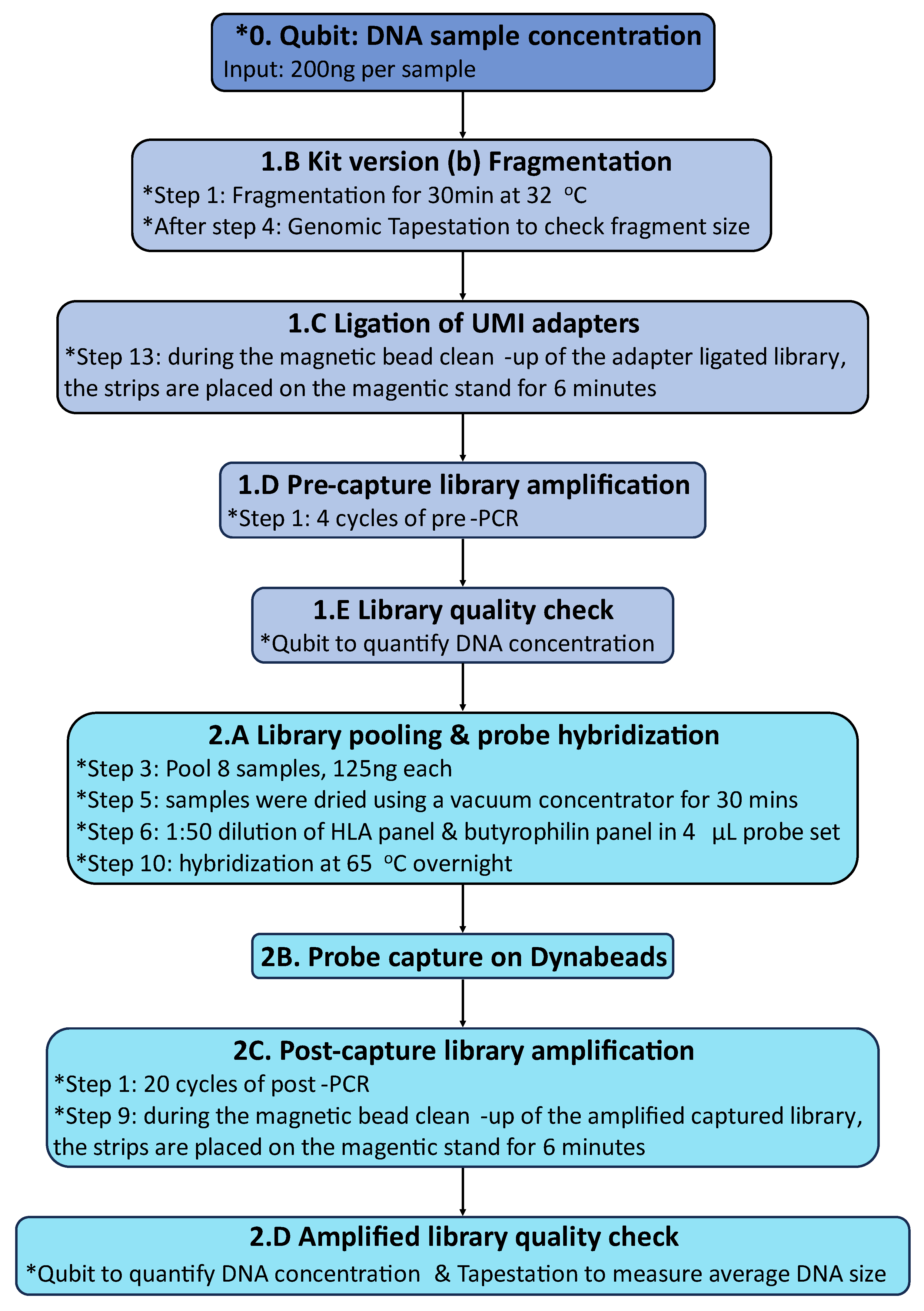

4.2.2. Library Capture and Sequencing of HLA Loci and Selected Butyrophilin Genes

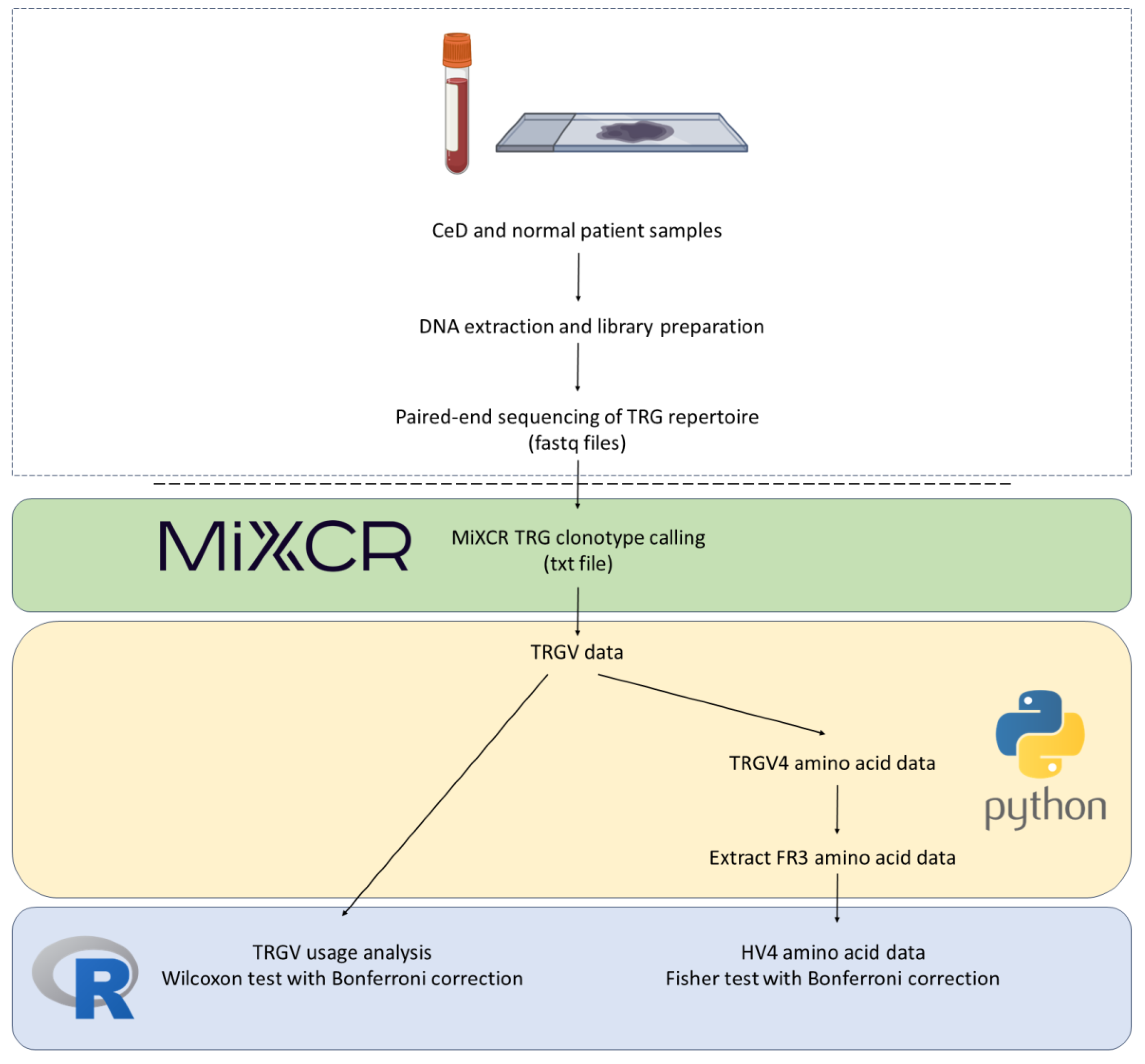

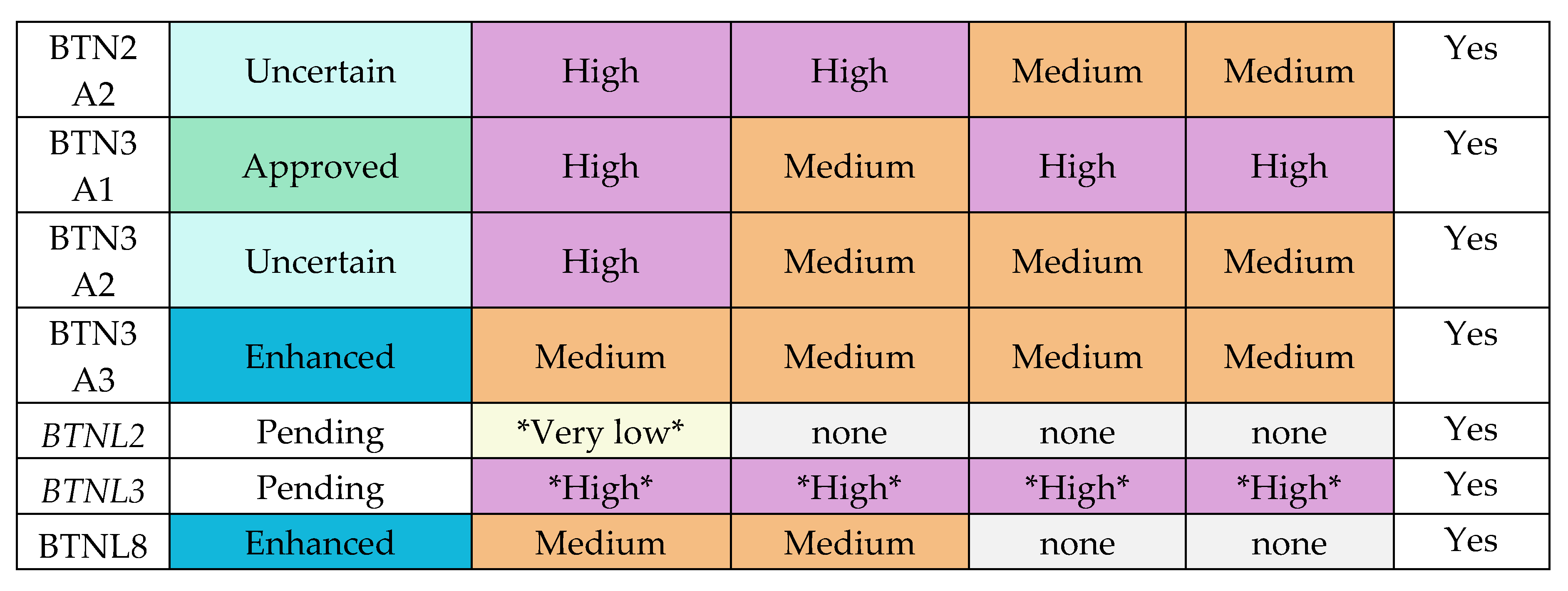

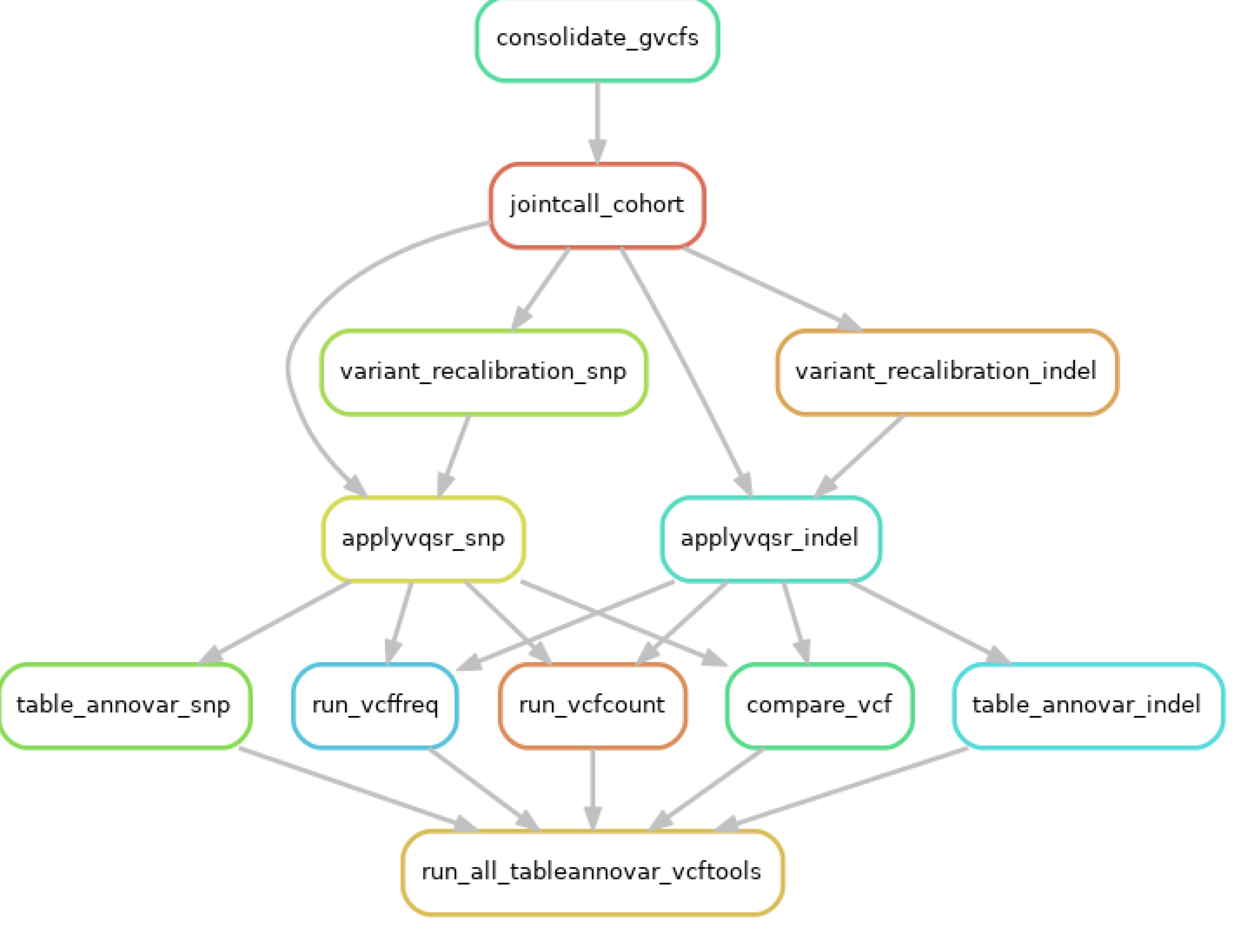

Hybridization capture of healthy control and CeD DNA samples were modified from the Nonacus Cell3 Target Hybridisation & Capture Kit (Nonacus) version (b) protocol (Figure 5,

Appendix E.2-E.3).

HLA hybridization probes were designed and provided by Nonacus Ltd. The captured butyrophilin and

HLA loci library were sent to the Department of Biochemistry, University of Cambridge for sequencing using the Illumina MiSeq system. The targeted genome sequencing data of CeD and control samples are available here:

https://zenodo.org/records/15203243.

Figure 5.

The Nonacus Cell3 capture hybridization capture method was modified for the HLA and butyrophilin sequencing panel. All modifications to the manufacturer’s protocol were noted with *. The HLA probes were provided by Nonacus Ltd.

Figure 5.

The Nonacus Cell3 capture hybridization capture method was modified for the HLA and butyrophilin sequencing panel. All modifications to the manufacturer’s protocol were noted with *. The HLA probes were provided by Nonacus Ltd.

4.2.3. Germline Short Variant Discovery and HLA Typing

The quality of the sequencing files was assessed using the default FastQC v0.11.9 settings, and the Illumina adapters were removed using Trimmomatic v0.39 [

70,

71].

4.2.4. Copy Number Variation (CNV) Analysis of the BTNL8-BTNL3 Loci

The presence of the 56-kb deletion variant in the

BTNL8-BTNL3 loci (chr5:180948027-181003596, GRCh38) was analysed by using a surrogate SNP. Dart

, et al. [

53] were the first to identify the

T>C rs72494581 (chr5:181003797, GRCh38)

BTNL3 intronic SNP to be associated with the CNV (Table 16). The study proposed that the major allele, the

T allele, is associated with the full length

BTNL3 and

BTNL8 genes, while the minor allele, the

C allele, is associated with the

BTNL8*BTNL3 deletion. Fisher’s exact test was performed to investigate any significant differences in the presence of the

BTNL8-BTNL3 CNV between the CeD and control cohorts of the hybridization capture dataset.

Table 16.

The rs72494581 surrogate SNP was used to infer the CNV at the BTNL8-BTNL3 region of chromosome 5.

Table 16.

The rs72494581 surrogate SNP was used to infer the CNV at the BTNL8-BTNL3 region of chromosome 5.

| rs72494581 genotypes |

Associated CNV at BTNL8-BTNL3 region of chromosome 5 |

| TT |

Homozygous for reference allele |

Full length BTNL8-BTNL3 region on both copies of chromosome 5 |

| CT |

Heterozygous |

1 copy has full length BTNL8-BTNL3 region

1 copy has BTNL8*BTNL3 deletion |

| CC |

Homozygous for alternative allele |

BTNL8*BTNL3 deletion on both copies of chromosome 5 |

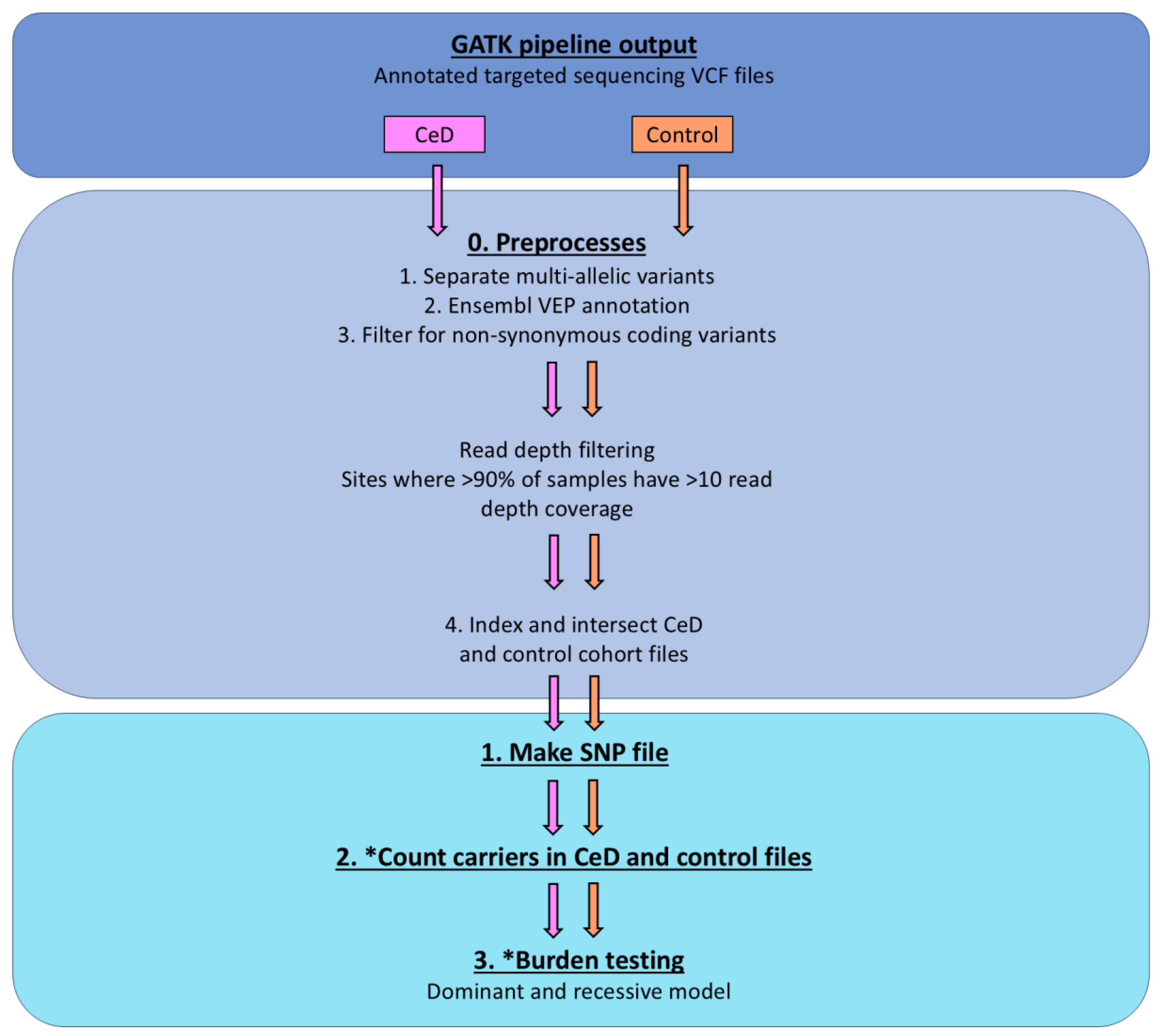

4.2.5. Burden Testing Analysis

The TRAPD program was used for burden testing the variants found in selected butyrophilin genes in samples of the targeted sequencing cohort [

54]. To summarise, qualifying variants within a gene were selected, that had a low minor allele frequency or were predicted to be pathogenic. Any qualifying SNPs with more than two alleles, called multi-allelic sites, were split into SNPs with two alleles for the analysis: the reference allele and one of the alternative alleles. These variants are termed bi-allelic variants [

55]. The disease risk burden, or the number of minor alleles, in the control and CeD cohorts was counted and compared. The burden testing was performed using dominant models and recessive models in TRAPD. The dominant model considers individuals as carriers for gene burden, if they have at least one qualifying variant from the selected sites within the gene, while the recessive model requires the presence of two or more variants to be labelled a carrier [

55]. As gene burden is an additive value, the zygosity of the qualifying sites do not matter, only the number of qualifying variants. For example, in a gene with 3 qualifying sites, an individual who is homozygous for the alternate allele for one qualifying site carries the same amount of gene burden as an individual who is heterozygous for two of the qualifying sites. The analysis was modified from the one described by Guo [

55], to adapt it to the this cohort, as the original pipeline used an external control dataset.

The GATK processed sequences were subjected to further preprocessing before being burden tested with TRAPD, as recommended by Guo [

55]. First, multi-allelic variants were separated using BCFtools version 1.16, as required by the TRAPD manual [

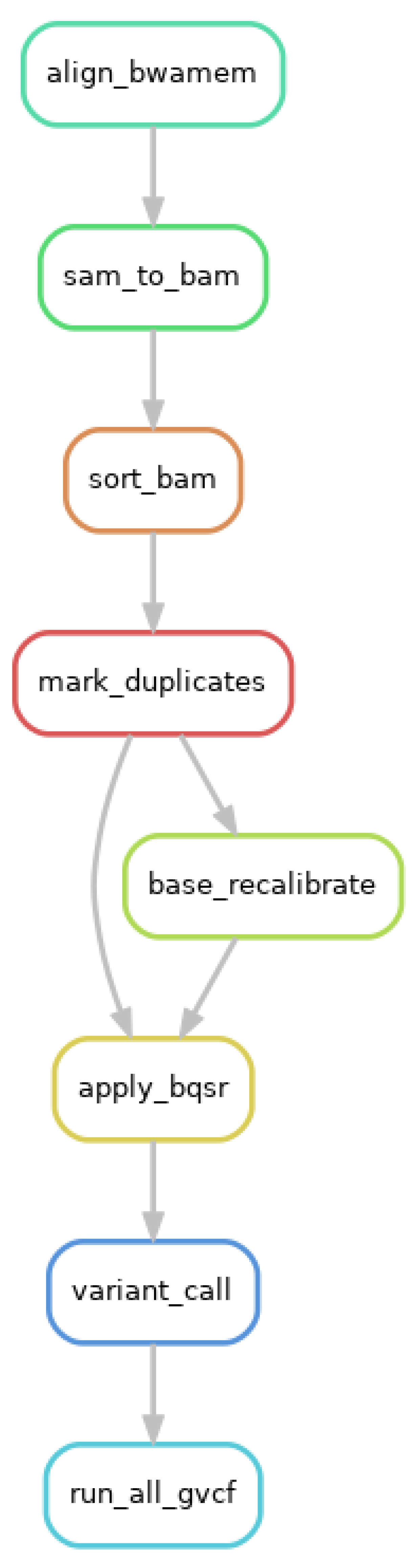

78]. Next, the control and CeD cohort sequencing files were annotated using Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) 109.3, and the SNPs were filtered to contain only non-synonymous coding variants [

79]. The hybridization capture sequencing files were then analysed after read depth filtering (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The variants in the CeD cohort (n = 48) were burden tested via the controls (n = 46) using the TRAPD program. Test Rare vAriants with Public Data (TRAPD) was used to burden test the variants in the hybridization capture CeD cohort (n = 48) against the control cohort (n = 46) [

54]. The annotated CeD and control files from the GATK pipeline were preprocessed as recommended by the manual [

55]. The variants were burden tested after read depth filtering. Steps, in which the code was modified is marked with *.

Figure 6.

The variants in the CeD cohort (n = 48) were burden tested via the controls (n = 46) using the TRAPD program. Test Rare vAriants with Public Data (TRAPD) was used to burden test the variants in the hybridization capture CeD cohort (n = 48) against the control cohort (n = 46) [

54]. The annotated CeD and control files from the GATK pipeline were preprocessed as recommended by the manual [

55]. The variants were burden tested after read depth filtering. Steps, in which the code was modified is marked with *.

The cohort files were read depth filtered using VEP to select sites, where more than 90% of samples had a read depth coverage of >10. The final step of the preprocessing was to index and intersect the CeD and control sequencing files, to get the common SNPs between the two groups.

Following the preprocessing, the TRAPD code was applied using python 2.7 to create the SNP file from the CeD and the control cohort sequencing files using `make_snp_file.py`, which contains the qualifying variants from each gene. Carriers of the qualifying SNPs from both the control and the CeD files were counted using the `count_cases.py` file. The `burden.R` code was modified to adapt it to the targeted sequencing cohort, as the original pipeline used an external database as the control, while this analysis uses the control sequences from the same cohort. The variants in the CeD and control groups were burden tested using both the recessive and the dominant models.

4.3. Single Variant Testing Butyrophilin Family Variance in the UK Biobank Database

4.3.1. CeD Risk Associated HLA Genotyping Using the HLA Imputation Values of the UK Biobank 500,000 Genome-Wide Genotyping Cohort

To summarise, the code used the HLA imputation values from data-field 22182. These values describe the likelihood of each

HLA genotype, of which 14 were

HLA-DQA1 alleles and 18 were

HLA-DQB1 alleles. The

HLA alleles were imputed by the UK Biobank from SNP data using the HLA*IMP:02 program [

80]. In resource 182 (

https://biobank.ctsu.ox.ac.uk/crystal/refer.cgi?id=182), the UK Biobank suggested using a threshold value of 0.7. If any