Submitted:

20 September 2025

Posted:

22 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Elements of a Planar Graph

3. Determination of Extremal Topologies for the 4-Coloring

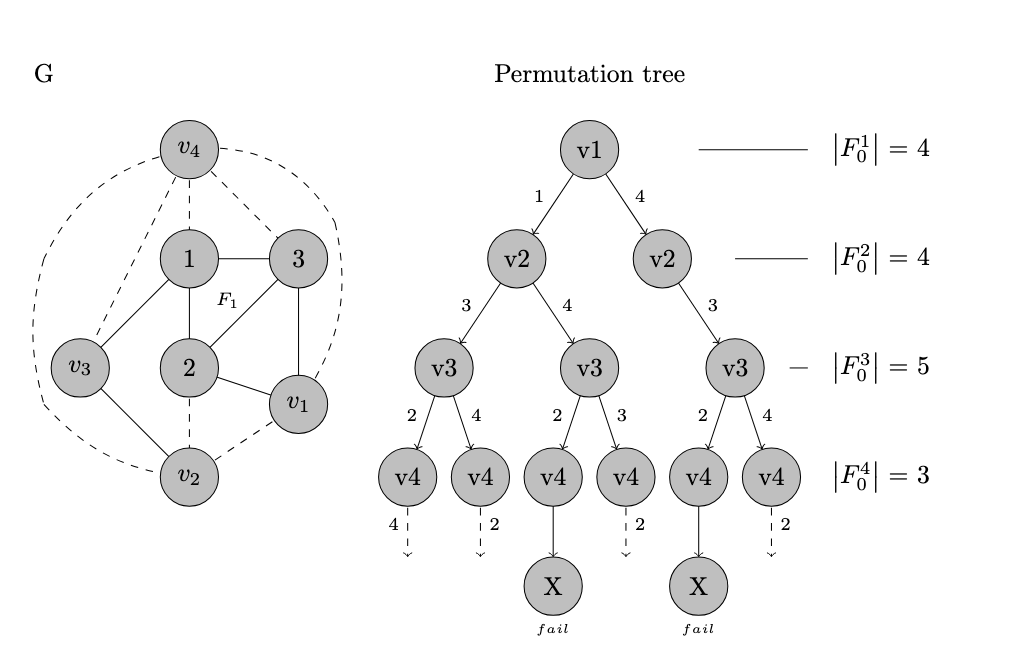

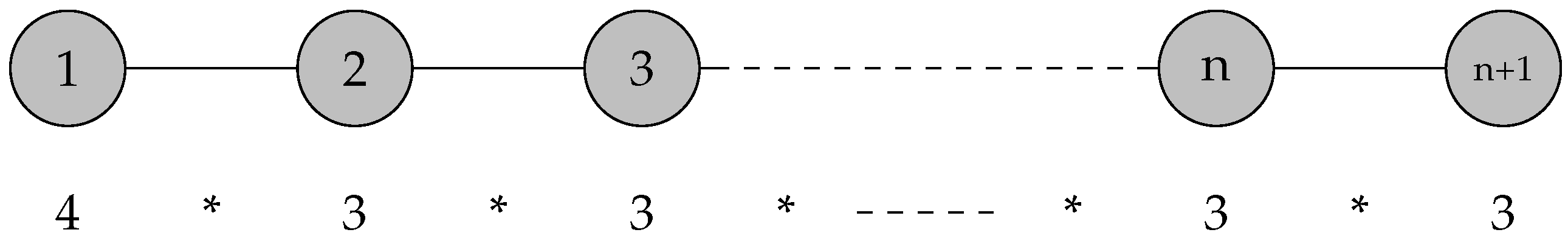

3.1. Counting 4-Colouring Process

4. Principal Procedures and Structures

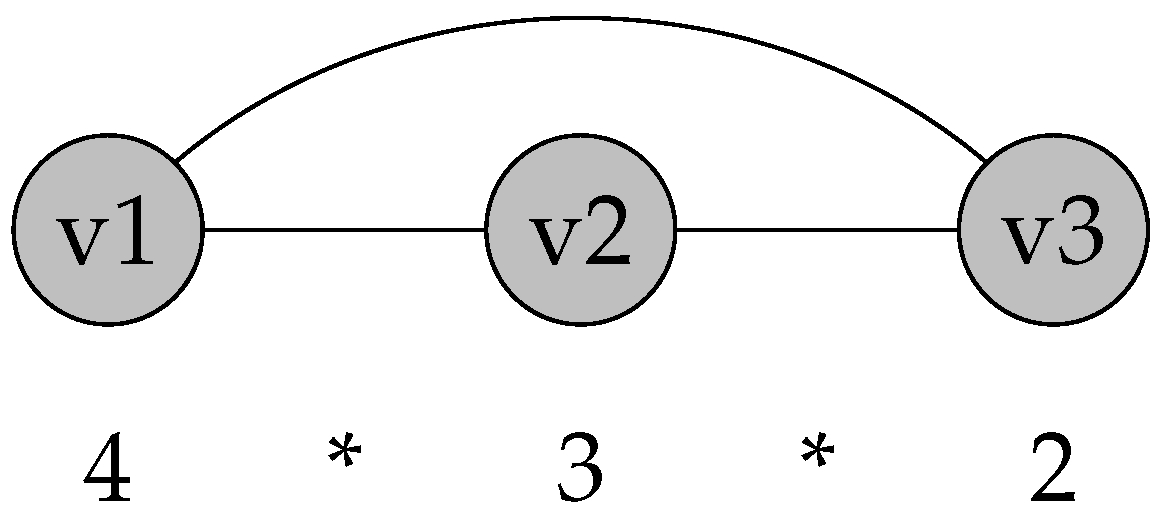

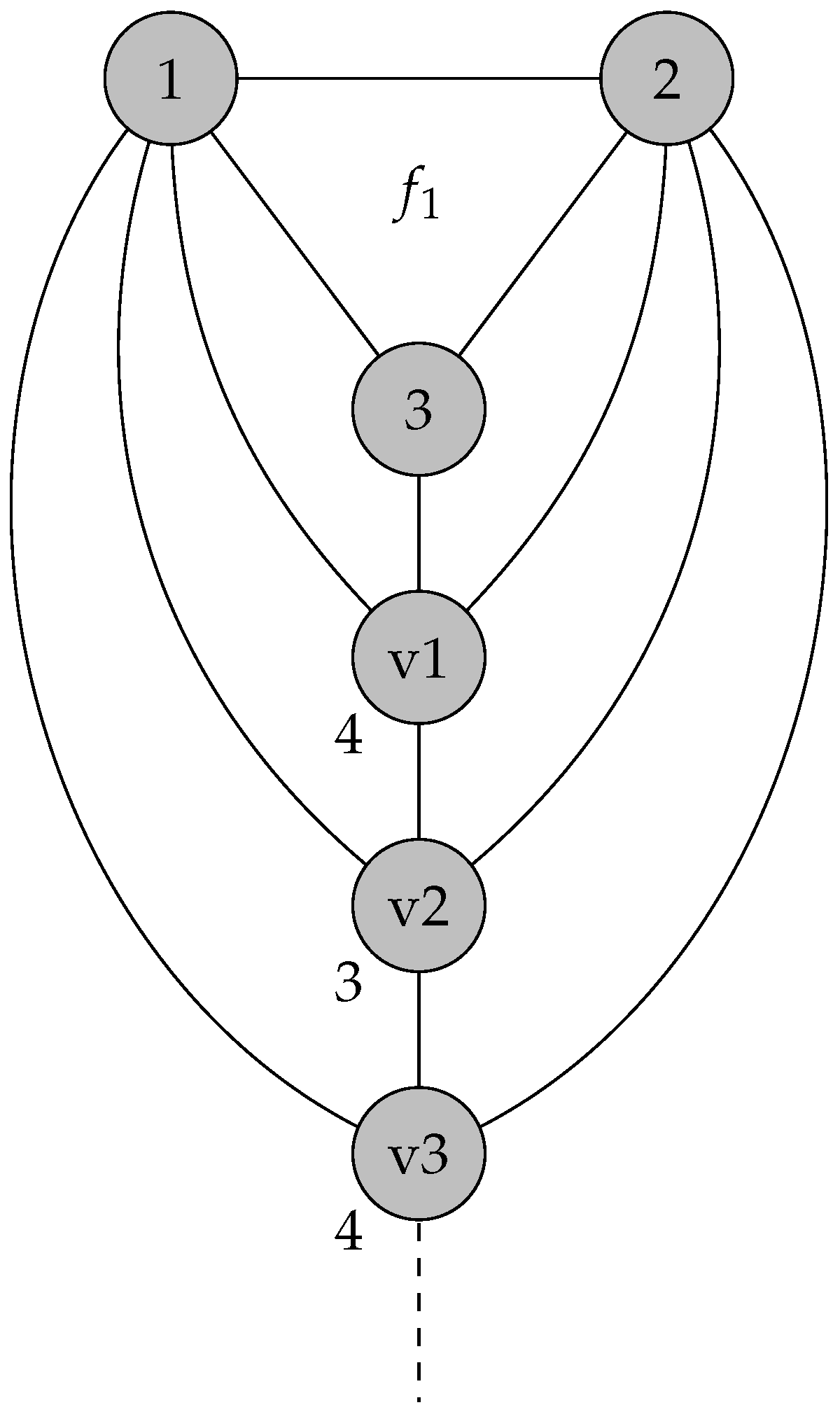

4.1. Decomposition in Layers of a Planar Graph

4.2. Rebuilding the Original Planar Graph

- The remaining vertices are in the outside face of .

- is maximum into the set of vertices in .

- Considering the current layer from the process of decomposition in layers of G, is in a first instance in , or in of G.

- When some vertices are holding all previous criteria, is the following vertex according to the clockwise direction from the vertex .

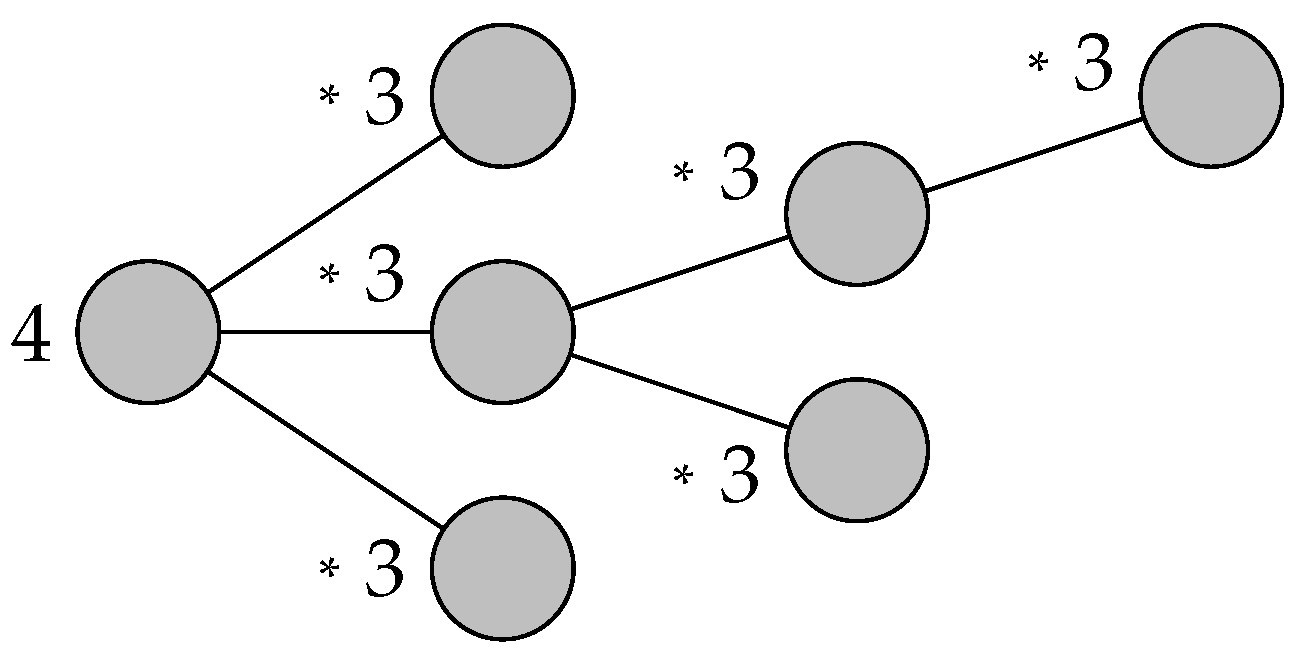

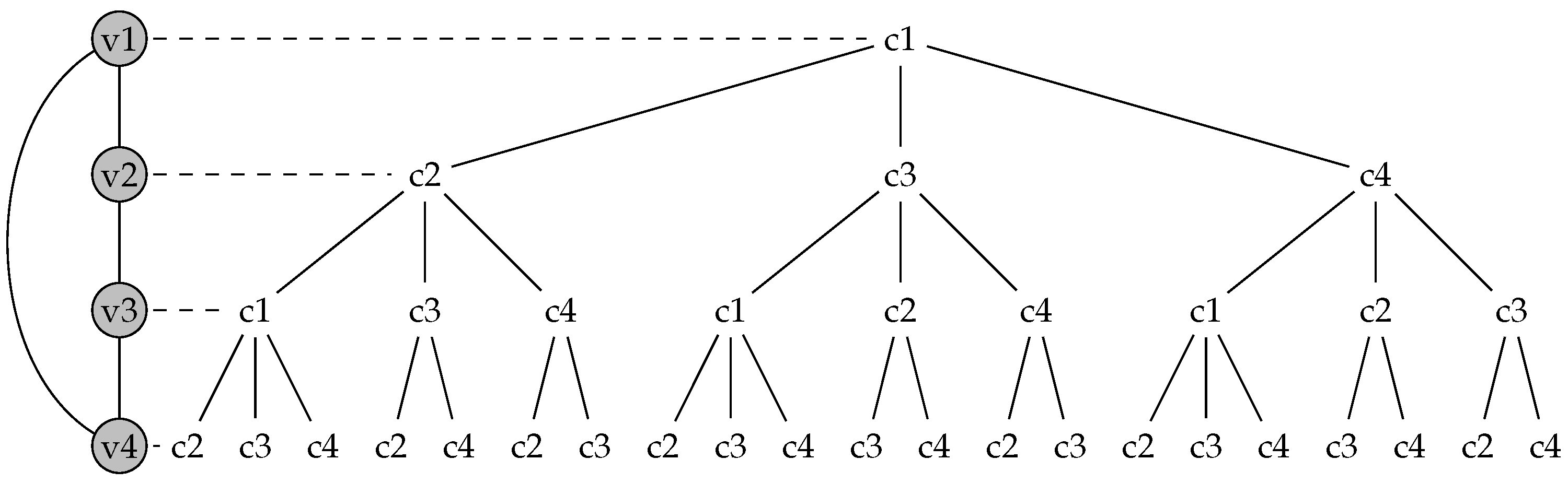

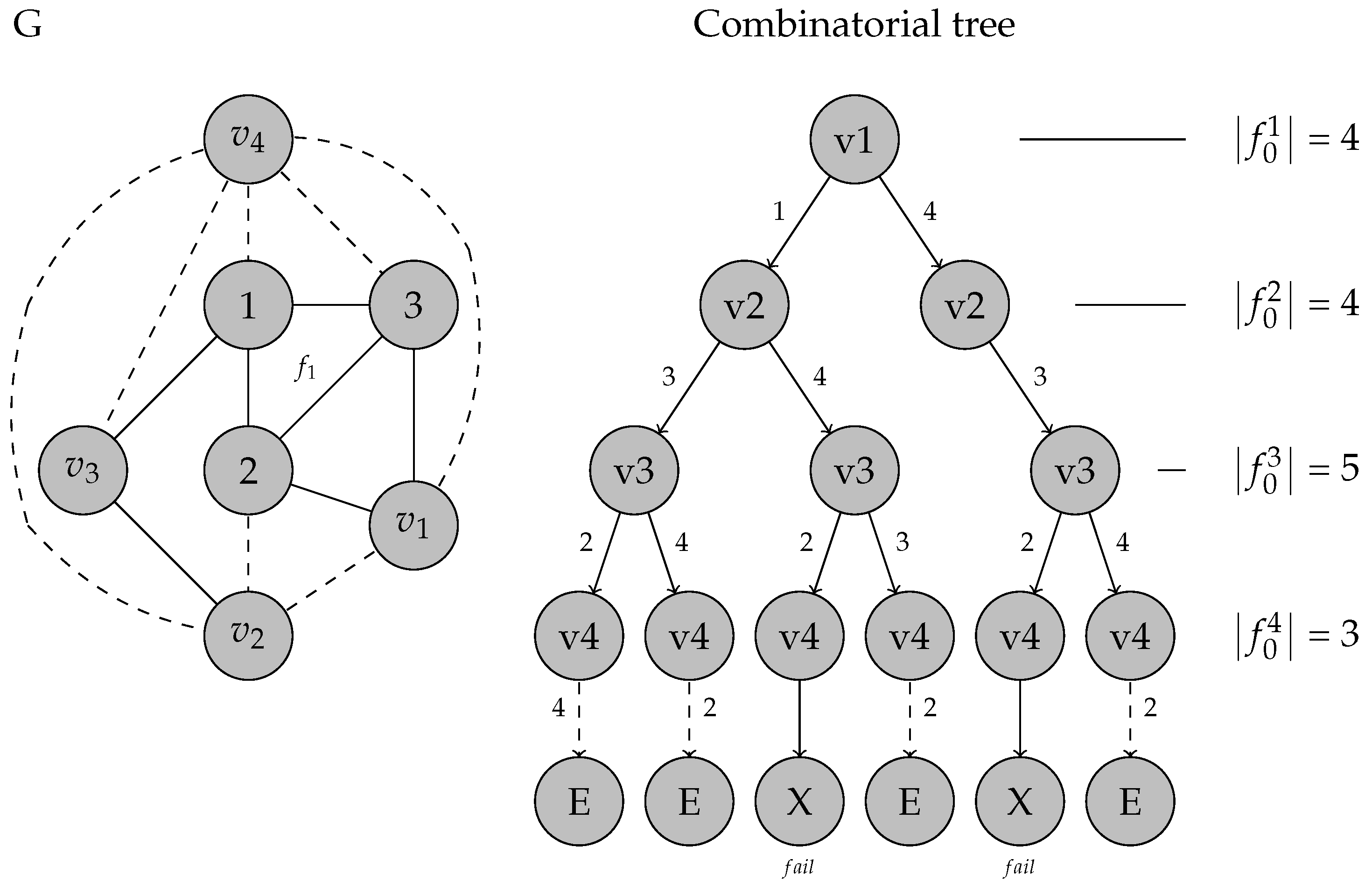

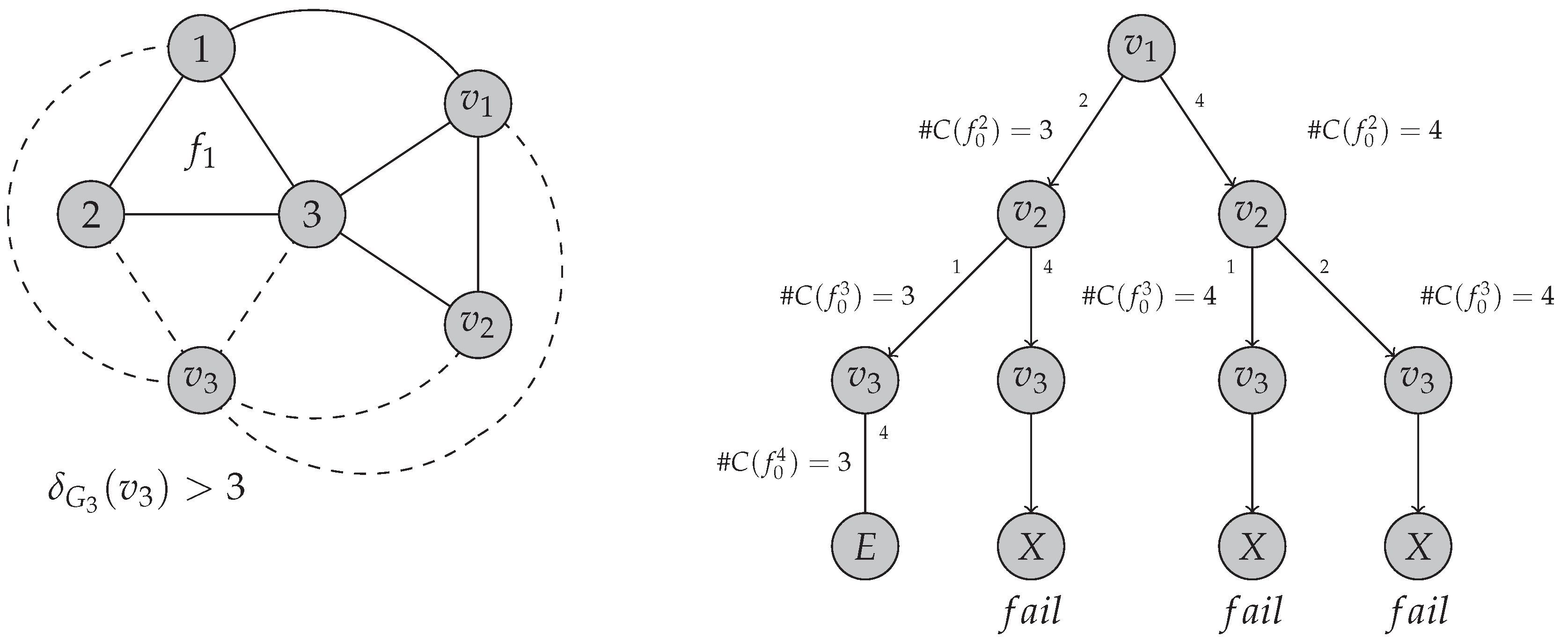

4.3. Combinatorial Tree

5. Proof of the Existence of a 4-Coloring for Planar Graphs

- 1)

-

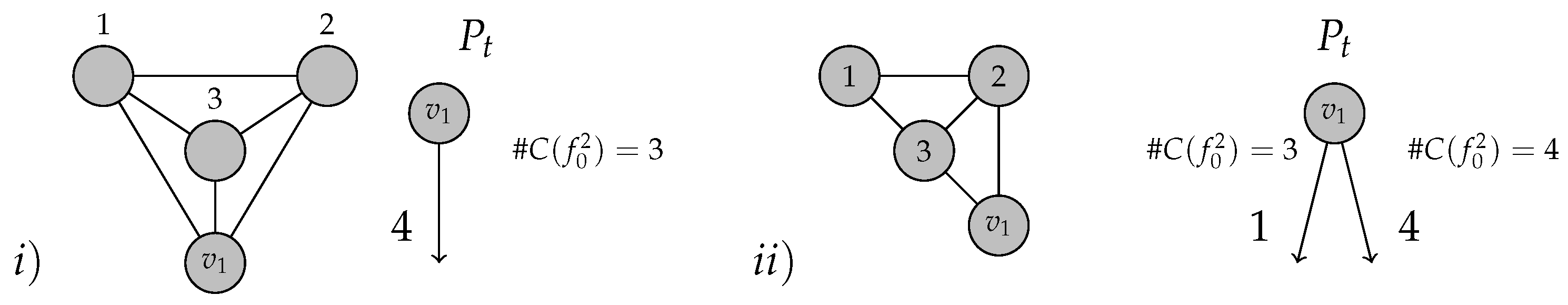

For , the first subgraph holds that , since the outer face is a triangular face.From only two cases can be derived to form . When (illustrated in Figure 7(ii), and when illustrated in Figure 7(i). Notice that for both cases, there is a path in such that .For example, in the case . (Figure 7(ii), As one of the possible colours to be assigned to , it already appears in (in the most left path of ), does not add any new colour to the current outer face and then, .

- 2)

- By induction hypothesis, at level , there are paths in where the current outer face of has less than 4 colours, i.e. .

- 3)

-

When a new vertex is aggregated to , we form with outer face , and the combinatorial tree is extended one level more, this is from to . We analyze different cases:For the paths where , or , if assigns a color that already appears in , it will be satisfied that , and therefore, the theorem holds.Let us consider the case when , and analyze its development according to the value of .

- i)

- When , then ramifies with two possible colors, say and . If , then could have 4 colors when the color is included in . However as and , then must be in and the branch for will not increment with respect to , and therefore for this path 4 (as it was illustrated in the leftmost path of Figure 7(ii)).

- ii)

-

If . Assuming , by adding to a vertex of degree 3, the cardinality is preserved: 3 (by results from Table 1 - derived of the Euler’s equality), and therefore 4.Let us assume 3, so now we could take . This combination of parameters is analysed in the following case.

- iii)

-

To have , is only achieved by adding vertices , where , which allows increasing the cardinality of the outer face above 3, and also, it generates binary ramifications at the level , using two different colors for , let us say and .In one of the colors (either or ), we have . This is because, in all ramifications, at least one of the colors used is already present in . In fact, for all levels from k to , there are paths where for . Furthermore, according to the inductive hypothesis, there are paths at level where . Within these set of paths of , there is at least one path where the color is already included in . This is due to the exhaustiveness in the color assignment to the branches of . For these particular paths, the cardinality of does not increase for the following level; hence, we conclude that , and this confirms that the theorem holds true.Furthermore, by adding vertices with , new internal vertices are formed in , thus causing some of the colors assigned to those internal vertices to no longer appear in .

6. Conclusion

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 4CC | The Four Color Conjecture |

| 4CT | Four-Color Theorem |

| 4Col | the set of all proper 4-coloring of H |

| 4c | the total number of different 4-colorings functions of H |

| Color(H) | the set of colors used in a 4-coloring of H |

| the number of different colors used in a 4-coloring of H |

References

- Appel K.; Haken W., Every planar map is four colourable, part I: discharging, Illinois Jour. Math. 1977, 21, 429-–490.

- Appel K.; Haken W.; Koch J., Every planar map is four colourable, part II: Reducibility, Illinois Jour. Math. 1977, 21, 491–567.

- Borodin O., Colorings of Plane Graphs: A Survey, Discrete Mathematics 2013.

- Bousquet N.; Deschamps Q.; De Meyer L., Pierron T., Square Coloring Planar Graphs with Automatic Discharging, SIAM Jour. on Discrete Mathematics 2024, 38:1, 504–528.

- Cortese P.; Patrignani M., Planarity Testing and Embedding, Press LLC, 2004.

- Cranston D. W.; West D. B., An introduction to the discharging method via graph coloring, Discrete Mathematics 2017, 340:4, 766–793.

- Fritsch R.; Fritsch G., The Four Color Theorem. Springer-Verlag, 1998.

- Garey, M.R.;Johnson, D.S., Computers and Intractability: A Guide to the theory of NP-Completeness, W.H. Freeman, 1979.

- Gonthier G., Formal Proof - The Four Color Theorem, Notices of the AMS 2008, 55:11.

- Harary F., Graph Theory, Addison-Wesley, Readings, Mass., 1969.

- Johnson D. S., The NP-Completeness Column: An Ongoing Guide, Jour. Of Algorithms 1985, 6, 434 - 451.

- Kempe A. B., On the Geographical Problem of the Four Colours, American Jour. of Mathematics 1879, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2:3.

- Kuratowski K., Sur le probleme des courbes gauches en topologie, Fund. Math. 1930, 15, 271–283.

- Köbler, J.; Schöning, U.; Toran, J., The graph isomorphism problem: its structural complexity, In Graph canonization and hardness, 1993.

- László L., Graph minor theory, Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 2006, 43:1, 75-–86.

- McKay, B.D.; Piperno, A., Practical graph isomorfism II, Jour. of symbolic computation 2014, 60, 94-112.

- Nishizeki T.; Chibam N., Planar graphs : theory and algorithms, Annals of discrete mathematics 1991, 32, Elsevier.

- Robertson N.; Sanders D.P.; Seymour P.D.; Thomas R., The four color theorem, Jour. Combin. Theory Ser. B 1997, 70, 2-–4.

- Tymoczko T., The Four-Color Problem and its Philosophical Significance, The Journal of Philosophy 1979, 76:2.

| n | m | f |

| 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | 3 | 2 |

| 4 | 6 | 4 |

| 5 | 9 | 6 |

| 6 | 12 | 8 |

| 7 | 15 | 10 |

| … | … | … |

| 1 | 3 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).