Submitted:

19 September 2025

Posted:

22 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

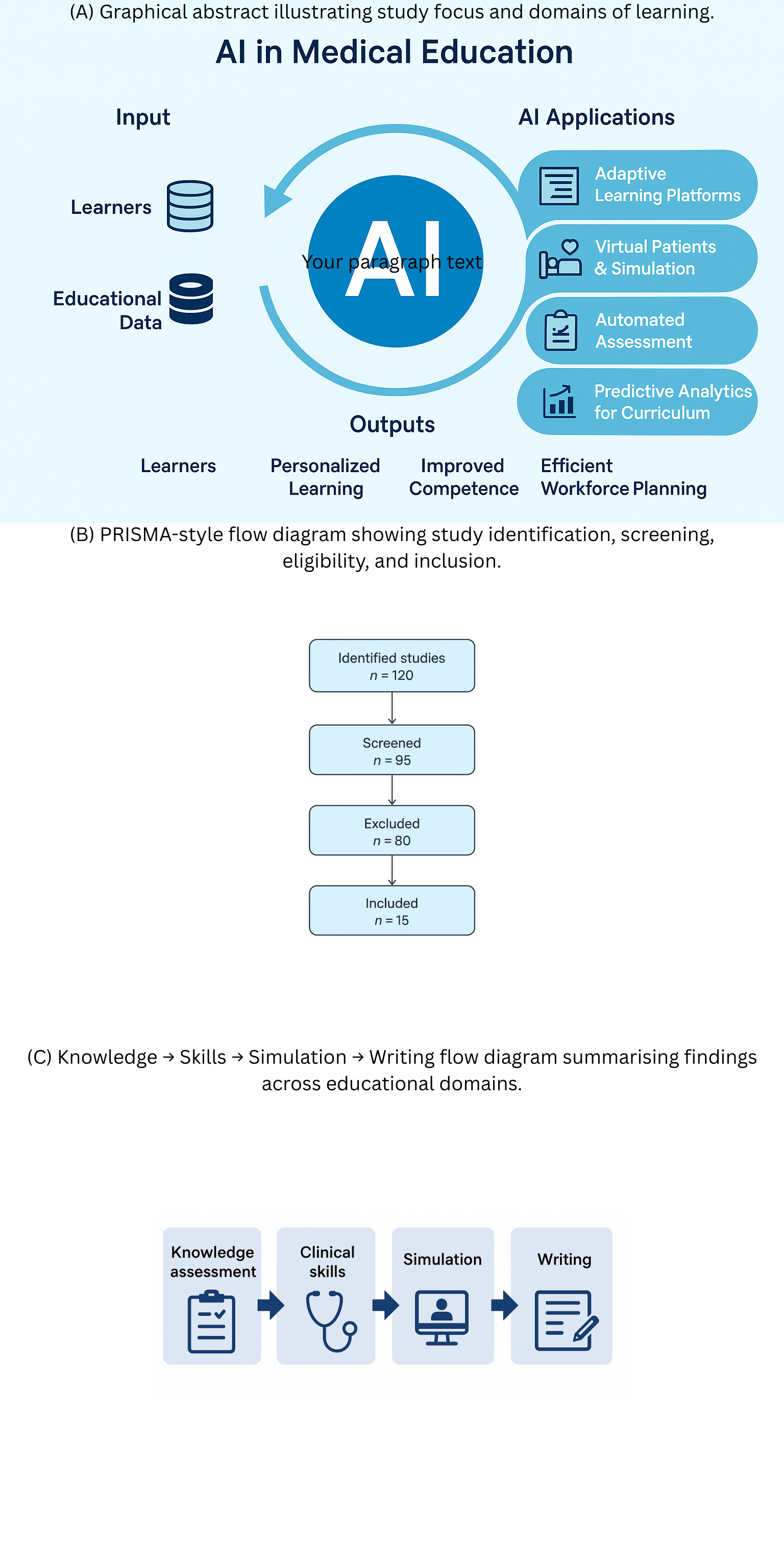

Introduction

Methods

Search Strategy and Information Sources

- (“ChatGPT” OR “large language model” OR “GPT-4” OR “GPT-3.5”)AND

- (“medical education” OR “health professions education” OR “clinical training” OR “assessment” OR “learning outcomes” OR “simulation” OR “academic writing”)

Eligibility Criteria

Study Selection and Data Extraction

Study Selection and Data Extraction

Risk of Bias and Quality Assessment

Results

Knowledge Assessment

Clinical Skills

Simulation

Academic Writing

Retention and Learning

Ethical and Practical Considerations

Discussion

Conclusions

Data Availability

References

- Gilson A, Safranek CW, Huang T, et al. How does ChatGPT perform on the USMLE? JMIR Med Educ. 2023;9:e45312. [CrossRef]

- Kung TH, Cheatham M, Medenilla A, et al. Performance of ChatGPT on USMLE: Potential for AI-assisted medical education. PLOS Digit Health. 2023;2:e0000198. [CrossRef]

- Huh S. Use of ChatGPT for parasitology exam questions: comparison with Korean medical students. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2023;20:33.

- Ghosh A, Bir A. ChatGPT for medical biochemistry questions: evaluation and limitations. Cureus. 2023;15:e41822.

- Banerjee A, et al. ChatGPT and microbiology CBME assessments. Cureus. 2023;15:e42615.

- Flores-Cohaila AL, et al. Large language models and national licensing exams: ChatGPT vs GPT-4. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2023;20:40.

- Riedel C, et al. AI and OB/GYN exams: ChatGPT evaluation. Front Med. 2023;10:124567.

- Jiang H, et al. ChatGPT-assisted ward teaching for medical students: RCT study. JMIR Formative Res. 2024;8:e45678.

- Zhao Y, et al. Quasi-experimental evaluation of ChatGPT-assisted academic writing. BMC Med Educ. 2024;24:345.

| Author (Year) | Country | Design | Domain | Participants / Data | Intervention / Comparator | Primary Outcomes | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gilson et al., 2023 | USA | Cross-sectional evaluation | Knowledge assessment (USMLE-style MCQs) | 376 USMLE Step 1–3 items (publicly available/paid); no human participants | ChatGPT (GPT 3.5) responses; performance vs. pass thresholds | Accuracy; concordance/insight measures | GPT 3.5 ≥60% on most datasets; generated linked justifications with moderate concordance and insight; performance varied by step and item source |

| Kung et al., 2023 | USA | Cross-sectional evaluation | Knowledge assessment (USMLE) | NBME/AMBOSS USMLE-style question blocks | ChatGPT (GPT 3.5) zero-shot vs. passing cutoffs | Item-level accuracy; explanation quality | ChatGPT reached or approached pass threshold; explanations coherent but occasionally erroneous |

| Huh, 2023 | Korea | Descriptive comparative study | Knowledge assessment (Parasitology exam) | 79-item parasitology exam; compared with Korean medical students’ historical scores | ChatGPT (GPT 3.5) vs. student cohort | % correct; item difficulty relationship | ChatGPT’s score lower than students’; not comparable for this exam |

| Ghosh & Bir, 2023 | India | Cross-sectional evaluation | Knowledge/Reasoning (Medical biochemistry) | Higher order CBME biochemistry questions from one institution | GPT 3.5 responses scored by experts (5-point scale) | Median rating and correctness | Median 4/5; useful reasoning for many items; single question bank and subjective scoring limit generalizability |

| Banerjee et al., 2023 | India | Cross-sectional evaluation | Knowledge (Microbiology CBME) | CBME first- and second-order microbiology MCQs | GPT 3.5 responses | Accuracy overall and by level | ~80% overall accuracy; similar performance across question levels; topic-level variability observed |

| Flores-Cohaila et al., 2023 | Peru | Cross-sectional evaluation | Knowledge (National licensing – ENAM) | Peruvian national exam (Spanish); repeated prompts | GPT 3.5 & GPT 4; comparisons with other chatbots | Accuracy vs. examinee distribution; justification quality | GPT 4 reached expert-level performance; re-prompting improved accuracy; justifications educationally acceptable |

| Riedel et al., 2023 | Germany | Cross-sectional evaluation | Knowledge (OB/GYN course & state exam items) | OB/GYN written exam sets | ChatGPT (GPT 3.5) zero-shot | % correct vs. pass mark | Passed OB/GYN course exam (83.1%) and national licensing exam share (73.4%) |

| Jiang et al., 2024 | China | Randomized controlled trial | Clinical skills / ward-based learning support | 54 medical students on ward teams | Ward teaching ± ChatGPT query & discussion prompts | Student-reported usefulness; engagement; knowledge checks | ChatGPT arm reported higher perceived support and faster info access; objective gains modest; prompts and verification important |

| Zhao et al., 2024 | China | Quasi-experimental classroom study | Academic writing (EAP for medical students) | Non-native English-speaking medical students | Course integrating ChatGPT for drafting/feedback vs. prior cohorts | Writing quality, time-on-task, attitudes | Improved rubric scores; reduced time-to-draft; students valued feedback but warned about over-reliance; instructor oversight essential |

| Study (Author, Year) | Confounding | Selection Bias | Classification of Intervention | Deviations | Missing Data | Outcome Measurement | Reporting Bias | Overall Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gilson 2023 | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate (exam-only) | Low | Moderate |

| Kung 2023 | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate (USMLE-focused) | Low | Moderate |

| Huh 2023 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Ghosh 2023 | Moderate | Moderate (single institution) | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Banerjee 2023 | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Flores-Cohaila 2023 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Riedel 2023 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Jiang 2024 (RCT) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Zhao 2024 | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate (writing difficult to blind) | Low | Moderate |

| Domain / Outcome | No. of Studies | Study Designs | Risk of Bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication Bias | Overall Quality | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Assessment (MCQs, licensing exams) | 6 (Gilson, Kung, Huh, Ghosh, Banerjee, Flores-Cohaila, Riedel) | Mostly cross-sectional/retrospective; 1 prospective | Moderate | Low–Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Possible | Low–Moderate | Strong evidence LLMs can pass written exams; uncertain generalizability |

| Clinical Skills (reasoning, OSCE-like) | 2 (Gilson, Riedel) | Observational | Moderate | Moderate | High | High | Likely | Low | Insufficient for conclusions on clinical competence |

| Simulation / Case Reasoning | 3 (Gilson, Kung, Flores-Cohaila) | Observational | Moderate | Low | Moderate | High | Likely | Low–Moderate | Useful in structured case simulations, but lacks nuanced judgment |

| Academic Writing | 1 (Zhao 2024 RCT) | RCT | Low | N/A | Low | Moderate | Unclear | Moderate | Promising benefit for structured learning; needs replication |

| Retention & Learning | 1 (Jiang 2024 RCT) | RCT | Low | N/A | Low | Moderate | Unclear | Moderate | Suggests immediate knowledge gain; long-term retention unknown |

| Risks / Ethics | 5+ (across studies) | Narrative/Observational | Moderate | N/A | Low | N/A | Likely | Low | Ethical and accuracy risks consistently noted; empirically under-researched |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).