Submitted:

19 September 2025

Posted:

22 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Colorimetric Analysis

2.3. Marbling

2.4. Lipid Extraction and Fatty Acid Analysis

2.5. Tenderness

2.6. Statistical Analysis

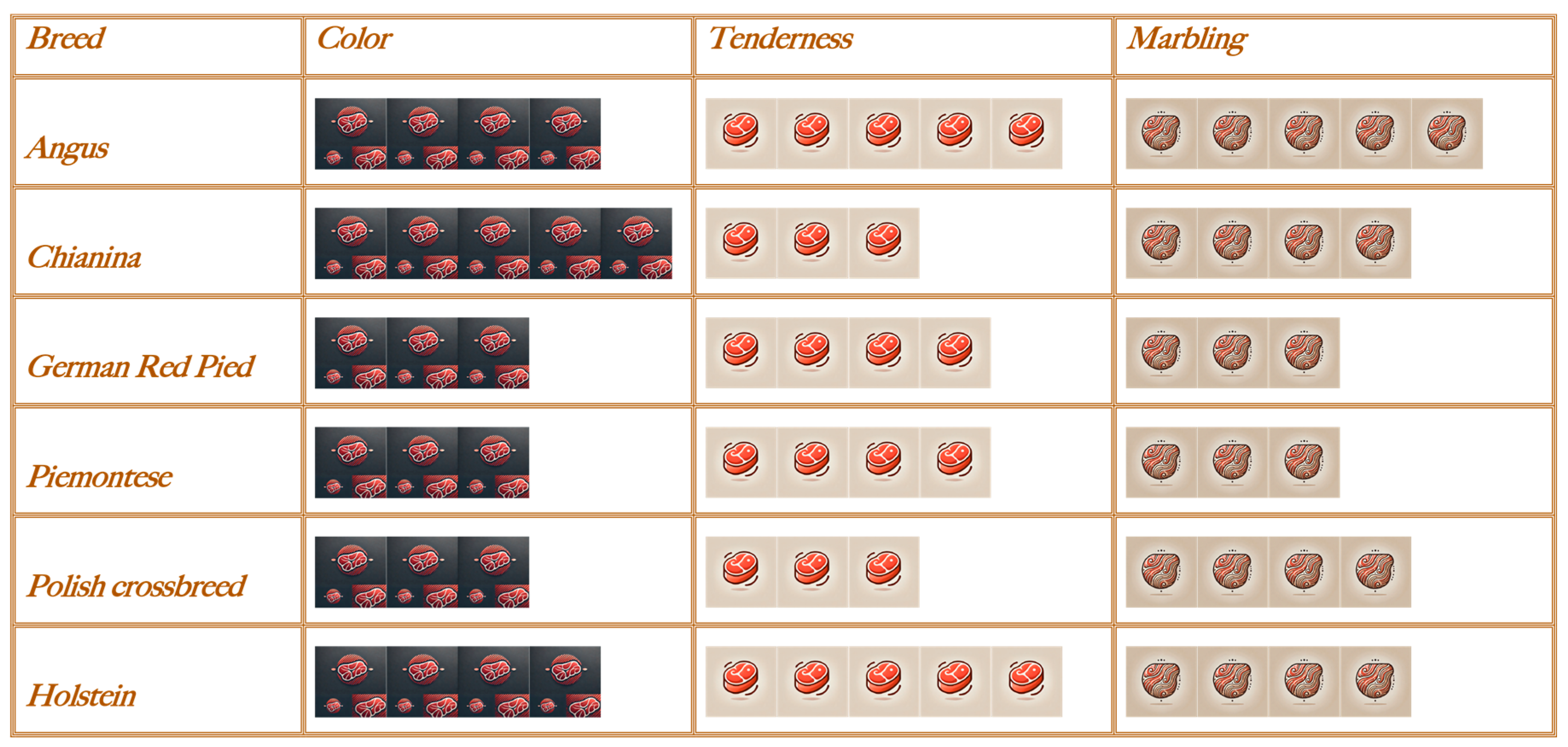

2.7. Labelling System

3. Results

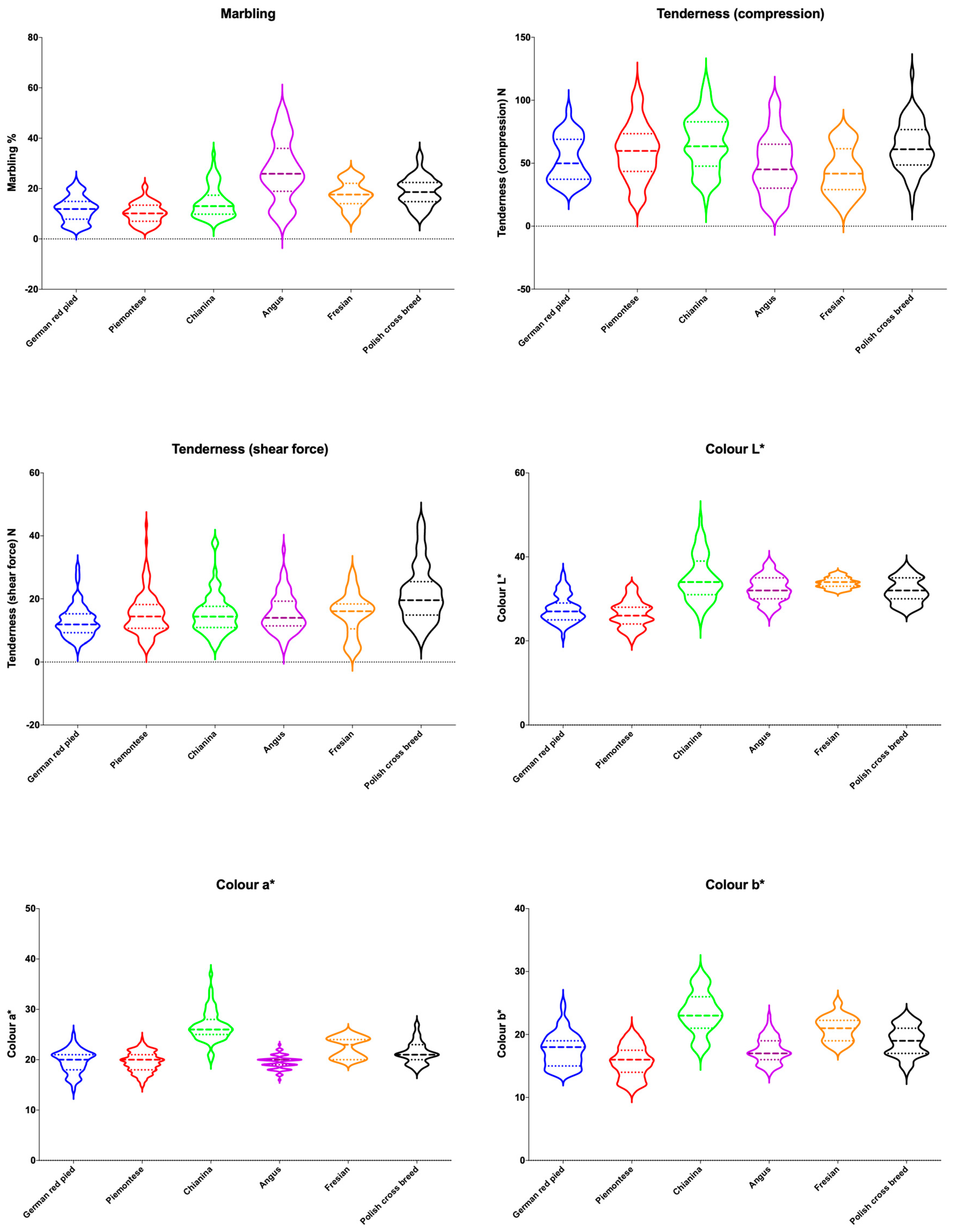

3.1. Colorimetric Analysis

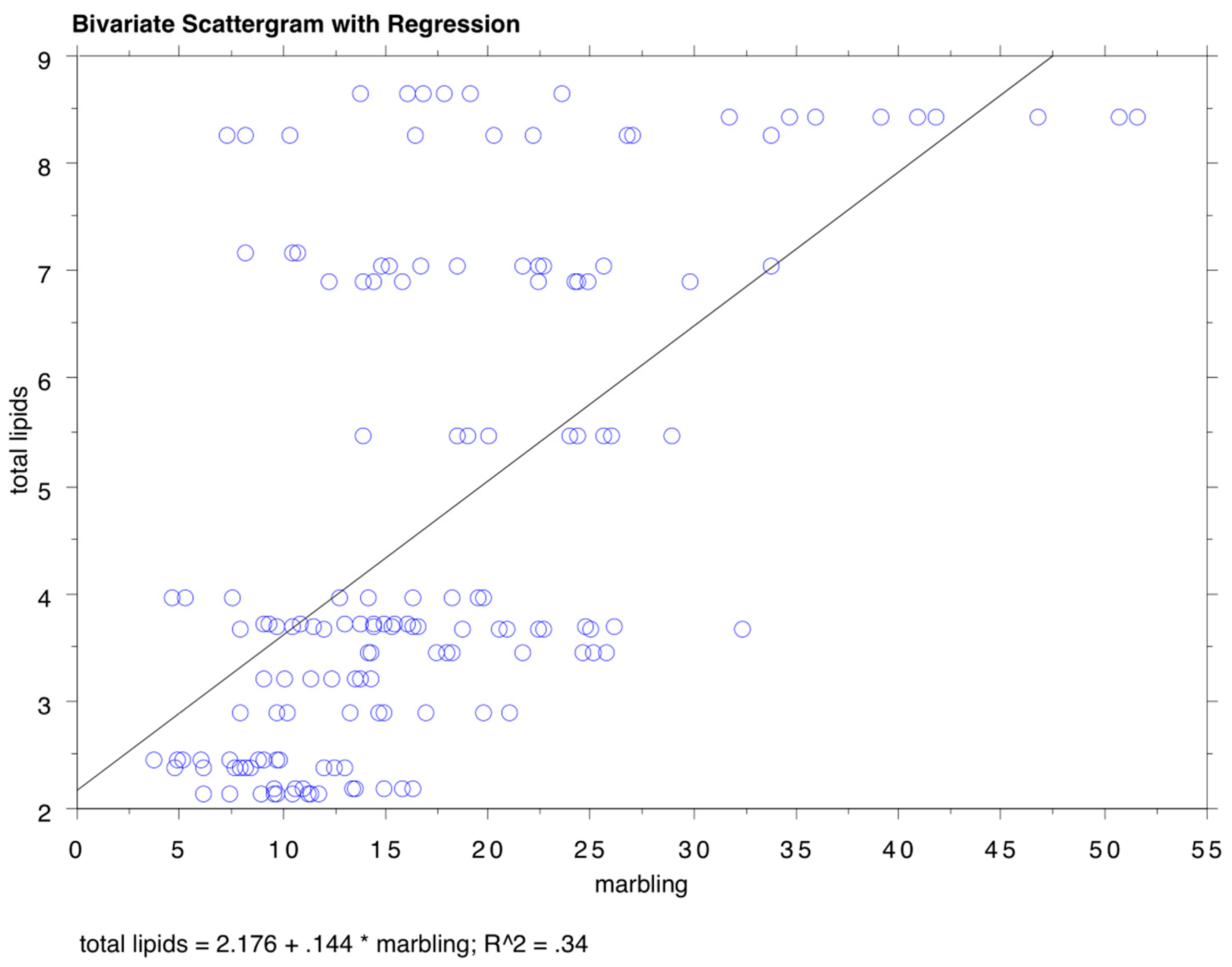

3.2. Marbling, Total Lipids and Fatty Acids Profile

3.3. Tenderness

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, J., et al. Consumer Perception of Beef Quality and How to Control, Improve and Predict It? Focus on Eating Quality. Foods (Basel, Switzerland) 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Anonymus. Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on the provision of food information to consumers. 2011.

- Shi, Y., et al. A Review on Meat Quality Evaluation Methods Based on Non-Destructive Computer Vision and Artificial Intelligence Technologies. Food Sci Anim Resour 2021, 41, 563-588. [CrossRef]

- Hocquette, J.F., et al. Opportunities for predicting and manipulating beef quality. Meat Sci 2012, 92, 197-209. [CrossRef]

- Raulet, M., et al. Construction of beef quality through official quality signs, the example of Label Rouge. Animal 2022, 16 Suppl 1, 100357. [CrossRef]

- Bernués, A., et al. Labelling information demanded by European consumers and relationships with purchasing motives, quality and safety of meat. Meat Science 2003, 65, 1095-1106. [CrossRef]

- Gellynck, X., et al. Pathways to increase consumer trust in meat as a safe and wholesome food. Meat Sci 2006, 74, 161-171. [CrossRef]

- Stranieri, S.; Banterle, A. Consumer Interest in Meat Labelled Attributes: Who Cares? International Food and Agribusiness Management Review 2015, 18, 21-38.

- Allen, P. Recent developments in the objective measurement of carcass and meat quality for industrial application. Meat Sci 2021, 181, 108601. [CrossRef]

- Mateescu, R.G., et al. Strategies to predict and improve eating quality of cooked beef using carcass and meat composition traits in Angus cattle. Journal of animal science 2016, 94, 2160-2171. [CrossRef]

- Anonymus. Requirements for grading terms on meat product labeling. USDA, U.S.D.o.A., Ed. USDA: Washington, DC 20250 2018.

- Grunert, K.G., et al. Consumer perception of meat quality and implications for product development in the meat sector—a review. Meat Science 2004, 66, 259-272. [CrossRef]

- Pethick, D., et al. Improving the nutritional, sensory and market value of meat products from sheep and cattle. Animal 2021, 15, 100356.

- Gagaoua, M., et al. Reverse phase protein arrays for the identification/validation of biomarkers of beef texture and their use for early classification of carcasses. Food Chemistry 2018, 250, 245-252. [CrossRef]

- Xie, X., et al. Effect of cattle breed on meat quality, muscle fiber characteristics, lipid oxidation and Fatty acids in china. Asian-Australasian journal of animal sciences 2012, 25, 824-831. [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.C., et al. Economic implications of improved color stability in beef. Antioxidants in muscle foods nutritional strategies to improve quality 2000, 397-426.

- Ardeshiri, A.; Rose, J.M. How Australian consumers value intrinsic and extrinsic attributes of beef products. Food Quality and Preference 2018, 65, 146-163. [CrossRef]

- Emerson, M.R., et al. Effectiveness of USDA instrument-based marbling measurements for categorizing beef carcasses according to differences in longissimus muscle sensory attributes. Journal of animal science 2013, 91, 1024-1034. [CrossRef]

- Hunt, M.R., et al. Consumer assessment of beef palatability from four beef muscles from USDA Choice and Select graded carcasses. Meat Science 2014, 98, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Corbin, C.H., et al. Sensory evaluation of tender beef strip loin steaks of varying marbling levels and quality treatments. Meat Sci 2015, 100, 24-31. [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, M., et al. Fat Deposition and Fat Effects on Meat Quality-A Review. Animals : an open access journal from MDPI 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Warner, R.D., et al. Meat tenderness: advances in biology, biochemistry, molecular mechanisms and new technologies. Meat Science 2022, 185, 108657. [CrossRef]

- Warner, R., et al. Meat Tenderness: Underlying Mechanisms, Instrumental Measurement, and Sensory Assessment. Meat and Muscle Biology 2021, 4. [CrossRef]

- Crapnell, R.D.; Banks, C.E. Electroanalytical overview: the pungency of chile and chilli products determined via the sensing of capsaicinoids. Analyst 2021, 146, 2769-2783. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.-M., et al. The relationship between Scoville Units and the suprathreshold intensity of sweeteners and Sichuan pepper oleoresins. Journal of Sensory Studies 2021, 36, e12699. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y., et al. Multi-dimensional pungency and sensory profiles of powder and oil of seven chili peppers based on descriptive analysis and Scoville heat units. Food Chemistry 2023, 411, 135488. [CrossRef]

- McClure, A.P., et al. Optimizing consumer acceptability of 100% chocolate through roasting treatments and effects on bitterness and other important sensory characteristics. Current Research in Food Science 2022, 5, 167-174. [CrossRef]

- Grispoldi, L., et al. A study on the application of natural extracts as alternatives to sodium nitrite in processed meat. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation 2022, 46, e16351. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W., et al. Marbling Analysis for Evaluating Meat Quality: Methods and Techniques. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2015, 14, 523-535. [CrossRef]

- Lee, B., et al. Comparison of marbling fleck characteristics between beef marbling grades and its effect on sensory quality characteristics in high-marbled Hanwoo steer. Meat Science 2019, 152, 109-115. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S., et al. Determination of Intramuscular Fat Content in Beef using Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Journal- Faculty of Agriculture Kyushu University 2015, 60, 157-162. [CrossRef]

- D'Arco, G., et al. Composition of meat and offal from weaned and fattened rabbits and results of stereospecific analysis of triacylglycerols and phosphatidylcholines. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2012, 92, 952-959. [CrossRef]

- Maurelli, S., et al. Enzymatic Synthesis of Structured Triacylglycerols Containing CLA Isomers Starting from sn-1,3-Diacylglycerols. Journal of the American Oil Chemists' Society 2009, 86, 127-133. [CrossRef]

- Piccinetti, C.C., et al. Malnutrition may affect common sole (Solea solea L.) growth, pigmentation and stress response: Molecular, biochemical and histological implications. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology 2012, 161, 361-371. [CrossRef]

- Bonny, S., et al. Chapter 10 - Quality Assurance Schemes in Major Beef-Producing Countries. In New Aspects of Meat Quality, Purslow, P.P., Ed. Woodhead Publishing: 2017. pp. 223-255. [CrossRef]

- Motoyama, M., et al. Wagyu and the factors contributing to its beef quality: A Japanese industry overview. Meat Science 2016, 120, 10-18. [CrossRef]

- Sakowski, T., et al. Genetic and Environmental Determinants of Beef Quality-A Review. Front Vet Sci 2022, 9, 819605. [CrossRef]

- Papanikolopoulou, V., et al. Impact of Breed and Slaughter Hygiene on Beef Carcass Quality Traits in Northern Greece. Foods (Basel, Switzerland) 2025, 14. [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Jiang, H. Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Intramuscular Fat Development and Growth in Cattle. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Kostusiak, P., et al. Relationship between Beef Quality and Bull Breed. In Animals, 2023; Vol. 13.

- Park, S.J., et al. Genetic, management, and nutritional factors affecting intramuscular fat deposition in beef cattle - A review. Asian-Australasian journal of animal sciences 2018, 31, 1043-1061. [CrossRef]

- Tyra, M., et al. Association between subcutaneous and intramuscular fat content in porcine ham and loin depending on age, breed and FABP3 and LEPR genes transcript abundance. Mol Biol Rep 2013, 40, 2301-2308. [CrossRef]

- Ramani, A., et al. Comparative analysis of fatty acid profiles in indigenous cattle breeds: A comprehensive evaluation. . Int. J. Adv. Biochem. Res. 2024, 8, 378-381. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T., et al. Fatty Acid Profile of Muscles from Crossbred Angus-Simmental, Wagyu-Simmental, and Chinese Simmental Cattles. Food Sci Anim Resour 2020, 40, 563-577. [CrossRef]

- Pannier, L., et al. Prediction of chemical intramuscular fat and visual marbling scores with a conveyor vision scanner system on beef portion steaks. Meat Science 2023, 199, 109141. [CrossRef]

- Konarska, M., et al. Relationships between marbling measures across principal muscles. Meat Science 2017, 123, 67-78. [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.D., et al. Fat deposition, fatty acid composition and meat quality: A review. Meat Science 2008, 78, 343-358. [CrossRef]

- Warren, H.E., et al. Effects of breed and a concentrate or grass silage diet on beef quality in cattle of 3 ages. I: Animal performance, carcass quality and muscle fatty acid composition. Meat Sci 2008, 78, 256-269. [CrossRef]

- Brugiapaglia, A., et al. Fatty acid profile and cholesterol content of beef at retail of Piemontese, Limousin and Friesian breeds. Meat Sci 2014, 96, 568-573. [CrossRef]

- Choe, J.H., et al. Estimation of Sensory Pork Loin Tenderness Using Warner-Bratzler Shear Force and Texture Profile Analysis Measurements. Asian-Australasian journal of animal sciences 2016, 29, 1029-1036. [CrossRef]

- Warner, R., et al. Meat Tenderness: Underlying Mechanisms, Instrumental Measurement, and Sensory Assessment. Meat and Muscle Biology 4(2), 17, 2021, 4, 1–25.

- Herrera, N.J., et al. The Relationship between Marbling, Superoxide Dismutase, and.

- Beef TendernessBeef Tenderness. Nebraska Beef Cattle Reports 2018.

- Benli, H.; Yildiz, D.G. Consumer perception of marbling and beef quality during purchase and consumer preferences for degree of doneness. Anim Biosci 2023, 36, 1274-1284. [CrossRef]

- Conter, M. Recent advancements in meat traceability, authenticity verification, and voluntary certification systems. Italian journal of food safety 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Špehar, M., et al. Beef quality: factors affecting tenderness and marbling. Stočarstvo 2008, 62, 463-478.

- Silva, D.R.G., et al. Comparison of Warner-Bratzler shear force values between round and square cross-section cores for assessment of beef Longissimus tenderness. Meat Science 2017, 125, 102-105. [CrossRef]

- Marrone, R., et al. Effects of Feeding and Maturation System on Qualitative Characteristics of Buffalo Meat (Bubalus bubalis). Animals 2020, 10, 899.

- Smaldone, G., et al. Microbiological, rheological and physical-chemical characteristics of bovine meat subjected to a prolonged ageing period. Italian journal of food safety 2019, 8, 8100. [CrossRef]

- Brewer, M.S., et al. Measuring pork color: effects of bloom time, muscle, pH and relationship to instrumental parameters. Meat Sci 2001, 57, 169-176. [CrossRef]

- Corlett, M.T., et al. Consumer Perceptions of Meat Redness Were Strongly Influenced by Storage and Display Times. Foods (Basel, Switzerland) 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Renerre, M. Biochemical Basis of Fresh Meat Color: Review. In Proceedings of Proceedings of the 45th International Congress of Meat Science and Technology; pp. 344-352.

- Cenci-Goga, B.T., et al. New Trends in Meat Packaging. Microbiology Research 2020, 11, 56-67.

- O'Brien, K.D., et al. The Meat of the Matter: The Effect of Science-based Information on Consumer Perception of Grass-fed Beef. Journal of Applied Communications 2003, 107.

| from slaughter to cutting/packaging | from cutting/packaging to arrival at the lab | from arrival to analysis | from packaging to analysis | ||||||||

| mean | sd | mean | sd | mean | sd | mean | sd | ||||

| Angus (n = 7 shipments) | 4,29 | 1,70 | 26,71 | 44,01 | 9,00 | 2,65 | 35,71 | sd | |||

| Chianina (n = 7 shipments) | 5,00 | 1,15 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 9,00 | 0,00 | 9,00 | 42,90 | |||

| German Red Pied (n = 7 shipments) | 3,86 | 1,68 | 3,43 | 1,40 | 7,71 | 0,49 | 11,14 | 0,00 | |||

| Piemontese(n = 13 shipments) | 3,77 | 0,83 | 3,08 | 1,44 | 6,92 | 1,85 | 10,00 | 1,35 | |||

| Polish crossbreed (n = 7 shipments) | 3,71 | 1,25 | 0,57 | 0,53 | 12,00 | 0,00 | 12,57 | 1,15 | |||

| Holstein (n = 2 shipments) | 4,00 | 0,00 | 1,00 | 0,00 | 7,50 | 4,95 | 8,50 | 0,53 | |||

| L* | a* | b* | ||||||||||

| mean | sd | min | max | mean | sd | min | max | mean | sd | min | max | |

| Angus | 32,33 b | 3,05 | 26,00 | 39,00 | 19,46 c | 1,35 | 16,00 | 23,00 | 17,54 c | 2,04 | 14,00 | 23,00 |

| Chianina | 34,79 b | 5,30 | 25,00 | 49,00 | 26,64 a | 3,02 | 20,00 | 37,00 | 23,49 b | 3,24 | 17,00 | 30,00 |

| Holstein | 33,78 b | 1,26 | 32,00 | 36,00 | 22,44 b | 2,04 | 20,00 | 25,00 | 21,00 bd | 1,94 | 18,00 | 25,00 |

| German Red Pied | 27,64 a | 3,24 | 21,00 | 36,00 | 19,71 c | 2,30 | 14,00 | 25,00 | 17,57 c | 2,61 | 14,00 | 25,00 |

| Piemontese | 26,39 a | 3,18 | 20,00 | 33,00 | 19,55 c | 1,93 | 15,00 | 24,00 | 15,59 a | 2,48 | 11,00 | 21,00 |

| Polish crossbreed | 31,89 b | 2,95 | 27,00 | 38,00 | 21,37 b | 2,11 | 18,00 | 27,00 | 18,92 cd | 2,33 | 14,00 | 23,00 |

| tenderness (compression)1 | tenderness (shear force)1 | |||||||||||

| mean | sd | min | max | mean | sd | min | max | |||||

| Angus | 48,04 a | 23,30 | 11,90 | 99,90 | 15,42 b | 6,12 | 4,20 | 35,65 | ||||

| Chianina | 66,18 b | 21,61 | 20,70 | 115,80 | 15,24 b | 6,49 | 4,90 | 37,90 | ||||

| Holstein | 43,44 ac | 18,75 | 14,60 | 73,05 | 15,26 ab | 6,63 | 3,35 | 27,50 | ||||

| German Red Pied | 53,35 acd | 17,77 | 27,85 | 93,80 | 12,98 b | 5,16 | 3,95 | 30,25 | ||||

| Piemontese | 59,23 bc | 22,17 | 15,65 | 114,15 | 15,22 b | 6,69 | 4,00 | 43,55 | ||||

| Polish crossbreed | 63,23 bd | 18,71 | 20,55 | 121,45 | 21,62 a | 8,86 | 7,45 | 44,20 | ||||

| marbling2 | total lipids3 | |||||||||||

| mean | sd | min | max | mean | sd | min | max | |||||

| Angus | 27,01 b | 12,09 | 6,12 | 51,54 | 5,35 bc | 2,61 | 2,15 | 8,43 | ||||

| Chianina | 14,60 cd | 6,28 | 5,69 | 33,70 | 6,30 b | 1,94 | 3,72 | 8,27 | ||||

| Holstein | 17,51 bc | 5,18 | 8,13 | 25,73 | 5,81 b | 2,48 | 3,45 | 8,65 | ||||

| German Red Pied | 11,80 ad | 4,96 | 3,74 | 22,80 | 3,09 ac | 0,67 | 2,40 | 3,97 | ||||

| Piemontese | 10,23 a | 4,05 | 3,00 | 21,41 | 2,63 a | 0,44 | 2,20 | 3,22 | ||||

| Polish crossbreed | 18,83b | 5,75 | 7,93 | 33,72 | 4,81b | 1,62 | 3,68 | 7,05 | ||||

| Angus | Chianina | German Red Pied | Piemontese | Polish crossbreed | Holstein | |||||||||||||||||||

| mean | sd | min | max | mean | sd | min | max | mean | sd | min | max | mean | sd | min | max | mean | sd | min | max | mean | sd | min | max | |

| C14:0 | 1,81 | 0,46 | 1,39 | 2,3 | 2,11 | 0,52 | 1,59 | 2,63 | 1,27 | 0,15 | 1,13 | 1,43 | 1,91 | 0,55 | 1,37 | 2,46 | 2,17 | 0,18 | 1,96 | 2,28 | 2,64 | 0,39 | 2,2 | 2,96 |

| C14:1 | 0,37 | 0,3 | 0,18 | 0,71 | 0,45 | 0,07 | 0,4 | 0,53 | 0,25 | 0,03 | 0,22 | 0,28 | 0,49 | 0,1 | 0,38 | 0,56 | 0,33 | 0,03 | 0,31 | 0,37 | 0,36 | 0,02 | 0,35 | 0,38 |

| C15:0 | 0,44 | 0,22 | 0,27 | 0,69 | 0,7 | 0,15 | 0,54 | 0,84 | 0,44 | 0,12 | 0,34 | 0,58 | 0,43 | 0,18 | 0,23 | 0,57 | 0,33 | 0,13 | 0,24 | 0,48 | 0,45 | 0,01 | 0,44 | 0,46 |

| C15:1 | 0,17 | 0,04 | 0,14 | 0,21 | 0,26 | 0,1 | 0,19 | 0,37 | 0,16 | 0,01 | 0,15 | 0,16 | 0,17 | 0,06 | 0,11 | 0,22 | 0,15 | 0,06 | 0,11 | 0,22 | 0,16 | 0,01 | 0,15 | 0,17 |

| C16:0 | 24,3 | 1,29 | 23,4 | 25,8 | 24,7 | 4,92 | 20,6 | 30,2 | 22,7 | 1,6 | 21,3 | 24,5 | 25 | 2,96 | 21,8 | 27,6 | 25,4 | 2,37 | 23 | 27,7 | 25,9 | 0,54 | 25,4 | 26,4 |

| C16:1n-9 | 0,26 | 0,05 | 0,21 | 0,31 | 0,28 | 0,02 | 0,26 | 0,3 | 0,24 | 0,02 | 0,22 | 0,26 | 0,23 | 0,09 | 0,15 | 0,33 | 0,17 | 0,03 | 0,14 | 0,2 | 0,28 | 0,03 | 0,25 | 0,31 |

| C16:1n-7 | 3,21 | 0,77 | 2,71 | 4,1 | 2,96 | 0,44 | 2,46 | 3,25 | 3,09 | 0,11 | 3,03 | 3,22 | 4,29 | 0,55 | 3,7 | 4,78 | 3,13 | 0,19 | 2,99 | 3,34 | 2,82 | 0,39 | 2,44 | 3,22 |

| C17:0 | 0,97 | 0,22 | 0,82 | 1,22 | 1,26 | 0,25 | 0,97 | 1,41 | 0,93 | 0,18 | 0,76 | 1,12 | 0,75 | 0,16 | 0,57 | 0,85 | 0,69 | 0,34 | 0,44 | 1,07 | 0,79 | 0,08 | 0,7 | 0,84 |

| C17:1 | 1,11 ab | 0,18 | 0,91 | 1,23 | 1,19 ab | 0,29 | 0,96 | 1,52 | 1,62 b | 0,09 | 1,56 | 1,73 | 1,02 ab | 0,08 | 0,93 | 1,08 | 0,79 ab | 0,32 | 0,56 | 1,16 | 0,62 a | 0,09 | 0,53 | 0,71 |

| C18:0 | 15,8 | 2,41 | 13,9 | 18,5 | 18,2 | 2,04 | 16,3 | 20,4 | 14,4 | 1,16 | 13,1 | 15,1 | 12,8 | 1,21 | 11,5 | 13,9 | 12,5 | 1,62 | 11,2 | 14,4 | 16,6 | 0,77 | 15,9 | 17,4 |

| C18:1 trans | 1,19 | 0,74 | 0,51 | 1,98 | 0,96 | 0,55 | 0,32 | 1,29 | 0,83 | 0,23 | 0,57 | 1 | 0,73 | 0,15 | 0,56 | 0,83 | 0,71 | 0,24 | 0,46 | 0,93 | 1,15 | 0,4 | 0,73 | 1,53 |

| C18:1n-9 + n7 | 35,9 ab | 5,2 | 31 | 41,3 | 33,3 ab | 2,57 | 30,9 | 36 | 40 b | 3,04 | 36,5 | 42,1 | 33,5 ab | 4,53 | 30 | 38,6 | 30,5 ab | 1,87 | 29 | 32,6 | 27,7 a | 0,95 | 26,6 | 28,4 |

| C18:2n6 | 7,87 | 1,26 | 6,47 | 8,9 | 10,1 | 4,89 | 4,7 | 14,3 | 6,02 | 1,67 | 4,87 | 7,94 | 10,2 | 3,42 | 7,39 | 14 | 13,8 | 3,65 | 9,68 | 16,7 | 15,7 | 1,48 | 14,7 | 17,4 |

| C18:3n3 | 1,21 | 0,76 | 0,33 | 1,65 | 0,59 | 0,19 | 0,44 | 0,8 | 1,59 | 0,63 | 1,23 | 2,32 | 0,92 | 0,4 | 0,48 | 1,27 | 0,88 | 0,75 | 0,41 | 1,74 | 0,71 | 0,21 | 0,57 | 0,95 |

| 9c, 11t CLA | 0,28 | 0,04 | 0,24 | 0,32 | 0,24 | 0,14 | 0,12 | 0,39 | 0,22 | 0,01 | 0,21 | 0,23 | 0,21 | 0,06 | 0,16 | 0,27 | 0,15 | 0,01 | 0,14 | 0,15 | 0,34 | 0,17 | 0,15 | 0,46 |

| C20:1 | 0,23 | 0,04 | 0,18 | 0,26 | 0,23 | 0,17 | 0,12 | 0,43 | 0,22 | 0,07 | 0,15 | 0,29 | 0,18 | 0,05 | 0,13 | 0,23 | 0,13 | 0,01 | 0,12 | 0,13 | 0,12 | 0,04 | 0,1 | 0,17 |

| 20:3n6 | 0,86 | 0,14 | 0,74 | 1,02 | 0,61 | 0,03 | 0,58 | 0,64 | 0,89 | 0,39 | 0,6 | 1,33 | 1,14 | 0,52 | 0,72 | 1,73 | 1,64 | 0,99 | 0,56 | 2,49 | 0,55 | 0,12 | 0,44 | 0,67 |

| C20:4n6 | 2,62 | 1,1 | 1,83 | 3,88 | 1,57 | 0,73 | 1,03 | 2,4 | 2,43 | 1,38 | 1,38 | 3,99 | 3,73 | 2,54 | 2,13 | 6,66 | 5,56 | 3,04 | 2,34 | 8,38 | 2,56 | 0,29 | 2,25 | 2,81 |

| C20:5 n3 | 0,53 | 0,37 | 0,22 | 0,93 | 0,08 | 0,07 | 0 | 0,13 | 0,85 | 0,58 | 0,45 | 1,52 | 0,67 | 0,43 | 0,29 | 1,14 | 0,24 | 0,15 | 0,11 | 0,41 | 0,12 | 0,05 | 0,08 | 0,17 |

| C22:5n3 | 0,86 | 0,62 | 0,37 | 1,55 | 0,2 | 0,18 | 0 | 0,33 | 1,51 | 1 | 0,73 | 2,64 | 1,44 | 1,26 | 0,47 | 2,87 | 0,7 | 0,32 | 0,39 | 1,03 | 0,4 | 0,16 | 0,27 | 0,58 |

| C22:6n3 | 0,05 | 0,08 | 0 | 0,14 | 0,01 | 0,01 | 0 | 0,02 | 0,35 | 0,34 | 0,12 | 0,74 | 0,22 | 0,17 | 0,09 | 0,42 | 0,05 | 0,04 | 0 | 0,08 | 0,03 | 0,04 | 0 | 0,08 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).