1. Introduction

Eutectic solidification, a fundamental liquid-solid transformation, governs microstructural evolution in numerous industrial alloys and inorganic materials [

1,

2]. The regularity of eutectic morphology critically determines mechanical properties, particularly in self-reinforced composites where precise phase orientation is required [

3]. Consequently, characterizing structural transitions between regular and anomalous eutectics remains central to solidification theory [

4,

5]. Under non-equilibrium conditions, hypoeutectic/hypereutectic alloys may suppress primary phases to form fully eutectic structures, while regular systems can transition to anomalous eutectics [

6,

7]. Such transitions—observed in Ag-Cu [

8], Ni-Sn [

9], Co-Sn [

10], and other systems—are predicted by the Trivedi-Magnin-Kurz (TMK) model to occur when growth velocity exceeds a critical threshold, leading to decoupled phase growth [

11,

12]. For Ni-Sn alloys specifically, anomalous eutectic dominate in deep undercooling studies [

13,

14,

15], where rapid recalescence generates ultrahigh cooling rates. However, this method intrinsically couple’s temperature gradient (

G) and growth velocity (

V), preventing independent control of these key parameters. This limitation obscures the individual roles of

G and

V in microstructural transitions, hindering mechanistic understanding of anomalous eutectic formation.

Bridgman directional solidification process, as an effective method to study the microstructure of alloys and the relationship between their solidification parameters, can offer a solution by decoupling

G and

V during the solidification process [

16,

17]. Therefore, the accurate Bridgman directional solidification process may reveal the formation mechanism of anomalous eutectic, and can clarify the multi-factor influence of deep undercooling experiment [

18,

19]. This process explores the evolution of non-equilibrium solidification eutectic growth morphology [

20]. For example, Cui et al. [

21] prepared Fe-Al-Ta eutectic composites by a modified Bridgman directional solidification technique. Solidification microstructure transforms from regular eutectic to eutectic colony with the increase of the solidification rate. The solid/liquid interface of Fe-Al-Ta eutectic evolves from planar interface to cellular interface with the increase of the solidification rate. Corresponding, the existing Bridgman studies on Ni-Sn alloys also primarily focus on steady-state growth, reporting only regular lamellar/rod structures at high solidification rate [

22]. This contrasts sharply with the ubiquitous anomalous eutectics in deep-undercooled Ni-Sn, suggesting a fundamental gap: under what kinetic conditions anomalous eutectic can form in directional solidification [

23,

24]. Recent work on Ag-Cu [

25] suggests that thermal/diffusional instabilities—not impurities—trigger morphological transitions. The transition may require dynamic interface destabilization rather than steady-state growth. Nevertheless, systematic studies linking velocity perturbations to anomalous eutectic formation in Ni-Sn alloys remain absent.

To address this, Bridgman velocity-jump experiments are integrated with cellular automaton (CA) simulations. Using Ni-Sn alloys (hypoeutectic to hypereutectic), this work demonstrates: Steady-state growth (0.1–2000 μm/s) preserves regular eutectics, confirming prior observations. Velocity transitions dynamically destabilize the solid-liquid interface, inducing localized anomalous eutectics. A distinct process window exists for anomalous formation, reconciling directional solidification with deep undercooling phenomena. This work establishes controlled velocity jumps as a novel pathway to probe non-equilibrium eutectic transitions, bridging the gap between classical solidification theory and rapid solidification regimes.

2. Materials and Methods

Ni-30wt.%Sn (hypoeutectic), Ni-32.5wt.%Sn (eutectic), and Ni-33wt.%Sn (hypereutectic) alloys were prepared from high-purity Ni (>99.99%) and Sn (>99.99%) in a vacuum induction furnace (<10⁻¹ Pa). Cast ingots were machined into Φ7 mm rods. Experiments used a vacuum Bridgman furnace with key capabilities: heating to 1400 °C, drawing speeds (0.1–2000 μm/s) and high vacuum (5×10⁻⁴ Pa). Experiment schemes of Ni-Sn alloys by Bridgman directional solidification are shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2. Samples underwent preset velocity profiles, followed by quenching in ternary low melting point Ga-In-Sn liquid alloy with good thermal conductivity. Longitudinal sections were polished and etched (aqua regia, HNO₃:HCl = 1:3). Microstructures were analyzed using Olympus GX71 optical microscopy and ZEISS ΣIGMA HD SEM. The CA modeled eutectic growth during velocity jumps (1s transition from 0.1 μm/s to 1000 μm/s), initial eutectic lamellar spacing λ = 0.5 μm, and

G = 2.5×10

4 K/m.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Microstructural Morphology of Ni-Sn Alloys Under Different Drawing Speeds

3.1.1. Ni-30wt.%Sn Hypoeutectic Alloy

Figure 1 presents the microstructural morphology of the Ni-30wt.%Sn hypoeutectic alloy solidified under Bridgman directional solidification conditions at various drawing speeds.

Figure 1(a) depicts the microstructure at the initial drawing speed of 0.1 μm/s. Near-spherical black regions correspond to the primary α-Ni phase. Each primary particle is enveloped by regular lamellar/rod-like eutectic, and some primary α-Ni particles exhibit interconnection.

Figure 1(b) shows the microstructure obtained at a constant drawing speed of 1000 μm/s. The primary phase adopts an equiaxed dendritic morphology. A thin white halo of Ni₃Sn surrounds the primary α-Ni dendrites, while the interdimeric regions are filled with regular lamellar α-Ni + Ni₃Sn eutectic. Changes in the undercooling ahead of the solid-liquid interface during solidification critically influence crystallization. Generally, planar growth occurs in the absence of constitutional undercooling. The presence of constitutional undercooling induces a sequential transition in growth morphology: cellular

→ columnar

→ equiaxed [

26]. As the drawing speed increases, the volume fraction of the higher-melting-point α-Ni phase increases, leading to solute enrichment (primarily lower-melting-point Ni₃Sn) in the liquid. This enrichment lowers the actual crystallization temperature at the interface, initiating constitutional undercooling. The onset of constitutional undercooling promotes the formation of α-Ni as cellular crystals. With further increases in drawing speed, the α-Ni phase develops a columnar dendritic morphology, ultimately transitioning to an equiaxed dendritic structure.

3.1.2. Ni-32.5wt.%Sn Eutectic Alloy

Figure 2 illustrates the microstructural morphology of Ni-32.5wt.%Sn eutectic alloy directionally solidified using the Bridgman technique at different drawing speeds. As shown in

Figure 2(a), under a constant drawing speed of 1000 μm/s, the microstructure consists of regular lamellae. Increasing the drawing speed to 2000 μm/s results in a more complex morphology due to differing eutectic colony orientations; however, the overall eutectic structure remains lamellar, as evidenced in

Figure 2(b). Notably, under steady-state constant drawing speeds, the Bridgman directionally solidified Ni-Sn eutectic alloy did not exhibit anomalous eutectic structures similar to those observed in deeply undercooled or laser-remelted Ni-Sn alloys.

The formation of eutectic colonies has been extensively studied. The impurity elements significantly influence morphological transitions in eutectic alloys. Impurity elements can induce a substantial region of constitutional undercooling ahead of the solid-liquid interface [

27]. The resulting solute concentration gradient perpendicular to the interface destabilizes the planar interface, promoting a transition to cellular growth and the formation of eutectic colonies/cells. Yamauchi [

28] demonstrated that minor additions of Mn and Co elements can alter the microstructure of directionally solidified Fe-Si eutectic alloys. Furthermore, severe segregation of a third element combined with a low ratio of

G to

V can even lead to dendritic eutectic structures. Zhao et al. [

29] also observed cellular eutectic during their studies on undercooled solidification of Ag-Cu eutectic alloys. They emphasized that high-purity starting materials were used, effectively ruling out impurity-induced cellular interface formation. They proposed that the large difference in composition between two eutectic phases and the very large thermal diffusion coefficient of the liquid should be responsible for the cellular growth of lamellar eutectics at low undercoolings. It has been found that during growth of a eutectic alloy, an increase in the growth velocity will trigger instability of the solid/liquid interface because of the occurrence of constitutional undercooling in front of the interface, which can lead to eutectic cells [

30].

3.1.3. Ni-33wt.%Sn Hypereutectic Alloy

The microstructural morphology of directionally solidified Ni-33wt.%Sn hypereutectic alloy at different drawing speeds is shown in

Figure 3. During solidification of the hypereutectic Ni-33wt.%Sn alloy, the primary Ni₃Sn phase precipitates first. The near-spherical white structures in

Figure 3(a) represent the primary Ni₃Sn phase. However, increased in drawing speed significantly alters the morphology of primary Ni

3Sn phase.

Figure 3(b) shows the microstructure resulting from a drawing speed of 500 μm/s. Here, the white "dendrite trunks" are composed of interconnected near-spherical primary Ni₃Sn particles. Lamellar and rod-like eutectic structures grow epitaxially along these trunks, exhibiting specific orientations. When the drawing speed increased to 1000 μm/s, the trunk morphology gradually evolved towards a linear form, as seen in

Figure 3(c). The microstructure is similar to the feathery lamellar eutectic grain when the Ni-32.5wt%Sn eutectic alloy was undercooled below 100K. Wei et al. believed that the alternating α-Ni and Ni

3Sn lamellae both originated from a primary Ni

3Sn twin plate [

31].

Statistical analysis revealed that with the increase of drawing speed, the width of the primary Ni₃Sn phase decreased progressively from an initial 28 μm to 20 μm, and ultimately to a linear structure approximately 7 μm. The eutectic lamellar spacing λ decreased from an initial approximately 3 μm to 1.5 μm,and ultimately 0.5μm when the drawing speed was 1000μm/s. Under constant drawing speed of 1000μm/s, the eutectic structure tended towards regular lamellar/rod-like morphology, with no anomalous eutectic observed. In conclusion, as the drawing speed increased, the characteristic scale of the microstructure gradually became finer.

3.2. Effect of Transition Variable Speed on Ni-Sn Eutectic Microstructural Morphology

3.2.1. Microstructural morphology at the transition interface in Ni-30wt.%Sn hypoeutectic alloy

Figure 4 depicts the microstructure evolution of Ni-30wt.%Sn hypoeutectic alloy during directional solidification with transition variable speed between 0.1 μm/s and 1000 μm/s.

Figure 4(a) shows the interface region, where primary α-Ni dendrites transition from fine to coarse, accompanied by a significant increase in primary dendritic arm spacing. The primary dendritic arm spacing changed approximately from 40 μm to 55 μm.

Figure 4(b) reveals that the interdimeric eutectic structure transforms from regular lamellar to rod-like morphology. This indicates a jump from a high to a low growth rate at this interface.

Figure 4(c) shows another interface formed by a rate jump. The left side exhibits rod-like eutectic, while the right side displays regular lamellar eutectic. Crucially, at the boundary between the rod-like and lamellar eutectic regions (lower left corner of

Figure 4(d)), a small amount of anomalous eutectic structure, similar to that in deeply undercooled Ni-Sn alloys, is observed. With a further jump in drawing speed, the microstructure evolves as shown in

Figure 4(e), where regular lamellar eutectic transforms into anomalous eutectic and short rod-like structures (high magnification in

Figure 4(f)). This suggests that under steady-state directional solidification, regular lamellar eutectic is the preferred growth morphology. During a jump speed, interface instability causes the regular lamellar structure to first transform into anomalous eutectic, subsequently evolving into a short rod-like morphology.

3.2.2. Microstructural Morphology at the Transition Interface in Ni-32.5wt.%Sn Eutectic Alloy

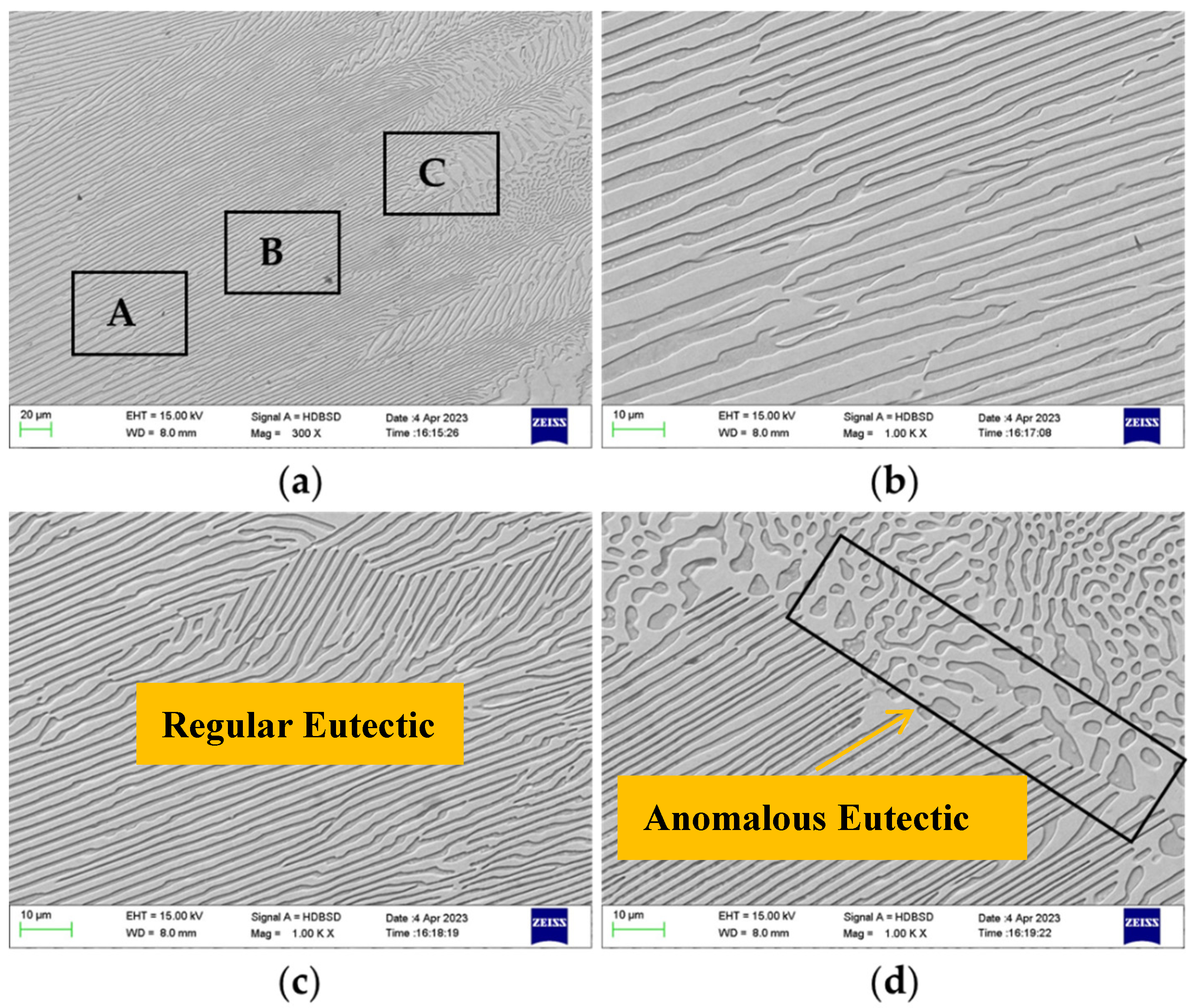

Figure 5 presents the microstructure evolution of Ni-32.5wt.%Sn eutectic alloy during directional solidification with transition variable speed between 0.1 μm/s and 1000 μm/s.

Figure 5(a) shows the transition interface, clearly divided into three distinct regions (A, B, C) based on morphology. Higher magnification images of regions A, B, and C are shown in

Figure 5(b), (c), and (d), respectively. Following the rate jump, the initially coarse regular lamellar eutectic progressively refines into a fine regular lamellar structure with reduced interlamellar spacing (

Figure 5(b)). Due to slight sample tilt during observation, the lamellar growth direction appears at an angle to the longitudinal axis of the specimen cross-section. Quantitative analysis confirmed that the eutectic interlamellar spacing decreased from 3.8 μm to approximately 2.5 μm. Remarkably, this refined spacing (~2.5 μm) persisted even during subsequent constant velocity pulling at 1000 μm/s after the jump. This refinement mechanism is attributed to the sudden increase in solidification velocity during the jump. Solute in the liquid ahead of the interface cannot diffuse laterally fast enough, leading to solute pile-up near the interface [

32]. For the eutectic composition alloy (Ni-32.5wt.%Sn), the initial precipitation of α-Ni phase during solidification enriches the adjacent liquid in Ni₃Sn. This increased solute concentration causes lamellar depression. When this depression reaches a critical point, a new phase nucleates within the depression, and the other phase branches via a "bridging" mechanism, effectively reducing the lamellar spacing [

33].

With further jumps in drawing speed, the growth direction of the lamellar eutectic shifts, resulting in an angle between the lamellae and the solidification (withdrawal) direction (

Figure 5(c)). Crucially, at another jump transition zone, a transformation from regular lamellar eutectic to anomalous eutectic was observed at the solidification front, as indicated by the rectangle in

Figure 5(d). The morphology of this anomalous eutectic closely resembles that found at the bottom of deeply undercooled and laser-remelted Ni-Sn eutectic alloy samples. This demonstrates that abrupt changes in solidification velocity during directional solidification can induce anomalous eutectic formation. However, anomalous eutectic was not observed at all jump transition interfaces, indicating that its formation occurs within a specific processing window.

3.2.3. Microstructural Morphology at Transition Interfaces in Ni-33wt.%Sn Hypereutectic Alloy

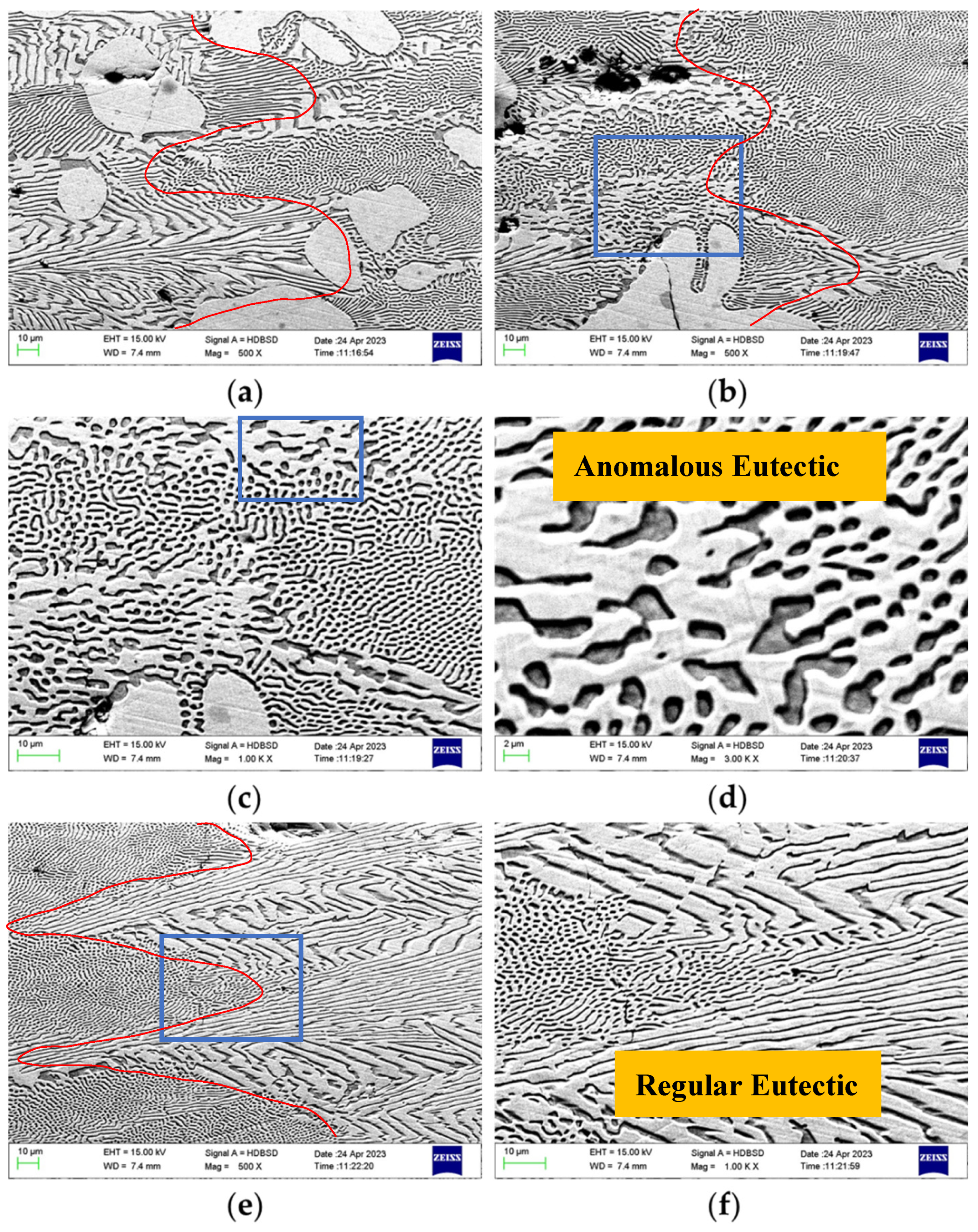

Figure 6 shows Microstructure evolution of Ni-33wt.%Sn hypereutectic alloy during directional solidification with transition variable speed between 0.1 μm/s and 1000 μm/s. As can be seen in

Figure 6(a), (b) and (e), the transition interfaces can be divided into two parts based on the different microstructural morphology (marked by red lines).

Figure 6(a) reveals that in the initial drawing speed of 0.1 μm/s, the white primary Ni₃Sn phase is nearly cellular. The regions between primary dendrites on the left side of the interface are primarily filled with regular lamellar eutectic. Following the jump interface (right side), a higher proportion of rod-like eutectic is present.

Figure 6(b) shows that with increasing jump magnitude, a small amount of anomalous eutectic forms at the interface (higher magnification in

Figure 6(c) and (d)), surrounded by rod-like eutectic. Subsequent jumps in drawing speed (

Figure 6(e) and (f)) lead to a transition back to regular lamellar/rod-like eutectic, but with coarser inter-lamellar/ inter-rod spacing. This coarsening suggests a jump to a lower drawing speed at this interface. With a further jump (presumably back to a higher rate), the coarse lamellar eutectic refines again. Additionally, under a steady-state drawing speed of 1000 μm/s, the primary Ni₃Sn phase adopts an axial linear form, giving rise to a feathery eutectic structure. As for Ni-33wt.%Sn hypereutectic alloy, anomalous eutectic is not observed at all jump transition interfaces, indicating that its formation occurs within a specific processing window.

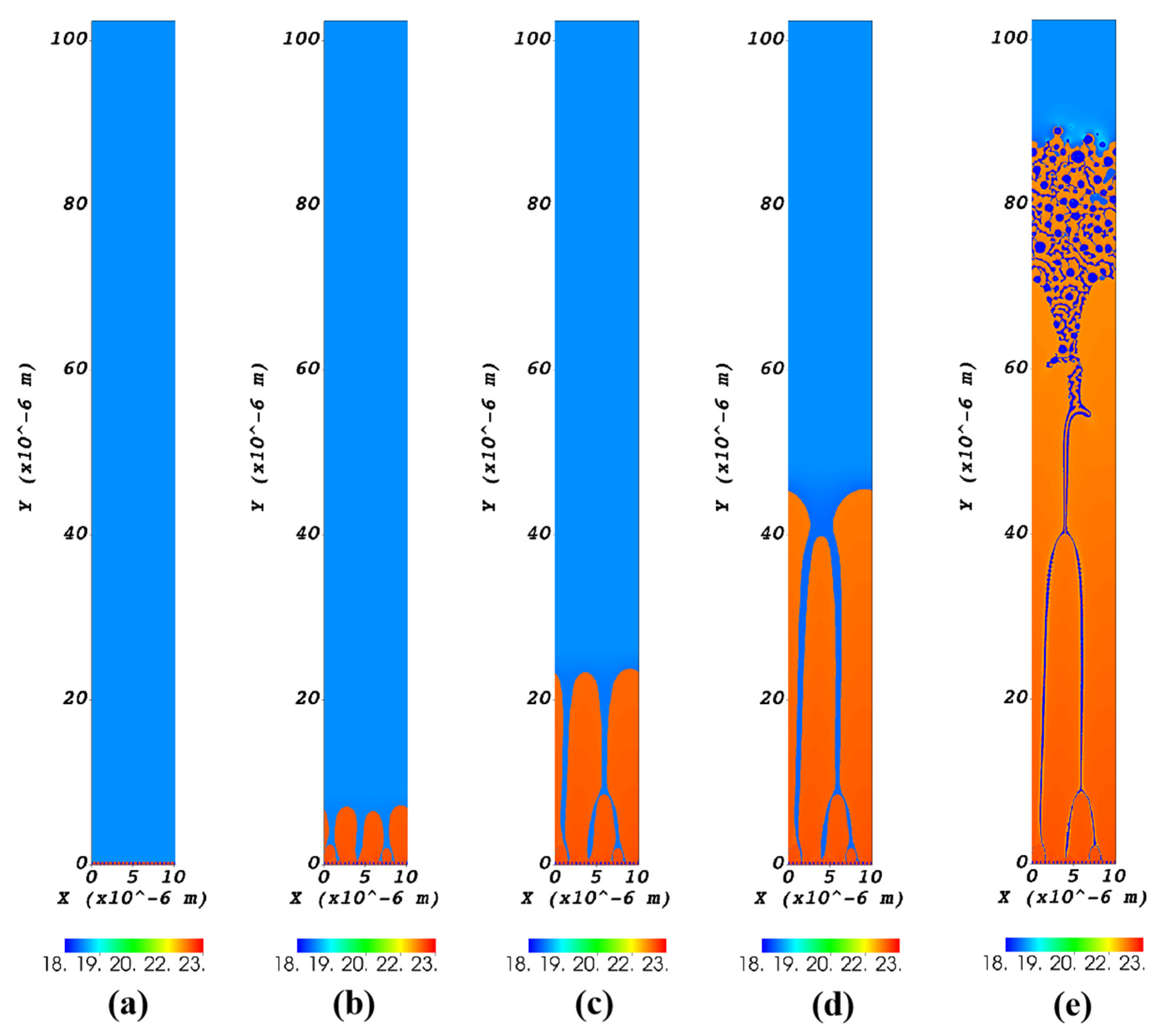

3.3. CA Simulation of Ni-Sn Eutectic Microstructural Evolution During Directional Solidification

Figure 7 presents the simulated evolution of eutectic microstructure in Ni-32.5wt.%Sn alloy during jump transition directional solidification, calculated using the Cellular Automaton (CA) method. The pulling velocity transitioned from 0.1μm/s to 2000μm/s within the first 0.06s time. In

Figure 7, orange regions represent the Ni₃Sn phase, dark blue regions represent the α-Ni phase, and blue regions represent the liquid phase. As shown in

Figure 7(a), the microstructure is lamellar eutectic with the lamellar spacing of 0.5μm at the first 0.02s. From

Figure 7(b) to (d), the Ni

3Sn phase epitaxially grows along the substrate in a cellular manner. The simulation clearly demonstrates that the jump in drawing speed triggers a morphological transition from regular lamellar eutectic to anomalous eutectic, as can be seen in

Figure 7(e). Furthermore, the CA results indicate that the rapid velocity jump destabilizes the regular lamellar eutectic. This instability allows the Ni

3Sn phase epitaxially grows along the substrate in a cellular manner, then the α-Ni phase to nucleate freely within the liquid ahead of the interface, followed by enveloping growth of the Ni₃Sn phase around the α-Ni, leading to the formation of anomalous eutectic structures, which has been elaborated in the reference [

34]. Interestingly,

Figure 7(e) is very similar to

Figure 6(c) in terms of details. That is to say, the CA simulation results show good agreement with the experimental observations from Bridgman directional solidification with transition variable speed.

From our experimental results, when the Ni-Sn alloy is directionally solidified at a constant rate, it is not easy to produce anomalous eutectic structure; when the Ni-Sn alloy is directionally solidified at a variable speed, it is easy to produce anomalous eutectic structure similar to that under deep undercooling conditions. The rapid transition of growth rate will cause the instability of the regular lamellar eutectic.From our CA simulation, the α-Ni phase and the Ni3Sn phase decoupled growth to form anomalous eutectic. The Ni3Sn phase epitaxially grows along the substrate in a cellular morphology. Then the α-Ni phase will nucleate randomly in the liquid phase at the front of the solid-liquid interface and then the Ni3Sn phase will wrap the α-Ni phase to form anomalous eutectic structure.

4. Conclusions

Bridgman directional solidification experiments conducted within a drawing speed range of 0.1-2000 μm/s showed that constant drawing speeds consistently produced regular lamellar/rod-like microstructures. Anomalous Ni-Sn eutectic structures, resembling those formed under deep undercooling conditions, were identified specifically within transition zones associated with abrupt changes (jumps) in drawing speed. The formation of anomalous eutectic occurs within a specific processing window defined by the jump parameters. The CA simulations revealed that rapid jumps in growth velocity destabilize the regular lamellar eutectic. This instability facilitates the free nucleation of the α-Ni phase within the liquid ahead of the solid-liquid interface, followed by enveloping growth of the Ni₃Sn phase, ultimately forming the anomalous eutectic structure. The α-Ni phase and the Ni3Sn phase are decoupled growth to form anomalous eutectic. The CA simulation results are in good agreement with the experimental findings from Bridgman directional solidification.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.C. and L.W.; methodology, H.C.; software, L.W.; validation, Y.C., L.S. and J.L.; formal analysis, M.L.; investigation, L.J.; resources, D.Z.; data curation, J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.C.; writing—review and editing, H.C.; visualization, H.C.; supervision, L.J.; project administration, L.S.; funding acquisition, D.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Key Research and Development Special Project of Henan Province, China under Grant number 251111220600; the Central Guidance on Local Science and Technology Development Fund of Henan Province (No. Z20231811033); and the Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province (No. 212300410206).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the State Key Laboratory of Solidification Processing in Northwestern Polytechnical University for providing essential experimental apparatuses.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kante, S.; Leineweber, A. EBSD Characterization of the Eutectic Microstructure in Hypoeutectic Fe-C and Fe-C-Si Alloys. Mater. Charact. 2018, 138, 274–283.

- Yang, L.; Li, S.; Guo, J.; Fan, K.; Li, Y.; Zhong, H.; Fu, H. Pattern Selection of Twinned Growth in Aluminum Alloys during Bridgman Solidification. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 741, 131–140.

- Melis, S.; Sabine, B.R.; Silvère,A. Lamella-Rod Rattern Transition and Confinement Effects During Eutectic Growth. Acta Mater. 2023,242, 118425.

- Zhao, K.; Wu, S.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, H.; Song, K.; Wang, T.; Xing, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, K.; Yang, L. Microstructural Refinement and Anomalous Eutectic Structure Induced by Containerless Solidification for High-Entropy Fe–Co–Ni–Si–B Alloys. Intermetallics. 2020, 122, 106812.

- Dong, H.; Chen, Y.Z.; Wang, K.; Shan, G.B.; Zhang, Z.R.; Zhang, W.X.; Liu, F. Modeling Remelting Induced Destabilization of Lamellar Eutectic Structure in an Undercooled Ni-18.7 at.% Sn Eutectic Alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 826, 154018.

- Zhao, R.; Wang, Y.; Gao, J.; Baker, E.B.; Matson, D.M.; Kolbe, M.; Chuang, A.C.P.; Ren, Y. In Situ and Ex Situ Studies of Anomalous Eutectic Formation in Undercooled Ni–Sn Alloys. Acta Mater. 2020, 197, 198–211.

- Dong, H.; Chen, Y.Z.; Zhang, Z.R.; Shan, G.B.; Zhang, W.X.; Liu, F. Mechanisms of Eutectic Lamellar Destabilization upon Rapid Solidification of an Undercooled Ag-39.9 at.% Cu Eutectic Alloy. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2020, 59, 173–179.

- Liu, L.J.; Wei, X.X.; Ferry, M.; Li, J.F. Investigation of the Origin of Anomalous Eutectic Formation by Remelting Thin-Gauge Samples of an Ag-Cu Eutectic Alloy. Scr. Mater. 2020, 174, 72–76.

- Zhao, R.; Wang, Y.; Gao, J.; Baker, E.B.; Matson, D.M.; Kolbe, M.; Chuang, A.C.P.; Ren, Y. In Situ and Ex Situ Studies of Anomalous Eutectic Formation in Undercooled Ni–Sn Alloys. Acta Mater. 2020, 197, 198–211.

- Liu, L.; Wei, X.X.; Huang, Q.S.; Li, J.F.; Cheng, X.H.; Zhou, Y.H. Anomalous Eutectic Formation in the Solidification of Undercooled Co-Sn Alloys. J. Cryst. Growth. 2012, 358, 20–28.

- Xu, J.; Zhang, D.; Liu, F.; Jian, Z. Multi-Transformations in Rapid Solidification of Highly Undercooled Hypoeutectic Ni-Ni3B Alloy Melt. J. Mater. Res. 2015, 30, 3307–3315.

- Fiore, G.; Quaglia, A.; Battezzati, L. Banded Regular/Anomalous Eutectic in Rapidly Solidified Co-61.8 at.% Si. Scr. Mater. 2019, 168, 100-103.

- Yang, C.; Gao, J.; Zhang, Y.K.; Kolbe, M.; Herlach, D.M. New Evidence for the Dual Origin of Anomalous Eutectic Structures in Undercooled Ni-Sn Alloys: In Situ Observations and EBSD Characterization. Acta Mater. 2011, 59, 3915–3926.

- Li, M.; Nagashio, K.; Kuribayashi, K. Reexamination of the Solidification Behavior of Undercooled Ni-Sn Eutectic Melts. Acta Mater. 2002, 50, 3241–3252.

- Li, J.F.; Li, X.L.; Liu, L.; Lu, S.Y. Mechanism of Anomalous Eutectic Formation in the Solidification of Undercooled Ni-Sn Eutectic Alloy. J. Mater. Res. 2008, 23, 2139–2148.

- Jin, G.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yu, L.; Li, S.; Xing, H. Formation of Seaweed Morphology and Enhancing Mechanical Properties of an A356 Alloy by Directional Solidification. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 177197.

- Shen, Y.; Liu, J.; Yang, S.; Yan, B.; He, Y.; Liu, H.; Xu, H. Dendrite Growth Behavior in Directionally Solidified Fe–C–Mn–Al Alloys. J. Cryst. Growth. 2019, 511, 118–126.

- Clopet, C.R.; Cochrane, R.F.; Mullis, A.M. The Origin of Anomalous Eutectic Structures in Undercooled Ag-Cu Alloy. Acta Mater. 2013, 61, 6894–6902.

- Wang, N.; Jia, L.; Kong, B.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, H. Eutectic Evolution of Directionally Solidified Nb-Si Based Ultrahigh Temperature Alloys. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2018, 71, 273–279.

- Son, H.Y.; Jung, I.Y.; Choi, B.G.; Shin, J.H.; Jo, C.Y.; Lee, J.H. Effects of Chemical Composition and Solidification Rate on the Solidification Behavior of High-Cr White Irons. Metals. 2024, 14,276.

- Cui, C.; Wang, C.; Wang, P.; Liu, W.; Lai, Y.; Deng, L.; Su, H. Microstructure and Fracture Toughness of the Bridgman Directionally Solidified Fe-Al-Ta Eutectic at Different Solidification Rates. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2020, 42, 63–74.

- Kang, J.; Li, J. Microstructural Evolution in Directional Solidification of Nb-doped Co-Sn/Ni-Sn Eutectic Alloys. Appl. Phys. A. 2021,127,809.

- Campo, K.N.; Wischi, M.; Rodrigues, J.F.Q.; Starck, L.F.; Sangali, M.C.; Caram, R. Directional Solidification of the Al0.8CrFeNi2.2 Eutectic High-Entropy Alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 30, 8874–8881.

- Wei, L.; Cao, Y.; Lin, X.; Wang, M.; Huang, W. Quantitative Cellular Automaton Model and Simulations of Dendritic and Anomalous Eutectic Growth. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2019,156,157-166.

- Clopet, C.R.; Cochrane, R.F.; Mullis, A.M. Spasmodic Growth During the Rapid Solidification of Undercooled Ag-Cu Eutectic Melts. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013,102,031906.

- Kurz, W., Fisher, D.J. Fundamentals of solidification, 3rd ed. Trans Tech Publications: Aedermannsdorf, Switzerland, 1992; 83-84.

- Ma, X.; Liu, L. Solidification Microstructures of the Undercooled Co-24at%Sn Eutectic Alloy Containing 0.5at%Mn. Mater. Des. 2015, 83, 138–143.

- Yamauchi, I.; Ueyama, S.; Ohnaka, I. Effects of Mn and Co Addition on Morphology of Unidirectionally Solidified FeSi2 Eutectic Alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 1996, 208, 101–107.

- Zhao, S.; Li, J.; Liu, L.; Zhou, Y. Eutectic growth from cellular to dendritic form in the undercooled Ag-Cu eutectic alloy melt. J. Crystal Growth. 2009, 311,1387-1391.

- Tang, P.; Tian, Y.; Liu, S.; Lv, Y.; Xie, Y.; Yan, J.; Liu, T.; Wang, Q. Microstructure Development in Eutectic Al-Fe Alloy During Directional Solidification under High Magnetic Fields at Different Growth Velocities. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56,16134-16144.

- Wei, B.; Yang, G.; Zhou, Y. High Undercooling and Rapid Solidification of Ni-32.5%Sn Eutectic Alloy. Acta metall mater. 1991, 39,1294-1258.

- Qin, Q.Y.; Li, J.F.; Yang, L.; Liu, L.J. Solidification Behavior and Microstructure of Ag–Cu Eutectic Alloy at Different Sub-Rapid Cooling Rates. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2024, 311, 128521.

- Karma, A. Beyond Steady-State Lamellar Eutectic Growth. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1987,59,71-74.

- Wei, L.; Cao, Y.; Lin, X.; Huang, W. Cellular Automaton Simulation of the Growth of Anomalous Eutectic during Laser Remelting Process. Materials. 2018, 11, 1844.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).