1. Introduction

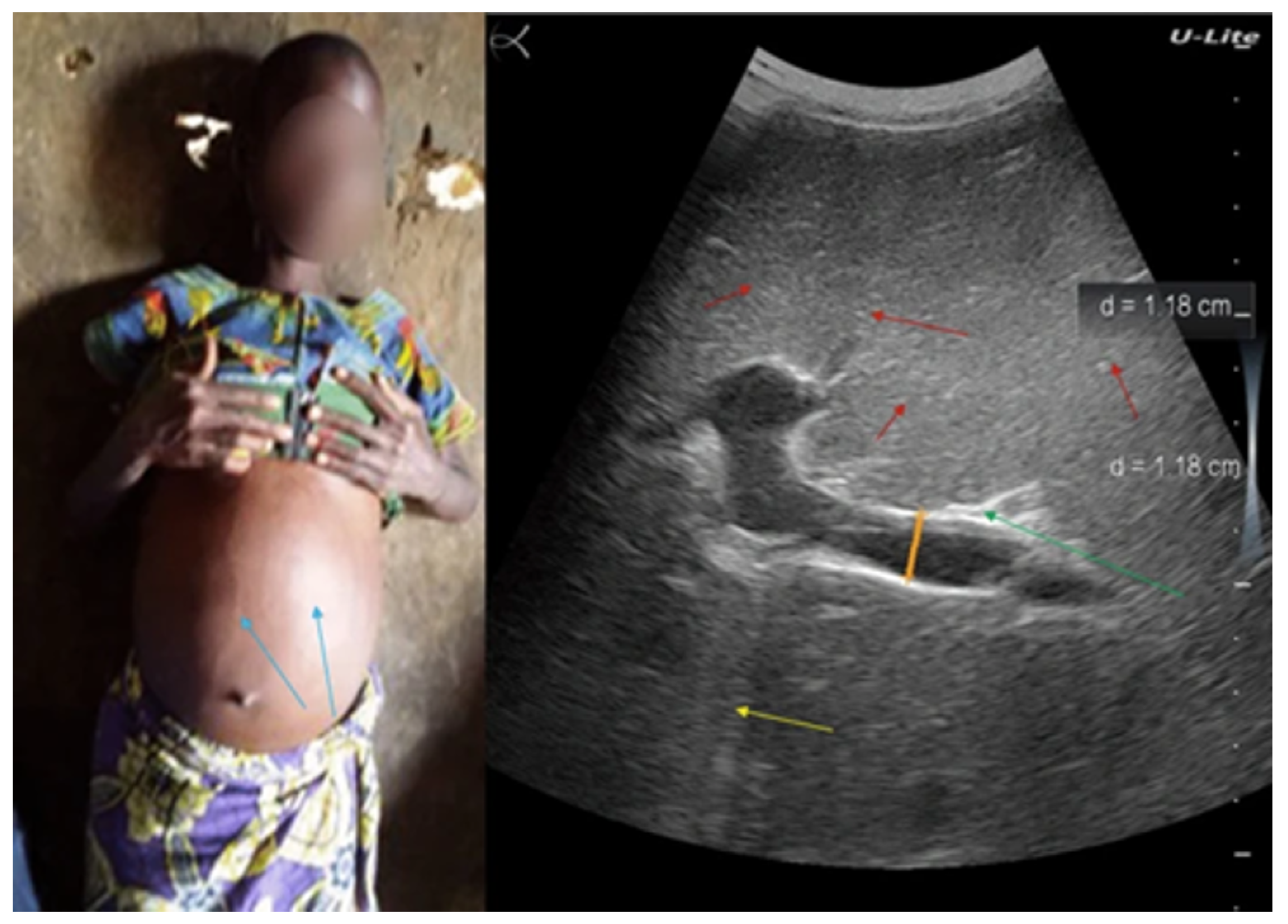

Intestinal schistosomiasis, caused by the blood fluke Schistosoma mansoni, is a major public health concern, affecting approximately 54 million people annually, primarily in sub-Saharan Africa [

1]. The infection leads to intestinal schistosomiasis, with pathological manifestations arising from the formation of granulomas around eggs that become lodged in the liver. Granuloma formation leads to PPF, a severe complication affecting a significant proportion of infected individuals, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa [

2]. In Uganda,

S. mansoni infection affects up to 70% of the population in endemic regions, with a particularly high prevalence of PPF observed in communities along the shores of Lake Albert and Lake Victoria [

3]. PPF is a common manifestation of chronic liver diseases and significantly impacts morbidity and mortality [

4]. Early detection of periportal fibrosis is crucial for timely intervention and the potential for reversibility.

Currently, non-invasive diagnostic imaging methods such as ultrasound, CT, MRI, and elastography are used to assess and detect liver damage due to chronic schistosomiasis [

5]. However, these methods have limitations. Conventional scoring systems for liver fibrosis based on these imaging techniques are often time-consuming, subjective, and semi-quantitative, leading to variability in interpretation and potential diagnostic inaccuracies [

6].

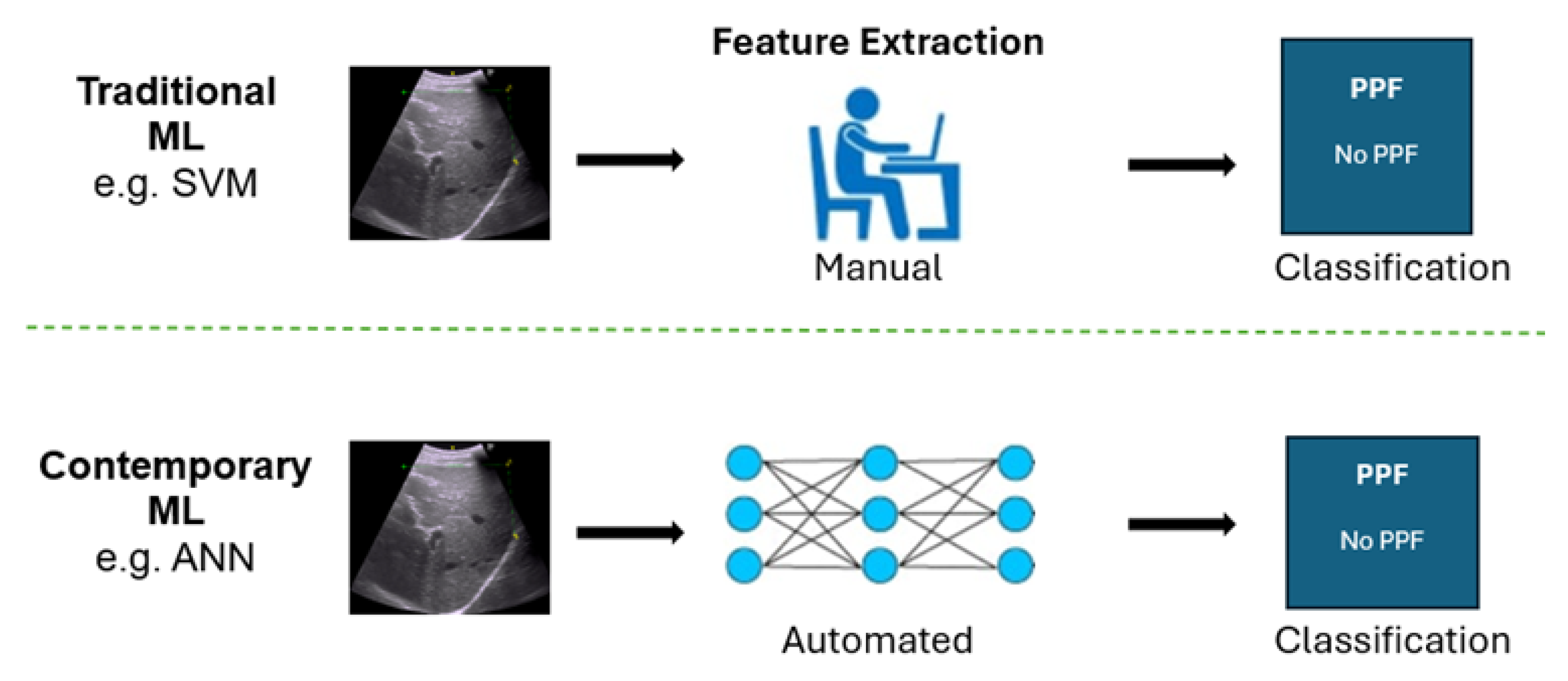

As illustrated in

Figure 1, ultrasound imaging can visualize characteristic features of PPF. However, interpretation still relies heavily on the sonographer’s expertise, which introduces variability and limits scalability in low-resource settings.

These limitations stem from the inherent subjectivity in interpreting imaging features and the reduced sensitivity of these methods in identifying the subtle signs of early-stage fibrosis.

Machine learning (ML), a branch of artificial intelligence (AI), enables computers to recognise patterns in data, supporting prediction and decision-making [

8]. Positioned within the broader AI framework, ML plays a pivotal role in the development of intelligent diagnostic systems in healthcare. Imagine a computer system trained on thousands of medical images: it learns to recognize subtle patterns linked to liver disease and, without explicit programming, continuously improves its diagnostic performance through exposure to data and experience.

Traditional machine learning techniques have been instrumental in advancing medical imaging, supporting tasks such as classification, segmentation, and registration [

9]. Typically, these methods involve manual feature extraction, where domain experts carefully identify and select relevant features from images, such as texture, shape, or intensity, that signify the condition being analysed. These identified features are then fed into machine learning algorithms like Support Vector Machines (SVMs), which help automate the classification or segmentation of these images [

10,

11]

While traditional machine learning algorithms have contributed significantly to medical imaging, they face notable limitations. These models typically depend on manual feature extraction, which is inherently subjective and sensitive to variations in image characteristics such as size, texture, and shape [

12]. Manual feature extraction often results in inconsistent diagnostic outcomes due to variability in how features are selected and interpreted. Furthermore, traditional methods often struggle to manage the high dimensionality and nuanced patterns present in medical images, limiting their effectiveness in detecting subtle pathological features [

13]. Even established models like SVMs have shown inefficiencies in complex image recognition tasks compared to newer, data-driven approaches [

14]. These challenges underscore the shift toward deep learning as a more robust alternative for medical image analysis.

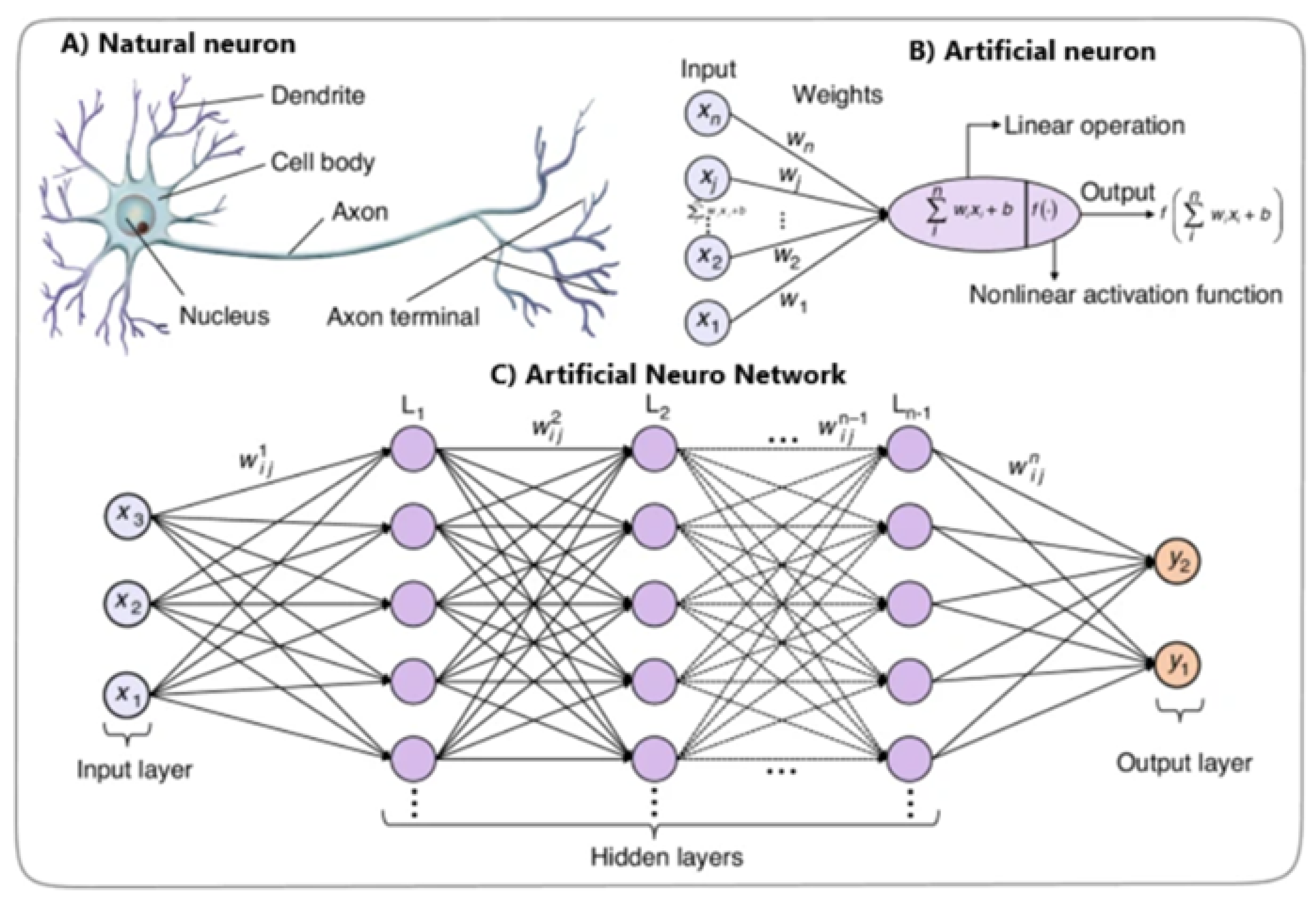

Traditional machine learning techniques have made significant contributions to medical image analysis; however, their limitations have led to the development of more advanced methods, notably deep learning.

Deep Learning (DL) is a subset of machine learning that uses deep neural networks (DNNs) with multi-layered architectures designed to automatically learn complex patterns and representations from large amounts of data. Inspired by the human brain (

Figure 2), DL algorithms overcome limitations and reveal new possibilities in medical imaging [

15].

DNNs automate feature extraction and handle the complexity of medical image data, unlike traditional methods dependent on manual feature engineering. DNN algorithms autonomously learn complex patterns and representations from raw image data, identifying subtle details and relationships that traditional techniques might miss [

12].

Deep Neural Networks excel due to their ability to detect complex visual patterns, generate consistent and objective measurements, and eliminate the need for manual feature selection. These attributes have proven instrumental in enhancing diagnostic accuracy for PPF detection [

15].

Whereas DL has been applied to liver fibrosis detection more broadly [

17], few studies have specifically addressed schistosomiasis-related PPF using the Niamey protocol, a standardized set of ultrasound guidelines for the assessment of schistosomiasis-related morbidity, particularly PPF caused by Schistosoma mansoni [

18,

19]. This study aims to fill this gap by implementing and evaluating a DL-based approach for automated detection of PPF in ultrasound images, providing an objective and scalable tool for early diagnosis in endemic regions.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the contrast in feature selection approaches between traditional methods and DNNs.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the contrast in feature selection approaches between traditional methods and DNNs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset Source

This study utilised a comprehensive liver ultrasound image dataset from a case-control study conducted by the Uganda Schistosomiasis Multidisciplinary Research Centre (U-SMRC) [

20]. Data were collected between October 2023 and June 2024 from adult participants living in communities near Lake Victoria and Lake Albert, two distinct epidemiological settings [

21]. The study aimed to investigate risk factors associated with severe schistosomal morbidity by comparing individuals with advanced disease (cases) to those without or with mild infection (controls). Liver ultrasound images were part of the inclusion criteria to assess schistosomiasis-related PPF.

The liver ultrasound images were meticulously annotated by an experienced study sonographer using the

Niamey protocol, a standardised ultrasonography protocol, which is fundamental for assessing schistosomiasis related morbidity, particularly hepatic morbidity caused by Schistosoma mansoni [

18,

19].

The Image Pattern Score (IPS), derived from the

Niamey protocol, provided a standardised approach for evaluating liver damage resulting from schistosomiasis. The score incorporates key sonographic indicators including liver surface nodularity, periportal thickening, parenchymal echogenicity, signal attenuation, and intrahepatic nodules or masses to assess the severity of PPF [

35]. Trained sonographers systematically evaluated these features and assigned an Image Pattern Score.

In this study, we employed image classification as the primary task, framed within the paradigm of supervised learning. In supervised learning, models are trained on labelled datasets, where each input image is paired with a known outcome, enabling the system to learn mappings from input features to target labels [

22]. Ultrasound images were labelled according to the IPS assigned by the study’s radiologist following the Niamey protocol. Specifically, we designated images with IPS of 2 or higher as

cases and those with IPS of 0 or 1 as

controls. The CNN was trained to identify subtle ultrasound features associated with PPF, conditioned on these labels, and subsequently applied to unseen scans for classification.

The dataset source contained 791 liver ultrasound images (197 cases and 594 controls) from adults aged 18 to 50 years. For this study, we selected 200 images (100 cases and 100 controls) to create a balanced dataset for binary classification. This sample size was not statistically derived but was determined based on operational limitations. Specifically, the manual process of extracting and reviewing images from the ultrasound system was time-consuming, and time constraints did not permit the inclusion of additional samples. Images were selected sequentially, without applying specific inclusion criteria beyond the IPS-based classification, until the required number for each group was reached.

This approach yielded a curated dataset with equal representation of disease and non-disease cases. Of the 200 labelled images, 80% were used for training and 20% for testing.

All ultrasound images were stripped of identifying information to protect participant privacy, in compliance with the Uganda Data Privacy and Protection Act [

23] and the General Data Protection Regulation [

24]. Participants in the original USMRC study had given prior consent for their ultrasound data to be used in research, allowing for ethical secondary analysis. The study received approval from the University of Essex ethics committee following the submission of a detailed proposal, including formal consent from USMRC principal investigators.

2.2. Data Extraction and Pre-Processing

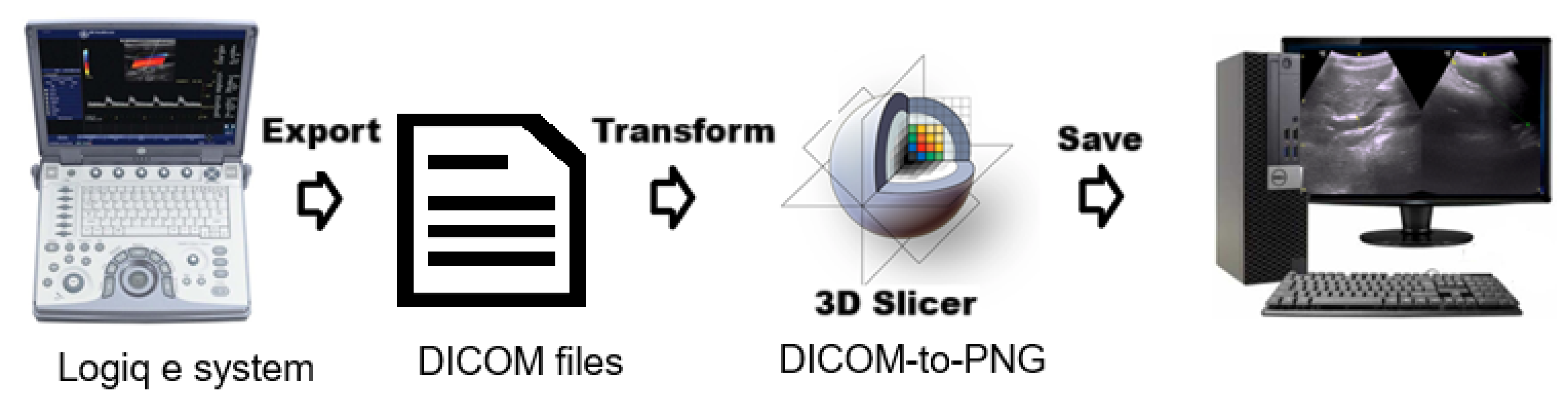

The ultrasound data processing pipeline included several key stages to prepare images for machine learning analysis. Ultrasound images were exported in Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine(DICOM) format, the international standard for handling, storing, printing, and transmitting information in medical imaging. 3D Slicer, an open-source medical imaging tool, was used to retrieve and process these files, enabling visualization and feature extraction.

Figure 4.

Pipeline illustrating the extraction and storage of ultrasonography (US) images using 3D Slicer software.

Figure 4.

Pipeline illustrating the extraction and storage of ultrasonography (US) images using 3D Slicer software.

Processed images were exported as PNG files, with all identifiable metadata removed to ensure compliance with privacy regulations and maintain participant anonymity. Several steps were performed to optimize image data for model training. Study IDs were replaced with anonymized labels, and images were categorized with prefixes (e.g., fibrosis_, nofibrosis_) for classification. Images were resized to pixels while maintaining aspect ratio using padding to ensure uniformity across classes.

To enhance the robustness and generalisation capability of the convolutional neural network, data augmentation techniques were applied during training using the ImageDataGenerator class from Keras. The augmentation strategy introduced random variability into the training images through Random rotations of up to , Horizontal and vertical shifts of up to 20% of the image width and height, respectively and Random horizontal flips. These transformations simulate common variations in medical or real-world imaging and increase the diversity of the training data. As a result, they help reduce overfitting and improve the model’s ability to generalize to unseen data.

Data Normalization was performed to enhance training stability and model performance, all pixel values in the training and test datasets were first cast to 32-bit floating-point format. The mean and standard deviation of the training images were then computed, representing the average brightness and pixel value dispersion, respectively. Normalization was performed using the equation:

where

and

denote the mean and standard deviation of the training dataset. A small constant (

) was added to the denominator to avoid division by zero. This normalization was also applied to the test dataset using the training set statistics, ensuring consistent preprocessing across datasets and avoiding data leakage.

2.3. CNN Model Implementation

The CNN model in this study was implemented using the

Keras Sequential API, a widely adopted high-level deep learning framework built on top of TensorFlow [

25]. The implementation was carried out in Python and utilised several libraries and packages for model construction, training, evaluation, and visualisation. The model layers were constructed using

keras.

We used Google Drive, GitHub, and Google Colab for an efficient model development workflow. Google Colab is a cloud platform which provides access to high-performance hardware such as GPUs and TPUs, significantly speeding up computations compared to typical local machines. This results in faster model training and potentially higher accuracy [

26].

The workflow involved several key steps to ensure seamless integration between data storage, version control, and model training. Initially, periportal images were collected on the local computer and stored in a designated Google Drive directory. These images were organized into two folders labelled "fibrosis" and "nofibrosis" for clear categorization. Jupyter notebooks used for data preprocessing, model training, and evaluation were developed and stored in a GitHub repository, enabling version control and collaboration. Finally, these notebooks and the pre-processed data were linked to Google Colab, where the actual model training took place using the pre-processed data and the computational resources provided by the cloud platform.

2.4. VGG16-Inspired CNN Architecture

The characteristic use of deep, uniform convolutional layers and small filter kernels in the well-known VGG16 guided the structural design of our network [

27].

VGG-16 architecture is well-established for its depth and effectiveness in extracting hierarchical visual features. The network structure includes multiple stacked convolutional layers with small receptive fields, followed by max-pooling operations, allowing for the gradual abstraction of spatial information from ultrasound images of the liver [

28].

Building on these principles, the adapted model was specifically designed to:

Accurately detect PPF in liver ultrasound images.

Maintain computational efficiency for potential use in real-world clinical environments.

Strike a balance between network depth and complexity to ensure good generalisability across diverse data.

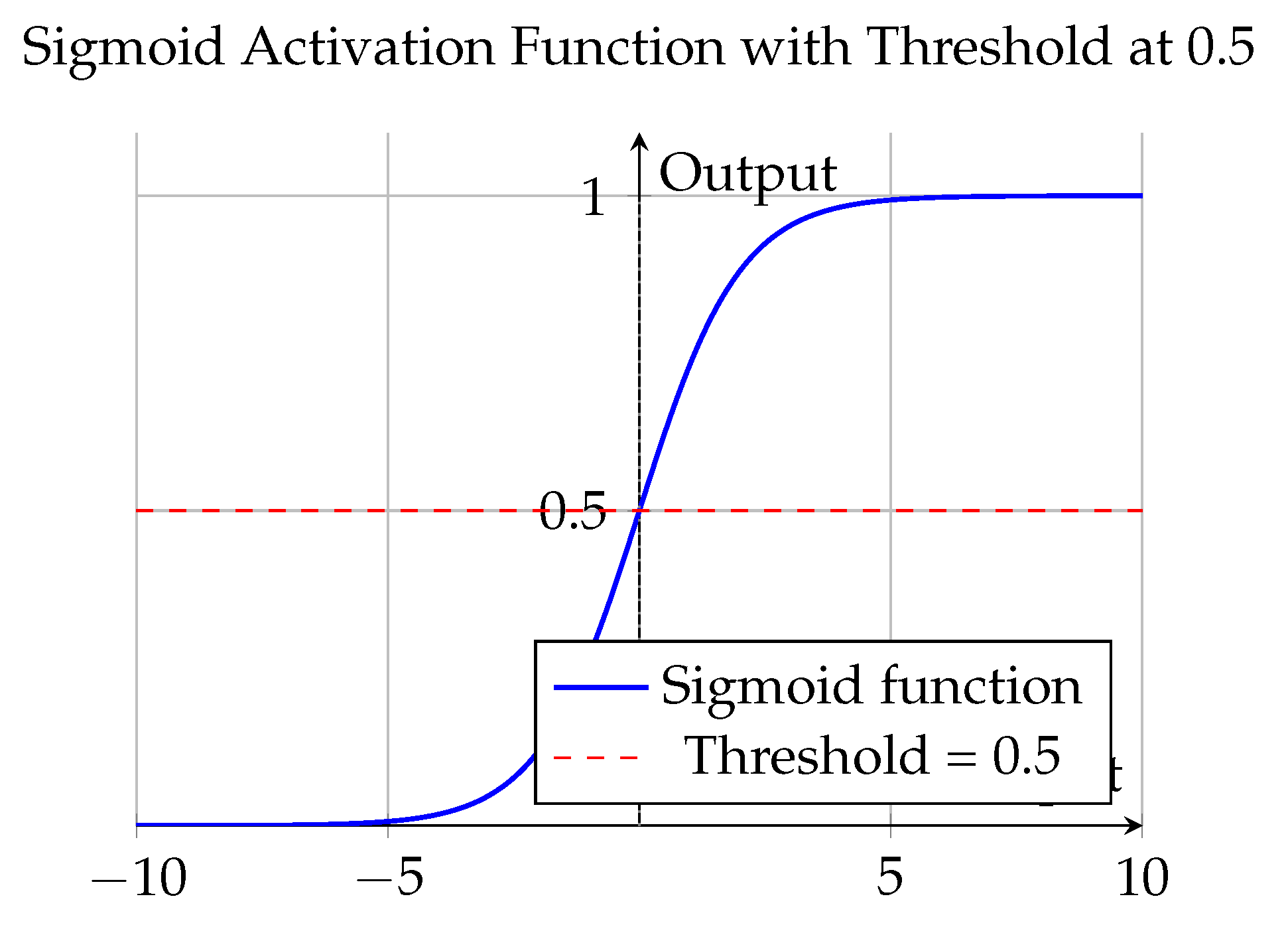

The CNN architecture employed in this study utilised two types of activation functions across different stages of the model to support binary image classification of PPF.

Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation functions were applied to all convolutional and dense layers except the final layer. Defined as

, the ReLU function introduces non-linearity by zeroing out all negative input values while preserving positive ones. This facilitates efficient training by mitigating the vanishing gradient problem and enabling the network to learn hierarchical, discriminative features from liver ultrasound images such as texture, edge contrast, and structural anomalies. The output layer consisted of two neurons activated by the

sigmoid function, defined as:

Each sigmoid unit independently maps its input to a probability range between 0 and 1, allowing the model to assign class confidence scores for the presence or absence of PPF. Since the classification problem was binary and the dataset had a balanced class distribution, a threshold of 0.5 was applied [

29], outputs

were interpreted as PPF-positive, and outputs

as PPF-negative. In deployment, the higher of the two probabilities was used to determine the predicted class.

Together, this activation configuration enabled the model to learn rich representations of image features and translate them into clinically relevant binary predictions.

Figure 5.

Plot of the sigmoid activation function with a threshold at 0.5.

Figure 5.

Plot of the sigmoid activation function with a threshold at 0.5.

2.5. Evaluation Metrics

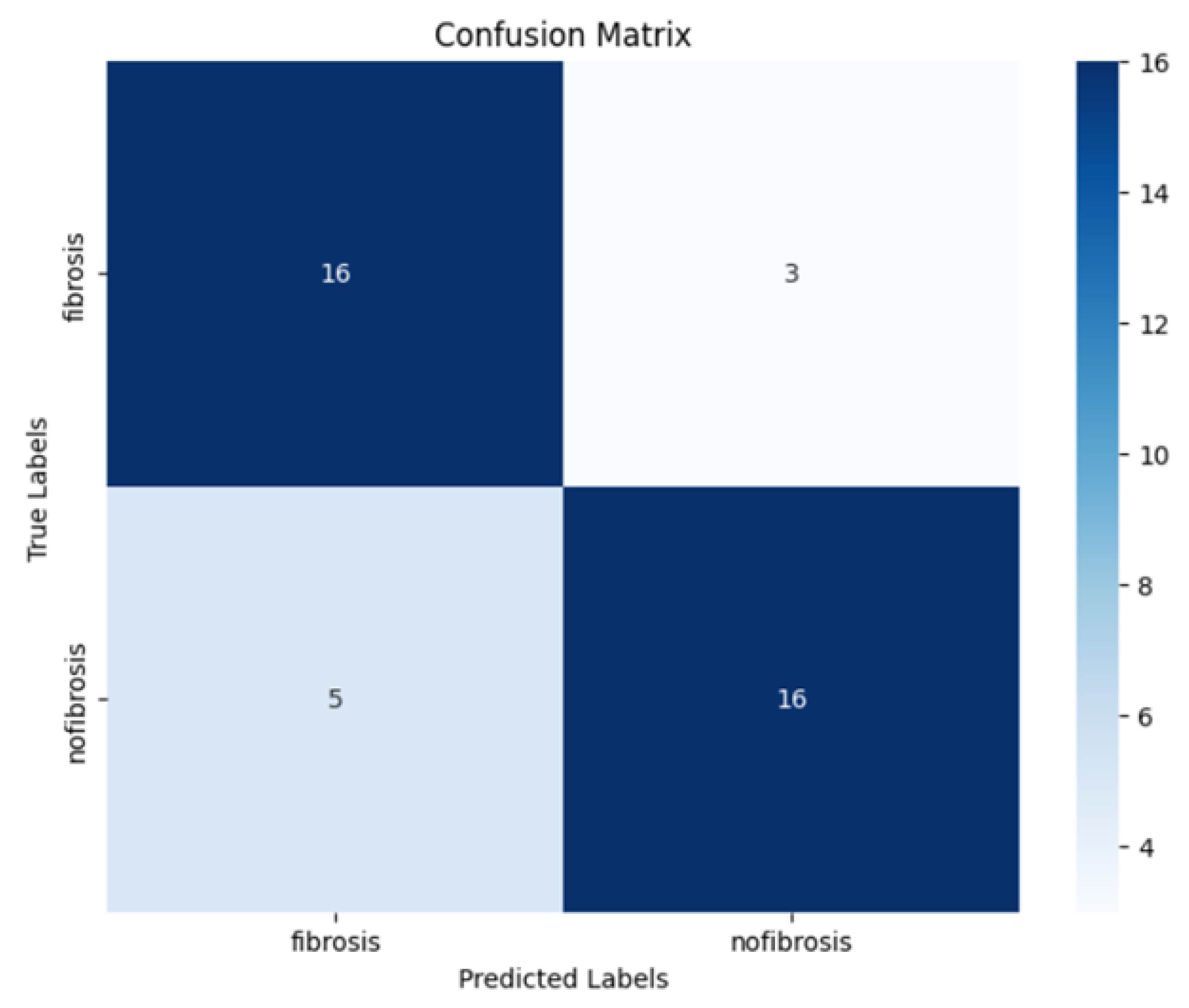

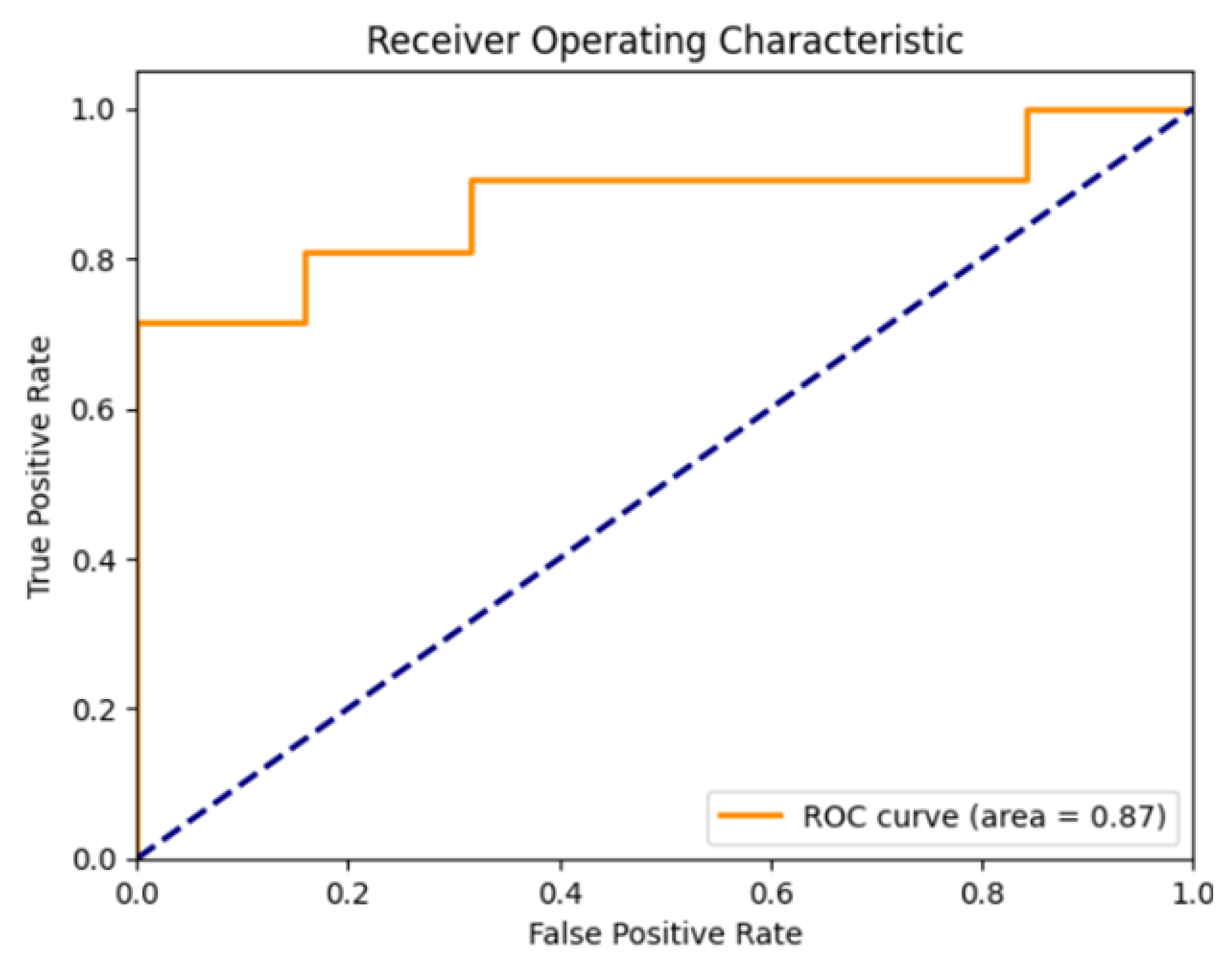

To evaluate model performance, we used standard classification metrics derived from the confusion matrix, including accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score, and specificity. In addition, we assessed the area under the ROC curve (AUC). Together, these metrics provide a comprehensive assessment of both the sensitivity and reliability of the model.

Accuracy represents the proportion of correctly classified instances (both positives and negatives) among the total number of cases. It provides an overall measure of how well the model performs across all classes. It is calculated as:

Precision is defined as the proportion of true positive predictions among all instances that were predicted as positive. It is given by:

Recall, also referred to as sensitivity or the true positive rate, is defined as the proportion of true positive predictions among all actual positive instances. It is calculated using the formula:

The

F1 score is a combined measure of precision and recall, calculated as their harmonic mean. It provides a balance between the two metrics, especially in scenarios where data is imbalanced or when both false positives and false negatives carry significant consequences.

Specificity, also called the true negative rate, measures the proportion of correctly identified negatives among all actual negatives. It is expressed as:

The AUC is a threshold-independent metric that evaluates the model’s ability to distinguish between positive and negative classes. It is computed as the area under the ROC curve, where the curve plots the true positive rate against the false positive rate at various thresholds. An AUC of 1.0 indicates perfect classification, whereas 0.5 corresponds to random guessing.

2.6. Model Training

Random seed initialisation was performed using Python’s built-in random and numpy modules to ensure reproducibility of training results.

Several key hyperparameters were selected and adjusted during the model training process. These adjustments were supported by callbacks that helped fine-tune training based on model performance.

Training began by evaluating two input image resolutions (32×32 pixels and 128×128 pixels), cycling through each size to identify the optimal scale for feature extraction. The network employed the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of .

To enhance generalisation and mitigate overfitting, on-the-fly data augmentation was applied using Keras’s

ImageDataGenerator, which randomly rotated, shifted, and flipped input images during training. Finally, a

dropout rate of 0.5 was used in the fully connected layer to reduce overfitting by randomly deactivating half the neurons during each update. In addition to our baseline training setup, we leveraged two key Keras callbacks to enhance model performance. The first,

ReduceLROnPlateau, monitors validation loss and automatically reduces the learning rate by a factor of 0.1 after 10 epochs without improvement. This approach helps the optimizer converge more precisely once performance plateaus [

30]. The second callback,

EarlyStopping, halts training when no further progress is seen over ten epochs. Together, these callbacks streamlined training, prevented overfitting, and secured an optimally tuned model.

In summary, training was performed using the

Adam optimiser, selected for its adaptive learning rate and strong empirical performance on complex medical imaging tasks. For activation functions, we applied the

ReLU in all hidden layers to introduce non-linearity while maintaining computational efficiency. The final layer used a

sigmoid activation function to output probabilities suitable for binary classification, specifically distinguishing between cases with and without PPF [

31]. Although no automated search strategy was applied, the use of well-chosen hyperparameters and responsive callbacks played an important role in shaping the model’s learning behaviour and improving overall performance.

3. Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive characteristics of the study population from whom the ultrasound images were collected and used to train and test the CNN model. It summarizes the demographic, anthropometric, and ultrasound image pattern scores for the 200 individuals included in the analysis.

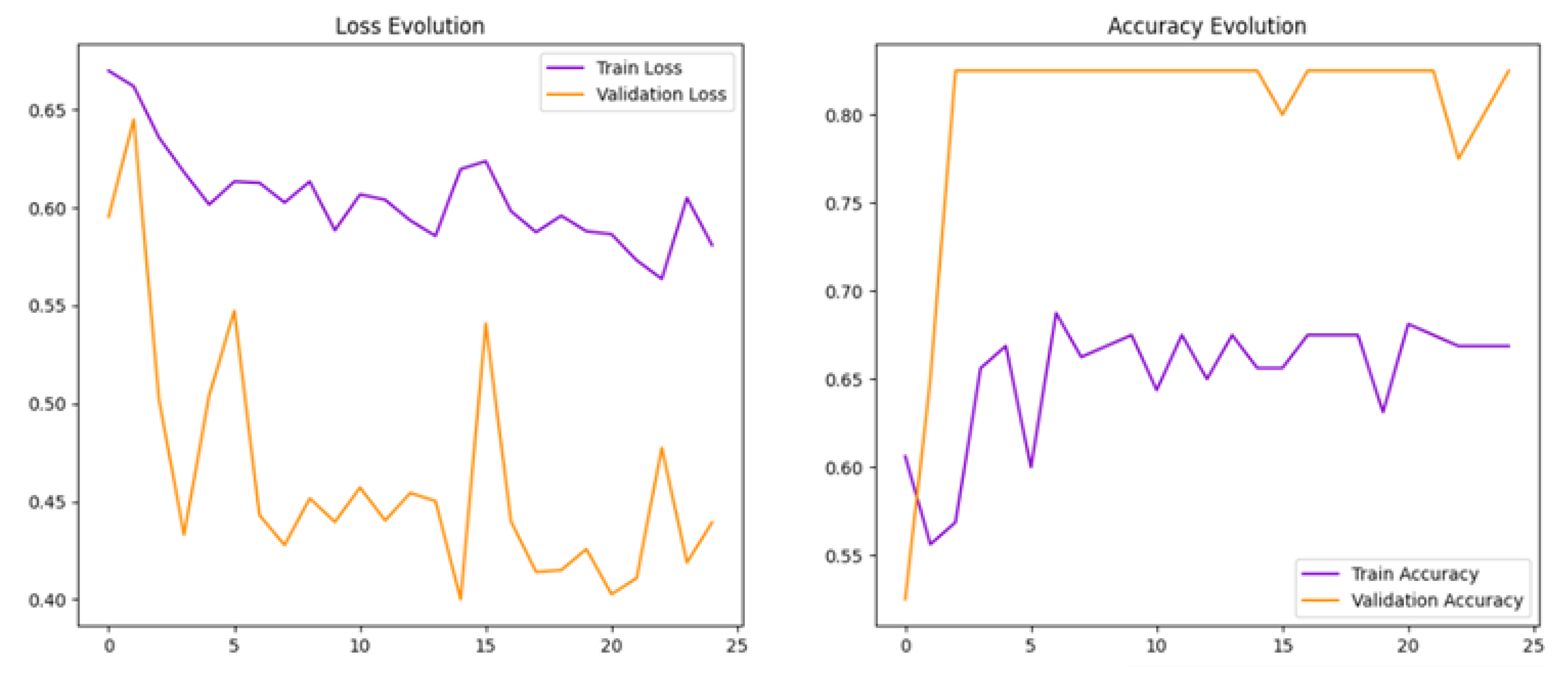

Initially, a baseline model (Model 1) was developed, which an initial batch size of 16 was used and achieved a test accuracy of 82.5% and a test loss of 0.40, showing promising results [

32,

33].

Figure 6 loss and accuracy curves indicated overfitting, as reflected by stable high validation accuracy but fluctuating validation loss. This suggested that the model memorised training data rather than generalizing well.

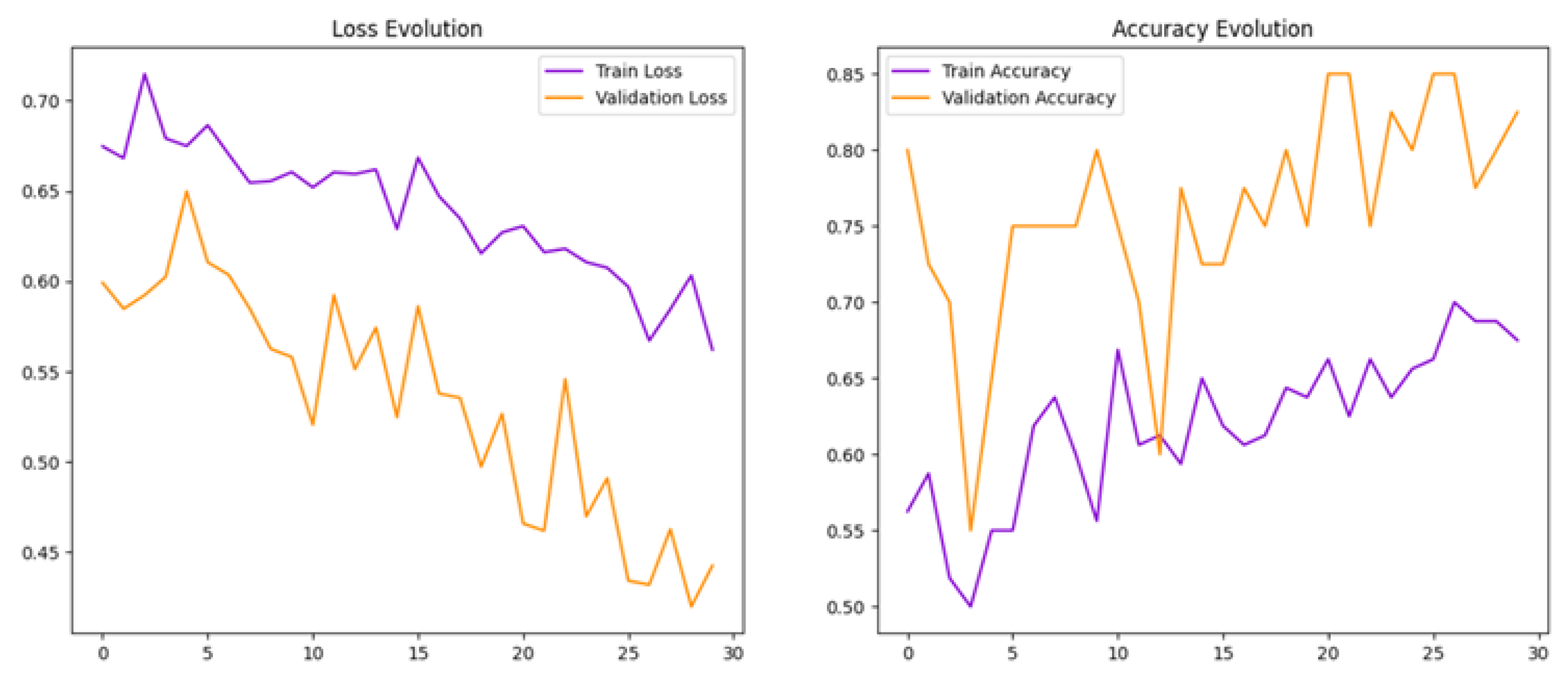

To help reduce overfitting, we increased the batch size from 16 to 32 in Model 2. This adjustment aimed to stabilise training and improve the model’s ability to generalise.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study demonstrate that a convolutional neural network can effectively detect PPF from ultrasound images. The second model (Model 2), developed through iterative optimisation, achieved strong overall performance, suggesting that deep learning can play a valuable role in improving diagnostic accuracy for liver disease caused by Schistosoma mansoni.

The results reflect a balanced ability to both identify true positive cases and avoid false positives, a critical consideration in clinical diagnostics. The model’s high precision indicates that when fibrosis is predicted, it is usually correct, reducing unnecessary concern or follow-up. At the same time, its ability to capture most positive cases highlights its potential to support earlier identification of patients with fibrosis. Taken together, these findings point to a model that could complement human expertise by providing consistent and reliable diagnostic support.

The area under the curve further reinforces the strength of the classifier, indicating that the model could be confidently applied to distinguish between individuals with and without PPF [

34].

One of the main improvements from the baseline model (Model 1) to Model 2 was in addressing overfitting. Initially, while the model showed strong training results, the unstable validation loss suggested it had memorised the training data rather than learned general patterns. By adjusting the batch size, implementing early stopping, and applying data augmentation techniques, Model 2 was able to generalise better. The resulting smoother learning curves indicated more consistent performance on unseen data.

In clinical practice, diagnosing PPF through ultrasound imaging requires significant expertise and is prone to subjectivity. The use of a CNN model provides an opportunity to standardise this process, reducing reliance on expert interpretation and increasing the consistency of results. This could be especially beneficial in low-resource settings where access to trained radiologists or sonographers is limited.

Moreover, early detection of PPF is crucial, as it can prevent progression to more severe liver complications. An automated tool capable of identifying early signs of fibrosis in routine ultrasound scans could support timely interventions and improve patient outcomes.

The results observed here are comparable to those from similar studies. For instance, Lee et al. (2020) reported strong performance using deep learning on ultrasound data to detect liver fibrosis, similar to the performance achieved in this study. However, this project differs in that it focuses specifically on PPF, rather than general liver fibrosis, and applies the Niamey protocol, which is widely used in field-based diagnostics. This makes the model more applicable to schistosomiasis-endemic settings, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa.

While the results are encouraging, this study has a number of limitations. The dataset included only 200 ultrasound images, which may restrict how well the model generalises to broader populations or different imaging settings. Another limitation is that the initial classification of images was carried out by only one ultrasonographer. Having a second independent reviewer would have reduced the risk of relying on a single person’s subjective perspective. Moreover, no other types of liver disease were included, meaning the procedure may not perform as well if other causes of fibrosis are present.

Future research should therefore aim to train and validate the model on larger and more varied datasets, ideally collected from multiple centres and regions. Another direction is extending the model beyond binary classification (fibrosis versus no fibrosis) to predict different levels of fibrosis severity, as defined by the Niamey grading system, which could enhance clinical utility. Future work could also explore the use of interpretability methods such as Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM), which highlight the regions of an image most influential in the model’s decision. This would make the system more transparent and help build clinician confidence in its outputs.

Conclusions

This study adds to the growing body of evidence supporting the application of deep learning techniques to routine ultrasound imaging for the detection of PPF. The CNN model developed demonstrated strong diagnostic performance, highlighting its potential to assist clinical decision-making, particularly in schistosomiasis-endemic regions where access to specialised radiological expertise is limited. With further validation, this AI-based approach could help shift fibrosis diagnosis from a subjective process to a more standardised and scalable one, thereby promoting more equitable and timely care for individuals at risk of liver complications due to schistosomiasis. In summary, our CNN achieved strong diagnostic performance for detecting PPF in ultrasound images. With further validation on larger and more diverse datasets, this approach could support earlier, more consistent diagnosis in endemic regions. Future research should extend beyond binary classification to capture fibrosis severity and improve interpretability for clinical adoption.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.; methodology, S.D. and B.A.; software, A.M.; validation, S.M.; formal analysis, A.M.; investigation, A.M.; resources, A.A.; data curation, A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.; writing—review and editing, B.A., A.N., E.W., A.A., A.E., S.M., M.E., and A.K.; visualization, A.M.; supervision, S.D. and B.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval for this secondary analysis of U-SMRC ultrasound data was obtained from the University of Essex Ethics Committee following submission of a detailed proposal.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the original U-SMRC study for their ultrasound data to be used in research, allowing for ethical secondary analysis. Written informed consent for publication was not applicable, as individual participants cannot be identified from the data.

Data Availability Statement

The de-identified individual participant data that underlie the results reported in this research are stored in a non-publicly available repository at the MRC/UVRI & LSHTM Uganda Research Unit. Data access is subject to a request and review process. Researchers wishing to access the data should submit a request outlining the data required and the intended use. Requests are reviewed by the Principal Investigator in consultation with the MRC/UVRI & LSHTM data management committee, with oversight from the UVRI and LSHTM ethics committees. In line with the MRC data sharing policy, requests will not be unreasonably refused. Researchers granted access will be required to sign a data sharing agreement restricting use to answering the pre-specified research questions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the U-SMRC study PI for approving the secondary use of data from the case-control study

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| DL |

Deep Learning |

| DNN |

Deep Neural Network |

| PPF |

Periportal Fibrosis |

| US |

Ultrasound |

| IPS |

Image Pattern Score |

| Grad-CAM |

Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping |

| ROC |

Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| AUC |

Area Under the Curve |

| ReLU |

Rectified Linear Unit |

| GPU |

Graphics Processing Unit |

| TPU |

Tensor Processing Unit |

| SVM |

Support Vector Machine |

| DICOM |

Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine |

| CT |

Computed Tomography |

| MRI |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| MRC |

Medical Research Council |

| UVRI |

Uganda Virus Research Institute |

| LSHTM |

London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine |

| USMRC |

Uganda Schistosomiasis Multidisciplinary Research Centre |

| GDPR |

General Data Protection Regulation |

| PNG |

Portable Network Graphics |

| API |

Application Programming Interface |

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of Open Access Journals |

| TLA |

Three Letter Acronym |

| LD |

Linear Dichroism |

References

- Anderson, T. J.; Enabulele, E. E. Schistosoma mansoni. Trends in Parasitology 2021, 37, 176–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunda, D. W.; Kilonzo, S. B.; Manyiri, P. M.; Peck, R. N.; Mazigo, H. D. Morbidity and mortality due to *Schistosoma mansoni* related periportal fibrosis: could early diagnosis of varices improve the outcome following available treatment modalities in sub Saharan Africa? A scoping review. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 2020, 5, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natukunda, A.; Zirimenya, L.; Nkurunungi, G.; Nassuuna, J.; Nkangi, R.; Mutebe, A.; Corstjens, P. L.; van Dam, G. J.; Elliott, A. M.; Webb, E. L. Pre-vaccination *Schistosoma mansoni* and hookworm infections are associated with altered vaccine immune responses: a longitudinal analysis among adolescents living in helminth-endemic islands of Lake Victoria, Uganda. Frontiers in Immunology 2024, 15, 1460183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrianah, G. E. P.; Rakotomena, D.; Rakotondrainibe, A.; Ony, L. H. N. R. N.; Ranoharison, H. D.; Ratsimba, H. R.; Rajaonera, T.; Ahmad, A. Contribution of Ultrasonography in the Diagnosis of Periportal Fibrosis Caused by Schistosomiasis. Journal of Medical Ultrasound 2020, 28, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J. C.; Pereira, C. L. D.; Domingues, A. L. C.; Lopes, E. P. Noninvasive diagnosis of periportal fibrosis in schistosomiasis mansoni: A comprehensive review. World Journal of Hepatology 2022, 14, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masseroli, M.; Caballero, T.; O’Valle, F.; Del Moral, R. M.; Pérez-Milena, A.; Del Moral, R. G. Automatic quantification of liver fibrosis: design and validation of a new image analysis method: comparison with semi-quantitative indexes of fibrosis. Journal of Hepatology 2000, 32, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigo, M. M.; Odermatt, P.; Nigo, D. W.; Salieb-Beugelaar, G. B.; Battegay, M.; Hunziker, P. R. Patients with severe schistosomiasis mansoni in Ituri Province, Democratic Republic of Congo. Infectious Diseases of Poverty 2021, 10, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-G.; Jun, S.; Cho, Y.-W.; Lee, H.; Kim, G. B.; Seo, J. B.; Kim, N. Deep learning in medical imaging: general overview. Korean Journal of Radiology 2017, 18, 570–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, R.; Nishio, M.; Do, R. K. G.; Togashi, K. Convolutional neural networks: an overview and application in radiology. Insights into Imaging 2018, 9, 611–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.; Sohail, A.; Zahoora, U.; Qureshi, A. S. A survey of the recent architectures of deep convolutional neural networks. Artificial Intelligence Review 2020, 53, 5455–5516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwendi, C.; Bashir, A. K.; Peshkar, A.; Sujatha, R.; Chatterjee, J. M.; Pasupuleti, S.; Mishra, R.; Pillai, S.; Jo, O. COVID-19 patient health prediction using boosted random forest algorithm. Frontiers in Public Health 2020, 8, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubaidi, L. Deep learning for medical imaging applications. Ph.D. Thesis, Queensland University of Technology, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S. K.; Greenspan, H.; Davatzikos, C.; Duncan, J. S.; Van Ginneken, B.; Madabhushi, A.; Prince, J. L.; Rueckert, D.; Summers, R. M. A review of deep learning in medical imaging: Imaging traits, technology trends, case studies with progress highlights, and future promises. Proceedings of the IEEE 2021, 109, 820–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y. A comparison of traditional machine learning and deep learning in image recognition. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series, IOP Publishing 2019, 1314, 012148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X. The role of artificial intelligence in medical imaging research. BJR Open 2019, 2, 20190031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, T.; Zhang, J.; Sun, R.; Huang, Y.; Xu, W.; Yang, S.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, H. Optical neural networks: progress and challenges. Light: Science & Applications 2024, 13, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. H.; Joo, I.; Kang, T. W.; Paik, Y. H.; Sinn, D. H.; Ha, S. Y.; Kim, K.; Choi, C.; Lee, G.; Yi, J.; et al. Deep learning with ultrasonography: automated classification of liver fibrosis using a deep convolutional neural network. European Radiology 2020, 30, 1264–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Scheich, T.; Holtfreter, M. C.; Ekamp, H.; Singh, D. D.; Mota, R.; Hatz, C.; Richter, J. The WHO ultrasonography protocol for assessing hepatic morbidity due to *Schistosoma mansoni*: Acceptance and evolution over 12 years. Parasitology Research 2014, 113, 3915–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpata, R.; Neumayr, A.; Holtfreter, M. C.; Krantz, I.; Singh, D. D.; Mota, R.; Walter, S.; Hatz, C.; Richter, J. The WHO ultrasonography protocol for assessing morbidity due to *Schistosoma haematobium*: Acceptance and evolution over 14 years. Systematic review. Parasitology Research 2015, 114, 1279–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uganda Schistosomiasis Multidisciplinary Research Center. Building expertise and understanding of the underlying biological determinants of severe schistosomal morbidity and developing appropriate interventions for prevention and management. Online Resource. 2022. Available online: https://www.muii.org.ug/usmrc/ (accessed on 18 January 2024).

- The Compass for SBC. Bilharzia Campaign in Uganda. 2014. Available from: https://thecompassforsbc.org/sbcc-spotlights/bilharzia-campaign-uganda [Accessed: 5 Sep 2025]. Available online: https://thecompassforsbc.org/sbcc-spotlights/bilharzia-campaign-uganda (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- IBM Cloud Education. What Is Supervised Learning? Available online: https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/supervised-learning (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Government of Uganda. Data Protection and Privacy Act. 2019. Available online: https://ict.go.ug/ims/public/site/documents/Data-Protection-and-Privacy-Act-2019.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- European Union. General Data Protection Regulation (ict). 2016. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:02016R0679-20160504 (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Chollet, F. Deep Learning with Python. 2021; Simon and Schuster.

- Kushwaha, U.; Gupta, P.; Airen, S.; Kuliha, M. Analysis of CNN Model with Traditional Approach and Cloud AI based Approach. 2022 International Conference on Automation, Computing and Renewable Systems (ICACRS); IEEE, 2022; pp. 835–842. [Google Scholar]

- Arif, M.A. Understanding VGG16: Powerful Deep Learning Model for Image Recognition. 2023. Available online: https://smuhabdullah.medium.com/understanding-vgg16-a-powerful-deep-learning-model-for-image-recognition-d40b074fd01c (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Qassim, H.; Verma, A.; Feinzimer, D. Compressed residual-VGG16 CNN model for big data places image recognition. 2018 IEEE 8th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC); IEEE, 2018; pp. 169–175. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, K. Demystifying Logistic Regression: A Deep Dive. 2024. Available online: https://medium.com/@josephkiran2001/demystifying-logistic-regression-a-deep-dive-7c41ed510305 (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Keras Team. EarlyStopping Callback. 2025. Available online: https://keras.io/api/callbacks/early_stopping/ (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Basha, S. H. S.; Dubey, S. R.; Pulabaigari, V.; Mukherjee, S. Impact of fully connected layers on performance of convolutional neural networks for image classification. Neurocomputing 2020, 378, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Géron, A. Hands-On Machine Learning with Scikit-Learn, Keras, and TensorFlow, 2nd ed.; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, CA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kufel, J.; Bargieł-Łączek, K.; Kocot, S.; Koźlik, M.; Bartnikowska, W.; Janik, M.; Czogalik, Ł.; Dudek, P.; Magiera, M.; Lis, A.; Paszkiewicz, I. What is machine learning, artificial neural networks and deep learning?—Examples of practical applications in medicine. Diagnostics 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çorbacıoğlu, Ş. K.; Aksel, G. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis in diagnostic accuracy studies: A guide to interpreting the area under the curve value. Turkish Journal of Emergency Medicine 2023, 23, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ockenden, E.S.; Frischer, S.R.; Cheng, H.; Noble, J.A.; Chami, G.F. The role of point-of-care ultrasound in the assessment of schistosomiasis-induced liver fibrosis: A systematic scoping review. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2024, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).