1. Introduction

Recent years have witnessed rapid progress in the Internet of Things (IoT), edge computing, and cloud computing. Breakthroughs in artificial intelligence (AI), especially deep learning (DL), have further accelerated this trend [

1,

2]. Edge intelligence (EI), which integrates AI with edge computing, has shown great potential to overcome limitations of traditional cloud-based AI systems [

3]. AI model deployment on edge devices enables autonomous and resilient systems for smart cities [

4], while the integration of AI into edge platforms provides additional key benefits [

5]. First, edge computing enables AI models to operate locally, facilitating real-time processing with minimal latency. Second, performing computations closer to the data source enhances data privacy by reducing the need to transmit sensitive information to centralized servers [

6]. Moreover, decreasing reliance on cloud services lowers data transmission costs and mitigates network bandwidth limitations, thereby improving the scalability and efficiency of AI applications [

7]. While we primarily consider edge intelligence (EI) as the general application scenario, the proposed framework is equally applicable in cloud-based environments.

Advancing AI to distributed edge platforms introduces significant security challenges due to the dynamic and heterogeneous nature of edge computing. Typically, cloud servers manage pretrained AI models and deploy them to remote edge environments. However, models on edge platforms are susceptible to model theft attacks, such as model extraction or weight stealing, which can replicate a model’s functionality and lead to intellectual property (IP) infringement [

8]. In addition, an adversary also launches poisoning attacks on original models, such as manipulating the training data or the model parameters [

9]. As a result, these unauthorized AI models can be published on AI model marketplaces and then integrated into diverse smart applications. These issues not only compromise the model’s commercial value and security but they also undermine the trustworthiness and reliability of AI ecosystems. Therefore, AI model authenticity and ownership verification are critical to protect model IP and prevent unauthorized access and even malicious use.

The fundamental concept of AI model ownership verification is to embed a specific pattern or structure into the model as a unique identifier (watermark), which can later be extracted to demonstrate ownership when necessary during the inference stage [

10]. The verification process typically involves three key phases: watermark embedding, extraction, and validation [

11]. In the embedding phase, watermark information is incorporated into the model either during training or through post-processing to establish ownership. Embedding techniques can operate at the parameter level, such as encoding the watermark within model weights, or at the functional level, such as introducing a trigger-based watermark that produces specific outputs for designated inputs [

12]. Furthermore, the embedding process must ensure imperceptibility, meaning that the watermark does not degrade the model’s performance on its primary task.

During the watermark extraction phase, predefined methods are used to retrieve the watermark from the target model during inference or auditing. If the extracted watermark matches the original one, ownership of the model can be verified [

13]. The extraction method typically corresponds to the embedding technique; for example, if the watermark is encoded within model weights, specific parameter patterns must be analyzed to extract it, whereas trigger-based watermarks require feeding specially crafted inputs to activate the watermark response [

14]. Finally, in the ownership verification phase, the extracted watermark is compared against the original to confirm the model’s legitimacy. This verification process should have legal enforceability, allowing it to serve as valid evidence in intellectual property protection. Additionally, the watermark must be robust against various attacks, such as model compression, fine-tuning, pruning, and adversarial attacks, ensuring that it remains intact and detectable even after modifications. An ideal model watermarking technique should meet several core requirements. First, it must exhibit robustness, meaning that the watermark remains extractable even if the model undergoes modifications such as pruning or fine-tuning [

15]. Second, the embedding should be imperceptible, ensuring that it does not degrade the model’s normal task performance. Furthermore, the watermark should possess security, making it difficult for attackers to remove, forge, or alter the embedded information. Finally, the ownership verification process must be efficient, ensuring that watermark embedding and extraction incur minimal computational overhead, making it suitable for resource-constrained edge devices [

16,

17,

18].

Currently, backdoor-based watermarking methods are among the most advanced techniques for ownership verification [

14]. These methods rely on backdoor trigger mechanisms, embedding watermarks by injecting backdoors into models so that they produce predetermined responses when exposed to specific trigger samples. However, despite their effectiveness, backdoor-based watermarking fundamentally relies on poisoning the model, introducing additional security risks [

19]. For instance, if an attacker discovers the trigger pattern, they could exploit the backdoor to launch adversarial attacks against the model. Additionally, even if the trigger pattern has a minimal impact, it may still cause unexpected erroneous predictions, affecting the model’s reliability. Moreover, as research on backdoor detection advances, backdoor-based watermarking techniques may become increasingly susceptible to detection and removal, compromising their long-term effectiveness.

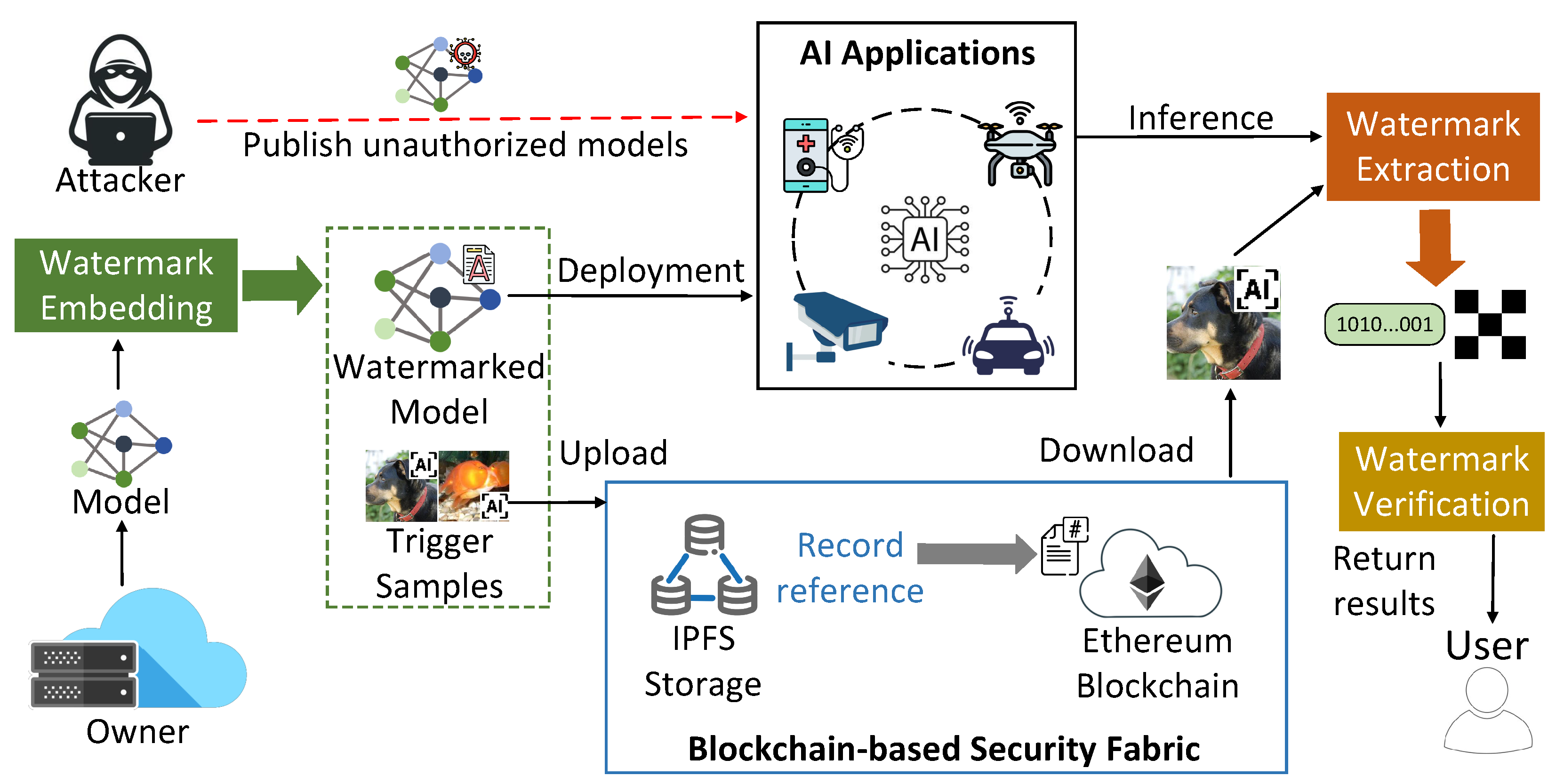

Our Work. To solve these challenges, we propose BIMW, a novel blockchain-enabled innocuous model watermarking framework for secure ownership verification of AI models within distributed AI application ecosystems. As

Figure 1 shows, owners rely on cloud servers to manage pretrained models and deploy models for authorized users. However, an adversary can publish unauthorized models (copied or manipulated) in AI applications. To ensure verifiable and robust model ownership verification, BIMW introduces an interpretable watermarking (IW) method that avoids model poisoning while maintaining robustness. Instead of embedding watermarks directly into model outputs, the cloud server (model owner) employs feature impact analysis algorithms to generate interpretation-based watermarks, along with corresponding trigger samples. Ownership is verified by using these trigger samples for the model inference and then comparing the resulting interpretations with the original watermark. Thus, users can confirm that models are published by trusted sources with authorized permissions.

To further enhance security and transparency of model ownership verification under a distributed network environment, BIMW integrates a blockchain-based security fabric that ensures the integrity and auditability of watermark data, models, and trigger samples during storage and distribution. As the bottom of

Figure 1 shows, model owner saves models and trigger samples into a IPFS-based distributed storage and then records their reference information on a Ethereum Blockchain. Upon model deployment and inference stages, users (or owners) use reference information to identify any tampered models or trigger samples. Therefore, BIMW offers a decentralized, secure, and reliable alternative to traditional backdoor-based watermarking methods. Our implementation is publicly available at

https://github.com/Xinyun999/BIMW.

The primary contributions are outlined as follows:

- 1)

We propose the system architecture of BIMW, a blockchain-enabled innocuous model watermarking framework that ensures secure and trustworthy AI model deployment and sharing in distributed edge computing environments.

- 2)

We demonstrate a Innocuous Model Watermarking method, which consists of IW embedding and feature impact analysis for watermark extraction.

- 3)

We strengthen the data transmission security and transparency of watermark data, models, and trigger samples by using blockchain encryption technology.

- 4)

We conduct comprehensive experiments by applying BIMW to various AI models. The results demonstrate its effectiveness and resistance against both watermark-removal and adaptive attacks and efficiency of model data authentication and ownership verification at edge computing platforms.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 provides a brief overview of existing solutions for deep learning model watermarking and ownership verification. We also briefly describe interpretable machine learning techniques and Blockchain technology.

Section 3 presents system framework of innocuous model watermarking method, emphasizing the synergic integration of IW and feature impact analysis (FIA) for watermark embedding, extraction, and ownership verification.

Section 4 describes the prototype implementation and shows the experimental results to verify the effectiveness and performance of applying BIMW on edge computing platforms. Finally,

Section 5 concludes this paper with a summary and some discussions about ongoing efforts.

3. Methodology

In this section, we provide details of BIMW framework, especially for two sub-frameworks: Interpretable Watermarking (IW) model and Blockchain-based data verification. Building upon [

15], our BIMW further enhances this line of work by improving both robustness and trustworthiness. In contrast to the previous scheme, our approach not only achieves better concealment and ownership verification but also strengthens the data transmission security and transparency of watermark data, models, and trigger samples through blockchain-based encryption technology.

3.1. Insight of Interpretable Watermarking

As discussed in

Section 1, traditional backdoor-based watermarking techniques rely on model poisoning, which can introduce security risks and unintended behaviors. To address these challenges, we pose a critical question: Is there an alternative space where we can embed an inconspicuous watermark without affecting model predictions? Drawing inspiration from Interpretable Machine Learning (IML) and feature impact analysis (FIA), we propose Interpretable Watermarking (IW). Our key idea is that, rather than embedding watermarks directly within the model’s predicted classes, we can utilize the interpretations generated by FIA algorithms as a hidden medium for watermarking.

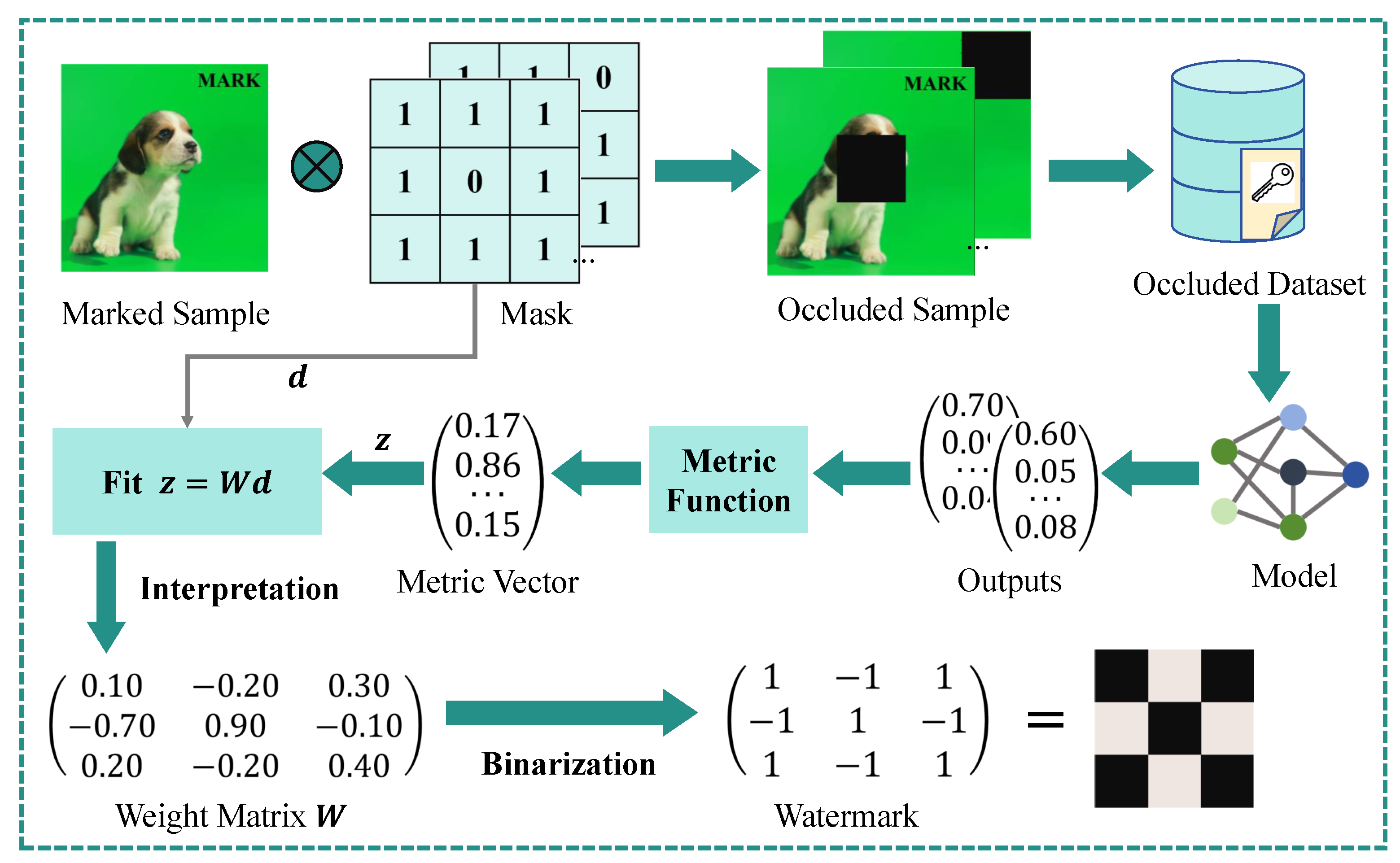

Figure 2 presents an overview of the interpretable watermarking framework and contrasts it with conventional backdoor-based methods. Unlike approaches that modify a model’s predicted class when a marked sample is introduced, IW employs feature impact analysis techniques to derive interpretations for these samples, embedding the watermark within these interpretability outputs. The IW process consists of three distinct phases: (1) embedding the watermark, (2) extracting the watermark, and (3) verifying ownership. Furthermore, we integrate blockchain technology to ensure the immutability and auditability of watermarked model records.

3.2. Embedding the Watermark

As discussed in

Section 1, an ownership verification mechanism aims to achieve three key objectives: effectiveness, robustness, and innocuous. During the watermark embedding phase, the watermark information is embedded into the model by adjusting the parameters

of the trained model during training to establish ownership. Moreover, the model’s original performance must be maintained after embedding the watermark [

15]. Thus, the watermark embedding process can be framed as a multi-objective optimization problem based on these criteria, which is formally expressed as follows:

where

denotes the parameters of the model and

represents the target watermark. The data

and labels

c correspond to the clean dataset, whereas

and

represent the data and labels of the watermarked set. In our proposed method, the true labels of

are taken as

, while backdoor-based approaches rely on targeted, but incorrect, labels. The function Interpret(.) refers to an interpretability-based feature impact analysis technique employed in our watermarking method for watermark extraction, which will be detailed in

Section 3-C.

denotes a coefficient. Equation (

1) consists of two components. The first term,

, represents the model’s loss function on the primary task, ensuring that the predictions on both the clean and marked datasets remain consistent, thus preserving the model’s performance. The second term,

, measures the discrepancy between the output interpretation and the target watermark. By optimizing

, the model can align the interpretation more closely with the watermark. We use a hinge-like loss function for

because it has been shown to enhance the watermark’s resilience against removal attacks. The hinge-like loss function is expressed as follows:

where

. The symbols

and

represent the

elemenets of

and

respectively. The parameter

serves as a control factor, promoting the absolute values of the elements in

to exceed

. By optimizing Equation (

2), the watermark is embedded into the sign of the interpretation

.

3.3. Extracting the Watermark via Feature Impact Analysis

The goal of embedding a model watermark is to determine the optimal set of model parameters, denoted as

, that minimizes Equation (

2). To leverage the widely used gradient descent algorithm for this optimization, it is essential to develop a differentiable and model-agnostic method for feature impact analysis. Drawing inspiration from the well-known Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME) algorithm, we propose a LIME-based watermark extraction technique that generates feature impact interpretations for the trigger sample. LIME operates by generating local samples around a given input data point and assessing the significance of each feature based on the model’s outputs for these samples. We adopt this fundamental idea while introducing modifications to tailor the algorithm for watermark embedding and extraction. The overall workflow of our watermark extraction approach is illustrated in

Figure 3. Generally, the LIME-based watermark extraction process consists of three key phases: (1) regional sampling, (2) model prediction and assessment, and (3) obtaining the interpretation.

Phase 1: regional Sampling. Given that the input , regional sampling aims to generate multiple samples that are locally adjacent to the trigger sample . To begin, the input space is divided into n fundamental segments based on the length of the watermark . Neighboring features are grouped into a single segment, with each segment containing features. Irrelevant features are excluded, as the goal is to extract a watermark rather than interpret all the features.

The core idea behind our algorithm is to determine which features have the greatest impact on the prediction of a data point by systematically masking these fundamental components. To achieve this, we first randomly generate s masks, denoted as M. Each mask in M is a binary vector (or matrix) of the same size as . We refer to the mask in M as , where for each i, . Each element within a mask corresponds to a specific component of the input.

Next, we generate the masked samples

by applying random masks to the key components of the trigger sample, thereby creating a dataset. This masking process is represented by ⊗,

. Specifically, if the corresponding mask element

is 1, the related component in the input retains its original value. If

is 0, the component is replaced with a predefined value. Examples of the masked samples can be found in

Figure 3.

Phase 2: Model Prediction and Assessment. During this phase, the masked dataset generated in Phase 1 is fed into the model, and the predictions

for the masked samples are obtained. In label-only settings, the predictions

y are binarized to either 0 or 1, depending on whether the sample is classified correctly. Subsequently, a metric function

is used to assess the accuracy of the predictions in comparison to the ground-truth labels

, and the metric vector

for the

s masked samples is computed according to Equation (

3).

The metric function, denoted as , must be differentiable and capable of offering a quantitative assessment of the output. It can be tailored to suit specific deep learning tasks and prediction types. Given that most deep learning tasks typically have a differentiable metric function (such as a loss function), IW can be readily adapted for use in a wide range of deep learning applications.

Phase 3: Obtaining the Interpretation. Once the metric vector

v is computed, the final phase of the watermark extraction process involves fitting a linear model to assess the significance of each component and determine their corresponding importance scores. We treat the metric vector

v as

z and the masks

M as

d. In practice, we apply ridge regression to enhance the robustness of the resulting weight matrix across various local samples. The weight matrix

W, obtained through ridge regression, reflects the importance of each component. This weight matrix

W for the linear model can be derived using the normal equation, as shown in Equation (

4).

where

denotes a hyper-parameter.

represents an

identity matrix. The watermark is embedded into the sign of the elements within the weight matrix. During the embedding process, we define the weight matrix

W as

to optimize the watermark embedding loss function in Equation (

1). As stated in Equation (

4), the derivative of

W with respect to

v exists, and since the derivative of

v with respect to the model parameters

is also well-defined in DNN, the entire watermark extraction algorithm remains differentiable based on the chain rule. Thus, the watermark can be embedded into the model by leveraging the gradient descent algorithm to optimize Equation (

1).

To further acquire the extracted watermark

, we binarize the weight matrix

W by applying the following binarization function bin(·).

where

and

are the

i-th element of

and

W.

The key to applying watermark extraction across various tasks lies in designing the masking operation rule, denoted by ⊗, and the metric function

. The masking operation is responsible for generating the masked samples, while the metric function evaluates the quality of predictions. To illustrate, we present an example implementation with image classification models, as shown in

Figure 3. Specifically, the masking operation sets the pixels in the masked region to 0, while retaining the original values for the remaining pixels. Moreover, the metric function can be defined as the output that provides the predicted probability for the ground-truth class label.

3.4. Verifying Ownership

If the model owner identifies a suspicious model deployed by an unauthorized entity, they can determine whether it is a copy of the watermarked model by extracting the watermark from the suspicious model. The extracted watermark is then compared to the original watermark held by the model owner. This procedure is known as the ownership verification process for DNN models. For a suspicious model

, the model owner will begin by extracting the watermark

using trigger samples and the watermark extraction algorithm based on feature impact analysis, as detailed in

Section 3-C. The task of comparing

with

is framed as a hypothesis testing problem, outlined as follows.

Theorem 1. Let represent the watermark extracted from the suspicious model, and denote the original watermark. We define the null hypothesis as: is independent of , and the alternative hypothesis as: is related or associated with . The suspicious model can only be considered an unauthorized copy if is rejected.

To verify ownership, we apply Pearson’s chi-squared test and determine the corresponding p-value. If this p-value falls below a predefined significance threshold

, the null hypothesis is dismissed, confirming the model as the rightful intellectual property of its original owner. The ownership verification procedure is outlined in pseudocode form in Algorithm 1.

|

Algorithm 1:Ownership verification via hypothesis testing. |

-

Require:

Trigger set , suspicious model , reference watermark , significance level . -

Ensure:

Boolean flag indicating whether ownership is verified. - 1:

- 2:

- 3:

- 4:

ifthen

- 5:

return True - 6:

else - 7:

return False - 8:

end if |

3.5. Blockchain-based Data Verification

Both owners and users can rely on a Blockchain fabric to verify integrity of model data during storage and sharing. The Blockchain fabric uses IPFS [

30] as distributed storage for model data distribution. The owner

i can publish a model data which includes a watermarked model

and associated trigger sample images

where

k is the count of trigger sample images. After successfully uploading a model data onto IPFS network, the data owner can receive a set of unique hash-based Content Identifiers (CIDs), which can retrieve model data from IPFS network. The reference of a model data is represented as a Merkle tree of CIDs of watermarked model and trigger sample, which denotes as

. where

D represents a CID. Finally, a sequential list of CIDs

along with its merkle root

will be saved on Blockchain through smart contracts.

At model retrieval stage, model users call smart contract’s function to query D and from Blockchain. To verify the integrity of model data, the user simply reconstruct a Merkle tree of D and calculate its root hash . Any Modification on the sequential order of D or content of watermarked model and trigger sample images will lead to a different root hash value of the Merkle tree. Thus, integrity of received model data can efficiently verified by comparing with proof information recorded on the Blockchain.

4. Experimental Results

In this section, we implement IW in a widely used deep learning task: image classification. We assess its effectiveness, safety, and uniqueness based on the objectives defined in

Section 1. In addition, we also evaluate latency incurred by different operation stages in the model data sharing and authentication process. Furthermore, we examine IW’s robustness against different watermark removal attacks.

Experimental Setup. The model is trained on using PyTorch and executed on four NVIDIA Tesla V100 GPUs. After obtaining the pre-trained model, we deployed it on a Jetson Orin Nano Super Developer Kit [

31]. The Jetson Orin Nano is widely recognized as an effective edge device across various research domains, particularly in artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, computer vision, and embedded systems. Its combination of high computational power and energy efficiency makes it a suitable choice for real-time processing at the edge. We also implemented a prototype of Blockchain-based security fabric. We use Solidity [

32] to develop smart contracts that record reference information of model and it samples and verify data integrity during sharing. Ganache [

33] is used to set up a development Ethereum blockchain network. Truffle [

34] is used to compile smart contracts and then deploy binary code on the development Blockchain network. We setup a private IPFS [

35] network to simulate a distributed storage.

Watermark Definition. In the hypothesis test, we define the significance level as

, meaning that if the p-value falls below 0.01, the null hypothesis is rejected. Besides, we compute the watermark success rate (WSR) to assess the similarity between the extracted and original watermarks. The WSR represents the proportion of bits in the extracted watermark that correctly match those in the original. It is defined by the following equation.

where

n represents the length of the watermark, and

denotes the indicator function. A lower p-value and a higher WSR indicate that the extracted watermark

closely resembles the original watermark

, signifying a more effective watermark embedding process.

4.1. Performance Evaluation on Image Classification Models

In this section, we perform experiments on the CIFAR-10 and a subset of the ImageNet datasets using the widely used convolutional neural network (CNN), ResNet-18. CIFAR-10 is a 10-class image classification dataset consisting of color images. For the ImageNet dataset, we randomly select a subset of 80 classes, with 500 training images and 100 testing images per class. The images in ImageNet are resized to . Initially, we pre-train the ResNet-18 models on both the CIFAR-10 and ImageNet datasets for 400 epochs. Afterward, we fine-tune the models for 40 epochs to embed the watermark using IW. In line with the original LIME paper, we use the predicted probability of each sample’s target class to form the metric vector v.

To assess the performance of IW, we implement various trigger set construction techniques inspired by different backdoor watermarking methods. These include: (1) Noise, where Gaussian noise is used as the trigger sample; (2) Patch, where a meaningful patch (e.g., ’MARK’) is inserted into the images; and (3) Black-edge, which involves adding a black border around the images.

To assess both Effectiveness and Innocuity, The

Table 1 and

Table 2 reports the model’s prediction accuracy (Pred Acc), the p-value from a hypothesis test assessing the statistical significance of accuracy differences, and the watermark success rate (WSR) under three different types of watermark triggers: Noise, Patch, and Black-edge. The watermark length varies from 32 to 256.

Across all experiments in

Table 1 and

Table 2, the baseline accuracy of the unwatermarked model (No WM) remains consistently at 91.36% for the CIFAR-10 dataset and 75.81% for the ImageNet dataset. When watermarks are embedded, the prediction accuracy shows only a negligible decline, indicating minimal impact on classification performance. The largest deviation is observed with the Black-edge trigger of length 48 in

Table 1, where the accuracy slightly drops to 91.12%.

The p-values are consistently low, ranging from

to

in

Table 1, which are significantly lower than the threshold

. Furthermore, the WSR values are remain close to 1.000, indicating a nearly 100% success rate in watermark embedding and extraction across all configurations. The chi-squared test statistic is approximately proportional to

, where

n represents the watermark length. Consequently, as

n increases, the p-value correspondingly decreases. These findings clearly validate the effectiveness of IW in embedding watermarks into models while preserving classification accuracy.

To analyze the differences from Backdoor Watermarks, we conduct a comparative experiment, as shown in

Table 3 and

Table 4. To assess the level of harmlessness, we introduce the harmless degree

H as an evaluation metric. Specifically,

H is determined based on the accuracy obtained from both the benign testing dataset (

x,

y) and the trigger set (

,

) using their respective ground-truth labels, as defined below:

where the function

consistently outputs the ground-truth label for

I. A larger

H means the watermarks have less effect on the utility of the models.

As presented in

Table 3 and

Table 4, our IW outperforms backdoor-based methods, as reflected in its higher harmlessness degree

H. For instance, with a trigger size of 256, our IW achieves an

H value approximately 5.5% higher than that of backdoor-based watermarking techniques, demonstrating its effectiveness, which is comparable to or even surpasses that of baseline backdoor-based approaches.

4.2. Resilience Against Watermark Removal Attacks

Once adversaries acquire the model from external sources, they may employ different strategies to eliminate watermarks or bypass detection. In this section, we assess whether our IW can withstand such attempts. We specifically examine two types of attacks: fine-tuning and model pruning. Fine-tuning involves training the watermarked model on a local benign dataset for a limited number of epochs. In this type of attack, an adversary seeks to eliminate the embedded watermark by fine-tuning the model. On the other hand, model pruning can act as a watermark-removal attack by eliminating neurons associated with the watermark. In this study, we perform pruning by setting to zero the neurons with the smallest norm. Specifically, the pruning rate represents the fraction of neurons that are removed.

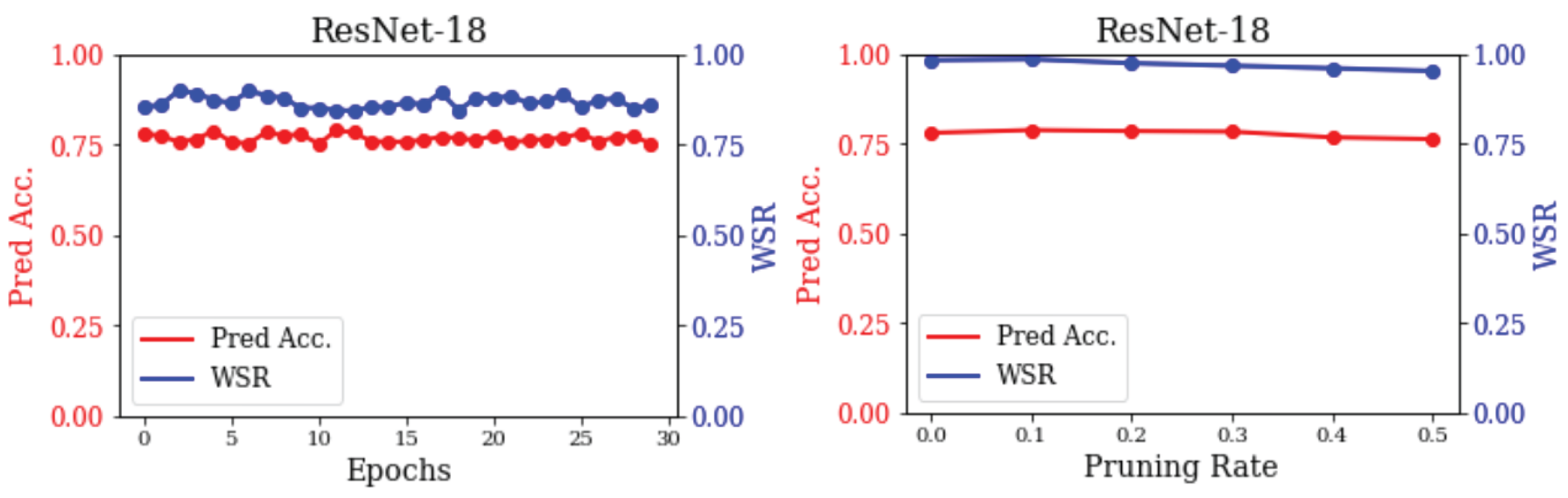

As shown in

Figure 4, we firstly test the resilience against fine-tuning attack (left). We fine-tune IW-watermarked models for 30 epochs using the testing set, achieving a WSR exceeding 0.84. These findings highlight the robustness of our IW against fine-tuning attacks. We attribute this mainly to preserving the original labels of watermarked samples during training, which minimizes the impact of fine-tuning compared to backdoor-based approaches. Then, we evaluate the resilience against model-pruning attack (right). As the pruning rate increases, the prediction accuracy of ResNet-18 declines, demonstrating a reduction in the model’s effectiveness. Nevertheless, the WSR remains above 0.9. These findings indicate that our IW withstands the model-pruning attack.

4.3. Latency of Model Data Authentication

We evaluate time latency of BIMW for model data authentication consisting of six stages. It needs three stages to publish model and samples at model owner side: 1) Watermark embedding; 2) Publish model data onto IPFS; 3) Record reference on Blockchain. The user needs three stages to verify model data integrity and model ownership: 4) Query reference from Blockchain; 5) Retrieve model data from IPFS and verify integrity; 6) Watermark extraction. We conducted 50 Monte Carlo test runs for each test scenario and used the averages to measure the results.

Table 5 shows time latency incurred by key stages of BIMW during model authentication process. All test cases are conducted on Jetson Orin Nano platform. The watermark embedding process takes an average of 0.11 s to create interpretable watermarked model on the owner’s side. At model users’ side, it takes about 0.02 s to extract watermarks by using trigger sample images and verify model’s ownership. The numeral results demonstrate efficiency of running the proposed innocuous Model watermarking method under the edge computing environment.

We use 10 trigger sample images (about 86 Bytes per figure) and a watermarked model (about 43.7 MB) to evaluate delays incurred by model data distribution and retrieval atop the Blockchain fabric. Due to the large size of watermarked model, it takes about 4.5 s to upload model data to the IPFS network. However, retrieving model data from the IPFS network only introduces small delays (about 0.7 s). The latency of recording reference through smart contracts is greatly impacted by the consensus protocol. It takes about 1.36 s to save reference on test Ganache network. In contrast, querying reference from Blockchain takes much less time (about 0.5 s). We can see fact that publishing data on Blockchain fabric cause more delays (5.86 s) than verification process (1.19 s). However, these overheads only occur once when owners firstly publish and distribute their model data. In sum, our solution brings lower latency during model data retrieval and verification procedures on edge computing platforms.