1. Introduction

Dealing and engaging with digital data is part of everyday research and course life for all students. Students from all faculties use and generate data and are repeatedly confronted with questions of data management, data evaluation and interpretation, as well as the ethical handling of data and data protection. However, students often do not yet have sufficient skills and lack basic knowledge and practical data literacy at a higher level [

4,

5]. Data literacy enables students to critically analyze and interpret data and, based on this, make informed decisions [

6]. It promotes critical thinking, problem-solving skills, and the ability to formulate evidence-based arguments [

7,

8,

9].

In order to systematically anchor data literacy and thus the appropriate and ethical handling of data in the curricula of the degree programs at TH Köln, the Data Literacy Initiative (DaLI) was launched as a research project in 2020. The Data Literacy Basic Course is one of several courses developed by DaLI to elevate a highly heterogeneous student body to an uniform baseline level of data literacy. In the Data Literacy Basic Course, which has been offered at TH Köln on an interdisciplinary and cross-semester basis since 2021, students from all faculties have the opportunity to acquire basic data skills. They are sensitized to the relevance of data, recognize a wide range of possible applications, and learn to deal with data in a well-founded and critical manner. To this end, they apply relevant process steps, including those related to the research data cycle, by working independently on an open data project throughout the course.

The evaluation of the DaLI basic course at the beginning and end of the course shows where students – according to their own assessment – achieve the greatest increase in competence. The evaluation is carried out using various methods, including quantitative surveys on self-assessment of data literacy before and after attending the course and qualitative evaluations by students after the course. Among other things, the evaluation revealed particular gaps in students’ knowledge in the area of “publishing data”, a topic that is originally a library subject. Franke et al. ([

2], p.192) describe how academic libraries offer numerous other training courses and workshops in addition to their focus on information literacy. They state that this offering can be particularly successful in cooperation with other institutions, enabling libraries to become partners in promoting future skills such as digital and data literacy or even AI (in the scientific work process). The basic course in data literacy at TH Köln was also developed in cooperation with the university library in several areas of expertise related to the data life cycle.

2. Theoretical Background

Data literacy supports the responsible and prudent handling of data and, due to the growing volume of data, is described as an essential and comprehensive skill for all situations, sectors, and disciplines [

7,

10]. Data literacy is defined as the ability to critically collect, manage, evaluate, and apply data (cf. Ridsdale et al. [

6], p.3). Through the professional and critical use, analysis, and interpretation of data, data literacy aims to help identify issues and develop appropriate solutions for global economic and social phenomena. Schüller et al. (2019) see data literacy as a key competence of the 21st century and describe it as “a cluster of all efficient behaviors and attitudes for the effective fulfillment of all process steps for value creation or decision-making from data” [

8]. On the one hand, data skills are necessary in order to be able to use data professionally and optimally in a specific subject and research area, both at university and in later professional life (cf. ibid., p. 16).

2.1. Areas of Competence in Data Literacy

In order to integrate academic libraries into data literacy training, it is helpful to include models for structuring and describing the underlying competencies and tasks. competence frameworks and models provide guidance by identifying the elements that are necessary to act effectively in a specific area of responsibility [

9]. In the higher education context, they describe which areas of data literacy are necessary in a basic course of study in order to provide students entering an increasingly data-dependent working world with a sound basis for action [

6,

9].

Based on an extensive literature review, Ridsdale et al. developed a competence matrix that summarizes the core skills and competencies of data literacy. In total, this matrix describes 23 competencies and the associated skills, knowledge, and expected tasks (64 in total), which are divided into five competence areas: “Conceptual Framework,” “Data Collection,” “Data Management,” “Data Evaluation,” and “Data Application” [

6, p.3]. Examples of such competencies include data discovery and collection, data organization, data manipulation, data visualization, and others. The “Data Application” competence area includes competencies such as critical thinking, data culture, and data ethics. The competence matrix developed by Ridsdale et al. forms the basis for other studies [i.e.,

4]. Schüller et al. [

9] also use this as a basis for their data literacy framework, which encompasses the competencies necessary for decision-making and knowledge development when dealing with data. The cyclical process model divides the respective process steps and the associated competencies into productive and receptive steps. The productive area encompasses competencies that are necessary for deriving data products from the available data. The receptive area maps skills and tasks that are necessary for decoding data projects and uncovering the underlying data. The respective skills are divided into “basic level,” “advanced level,” and expert level” [

9, pp. 33-34].

2.2. Libraries as Cooperation Partners in Teaching Data Literacy

The role of libraries in teaching data literacy is viewed in different ways. The spectrum ranges from the use of premises as scientific infrastructure and training facilities to the actual integration of library-specific content, i.e., to concrete participation and input. The question is by no means new. As early as 2004, Schield [

11] called for an expanded role for libraries: They should go beyond traditional information transfer and also become active in the fields of data and statistical literacy, because these skills are central to critical and evidence-based work. He argues that the three literacies – information literacy, statistical literacy, and data literacy – are closely linked and interdependent. He sees librarians as traditionally responsible for teaching information literacy and recommends that librarians and libraries should also integrate statistical literacy into their teaching programs in the future in order to enable students to deal critically with data and its statistical evaluation.

Almost 10 years later, Calzada and Marzal [

12] saw the integration of libraries into the field of data literacy in the following five key areas: understanding data / finding and obtaining data / interpreting and analyzing data / data management / communicating and presenting data. Communication was broadly defined, as it also included the presentation and dissemination of data, including visualization, citation, and sharing of data, as well as ethical aspects of data handling (e.g., data protection, copyright). Since the handling of research data and its provision, indexing, and retrieval was still much less developed, this area is not mentioned. Instead, according to Calzada and Marzal, these five fields form the framework according to which libraries should structure and design their data literacy offerings.

The data literacy study by the Higher Education Forum on Digitalization also examines approaches to teaching data literacy and confirms the active involvement of academic libraries as key partners in higher education. On the one hand, it states that teaching data literacy skills should begin as early as possible in the course of study and that various models of integration are conceivable. [

7, p. 8f] All of the teaching options examined were interdisciplinary and collaborative with other institutions.

Since the beginning of the Data Literacy Initiative (DaLI) at TH Köln, libraries have been actively involved in the curricular and extracurricular teaching of data literacy. The initiative was scientifically monitored and documented, and it teaches data literacy skills with the direct involvement of library staff. The study by Fühles-Ubach et al. [

13] suggests that libraries could take on specific content-related tasks in the areas of “establishing data culture,” “providing data,” and “publishing data,” thereby assuming key roles within data literacy education. The extent to which these assumptions can be implemented will also be determined by the evaluation of the courses.

The current working paper by Demiroez and Laemmlein [

14] analyzes studies on the integration of data literacy into university curricula and explicitly states that university libraries are key players in teaching this future-oriented skill. Various approaches and competency frameworks are presented, such as that of Calzada and Marzal [

12], which defines the five central areas in which libraries promote data literacy. The working paper summarizes the state of research and assesses libraries as “key institutions” that impart empirically verifiable competencies in practice.

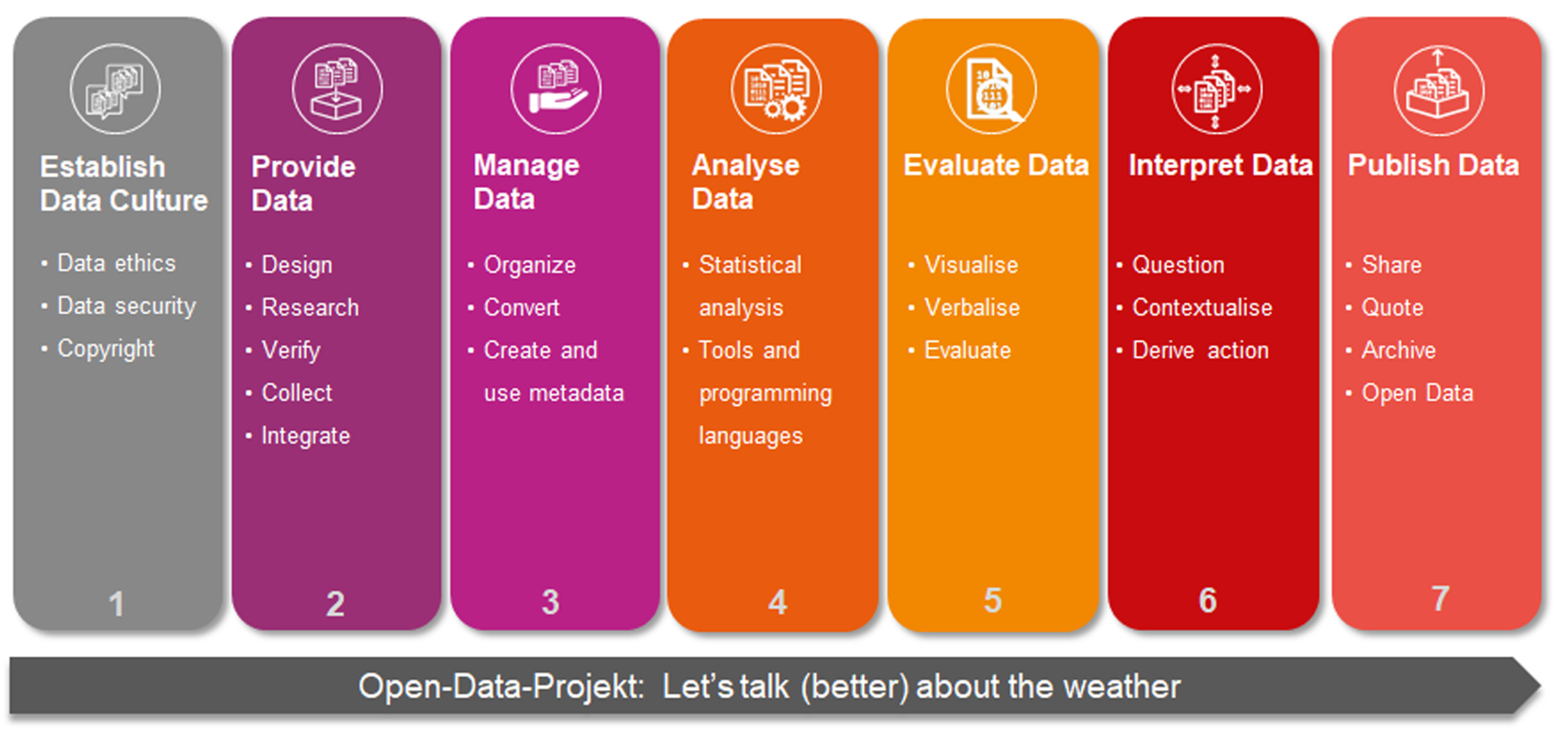

2.3. The DaLI Competence Model of the TH Köln

The DaLI competence model is based on the data literacy competence matrix of Ridsdale et al. and the data literacy framework of Schüller et al. and integrates the research data life cycle to emphasize the importance of data literacy in the higher education and research context. The research data life cycle describes the management of research data from collection and storage to use, archiving, or publication. The integration of the research data life cycle emphasizes scientific work with research data at universities and university libraries, in contrast to everyday data or data from a business context. Here, the data lifecycle often ends with the storage of data, whereas in the research data lifecycle, the indexing, citation, and sharing of data (as open data) also play an important role. This enables an action- and process-oriented approach to the development and implementation of teaching and learning units on data literacy. Special features of the DaLI competence model are therefore the competence areas “Establishing a data culture” and “Publishing data.” Both are directly linked to central topics of academic libraries. The overarching competence area “Establishing a data culture” includes “data ethics,” “data protection,” and “copyright” and should be seen as the basis for all other competence areas. The competence area “Establishing a data culture” is the core value of the competence model and highlights the importance of data-conscious and responsible handling of data. The competence area “Publishing data” describes university-specific features in the handling of research data. The focus is on the open reuse and recycling of data as well as its adequate archiving and publication. The DaLI competence model is therefore divided into seven competence areas aligned with the research data life cycle: “Establishing a data culture,” “Providing data,” “Managing data,” “Evaluating data,” “Interpreting data,” “Classifying data,” and “Publishing data,” each of which summarizes a variety of detailed competencies (cf.

Figure 1).

2.4. Evaluation of Data Literacy and Comparable Research

In their study on the development of a competency framework, Schüller and Busch examine measurement instruments for data literacy in higher education and divide them into: instruments for measuring response, instruments for measuring learning success, instruments for measuring behavior, and procedures for evaluating results. The study highlights the importance of data literacy in higher education and emphasizes the need to develop suitable instruments for evaluating teaching and learning events on data literacy. The study makes it clear that there are currently no testing and measurement instruments that adequately assess the quality of data literacy courses. Most of the available evaluation instruments focus primarily on assessing general statistical, visual, or information-related skills and do not take into account all the skills involved in the data life cycle [

8].

The study by Oguguo et al. [

5] provides insights into the data literacy skills of students at five Nigerian universities. The results of the survey, in which 2,550 students from various disciplines and degree programs participated, show that the participants rate their data collection skills as comparatively high. In other areas, such as data analysis, data interpretation, and visualization, they rated their own skills as average. The study shows that although students consider themselves capable of searching for data, they have difficulty effectively analyzing and interpreting this data. The authors of the study suggest that the limited curricular integration of data literacy in degree programs could be a possible reason for this discrepancy. Another reason for the moderate ratings of students’ data literacy skills could be the limited expertise of teachers in incorporating all aspects of data literacy into their courses. In addition, according to the authors of the study, the rapid development of technology and applications for handling data may play a role, requiring continuous adjustments in data literacy education.

Further insightful information is provided by the evaluation of an interdisciplinary data project conducted by Bandtel et al. [

4]. A pre- and post-questionnaire was used to assess the participants’ personality traits and digital skills. With regard to digital skills, six sub-dimensions were identified: “Digital information and research,” “Digital communication and cooperation,” “Digital analysis and reflection,” “IT skills,” “digital identity and career planning,” and “digital science” [

15]. The results show that in the pre-survey, students rated their digital skills as rather low, especially in the use and creation of digital media in an academic context. However, after completing the data project, they rated their skills in digital research and information retrieval, as well as in literature management and knowledge management, higher than before. The experiences in the data project also led to students feeling more confident in the areas of “digital communication and collaboration” and “handling sources and methods for scientific purposes” [

4, p.407].

The studies presented clearly show the need for suitable teaching and learning scenarios for the development of data literacy [

8,

9]. Although students are able to collect data, they seem to have difficulties with analysis and interpretation [

5,

16]. The integration of practice-oriented projects and interdisciplinary approaches [

4] can add value to the development of data literacy by creating an environment for the targeted and action-oriented development of data literacy.

3. The Basic Course in Data Literacy and Its Modules

Based on the goal of offering data literacy in an interdisciplinary manner at TH Köln, the DaLI basic course was developed as a modular, interdisciplinary course offering for all students at TH Köln. This course enables students to view tasks with real data from an interdisciplinary perspective and to learn about and apply questions and methods from other disciplines in the respective areas of competence [

17]. In order to adequately convey the areas of expertise addressed, expertise from different disciplines should be included in the design [

9]. In this regard, ten teachers from different faculties at the university were involved in developing the content of the DaLI basic course, who also took on responsibility for the content of various data competence areas in accordance with their field of expertise.

The DaLI basic course is designed to last one semester, i.e., approximately 14 semester weeks, and consists of seven modules in which the topics of the various areas of competence are covered. During the course, students engage with the content in a self-directed manner and work together on a data project with open data

1. The structure of the course follows the flipped classroom model [

18] (see

Figure 2), in which participants work through a module in the corresponding self-study program of the DaLI basic course on the KI-Campus

2 between classroom sessions. The first module, “Establishing Data Culture,” forms the basis of the entire model and also provides the first interface with the library, because good scientific practice, as taught in the library, also forms the basis for ethical, transparent, and high-quality research. This also includes the structured handling of research data and the creation of data management plans, which are also essential foundations of scientific work. In the second module, “Providing Data,” students at the AI Campus, for example, explore the concepts of secondary and primary research, learn what hypotheses are and how to form them, learn about the process of an empirical study, and what to look out for when collecting data. Based on the content developed there, they then work on a project task in an online exchange with other students from different faculties. Here, too, there are interfaces with library work, such as the introduction of re3data (

www.re3data.org) as a global, web-based directory for research data repositories that helps researchers and students from all disciplines find repositories for research data in libraries.

The respective project tasks are interrelated and build upon one another, guiding learners through a complete data project lifecycle — from data acquisition and cleaning to analysis and the final documentation of results. This approach ensures the theoretical content is applied and implemented in practice right from the start. In the second module, for example, they formulate research questions and hypotheses based on open meteorological data, define the necessary variables, and actively download data from an open weather data pool for further processing in the project. Weather data was selected because, as a generic data type, it is similarly understandable to all degree programs. Students evaluate the quality and completeness of the available data in relation to their research question and prepare it for further processing.

After completing the task, students post their results and work steps on THspaces

3, the social learning environment of TH Köln. The task also involves reading, evaluating, and constructively commenting on two posts by other students in a peer learning format. Every two weeks, the topic currently being worked on is discussed and supplemented in terms of content in online meetings. These include group sessions in which students work together on the open data project and exchange their results. The DaLI basic course is offered each winter semester and has already been held four times.

While modules 3-6 deal extensively with the processing, analysis, and visualization of data from the student project, the seventh module, “Publish Data,” once again covers key areas of library work, as the research data cycle is closed in the project. Library staff explain the further process steps from processing and storage to publication, archiving, or even deletion of research data. At the same time, the principle of FAIR data [

19] handling is revisited and reiterated, i.e., research data should be findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable.

4. Research Design and Methodology

In order to evaluate the learning progress of the students, we examined how the methods and content of the basic course build on and expand the existing skills of the students. How do students rate their data literacy at the beginning and end of the course, and in which areas of competence are there positive developments and where are there still deficits?

The following section focuses primarily on the results of the evaluation in the areas of competence in which libraries take on and impart a larger part of the content: "Establishing data culture", "Providing data" and "Publishing data". This evaluation summarises the research conducted between the winter semester 2022/23 and the winter semester 2024/25. The population consisted of all participants in the basic course during these three years. The data was collected using two online questionnaires that were made available to students at the beginning and end of the course. A total of 130 students completed the pre-questionnaire, while 42 students answered the post-questionnaire.

A separate pre- and post-questionnaire was developed for the evaluation [

20], which was based on the TH Köln’s competence framework for data literacy (cf. Chapter

2.1). In line with the learning outcomes [

21] of the DaLI basic course, the focus was mainly on competencies in the lower levels of Bloom’s taxonomy, which relate to knowledge, understanding and basic application skills [

22].

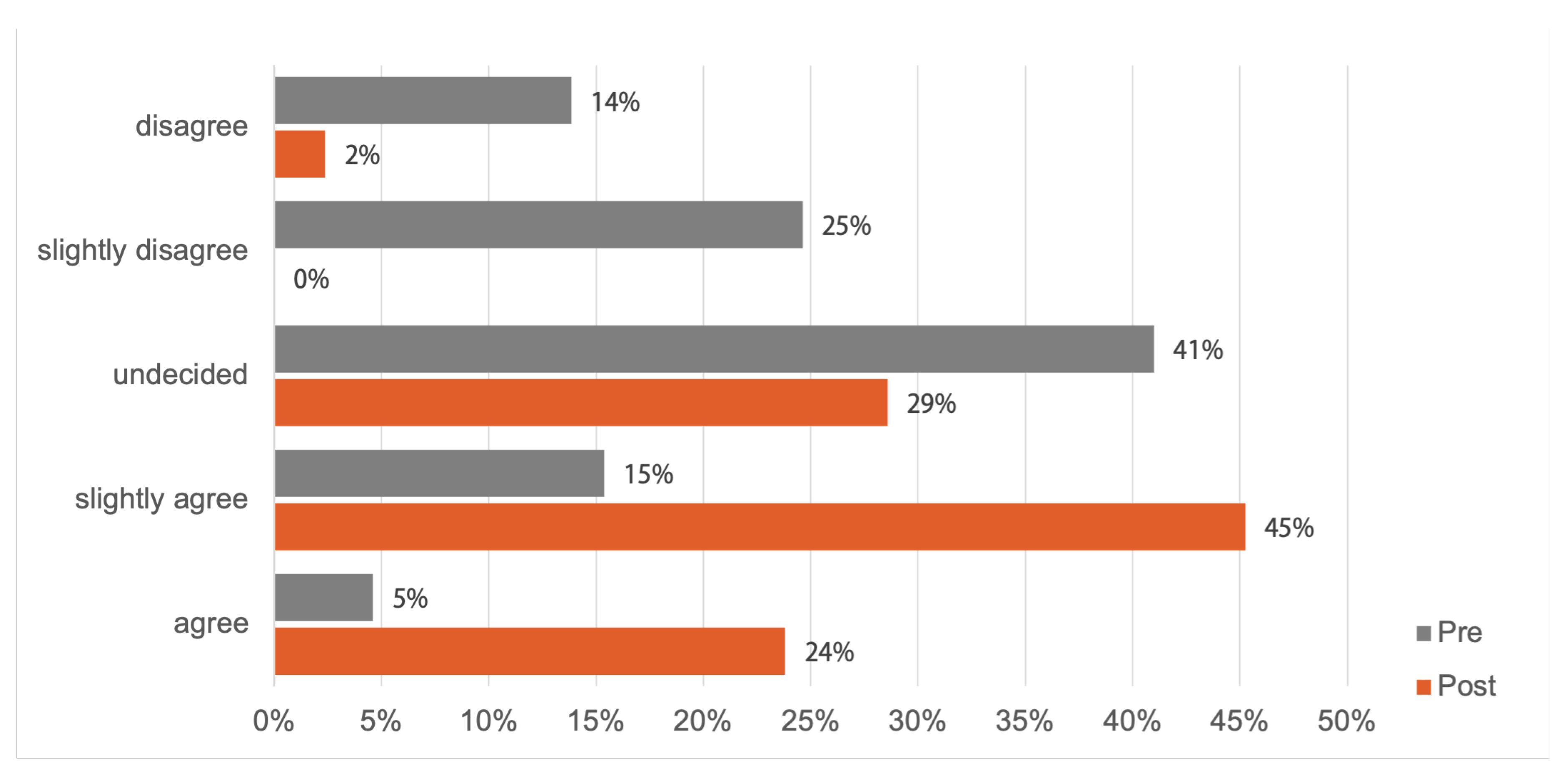

5. Results - Assessment of Own Data Literacy

The summary evaluation of the last three years shows that students feel significantly more confident in handling data after the course than at the beginning of the course (p = 0.00) (

Figure 3).

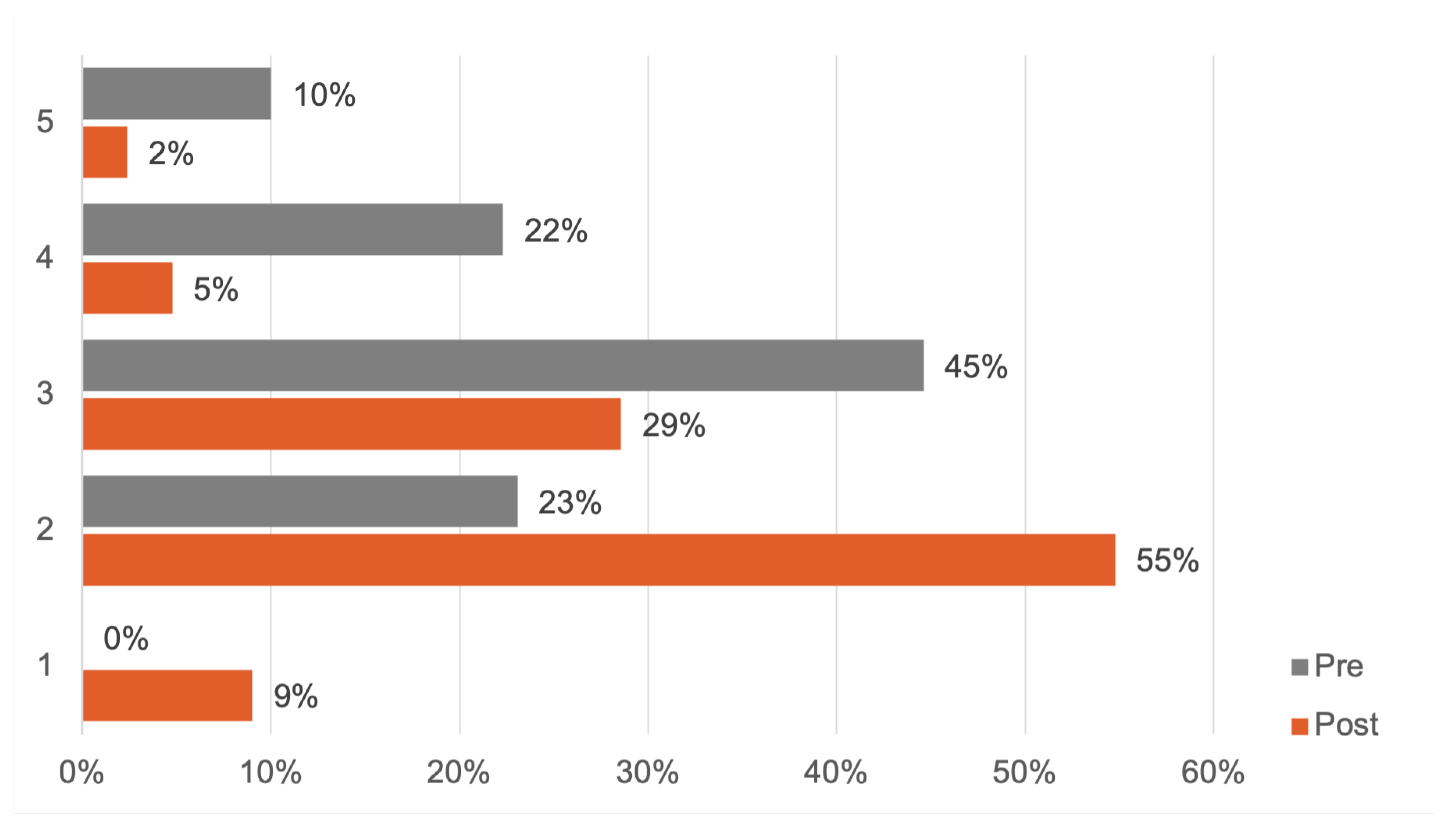

On a scale of one to five, they also rated their general data literacy significantly higher after the course (p = 0.00) (

Figure 4).

The following assessments of personal data competence were made on a scale of -2 "not applicable", -1 "rather not applicable", 0 "partly applicable, partly not applicable", 1 "rather applicable" and +2 "applicable".

In the competence area "

Establish Data Culture", the students stated at the beginning of the basic course that they knew the difference between data, information and knowledge (M

4=0.45) and that they handled personal data with care (M=0.78). In their opinion, they are not good at assessing gross violations of data protection (M=0.27), have difficulty recognising whether content on the internet is protected by copyright (M=0.15) and are not sufficiently familiar with guidelines, rules and criteria relevant to data protection (M= -0.08).

In the area of "Provide Data", the students reported in the pre-evaluation that they found it difficult to formulate hypotheses from a data set within the framework of a given research question (M = –0.31). In addition, they stated that they were not familiar with quality criteria for research data (M = –0.13) and therefore rarely applied criteria to critically evaluate the quality of a data source (M = –0.24). They also found it difficult to clean existing data (M = –0.63).

The area of "publish data" received the lowest rating, i.e., this was where the least competence was found. The students stated that they tended not to be familiar with the possibilities of sustainable data management (M = –0.53). They also stated that they were unable to name the advantages and disadvantages of open access publications and open data (M = –0.31) or the opportunities and challenges of long-term archiving and reuse of data (M = –0.62). They were also largely unfamiliar with methods for citing scientific data and publications in their own discipline (M = 0.01). The need for library cooperation is by far the greatest in this area.

After completing the basic course, the students rated their skills significantly higher in most areas than before the course began. The average values ranged between M = 1.10 and M = 1.34 (

Figure 5). There was a particularly marked improvement in skills in the areas of "managing data" (pre: M = –0.29; post: M = 1.10) and "publishing data" (pre: M = –0.41; post: M = 1.21). Students also rated their knowledge of data protection (pre: M = –0.08; post: M = 1.22) and copyright (pre: M = 0.15; post: M = 1.26) was rated significantly higher by the students, who stated that they were better able to recognise gross violations of data protection (pre: M = 0.27; post: M = 1.38). The students reported being able to clean data better after the course (pre: M = –0.63; post: M = 1.04). In addition, they are now familiar with criteria for evaluating research data (pre: M = –0.13; post: M = 1.49) and, according to their own assessment, also apply these criteria (pre: M = –0.24; post: M = 1.24). After completing the course, they are also aware of opportunities for sustainable data management (pre: M = –0.53; Post: M = 1.09) the advantages of open access and open data (Pre: M = –0,31; Post: M = 1,48), the opportunities and challenges of archiving and reuse (Pre: M = –0.62; Post: M = 1.30) and methods of scientific citation (Pre: M = 0.01; Post: M = 1.21).

6. Discussion

The pre- and post-evaluation of the basic course show significant improvements among students in the various areas of competence. After the course, students feel more confident in handling data and rate their data literacy significantly higher. The pre-evaluation shows that at the beginning of the course, students rate their receptive data handling positively, but rate themselves primarily negatively in terms of productive, analytical and scientific data handling. Similar results are also shown in the studies by Oguguo et al. and Bandtel et al. [

4,

5].

The students’ self-assessment after completing the course shows significant improvements, primarily in the areas of "managing data" and "publishing data". The increase was highest in both areas compared to the pre-evaluation (

Figure 5). Competencies in the area of "publishing data" are considered particularly important for supporting transparency and dialogue in science and research [

23,

24]. A special feature of research data comes into play in the competence area of "publishing data". In the spirit of open science, this data should be publicly accessible (open access) and available for reuse and publication. This is at least one of the central areas for active input and the teaching of skills by academic libraries.

The competence area "evaluating data" shows a lower increase in competence, which suggests that this module needs to be revised. In particular, the selection and application of quantitative data analysis methods and their implementation in analysis software seems to be a challenge for some students, both before and after the course. The results are also consistent with other studies. Students describe data analysis as challenging [

25] and tend to rate their own skills as low [

5].

Due to the limited sample size, the results are not representative. Nevertheless, they offer valuable insights into practice-oriented digital learning scenarios for promoting basic data literacy skills. Further research with larger samples is needed to validate the results and draw more comprehensive conclusions.

7. Implications for Cooperation with Libraries and Outlook

The results suggest that attending and completing the basic course increases students’ data literacy and promotes their understanding and appreciation of data literacy. Nevertheless, there is room for improvement in terms of adapting the learning materials and creating greater social interaction between students. At the same time, the results also show that significant learning progress has been made in fields where academic libraries have proven expertise. This presents an opportunity to involve libraries even more closely as strategic partners in embedding data literacy in the curriculum. Future collaborations should aim to systematically integrate library services with subject-specific teaching formats in order to cover both technical and ethical-legal aspects of data handling. A promising approach is the expansion of interdisciplinary teaching and learning settings in which librarians work together with subject lecturers to support practice-oriented projects – for example, in the context of open data initiatives or research-related courses. In this context, libraries can act not only as knowledge mediators, but also as infrastructure and service centres that support the entire research data cycle [

26].

In the long term, collaborations should also focus on building sustainable networks between university libraries, data centres, research groups and external partners. International examples show that such networks increase the visibility of data literacy offerings, create synergies in the development of training materials and promote knowledge transfer between institutions [

27,

28].

In the context of advancing digitalisation and the growing importance of data-driven research, the role of academic libraries as competent partners in teaching data literacy will continue to gain relevance. Future developments – for example in the fields of artificial intelligence, automated data analysis or research data infrastructures – will require continuous adaptation of training content. Libraries that get involved in these fields of innovation at an early stage can consolidate their position as indispensable partners in the higher education context and actively contribute to the training of tomorrow’s "data professionals" [

29].

Funding

After initial funding from the Data Literacy Education.NRW programme run by the Stifterverband Germany (2020) and the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung Germany (2021), DaLI has been continued and continuously expanded at the TH Cologne since 2023 using internal quality improvement funds.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sühl-Strohmenger, W.; Reckling-Freitag, K. Teaching Library. Bibliotheksportal.de, 2023. accessed 2025-09-09.

- Franke, F.; Krähling-Pilarek, M., 3.6 Aufgaben und Organisation der Teaching Library. In Praxishandbuch Bibliotheksmanagement; De Gruyter, 2024; pp. 189–210. [CrossRef]

- Informationskompetenz, F. IK-Statistik. informationskompetenz.de, 2025. accessed 2025-09-09.

- Bandtel, M.; Kauz, L.; Weißker, N., Data Literacy Education für Studierende aller Fächer. Kompetenzziele, curriculare Integration und didaktische Ausgestaltung interdisziplinärer Lehr-Lern-Angebote. In Digitalisierung in Studium und Lehre gemeinsam gestalten; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden, 2021; pp. 395–412. [CrossRef]

- Oguguo, B.C.E.; Nannim, F.A.; Okeke, A.O.; Ezechukwu, R.I.; Christopher, G.A.; Ugorji, C.O. Assessment of Students’ Data Literacy Skills in Southern Nigerian Universities. Universal Journal of Educational Research 2020, 8, 2717–2726. [CrossRef]

- Ridsdale, C.; Rothwell, J.; Smit, M.; Bliemel, M.; Irvine, D.; Kelley, D.; Matwin, S.; Wuetherick, B.; Ali-Hassan, H. Strategies and Best Practices for Data Literacy Education Knowledge Synthesis Report, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Dr. Jens Heidrich.; Bauer, P.; Krupka, D. FUTURE SKILLS: ANSÄTZE ZUR VERMITTLUNG VON DATA LITERACY IN DER HOCHSCHULBILDUNG 2018. [CrossRef]

- Schüller, K.; Busch, P. Data Literacy: Ein Systematic Review. Zenodo 2019. [CrossRef]

- Schüller, K.; Paulina Busch ·.; Hindinger, C. Future Skills: Ein Framework für Data Literacy. Zenodo 2019. [CrossRef]

- Schüller, K.; Koch, H.; Rampelt, F. Data-Literacy-Charta. Stifterverband, 2021. https://www.stifterverband.org/sites/default/ files/data-literacy-charter.pdf, accessed 2025-09-10.

- Schield, M. Information Literacy, Statistical Literacy and Data Literacy. IASSIST Quarterly 2004, 28, 6–11. [CrossRef]

- Prado, J.C.; Marzal, M.Á. Incorporating Data Literacy into Information Literacy Programs: Core Competencies and Contents. Libri 2013, 63. [CrossRef]

- Fühles-Ubach, S.; Echtenbruck, M.; Heidkamp, P. Teaching data literacy - what is the existing curriculum, what must be added, and what will be the role of libraries?. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference onPerformance Measurement in Libraries, nov 2021, pp. 255–264.

- Demiröz, V.; Lämmlein, B. Data Literacy im Hochschulkontext: Working Paper Nr. 33 des Fachbereichs 3 Wirtschaft und Recht, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Eichhorn, M.; Tillmann, A. Digitale Kompetenzen von Hochschullehrenden messen. DeLFI 2018–Die 16. E-Learning Fachtagung Informatik der Gesellschaft für Informatik e. V. 2018, pp. 69–80.

- Carlson, J.; Johnston, L.; Westra, B.; Nichols, M. Developing an Approach for Data Management Education: A Report from the Data Information Literacy Project. International Journal of Digital Curation 2013, 8, 204–217. [CrossRef]

- Lerch, S. Interdisziplinäre Kompetenzbildung: fächerübergreifendes Denken und Handeln in der Lehre fördern, begleiten und feststellen; Hochschulrektorenkonferenz, 2019.

- Ağırman, N.; Ercoşkun, M.H. History of the Flipped Classroom Model and Uses of the Flipped Classroom Concept. Uluslararası Eğitim Programları ve Öğretim Çalışmaları Dergisi 2022, 12, 71–88. [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, M.D.; Dumontier, M.; Aalbersberg, I.J.; Appleton, G.; Axton, M.; Baak, A.; Blomberg, N.; Boiten, J.W.; da Silva Santos, L.B.; Bourne, P.E.; et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data 2016, 3. [CrossRef]

- Kaliva, E.; Fühles-Ubach, S.; Piecha, J. Fragebogen zur Selbsteinschätzung von Data Literacy Basiskompetenzen, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wunderlich, A.; Szczyrba, B. Lerning-Outcomes ‚lupenrein‘formulieren. https://www.th-koeln.de/mam/downloads/deutsch/hochschule/profil/lehre/steckbrief_learning_outcomes.pdf, 2016.

- Bloom, B.S.; Engelhart, M.D.; Furst, E.J.; Hill, W.H.; Krathwohl, D.R.; et al. Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook 1: Cognitive domain; Longman New York, 1956.

- Piwowar, H.A.; Vision, T.J. Data reuse and the open data citation advantage. PeerJ 2013, 1, e175. [CrossRef]

- Borgman, C.L. Big Data, Little Data, No Data: Scholarship in the Networked World; The MIT Press, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Ghodoosi, B.; Torrisi-Steele, G.; West, T.; Heidari, M. Perceptions of data literacy and data literacy education. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science 2024, 57, 822–832. [CrossRef]

- Fühles-Ubach, S.; Echtenbruck, M.; Heidkamp, P. Data Literacy als neue Schlüsselkompetenz - Welche Rolle haben Bibliotheken? B.I.T. online. Bibliothek. Information. Technologie. 2021, pp. 499–510.

- Lavoie, B.; Bryant, R.; Rinehart, A. Building Research Data Management Capacity: Case Studies In Strategic Library Collaboration, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Reichert, S. The role of universities in regional innovation ecosystems. EUA study, European University Association, Brussels, Belgium 2019.

- Clemons, A.; Gross, B.; Young, B.; Lyles, K. Awareness, application, augmentation: An approach to data literacy education in academic libraries. Public Services Quarterly 2024, 21, 9–29. [CrossRef]

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

KI-Campus is a German online platform funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), serving as a primary hub for AI and data literacy courses. KI-Campus.org

|

| 3 |

THspaces is a student-centered platform provided by TH Köln for digital spaces in teaching, research, and projects. It supports communication and collaboration, the creation of digital portfolios, and is used for community building, flipped classroom formats, and peer learning. For more information, see: https://lehrpfade.th-koeln.de/thspaces/. |

| 4 |

M = median |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).