1. Introduction

Standard logical systems are built upon implication operators that encode either material entailment or causal dependence. In many domains, however, such operators are ill-suited to capture the relations at stake. For instance, scientific and clinical practice routinely confront situations where two descriptions co-vary without admitting reduction to cause and effect. For example, neuroimaging reveals stable correspondences between patterns of cortical activation and reported perceptual states, but the inference that the neural produces the experiential is philosophically and methodologically contentious. Similarly, in clinical contexts, patients often ascribe causal links between symptoms and imagined physiological processes, when in fact what is observed is a lawful co-occurrence without direct production.

What is needed is a formal framework that preserves lawful co-variation while avoiding premature causal commitments. We propose Coordination Logic, a system whose central connective encodes coordination rather than causation. The notion has historical antecedents. Richard Avenarius articulated a “principle of coordination”: brain and thought should be regarded as two lawful descriptions of a single experiential field rather than as cause and effect. Our aim, however, is not historical exegesis but the development of a rigorous formalism that generalizes this insight across domains.

Coordination Logic introduces a new conditional operator, ⇒c, read as conditional coordination. Unlike material implication, this operator is non-vacuous and symmetric, defined only when both relata are instantiated and coordinated. We show how the semantics of this connective can be grounded in a three-valued framework and how a corresponding proof theory can be developed. The system presents a non-causal logic of dual description, opening new possibilities for the formal treatment of dependencies in philosophy of mind, philosophy of science, psychology, psychiatry and clinical reasoning.

2. Preliminaries

The dominant conditional in classical logic, material implication (→), is truth-functional: A → B is false only if A is true and B is false; in all other cases it is true. While elegant, this connective is often criticized for being too weak to capture intuitions about dependency. In particular, the principle of vacuous truth allows (A → B) to hold whenever A is false, independently of any relation between A and B. For many applications such as scientific reasoning this feature is unsatisfactory. One may wish to represent lawful co-variation without granting truth to conditionals in cases where the antecedent is not instantiated.

Several non-classical systems attempt to strengthen the conditional. Relevance logics require a substantive connection between antecedent and consequent. Modal logics evaluate conditionals across possible worlds. Dependence logic introduces primitives that capture functional dependence among variables. Each approach targets inadequacies of material implication, but none directly models coordination as distinct from causation or entailment.

The relation of interest is one in which two descriptions stand in lawful correspondence without implying that one produces the other. For instance, neural activity in a specific cortical area and the corresponding reported perceptual state may vary together, but it is philosophically contentious to construe this as a causal chain. The challenge is to formalize this form of dual-aspect co-variation.The need for this connective has been noted, albeit indirectly, in philosophical contexts. Avenarius (1890/1921) argued that brain and thought are “coordinated” aspects of one experiential field rather than related as cause and effect. While we do not adopt his broader empirio-critical program, the underlying idea motivates our system: to introduce a formal operator that respects lawful co-occurrence while blocking causal or reductive readings.

In the next section, we introduce the syntax of Coordination Logic (CL), a propositional system built upon classical connectives augmented with a primitive operator ⇒c for conditional coordination and a biconditional ↔c. These operators are interpreted in a three-valued semantics that avoids vacuous truth and enforces field-dependence.

3. Syntax

We define the formal language of Coordination Logic (CL) as an extension of propositional logic with additional primitives for coordination.

Alphabet:(i) Propositional Variables. Two disjoint indexed families are assumed: 𝓝 = {N1, N2, …} for neural (or physical) descriptions and 𝓔 = {E1, E2, …} for experiential descriptions. For technical purposes, 𝓝 ∪ 𝓔 is a set of atomic formulas.(ii) Logical Connectives. Unary: ¬ (negation). Binary: ∧ (conjunction), ∨ (disjunction). Coordination Conditional: ⇒c. Coordination Biconditional: ↔c.(iii) Auxiliary Predicate. C(p,q) is a primitive coordination predicate defined only for atomic pairs p ∈ 𝓝, q ∈ 𝓔 (or vice versa). This predicate is not a formula of CL but enters into the semantics.

Well-formed formulas (wffs):(1) If p ∈ 𝓝 ∪ 𝓔, then p ∈ 𝓕.(2) If φ ∈ 𝓕, then ¬φ ∈ 𝓕.(3) If φ, ψ ∈ 𝓕, then (φ ∧ ψ), (φ ∨ ψ) ∈ 𝓕.(4) If φ, ψ ∈ 𝓕, then (φ ⇒c ψ) ∈ 𝓕.(5) If φ, ψ ∈ 𝓕, then (φ ↔c ψ) ∈ 𝓕.

Intended reading of new connectives:φ ⇒c ψ (conditional coordination): whenever both φ and ψ obtain, they do so as coordinated aspects of the same field-event. Unlike material implication, this connective is undefined (or evaluates to the null value) if φ is false or not instantiated.φ ↔c ψ (biconditional coordination): defined as (φ ⇒c ψ) ∧ (ψ ⇒c φ). It expresses full dual description: both terms obtain and are coordinated.

Syntactic categories:

Atomic Descriptions: elements of 𝓝 ∪ 𝓔.

Composite Formulas: formulas built via ¬, ∧, ∨, ⇒c, ↔c. The distinction matters because the semantics of coordination relies on atomic-level pairings via C.

Remarks:

CL is propositional at base; extensions to first-order syntax are possible. The symbols ⇒c and ↔c are primitive; treating ↔c as defined is convenient but both are admitted in the proof theory. Coordination is not a classical truth-functional connective; semantics (

Section 4) evaluates it relative to a coordination field and the predicate C.

4. Semantics

We adopt a three-valued semantics: T (true), F (false) and ∅ (undefined). A coordination model is a pair M = ⟨F, v⟩, with F a coordination field and v a valuation. For atoms, v(p) ∈ {T, F, ∅}.

Coordination predicate:

C(p,q) = T if p and q are instantiated in F as dual descriptions of the same field-event; C(p,q) = F if both are instantiated but not coordinated; undefined otherwise. Symmetry holds, i.e., C(p,q) = C(q,p).

Semantic clauses:

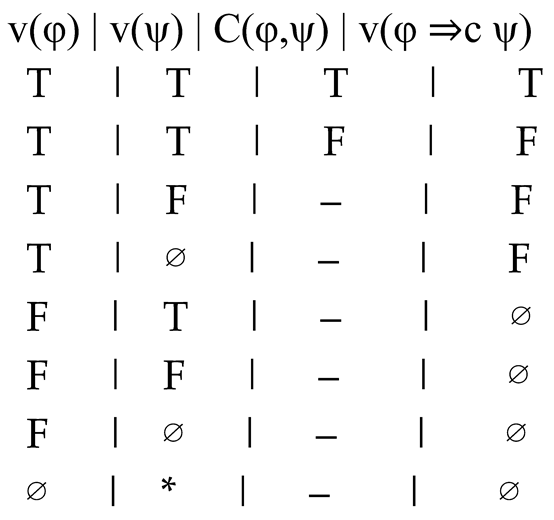

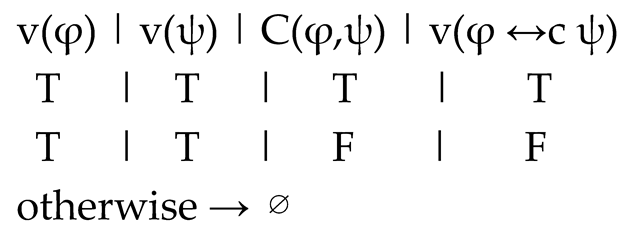

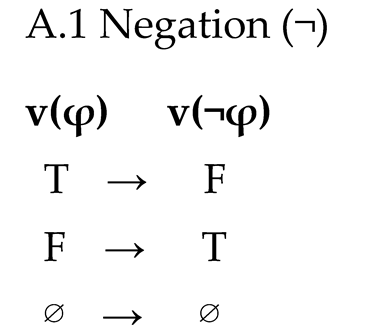

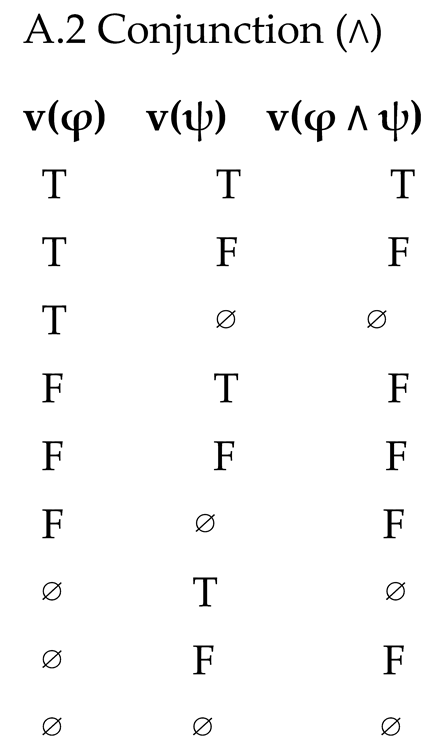

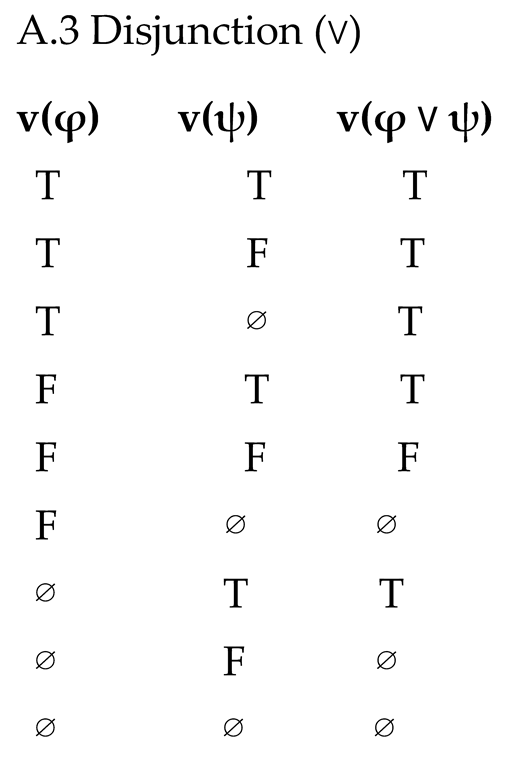

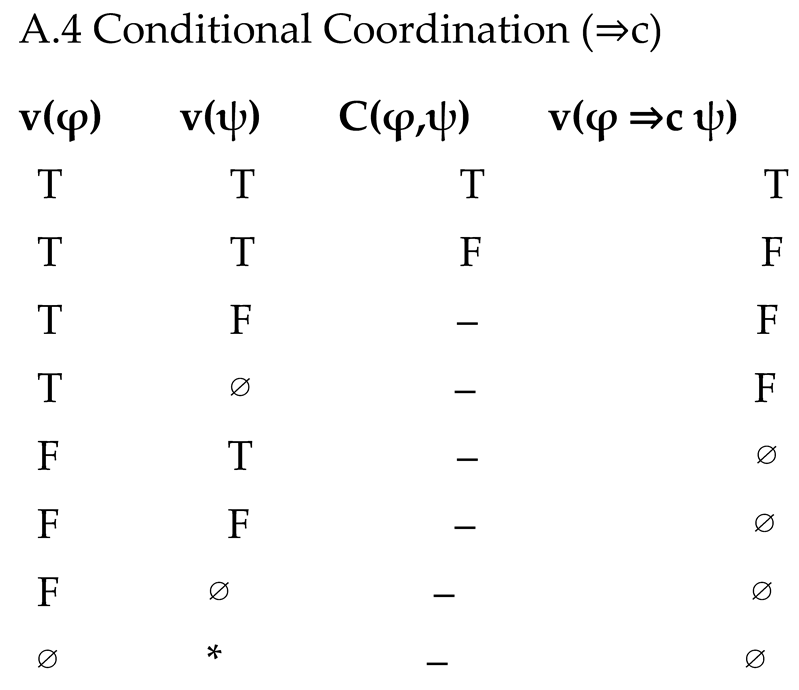

• v(¬φ): T if v(φ)=F; F if v(φ)=T; ∅ if v(φ)=∅.• v(φ ∧ ψ): follows Strong Kleene conjunction. T if both T; F if at least one F; ∅ otherwise.• v(φ ∨ ψ): follows Strong Kleene disjunction. T if at least one T; F if both F; ∅ otherwise.• v(φ ⇒c ψ): T if v(φ)=T, v(ψ)=T and C(φ,ψ)=T; F if v(φ)=T, v(ψ)=T and C=F; F if v(φ)=T, v(ψ)≠T; ∅ if v(φ)≠T.• v(φ ↔c ψ): v(φ ⇒c ψ) ∧ v(ψ ⇒c φ).

Truth tables for ⇒c:

Truth tables for ↔c:

Properties of the semantics:

• Symmetry: If C(φ,ψ)=T, then v(φ ⇒c ψ)=v(ψ ⇒c φ)=T.• Non-vacuity: If v(φ)≠T, then v(φ ⇒c ψ)=∅.• Non-reduction: ⇒c is not reducible to material implication or functional dependence.• Field-dependence: Evaluation presupposes a coordination field F; conditionals cannot be interpreted outside a field.

Remarks:

This semantics diverges from classical truth-functionality by explicitly depending on the primitive predicate C. It also blocks vacuous truth: a conditional coordination cannot be true merely because its antecedent is false. The ∅ value plays a crucial role in preventing triviality while allowing coordination to be well-defined only when the relevant relata are instantiated.

The biconditional ↔c inherits its behavior from ⇒c, ensuring that dual-aspect coordination is captured only if both directions of coordination hold. This guarantees that coordination is symmetric but not automatically reflexive or transitive; these properties depend on the specification of C in the field.

5. Proof Theory

We present a sequent calculus for Coordination Logic (CL). A sequent is of the form Γ ⊢ Δ, where Γ and Δ are finite multisets of formulas. The intended reading is: whenever all formulas in Γ are designated, at least one formula in Δ is designated.

5.1. Structural Rules

• Identity: φ ⊢ φ.• Weakening (Left/Right): from Γ ⊢ Δ infer φ, Γ ⊢ Δ; from Γ ⊢ Δ infer Γ ⊢ Δ, φ.• Exchange: Γ, φ, ψ, Σ ⊢ Δ iff Γ, ψ, φ, Σ ⊢ Δ.• Contraction (Left/Right): from Γ, φ, φ ⊢ Δ infer Γ, φ ⊢ Δ; from Γ ⊢ Δ, φ, φ infer Γ ⊢ Δ, φ.• Cut: from Γ ⊢ Δ, φ and φ, Σ ⊢ Π infer Γ, Σ ⊢ Δ, Π.

5.2. Logical Rules for Negation, Conjunction and Disjunction

Negation (¬): From Γ ⊢ Δ, φ infer ¬φ, Γ ⊢ Δ. From φ, Γ ⊢ Δ infer Γ ⊢ Δ, ¬φ.

Conjunction (∧): From Γ, φ, ψ ⊢ Δ infer Γ, (φ ∧ ψ) ⊢ Δ. From Γ ⊢ Δ, φ and Γ ⊢ Δ, ψ infer Γ ⊢ Δ, (φ ∧ ψ).

Disjunction (∨): From Γ, φ ⊢ Δ and Γ, ψ ⊢ Δ infer Γ, (φ ∨ ψ) ⊢ Δ. From Γ ⊢ Δ, φ, ψ infer Γ ⊢ Δ, (φ ∨ ψ).

5.3. Rules for Conditional Coordination (⇒c)

Right Rule: From Γ ⊢ Δ, φ and Γ ⊢ Δ, ψ and side condition C(φ,ψ), infer Γ ⊢ Δ, (φ ⇒c ψ).

Left Rule:

From Γ, φ, ψ ⊢ Δ and side condition C(φ,ψ), infer Γ, (φ ⇒c ψ) ⊢ Δ.

5.4. Rules for Biconditional Coordination (↔c)

Right Rule: From Γ ⊢ Δ, (φ ⇒c ψ) and Γ ⊢ Δ, (ψ ⇒c φ) infer Γ ⊢ Δ, (φ ↔c ψ).

Left Rule: From Γ, (φ ⇒c ψ), (ψ ⇒c φ) ⊢ Δ infer Γ, (φ ↔c ψ) ⊢ Δ.

5.5. Failures of Classical Inference Rules

Modus Ponens fails: from φ and (φ ⇒c ψ) one cannot derive ψ. This is because ⇒c requires explicit coordination C(φ,ψ) and without it the inference does not hold.

Explosion fails: from φ and ¬φ one cannot derive an arbitrary ψ. Coordination Logic blocks trivialization in the presence of contradiction, since ∅ prevents global collapse.

5.6. Derived Properties

• Coordination Introduction: from φ, ψ and C(φ,ψ), one can always derive φ ⇒c ψ.• Coordination Symmetry: φ ⇒c ψ iff ψ ⇒c φ whenever C(φ,ψ)=T.• Partiality: if v(φ)≠T, then sequents involving φ ⇒c ψ evaluate to ∅, blocking overextension.

5.7. Soundness and Completeness

Soundness: If Γ ⊢ Δ is derivable, then in every model where all formulas in Γ are designated, at least one formula in Δ is designated. Proof by induction on derivations.

Completeness: If Γ ⊢ Δ is valid in all models, then it is derivable in the sequent calculus. A canonical model construction is extended from Strong Kleene semantics with coordination constraints. Every unprovable sequent admits a countermodel, demonstrating completeness.

Remarks: The proof theory of CL shows that ⇒c is not an entailment operator but a coordination operator. The calculus makes explicit the field-dependence of coordination and ensures that pathological inferences (e.g., Modus Ponens, Explosion) do not hold. This positions CL among the family of non-classical logics with weakened inference rules, but with a distinctive grounding in coordination rather than relevance or dependence.

6. Applications

Coordination Logic (CL) has applications across multiple domains where lawful co-variation is observed, but causal or reductive language is either unwarranted or misleading. Here we illustrate its role in four distinct areas: philosophy of mind, neuroscience and clinical reasoning, psychology and psychiatry and philosophy of science.

6.1. Philosophy of Mind

In philosophy of mind, discussions of neural correlates of consciousness (NCCs) typically use causal idioms: ‘activity in area V5 generates motion experience’ or ‘prefrontal integration produces access consciousness.’ These formulations can exceed what empirical data establishes, since sometimes the data show lawful co-variation between neural states and experiential reports rather than causal production. CL provides a more accurate framework: if neural description N_m and experiential description E_m are instantiated in coordination, then N_m ⇒c E_m. This expresses lawful coordination without committing to causal reduction.

6.2. Neuroscience and Clinical Reasoning

In neuroscience and medicine, causal terminology is pervasive: lesions are said to ‘cause’ deficits or drugs are said to ‘produce’ symptoms. Yet at the observational level, what is established is sometimes just a consistent co-occurrence. For example, suppression of thalamocortical dynamics is lawfully coordinated with the absence of conscious awareness. By recasting these statements in CL, one can write: Thalamocortical-suppression ⇒c Unawareness. This avoids unwarranted causal commitments and helps maintain clarity between what is empirically observed and what is inferred. In clinical reasoning, this accuracy prevents overextension of causal models and allows a disciplined way to speak of brain-symptom relationships.

6.3. Psychology and Psychiatry

Psychological and psychiatric conditions often involve pathological attribution of causality. Patients with anxiety disorders, obsessive–compulsive disorder or schizophrenia may assert that ‘because I thought X, event Y occurred’ or that two unrelated events are linked by causal necessity. From the perspective of CL, these beliefs involve a confusion between coordination and production. The framework distinguishes lawful coordination (A ⇒c B, grounded in C(A,B)=T) from spurious production claims (A → B without grounding). This provides clinicians with a formal tool for explaining why patient inferences are ill-founded without dismissing their lived experience. For instance, in delusional systems, coordination is wrongly extended beyond lawful pairings, generating causal chains that lack grounding in C. By explicitly modeling this, CL can be integrated into cognitive theories of delusion formation and even serve as a conceptual resource in psychoeducation.

6.4. Philosophy of Science

CL also contributes to general philosophy of science. Scientific practice often involves parallel vocabularies that co-vary without reduction. Examples include thermodynamic vs. statistical mechanical descriptions, linguistic vs. neurocognitive analyses and behavioral vs. computational accounts. In each case, coordination rather than causation is the more faithful description. For instance, a thermodynamic law (increase of entropy) and its statistical underpinning are coordinated aspects of the same phenomenon, but one does not produce the other. CL thus formalizes lawful co-variation across descriptive frameworks, avoiding reduction while retaining rigor.

6.5. Summary

Applications of CL span philosophy, empirical science and clinical practice. In each case, the advantage of CL lies in its ability to express lawful co-variation without importing metaphysical assumptions of causation or reduction.

7. Discussion

7.1. Relation to Existing Non-Classical Logics

Coordination Logic (CL) occupies a distinctive position in the family of non-classical logics. It shares some features with relevance logics, in rejecting vacuous implications and requiring substantive conditions for a conditional to hold. It also resembles dependence logics in introducing a primitive relational constraint on formulas. However, CL diverges from both traditions in crucial ways. Relevance logic remains committed to entailment: the conditional is still read as a relation of inferential consequence. Dependence logics capture functional dependence among variables but not the notion of dual-aspect coordination across descriptive vocabularies. CL alone treats coordination as a primitive logical relation: symmetric, non-reductive and defined only in terms of lawful co-variation.

7.2. Advantages

The main advantages of CL can be grouped under three headings:

• Epistemological discipline: By replacing causal terms with coordination, CL prevents over-interpretation of correlational data, especially in neuroscience and medicine.• Ontological neutrality: CL provides a rigorous framework without committing to reductive materialism or idealism.• Interdisciplinary utility: CL provides a unifying language for phenomena in philosophy of mind, psychiatry and philosophy of science, where multiple vocabularies describe the same underlying structures.

7.3. Limitations

By design, it weakens inference, which constrains its applicability in domains that demand strong deductive closure or the derivation of predictive consequences from minimal premises. The system’s reliance on an exogenous coordination predicate C(p,q) also makes it dependent on empirical or contextual specification, raising concerns about how coordinations are to be identified and validated in practice. Moreover, the introduction of a third truth value (∅) complicates the logical landscape: while it blocks vacuity and triviality, it also reduces expressive transparency and may hinder automated reasoning. Another challenge lies in scalability—although the propositional core is well-defined, extending CL to first-order, modal, or probabilistic settings requires careful handling to avoid collapse into existing dependence or relevance frameworks. Finally, the epistemological neutrality of CL, while philosophically attractive, can be a weakness in applied contexts, since it deliberately avoids settling whether coordinations should ultimately be understood as causal, functional, or ontological relations. These limitations highlight both the novelty and the fragility of CL: it gains rigor by carving out a distinctive space, but at the cost of generality and inferential strength.

7.4. Extensions and Future Work

Several natural extensions of CL can be envisaged, each aimed at broadening its expressive power and practical relevance. A modal version would allow coordination to be evaluated across possible worlds, thereby capturing counterfactual dependencies. A first-order extension would introduce quantification over objects, descriptions, and coordination relations, making it applicable to more complex scientific theories. A probabilistic formulation could account for graded or noisy coordinations, as commonly encountered in empirical domains such as neuroscience. Finally, a dynamic version would treat the establishment, disruption, and evolution of coordinations as logical phenomena in their own right, enabling the modelling of processes that unfold over time. Together, these developments would transform CL from a foundational formalism into a versatile tool for analysing multi-level and interdisciplinary phenomena.

7.5. Broader Implications

CL enriches the toolkit of non-classical logics by establishing coordination as a new primitive relation, distinct from entailment, causation or dependence. Its implications are wide-ranging. In philosophy of mind, it clarifies debates about the neural correlates of consciousness. In psychiatry, it provides a framework for understanding pathological causal inferences. In philosophy of science, it articulates how parallel vocabularies can co-vary lawfully without reduction. In logic, it demonstrates how weakening inferential rules can lead to new, disciplined ways of reasoning about descriptional plurality.

CL thus stands as both a theoretical innovation in logic and a practical tool for interdisciplinary research. By making coordination explicit, it clarifies what can and cannot be said in contexts where causal inference is unwarranted, while opening pathways for richer formal exploration of multi-level descriptions.

8. Conclusion

We have introduced Coordination Logic (CL), a formal system that models lawful co-variation between dual vocabularies without presupposing causal dependence. The central innovation of CL is the conditional coordination operator (⇒c), supplemented by the biconditional coordination operator (↔c). These connectives are interpreted via a three-valued semantics that incorporates a primitive coordination predicate C(p,q) and are governed by a sequent calculus proof theory designed to block classical inference rules such as Modus Ponens and Explosion. In doing so, CL preserves the non-reductive, non-causal character of coordination.

The contributions of CL are threefold. First, it provides a rigorous alternative to material implication and other causal idioms, avoiding the vacuity and overextension that plague classical treatments of conditionals. Second, it formalizes the idea of lawful co-variation without production, offering a logical foundation for dual-aspect ontologies, including neutral monism and empirio-critical approaches, while remaining agnostic on specific metaphysical commitments. Third, it demonstrates direct applicability across philosophy of mind, neuroscience, psychiatry and philosophy of science, offering clarity and conceptual discipline in contexts where mistaken causal inferences are common.

In conclusion, CL enriches the landscape of non-classical logics by articulating a new primitive relation of coordination. It stands as both a contribution to formal logic and a practical framework for interdisciplinary research, clarifying how distinct vocabularies can lawfully co-vary without implying causation.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

The Author performed: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, statistical analysis, obtained funding, administrative, technical and material support, study supervision.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the Author.

Consent for publication

The Author transfers all copyright ownership, in the event the work is published. The undersigned author warrants that the article is original, does not infringe on any copyright or other proprietary right of any third part, is not under consideration by another journal and has not been previously published.

Availability of data and materials

All data and materials generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript. The Author had full access to all the data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, the author used ChatGPT 4o to assist with data analysis and manuscript drafting and to improve spelling, grammar and general editing. After using this tool, the author reviewed and edited the content as needed, taking full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Competing interests

The Author does not have any known or potential conflict of interest including any financial, personal or other relationships with other people or organizations within three years of beginning the submitted work that could inappropriately influence or be perceived to influence their work.

Appendix: Truth Tables and Sample Derivations

Appendix A: Truth Tables and Semantic Clauses

We provide the full truth tables for the connectives of Coordination Logic (CL). Truth values are ordered as F < ∅ < T.

Appendix B: Sample Derivations in the Sequent Calculus

We present two short derivations illustrating the distinctive inferential behavior of CL.

- B.1

Valid Coordination Sequent

We show that from coordination of φ and ψ, one may derive φ ⇒c ψ.

1. Assume C(φ,ψ).

2. φ, ψ ⊢ φ (Identity).

3. φ, ψ ⊢ ψ (Identity).

4. From (2) and (3) by ⇒c-Right, infer ⊢ (φ ⇒c ψ).

Thus, lawful coordination yields the conditional coordination formula.

- B.2

Failure of Modus Ponens

Suppose φ and (φ ⇒c ψ) are both true. In classical logic, one would infer ψ. In CL, this inference is blocked.

Example: Let v(φ)=T, v(ψ)=T, but C(φ,ψ)=F. Then v(φ ⇒c ψ)=F. The sequent φ, (φ ⇒c ψ) ⊢ ψ is invalid. Thus, Modus Ponens does not hold for ⇒c.

This illustrates that Modus Ponens does not hold for ⇒c⇒_{c}⇒c. Coordination does not entail production.

- B.3

Non-Explosion

Suppose both φ and ¬φ are present. In classical logic, any ψ could be derived. In CL:

If v(φ)=T, then v(¬φ)=F. The pair φ, ¬φ does not trivialize the valuation. No arbitrary ψ follows. Thus, Explosion fails in CL.

Thus, Explosion fails in CL.

Remarks:

These derivations demonstrate that CL is not an entailment system but a coordination system. By explicitly rejecting Modus Ponens and Explosion, CL ensures that only lawful coordinations established by C(φ,ψ) can generate conditional truths. This protects the logic from collapsing into triviality while capturing the intended non-causal dependencies.

References

- Allen, T. A., Hall, N. T., Schreiber, A. M., & Hallquist, M. N. (2022). Explanatory personality science in the neuroimaging era: The map is not the territory. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 43, 236–241. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A. R., & Belnap, N. D. (1975). Entailment: The Logic of Relevance and Necessity (Vol. 1). Princeton University Press.

- Avenarius, R. (1890/1921). Kritik der reinen Erfahrung. Leipzig: O. R. Reisland. (Reprint: Felix Meiner Verlag, 1921).

- Beall, J. C. (2009). Spandrels of Truth. Oxford University Press.

- Block, N. (1995). On a confusion about a function of consciousness. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 18(2), 227–247.

- Block, N. (2005). Two neural correlates of consciousness. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(2), 46–52.

- Chalmers, D. J. (1996). The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental Theory. Oxford University Press.

- Dunn, J. M. (1976). Relevance logic and entailment. In D. Gabbay & F. Guenthner (Eds.), Handbook of Philosophical Logic (Vol. III, pp. 117–224). Reidel.

- Hill, P. F., Seger, S. E., Yoo, H. B., King, D. R., Wang, D. X., Lega, B. C., & Rugg, M. D. (2021). Distinct neurophysiological correlates of the fMRI BOLD signal in the hippocampus and neocortex. Journal of Neuroscience, 41(29), 6343–6352. [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, J., Zhang, X., Noah, J. A., Dravida, S., Naples, A., Tiede, M., Wolf, J. M., & McPartland, J. C. (2022). Neural correlates of eye contact and social function in autism spectrum disorder. PLoS ONE, 17(11), e0265798. [CrossRef]

- Itahashi, T., Fujino, J., Sato, T., Ohta, H., Nakamura, M., Kato, N., Hashimoto, R. I., Di Martino, A., & Aoki, Y. Y. (2020). Neural correlates of shared sensory symptoms in autism and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Brain Communications, 2(2), fcaa186. [CrossRef]

- Lai, M. C., Voineskos, A. N., & Ameis, S. H. (2024). Task-based functional neural correlates of social cognition across autism and schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Molecular Autism, 15(1), 37. [CrossRef]

- Marek, S., Tervo-Clemmens, B., Nielsen, A. N., Wheelock, M. D., Miller, R. L., Laumann, T. O., … Dosenbach, N. U. F. (2019). Identifying reproducible individual differences in childhood functional brain networks: An ABCD study. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 40, 100706. [CrossRef]

- Marek, S., Tervo-Clemmens, B., Calabro, F. J., Montez, D. F., Kay, B. P., Hatoum, A. S., … Dosenbach, N. U. F. (2022). Reproducible brain-wide association studies require thousands of individuals. Nature, 603(7902), 654–660. [CrossRef]

- Morrel, J., Singapuri, K., Landa, R. J., & Reetzke, R. (2023). Neural correlates and predictors of speech and language development in infants at elevated likelihood for autism: A systematic review. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 17, 1211676.

- Nani, A., Manuello, J., Mancuso, L., Liloia, D., Costa, T., & Cauda, F. (2019). The neural correlates of consciousness and attention: Two sister processes of the brain. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 492.

- Oliver, L. D., Moxon-Emre, I., Hawco, C., Dickie, E. W., Dakli, A., Lyon, R. E., Szatmari, P., Haltigan, J. D., Goldenberg, A., Rashidi, A. G., Tan, V., Secara, M. T., Desarkar, P., Foussias, G., Buchanan, R. W., Malhotra, A. K.

- Priest, G. (2008). An Introduction to Non-Classical Logic (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Restall, G. (1994). On logics without contraction. Studia Logica, 55(2), 301–311.

- Väänänen, J. (2007). Dependence Logic: A New Approach to Independence Friendly Logic. Cambridge University Press.

- Zhang, X., Pan, W. J., & Keilholz, S. D. (2020). The relationship between BOLD and neural activity arises from temporally sparse events. NeuroImage, 207, 116390. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., Zhang, Y., Ma, W., Qi, Z., Wang, Y., & Tao, Q. (2022). Neural correlates of negative emotion processing in subthreshold depression. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 17(7), 655–661. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).