1. Introduction

Water scarcity is among the most critical challenges of our times. Anthropogenic pressures on water resources are on water resources are intensifying due to growing demand from multiple competing water uses – including e.g. irrigation, domestic consumption, energy production, and manufacturing [

1]– combined with unsustainable management practices [

2], and climate change, which is altering the hydrological systems in terms of both water quantity and quality [

3]. Agriculture is the largest water-dependent sector at global scale, accounting for about 70% of the global freshwater withdrawals [

4]. Around 40% of irrigation water is extracted at the expense of freshwater ecosystems [

5], further intensifying the competition between agricultural production and environmental conservation. Given this strong dependency, agriculture is expected to be the sector most severely affected by increasing water scarcity, with profound long term consequences for global food security and rural livelihoods [

6,

7].

Improving water resource management in agriculture is therefore essential to ensure sustainable water use, safeguarding food security while integrating ecological and social sustainability priorities [

8], as well as enhancing the sector’s capacity to adapt to present and future climate change impacts [

9].

In the past and up to the present, efforts to improve water management in agriculture have focused predominantly on improving irrigation performance – particularly in terms of efficiency and productivity – through the adoption of new irrigation technologies and infrastructures [

10,

11]. Irrigation system modernization has been widely promoted as a cornerstone strategy for advancing sustainable water use [

12] and has consequently gained strong policy support. Both European and international policy actively endorses, through public subsides, infrastructural and technological upgrades of irrigation systems [

13,

14], favoring solutions that aim to reduce water consumption while maintaining current levels of agricultural productivity. The modernization of irrigation systems is primarily reshaping irrigation practices by replacing traditional surface irrigation (e.g., flood irrigation) with modern pressurized systems such as drip irrigation. The widespread diffusion of drip irrigation can be attributed to its effectiveness in reducing water losses and improving water productivity, which in turn contributes to higher crop yields [

15]. However, the adoption of drip irrigation is not without drawbacks, as it typically entails higher capital investments and ongoing maintenance requirements [

16] as well as increased energy consumption [

17] all of which translate into higher production costs for famers. Moreover, mounting evidence from several studies shows that the large-scale implementation of drip irrigation does not always relieve pressure on water resources. On the contrary, it may paradoxically trigger to the so-called “rebound effect” [

18,

19,

20] whereby water savings are reinvested to expand irrigated areas, intensify crop production, or are reallocated to competing water users [

13].

Despite a flourishing literature on the efficiency gains achieved through the shifting to drip irrigation, there remains the need to investigate the trade-offs associated with replacing traditional irrigation systems with modern irrigation technologies. In many agroecosystems, irrigation represents a key anthropogenic factor influencing natural processes and the broader hydrological cycle [

21]. Consequently, any alteration in irrigation systems and practices has the potential to impact hydrological balances and alter agroecosystem dynamics at large scale [

22]. For example, traditional irrigation systems, through return flows, contribute to groundwater recharge [

23] and can influence groundwater quality by regulating nutrient leaching [

24]. Moreover, modernization processes extend beyond biophysical impacts: they can reshape water governance and use, alter the patterns of energy use required for water application, and affect farmers’ income, labor demand as well as other socio-economic factors [

25,

26].

Building on above-reported considerations and adopting a systematic literature review approach, this paper aims to structure existing scientific knowledge on the impacts of converting traditional surface irrigation to modern systems. Despite the wide variety of available modern irrigation technologies (e.g. sensors, satellite images, IoT etc.), the study deliberately focuses on the transition from flood to drip irrigation, as this represents the most widespread and commonly adopted shift in irrigation regimes [

27]. The review aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the current state of knowledge and research on the trade-offs associated with this transition. It examines not only the effects on agricultural productivity and irrigation efficiency at the farm-scale, but also the broader environmental implications that may emerge at larger scales (e.g., basin level) as well as the possible socio-economic consequences.

In doing so, the review seeks to inform ongoing research by highlighting possible future developments and trajectories, while simultaneously gathering evidence and lessons learned to support policymaking in the field of irrigation water management.

2. Materials and Methods

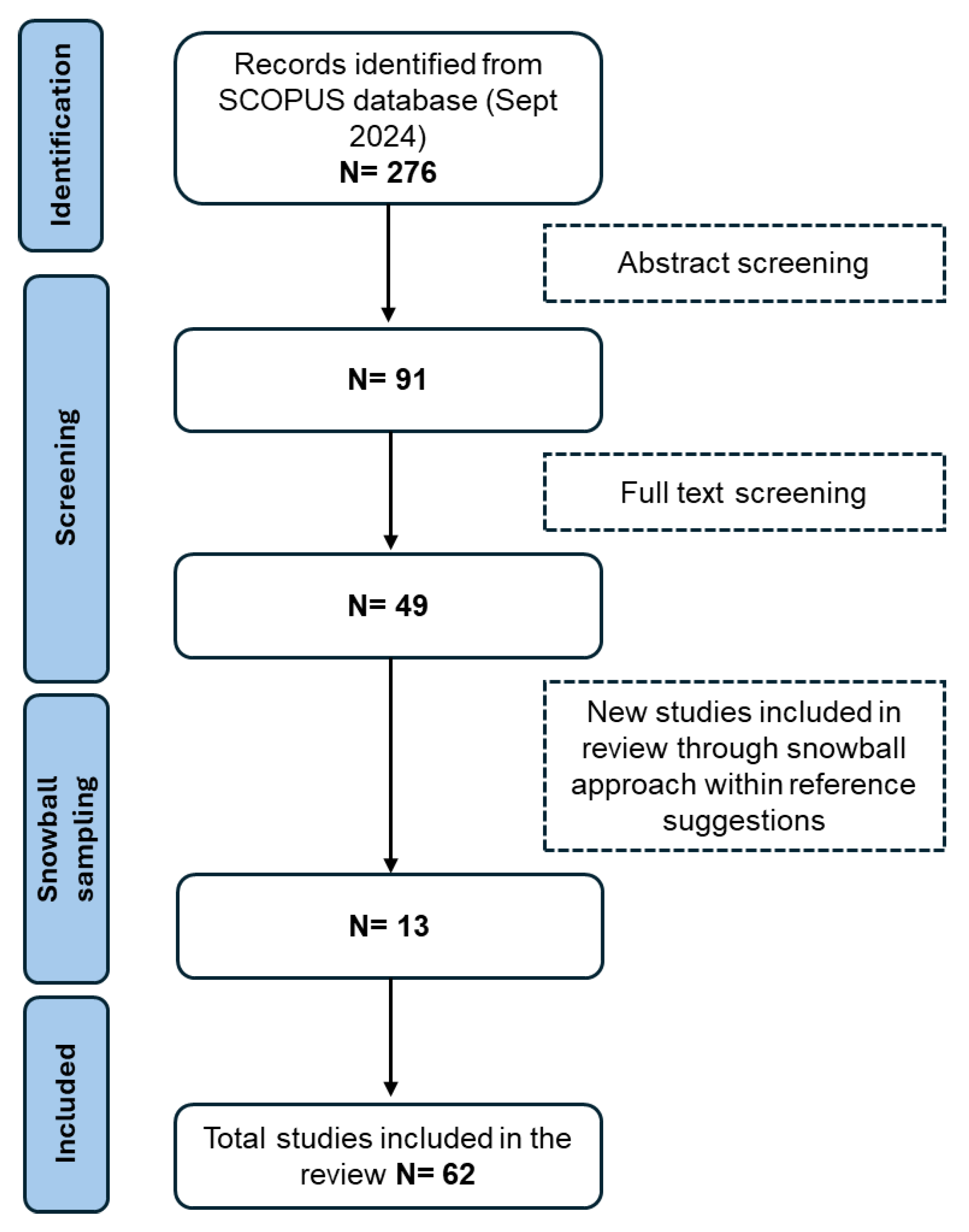

This study builds on a systematic review approach, i.e. comprehensive, transparent research conducted over scientific literature that ensures replicability and reproducibility [

28]. We conducted the literature search and review according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [

29].

Within this section, we first describe the article search and screening criteria and approaches (2.1), followed by the procedures adopted for article review and analysis (2.2).

2.1. Article Search and Screening

The systematic literature review considered publications available up to 2024, using Elsevier’s SCOPUS database (

https://www.scopus.com/). The search was limited to English-language, full-text articles published in peer-reviewed journals. Search terms applied to titles, keywords, and abstracts, were tailored to maximize the retrieval of relevant articles, focusing on combinations of terms related to irrigation regimes and their impacts. The initial search on SCOPUS returned 276 articles.

An initial abstract-based screening was then carried out to refine the selection according to the objectives of the study. Articles whose abstracts mentioned both flood and drip irrigation related terms and indicate a direct comparison between the two were retained, yielding a list of 91 articles. Then, a full text assessment was conducted to exclude conference papers and other document types, full texts not available in English, inaccessible articles, and papers deemed irrelevant based on inclusion criteria (

Table 1).

To broaden the analysis, we also included papers addressing sub-types of drip irrigation (e.g., subsurface drip irrigation) and studies comparing drip irrigation with other irrigation methods, provided that the impacts of drip irrigation could be analyzed separately.

This screening step narrowed the selection to 49 papers. To further enrich the review, additional relevant studies were identified through a snowball approach, by examining citations within the selected articles. This process resulted in the inclusion of 13 additional articles, which were screened using the above-reported criteria, resulting in a final list of 62 publications (See

Supplementary Materials). The workflow of the process followed for the systematic literature review is illustrated in

Figure 1.

2.2. Article Review and Analysis

From our final selection of 62 articles relevant information systematically extracted. For each selected paper we collected, where available, the following information:

Bibliographic information (i.e., title, authors, year of publication)

Geographical scope (i.e., continent and country level) and scale of the study (i.e., farm/field scale and larger scale such as basins, aquifers, regions)

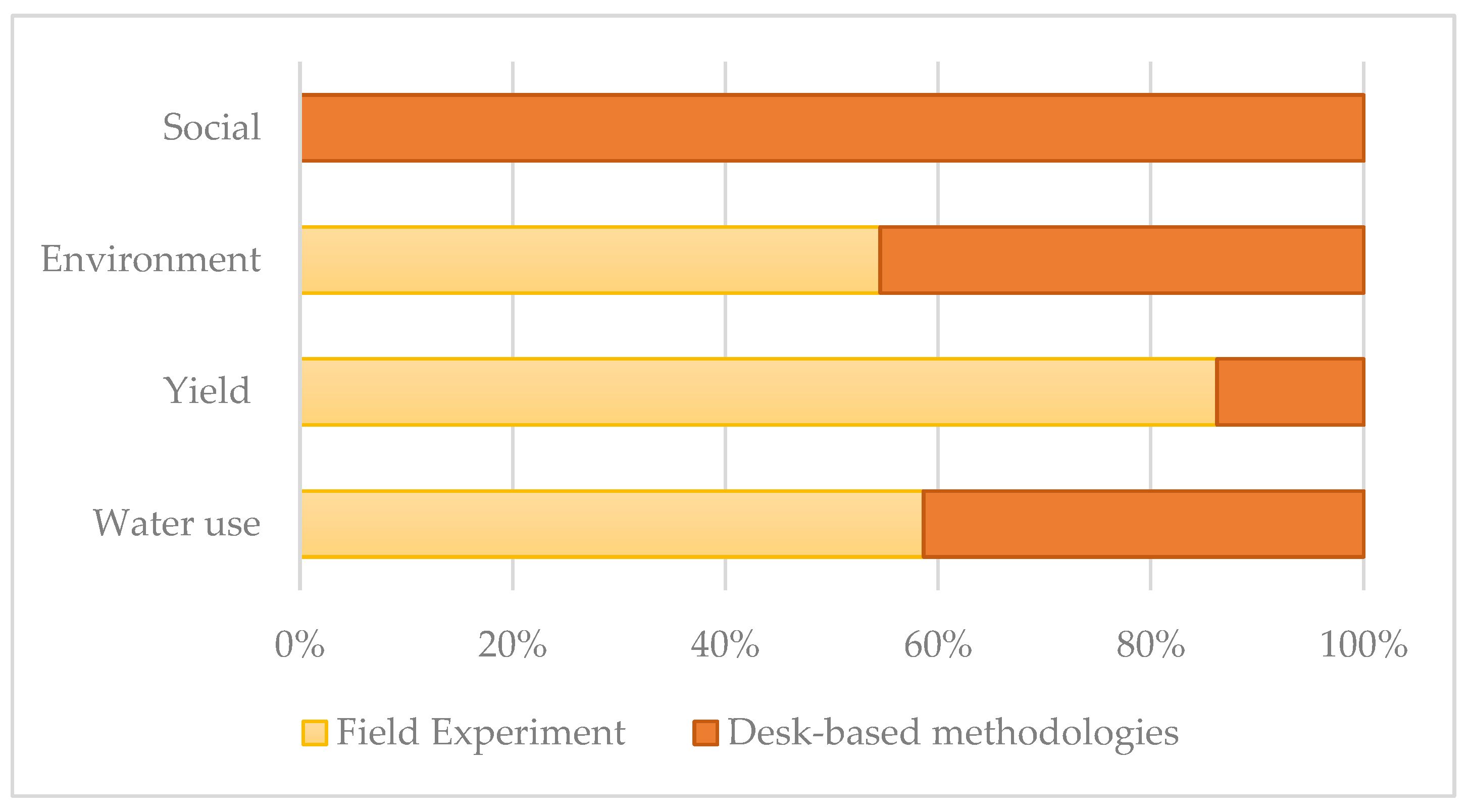

Methodological approach adopted by the study (i.e., field experiment with measurement in the field and desk-based methodologies including modeling, socio-economic analysis etc.)

Additionally, we categorized the articles based on the type of impacts described. Our analyses primarily focused on five impacts arising from the transition from flood to drip irrigation:

Water use – including impacts on water savings, irrigation efficiency i.e., the ratio of water consumed by crops relative to water applied [

30], water use efficiency (WUE) that refers to the ratio of yield relative to the water consumed (kg/m3) or water productivity (WP) that is the ratio of physical crop production or the economic value of production (in terms of gross or net value) per unit volume of water used [

31].

- 4.

Crop – covering effects on crops, such as yield or and growth and overall conditions.

- 5.

Environment – encompassing impacts on ecosystems or environmental modifications, energy consumption and greenhouse gases (GHG) emissions.

- 6.

Socio-economic aspects – addressing economic, social and cultural consequences for farmers or any other water users.

All extracted information was organized into a structured database, which was subsequently analyzed using descriptive statistics to identify publication trends over time. Descriptive statistics were also employed to examine the distribution of studies by geographical scope, scale, and impact categories. Finally, a qualitative analysis of the reported impacts was performed to capture the full range and diversity of findings across the literature.

3. Results

This section presents the results of the systematic literature review. Findings are organized according to general publication trends over time and geographical distribution (3.1), followed by an analysis of the targeted impacts of transitioning from flood to drip irrigation (3.2 and relative sub-sections).

3.1. General Trends

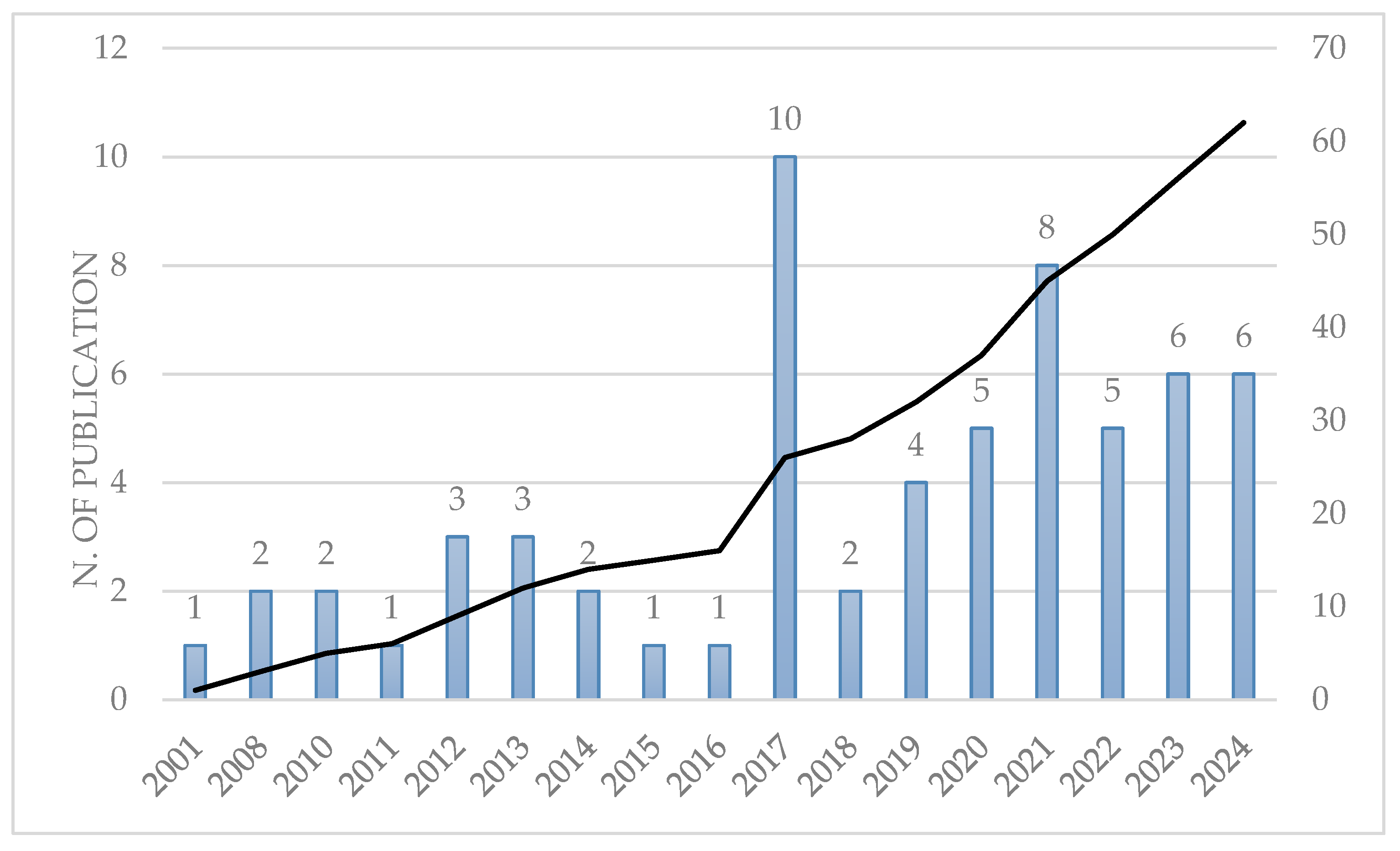

Figure 2 reports both the number of new publications per year (bars) and the cumulative number of publications over the targeted period (line). Overall, a continuous growing trend can be observed over time. The earliest identified reference dates to 2001. The annual number of papers remained stable between 2008 and 2016, then reaching a peak in 2017. After 2017, the number of annual publications dropped but subsequently increased again, reaching a plateau in the last three years.

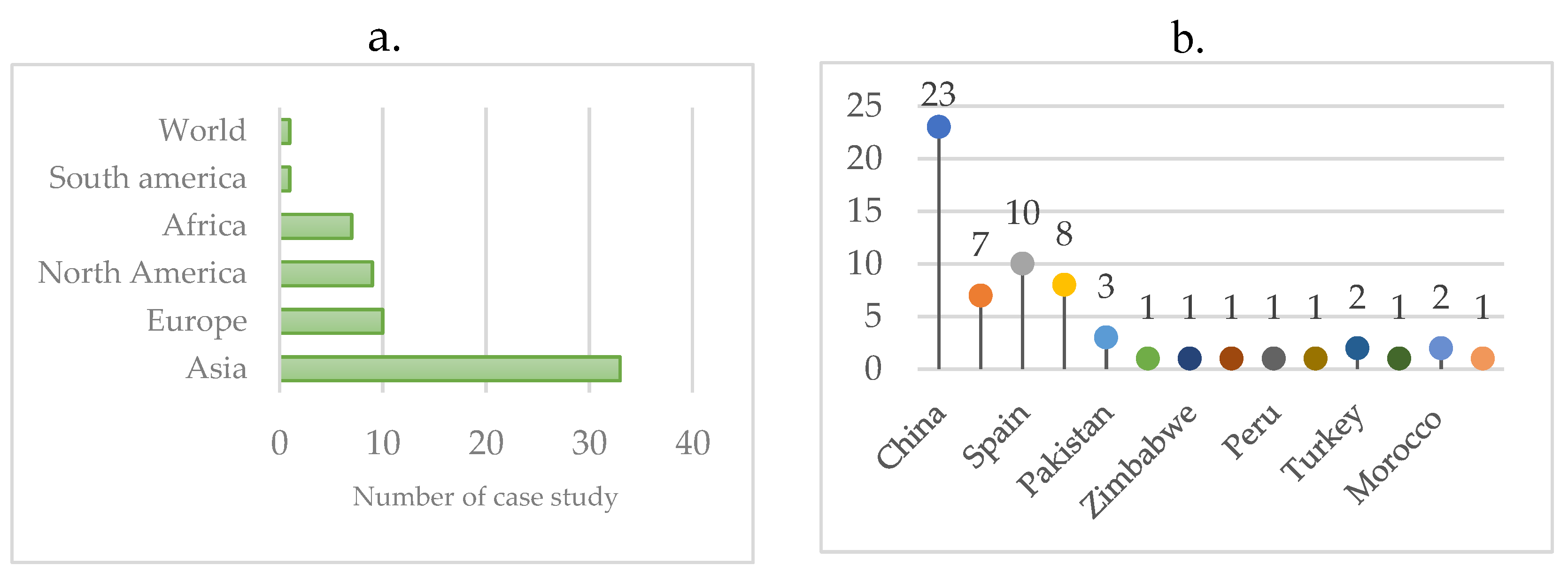

Figure 3. shows the geographical distribution of case studies included in the reviewed articles.

Most of the case studies are in Asia, with a predominant role of China (n=23), followed by India (n=8) and Pakistan (n=3). In Europe, most case studies refer to Spain followed by Turkey (n=2) while for Africa most of them are placed in Mediterranean area such, Morocco (n=2) and Egypt (n=1). For North America, case studies are primarily from the United States of America (USA) (n=7) while for South America one case studies is reported from Peru. Finally, one article considers a global scale case study. Most Chinese case studies are recent as they have been published after 2017, whereas those referring to the USA are among the earliest contributions to the existing literature.

3.2. Impacts

This section presents the impacts associated with the conversion of irrigation regimes retrieved from the reviewed paper and categorized by type of impact. Given the heterogeneity of papers, we adopted a descriptive approach. First, we reported an overview about impacts and then we addressed each impact category individually.

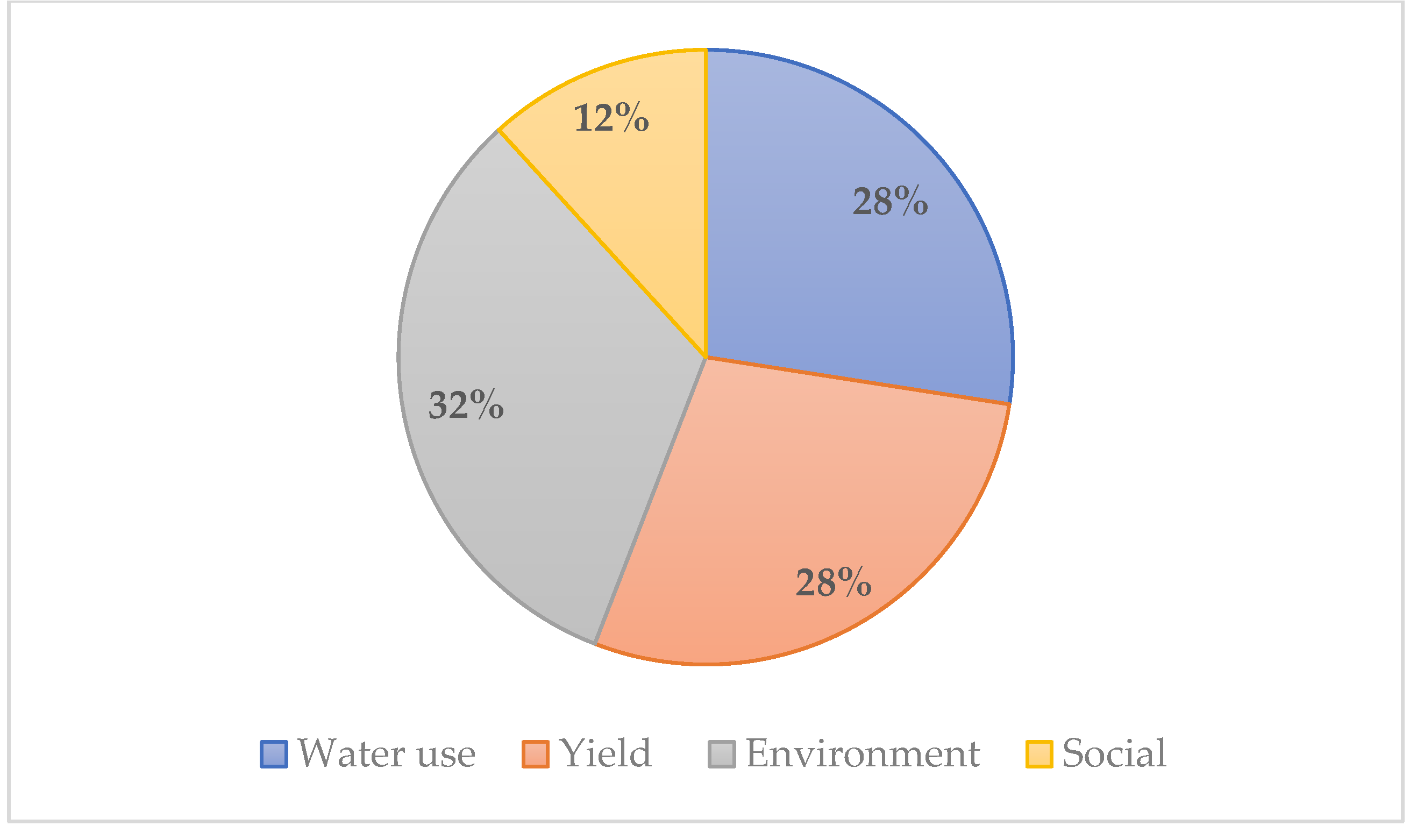

As reported in

Figure 4, most of the reviewed articles focus on environmental impacts (32%) followed by crop yield (28%) and water use (28%) impacts, while social impacts are less covered, being addressed in only 12% of the studies. It is important to note that many selected papers report multiple impact types at once (e.g., water savings and yield improvement, or water and energy savings), making it challenging in some cases to assign them to a single impact category. When this occurred, individual studies were classified under multiple impact categories. Since the figure reports percentage values, the total could not in any case be equal to the number of studies.

Almost all articles addressing water use and yield impacts adopt field experiment methodologies at plot or farm scale to quantify yield increase and WUE improvement. In contrast, articles assessing environmental and social impacts applied a broader range of desk-based methodologies - such as modelling, surveying, econometric analysis etc. - typically applied at a larger spatial scale, e.g., basin, aquifer scale or regional scale) (

Figure 5).

3.2.1. Water Use Impacts

The conversion from flood to drip irrigation generally leads to significant water saving and improvements in WUE at the field scale, as water is applied directly to the crop root zone, minimizing surface runoff, deep percolation, and evaporation losses. For example, [

32] reported approximately 44% water savings for sugarcane in two irrigation districts in India. For staple cash crops, such as maize and wheat, drip irrigation improves WUE and water savings compared to flood irrigation [

33,

34,

35,

36]. In a mixed cropping system, Jahan Leghari et al. [

37] found annual water savings of 34% for winter wheat and 36 % to 40 % for summer and spring maize. Wang et al. [

38] observed an increase in maize irrigation water productivity from 3.51 kg m

−3 under flood irrigation to 4.58 kg m

−3 under drip irrigation, partly due also to the contribution of shallow groundwater.

Water savings resulting from converting traditional flood irrigation to drip irrigation have also been found for other crops such as sunflowers (about 95% of water saved) [

39], olive (63-77%) [

40] and citrus (55%) [

41]. Ali et al. [

42] reported a decrease of water use from 487m

3 to 1,200m

3 in cotton production. Moreover, switching from flood irrigation to drip irrigation have been reported to increase WUE by 60.3% in jujube cultivation [

43].

While the benefits of drip irrigation on increasing water savings and WUE at farm-scale are largely demonstrated, its impact on water use at the basin scale can vary significantly. Evidence suggests that reductions in water consumption associated to drip irrigation at the field level are often accompanied by an expansion of irrigated land and crop intensification, which may offset the initial water saving and lead to an increased overall consumptive use water [

18,

25,

44,

45,

46].

3.2.2. Crop Impacts

Drip irrigation is largely recognized for having positive effects on crops, primarily by delivering water directly to the root zone thereby minimizing water losses due to evaporation and surface runoff. Results from the literature review indicate that studies comparing flood and drip irrigation in terms of crop impacts generally highlight the benefits of drip irrigation in (i) increasing crop yield, (ii) enhancing nitrogen (N) use efficiency, (iii) improving overall plant growth and (iv) stabilizing the root zone.

Table 2 reports selected studies reporting positive crops impacts associated with drip irrigation with respect to different crops and across different case studies.

As illustrated in

Table 2, studies addressing the impacts of the conversion from flood to drip irrigation on crops concentrate predominantly on assessing yield, with all of them reporting yield increases associated with the adoption of drip irrigation. On the contrary all other crop impacts are significantly less considered, emerging in 12 to 20% of studies dealing with crop impacts.

3.2.3. Environmental Impacts

Reviewed articles predominantly examine the effects of irrigation regime changes on groundwater recharge. Flood irrigation is generally recognized to ensure a greater recharge intensity than drip irrigation, due to return flows that sustain higher groundwater levels [

38,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67]. For instance, [

65] investigated the spatiotemporal effects of the transition from flood to drip irrigation on groundwater recharge in the semi-arid Mediterranean region of Valencia using a hydrogeological model. Their results suggest the critical role of flood irrigation in maintaining groundwater levels, particularly in areas characterized by large precipitation variability. Similarly, Wael et al. [

66] found that in semiarid and arid regions, like northern Egypt, water-saving irrigation systems reduced recharge intensity compared to flood irrigation, leading to a decline in groundwater levels with implications for potable water provision. Reported declines in groundwater table range between 10 and 50 cm, though the effect was partly mitigated by greater clay depth.

Field experiments in China further confirm this trend. Wang et al. [

38] observed that flood irrigation contributes to aquifer recharge, whereas drip irrigation results exclusively in shallow groundwater extraction. Likewise, Jin et al. [

63] reported negative implications for the stability of regional groundwater resources when drip irrigation replaced flood irrigation. When combined with climate change projections, the shift to drip irrigation is associated with further reductions in mean groundwater recharge, particularly under drier future conditions [

64].

Beyond recharge, irrigation return flows from irrigation also affects groundwater quality. Flood irrigation can therefore contribute to aquifer salinization, while drip irrigation has the potential to mitigate this effect due to reduced deep percolation [

68]. Moreover, drip irrigation can reduce N leaching by improving N use efficiency [

37] while also lowering heavy metal accumulation at the soil surface [

69] even under wastewater application [

70].

Another emerging strand of literature concerns GHG emissions from agricultural soils. Indeed, irrigation methods influence the release of GHG such as carbon dioxide (CO

2), nitrous oxide (N

2O), nitric oxide (NO) and methane (CH

4). Several studies show that drip irrigation can effectively mitigate GHG emission compared to flood irrigation [

34,

54,

55,

71]

Finally, the transition to drip irrigation has important implications for energy consumption. While drip irrigation is typically associated with higher energy requirement due to pressurized water pumping [

44,

48], Narayanamoorthy [

32] reports significant electricity saving (about 1,059 kWh/ha) for sugarcane farmers using drip irrigation compared to flood irrigation. Where groundwater is required for irrigation, efficiency gains in water use may also reduce total pumping volumes and energy demand [

72].

3.2.4. Socio-Economic Impacts

The conversion from traditional flood irrigation systems to drip systems entails significant economic and social changes for irrigation water users, particularly farmers. The long-term viability of this transition is closely tied to its economic sustainability, as farmers are more likely to adopt dripping irrigation when it reduces financial burdens [

73].

Evidence from the literature, however, highlights both benefits and drawbacks. According to Hussain et al. [

74], for example, despite of its potential on water savings drip irrigation in sugarcane production in Pakistan resulted in net economic losses due to high installation and maintenance costs compared with traditional flood irrigation. Similarly, in Zimbabwe, smallholder farmers found flood irrigation to be more financially and economically viable than drip irrigation in the long-term. as the higher energy costs of drip systems outweighed savings on water and fertilizer inputs [

75]. In Spain, the modernization of irrigation has raised domestic agriculture productivity, but farmer incomes have not increased significantly due to higher water and energy costs. Higher energy requirements for drip irrigation increase total maintenance cost and farmers often respond by applying deficit irrigation to maximize profits, thus balancing production with financial sustainability [

44].

Other studies point to more positive outcomes under certain conditions. In the arid northwestern China, data collected from 228 farmers reveal that the transition from flood to drip irrigation has a positive effect on gross margin only for those farmers less constrained by water availability. Where access to water remains limited, profitability of drip irrigation systems diminishes, despite rising water scarcity [

76]. Furthermore, although the adoption of drip irrigation often results in increased energy expenditures, it can reduce costs for other agricultural inputs, notably fertilizers and herbicides, through more efficient input application [

42].

Beyond economic considerations, drip irrigation can also reshape water governance and social practices. At the basin scale, the adoption of more efficient irrigation systems may alter the distribution of water supply, potentially undermining existing water right holders relying on the return flows from traditional flood irrigation practices [

18].

At the organizational level, the shift to drip systems has transformed irrigation communities and water user associations (WUAs). For example, Ortega-Reig et al. [

77] described how drip irrigation led to new collective rules on water allocation in three collective irrigation systems in Valencia (Spain). Decisions on irrigation scheduling are now main responsibility of WUA whereas in absence of drip automated famers were able to independently make decisions. The introduction of drip irrigation also led to the implementation of new rules for water distribution setting a maximum water use per day or limits in volumes. In some areas, dual (i.e., both drip and surface) irrigation systems persist, as farmers want to maintain surface irrigation as a backup solution despite increased costs associated with the cleaning and maintenance of channels. Within WUA, the conversion to drip irrigation reshaped traditional collective irrigation organizations rearranging their internal structure and fostering increased centralization to increase technical and economic efficiency.

Finally, the transition to drip irrigation can also carry cultural implications. Traditional irrigation systems have shaped landscapes, social relations, and cultural identity for centuries. In the Cànyoles Valley (Spain) one of the consequences of the conversion from flood to drip irrigation is the loss of cultural heritage. Indeed, many of the ancient canals, used before the shift to drip irrigation, have been abandoned or disused and the same occurred for other traditional infrastructures such as mills and underground canals [

25].

4. Discussion

This section discusses results reported within

Section 3. Discussion focuses on trade-offs (4.1) and policy discourse (4.2). Finally, research limitations and possible future developments are presented (4.3).

4.1. Trade-Offs

In this study, trade-offs are understood as evidence-based patterns of conflicting impacts identified across the reviewed literature. Building on this concept, this section outlines and discusses the main trade-offs associated with the conversion from flood to drip irrigation.

Though the conversion from flood to drip irrigation is regarded as an effective measure to save water and increase WUE at farm-scale, higher irrigation efficiency does not necessarily translate into reduced water consumption at watershed or basin scale [

27]. The paradox of irrigation efficiency [

13] can be better understood by distinguishing between consumptive and non-consumptive uses of irrigation water [

78]. Consumptive use comprises both beneficial consumption (e.g., crop transpiration) and non-beneficial consumption (e.g., weed transpiration, evaporation from wet soil or open water surfaces). Non-consumptive use refers to flows that are not consumed by crops but re-enter the hydrological system, either as recoverable flows (e.g., drainage and runoff that recharge aquifers and surface water bodies) and non-recoverable flows (e.g., losses to the ocean) [

13,

78].

Improved irrigation efficiency is typically associated with an increase in beneficial consumption, which in turn results in higher yields while at the same time reducing non-beneficial consumption and non-consumptive use. However, these reductions do not necessarily translate into real water savings, since the “saved” water often corresponds to return flows that sustain groundwater recharge [

79,

80] or downstream availability. As shown by our results, flood irrigation generates more return flows than drip irrigation. Consequently, the conversion from flood to drip irrigation may generate trade-offs between improved on-farm irrigation efficiency and the maintenance of water flows supporting ecosystem processes [

20], including off-farm irrigation dependent ecosystem services [

81]. Altered return flows may also reduce water availability for other uses [

82] and complicate water governance [

18,

83], thereby shaping trade-offs in terms of water accessibility.

Increased irrigation efficiency at farm-scale generates water savings and additional revenues to the farmers that often enable the expansion of irrigated areas, crop intensification, or the shift to higher water-demanding crops. All these processes ultimately contribute increasing water use at larger scales [

25,

46,

84] This rebound effect is frequently reinforced by subsidies for irrigation system modernization [

18]. While drip irrigation is often presented as a key solution for water conservation, evidence shows that farmers are generally more motivated by the prospect of higher yields and profits than by conserving water resources [

73,

77,

85]. As a result, efficiency gains at farm-scale may not translate into basin-scale water conservation, but instead into rational farm-level strategies instead into rational farm-level strategies aligned with market forces and subsidies [

86]. These dynamics produce trade-offs between productivity gains at farm-scale and water conservation at basin-scale.

From a socio-economic perspective, drip irrigation can enhance farm profitability by increasing yield while reducing cultivation costs associated to farm-inputs like fertilizers and herbicides [

26]. However, its high upfront investments, maintenance and energy costs remain major barriers. For smallholders and farmers in developing countries, financial and technical constraints often turn drip irrigation economically unviable despite its water savings potential [

15] thus favoring traditional irrigation schemes [

74,

75]. These dynamics risk reinforcing inequalities among farmers, as wealthier producers better positioned to access subsidies, credit, or technical support (e.g., extension services, advisory services etc.), while smallholders farmers risk exclusion and rising vulnerability.

The transition from flood to drip irrigation also entails trade-offs in terms of GHG emissions and energy use. On the one hand, drip irrigation has the potential to mitigate soil-related emissions lowering CH₄ and N₂O emissions compared to flood irrigation [

55]. On the other hand, drip irrigation systems typically increase the energy intensity and carbon footprint of irrigation [

87]. The balance between these outcomes depends on multiple context-specific factors, including e.g., the choice of the pumping systems [

88], the irrigation water source [

72] and the regional energy mix. These complexities highlight the need to assess trade-offs at the intersection of farm-scale performance and broader socio-environmental sustainability.

This can also be understood as a need to explore further possible trade-offs (as well as synergies) between private (e.g., crops) and public or semi-public goods (e.g., ecosystem conservation). Our results indicate that, to date, research on the impacts of converting from flood to drip irrigation has predominantly focused on agricultural profitability, considering increases in crop yield, water savings, and, at the economic level, farmers’ income or farm financial sustainability. This seems to suggest a prevalent focus on traditional farm economics, centered at a classical economic approach emphasizing the importance of private goods. From an ecosystem approach [

89], such an approach narrows the analysis to provisioning services alone, overlooking broader ecosystem functions and services. Indeed, none of the socio-economic studies have assess in economic/monetary terms the potential environmental externalities – whether positive or negative – arising from the conversion of irrigation regimes. This confirms a lack of focus on public goods as well as regulating and cultural ecosystem services. If examined through the lens of the Water-Energy-Food-Ecosystem (WEFE) nexus framework [

90,

91,

92], this denotes a stronger emphasis on the food dimension especially compared to the ecosystem component [

93].

4.2. Policy Discourse

Policies targeting efficient and sustainable water use played a central role in promoting the modernization of irrigation systems. Those policies, encouraging or directly subsidizing water-saving irrigation techniques, are directly aimed at achieving water conservation in a context unsustainable water management, growing demand and water scarcity worsened by ongoing climate change. Public programs that would subsidize the adoption of drip irrigation are diffused worldwide following UN water agenda [

94] and to comply with UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6.4 seek to increase water use efficiency. For instance, the EU provides financial support for the adoption of drip irrigation through the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), a policy instrument that has been widely criticized for pursuing conflicting objectives of economic viability and environmental sustainability while also reinforcing unfair competition among farmers [

95]. In the USA increased public subsidies for water conservation technologies resulted in increased economic benefits both at farm and basin level, however also led to an increase in water consumption [

96]. Even in arid and water scarce areas such as the countries of the Near East and North Africa (NENA) Region, the introduction of drip irrigation in absence of water allocation policies translated into more water consumed [

27].

Yet, a major contradiction emerges between water conservations objectives and the actual impacts on intensification and expansion of agriculture [

10,

97] since these policies are usually designed considering irrigation water primarily for production purposes, adopting a silo approach and thereby accentuating potential trade-offs. In this context, economic incentives and subsidies can even worsen existing negative externalities associated with the adoption of modern irrigation technologies [

83,

98]. Therefore, if the final objective is water conservation, enhancing water efficiency through the adoption of modern irrigation technologies is necessary but not sufficient [

99]. The modernization of irrigation systems should be coupled with ad hoc policies such as measures that limit agricultural expansion at the expense of natural ecosystems [

100] or the introduction of water charges and tariffs to regulate water consumption [

99].

4.3. Research Limitations and Future Developments

This review presents some limitations that should be acknowledged. First, this review included only publications written in English, thereby excluding potentially relevant studies published in other languages. Second, the initial screening did not consider grey literature such as technical or institutional reports, which could have been particularly relevant for country-level analyses; only one institutional report was included through citation analysis. Third, as already mentioned, this study focuses exclusively on the conversion from flood to drip irrigation. While such a strict focus was necessary to simplify the analysis and make it feasible, it inevitably excludes other irrigation techniques that could reshape the trade-offs identified. Lastly, the analysis relies on the availability of existing studies, which are often heterogeneous in terms of geographical focus, methodological approaches, and indicators used to assess trade-offs. As a result, direct comparisons remain challenging.

5. Conclusions

This review shows that the conversion from flood to drip irrigation generates a complex set of trade-offs, demonstrating that irrigation modernization cannot be considered as a panacea for water conservation.

At the field scale, drip irrigation offers clear benefits, including higher yields, improved water-use efficiency, reduced agrochemical inputs, and lower soil-based GHG emissions. However, these advantages are offset by significant environmental and socio-economic costs.

At the basin scale, efficiency gains often translate into higher consumptive use and evapotranspiration, reducing return flows that sustain aquifers, ecosystems, and downstream users. In parallel, the high investment and maintenance costs of drip systems create barriers for smallholders and risk reinforcing inequalities, while the increased energy demand may erode some of the environmental gains. These findings highlight a potential contradiction between the stated objectives of policies aiming to promote water conservation and their actual outcomes once enforced and implemented in practice on the ground.

To reconcile productivity gains with sustainable water use, irrigation modernization efforts must move beyond a narrow technological focus. Coherent governance frameworks are essential, including regulation of water abstraction, economic instruments such as tariffs, and safeguards against irrigated area expansion. This also calls for stronger integration and coordination across policy domains, avoiding siloed approaches and fostering synergies between – among others – agricultural, rural development, environmental, and economic policies. Another urgent priority is the design and implementation of mechanisms to value, compensate, and account for the environmental benefits –particularly ecosystem services – supported by farming practices and, in particular, by traditional irrigation systems. Only through such integrated and multi-scale approaches can drip irrigation fulfill its potential to strengthen agricultural resilience while contributing to long-term water conservation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S., and M.M.; methodology, A.S and M.M..; software, A.S., and M.M; validation, A.S, M.M and D.P; formal analysis, A.S.; investigation, A.S, and M.M; resources, A.S., and M.M; data curation, A.S., and M.M; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.; writing—review and editing, A.S, M.M., G.A., D.P.; visualization, A.S. and M.M..; supervision, M.M., G.A., D.P.; project administration, M.M..; funding acquisition, M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by European Union - Next Generation EU, Mission 4, Component 2 CUP C96E22000130005.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments). Where GenAI has been used for purposes such as generating text, data, or graphics, or for study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, please add “During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used [tool name, version information] for the purposes of [description of use]. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.”

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WUE |

Water use efficiency |

| WP |

Water productivity |

| GHG |

Greenhouse gases emissions |

| WUA |

Water Users Association |

References

- K. Biswas and C. Tortajada, “Assessing Global Water Megatrends,” 2018, pp. 1–26. [CrossRef]

- UN-Water, “The United Nations World Water Development Report 2019: Leaving No One Behind,” Ubiquity Press, 2019. [CrossRef]

- IPCC, AR5 Synthesis Report: Climate Change 2014 — IPCC, vol. 218, no. 2. 2014. Accessed: Apr. 26, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/syr/.

- FAO, “THE STATE OF FOOD AND AGRICULTURE: CLIMATE CHANGE, AGRICULTURE AND FOOD SECURITY,” 2016, Accessed: Apr. 24, 2022. [Online]. Available: www.fao.org/publications.

- J. Jägermeyr, A. Pastor, H. Biemans, and D. Gerten, “Reconciling irrigated food production with environmental flows for Sustainable Development Goals implementation,” Nat. Commun., vol. 8, no. 1, p. 15900, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- FAO, The State of Food and Agriculture 2020. 2020. [CrossRef]

- IPCC, “Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland.,” Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Onyena and K. Sam, “The blue revolution: sustainable water management for a thirsty world,” Discov. Sustain., vol. 6, no. 1, p. 63, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Iglesias and L. Garrote, “Adaptation strategies for agricultural water management under climate change in Europe,” Agric. Water Manag., vol. 155, pp. 113–124, Jun. 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Berbel, A. Expósito, C. Gutiérrez-Martín, and L. Mateos, “Effects of the Irrigation Modernization in Spain 2002–2015,” Water Resour. Manag., vol. 33, no. 5, pp. 1835–1849, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. P. McCartney, L. Whiting, I. Makin, B. A. Lankford, and C. Ringler, “Rethinking irrigation modernisation: realising multiple objectives through the integration of fisheries,” Mar. Freshw. Res., vol. 70, no. 9, p. 1201, 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. Hoffmann and S. Villamayor-Tomas, “Irrigation modernization and the efficiency paradox: a meta-study through the lens of Networks of Action Situations,” Sustain. Sci., vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 181–199, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Q. Grafton et al., “The paradox of irrigation efficiency,” Science (80-. )., vol. 361, no. 6404, pp. 748–750, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- European Parliament and the Council of the European Union, “Regulation (EU) No 1305/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 December 2013 on support for rural development by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) and repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 1698/2005,” 2013, Official Journal of the European Union.

- J. P. Venot, M. Kuper, and M. Zwarteveen, Drip Irrigation for Agriculture. Routledge, 2017. [CrossRef]

- F. R. Lamm et al., “A 2020 Vision of Subsurface Drip Irrigation in the U.S.,” Trans. ASABE, vol. 64, no. 4, pp. 1319–1343, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Ticehurst and A. L. Curtis, “The intention of irrigators to adopt water use efficient measures: case studies in the north and south of the Murray–Darling Basin,” Australas. J. Water Resour., vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 149–161, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- F. A. Ward and M. Pulido-Velazquez, “Water conservation in irrigation can increase water use,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., vol. 105, no. 47, pp. 18215–18220, Nov. 2008. [CrossRef]

- Contor and R. G. Taylor, “WHY IMPROVING IRRIGATION EFFICIENCY INCREASES TOTAL VOLUME OF CONSUMPTIVE USE,” Irrig. Drain., vol. 62, no. 3, pp. 273–280, Jul. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Scott, S. Vicuña, I. Blanco-Gutiérrez, F. Meza, and C. Varela-Ortega, “Irrigation efficiency and water-policy implications for river basin resilience,” Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 1339–1348, Apr. 2014. [CrossRef]

- T. Wagener et al., “The future of hydrology: An evolving science for a changing world,” Water Resour. Res., vol. 46, no. 5, May 2010. [CrossRef]

- Masseroni et al., “Prospects for Improving Gravity-Fed Surface Irrigation Systems in Mediterranean European Contexts,” Water, vol. 9, no. 1, p. 20, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- P. Séraphin, C. Vallet-Coulomb, and J. Gonçalvès, “Partitioning groundwater recharge between rainfall infiltration and irrigation return flow using stable isotopes: The Crau aquifer,” J. Hydrol., vol. 542, pp. 241–253, Nov. 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. Poch-Massegú, J. Jiménez-Martínez, K. J. Wallis, F. Ramírez de Cartagena, and L. Candela, “Irrigation return flow and nitrate leaching under different crops and irrigation methods in Western Mediterranean weather conditions,” Agric. Water Manag., vol. 134, pp. 1–13, Mar. 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Sese-Minguez, H. Boesveld, S. Asins-Velis, S. van der Kooij, and J. Maroulis, “Transformations accompanying a shift from surface to drip irrigation in the Cànyoles Watershed, Valencia, Spain,” Water Altern., vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 81–99, 2017.

- M. García-Mollá, R. P. Medina, V. Vega-Carrero, and C. Sanchis-Ibor, “Economic efficiency of drip and flood irrigation. Comparative analysis at farm scale using DEA,” Agric. Water Manag., vol. 309, p. 109314, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Perry, P. Steduto, and F. Karajeh, Does improved irrigation technology save water? A review of the evidence, vol. 42, no. 2. 2017. [Online]. Available: www.fao.org/publications%0Ahttps://www.researchgate.net/publication/317102271.

- Tranfield, D. Denyer, and P. Smart, “Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review,” Br. J. Manag., vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 207–222, Sep. 2003. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Page et al., “The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews,” BMJ, p. n71, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- W. Israelsen, Irrigation Principles the Practices, 2nd editio. New York, 1950.

- M. E. Jensen, “Beyond irrigation efficiency,” Irrig. Sci., vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 233–245, Mar. 2007. [CrossRef]

- Narayanamoorthy, “Economic Impact of Drip Irrigation in India: An Empirical Analysis with Farm Level Data,” 2022, pp. 329–360. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Leghari, K. Hu, Y. Wei, T. Wang, T. A. Bhutto, and M. Buriro, “Modelling water consumption, N fates and maize yield under different water-saving management practices in China and Pakistan,” Agric. Water Manag., vol. 255, p. 107033, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Mehmood et al., “Optimizing irrigation management sustained grain yield, crop water productivity, and mitigated greenhouse gas emissions from the winter wheat field in North China Plain,” Agric. Water Manag., vol. 290, p. 108599, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Wang, X. Li, and J. Tan, “Interannual Variations of Evapotranspiration and Water Use Efficiency over an Oasis Cropland in Arid Regions of North-Western China,” Water, vol. 12, no. 5, p. 1239, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, M. Gao, H. Chen, X. Fu, L. Wang, and R. Wang, “Soil moisture and salinity dynamics of drip irrigation in saline-alkali soil of Yellow River basin,” Front. Environ. Sci., vol. 11, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Jahan Leghari, K. Hu, Y. Wei, T. Wang, and Y. Laghari, “Modelling the effects of cropping systems and irrigation methods on water consumption, N fates and crop yields in the North China Plain,” Comput. Electron. Agric., vol. 218, p. 108677, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- X. Wang, Z. Huo, H. Guan, P. Guo, and Z. Qu, “Drip irrigation enhances shallow groundwater contribution to crop water consumption in an arid area,” Hydrol. Process., vol. 32, no. 6, pp. 747–758, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Dong, Y. Kang, S. Wan, X. Li, and J. Miao, “Drip-irrigation using highly saline groundwater increases sunflower yield in heavily saline soil,” Agron. J., vol. 113, no. 3, pp. 2950–2959, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Sikaoui, V. Nangia, M. Karrou, and T. Oweis, “Improved on-farm irrigation management for olive growing - A case study from Morocco,” Ann. Arid Zone, vol. 55, no. 3–4, pp. 147–151, 2016.

- M. B. S. Raza, A.; Zaka, M. A; Khurshid T. ; Nawaz, M. A.; W. Ahmed, W. ; Afzal, “DIFFERENT IRRIGATION SYSTEMS AFFECT THE YIELD AND WATER USE EFFICIENCYOF KINNOW MANDARIN (CITRUS RETICULATA BLANCO.),” J. Anim. Plant Sci., vol. 30, no. 5, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Y. Ali, S. Saleem, M. N. Irshad, A. Mehmood, M. Nisar, and I. Ali, “Comparative study of different irrigation system for cotton crop in district Rahim Yar khan, Punjab, Pakistan,” Int. J. Agric. Ext., vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 131–138, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Z. Li, R. Zong, T. Wang, Z. Wang, and J. Zhang, “Adapting Root Distribution and Improving Water Use Efficiency via Drip Irrigation in a Jujube (Zizyphus jujube Mill.) Orchard after Long-Term Flood Irrigation,” Agriculture, vol. 11, no. 12, p. 1184, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Rodríguez-Díaz, L. Pérez-Urrestarazu, E. Camacho-Poyato, and P. Montesinos, “The paradox of irrigation scheme modernization: more efficient water use linked to higher energy demand,” Spanish J. Agric. Res., vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 1000–1008, Nov. 2011. [CrossRef]

- INTERA, “Remote-Sensing-Based Comparison of Water Consumption By Drip-Irrigated Versus Flood-Irrigated Fields,” Intera, 2013, [Online]. Available: http://www.ose.state.nm.us/Basins/Colorado/AWSA/Studies/2013_Intera_DmingFldDripRpt.pdf.

- Sampedro-Sanchez, “Can Irrigation Technologies Save Water in Closed Basins? The effects of Drip Irrigation on Water Resources in the Guadalquivir River Basin (Spain),” Water Altern., vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 501–522, 2022.

- Küçükyumuk, E. Kaçal, A. Ertek, G. Öztürk, and Y. S. K. Kurttaş, “Pomological and vegetative changes during transition from flood irrigation to drip irrigation: Starkrimson Delicious apple variety,” Sci. Hortic. (Amsterdam)., vol. 136, pp. 17–23, Mar. 2012. [CrossRef]

- P. L. Eranki, D. El-Shikha, D. J. Hunsaker, K. F. Bronson, and A. E. Landis, “A comparative life cycle assessment of flood and drip irrigation for guayule rubber production using experimental field data,” Ind. Crops Prod., vol. 99, pp. 97–108, May 2017. [CrossRef]

- Montazar, D. Zaccaria, K. Bali, and D. Putnam, “A Model to Assess the Economic Viability of Alfalfa Production Under Subsurface Drip Irrigation in California,” Irrig. Drain., vol. 66, no. 1, pp. 90–102, Feb. 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. S. Jat et al., “Re-designing irrigated intensive cereal systems through bundling precision agronomic innovations for transitioning towards agricultural sustainability in North-West India,” Sci. Rep., vol. 9, no. 1, p. 17929, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Kumar Jha et al., “Response of growth, yield and water use efficiency of winter wheat to different irrigation methods and scheduling in North China Plain,” Agric. Water Manag., vol. 217, pp. 292–302, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- Q. Liu et al., “Drip Irrigation Elevated Olive Productivity in Southwest China,” Horttechnology, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 122–127, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Umair et al., “Water-Saving Potential of Subsurface Drip Irrigation For Winter Wheat,” Sustainability, vol. 11, no. 10, p. 2978, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Gao, C. Xu, N. Luo, X. Liu, S. Huang, and P. Wang, “Mitigating global warming potential while coordinating economic benefits by optimizing irrigation managements in maize production,” J. Environ. Manage., vol. 298, p. 113474, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. M. Andrews, P. M. Homyak, P. Y. Oikawa, J. Wang, and G. D. Jenerette, “Water-conscious management strategies reduce per-yield irrigation and soil emissions of CO2, N2O, and NO in high-temperature forage cropping systems,” Agric. Ecosyst. Environ., vol. 332, p. 107944, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. KUMAR, A. NIBHORIA, P. K. YADAV, SATYAJEET, M. JAT, and S. K. ANTIL, “Relative performance of drip irrigation in comparison to conventional methods of irrigation in Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) in south-west Haryana,” Indian J. Agric. Sci., vol. 93, no. 12, pp. 1320–1325, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. MERZA, H. ATAB, Z. AL-FATLAWI, and S. ALSHARIFI, “EFFECT OF IRRIGATION SYSTEMS ON RICE PRODUCTIVITY,” SABRAO J. Breed. Genet., vol. 52, no. 2, pp. 587–597, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Li, W. Han, and M. Peng, “Effects of drip and flood irrigation on carbon dioxide exchange and crop growth in the maize ecosystem in the Hetao Irrigation District, China,” J. Arid Land, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 282–297, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, H. Upreti, and G. Das Singhal, “Crop water stress index and its sensitivity to meteorological parameters and canopy temperature,” Theor. Appl. Climatol., vol. 155, no. 4, pp. 2903–2915, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang et al., “Response of fragrant pear quality and water productivity to lateral depth and irrigation amount,” Agric. Water Manag., vol. 292, p. 108652, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- H.-L. Liu, X. Chen, A.-M. Bao, L. Wang, X. Pan, and X.-L. He, “Effect of Irrigation Methods on Groundwater Recharge in Alluvial Fan Area,” J. Irrig. Drain. Eng., vol. 138, no. 3, pp. 266–273, Mar. 2012. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhao, H. Xu, P. Zhang, Y. Bai, and Q. Zhang, “Impact of Changing Irrigation Patterns on Saltwater Dynamics of Soil in Farmlands and their Shelterbelts in the Irrigated Zone of Kalamiji Oasis,” Irrig. Drain., vol. 64, no. 3, pp. 393–399, Jul. 2015. [CrossRef]

- X. Jin, M. Chen, Y. Fan, L. Yan, and F. Wang, “Effects of Mulched Drip Irrigation on Soil Moisture and Groundwater Recharge in the Xiliao River Plain, China,” Water, vol. 10, no. 12, p. 1755, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Pool et al., “From Flood to Drip Irrigation Under Climate Change: Impacts on Evapotranspiration and Groundwater Recharge in the Mediterranean Region of Valencia (Spain),” Earth’s Futur., vol. 9, no. 5, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Pool et al., “Hydrological Modeling of the Effect of the Transition From Flood to Drip Irrigation on Groundwater Recharge Using Multi-Objective Calibration,” Water Resour. Res., vol. 57, no. 8, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Wael, P. Riad, N. Ali Hassan, and E. Ragab Nofal, “Assessment of modern irrigation versus flood irrigation on groundwater potentiality in old clayey lands,” Ain Shams Eng. J., vol. 15, no. 4, p. 102776, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Yan, M. Chen, P. Hu, D. Li, and Y. Wang, “An analysis on the influence of precipitation infiltration on groundwater under different irrigation conditions in the semi-arid area,” Water Supply, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 1111–1118, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- Yakirevich et al., “Modeling the impact of solute recycling on groundwater salinization under irrigated lands: A study of the Alto Piura aquifer, Peru,” J. Hydrol., vol. 482, pp. 25–39, Mar. 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. Tudi et al., “Effects of drip and flood irrigation on soil heavy metal migration and associated risks in China,” Ecol. Indic., vol. 161, p. 111986, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Pal et al., “Eco-friendly treatment of wastewater and its impact on soil and vegetables using flood and micro-irrigation,” Agric. Water Manag., vol. 275, p. 108025, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wei et al., “Effects of irrigation methods and salinity on CO2 emissions from farmland soil during growth and fallow periods,” Sci. Total Environ., vol. 752, p. 141639, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. M. Jackson, S. Khan, and M. Hafeez, “A comparative analysis of water application and energy consumption at the irrigated field level,” Agric. Water Manag., vol. 97, no. 10, pp. 1477–1485, Oct. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Ward, “Economic impacts on irrigated agriculture of water conservation programs in drought,” J. Hydrol., vol. 508, pp. 114–127, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- K. Hussain et al., “Comparative study of subsurface drip irrigation and flood irrigation systems for quality and yield of sugarcane,” African J. Agric. Res., vol. 5, no. 22, pp. 3026–3034, 2010.

- N. Mupaso, E. Manzungu, J. Mutambara, and B. Hanyani-Mlambo, “THE IMPACT OF IRRIGATION TECHNOLOGY ON THE FINANCIAL AND ECONOMIC PERFORMANCE OF SMALLHOLDER IRRIGATION IN ZIMBABWE,” Irrig. Drain., vol. 63, no. 4, pp. 430–439, Oct. 2014. [CrossRef]

- L. Y. Khor and T. Feike, “Economic sustainability of irrigation practices in arid cotton production,” Water Resour. Econ., vol. 20, pp. 40–52, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Ortega-Reig, C. Sanchis-Ibor, G. Palau-Salvador, M. García-Mollá, and L. Avellá-Reus, “Institutional and management implications of drip irrigation introduction in collective irrigation systems in Spain,” Agric. Water Manag., vol. 187, pp. 164–172, Jun. 2017. [CrossRef]

- C. Perry, “Accounting for water use: Terminology and implications for saving water and increasing production,” Agric. Water Manag., vol. 98, no. 12, pp. 1840–1846, Oct. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Carlson et al., “Intensive irrigation buffers groundwater declines in key European breadbasket,” Nat. Water, 2025. [CrossRef]

- C. Vallet-Coulomb et al., “Irrigation return flows in a mediterranean aquifer inferred from combined chloride and stable isotopes mass balances,” Appl. Geochemistry, vol. 86, pp. 92–104, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- C. D. Pérez-Blanco and F. Sapino, “Economic Sustainability of Irrigation-Dependent Ecosystem Services Under Growing Water Scarcity. Insights From the Reno River in Italy,” Water Resour. Res., vol. 58, no. 2, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Owens et al., “Delivering global water security: Embedding water justice as a response to increased irrigation efficiency,” WIREs Water, vol. 9, no. 6, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. D. Pérez-Blanco, A. Loch, F. Ward, C. Perry, and D. Adamson, “Agricultural water saving through technologies: a zombie idea,” Environ. Res. Lett., vol. 16, no. 11, p. 114032, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Playán and L. Mateos, “Modernization and optimization of irrigation systems to increase water productivity,” Agric. Water Manag., vol. 80, no. 1–3, pp. 100–116, Feb. 2006. [CrossRef]

- S. van der Kooij, M. Zwarteveen, H. Boesveld, and M. Kuper, “The efficiency of drip irrigation unpacked,” Agric. Water Manag., vol. 123, pp. 103–110, May 2013. [CrossRef]

- C. N. Morrisett, R. W. Van Kirk, L. O. Bernier, A. L. Holt, C. B. Perel, and S. E. Null, “The irrigation efficiency trap: rational farm-scale decisions can lead to poor hydrologic outcomes at the basin scale,” Front. Environ. Sci., vol. 11, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Daccache, J. S. Ciurana, J. A. Rodriguez Diaz, and J. W. Knox, “Water and energy footprint of irrigated agriculture in the Mediterranean region,” Environ. Res. Lett., vol. 9, no. 12, p. 124014, Dec. 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. Qin, W. Duan, S. Zou, Y. Chen, W. Huang, and L. Rosa, “Global energy use and carbon emissions from irrigated agriculture,” Nat. Commun., vol. 15, no. 1, p. 3084, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- CBD, “Annex A to COP 5 Decision V/6. Ecosystem Approach; Convention on Biological Diversity,” Montreal,QC, Canada, 2000.

- Hoff, “Understanding the Nexus. Background Paper for the Bonn2011 Conference: The Water, Energy and Food Security Nexus.,” Stockholm, 2011.

- C. Ringler, A. Bhaduri, and R. Lawford, “The nexus across water, energy, land and food (WELF): potential for improved resource use efficiency?,” Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain., vol. 5, no. 6, pp. 617–624, Dec. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Union for the Mediterranean, “UFM Water Policy Framework for Actions 2030,” 2020.

- Lucca et al., “A review of water-energy-food-ecosystems Nexus research in the Mediterranean: evolution, gaps and applications,” Environ. Res. Lett., vol. 18, no. 8, p. 083001, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- U. N. H.-L. P. on W. H.-L. P. on W. UN, “Making Every Drop Count-An Agenda for Water Action,” HLPWater Outcome Rep., no. March, p. 234, 2018.

- P. Mennig, “A never-ending story of reforms: on the wicked nature of the Common Agricultural Policy,” npj Sustain. Agric., vol. 2, no. 1, p. 20, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Brinegar and F. A. Ward, “Basin impacts of irrigation water conservation policy,” Ecol. Econ., vol. 69, no. 2, pp. 414–426, Dec. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Molle and O. Tanouti, “Squaring the circle: Agricultural intensification vs. water conservation in Morocco,” Agric. Water Manag., vol. 192, pp. 170–179, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- P. Hellegers, B. Davidson, J. Russ, and P. Waalewijn, “Irrigation subsidies and their externalities,” Agric. Water Manag., vol. 260, p. 107284, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. D. Pérez-Blanco, A. Hrast-Essenfelder, and C. Perry, “Irrigation Technology and Water Conservation: A Review of the Theory and Evidence,” Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 216–239, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Berbel and L. Mateos, “Does investment in irrigation technology necessarily generate rebound effects? A simulation analysis based on an agro-economic model,” Agric. Syst., vol. 128, pp. 25–34, Jun. 2014. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).