1. Introduction

Ocular trauma represents an important public health issue and a serious clinical challenge. According to the World Health Organization, more than 55 million eye injuries occur worldwide each year, of which 1.6 million result in permanent blindness, while 19 million lead to varying degrees of irreversible visual impairment [

1]. Epidemiological data indicate that ocular trauma is one of the leading causes of unilateral vision loss among working-age adults [

2]. In developed countries, ocular injuries account for approximately 5% of all cases of blindness, whereas in developing countries the incidence is even higher due to limited access to specialized ophthalmic care [

3].

Two main categories of ocular trauma are distinguished: open- and closed-globe injuries. Open-globe injuries include perforations, penetrating wounds, and intraocular foreign bodies, whereas closed-globe (blunt) trauma leads to intraocular mechanical damage while preserving the integrity of the ocular wall [

4]. Blunt trauma results in a sudden rise in intraocular pressure, causing posterior segment damage such as vitreous hemorrhage, macular injury, retinal tears, or retinal detachment [

5].

Vitreous hemorrhage is one of the most common and vision-threatening post-traumatic complications. It can obscure fundus evaluation and mask additional damage, such as retinal breaks or proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR) [

6]. In many cases, initial management involves conservative observation, as some hemorrhages may undergo spontaneous resorption. However, persistent hemorrhage, tractional changes, or the presence of additional complications constitute indications for surgical management, typically pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) [

6,

7].

The timing of surgical intervention after trauma is considered a crucial prognostic factor. Both experimental and clinical studies have demonstrated that hemoglobin degradation products, particularly free iron ions, exert marked cytotoxic effects on the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and photoreceptors [

8]. Irreversible morphological alterations may occur after only 24–48 hours of subretinal blood exposure, and after one week progressive photoreceptor degeneration is observed [

9,

10]. Consequently, most authors recommend early evacuation of hemorrhagic masses within the first 7–14 days after trauma [

11,

12].

Surgical techniques employed in the treatment of post-traumatic hemorrhages and retinal detachments include PPV, often combined with internal limiting membrane (ILM) peeling, endolaser photocoagulation, and tamponade with gas or silicone oil [

13,

14,

15]. The choice of technique depends on the anatomic characteristics of the lesions, the interval since trauma, and the functional prognosis. Reports indicate that outcomes may be favorable in cases of post-traumatic macular holes and giant retinal tears, particularly when comprehensive surgical techniques are applied [

16,

17]. Lema and Lin analyzed prognostic factors of visual acuity following surgery for open-globe injuries with retinal detachment, taking into account surgical timing, the presence of hemorrhage, and tamponade choice [

12]. Ulianova et al. showed that even in blast injuries with posterior pole involvement, vitrectomy combined with chorioretinectomy may yield satisfactory outcomes [

13].

Nevertheless, a proportion of patients with severe ocular injuries with baseline vision limited to light perception or hand movements, are often not considered for surgery due to a poor prognosis [

18]. However, lack of intervention in such cases usually results in progressive retinal degeneration and complete loss of vision. Recent evidence suggests that even in eyes with seemingly hopeless anatomic conditions, staged vitreoretinal surgery may achieve both anatomical and functional improvement [

19,

20].

The long-term consequences of ocular trauma extend beyond the immediate structural damage and often involve complex secondary processes within the posterior segment. Blood degradation products and inflammatory mediators promote fibrocellular membrane formation, progressive scarring, and tractional changes, often leading to proliferative vitreoretinopathy. The severity of these alterations depends not only on the type and extent of the initial injury but also on patient-related factors such as age, systemic health, and regenerative capacity of retinal tissues. Younger individuals generally exhibit a greater potential for recovery, whereas older patients or those with comorbidities are more prone to chronic complications and irreversible vision loss. Moreover, the topography of trauma plays a critical role: injuries involving the posterior pole carry a particularly poor prognosis, while peripheral lesions may allow for partial functional preservation. These multifactorial aspects underscore the heterogeneity of outcomes in ocular trauma and highlight the importance of individualized evaluation in every case [

18,

19,

20,

21].

Of particular interest are the differences between post-traumatic hemorrhages and those associated with chronic diseases such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD) or diabetic retinopathy. Despite their dramatic clinical appearance, post-traumatic hemorrhages may show greater regenerative potential of the retina, especially in younger patients without systemic comorbidities [

21,

22].

The aim of this study is to present a unique case of a patient in whom surgical treatment was initiated 15 years after trauma. Despite highly unfavorable baseline factors, including chronic subretinal hemorrhage and extensive post-traumatic changes, significant improvement in functional vision was achieved. This case contributes to the discussion on patient selection for vitreoretinal surgery and emphasizes that the time interval since trauma should not be considered an absolute disqualifying factor.

2. Case Presentation

A 55-year-old male was referred to the Department of Ophthalmology, University Clinical Center in Katowice, for a routine ophthalmic examination. During the visit, he reported a blunt trauma to the right eye that had occurred 15 years earlier. The injury was sustained during daily activities as a result of accidental finger trauma by a child. Immediately after the event, the patient noticed a sudden, profound deterioration of vision in the affected eye. Visual function was reduced to hand motion perception with light perception and correct light projection (2.0 logMAR, ~0.01 decimal).

2.1. Functioning Prior to Treatment

Since the injury, the patient had functioned essentially monocularly. The left eye remained fully functional, with visual acuity of 1.0 (0.0 logMAR), enabling daily activities and continuation of occupational duties. However, the patient reported:

difficulties in depth perception and spatial awareness,

impairments in tasks requiring precise binocular coordination (e.g., manual work, cycling),

recurrent headaches related to overuse of the left eye,

inability to continue his previous profession, which required good stereoscopic vision (he had previously worked as an assembler).

Although the patient adapted to monocular functioning, he reported a significant reduction in quality of life.

2.2. Baseline Examination

Ophthalmic examination of the right eye revealed:

Anterior segment – inferior corneal scar, partial post-traumatic sectoral cataract,

Vitreous – presence of dense, chronic hemorrhagic remnants,

Retina – multiple intraretinal hemorrhages, signs of post-traumatic retinopathy.

Imaging studies:

Optical coherence tomography (OCT): thinning of the outer retinal layers in the macula, presence of submacular blood remnants, disrupted photoreceptor architecture, and discontinuity of the IS/OS junction; vitreomacular tractional changes within the inner retinal layers.

B-scan ultrasonography: dense echogenic material corresponding to vitreous hemorrhage, irregular and undulating retinal attachment in the posterior pole suggestive of tractional component.

Fluorescein angiography (FA): leakage from perifoveal vessels, areas of hypofluorescence corresponding to blood clots, and hyperfluorescent foci consistent with scarring.

The left eye remained entirely healthy, with normal OCT and FA findings, confirming compensatory monocular functioning, with distance visual acuity of 0.0 logMAR (1.0 Snellen).

2.3. Therapeutic Decision

Due to the absence of hemorrhage resorption and suspicion of complex vitreoretinal pathology, the patient was scheduled for planned staged vitreoretinal surgery. Between May and November 2024, three surgical procedures were performed on the right eye, with techniques tailored to the evolving clinical situation.

Surgical Interventions

🔹 First surgery – 23 May 2024

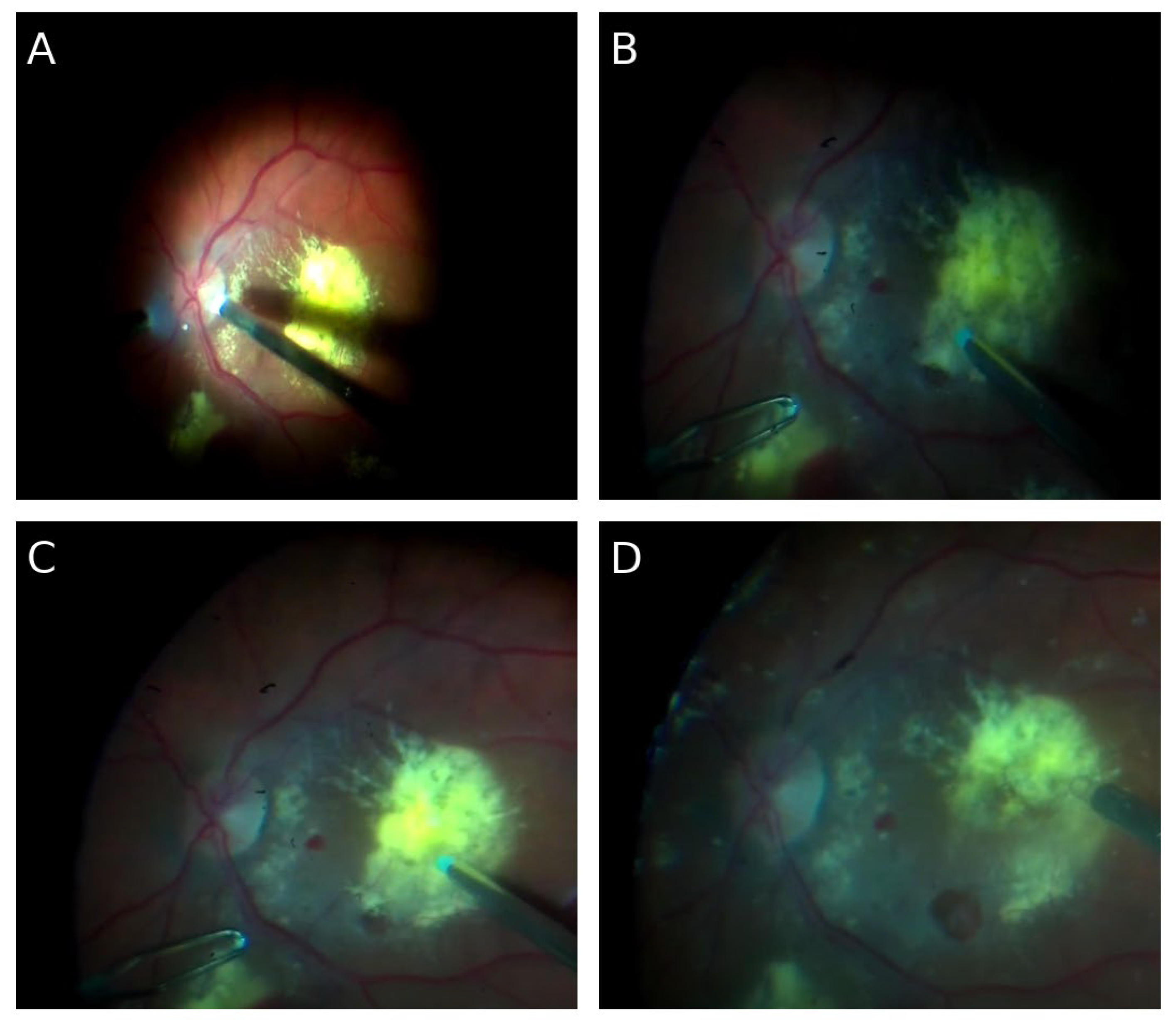

Pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) was performed. Internal limiting membrane (ILM) peeling in the macular area, aspiration of chronic submacular hemorrhagic remnants, and focal endophotocoagulation of the retina were carried out. A 25% SF₆ gas tamponade was applied. The intraoperative image of the vitreous chamber and the fundus of the eye is shown in

Figure 1

Postoperative course: Two weeks postoperatively, partial improvement in visual axis clarity was achieved, although functional acuity remained low (object recognition, but no reading improvement). OCT showed partial clearance of the submacular space and limited re-approximation of photoreceptor architecture.

🔹 Second surgery – 1 August 2024

At follow-up, B-scan ultrasonography revealed retinal detachment with a macular tear. Repeat PPV with perfluorocarbon liquid (perfluorodecalin), extended retinal endolaser photocoagulation, and cataract extraction with intraocular lens implantation (RayOne Aspheric +23.5 D) were performed. Tamponade with 1000 cSt silicone oil was applied. The procedure resulted in complete retinal reattachment.

After three months of stability, silicone oil removal was performed with final tampo- nade using 25% SF₆ gas. The procedure was uneventful.

Perioperative and Pharmacological Management

Standard postoperative pharmacological treatment included topical dexamethasone (6×/day), levofloxacin (Oftaquix, 6×/day), topical hyperosmotic anti-edematous eye drops (Cornesin 3×/day) to reduce corneal edema, and systemic dexamethasone (Dexaven 8 mg/day during hospitalization). Thromboprophylaxis was provided according to internal medicine recommendations (enoxaparin sodium, Clexane 40 mg s.c. once daily).

2.4. Final Outcome and Long-Term Follow-Up

Seven months after the first surgery:

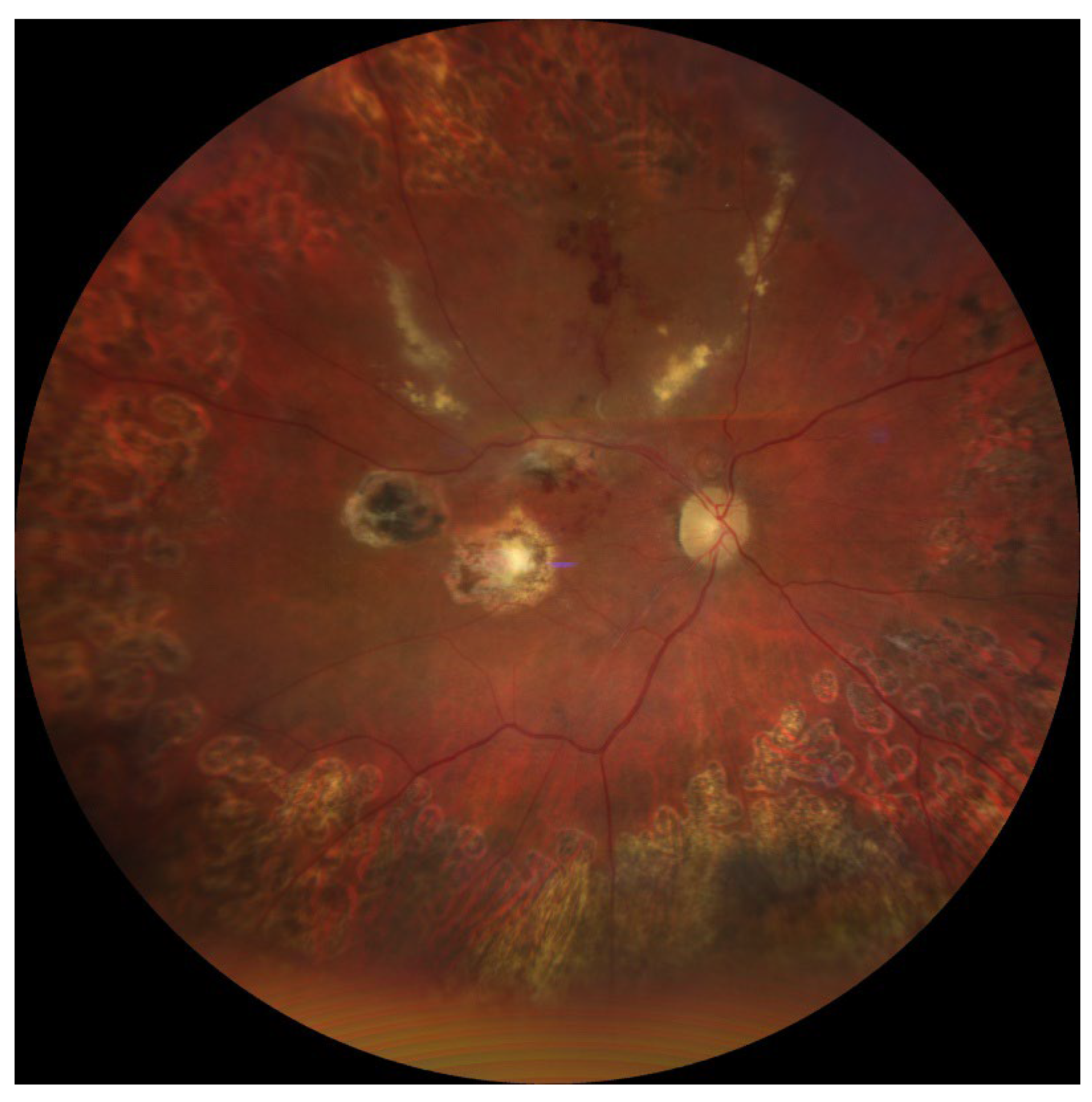

Right eye visual acuity – 0.3 Snellen (0.52 logMAR),

OCT – complete macular reattachment, thinning of photoreceptor layers, no active hemorrhage,

B-scan – no traction, no retinal detachment,

FA – no active leakage.

The postoperative image of the patient’s ocular fundus after completion of treatment is shown in

Figure 2.

Final Effect

Following completion of surgical treatment and recovery, final right eye visual acuity was 0.3 Snellen (0.5 logMAR), representing a marked improvement compared to baseline (hand motion perception only, 2.0 logMAR). This provided the patient with a functionally and socially meaningful level of vision.

2.5. Case Summary

A patient who had functioned monocularly for 15 years regained functional visual acuity in the traumatized eye through staged vitreoretinal surgery. This case demonstrates that, even after a long interval following trauma, surgical intervention may restore anatomic retinal integrity and lead to visual improvement.

4. Discussion

4.1. Pathophysiology of Subretinal and Vitreous Hemorrhage

Extravasation of blood into intraocular spaces, particularly the vitreous cavity and subretinal space, represents one of the most destructive sequelae of ocular trauma. While vitreous hemorrhage may in some cases resolve spontaneously or regress with conservative management, intra-, sub-, and preretinal hemorrhages are associated with a significantly poorer prognosis [

3,

14,

15,

16]. The toxic mechanisms of intraocular blood include:

Experimental studies have shown that photoreceptor degeneration begins as early as 24–48 hours after exposure [

20]. In the following days, irreversible morphological alterations occur, and within weeks, RPE atrophy and complete macular disintegration ensue [

21]. The absence of physiological drainage of subretinal blood further enhances toxicity, leading to irreversible macular damage [

19,

21]. For this reason, most authors advocate early surgical evacuation of subretinal blood [

22]. Prognosis also depends on the hemorrhage location. Comparative studies have demonstrated that subretinal hemorrhage carries a far worse prognosis than intraretinal hemorrhage, mainly due to the direct contact of hemoglobin breakdown products with outer photoreceptors and RPE cells [

22,

23]. Although intraretinal hemorrhage may also compromise retinal function through mechanical compression and localized ischemia, it usually does not cause such rapid and irreversible photoreceptor degeneration as subretinal hemorrhage [

24].

4.2. The Role of Exposure Time

The literature emphasizes the critical role of time from trauma to surgical intervention. The best outcomes are achieved when treatment is initiated within the first days to weeks [

23]. The critical period is generally considered to be 7–14 days, after which the chance of functional macular recovery declines dramatically [

24].

In this context, the present case is exceptional: intervention was undertaken 15 years after trauma. According to current knowledge, such prolonged subretinal blood exposure should irreversibly damage retinal receptor elements. The partial “resilience” of the patient’s retina to the toxic effects of chronic hemorrhage was therefore surprising. The final visual acuity achieved not only challenges expectations but also raises questions about whether timing should be regarded as an absolute contraindication to vitreoretinal surgery.

In this case, functional improvement suggests that:

Biochemical transformation of blood remnants – in the subretinal space, which lacks an active phagocytic system, hemoglobin breakdown products may gradually transform into less reactive forms (e.g., hemosiderin, ferritin) [

25]. In the present case, after more than a decade, primary hemoglobin toxicity may have subsided, leaving less harmful deposits.

Patient-related factors – at the time of trauma, the patient was approximately 40 years old (relatively young), which may have supported partial functional reserve and neuronal plasticity, enhancing the potential for retinal reorganization [

26].

Absence of systemic comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, hypertension) limited additional damaging influences and may have preserved regenerative capacity [

27].

4.3. Comparison with the Literature

Reports of delayed surgical interventions in such cases are scarce.

Chen et al. [

10] described massive subretinal hemorrhages where early PPV combined with tPA led to recovery of visual acuity up to 0.4 Snellen; however, interventions were performed within days to weeks, not years.

Chauhan et al. [

22] presented cases of chronic retinal detachment treated surgically after several months, with moderate but superior outcomes compared to no intervention.

Wu et al. [

9] demonstrated that early surgical intervention in closed-globe injuries with massive vitreous hemorrhage reduces the risk of PVR and improves retinal survival.

Lema and Lin [

12] identified surgical timing as a key prognostic factor in open-globe injuries with retinal detachment.

Against this background, the present case is highly unusual—functional improvement was achieved despite an extraordinarily long interval since trauma.

The etiology of retinal hemorrhage plays a crucial prognostic role. Hemorrhages may arise from neovascular complications (e.g., AMD), systemic diseases (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, coagulopathy), or acute trauma. Several studies indicate that trauma-related hemorrhages, despite their dramatic clinical course, may yield relatively better functional outcomes in selected patients if retinal anatomy remains partially preserved [

28]. Retinal regenerative mechanisms are more effective in younger patients with isolated trauma than in older patients with chronic vascular or metabolic disease [

29].

In contrast, spontaneous subretinal hemorrhages, particularly those related to AMD or choroidopathy, tend to spread and rapidly damage the RPE and photoreceptors, with limited regenerative potential due to underlying degenerative changes [

30]. Similarly, in systemic diseases such as hypertension or coagulation disorders, systemic factors—microangiopathy, impaired retinal perfusion, and altered inflammatory responses—further worsen outcomes [

31].

In the present case, the hemorrhage resulted from a single blunt injury in a patient without systemic comorbidities, likely allowing residual retinal function to persist despite prolonged exposure to hemorrhagic material. This may explain the unexpectedly favorable functional response to surgery, despite a theoretically poor anatomical baseline. Notably, OCT evaluation revealed preserved retinal architecture in certain layers, which encouraged the surgical attempt to remove hemorrhagic products displacing the macula.

4.4. Surgical Strategies and Choice of Tamponade

Various surgical approaches are used in post-traumatic hemorrhage and retinal detachment. Key elements include:

Pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) – removal of hemorrhagic remnants,

ILM peeling – reducing traction and promoting retinal integration,

Endolaser photocoagulation – securing retinal tears and degenerative foci,

Gas tamponade (SF₆, C₃F₈) – applied in localized cases, providing temporary retinal apposition,

Silicone oil tamponade – preferred in complex detachments with high recurrence risk [

28,

29].

In this case, both tamponade methods were required. Initial gas tamponade was insufficient, and silicone oil was necessary for durable reattachment. This raises the question of whether silicone oil should be considered as a primary tamponade in long-standing submacular hemorrhages with macular involvement and posterior retinal tears. Currently, no consensus exists regarding tamponade choice in traumatic cases; decisions should be individualized, depending on lesion morphology and feasibility of stable retinal reattachment [

32,

33,

34,

35].

4.5. Visual Rehabilitation

Visual rehabilitation is a critical aspect of post-traumatic sequelae. Patients who have functioned monocularly for years often experience difficulty readapting to binocular vision once partial function is regained. Rehabilitation strategies include:

The final improvement—visual acuity from 2.0 logMAR to 0.52 logMAR—was not only surprising but also clinically meaningful. Previous studies have shown that retinal exposure to blood breakdown products longer than 7–14 days significantly reduces the chance of macular functional recovery [

16,

17,

21]. In this patient, partial functional reserve and preserved photoreceptor structures may have enabled positive response to surgery once the toxic factor was eliminated. Although functional vision was restored, stereoscopic vision remained limited.

4.6. Clinical and Research Implications

This case raises several practical and scientific questions:

Should surgical eligibility criteria be more liberal? Traditionally, patients with long-standing hemorrhage were disqualified. This case suggests reconsideration, even after years.

What mechanisms underlie preservation of partial retinal functional reserve? Histopathological and experimental studies are needed to clarify the effects of chronic intraocular blood.

What tamponade is optimal in chronic cases? The lack of consensus highlights the need for prospective studies.

Can visual rehabilitation protocols be developed for patients with late visual recovery?

4.7. Discussion Summary

This case represents a unique example of late, staged surgical intervention resulting in functional visual improvement. It demonstrates that:

time since trauma should not always be considered an absolute contraindication,

individualized evaluation of retinal morphology (OCT, ultrasonography, FA) is essential,

even patients with chronic post-traumatic changes may benefit from vitreoretinal surgery.

5. Conclusions

The presented case constitutes a unique example of successful surgical management of chronic post-traumatic complications of the posterior segment, performed as late as 15 years after the initial injury. Despite highly unfavorable baseline factors—long-standing subretinal hemorrhage, the presence of scar tissue, and minimal initial visual acuity—functional improvement was achieved, with vision restored to 0.3 Snellen (0.52 logMAR).

The implications of this case are multifaceted. First, surgical disqualification should not be based solely on the elapsed time since trauma. Careful morphological evaluation using multimodal imaging (OCT, ultrasonography, fluorescein angiography) may reveal preserved functional reserve even in chronic cases. Second, a staged and flexible surgical approach—combining PPV, ILM peeling, endolaser photocoagulation, and different tamponade agents—can provide a stable anatomical outcome. Third, individual patient-related factors, such as younger age at the time of trauma and absence of systemic comorbidities, may support retinal regenerative potential.

From a clinical perspective, this case suggests that, in the era of advanced vitreoretinal surgery, even patients with chronic, long-untreated post-traumatic complications should not be automatically excluded from surgical consideration. Eligibility should be determined not only by statistical prognosis but also by weighing potential individual benefits. Further research—both observational and experimental—is required to better understand the mechanisms underlying retinal function preservation after prolonged blood exposure and to develop optimal treatment and rehabilitation strategies in similar scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: W.L. Formal analysis: W.L. and W.R. Investigation: W.L., M.L. and W.R. Surgery: W.R. Resources: W.L. and W.R. Data curation: W.L. and M.L. Writing—original draft preparation: W.L. Writing—review and editing: W.L., M.L. and W.R. Visualization: W.L. and W.R. Supervision: W.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FA |

Fluorescein angiography |

| ILM |

Internal limiting membrane |

| OCT |

Optical coherence tomography |

| PPV |

Pars plana vitrectomy |

| PVR |

Proliferative vitreoretinopathy |

| RPE |

Retinal pigment epithelium |

| ROS |

Reactive oxygen species |

| SF6

|

Sulfur hexafluoride (gas tamponade) |

References

- Waters, T.; Vollmer, L.; Sowka, J. Proliferative vitreoretinopathy as a late complication of blunt ocular trauma. Optometry 2008, 79, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busquets, M.A.; Kim, A.; Busquets, T. Bilateral Giant Retinal Tears Associated with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Ophthalmol Retina 2023, 7, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, X.; Xu, S.; Song, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, B.; Zhong, Y.; Liu, L.; Hu, Y. Global, national and regional prevalence, and associated factors of ocular trauma: A protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020, 99, e21870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dogramaci, M.; Erdur, S.K.; Senturk, F. Standardized Classification of Mechanical Ocular Injuries: Efficacy and Shortfalls. Beyoglu Eye J. 2021, 6, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadde, S.G.K.; Snehith, R.; Jayadev, C.; Poornachandra, B.; Naik, N.K.; Yadav, N.K. Macular tractional retinal detachment: A rare complication of blunt trauma. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020, 68, 2602–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lin, Y.C.; Wang, C.T.; Chen, K.J.; Chou, H.D. Traumatic terson syndrome with a peculiar mass lesion and tractional retinal detachment: a case report. BMC Ophthalmol. 2024, 24, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, Z.G.; Li, P.; Yang, X.M.; Wang, Z.Q.; Zhang, P.R. High BMI, silicone oil tamponade, and recurrent vitreous hemorrhage predict poor visual outcomes after pars plana vitrectomy in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. BMC Ophthalmol. 2025, 25, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Agrawal, R.; Shah, M.; Mireskandari, K. Controversies in ocular trauma classification and management. Int Ophthalmol. 2013, 33, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeung, L.; Chen, T.L.; Kuo, Y.H.; Chao, A.N.; Wu, W.C.; Chen, K.J.; Hwang, Y.S.; Chen, Y.; Lai, C.C. Severe vitreous hemorrhage associated with closed-globe injury. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006, 244, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.J.; Sun, M.H.; Sun, C.C.; Wang, N.K.; Hou, C.H.; Wu, A.L.; Wu, W.C.; Lai, C.C. Traumatic Maculopathy with Massive Subretinal Hemorrhage after Closed-Globe Injuries: Associated Findings, Management, and Visual Outcomes. Ophthalmol Retina 2019, 3, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quiroz-Reyes, M.A.; Quiroz-Gonzalez, E.A.; Quiroz-Gonzalez, M.A.; Lima-Gómez, V. Early versus Delayed Vitrectomy for Open Globe Injuries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Ophthalmol. 2024, 18, 1889–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lema, G.M.C.; Lin, H.; Yoganathan, P. Prognostic indicators of visual acuity after open-globe injury and retinal detachment repair. Retina 2016, 36, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulianova, N.; Sidak-Petretska, O.; Bondar, N. Outcomes of vitrectomy for blast-related trauma with chorioretinitis sclopetaria. Int J Retina Vitreous 2025, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabłoński, M.; Winiarczyk, M.; Biela, K.; Bieliński, P.; Jasielska, M.; Batalia, J.; Mackiewicz, J. Open Globe Injury (OGI) with a Presence of an Intraocular Foreign Body (IOFB)-Epidemiology, Management, and Risk Factors in Long Term Follow-Up. J Clin Med. 2022, 12, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lee, S.; Kim, J. Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment with Giant Retinal Tear: Case Series and Literature Review. J Clin Med. 2024, 13, 4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Glatt, H.; Machemer, R. Experimental subretinal hemorrhage in rabbits. Am J Ophthalmol. 1982, 94, 762–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hope, G.M.; Dawson, W.W.; Engel, H.M. Subretinal blood induces retinal degeneration in cats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992, 33, 2894–2901. [Google Scholar]

- Toth CA, Morse LS, Hjelmeland LM, Landers MB 3rd. Fibrin directs early retinal damage after experimental subretinal hemorrhage. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991, 109, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Znaor, L.; Medic, A.; Binder, S.; Vucinovic, A.; Marin Lovric, J.; Puljak, L. Pars plana vitrectomy versus scleral buckling for repairing simple rhegmatogenous retinal detachments. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019, 3, CD009562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Al-Zaaidi, S.; Al-Abdullah, A.; Al-Amri, A. Silicone oil tamponade in complicated retinal detachment: indications and outcomes. Clin Ophthalmol. 2019, 13, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, D.R.P.; Khan, M.S.; Engelbert, M.; Kapusta, M.A.; Chow, D.R. Timing of surgery for traumatic macular holes and associated retinal detachment: visual outcomes. Retina 2017, 37, 1071–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, D.; Ghosh, B.; Kumar, A. Late surgical management of chronic post-traumatic retinal detachment: clinical outcomes. Eye (Lond) 2022, 36, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.M.; Steel, D.H. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor for prevention of postoperative vitreous cavity haemorrhage after vitrectomy for proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015, 2015, CD008214, Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023 May 31;5:CD008214. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008214.pub4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shaikh, N.; Srishti, R.; Khanum, A.; Thirumalesh, M.B.; Dave, V.; Arora, A.; Bansal, R.; Surve, A.; Azad, S.; Kumar, V. Vitreous hemorrhage - Causes, diagnosis, and management. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2023, 71, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Picard, E.; Daruich, A.; Youale, J.; Courtois, Y.; Behar-Cohen, F. From Rust to Quantum Biology: The Role of Iron in Retina Physiopathology. Cells 2020, 9, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Di Fazio, N.; Delogu, G.; Morena, D.; Cipolloni, L.; Scopetti, M.; Mazzilli, S.; Frati, P.; Fineschi, V. New Insights into the Diagnosis and Age Determination of Retinal Hemorrhages from Abusive Head Trauma: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics (Basel) 2023, 13, 1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Colcombe, J.; Mundae, R.; Kaiser, A.; Bijon, J.; Modi, Y. Retinal Findings and Cardiovascular Risk: Prognostic Conditions, Novel Biomarkers, and Emerging Image Analysis Techniques. J Pers Med. 2023, 13, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mayer, C.S.; Reznicek, L.; Baur, I.D.; Khoramnia, R. Open Globe Injuries: Classifications and Prognostic Factors for Functional Outcome. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021, 11, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cui, X.; Buonfiglio, F.; Pfeiffer, N.; Gericke, A. Aging in Ocular Blood Vessels: Molecular Insights and the Role of Oxidative Stress. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Confalonieri, F.; Ferraro, V.; Barone, G.; Di Maria, A.; Petrovski, B.É.; Vallejo Garcia, J.L.; Randazzo, A.; Vinciguerra, P.; Lumi, X.; Petrovski, G. Outcomes in the Treatment of Subretinal Macular Hemorrhage Secondary to Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Systematic Review. J Clin Med. 2024, 13, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lendzioszek, M.; Bryl, A.; Poppe, E.; Zorena, K.; Mrugacz, M. Retinal Vein Occlusion-Background Knowledge and Foreground Knowledge Prospects-A Review. J Clin Med. 2024, 13, 3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tripepi, D.; Jalil, A.; Ally, N.; Buzzi, M.; Moussa, G.; Rothschild, P.R.; Rossi, T.; Ferrara, M.; Romano, M.R. The Role of Subretinal Injection in Ophthalmic Surgery: Therapeutic Agent Delivery and Other Indications. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 10535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Siwik, P.; Chudoba, T.; Cisiecki, S. Retinal Displacement Following Vitrectomy for Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment: A Systematic Review of Surgical Techniques, Tamponade Agents, and Outcomes. J Clin Med. 2025, 14, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Confalonieri, F.; Josifovska, N.; Boix-Lemonche, G.; Stene-Johansen, I.; Bragadottir, R.; Lumi, X.; Petrovski, G. Vitreous Substitutes from Bench to the Operating Room in a Translational Approach: Review and Future Endeavors in Vitreoretinal Surgery. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shettigar, M.P.; Dave, V.P.; Chou, H.D.; Fung, A.; Iguban, E.; March de Ribot, F.; Zabala, C.; Hsieh, Y.T.; Lalwani, G. Vitreous substitutes and tamponades - A review of types, applications, and future directions. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2024, 72, 1102–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).