1. Introduction

Solid tumors are spatially and temporally heterogeneous: invasive rims, acidic or hypoxic cores, and distal niches differ in chemistry, pressure, and protease activity (e.g., MT1-MMP and cysteine cathepsins), challenging “always-on” biologics to balance efficacy and safety. Three maturing technology streams motivate a local, mechanism-coupled strategy: protease-activated antibodies, mildly acidic (near-neutral-to-physiology) pH-gated antibodies, and intratumoral/peritumoral hydrogels that regionalize exposure with practical handling [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Orthogonal “double-locked” activatable concepts (e.g., programmable bivalent peptide–DNA locks) have also been explored [

12], but our focus here is a single-construct, locally constrained design. Our approach proposes encoding both responsivities within one biologic so that local tumor biology triggers activation with operational simplicity and compatibility with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), radiotherapy, and cytotoxics. Activity-based probes (ABPs) and niche-biased imaging (e.g., cathepsin-B positron emission tomography, PET) can pre-map permissive geography and calibrate pH set-points without overfitting [

1]. Starting local-first is a safety choice: the hydrogel limits systemic exposure while the sequential AND gate provides a second containment layer; activation is expected to emerge first at rims (MT1-MMP-high; mildly acidic extracellular pH, typically ~6.5–6.9) [

10,

11].

Status and intent. This is a hypothesis-only conceptual proposal intended to inspire wet-lab testing; no laboratory experiments have been performed to date due to a lack of financial and technical resources. The goal is a minimally complex, testable path that experimental groups can adapt to their indications and infrastructure.

Feasibility notes at concept stage.

(i) Sequential gating. While the AND logic is sound, strict sequential dependency must be demonstrated. A key failure mode is partial Fc exposure at pH ~7.4 immediately after protease cleavage. Early in-silico work—histidine-cluster titration around Fc interfaces and molecular dynamics (MD) on post-cleavage conformers—plus exploratory biophysical mapping can de-risk this. No-go criteria: if pre-cleavage Fc readouts exceed 5% at pH 7.4 or if post-cleavage Fc exposure exceeds 5% at pH ≥7.2, designs are iterated or stopped.

(ii) Local delivery and tissue reach. We set a preliminary objective of achieving ~2–4 mm radial tissue reach from a microdepot within 24–48 h. However, extracellular matrix (ECM)-limited transport and interstitial pressure may constrain this; literature values vary across models. Fallbacks include microdepot spacing, gel-erosion tuning, and redosing schedules; alternative depots are considered only if chemistry, manufacturing, and controls (CMC) remain tractable.

(iii) Target antigen selection. A clearly justified lead antigen—rim-biased expression with MT1-MMP context, low agonism risk, robust readouts, and image-guided access—will strengthen first-iteration testing.

Novelty Statement

Unlike systemic probodies or single-trigger designs, we propose coupling two orthogonal triggers (protease → mildly acidic pH) inside one nanobody–Fc and enforcing order-dependence, while constraining pharmacokinetics (PK) via a local hydrogel depot. Safety is treated as a multi-attribute monitoring (MAM)/critical quality attribute (CQA)-anchored property—“mask-intact” fingerprints—rather than a narrative claim. A co-primary “Fc-in-depot only” architecture further decouples binding from effector activation to handle spatial desynchrony—an integration we have not found combined in prior art. Extracellular vesicle (EV) analytics may inform design-time Fc presets as exploratory priors (not bedside steering), with pre-specified thresholds and conservative defaults where discordant [

15,

16,

17].

Table 1.

Concise comparison to representative strategies.

Table 1.

Concise comparison to representative strategies.

| Strategy |

Triggers |

PK localization |

Order-dependence |

Explicit CQAs for safety |

Heterogeneity handling |

| Systemic probodies [2,3,4,5,6] |

Protease only |

Systemic |

No |

Often partial/implicit; formalization varies |

Limited |

| pH-gated antibodies [7,8,9] |

pH only |

Systemic |

No |

Partial |

Limited |

| Local hydrogel + “always-on” Ab [10,11,20] |

None |

Local |

N/A |

Feasible |

Via placement only |

| This work (primary) |

Protease → mildly acidic pH (AND) |

Local hydrogel depot |

Yes |

MAM mask-intact as CQA |

Microdepots + preset variants |

| This work (co-primary) |

Protease binding on-tissue; Fc competence in-depot only |

Local |

Functional order |

Nb–Fc coupling state as CQA |

Desynchrony-tolerant |

2. Core System: Single-Variant Nb-Sub-Fc with Local Hydrogel Delivery

2.1. Construct

A nanobody (single-domain VHH)–Fc against a validated tumor antigen (e.g., programmed death-ligand 1, PD-L1; epidermal growth factor receptor, EGFR; human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, HER2; carbonic anhydrase IX, CAIX; mesothelin) balances translational plausibility and manufacturing familiarity. The substrate mask is biased toward MT1-MMP (rim targeting) and profiled against thrombin, plasmin, and MMP-2/-9; disease-specific variants can follow contemporary substrate/linker discovery [

2,

3,

4,

21,

22,

31]. The pH gate operates in the mildly acidic window (nominally ~6.7; may be re-centered toward ~6.3) consistent with reports on pH-responsive antibodies and tumor extracellular acidity [

7,

8,

9]. Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) and complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) are restored only under full activation (see §3.5).

Lead antigen suggestion. For first-in-animal studies, EGFR in head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma is attractive given clinical benchmarks and image accessibility; CAIX is a strong alternative where acidity coupling is central. Final selection should maximize rim localization, assayability, and safety margin.

Developability and fail-silent design. To minimize sequence liabilities and partial activation, “protease-only” should yield binding-only without effector agonism. Target selection favors antigens with low agonist risk from Fab engagement. Human-derived blocking modules and in-silico de-immunization are preferred to limit neoepitopes; substrate/mask sequences are stress-tested for proteolysis and aggregation liabilities [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

22,

29,

31].

2.2. Logic (Molecular And Gate)

At physiological pH (~7.4) in the depot, the construct is silent.

Signal 1 (protease): a tumor-biased protease (e.g., MT1-MMP or cathepsin B) cleaves the mask and unmasks antigen binding.

Signal 2 (pH): mild acidosis enables Fc effector engagement.

Sequential interlock: steric/allosteric coupling prevents pH-dependent Fc exposure prior to cleavage—only protease then acidic pH yields full activation (truth table §3.5) [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. Achieving strict dependency is non-trivial; engineering levers include histidine-rich pH-switches placed away from the Fc interface until cleavage, and coupling motifs that remain conformationally “locked” at ≥7.2 post-cleavage. Early checkpoint: exclude >5% Fc readout at pH ≥7.2 in any pre-cleavage or immediate post-cleavage state.

2.3. Delivery Mode (Locally Responsive)

An injectable, biodegradable hydrogel placed intra-/peritumorally provides high local concentration, controlled release (days–weeks), and low systemic exposure [

10,

11,

30].

Composition/properties. Ionically cross-linked alginate or chitosan–PEG networks offer biocompatibility and tunable mesh size. Release follows mesh size, crosslink density, swelling, and controlled erosion/degradation; nanocomposite options may enhance stability/transport if CMC remains tractable [

10,

11,

19,

30,

44].

pH stewardship. Hydrogel microenvironments can drift with inflammation or hemorrhage; buffering (e.g., zwitterionic/weak-acid pairs) targets ~6.5–6.7 yet tolerates 6.3–6.9 without premature Fc competence.

Microdepots. Multiple small ring-shaped microdepots at the rim (image-guided placement) reduce path lengths and better cover heterogeneous lesions; transport benchmarks are specified in §4.2.

3. Mechanistic Choices and Assayable Set-Points

3.1. Protease Gate

Panels prioritize MT1-MMP selectivity and quantify signal-to-noise via liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) fragment identification; leakiness is challenged against thrombin, plasmin, MMP-2/-9. For core regions rich in cathepsins, cathepsin-B-biased substrates are candidates for later variants [

2,

3,

4,

21,

22,

32,

45]. Redundancy: evaluate dual MT1-MMP motifs separated by flexible linkers to reduce single-site failure; include negative-control motifs to quantify ectopic cleavage risk.

3.2.pH Gate

Window and matrix effects. Near-neutral-to-physiology masks are tuned to ~6.7 (strict) to ~6.3 (permissive). Assays include physiologic albumin and ionic strength to capture effective pKa shifts and protein–mask interactions [

7,

8,

9]. For cathepsin-dominant niches, re-center the window toward ~5.5–6.5 without changing the protease substrate by modifying the blocking module [

7,

8,

9,

29].

3.3. Fc Engineering

Afucosylation and GASDALIE (G236A/S239D/A330L/I332E) increase FcγRIIIa engagement and ADCC; reduced-effector Fc designs attenuate Fcγ/complement when needed; neutrophil-oriented effects can be leveraged when justified [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. These levers provide a graded potency palette orthogonal to the AND gate and selected per indication and safety margin.

3.4. Imaging & Stratification Before Dosing

ABPs map permissive proteolysis in vivo or ex vivo; cathepsin-B PET offers an orthogonal niche readout. Together they support rim-first deployment and pH-gate tuning without complicating the hydrogel path [

1,

32,

33].

3.4.1. EV-Guided Fc Selection (Design-Time)

Large-EV PD-L1 abundance may justify higher FcγRIIIa-engaging backbones (afucosylated/GASDALIE-like) to favor ADCC where effector access is plausible; EV-VEGF-A enrichment could flag angiogenic niches where neutrophil-biased Fc or complement leverage is hypothesis-generating. Scope: EV signatures are treated strictly as priors—validated against tissue immunoassays—with pre-specified thresholds and inter-assay CVs; in discordance, default to conservative Fc. This is exploratory and not yet a validated selection biomarker [

15,

16,

17].

3.5. AND-Gate Outcomes (Truth Table and Order-Dependence)

Protease– / pH ~7.4: silent.

Protease+ / pH ~7.4: binding-only (Fc masked).

Protease– / mildly acidic pH: silent.

Protease+ / mildly acidic pH: full activation (binding + Fc engagement).

Order of activation (targets).

• Protease → pH: restore ≥80% ADCC/CDC vs. unmasked reference.

• pH → protease: remain ≤5% Fc-effector readout vs. fully activated control (pre-cleavage Fc non-competent), confirming sequential logic [

7,

8,

9,

24,

25,

26].

4. Preclinical Plan

4.1. In Vitro Gating Fidelity

At pH 7.4, the mask should reduce Fcγ-receptor engagement and ADCC by ≥95% vs. unmasked control; confirm by functional assays and MAM fingerprints [

24,

25,

26]. Protease dependence should give ≥50-fold binding gain after MT1-MMP, with specificity verified against thrombin, plasmin, MMP-2/-9 [

2,

3,

4,

21,

22]. Full ADCC/CDC only after protease + pH ~6.7 in the correct order [

7,

8,

9,

24,

25,

26].

4.1.1. Quantitative Feasibility Scaffold (In-Vitro Anchor)

We outline a framework to test a masked nanobody–Fc (Nb–Fc) that remains inactive until tumor-localized activation:

(i) Protease cleavage. A tumor protease (MT1-MMP) removes the mask. Under pseudo-first-order conditions, the cleavage rate is governed by the product of (a) catalytic efficiency (kcat divided by KM) and (b) the effective enzyme concentration (E0). We require that the fraction cleaved reach at least 80% within 1–3 hours under tumor-like conditions (10–100 nM apparent protease, pH 6.7, 37 °C). Experiments should use MT1-MMP catalytic activity in membrane-mimicking or immobilized formats to capture steric access and hydrogel diffusion, with appropriate Zn2+/Ca2+, ionic strength, and TIMP controls.

(ii) pH-dependent Fc activation. After cleavage, Fc effector function follows a sigmoidal (Hill-type) dependence on pH. Parameters are fitted so that Fc activity is at most 5% at pH 7.4 (normal tissue) and at least 80% at pH 6.7 (tumor). Practical ranges that satisfy these targets include an apparent pKa around 6.9–7.0 and a Hill coefficient around 4–5.

(iii) Sequential control (order-locking). Effective Fc activity requires both sufficient cleavage and acidic pH. We enforce a cleavage threshold (“theta,” for example 0.6–0.8 of the mask removed) combined with a steep logistic transition (“beta,” controlling the sharpness). This keeps Fc function off immediately after cleavage at neutral pH and only permits activation once the local environment is sufficiently acidic and the cleavage fraction has surpassed the threshold, reducing off-target risks.

Parameters and gates. The parameters to be estimated are kcat, KM, apparent pKa, Hill coefficient (n), the cleavage threshold (theta), and the steepness parameter (beta). These are obtained from protease assays and tumor-mimicking gels (including Zn2+/Ca2+ and ionic strength controls) and then used to set pass/fail criteria for activation and safety as specified in §3.5/§7.

4.2. Local Delivery In Vivo

Orthotopic or subcutaneous models with MT1-MMP activity and mild acidosis. Arms:

(a) hydrogel + AND-gated Nb-Sub-Fc;

(b) hydrogel + non-cleavable control;

(c) systemic unmasked antibody reference;

(d) optional restricted exploratory arm (non-systemic, image-guided) to boost regional distribution under predefined guardrails.

Endpoints: tumor growth inhibition, immune-effector readouts, and negligible systemic exposure.

Measured tissue reach: radial concentration profiles around multiple microdepots and minimum effective concentration at the rim; prospective benchmark ~2–4 mm at 24–48 h, acknowledging ECM-limited transport—mitigated by depot multiplicity, gel erosion tuning, and re-dosing. Where warranted and CMC remains tractable, alternative depot materials (e.g., in-situ forming poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid, PLGA) depots or thermogels) can be explored as fallbacks [

10,

11,

45].

4.2.1. Model-Guided Transport Benchmarks (Depot → Rim)

To decide how far and how fast the construct travels from the hydrogel depot to the tumor’s invasive rim, we use a simple “diffusion plus erosion” picture. Practically, this reduces to two measurable knobs: an effective diffusivity through porous extracellular matrix (typically on the order of 10−8–10−7 cm2/s for antibody-sized species) and a first-order gel-erosion rate that replenishes drug at the depot surface over time. With these two parameters in hand (fitted from tissue-mimicking phantoms or ex vivo slices), we run a 2-D radial simulation with a conservative “sink” at the rim—meaning local clearance keeps concentrations there low—and ask a design question: does the concentration at the rim stay at or above the minimum needed to trigger Fc-mediated cytotoxicity for 24–48 hours? The answer sets practical rules. The predicted radial “reach” (the distance over which the model keeps the rim above the activation threshold for the target duration) becomes the maximum center-to-center spacing between microdepots; ring layouts are then specified as “place microdepots every [spacing] millimeters” along the circumference, with a modest safety overlap to cover heterogeneity. As a concrete guide, if fitted data suggest a 2–4 mm reach, we would cap center-to-center spacing at about 3–6 mm and still add ~20–30% overlap in challenging tissue.

4.3. Safety Gate

Contraindicated within 14–21 days of major surgery or active inflammatory wounds. Hard-stops: standardized incisional-wound model and ex-vivo human wound-fluid panel; advancement pauses if off-target unmasking exceeds threshold [

39,

40]. Safety rests on local PK + sequential dual gating.

5. Safety and Risk Management

5.1. Why Local Can Be Safer—Even vs. Advanced Systemic Masks

Local hydrogel delivery reduces systemic exposure by construction; the sequential protease→pH logic adds an orthogonal containment layer compared with systemic masked antibodies that may unmask in wounds/inflammation [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

19,

39,

40].

5.2. Heterogeneity and “Protease Deserts”

Detect early with ABPs and cathepsin-B imaging; manage with local multi-microdepot re-injection and, in later iterations, cautiously explore non-systemic spatial tools to enhance regional distribution or to test a minimal Nb–Fc under tight guardrails [

13,

14,

38]. Adoption requires image-accessible lesions, predefined safety parameters, and proof of local PK confinement. Inter-patient variability is anticipated; acceptance ranges are pre-specified for gating metrics and transport fits.

5.3. Developability and Immunogenicity

Mitigate immunogenicity via in-silico de-immunization, ex-vivo human-matrix interrogation (mask integrity in serum; anti-drug antibodies, ADAs), and human-sera screening. Favor humanized nanobodies and human-derived blocking modules [

7,

29,

30,

37]. Consider anti-PEG responses if PEGylated excipients or materials are used and weigh mitigation strategies accordingly [

41,

42]. Design cleavage fragments to be short and clearance-prone. Release controls tie Fc glyco-engineering to FcγRIIIa binding/ADCC to limit lot-to-lot drift [

24,

25,

26].

5.4. Co-Primary or Contingency Design — Hydrogel-Programmed Fc Confinement (Local-Only Effector Activation)

To de-risk desynchrony between protease and pH in heterogeneous rims, we propose a co-primary safety-first architecture that confines full Fc effector competence to the hydrogel while relying on protease-only unmasking of antigen binding on the nanobody in surrounding tissue. Reciprocal implementations:

(A) Depot-programmed coupling. Engineer Nb–Fc association to be stable under the hydrogel’s mildly acidic buffer (~6.5–6.7) yet to decouple rapidly at near-neutral tissue pH (~7.2–7.4). Any off-region leakage becomes binding-only (fail-silent). Candidate chemistries include β-eliminative/self-immolative linkers with predictable tunability [

22,

31].

(B) Protease-only Nb with a pH-responsive Nb–Fc linkage. Use cleavable or reversible pH-sensitive motifs so that Fc competence toggles only after local acidosis—post-protease unmasking—minimizing reliance on strict co-occurrence while preserving spatial containment [

22,

29,

31].

Acceptance criteria: full ADCC/CDC only for {protease+, in-hydrogel}; ≤5–10% Fc-effector readout for {protease+, surrounding tissue/near-neutral}; background otherwise. MAM fingerprints track the Nb–Fc coupling state as a CQA throughout development and release [

35].

6. Clinical Scope and Access

Initial clinical scope targets image-accessible lesions (cutaneous/subcutaneous, head-and-neck, or interventional radiology (IR)-accessible hepatic/pulmonary). Intratumoral/peritumoral placement with multiple small microdepots is standard there. Disseminated micrometastatic disease is out of scope for first-in-human; broader coverage depends on maintained safety margins and maturation of locoregional tools [

10,

11]. Our hypothesis complements, rather than replaces, systemic pathway-directed therapies where appropriate.

7. Scale-Up, Analytics, and Lifecycle (MAM-Anchored)

A single Nb-Sub-Fc backbone simplifies cell-bank qualification and comparability. Multi-attribute monitoring (MAM) anchors identity, post-translational modifications (PTMs), and mask-integrity fingerprints (International Council for Harmonisation, ICH Q14/Q2(R2)); lifecycle management follows FDA/ICH Q12 with pre-specified comparability windows [

43,

44]. Release specs link Fc glyco-engineering (e.g., afucosylation) to FcγRIIIa binding/ADCC; stability-indicating assays monitor higher-order structure and subvisible particles. Targets at release: high molecular weight (HMW) species ≤2% (size-exclusion chromatography with multi-angle light scattering, SEC-MALS), dynamic light scattering (DLS) polydispersity index (PDI) within platform bounds, differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) melting temperature (Tm) within comparability window, leakiness <0.5%/day at pH 7.4/37 °C, MAM “mask-intact” ≥98% [

24,

25,

26,

35]. Upstream proteolysis risks can be limited with complement C1s knockout (KO) CHO cells.

Manufacturability risks (and controls). Yield impact of masking domains, glycoform control under afucosylation, and linker heterogeneity are managed with site-occupancy specifications for mask/linker and Fc glycan profiles; a single-backbone strategy supports comparability per ICH Q12 [

43,

44].

Mask integrity as a CQA. The mask-intact fraction by MAM is designated a release-defining CQA with comparability windows per ICH Q14/Q2(R2) and lifecycle controls under FDA/ICH Q12 [

43,

44]. Secondary CQAs include FcγRIIIa binding across pH (7.4 vs. ~6.3) and ADCC/CDC restoration under dual signals, directly linking analytics to mechanism [

24,

25,

26].

8. Future Perspective: Stage-/Niche-Responsive Ensemble

Expansion depends on sustained safety, robust analytics, and available/mature manufacturing and linker chemistry. A pre-qualified set of variants may be evaluated: substrates matched to niches (MT1-MMP for rims, cathepsin B for hypoxic/acidic cores, urokinase-type plasminogen activator, uPA for metastatic microenvironments) [

19,

21,

22,

23,

45]; Fc-potency gradients (afucosylated/GASDALIE-like vs. reduced-effector; neutrophil-biased immunity when appropriate) [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]; and selection guided by ABPs, protease imaging, and EV analytics at design time rather than bedside steering [

1,

15,

16,

17]. Advancement occurs only if the ensemble outperforms the single-variant local approach in safety margin and heterogeneity coverage at comparable on-target activity [

19,

28].

9. Conclusion

Encoding a protease→mildly acidic pH sequential AND gate within a single Nb–Sub–Fc and constraining exposure via a local hydrogel offers a realistic path to concentrate cytotoxicity at permissive rims while preserving safety, with minimal reliance on the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect. For highly heterogeneous tumors, Hydrogel-Programmed Fc Confinement provides a co-primary route to maintain binding in surrounding tissue while reserving full Fc competence for the hydrogel depot. The first iteration is deliberately simple—measure signal-to-noise rigorously, protect safety margins, and only then evaluate whether a pre-qualified variant set adds value. If this hypothesis holds in early models, the practical upside would likely be improved local control with lower systemic exposure—enabling dose de-escalation, widening eligibility for antibody-based regimens, and creating a credible bridge to combinations (e.g., radiotherapy or ICIs) without materially increasing off-target risk.

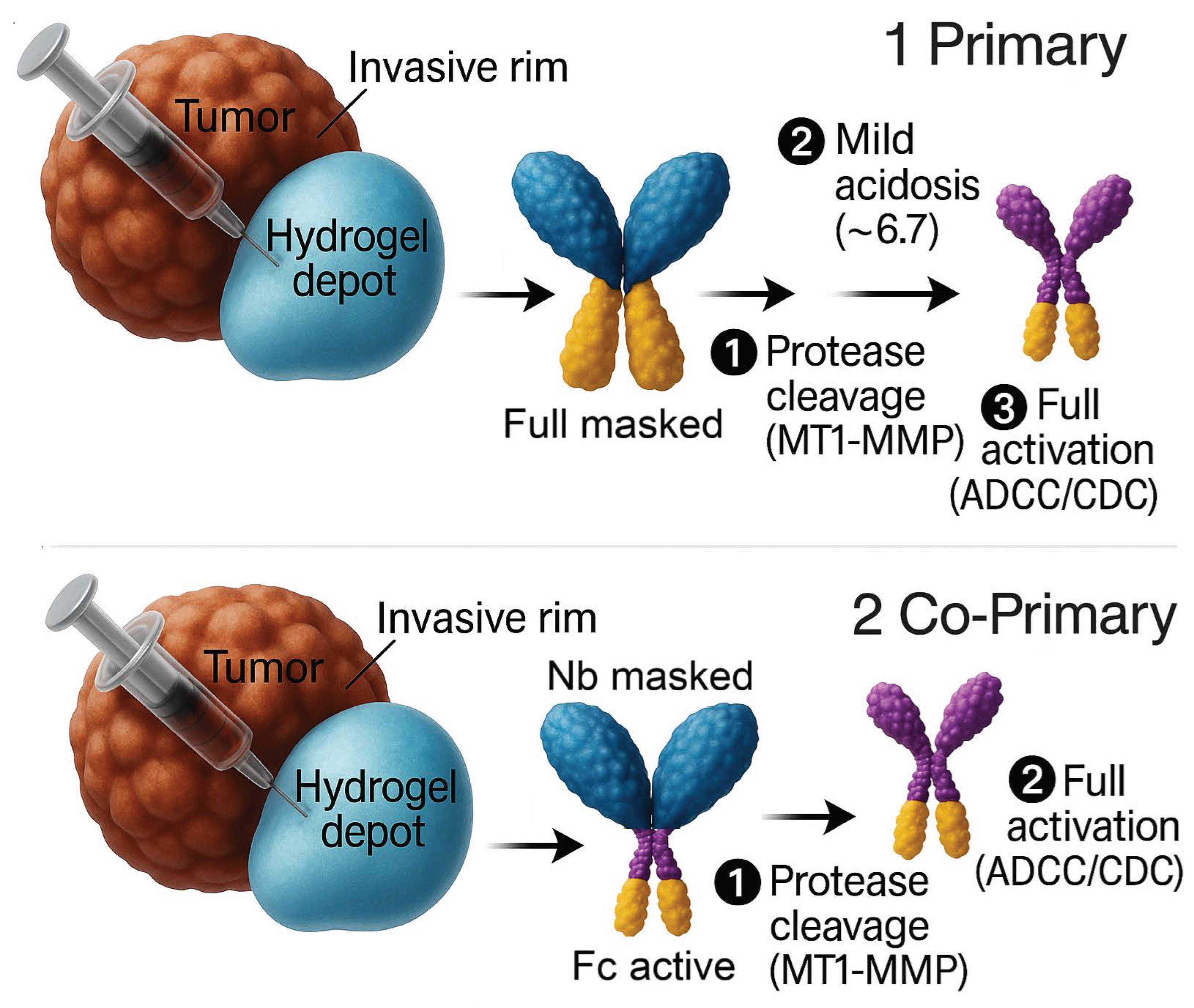

Figure 1.

Local activation designs for Nb–Sub–Fc. Panel 1 (primary): In a hydrogel depot, MT1-MMP cleavage unmasks antigen binding, and mild acidosis (~pH 6.7) enables Fc engagement, focusing ADCC/CDC at the invasive rim. Panel 2 (co-primary): Hydrogel-Programmed Fc Confinement—binding remains protease-dependent, while Fc is constitutively competent but functionally confined to the depot. (Abbrev.: Nb, nanobody; Fc, fragment crystallizable; ADCC/CDC, antibody-/complement-dependent cytotoxicity.).

Figure 1.

Local activation designs for Nb–Sub–Fc. Panel 1 (primary): In a hydrogel depot, MT1-MMP cleavage unmasks antigen binding, and mild acidosis (~pH 6.7) enables Fc engagement, focusing ADCC/CDC at the invasive rim. Panel 2 (co-primary): Hydrogel-Programmed Fc Confinement—binding remains protease-dependent, while Fc is constitutively competent but functionally confined to the depot. (Abbrev.: Nb, nanobody; Fc, fragment crystallizable; ADCC/CDC, antibody-/complement-dependent cytotoxicity.).

Funding

No specific funding was received for this work.

AI-Assistance Statement

Large Language Models assisted with literature discovery/organization, drafting and language editing, and consistency checks under the author’s guidance. The quantitative feasibility scaffold and the subsection “Model-guided transport benchmarks (depot→rim)” were generated with assistance from ChatGPT-5 Thinking. All central scientific concepts, experimental proposals, and interpretations originate from the author (M.A.A.). LLM-suggested experimental alternatives were critically assessed by the author. All references were selected, verified, and approved by the author, who assumes full scientific responsibility.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no potential competing interests.

References

- Serim, S.; Haedke, U.; Verhelst, S. H. L. Activity-based probes for the study of proteases: recent advances and developments. ChemMedChem 2012, 7 (7), 1146–1159. [CrossRef]

- Desnoyers, L. R.; Vasiljeva, O.; Richardson, J. H.; et al. Tumor-specific activation of an EGFR-targeting probody enhances therapeutic index. Science Translational Medicine 2013, 5 (207), 207ra144. [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.-J.; Chuang, C.-H.; Hsieh, Y.-C.; et al. Selective antibody activation through protease-activated pro-antibodies that mask binding sites with inhibitory domains. Scientific Reports 2017, 7 (1), 11587. [CrossRef]

- Geiger, M.; Stubenrauch, K.-G.; Sam, J.; et al. Protease-activation using anti-idiotypic masks enables tumor specificity of a folate receptor 1-T cell bispecific antibody. Nature Communications 2020, 11 (1), 3196. [CrossRef]

- Elter, A.; Yanakieva, D.; Fiebig, D.; et al. Protease-Activation of Fc-Masked Therapeutic Antibodies to Alleviate Off-Tumor Cytotoxicity. Frontiers in Immunology 2021, 12, 715719. [CrossRef]

- Lucchi, R.; Bentanachs, J.; Oller-Salvia, B. The Masking Game: Design of Activatable Antibodies and Mimetics for Selective Therapeutics and Cell Control. ACS Central Science 2021, 7 (5), 724–738. [CrossRef]

- Biewenga, L.; Vermathen, R.; Rosier, B. J. H. M.; Merkx, M. A Generic Antibody-Blocking Protein That Enables pH-Switchable Activation of Antibody Activity. ACS Chemical Biology 2024, 19 (1), 48–57. [CrossRef]

- Isoda, Y., Ohtake, K., Piao, W., Oashi, T., Kiku, F., Uchida, A., ... & Shiraishi, Y. (2024). Rational design of environmentally responsive antibodies with pH-sensing synthetic amino acids. Scientific reports, 14(1), 19428. [CrossRef]

- Lee, P. S.; MacDonald, K. G.; Massi, E.; et al. Improved therapeutic index of an acidic pH-selective antibody. mAbs 2022, 14 (1), 2024642. [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Hu, J.; Cao, Y.; et al. Versatile hydrogel-based drug delivery platform for multimodal cancer therapy from bench to bedside. Applied Materials Today 2024, 39, 102341. [CrossRef]

- Mikhail, A. S., Morhard, R., Mauda-Havakuk, M., Kassin, M., Arrichiello, A., & Wood, B. J. (2023). Hydrogel drug delivery systems for minimally invasive local immunotherapy of cancer. Advanced drug delivery reviews, 202, 115083. [CrossRef]

- Engelen, W., Zhu, K., Subedi, N., Idili, A., Ricci, F., Tel, J., & Merkx, M. (2019). Programmable bivalent peptide–DNA Locks for pH-based control of antibody activity. ACS Central Science, 6(1), 22–31. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y., Li, J., Shu, L., Tian, Z., Wu, S., & Wu, Z. (2024). Ultrasound combined with microbubble mediated immunotherapy for tumor microenvironment. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 15, 1304502. [CrossRef]

- Rui, L.; Min, Q.; Xin, M.; et al. Advances and innovations in ultrasound-based tumor management: current applications and emerging directions. The Ultrasound Journal 2025, 17 (1), 40. [CrossRef]

- Schöne, N., Kemper, M., Menck, K., Evers, G., Krekeler, C., Schulze, A. B., ... & Bleckmann, A. (2024). PD-L1 on large extracellular vesicles is a predictive biomarker for therapy response in tissue PD-L1-low and-negative patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles, 13(3), e12418. [CrossRef]

- de Miguel-Perez, D., Ak, M., Mamindla, P., Russo, A., Zenkin, S., Ak, N., ... & Rolfo, C. (2024). Validation of a multiomic model of plasma extracellular vesicle PD-L1 and radiomics for prediction of response to immunotherapy in NSCLC. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research, 43(1), 81. [CrossRef]

- Lin, H., Li, B., Guo, J., Mai, X., Yu, H., Pan, W., ... & Zheng, L. (2025). Simultaneous detection of membrane protein and mRNA at single extracellular vesicle level by droplet microfluidics for cancer diagnosis. Journal of Advanced Research, 73, 645–657. [CrossRef]

- Taneja, A., Panda, H. S., Panda, J. J., Singh, T. G., & Kour, A. (2025). Revolutionizing Precision Medicine: Unveiling Smart Stimuli-Responsive Nanomedicine. Advanced Therapeutics, e00073. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liao, Y.; Liu, L.; et al. Application of injectable hydrogels in cancer immunotherapy. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2023, 11, 1121887. [CrossRef]

- Klein, C.; Brinkmann, U.; Reichert, J. M.; Kontermann, R. E. The present and future of bispecific antibodies for cancer therapy. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2024, 23 (4), 301–319. [CrossRef]

- Slapak, E. J.; Zwijnenburg, D. A.; Koster, J.; et al. Identification of pancreatic cancer-specific protease substrates for protease-dependent targeted delivery. Oncogenesis 2024, 13 (1), 40. [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Xiao, D.; Xie, F.; et al. Antibody–drug conjugates: Recent advances in linker chemistry. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B 2021, 11 (12), 3889–3907. [CrossRef]

- Oosterhoff, J. J.; Larsen, M. D.; van der Schoot, C. E.; Vidarsson, G. Afucosylated IgG responses in humans – structural clues to the regulation of humoral immunity. Trends in Immunology 2022, 43 (10), 800–814. [CrossRef]

- Jebamani, P., Sriramulu, D. K., Jung, S. T., & Lee, S. G. (2021). Structural study on the impact of S239D/I332E mutations in the binding of Fc and FcγRIIIa. Biotechnology and Bioprocess Engineering, 26(6), 985–992. [CrossRef]

- Braster, R.; Bögels, M.; Benonisson, H.; et al. Afucosylated IgG Targets FcγRIV for Enhanced Tumor Therapy in Mice. Cancers 2021, 13 (10), 2372. [CrossRef]

- de Taeye, S. W.; Schriek, A. I.; Umotoy, J. C.; et al. Afucosylated broadly neutralizing antibodies enhance clearance of HIV-1 infected cells through cell-mediated killing. Communications Biology 2024, 7 (1), 964. [CrossRef]

- Irvine, E. B.; Nikolov, A.; Khan, M. Z.; et al. Fc-engineered antibodies promote neutrophil-dependent control of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nature Microbiology 2024, 9 (9), 2369–2382. [CrossRef]

- Lucchi, R.; Lucana, M. C.; Escobar-Rosales, M.; Díaz-Perlas, C.; Oller-Salvia, B. Site-specific antibody masking enables conditional activation with different stimuli. New Biotechnology 2023, 78, 76–83. [CrossRef]

- Habermann, J.; Happel, D.; Bloch, A.; Shin, C.; Kolmar, H. A Competition-Based Strategy for the Isolation of an Anti-Idiotypic Blocking Module and Fine-Tuning for Conditional Activation of a Therapeutic Antibody. Biotechnology Journal 2024, 19 (12), e202400432. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Fu, H., Fu, Y., Jiang, L., Wang, L., Tong, H., ... & Sun, M. (2023). Knowledge mapping concerning applications of nanocomposite hydrogels for drug delivery: a bibliometric and visualized study (2003–2022). Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 10, 1099616. [CrossRef]

- Rozenfeld, R.; Johnson, P.; Eskioçak, U.; et al. Tumor-specific cleavable linkers. US Patent 20230072822A1, 2023. https://patents.google.com/patent/US20230072822A1/en.

- Deng, H.; Lei, Q.; Wu, Y.; He, Y.; Li, W. Activity-based protein profiling: Recent advances in medicinal chemistry. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2020, 191, 112151. [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Peng, B.; Ong, S. Y.; Wu, Q.; Li, L.; Yao, S. Q. Recent advances in activity-based probes (ABPs) and affinity-based probes (AfBPs) for profiling of enzymes. Chemical Science 2021, 12 (24), 8288–8310. [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.-K.; Wang, Z.; Li, L. Recent advances in chemical proteomics for protein profiling and drug target identification. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 2025, 87, 102605. [CrossRef]

- Millán-Martín, S., Jakes, C., Carillo, S., Gallagher, L., Scheffler, K., Broster, K., & Bones, J. (2024). Multi-attribute method (MAM): an emerging analytical workflow for biopharmaceutical characterization, batch release and cGMP purity testing at the peptide and intact protein level. Critical reviews in analytical chemistry, 54(8), 3234–3251. [CrossRef]

- Dreyer, F. A., Schneider, C., Kovaltsuk, A., Cutting, D., Byrne, M. J., Nissley, D. A., ... & Deane, C. M. (2025, December). Computational design of therapeutic antibodies with improved developability: efficient traversal of binder landscapes and rescue of escape mutations. In mAbs (Vol. 17, No. 1, p. 2511220). Taylor & Francis. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Focused ultrasound and ultrasound stimulated microbubbles in oncology: fundamentals and applications. International Journal of Nanomedicine 2025, 20, 1425–1442. [CrossRef]

- Leong, K. X., Sharma, D., & Czarnota, G. J. (2023). Focused ultrasound and ultrasound stimulated microbubbles in radiotherapy enhancement for cancer treatment. Technology in Cancer Research & Treatment, 22, 15330338231176376. [CrossRef]

- Cioce, A.; Cavani, A.; Cattani, C.; Scopelliti, F. Role of the Skin Immune System in Wound Healing. Cells 2024, 13 (7), 624. [CrossRef]

- Simberg, D.; Moghimi, S. M. Anti-Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) Antibodies: From Where Are We Coming and Where Are We Going. Journal of Nanotheranostics 2024, 5 (3), 99–103. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.; Goswami, S.; Singh, M.; et al. PEGylation as a Tool to Alter Immunological Properties of Nanocarriers. In PEGylated Nanocarriers in Medicine and Pharmacy; Springer: Singapore, 2025; pp 171–193. [CrossRef]

- International Council for Harmonisation. Q14 Analytical Procedure Development—Guidance for Industry. U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/q14-analytical-procedure-development.

- International Council for Harmonisation. Q12 Technical and Regulatory Considerations for Pharmaceutical Product Lifecycle Management. U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/q12-technical-and-regulatory-considerations-pharmaceutical-product-lifecycle-management-guidance.

- Thang, N. H.; Chien, T. B.; Cuong, D. X. Polymer-Based Hydrogels Applied in Drug Delivery: An Overview. Gels 2023, 9 (7), 523. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Li, W.; Yang, J.; et al. Cathepsin B-Responsive Programmed Brain Targeted Delivery System for Chemo-Immunotherapy Combination Therapy of Glioblastoma. ACS Nano 2024, 18 (8), 6445–6462. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).