1. Introduction

The recent 2024 Threat Intelligence Report by Crowd- Strike [

1] revealed that there has been an increase in malicious attacks over the past year with their insights on the cyber threat landscape showing that in 2023, 34 newly identified adversaries emerged. The fastest eCrime breakout time recorded was 2 minutes and 7 seconds. Additionally, there was a 75% increase in cloud intrusions. Furthermore, there was a significant surge in threats such as identity threats. Leveraging generative AI, adversaries like SCATTERED SPIDER have adopted novel tactics to expedite infiltration, including phishing, social engineering, and purchasing genuine credentials from access brokers. Furthermore, the 2024 Threat Report by Sophos [

2] indicated that over 90% of their reported attacks entail some form of data or credential compromise, spanning various methods such as ransomware incursions, data extortion schemes, unauthorized remote access, or straightforward data pilferage. There has been a notable rise observed by Sophos in the incidence of macOS-targeted information theft malware, indicating a trend likely to persist in the foreseeable future. Their earlier report in 2022 [

3] also tracked the detection of 180 attack tools launched between 2020 and 2021 and revealed that several Android malware families went undetected by scanning tools employed by the Google Play Store.

Metamorphic malware in particular, have been extensively studied because they represent one of the most com- plex and dangerous groups of malware. Metamorphic mal- ware transform their code as they propagate, thus evading detection by static signature-based virus scanners, and have the potential to lead to a breed of malicious programs that are virtually undetectable statistically [

4]. These malware also use code obfuscation techniques to challenge deeper static analysis and can also beat dynamic analysers, such as emulators, by altering their behaviour when they detect that they are executing under a controlled environment [

5].

This dangerous group of malware attacks various computing platforms but particularly mobile platforms. Most of these mobile devices run Android operating system which are susceptible to being infected by malicious software. Reports such as those by [

6] indicate that nearly 100% new malicious programs discovered in recent years emanate from Android platforms. This is partly due to the fact that it is open source and does not provide adequate security measures to combat attacks [

7].

One of the widely studied approaches for detecting mal- ware on the Android platform is through the use of adversarial learning techniques [

8]. This method is designed to challenge systems by deliberately feeding them with malicious inputs (

adversarial samples) in order to discover loopholes and subsequently improve detection models to make them more robust to attack. However, a challenge in this approach is to create the adversarial samples required for training.

This paper describes a complete end-to-end pipeline for generating a suite of novel, malicious malware samples and using these samples to improve training of ML detection models. The pipeline uses an Evolutionary Algorithm [

9] (a population-based meta-heuristic search process) to discover novel malicious variants of existing malware that evade current detection systems. The new generated mutants are used to augment existing datasets and to improve trained ML models. Some preliminary findings of this research have been disseminated in [

10,

11]. This article serves as the inaugural comprehensive exposition of the entire pipeline, wherein all components of the proposed framework are cohesively integrated and presented for the first time.

In addition to providing a complete description of the framework, this paper extends our previous work in [

10,

12] by examining how our proposed EA can generate vari- ants from three malicious families selected based on their malicious payload. Further, we conducted supplementary analyses to evaluate the diversity of the variants generated from multiple executions of the EA. This investigation aimed to determine whether the variants produced across different runs exhibited distinct characteristics and to assess their diversity based on three specific metrics. These metrics pertain to: (1) structural dissimilarity among the variants,

(2) behavioural dissimilarity, and (3) the variants’ efficacy in evading several established detection mechanisms. By examining these dimensions, we aimed to gain insights into the variability and adaptability of the variants produced by the EA under varying conditions. Also, the performance of the EA in terms of its ability to find evasive variants is compared to a random search for evasive variants in order to justify the need for the meta-heuristic search algorithm. We also extended our work in [

11,

12], where we improved the classification of metamorphic malware by augmenting training data with evolved mutant samples, by comparing the performance of not just binary models as in [

11] but also multiclass models. We then used a transformer — Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) that had been pretrained on a large NLP dataset to improve the classification of metamorphic malware.

The research endeavor aimed to address the following five key questions:

How does a fitness function used in the EA influence the capability of our method to discover new evasive variants?

How diverse is a set of newly-produced, novel variants with respect to the range of their behavioural signatures and their structural similarity in comparison with the original malware?

How do the 63 main stream antivirus products (also known as antivirus engines) vary in their capability to detect our newly-produced malware variants for each family of malware tested?

Which well-known Machine Learning (ML) models are improved more significantly, when trained with our newly-produced mutants, in classification of meta- morphic malware?

Can a transformer, such as BERT that has been trained on large NLP datasets, be used in a transfer learning context to improve classification of metamorphic mal- ware, with our newly-produced mutants?

The rest of the paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 provides a background to the research. In

Section 3, we describe the learning process involved in defending against metamorphic malware using adversarial samples, while

Section 4 explains our experimental approach and discusses the results obtained. In

Section 5, we conclude our findings and present potential future research.

2. Related Work

Metamorphic malware represents one of the most dangerous groups of complex malware. This family of malware changes its own code over generations. Any two dissimilar instances of malware, named

mal and

mal′, are metamorphic if any malicious attack to a system from

mal is an attack from

mal′ and vice versa [

5]. To transform itself, metamorphic malware uses a number of mutation techniques, including: Register swapping, Instruction substitution, Instruction re-ordering, Subroutine permutation, Garbage or junk code insertion and Formal grammar mutation [

13].

Several authors focus on novel methods for detecting metamorphic malware. For instance, an approach developed by [

14] detects metamorphic malware with the aid of text mining algorithms and dynamic analysis of the malware. Behaviour based aggregated signatures are also used by [

15] in metamorphic malware detection. Structural entropy [

16] and malware normalisation strategies [

17] have also been used in detecting these family of malware. However, while these techniques work well on already known malware, they do not perform well on metamorphic variants that changes its form between generations.

Several platforms to stress-test antivirus systems have been proposed. For example, ADAM [

18] assesses how good AV engines are in detecting obfuscated malware which they create automatically while retaining the original malware’s functionality. Similarly, [

19] proposes a system termed DroidChameleon which carries out tests to see how well anti-malware systems can detect obfuscated malware. They analyse more attacks vectors than those of [

18] through an approach which mutates Android applications automatically using various mutation techniques.

In detecting metamorphic malware, a number of Heuristic based and ML methods such as Sequential Pattern Mining [

20], Decision Trees (DT) [

21], Hidden Markov Models (HMM) [

22], and Support Vector Machines (SVM) [

23] have been employed. The aforementioned ML techniques reviewed are designed as a black box so as to improve network security, these approaches assume that since the attackers do not have access to the underlying ML algo- rithm, they will struggle in attacking them. However, this assumption is flawed by the fact that the attackers have designed adversarial strategies to probe ML models [

24], and consequently discover the design features that can be exploited to create evasive malware that goes undetected by the ML models.

Adversarial learning has been recently introduced as a new strategy to defend against this exploitation. This approach is leveraged to generate adversarial data samples that take advantage of the loopholes in ML models. Learning from these generated adversarial samples in a malware detection problem picks up the robustness of a malware detector, in particular defending against mutable malware. Recent research gives its favour to evolutionary computing in new adversarial learning strategies for creating variants of metamorphic malware to help improve detection systems [

25,

26,

27].

Genetic Programming (GP) - a specific type of Evolutionary Algorithm - has been introduced by [

25,

26] to develop new metamorphic malware variants. The goal in [

25] was to create new variants of mobile malware by mutating the initial code using GP and a simple fitness function that measures the proportion of the detectors evaded by a mutant. The newly generated mutants were tested against eight antivirus engines and the experimental results show that the malware variants evolved by GP are more evasive than the variants produced with other obfuscation methods. GP is also applied in [

26] to create metamorphic Portable Document Format (PDF) malware that evade the PDF detec- tors (i.e., PDFrate and Hidost classifiers), whose detection results are the only factor considered in the fitness function used in the work. More recently, [

27] employed Genetic Algorithm (GA) in detecting mutable windows malware using essentially detection rate as the fitness measure employed in their work. As neither the fitness functions used in [

25,

26,

27] take into consideration the diversity of the variants produced but simply focus on evasiveness, the variants generated though evasive might not help ML models generalise and consequently impede on the accuracy of such models.

To advance the state of the art in adversarial learning driven mobile malware detection, we propose to augment the fitness function with a wider range of malware characteristics, including code structure, behaviour, and ability to evade detection. To further reduce the costs of training a malware detector, we adopt transfer learning to reuse BERT that was pre-trained for NLP tasks for metamorphic malware detection. As such the number of evolved variants of malware to be used in detection model training can be reduced significantly, which results in a massive direct cost reduction.

3. Learning to Defend Against Metamorphic Malware Using Adversarial Samples

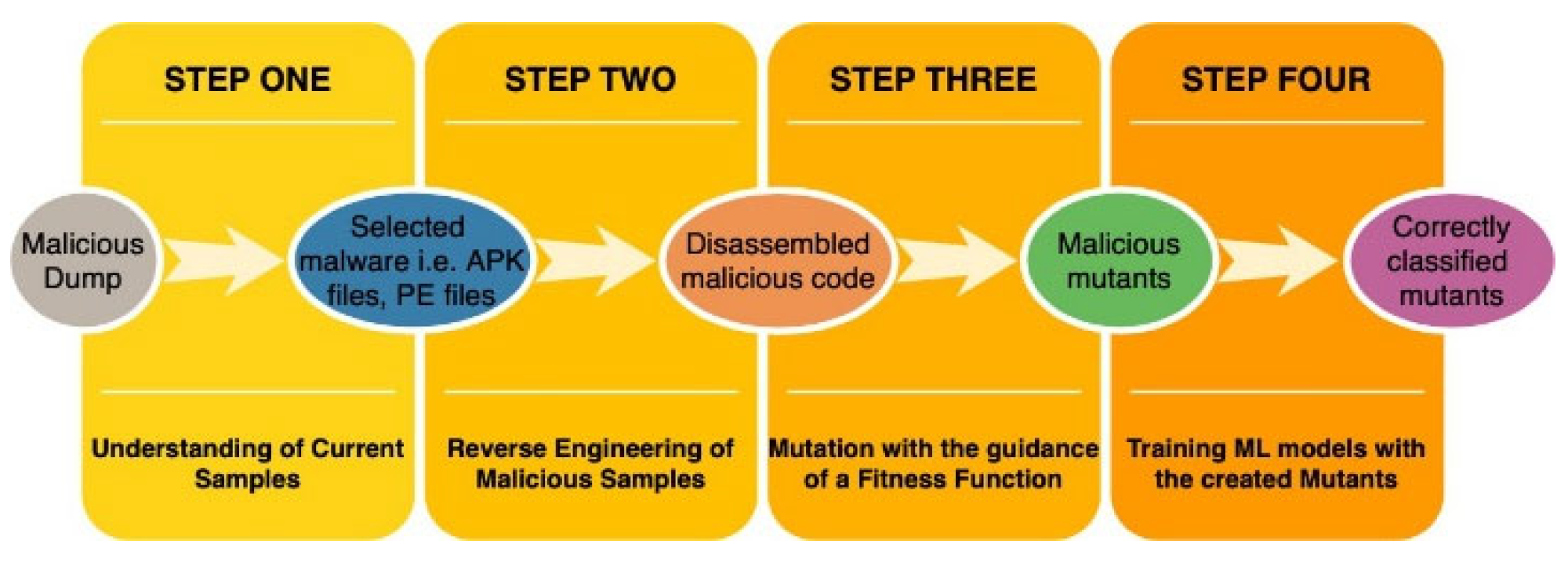

We present in this section a generic framework as shown in

Figure 1, for the generation of executable malicious mutants to predict the future behaviours of metamorphic malware. The framework can be generalised and its various components can be adapted for various applications. The process of generating adversarial samples includes the following steps:

Step one: An understanding of the current samples is essential. This includes understanding what kind of data is required for analysis. For instance, the samples might comprise mobile malware such as Android malware source. The framework could be generalised to other kinds of malware depending on the platform (such as desktop based malware) or operating system (such as iOS malware) in which the malware samples are executed.

Step two: This includes reverse engineering the malware to a form in which variants can be easily created. This is where the need for a disassembly tool such apktool comes in. Apktool [

28] is a disassembly tool for Android samples i.e., apk files which were used in this research. Other disassembly tools could be used depending on the platform the malware runs. For example, Portable Executable (PE) Viewers (e.g., CFF Explorer

1) for desktop based malware.

Step three: This is stage where the samples are mutated with the guidance of a fitness function to generate novel malware mutants. This step treats the disassembled malware as a piece of code and creates/uses mutation operators to transform the code in order to create mutants. In other words, as far as the disassembled malware can be represented as a code it can be generalised but the operators need to be tailored/customised depending on the kind of code being studied. The transformation of the malicious binaries to create diverse mutants was done in this work based on characteristics of malware such as its structure, behaviour and ability to evade existing detection engines. Other characteristics of malware could also be used to guide the process of finding malicious and diverse mutants.

Step four: The final step uses the mutants created in Step three to train ML models in order to provide improved protection against future mutants. This does not necessarily involve the development of new ML models but could use standard ML models with known complexities. In this work, we use both feature based and sequence based ML models. Again, other ML models could be used in this step.

To test whether variants are

executable, the mutated smali is recompiled using

apktool, signed using

apksigner and aligned using

zipalign. The aforementioned steps are necessary in order to generate an apk. The resulting apk is then run on an

Android emulator to check that it executes. Finally, once a set of mutants have been evolved, they are tested to determine whether they are still malicious using Droidbox [

29]. Droidbox is a sandbox designed for Android that can be used in the dynamic analysis of apk files. The dynamic analysis involves studying the behaviour of the apk while running it. Once an apk is submitted to Droidbox, it executes the apk and collects information relating to the files created, deleted and downloaded by the apk, connections opened, traces of API calls among others.

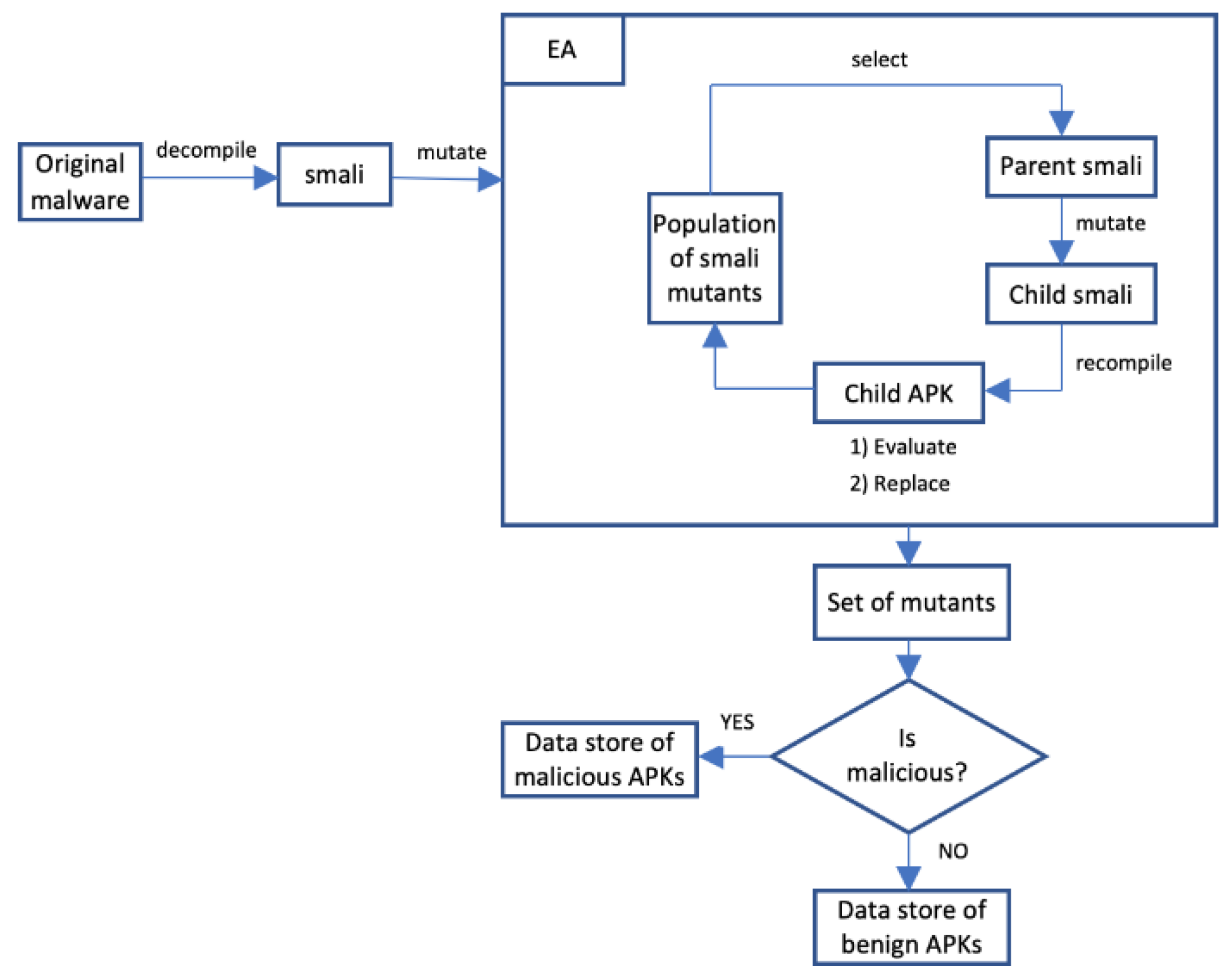

In this work, the mutants are generated using an EA based mutation engine. It can be seen from

Figure 2 that the original malware is first disassembled and then converted to smali files using Apktool. The EA section is where the adversarial samples are generated, optimised to maximise evasiveness, and structural and behavioural similarity to the original malware. The best APKs generated are stored in a data store after they have undergone a maliciousness test to see that they retain their maliciousness. We save variants that retain their maliciousness to serve as training data for machine learning models.

3.1. Evolutionary Algorithm

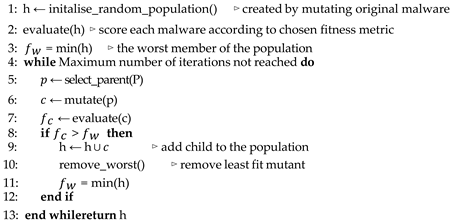

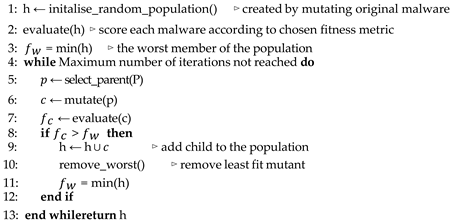

The EA used in this work is given in Alg. 1 as presented in our previous work in [

30].

|

Algorithm 1 Evolutionary Algorithm |

|

The EA begins with an initial population of random malicious mutants. In a repeating cycle, parents are selected from this population and mutated to create offspring. The specific operators used within the EA are now described.

3.2. Initialisation

To create an initial population of mutants, a single mutation operator (as described in

Section 3.4) is applied to the

original malware. The mutation operator is chosen at random and applied exactly once. This process is repeated to create

p mutants, each time starting from the original malware.

3.3. Selection of Parent Malware

The selection operator used to select the parent malware aims at biasing the search towards selecting fitter parents to create offspring from them. In this work, a standard operator, tournament selection [

31] has been employed. We have chosen this selection operator because it can be easily tuned to vary selection pressure. In tournament selection,

k potential parents are selected at random. The parent with the highest fitness value among the

k prospective parents is selected to be recombined to form children in the next iteration.

3.4. Generation of Mutant Offspring

To create a mutant (i.e., a child) from a parent, a mutation operator is applied to the smali file obtained from decompiling the malware. Three mutation operators are defined: only one mutation operator is selected at uniform random to perform each mutation. The description of the three mutation operators is as follows:

M1: Instruction reordering - this introduces a goto statement that jumps to a label that does nothing.

M2: Garbage code insertion - inserts junk codes like line numbers that do not affect the functionality of the code.

M3: Variable swapping - this replaces variables with other valid variables in the program code while ensuring consistency with the variable names.

3.5. Fitness Functions for Evaluation

Three different fitness functions are evaluated separately as methods of guiding the evolutionary search towards novel variants. The fitness metrics are selected based on the characteristics of malware that are, their structure, behaviour and ability to evade a large set of detectors. In order to create adversarial mutants, each of the fitness values is minimised.

DR (Detection Rate): shows the proportion of detectors within a specific AV engine that detect the mutant. This returns a value between 0 and 1, with 0 signifying that no detector recognised the mutant. This uses Virustotal3, which is an online based malware detection service that contains 63 updated antivirus engines to provide the suite of AV engines.

BS (Behavioural Similarity): compares the behavioural signature of the mutant to the original malware and returns a value between 0 and 1 in which 0 indicates maximum dissimilarity. This uses Strace4 to monitor the behaviour of the mutants by keeping track of their system calls. The mutants’ main activity is executed using MonkeyRunner5 in order to simulate user interaction. The output of Strace is a file comprised of the variant’s process ID, along with its system calls and parameters. Thus, the file is transformed to a fixed sized vector whose elements correspond to the frequency of the system call used. Since 251 system calls are considered, the vector consists of 251 elements. The behavioural similarity between the original malware and its mutants is then calculated as the cosine similarity between their system call vectors.

-

SS (Structural Similarity): is a value between 0 and 1 that measures the semantic similarity between the mutant and original malware by comparing lines of code (where 0 represents the most dissimilarity). This uses several similarity metrics including text (such as cosine similarity) and source code (such as JPlag [

32]

- a plagiarism detector) similarity metrics. Each of the similarity metrics produces a value between 0 and 1 where a score of 1 means the original malware and the variant are identical, and 0 means the original malware and the variant are completely different. The average of these metrics is computed to measure the structural similarity.

If a mutant is deemed non-executable, then it is assigned a fitness value of 1 (i.e., the worst possible fitness), regardless of the measured metric or the fitness function used.

Note that only DR directly rewards mutants for evading detection. Functions BS and SS reward behavioural and structural dissimilarity, which implicitly might lead to mutants that evade detection. The idea of rewarding novelty rather than objective fitness has received a great deal of attention in the EA community, with a significant body of work showing that it leads to evolution finding stepping stones that enable very high-quality solutions to be reached [

33,

34].

4. Experiments

4.1. Malware Samples for Evaluation

The malware utilised in this work are from the Contagio Minidump [

35] and MalGenome [

36]. Contagio Minidump comprises 237 malware samples while MalGenome on the other hand consists of 1,260 Android samples from 49 different malware families. We select samples from these dump based on their malicious payload. In categorising the samples, we use four groups categorised by the authors in [

37]. These include privilege escalation, remote control such as Droidkungfu [

38], financial charges such as GGtracker [

39], and personal information stealing such as Dougalek [

40]. The instances of the parent malware used to initialise the EA were randomly selected from the dump using the aforementioned malicious payload.

4.2. Evolutionary Algorithm - Method

Experiments are conducted on the three chosen families (Dougalek, Droidkungfu and GGtracker); for each family, we run the Evolutionary Algorithm using each of the three defined fitness functions, resulting in nine different treatments. Given the stochastic nature of the EA, each treatment is repeated 10 times. The best fitness obtained in each run is recorded.

4.2.1. Evolutionary Based Parameters

The parameters used in the evolutionary program to create the evasive malware are summarised in

Table 1 and they are derived following empirical analysis. The evolutionary program uses uniform mutation with a mutation rate of one; this value is chosen to ensure that mutation always occurs, given that this is the only variation operator used, as crossover is not used in the experiments. The crossover operator is not used, as it leads to the generation of non- executable variants. The EA uses tournament selection with a tournament size of five for a fair level of selection pressure. As a result of the computational cost involved in running the experiments, the number of iterations is limited, and the evolutionary program is run 100 times. The size of the population is then set proportionally to 20.

Furthermore, to justify the use of an EA, the results derived while using the EA is compared against a Random Search (RS): 120 random variants are generated and evaluated. This number represents the total number of points visited in the search space by the EA. Comparison of these results will indicate whether the evolutionary operators are useful in locating high-fitness variants.

4.2.2. Collection of Relevant Metrics

In carrying out the experimental work, the following tools and libraries were employed.

-

AV engine: The AV engine used in this work is Virus- total and the function DR(

x) derives its value from to tokens and then applying an algorithm to deduce the matches between their token lists from the biggest to the least matches [

32].

- -

Sherlock: It sorts two programs based on their similarity. It converts the programs to signatures and calculates the similarity between the signatures [

32].

- -

Normalized Compression Distance: This measures the distance between two files based on compression. Given the original malware as

m and its variants as

v the compression distance is given as [

43];

it. Virustotal is an online based malware detection service that contains 63 updated antivirus engines, to check the evasiveness of the mutants. The fitness value produced by this function represents the percentage of antivirus engines the variants evaded. It is normalised to a value between 0 and 1. Where 0 means the variant was able to evade being detected by all the antivirus engines and 1 means the variant was detected by all antivirus engines. It also retains the information regarding the mutants evasion score.

Collecting the behavioural trace: Strace is used to monitor the behaviour of the variants by keeping track of their system calls. The variants’ main activity is executed using MonkeyRunner in order to simulate user interaction. The output of Strace is a file comprising the variant’s process ID along with its system calls and parameters. We transform this into a fixed sized vector whose elements correspond to the frequency of the system call used. Since we consider 251 system calls, the vector consists of 251 elements. BS(x) calculates the cosine similarity between the system call vectors of the original malware families and their variants and that represents the behavioural similarity.

-

Libraries for structural similarity (SS(x)): In measuring the text based similarity between the original malware families and their variants the following metrics are used.

- –

Cosine similarity: This measures the cosine angle between two nonzero vectors.

- –

Levenshtein: This similarity metric seeks to find the number of deletions, insertions or substitutions needed to transform a file A to a file B [

41].

- –

FuzzyWuzzy: This measure does string matching to find strings that match a specific pattern approximately [

42].

In measuring the source-code level similarity between the original malware and the variants we use the following similarity metrics.

– Jplag: This measures the similarity between two source codes by first converting the source codes

where Z(m) is the compressed file m’s length compressed using a compressor Z. The compressor used in this work is 7-zip.

Each of the similarity metrics produces a value between 0 and 1 where a score of 1 means the original malware and the variant are identical and 0 means the original malware and the variant are completely different. We compute the average of these metrics and that represents the structural similarity. We implement these metrics using various Python and C libraries.

4.3. Evolutionary Algorithm - Results and Analysis

4.3.1. Influence of Fitness Function on Evasiveness of Evolved Mutants

In this section we investigate the influence of each of the three fitness functions in terms of their ability to locate novel evasive mutants.

Following the 10-run approach using each of the fitness functions in Subsection 3.5, we test each of the mutants to ensure they are still malicious, as explained in Subsection 3.

Table 2 shows how many variants retain their maliciousness. From

Table 2, we see that a minimum of 70% of runs result in malicious variants, regardless of the fitness function used or malware family. The EA finds malicious runs for 100% of the runs using the evasiveness metric (DR(

x)) with Droidkungfu, and also in the Dougalek family using the structural similarity metric (SS(

x)).

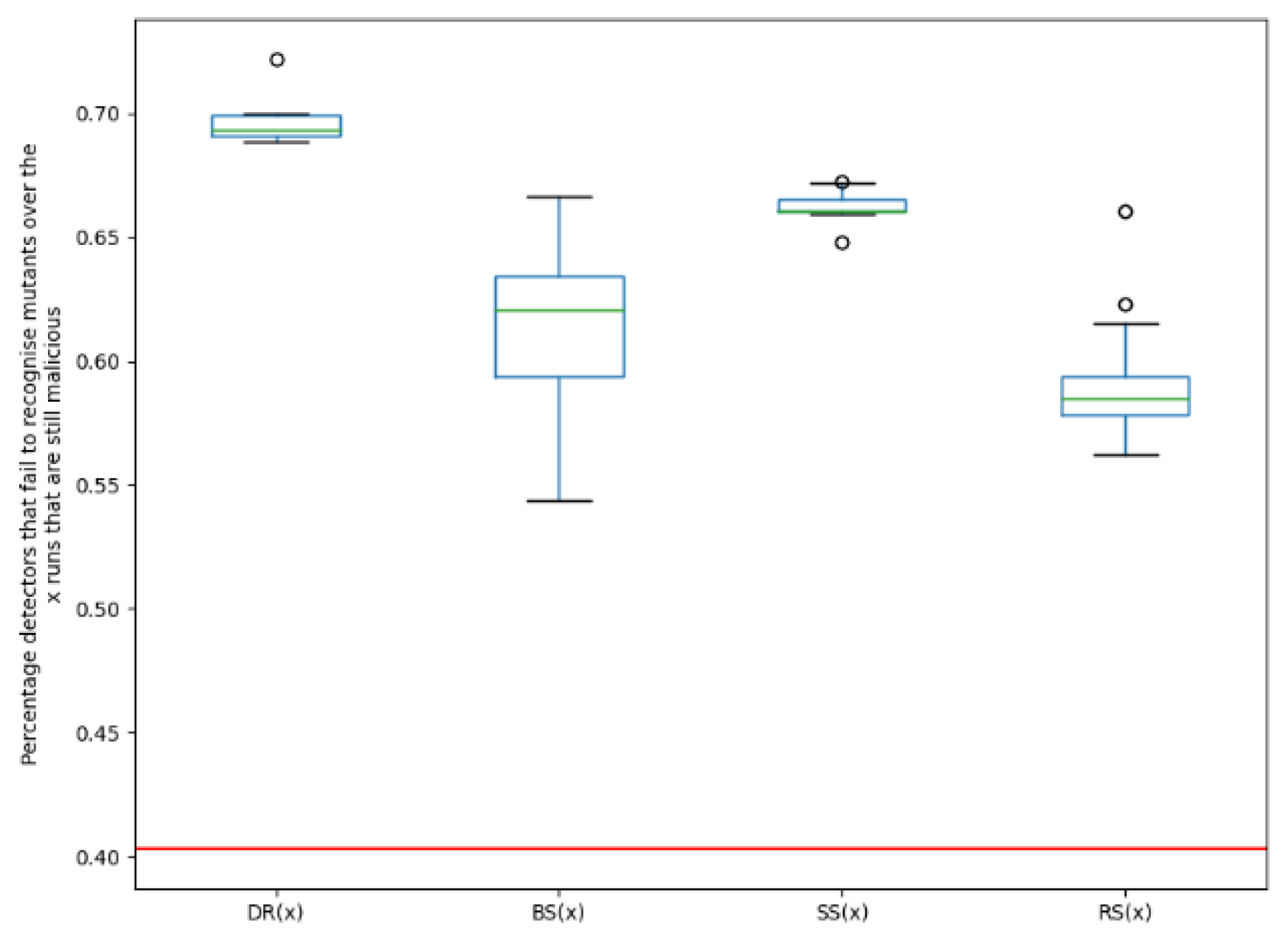

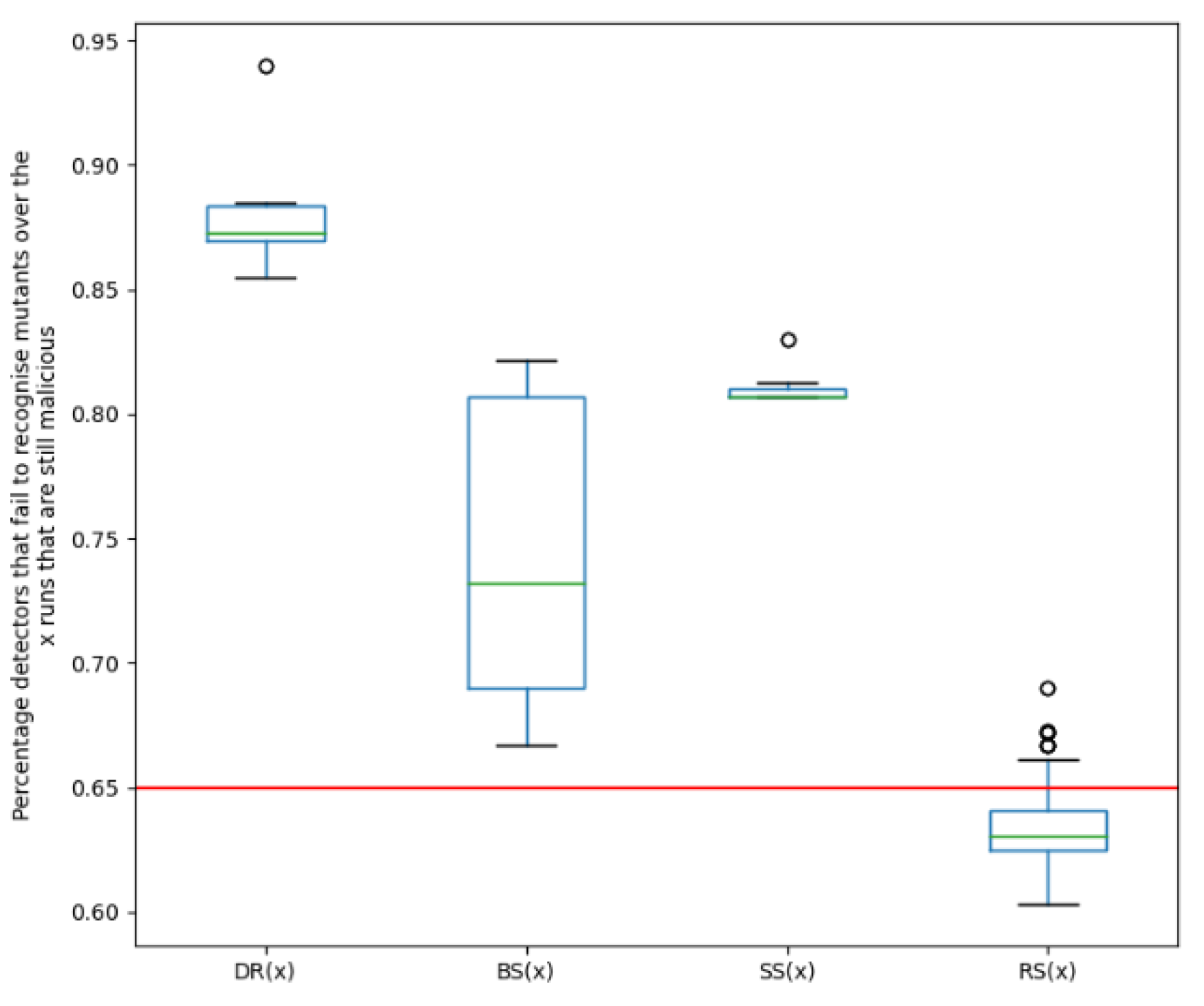

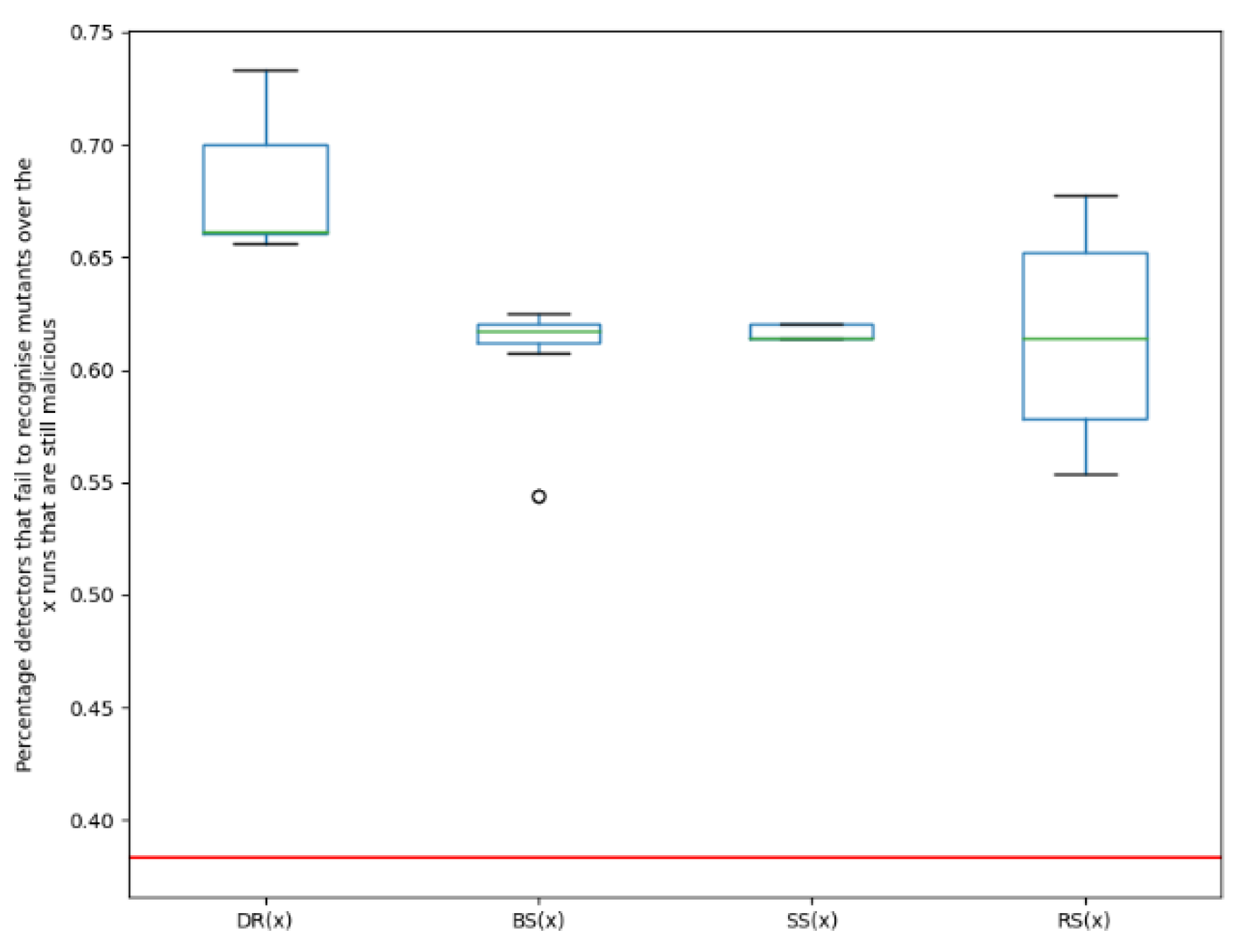

The percentage of detectors that fail to recognise the novel variants over the

x runs that are malicious, is plotted. This is repeated for each malware family using each of the fitness functions. In

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, the red line shows the percentage of detectors that fail to recognise the original malware. Additionally, the performance of the EA in terms of its ability to find evasive variants is compared to a random search for evasive variants.

-

Dougalek: It can be noted from the boxplot in

Figure 3, that for each of the functions in the fitness function, the resulting variants are more evasive than the original malware. This means a higher percentage of detectors failed to identify the new variants, as compared to the original malware. 40.3% of the detection engines failed to detect the original malware while for the best evolved variants of Dougalek, 72%, 66.7% and 67.3% of engines failed to detect the new variants created using functions DR(

x), BS(

x) and SS(

x) respectively. It is particularly interesting to note that even when evasive variants are not directly evolved (i.e., using fitness function DR(

x)), evasive variants can still be created, as seen from the boxplots of BS(

x) and SS(

x). It can also be noted that for the Dougalek family, the plots of evasiveness of the newly created variants for both DR(

x) and SS(

x) are similar, as seen in

Figure 3. This implies that even when one is evolving for structurally dissimilar variants, variants are still obtained, that are almost as evasive as when one is evolving for evasive variants.

Furthermore, from

Figure 3, it can be observed that the median percentage of engines that failed to detect the new mutants for the Dougalek family for the EA ranges from 62.1% to 69.4% depending on the fitness function employed. However, for a Random Search (RS(

x)) for evasive variants, the median percentage of engines that failed to detect the new mutants is 58.5%. Therefore, it can be said that an improved evasive performance is noticed when the EA is used as compared to using a random search.

-

Droidkungfu: Similarly from

Figure 4, it can be observed that for each of the functions in the fitness function, the resulting variants are also more evasive than the original malware. It can also be noted that 65% of the detection engines failed to detect the original malware, while for the best evolved variants, 94%, 82.1% and 83% of engines failed to detect the new variants created using functions DR(

x), BS(

x) and SS(

x), respectively. This also shows that even when there is no evolving for evasive variants (DR(

x)), evasive variants for functions BS(

x) and SS(

x) can still be created.

It can also be seen from

Figure 4, that the median percentage of engines that failed to detect the new mutants for the Droidkungfu family for the EA ranges from 73.2% to 87.3% depending on the fitness function employed. However, for a Random Search (RS(

x)) for evasive variants, the median percentage of engines that failed to detect the new mutants is 63.1%. Again, this shows that an improved evasive performance is noticed when the EA is used as compared to using a random search.

GGtracker: Also in

Figure 5, each of the functions in the fitness function produces variants that are more evasive than the original malware. From

Figure 5, it is apparent that only 38.3% of the detection engines failed to detect the original malware while for the best evolved variants, 73.3%, 62.1% and 62.1% of engines failed to detect the new variants created using functions DR(

x), BS(

x) and SS(

x) respectively. It can also be observed from

Figure 5, that the plots of evasiveness of the newly created variants for DR(

x), BS(

x) and SS(

x) are also similar. This means that even when evolving for behaviourally and structurally dissimilar variants, variants that are almost as evasive as when we are evolving directly for evasive variants, are still obtained.

From

Figure 5, it can be observed that the median percentage of engines that failed to detect the new mutants for the GGtracker family for the EA ranges from 61.4% to 66% depending on the fitness function employed. For the Random Search (RS(

x)) for evasive variants however, the median percentage of engines that failed to detect the new mutants is 61.4%. RS(

x) obtains a similar median to BS(

x) and SS(

x), showing that these two metrics using an evolutionary search do not outperform RS(

x). However,

Figure 5 indicates that the DR(

x) metric used with the EA outperforms RS(

x).

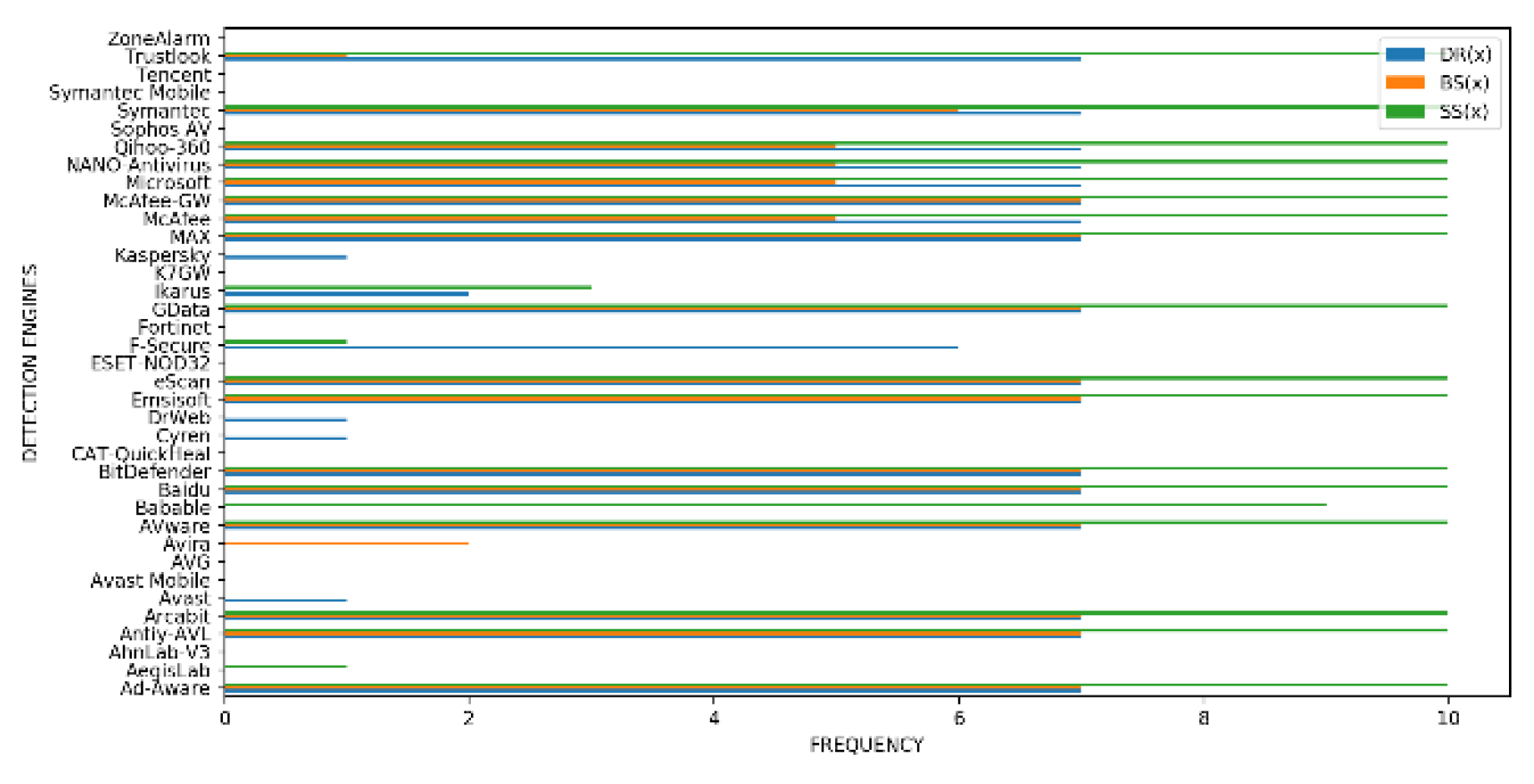

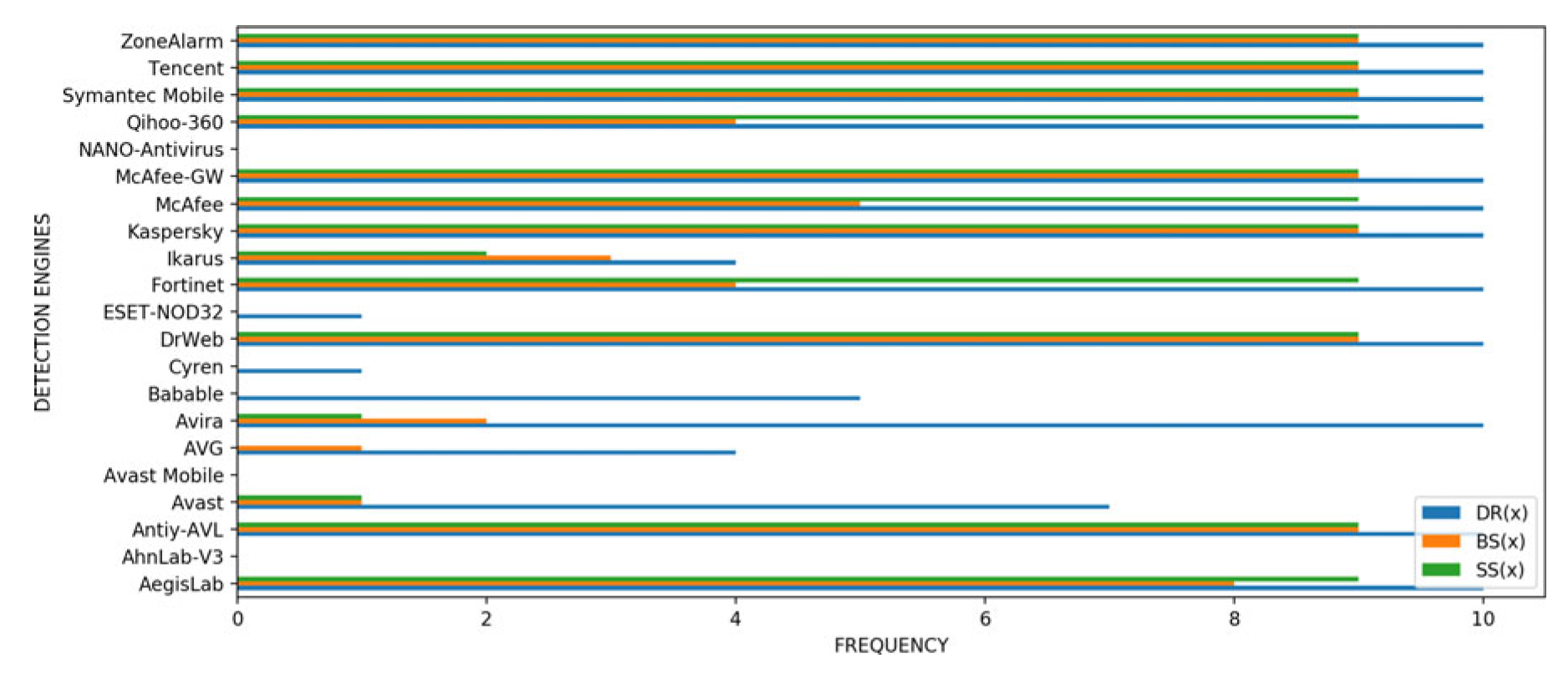

4.3.2. Analysis of Evasion Characteristics of New Mutants

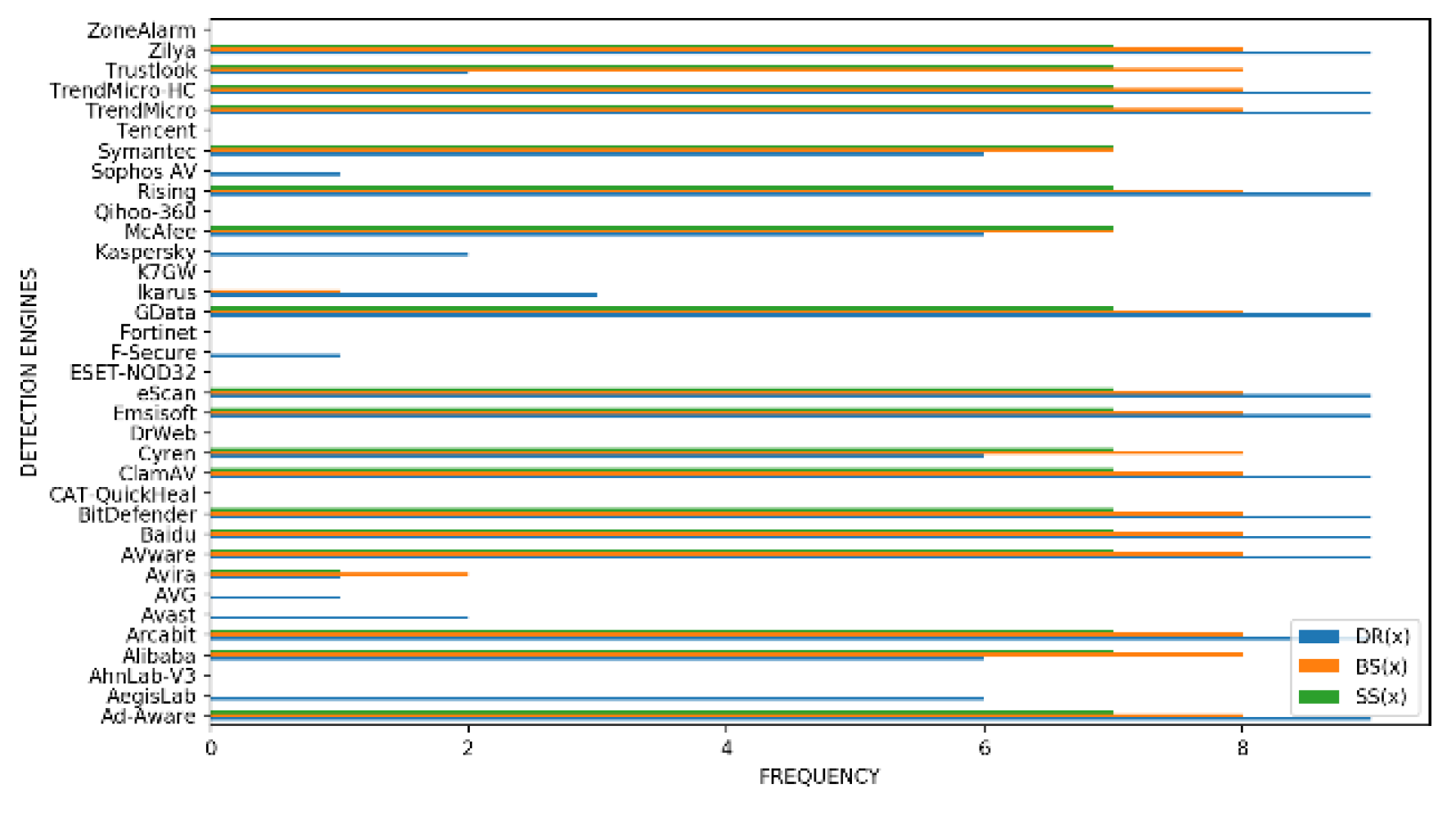

In this section, we conduct an analysis of which of the detection engines were fooled by the novel mutants evolved but were not fooled by the original malware. For each of the

m malicious variants produced by 10 runs of the evolutionary algorithm for a given fitness function, we count the frequency

f which a detector

d failed to detect the malware (0 <

f < 10). In

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8, the blue histograms represent results for function DR(

x), the orange ones represent results for function BS(

x) and the green histograms represent the results for function SS(

x).

Dougalek: The plot in

Figure 6, shows that for fitness function DR(

x), fourteen engines including AVG and Tencent, were not fooled by any of the mutants. Seventeen engines on the other hand, such as AVware and McAfee, were fooled by all the mutants. The number of engines that were not fooled by any variant when we used fitness function BS(

x) is nineteen. Examples include AVG and Fortinet. Eleven engines including GData and McAfee, however, were fooled by all the mutants for function BS(

x). Also, sixteen engines were not fooled by any variants for the function SS(

x). Examples include Symantec Mobile and Fortinet. Seventeen engines however were fooled 100% of the time for function SS(

x) - examples include McAfee-GW and BitDefender.

-

Droidkungfu: From

Figure 7, we see that three engines were not fooled by any of the mutants for function DR(

x). Examples include Avast Mobile and NANO Antivirus. Twelve engines however, were fooled by all the mutants 100% of the time for function DR(

x)

- examples include Fortinet and Kaspersky. For fitness function BS(x), six engines were not fooled by any of the mutants, some of such engines include Avast Mobile and NANO Antivirus. Seven engines including Symantec Mobile and Tencent, on the other hand, were fooled by all the mutants. Furthermore, seven engines, such as AVG and Cyren, were not fooled by any mutant for function SS(x). On the other hand, eleven engines were fooled by all the mutants for function SS(x). Examples include Kaspersky and ZoneAlarm.

GGtracker: In

Figure 8, we see that the number of engines not fooled by any variant when we use fitness function DR(

x) is nine. Examples include CAT- QuickHeal and DrWeb. Thirteen engines however, were fooled by all the mutants for function DR(

x) with examples like Arcabit and BitDefender. Also, fifteen engines were not fooled by any variants for function BS(

x). Examples include K7GW and Kasper- sky. Sixteen engines however were fooled all the time for function BS(

x) - examples include AVware and TrendMicro. In addition, sixteen engines were not fooled by any mutant for function SS(

x) with examples such as Avast and AVG. On the other hand, eighteen engines were fooled by all the mutants for function SS(

x). Examples include Cyren and McAfee.

It is evident that for two of the families of malware studied (Dougalek and Droidkungfu), the fitness function DR(x) led to more engines being fooled by the novel mutants than the other fitness functions - BS(x) and SS(x). This stands to reason being that DR(x) was designed to evolve for evasiveness. It is however interesting, that for the GGtracker family, more engines were fooled by the mutants generated using fitness functions BS(x) and SS(x), than for fitness function DR(x).

It is important to check that the variants created are not only evasive but that they are also diverse. However, diversity of the samples can mean several things such as behavioural diversity which means the behavioural characteristics of the variants are as dissimilar as possible to those of the parent malware and to each other. It could also mean structural diversity that shows varying code-level and semantic structures among the different variants and their parent malware. Also, it could mean that the mutants differ in terms of how they evade detection by existing detection engines.

Section 4.3.2 has attempted to use only one of the fitness functions at one time to maximise the individual metrics (i.e., structural dissimilarity, behavioural dissimilarity and evasiveness) of the variants against their parent malware. The maximisation of these metrics drives optimal diversity. Hence, they are used to guide the search towards a variant that is most dissimilar to the original malware. This section further studies the diversity of a set of variants generated from multiple runs of the EA in order to find out if the EA runs truly produce different variants, and how diverse they are with respect to the three metrics.

The diversity of a set of variants generated for each of the malware classes, is quantified and measured by:

The terms are explained below.

- (i)

A Detection Signature describes the behaviour of the 63 detection engines in response to a given variant. It helps to measure how diverse the evolved variants are with respect to their “detection” signatures. A detection signature d is defined for each evolved variant as a vector with 63 elements, and each of which corresponds to one of the 63 detection engines used for testing. The value of an element di is set to 1 if the corresponding engine detected the variant and 0 otherwise. For each subset of n variants denoted by (m, f), (i.e., from a malware family m evolved using fitness function f ), the percentage of unique detection signatures within the set of size n to obtain an indication of variant diversity, with respect to the ability of the detection engine to recognise the variants, is noted. 76 new malicious mutants are evolved in total (considering all classes and fitness functions). After calculating the 76 detection vectors, any duplicates are removed (i.e., cases where variants within a subset defined by a malware family and fitness function have identical vectors). This reduces the total number of vectors to 46.

It is evident in the experimental results shown in

Table 3, that in terms of uniqueness of the detection signatures, the highest percentage of unique variants is seen in the Droidkungfu family when evolving for evasive (with 90% uniqueness) and behaviourally dissimilar (with 89% uniqueness) variants. However, when evolving for structurally dissimilar variants, the most unique variants are found in the Dougalek family (with a 50% uniqueness score).

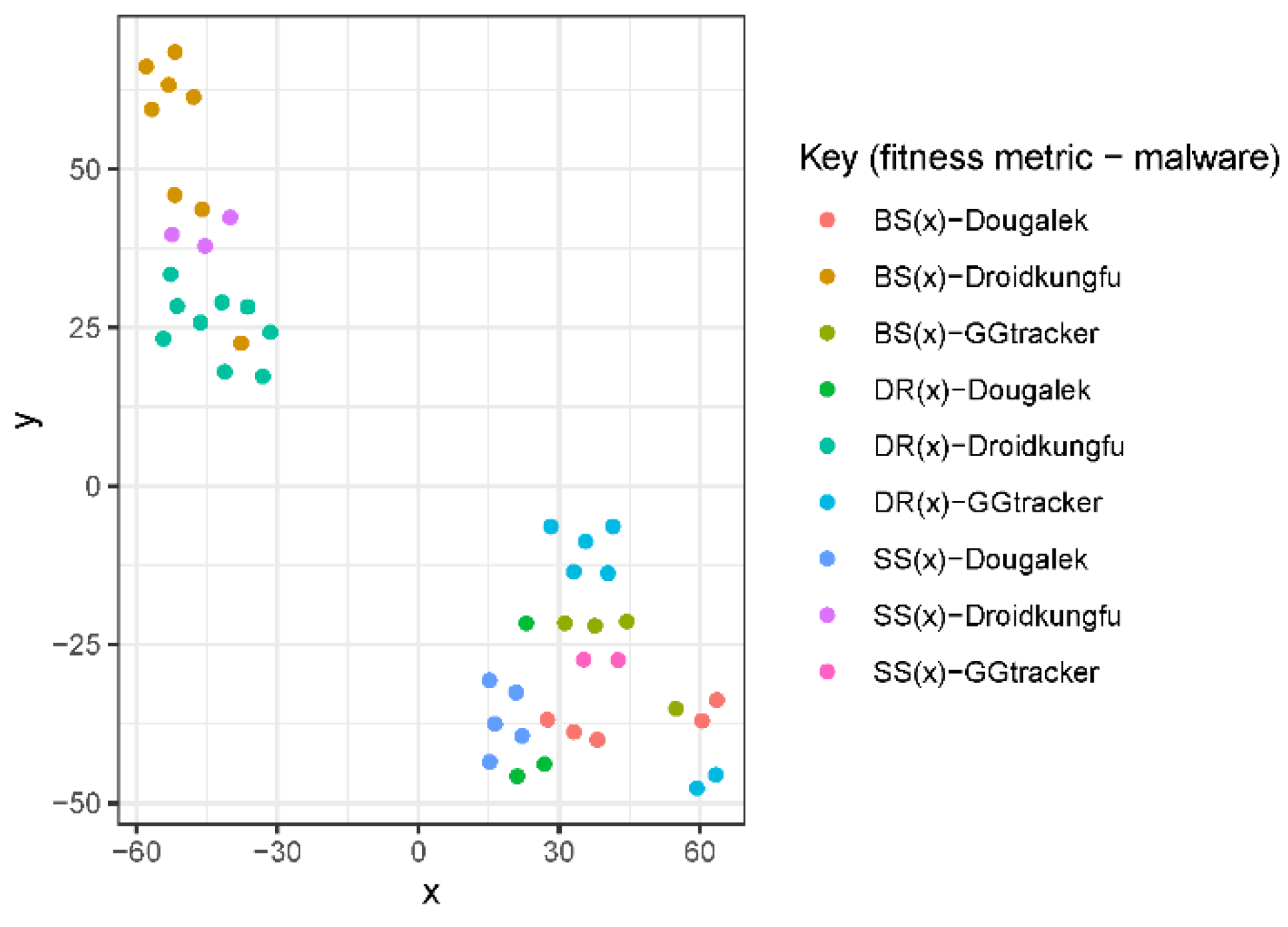

The 63-dimensional detection signatures obtained from the evolved mutants, are mapped onto a 2- dimensional space using t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) [

44]; this is a non-linear dimensionality reduction algorithm commonly used for exploring high-dimensional data. It seeks to retain both the local and global structure of the data at the same time, (i.e., mapping nearby points on the manifold to nearby points in the low-dimensional representation (preserving local structure) while also preserving geometry at all scales, mapping far away points to far away points (global structure)).

Figure 9 shows a plot obtained from t-SNE of the evolved malicious variants (after removing duplicates) in order to visualise diversity within the detection signatures. It can be noted that a distinct cluster is formed by variants of the Droidkungfu class as seen in the top left region of

Figure 9, with the other two malware families forming a separate cluster. Within each class cluster, further clusters can be identified according to the method used to generate the mutant. Within each of these sub-clusters, there is also diversity with respect to the detection signature.

Therefore, it is concluded that although not all the clusters are clearly differentiated by t-SNE, there is some evidence of clustering as seen in the Droid- kungfu class. Consequently it can be said that the evolutionary approach used, is capable of generating distinct and diverse malware variants, providing useful data to develop new detection engines.

- (ii)

Diversity with respect to Behavioural Signature: We define the

behavioural signature of a variant as a vector

b comprising 251 elements, and each of which represents a system call invoked by the variant. Each element

bi has a value that equals the frequency of the corresponding system call used. In the same manner as previously described with respect to diversity in the detection signatures, we now count the number of unique

behavioural vectors for each subset of evolved variants (

m,

f). In terms of the uniqueness of the behaviour signature, the results in

Table 4 shows that Dougalek is the most unique family with 100% uniqueness when we are evolving for evasive and behaviourally dissimilar variants. GGtracker on the other hand is the most unique family in terms of the evolution for structurally dissimilar variants. It is also interesting to note that out of the 251 behavioural tests (length of the behaviour vector), only 33 unique behaviours are actually ever recorded (frequency >= 1), the remaining behaviours have frequency 0 in

all of the tests, regardless of malware class or fitness function used.

When comparing the diversity obtained in terms of behavioural and detection signatures of the evolved mutants, we observe that there is more diversity in terms of the behavioural signatures than detection signatures, but that diversity is apparent with respect to both signatures.

- (iii)

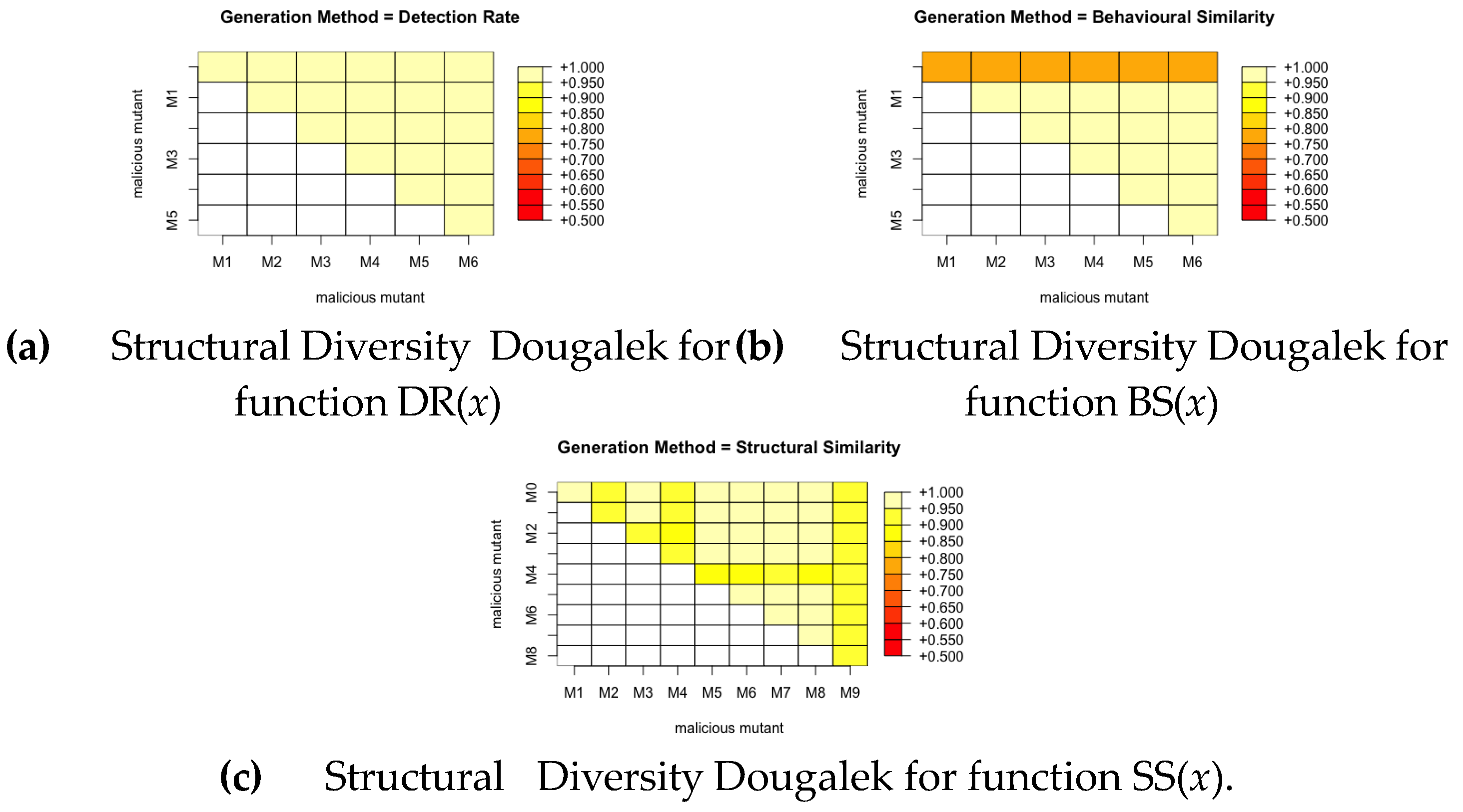

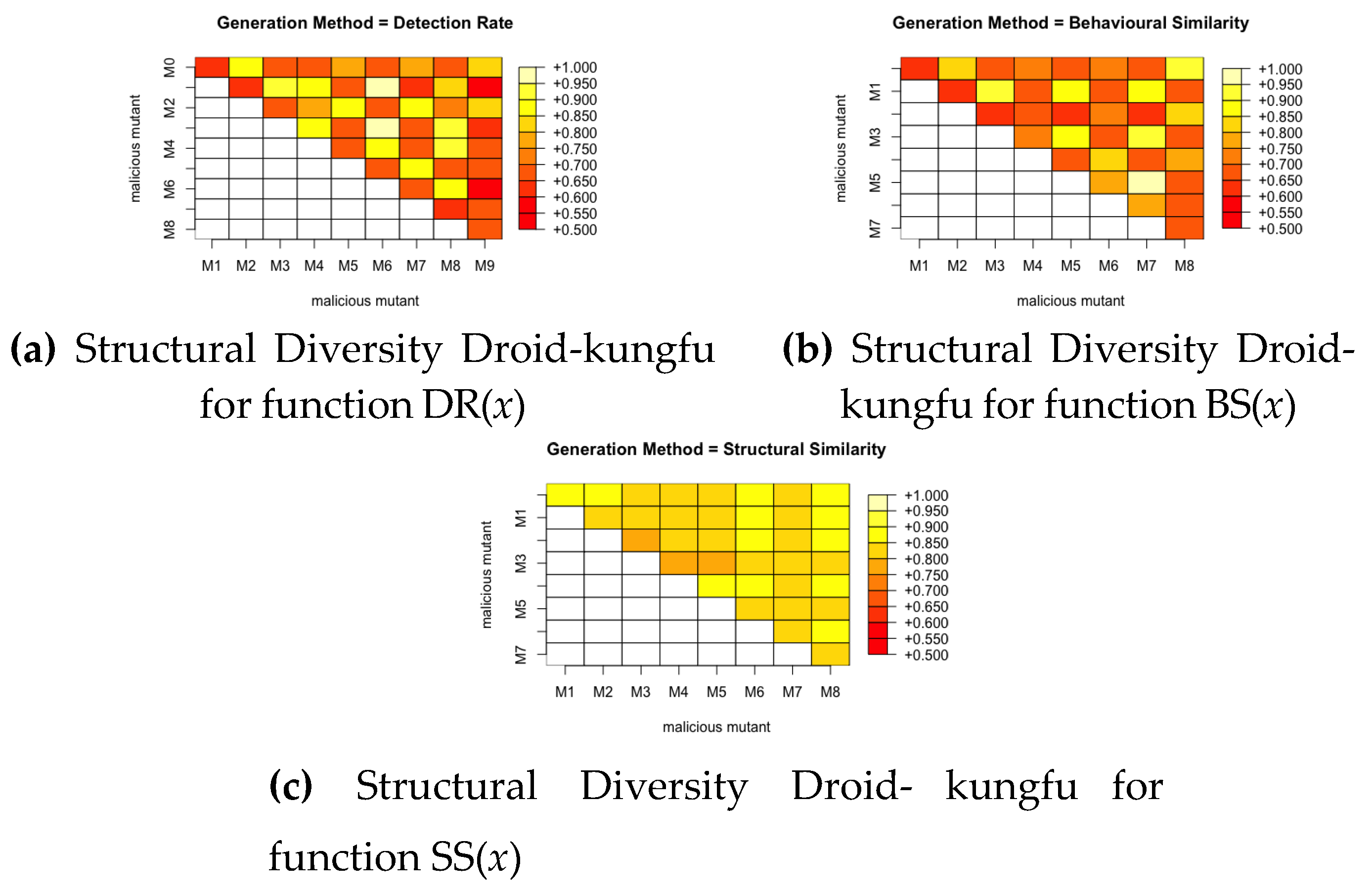

Diversity with respect to structural similarity: We now examine how much diversity is present in a set of evolved mutants with respect to their structural similarity. While evolving using the fitness function SS(x) produces mutants that are dissimilar to the original malware, we also want to generate mutants that are structurally dissimilar to each other in order to maximise diversity in a training set.

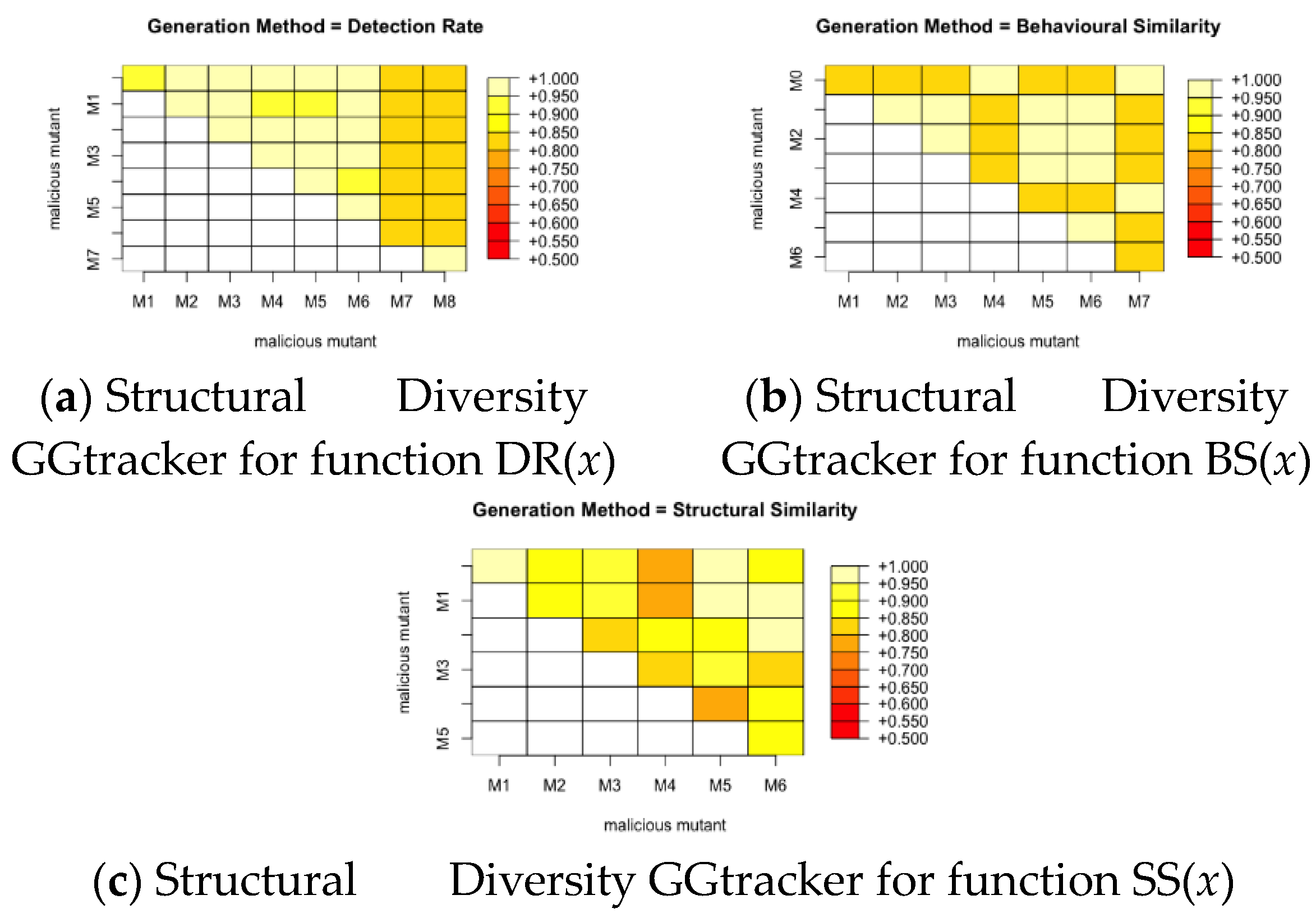

We calculate the pairwise similarity between each pair of mutants produced by a fitness function for all the malware families. This gives a score between 0 and 1, where 0 means the pair are completely different and 1 means they are exactly the same. We then plot this with a colour grid representing the similarity scores of each pair as seen in

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12. It can be noted from these figures that the fitness function that produces the most structurally diverse variants is function SS(

x) for GGtracker family, function BS(

x) for Droidkungfu family and function SS(

x) for Dougalek family. It is interesting to note that the least structurally diverse variants are produced by the Dougalek family and the most structurally diverse variants are produced by the Droidkungfu family.

4.4. Machine Learning - Method

This section seeks answer to our fourth and fifth research questions:

“Which well-known Machine Learning (ML) models are improved more significantly, when trained with our newly produced mutants, in classification of metamorphic malware?”, and

“Can a transformer, such as Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) that has been trained on large Natural Language Processing

(NLP) datasets, be used in a transfer learning context to improve classification of metamorphic malware, with our newly produced mutants?”.

Experiments were designed around the three selected ML models, including one feature-based model (Naïve Bayes [

45]) and two sequential models namely, Long-Short- Term-Memory (LSTM) [

46] and Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) [

47].

-

Naïve Bayes is a probability based ML method used for classification tasks. It follows the Bayesian theorem given in (2) below:

The selection of Naïve Bayes was informed by the empirical analysis conducted in our preliminary study [

48]. It is good to note that it is able to learn from small training samples thus, requiring less training time. It is also easy to implement [

49,

50].

- 2.

LSTM is a neural network particularly built for learning long-term dependencies from sequential data. It comprises gates that are capable of holding, recovering and forgetting information over a long period of time [

46]. It is noteworthy that though deep-learning models, like LSTM, have shown their superiority in dealing with time-ordered information in other problem areas, they are less explored in malware detection [

51,

52,

53].

- 3.

BERT was created for the pre-training of deep representations that are bidirectional, from text that are not labelled by taking into consideration, the contextual information of the text by working out both the left and right context of the token. Consequently, the pretrained BERT models can be easily adjusted and tuned with only an extra output layer to produce advanced models for a large number of NLP tasks [

47].

4.5. Machine Learning - Experiment Setup

The implementation of Naïve Bayes from the Scikit- learn libraries and that of LSTM from the Keras

6 library were used to build the detection models for the experiments. A 10-fold cross validation was used to train and validate models. An unseen test-set containing evolved mutant malware was used in testing.

The LSTM and its hyper-parameters were empirically tuned. As a result of its documented success in terms of its accuracy and computational power, “Adam” optimiser [

54] was employed. Batch sizes between 10 and 500 were used, and experimented using either one or two layers of LSTM. Following this, LSTM was chosen with two layers; each layer had 128 neurons. The binary cross entropy function was used as the loss function for the binary classification and sparse categorical cross entropy was used as the loss function for multi-class classification. Moreover, as this problem is a classification problem, a dense output layer comprising one neuron was employed. A sigmoid activation function was used for the binary classification while a softmax activation function was used for multi-class classification. A batch size of 50 was made use of so as to space out the updates of weight. The model was fitted using just three epochs as it speedily over-fitted the problem.

For the implementation of BERT, ktrain

7 - an interface to Keras - was used. In particular, ktrain’s text module was used. Our dataset was loaded using the texts_from_folder function in the text module and was preprocessed using the “bert” model. The pretrained BERT model (based on Google’s multilingual cased pretrained model

8) was loaded using the text_classifier function of the text module and wrapped in ktrain’s learner object. The multilingual cased pretrained model was employed because it fixes normalisation problems in several languages and it is the latest model recommended by Google). The model was then trained using ktrain’s fit_onecycle. As with the LSTM model, a batch size of 50 was made use of so as to space out the updates of weight. The model was fitted using just three epochs as it speedily over-fitted the problem.

Furthermore, the dataset description for the ML experiments, is given below.

To answer the fourth and fifth research questions, a training data set was created, named

6020combo, which comprises 60 benign samples and 60 malicious samples. The 60 benign samples consist of 20 entertainment applications, 20 security applications and 20 communication applications sourced from Google Play [

55]. The 60 malicious samples contain 20 malware from the Dougalek family, 20 malware from the Droidkungfu family and 20 malware from the GGtracker, described above.

In addition, increasing the malicious samples for training is considered by examining 60 benign samples and 157 malicious samples (including 50 from Dougalek family, 55 from the Droidkungfu family and 52 from the GGtracker family). This increased data combination will be referred to as 6050combo.

For testing, dataset was used comprising 27 benign samples, 23 malicious samples (10 Dougalek family, 5 Droid- kungfu family and 8 GGtracker family) for the 6050combo. For the 6020combo, a dataset was used that consists of 27 benign samples, 16 malicious samples (10 Dougalek family, 3 Droidkungfu family and 3 GGtracker family).

4.6. Machine Learning - Results and Analysis

4.6.1. Improving the Classification of Metamorphic Malware Using the Evolved Mutant

In this section, experiments are carried out to analyse what ML models are better in classifying metamorphic malware by augmenting training data with the evolved variants created using the EA described as well as a Quality Diversity EA described in [

56].

A comparison is done between binary class (benign and malicious classes) and multi-class (benign and the three malicious families - Dougalek, Droidkungfu and GGtracker) classifiers for both a sequential (LSTM) and non-sequential (Naive Bayes) ML models to see which model does better in improving the classification accuracy using the evolved data as part of the training set. The experiments done in this section employs the

6020combo and

6050combo data sets described in

Section 4.1.

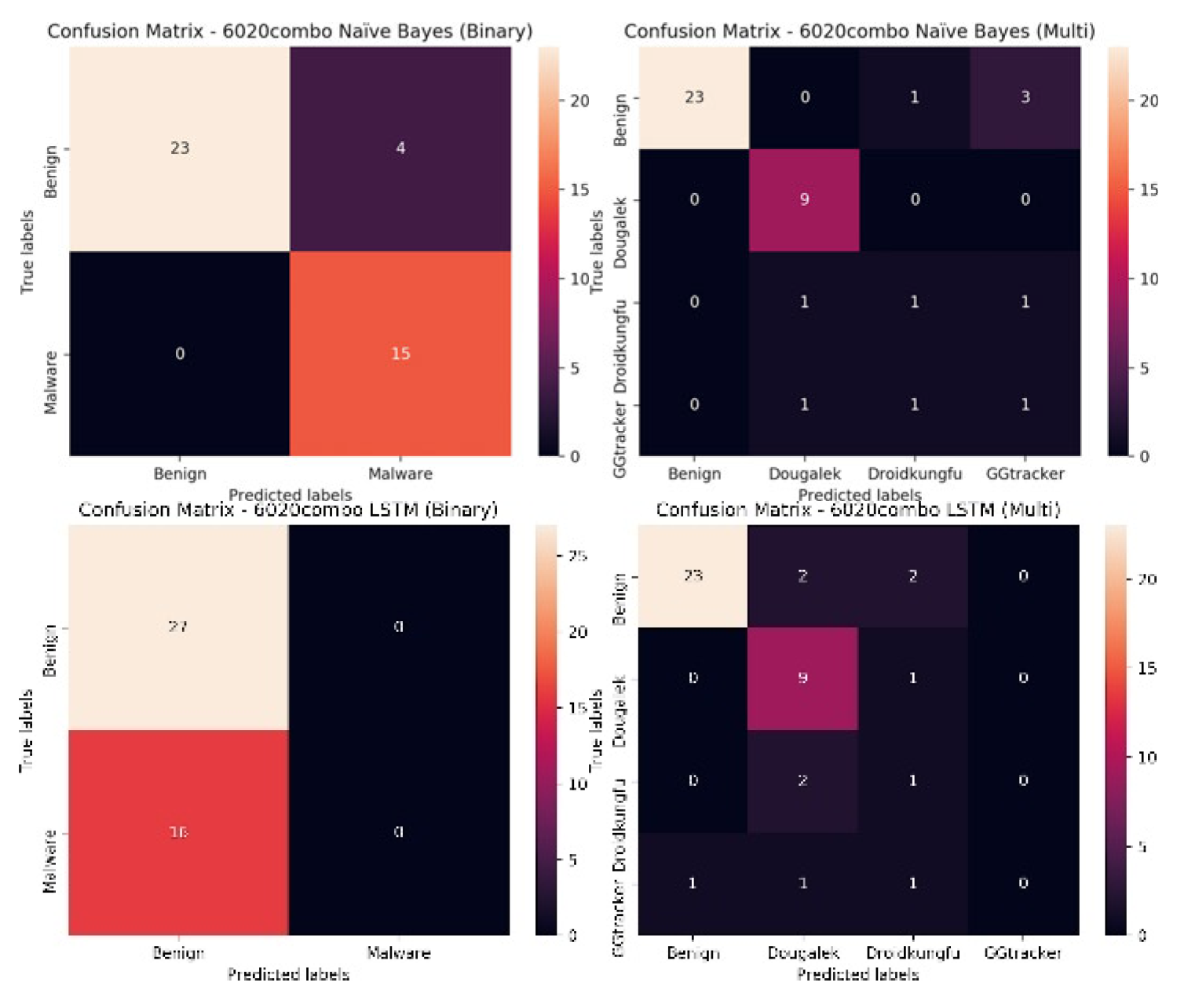

The results are given in

Table 5. It can be seen that for the

6020combo and for the Naïve Bayes model, binary classification outperforms the multi-class classification. However, for the LSTM model, the multi-class model does better than the binary one. It can also be seen that the Naïve Bayes model does better than the LSTM model for both binary and multi- class classification.

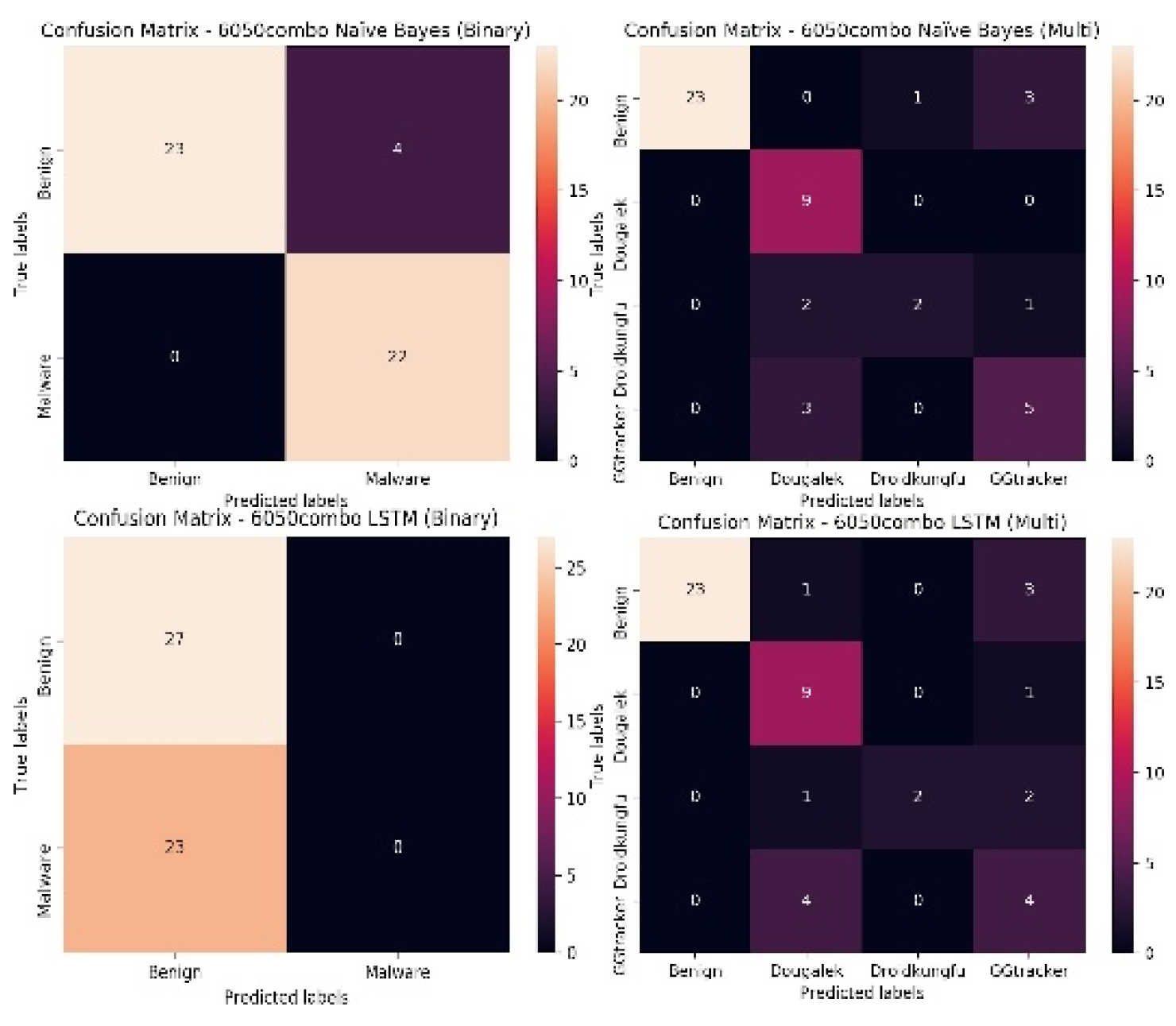

From

Table 5, it can be seen that for the

6050combo and for the Naïve Bayes model, the binary classification outperforms the multi-class classification. However, for the LSTM model, again the multi-class model does better than the binary one. It can also be seen that the Naïve Bayes model does better than the LSTM model for both binary and multi- class classification.

A look at the confusion matrices of both the

6020combo and

6050combo models give more insight to the classifiers. It can be seen from

Figure 13, the illustration for the

6020combo, that the first set of confusion matrices are for the Naïve Bayes model, for the binary model it can be seen that it classifies 23 of the benign instances correctly and four of the benign instances incorrectly, However for the malicious instances, it classifies all of the instances correctly. For the multi-class classification however, 23 of the benign instances are classified correctly, one instance is misclassified as belonging to the Droidkungfu family while three instances are misclassified as belonging to the GGtracker family. It classifies all the Dougalek family correctly. However, it classifies only one of the Droidkungfu instances correctly and misclassifies two of the Droidkungfu instances as belonging to the Dougalek and GGtracker families. Similar observations are seen for the GGtracker family, it classifies only one of the GGtracker instances correctly and misclassifies two of the GGtracker instances as belonging to the Dougalek and Droidkungfu families.

For the LSTM model, for the binary classifier, it classifies all the 43 instances as benign instances (27 instances are classified correctly while 16 malware instances are mis- classified as benign instances). For the multi-class classification, 23 of the benign instances are classified correctly, two instances are misclassified as belonging to the Dougalek family while two instances are misclassified as belonging to the Droidkungfu family. It classifies nine of the Dougalek family correctly and misclassifies one instance as belonging to the Droidkungfu family. However, it classifies only one of the Droidkungfu instance correctly and misclassifies two of the Droidkungfu instances as belonging to the Dougalek family. For the GGtracker family, it classifies none of the GGtracker instances correctly and misclassifies one of the GGtracker instances as belonging to the benign family, one instance is misclassified as belonging to the Dougalek family while one instance is misclassified as belonging to the Droidkungfu family.

For the

6050combo, it can be observed from

Figure 14, that like the confusion matrix for the

6020combo, the first set of confusion matrices are for the Naïve Bayes model, for the binary model it can be seen that it classifies 23 of the benign instances correctly and four of the benign instances incorrectly, however for the malicious instances, it classifies all of the instances correctly. For the multi-class classification however, 23 of the benign instances are classified correctly, one instance is misclassified as belonging to the Droidkungfu family while three instances are misclassified as belonging to the GGtracker family. It classifies all the Dougalek family correctly. However, it classifies two of the Droidkungfu instances correctly and misclassifies three of the Droidkungfu instances as belonging to the Dougalek (2) and GGtracker(1) families. For the GGtracker family, it classifies five of the GGtracker instances correctly and misclassifies three of the GGtracker instances as belonging to the Dougalek family.

For the LSTM model, for the binary classifier, it classifies all the 50 instances as benign instances (27 instances are classified correctly while 23 malware instances are misclassified as benign instances). For the multi-class classification, 23 of the benign instances are classified correctly, one instance is misclassified as belonging to the Dougalek family while three instances are misclassified as belonging to the GGtracker family. It classifies nine of the Dougalek family correctly and misclassifies only one instance as belonging to the GGtracker family. It classifies two of the Droidkungfu instances correctly and misclassifies three of the Droidkungfu instances as belonging to the Dougalek(1) and GGtracker(2) families. For the GGtracker family, it classifies four of the GGtracker instances correctly and misclassifies four of the GGtracker instances as belonging to the Dougalek family.

It can be observed from

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 that the models are generally good at classifying the benign samples. Also, for the binary classification, though the Naïve Bayes model is good at distinguishing between the benign and malicious instances, the LSTM model struggles to distinguish between the benign and malicious instances (it misclassifies all the malicious instances as being benign for both the

6020 and

6050 data sets). For the multi-class classification, though the binary classification does better for the Naïve Bayes model for both the

6020 and

6050 dataset, the multi-class classifiers are still generally good at classifying the various classes for both data sets. For the LSTM model on the other hand, the use of multi-class classification improves the classification accuracy for both the

6020 and

6050 data sets and outperforms the binary classifiers. The multi-class classifiers are more capable of distinguishing between the various malicious groups and the benign instances. The misclassified instances for the various malicious groups by the multi-class classification, emanate from the fact that a number of these groups have overlapping functions (for instance the Dougalek and GGtracker families both steal personal information from mobile phone users) as such their system call vectors are similar making it more difficult for the classifier to distinguish between them.

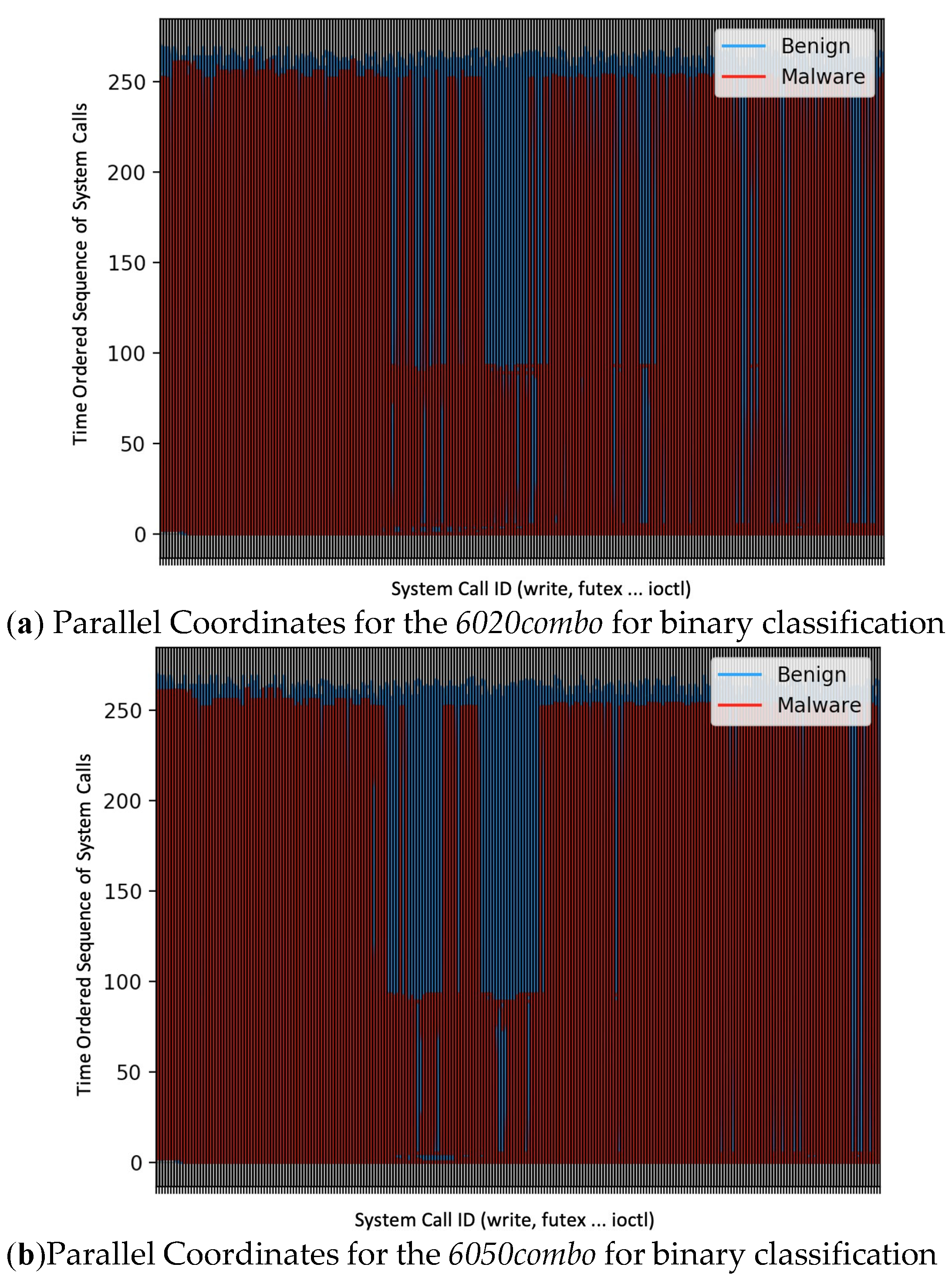

It can be seen from the parallel coordinates (a visualisation tool for highly dimensional data which shows the relationship between features [

57]) in

Figure 15, which is used to explain why the binary classifiers struggle to distinguish between the benign and malicious instances for both the

6020 and

6050 data sets for the LSTM model (that is, using the time ordered sequence of system calls), that although it can be seen that the benign samples are blue and the malicious samples are red for both data sets, there still seems to be an overlap in the plot between the benign and malicious groups which is possibly the reason why the LSTM model struggles to distinguish between the benign and malicious instances. Note that the

x-axis of the parallel coordinates plot is the variable which in this instance is the system call ID. The

y-axis of the parallel coordinates plot usually represents the coordinate value which in this case is the time ordered sequence of system calls.

4.6.2. Improving Classification Performance Using a Transformer — BERT (Pretrained on Large NLP Data Sets) Using the Evolved Mutants

In this section of the paper, the research question, “Can a transformer — BERT (that has been trained on large NLP datasets), be used in a transfer learning context to improve classification of metamorphic malware using the evolved samples?”, is answered. The results are given in

Table 6. It is observed if the use of a transformer — BERT can improve the ML model’s classification performance. The performance of the Naïve Bayes, LSTM and BERT models are compared using the

6020combo and the

6050combo data sets.

From the results given in

Table 6, it is seen that for the

6020combo, BERT performs the best for the binary classification with an accuracy of 93%, an improvement to the Naïve Bayes model (91%) and the LSTM model (63%). For the multi-class classification, however, the Naïve Bayes model performs the best with an accuracy of 81% followed closely by the BERT and LSTM model which have the same accuracy of 77%.

For the 6050combo, the binary classification results show that both BERT model and the Naïve Bayes model perform really well with the Naïve Bayes model producing an accuracy of 92% which is higher than the BERT model’s 90% accuracy. The LSTM model performs the least with a 54% accuracy. The results of the multi-class classification however, has BERT performing the least with a 50% accuracy as opposed to an 80% accuracy for the Naïve Bayes model and a 76% accuracy for the LSTM model.

5. Conclusion and Future Work

In this paper we have described the full end-to-end method for generating novel adversarial examples from already existing malware and using them to improve training of ML models. In other words, the goal was to generate a diverse set of new, malicious, mutants that evade detection by existing detection algorithms, where diversity is measured with respect to the structural and behavioural similarity of the mutants to the original malware. Using examples from three different malware families as a test-bed, we have shown that the new variants generated are significantly more evasive than the original malware they were derived from, and display a diverse range of behaviours. The findings indicate that incentivizing the evolutionary algorithm to produce mutants that exhibit structural or behavioral dissimilarity from the original malware inadvertently leads to the generation of evasive mutants. Thus, it appears that explicit evolution for evasiveness is not a prerequisite; rather, high-quality mutants that possess evasive characteristics can be derived indirectly through this approach.

Furthermore, we have shown that the mutants created using the EA can be used to train better machine learning models having extended existing data-sets with the new samples generated by the method proposed. By comparing the classification performance of the multi-class and binary ML models, we have shown that the binary models mostly outperform the multi-class models in classifying the evolved mutants. The results also show that the use of BERT, an NLP model pretrained on large NLP data sets, leads to an improved classification of metamorphic malware in some test scenarios.

The proposed framework is generic enough to be applied in generating new adversarial samples from any class of malware. There is scope for improving the EA used, for example in developing further mutation operators or methods of crossover that will result in runnable APKs; further tuning of the algorithm parameters is also likely to yield improvements. However, we believe this represents an important first step in methods to automatically generate large sets of adversarial samples. More interesting results can potentially be obtained if the EA described can be combined in a setting typical in Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN [

24]) in which improvements in the generated samples drive improvements in the detection method and vice versa. This may further improve the classification performance of metamorphic malware.

References

- CrowdStrike, “CrowdStrike 2024 Global Threat Report,” Tech. Rep., 2024.

- SOPHOS, “Sophos 2024 Threat Report: Cyberthreats to small busi- nesses are expanding beyond ransomware. Here’s what you need to know,” Tech. Rep., 2024.

- ——, “Sophos 2022 Threat Report: Gravitational Force of Ran- somware Black Hole Pulls in Other Cyberthreats to Create One Massive, Interconnected Ransomware Delivery System,” Tech. Rep., 2022.

- W. Wong and M. Stamp, “Hunting for metamorphic engines,” Journal in Computer Virology, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Z. H. Zuo, Q. X. Zhu, and M. T. Zhou, “On the time complexity of computer viruses,” IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, vol. 51, no. 8, pp. 2962–2966, 2005. [CrossRef]

- F-secure, “2014 Mobile Threat Report,” p. 9, 2014.

- D. Maiorca, D. Ariu, I. Corona, M. Aresu, and G. Giacinto, “Stealth attacks: An extended insight into the obfuscation effects on Android malware,” Computers and Security, vol. 51, pp. 16–31, 2015. [CrossRef]

- D. Lowd and C. Meek, “Adversarial learning,” in Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2005.

- A. E. Eiben and J. E. Smith, “What is an Evolutionary Algorithm?” in Introduction to Evolutionary Computing. Springer Publishing Company, Incorporated, 2003, pp. 15–35.

- K. O. Babaagba, Z. Tan, and E. Hart, “Nowhere metamorphic mal- ware can hide - a biological evolution inspired detection scheme,” in Dependability in Sensor, Cloud, and Big Data Systems and Applica- tions, G. Wang, M. Z. A. Bhuiyan, S. De Capitani di Vimercati, and Y. Ren, Eds. Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2019, pp. 369–382.

- ——, “Improving classification of metamorphic malware by aug- menting training data with a diverse set of evolved mutant samples,” in 2020 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), 2020, pp. 1–7.

- K. O. Babaagba, “Application of evolutionary machine learning in metamorphic malware analysis and detection,” PhD thesis, Edinburgh Napier University, 2022, available from Edinburgh Napier University Repository. [Online]. [CrossRef]

- J. Lee, “COMPRESSION-BASED ANALYSIS OF METAMOR-PHIC MALWARE,” Ph.D. dissertation, San Jose State University, 2013.

- S. P. Choudhary and M. D. Vidyarthi, “A Simple Method for De- tection of Metamorphic Malware using Dynamic Analysis and Text Mining,” Procedia Computer Science, vol. 54, pp. 265–270, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Y. Qu and K. Hughes, “Detecting metamorphic malware by using behavior-based aggregated signature,” 2013 World Congress on In- ternet Security, WorldCIS 2013, pp. 13–18, 2013.

- D. Baysa, R. M. Low, and M. Stamp, “Structural entropy and meta- morphic malware,” Journal in Computer Virology, vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 179–192, 2013.

- S. E. Armoun and S. Hashemi, “A general paradigm for normalizing metamorphic malwares,” in 2012 10th International Conference on Frontiers of Information Technology, Dec 2012, pp. 348–353.

- M. Zheng, P. P. C. Lee, and J. C. S. Lui, “Adam: An automatic and extensible platform to stress test android anti-virus systems,” in Detection of Intrusions and Malware, and Vulnerability Assessment, U. Flegel, E. Markatos, and W. Robertson, Eds. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2013, pp. 82–101.

- V. Rastogi, Y. Chen, and X. Jiang, “Droidchameleon: Evaluating android anti-malware against transformation attacks,” in Proceedings of the 8th ACM SIGSAC Symposium on Information, Computer and Communications Security, ser. ASIA CCS ’13. New York, NY, USA: ACM, 2013, pp. 329–334.

- M. S. Nawaz, P. Fournier-Viger, M. Z. Nawaz, G. Chen, and Y. Wu, “Metamorphic malware behavior analysis using sequential pattern mining,” in Machine Learning and Principles and Practice of Knowl- edge Discovery in Databases. Cham: Springer International Pub- lishing, 2021, pp. 90–103.

- B. Bashari Rad, M. Masrom, S. Ibrahim, and S. Ibrahim, “Morphed Virus Family Classification Based on Opcodes Statistical Feature Using Decision Tree,” in Informatics Engineering and Information Science, A. Abd Manaf, A. Zeki, M. Zamani, S. Chuprat, and E. El- Qawasmeh, Eds. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2011, pp. 123–131.

- A. H. Toderici and M. Stamp, “Chi-squared Distance and Metamor- phic Virus Detection,” J. Comput. Virol., vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1–14, feb 2013.

- A. K. Jha, A. Vaish, and S. Patil, “A novel framework for metamorphic malware detection,” SN Computer Science, vol. 4, no. 1, p. 10, 2022. [Online]. [CrossRef]

- I. Goodfellow, J. Pouget-Abadie, M. Mirza, B. Xu, D. Warde-Farley, S. Ozair, A. Courville, and Y. Bengio, “Generative adversarial nets,” in Advances in neural information processing systems, 2014, pp. 2672–2680.

- E. Aydogan and S. Sen, “Automatic Generation of Mobile Malwares Using Genetic Programming,” Applications of Evolutionary Compu- tation, pp. 745—-756, 2015.

- W. Xu, Y. Qi, and D. Evans, “Automatically Evading Classifiers - A Case Study on PDF Malware Classifier,” Ndss, vol. 2016, no. February, 2016.

- D. Javaheri, P. Lalbakhsh, and M. Hosseinzadeh, “A novel method for detecting future generations of targeted and metamorphic malware based on genetic algorithm,” IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 69 951–69 970, 2021. [CrossRef]

- APKTOOL, “APKTOOL,” 2018. [Online]. Available: http: //ibotpeaches.github.io/Apktool.

- The-Honeynet-Project, “Droidbox,” 2011. [Online]. Available: https://www.honeynet.org/taxonomy/term/191.

- Hiddenforblindreview1, “Details withheld to preserve blind review.”.

- Y. Fang and J. Li, “A review of tournament selection in genetic programming,” in Advances in Computation and Intelligence, Z. Cai, C. Hu, Z. Kang, and Y. Liu, Eds. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2010, pp. 181–192.

- D. Heres, “Source Code Plagiarism Detection using Machine Learn- ing,” Ph.D. dissertation, Utrecht University, 2017.

- J. Lehman and K. O. Stanley, “Novelty Search and the Problem with Objectives,” 2011.

- J. Gomes, P. Mariano, and A. L. Christensen, “Novelty-driven coop- erative coevolution,” Evol. Comput., vol. 25, no. 2, p. 275–307, Jun. 2017.

- T. Vidas, “Contagio Mobile – Mobile Malware Mini Dump,” 2015. [Online]. Available: http://contagiominidump.blogspot.com/ 2015/01/android-hideicon-malware-samples.html.

- Y. Zhou and Jiang Xuxian, “Android Malware Genome Project,” 2012. [Online]. Available: http://www.malgenomeproject.org/.

- Y. Zhou and X. Jiang, “Dissecting Android malware: Characterization and evolution,” in Proceedings - IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, 2012.

- F-Secure, “Trojan:Android/DroidKungFu.C,” 2019.

- ——, “Trojan:Android/GGTracker.A,” 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.f-secure.com/v-descs/trojan{_}android{_}ggtracker. shtml.

- TRENDMICRO, ”ANDROIDOS_DOUGALEK.A,” 2012. [Online]. Available: https://www.trendmicro.com/vinfo/us/ threat-encyclopedia/malware/androidos{_}dougalek.a.

- W. H.Gomaa and A. A. Fahmy, “A Survey of Text Similarity Ap- proaches,” International Journal of Computer Applications, 2013.

- A. Dhakal, A. Poudel, S. Pandey, S. Gaire, and H. P. Baral, “Exploring deep learning in semantic question matching,” in 2018 IEEE 3rd In- ternational Conference on Computing, Communication and Security (ICCCS), Oct 2018, pp. 86–91.

- C. Ragkhitwetsagul, J. Krinke, and D. Clark, “A comparison of code similarity analysers,” Empirical Software Engineering, 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. Van Der Maaten, “Accelerating t-SNE using tree-based algo- rithms,” Journal of Machine Learning Research, vol. 15, pp. 3221– 3245, 2015.

- G. I. Webb, Naïve Bayes. Boston, MA: Springer US, 2010, pp. 713– 714.

- A. Graves, Supervised Sequence Labelling. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2012, pp. 5–13.

- J. Devlin, M. Chang, K. Lee, and K. Toutanova, “BERT: pre- training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understand- ing,” CoRR, vol. abs/1810.04805, 2018.

- Hiddenforblindreview2, “Details withheld to preserve blind review.”.

- C. Bielza and P. Larrañaga, “Discrete bayesian network classifiers: A survey,” ACM Comput. Surv., vol. 47, no. 1, Jul. 2014.

- V. K. A and G. Aghila, “A survey of naïve bayes machine learning approach in text document classification,” 2010.

- R. Lu, “Malware detection with lstm using opcode language,” arXiv:1906.04593, 2019.

- G. E. Dahl, J. W. Stokes, L. Deng, and D. Yu, “Large-scale malware classification using random projections and neural networks,” in 2013 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, May 2013, pp. 3422–3426.

- J. Saxe and K. Berlin, “Deep neural network based malware de- tection using two dimensional binary program features,” in 2015 10th International Conference on Malicious and Unwanted Software (MALWARE), Oct 2015, pp. 11–20.

- D. P. Kingma and J. Ba, “Adam: A method for stochastic optimiza- tion,” CoRR, vol. abs/1412.6980, 2014.

- Google, “Google Play,” 2020. [Online]. Available: https: //play.google.com/store?hl=en.

- K. O. Babaagba, Z. Tan, and E. Hart, “Automatic generation of adversarial metamorphic malware using map-elites,” in Applications of Evolutionary Computation, P. A. Castillo, J. L. Jiménez Laredo, and F. Fernández de Vega, Eds. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020, pp. 117–132.

- J. Johansson and C. Forsell, “Evaluation of parallel coordinates: Overview, categorization and guidelines for future research,” IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, vol. 22, pp. 1–1, 11 2015. [CrossRef]

Short Biography of Authors

Kehinde O. Babaagba (Member, IEEE) obtained a First Class BSc (Hons) in Computer Science from Redeemers University, Nigeria, and an MSc in Computing Information Engineering (Distinction) from Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen, UK. She completed her PhD in Computing at Edinburgh Napier University, Edinburgh, UK under the supervision of Dr. Zhiyuan Tan and Professor Emma Hart in 2020. Currently, she is a Lecturer at the School of Computing, Engineering and the Built Environment at Edinburgh Napier University. Her recent research focuses on transfer learning, computer vision, generative adversarial networks, and other machine learning applications in cyber- security with several papers to her account.

Zhiyuan Tan studied computer systems at the University of Technology Sydney, Australia, and obtained his doctorate in 2014. He then worked as a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Twente, The Netherlands, between 2014 and 2016. He joined the School of Computing, Engineering and the Built Environment at Edinburgh Napier University, UK, as a Lecturer in 2016 and has been an Associate Professor since 2021. His research focusses primarily on cybersecurity, machine learning, and cognitive computation. He is an Associate Editor of IEEE Transaction on Reliability, IEEE Open Journal of the Computer Society, and the Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing. He is also an Academic Editor of Security and Communication Networks. He has coauthored over 120 academic papers.

Figure 1.

Adversarial learning framework.

Figure 1.

Adversarial learning framework.

Figure 2.

The Mutation Engine module that uses an EA The specific details of the software components used in this research are given below. The original malware used to evolve variants is packaged as an apk file. This is disassembled using apktool to obtain a smali2 file (the assembly language used by the Android Dalvik Virtual Machine). The smali file is derived from the decompilation of the .dex file from apk.

Figure 2.

The Mutation Engine module that uses an EA The specific details of the software components used in this research are given below. The original malware used to evolve variants is packaged as an apk file. This is disassembled using apktool to obtain a smali2 file (the assembly language used by the Android Dalvik Virtual Machine). The smali file is derived from the decompilation of the .dex file from apk.

Figure 3.

The percentage of detectors that failed to recognise the novel variants over the x runs that are still malicious, using each of the fitness functions for Dougalek family, with the red line showing the percentage of detectors that failed to recognise the original malware.

Figure 3.

The percentage of detectors that failed to recognise the novel variants over the x runs that are still malicious, using each of the fitness functions for Dougalek family, with the red line showing the percentage of detectors that failed to recognise the original malware.

Figure 4.

The percentage of detectors that failed to recognise the novel variants over the x runs that are still malicious, using each of the fitness functions for Droidkungfu family, with the red line showing the percentage of detectors that failed to recognise the original malware.

Figure 4.

The percentage of detectors that failed to recognise the novel variants over the x runs that are still malicious, using each of the fitness functions for Droidkungfu family, with the red line showing the percentage of detectors that failed to recognise the original malware.

Figure 5.

The percentage of detectors that failed to recognise the novel variants over the x runs that are still malicious, using each of the fitness functions for GGtracker family, with the red line showing the percentage of detectors that failed to recognise the original malware.

Figure 5.

The percentage of detectors that failed to recognise the novel variants over the x runs that are still malicious, using each of the fitness functions for GGtracker family, with the red line showing the percentage of detectors that failed to recognise the original malware.

Figure 6.

Frequency f of detectors d that failed to detect the malware (0 < f < 10) for the fitness functions (DR(x), BS(x) and SS(x)) for Dougalek family.

Figure 6.

Frequency f of detectors d that failed to detect the malware (0 < f < 10) for the fitness functions (DR(x), BS(x) and SS(x)) for Dougalek family.

Figure 7.

Frequency f of detectors d that failed to detect the malware (0 < f < 10) for the fitness functions (DR(x), BS(x) and SS(x)) for Droidkungfu family.

Figure 7.

Frequency f of detectors d that failed to detect the malware (0 < f < 10) for the fitness functions (DR(x), BS(x) and SS(x)) for Droidkungfu family.

Figure 8.

Frequency f of detectors d that failed to detect the malware (0 < f < 10) for the fitness functions (DR(x), BS(x) and SS(x)) for GGtracker family.

Figure 8.

Frequency f of detectors d that failed to detect the malware (0 < f < 10) for the fitness functions (DR(x), BS(x) and SS(x)) for GGtracker family.

Figure 9.

Clustering of the detection vector associated with each evolved mutant, shown according to the fitness function used to evolve the mutant. Dimensionality reduction and clustering performed using t-SNE.

Figure 9.

Clustering of the detection vector associated with each evolved mutant, shown according to the fitness function used to evolve the mutant. Dimensionality reduction and clustering performed using t-SNE.

Figure 10.

Analysis of Structural Diversity for Dougalek.

Figure 10.

Analysis of Structural Diversity for Dougalek.

Figure 11.

Analysis of Structural Diversity for Droid- kungfu.

Figure 11.

Analysis of Structural Diversity for Droid- kungfu.

Figure 12.

Analysis of Structural Diversity for GGtracker.

Figure 12.

Analysis of Structural Diversity for GGtracker.

Figure 13.

Confusion matrices for the 6020combo for both Naïve Bayes and LSTM models for both binary and multi- class classification.

Figure 13.

Confusion matrices for the 6020combo for both Naïve Bayes and LSTM models for both binary and multi- class classification.

Figure 14.

Confusion matrices for the 6050combo for both Naïve Bayes and LSTM models for both binary and multi- class classification.

Figure 14.

Confusion matrices for the 6050combo for both Naïve Bayes and LSTM models for both binary and multi- class classification.

Figure 15.

Parallel Coordinates for the 6020combo and 6050combo for binary classification.

Figure 15.

Parallel Coordinates for the 6020combo and 6050combo for binary classification.

Table 1.

Parameter settings for Evolutionary Algorithm.

Table 1.

Parameter settings for Evolutionary Algorithm.

| Parameters |

Values |

| Selection |

Tournament Selection, k=5 |

| Population Size |

20 |

| Iterations |

100 |

Table 2.

Count of malicious variants returned from 10 runs of the EA under each of the 3 fitness functions.

Table 2.

Count of malicious variants returned from 10 runs of the EA under each of the 3 fitness functions.

| Fitness Function |

Dougalek |

Droidkungfu |

GGtracker |

| DR(x) |

7 |

10 |

9 |

| BS(x) |

7 |

9 |

8 |

| SS(x) |

10 |

9 |

7 |

Table 3.

Percentage of evolved malicious variants that have a unique detection signature, shown by fitness function used to evolve.

Table 3.

Percentage of evolved malicious variants that have a unique detection signature, shown by fitness function used to evolve.

| |

Dougalek |

Droidkungfu |

GGtracker |

| Detection |

43 |

90 |

78 |

| Behavioural Similarity |

71 |

89 |

50 |

| Structural Similarity |

50 |

33 |

29 |

Table 4.

Percentage of evolved malicious variants that have a unique behavioural signature, shown by fitness function used to evolve.

Table 4.