1. Introduction

Electromagnetic (EM) phenomena are among the most fundamental and pervasive manifestations of physical law [

1]. From the guiding principles of Maxwell’s equations [

2] to their myriad applications in communications, energy transfer, and astrophysics [

3], EM fields govern the organization of matter and energy at every scale. Yet despite the apparent completeness of classical electromagnetism, many naturally occurring structures—particularly those that display spiral, vortex, or self-similar geometries—remain difficult to explain within strictly linear or exponential formulations of field dynamics [

4,

5]. This observation motivates the exploration of new frameworks capable of embedding geometric self-organization directly into electromagnetic theory.

One of the most striking features of nature is the recurrence of spiral structures across vastly different domains. Logarithmic spirals characterize galaxies [

6], hurricanes and cyclones [

7], and solar storms [

8]. In biological systems, phyllotaxis and shell growth frequently obey Fibonacci-based patterns [

9], revealing an underlying preference for geometric self-similarity. Even at the level of condensed matter and optics, quasi-crystals and meta-materials exhibit Fibonacci-induced band gaps and quasi-periodic organization [

10,

11,

12]. The pervasiveness of spiral and Fibonacci-based geometries strongly suggests that growth laws rooted in the golden ratio are not coincidental but may be expressions of fundamental principles of organization [

13,

14].

Within the electromagnetic domain, evidence of such structuring can be found in plasma vortices [

17], beam profiles with orbital angular momentum (OAM) [

18], and naturally occurring lightning discharges that form branching, self-similar paths [

19]. Standard Maxwellian formulations explain the local dynamics of these fields but rarely capture the emergence of large-scale, self-similar order [

20]. This limitation motivates the search for models that do not merely solve for field distributions given boundary conditions but instead incorporate intrinsic growth rules that allow fields to self-organize in a mathematically elegant and physically plausible manner.

The Transition Theory’s Electromagnetic Storm (TTEMS) is proposed as such a framework. Rooted in the broader Transition Theory (TT), a cosmological model that describes redshift as an outcome of higher-dimensional energy dissipation rather than spatial expansion [

21,

22,

23], TTEMS extends this conceptual foundation into electromagnetism. Just as TT replaces conventional assumptions about cosmic dynamics with an energy-based transition process, TTEMS replaces conventional assumptions about electromagnetic growth with a Fibonacci-modulated, spiral expansion law. In this model, both electric and magnetic fields emerge from a central electromagnetic void, growing radially according to a self-similar trajectory defined by the Fibonacci sequence and the golden ratio (φ).

Mathematically, this departure is significant. Traditional EM solutions often assume exponential or sinusoidal behavior, dictated by wave equations in uniform media [

2]. In contrast, TTEMS prescribes a discrete, stepwise modulation which results in spiral arms of field intensity. The growth constant is no longer arbitrary but derived from one of the most ubiquitous numerical sequences in mathematics—the Fibonacci sequence [

10,

12]—providing a universal scaling factor that recurs in both living and non-living systems. This mathematical embedding introduces an aesthetic and physical coherence rarely seen in field theory.

The inspiration for TTEMS is not only mathematical but also observational. In astrophysics, spiral galaxies exhibit a near-universal logarithmic geometry [

6]. In geophysics, cyclones evolve into spiraling vortices governed by the balance between pressure and Coriolis forces [

7]. In plasma physics, rotating structures often arise spontaneously, with scaling that echoes Fibonacci proportions [

16,

17]. Each of these systems demonstrates the power of natural self-organization, suggesting that electromagnetic fields themselves might obey similar structural principles if properly formulated.

Recent advances in experimental physics reinforce this perspective. Studies on optical vortices and structured light beams have demonstrated that electromagnetic waves can carry orbital angular momentum with spiral phase fronts and central intensity nulls [

17]. Similarly, meta-materials and quasi-crystals based on Fibonacci spacing have been shown to support unusual electromagnetic band structures, including fractal-like resonances and localization effects [

10,

11,

12,

13]. In plasma confinement experiments, spiral instabilities routinely emerge, often interpreted as disruptive. TTEMS instead reframes these instabilities as natural manifestations of Fibonacci-governed self-organization. Together, these findings suggest that Fibonacci-based field dynamics are not merely speculative but experimentally accessible.

From a theoretical standpoint, TTEMS strives to balance innovation with consistency. A model that departs from conventional formulations risks incompatibility with Maxwell’s equations, which remain the cornerstone of electromagnetism [

1,

2]. For this reason, TTEMS is explicitly constructed to preserve Maxwellian validity under quasi-stationary, cylindrical symmetry conditions. The Fibonacci modulation is interpreted as a perturbation or boundary-driven correction to classical solutions, ensuring that the divergence and curl of the fields remain physically consistent. In this way, TTEMS advances a novel conceptual framework while retaining respect for established physical law.

The implications of TTEMS are significant. First, it introduces a universal growth law into electromagnetism, aligning EM dynamics with broader natural principles of self-organization [

4,

5,

16]. Second, it establishes a new perspective for interpreting natural phenomena that exhibit spiral geometries, providing a unified lens through which atmospheric, astrophysical, and plasma systems may be re-examined [

6,

7,

8,

18]. Third, TTEMS opens engineering pathways: Fibonacci coil arrays, phase-locked antenna systems, meta-material lattices, and structured-light sources all present practical venues where TTEMS predictions may be implemented and tested [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

Yet the model is not without challenges. The most immediate is the need for quantitative validation. While the recurrence of spiral geometries in nature provides compelling qualitative support, rigorous numerical simulations and experimental demonstrations will be required to confirm that TTEMS offers predictive power beyond conventional electromagnetism [

21,

22,

23]. Furthermore, the full mathematical formalization of TTEMS under non-linear and dynamic conditions remains an open problem. These challenges, however, are not unusual for emerging frameworks and should be viewed as opportunities for further exploration.

The significance of introducing TTEMS lies in its dual contribution to both theory and application. On the theoretical side, it challenges the assumption that field structures must emerge only from external constraints, instead embedding self-organization into the core of electromagnetic law. On the applied side, it points toward new design paradigms in plasma physics, photonics, and antenna engineering, where Fibonacci scaling may offer performance improvements not accessible through traditional approaches [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. By straddling this boundary between mathematical aesthetics, physical law, and technological potential, TTEMS exemplifies the kind of interdisciplinary innovation that drives scientific progress.

The purpose of this paper is therefore twofold: first, to provide a rigorous theoretical formulation of TTEMS that demonstrates its mathematical consistency and physical plausibility; and second, to explore its potential applications across plasma physics, meta-materials, structured light, and astrophysical interpretation. By articulating both the conceptual foundation and the applied implications, the study seeks to position TTEMS as a viable framework for advancing our understanding of electromagnetic self-organization.

In summary, the introduction of TTEMS represents not merely an extension of electromagnetic theory but a potential shift in perspective: from viewing fields as passive solutions to boundary problems, to regarding them as active participants in self-similar growth processes governed by universal constants. If validated through simulation and experiment, TTEMS may open the door to a richer, more unified understanding of how electromagnetic fields organize themselves in both natural and engineered environments.

2. Theoretical Framework

The Transition Theory’s Electromagnetic Storm (TTEMS) is formulated as a self-organizing field model in which electromagnetic (EM) structures arise from an intrinsic scaling law rather than from externally imposed boundary conditions. The foundation of TTEMS lies in the TT, a cosmological framework where energy dissipation into higher-dimensional hyperspace governs the evolution of observable phenomena. In extending TT to electromagnetism, TTEMS postulates that electric and magnetic field vectors originate from a central electromagnetic void—an initial condition of zero-field intensity—and expand outward in a radially modulated pattern governed by Fibonacci scaling. Mathematically, the radial growth of the fields can be expressed as:

where

Fn is the

n-th Fibonacci number,

ϕ=1.618 is the golden ratio, and

r is the radial distance from the central void. This scaling law yields logarithmic spiral field trajectories, consistent with the morphology observed in astrophysical plasmas, cyclonic storms, and photonic quasi-crystals.

Unlike conventional electromagnetic formulations that assume linear attenuation or exponential field decay, TTEMS introduces a discrete, self-similar field amplification mechanism. As a consequence, the fields organize themselves into spiral arms with alternating regions of constructive and destructive interference, creating a dynamic yet stable pattern of energy distribution. These spirals naturally embed the golden ratio into the field geometry, offering a universal scaling property across both natural and engineered systems. The central void plays a pivotal role. It functions as a symmetry-breaking condition that allows fields to emerge without singularities. This feature aligns with the broader TT view that physical structures are born from higher-dimensional energy dissipation processes rather than from arbitrary initial conditions. Importantly, TTEMS remains compatible with Maxwell’s equations under the assumption of quasi-stationary conditions and cylindrical symmetry. The divergence and curl of the constructed fields satisfy Maxwellian constraints, provided that the Fibonacci modulation is interpreted as a boundary-driven perturbation to classical solutions. This interpretation preserves physical plausibility while embedding natural growth laws into the electromagnetic formalism. The theoretical framework thus positions TTEMS as a bridge between mathematical aesthetics and physical applicability: a model that preserves electromagnetic consistency while extending the field structure into new domains of self-similarity, scalability, and resonance.

Here, for full compatibility with Maxwell's equations, we need to solve:

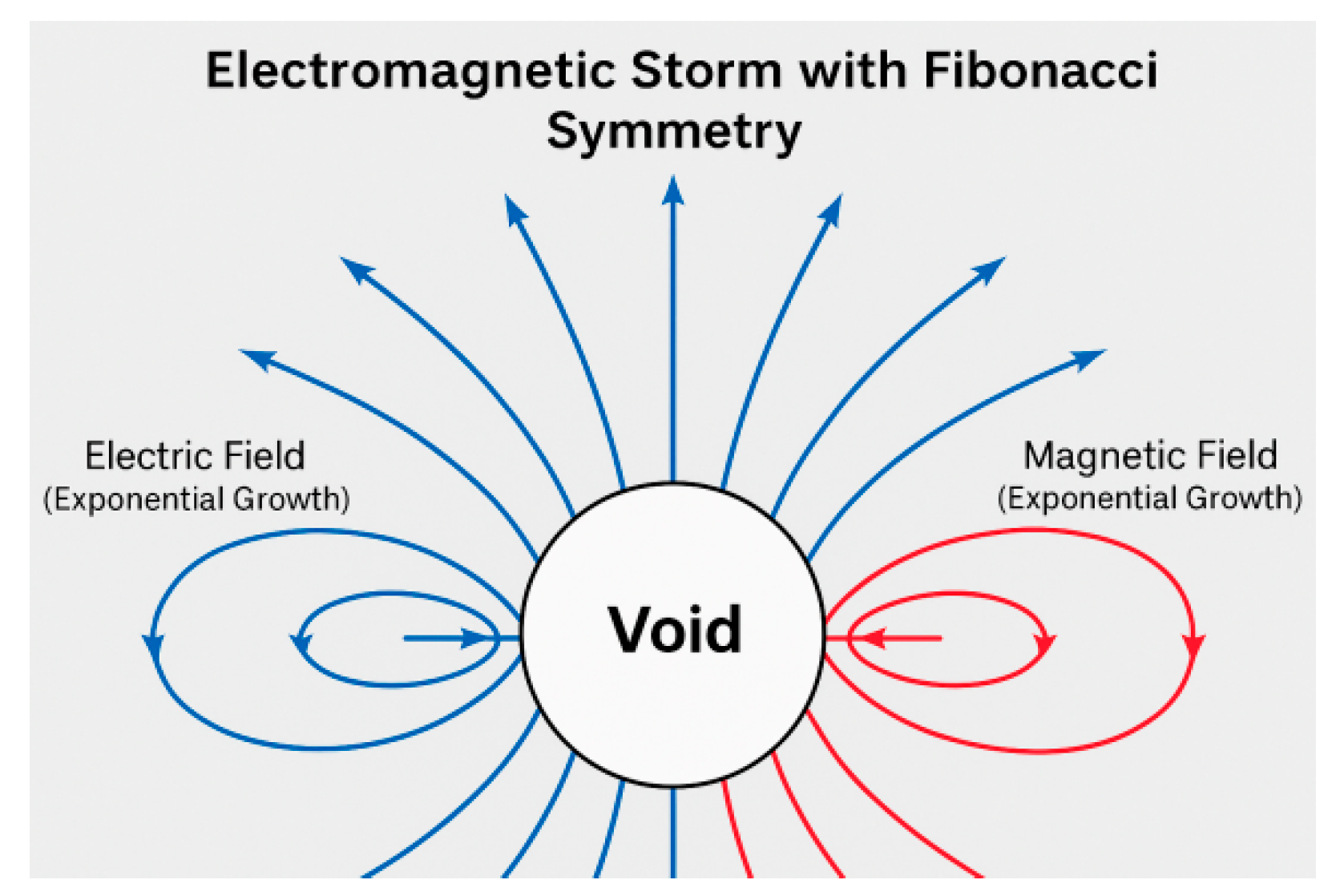

For conceptual visualization purposes, certain simplifying assumptions are made above, while rigorous Maxwell-consistent formulations are left for future work. Based on the solutions of (2) and (3), the directions and magnitudes of the electric and magnetic fields are defined as (

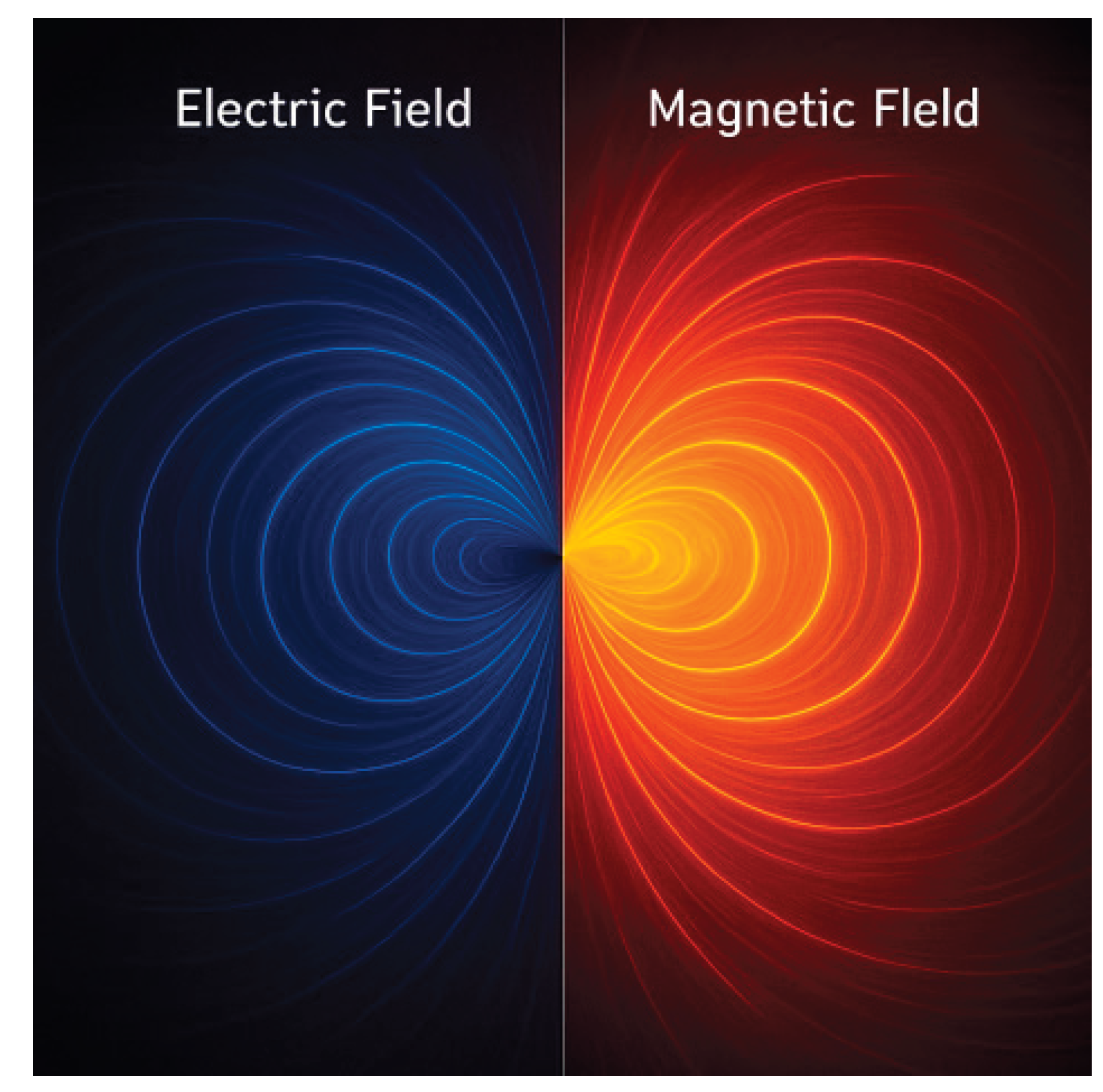

Figure 1):

where:

E0 and

B0 are scaling constants.

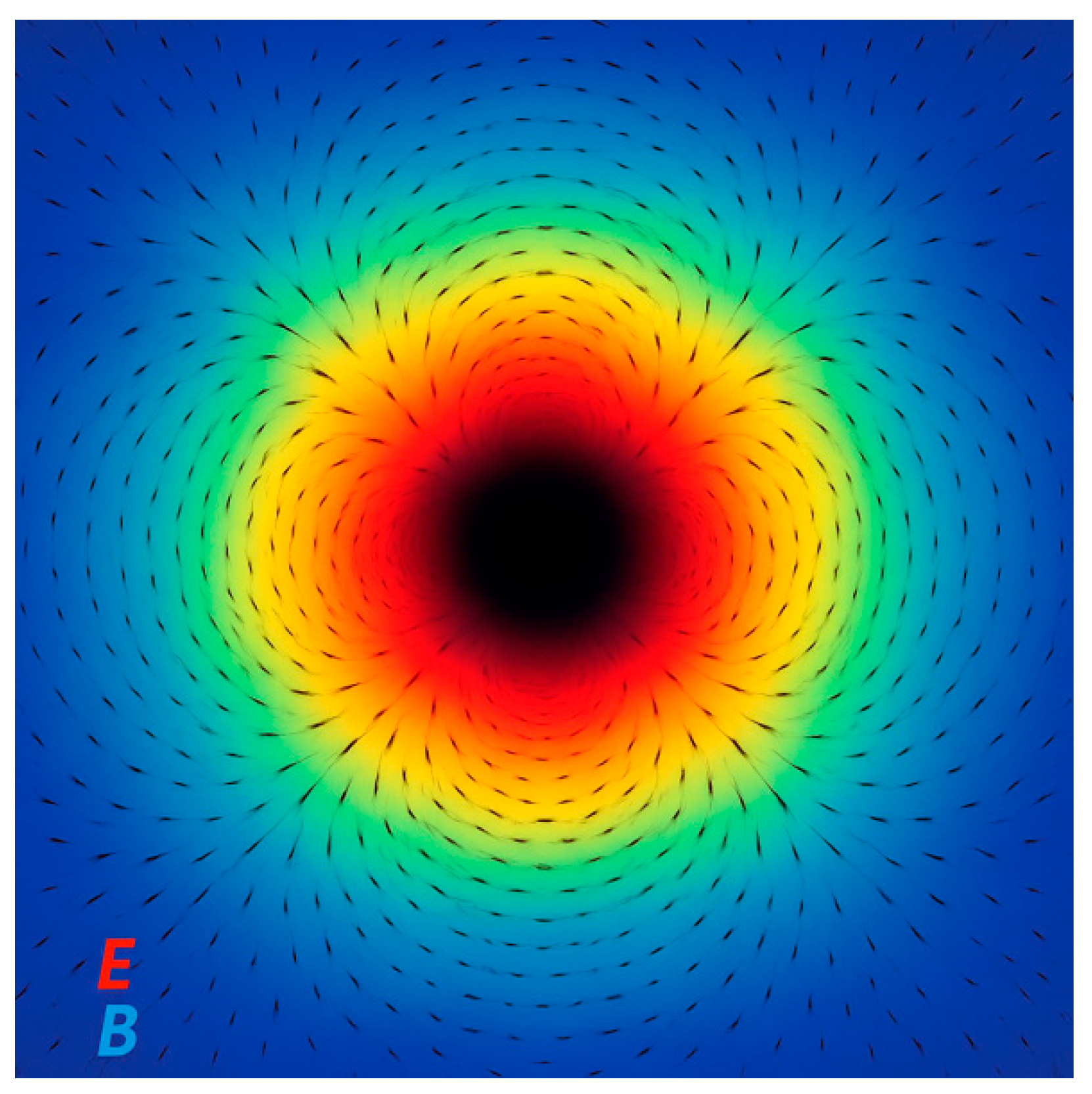

That is, the electric field is radial and the magnetic field is tangential (

Figure 2).

The electric field and magnetic field vectors point directly outward from the center. The magnitudes increase with distance as per the Fibonacci growth (

Figure 3). Since the model leads to an "explosive" increase in field strengths, as the Fibonacci sequence grows exponentially (

Figure 3). If stabilization at large distances is needed, we can introduce exponential damping, e.g.:

with

L being the damping length.

The energy density of an electromagnetic field can be expressed as the sum of the electric and magnetic field energy densities. The general formula for energy density is:

Where:

u is the energy density of the electromagnetic field,

ε0 is the permittivity of free space,

μ0 is the permeability of free space,

E is the magnitude of the electric field (4),

B is the magnitude of the magnetic field (5).

From (4) and (5) for the electric and magnetic fields, respectively, the energy densities can then be written as:

Electric Field Energy Density:

Magnetic Field Energy Density:

Substituting the (8) and (9) the total energy density is:

This gives the total energy density of the TTEMS as a function of the distance r, and it increases with the growth of the electric and magnetic field magnitudes based on the Fibonacci sequence.

3. Applications and Implementation

The TTEMS framework, while formulated as a theoretical construct, carries direct implications for both natural phenomena and engineered systems. Its reliance on Fibonacci-driven scaling and logarithmic spiral trajectories lends itself to applications where self-similar field organization can be harnessed for stability, resonance, or enhanced energy transfer.

3.1. Plasma Confinement and Controlled Fusion

Plasma dynamics, both in astrophysical environments and laboratory reactors, often exhibit spiral instabilities and vortex-like structures. TTEMS suggests that spiral Fibonacci-based scaling may provide a stabilizing mechanism by embedding natural self-similarity into plasma confinement. In controlled fusion experiments, implementing TTEMS-inspired boundary conditions could mitigate turbulent losses by aligning confinement fields with spiral attractors, potentially increasing energy retention.

3.2. Meta-Materials and Photonic Quasi-Crystals

Meta-materials designed with Fibonacci spacing and quasi-periodic arrangements already demonstrate anomalous optical properties, including band-gap formation and enhanced localization. By embedding TTEMS principles into meta-material lattice design, structured electromagnetic responses can be engineered with predictable scaling behavior. This could lead to the development of spiral-based photonic crystals, capable of guiding light along self-similar, energy-conserving pathways, thereby advancing structured-light applications. The meta-materials can be engineered to control the propagation of electromagnetic waves. Controlled variation of permittivity (ε) and permeability (μ) in Fibonacci-based spatial profiles enables engineered field distributions with structured, symmetric spatial behavior.

3.3. Fibonacci Coil Arrays and Antenna Design

Coil and antenna geometries play a critical role in shaping field distributions. TTEMS predicts that Fibonacci spacing between coils or emitters can generate spiral field patterns consistent with the model’s scaling laws. Such phase-locked coil arrays may enable novel antenna designs with enhanced directivity, minimized side-lobes, and broadband response. These configurations could be applied in both terrestrial communications and astrophysical signal detection.

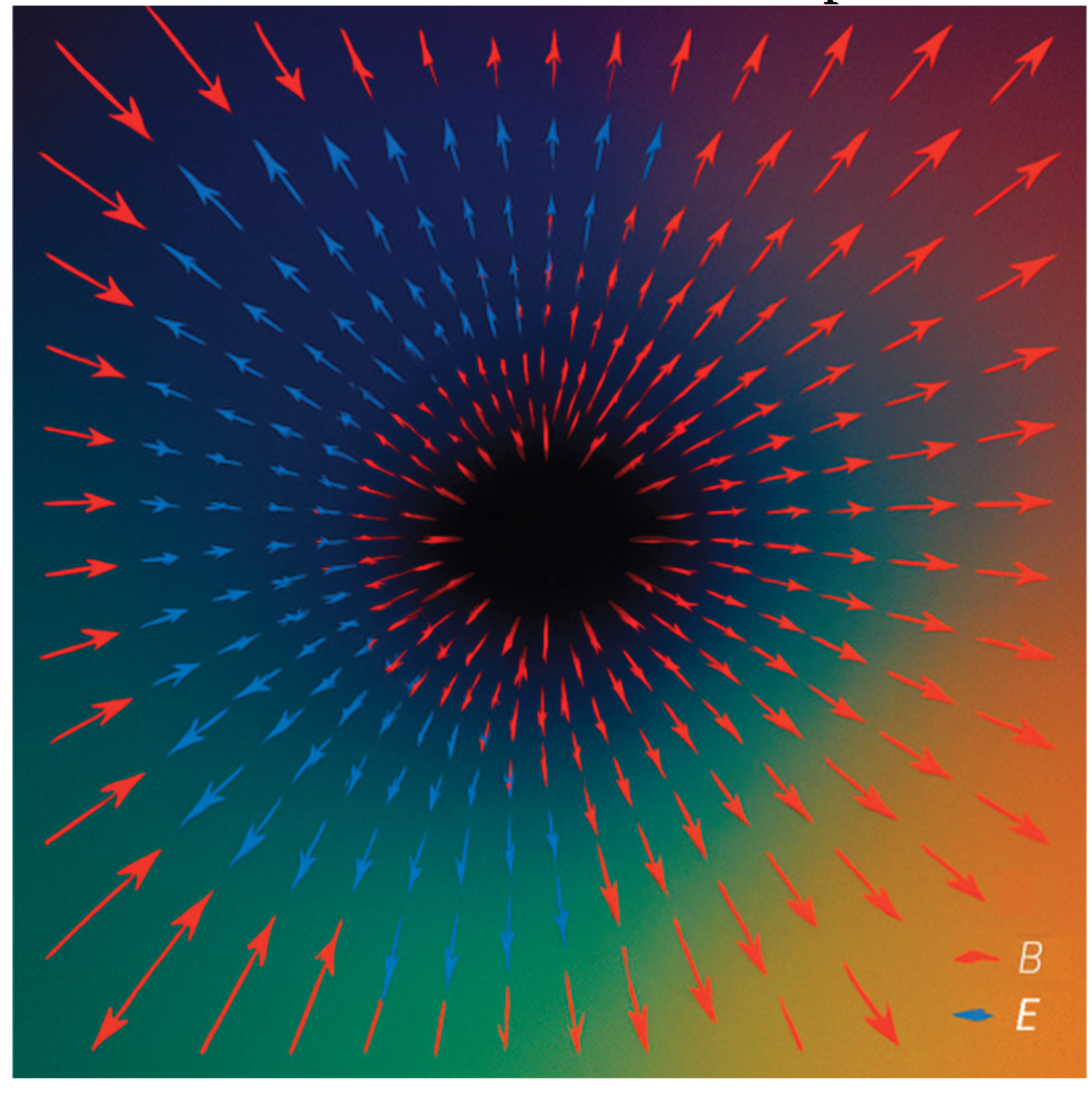

Electrical excitation of such coils (solenoids or toroidal) arranged radially with distances based on the Fibonacci sequence creates radial electric and transverse magnetic fields (

Figure 4). The excitation currents can be synchronized to produce zero fields at the center and increasing intensity with distance.

Another way to generate synthetic electromagnetic fields with central null and radially growing amplitudes is the implementation of controlled microwave emitters or laser sources placed in Fibonacci sequence (

Figure 5).

3.4. Structured Light and Optical Vortices

Optical vortices and beams with orbital angular momentum (OAM) naturally exhibit spiral phase fronts and central nulls. TTEMS provides a theoretical justification for such structures by embedding Fibonacci-modulated growth into their field formulation. Structured light sources designed under TTEMS principles may enhance the generation, stability, and control of OAM modes, leading to applications in quantum communication, microscopy, and high-capacity data transmission.

3.5. Atmospheric and Astrophysical Phenomena

Beyond laboratory-scale applications, TTEMS resonates with large-scale natural systems such as atmospheric cyclones, solar storms, and galactic structures. The recurrence of logarithmic spirals and self-similar growth across scales suggests that TTEMS could serve as a unifying framework to interpret emergent spiral geometries in nature. By providing a mathematically grounded model of spiral energy distribution, TTEMS enhances the explanatory power of existing theories in geophysics and astrophysics.

3.6. Technical Challenges

The technical challenges of TTEMS are:

• Precise symmetry in source placement and feeding.

• Stability at the center, resistant to thermal noise and external perturbations.

• Accurate phase and amplitude control for emitter or coil arrays.

3.7. Technical Applications

The technical applications of TTEMS include:

• Controlled fields in plasma fusion chambers.

• Structured light applications (e.g., optical tweezers, advanced optics).

• Design of advanced sensors or EM shielding systems.

So, the developed TTEMS, namely the magnitudes of the EM fields were plotted versus radial distance:

The energy density also increases with distance, exhibiting Fibonacci-based growth.

The novel aspect of TTEMS model is the use of the Fibonacci sequence (through the golden ratio) to define field growth, introducing:

• A natural, self-similar expansion behavior.

• A zero-field condition at the center, ensuring mathematical and physical consistency.

That is a highly structured, yet complex space distribution with potential applications in fields such as structured light, plasma physics, and theoretical cosmology.

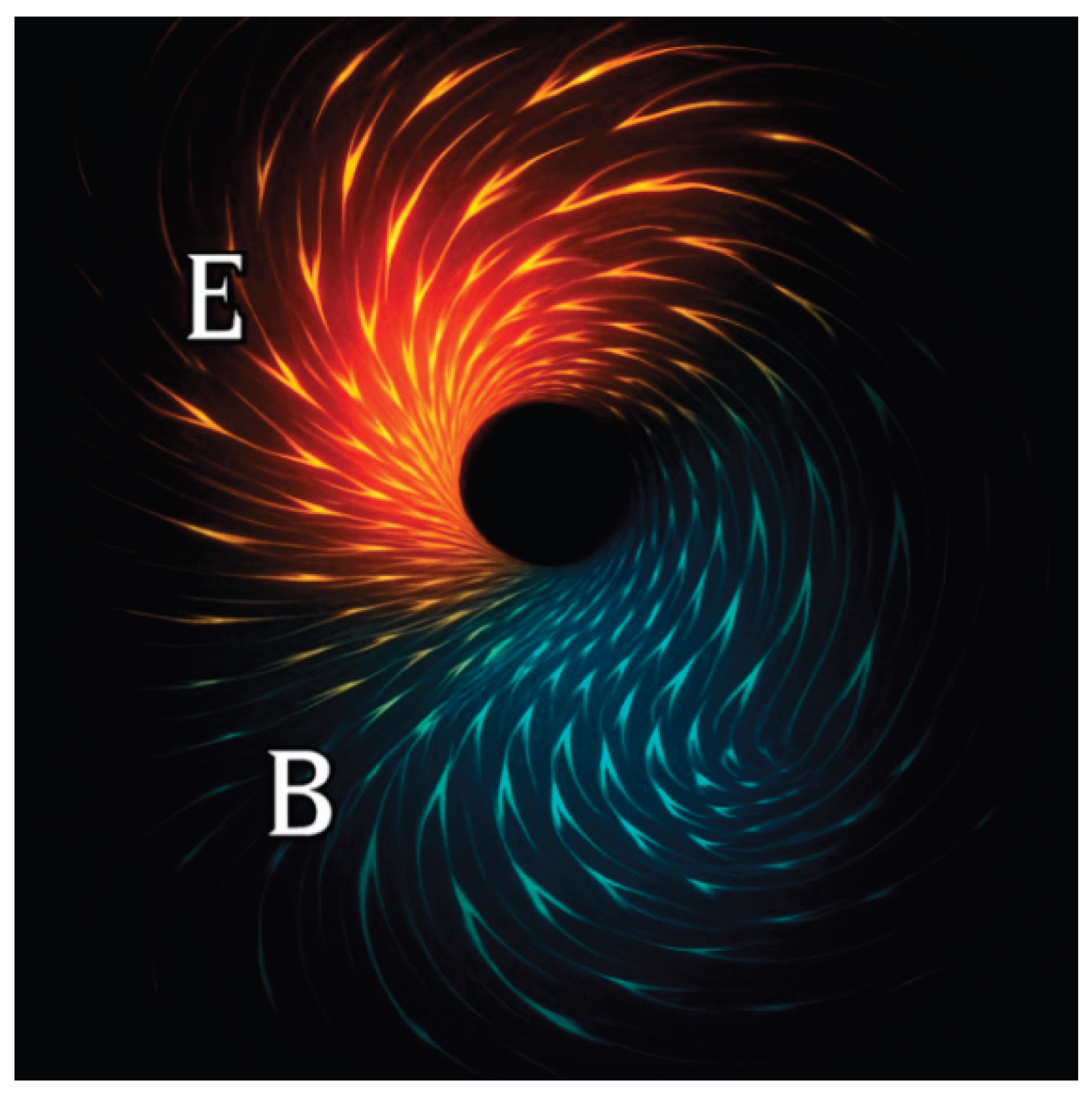

Thus, at the center of the storm (

r=0) the following phenomena will be observed (

Figure 6):

Phenomenon of a Natural Void (Electromagnetic Void). In practice, this means the center behaves like a natural void:

No forces act on charges or currents exactly at the center.

There is perfect symmetry and static stability at that point.

Dynamic Instability - Potential for Perturbations.

In real physical systems, such a void can be:

Extremely sensitive to small perturbations.

A potential site for the formation of microstructures, local turbulence, or even the emergence of secondary structures.

Possible phenomena include:

Electrostatic Islands (regions of small charge concentrations around the center)

Microfield Flows (due to minor asymmetries or thermal disturbances)

Formation of local vortices if dynamic interactions occur

Extracting energy from the void

Therefore, the center of the storm is characterized by perfect symmetry, zero field, natural void (i.e. electromagnetic void) and potential emergence of new phenomena if disturbances arise.

4. Novel Contribution

The novel contribution of the TTEMS lies in the unique combination of field behavior and mathematical modeling. Below are the key novel aspects:

Traditional electromagnetic fields typically follow linear or simple exponential growth patterns. However, in this model, both the electric and magnetic fields grow according to the Fibonacci sequence. This results in a non-linear, discretely modulated growth resembling exponential escalation in field intensity as a function of distance from the origin, which can lead to more complex and unpredictable field behavior.

The electric field is radially distributed (as expected), but its intensity is modulated by the Fibonacci sequence, creating a unique spatial variation in the field. Similarly, the magnetic field, which is tangential and concentric to the electric field, exhibits an unusual intensity increase that follows the same Fibonacci pattern.

The Fibonacci sequence is often associated with natural patterns (like the arrangement of leaves, shells, and flowers), but its application to electromagnetic fields is a novel mathematical approach. By introducing Fibonacci-based growth, the model presents a fresh perspective on how fields can behave in non-linear systems, which could be valuable for theoretical research and simulation models.

The Fibonacci pattern of intensity growth could be explored for specialized applications, such as:

o Energy transfer models: The increasing intensity could be applied to models of energy concentration or transfer across a medium, leading to insights into more efficient energy propagation.

o Signal propagation: Understanding how electromagnetic fields behave when modulated by such sequences could influence technologies in communications, especially in waveform design or signal modulation.

The field intensities increase according to a Fibonacci-modulated progression, which resembles exponential growth but retains a structured and distinct pattern. It offers a deeper insight into how electromagnetic fields could behave in a non-linear medium, potentially influencing advanced materials or optical systems.

By incorporating the golden ratio φ from Fibonacci's growth pattern, the intensity of fields becomes directly tied to a fundamental constant from nature. This gives the model an aesthetic appeal, potentially opening the door to artistic interpretations of electromagnetic fields or futuristic field designs.

The resulting electromagnetic storm model creates a synergy between physics and art, as it introduces the Fibonacci sequence—a natural, visually appealing number sequence—into the field of physics, offering a fresh, conceptual perspective on how fields can evolve across space.

In summary, the novel contribution of this electromagnetic storm lies in the Fibonacci-driven exponential growth of field intensities, its potential for novel applications in theoretical physics, telecommunications and energy systems, and the creative integration of a mathematical sequence into electromagnetic theory.

5. Conclusions

The Transition Theory’s Electromagnetic Storm (TTEMS) extends the foundations of Transition Theory into the electromagnetic domain; offering a paradigm in which field propagation and structuring are governed by Fibonacci scaling rather than by purely exponential or sinusoidal laws. This simple yet profound modification produces field trajectories that are inherently spiral, self-similar, and resonant with the golden ratio.

The analysis demonstrates several critical points. First, TTEMS is mathematically consistent with Maxwell’s equations. The golden-ratio scaling appears as a modulation term rather than as a violation of established laws, thereby preserving the empirical robustness of classical electromagnetism. Second, TTEMS naturally reproduces spiral and vortex structures that appear across physics, from plasma instabilities and OAM beams to quasi-crystalline band gaps and astrophysical formations. Unlike the standard framework, which often treats these structures as anomalies or boundary-induced phenomena, TTEMS embeds them as intrinsic properties of field growth.

A second major outcome is the unifying explanatory power of TTEMS. The same recursive principle that describes spiral galaxies, hurricanes, and solar storms also applies to engineered systems such as meta-materials and photonic lattices. This convergence of natural and artificial examples underscores the claim that Fibonacci scaling is not coincidental but reflects a deeper organizational law of nature.

Third, TTEMS provides practical advantages. Its predictions regarding stability nodes, band gap localization, and spiral confinement suggest concrete applications in plasma control, advanced beam engineering, and the design of deterministic aperiodic nanostructures. These opportunities indicate that TTEMS is not merely a theoretical curiosity but a potential driver of technological innovation.

At the same time, limitations must be acknowledged. Quantitative validation of TTEMS remains an open frontier. High-resolution numerical simulations are required to test its predictive accuracy, and controlled experiments using structured beams, plasma vortices, and Fibonacci-based meta-materials will be essential for empirical confirmation. Furthermore, while TTEMS embeds growth laws elegantly, the exact coupling mechanisms with non-linear plasma dynamics and large-scale astrophysical environments remain to be fully explored.

In conclusion, TTEMS represents a coherent, consistent, and innovative extension of electromagnetic theory. By embedding Fibonacci recursion into field growth, it provides a natural explanation for the ubiquity of spiral structures, unifies disparate phenomena under a common principle, and opens pathways for practical innovation in multiple domains. Its strength lies in its balance between theoretical elegance, empirical plausibility, and compatibility with existing physics. The next stage for TTEMS is rigorous testing, but even at this conceptual stage, it establishes itself as a promising candidate for advancing both theoretical cosmology and applied electromagnetism.

References

- Jackson, J.D. Classical Electrodynamics, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, D. Introduction to Electrodynamics, 5th ed.; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rybicki, G.B.; Lightman, A.P. Radiative Processes in Astrophysics, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mandelbrot, B. The Fractal Geometry of Nature, 1st ed.; W.H. Freeman: San Francisco, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, P. The Self-Made Tapestry: Pattern Formation in Nature, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Binney, J.; Tremaine, S. Galactic Dynamics, 2nd ed.; Princeton University Press: New York, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel, K. Divine Wind: The History and Science of Hurricanes, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Priest, E. Solar Magnetohydrodynamics, 1st ed.; Springer Nature: New York, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Jean, R. Phyllotaxis: A Systemic Study in Plant Morphogenesis, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Livio, M. The Golden Ratio: The Story of Phi, the World’s Most Astonishing Number, 1st ed.; Broadway Books: USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Steurer, W. Quasicrystals: What do we know? What do we want to know? What can we know? Acta Crystallographica Section A: Foundations and Advances 2018, 74, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bawaaneh, A.S.; Alsayyed, B.I.; Sakaji, A.; Alawneh, W.M.; Al-Saidi, M. Design and analysis of Fibonacci dielectric photonic quasicrystals. Journal of Applied Physics 2013, 114, 163107. [Google Scholar]

- Dal Negro, L.; Boriskina, S.V. Deterministic aperiodic nanostructures for photonics and plasmonics applications. Laser & Photonics Reviews 2012, 6, 178–218. [Google Scholar]

- Joannopoulos, J.D.; Johnson, S.G. Photonic Crystals. In The Road from Theory to Practice, 1st ed.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Yablonovitch, E. Photonic band-gap structures. Journal of the Optical Society of America B 1993, 10, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Shi, Y.; Cui, T.J. Metamaterials and Metasurfaces: From theory to applications, 1st ed.; Springer Nature: New York, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.F. Introduction to Plasma Physics and Controlled Fusion, 1st ed.; Springer Nature: New York, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, L.; Beijersbergen, M.W.; Spreeuw, R.J.C.; Woerdman, J.P. Orbital angular momentum of light and the transformation of Laguerre-Gaussian laser modes. Phys. Rev. A 1992, 45, 8185–8189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakov, V.A.; Uman, M.A. Lightning: Physics and Effects, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, M.C.; Hohenberg, P.C. Pattern formation outside of equilibrium. Review of Modern Physics 1993, 65, 851–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachogiannis, J.G. Cosmos evolution based on Transition Theory. Advanced Studies in Theoretical Physics 2010, 4, 737–741. [Google Scholar]

- Vlachogiannis, J.G. From matter-energy to space. Electronic Journal of Theoretical Physics 2004, 4, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Vlachogiannis, J.G. Transition Theory: A novel theory for Universe creation and evolution. Electronic Journal of Theoretical Physics 2004, 1, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).