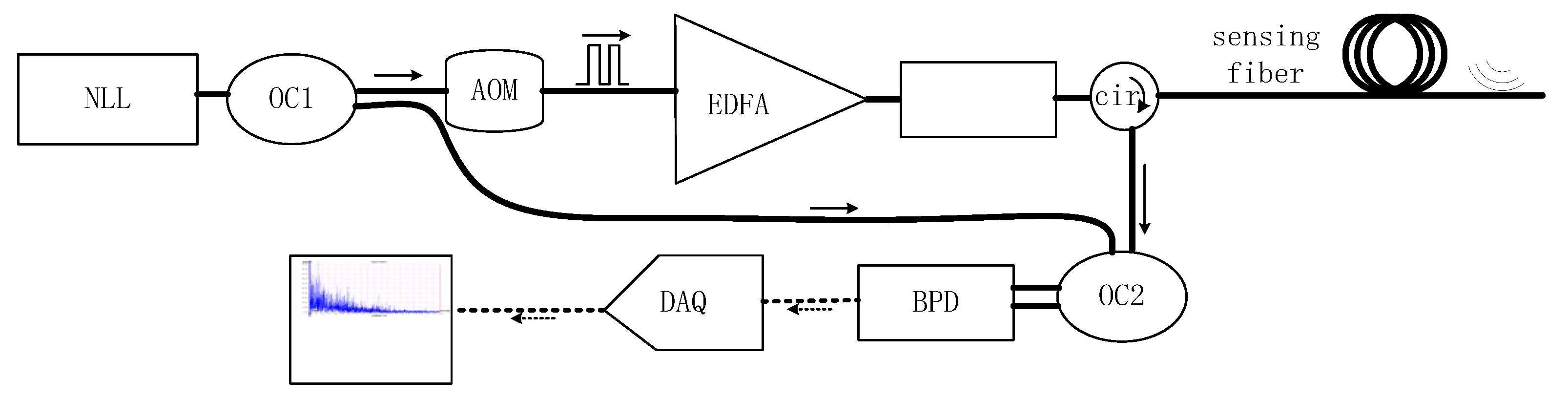

2.1. DVS Based on Heterodyne Coherent Detection Φ-OTDR

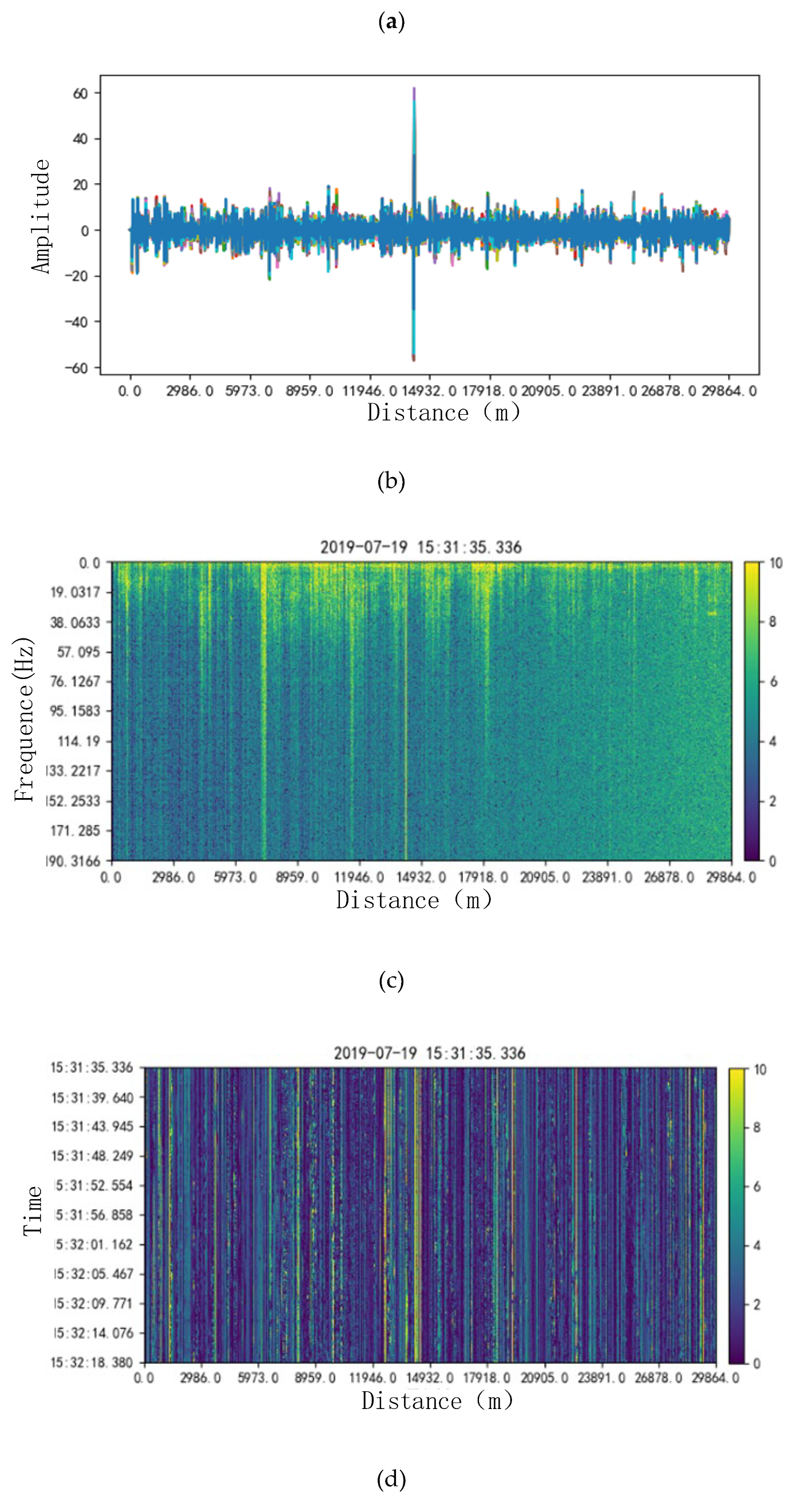

DVS is typically implemented using Phase-sensitive Optical Time-Domain Reflectometry (Φ-OTDR). It injects optical pulses into the optical fiber and demodulates the phase information of the backscattered Rayleigh scattering time-series signals to achieve distributed measurement of vibrations along the fiber [

1,

14,

15]. In this study, a DVS system based on heterodyne coherent detection Φ-OTDR was constructed, as depicted in

Figure 1.

Assuming an equal-intensity probe laser pulse with pulse width

(unit ns) is injected into the sensing fiber of total length

at frequency

, and the data acquisition card’s sampling frequency is

. According to the fundamental principles of heterodyne coherent detection Φ-OTDR [

9], the observation data matrix can be derived:

Here represents the time dimension, denotes the spatial dimension; is the speed of light in the fiber, , is the speed of light in vacuum, is the fiber refractive index; is the detector responsivity; is the probe laser pulse intensity; is the fiber attenuation coefficient; is the optical frequency shift introduced by the acousto-optic modulator; is the phase deviation caused by the reference light; , are the mean amplitude and phase modulation, respectively, of the fiber scattering points within the length interval over the time interval .

Typically, to avoid aliasing of backscattered Rayleigh signals from multiple pulses,

; to ensure vibrations at any point within the monitoring range can be captured by at least one sampling point, avoiding spatial monitoring blind spots,

, i.e.,:

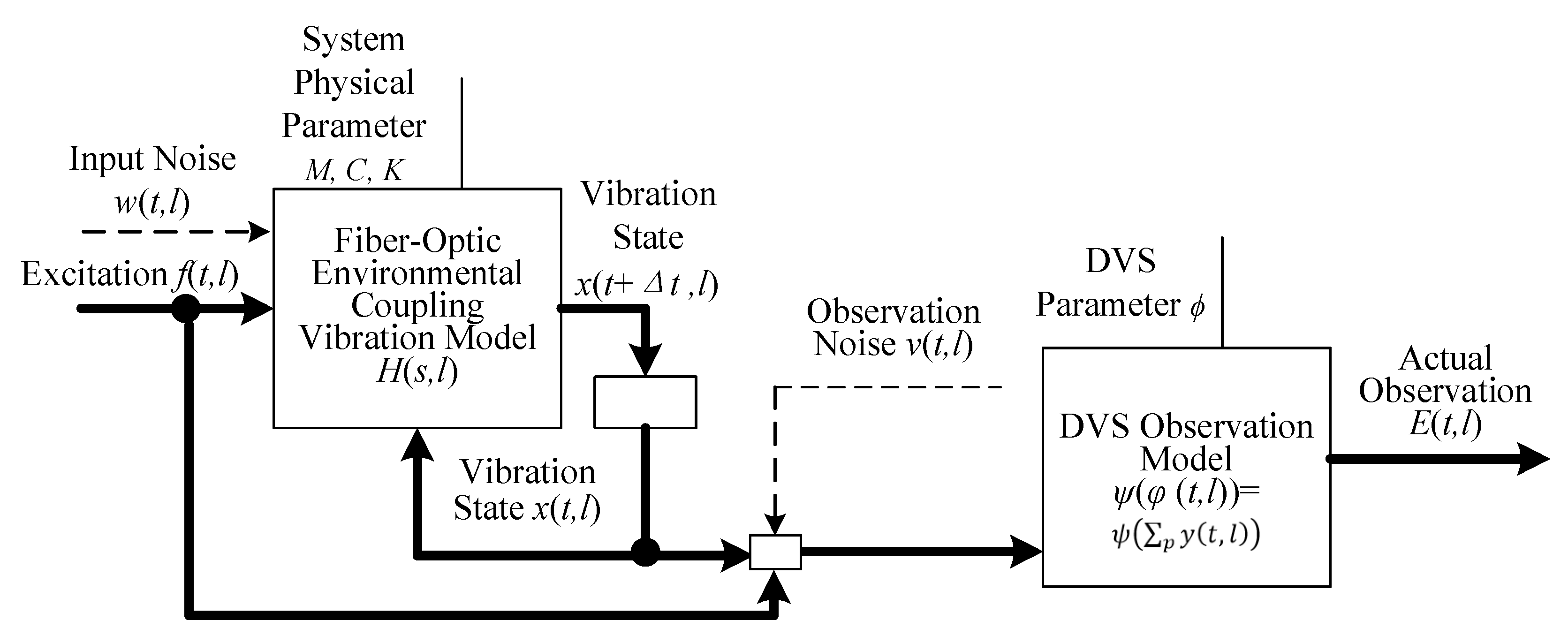

2.2. Fiber-Environment Coupled Vibration Observation Model

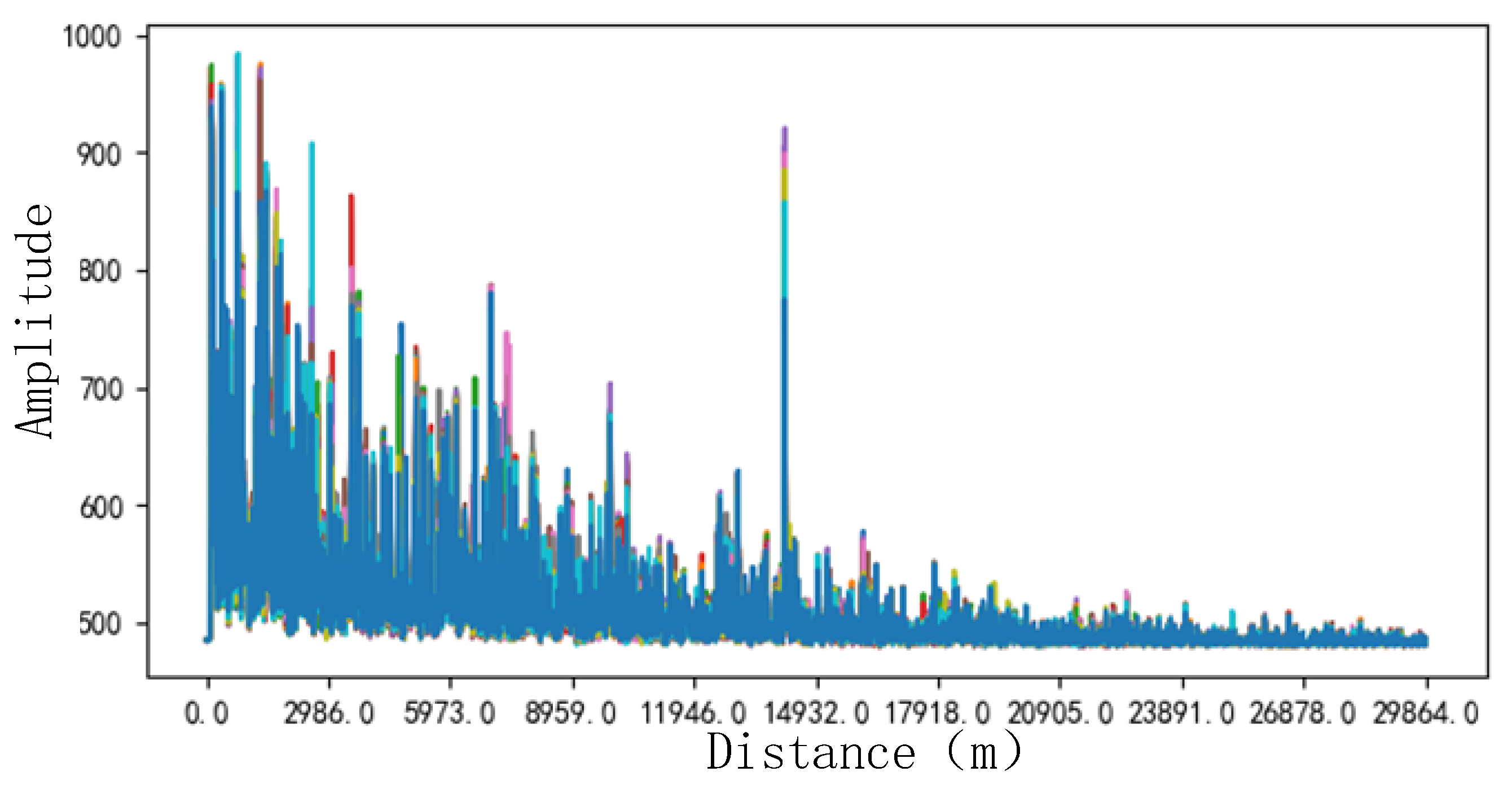

From Eqs. (1) and (2), it can be seen that DVS can monitor vibration signals within the frequency range

at points along the sensing fiber over a length

with a spatial resolution of

(actual resolution

); where

is the lowest observable frequency affected by system noise. Since light transmission in the fiber exhibits exponential attenuation with distance, the amplitude of the observed signal also attenuates exponentially with distance. Its phase reflects the scalar dynamic strain generated by vibration at each fiber point along the axial direction, which differs significantly from the three-dimensional spatial vector vibration signals measured by traditional triaxial accelerometers. Furthermore, different installation methods of the sensing fiber (direct burial/overhead/pipeline/subsea, etc.) result in different forms of vibration coupling with the environment, leading to vibration waves from different incident angles affecting the axial dynamic strain of the fiber to varying degrees, forming an anisotropic response [

2].

Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between the fiber-environment coupled system vibration model and the DVS observation model. Fibers installed in different ways receive characteristic excitations carrying environmental noise, forming a fiber-environment coupled vibration system. Its previous state and the current noisy excitation together influence the noisy observation signal obtained by DVS. Assuming the fiber-environment coupled vibration system at point

$l

$ has

$n

$ degrees of freedom, the above process can be described by Eq. (3) [

16,

17].

Where

represents the discrete time quantity,

represents the discrete spatial quantity;

is the discrete-time state variable,

is the discrete-time state matrix,

is the discrete-time external excitation vector,

is the discrete-time input matrix,

is the system input noise;

is the vibration signal observation (here, the optical path change component at position

at time

in the fiber),

is the discrete-time output matrix,

is the discrete-time direct feedthrough matrix,

is the observation output noise,

is the number of related measurement points, often

in practical DVS systems.

is the phase change at position

at time

in the fiber as shown in Eq. (1),

is as shown in Eq. (1); and:

Where are the mass matrix, damping matrix, and stiffness matrix, respectively.

By assigning values with different distribution characteristics to ,,, and Eq. (3) can conveniently describe the observation models for most practical DVS application scenarios. The aforementioned characteristics of DVS signals determine that in practical applications, we need to adopt methods distinct from traditional vibration signal processing, consider the vibration coupling characteristics of the sensing fiber and the environment, and fully exploit the spatio-temporal correlation of the linear array response sensing signals from DVS to provide appropriate solutions for real-world scenarios.

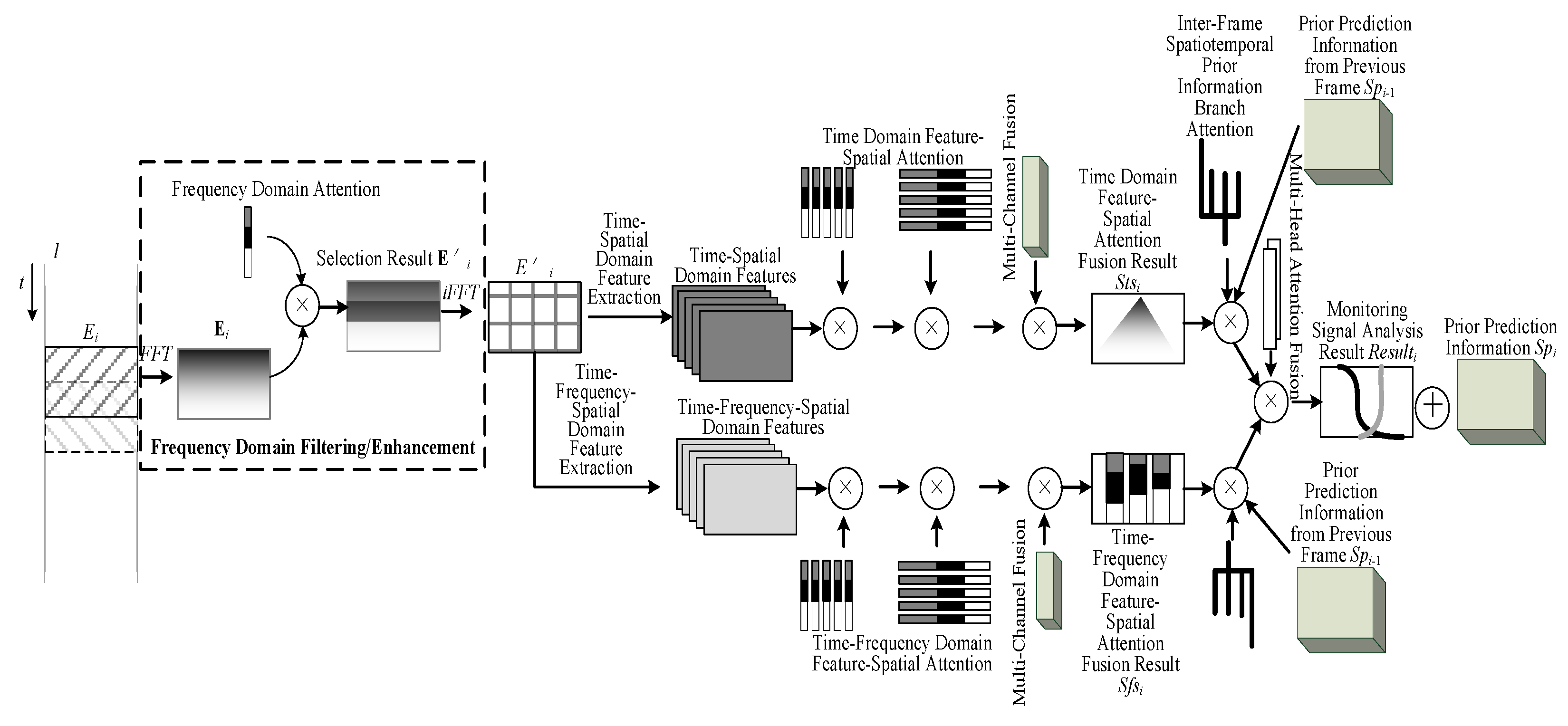

2.3. Application Scenario-Driven Combined Multi-Head Attention Mechanism DVS Signal Analysis

Attention is the process by which the brain filters information and focuses on targets in complex environments. Its essence can be attributed to the selective dynamic allocation of information, optimizing the use of limited cognitive resources to prioritize the processing of key information. The attention mechanism permeates the core processes of brain prediction, decision-making, and learning, achieving closed-loop adaptive optimization of perception-action and the environment through selective information deepening under limited resources [

18]. Recent research has transitioned from traditional behavioral experiments to a new paradigm characterized by “computational modeling, neural mechanisms, and real-world context integration.” By leveraging technological innovation and interdisciplinary collaboration, researchers are better equipped to explore the inherent complexity of cognition.

In this field, attention models simulate the information filtering and resource allocation strategies observed in biological cognitive systems, emerging as a key technological innovation in artificial intelligence. As core components of AI models, they significantly enhance the model’s ability to filter and integrate key information. Their advantages in handling long-range dependencies, multimodal alignment, and interpretable decision-making have driven breakthroughs in fields such as natural language processing, computer vision, and multimodal learning. Existing attention mechanism models mainly include channel attention, spatial attention, temporal attention, branch attention, as well as combined attentions like channel-spatial attention and spatial-temporal attention [

19].

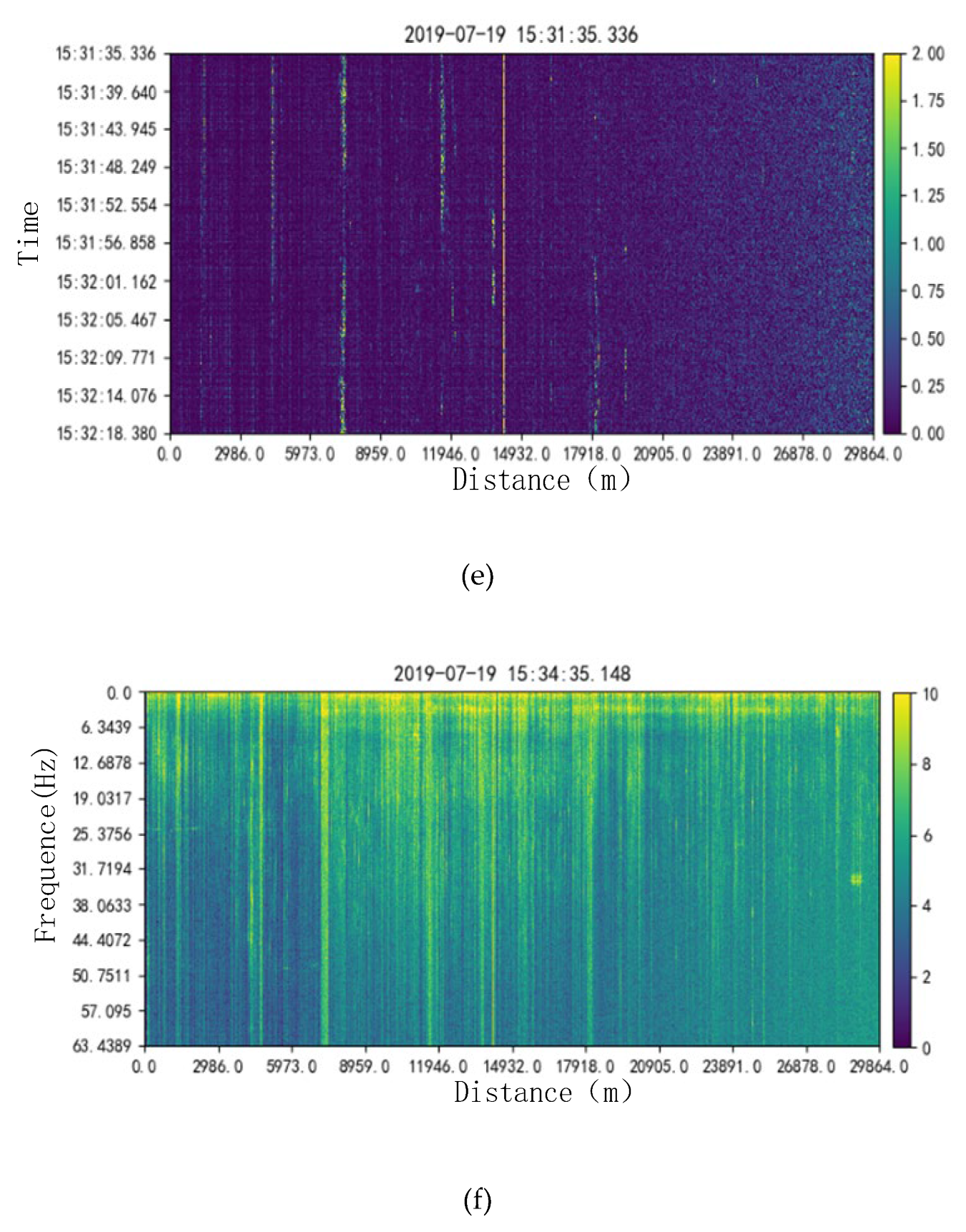

From

Section 2.2., it can be seen that the obtained DVS monitoring signal

contains information such as environmental excitation

, the vibration state

of the cable and its coupled structure, and the fiber-environment coupled vibration

. Guided by the requirements of specific application scenarios, introducing reasonable assumptions to simplify the problem, and comprehensively utilizing related prior knowledge, we can mimic the human attention mechanism to integrate multi-clue information for complex background suppression, multi-feature fusion detection and extraction. This allows limited computational resources to be rapidly focused on appropriate information for processing, providing real-time solutions for specific application scenario problems. Several typical monitoring problem descriptions are given below:

1. Event Detection and Classification. Detect whether the external excitation contains the target excitation distribution corresponding to a specific event. Non-target excitation is treated as background excitation and suppressed within . Differences in the cable and its coupled structure state also need to be eliminated. Further feature extraction and classification are performed on the detected .

2. Vibration State Identification of Cable and its Coupled Structure. Estimate and identify the characteristics and categories of , requiring robustness against interference from different environmental excitations .

3. Detection of Physical Property Changes in Cable and its Coupled Structure. Detect changes in the mass matrix , damping matrix and stiffness matrix of the cable and its coupled structure. This is achieved by identifying physical parameters of the fiber-environment coupled vibration model , requiring adaptation to the influences of different vibration states and different environmental excitations .

Clearly, the target excitation , the vibration state to be detected , and the features of the physical parameter identification fiber-environment coupled vibration model only affect the monitoring signal within certain frequency bands. They exhibit certain characteristics in the time domain, frequency domain, and space domain, and their spatio-temporal distribution usually satisfies certain prior rule constraints.

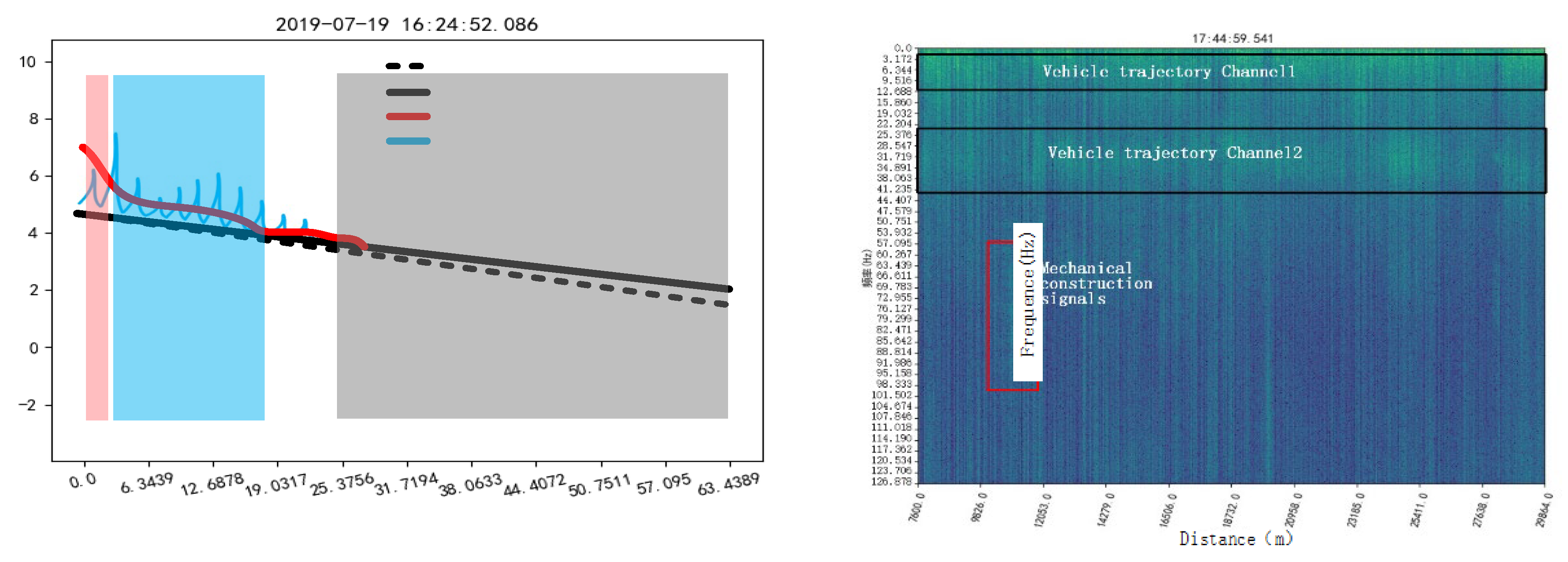

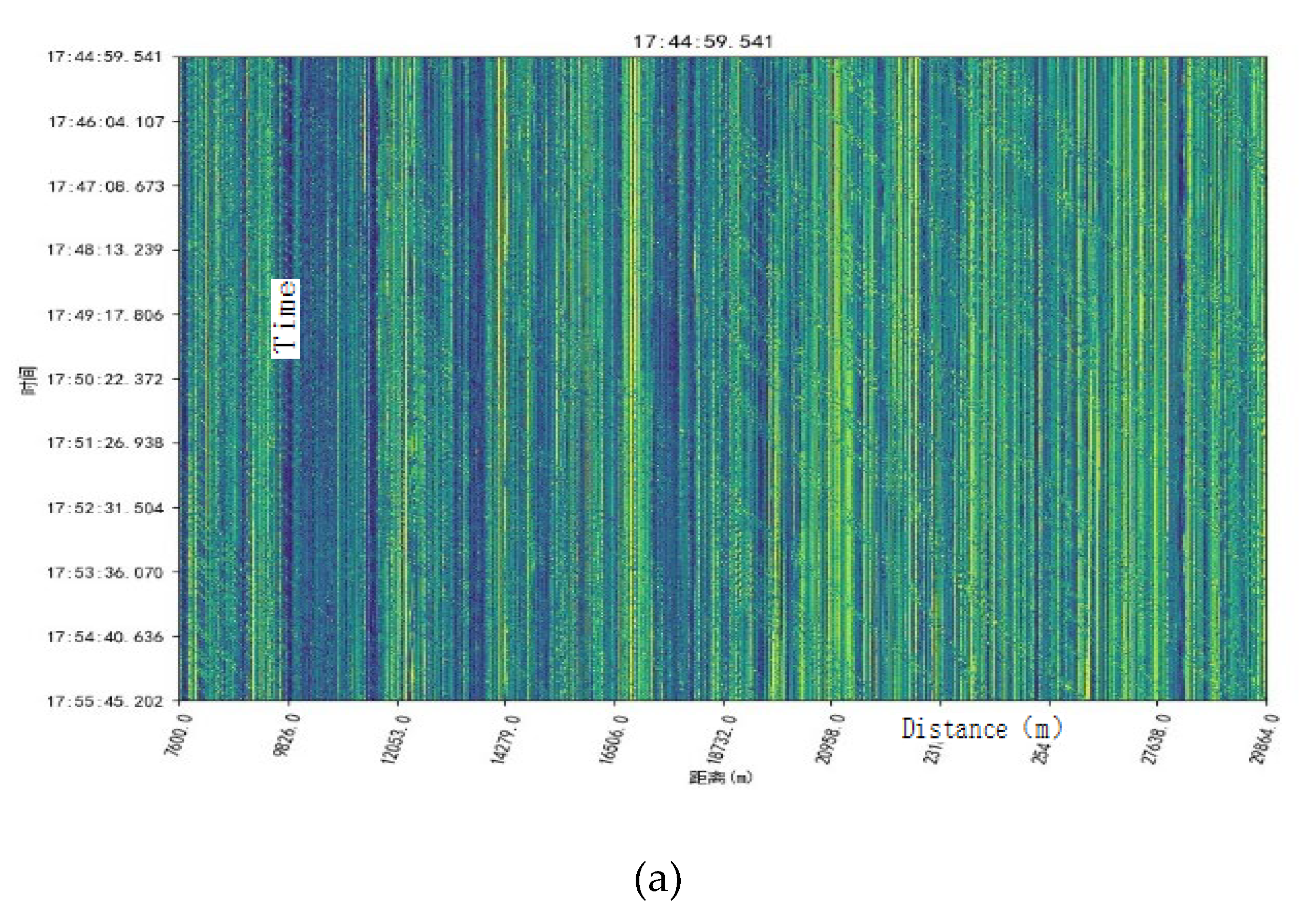

To address the above three types of problems, we comprehensively utilize frequency-domain attention, time-domain feature-spatial attention, time-frequency feature-spatial attention, and long-branch spatio-temporal prior information association attention to construct a corresponding combined multi-head attention mechanism DVS signal analysis framework. This achieves background suppression and target signal detection, segmentation, and extraction, as shown in

Figure 3.

Using a sliding window mechanism similar to Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT), the monitoring signal is segmented in the time dimension. With frame length and frame shift , and the number of spatial points and the number of spatial points , then is an matrix.

Firstly, it is necessary to determine the frequency domain distribution range of the monitoring signal that is influenced by the target signal features. Signals other than the target signal are treated as background signals. The difference between the frequency domain distribution of the monitoring signal affected by the target signal features and the frequency domain distribution of the background signals serves as the metric for frequency-domain attention. Perform 1D frequency-domain filtering/enhancement on at each spatial point. The result will be the input for subsequent processing.

Next, extract the multi-dimensional features of the target signal in both the time domain and time-frequency domain. Introduce multi-head time-domain feature-spatial attention and perform multi-channel fusion to obtain the time-domain feature-spatial attention fusion result . Introduce multi-head time-frequency domain feature-spatial attention and perform multi-channel fusion to obtain the time-frequency domain feature-spatial attention fusion result .

Finally, combine the predictive prior information from the previous frame. and each consider inter-frame spatio-temporal prior information branch attention. Their processed results are fused to obtain the final target signal analysis and detection result .Simultaneously, update the predictive prior attention information used for processing the next frame.