Submitted:

14 September 2025

Posted:

17 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Background

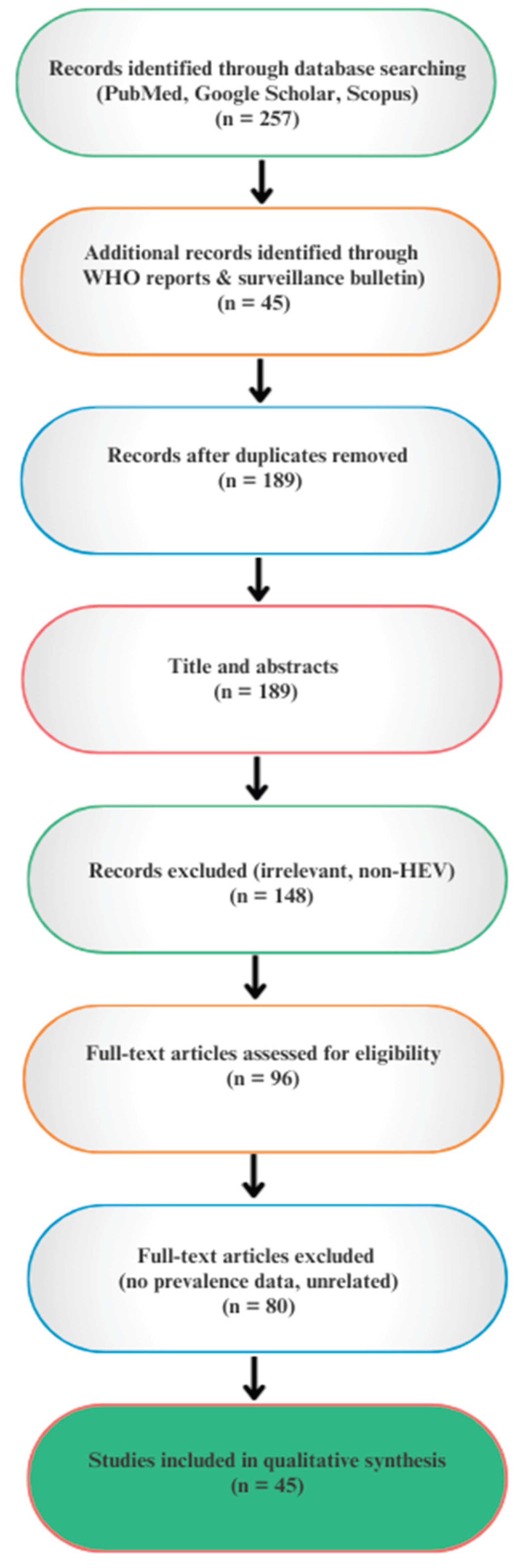

Methods

Inclusion Criteria

- Studies published in English between 1990 and 2025.

- Articles reporting human or animal HEV prevalence, outbreak investigations, or case series from Nigeria and Africa.

- Reviews, surveillance reports, and policy papers relevant to HEV epidemiology, prevention, or One Health strategies.

Exclusion Criteria

- Studies focusing on unrelated viral hepatitis (e.g., hepatitis A, B, C, D).

- Case reports or studies lacking primary epidemiological or diagnostic data.

- Duplicated reports already included in systematic reviews unless they contributed additional local context.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Results And Discussions

- Burden of HEV in Africa

- 2.

- HEV Epidemiology in Nigeria

- Okagbue et al. (2019): Reviewing 1,178 human and 210 pig samples across a 10-year dataset, reported 10.8% prevalence in humans and a striking 65.7% in pigs [17]. Although a weak, non-significant association was found between human and animal infections (r = 0.327, p = 0.474), regression analysis (p = 0.376) explained only 9.3% of variability. The odds ratio (OR = 1.03, 95% CI: 0.95–1.20) suggested slightly higher prevalence in animals, reinforcing pigs as a key reservoir. Food and animal handlers, as well as those lacking access to clean water, were identified as primary risk groups.

- Antia et al. (2018): Reported 57.5% prevalence in pigs, but no evidence of infection in goats and cattle [60].

- Olayinka et al. (2020): Detected 13.2% prevalence in pigs using fecal samples tested by ELISA [61].

- Oluremi et al. (2023): Reported 14.9% IgG and 1.3% IgM positivity in communities in southwestern Nigeria, indicating both past exposure and ongoing active transmission [58].

- Ekiti State study: Documented an overall 13.4% antibody prevalence, consistent with findings from Oluremi et al. [62].

Demographic, Occupational, and Regional Patterns of HEV in Nigeria

- 3.

- Comparative Insights: Nigeria vs Africa

- Nigeria’s human prevalence (10–15%) is moderate compared with Egypt (50–80%), but higher than Tanzania (0.2–6%).

- Nigeria’s pig prevalence (30–65%) is among the highest on the continent, comparable to Ghana and Madagascar.

- Occupational exposure patterns (butchers, pig handlers) [38] mirror those reported in Ghana and Cameroon, suggesting a shared West/Central African risk profile.

- Underestimated and Unquantified Burden

- 2.

- Inconsistencies in Diagnostic Practices

- 3.

- Limited Genetic Characterization of Circulating Strains

- 4.

- Insufficient knowledge of Predisposing Risk Factors

- 5.

- Pathophysiology in Immunocompromised Hosts

- 6.

- Unclear Genetic Risk Factors

- 7.

- Zoonotic Uncertainty

- 8.

- Environmental Contamination

- 9.

- Gaps in Public Awareness and Education

- Human-Animal-Environment Interface

- 2.

- Integration of Epidemiological Data

- 3.

- Animal Screening as a Key Component of the One Health Framework

- 4.

- Community and Veterinary Rural and Urban Extension Services

Limitations

Conclusions

Author Contribution

Data Availability Statement

Conflict of Interest

References

- WHO Health Fact Sheet, 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-e.

- Panda, S. K., Thakral, D., & Rehman, S. (2007). Hepatitis E virus. Reviews in medical virology, 17(3), 151–180. [CrossRef]

- Purcell, R. H., & Emerson, S. U. (2008). Hepatitis E: an emerging awareness of an old disease. Journal of hepatology, 48(3), 494–503. [CrossRef]

- Patra S, Kumar A, Trivedi SS, Puri M, Sarin SK. Maternal and fetal outcomes in pregnant women with acute hepatitis E virus infection. Ann Intern Med. 2007 Jul 3;147(1):28-33. PMID: 17606958. [CrossRef]

- Waqar S, Sharma B, Koirala J. Hepatitis E. [Updated 2023 Jun 26]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532278/.

- Wang, B., & Meng, X. J. (2021). Structural and molecular biology of hepatitis E virus. Computational and structural biotechnology journal, 19, 1907–1916. [CrossRef]

- Yamashita T, Mori Y, Miyazaki N, Cheng RH, Yoshimura M, Unno H, Shima R, Moriishi K, Tsukihara T, Li TC, Takeda N, Miyamura T, Matsuura Y. Biological and immunological characteristics of hepatitis E virus-like particles based on the crystal structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Aug 04;106(31):12986-91.

- Dong, C., Meng, J., Dai, X., Liang, J. H., Feagins, A. R., Meng, X. J., Belfiore, N. M., Bradford, C., Corn, J. L., Cray, C., Glass, G. E., Gordon, M. L., Hesse, R. A., Montgomery, D. L., Nicholson, W. L., Pilny, A. A., Ramamoorthy, S., Shaver, D. D., Drobeniuc, J., Purdy, M. A., … Teo, C. G. (2011). Restricted enzooticity of hepatitis E virus genotypes 1 to 4 in the United States. Journal of clinical microbiology, 49(12), 4164–4172. [CrossRef]

- Boadella, M., Casas, M., Martín, M., Vicente, J., Segalés, J., de la Fuente, J., & Gortázar, C. (2010). Increasing contact with hepatitis E virus in red deer, Spain. Emerging infectious diseases, 16(12), 1994–1996. [CrossRef]

- Saade MC, Haddad G, el Hayek M, Shaib Y. The burden of Hepatitis E virus in the Middle East and North Africa region: a systematic review. The Journal of Infection in Developing Countries [Internet]. 2022 May 30 [cited 2025 Sep 9];16(05):737–44. Available from: https://jidc.org/index.php/journal/article/view/15701.

- Boukhrissa H, Mechakra S, Mahnane A, Boussouf N, Gasmi A, Lacheheb A. Seroprevalence of hepatitis E virus among blood donors in eastern Algeria. Tropical Doctor [Internet]. 2022 Oct 1 [cited 2025 Sep 9];52(4):479–83. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35791644/.

- Ekanem E, Ikobah J, Okpara H, Udo J. Seroprevalence and predictors of hepatitis E infection in Nigerian children. The Journal of Infection in Developing Countries [Internet]. 2015 Nov 30 [cited 2025 Sep 9];9(11):1220–5. Available from: https://jidc.org/index.php/journal/article/view/6736.

- Tucker TJ, Kirsch RE, Louw SJ, Isaacs S, Kannemeyer J, Robson SC. Hepatitis E in South Africa: Evidence for sporadic spread and increased seroprevalence in rural areas. Journal of Medical Virology [Internet]. 1996 Oct [cited 2025 Sep 9];50(2):117–9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8915876/.

- Kim JH, Nelson KE, Panzner U, Kasture Y, Labrique AB, Wierzba TF. A systematic review of the epidemiology of hepatitis E virus in Africa. BMC Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2014 Jun 5 [cited 2025 Sep 9];14(1):1–13. Available from: https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2334-14-308.

- Bagulo, H., Majekodunmi, A. O., & Welburn, S. C. (2020). Hepatitis E in Sub Saharan Africa - A significant emerging disease. One health (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 11, 100186. [CrossRef]

- Elduma AH, Zein MMA, Karlsson M, Elkhidir IME, Norder H. A Single Lineage of Hepatitis E Virus Causes Both OutbrA, Opanuga AA. Hepatitis E infection in Nigeria: a systematic review. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2019;7(10):1719–1722. [CrossRef]

- Okagbue HI, Adamu MO, Bishop SA, Oguntunde PE, Odetunmibi OA, Opanuga AA. Hepatitis E infection in Nigeria: a systematic review. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2019;7(10):1719–1722. [CrossRef]

- Aubry, P., et al. (1997) Seroprevalence of Hepatitis E Virus in an Adult Urban Popund Hygiene, 57, 272-273. [CrossRef]

- Feldt T, Sarfo FS, Zoufaly A, Phillips RO, Burchard G, van Lunzen J, Jochum J, Chadwick D, Awasom C, Claussen L, Drosten C, Drexler JF, Eis-Hubinger AM. Hepatitis E virus infections in HIV-infected patients in Ghana and Cameroon. J Clin Virol. 2013;14:18–23. [CrossRef]

- Pawlotsky JM, Belec L, Gresenguet G, Deforges L, Bouvier M, Duval J, Dhumeaux D. High prevalence of hepatitis B, C, and E markers in young sexually active adults from the Central African Republic. J Med Virol. 1995;14:269–272. [CrossRef]

- Gambel, J. M., Drabick, J. J., Seriwatana, J., & Innis, B. L. (1998). Seroprevalence of hepatitis E virus among United Nations Mission in Haiti (UNMIH) peacekeepers, 1995. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene, 58(6), 731-736.

- Abe K, Li TC, Ding X, Win KM, Shrestha PK, Quang VX, Ngoc TT, Taltavull TC, Smirnov AV, Uchaikin VF, Luengrojanakul P, Gu H, El-Zayadi AR, Prince AM, Kikuchi K, Masaki N, Inui A. International collaborative survey on epidemiology of hepatitis E virus in 11 countries. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2006;14:90–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar].

- Fix AD, Abdel-Hamid M, Purcell RH, Shehata MH, Abdel-Aziz F, Mikhail N, el Sebai H, Nafeh M, Habib M, Arthur RR, Emerson SU, Strickland GT. Prevalence of antibodies to hepatitis E in two rural Egyptian communities. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;14:519–523.

- Gad YZ, Mousa N, Shams M, Elewa A. Seroprevalence of subclinical HEV infection in asymptomatic, apparently healthy, pregnant women in Dakahlya Governorate, Egypt. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2011;14:136–139.

- Darwish MA, Faris R, Clemens JD, Rao MR, Edelman R. High seroprevalence of hepatitis A, B, C, and E viruses in residents in an Egyptian village in The Nile Delta: a pilot study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;14:554–558.

- Abdel Hady SI, El-Din MS, El-Din ME. A high hepatitis E virus (HEV) seroprevalence among unpaid blood donors and haemodialysis patients in Egypt. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 1998;14:165–179.

- Amer AF, Zaki SA, Nagati AM, Darwish MA. Hepatitis E antibodies in Egyptian adolescent females: their prevalence and possible relevance. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 1996;14:273–284.

- El-Esnawy NA. Examination for hepatitis E virus in wastewater treatment plants and workers by nested RT-PCR and ELISA. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2000;14:219–231.

- Stoszek SK, Abdel-Hamid M, Saleh DA, El Kafrawy S, Narooz S, Hawash Y, Shebl FM, El Daly M, Said A, Kassem E, Mikhail N, Engle RE, Sayed M, Sharaf S, Fix AD, Emerson SU, Purcell RH, Strickland GT. High prevalence of hepatitis E antibodies in pregnant Egyptian women. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2006;14:95–101. [CrossRef]

- Caron M, Kazanji M. Hepatitis E virus is highly prevalent among pregnant women in Gabon, central Africa, with different patterns between rural and urban areas. Virol J. 2008;14:158. [CrossRef]

- Richard-Lenoble D, Traore O, Kombila M, Roingeard P, Dubois F, Goudeau A. Hepatitis B, C, D, and E markers in rural equatorial African villages (Gabon) Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;14:338–341.

- Feldt T, Sarfo FS, Zoufaly A, Phillips RO, Burchard G, van Lunzen J, Jochum J, Chadwick D, Awasom C, Claussen L, Drosten C, Drexler JF, Eis-Hubinger AM. Hepatitis E virus infections in HIV-infected patients in Ghana and Cameroon. J Clin Virol. 2013;14:18–23. [CrossRef]

- Adjei AA, Aviyase JT, Tettey Y, Adu-Gyamfi C, Mingle JA, Ayeh-Kumi PF, Adiku TK, Gyasi RK. Hepatitis E virus infection among pig handlers in Accra, Ghana. East Afr Med J. 2009 Aug;86(8):359-63. [CrossRef]

- Martinson FE, Marfo VY, Degraaf J. Hepatitis E virus seroprevalence in children living in rural Ghana. West Afr J Med. 1999;14:76–79.

- Bagulo, H., Majekodunmi, A.O., Welburn, S.C. et al. Hepatitis E seroprevalence and risk factors in humans and pig in Ghana. BMC Infect Dis 22, 132 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Obaidat, Mohammad M., and Amira A. Roess. “Individual Animal and Herd Level Seroprevalence and Risk Factors of Hepatitis E in Ruminants in Jordan.” Infection Genetics and Evolution, vol. 81, July 2020, p. 104276. [CrossRef]

- Temmam, S., Besnard, L., Andriamandimby, S. F., Foray, C., Rasamoelina-Andriamanivo, H., Héraud, J. M., Cardinale, E., Dellagi, K., Pavio, N., Pascalis, H., & Porphyre, V. (2013). High prevalence of hepatitis E in humans and pigs and evidence of genotype-3 virus in swine, Madagascar. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene, 88(2), 329–338. [CrossRef]

- Aamoum, A., Baghad, N., Boutayeb, H., & Benchemsi, N. (2004). Séroprévalence de l’hépatite E a Casablanca [Seroprevalence of hepatitis E virus in Casablanca]. Medecine et maladies infectieuses, 34(10), 491–492.

- Bernal, M.C., Leyva, A., Garcia, F. et al. Seroepidemiological study of hepatitis E virus in different population groups. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 14, 954–958 (1995). [CrossRef]

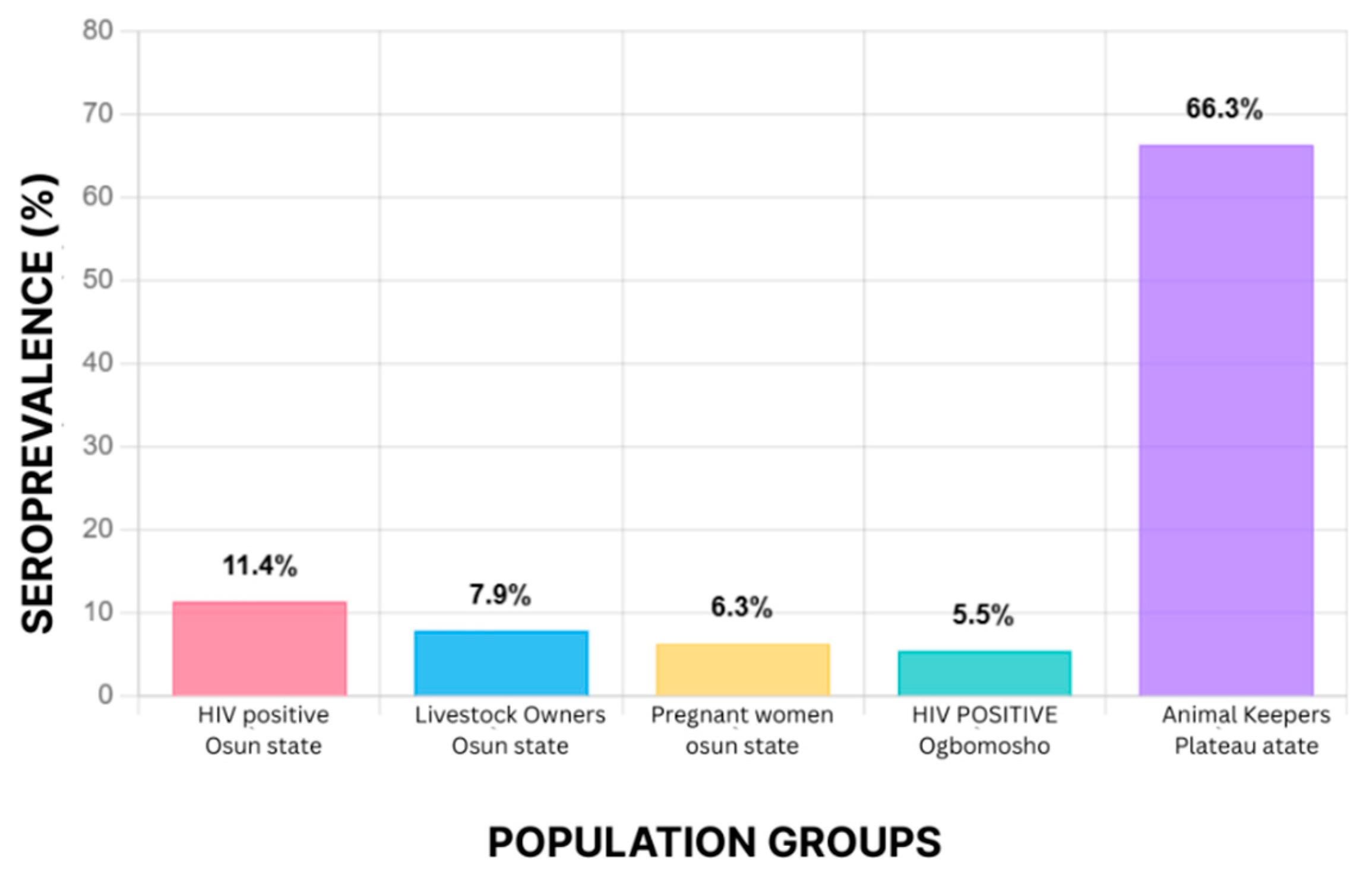

- Osundare FA, Klink P, Akanbi OA, Wang B, Harms D, Ojurongbe O, et al. Hepatitis E virus infection in high-risk populations in Osun State, Nigeria. One Health. 2021;13:100256. [CrossRef]

- Junaid S., Agina S. E., Jaiye K., “Seroprevalence of Hepatitis E Virus Among Domestic Animals in Plateau State–Nigeria.” British Microbiology Research Journal, vol. 4, no. 8, Jan. 2014, pp. 924–34. [CrossRef]

- Tucker TJ, Kirsch RE, Louw SJ, Isaacs S, Kannemeyer J, Robson SC. Hepatitis E in South Africa: evidence for sporadic spread and increased seroprevalence in rural areas. J Med Virol. 1996;14:117–119.

- Grabow WO, Favorov MO, Khudyakova NS, Taylor MB, Fields HA. Hepatitis E seroprevalence in selected individuals in South Africa. J Med Virol. 1994;14:384–388. [CrossRef]

- Stark K, Poggensee G, Hohne M, Bienzle U, Kiwelu I, Schreier E. Seroepidemiology of TT virus, GBC-C/HGV, and hepatitis viruses B, C, and E among women in a rural area of Tanzania. J Med Virol. 2000;14:524–530.

- Ben Halima M, Arrouji Z, Slim A, Lakhoua R, Ben Redjeb S. [Epidemiology of hepatitis E in Tunisia] Tunis Med. 1998;14:129–131.

- Hannachi N, Boughammoura L, Marzouk M, Tfifha M, Khlif A, Soussi S, Skouri H, Boukadida J. [Viral infection risk in polytransfused adults: seroprevalence of seven viruses in central Tunisia] Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 2011;14:220–225. [CrossRef]

- Hannachi N, Hidar S, Harrabi I, Mhalla S, Marzouk M, Ghzel H, Ghannem H, Khairi H, Boukadida J. [Seroprevalence and risk factors of hepatitis E among pregnant women in central Tunisia] Pathol Biol (Paris) 2011;14:e115–e118. [CrossRef]

- Rezig D, Ouneissa R, Mhiri L, Mejri S, Haddad-Boubaker S, Ben Alaya N, Triki H. [Seroprevalences of hepatitis A and E infections in Tunisia] Pathol Biol (Paris) 2008;14:148–153. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs C, Chiluba C, Phiri C, Lisulo MM, Chomba M, Hill PC, Ijaz S, Kelly P. Seroepidemiology of Hepatitis E Virus Infection in an Urban Population in Zambia: Strong Association With HIV and Environmental Enteropathy. J Infect Dis. 2014;14:652–657. [CrossRef]

- Miller WC, Shao JF, Weaver DJ, Shimokura GH, Paul DA, Lallinger GJ. Seroprevalence of viral hepatitis in Tanzanian adults. Trop Med Int Health. 1998;14:757–763. [CrossRef]

- Pawlotsky JM, Belec L, Gresenguet G, Deforges L, Bouvier M, Duval J, Dhumeaux D. High prevalence of hepatitis B, C, and E markers in young sexually active adults from the Central African Republic. J Med Virol. 1995;14:269–272. [CrossRef]

- Borno State Government, Nigeria Health Sector. Northeast Nigeria Response Health Sector Bulletin #36 (November 2017). Available from: http://origin.who.int/health-cluster/countries/nigeria/Borno-Health-Sector-Bulletin-Issue36.pdf. Published 2017.

- Meldal BH, Sarkodie F, Owusu-Ofori S, Allain JP. Hepatitis E virus infection in Ghanaian blood donors – the importance of immunoassay selection and confirmation. Vox Sanguinis. 2012;14:30–36.

- Olayinka, A., Ifeorah, I. M., Omotosho, O., Faleye, T. O. C., Odukaye, O., Bolaji, O., Ibitoye, I., Ope-Ewe, O., Adewumi, M. O., & Adeniji, J. A. (2020). A possible risk of environmental exposure to HEV in Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria. Journal of Immunoassay & Immunochemistry, 41(5), 875–884. [CrossRef]

- Traoré, Kuan Abdoulaye, et al. “Seroprevalence of Fecal-Oral Transmitted Hepatitis a and E Virus Antibodies in Burkina Faso.” PloS ONE, vol. 7, no. 10, Oct. 2012, p. E48125. [CrossRef]

- Capai L, Masse S, Gallian P, Souty C, Isnard C, Blanchon T, et al. Seroprevalence Study of Anti-HEV IgG among Different Adult Populations in Corsica, France, 2019. Microorganisms. 2019;7(10):460. [CrossRef]

- Modiyinji AF, Amougou Atsama M, Monamele Chavely G, Nola M, Njouom R. Detection of hepatitis E virus antibodies among Cercopithecidae and Hominidae monkeys in Cameroon. J Med Primatol. 2019;48(6):364–6.

- Oluremi AS, Casares-Jimenez M, Opaleye OO, Caballero-Gomez J, Ogbolu DO, Lopez-Lopez P, et al. Butchering activity is the main risk factor for hepatitis E virus (Paslahepevirus balayani) infection in southwestern Nigeria: a prospective cohort study. Front Microbiol. 2023;14. [CrossRef]

- Buisson Y, Grandadam M, Coursaget P, Cheval P, Rehel P, Nicand E, et al. Identification of a novel hepatitis E virus in Nigeria. J Gen Virol. 2000;81(4):903–909. [CrossRef]

- Antia RE, Adekola AA, Jubril AJ, Ohore OG, Emikpe BO. Hepatitis E virus infection seroprevalence and the associated risk factors in animals raised in Ibadan, Nigeria. J Immunoassay Immunochem. 2018;39(5):509–520. [CrossRef]

- Olayinka, A., Ifeorah, I. M., Omotosho, O., Faleye, T. O. C., Odukaye, O., Bolaji, O., Ibitoye, I., Ope-Ewe, O., Adewumi, M. O., & Adeniji, J. A. (2020). A possible risk of environmental exposure to HEV in Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria. Journal of Immunoassay & Immunochemistry, 41(5), 875–884. [CrossRef]

- Adesina O.A., Japhet M.O., Donbraye E., Kumapayi T.E., Kudoro A. Anti hepatitis E virus antibodies in sick and healthy Individuals in Ekiti State, Nigeria. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2009;3:533–536.

- Osundare FA, Klink P, Majer C, Akanbi OA, Wang B, Faber M, et al. Hepatitis E Virus Seroprevalence and Associated Risk Factors in Apparently Healthy Individuals from Osun State, Nigeria. Pathogens. 2020;9(5):392. [CrossRef]

- Abioye JOK, Anarado KS, Babatunde S. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection among students of Bingham University, Karu in North-Central Nigeria. Int J Pathog Res. 2021;7(4):38–47. [CrossRef]

- Ashipala DO, Tomas N, Joel MH. Hepatitis E. In: Advances in human services and public health (AHSPH) book series. 2021. p. 144–156. [CrossRef]

- Webb, G. W., & Dalton, H. R. (2019). Hepatitis E: an underestimated emerging threat. Therapeutic advances in infectious disease, 6, 2049936119837162. [CrossRef]

- Raji, Y. E., Toung, O. P., Taib, N. M., & Sekawi, Z. B. (2022). Hepatitis E Virus: An emerging enigmatic and underestimated pathogen. Saudi journal of biological sciences, 29(1), 499–512. [CrossRef]

- Maehira, Y., & Spencer, R. C. (2019). Harmonization of Biosafety and Biosecurity Standards for High-Containment Facilities in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: An Approach From the Perspective of Occupational Safety and Health. Frontiers in public health, 7, 249. [CrossRef]

- Balaban, H. Y., Aslan, A. T., Akdoğan-Kittana, F. N., Alp, A., Dağ, O., Ayar, Ş. N., Vahabov, C., Şimşek, C., Yıldırım, T., Göker, H., Ergünay, K., Erdem, Y., Büyükaşık, Y., & Şimşek, H. (2022). Hepatitis E Virus Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors in High-Risk Groups: A Cross-Sectional Study. The Turkish journal of gastroenterology : the official journal of Turkish Society of Gastroenterology, 33(7), 615–624. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Gracia, M. T., García, M., Suay, B., & Mateos-Lindemann, M. L. (2015). Current Knowledge on Hepatitis E. Journal of clinical and translational hepatology, 3(2), 117–126. [CrossRef]

- Takakusagi, S., Kakizaki, S., & Takagi, H. (2023). The Diagnosis, Pathophysiology, and Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis E Virus Infection-A Condition Affecting Immunocompromised Patients. Microorganisms, 11(5), 1303. [CrossRef]

- Realpe-Quintero, M., Montalvo, M. C., Mirazo, S., Panduro, A., Roman, S., Johne, R., & Fierro, N. A. (2018). Challenges in research and management of hepatitis E virus infection in Cuba, Mexico, and Uruguay. Revista panamericana de salud publica = Pan American journal of public health, 42, e41. [CrossRef]

- Bi, H., Yang, R., Wu, C., & Xia, J. (2020). Hepatitis E virus and blood transfusion safety. Epidemiology and infection, 148, e158. [CrossRef]

- Yugo, D. M., Cossaboom, C. M., & Meng, X. J. (2014). Naturally occurring animal models of human hepatitis E virus infection. ILAR journal, 55(1), 187–199. [CrossRef]

- Nemes, K., Persson, S., & Simonsson, M. (2023). Hepatitis A Virus and Hepatitis E Virus as Food- and Waterborne Pathogens-Transmission Routes and Methods for Detection in Food. Viruses, 15(8), 1725. [CrossRef]

- Mbachu, C. N. P., Ebenebe, J. C., Okpara, H. C., Chukwuka, J. O., Mbachu, I. I., Elo-Ilo, J. C., Ndukwu, C. I., & Egbuonu, I. (2021). Hepatitis e prevalence, knowledge, and practice of preventive measures among secondary school adolescents in rural Nigeria: a cross-sectional study. BMC public health, 21(1), 1655. [CrossRef]

- Horefti E. (2023). The Importance of the One Health Concept in Combating Zoonoses. Pathogens (Basel, Switzerland), 12(8), 977. [CrossRef]

- Eussen, B.G., Schaveling, J., Dragt, M.J. et al. Stimulating collaboration between human and veterinary health care professionals. BMC Vet Res 13, 174 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Velavan, T. P., Pallerla, S. R., Johne, R., Todt, D., Steinmann, E., Schemmerer, M., Wenzel, J. J., Hofmann, J., Shih, J. W. K., Wedemeyer, H., & Bock, C. T. (2021). Hepatitis E: An update on One Health and clinical medicine. Liver international : official journal of the International Association for the Study of the Liver, 41(7), 1462–1473. [CrossRef]

- Ezeonwumelu, I. J., Garcia-Vidal, E., & Ballana, E. (2021). JAK-STAT Pathway: A Novel Target to Tackle Viral Infections. Viruses, 13(12), 2379. [CrossRef]

- Rajendiran, S., Li Ping, W., Veloo, Y., & Syed Abu Thahir, S. (2024). Awareness, knowledge, disease prevention practices, and immunization attitude of hepatitis E virus among food handlers in Klang Valley, Malaysia. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics, 20(1), 2318133. [CrossRef]

- George, J., Shafqat, N., Verma, R., & Patidar, A. B. (2023). Factors Influencing Compliance With Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) Use Among Healthcare Workers. Cureus, 15(2), e35269. [CrossRef]

- Lu, L., & Wu, J. (2020). "Hepatitis E Virus Transmission and Its Interactions with the Host." In Microorganisms, 8(6), 960. [CrossRef]

- Paltiel, A. D., Zheng, A., & Zheng, A. (2022). “Investing in Community Health: The Impact of Continuous Funding on Disease Management.” American Journal of Public Health, 112(3), 431-439. [CrossRef]

- Raimondo, M., et al., (2021). "Molecular Detection of Hepatitis E Virus in Pigs: A Review of Current Techniques." Veterinary Microbiology, 252, 108965.

- Kenney S. P. (2019). The Current Host Range of Hepatitis E Viruses. Viruses, 11(5), 452. [CrossRef]

- Talapko, J., Meštrović, T., Pustijanac, E., & Škrlec, I. (2021). Towards the Improved Accuracy of Hepatitis E Diagnosis in Vulnerable and Target Groups: A Global Perspective on the Current State of Knowledge and the Implications for Practice. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland), 9(2), 133. [CrossRef]

- Dubbert, T., Meester, M., Smith, R. P., Tobias, T. J., Di Bartolo, I., Johne, R., Pavoni, E., Krumova-Valcheva, G., Sassu, E. L., Prigge, C., Aprea, G., May, H., Althof, N., Ianiro, G., Żmudzki, J., Dimitrova, A., Alborali, G. L., D’Angelantonio, D., Scattolini, S., Battistelli, N., … Burow, E. (2024). Biosecurity measures to control hepatitis E virus on European pig farms. Frontiers in veterinary science, 11, 1328284. [CrossRef]

- Augustyniak A, Pomorska-Mól M. An Update in Knowledge of Pigs as the Source of Zoonotic Pathogens. Animals. 2023; 13(20):3281. [CrossRef]

- Mohr BJ, Souilem O, Fahmy SR, et al. Guidelines for the establishment and functioning of Animal Ethics Commitees (Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees) in Africa. Laboratory Animals. 2024;58(1):82-92. [CrossRef]

- Pawlak K, Kołodziejczak M. The Role of Agriculture in Ensuring Food Security in Developing Countries: Considerations in the Context of the Problem of Sustainable Food Production. Sustainability. 2020; 12(13):5488. [CrossRef]

- Danso-Abbeam, G., Ehiakpor, D.S. & Aidoo, R. Agricultural extension and its effects on farm productivity and income: insight from Northern Ghana. Agric & Food Secur 7, 74 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Njoga, E. O., Ilo, S. U., Nwobi, O. C., Onwumere-Idolor, O. S., Ajibo, F. E., Okoli, C. E., Jaja, I. F., & Oguttu, J. W. (2023). Pre-slaughter, slaughter and post-slaughter practices of slaughterhouse workers in Southeast, Nigeria: Animal welfare, meat quality, food safety and public health implications. PloS one, 18(3), e0282418. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, XX., Jin, YZ., Lu, YH. et al. Infectious disease control: from health security strengthening to health systems improvement at global level. glob health res policy 8, 38 (2023). [CrossRef]

| Country | Population Studied | Year | Diagnostic Method | Prevalence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South Africa | Canoeists high-risk, medical students low-risk. | 1994 | ELISA, Western blot | 2.6%, 1.80% | [43] |

| Djibouti | Male peacekeepers in Haiti | 1995 | ELISA | 13.00% | [21] |

| Gabon | Young villagers | 1995 | ELISA | 0.00% | [31] |

| Morocco | Adults | 1995 | ELISA & Western blot | 2.20% | [39] |

| Egypt | Residents of a semiurban village in the Nile River Delta | 1996 | ELISA | 57% | [25] |

| Egypt | Healthy Females (16 - 25 years) | 1996 | ELISA | 38.90% | [27] |

| South Africa | Blacks in rural and urban area | 1996 | ELISA | 15.3%, 6.6% | [42] |

| Burundi | Adults with chronic liver disease | 1997 | ELISA | 14% | [18] |

| Central African Republic | STD clinic patients | 1997 | EIA | 24.2% | [51] |

| Egypt | Blood donors, Haemodialysis patients | 2000 | EIA | 45.2%, 39.6% | [24] |

| Tanzania | Healthy students | 1998 | ELISA | 0.20% | [49] |

| Tunisia | Elderly, children with blood disorders, donors | 1998 | - | 46%, 29.5%, 22% | [44] |

| Ghana | Teenagers | 1999 | ELISA | 4.40% | [33] |

| Egypt | Rural residents of selected countries (16-30 years) | 2000 | ELISA | >20% | [24] |

| Egypt | Rural residents of two communities 1st decade, 2nd to 8th decade | 2000 | ELISA | 60%, 76%- >60% | [27] |

| Egypt | Sewage treatment plant workers | 2000 | Serology, Nested RT-PCR | 20–40 years: 50.9% – 50.4% 41–50 years: 43.2% 51–60 years: 46.2% |

[30] |

| Tanzania | Women between 15 and 45 years | 2000 | ELISA | 6.60% | [44] |

| Morocco | Blood donors | 2004 | ELISA | 8.50% | [38] |

| Egypt | Pregnant women | 2006 | EIA | 84.3% | [29] |

| Nigeria | Internally displaced persons | 2007 | ELISA | 64% | [52] |

| Gabon | Pregnant women | 2008 | ELISA | 14.2% | [30] |

| Tunisia | Healthy persons between 16 and 25 years | 2008 | - | 4.30% | [48] |

| Ghana | Pig handlers, Pregnant women | 2009 | ELISA | 38.1%, 28.7% | [33] |

| Ghana | Blood donors | 2009 | ELISA, Western blot and Transcriptase PCR | 4.06% | [53] |

| Nigeria | Sick and healthy individuals IgG, IgM | 2009 | 14.9%, 1.3% | [54] | |

| Egypt | Asymptomatic pregnant women (HCV)+ve and -ve | 2011 | ELISA | 71.42%, 46.7% | [22] |

| Tunisia | Polytransfused patients | 2011 | - | 28.9% | [46] |

| Tunisia | Pregnant women | 2011 | - | 12.10% | [47] |

| Burkina Faso | Blood donors | 2012 | ELISA and Immunochromatography | 19.1% | [55] |

| Burkina Faso | Pregnant women | 2012 | ELISA | 11.6% | [55] |

| Cameroon | HIV-infected adults | 2013 | RT-PCR | 14.2% | [19] |

| Ghana | HIV patients | 2013 | RT-qPCR | 45.3% | [19] |

| Madagascar | Slaughterhouse workers | 2013 | ELISA | 14.10% | [37] |

| Nigeria | Butchers, farmers (Plateau State) | 2014 | ELISA | High prevalence | [41] |

| Zambia | Urban adults, children | 2014 | ELISA | 42.0%, 16.0% | [49] |

| Cameroon | HIV-infected children | 2019 | RT-PCR | 2.0% | [19] |

| Nigeria | Hospitalized, healthcare workers, children, community, food handlers. | 2019 | ELISA, PCR | 10.8% | [17] |

| Nigeria | HIV+, animal handlers, pregnant women | 2021 | ELISA, PCR | 11.4%, 7.9%, 6.3% | [40] |

| Nigeria | Animal handlers, villagers, and students (IgG, IgM) | 2023 | ELISA | 14.9%, 1.3% | [54] |

| Country | Animal Species | Year | Diagnostic Method | Prevalence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Madagascar | Pigs | 2013 | ELISA, RT-PCR | 71.20% | [37] |

| Nigeria | Pigs, Goats, Sheep, Cattle | 2014 | ELISA | 32.8%, 37.2%, 10.5%, 0% | [41] |

| Nigeria | Pigs | 2018 | ELISA | 57.50% | [40] |

| Cameroon | Mandrill, Gorilla, Chimpanzee, Baboon | 2019 | ELISA | 11.1%, 14.3%, 5.9%, 8.7% | [58] |

| Nigeria | pigs | 2019 | RT-PCR | 65.70% | [17] |

| Jordan | Cows, Sheep, Goats | 2020 | ELISA | 14.5%, 12.7%, 8.3% | [36] |

| Nigeria | Pigs | 2020 | ELISA, RT-PCR | 13.20% | [56] |

| Ghana | Pigs | 2022 | ELISA | 62.40% | [35] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).