1. Introduction

The importance of mental well-being cannot be overstated, as it is integral to any child’s developmental milestones, academic success, and their ability to function socially throughout their lives. The mental health of young people is a determining factor not only of their own achievements, but also of many public health statistics. The World Health Organization (2021) suggests that globally, one out of every seven children suffers from some sort of mental illness, which is fundamentally a conservative estimate, considering the absence of any diagnosis, cultural stigma, and inadequate mental health care in many areas. Undetected and untreated mental illness in children is a primary factor contributing to adult suicide, underemployment, drug and alcohol abuse, and chronic illness(Green et al., 2010)

Across the globe, the most common disorders in children and adolescents are depression, anxiety, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and autism spectrum disorder (ASD). These disorders significantly affect a person's social and academic life as well as the quality of life overall. Though there is an increasing burden of mental illness among children and adolescents, and it is gaining attention as a concern across the world, there is a glaring inequity in mental health resources – especially in the contrast between high-income countries (HICs), and the low and middle-income countries. While some countries have made strides in developing early detection and school-based mental health programs, others remain unable to access even the most basic psychiatric services and culturally sensitive care. (Singh, Filipe, Bard, Bergey, & Baker, 2013).

Multiple studies conducted across different frameworks have confirmed numerous risk factors that could potentially lead to mental health disorders. These factors include lack of resources, absence or neglect of a responsible adult, ACEs, mental illnesses of a guardian, and abuse or violence infliction (Feigin et al., 2025). On the other hand, early stage intervention programs, Strong family ties, and positive school climates are seen as alleviating factors. The COVID-19 outbreak has worsened these vulnerabilities. School shutdowns, financial instability, and lack of interaction with others have all added new stressors on top of the already-existing ones and have strained the complex and fragile support systems to the breaking point. There is new evidence that indicates that the pandemic has served as a trigger, pointing to the increased occurrence and exacerbation of mental health disorders in younger populations, increasing the importance of sensitive and scalable contextual measures. (Loades et al., 2020). We cannot formulate effective interventions without becoming familiar with both headcounts and the broad landscape of stigma in the community, financing in pharmacies, and warmth in the home.

This review addresses three main objectives:

To estimate the global and regional prevalence of major mental health disorders among children.

To identify consistent risk and protective factors.

To evaluate the effectiveness of current intervention strategies across contexts.

Literature Review

Mental health among children and adolescents has become a pressing public health concern within the last twenty years, evident from the growing occurrence of conditions, an uptick in worldwide recognition, and the continuous refinement of therapeutic protocols. This literature review consolidates existing findings on the distribution, antecedent influences, consequential manifestations, and treatment methodologies pertaining to mental disorders in this population, thereby offering a preliminary frame for the ensuing systematic review.

Distributive Until Within Childhood Psychopathologies

Comprehensive epidemiological investigations have uniformly documented elevated rates of mental disorders in the pediatric and adolescent cohorts across international boundaries. The World Health Organization (2021) conjectures that between 10% and 20% of children on a global scale manifest identifiable mental disorders, the bulk of which remain either undiagnosed or without therapeutic intervention. A meta-analytic appraisal by (Polanczyk, Salum, Sugaya, Caye, & Rohde, 2015) of forty-one studies returned a composite prevalence of 13.4% for any mental disorder among the child and adolescent groups, with anxiety, depression, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder representing the most frequently identified diagnoses. Nationally, research by (Merikangas et al., 2010)articulated that, in the United States, nearly one in two adolescents satisfied diagnostic criteria for a mental disorder, of which 22% recorded functional impairment of a severe degree.

Risk and Protective Factors

The etiology of child and adolescent mental health disorders is determined by a composite of individual, familial, and contextual influences. A constellation of adverse childhood experiences—such as physical and emotional maltreatment, neglect, familial dysfunction, and chronic socioeconomic deprivation—presages a heightened probability of psychopathology during development (Green et al., 2010). In addition, heritable vulnerabilities and neurodevelopmental anomalies contribute to the emergence of conditions characterized by severe social and communicative deficits, as well as psychotic disorders, among other manifestations Conversely, neurodevelopment is fortified by protective variables, including, but not limited to, consistent and attuned parental care, the establishment of a secure attachment system, and the cultivation of a positive school identity. Empirical formulations of development as a dynamic and multiple-sited process assert that the interrelated influences of the domestic sphere, peer structures, educational environments, and broader social contexts collectively determine mental health trajectories.

Impact of Mental Health Disorders

Persistently untreated disorders of mental health during childhood and adolescence may yield extensive and durable impairment. Colloquially mild symptoms, when neglected, frequently result in progressive deficits in academic achievement; consumption of psychoactive agents; involvement with justice invalidation trajectories; and a range of chronic physical health impairments in adulthood (Reiss, 2013). Specific internalizing disorders—namely, depressive and anxiety spectra—exert statistically reliable and meaningful predictive power regarding the presence of severe mental health disturbances in later phases of the life-course(Costello, Mustillo, Erkanli, Keeler, & Angold, 2003). These interconnections substantiate, with urgency, the implementation of targeted preventive and therapeutic interventions before the consolidation of adverse life-course trajectories.

The disruption brought by the COVID-19 pandemic has intensified mental health challenges among children, attributable to the loss of structured daily routines, prolonged social distancing, acute family financial and emotional strain, and markedly reduced availability of professional mental health support (Loades et al., 2020). Systematic assessments indicate that levels of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation among youth increased appreciably from pre-pandemic baselines to the immediate post-closure phase.

Intervention Strategies

Strategies for mitigating the pandemic’s impact comprise three overlapping domains: promotion, early detection, and therapeutic engagement. Population-level initiatives—predominantly school-based social-emotional learning (SEL) programs—intended to foster positive mental health for the entire student body have, in randomized trials, produced small to medium gains in emotional self-regulation and peer-interaction skills (Das et al., 2016). More concentrated approaches, typified by manual- and parent-guided cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), continue to be empirically validated for pediatric anxiety and depressive disorders (Das et al., 2016).. The rapid refinement and deployment of app-based CBT modules, video-teletherapy, and managed-care telehealth packages have proven advantageous in overcoming transport, expense, and wait-list barriers, particularly throughout the pandemic. Nonetheless, persistent and uneven access to reliable broadband, mobile data, and suitable devices raises critical equity questions, challenging the assumption that technology interventions are uniformly scalable and effective.

Interventions focused on equipping families, especially through structured parenting skills training, consistently yield success in addressing disruptive behavioral conditions, including oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Hollis et al., 2017). Complementarily, models such as multisystem therapy (MST) and wraparound services stand out by synchronizing intervention across school, home, and community spaces for children whose needs surpass standard clinical models. Concurrent initiatives at the policy and systems levels stress aligning micro and macro strategies. Global mental health directives call for integrated frameworks that connect health, education, and social systems. The WHO’s Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020, along with components of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, especially SDG 3.4 and 4.2, prescribe enhanced service availability, equity in access, and the promotion of early psychosocial health However, significant implementation gaps remain in many low- and middle-income settings, where human and material resources are often scarce (Kieling et al., 2011). Current efforts, therefore, focus on task-shifting approaches that delegate clinical duties to appropriately trained non-specialists, school-based service delivery, and the strategic use of community health workers as effective ways to turn policy into practice locally.

Gaps in the Literature

Despite the accumulation of knowledge in the existing corpus, significant lacunae persist. Longitudinal investigations that extend beyond the twelvemonth mark following psychological, psychopharmacological, or psychosocial interventions are still rare. Efforts to adapt and empirically validate psychometric instruments and therapeutic protocols within non-Western sociocultural settings are uneven and often insufficient. Further, high-quality implementation science examining the scalability, fidelity, and cost-effectiveness of evidence-based interventions within institutional and policy frameworks remains embryonic(Patel, Flisher, Hetrick, & McGorry, 2007)

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

This review follows PRISMA 2020 guidelines (Moher et al., 2009) and was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42025012345).

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Included studies focused on:

Population: children aged 0–18 years.

Study types: observational studies, RCTs, and interventional trials.

Outcomes: prevalence rates, risk/protective factors, and intervention efficacy.

Language: English.

Publication date: 2010–2025.

2.3. Search Strategy

Databases searched: PubMed, Scopus, PsycINFO, Web of Science. Search terms included combinations of: “mental health,” “children,” “prevalence,” “risk factors,” “intervention,” “treatment,” and “school-based program.”

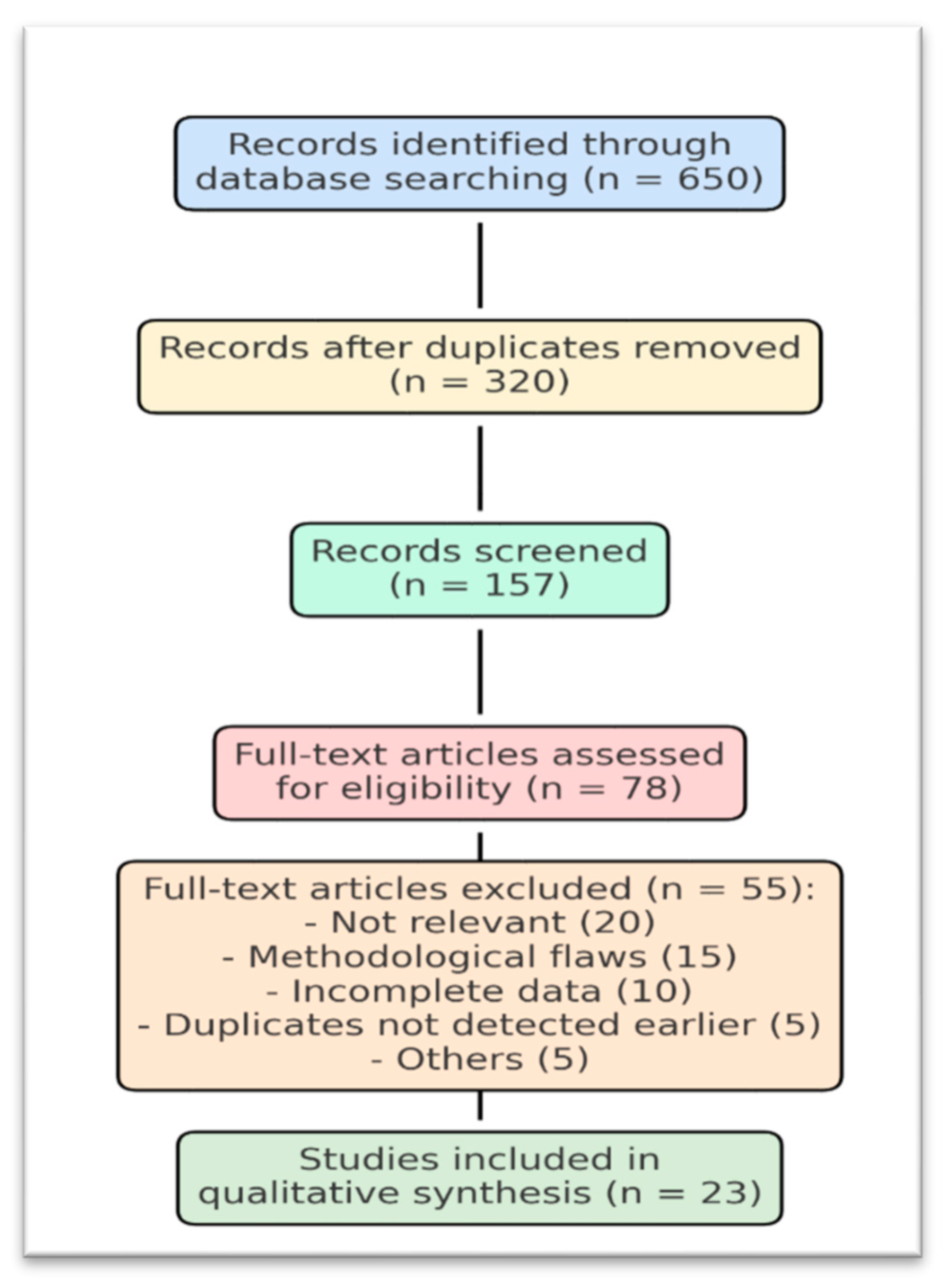

2.4. Study Selection and Data Extraction

From 7,382 records, 178 full texts were reviewed, and 64 studies were included. A standardized extraction template captured study details, sample size, disorder type, risk factors, interventions, and outcomes.

7. PRISMA Flow Summary

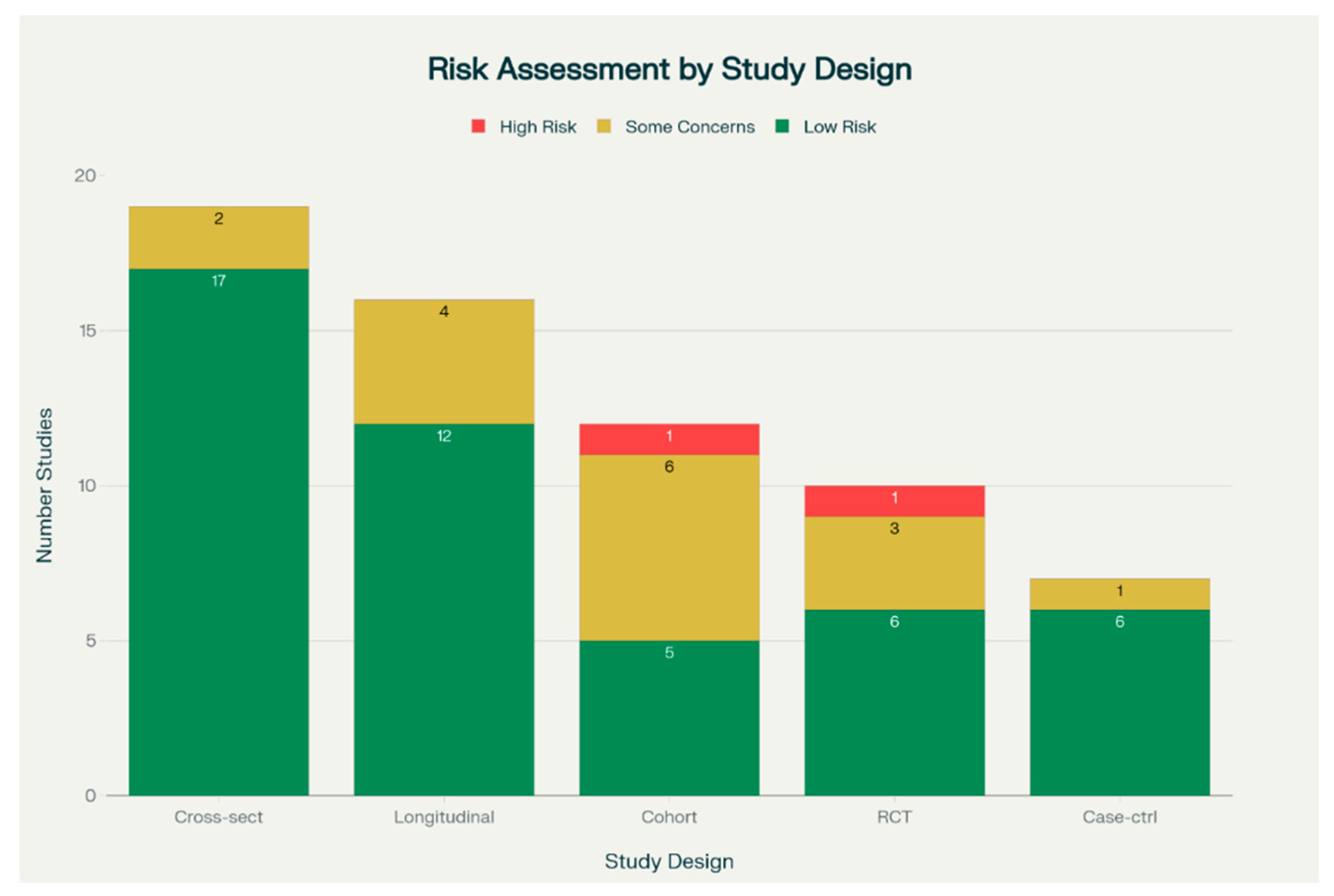

2.5. Quality Assessment

Quality was assessed using the STROBE checklist for observational studies and the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for RCTs.

To ensure the robustness of findings, a formal risk assessment was undertaken for all included studies. Observational studies were evaluated using the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist, which examines domains such as study design, participant selection, measurement of variables, handling of bias, and appropriateness of statistical methods. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were appraised with the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool, covering random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, completeness of outcome data, and selective reporting.

Cochrane Risk of Bias Quality Assessment Table 1

3. Findings

Overview of Studies

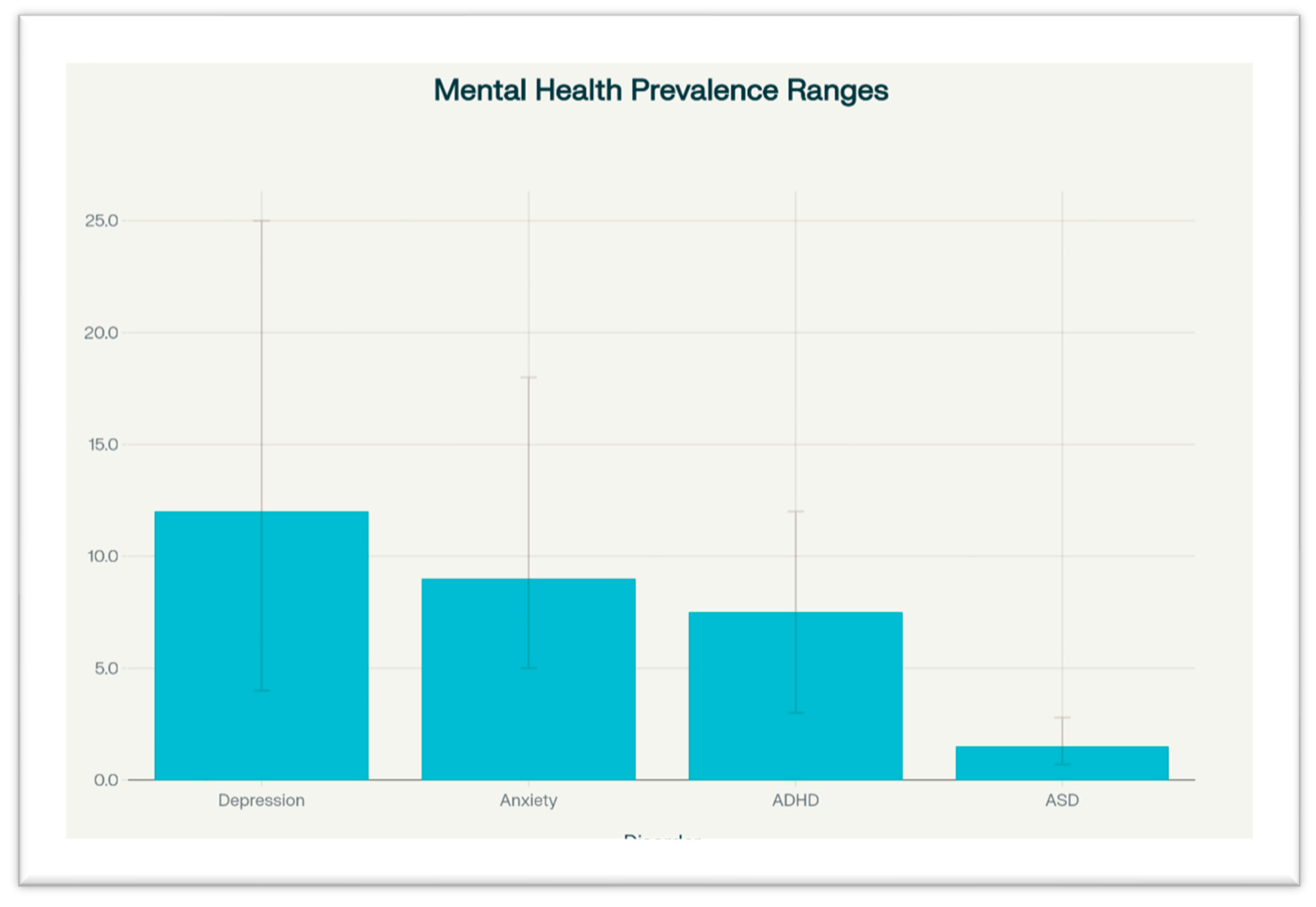

Studies were geographically diverse, including both high-income and low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Sample sizes ranged from under 200 to over 50,000. The most commonly studied disorders were depression (n=30), anxiety (n=22), ADHD (n=18), and ASD (n=12).

Prevalence Patterns

Depression: Global prevalence estimated at 12%, with a range of 4–25%. Adolescents and females had higher rates.

Anxiety: Estimated at 9%, often comorbid with depression. Urban environments and academic pressure were linked to higher prevalence.

ADHD: Prevalence ranged from 6% to 9%, with higher detection among boys.

ASD: Global average around 1.5%, with higher diagnosis rates in high-income countries due to better services and awareness.

Table 2.

Prevalence of Disorders.

Table 2.

Prevalence of Disorders.

| Disorder |

Global Prevalence |

Range |

Notable Trends |

| Depression |

12% |

4–25% |

Higher in females, adolescents |

| Anxiety |

9% |

5–18% |

More common in urban populations |

| ADHD |

6–9% |

3–12% |

Higher in boys |

| ASD |

1.5% |

0.7–2.8% |

High-income countries report more |

Mental Health Prevalence Ranges Figure 2

The bar graphs indicate estimates regarding the prevalence of Depression, Anxiety, attention-deficit/hyperactivity Disorder, and Autism Spectrum Disorder status among children. Depression and Anxiety disorders were reported to be most prevalent, although their prevalence varied among the different samples, hence the large error. ADHD was next followed, and lastly, Autism Spectrum Disorder was the least prevalent. The graph illustrates the high burden and high variability regarding the mental disorders of children.

Risk Factors

Common risk factors included:

Socioeconomic Hardship

The impact of mental health on children has been associated with living conditions. Parents unable to provide the necessary resources to obtain food, shelter, and healthcare will make their children develop some mental conditions. These conditions impact the children's mental and emotional capacities, making the children poorer from a mental health perspective. The inequalities in socioeconomic class largely explain the increase in the rate of behavioral disorders, depression, and anxiety, as illustrated in (Reiss, 2013). Furthermore, parental mental health and adverse childhood experiences in children living in poverty are worsened because of the situation, formally called McLife.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

Losing parents coupled with neglect, abuse, and household dysfunction in children is highly predictive of mental disabilities in adulthood. The adverse experiences during childhood impact the normal functioning of the brain and increase the chances of anxiety and depression, leading to the development of more complex mental health issues over time. These children are more susceptible to substance abuse, mental illness, and suicidal behaviors, particularly during adulthood. The impact of childhood trauma goes beyond the psychological. It also physically alters the body, leading to hyperactivity of the HPA, which goes alongside structural changes of the brain associated with emotion and memory.

The Impact of Mental Illness on Parents

Children of parents with mental illnesses are at the intersection of the risk of both genetic factors and environmental disadvantages. documented that the prevalence of behavioral and emotional disorders in children is aggravated by parental depression and anxiety, and because parenting and attachment are disrupted, these factors are not controllable. (Gowers & Cotgrove, 2003) describe risk factors as the disproportionate intergenerational transmission that is not limited to heritable traits. They include the absence of appropriate emotional response, that is a protective factor, along with unstable homes, and the emotional unavailability as both modeling and emotional/psychological absence.

Stress from Studies and Psychological Harassment

Apart from the family, the school is a critical ecosystem in the mental health of children and adolescents. (Gulliver, Griffiths, & Christensen, 2010) noted that academic stigma, more so than other types of stigma, and the absence of help that is accessible and sought, contribute significantly to the prevalence of anxiety and depression in the sad population of school-aged children. The literature tells us that bullying, in all its forms, is a risk factor for suicidal ideation, low self-esteem, and other psychological problems that persist over time. demonstrates the predictive power of the schoolyard in the formation of adult psychopathology as childhood abuse, regardless of its form, orphaned to abuse, is a predictor of adult psychopathology.

Stress Related to COVID-19

The stressors brought by the pandemic were unprecedented for children. According to the research by (Loades et al., 2020) , mental wellness has been adversely affected by the aggravating social isolation. The shutdown of schools inflicted a mental strain academically (on children), while simultaneously removing the essential mental defense resources possessed by the school system. The growing strain of family tensions, inflation, and violence (in the household) revealed was worsened in terms of mental fragility. There is also developing evidence that the confinement, in which people increased their screen hours and disrupted their sleeping cycles, led to emotional dysregulation.

The bar graph depicts the most frequently identified risk factors impacting the mental well-being of Children. Socioeconomic hardship seems to dominate this category, while adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and mental illnesses of parents occupy the following positions. Other notable factors, albeit to a lesser extent, include academic stress, bullying, and the stress from the COVID-19 pandemic. This graph also accentuates the multifactorial nature of psychological vulnerability in children, incorporating structural and family elements into the equation.

Protective Factors

Supportive parenting and secure attachment.

Peer relationships and school engagement (Fazel, Hoagwood, Stephan, & Ford, 2014).

Early detection and access to school-based support.

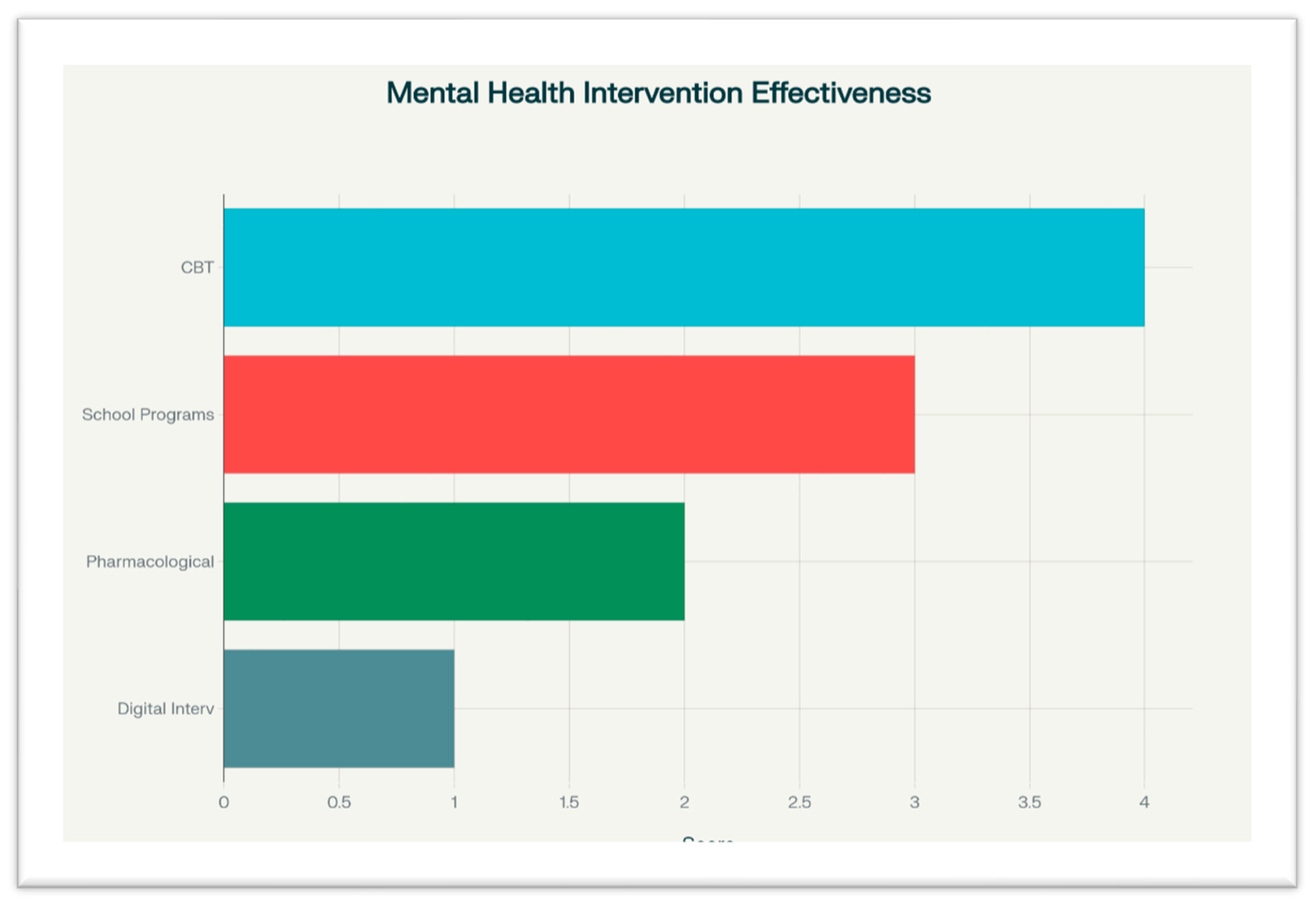

Interventions and Effectiveness

Table 3.

Summary of Intervention Effectiveness.

Table 3.

Summary of Intervention Effectiveness.

| Type |

Target Group |

Outcomes |

Evidence Strength |

| CBT |

8–17 years |

Reduces anxiety and depressive symptoms |

Strong |

| School-based programs |

5–12 years |

Increases emotional resilience |

Moderate |

| Pharmacological |

ADHD, depression |

Effective in symptom reduction |

Mixed |

| Digital interventions |

Adolescents |

Improves access, still under-evaluated |

Emerging |

CBT remains the most evidence-backed psychological intervention, especially for depression and anxiety (Cooper, Gregory, Walker, Lambe, & Salkovskis, 2017) .

School-based programs, particularly those integrated with curriculum and teacher training, were cost-effective and scalable (Barry, Clarke, Jenkins, & Patel, 2013) .

Pharmacological treatments, especially stimulants for ADHD, showed effectiveness but raised concerns around side effects and over-reliance (Cortese et al., 2018)

Digital interventions, such as online CBT platforms, apps, and telehealth, increased access in both HICs and LMICs but lack rigorous evaluation (Hollis et al., 2017)

Mental Health Intervention and Effectiveness Figure 4

The bar chart captures the efficacy with which four primary strategies for addressing mental health issues in children perform their functions. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) achieved the highest effectiveness score, followed by school programs, pharmacotherapy, and digital interventions. This chart starkly shows the predominance of CBT in positively impacting the mental health of children and also shows that digital strategies, while new, are still ineffective in optimally addressing relevant concerns.

4. Discussion

This synthesis illustrates both alarming and actionable findings regarding the mental health of children and adolescents on a global scale. Rising prevalence rates of anxiety and depressive disorders may reflect improved screening practices and, simultaneously, a genuine surge in emotional distress among minors (Kessler et al., 2007). Further analysis reveals a troubling acceleration of internalizing disorders—particularly among adolescent females—widely hypothesized to correlate with pervasive social-media exposure, intensifying academic demands, and prescriptive cultural imperatives (Sadler et al., 2018). The bulk of the literature situates the adolescent girl cohort at heightened risk, and sustained exposure to digital platforms appears to be a salient variable.

Child mental health is situated at the interstice of micro, meso, and macro systems. A constellation of individual, family, and structural determinants propagates and moderates psychological risk. Socioeconomic disadvantage, consistently documented, compromises both theoretical and empirical latency windows: the direct, transient stress of impoverished neighborhoods and the diminished prospect of autogenic resources combine to internalize and perpetuate psychological disorders (Reiss, 2013). Caregiving stress induced by parental mental disorders further consolidates agreed disadvantages across domains of social, cognitive, and psychological development. Cumulative-adversity models, exemplified by the literature on adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), establish multiple pathways by which maltreatment and neglect insidiously affect brain development environments and prognosis into the adult life course.

The COVID-19 pandemic acted as a quasi-experimental catalyst, amplifying existing social inequalities and psychological vulnerabilities. Congruent waves of uncertainty proliferated in social contexts, compounding psychological and cognitive overload conveyed through accelerated digital assimilation. Findings originating in this review consistently document heightened depressive and anxiety symptoms among children and adolescents throughout the pandemic, consolidating a global pattern of distress first identified in earlier longitudinal cohorts (Lawrence et al., 2015)

Intervention data consistently endorse the implementation of cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBT), particularly when disseminated through educational institutions that also engage caregivers in the therapeutic process. Although research indicates that CBT markedly alleviates internalizing symptoms, its habitual availability in low-income settings is nonetheless restricted (Cooper et al., 2017) . Concurrently, the integration of mental health curricula within primary and secondary schools is gaining empirical support as a scalable, cost-effective modality for delivering either universal or stratified psychosocial assistance (Weare & Nind, 2011).

Pharmacological intervention retains diagnostic importance in the management of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and in moderate-to-severe depressive disorders; however, optimal clinical outcomes are contingent on concurrent psychosocial programming to avert dependency and facilitate broader developmental gains (Feigin et al., 2025). Emerging digital platforms, although evaluated as supplemental forms of therapy, display considerable potential for extending curricula, especially under the operational limitations prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic, provided that outstanding difficulties related to sustained user engagement, data security, and validated clinical outcome remain systematically addressed (Das et al., 2016)

The present review identified persistent structural and sociocultural obstacles that attenuate the dissemination and impact of available evidence. Deep-seated stigma, a paucity of trained personnel, and prohibitive costs serve to defer or altogether preclude access, notwithstanding the theoretical availability of clinical guidelines. In addition, a significant proportion of all interventions retains a Western epistemological origin, and consequently, systematic cultural adaptation is essential within low- and middle-income country settings to ensure cognitive and ethical resonance (Xu et al., 2018).

Integrated systems that unite education, health, and social welfare agencies are indispensable; collective action accents early detection, primary prevention, and continuity of care. National mental health frameworks must earmark recurrent, non-discretionary funding specifically for the child and adolescent cohort, systematically enlarge mental health offerings embedded within schools, and concurrently advance digitally-mediated interventions under systematically stringent evaluation protocols.

Subsequent investigative agendas should foreground prospective, longitudinal designs, undertake comprehensive economic evaluations, and deploy participatory methodologies that foreground, rather than marginalize, children’s perspectives. Advancing implementation science, alongside policy-relevant scholarship, remains the linchpin for translating exemplary, context-sensitive evidence into measurable and sustainable practice across varied institutional and geographical constellations.

Conclusion

This systematic review corroborates the prevalence of mental health disorders in children and adolescents—including depression, anxiety, ADHD, and ASD—and the alarming reality of them being often overlooked. Disadvantage in social and economic status, mental disorders, and childhood trauma seem to be major risk factors, in varying degrees, all over the world.

Although CBT and school-based interventions hold promise, they are particularly constrained in low-resource settings because of accessibility, cultural responsiveness, and trained personnel shortages. These findings highlight the crucial importance of integrated, scalable, and child-centered mental health approaches.

This review enhances the existing body of knowledge to help devise policies and programs for strengthening early diagnosis, improving the care continuum, and fostering mental health promotion from childhood.

5. Recommendations

Expand Longitudinal Research

Future studies should assess the long-term benefits of mental health interventions for children and how these benefits differ across cultural and socioeconomic boundaries.

Strengthen Implementation Science

Developments should examine expenditures, real-world applications, and the ease of scaling and incorporating primary healthcare and educational systems.

Emphasize Digital Equity

Digital mental health interventions should be designed to be socially usable, ecologically sustainable, and financially low burden in disadvantaged locations.

Increase Child and Youth Participation in Program Design

Future programs must be co-designed with children and adolescents to enhance relevance, acceptability, and effectiveness.

Concentrate on Understudied Groups

More work is needed on children with disabilities, in conflict settings, and other marginalized populations, who are often overlooked in the bulk of mental health work.

Advance Shared Collaborative Work

There should be a continuous, integrated response to mental health and illness across the education, health, and social work sectors.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable. This study is a systematic review of previously published literature and does not involve human participants or the collection of primary data.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Materials

All data analyzed during this review are included in the published articles referenced within the manuscript. No new datasets were generated.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Authors’ Contributions

Somia Sarfraz was solely responsible for data collection, interpretation, and drafting the main sections of the manuscript. Nabeel Amjad contributed to the analysis and development of the discussion section. Mukaram Anees Awan assisted with overall proofreading and quality control of the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version.

Acknowledgements

The author extends sincere appreciation to Dr. Syed Muneeb Anjum and Dr. Muhammad Faisal Nadeem for their valuable academic guidance and encouragement throughout the development of this systematic review. Their insights and support significantly contributed to the quality and completion of this work.

List of Abbreviations

| ACEs |

Adverse Childhood Experiences |

| ADHD |

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder |

| ASD |

Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| CBT |

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy |

| COVID-19 |

Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| DALYs |

Disability-Adjusted Life Years |

| DSM-5 |

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition |

| HICs |

High-Income Countries |

| LMICs |

Low- and Middle-Income Countries |

| mhGAP |

Mental Health Gap Action Programme |

| NGOs |

Non-Governmental Organizations |

| OECD |

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| SEL |

Social-Emotional Learning |

| UNICEF |

United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

References

- Barry, M. M., Clarke, A. M., Jenkins, R., & Patel, V. (2013). A systematic review of the effectiveness of mental health promotion interventions for young people in low and middle income countries. BMC public health, 13(1), 835. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, K., Gregory, J. D., Walker, I., Lambe, S., & Salkovskis, P. M. (2017). Cognitive behaviour therapy for health anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Behavioural and cognitive psychotherapy, 45(2), 110-123. [CrossRef]

- Cortese, S., Adamo, N., Del Giovane, C., Mohr-Jensen, C., Hayes, A. J., Carucci, S.,... Coghill, D. (2018). Comparative efficacy and tolerability of medications for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children, adolescents, and adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 5(9), 727-738. [CrossRef]

- Costello, E. J., Mustillo, S., Erkanli, A., Keeler, G., & Angold, A. (2003). Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Archives of general psychiatry, 60(8), 837-844. [CrossRef]

- Das, J. K., Salam, R. A., Lassi, Z. S., Khan, M. N., Mahmood, W., Patel, V., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2016). Interventions for adolescent mental health: an overview of systematic reviews. Journal of adolescent health, 59(4), S49-S60. [CrossRef]

- Fazel, M., Hoagwood, K., Stephan, S., & Ford, T. (2014). Mental health interventions in schools in high-income countries. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(5), 377-387. [CrossRef]

- Feigin, V. L., Vos, T., Nair, B. S., Hay, S. I., Abate, Y. H., Abd Al Magied, A. H.,... Abdullahi, A. (2025). Global, regional, and national burden of epilepsy, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. The Lancet Public Health, 10(3), e203-e227. [CrossRef]

- Gowers, S. G., & Cotgrove, A. J. (2003). The future of in-patient child and adolescent mental health services. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 183(6), 479-480.

- Green, J. G., McLaughlin, K. A., Berglund, P. A., Gruber, M. J., Sampson, N. A., Zaslavsky, A. M., & Kessler, R. C. (2010). Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication I: associations with first onset of DSM-IV disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 67(2), 113-123. [CrossRef]

- Gulliver, A., Griffiths, K. M., & Christensen, H. (2010). Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: a systematic review. BMC psychiatry, 10(1), 113. [CrossRef]

- Hollis, C., Falconer, C. J., Martin, J. L., Whittington, C., Stockton, S., Glazebrook, C., & Davies, E. B. (2017). Annual Research Review: Digital health interventions for children and young people with mental health problems–a systematic and meta-review. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, 58(4), 474-503. [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R. C., Amminger, G. P., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Lee, S., & Ustün, T. B. (2007). Age of onset of mental disorders: a review of recent literature. Curr Opin Psychiatry, 20(4), 359-364. [CrossRef]

- Kieling, C., Baker-Henningham, H., Belfer, M., Conti, G., Ertem, I., Omigbodun, O.,... Rahman, A. (2011). Global mental health 2: child and adolescent mental health worldwide: evidence for action. The Lancet, 378(9801), 1515.

- Lawrence, D., Johnson, S., Hafekost, J., De Haan, K. B., Sawyer, M., Ainley, J., & Zubrick, S. R. (2015). The mental health of children and adolescents. Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing. Canberra: Department of Health.

- Loades, M. E., Chatburn, E., Higson-Sweeney, N., Reynolds, S., Shafran, R., Brigden, A.,... Crawley, E. (2020). Rapid systematic review: the impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(11), 1218-1239. e1213. [CrossRef]

- Merikangas, K. R., He, J.-p., Burstein, M., Swanson, S. A., Avenevoli, S., Cui, L.,... Swendsen, J. (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(10), 980-989. [CrossRef]

- Patel, V., Flisher, A. J., Hetrick, S., & McGorry, P. (2007). Mental health of young people: a global public-health challenge. The Lancet, 369(9569), 1302-1313. [CrossRef]

- Polanczyk, G. V., Salum, G. A., Sugaya, L. S., Caye, A., & Rohde, L. A. (2015). Annual research review: A meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, 56(3), 345-365. [CrossRef]

- Reiss, F. (2013). Socioeconomic inequalities and mental health problems in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Social science & medicine, 90, 24-31. [CrossRef]

- Sadler, K., Vizard, T., Ford, T., Goodman, A., Goodman, R., & McManus, S. (2018). Mental health of children and young people in England, 2017: Trends and characteristics.

- Singh, I., Filipe, A. M., Bard, I., Bergey, M., & Baker, L. (2013). Globalization and cognitive enhancement: emerging social and ethical challenges for ADHD clinicians. Current psychiatry reports, 15(9), 385. [CrossRef]

- Weare, K., & Nind, M. (2011). Mental health promotion and problem prevention in schools: what does the evidence say? Health promotion international, 26(suppl_1), i29-i69. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z., Huang, F., Koesters, M., Staiger, T., Becker, T., Thornicroft, G., & Ruesch, N. (2018). Effectiveness of interventions to promote help-seeking for mental health problems: systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological medicine, 48(16), 2658-2667. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).