1. Introduction

Complex numbers, combined with linear algebra, form the core mathematical framework for quantum computing. The complex number set is used to describe qubit states, the unitary transformations (or quantum gates) that manipulate qubit states, and provides quantum computers with a way to describe unique quantum properties (such as phase, interference and unitary evolution) [

1,

2]. Nevertheless, current quantum computing, based on standard complex numbers, is limited by the inability to divide by zero [

3]. Whilst this is a very deep and widely accepted mathematical constraint, this does have direct implications for quantum computing capabilities [

4].

For example, computer simulations of physical systems sometimes involve singularities. Particularly in high energy physics, cosmology, or even certain material properties at extreme conditions, can exhibit singularities in mathematical computations used to describe these systems [

5,

6]. A quantum computer capable of consistently handling division by zero could directly simulate these phenomena [

7]. However, this is currently impossible and requires heavy approximation [

8].

Additionally, some quantum field theories grapple with infinities [

9]. Any number set that can be used to enable division by zero in calculations in a consistent logical way and give meaning to these infinities within a computational context, could unlock simulations of complex quantum systems that are currently beyond reach [

10].

Moreover, qubits that represent quantum information do not encode infinities or indeterminate states in a non-contradictory way [

11]. A mathematical framework that could be used to create new types of qubits (capable of logically and consistently defining division by zero) could lead to a new way of encoding information beyond the standard basis states [

12].

Thirdly, it is often the case that mathematical solutions to complex real-world problems are sometimes not unique or stable because of existing singularities in these solutions [

13]. A quantum computer with the capability of handling division by zero could provide a consistent way to find meaningful solutions to such problems [

14].

Finally, optimization problems often involve searching for vast landscapes, sometimes with infinite peaks or valleys [

15]. If division by zero could navigate these consistently, it might lead to an even more powerful optimization algorithm Particularly in the areas of cryptography, cosmology, logistics, finance, and material design [

16].

Division by zero needs to be incorporated into quantum computing to realize the advantages of having this operation on quantum computers. As a starting point, this paper utilizes two tools: (1) semi-structured complex numbers and (2) Pauli matrices.

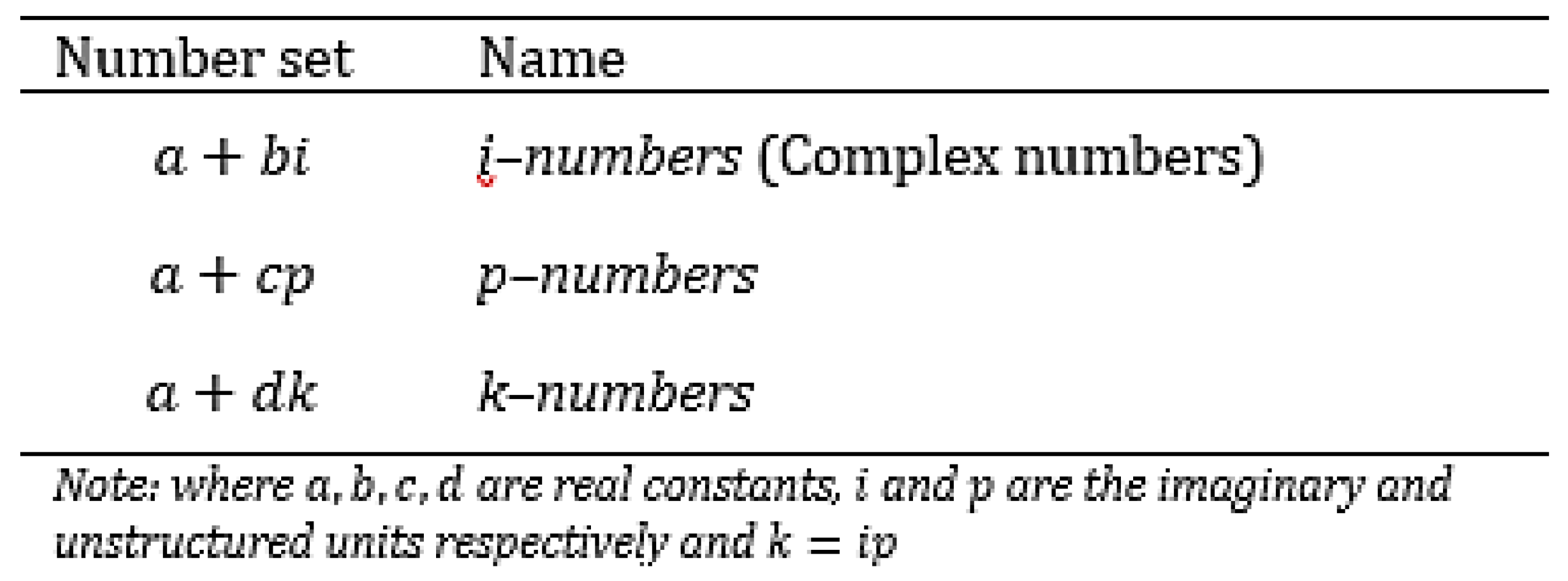

1.1. Semi-Structured Complex Numbers

Semi-structured complex numbers are numbers that were created specifically to enable division by zero in regular algebraic equations [

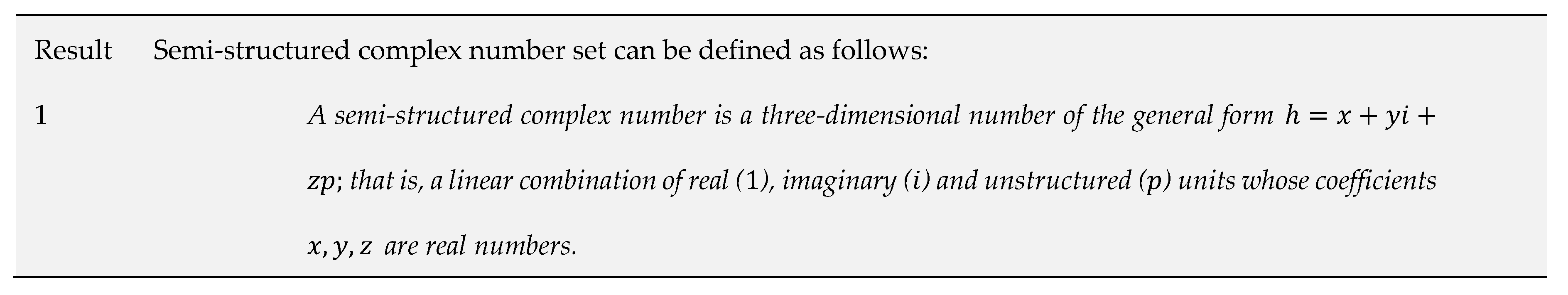

17]. Semi-structured complex number set can be defined as follows:

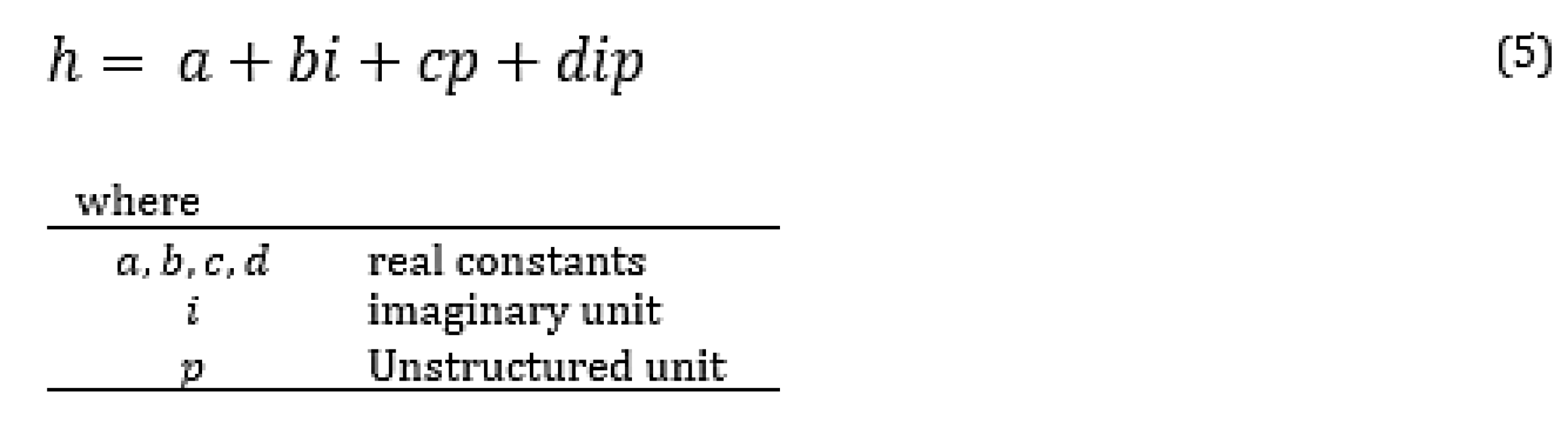

A semi-structured complex number is a three-dimensional number of the general form

that is, a linear combination of real (), imaginary () and unstructured () units whose coefficientsare real numbers.

The number

is called semi-structured complex because it contains a structured complex part

and an unstructured part

. Integer powers of

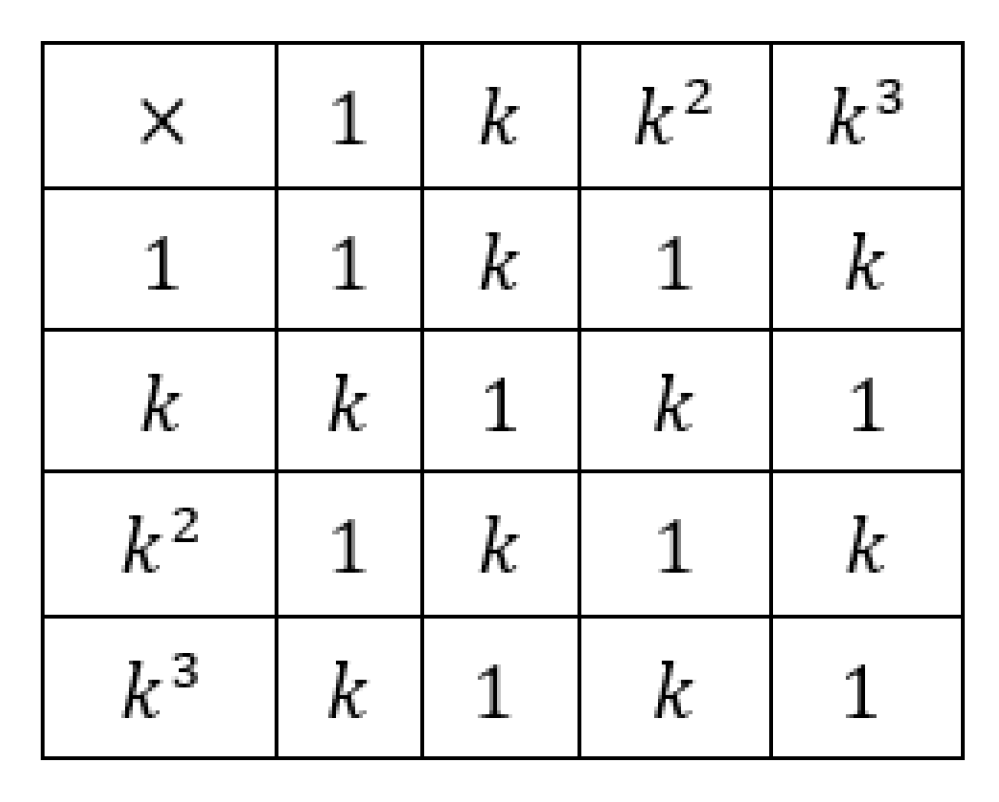

yield the following cyclic results:

Given the definition of semi-structured complex numbers, it can clearly be seen that infinity (represented by division by zero) is encoded within the number and can be dealt with algebraically. Other important characteristics of semi-structured complex numbers is given in

Table A1 in

Appendix A1.

Semi-structured complex numbers can be seen as vectors in a 3-dimensional Euclidean semi-structured complex space [

18]. This representation enables vector operations (such as addition, dot product, inner product) to be performed on semi-structured complex numbers [

19]. This implies that semi structured complex numbers can be used within linear algebra, the algebra of quantum computing [

20].

The geometric properties of semi structured complex numbers as an extension of complex numbers make them ideal for being used within quantum computing. Since “” behaves like “” in that it has higher order cyclic behavior, it is possible to build quantum gates, quantum states, and protocols using the semi-structured complex number set.

1.2. Pauli Matrices

1.2.1. Origin and Meaning of the Pauli Matrices

Another tool that is necessary for the introduction of division by zero into quantum computing is the Pauli matrices [

21]. The Pauli matrices is a set of three

complex matrices that were created by physicist Wolfgang Pauli who introduced them as part of his work on the theory of spin in quantum mechanics [

22].

As a bit of background, in the early 20th century, the Stern–Gerlach experiment showed that electrons possess intrinsic angular momentum (spin) that can only take certain discrete values [

23]. However, traditional quantum mechanics (based on Schrödinger's equation) couldn't fully explain this property. Traditional quantum mechanics was formulated using wave mechanics. In wave mechanics, the basis vectors for angular momentum are

,

and

. Since traditional quantum mechanics could not fully explain the property of spin, a mathematically equivalent form of quantum mechanics had to be used. This form of quantum mechanics was called matrix mechanics.

Matrix mechanics proved very efficient in describing spin [

24]. With matrix mechanics the basis vectors for angular momentum were converted into an equivalent basis matrix form [

25]. These equivalent matrices were called Pauli matrices. The Pauli matrices have property of being Hermitian (meaning that the matrix is equal to its conjugate transpose) and unitary (the inverse of the matrix is equal to its conjugate transpose) [

26]. To convert a 3-dimensional vector

into a

Hermitian matrix, the following rule is applied:

Hence, the basis vector along the x-direction

can be written in matrix form as

Similarly, the basis vector along the y-direction

can be written in matrix form as:

And finally, the basis vector along the z-direction

can be written in matrix form as:

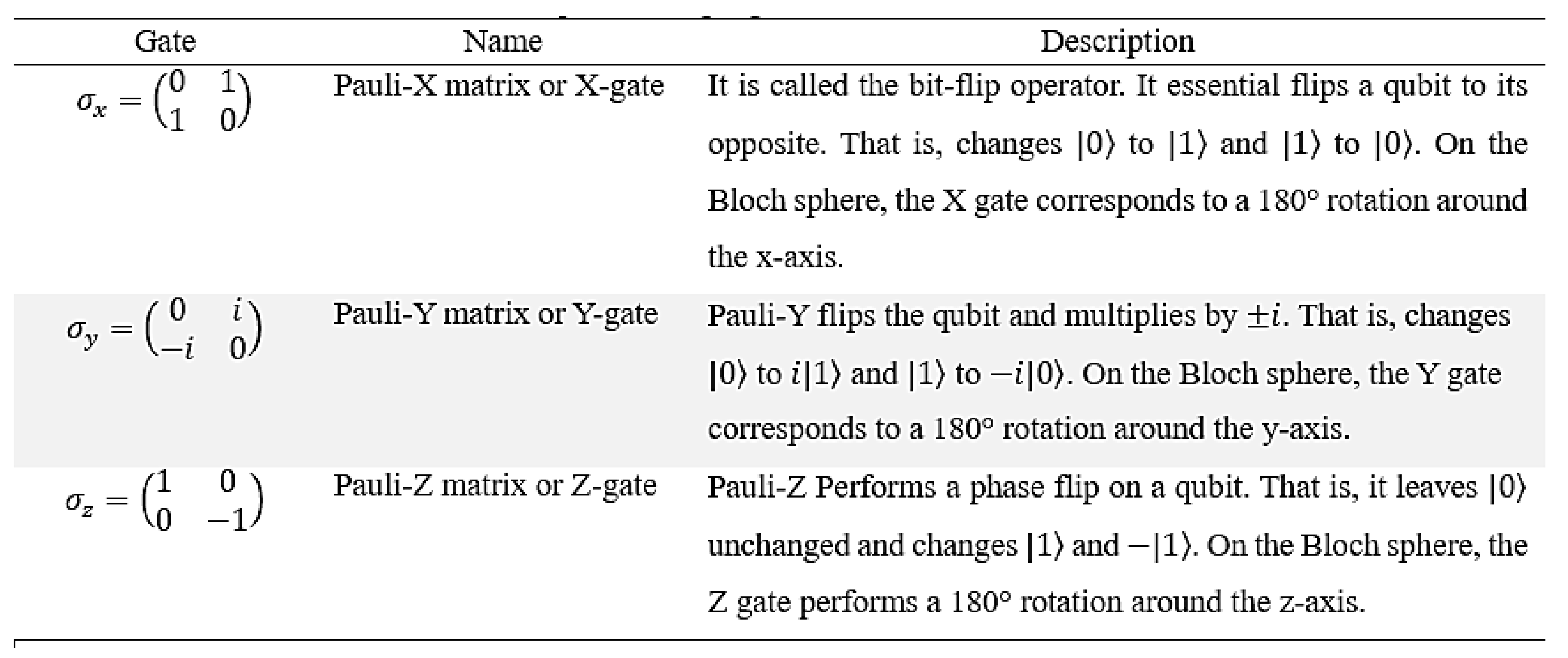

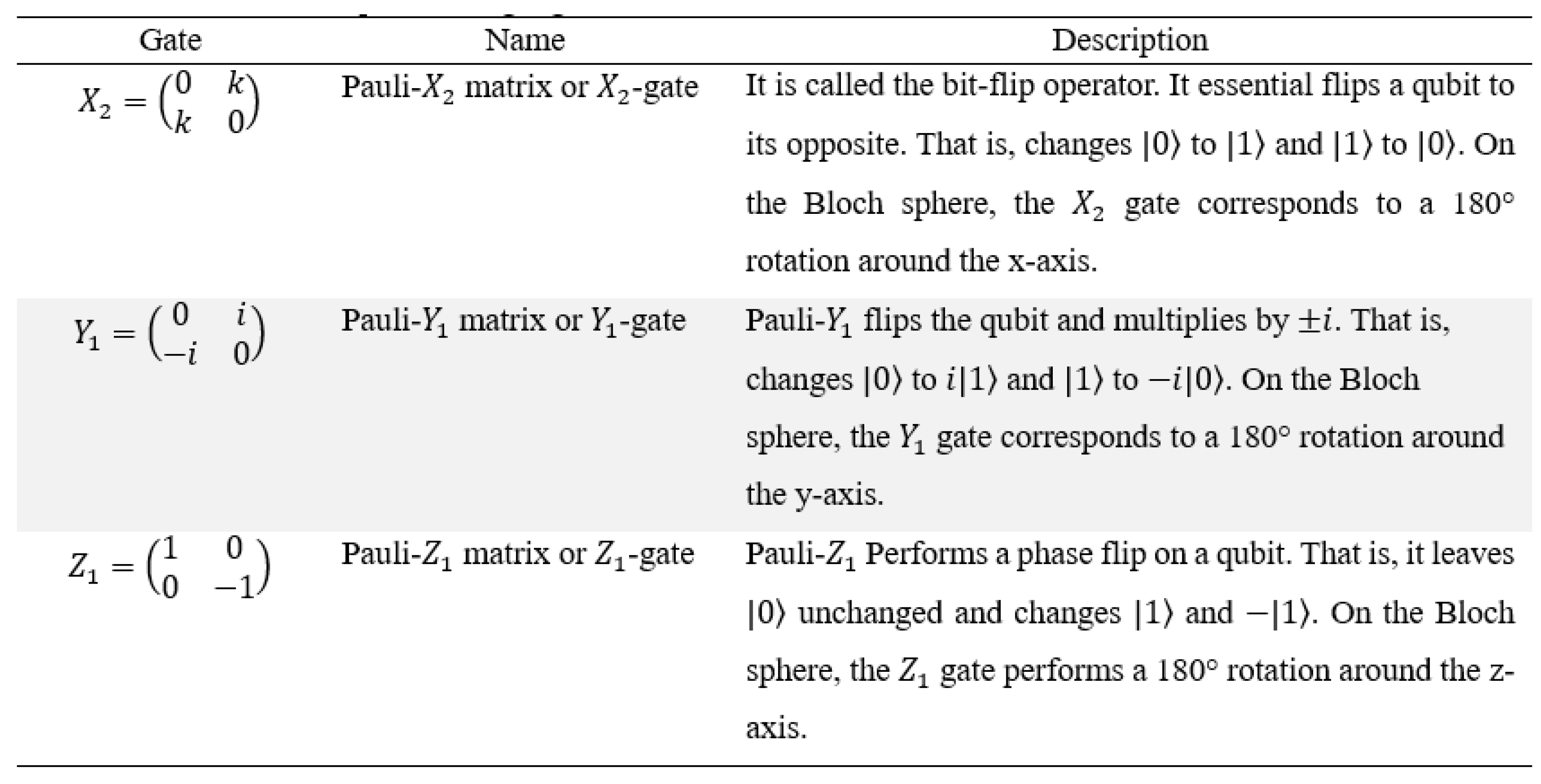

In quantum computing the Pauli matrices are used as fundamental quantum logic gates acting on qubits. In that form they are given new symbols and new names. The Pauli matrices used in quantum computing are given in

Table 1.

Any single qubit state can be represented as a linear combination of the Pauli matrices and the identity matrix [

27]. This is part of the formalism used to describe qubits in quantum computing. Pauli matrices are also considered SU(2) matrices. SU(2) in this case means “special unitary

matrices”; special means that the determinant of these matrices is 1 and unitary means that the conjugate transpose of the matrix is the same as its inverse [

28].

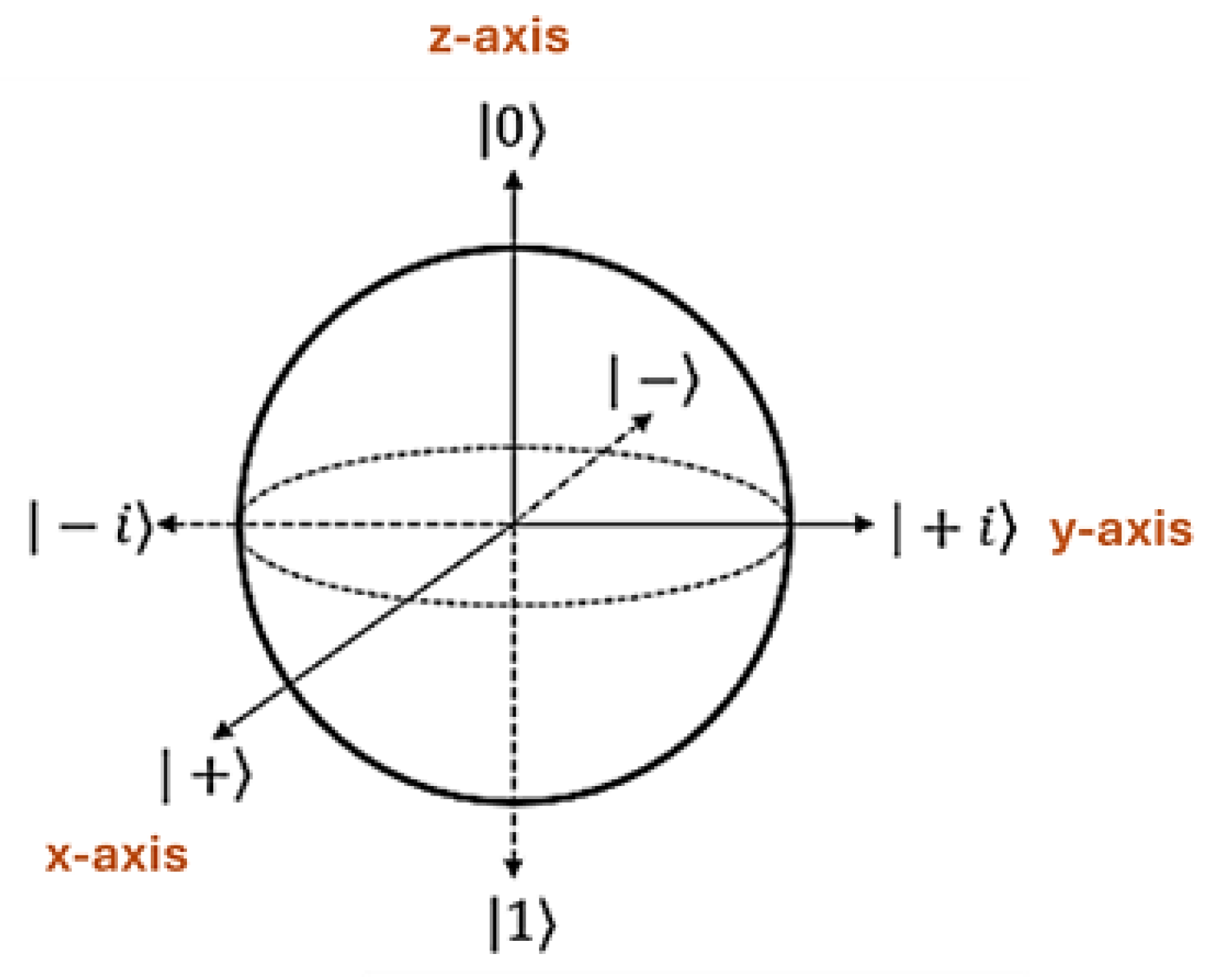

1.2.2. Using the Pauli Matrices to Construct a Bloch Sphere

Table 1 makes mention of Bloch sphere. A Bloch sphere is simply a visual representation of the state of a qubit as shown in

Figure 1.

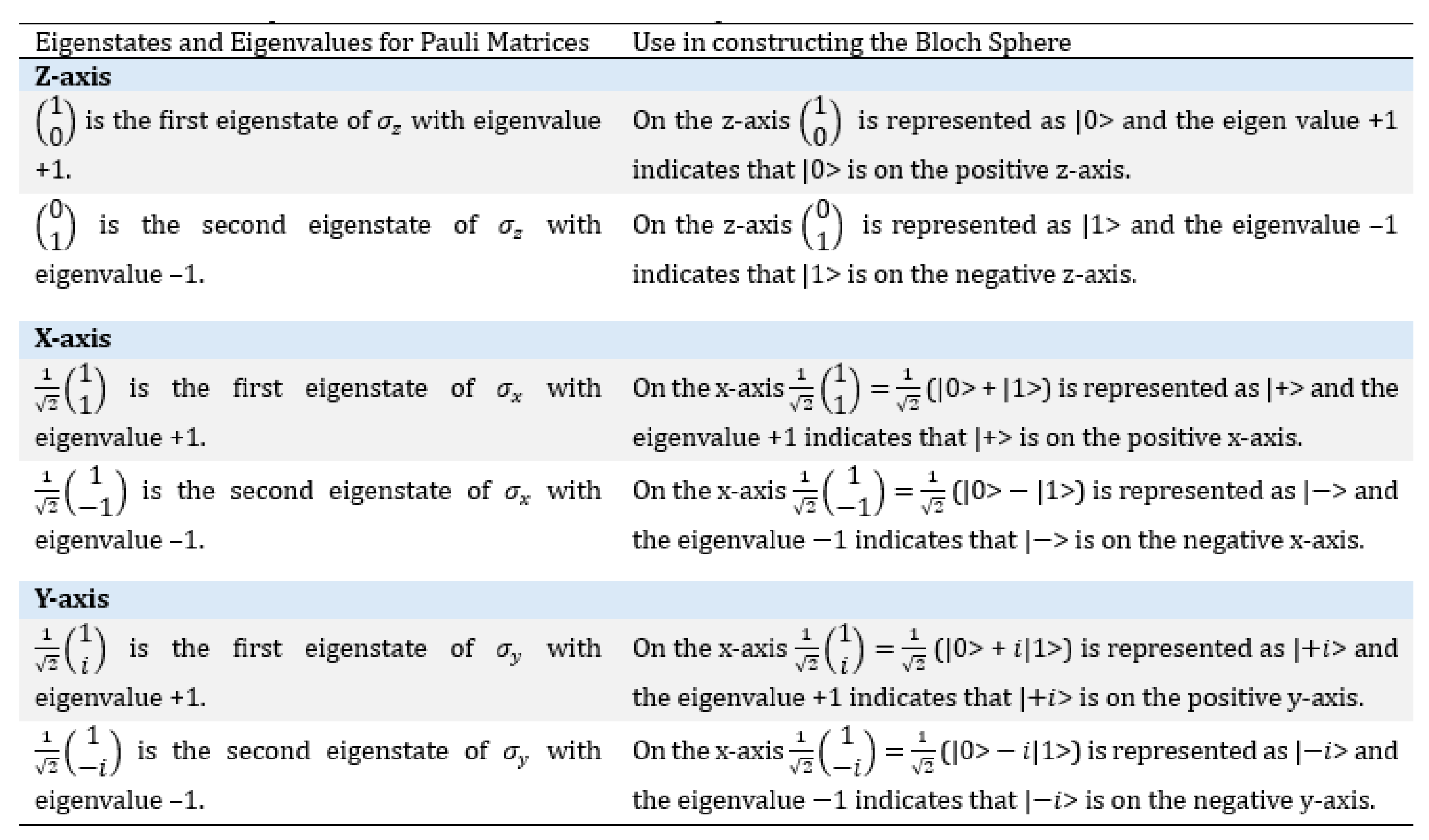

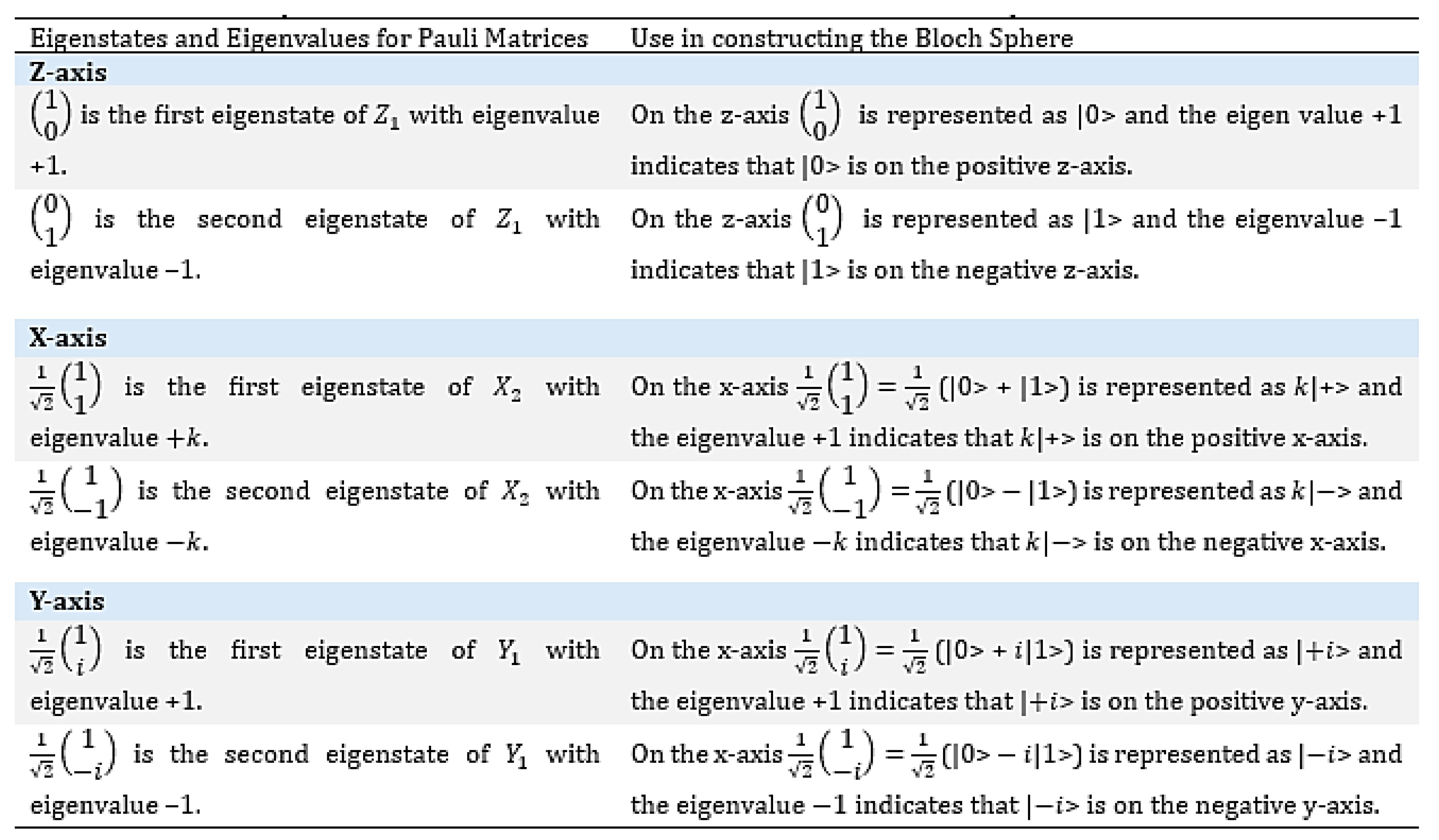

What is critical to know is how the Bloch sphere is derived from the Pauli matrices [

29]. The Bloch Sphere consists of three axes: x-axis, y-axis, and z-axis. The values and directions of each axis is constructed from the eigenstates and eigenvalues of the corresponding Pauli matrix [

30]. The relationship between the Pauli matrices and the construction of the Bloch sphere is given in

Table 2.

Table 2 highlights the fact that there's a very strong relationship between the eigenstates and eigenvalues of the Pauli matrices and the construction of the Bloch Sphere used to describe qubits.

1.3. Major Contributions

Given a basic understanding of quantum computing, semi-structured complex numbers, and Pauli matrices, the aim of this paper is to:

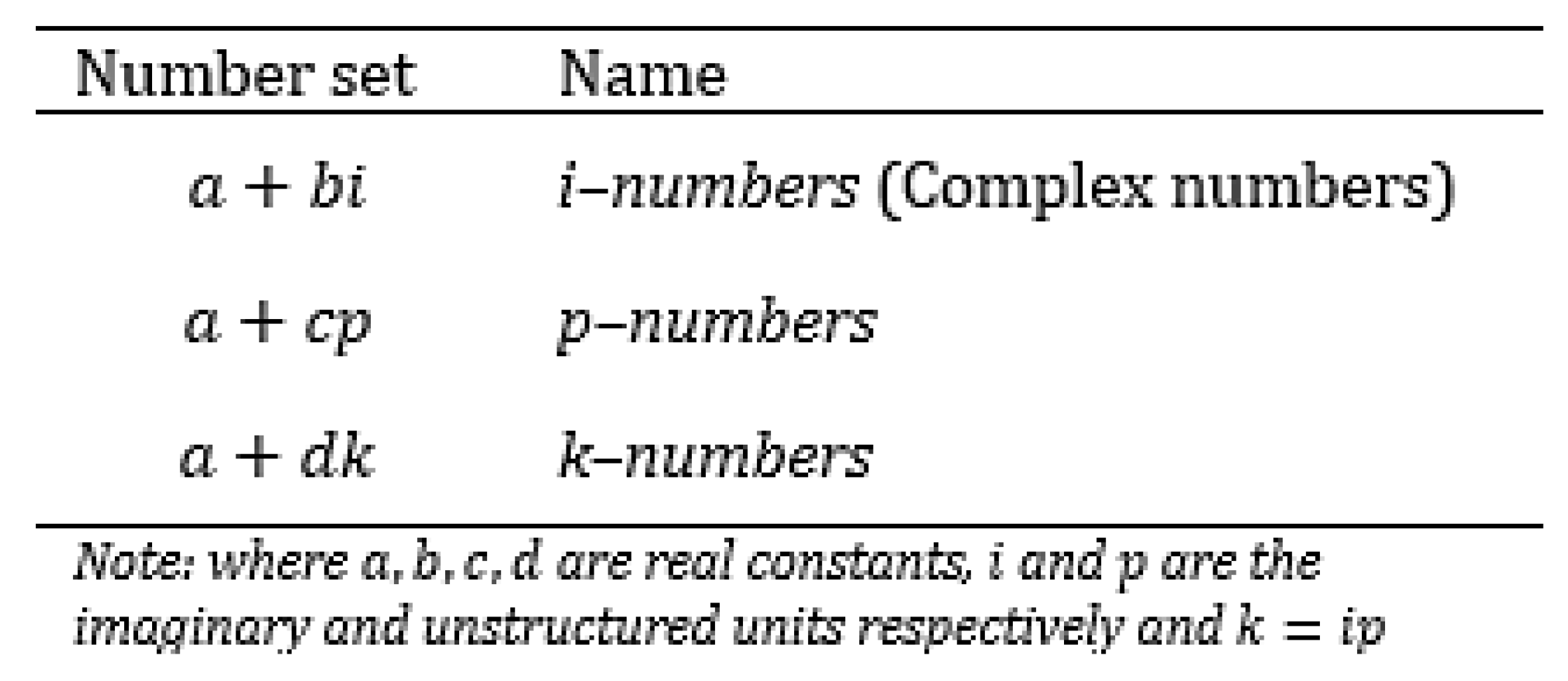

Use semi structured complex numbers to define three distinct number sets that can enable division by zero and simultaneously form four core foundational yet distinct mathematical frameworks for building quantum computers.

In the process of achieving this aim the following major contributions are made:

- 1.

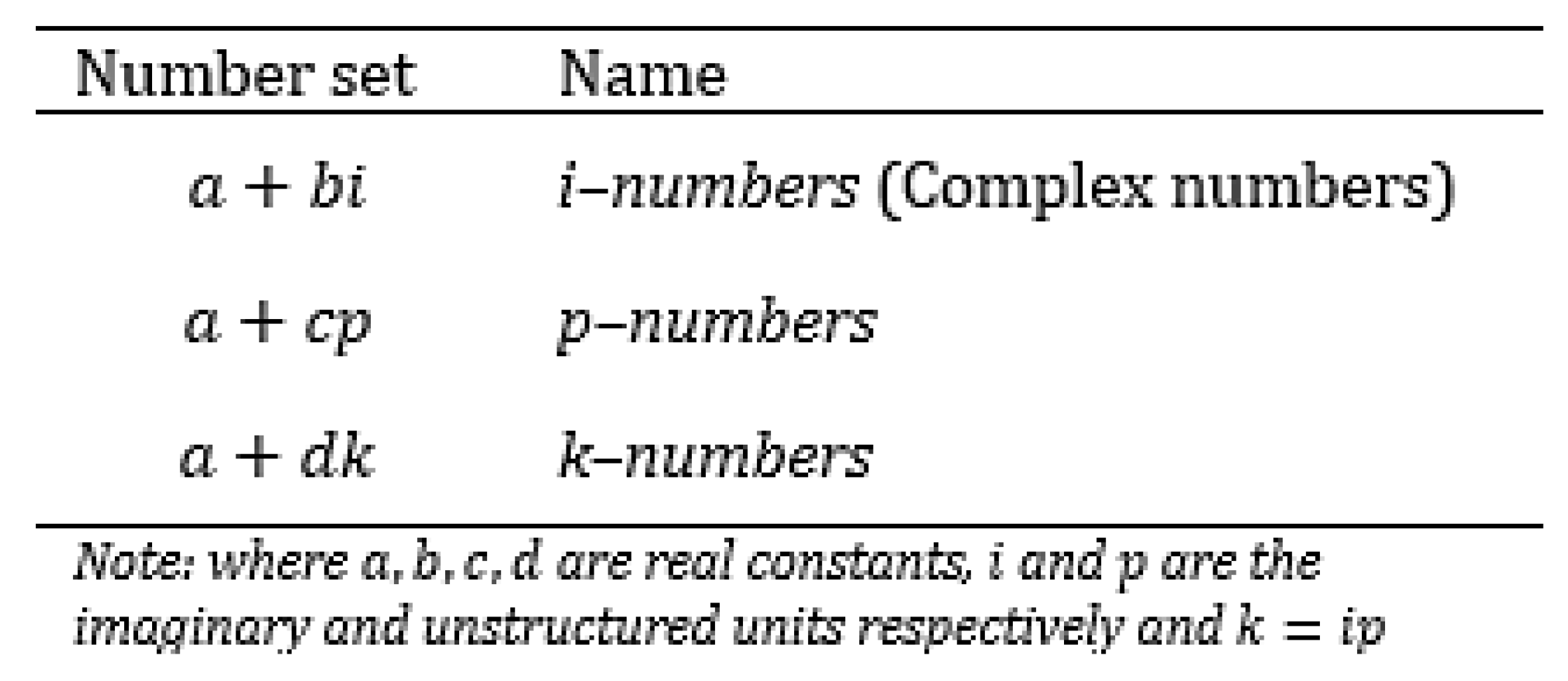

Using the 4D form of semi structured complex numbers (that is:

) to create three new number sets that are subsets of semi-structured complex numbers. These number sets are given in

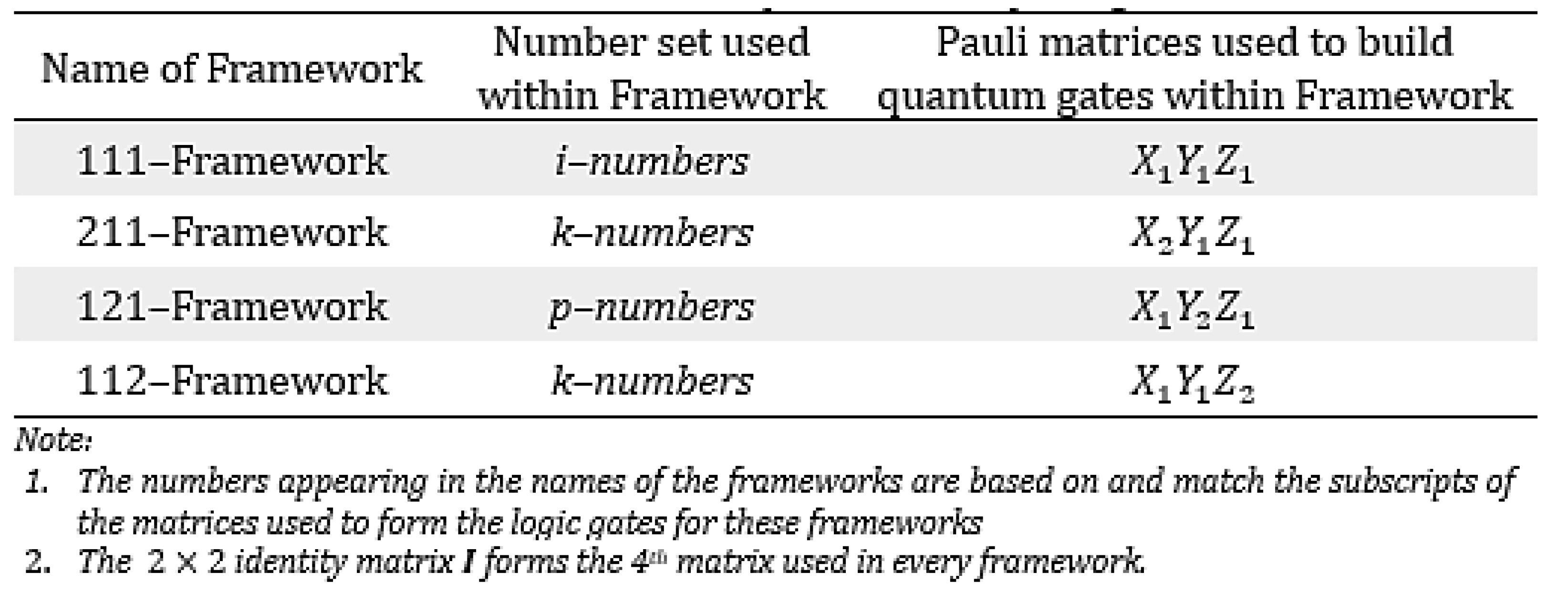

Table 3.

- 2.

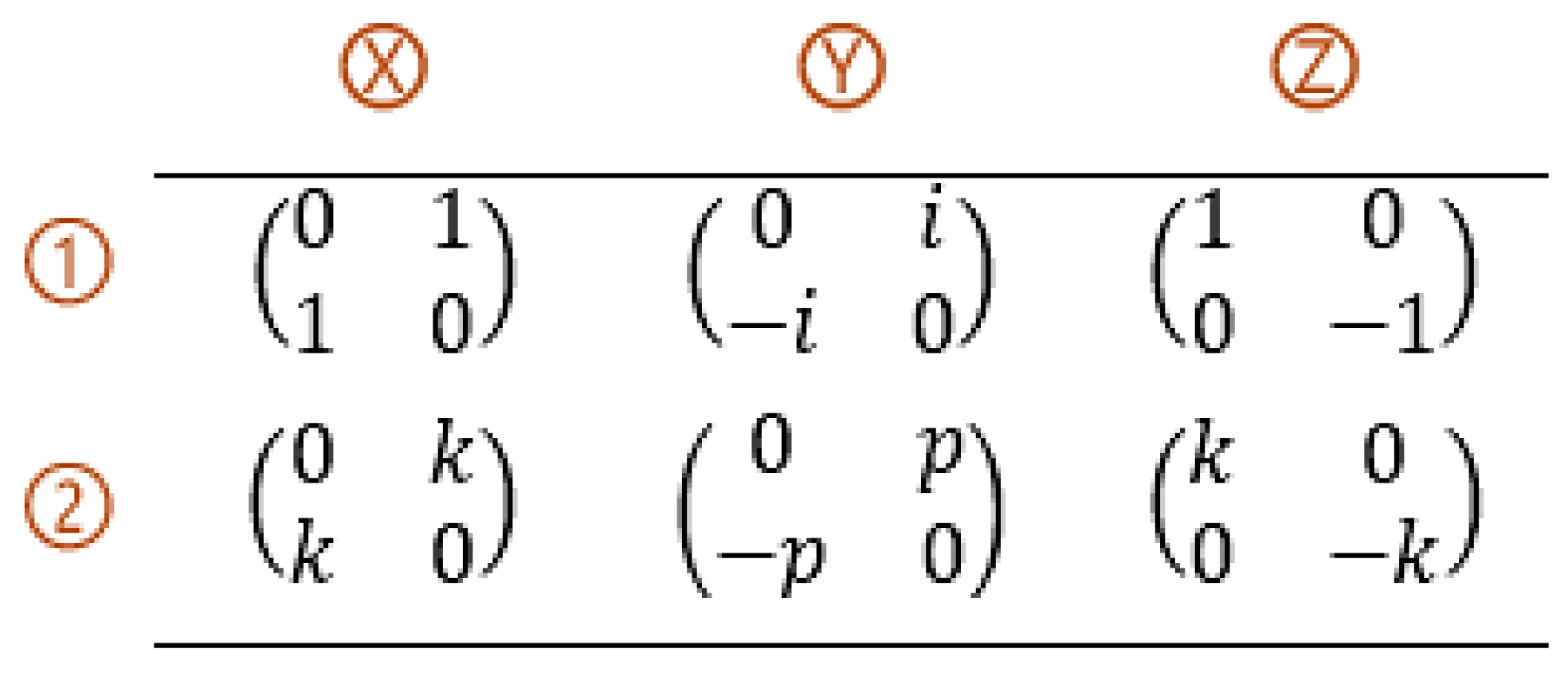

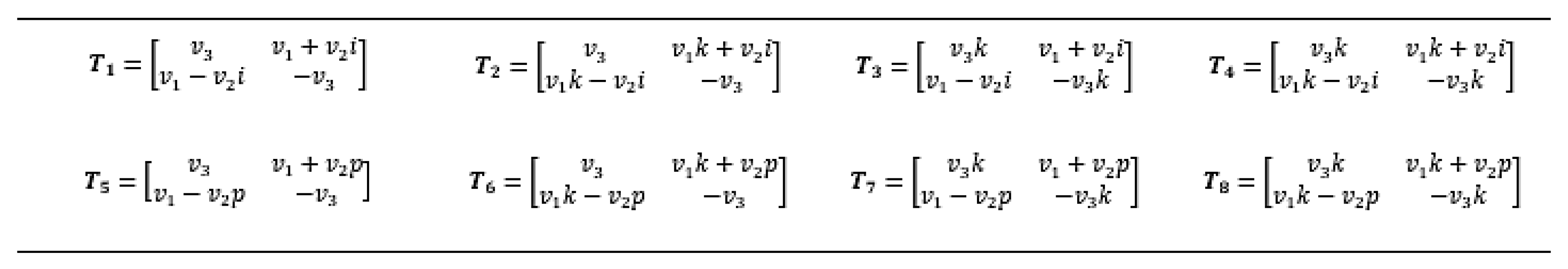

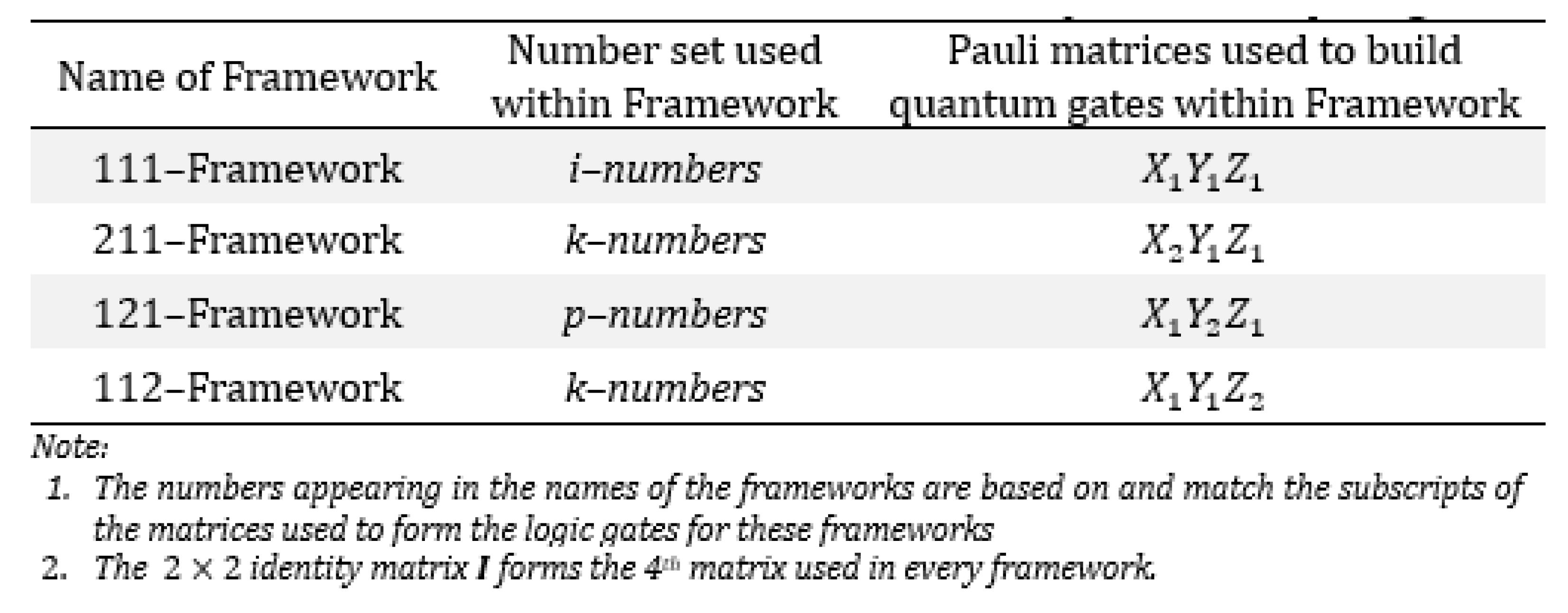

Use the new number subsets to define the Generalized Pauli Matrix Set consisting of six distinct special unitary matrices. The Generalized Pauli Matrix Set is given in

Table 4.

Each matrix in the table is named according to the column and row that it belongs to. For example, (pronounced “Pauli X two”). Addtionally, and so on. The positioning of these matrices in table is not arbitrary but is based on the method used to arrive at them; that is, the position of the matrices cannot change.

Using the number sets from Contribution 1 and the Generalized Pauli Matrix Set from Contribution 2 the following four mathematical frameworks were created. The frameworks are given in

Table 5. What differentiates each framework is the matrices used to create the logic gates for quantum computing and mathematical number sets that underline each framework.

Each of these frameworks offer distinct computational advantages. The last three frameworks enable division by zero within computation as well as within quantum logic circuits.

- 3.

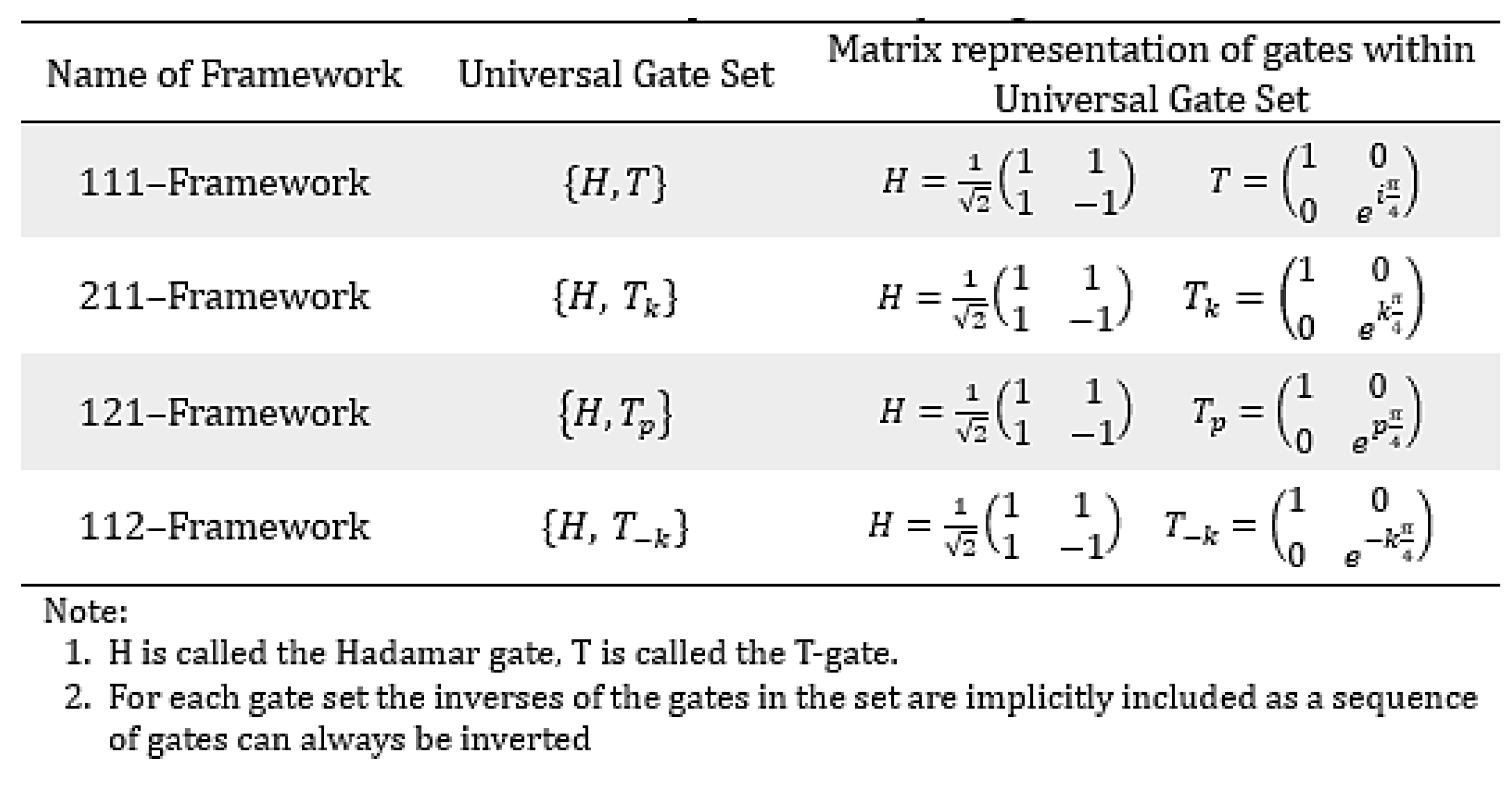

For each framework outlined in

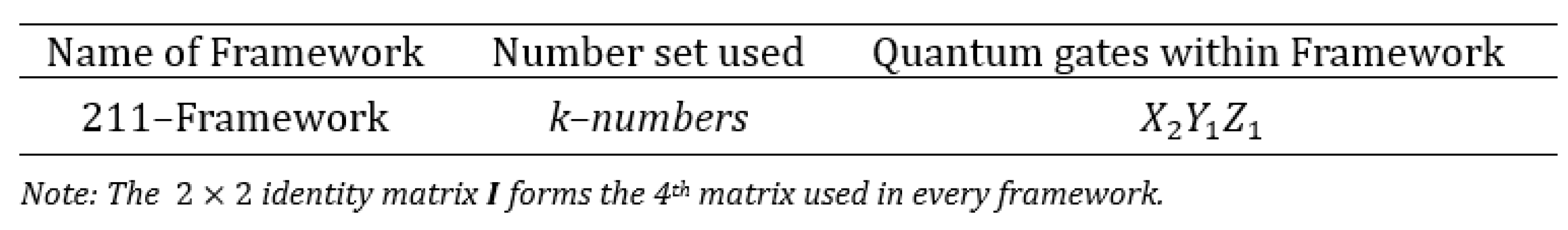

Table 5, a universal gate set (from which all other quantum gates and circuits can be built) was developed and proved to adhere to the Solovay Kitaev theorem. The theorem states that: “

if a set of single-qubit gates can generate a dense subgroup of SU(2), then any desired single-qubit gate can be approximated to an arbitrary precision using a sequence of gates from this finite set whose length scales poly-nominally in

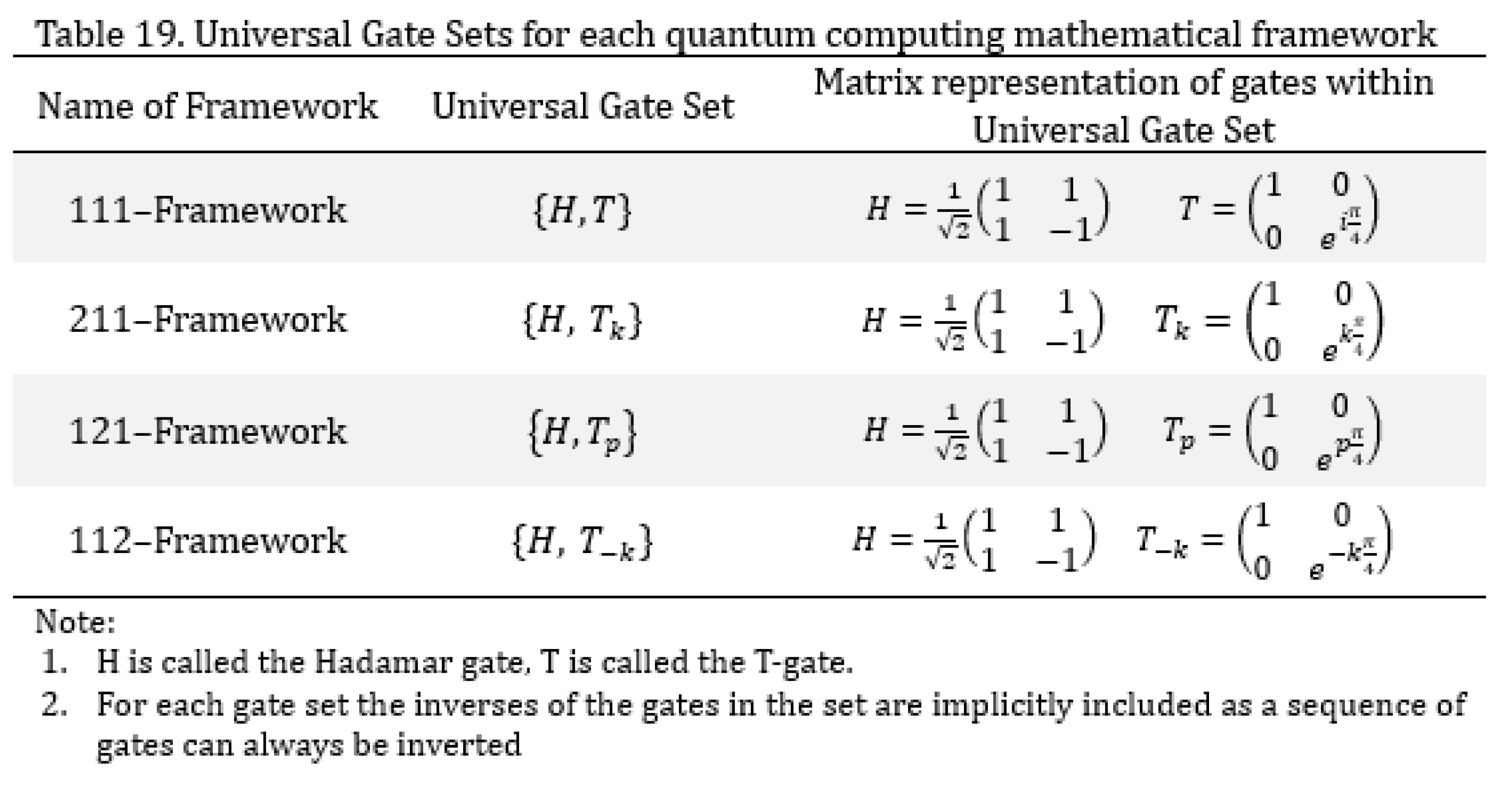

”. The universal gift set under each mathematical framework is given in

Table 6.

T

- 4.

As an example, the utility of one of the frameworks 211-Framework was demonstrated.

The rest of the paper is devoted to showing how in the process of achieving the aim the four major contributions were derived.

2. Defining Four Distinct Mathematical Frameworks of Quantum Computing

2.1. Characterizing the Three Distinct Subsets of Semi-Structured Complex Numbers

The fundamental representation of semi structured complex numbers is given in Equation (5).

Equation (5) this can be rewritten as

where

.

Semi structured complex numbers can be divided into 3 distinct subsets of numbers. These subsets are given in

Table 7.

Quantum computing is based on linear algebra. For a number set to be used within linear algebra it must satisfy 11 field axioms [

31]. Field axioms are a set of fundamental rules that define a mathematical structure called a field. In abstract algebra, a field is a set on which addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division (except by zero) are defined and behave in a way that allows us to do arithmetic in a consistent and predictable way. If a set with two operations (usually called "addition" and "multiplication") satisfies all these axioms, then it's a field. These 11 field axioms and proof that each number set obeys these axioms are given in

Table A2 and

Table A3 in

Appendix A2. Additionally, whilst these number sets share real numbers as common elements, what makes the number sets distinct is that no one number set can be used on its own to fully derive another number set [

32].

2.2. Characterizing the “Generalized Pauli Matrix Set”

To define the different mathematical frameworks for quantum computing the next step was to consider the possible Pauli type matrices that can be formed from the number sets defined in given

in

Table 7.

Table 7.

New number sets.

Table 7.

New number sets.

It is necessary to demonstrate that each of these number sets can be used to create Pauli type matrices because it is those matrices that are necessary to represent physical quantities in quantum computing and also to create quantum logic gates and consequently quantum logic circuits for quantum computers.

Therefore, these Pauli type matrices for each number set must be both Hermitian and Unitary. Hermitian matrices are essential for representing observables (physical quantities that can be measured) and unitary matrices are essential for representing quantum gates (operations on qubits). Matrices that carry both of these properties can be used within quantum computing for representing superposition, interference, and error correction and stabilization codes for single-qubit and multi-qubit gate operations and measurements.

When handling the complex number set (the

-numbers) it was found that to convert 3D-vectors

into

Pauli matrices the following formulation is usually used:

The transformation

is a complex number (or

i–numbers) based matrix; this can easily be seen from the top right hand corner element in the matrix which has the complex number form

. Therefore, the transformation for the basis vectors

,

,

into

matrices using transformation

gives:

are the Pauli matrices. As stated earlier these matrices are both Hermitian and Unitary. These matrices along with the identity matrix are some of the matrices used to form quantum logic gates for the current quantum computing paradigm.

However, the transformation

is not the only matrix transformation that can be used to create

Hermitian unitary matrices. Using the

-numbers and

-numbers, seven other transformation matrices can be created. The complete set of transformation matrices that can be created from the three number sets

-numbers,

-numbers and

-numbers is given in

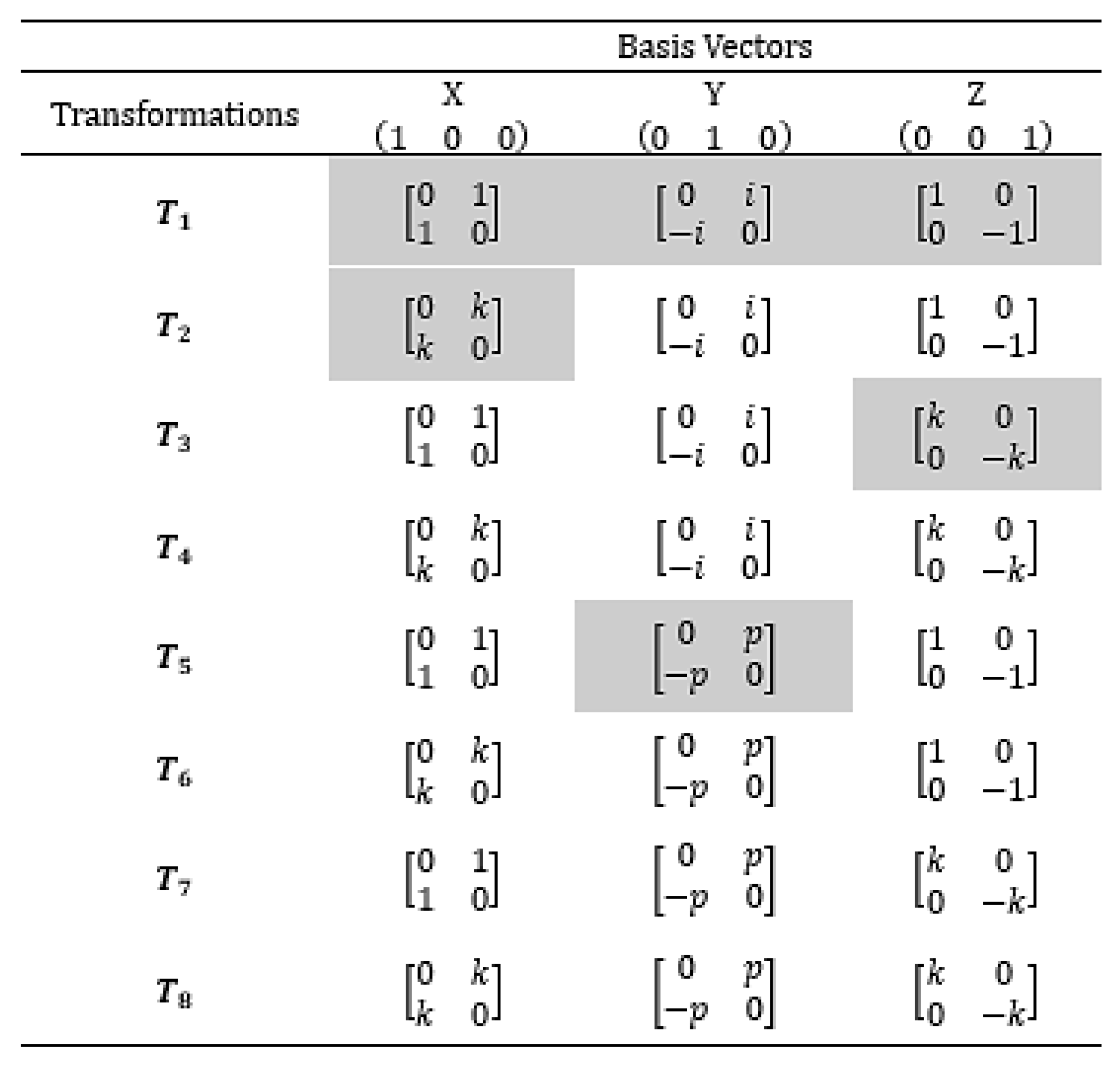

Table 8.

Proof that the transformations in

Table 8 form

Hermitian unitary matrices is given in

Appendix A3. Each transformation matrix in

Table 8 was used to convert each basis vector

,

,

into Hermitian unitary matrices. The result is given in

Table 9.

Table 9 has 24 entries. The entries highlighted in grey are the unique entries of the table that span the entire table. Every other entry is a copy of one of the entries highlighted in grey. This observation means that

Table 9 can be greatly simplified.

To simplify

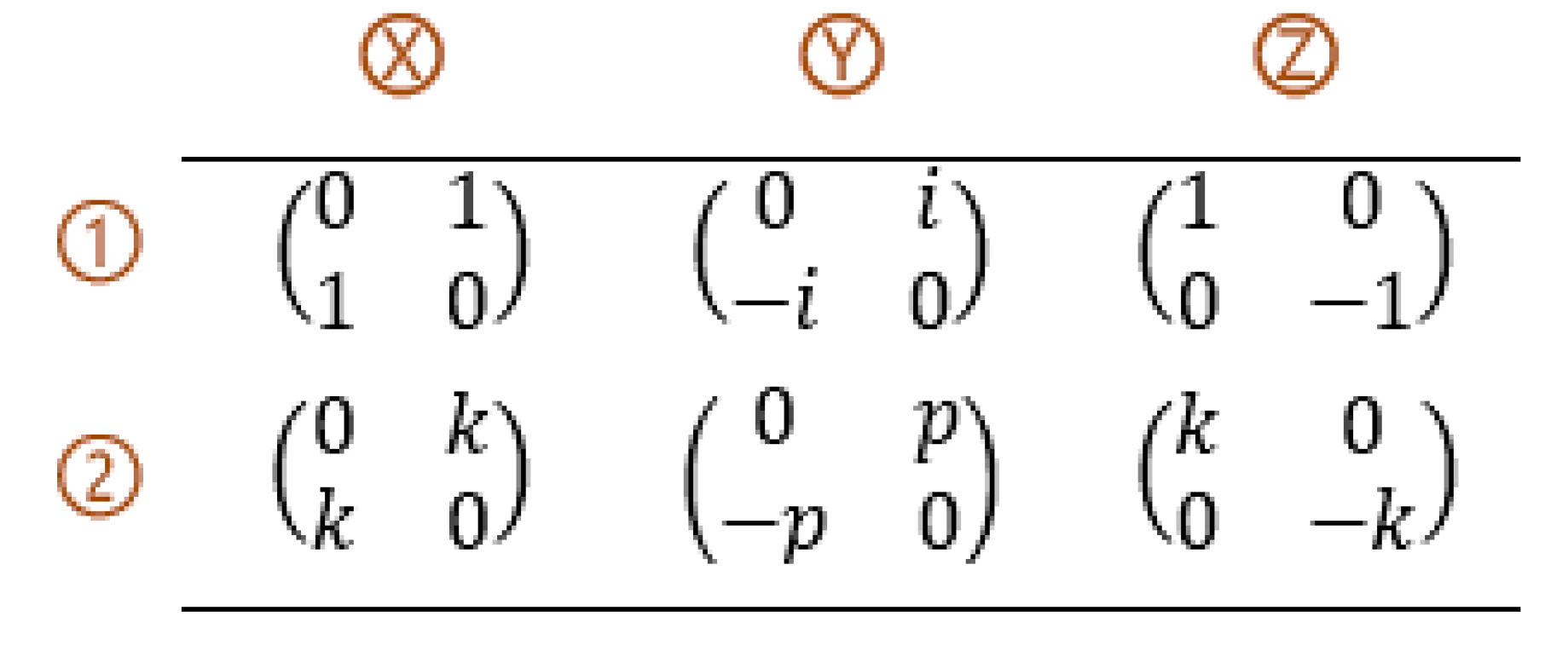

Table 9, columns X, Y, Z are kept. Each column has two highlighted unique matrices; two unique X matrices, two unique Y matrices and two unique Z matrices. Using this observation

Table 9 can be condensed to give

Table 10.

Table 10 is called the Generalized Pauli Matrix Set. Each matrix in the table is named according to the column and row that it belongs to. For example,

(pronounced “Pauli X two”),

and so on. The positioning of the matrices in table is not arbitrary but is based on the method used to arrive at them. Therefore, the position of the matrices does not change.

2.3. Characterizing the Foundational Mathematical Frameworks

Using the number sets in

Table 7 and the Generalized Pauli Matrix Sets from

Table 10, four mathematical frameworks were created. These frameworks are given in

Table 11.

What differentiates each framework is the matrices used to create the logic gates for quantum computing and mathematical number sets that underline each framework. Each of these frameworks offer distinct computational advantages. For example, the last three frameworks enable division by zero within computation as well as within quantum logic circuits.

Each mathematical framework has a unique set of logic gates that can be to create quantum logic circuits and quantum algorithms. Because each mathematical framework is distinct, quantum computers based on one framework are fundamentally distinct from quantum computers based on another framework. Nevertheless, all quantum computing (irrespective of the mathematical framework used to underline its operation) will still operate on the basic principles of linear algebra.

Since the foundations of quantum computing is well established for the 111–Framework (that is for complex numbers), the basic foundations of the other frameworks, that is, the 211–Framework, 121–Framework, and 112–Framework needs to be examined. Since it is a bit cumbersome to examine all three frameworks within one paper, it suffices to examine one of these frameworks as an example of how the other two frameworks can be developed and integrated within quantum computing. The 211-Framework was chosen to be examined.

3. Foundations of Quantum Computing with 211–Framework

3.1. Core Axioms and Structural Properties

The basic characteristic of the 211–Framework is given in

Table 12.

The elements in the k-number set can be defined as

According to the field axioms proofs given in

Appendix A1, k-number set is closed under multiplication and addition and contains the identity element 1 and a nontrivial element

. The multiplication rules for the k-number set are commutative and 2-cyclic as shown in

Table 13.

In addition to a well-defined multiplication table, the

–number has a well-defined conjugate; that is,

. Additionally, if

is a

–number then the norm of

is:

3.2. k-Qubits and Vector Spaces

As a basic element the k–qubit is defined over

k–numbers as Equation (11).

k-qubit states are written using Dirac notation where

and

represent the "basis states" (analogous to 0 and 1). The equation above represents the superposition between the basis states. Normalization (that is, the magnitude (or length) of the state vector) must be equal to 1. In terms of the inner product this given as:

Superpositions as shown in Equation (11) cannot be expressed in terms of complex numbers (that is, i–numbers), allowing a richer spectrum of interference. These k-qubits suggest a "supra-quantum" theory; that is, physical theory that is "stronger" or "more general" than standard quantum mechanics yet still respects some fundamental physical principles that quantum mechanics itself adheres to. This expands the structure of superposition and enabling new classes of computational or physical states.

3.3. k-Pauli Operators as Building Blocks for 211–Framework of Quantum Computing

Since the 211–Framework of quantum computing is considered, based on

Table 11, the gates that would be used in this framework is

. This is given in Equation (13).

These gates are considered Pauli matrices within the 211–Framework of quantum computing; that is Pauli-, Pauli-, Pauli-. These quantum gates are the operations that manipulate k-qubit states. They are the quantum equivalent of logic gates in classical computing.

In quantum mechanics there is an operation called the commutator operator. This operation gives the extent to which two operators (or matrices) can be measured simultaneously with arbitrary precision. This is given by the equation

where A and B are operators or matrices. If the final value of the commutator is zero, then this means operators A and B can be measured simultaneously with arbitrary precision. The

gates satisfy the following commutator properties shown in Result (14).

Where

is the unstructured unit

. Proof of these properties is given in

Appendix A3.

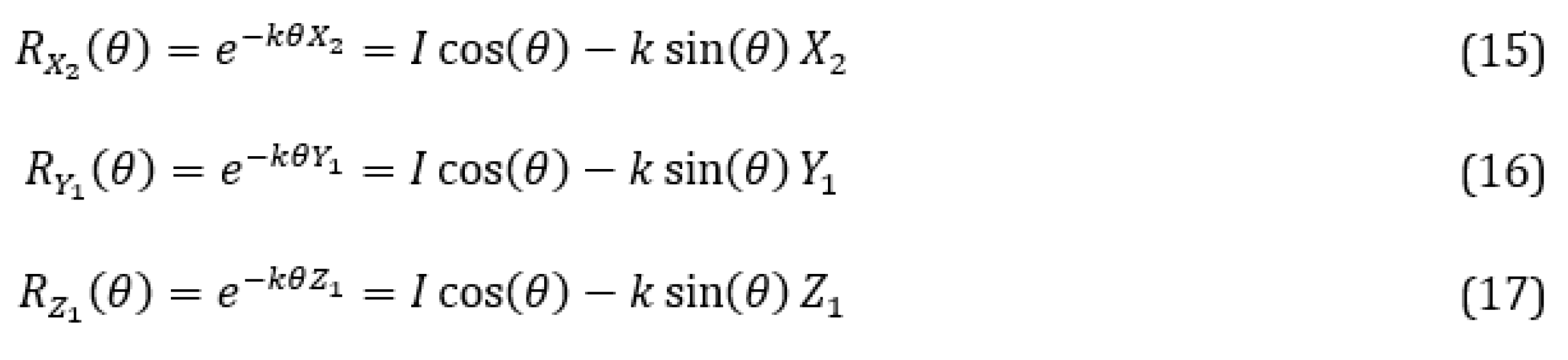

The Pauli matrices outlined here are "unitary rotations"; that is, transformations that rotate the quantum state vector around in its Hilbert space, without changing its length. This "rotation" changes the probability amplitudes and phases of the basis states. The amount of rotation produced by each gate is given in

Table 14.

The gates listed in

Table 14 are called Standard single qubit gates. These single qubit gates are fundamental as they are used to build and or manipulate other gates such as Rotation gates, Pauli-power gates, Quarter turns and Hadamard gates. For example, the three Pauli-matrices can be used to create unitary Pauli-rotation matrices

,

and

that rotate a state vector by an arbitrary angle about the corresponding axis in the Bloch sphere. The three unitary rotations are shown below in Equation (15) to Equation (17).

Here is the identity matrix.

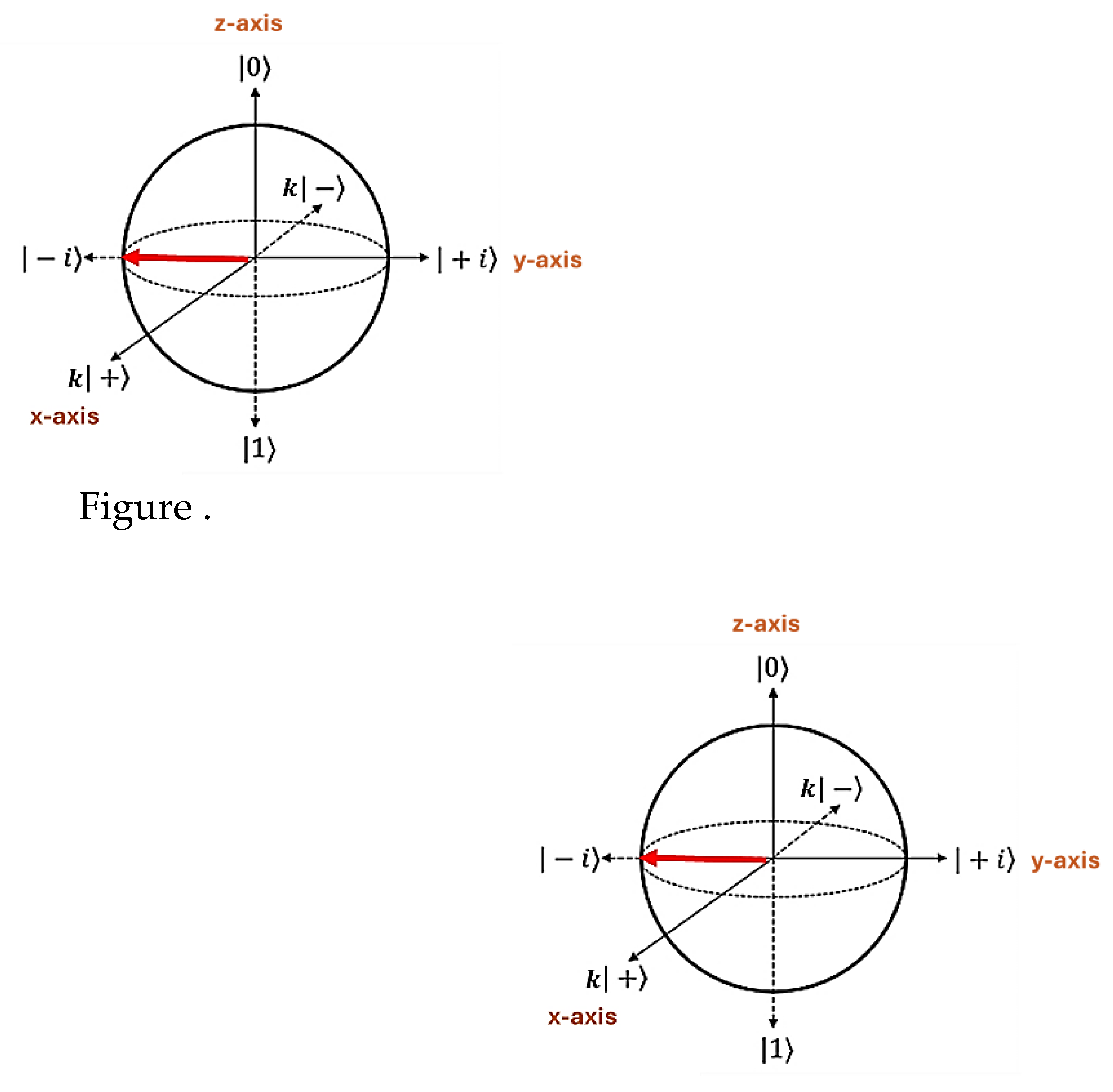

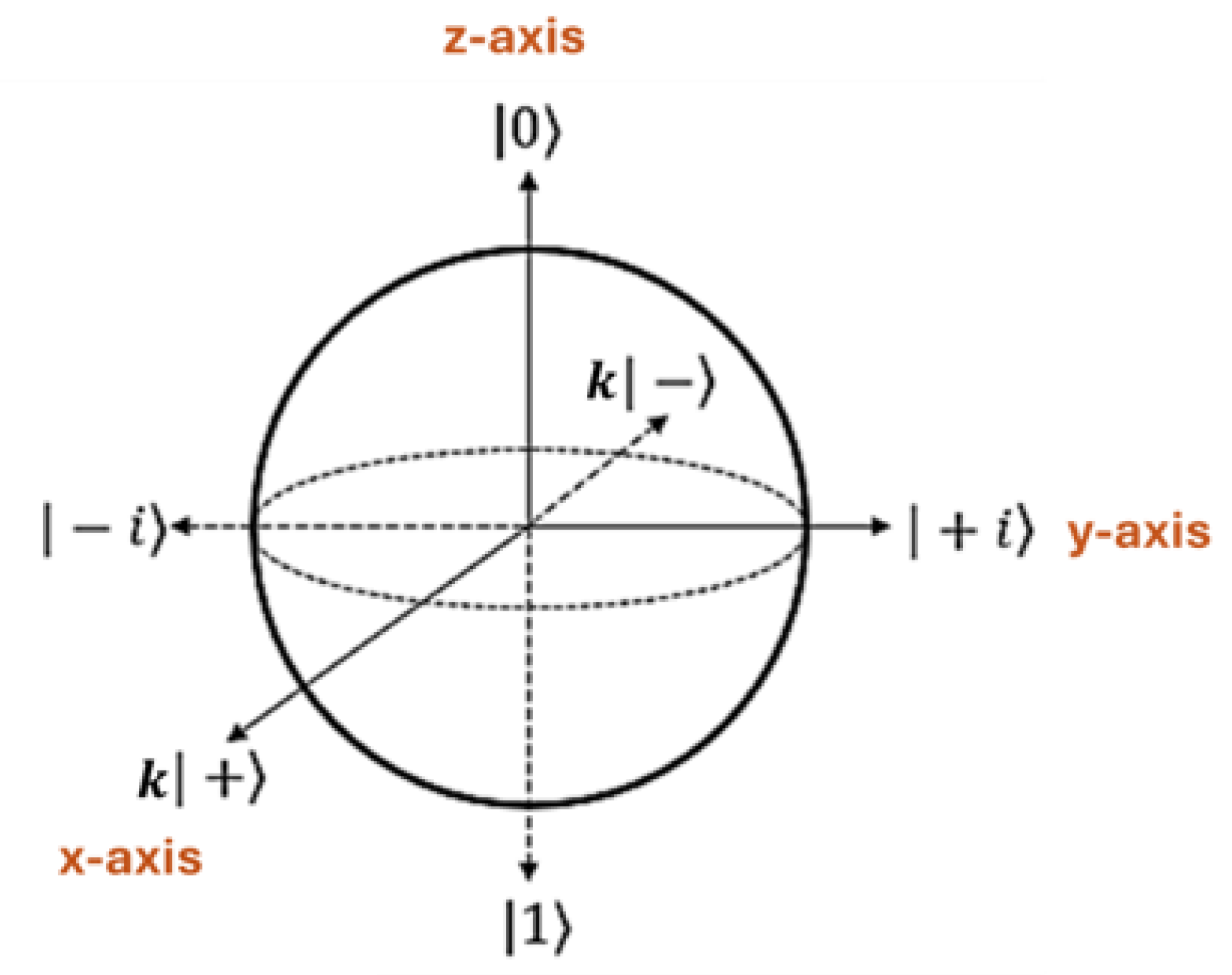

3.4. The k-Bloch Sphere

Similar to

Table 2, the eigenstates and eigenvalues of the Pauli matrices of the 211–Framework can be used to construct a unique Bloch sphere for the mathematical framework from which qubits can be adequately described. The eigenstates and eigenvalues for the Pauli matrices of the 211-Framework and how they used to construct a novel k-Bloch Sphere for the framework is given in

Table 15.

The visual representation of this Bloch sphere is shown in

Figure 2.

The only major change to the original block sphere is the factor of that appears in the x-axis. This is a direct consequence of the fact that the eigenvalues of the matrix are multiplied by a factor of . This factor of means that the -Bloch Sphere has a new dimension that does not exist with the original Bloch sphere used in current quantum computing.

An example of where such a difference is important is in the use of density matrices. In quantum computing and quantum mechanics, a density matrix (or density operator) is a matrix used in calculating the probabilities of the outcomes of measurements performed on physical systems. Density matrices are crucial tools in quantum computing that deal with mixed states used to derive quantum information.

A qubit's density matrix

can be represented on the Bloch sphere using a formula that connects it to a real-valued vector

, called the Bloch vector. The density matrix is expressed as a linear combination of the identity matrix and the k-Pauli matrices, with coefficients from the Bloch vector. This is shown in Equation (18).

Equation (18) generates a k-Bloch sphere, where qubits can be used to explore dimensions that are not used in current quantum computing. This gives the potential to model exotic quantum systems such as extended quantum gravity structures.

3.5. Universal Gate Set and the Solovay-Kitaev Theorem

Section 3.1 to Section 3.3 shows that the k-numbers behave in a consistent way; that is, the rules and operations defined for them behave in a predictable and logical manner, adhering to the established properties of arithmetic and quantum computing.

It is now necessary to show that a “universal” gate sets exist for the 211-Framework. In classical computing, any logic circuit can be built using a small set of basic logic gates (combination of AND, OR, and NOT gates). This set of logic gates is considered "universal" because any known classical logic circuit can be constructed from these gates. In a similar manner, in quantum computing, for a mathematical framework to be considered fully capable of providing the necessary backbone to build a quantum computing framework it is necessary to show that a set of universal quantum gates exist from which a quantum logical circuits can be built. Since quantum operations are represented by unitary matrices (which in turn represent quantum gates), a universal gate set means that any unitary matrix can approximated by combining gates from within that universal gate set. Therefore, we formally define the universal gate set as:

To show that a set of gates form a universal gate set, it is necessary to show that this set of gates can be used to generate a dense subgroup of SU(2). Here “dense subgroup” means that by combining gates from the finite universal gate set it is possible to get arbitrarily close to any possible single-qubit unitary operation. Note that a “single-qubit unitary operation” is another way of saying a quantum gate.

As a reminder, SU(2) means “special unitary matrices” that represent single-qubit unitary operations. Special means that the determinant of these matrices is 1. And unitary means that the conjugate transpose of the matrix is the same as its inverse.

In the 111–Framework (regular quantum computing that uses complex numbers) there are several types of universal gate sets, the simplest of which is the Hadamard gate (H) and the T-gate (T)

(and its inverses, which are implicitly included as a sequence of gates can always be inverted). These gates are defined as:

The Hadamard gate creates superpositions and rotates qubits in the Bloch sphere. For example, it maps to and to . The T-gate is a phase shift gate.

The analogues of these gates were used to represent the universal gate set for in the 211–Framework. For the mathematical 211–Framework the following universal gate set is defined:

where:

The universal gate set consist of the Hadamard gate, the

–gate. It is of course necessary to prove that

forms a universal gate set. The proof is provided in

Appendix A5. Another important concept (mentioned in

Appendix A5) in defining the universal gate set is the Solovay-Kitaev theorem which is a fundamental result in quantum computation that addresses the problem of approximating arbitrary unitary operations (quantum gates) using a finite set of universal gates [

33]. It states that: “

if a set of single-qubit gates can generate a dense subgroup of SU(2), then any desired single-qubit gate can be approximated to an arbitrary precision using a sequence of gates from this finite set whose length scales poly-nominally in ” [

34]. More precisely, the length of the sequence is

for some constant

. The proof also provides an efficient classical algorithm to find such a sequence.

The theorem is one of the cornerstones of quantum computing demonstration that while the space of quantum operations is continuous, we can efficiently approximate any operation using discrete finite set of basic building blocks, which is essential for building scalable and practical quantum computers [

35]. Demonstrating that a universal gate set forms a “dense subset” (as was done in

Appendix A5) is sufficient to show that the gate set adheres to the Solovay-Kitaev theorem [

36]. This in turn is enough to demonstrate that the mathematical 211-Framework is enough to provide a fully consistent and capable backbone upon which to build quantum computing [

37].

3.6. Demonstrating the Utility of the 211-Framework

To demonstrate the utility of the 211-Framework imagine there a quantum algorithm that, at a certain step, needs to apply a Z-rotation (phase shift) to a qubit. The angle of this Z-rotation is determined by the "distance" or "overlap" between two previously measured classical values, A and B.

Suppose the angle is defined as: , where C is some non-zero constant (e.g., ).

Under the 211-Framework the quantum gate: is to be applied.

Suppose, at an earlier stage of the algorithm, some classical measurements or computations were performed and yielded:

Now, attempting to calculate the angle

for the Z-rotation gives:

This expression results in a division by zero that can be easily handled by the underlying number set upon which the 211-Framework is based.

In the classical quantum computing setting (that is under the 111-Framework where complex numbers are used) the calculation of results in an undefined value, the classical control system that is supposed to prepare and apply the quantum gate cannot determine the parameters for the gate. The program would crash or throw an error at Step 2, long before any quantum hardware or simulator attempts to apply the gate.

However, under the 211-Framework, the classical control system would simply pass the value to the quantum system to be handles by the new gate. This is shown below:

This rotation is fully achievable under the 211-Framework. This matrix is perfectly well-defined. The classical control system passes these parameters to the quantum hardware (or simulator), and the quantum

gate is successfully applied to the target qubit. For example, if the qubit is in the state

:

This is a valid quantum state that can easily be represented on the k-Bloch sphere. Proof of this is given in

Appendix A6. This example demonstrates that when the classical calculations that determine quantum gate parameters are well-defined, the quantum logic gates operate perfectly normally as unitary transformations.

4. A Note on the 121-Framework and the 112-Framework

For the sake of brevity, a foundation of only one (211-Framework) out of the four mathematical frameworks was established and the utility of the framework demonstrated. The 111-Framework (a complex number mathematical framework) for quantum computing is already well established. The other two frameworks, the 121-Framework and the 112-Framework can be given the same treatment as the 211-Framework from this paper. However, this will not be done here. It suffices to say that these other frameworks are equally good at handling division by zero within quantum computing. A look at these other frameworks will be done in subsequent research papers.

Discussion

Quantum computing, rooted in the mathematical framework of linear algebra over complex numbers, using Hilbert spaces to represent quantum states (qubits) and unitary operations (quantum gates) to manipulate them. Phenomenon like superposition, entanglement, and interference are all precisely described within this mathematical framework. If a different mathematical framework were to be used to create quantum computing, it would be a profound shift providing far-reaching implications.

This research provides the impetus for this shift. 3 mathematical frameworks were developed that can be used for quantum computing. These frameworks are 211-Framework, 121-Framework and 112-Framework. What makes these frameworks fundamentally different from the original 111-Framework (that is, mathematical framework of linear algebra over complex numbers) is that They all incorporate division by zero within their structure in slightly different ways. The frameworks themselves are distinct by the number sets and Pauli matrices that underlie their structure.

Qubits as we know them (superpositions of 0 and 1) are a direct consequence of the current mathematical framework. These new frameworks have the potential to lead to entirely different "quantum bits" with unique properties. It has already been demonstrated in this paper that the fireworks themselves have led to new types of quantum logic gates that operate differently. This means that these new mathematical frameworks have the potential to create entirely new types of quantum algorithms with different strengths and weaknesses to those that already exist. The new framework might unlock computational capabilities that are not possible or even conceivable within the current quantum computing paradigm. Depending on the framework, it might become significantly easier to build robust and scalable quantum computers, or it might introduce even greater engineering challenges.

Other impacts that can be realized from these new frameworks include: (1) entirely new quantum correction algorithms providing a more natural way to tackle optimization problems, machine learning, or complex simulations; (2) new quantum programming computational models; (3) introduce more potent attacks on current cryptographic systems, or conversely, lead to fundamentally new and stronger forms of quantum-resistant cryptography; (4) allow for even more accurate and efficient simulations; and, (5) open up new paradigms for quantum machine learning and AI, potentially leading to breakthroughs in areas like pattern recognition, data analysis, and intelligent systems.

All these possibilities can be explored for each of the new frameworks developed in this paper. In essence, a shift to a different mathematical framework for quantum computing would be a paradigm shift on That has the potential for large scale advancement.

Conclusion

Quantum computing, rooted in the mathematical framework of linear algebra over complex numbers, using Hilbert spaces to represent quantum states (qubits) and unitary operations (quantum gates) to manipulate them. Phenomenon like superposition, entanglement, and interference are all precisely described within this mathematical framework. However, quantum computing is limited by its inability to divide by zero. This curtails the ability of quantum computers to handle singularities and infinities in simulations and solve ill-posed problems. This paper aimed to use semi structured complex numbers to define three distinct number sets that can enable division by zero and simultaneously form four core foundational yet distinct mathematical frameworks for building quantum computers. In the process of doing these three new number sets that are subsets of semi-structured complex numbers were defined; (2) a Generalized Pauli Matrix Sets consisting of 6 Pauli matrices was developed; (3) from these four mathematical frameworks were created and the consistency and full capability of one of the frameworks (221-Framework) was demonstrated. It is expected that these different mathematical frameworks would have a profound shift and provide far-reaching implications for quantum computing especially in the areas of algorithm creation, cryptography and the paradigms for quantum machine learning and AI.

Appendix A1. Major Results from Past Paper on Semi-Structured Complex Numbers

Table A1.

Major results from paper [

38] for semi-structured complex numbers.

Table A1.

Major results from paper [

38] for semi-structured complex numbers.

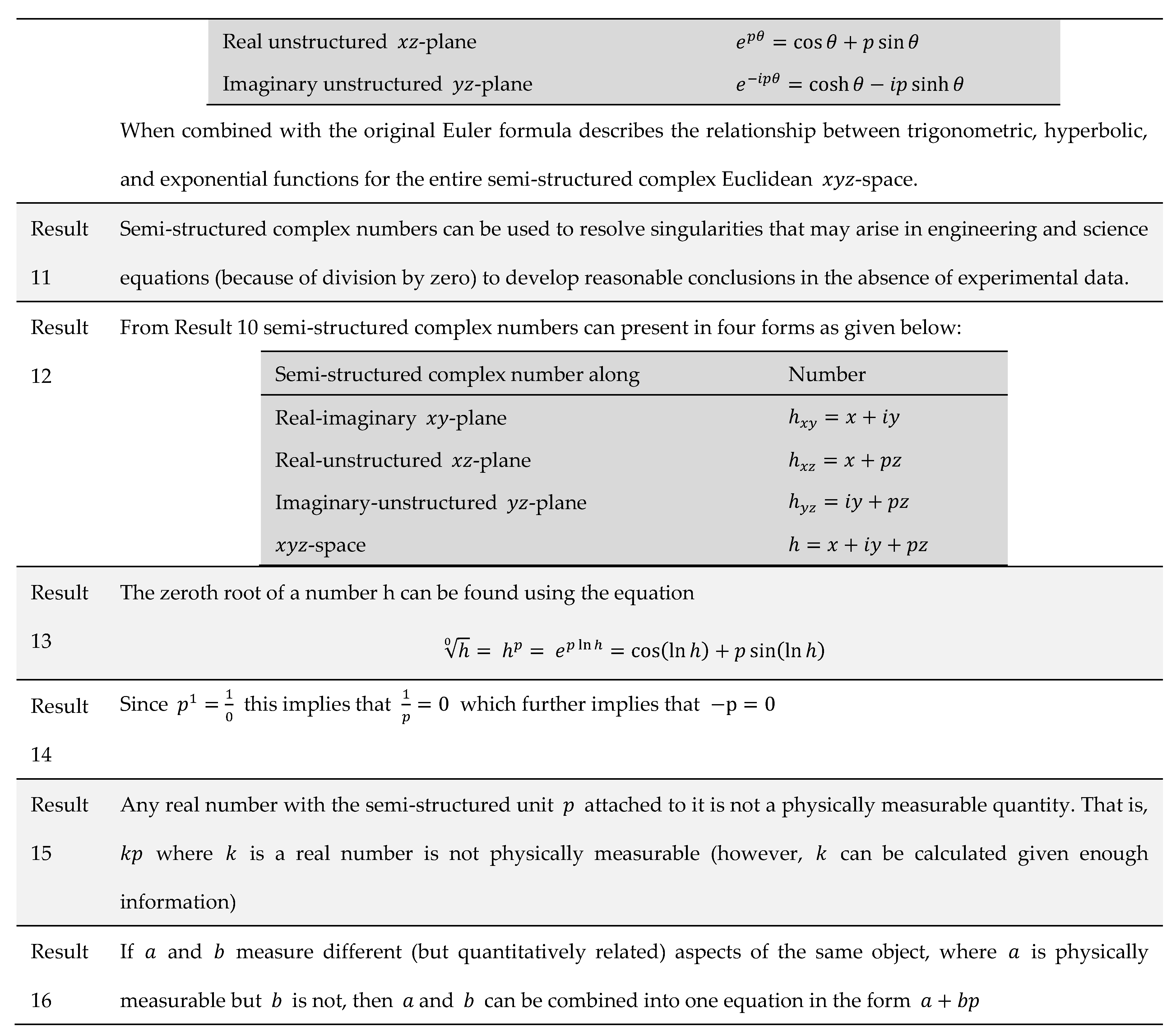

Appendix A1. Proof that -Numbers, -Numbers, -Numbers Obey the Field Axioms

This section is meant to provide proof that the three subsets (-numbers, -numbers, -numbers) obey the 11 field axioms. In summary the 11 field axioms can be divided into two distinct sets of axioms; the first six axioms address the operation of addition, and the last five axioms address the operation of multiplication.

The proof three subsets (

-numbers,

-numbers,

-numbers) obey the first six axioms is the same and is presented in

Table A2. For the last five axioms the

-numbers and

-numbers have the same proof structure and the

-numbers have a different proof structure. These proof structures are presented in

Table A3.

Definitions:

To understand these proofs, first, the following definitions are provided:

In the case of -numbers , these can be written as , where . This is often represented as , where is the imaginary unit.

In the case of -numbers , these can be written as , where . This is often represented as , where is the unstructured unit.

From these definitions’ equality, addition, and multiplication can be defined as follows:

| Equality: |

|

| Addition: |

|

| Multiplication: |

|

Additionally,

In the case of -numbers, these can be written as , where . This is often represented as , where is the imaginary unstructured unit.

From this definition equality, addition, and multiplication can be defined as follows:

| Equality: |

|

| Addition: |

|

| Multiplication: |

|

Given these definitions the proofs as follows:

Table A2.

Proof that all three number sets obey the first six field axioms.

Table A2.

Proof that all three number sets obey the first six field axioms.

Table A3.

Proof that the three number sets i-numbers obey the last five field axioms.

Table A3.

Proof that the three number sets i-numbers obey the last five field axioms.

Appendix A2. Sample Proof of the Hermitian and Unitary Nature of Matrix Transformation and Matrix Transformation

It would be a bit cumbersome to attempt to do a proof of the Hermitian and unitary nature of all eight matrix transformations in

Table 8. Therefore, two matrix transformations were selected at random and the proof of these transformations was given here as a sample of how to prove the Hermitian and unitary nature of the matrix transformations presented in

Table 8. The two transformations selected were matrix transformation

and matrix transformation

-

1.

Sample Proof of the Hermitian and Unitary nature of matrix transformation

Hermitian Property:

The transpose of this matrix is given below:

The complex conjugate of the transpose is given as:

Clearly Equation (20) and (22) are equivalent. Thus, the Hermitian property is proven.

Additionally, if the matrices in Equation (20) and (22) are multiplied:

Therefore the unitary property has been proven.

Therefore the matrix is a Hermitian unitary matrix.

-

2.

Sample Proof of the Hermitian and Unitary nature of matrix transformation

Additionally, consider the matrix:

Hermitian Property:

The transpose of this matrix is given below:

The complex conjugate of the transpose is given as:

Clearly Equation (20) and (22) are equivalent. Thus the Hermitian property is proven.

Additionally, if the matrices in Equation (20) and (22) are multiplied:

Therefore, the unitary property has been proven.

Proof for the other six transformation matrices in

Table 8 follow the same basic steps.

Appendix A3. Commutator Identities Under the 211-Framework

Consider the commutation relation . This relation can be applied to pairs of matrices from the set .

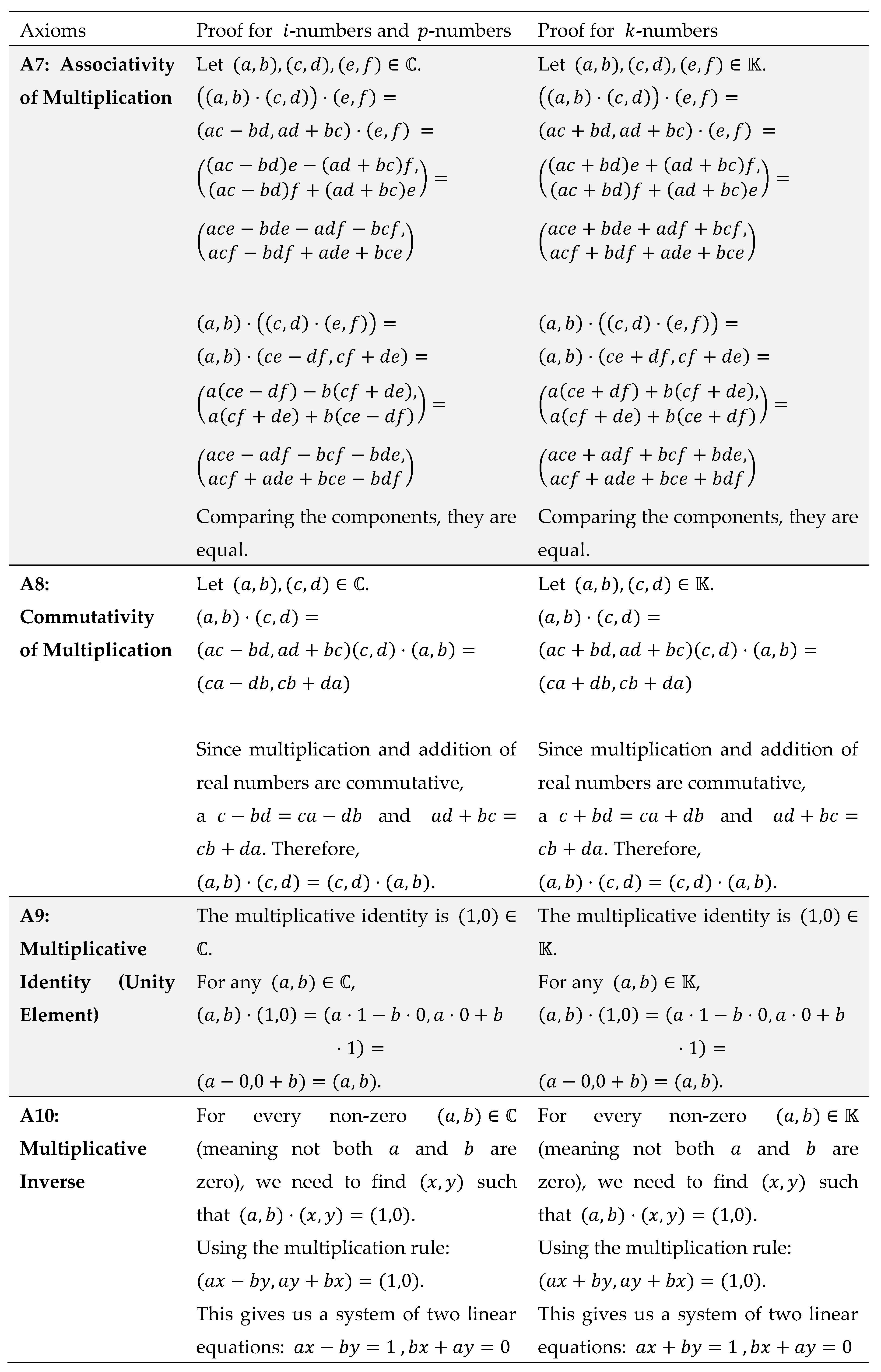

Appendix A4. Proving the Universality of the Set Under the 211-Framework

To prove that the set we use the Solovay Kitaev Theorem. The theorem states that: “if a set of single-qubit gates can generate a dense subgroup of SU(2), then any desired single-qubit gate can be approximated to an arbitrary precision using a sequence of gates from this finite set”. This finite set of gates is then called the universal set. The key to proving that forms a universal set is to simply prove that they form a “dense subgroup” of SU(2).

The key principle for denseness is that A finite set of rotations on a sphere generates a dense set of rotations if and only if the group they generate contains rotations about two axes that are not parallel.

We simply need to prove that the set can generate rotations about two non-parallel axes.

- 1.

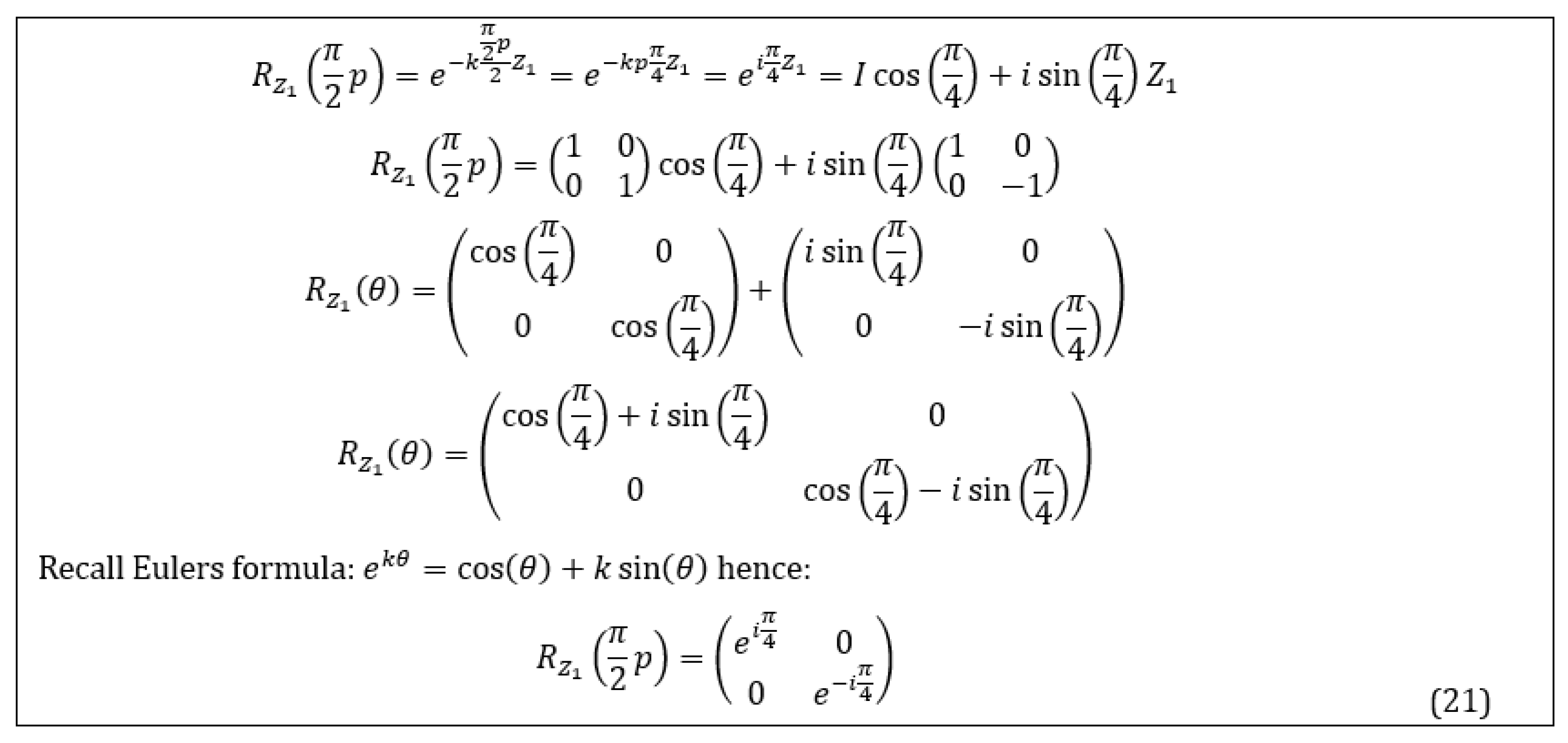

The T-gate is defined as:

- 2.

-

A rotation around the Z-axis by an angle

is given by:

Recall Eulers formula: hence:

- 3.

Comparing T-gate with and the concept of global phase equivalence

It is necessary to find an angle such that T is equivalent to Recall in quantum mechanics, two gates and are considered equivalent if they differ only by a global phase factor, i.e., for some real . This is because a global phase does not affect the physical probabilities of measurement outcomes. Hence, we need to solve the equation

This shows that the T-gate is equivalent to a Z-axis rotation by an angle of , up to a global phase of . This means the T-gate itself is fundamentally a Z-axis rotation.

The Hadamard gate is a "non-axial" rotation. It maps the Pauli axes as follows:

This property is important. If we can perform rotations around the Z-axis (using T), and to "switch" the axes (using H), then we can effectively perform rotations around other axes.

- 1.

The T-gate provides rotations around the Z-axis.

- 2.

The Hadamard gate allows us to transform rotations around the Z-axis into rotations around the X-axis (and vice-versa, and Y-axis rotations into negative Y-axis rotations).

- 3.

Having rotations around two non-parallel axes (e.g., X and Z) with "incommensurate" angles (angles that are irrational multiples of ) is sufficient to densely cover the group. The angle from the T-gate provides this irrationality, as is not a rational multiple of .

Therefore, the set (and its inverses, which are implicitly included as a sequence of gates can always be inverted) is a universal gate set for because the group it generates is dense in.

As similar proof can be used to find the Universal Gate Sets for each quantum computing mathematical framework. A summary of the results of such proofs is provided in Table A4.

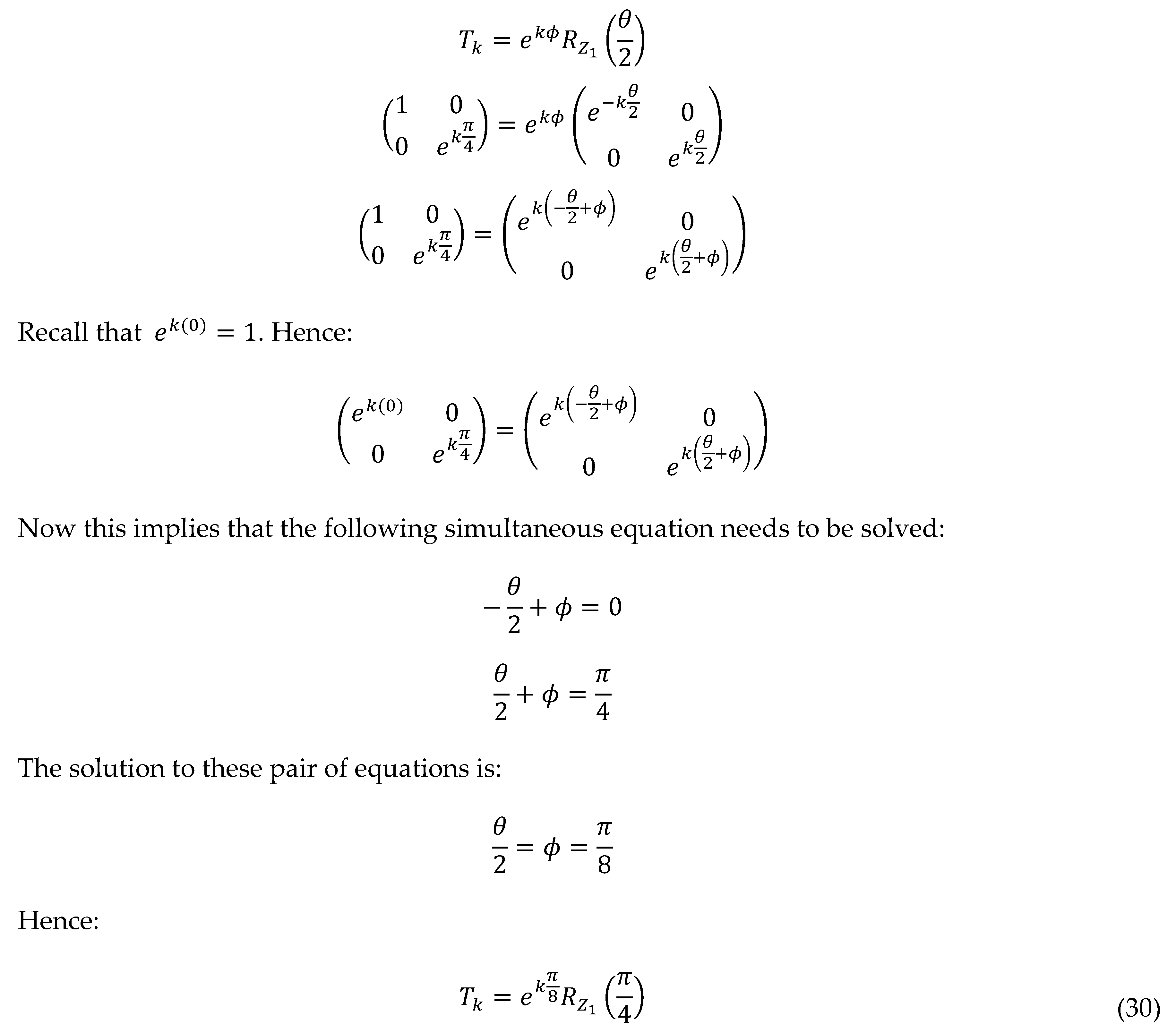

Appendix A5. Representing a Rotation on the k-Bloch Sphere

Suppose the rotation

needs to be represented on the k-Bloch sphere. This can be done as follows:

Removing the global phase

(recall only relative phase between the qubits are important) gives:

To map this on to the Block Sphere we need to use the equation:

. That is:

Comparing the left- and right-hand side of the above equation yields the following:

The spherical coordinates that map the above results to the k-Bloch sphere are:

Hence the vector on the Bloch sphere becomes

. A visual of the results are given in

Figure A1.

Figure A1.

Bloch sphere vector (red arrow) describing the division by zero rotation in the 211-Framework.

Figure A1.

Bloch sphere vector (red arrow) describing the division by zero rotation in the 211-Framework.

References

- Rao, K.J., Rajasekhar, Y., Vijayalakshmi Y. and Malathi, N.V., "Mathematical foundations and algorithms for quantum computing," International Journal of Statistics and Applied Mathematics, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 97-102, 2025.

- Naik L.S., "The Role of Linear Algebra in Quantum Computing," IJRAR, vol. 8, no. 1, 2021.

- Hrdina, J., Hildenbrand, D., Návrat, A. et al., "Quantum Register Algebra: the mathematical language for quantum computing," Quantum Inf Process, 2023, vol. 22, pp. [CrossRef]

- Tafadzwa C.E., "Division by zero in real and complex number arithmetic and some of its implications," African Journal of Mathematics and Computer Science Research, vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 14-25, 2022.

- Mohan, V. , "Black hole singularities from holographic complexity," Journal of High Energy Physics , 2025, vol. 2025, p. [CrossRef]

- Frellesvig, H., Morales, R., Pögel, S., Weinzierl, S., & Wilhelm, M., "Calabi-Yau Feynman integrals in gravity ε-factorized form for apparent singularities," Journal of High Energy Physics, 2025, vol. 2025, p. [CrossRef]

- Towne B.P., "Quantum Collapse of Indeterminate States: An Alternative Framework for Division by Zero," Yiwu Industrial Commercial College, Yiwu, China∗, 3 October 2024. [Online]. Available: https://vixra.org/pdf/2410.0028v1.pdf. [Accessed 22 August 2025].

- Di Meglio, A., Jansen, K., Tavernelli, I., Alexandrou, C., Arunachalam, S., Bauer, C. W., Zhang, J. et al., " (2024). Quantum computing for high-energy physics: State of the art and challenges," Prx quantum, vol. 5, no. 3, p. 037001, 2024.

- Grimm, T.W., van Vliet, M. , "On the complexity of quantum field theory," Journal of High Energy Physics, 2025, vol. 2025, p. [CrossRef]

- Meyenburg, T., "A Novel Algebraic Framework for Division by Zero Using Boolean Operations," International Journal of Mathematics Trends and Technology-IJMTT, vol. 71, 2025.

- Kulkarni, S. P., & Bethel, E. W., "From Bits to Qubits: Challenges in Classical-Quantum Integration," IEEE 31st International Conference on High Performance Computing, Data, and Analytics (HiPC), pp. 166-176.

- Bharos, N., Markovich, L., & Borregaard, J., "Efficient high-dimensional entangled state analyzer with linear optics.," Quantum, vol. 9, p. 1711.

- Bärlin, J., "Formation of singularities in solutions to nonlinear hyperbolic systems with general sources.," Nonlinear Analysis: Real World Applications, vol. 73, p. 103901, 2023.

- An, D., Liu, JP., Wang, D. et al. , "Quantum Differential Equation Solvers: Limitations and Fast-Forwarding," Communications in Mathematical Physics , 2025, vol. 406, pp. [CrossRef]

- Shvartsman, I., "Linear Programming Approach to Optimal Control Problems with Unbounded State Constraint," Journal of Optimization Theory and Applications, vol. 204, no. 2, p. 18, 2025.

- Cai, S., Li, X., "Optimality and scalarization of robust approximate solutions for semi-infinite vector equilibrium problems," Journal of Inequalities and Applications, 2025, vol. 67, no. 2025, pp. [CrossRef]

- P. Jean Paul and S. Wahid, "Applications of Semi-Structured Complex Numbers in Science and Engineering.," Preprints. , 2023, p. [CrossRef]

- Peter, J. P., & Shanaz, W., "Reformulating and Strengthening the Theoretical Foundations of Semi-structured Complex Numbers," World Scientific News, vol. 169, pp. 152-182, 2022.

- Paul, P. J., & Wahid, S., "Unstructured and Semi-structured Complex Numbers: A Solution to Division by Zero," Pure and Applied Mathematics Journal, vol. 10, no. 2, p. 49, 2021.

- Jean-Paul, P., & Wahid, S. , "Applications of Semi-Structured Complex Numbers in Science and Engineering," ResearchGate, 2023.

- Koska, O., Baboulin, M., & Gazda, A., "A tree-approach Pauli decomposition algorithm with application to quantum computing," ISC High Performance 2024 Research Paper Proceedings (39th International Conference) , pp. 1-11, 2024.

- Vidal Romero, S., & Santos-Suárez, J., "PauliComposer: compute tensor products of Pauli matrices efficiently.," Quantum Information Processing, vol. 22, no. 12, p. 449, 2023.

- Beyer, M., & Paul, W., "Stern–Gerlach, EPRB and Bell Inequalities: An Analysis Using the Quantum Hamilton Equations of Stochastic Mechanics," Foundations of Physics, vol. 54, no. 2, p. 20, 2024.

- Tah, R., "Calculating the Pauli Matrix equivalent for Spin-1 Particles and further implementing it to calculate the Unitary Operators of the Harmonic Oscillator involving a Spin-1 System.," hal-02909703f, 2020.

- Liebert, J., Lemke, Y., Altunbulak, M., Maciazek, T., Ochsenfeld, C., & Schilling, C., "Toolbox of spin-adapted generalized Pauli constraints," Physical Review Research, vol. 7, no. 2, p. 023247, 2025.

- Sirengo C.W., Marani V., Matuya J., "Mathematical Properties and Characteristics of Pauli Unitary Operators in Quantum Information Theory," IRE Journals, vol. 8, no. 2, 2024.

- van Melkebeek D., "Lecture 6: Single-Qubit and Two-Party Systems," 2 October 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FyYfDWD8HhM. [Accessed 22 August 2025].

- Smith, I. D., Cautrès, M., Stephen, D. T., & Poulsen Nautrup, H., "Optimally Generating su (2 N) Using Pauli Strings," Physical Review Letters, vol. 134, no. 20, p. 200601, 2025.

- Wong, H.Y., "Bloch Sphere, Quantum Gates, and Pauli Matrices," in In: Quantum Computing Architecture and Hardware for Engineers, Springer, Cham, 2025, pp. [CrossRef]

- "Introduction to Quantum Information Science – The Bloch Sphere," [Online]. Available: https://qubit.guide/2.10-the-bloch-sphere. [Accessed 22 August 2025].

- "NE 112 Linear algebra for nanotechnology engineering," University of Waterloo, [Online]. Available: https://ece.uwaterloo.ca/~ne112/Lecture_materials/pdfs/1.6.1%20Field%20axioms.pdf. [Accessed 22 August 2025].

- Mathematics Stack Exchange, "Axioms of Field," Stack Exchange, [Online]. Available: https://math.stackexchange.com/questions/4898251/axioms-of-field. [Accessed 22 August 2025].

- Rossi Z. M. , "A Solovay-Kitaev theorem for quantum signal processing," Cornell University, 8 May 2025. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.05468. [Accessed 22 August 2025].

- De Silva K., Mahasinghe A. & Gunasekara P., "Some remarks on the Solovay–Kitaev approximations in a C*–algebra setting," Palestine Journal of Mathematics, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 25-29, 2023.

- "Universal set of quantum gates," ICTP-SAIFR, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.ictp-saifr.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/ICTP_SAIFR_D1-L2.pdf. [Accessed 22 August 2025].

- "Solovay–Kitaev Theorem," Wikipedia Contributors, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solovay%E2%80%93Kitaev_theorem. [Accessed 22 August 2025].

- Long, J., Zhong, J., & Meng, L. , "The Construction of a Universal Quantum Gate Set for the SU(2)k Anyon Models via GA-Enhanced SK Algorithm.," arXiv., 2025.

- P. Jean-Paul and S. Wahid, "Reformulating and Strengthening the Theoretical Foundations of Semi-structured Complex Numbers," International Journal of Applied Physics and Mathematics, vol. 12, pp. 34-58, 2022.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).