Submitted:

13 September 2025

Posted:

16 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Background

Rationale

Methods

Eligibility Criteria

Information Sources

Search Strategy

Selection Process

Data Collection Process

Data Items

Study Risk of Bias Assessment

Synthesis Methods

Results

Thematic Analysis

Commissioning Stance and Scope

Legal Framework and Definitions

Ethical, Medico-Legal Risk and Safeguarding

Parentage Transfer, Nationality and Administrative Pathways

Cross-Border Complexity

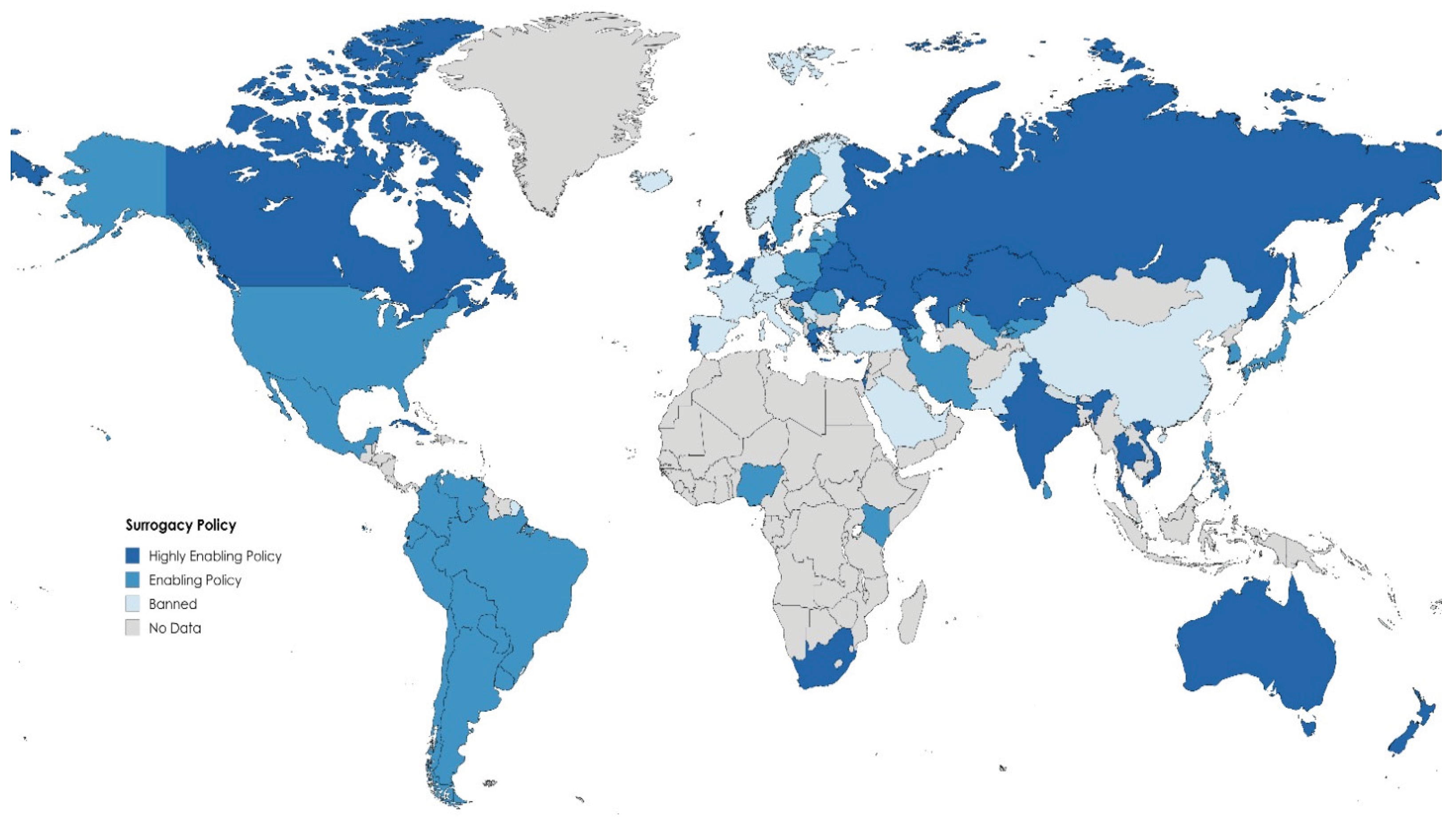

Contextual Analysis

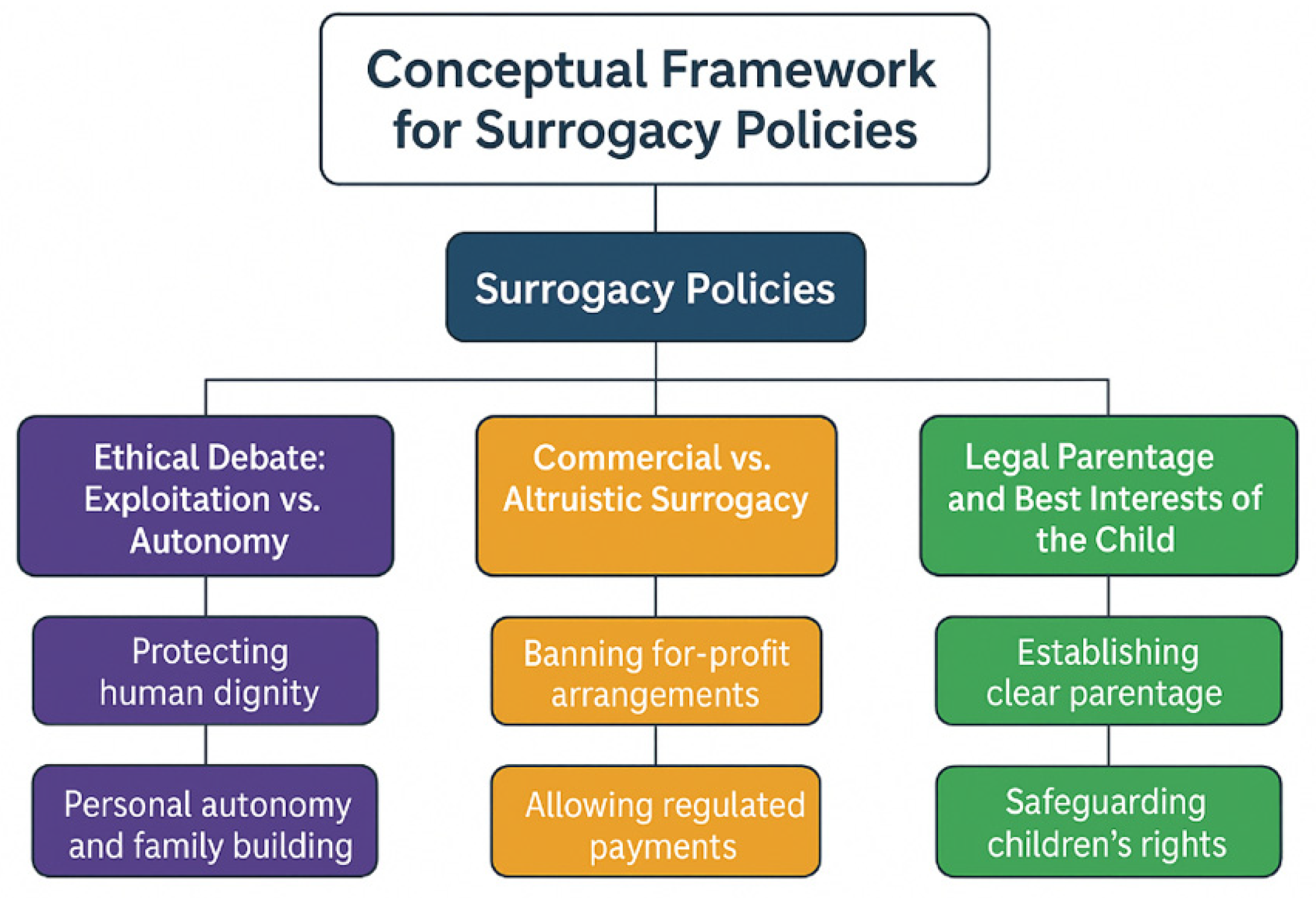

Ethical Debate: Exploitation vs. Autonomy

Commercial vs. Altruistic Surrogacy

Legal Parentage and Best Interests of the Child

Comparative Analysis

Discussion

Women’s Health Implications

Societal Implications

Clinical Implications

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Availability of Data and Material

Code Availability

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethics Approval

Consent to Participate

Consent for Publication

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Horsey K. The future of surrogacy: a review of current global trends and national landscapes. Reproductive BioMedicine Online [Internet]. 2024 May 1 [cited 2025 Sep 6];48(5):103764. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1472648323008635.

- Bromfield NF, Rotabi KS. Global Surrogacy, Exploitation, Human Rights and International Private Law: A Pragmatic Stance and Policy Recommendations. Glob Soc Welf [Internet]. 2014 Sep 1 [cited 2025 Sep 6];1(3):123–35. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Graham ME, Jelin A, Hoon AH, Wilms Floet AM, Levey E, Graham EM. Assisted reproductive technology: Short- and long-term outcomes. Dev Med Child Neurol [Internet]. 2023 Jan [cited 2025 Sep 6];65(1):38–49. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9809323/.

- Haddadi M, Hantoushzadeh S, Hajari P, Pouraie RR, Hadiani MY, Habibi GR, et al. Challenges and Prospects for Surrogacy in Iran as a Pioneer Islamic Country in this Field. Arch Iran Med [Internet]. 2025 Apr 1 [cited 2025 May 13];28(4):252–4. Available from: https://journalaim.com/Article/aim-33920.

- Piersanti V, Consalvo F, Signore F, Del Rio A, Zaami S. Surrogacy and “Procreative Tourism”. What Does the Future Hold from the Ethical and Legal Perspectives? Medicina (Kaunas). 2021 Jan 8;57(1):47. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Xian X, Du L. Perspectives on Surrogacy in Chinese Social Media: A Content Analysis of Microblogs on Weibo. The Yale journal of biology and medicine. 2022;95(3):305–16.

- Jones B, Saso S, Bracewell-Milnes T, Thum M, Nicopoullos J, Diaz-Garcia C, et al. Human Uterine transplantation: a Review of Outcomes from the First 45 Cases. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2019;126(11):1310–9. [CrossRef]

- Testa G, McKenna GJ, Wall A, Bayer J, Gregg AR, Warren AM, et al. Uterus Transplant in Women With Absolute Uterine-Factor Infertility. JAMA. 2024;332(10):817–817. [CrossRef]

- Patel NH, Jadeja YD, Bhadarka HK, Patel MN, Patel NH, Sodagar NR. Insight into Different Aspects of Surrogacy Practices. J Hum Reprod Sci [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2025 Sep 6];11(3):212–8. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6262674/. [CrossRef]

- Brandão P, Garrido N. Commercial Surrogacy: An Overview. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet [Internet]. 2022 Dec 29 [cited 2025 Sep 6];44(12):1141–58. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9800153/.

- Attawet J, Alsharaydeh E, Brady M. Commercial surrogacy: Landscapes of empowerment or oppression explored through integrative review. Health Care Women Int. 2024 Jan 22;1–19. [CrossRef]

- Banaras, F. Cross-Border Surrogacy: Legal and Ethical Challenges in Global Assisted Reproduction. 2023.

- Surrogacy in the USA · Growing Families [Internet]. Growing Families. [cited 2025 Sep 6]. Available from: https://www.growingfamilies.org/surrogacy-in-the-usa/.

- Marinelli S, Negro F, Varone MC, Paola LD, Napoletano G, Lopez A, et al. The legally charged issue of cross-border surrogacy: Current regulatory challenges and future prospects. European Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Reproductive Biology [Internet]. 2024 Sep 1 [cited 2025 Sep 6];300:41–8. Available from: https://www.ejog.org/article/S0301-2115(24)00343-9/fulltext.

- Gunnarsson Payne J, Korolczuk E, Mezinska S. Surrogacy relationships: a critical interpretative review. Ups J Med Sci [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 6];125(2):183–91. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7721025/.

- Surrogacy: The legal situation in the EU | Think Tank | European Parliament [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 6]. Available from: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_BRI(2025)769508.

- GOV.UK [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 6]. The surrogacy pathway: surrogacy and the legal process for intended parents and surrogates in England and Wales. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/having-a-child-through-surrogacy/the-surrogacy-pathway-surrogacy-and-the-legal-process-for-intended-parents-and-surrogates-in-england-and-wales.

- Aramesh K. Ethical Assessment of Monetary Relationship in Surrogacy. Journal of Reproduction & Infertility [Internet]. 2008 Apr 1 [cited 2025 Sep 6];9(1):36–42. Available from: https://www.jri.ir/article/304.

- East Midlands Affiliated Commissioning Committee (EMACC). Surrogacy Involving Assisted Conception Policy [Internet]. Derby and Derbyshire CCG: East Midlands Affiliated Commissioning Committee (EMACC); 2025 Apr. Available from: https://www.derbyshiremedicinesmanagement.nhs.uk/assets/Clinical-Policies/Clinical_Policies/PLCV/gynae_and_fertility/Surrogacy_Involving_Assisted_Conception.pdf.

- Gloucestershire Integrated Care Board (ICB). Surrogacy: Interventions not normally funded (INNF) [Internet]. Gloucestershire, UK: Gloucestershire ICB; 2025 Oct. Available from: https://www.nhsglos.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Surrogacy.pdf.

- Participation E. Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 2008 [Internet]. Statute Law Database; [cited 2025 Sep 3]. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2008/22/contents.

- Participation E. Surrogacy Arrangements Act 1985 [Internet]. Statute Law Database; [cited 2025 Sep 6]. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1985/49.

- GOV.UK [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 6]. Surrogacy: caseworker guidance (accessible). Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/surrogacy-caseworker-guidance/surrogacy-caseworker-guidance-accessible.

- GOV.UK [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 6]. Children born through surrogacy. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/getting-a-uk-passport-if-your-child-was-born-through-surrogacy/children-born-through-surrogacy.

- Italy bans citizens from seeking surrogacy abroad | The BMJ [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 6]. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/387/bmj.q2316.

- Book (eISB) electronic IS. electronic Irish Statute Book (eISB) [Internet]. Office of the Attorney General; [cited 2025 Sep 6]. Available from: https://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2024/act/18/enacted/en/html.

- Everingham S. Major Change to Greek Surrogacy Laws: What It Means for International Intended Parents · Growing Families [Internet]. Growing Families. 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 6]. Available from: https://www.growingfamilies.org/blog/major-change-to-greek-surrogacy-laws-what-it-means-for-international-intended-parents/.

- admin. Surrogacy in Cyprus | Best Surrogacy Center in USA & Overseas [Internet]. Surrogacy4all - IVF Surrogacy, Surrogate Mother and Egg Donation Center in New York. [cited 2025 Sep 6]. Available from: https://www.surrogacy4all.com/cyprus-surrogacy/.

- Raposo VL. The new Portuguese law on surrogacy - The story of how a promising law does not really regulate surrogacy arrangements. JBRA Assist Reprod [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2025 Sep 6];21(3):230–9. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5574646/.

- Chen J. Intimate strangers: commercial surrogacy in Russia and Ukraine and the making of truth. Sex Reprod Health Matters [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 6];32(1):2328474. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC11005867/.

- Haddadi M, Hedayati F, Hantoushzadeh S. Parallel paths: abortion access restrictions in the USA and Iran. Contracept Reprod Med [Internet]. 2025 Jul 25 [cited 2025 Sep 4];10(1):44. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40834-025-00382-3. [CrossRef]

- The New York State Child-Parent Security Act: Gestational Surrogacy [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 6]. Available from: https://www.health.ny.gov/community/pregnancy/surrogacy/.

- Branch LS. Consolidated federal laws of Canada, Assisted Human Reproduction Act [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Sep 6]. Available from: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/a-13.4/.

- International Child Custody Lawyer in Brazil – Dr. Mauricio Ejchel [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Sep 6]. Available from: https://internationallawyerbrazil.com/surrogacy-in-brazil/.

- Surrogacy in Mexico · Growing Families [Internet]. Growing Families. 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 6]. Available from: https://www.growingfamilies.org/surrogacy-in-mexico/.

- Mahtani N. EL PAÍS English. 2024 [cited 2025 Sep 6]. The limbo of surrogacy in Colombia: ‘What is not forbidden is permitted.’ Available from: https://english.elpais.com/health/2024-02-26/the-limbo-of-surrogacy-in-colombia-what-is-not-forbidden-is-permitted.html.

- Turconi, PL. Assisted Regulation: Argentine Courts Address Regulatory Gaps on Surrogacy. Health Hum Rights. 2023 Dec;25(2):15–28.

- Kashyap S, Tripathi P. The Surrogacy (Regulation) Act, 2021: A Critique. Asian Bioeth Rev. 2023 Jan;15(1):5–18. [CrossRef]

- Atreya A, Kanchan T. The ethically challenging trade of forced surrogacy in Nepal. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018 Feb;140(2):254–5. [CrossRef]

- Attawet, J. Reconsidering Surrogacy Legislation in Thailand. Med Leg J. 2022 Mar;90(1):45–8. [CrossRef]

- Cambodia releases surrogate mothers who agree to keep children [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 7]. Available from: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-46466888.

- You W, Feng J. Legal regulation of surrogacy parentage determination in China. Front Psychol [Internet]. 2024 Sep 6 [cited 2025 Sep 7];15:1363685. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC11414016/.

- South Korea - Eastern and Western Perspectives on Surrogacy [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 7]. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/eastern-and-western-perspectives-on-surrogacy/south-korea/778B382D9190B8B380198D77BBC18AAD.

- Hibino, Y. Non-commercial surrogacy among close relatives in Vietnam: policy and ethical implications. Hum Fertil (Camb). 2019 Dec;22(4):273–6. [CrossRef]

- Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 7]. Israel: Supreme Court Authorizes Surrogacy Arrangements for Gay Men. Available from: https://www.loc.gov/item/global-legal-monitor/2021-07-29/israel-supreme-court-authorizes-surrogacy-arrangements-for-gay-men/.

- Hibino Y. Ongoing Commercialization of Gestational Surrogacy due to Globalization of the Reproductive Market before and after the Pandemic. Asian Bioeth Rev [Internet]. 2022 Aug 18 [cited 2025 Sep 7];14(4):349–61. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9386202/.

- Children’s Act 38 of 2005 | South African Government [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 7]. Available from: https://www.gov.za/documents/childrens-act.

- UNICEF and CHIP: Briefing note on children’s rights and surrogacy – Child Identity Protection [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 7]. Available from: https://www.child-identity.org/unicef-and-chip-briefing-note-on-childrens-rights-and-surrogacy/.

- Surrogacy - Milliez - 2008 - International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics - Wiley Online Library [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 7]. Available from: https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.04.016.

- Luk J, Petrozza JC. Evaluation of compliance and range of fees among American Society for Reproductive Medicine-listed egg donor and surrogacy agencies. J Reprod Med. 2008 Nov;53(11):847–52.

- White PM. Canada’s Surrogacy Landscape is Changing: Should Canadians Care? Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada [Internet]. 2017 Nov 1 [cited 2025 Sep 7];39(11):1046–8. Available from: https://www.jogc.com/article/S1701-2163(17)30575-3/abstract.

- Ribeiro G, de Menezes JB. Brazil. In: Fenton-Glynn C, Scherpe JM, Espejo-Yaksic N, editors. Surrogacy in Latin America [Internet]. Intersentia; 2023 [cited 2025 Sep 7]. p. 65–82. (Intersentia Studies in Comparative Family Law). Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/surrogacy-in-latin-america/brazil/9386B14ED39762C3F0A6C6E929488D86.

- UNICEF’s Action against Child Trafficking | UNICEF [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 7]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/reports/unicefs-action-against-child-trafficking.

- Surrogacy, Law & Human Rights [Internet]. ADF International. [cited 2025 Sep 7]. Available from: https://adfinternational.org/resources/surrogacy-law-human-rights.

- Mayers L. From Choice to Justice. Health Hum Rights [Internet]. 2024 Dec [cited 2025 Sep 7];26(2):13–24. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC11683579/.

- Full article: Legal parenthood in surrogacy: shifting the focus to the surrogate’s negative intention [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 7]. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09649069.2024.2344935.

- Specialised Services Commissioning Policy: CP38 Specialist Fertility Services [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://whssc.nhs.wales/commissioning/nwjcc-policies/fertility/specialist-fertility-services-commissioning-policy-cp38-april-2025/.

- Pope calls for surrogacy ban | CNN [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 7]. Available from: https://edition.cnn.com/2024/01/08/world/pope-ban-surrogacy.

- Mitra S, Schicktanz S. Failed surrogate conceptions: social and ethical aspects of preconception disruptions during commercial surrogacy in India. Philos Ethics Humanit Med [Internet]. 2016 Sep 19 [cited 2025 Sep 7];11:9. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5075174/.

- Wade K. The regulation of surrogacy: a children’s rights perspective. Child Fam Law Q [Internet]. 2017 Jun 29 [cited 2025 Sep 7];29(2):113–31. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5540169/.

- Surrogacy: legal rights of parents and surrogates: Overview - GOV.UK [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 7]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/legal-rights-when-using-surrogates-and-donors.

- Surrogacy in Australia [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 7]. Available from: https://www.surrogacy.gov.au/.

- Rodriguez-Wallberg KA, Arturo Reyes Palomares, Nilsson H, Öberg S, Lundberg FE. Obstetric and Perinatal Outcomes of Singleton Births Following Single- vs Double-Embryo Transfer in Sweden. JAMA Pediatrics. 2023;177(2):149–149. [CrossRef]

- Davis N. the Guardian. The Guardian; 2024. Surrogates face higher risk of pregnancy complications, study finds. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2024/sep/23/surrogates-face-higher-risk-of-pregnancy-complications-study-finds.

- Davis N. the Guardian. The Guardian; 2025. Surrogates at greater risk of new mental illness than women carrying own babies, study finds. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2025/jul/25/surrogates-gestational-carriers-risk-mental-illness-pregnancy-canada.

- Lamba N, Jadva V, Kadam K, Golombok S. The psychological well-being and prenatal bonding of gestational surrogates. Human Reproduction (Oxford, England). 2018;33(4):646–53. [CrossRef]

- Espejo-Yaksic N, Fenton-Glynn C, Scherpe JM, editors. Surrogacy in Latin America [Internet]. Intersentia; 2023 [cited 2025 Sep 7]. (Intersentia Studies in Comparative Family Law). Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/surrogacy-in-latin-america/8B4B09CDFE6966681B1A2F400A790DFE.

- Holmstrom-Smith A. Free Market Feminism: Re-Reconsidering Surrogacy [Internet]. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network; 2021 [cited 2025 Sep 7]. Available from: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3896014.

- Сomparison of Surrogacy Conditions in Ukraine and Georgia [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 6]. Available from: https://www.mother-surrogate.com/surrogacy-in-georgia-and-ukraine-where-are-the-conditions-better.html.

- Surrogate.com | [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. LGBT Surrogacy Laws in Louisiana: Complete Guide. Available from: https://surrogate.com/surrogacy-by-state/louisiana-surrogacy/lgbt-surrogacy-laws-louisiana/.

- Boydell V, Mori R, Shahrook S, Gietel-Basten S. Low fertility and fertility policies in the Asia-Pacific region. Glob Health Med [Internet]. 2023 Oct 31 [cited 2025 Sep 7];5(5):271–7. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10615026/.

- Semba Y, Chang C, Hong H, Kamisato A, Kokado M, Muto K. Surrogacy: Donor Conception Regulation in Japan. Bioethics. 2009 Nov 1;24:348–57. [CrossRef]

- Blazier J, Janssens R. Regulating the international surrogacy market:the ethics of commercial surrogacy in the Netherlands and India. Med Health Care Philos [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Sep 7];23(4):621–30. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7538442/.

- Prada drops Chinese actress over alleged surrogacy row. BBC [Internet]. 2021; Available from: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-55729437?

- Calvario L. Entertainment Tonight. 2019 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Everything Kim Kardashian Has Said About Surrogacy. Available from: https://www.etonline.com/everything-kim-kardashian-has-said-about-surrogacy-116451.

| Theme | Sub-themes | Example indicator | Exposure (who/what) | Determinants | Potential intersections | Relevant law / guidance | Policy strength | Policy weakness |

| Commissioning stance | “Not normally funded”; no payments; no recruitment | Policy text: no routine commissioning; no funding of surrogacy-specific elements or expenses | Intended parents seeking NHS-funded surrogacy-related ART | Medico-legal risk; affordability; enforceability | Same-sex couples; uterine-factor infertility; prior IVF failure | EMACC 2022; Gloucestershire ICB 2025 | Clear signal; consistent stance | Drives cross-border care; equity concerns. |

| Exceptionality / IFR | Strict, cohort rule | Exceptionality unlikely if a broader cohort would benefit similarly | IFR applicants | Resource stewardship; precedent aversion | Rare medical indications | EMACC IFR criteria | Transparent gatekeeping | Narrow access; opaque for patients. |

| Legal status | Altruistic vs commercial; unenforceable agreements; parental order | Surrogate legal mother at birth; transfer via court | Surrogates; commissioning parents; child | UK statutory framework | Overseas commercial contexts | Surrogacy Arrangements Act 1985; HFE Act 2008; HFEA info | Strong legal clarity | Practical friction with cross-border cases. |

| Parentage & nationality | Parental orders; nationality proof; consent hierarchies | HMPO accepts cases with/withoutparental order; sets consent steps | Child born via surrogacy; HMPO examiners | Safeguarding; identity; documentation | Birth jurisdiction; DNA | HMPO Surrogacy v11.0 (2025) | Child-centred, structured pathway | Administrative burden; delays. |

| Ethical/psychosocial risk | Disputes; child rejection; long-term psychological effects | Ethical list underpinning non-funding | Surrogate, intended parents, child | Uncertain outcomes; non-enforceability | Mental health; family dynamics | EMACC policy | Candid risk articulation | Limited mitigations beyond non-funding. |

| Safeguarding & fraud | Vulnerability checks; CPST referrals | Watchlist checks; CPST escalation | Applicants in inter-country cases | Unregulated markets; coercion | Trafficking risk; agencies | HMPO operational guidance | Robust safeguards | High evidential thresholds in emergencies. |

| Cross-border navigation | ETDs; no parental order handling | FCDO ETD workflow; continued case-holding | Families abroad; infants | Legal heterogeneity across states | Ukraine/other hubs | HMPO ETD process | Practical routes for urgent return | Prolonged separation; complexity. |

| Connected NHS care | Maternity care continuity | ICB commits to antenatal/postnatal support for surrogates | Surrogates in pregnancy care | Commissioning boundaries | Fertility preservation signposting | Gloucestershire ICB 2025 | Clarifies what isfunded | Fragmented patient journey across policies. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).