1. Introduction

1.1. Clinical and Economic Burdens of Root-Surface Loss and Periodontal Defects

When the periodontal ligament and root surface are lost, function does not merely decline; it reveals how patients feel with every bite and in daily social life. Periodontitis is highly prevalent worldwide and has substantial health, psychosocial, and economic burdens, including productivity losses and treatment costs, increasing its long-term impact on quality of life [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. These burdens persist because mechanical debridement controls biofilms but does not fully restore the original architecture and function of periodontal tissues, a limitation that undercuts durable functional recovery [

10,

12].

In everyday practice, conventional surgery and open-flap debridement often eliminate inflammation but can leave deep residual probing depths, a condition that is positively correlated with increased tooth loss risk, especially in teeth already judged questionable or hopeless after initial care [

5]. In contrast, regenerative surgery achieves superior clinical attachment gain compared with open-flap debridement in intrabony defects and is considered the treatment of choice for residual pockets of appropriate morphology [

5].

These clinical realities are mirrored in what patients value and how payers increasingly measure value. A systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that regenerative therapy improved patient-reported outcomes while remaining favorable in cost-effectiveness compared with extraction and replacement or access flaps alone, although a longer chair time and higher rates of membrane-related complications must be accounted for in value assessments [

12]. Economic analyses at the health system and population levels likewise indicate benefits for prevention and timely management, with model-based studies reporting cost-saving or cost-effective outcomes under realistic thresholds [

13].

However, currently, graft-and-membrane approaches are compromised. In routine use, resorbable membranes eliminate re-entry but can fail when their resorption rate does not keep pace with the velocity of new bone formation, causing premature loss of barrier function [

3,

10]. Contemporary reviews also underscore that traditional approaches often stabilize defects without recreating the hierarchical cement–PDL–bone architecture necessary for long-term biomechanical protection [

10].

A case-oriented lens sharpens the picture. In teeth with attachment loss extending to the apex, residual deep probing depths commonly persist after nonsurgical care, and the probability of extraction increases over time unless regeneration rebuilds the attachment apparatus; in this context, regenerative strategies can maintain vitality and improve prognosis compared with nonregenerative surgery [

5]. In short, the burden is twofold. Clinically, many current methods halt disease but do not recreate a ligament–cementum–bone continuum. Economically, technologies that improve patient outcomes while reducing complications and downstream replacement costs are needed to bend the cost curve [

12,

13].

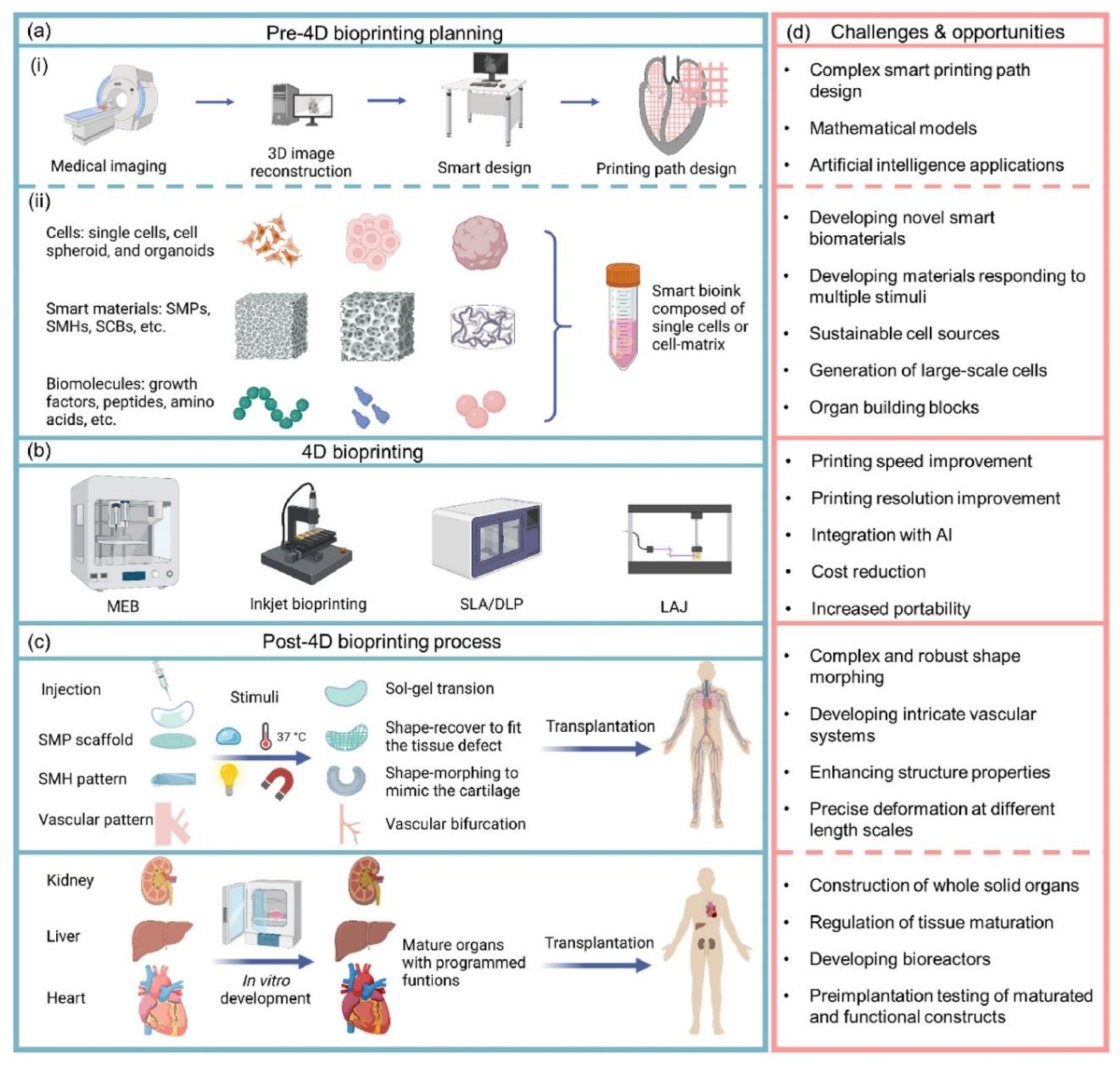

1.2. Convergence of PDL Stem Cells, 4D Bioprinting, and Gene Activation

Against this backdrop, three streams converge into a coherent regenerative strategy. First, periodontal ligament stem cells have moved from promising evidence to translational evidence. In a canine defect model, PDLSC-based tissue engineering constructs guided regeneration with new bone and new periodontal ligament forming in the defect while preventing the downgrowth of the junctional epithelium, thereby supporting structural repair rather than mere repair by long epithelial attachment [

7].

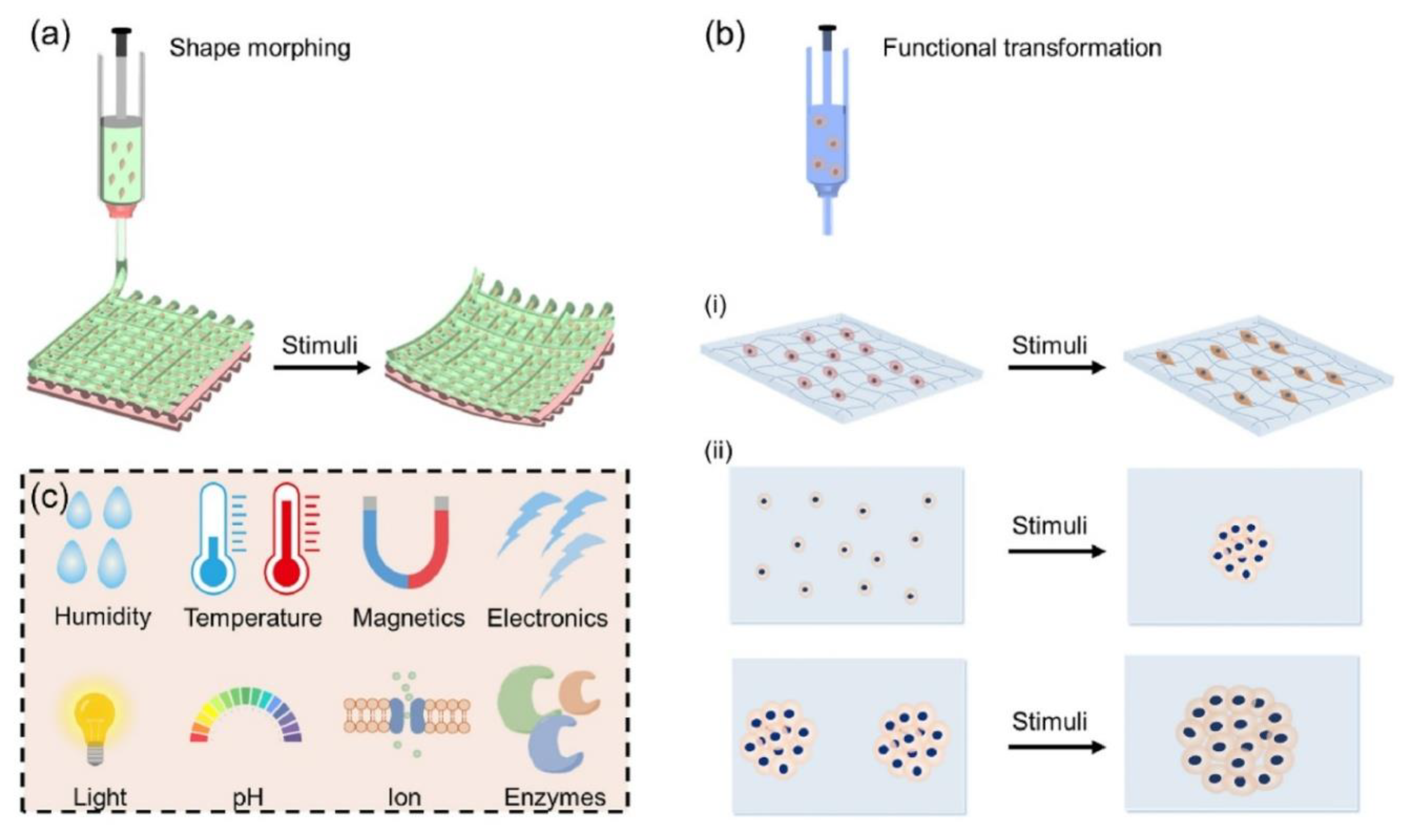

Second, 4D bioprinting reframes scaffolds as time-aware constructs. By pairing bioinks with stimuli-responsive designs, 4D printing programs print tissues to transform in response to cues such as temperature, pH, and light, which distinguishes them from static 3D printing through explicit time-dependent behavior [

1]. In dentistry, shape-memory systems already demonstrate clinically relevant traits, such as socket-conforming mechanics and hemostatic function for extraction site stability, together with stimuli-responsive platforms suitable for controlled drug delivery and cell encapsulation [

1,

2,

6].

Third, gene-activation tools now allow precise nudging of stem-cell fate. Sequence analysis predicted a primate-specific miR-2861 site in the 3′-UTR of HDAC5; CRISPR activation upregulated endogenous miR-2861, which represses HDAC5 and promotes osteogenic programs, including increased RUNX2 and β-catenin in human mesenchymal stem cells [

4]. (

Figure 1) shows that the miR-2861–HDAC axis lifts RUNX2 and aligns with Wnt and BMP inputs, promoting staged gene activation in RootFab [

4].

In periodontology, more broadly, CRISPR‒Cas platforms offer a dual axis of action that spans host or stromal modulation and antimicrobial editing directed at periodontal pathogens and inflammatory pathways [

11]. In addition to single loci, epigenetic regulation through histone methylation writers and erasers governs odontogenic and osteogenic differentiation trajectories in dental mesenchymal stem cells, providing further handles for durable lineage commitment [

14].

The potential of integration becomes evident when these streams are combined to address the clinical gap. A PDLSC-laden, 4D-printed construct that is hemostatic, socket-conforming, and mechanically stable at placement can secure the wound microenvironment and then deliver time-programmed cues that support hierarchical reconstruction of the cementum, ligament, and bone, whereas gene activation promotes and stabilizes osteogenic signaling during remodeling [

1,

2,

3,

4,

7,

9]. In this context, regeneration shifts from static patching to a self-adapting, gene-coached fabric that restores the root surface and its ligament as a living, load-bearing unit [

1,

7].

2. Biological Foundations and Mechanobiology

2.1. Hierarchical Periodontal Architecture and Stem-Cell Niches

Regeneration falters whenever engineered designs flatten the periodontium’s inherent hierarchy because the native complex functions as an integrated, load-bearing organ in which mineralized and fibrous phases interlock to transmit occlusal forces while permitting micromotion for proprioception. Multiphasic, layer-specific organization across the cementum, periodontal ligament, and alveolar bone is therefore a functional requirement for anchorage, stress dissipation, vascular perfusion, and long-term integration, not a cosmetic choice [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. With this blueprint, layered scaffolds that assign distinct compositions, porosities, and surface features to each compartment have already enabled concurrent soft-to-hard reconstruction and improved interfacial continuity in preclinical models [

28].

Two native cues are particularly instructive for RootFab 4D BioWeave. First, Sharpey-fiber insertion requires a PDL layer that supports highly oriented collagen bundles penetrating both the cementum and the bone. The cementum microstructure clarifies why acellular extrinsic fiber cement (AEFC) contains densely embedded extrinsic fibers, whereas cellular intrinsic fiber cement (CIFC) displays intrinsic bundles and a distinct mineral–fiber architecture. This anisotropy, with alternating patterns in the AEFC and circumferential systems in the CIFC, is directly tied to direction-dependent mechanics for ligament anchorage [

27]. Translating this to design means engineering an aligned fiber network in the ligament layer and a cementum-mimetic surface that together guide perpendicular PDL fiber insertion, an outcome emphasized in layered constructs that reproduce PDL orientation perpendicular to root surfaces [

27,

28]. (

Figure 2) depicts an ACP-to-HAP transition that yields an AEFC-like layer and perpendicular fiber insertion, illustrating the attachment geometry we target [

27].

Second, vascular gradients should be encoded to sustain fibroblasts, progenitors, and immunocytes while supporting osteogenesis at the bone interface. PDLSCs possess strong proangiogenic capacity, promote endothelial tube formation, and secrete angiogenic factors, including VEGF, positioning them as both cellular building blocks and vascular organizers inside engineered constructs [

22]. Endogenous homing approaches further show that chemokine-bearing frameworks can recruit host cells and rebuild complex periodontal tissues. Among these strategies, SDF-1α scaffolds recruit host stem cells and enhance periodontal repair, whereas BMP-7 coatings and CGF/IMC biphasic scaffolds produce PDL-like tissues with fibers inserted perpendicularly into the cementum and bone in vivo [

32].

These histoarchitectural and vascular insights converge on a practical directive: a trilayer scaffold that encodes cementum anisotropy, supports PDL fiber alignment, and establishes perfusion pathways, all while preserving interlayer adhesion and mechanical compliance under occlusal loading. Reviews of layered designs underscore that success depends on microstructural alignment and interlayer connectivity, not merely on material selection, and that coupling mechanical cues with biological readiness is essential to prevent failure modes such as ankylosis or downgrowth [

28]. In short, the periodontium itself supplies the blueprint: an anisotropic cementum for secure fiber insertion, a vascularized and aligned ligament core, and a graded transition into osteogenic bone, integrated as a single, load-capable organ [

18,

22,

27,

28,

32].

2.2. Gene Circuits and Mechanochemical Signaling

The genetic circuitry that stabilizes the osteoligamentogenic identity is tuned by biochemical ligands and dynamic loading. RUNX2 functions as a core node for osteoblast-lineage commitment, with BMP and Wnt inputs converging to drive matrix gene expression in dental mesenchymal stem cells [

19,

21]. In PDLSCs, canonical β-catenin signaling and noncanonical Wnt5a signaling modulate osteogenesis across different microenvironments, providing a programmable handle for gene-activated scaffolds [

29].

Under cyclic strain, mechanotransduction routes through RhoA–ROCK remodel F-actin and gate YAP nuclear import. Direct stretch experiments demonstrated that ROCK inhibition blocks YAP nuclear translocation, decreases the expression of osteogenesis-related genes, including RUNX2, and reduces mineral deposition, linking physiologic strain to transcriptional gain of bone genes [

23]. (

Figure 3A) synthesizes how mechanical strain functions through RhoA–ROCK to YAP/TAZ, coordinating the RUNX2 and Wnt programs that RootFab seeks to modulate [

24]. Periodontal reviews complement this by showing that YAP and TAZ display both distinct and overlapping functions in tooth development and periodontal homeostasis and are mechanoresponsive in ligament cells [

24].

Epigenetic control adds memory to this mechanochemical system. Histone methylation at osteogenic promoters, including RUNX2, regulates differentiation potency in dental mesenchymal stem cells [

19]. In force‒loaded PDLSCs, a KDM6B-driven H3K27 demethylation–Wnt self-reinforcing loop supports osteogenesis, whereas advanced glycation end products characteristic of metabolic stress disrupt this loop and impair osteogenesis [

31]. (

Figure 3B) illustrates how AGEs derail the KDM6B–Wnt loop that normally supports osteogenesis under loading, a context in which RootFab is designed to buffer [

31].

Together, these observations support a RootFab strategy that coencodes genes and forces a ligament layer that sensitizes Wnt signaling while reinforcing RUNX2-positive chromatin states and that delivers physiologic microstrain to recruit ROCK-dependent YAP activity, paired with a cementum-mimetic layer that biases RUNX2 targets toward fiber-anchored mineral deposition [

19,

23,

24,

29,

31].

2.3. Host–Graft Crosstalk and Immunomodulation

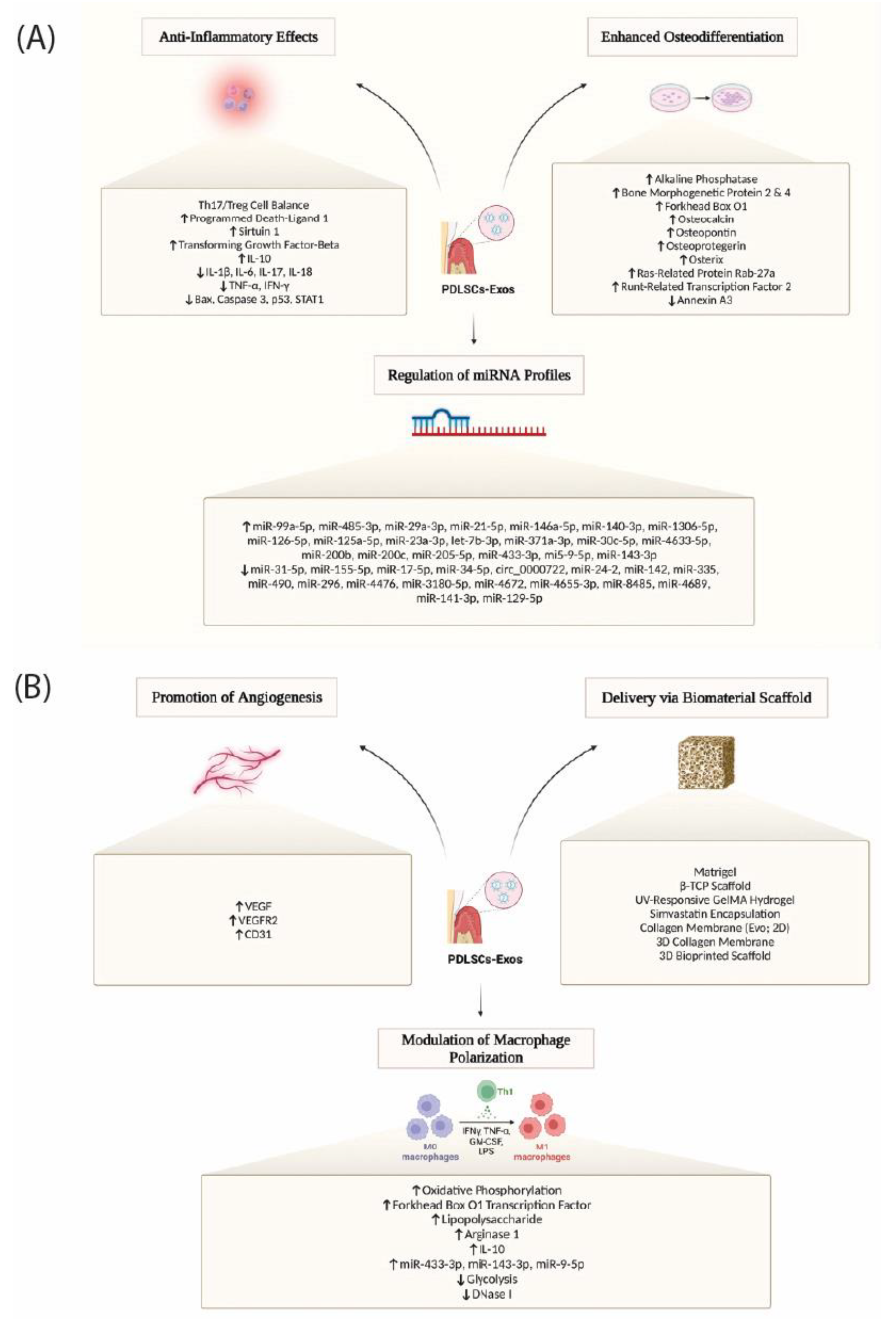

Durable regeneration depends on early inflammatory choreography that transitions into pro-healing immunity as vascular and fibrous compartments mature. PDLSC-derived extracellular vesicles are potent effectors in this phase. When embedded in supportive matrices, these vesicles enhance bone repair through adenosine receptor signaling and have been linked to immunoregulatory effects relevant to periodontal healing [

16]. (

Figure 4) integrates PDLSC exosome actions that we exploit in RootFab by coupling anti-inflammatory and osteogenic signals with scaffold-enabled delivery, pro-angiogenic cues, and M2-biased macrophage polarization [

16].

Biomaterial-guided immunotherapy further argues for purposeful macrophage polarization toward M2-like programs, since M2-biased environments are associated with improved bone and ligament regeneration in periodontitis models [

17,

25]. Within the same defects, cytokine fields shape the T-cell axis. IL-7–conditioned periodontal ligament cells rebalance local immunity by increasing Treg polarization, motivating designs that present IL-7 in controlled gradients to stabilize regulatory circuits during early healing [

26].

The mechanical context can be coupled to these immune programs through the scaffold architecture and presented cues. Rather than claiming that cyclic loading alone drives macrophage fate, current evidence suggests that engineered materials and delivered signals bias macrophage activation toward M2 programs that support matrix deposition, angiogenesis, and tissue remodeling in periodontal regeneration [

17,

25]. PDLSCs also show context-sensitive plasticity in hostile milieus. In diabetic wounds, transplanted hPDLSCs spontaneously adopt a myofibroblast phenotype with α-SMA expression and pro-healing secretory profiles that accelerate closure, suggesting that niche-specific ligands and stiffness cues can be productively harnessed [

20].

Finally, endogenous homing strategies illustrate how chemokine gradients can be paired with structural design to guide host–graft dialog. SDF-1α scaffolds recruit host stem cells and enhance periodontal repair, whereas BMP-7 coatings and CGF/IMC biphasic constructs generate PDL-like tissues with perpendicular fiber insertion into both the cementum and the bone in vivo [

32]. In RootFab 4D BioWeave, these loops become designable: load profiles regulate gene circuits, gene circuits reshape cytokine landscapes, and the immune milieu preserved by biomaterial-guided macrophage and T-cell responses stabilizes the very fibers and vessels that must carry future loads [

16,

17,

20,

25,

26,

32].

3. Material Platform and 4D BioWeave Engineering

3.1. Hybrid Bioinks and Nanofilament Reinforcement

Building a living, load-sharing root–PDL–bone interface begins with a material platform that carries stress like a membrane, communicates with cells like a matrix, and enriches the niche with ions that bias cementogenesis [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52]. Composite GelMA–PCL systems satisfy these demands by coupling the photopolymerizable, cell-interactive network of GelMA to the toughness and controlled resorption of PCL and then laying in bioactive ceramics that guide the lineage and mineral phase [

38,

45,

46]. In electrospun GelMA/PCL blends, post-fabrication photocrosslinking increases fiber diameter and stiffness, and the incorporation of cerium oxide enhances cellular metabolic activity and mineralized nodule formation, indicating that mechanical competence can be elevated in parallel with pro-regenerative signaling [

45].

A second reinforcement lever embeds calcium‒phosphate nanophases within the GelMA/PCL architecture. Nanoscale β-TCP in GelMA/PCL membranes improves cell attachment, upregulates osteogenic gene expression, and increases in vivo bone fill; as β-TCP degrades, it is expected to liberate Ca²⁺ and PO₄³⁻, which sustain mineral apposition [

44,

46]. This bioactivity-by-design logic is echoed in mesoporous bioactive-glass GelMA scaffolds, where the mesopores increase shape fidelity and surface roughness while releasing Si⁴⁺ and Ca²⁺, which promote osteogenic and cementogenic differentiation in human PDL cells, with increases in ALP activity and calcium nodules alongside ion release [

40].

Beyond generic osteogenesis, cementogenic bias can be tuned by specific ions. Lithium released from bioactive platforms activates Wnt/β-catenin signaling in PDL cells and drives cementogenic differentiation, and lithiated porous silicon nanowires reproduce this procementum signaling in vivo with enhanced periodontal regeneration outcomes [

34,

48].

Fibrous architecture is a third essential ingredient because ligament function emerges from orientation, not only from presence. Highly tunable fiber-reinforced hydrogels that interweave melt-electrowritten PCL meshes with GelMA demonstrate how a porous PCL skeleton stabilizes geometry and space, whereas the hydrogel phase provides a hydrated niche for integration and remodeling [

38]. In parallel, image-based fiber-guiding scaffolds use computed anatomy to impose channels that direct fibers toward root dentin, supporting the Sharpey-like bundle orientation across mineralized interfaces under load, an approach reinforced by systematic evidence that multicompartment, fiber-guiding or ion-containing printed scaffolds improve periodontal regeneration in animal models [

51,

52]. Recent trilayer constructions have extended this idea by stacking cementum-, PDL-, and bone-mimetic strata with angulated conduits and by tuning surface chemistry with collagen or GelMA coatings, thereby coupling directional guidance with adhesion and proliferation in a single printed body [

39]. The design choices that govern space maintenance, Sharpey-fiber guidance, and cementogenic bias are summarized in (

Table 1). Taken together, GelMA/PCL establishes a structural-biologic backbone, nanoceramics and bioactive glasses program cementogenic ion flows, and guided filaments prealign the force path from the bone through the PDL into the root, preparing the niche for true attachment rather than parallel scarring [

38,

39,

40,

44,

45,

46,

51,

52].

3.2. Stimuli-Responsive Shape-Memory Programming

A regeneration interface that moves with the tooth and settles into the sulcus must be programmable in time as well as space. Thermoresponsive PNIPAm motifs offer temporal control: across the LCST, they switch hydration state and volume, producing reversible mechanical work. When polydopamine nanoparticles are integrated into PNIPAm networks, the gels gain wet-tissue adhesiveness and photothermal responsiveness, enabling constructs that adhere under aqueous conditions and respond to gentle heat cues generated in situ [

35]. See (

Figure 5) for representative 4D morphing modes, functional transformations, and the stimuli that drive them [

1].

Bilayer strategies broaden the actuation palette. Copolymerizing PNIPAm with cationic DMAPMA and pairing with a clay-reinforced passive layer yields bilayers that bend and curl through coupled temperature and pH inputs. The observed curvature changes with pH and temperature are consistent with the protonation of DMAPMA segments at lower pH, altering swelling, whereas temperature modulates PNIPAm hydration, together producing fast, repeatable shape changes that can be encoded during fabrication [

41]. In cell-laden contexts, near-infrared addressability can be added without sacrificing viability: alginate–polydopamine bioinks undergo NIR-triggered shape morphing via the photothermal conversion of polydopamine, permitting postdeposition bending and fixation of 4D features under optical inputs that remain compatible with encapsulated cells [

36].

Within the RootFab concept, these demonstrated behaviors define practical levers: PNIPAm or PNIPAm-co-DMAPMA domains for gentle, reversible actuation under physiologic pH and temperature windows [

41]; polydopamine for transient photothermal inputs and tissue adhesiveness [

35]; and a background GelMA/PCL–ceramic matrix that provides mechanical support while delivering cementogenesis-relevant ions [

34,

40,

48]. The specific tuning knobs, experimental settings, and observed consequences are consolidated in (

Table 2).

3.3. 4D Printing Workflows and Real-Time Monitoring

The programming shape is useful only if it is delivered with micrometer-scale fidelity and verified in situ. A practical workflow couples energy delivery for rapid setting and actuation with vision-based correction and volumetric metrology. Photopolymerizable GelMA phases can be cross-linked during or immediately after deposition, and the same NIR light that actuates shape can provide mild photothermal input to aid postdeposition shaping; more directly, photoinitiator-integrated upconversion nanoparticles enable true NIR-mediated hydrogel curing for bioprinting, expanding the energy window beyond blue or UV sources [

36,

37,

38,

47]. On the motion side, a camera-guided tool‒path compensation loop compares planned and observed trajectories and nudges the nozzle to counteract deviations, improving dimensional fidelity on curves and corners that are common in root geometries [

49].

To guarantee subfeature fidelity, optical coherence tomography provides the missing third dimension at the printer speed. Integrated OCT tracks the layer height, filament width, pore size, and interlayer bonding in real time, enabling automated multiparameter evaluation; it has also been integrated with extrusion bioprinters to detect defects and trigger feedback control during printing. The reported axial and lateral resolutions are on the order of a few to tens of micrometers, supporting micrometer-scale tracking of features and interlayer conformity during construction [

33,

42]. When the construct demands finer features alongside viable cell densities, digital light platforms have demonstrated high-resolution bioprinting while preserving high cell density, setting a practical upper bound on feature size that aligns with OCT’s metrology envelope [

50].

In summary, RootFab 4D BioWeave advances along a single arc that is now tightly grounded in published evidence. Hybrid GelMA/PCL composites reinforce bioinks and host bioactive phases that deliver cementogenesis-relevant ions [

40,

44,

45,

46]. Stimuli-responsive domains then allow the weave to move and set under benign pH, temperature, and NIR cues compatible with cells [

35,

36,

37,

41,

47]. A coordinated printing-and-monitoring pipeline, from vision-based path correction to OCT-based real-time evaluation, locks that programmed architecture into place with micrometer-scale control [

33,

42,

49]. Fiber-guiding and trilayer scaffold strategies align the mechanical force path across interfaces and are supported by preclinical evidence for improved periodontal regeneration [

38,

39,

51,

52].

4. Gene-Activated Programming and Spatiotemporal Control

4.1. Vector Platforms with CRISPRa/i, Synthetic mRNA, and Inducible Plasmids

Regenerating a living root surface requires that periodontal-ligament stem cells (PDLSCs) be programmed to execute a sequence of gene activities that first lay down a cementum-like interface, then organize Sharpey-fiber insertion, and finally stabilize the enthesis under load [

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72]. This sequencing is not achieved by bolus protein delivery, which fades quickly and cannot be spatially patterned on complex root geometries. Gene-activated platforms solve that gap by embedding the “instructions” inside the construct so that cells contacting the material are transfected or transduced in place, with kinetics set by vector chemistry and scaffold microstructure [

53].

The first pillar is synthetic mRNA, which drives potent yet transient expression without genomic integration. Self-assembling or collagen-based hydrogels can soak-load or entrap modRNA nanoparticles, releasing them into infiltrating cells to produce enamel and ligament cues relevant to periodontal repair while avoiding the persistence inherent to plasmids and the risk of integrating viruses [

54]. In mesenchymal stromal cells, lipid-based carriers with chemically modified mRNAs outperform several alternative nonviral vectors and achieve robust expression from collagen-mineral composites, with expression windows tunable by dose and scaffold composition [

64]. Similarly, “mRNA-activated matrices” have accelerated osseous healing in rodent models, providing preclinical proof-of-concept for deploying modRNA payloads from implants to drive early morphogen surges without long-term transgene presence [

66].

A second pillar is plasmid DNA delivered by electrostatic complexes that can be embedded directly in the biomaterial. Chitosan condenses plasmids through ionic interactions to form nanoparticles that can be immobilized within collagen barriers or sponges. In periodontal models, such gene-activated matrices sustain plasmid release over several weeks, support in situ expression, and promote periodontal-like connective tissue and cementum formation, demonstrating localized, scaffold-coupled gene delivery suited to the root surface [

55]. When the required program calls for inducibility, plasmid cassettes can be fitted with ligand- or thermally responsive control elements cataloged in inducible CRISPR literature, enabling reversible CRISPRa/i without permanent edits [

63].

A third pillar is scaffold-mediated lentiviral transduction, which involves high-efficiency gene transfer to load-bearing frameworks. Poly-L-lysine functionalization of 3D woven polycaprolactone can immobilize VSV-G-pseudotyped lentivirus, resulting in greater than 80% transduction of infiltrating human MSCs and sustained expression of chondrogenic factors directly from the scaffold. The engineered tissues match growth factor supplementation in terms of matrix composition and mechanics while eliminating ex vivo conditioning, which is attractive for intraoperative seeding on irregular root defects [

58]. Finally, where on-the-spot patterning is desired, 3D microassembled electroporation chambers achieve multidirectional field scanning to permeabilize cells inside hydrogels, enabling direct delivery of CRISPR/Cas plasmids with controllable efficiency and high viability. This “in-print” electroporation paradigm reached approximately 15% transfection at approximately 87% viability in 3D culture, demonstrating feasibility for spatially addressable gene programming within a printed periodontal interface [

68].

Together, these vectors span transient modRNA bursts, inducible plasmid circuits, and stable but localized lentiviral expression. By mixing and matching them within one RootFab 4D BioWeave, one can stage CRISPRa/i-driven morphogen waves near cementum-facing zones, deploy mRNA pulses to bias PDLSC fate in the mid-ligament, and reserve viral modules for long-term trophic support where integration risk is justified by function [

53,

54,

58,

64,

66].

4.2. Light, Magnetothermal, and Mechanoresponsive Gene Switches

Once vectors are embedded, the construct still needs an external “conductor” that can cue genes in the right tissue zone at the right time. Optical control offers millisecond-scale precision, and with photothermal transduction, depth penetration is suitable for the periodontium. Reviews of spatiotemporal editing catalog blue‒light systems that assemble CRISPR activators or repressors on demand, enabling reversible CRISPRa/i with tight temporal gating [

71]. Near-infrared strategies involve coupling gold or polymeric photothermal converters with CRISPR complexes to trigger editing or transcriptional modulation under NIR irradiation, allowing remote programming at depth with minimal phototoxicity [

59]. The optogenetic deactivation toolboxes extend the palette, furnishing modular light-driven silencers to turn off transcriptional programs with spatial selectivity, which is valuable for shutting down proinflammatory cascades after the initial integration phase [

61].

Thermal logic adds a second orthogonal channel that can be delivered noninvasively. Heat-shock promoters in mammalian cells respond to brief, mild hyperthermia and are driven by programmed photothermal pulse trains to create digital-like on–off gene outputs [

67]. These same promoters have been wired to CRISPR-dCas9 regulators so that a few degrees of heating yield tunable activation or repression of target genes, enabling dose-dependent transcriptional control from a single promoter architecture [

69]. Magnetothermal approaches translate alternating magnetic fields into subablative heat at nanoparticle sites, which has been used to activate editing programs and amplify cell death in oncology models. The underlying principle, field-to-heat conversion at targeted loci, is equally adaptable to periodontal constructs for localized, repeatable promoter triggering without line-of-sight constraints [

70].

Finally, mechanical cues can be converted into therapeutic gene expression, turning the occlusal load into a regenerative signal. In chondrocyte-based tissues, mechanogenetic circuits that couple TRPV4 activation to synthetic NF-κB or PTGS2 promoters drive protective interleukin-1 receptor antagonist production under cyclic loading, achieving autonomous, load-responsive drug delivery in 3D constructs [

72]. PDLSCs possess the machinery to sense strain through the LINC complex and shuttle YAP into the nucleus under physiological stress, directly linking ligament tension to transcriptional outputs. This mechanotransduction axis provides a native handle for strain-gated control within gene circuits placed on the root surface [

57,

60]. In practice, a RootFab interface could combine an opto-CRISPR switch to ignite early cementogenic genes near the root, a magnetothermal heat-shock promoter to pulse matrix remodeling factors in deeper zones, and a mechanogenetic module that senses bite forces to release anti-inflammatory effectors during function, thereby aligning spatial control with the temporal realities of chewing and healing [

59,

67,

69,

70,

71,

72].

4.3. Closed-Loop Biosensing and Adaptive Feedback

Achieving root-surface curvature that persists under functional loading requires the scaffold to “feel” local mechanics and “act” with precisely dosed thermal cues [

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84,

85,

86,

87,

88,

89,

90,

91,

92], while gene programs sustain the biological response. In the RootFab 4D BioWeave, electrospun PVDF-rich piezoelectric meshes serve as the sentient layer, converting microstrain into real-time electrical signals as teeth encounter occlusal forces. Electrospinning enriches the electroactive β-phase in PVDF, improving piezoelectric output in flexible nanogenerators and yielding stable signals under bending or pressure that interface cleanly with low-power electronics [

74,

88]. These signals close the loop through a microcontroller that drives Joule microheaters in tightly timed bursts. The established microheater architectures use PWM or current control with PI or PID algorithms to deliver rapid, spatially confined temperature steps with degree-level precision [

91], whereas integrated, closed-loop PID/PWM control on printed-circuit platforms demonstrates practical heating-and-sensing codesign for microscale actuation [

81]. In periodontal constructs that must guide ligament fiber orientation across a cementum–PDL–bone gradient, such closed-loop actuation provides a controllable way to refine curvature locally without compromising the compartmentalized hierarchy that underpins functional integration [

86].

Fluorescent reporters complete the feedback architecture by quantifying what heat and strain achieve inside cells. Genetically encoded fluorescent biosensors enable ratiometric or intensiometric, real-time readout of signaling dynamics, supporting multiplexable monitoring during stimulation [

84]. For temperature specifically, recent GETIs permit organelle-level thermometry, enabling the controller to cap thermal pulses at safe set points while verifying delivery within targeted subcellular compartments [

83], as broadly surveyed in [

76]. Consistent with modern closed-loop therapeutics, sensor streams are processed on a microcontroller that executes model-based or PI control to trigger actuators in real time [

80,

92]. During periodontal repair, this loop interfaces with gene-activated materials that localize plasmid payloads within the scaffold, yielding sustained, spatially restricted protein production to reinforce curvature-guided fiber insertion and interface maturation [

85]. In practice, the piezoelectric layer senses strain, fluorescent reporters confirm the cellular state and temperature, and the controller determines short, patterned heat inputs to fine-tune the shape set by the scaffold’s anisotropy. This anisotropy already biases PDL fibroblast mechanosensing and alignment, as shown for aligned and grid-patterned PDL-mimetic mats that regulate YAP-linked behaviors and support in vivo PDL-like organization [

78].

5. Preclinical Evidence and Functional Outcomes

5.1. In Vitro PDL Organoid and Tooth-Slice Coculture Models

A coherent preclinical picture begins in reductionist systems that ask whether periodontal ligament stem cells can deposit matrix at dentin interfaces, recruit vessels, and maintain a nerve‒permissive interface. Bioprinted collagen constructs provide a controlled vantage point for early organization. In a rigorously characterized platform, PDLSC-laden collagen bioinks displayed shear-thinning rheology, stable swelling with controlled degradation, high postprint cell viability, and osteoperiodontal gene expression, including ALP, COL1A1, RUNX2, and OCN [

93,

94,

95,

96,

97,

98,

99,

100,

101,

102,

103,

104]. Crucially, when printed onto dental root fragments and implanted subcutaneously in mice, PDLSCs aligned parallel to dentin and remained attached at the root surface at 4 and 10 weeks, indicating anatomically faithful organization on the tooth substrate rather than undirected osteogenesis [

96]. These observations situate early matrix deposition and cell patterning within a bioink context that preserves print fidelity long enough for PDLSCs to attach to dentin and continue aligning in vivo over several weeks without asserting mechanistic causality beyond the experimental sequence [

96].

The scaffold microarchitecture further tunes early PDLSC behavior. Compared with that of random fibers, the wettability of plasma-treated electrospun polycaprolactone nanofibers increased with a reduced water contact angle, and aligned fibers promoted greater PDLSC adhesion and proliferation with contact-guided orientations; the same study did not quantify extracellular matrix accrual, so alignment and proliferation are the supporting endpoints [

97].

Angiogenic competence is the next hurdle, and two complementary datasets converge. A donor-paired comparison revealed that PDLSC- and DPSC-conditioned media induced comparable HMEC-1 tube formation, with broadly similar VEGF-A expression and secretion, supporting a robust PDLSC proangiogenic program under matched conditions [

98]. A jaw-site pilot sharpened this signal by showing that maxillary PDLSCs secreted more VEGF and drove denser, faster HUVEC network formation than mandibular PDLSCs did, alongside differences in angiogenesis-related transcripts, which is consistent with site-dependent modulation of sprouting kinetics in vitro [

104].

Neurointegration readouts remain less standardized, yet an in vivo-inspired framework is in place for later proprioceptive testing. In rats, press-fit, deliberately nonosseointegrating implants with a stem-cell-laden elastomeric nanofiber coating preserved a soft-tissue interface; micro-CT at six weeks revealed a peri-implant radiolucent gap of approximately 0.7 to 0.9 mm, which is consistent with a nonosseous, nerve-permissive space designed for trigeminal reconnection in future assays [

102]. Taken together, these in vitro, ex vivo, and interface-mimetic platforms show that RootFab-style PDLSC constructs can align on dentin, signal to the endothelium, and are coupled with neurocentric interfaces that preserve a putative corridor for nerve ingrowth [

96,

98,

102,

104]. (

Table 3) consolidates these platforms, listing the material context, cell source, endpoints quantified, representative findings, and the specific RootFab design inferences they support.

5.2. Small-Animal Periodontal Defect Studies

Translating these design cues into living defects reveals a coupled tissue–microbiome response. In a rat fenestration model, local delivery of antibacterial PDLSCs improved periodontal regeneration and rebalanced the postoperative oral microbiome, with micro-CT and histologic gains accompanied by restored diversity, enrichment of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, and upregulation of LL-37, indicating that a single cellular intervention can comodulate repair trajectories and microbial ecology during early healing [

95]. Because postsurgical dysbiosis can slow ligament reattachment, these data place matrix deposition kinetics within an immunoecologic context that is amenable to cell-based tuning in small animals [

95].

Across rodent studies, quantitative mineral outcomes are now sufficiently numerous for synthesis. A meta-analysis of 17 preclinical trials of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes reported significant gains in BV/TV with a large pooled standardized mean difference, higher BMD, reduced CEJ-to-alveolar crest distance, and lower trabecular separation, while heterogeneity in dosing, scaffold context, and follow-up duration was noted; preconditioned exosomes outperformed unmodified preparations for BV/TV, and route or dosing frequency did not significantly alter effect sizes [

93]. These practical levers provide a rationale to pair gene-activated PDLSCs with optimized exosome support in future RootFab constructs while keeping outcome heterogeneity in view [

93].

Tissue specificity beyond minerals is essential for a ligament-anchored interface. In the mouse root–fragment model, PDLSC-laden collagen prints produced aligned PDLSC arrays on dentin and directed migration to the root surface at 4--10 weeks, which was consistent with rebuilding the insertional interface rather than adding bone alone [

96]. These in vivo observations dovetail with contact guidance on anisotropic PCL scaffolds, reinforcing that microscale alignment can translate into an organ-scale orientation during healing; the PCL study directly supports alignment and proliferation without ECM quantification, which bounds the inference appropriately [

97].

Neurocentric integration is beginning to be operationalized. In the rat press-fit model designed to avoid rigid osseointegration, micro-CT confirmed maintenance of a 0.7--0.9 mm soft-tissue space at six weeks, a geometry that could allow neural terminals to reconnect to the stem-cell-bearing coating and set the stage for later proprioceptive evaluation rather than bone-to-implant ankylosis [

102].

Two gaps deserve emphasis for small-animal pipelines. First, despite frequent histology and micro-CT endpoints, standardized pull-out strengths of the regenerated PDL–cementum complex and mastication-cycle fatigue tests were not reported in the small-animal studies cited here, which constrains direct statements about attachment mechanics and endurance [

95,

96,

102]. Field reviews urge judging success by integrated, multitissue regeneration rather than bone-centric metrics, a view that supports adding explicit mechanical and functional benchmarks to future protocols without prescribing a specific test battery here [

103]. Second, while antibacterial PDLSCs restore a favorable microbiome in rats, cross-species durability and interactions with engineered exosome payloads remain to be tested in a unified defect pipeline to link immune ecology, matrix organization, and function [

93,

95].

5.3. Large-Animal Insights and Translational Gaps

Scaling to large animals is feasible, and the remaining steps are fully functional. In swine with two-walled infrabony defects, autologous buccal-fat-pad–derived dedifferentiated fat cells produced clinically meaningful attachment gains at 12 weeks, with new continuous cellular cementum and alveolar bone bridged by organized periodontal-ligament-like fibers; histometrics documented approximately 2.2-fold increases in new alveolar bone length and neovascularization compared with those in controls, and no teratomas were detected, demonstrating vascularized, fiber-anchored regeneration in jaws at the human scale [

100]. Similarly, canine models remain a proving ground for integrated multitissue constructs and cell-based strategies, underscoring design principles for concurrent cementum, PDL, and bone regeneration at scale [

103].

Meta-science places these results in context. Bibliometric mapping from 2000--2023 revealed rapid growth around hydrogels, electrospinning, melt electrowriting, 3D printing, and exosomes, while stressing that clinical-level evidence for these modalities remains limited, which frames near-term translation goals realistically [

101]. Mechanistic reviews reiterate that genuine periodontium regeneration requires new cementum with correctly inserted fibers, a criterion that is still challenging to reproduce consistently across models [

99]. For RootFab 4D BioWeave, these insights argue for large-animal studies that pair scale-appropriate anisotropic scaffolds with gene-activation strategies, such as BMP-2 mRNA-transfected BMSCs, which outperform direct BMP-2 mRNA–LNP delivery in a cranial-bone context while prespecifying pull-out strength, fatigue-cycle loading, and neurophysiological endpoints prior to first-in-human work [

94,

103].

6. Biomechanics and Long-Term Functional Integration

6.1. Stress–Strain Matching and Fatigue Under Masticatory Loads

Durable reattachment at the root surface begins with reproducing how the native complex is stored and dissipates energy across each chewing cycle. When viscoelasticity is tuned to periodontal-ligament–like stress relaxation, periodontal-lineage cells experience constructive mechanotransduction under cyclic loading rather than damage accumulation, which in turn stabilizes the cement–ligament–bone interface [

105,

106,

107,

108,

109,

110,

111,

112,

113,

114,

115]. In a viscoelastic design program that illustrates this principle, Pluronic F127 diacrylate systems were matched to physiologic relaxation behavior, supported PDLSC fibrogenic responses under controlled loading, and, in a delayed replantation model, limited ankylosis and root resorption, linking damping kinetics to favorable tissue remodeling in vivo [

111].

Shape-memory architectures convert those cell-scale advantages into construct-level fatigue resilience. A gelatin-based shape-memory scaffold showed rapid, body-temperature recovery, with 95.8% shape recovery at 37 °C and a return from the temporary shape to the original shape within approximately 30 s, a response window well suited to resetting local overstrain events before they accumulate as fatigue damage [

110]. Similarly, a porous PLGA-g-PCL scaffold copolymerized with PPDL was engineered so that the PPDL transition temperature exceeded the recovery temperature, preserving higher stiffness after recovery while still self-fitting; in rabbit extraction sockets, micro-CT and histology confirmed efficient alveolar bone filling [

107]. In the same design space, reports on shape-memory polyurethane scaffolds emphasize programmable, thermally responsive behavior in porous constructs for soft-tissue repair, which supports the concept of geometry reestablishment under service conditions without asserting a specific body–temperature actuation profile for any one formulation [

112]. Finally, recent skin-mimic elastomers unite damage resistance with body-temperature shape memory and demonstrate high fatigue tolerance, offering a material paradigm for resisting crack initiation and growth under high-cycle occlusal loading environments [

113].

Matching ligament-level stiffness is equally consequential for how occlusal forces traverse the tooth–PDL–bone ensemble. Image-based finite element analyses that calibrated the periodontal-ligament modulus recommended an effective PDL modulus of 0.964 ± 0.276 MPa for realistic tooth kinematics and cautioned that using lower moduli can bias stress–strain transfer by overestimating tooth displacement and altering predicted motion patterns [

115].

6.2. Finite Element Modeling and In Vivo Imaging of Triphasic Mechanics

Quantifying how load paths evolve from enamel to cementum to alveolar bone is essential for engineering stability at the regenerated root surface. CT-based finite element pipelines now trace the full workflow from clinical imaging and segmentation to mesh generation, material assignment, and occlusal loading, producing interpretable stress and deformation maps that highlight where and why mechanical concentration arises in tooth–restoration or tooth–scaffold assemblies [

114]. These models are highly sensitive to the ligament input, and analyses that systematically vary the PDL modulus show that selecting values outside a physiologic range shifts the predicted tooth kinematics and stress fields, underscoring the central role of ligament properties in governing load transfer through the cushion of the PDL [

115].

Imaging-validated mechanics close the loop between design and performance. In situ mechanical testing coupled with synchrotron microtomography with digital volume correlation resolves three-dimensional strain fields in musculoskeletal tissues and biomaterial interfaces, enabling direct comparison of measured and simulated deformation in complex, multitissue assemblies [

106]. At the tissue scale, micro-CT already supports in vivo evaluation of integration outcomes for shape-memory scaffolds in extraction sockets, where reconstructed volumes and density metrics quantify regeneration alongside histology [

107]. This CT-to-FEA-to-imaging loop therefore does more than describe mechanics. It operationalizes design rules that are testable in models and observable in living tissue: it tunes viscoelastic damping to PDLSC-beneficial regimes [

111], selects ligament moduli that avoid pathological kinematics [

115], deploys shape-memory stiffening to preserve geometry under repeated chewing loads, and then verifies all three with DVC-resolved strain maps and micro-CT endpoints [

106,

114].

6.3. Neural Integration and Proprioceptive Restoration

Long-term function requires more than structural union. The regenerated interface must re-enter the trigeminal sensorimotor loop so that bite force is dosed reflexively rather than imposed blindly. Periodontal-ligament stem cells are positioned for this purpose. A focused review identified PDLSCs as promising therapeutic targets for neural damage and noted their neurotrophic and immunomodulatory profiles along with evidence of their potential for SC differentiation, which together support strategies aimed at reinnervation during periodontal repair [

105]. Topographical control of mechanotransduction then links neural potential to functional fiber guidance at the root surface. Periodontal-ligament-mimetic fibrous scaffolds that vary surface topography regulate YAP-associated fibroblast behaviors and promote regeneration of periodontal defects in relation to scaffold topography, aligning the cellular and architectural prerequisites for physiologic mechanosensing [

108].

Electrophysiology offers a practical, noninvasive readout of sensory pathway engagement. Trigeminal somatosensory-evoked potentials are designed to evaluate the integrity of trigeminal nerve pathways in the maxillofacial region, and a dual-case pilot study highlights their feasibility and potential as an adjunctive method for assessing sensory function around oral interventions [

109]. Within this program, scaffold mechanics and topography can be iterated in light of electrophysiologic readouts, with PDLSC-based neuroregenerative capacity and YAP-sensitive fiber architectures providing mechanistic levers to restore proprioceptive feedback at the tooth–PDL–bone complex [

105,

108].

7. Biosafety, Immunogenicity, and Bioorthogonality

7.1. Off-Target Gene-Editing Surveillance and Kill-Switch Design

Therapeutic gene programs in RootFab 4D BioWeave must demonstrate precise activity and predictable shutdown. A rigorous pipeline begins with unbiased discovery of collateral nuclease activity, since prediction alone can miss clinically relevant sites [

116,

117,

118,

119,

120,

121,

122,

123,

124,

125,

126,

127,

128,

129,

130,

131,

132]. CIRCLE-seq offers a high-sensitivity, cell-free map by circularizing genomic DNA, exposing it to Cas9–gRNA, and using deep sequencing to recover on- and off-target cuts. This format is well suited for preclinical guide selection and head-to-head comparisons of candidate editors [

119]. In engineered primary stem cells, cell-based readouts confirm which in vitro candidates are important in living genomes. In human primary muscle stem cells, efficient on-target repair was paired with genome-wide GUIDE-seq analysis, which revealed very low off-target activity at nominated sites [

124]. To reduce off-target liabilities further, paired Cas9 nickases require two nearby single-strand nicks to form the intended double-strand break, leaving most off-target events as repairable single nicks. In primary human cells, a paired-nickase design preserved on-target efficiency, eliminated detectable off-target translocations via the paired approach, and revealed an on-target signature of larger deletions with templated or duplicative insertions. These data argue for routine profiling of on-target structural variants as part of safety qualification [

125].

Surveillance must be coupled with control. A layered kill-switch architecture enables the termination of edited PDL-SCs if they misbehave or overpersist. A clinically actionable first layer is rapamycin-activated caspase-9, which dimerizes under drug control and triggers rapid apoptosis. Variants have been optimized in human T cells and have demonstrated safe use in the context of experimental therapy [

127]. A second, orthogonal layer based on HSV-TK with ganciclovir supports sequential activation for fail-safe clearance when one agent is insufficient in vivo [

126]. For day-to-day dosing of transgene activity without ablation, a simeprevir-inducible, HCV-protease-based chemical dimerization system actuates transcriptional programs and can be wired to proapoptotic effectors, providing a bioorthogonal switch with tunable apoptosis [

116].

7.2. Scaffold Biocompatibility, Degradation Products, and Foreign-Body Response

The 4D weave must degrade in step with healing, bias innate immunity toward repair, and avoid the foreign-body loop. Two complementary testing tracks anchor this assessment. First, standardized extract testing and hemocompatibility were performed: GelMA-BG composites were evaluated via material extracts prepared per ISO 10993-12 for in vitro assays, providing a consistent extract-based framework for hydrogel blends [

129]. In parallel, anisotropic PCL-GelMA-ChsMA heart valve scaffolds presented reduced platelet adhesion and hemolysis ratios of 3.6 to 2.8%, indicating favorable hemocompatibility of PCL-containing architectures [

128]. Second, macrophage-phenotype profiling captures real tissue conversation at the implant surface. Magnesium-incorporated PCL scaffolds shifted innate immunity toward pro-regenerative M2 states in vivo, as demonstrated by CD11b/c, CD68, and CD206 immunostaining, with concurrent enhancement of tendon–bone healing outcomes that are conceptually translatable to periodontal interfaces [

121].

Degradation should be coupled with osteogenic cues rather than sterile inflammation [

130]. Melt-electrowritten bioglass-laden PCL constructs were biocompatible in vivo and proangiogenic over 7 to 28 days, with more visible structural changes by 28 days without adverse tissue reactions [

120]. In GelMA-forward blends, reinforcing hydrogels with PCL@GelMA nanofibers and bioactive glass closed critical-size cranial defects while increasing the levels of osteogenic and angiogenic markers, suggesting a degradation milieu that favors mineralization rather than fibrous encapsulation [

129]. Finally, anisotropic PCL-GelMA-ChsMA valves supported dense endothelialization, reduced immune infiltration, and decreased calcification compared with those of isotropic controls, revealing how architecture and chemistry together can divert the foreign-body response as scaffolds resorb [

128].

7.3. Microbiome Interactions and Immune-Stealth Coatings

The regenerated root surface sits at a biochemical level where saliva, mucus, and biofilms negotiate adhesion. Small molecules such as mutanofactins strengthen

Streptococcus mutans biofilms and modulate mucin‒bacteria interactions, underscoring the need for surfaces that do not become privileged substrates for colonizers [

122]. A mucus-mimetic, zwitterionic overlayer provides a first line of defense. Phosphorylcholine and related zwitterionic hydrogels create a tightly bound hydration shell that resists nonspecific protein adsorption and early bacterial attachment, thereby lowering initial fouling at the material interface [

117,

130]. When the infection pressure increases, the coating should respond rather than be merely repelled. Microenvironmentally responsive hydrogels that sense acidic pH, reactive oxygen species, or infection-associated enzymes can deliver quorum-sensing antagonists within infected tissue, disrupting communication-driven biofilm maturation and reducing the osteomyelitic burden [

118]. In

Staphylococcus aureus, antagonists that inhibit the agr quorum-sensing locus suppress biofilm maturation, and agr-linked targets can be engaged alongside responsive delivery for targeted interference [

118,

123]. Together, stealth hydration layers and microenvironment-triggered quorum interference create a surface that remains quiet in health yet acts decisively under a pathogenic quorum.

8. Manufacturing, Regulatory, and Reimbursement Pathways

8.1. GMP-Compliant 4D Printing and Closed Loop Cell Processing

Scaling RootFab 4D BioWeave from benchtop ingenuity to first-in-human readiness hinges on one theme: building sterility and measurement into the process, not around it. Conventional bioprinting often relies on biosafety cabinets that are aseptic rather than truly sterile, and ultraviolet fixtures inside these enclosures are unreliable for complex geometries [

133,

134,

135,

136,

137,

138,

139,

140,

141,

142,

143,

144]. A confined, pressurizable printing and culture chamber that physically isolates the construct provides a more defensible sterility backbone, as shown by an inflatable bioreactor that maintained sterility across challenge scenarios while permitting needle access and gas exchange [

142]. Within that boundary, RootFab’s 4D printability depends on verifying rheology in real time because viscosity and gelation drift during dispensing drive filament width, pore fidelity, and ultimately shape-memory actuation. Image-based flow-rate tracking during dispensing provides time-stamped viscosity estimates without interrupting the run, enabling on-the-fly pressure or speed adjustments before defects accumulate [

141]. Closed-loop stability is the next layer. A printeragnostic in situ monitoring platform has demonstrated on-axis microscopy with automated segmentation that correlates with ex situ measurements, identifies a critical velocity threshold for stable lines, and maps geometric deviations along the toolpath, which together support adaptive control to actively stabilize print quality [

139]. Prioritize automated in-line or at-line testing for release criteria such as identity, purity, and potency, whereas sterility and adventitious agent testing are handled through validated aseptic processes and appropriate assays [

140]. Closed, automated cell-manufacturing lines for cell therapies have integrated automated formulation and bag filling with successful technology transfer across multiple facilities [

133]. Practical thread for RootFab: relies on a physically confined bioprint-and-culture vessel for sterilization control rather than ambient UV exposure, pairs it with real-time rheometry and vision, and connects the printer to a closed, automated QC lane so that the same process that prints the construct certifies it for release [

139,

140,

141,

142].

8.2. Combination-Product Classification and ISO 10993 Compliance

Because RootFab couples a living periodontal-ligament stem-cell construct with gene-activation components and a bioactive, degradable scaffold, it fits the definition of a combination product that merges a biologic with a device. Determining the lead center, regulatory pathway, and cGMP expectations begins with a formal designation that accounts for constituent parts, their mode of action, and how they are copackaged or cross-labeled, as outlined in the NIH SEED Regulatory Knowledge Guide for Combination Products [

143]. For the scaffold and any printing hardware materials that contact tissue or fluids, ISO 10993-1 recommends a risk-management framework that begins with device contact mapping, uses the FDA-modified endpoint matrix, and selects only those biocompatibility and chemical characterization tests that are justified by risk and exposure duration. The same framework specifies expectations for in situ polymerizing or absorbable materials and clarifies when the finished-form article must be tested [

135]. Gene activation has triggered the parallel application of the FDA’s genome-editing guidance for human gene therapy. IND content should address editor and delivery design; manufacturing and testing controls for each editing component; nonclinical assessment of activity and safety; and clinical monitoring with attention to off-target editing, unintended on-target consequences, and long-term follow-up, including phase-appropriate testing for identity, purity, sterility, activity, potency, on-target efficiency, off-target risk, and long-term follow-up where appropriate [

134].

8.3. First-in-Human Trial Design and Health Economics Modeling

A persuasive first-in-human protocol should demonstrate that RootFab restores attachment and stability while improving how patients feel and function and that it delivers value. Endpoints can be structured as a hierarchy that mirrors decisions in practice: a primary histo-clinical surrogate of true regeneration, such as clinical attachment level gain at a defined intrabony site; key secondaries that reflect functions such as tooth mobility and retention; and patient-reported outcomes that capture pain, chair time, esthetics, satisfaction, and oral health-related quality of life. PROMs are technique sensitive; barrier membranes can lengthen the chair time and increase early complications, and minimally invasive approaches often reduce postoperative pain. EMD results in similar pain to access flaps in some analyses [

138]. Economic evaluation should be prespecified rather than retrospective. A Markov model is feasible in dentistry and can express benefits such as tooth-years retained and quality-of-life gains, with incremental cost-effectiveness ratios calculated against willingness-to-pay thresholds [

138]. Related modeling in endodontics illustrates that not all regenerative strategies dominate comparators over a lifetime horizon [

144]. In a base-case lifetime analysis, regenerative endodontics incurred an additional cost of USD 1,012 with fewer retained tooth-years at 15.48 than 16.41 for MTA apexification, yielding an ICER of USD −1,090.46 per retained tooth-year, which underscores the value of transparent assumptions and sensitivity analyses [

144]. Trial blueprint for RootFab: anchor the primary endpoint in attachment gain at 12 months, track mobility and tooth survival through 24 months, collect PROMs and resource use prospectively, and fit a Markov model that reports ICERs per tooth-year retained and per improvement in validated quality-of-life indices [

138,

144].

9. Future Horizons and Digital–Twin Personalization

9.1. AI-Guided Scaffold Morphogenesis and Patient-Specific Digital Twins

Personalization becomes actionable where imaging, mechanics, and manufacturing converge. In practice, high-resolution micro-CT geometries segmented into enamel, dentin, pulp, and surrounding cortical and cancellous bone have been converted to finite-element meshes to quantify interfacial stresses in tooth–inlay systems and to define contact behavior at restoration margins [

145,

146,

147,

148,

149,

150,

151,

152,

153,

154,

155,

156,

157,

158]. Reviews in personalized dentistry place these pipelines within a broader in silico workflow that integrates CBCT and micro-CT for more realistic, patient-specific models and chairside decision support [

153]. Once meshes exist, generative frameworks can shape architectures to redistribute stress toward prescribed targets. A Nature Communications study demonstrated a design loop that predicts elastic properties with machine-learning models, evaluates stiffness and stress fields through simulations, and validates outcomes experimentally and numerically, achieving precise stress modulation with 3D-printed samples [

152]. This logic aligns with reviews showing machine learning as a bridge between data and constitutive behavior for topology and property optimization in tissue engineering contexts [

155]. Digital-twin thinking in dentistry links image-to-mesh, mesh-to-design, design-to-print, and print-to-feedback [

156], whereas additive-manufacturing guidance clarifies expectations for software workflows and patient-matched device designs [

157]

(Figure 6) and integrates a digital-twin loop with RootFab’s 4D printing and postprint maturation, consolidating the workflow and monitoring steps described earlier [

1]. In parallel, gene-activated matrices locally transfect host cells for sustained therapeutic secretion, allowing the twin to coordinate vector, dose, and scaffold parameters toward durable periodontal attachment [

145,

147].

9.2. Self-Healing, Sensor-Driven Remodeling, and Adaptive Implants

A long-term function will favor constructs that repair, sense, and adapt. Microcapsule-based dental composites exhibit autonomous repair: crack-triggered capsule rupture releases healing agents that rebond damaged regions and restore integrity [

150]. Hydrogels provide compliant, cell-compatible interfaces and drug depots, and contemporary systems can be engineered for controlled, stimuli-responsive release profiles [

148]. In dental settings, 4D printing has been discussed for shape-memory responses that change geometry or stiffness in the oral environment, and GelMA hydrogels have been used to encapsulate periodontal ligament stem cells to facilitate bone regeneration in vivo [

149]. Wireless, batteryless implantable electronics enable continuous, real-time physiological readouts without bulky power sources, with reviews detailing device architectures, energy harvesting, and tissue-conformal implementations [

151]. Architected lattices then offer a lever for maintaining local stresses within target windows, since bioinspired irregular microstructures can steer shear and hydrostatic stress toward design goals under load, with experimental and numerical agreement demonstrated on 3D-printed samples [

152].

9.3. Open-Source Bioprinting Standards and Global Collaboration Roadmaps

Interoperability determines the pace of multicenter progress. The FAIR principles define data and metadata that are findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable, with explicit emphasis on machine-actionable metadata and clear provenance that directly support digital-twin traceability [

146]. In parallel, additive-manufacturing guidance describes design-to-manufacture pathways, file conversion and verification steps, and considerations for patient-matched devices and software workflows, framing how research pipelines move toward regulated translation [

157]. State-of-the-art architected material studies strengthen reproducibility by providing detailed methodological descriptions and data availability with supplementary information sufficient to reconstruct model construction and validation, enabling reuse in biomechanical contexts [

152]. On the modeling side, finite element overviews in dentistry advocate platform approaches that combine dental imaging with material libraries and computational mechanics for personalized planning [

153]. Machine learning reviews emphasize standardized datasets and validation pipelines that can underpin certification tracks for models transitioning from exploratory design to clinical decision support [

155]. The result is an ecosystem where meshes, G-codes, and parameterized scripts travel with provenance-rich data packages, reducing duplication and accelerating convergence.

9.4. Funding Landscapes and Ethical Considerations in Gene-Activated Bioprinting

Translation is gated by durable benefits and long-term safety. FDA guidance calls for risk-based long-term follow-up after the administration of human gene therapy products, including prospective monitoring for delayed adverse events with prespecified schedules and data collection plans [

158]. Gene-activated materials provide a mechanistic rationale for sustained local protein delivery by transfecting host cells within the scaffold environment, which can reduce reliance on high-dose exogenous factors [

145,

147]. Regional gene therapy reviews catalog vector platforms and scaffold couplings relevant to skeletal and craniofacial repair, outlining feasibility and risk considerations that inform periodontal applications [

147]. Methodologically, machine-learning frameworks for biomaterials and biomanufacturing stress standardized datasets, staged validation, and model documentation offer a path to prespecified acceptance criteria and uncertainty reporting from bench studies toward larger-scale evaluation [

155]. Ethical stewardship therefore hinges on transparent longitudinal monitoring, robust data and code provenance across institutions, and inclusion of patient-specific mechanics in success criteria so that integration is judged by stable load sharing as well as attachment over time.

10. Conclusions

RootFab 4D BioWeave represents a fundamental paradigm shift in periodontal regeneration, moving beyond the static replacement of lost tissue toward the dynamic, gene-coached reconstruction of a living, load-bearing, and functionally integrated organ. The central thesis of this work is that the well-documented limitations of current regenerative therapies, namely, their inability to consistently restore the hierarchical cement–PDL–bone complex and its intricate biomechanical competence, are not incremental problems to be solved with better materials alone. Rather, they represent a categorical failure to replicate the developmental and homeostatic logic of the native periodontium. Our proposed platform directly confronts this challenge by weaving together three synergistic technological streams: the intrinsic regenerative potential of periodontal-ligament stem cells (PDLSCs), the spatiotemporal precision of stimuli-responsive 4D bioprinting, and the programmable control of gene-activation circuits. This integrated approach reconceptualizes a regenerative scaffold not as a passive placeholder but as an autonomous, “intelligent” construct capable of sensing its environment, executing preprogrammed morphological changes, and directing cellular fate with unprecedented precision. The biological foundation of RootFab rests on a deep respect for the native histoarchitectural blueprint. We have synthesized extensive evidence underscoring that functional attachment is contingent upon recreating the anisotropic, multitissue gradient that defines the root surface. This requires a material platform that can simultaneously guide Sharpey-fiber insertion, establish perfusion pathways for vascular and immune cell trafficking, and present localized biochemical and ionic cues that bias PDLSC differentiation toward cementogenic and osteogenic lineages. Our proposed hybrid bioink system, a composite of GelMA for cell interactivity, PCL for tunable toughness, and embedded nanoceramics such as mesoporous bioactive glasses or lithium-releasing particles for programmed ion release, is engineered to meet these multifaceted demands. This tri-layer scaffold encodes cementum anisotropy, ligament alignment, and graded osteoconductivity, providing PDLSCs with a blueprint that mirrors the native organ. This material substrate is then endowed with a fourth dimension, time, through the incorporation of shape-memory polymers. This enables the construct to autonomously deploy, conforming intimately to complex defect topographies and establishing a mechanically stable wound environment critical for the initial phases of healing. This shape-memory dynamic, driven by benign thermal, pH, or near-infrared cues, ensures that the scaffold achieves immediate geometric fidelity, a prerequisite for guiding subsequent tissue formation along physiologically correct force lines. The true innovation of RootFab, however, lies in its capacity for closed-loop, adaptive behavior, orchestrated by embedded gene-activation systems and integrated biosensors. By arming the construct with a versatile toolkit of vector platforms, from transient modified mRNA for early cementogenic pulses near the root dentin to inducible plasmids for stabilizing ligament identity and localized viral modules for long-term trophic support, we can script the entire regenerative cascade in both space and time. This genetic program is not static; it is designed to be responsive. We have detailed how external, noninvasive triggers such as light, magnetic fields, and even the patient’s own masticatory forces can be used to switch specific gene circuits on or off through opto- or thermally gated CRISPR systems. This mechanogenetic potential is particularly profound, as it allows the construct to translate the language of functional loading directly into a biological response. An embedded piezoelectric mesh serves as a sentient layer, sensing microstrain from occlusion, which feeds into a control loop that can modulate thermal actuators or trigger gene expression. This effectively creates a feedback system where the developing tissue is continuously coached toward a state of optimal biomechanical integration, ensuring that the periodontium is not merely patched but truly taught to function. The path from this conceptual framework to clinical reality is grounded in a robust body of preclinical evidence and a clear-eyed view of translational requirements. We detail a manufacturing pipeline that incorporates real-time optical coherence tomography and vision-based path correction to stabilize printing on complex root geometries, ensuring fidelity. Genomic safety is anchored by unbiased off-target discovery methods, the use of high-fidelity paired Cas9 nickases, and a layered kill‒switch architecture to ensure predictable shutdown. Large-animal work anchors feasibility and sets expectations for cementum continuity, whereas finite element pipelines link the ligament modulus to realistic tooth kinematics. A first-in-human trial is envisioned with primary endpoints in clinical attachment gain, secondary endpoints in tooth mobility and survival, and comprehensive patient-reported outcomes to capture the functional benefits patients can feel. Ultimately, RootFab 4D BioWeave is a blueprint for a new class of regenerative medicine, one where engineered tissues are no longer passive implants but are instead living, adaptive systems that actively partner with the host to restore complex biological function through the coupling of spatial hierarchy to temporal control.

11. Unresolved Questions

While the RootFab framework presents an integrated strategy, its ambition exposes a new frontier of challenging questions that will define the next generation of regenerative medicine. What is the long-term epigenetic and metabolic fate of a gene-activated construct, and how does it coevolve with host aging and systemic disease, transforming the challenge from one of acute regeneration to one of chronic, multidecade symbiotic management? Furthermore, how does a living, immunomodulatory root surface reshape the subgingival microbiome over its lifespan, and could this unique biochemical niche inadvertently create a privileged environment for novel pathogenic consortia, for which we have no current therapeutic framework? Answering these profound long-term questions first requires solving critical, immediate engineering challenges. How can mechanogenetic circuits be calibrated to distinguish constructive cyclic microstrain from harmful peak loads in vivo, and can a two-channel controller combining strain-gated promoters with heat-triggered CRISPR switches preserve matrix quality over years? Can the piezoelectric strain signals from the scaffold surface be reliably mapped to subdegree thermal pulses within the ligament via genetically encoded temperature indicators, and what error budget is acceptable to avoid collateral damage to nascent tissues? Finally, how do we truly define durable success in humans? Is it a threshold of attachment gain, or must it include validated metrics of restored proprioception, such as normalized bite-force variability and restored trigeminal evoked potentials, that prove that we have not just rebuilt a structure but have successfully handed the brain a transparent sensory tool that it can trust and seamlessly integrate into function?

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not Applicable.

Declaration Regarding the Use of AI-Assisted Readability Enhancement

We hereby affirm that AI tools were used only for initial drafting to improve readability, grammar, language quality, and document organization. At no point did they replace authorial responsibilities or independent judgments. AI involvement was rigorously supervised under the discerning eye of human oversight and control. AI works within a closed corpus limited to the peer-reviewed sources cited, summarizing passages, proposing outlines, and suggesting draft phrasing with source tags. These suggestions served only as prompts. The authors reviewed every line, verified the text and citations, ensured that each retained statement mapped to a specific citation, and approved the final wording, analyses, and conclusions. No generative AI images or videos were used.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our sincere gratitude to Fatima Alzahraa Haider for her outstanding artistic contribution to this work. Her expertise and creativity in designing the graphical abstract greatly enhanced the visual impact and accessibility of our review. We deeply appreciate her dedication, attention to detail, and collaborative spirit throughout the process.

Conflicts of Interest

Not Applicable.

References

- Lai, J.; Liu, Y.; Lu, G.; Yung, P.; Wang, X.; Tuan, R. S.; Li, Z. A. 4D bioprinting of programmed dynamic tissues. Bioactive Materials 2024, 37, 348–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J.; Chen, H.; Luo, J.; Lin, S.; Yang, G.; Zhou, M.; Tao, J. Shape memory and hemostatic silk-laponite scaffold for alveolar bone regeneration after tooth extraction trauma. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 260, 129454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, B.; Dodda, J. M.; Wong, S. H. D.; Deen, G. R.; Bate, J. S.; Pachauri, A.; Tsai, S. W. Smart injectable hydrogels for periodontal regeneration: Recent advancements in biomaterials and biofabrication strategies. Materials Today, Bio 2025, 101855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S. H.; Kim, J.; Yang, H. J.; Lee, J. Y.; Kim, C. H.; Hur, J. K.; Park, S. B. CRISPR activation identifies a novel miR-2861 binding site that facilitates the osteogenesis of human mesenchymal stem cells. Journal of orthopedic surgery and research 2024, 19(1), 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, E.; Tay, J. R. H. Periodontal Regeneration of Vital Poor Prognosis Teeth with Attachment Loss Involving the Root Apex: Two Cases with up to 5 Years Follow-Up. Dentistry Journal 2024, 12(6), 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]