Submitted:

12 September 2025

Posted:

15 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

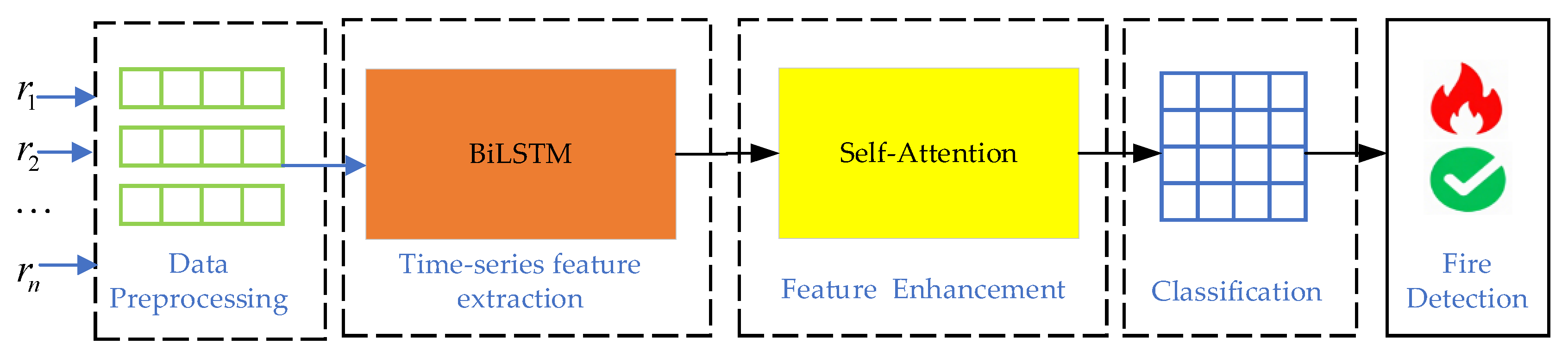

2. The Proposed Method

2.1. Data Preprocessing Module

- (1)

- Normalization;

- (2)

- Time-Series Data Generation;

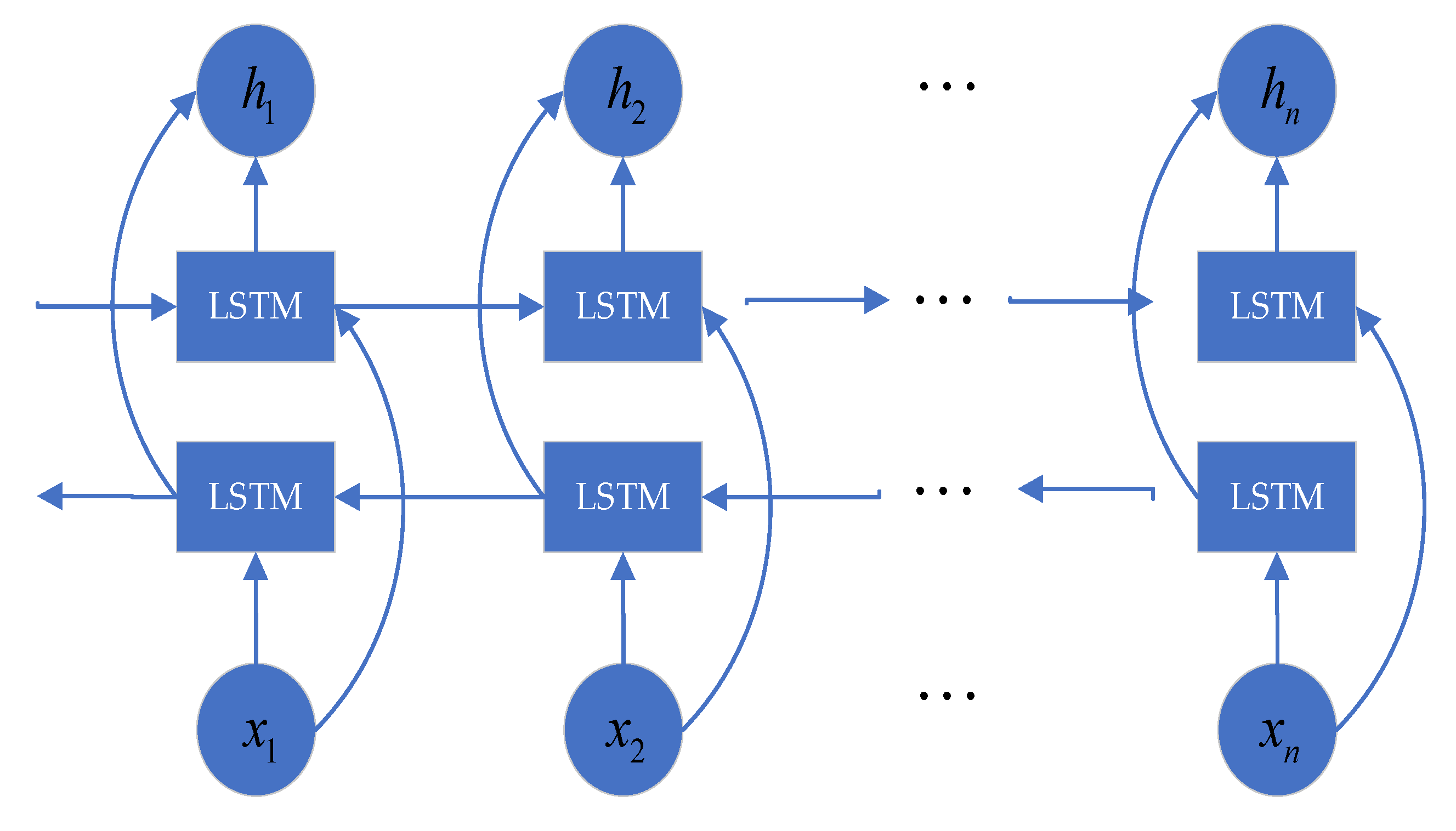

2.2. Time-Series Feature Extraction Module

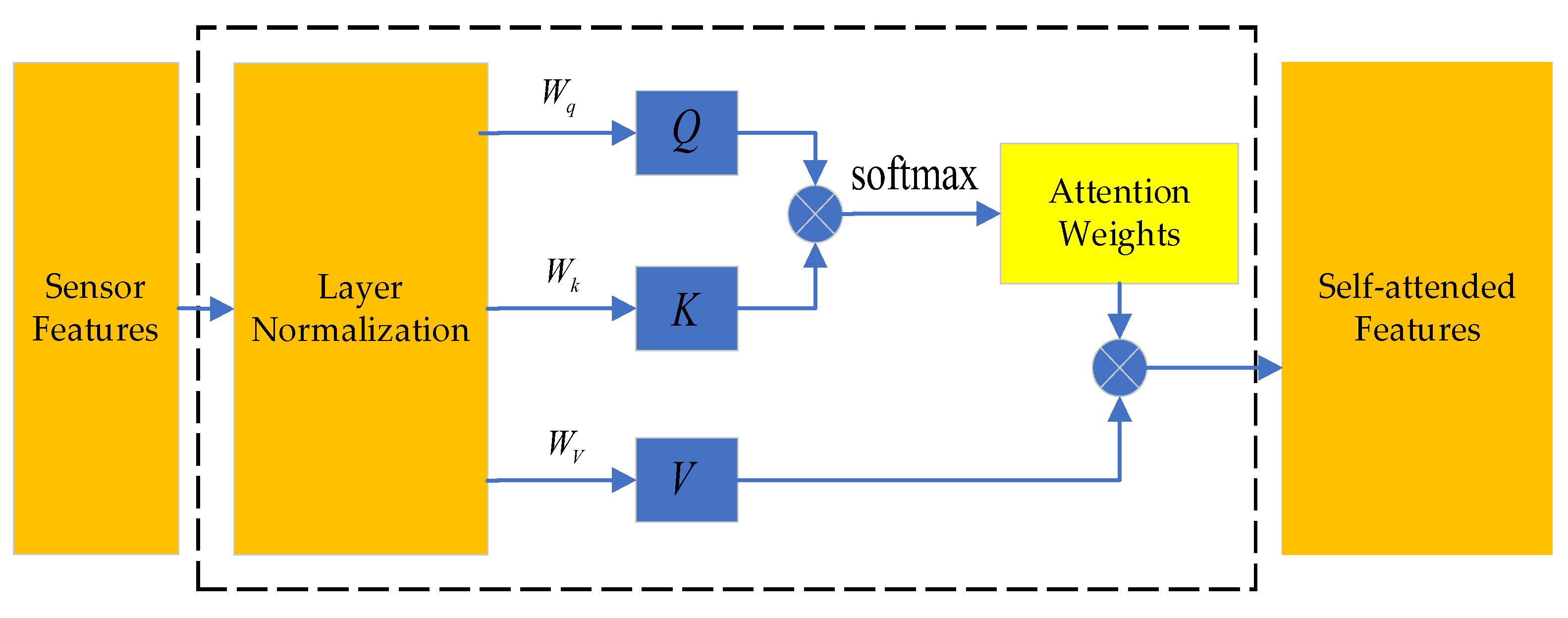

2.3. Feature Enhancement Module

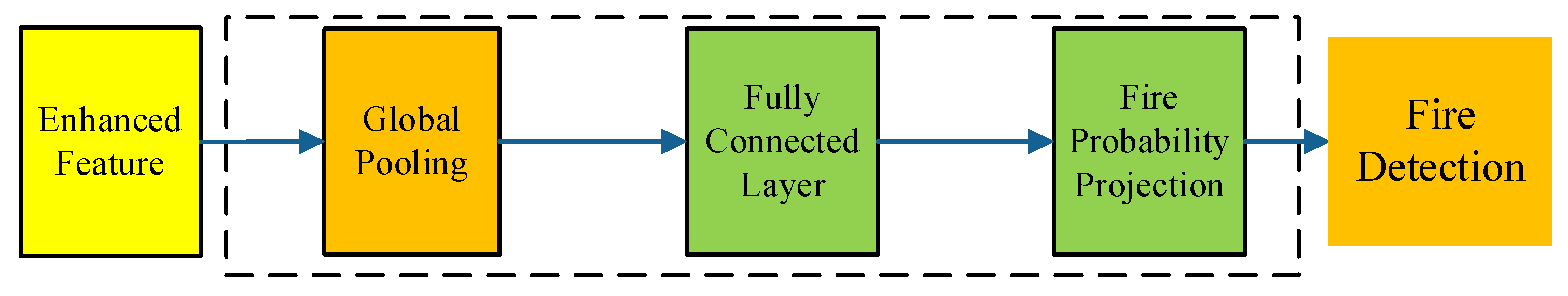

2.4. Classification Module

- (1)

- Global Average Pooling

- (2)

- Classification Head

3. Experiments

3.1. Datasets and Experiment Preparation

- Normal indoor conditions

- Normal outdoor conditions

- Indoor wood fire within a firefighter training area

- Indoor gas fire within a firefighter training area

- Outdoor wood, coal, and gas grill fires

- High-humidity outdoor environments

- B denotes the batch size, set to 32, indicating the number of samples processed in each batch;

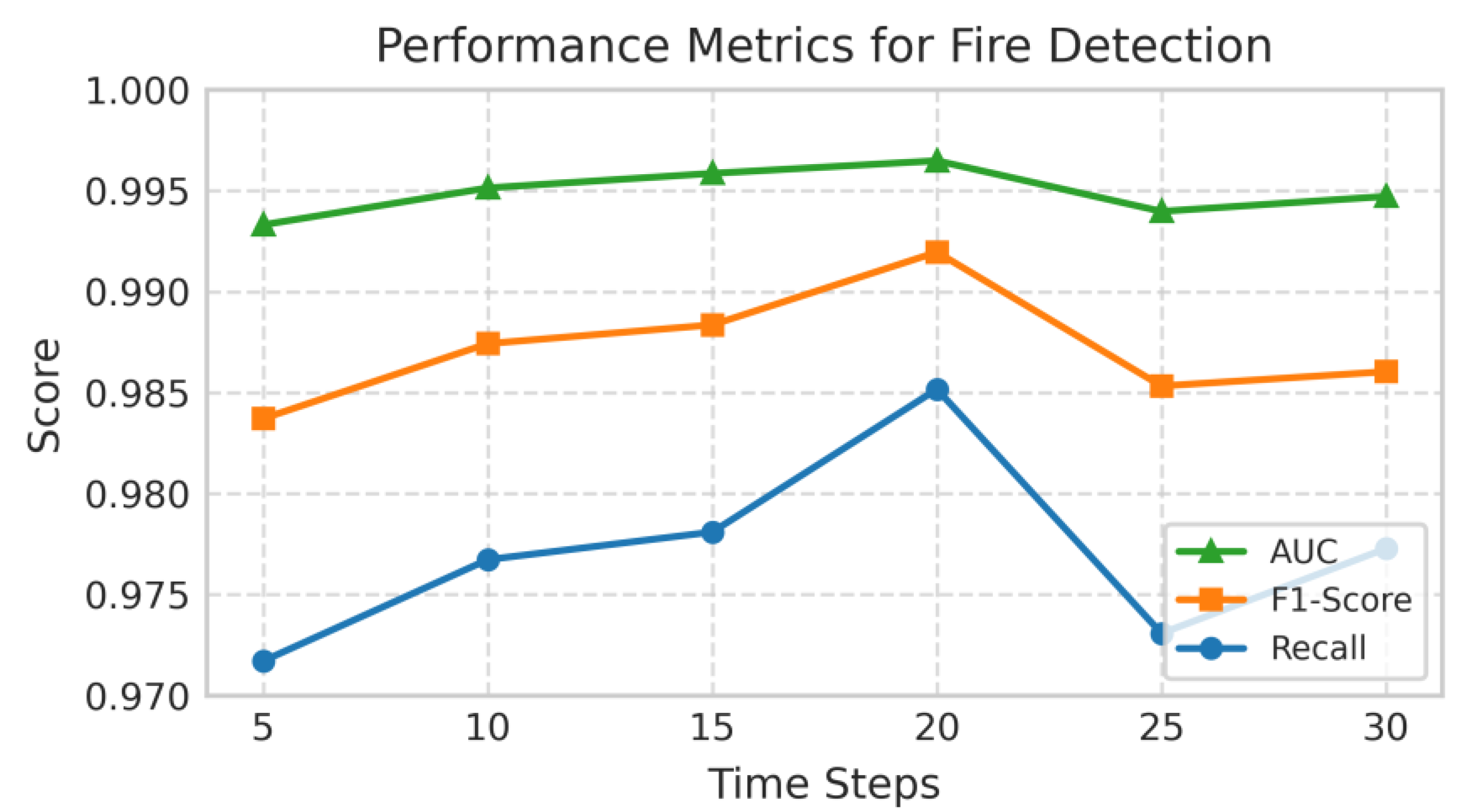

- T indicates the number of time steps, which is set to 20, corresponding to the length of consecutive sensor readings per sample;

- N represents the number of sensors (or sensor channels), which is set to 4 in this study.

3.2. Experimental Results Analysis

3.2.1. Metrics of Accuracy

3.2.2. Metrics of Confusion Matrix

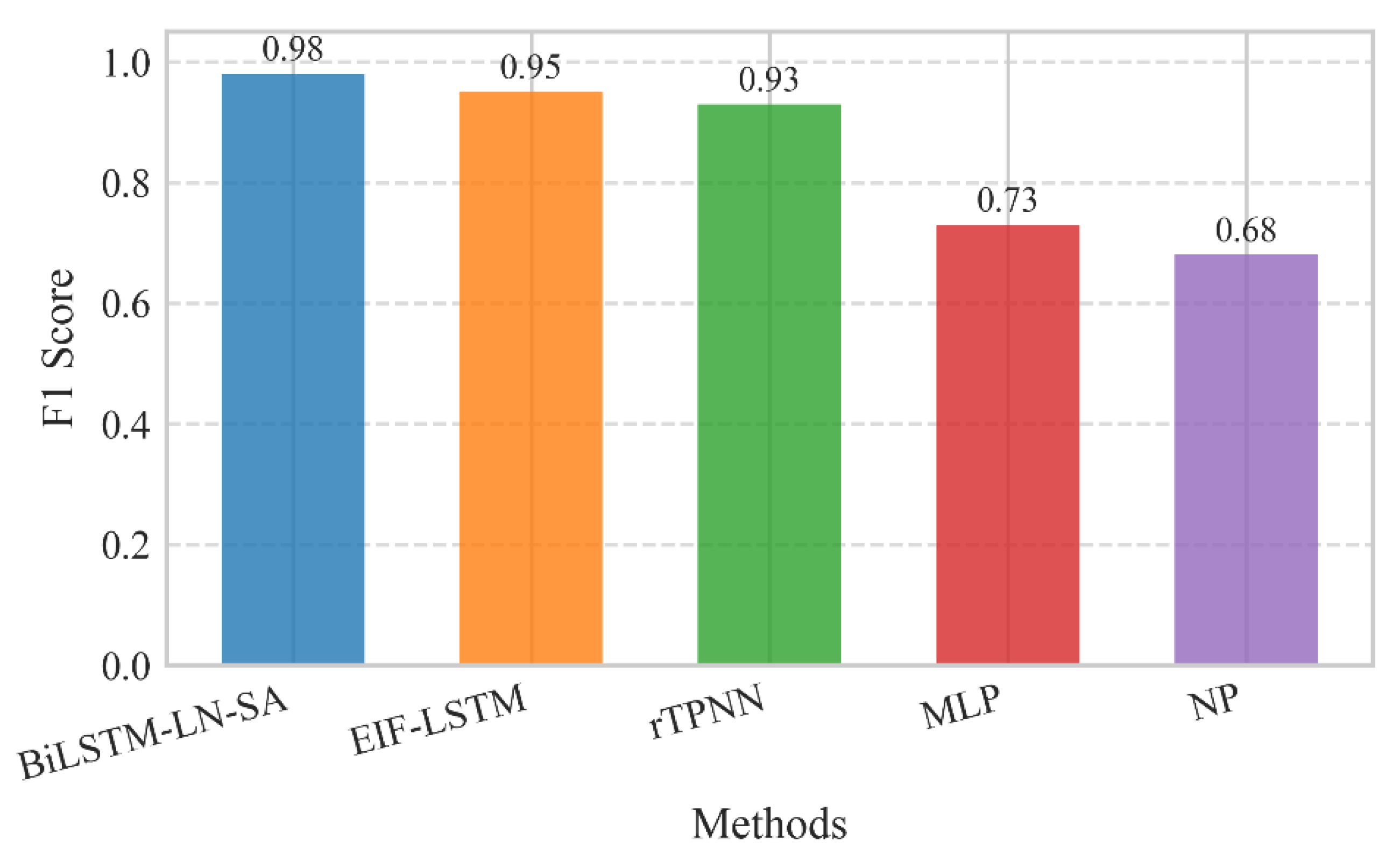

3.2.3. Metrics of F1-Score

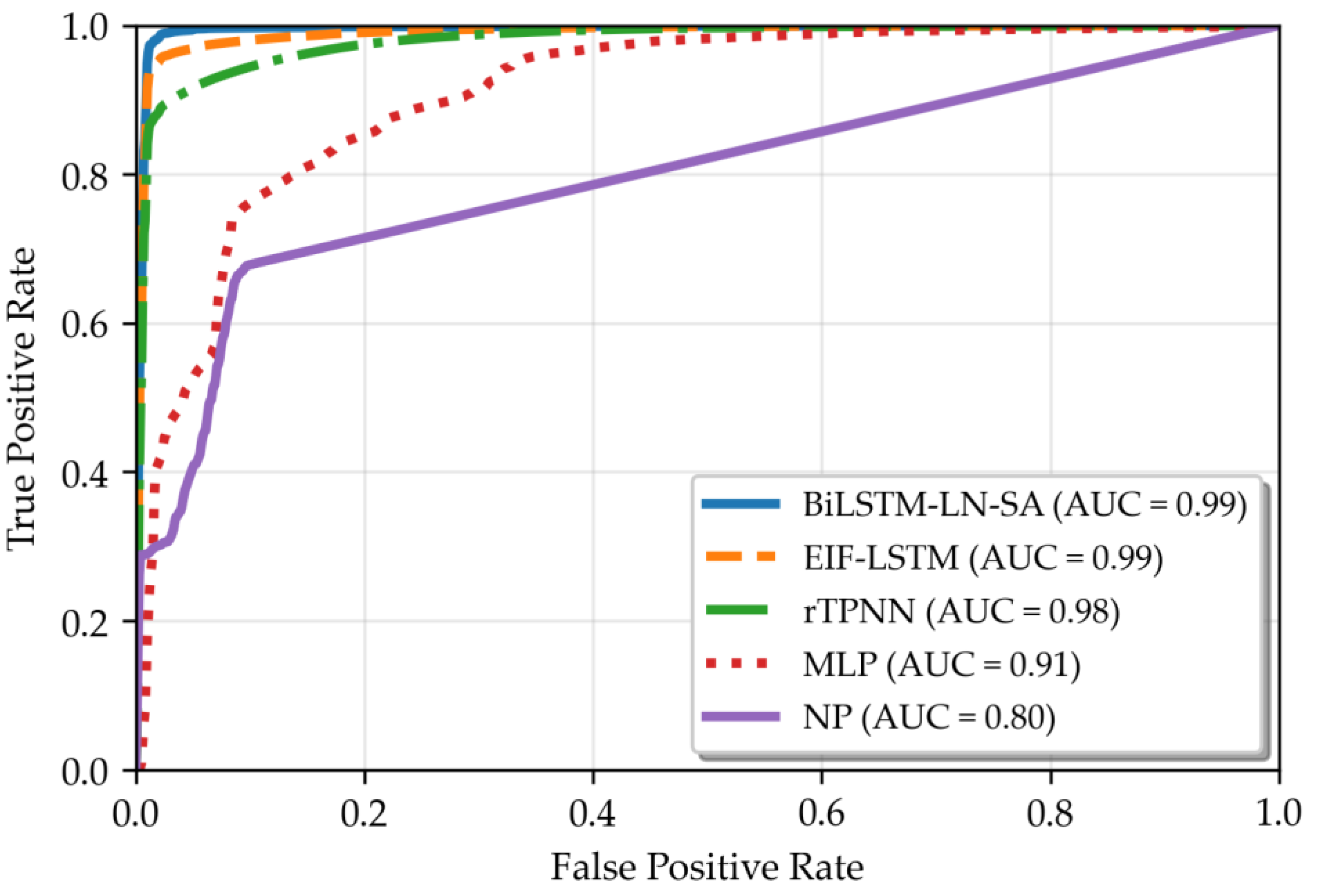

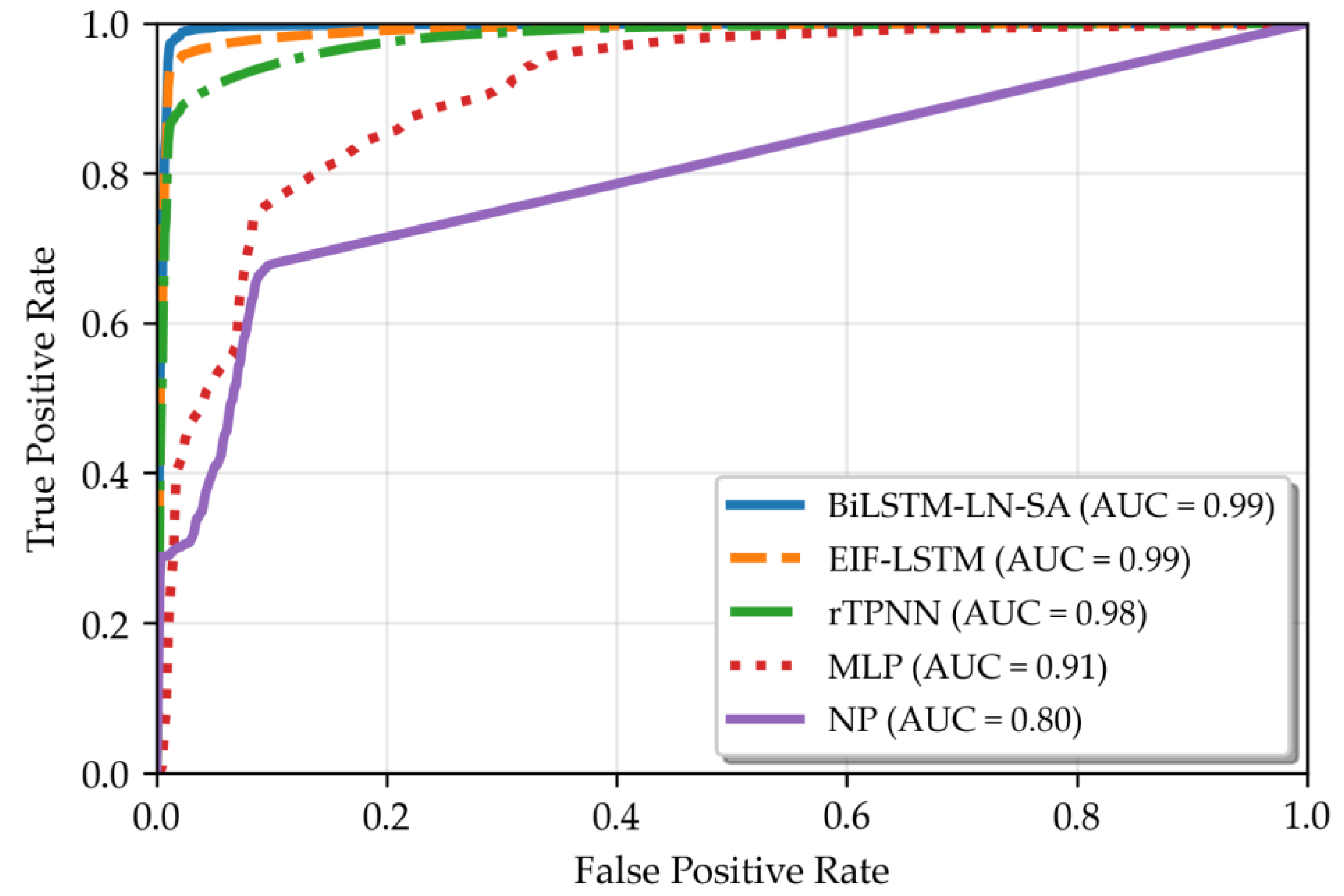

3.2.4. Metrics of ROC Curve

3.2.5. Analysis of the Relationship Between Step Size and Performance in Fire Detection Systems

3.2.6. Ablation Study: The Impact of Layer Normalization

4. Conclusions

Funding

References

- Nakip, M.; Guzelis, C. Development of a Multi-Sensor Fire Detector Based On Machine Learning Models. 2019 Innovations in Intelligent Systems and Applications Conference (ASYU) 2019, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Festag, S. False alarm ratio of fire detection and fire alarm systems in Germany – A meta analysis. Fire Safety Journal 2016, 79, 119-126. [CrossRef]

- Hangauer, A.; Chen, J.; Strzoda, R.; Fleischer, M.; Amann, M.C. Performance of a fire detector based on a compact laser spectroscopic carbon monoxide sensor. Optics Express 2014, 22, 13680. [CrossRef]

- Baek, J.; Alhindi, T.J.; Jeong, Y.-S.; Jeong, M.K.; Seo, S.; Kang, J.; Shim, W.; Heo, Y. A Wavelet-Based Real-Time Fire Detection with Multi-Modeling Framework. SSRN Electronic Journal 2023. [CrossRef]

- Fonollosa, J.; Solórzano, A.; Marco, S. Chemical Sensor Systems and Associated Algorithms for Fire Detection: A Review. Sensors 2018, 18, 553. [CrossRef]

- Solórzano, A.; Eichmann, J.; Fernández, L.; Ziems, B.; Jiménez-Soto, J.M.; Marco, S.; Fonollosa, J. Early fire detection based on gas sensor arrays: Multivariate calibration and validation. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2022, 352, 130961. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zheng, C.; Ma, Z.; Yang, S.; Zheng, K.; Song, F.; Ye, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Development of a Mid-Infrared Sensor System for Early Fire Identification in Cotton Harvesting Operation. SSRN Electronic Journal 2022. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-J.; Hovde, D.C.; Peterson, K.A.; Marshall, A.W. Fire detection using smoke and gas sensors. Fire Safety Journal 2007, 42, 507-515. [CrossRef]

- Baek, J.; Alhindi, T.J.; Jeong, Y.-S.; Jeong, M.K.; Seo, S.; Kang, J.; Heo, Y. Intelligent Multi-Sensor Detection System for Monitoring Indoor Building Fires. IEEE Sensors Journal 2021, 21, 27982-27992. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q. Application Research and Improvement of Weighted Information Fusion Algorithm and Kalman Filtering Fusion Algorithm in Multi-sensor Data Fusion Technology. Sensing and Imaging 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Deng, Z.; Hu, E. Multi-Sensor Fusion Positioning Method Based on Batch Inverse Covariance Intersection and IMM. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 4908. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Li, Y.; Sun, H.; Yang, K. Multisensor-Weighted Fusion Algorithm Based on Improved AHP for Aircraft Fire Detection. Complexity 2021, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Jing, C.; Jingqi, F. Fire Alarm System Based on Multi-Sensor Bayes Network. Procedia Engineering 2012, 29, 2551-2555. [CrossRef]

- Ran, M.; Bai, X.; Xin, F.; Xiang, Y. Research on Probability Statistics Method for Multi-sensor Data Fusion. 2018 International Conference on Cyber-Enabled Distributed Computing and Knowledge Discovery (CyberC) 2018, 406-4065. [CrossRef]

- Jana, S.; Shome, S.K. Hybrid Ensemble Based Machine Learning for Smart Building Fire Detection Using Multi Modal Sensor Data. Fire Technology 2022, 59, 473-496. [CrossRef]

- Baek, J.; Alhindi, T.J.; Jeong, Y.-S.; Jeong, M.K.; Seo, S.; Kang, J.; Choi, J.; Chung, H. Real-Time Fire Detection Algorithm Based on Support Vector Machine with Dynamic Time Warping Kernel Function. Fire Technology 2021, 57, 2929-2953. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Peng, Z.; Liu, T.; Tong, Q. Multi-Sensor Building Fire Alarm System with Information Fusion Technology Based on D-S Evidence Theory. Algorithms 2014, 7, 523-537. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y. Fire detection system based on improved multi-sensor information fusion. Fifth International Conference on Computer Information Science and Artificial Intelligence (CISAI 2022) 2023, 71. [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Yao, W.; Dai, X.; Jia, R. A New Evidence Weight Combination and Probability Allocation Method in Multi-Sensor Data Fusion. Sensors 2023, 23, 722. [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Hu, G.; Liu, Z. Research on fire detection method of complex space based on multi-sensor data fusion. Measurement Science and Technology 2024, 35, 85107. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Liu, Y.; Fang, W.; Jia, G.; Qiu, Y. Fire Detection Scheme in Tunnels Based on Multi-source Information Fusion. 2022 18th International Conference on Mobility, Sensing and Networking (MSN) 2022, 1025-1030. [CrossRef]

- Sowah, R.A.; Ofoli, A.R.; Krakani, S.N.; Fiawoo, S.Y. Hardware Design and Web-Based Communication Modules of a Real-Time Multisensor Fire Detection and Notification System Using Fuzzy Logic. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 2017, 53, 559-566. [CrossRef]

- Hong Bao, u.; Jun Li, u.; Xian-Yun Zeng, u.; Jing Zhang, u. A fire detection system based on intelligent data fusion technology. Proceedings of the 2003 International Conference on Machine Learning and Cybernetics (IEEE Cat. No.03EX693), 1096-1101. [CrossRef]

- Rachman, F.Z.; Hendrantoro, G.; Wirawan. A Fire Detection System Using Multi-Sensor Networks Based on Fuzzy Logic in Indoor Scenarios. In Proceedings of the 2020 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technology (ICoICT), 2020/06/24/26, 2020; pp. 1-6.

- Wang Xihuai, u.; Xiao Jianmei, u.; Bao Minzhong, u. Multi-sensor fire detection algorithm for ship fire alarm system using neural fuzzy network. WCC 2000 - ICSP 2000. 2000 5th International Conference on Signal Processing Proceedings. 16th World Computer Congress 2000 3, 1602-1605. [CrossRef]

- Qu, W.; Tang, J.; Niu, W. Research on Fire Detection Based on Multi-source Sensor Data Fusion. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing 2020, 629-635. [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Chen, L.; Hao, X. Multi-Sensor Data Fusion Algorithm for Indoor Fire Early Warning Based on BP Neural Network. Information 2021, 12, 59. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.L. Research of Multi-Sensor Information Fusion Fire Detection System. Advanced Materials Research 2013, 2745-2749. [CrossRef]

- Wen, M. Time Series Analysis of Receipt of Fire Alarms Based on Seasonal Adjustment Method. In Proceedings of the 2016 8th International Conference on Intelligent Human-Machine Systems and Cybernetics (IHMSC), 2016/08/27/28, 2016; pp. 81-84.

- Ryder, N.L.; Geiman, J.A.; Weckman, E.J. Hierarchical Temporal Memory Continuous Learning Algorithms for Fire State Determination. Fire Technology 2021, 57, 2905-2928. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Su, Y.; Zeng, X.; Wang, J. Research on Multi-Sensor Fusion Indoor Fire Perception Algorithm Based on Improved TCN. Sensors 2022, 22, 4550. [CrossRef]

- Nakip, M.; Guzelis, C.; Yildiz, O. Recurrent Trend Predictive Neural Network for Multi-Sensor Fire Detection. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 84204-84216. [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Xiang, P.; Lu, D. A new multi-sensor fire detection method based on LSTM networks with environmental information fusion. Neural Comput & Applic 2023, 35, 25275-25289. [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Shi, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, Q.; Bao, J.; Chen, Z. An Indoor Fire Detection Method Based on Multi-Sensor Fusion and a Lightweight Convolutional Neural Network. Sensors 2023, 23, 9689. [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Guo, T. Evidential reasoning and lightweight multi-source heterogeneous data fusion-driven fire danger level dynamic assessment technique. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2024, 185, 350-366. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ye, M.; Deng, X. A novel anomaly detection method for multimodal WSN data flow via a dynamic graph neural network. Connection Science 2022, 34, 1609-1637. [CrossRef]

- Stefan, B. ai sensor fusion for fire detection. 2022. :https://github.com/Blatts01.

| Methods | Training | Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std | Mean | Std | |

| BiLSTM-LN-SA | 98.50 | 0.31 | 98.38 | 0.38 |

| EIF-LSTM | 96.15 | 0.41 | 95.30 | 0.49 |

| rTPNN | 94.10 | 2.32 | 93.85 | 2.16 |

| MLP | 87.95 | 2.02 | 88.27 | 2.41 |

| NP | 80.05 | 1.21 | 80.12 | 1.26 |

| Sensor Type | Training | Test | ||

| Mean | Std | Mean | Std | |

| Temperature | 50.62 | 2.26 | 50.52 | 2.29 |

| TVOC | 85.89 | 0.91 | 85.75 | 0.80 |

| Carbon dioxide | 79.30 | 2.32 | 79.25 | 2.28 |

| NC2.5 | 84.95 | 1.36 | 84.72 | 1.30 |

| Methods | TPR | FNR | TNR | FPR |

| BiLSTM-LN-SA | 98.15 | 1.85 | 98.50 | 1.50 |

| EIF-LSTM | 95.20 | 4.80 | 96.90 | 3.10 |

| rTPNN | 91.27 | 8.73 | 95.27 | 4.73 |

| MLP | 85.27 | 14.73 | 91.27 | 8.73 |

| NP | 75.05 | 25.95 | 81.25 | 18.75 |

| Sensor Type | TPR | FNR | TNR | FPR |

| Temperature | 28.30 | 71.70 | 98.55 | 1.45 |

| TVOC | 85.40 | 14.60 | 99.10 | 0.90 |

| Carbon dioxide | 52.30 | 47.70 | 96.80 | 3.20 |

| NC2.5 | 82.90 | 17.10 | 98.71 | 1.29 |

| Methods | TPR | FNR | TNR | FPR |

| BiLSTM-LN-SA | 98.15 | 1.85 | 98.50 | 1.50 |

| BiLSTM-SA | 95.80 | 3.20 | 95.20 | 4.80 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).