Submitted:

12 September 2025

Posted:

16 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Problem Formulation

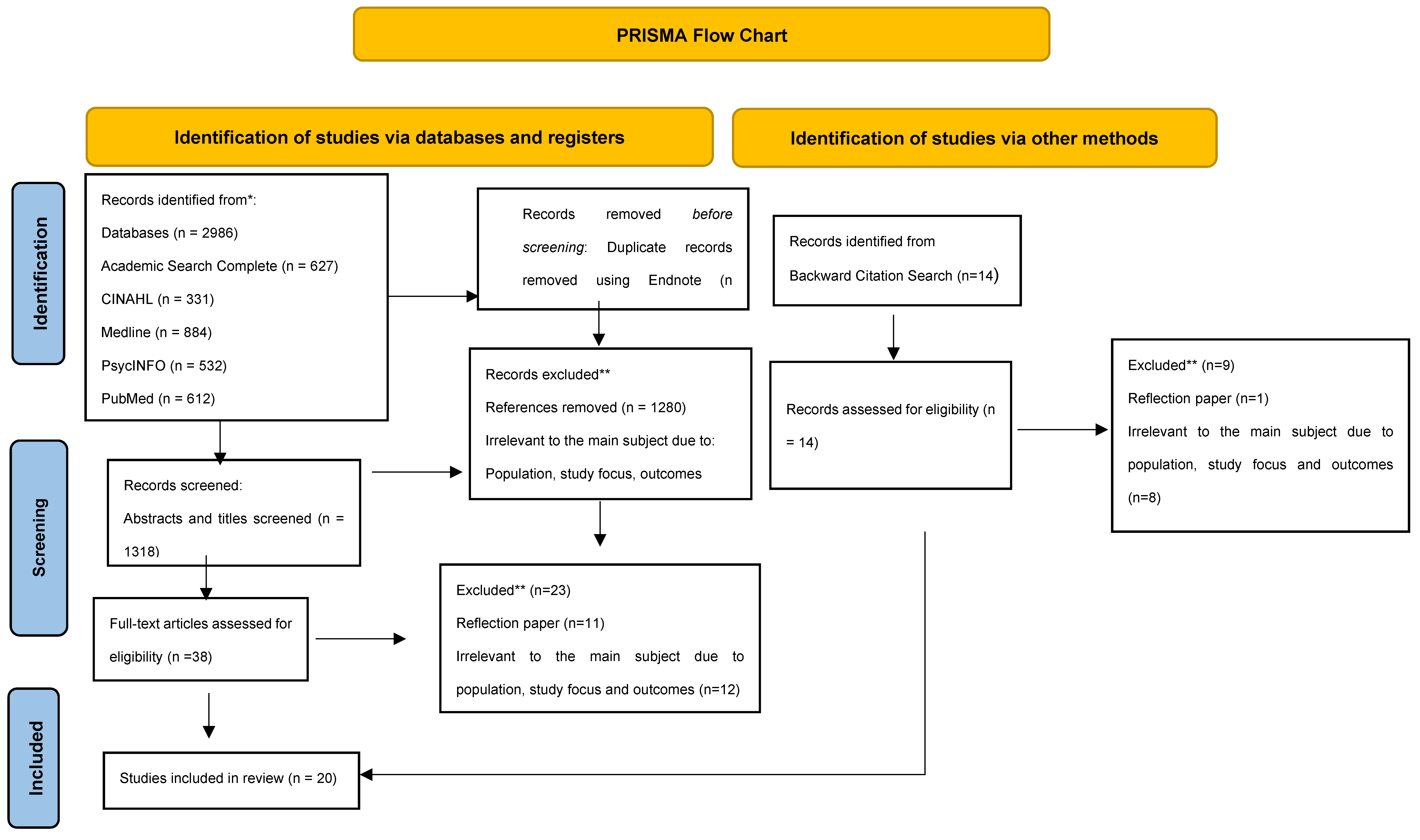

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Perspectives

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Literature Search Stage

2.4. Data Extraction and Quality Appraisal

2.5. Data Analysis

| Search terms | Database | Citations |

|---|---|---|

| aging or ageing or elderly or older adults or seniors or geriatrics or gerontology) AND (Nigeria or Nigeria, Eastern or Nigeria, Western or Nigeria, Eastern or Nigeria, Southern or Nigeria, Northern or Nigerian, Overseas, Nigerian, abroad) AND ( Care or caregiv* or support ) | Academic Search Complete (Ebsco) | 627 |

| "( aging or ageing or elderly or older adults or seniors or geriatrics or gerontology ) AND ( Nigeria or Nigeria, Eastern or Nigeria, Western or Nigeria, Eastern or Nigeria, Southern or Nigeria, Northern or Nigerian, Overseas, Nigerian, abroad ) AND ( Care or caregiv* or support )" OR (MH "Nigeria") OR (MH "Eldercare") | CINAHL (Ebsco) | 331 |

| "( aging or ageing or elderly or older adults or seniors or geriatrics or gerontology ) AND ( Nigeria or Nigeria, Eastern or Nigeria, Western or Nigeria, Eastern or Nigeria, Southern or Nigeria, Northern or Nigerian, Overseas, Nigerian, abroad ) AND ( Care or caregiv* or support )" OR (MH "Nigeria") OR (MH "Eldercare") | PsychINFO (Ebsco) | 532 |

| aging or ageing or elderly or older adults or seniors or geriatrics or gerontology) AND (Nigeria or Nigeria, Eastern or Nigeria, Western or Nigeria, Eastern or Nigeria, Southern or Nigeria, Northern or Nigerian, Overseas, Nigerian, abroad) AND ( Care or caregiv* or support ) | PubMed (Medline) | 612 |

| aging or ageing or elderly or older adults or seniors or geriatrics or gerontology) AND (Nigeria or Nigeria, Eastern or Nigeria, Western or Nigeria, Eastern or Nigeria, Southern or Nigeria, Northern or Nigerian, Overseas, Nigerian, abroad) AND ( Care or caregiv* or support ) | Medline (OVID) | 884 |

| Total retrieved | 2,986 |

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Themes and Sub-themes

3.3. Cultural Influences

3.4. Gender Differences

3.5. Family Dynamics

3.6. Economic Factors

3.7. Challenges Faced by Nigerian Caregivers

3.8. Government Policies and Support

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Policy Makers, Practitioners, and Researchers

4.2. Key Recommendations

- Develop comprehensive support systems: Government agencies should prioritize the development of comprehensive support systems that address the challenges faced by caregivers, including conflicting responsibilities, limited healthcare access, and a lack of formal support. This can be achieved through the implementation of policies that provide financial assistance, improve healthcare accessibility, and establish caregiver support programs.

- Strengthen community-based initiatives: Community organizations and stakeholders should collaborate to establish and strengthen community-based initiatives that provide support to caregivers. This can include caregiver support groups, respite care services, and educational programs that equip caregivers with necessary skills and knowledge.

- Promote cultural shifts: Efforts should be made to challenge traditional gender roles and expectations associated with caregiving. This can be achieved through awareness campaigns, educational programs, and advocacy to promote equal distribution of caregiving responsibilities among family members.

- Foster intergenerational relationships: Encourage intergenerational relationships and activities that involve both elderly individuals and younger generations. This can help create a supportive environment where elderly individuals receive care and companionship while younger generations gain valuable knowledge and experience in caregiving.

- Conduct further research: Future research should expand beyond Nigeria and explore the experiences of Nigerian immigrants in transnational intergenerational caregiving. This will provide insights into the unique challenges and dynamics faced by caregivers in diaspora communities and inform the development of targeted interventions and support systems.

- Advocate for policy changes: Researchers, practitioners, and policymakers should collaborate to advocate for policy changes that prioritize elder caregiving, address the identified challenges, and improve the overall well-being of caregivers and elderly individuals. This can include lobbying for increased funding, policy reforms, and the inclusion of caregiver support in national health and social care agendas.

5. Conclusions

Informed Consent Statements

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Author/JournaAuthor/Journal DATT |

Sample/Population | Objectives | Methodology/Study Design | Data Collection Methods | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Akinrolie et al. Gerontological Social Work 2020 |

18 participants; 10 elderly individuals and 8 adult children in Abuja | To explore the perception of reciprocity between older parents and adult children on intergenerational support in Northern Nigeria | Qualitative | Interviews |

Cultural Influences: -Rapid modernization in developing countries had negative effects, according to elderly individuals. Family Dynamics: -Support was seen as a continuous process throughout life, flowing in multiple directions. -Some participants relocated their parents from rural areas, assuming responsibility for their needs and medical expenses. -Elderly individuals categorized support into material, monetary, and physical assistance. Economic Factors: -Elderly individuals perceived a decline in support received, attributing it to the country's deteriorating economic situation.\ -Monetary support from adult children was emphasized, while emotional support was less emphasized. Challenges for Caregivers: -Types of support received were influenced by adult children's busy schedules and limited availability. |

|

Ani & Isiugo-Abani International Journal of Sociology of the Family 2017 |

444respondents aged 65 years and above from selected Local Government Areas of Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria | To explore the conditions of the elderly in Ibadan Nigeria. | Mixed methods | Questionnaires and Interviews |

Cultural Influences: -Rapid modernization in developing countries had negative effects, according to elderly individuals. Family Dynamics: -Elderly individuals with larger families had the expectation of receiving support in old age. Economic Factors: -Some elderly individuals relied on pensions. -66.4% of respondents aged 65 and above continued working to compensate for inadequate care from children. -Support received was often inadequate, leading to heavy reliance on children despite limitations. -Variables such as education, residence, number of children, and income were associated with receiving adequate care. -Urban elders were twice as likely to receive adequate care compared to rural elders. Government Policies and Support: -The absence of government social security programs led to the expectation of children as primary providers of care |

|

Animasahun & Chapman African Health Sciences 2017 |

Studies done between 2000 and 2015 | To examine the driving factors for the psychosocial health challenges among the elderly in Nigeria | Narrative Review |

Family Dynamics: -Family provides up to 90% of home care, leading to caregiver stress and health risks. -Materialism and abandonment are replacing Nigerian family values, resulting in insecurity and increased abuse or neglect of the elderly. -Economic pressures cause family members to migrate to urban areas, impacting the traditional extended family structure. Gender Differences: -Gender imbalance affects social support, with older women facing more challenges and domestic violence. -Women are financially under-resourced and experience more psychosocial health challenges in older age compared to men. Government Policies and Support: -Geriatric medical services are not prioritized, leading to lengthy waiting times, low provider-patient ratios, and poor communication. |

|

|

Ebimgbo et al. Indian Journal of Gerontology 2019 |

40 caregivers aged 23 and above living in Nnewi, south-east Nigeria | To gain understanding on challenges of caregiving to elderly individuals | Qualitative | Focus group discussions |

Challenges for Caregivers: -Participants experienced stress while caring for elderly individuals. -Family caregivers had limited time for themselves and their own families due to the demands of caregiving. Economic Factors: -Participants spent significant amounts of money on food and drugs for elderly individuals. |

|

Ebimgbo & Okoye Nigerian Journal of Social Sciences 2017 |

528 elderly individuals in Nnewi, Southeast, Nigeria | To ascertain the factors that predict availability of social support whenever it is needed by elderly individuals | Quantitative study | Questionnaires |

Family Dynamics: -Factors such as financial status, attitudes of children, and health status were substantial in predicting the receipt of social support by elderly individuals. -Family networks, including children, provide the most support to elderly individuals, followed by other networks such as churches, government and NGOs, community, and friends. -The attitudes of support networks, particularly adult children, influence the receipt of social support by elderly individuals. -Better relationships between elderly individuals and their caregivers, particularly their children, result in more supportive interactions. Government Policies and Support: -Elderly individuals with low financial backgrounds are less likely to receive social support when needed. -Most respondents (64.6%) reported that the social support they received was inadequate or unsatisfactory. -Healthy elderly individuals are more likely to receive social support when needed compared to those with deteriorated health conditions. |

|

Ebimgbo et al. Community, Work & Family 2022 |

24 elderly individuals aged 80 years or older and 16 caregivers -ages of 30 and 46 years (n = 40). | To ascertain the extent to which elderly individuals receive support from the family and community networks | Qualitative |

Focus group discussions and In-depth Interviews |

Cultural Influences: -Family ties are gradually disintegrating. Family Dynamics: -Elderly individuals primarily receive financial support from their families, as indicated by most participants. -Family networks provide more health support to elderly individuals compared to the community. -Familial networks offer a greater range of social support, including financial, material, health, and instrumental support, compared to the community. -Support provided by families is often inadequate due to competing responsibilities and priorities. Gender Differences: -Caregivers in the study are predominantly educated, with women more likely to prioritize education over caregiving responsibilities. Government Policies and Support: -Participants recognized the need for non-family members to assist elderly individuals. |

|

Ebimgbo & Okoye. Journal of Population Ageing 2022 |

58 left-behind elderly individuals in Abia, Anambra, Ebonyi, Enugu, and Imo. |

To examine the challenges of left-behind older family members of international migrants in south-east Nigeria. | Qualitative | In-depth Interviews and Focus Group Discussions |

Family Dynamics: -Elderly individuals who are left behind may resort to unhealthy coping mechanism in the absence of their children. -Loneliness and lack of assistance from migrating young family members impede support for IADLs among left-behind elderly individuals, impacting their ADL performance. Cultural Influences: -The migration of younger family members disrupts traditional care and support for elderly individuals, leading to neglect. |

|

Eboiyehi & Onwuzuruigbo Journal of Sociology and Anthropology 2014 |

32 IDIs and 8 FGDs were conducted among men and women aged 60 years and above. |

To examine the nature of care and support system for the aged and the coping strategies among the Esan of South-South Nigeria | Qualitative | In-depth Interviews and Focus Group Discussions |

Family Dynamics: -Extended family ties are diminishing, leading to increased social distance between aged parents and adult children. -Age-selective rural-urban migration and the emergence of nuclear family structures have negatively impacted the care and support provided for the elderly. -Intergenerational changes in care and support for the aged are influenced by factors such as out-migration, unemployment, Westernization, and industrialization. Gender Differences: -Aged men employ coping strategies such as subsistence farming, contributions, support from offspring, pension income, support from social service providers, and menial jobs. -Aged women employ coping strategies such as petty trading, farming, support from social service providers, and alms begging. Cultural Influences and Economic Factors -Old age in the Esan community is perceived based on societal notions of purity and virtuous living. -Traditional Esan society operates on intergenerational exchanges of wealth and care |

|

Fajemilehin Africa Journal of Nursing and Midwifery |

150 elderly aged 70 years and above and their primary support providers in Ife/ljesa zone, Osun state, Southwestern Nigeria. |

To document the experiences of caregiving against the background of socio cultural and economic change | Mixed methods | Open ended questionnaires and in-depth interviews |

Cultural Influences and Economic Factors: -Westernization and education lead to rural-urban migration of children, resulting in a lack of care for the elderly. -The collapse of the traditional extended family system has diminished closeness and social support within the family. -Cultural practices of relying on maids or houseboys for elderly care have diminished. -Female elderly relatives live with married children to provide assistance, guidance, counseling, and support for the younger generation. |

|

Iwuagwu, Ngwu & Ekoh Journal of Population Ageing 2022 |

14 elderly individuals who were caregivers of their very old parents | To explore the challenges of female elderly individuals caring for their very old parents in rural Southeast Nigeria. |

Qualitative (Descriptive) | Interviews |

Challenges for Caregivers: -Caregivers experience psychological burden because of caring for their very old parents and the inability to speak up or complain increases the psychological burden. -Social burden due to marital conflict, sibling conflict, inadequate caregiving support from male children. -Caregivers experienced physical health burden. Gender Differences: -The caregiving responsibilities predominantly shouldered by older women contribute to the participants' financial hardships as they reported experiencing financial constraints. |

|

Iwuagwu, Ugwu, Ugwuanyi et al. African Journal of Social work. 2022 |

195 respondents with experience of caregiving in Enugu State | To investigate the family caregivers' awareness and perceived access to formal support care services available for elderly individuals in Enugu State, Nigeria. | Quantitative | Questionnaires |

Government Policies and Support: -Majority of respondents are aware of formal support care services for elderly individuals. -Lack of support care services negatively impacts elderly individuals. -Elderly individuals face challenges in accessing formal support care services. Economic Factors: -Financial constraints, lack of awareness, and lack of social support affect access to formal supports. -Place of residence can be a barrier or facilitator for accessing formal support care services. Gender Differences: -Gender is not an important factor in predicting access to support care services for elderly individuals. Challenges for Caregivers: -Education level is a considerable factor in predicting access to formal support care services. |

|

Mayston et al. PloS one 2017 |

Multiple family members in Peru, Mexico, China & Nigeria 60 interviews in 24 households |

To explore the social and economic effects of caring for an older dependent person, including insight into pathways to economic vulnerability. | Mixed methods (Quantitative & Qualitative) | In-depth narrative style interviews |

Government Policies and Support: -Governments were largely uninvolved in the care and support of older dependent people. Gender Differences: -In most households, women were the de facto main caregivers. -In some instances, a non-family caregiver was paid to provide care. Economic Factors: -Severe economic hardship, where households struggled to meet the costs of food and healthcare, was most common in the Nigerian case studies. -Seven households described limiting food, other household consumption, or access to healthcare because of a lack of funds. -Caregiving responsibilities and filial duty decreased earning potential and curtailed career development. |

|

Namadi Journal of Applied, Management and Social Sciences 2016 |

100 family caregivers and 100 elderly care recipients in Kano, Nigeria | To examine the interaction patterns and perceived care satisfaction among the family caregivers and the elderly care recipients in Kano | Mixed methods (Quantitative & Qualitative) | Questionnaires (quantitative) and in-depth interviews (qualitative) |

Family Dynamics: -Reciprocity and obligation are key factors motivating family caregivers to provide continuous care to older family members. Gender Differences: -Females tend to experience chronic ailments at an earlier age compared to males. -Daughters-in-law and sons/daughters are the primary caregivers for critically ill older family members. -Family caregiving is predominantly carried out by females, with women comprising 60% of caregivers. -Daughters-in-law often report lower satisfaction with caregiving roles compared to other family members. Challenges for Caregivers: -Many care recipients have multiple health issues in addition to their primary condition. -Caregivers generally report a moderate level of satisfaction as perceived by the care recipients. -Elderly care recipients prefer to have opportunities for self-care and do not want to be a burden to their family members. -Many of family caregivers have secondary or primary level education, with fewer having tertiary education. |

|

Odaman & Ibiezugbe IFE PsychologIA: An International Journal 2014 |

514 respondents were selected from homes with elderly persons, ages 65+ years, and living in them in Edo state | To investigate fo of social and economic remittances from relatives to the elderly Edo people. | Quantitative | Questionnaires |

Economic Factors: -Socioeconomic remittances from relatives to the elderly are at a poor level. -Urbanization, industrialization, and modernization have led to the disintegration of extended families, leaving the elderly uncared for. -The declining economy and unemployment have made it difficult for children to provide care and support for their aging parents. -Lack of income creates challenges for the elderly, leading to increased dependence and health problems. It also hinders their access to healthcare. Gender Differences: -There is a gender imbalance in assistance to the elderly, with elderly females receiving more food remittances. Government Policies and Support: -Many respondents reported receiving no medical support. |

|

Ojifinni & Uchendu Pan African Medical Journal 2022 |

1,119 adult caregivers aged 18-59 years in Oyo State, Nigeria | To assess the burden of care experienced by caregivers of elderly persons in family settings. | Qualitative study (case study) | Interviews-, structured questionnaires |

Challenges for Caregivers: -Burden of care is higher among rural caregivers than urban caregivers. -Burden of care is severe when the elderly are dependent for activities of daily living. -Factors found to be associated with the burden of care were wealth index, relationship with the elderly person, quality of relationship before caregiving began, and duration of caregiving. -The proportion who experienced burden of care was highest among those who cared for their spouses followed by those who cared for their spouse's parents. Family Dynamics: -Experience of burden of caregivers may not be negatively influenced by the quality of their relationship with the people they provide care for. Gender Differences: -Gender was not associated with the experience of burden of care. |

|

Okoye International Journal of Education and Ageing 2012 |

530 adult (40 + years, mostly well-educated) respondents | To effect of gender, culture, and education in caregiving. | Mixed methods | Questionnaires and in-depth interviews |

Economic Factors: -Socioeconomic remittances to the elderly are poor. -Urbanization, industrialization, and modernization disrupt extended families, leaving the elderly uncared for. -Economic decline and unemployment make it difficult for children to support aging parents. -Lack of income creates challenges for the elderly, affecting their independence, health, and access to healthcare. Gender Differences: - Females receiving more food remittances. Government Policies and Support: -Many respondents reported receiving no medical support. |

|

Peil Journal of Comparative Family Studies 1991 |

668 men and 336 women in three cities in Southern Nigeria | To explore the factors that affect the support elderly people receive from their family members | Quantitative study | Interviews (supplemented with observation, visits to homes of old people and discussions) |

Cultural Influences: -Rural elderly individuals maintain exchange relationships more extensively compared to urban parents. Family Dynamics: -Elderly individuals in Nigeria continue to engage in family exchange relationships. Gender Differences: -Age and gender play a role in the amount and type of support received, with rural men and older women in cities receiving the least assistance. -Fathers primarily provide material support to their children, while mothers offer services. -Older women are more likely to live alone due to widowhood or following cultural norms, while elderly men in rural areas often remain married to younger wives. -Rural women under the age of 75 are more likely to receive gifts from their children, while very elderly fathers receive better support. -Age and gender play a role in the amount and type of support received, with rural men and older women in cities receiving the least assistance. |

|

Shofoyeke & Amosun Journal of Social Sciences 2014 |

684 principals, head teachers, education administrators and planners in four out of six geo-political zones in Nigeria | To examine care and support for the elderly people in Nigeria. | Quantitative (Survey) |

Questionnaires |

Gender Differences: -Men are generally more aware of elderly persons living close to them than women, with variations across different regions. However, there is no relationship between male and female knowledge of where elderly people live. Economic Factors: -Children neglect the elderly due to poverty resulting from unemployment and underemployment, as well as beliefs associating elderly persons with witchcraft. Government Policies and Support: Many elderly people lack access to basic necessities like portable water and decent accommodation, resulting in poor living conditions, particularly in rural areas and urban slums. -There is a lack of clear welfare programs, elderly age security, subsidized health services, and adequate homes for the elderly at all levels of government. |

|

Tanyi et al. Cogent Social Sciences 2018 |

3 local government chairpersons in Nsukka local government area in the Enugu State of Nigeria who held a degree in any discipline in the social sciences and who were knowledgeable on issues concerning the elderly. |

To analyze the current policy lacuna and future issuesconcerning older persons in Nigeria. | Qualitative | Interviews and narratives of interviews |

Cultural Influences: -Nigerian communities culturally respect elders, and families are expected to care for them. -There are no cultural practices in Nigeria that prevent the government from taking care of the elderly. Government Policies and Support: -Social policies aimed at the elderly are important for their well-being, but Nigeria lacks a national social security system. -Faith-based organizations and concerned citizens' committees may provide care for the elderly, depending on resources. -Dysfunctional pension schemes and the collapse of traditional family care impact the elderly. Economic Factors: -Care for the elderly varies based on the wealth and well-being of families and communities. |

|

Wahab & Adedokun International Union for the Scientific Study of Population 2012 |

250 respondents determined by quota allocation of 125 respondents for both sexes Ikotun-Igando in Alimosho Local Government Area, Lagos State | To examine the changes in family structure and care provision for the elderly in Nigeria. | Quantitative | Structure interview in line with questionnaires |

Cultural Influences: -Reciprocity and obligation were the main motivators for family caregivers to provide continuous care. Family Dynamics: -Family structure and roles play an important role in elderly care. -Reciprocity and obligation were the main motivators for family caregivers to provide continuous care. -The quality of elderly care has declined due to changes in family structure. -Modernization, industrialization, population growth, urbanization, and nuclearization contribute to changes in family structures. Government Policies and Support: -Majority of respondents prefer institutionalized care for the elderly over traditional care. |

Appendix B

| Author (year) | Appraisal questions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Justification for the article’s importance for readership | Statement of concrete aims or formulation of questions | Description of the literature search | Referencing | Scientific reasoning | Appropriate presentation of data | Sum score | |

|

Animasahun & Chapman 2022) |

2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 9 |

Appendix C

| Author (year) | Appraisal questions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research questions? | Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research questions? | Are the findings adequately derived from the data? | Is interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? | Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection and analysis? | Rating | |

|

Akinrolie et al (2020) |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

|

Ebimgbo et al. (2022) |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

|

Ebimgbo & Okoye (2022) |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

|

Ebimgbo et al. (2019) |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| Eboiyehi & Onwuzuruigbo (2014) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

|

Iwuagwu, Ngwu & Ekoh (2022) |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| Ojifinni & Uchendu (2022) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

H |

|

Tanyi et al. (2018) |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

Appendix D

| Is there an adequate rationale for using a mixed methods design to address the research question? | Are the different components of the study effectively integrated to answer the research question? | Are the outputs of the integration of qualitative and quantitative components adequately interpreted? | Are divergencies and inconsistencies between quantitative and qualitative results addressed? | Do the different components of the study adhere to the quality criteria of each tradition of the method involved? | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rating | ||||||

|

Ani & Isiugo-Abanihe (2017) |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

|

Fajemilehin 2000) |

N | CT | Y | N | Y | L |

|

Mayston et al. PLOS ONE (2017) |

CT | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

|

Namadi (2016) |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

|

Okoye (2012) |

N | Y | Y | N | Y | H |

Appendix E

| Author/Year | Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research? | Is the sample representative of the target population? | Are measurements appropriate? | Is the risk of non-bias low? | Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rating | ||||||

|

Ebimgbo and Okoye (2017) |

CT | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

|

Iwuagwu, Ugwu, Ugwuanyi et al. (2022) |

Y | Y | Y | CT | Y | H |

|

Odaman & Ibiezugbe (2014) |

Y | Y | Y | CT | Y | H |

| Peil (1991) | N | N | CT | N | Y | L |

|

Shofoyeke & Amosun (2014) |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

|

Wahab & Adedokun (2012) |

Y | Y | CT | CT | Y | H |

References

- Abrams, J. A., Tabaac, A., Jung, S., & Else-Quest, N. M. (2020). Considerations for employing intersectionality in qualitative health research. Social Science & Medicine. 258, 113-138. [CrossRef]

- Agree, E. M. (2018). Demography of aging and the family. In M.D. Hay ward & M.K. Majmundar MK (Eds.), Future directions for the demography of aging: Proceedings of a workshop (pp. 159-186). National Academies Press.

- Akinrolie, O., Okoh, A. C., & Kalu, M. E. (2020). Intergenerational support between older adults and adult children in Nigeria: The role of reciprocity. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 63(5), 478-498. [CrossRef]

- Ani, J. I. (2014). Care and support for the elderly in Nigeria: a review. The Nigerian Journal of Sociology and Anthropology,12(1), 10. [CrossRef]

- Ani, J.I. & Isiugo-Abanihe, U.C. (2017) Conditions of the elderly in selected areas in Nigeria. International Journal of Sociology of the Family, 43 (1-2), 73-89.

- Animasahun, V. J., & Chapman, H. J. (2017). Psychosocial health challenges of the elderly in Nigeria: a narrative review. African Health Sciences, 17(2), 575-583. [CrossRef]

- Asuquo, E. F., Etowa, J. B., & Akpan, M. I. (2017). Assessing women caregiving role to people living with HIV/AIDS in Nigeria, West Africa. SAGE Open, 7(1). [CrossRef]

- Asuquo, E. F., & Akpan-Idiok, P. A. (2020). The exceptional role of women as primary caregivers for people living with HIV/AIDS in Nigeria, West Africa. In Suggestions for Addressing Clinical and Non-Clinical Issues in Palliative Care. Intechopen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.93670.

- Baethge, C., Goldbeck-Wood, S., & Mertens, S. (2019). SANRA—a scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Research Integrity and Peer Review, 4(1), 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Bauer, G. R. (2014). Incorporating intersectionality theory into population health research methodology: Challenges and the potential to advance health equity. Social Science & Medicine, 110, 10-17. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Ari, A., & Lavee, Y. (2004). Cultural orientation, ethnic affiliation, and negative daily occurrences: A multidimensional cross-cultural analysis. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 74(2), 102-111. [CrossRef]

- Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 5(3), 77-101. [CrossRef]

- Carbado, D. W., Crenshaw, K. W., Mays, V. M., & Tomlinson, B. (2013). Intersectionality: Mapping the movements of a theory. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 10(2), 303-312. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A. (2021). The Challenges of intersectionality in the lives of older adults living in rural areas with limited financial resources. Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine, 7, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Daly, J., Kellehear, A., & Gliksman, M. (1997). The public health researcher: A methodological approach. Oxford University Press.

- Ebimgbo, S. O., Chukwu, N. E., Onalu, C. E., & Okoye, U. O. (2019). Perceived challenges associated with care of older adults by family caregivers and implications for social workers in South-east Nigeria. Indian Journal Gerontology, 33(2), 160–177.

- Ebimgbo, S. O., & Okoye, U. O. (2017). Perceived factors that predict the availability of social support when it is needed by older adults in Nnewi, South-East Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Social Sciences, 13(1), 10–17.

- Ebimgbo, S. O., Atama, C. S., Igboeli, E. E., Obi-keguna, C. N., & Odo, C. O. (2022). Community versus family support in caregiving of older adults: Implications for social work practitioners in South-East Nigeria. Community, Work & Family, 25(2), 152-173. [CrossRef]

- Ebimgbo, S. O., & Okoye, U. O. (2022). Challenges of left-behind older family members with international migrant children in south-east Nigeria. Journal of Population Ageing, 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Eboiyehi, F. A., & Onwuzuruigbo, I. (2014). Care and support for the aged among the Esan of South-South Nigeria. The Nigerian Journal of Sociology and Anthropology, 12(1), 44-61. [CrossRef]

- Fajemilehin, B. (2000). Old age in a changing society: elderly experiences of caregiving in Osun State, Nigeria. Africa Journal of Nursing and Midwifery, 2(1), 23-27.

- Garrard, J. (2017). Health sciences literature review made easy: The matrix method (5th ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- Guberman, N., Maheu, P., & Maillé, C. (1992). Women as family caregivers: Why do they care?. The Gerontologist, 32(5), 607-617. [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q. N., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M.P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., O’Cathain, A. Rousseau, M.C & Pluye, P. (2018a). The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information, 34(4), 285-291. [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q., Pluye, P., Fabregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, MP., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., O’Cathain, A., Rousseau, M-C., & Vedel, I. (2018b). Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT). Version 2018. McGill University Department of Family Medicine. [CrossRef]

- International Monetary Fund. (2025). G20 background note on aging and migration: Global demographic trends. IMF. https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Research/imf-and-g20/2025/G20-Background-Note-on-Aging-and-Migration.ashx.

- Iwuagwu, A. O., Ngwu, C. N., & Ekoh, C. P. (2022). Challenges of female older adults caring for their very old parents in rural Southeast Nigeria: A qualitative descriptive inquiry. Journal of Population Ageing, 15, 907–923. [CrossRef]

- Iwuagwu, A. O., Ugwu, L. O., Ugwuanyi, C. C., & Ngwu, C. N. (2022). Family caregivers' awareness and perceived access to formal support care services available for older adults in Enugu State, Nigeria. African Journal of Social Work, 12(2), 12-20.

- Kalia, P., Saini, S., & Vig, D. (2021). An appraisal of burden of stress among family caregivers of dependent elderly. Indian Journal of Health and Wellbeing, 12(1), 111-115.

- Kirkevold, M. (1997). Integrative nursing research – An important strategy to further the development of nursing science and nursing practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 25, 977–984. [CrossRef]

- Lane, P., Tribe, R., & Hui, R. (2011). Intersectionality and the mental health of elderly Chinese women living in the UK. International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care, 6(4), 34-41. [CrossRef]

- McCarty, C. A., Weisz, J. R., Wanitromanee, K., Eastman, K. L., Suwanlert, S., Chaiyasit, W., & Band, E. B. (1999). Culture, coping, and context: Primary and secondary control among Thai and American youth. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 40(5), 809-818.

- Macrotrends. (2023). Nigeria life expectancy 1950–2023. macrotrends.net>NGA>life.

- Mayston, R., Lloyd-Sherlock, P., Gallardo, S., Wang, H., Huang, Y., Montes de Oca, V., & Prince, M. (2017). A journey without maps—Understanding the costs of caring for dependent older people in Nigeria, China, Mexico and Peru. PloS one, 12(8), e0182360. [CrossRef]

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264-269.

- Morgan, T., Ann Williams, L., Trussardi, G., & Gott, M. (2016). Gender and family caregiving at the end-of-life in the context of old age: A systematic review. Palliative Medicine, 30(7), 616-624. [CrossRef]

- Namadi, M.M. (2016). Pattern of relationship between family caregivers and the elderly care recipients in Kano municipal local government area of Kano state, Nigeria. Global Journal of Applied, Management and Social Sciences (GOJAMSS), 12, 60-66.

- Nortey, S. T., Aryeetey, G. C., Aikins, M., Amendah, D., & Nonvignon, J. (2017). Economic burden of family caregiving for elderly population in southern Ghana: the case of a peri-urban district. International Journal for Equity in Health, 16, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Odaman, O. M., & Ibiezugbe, M. I. (2014). An empirical investigation of some social and economic remittances from relatives to the elderly Edo people. IFE PsychologIA: An International Journal, 22(2), 64-71.

- Ojifinni, O. O., & Uchendu, O. C. (2022). Experience of burden of care among adult caregivers of elderly persons in Oyo State, Nigeria: a cross-sectional study. The Pan African Medical Journal, 42, 64.

- Okoro, O (2013). Long distance international caregiving to elderly parents left behind: A case of Nigerian adult children immigrants in USA. [Doctoral dissertation]. University of North Texas .

- Okoye, U. O. (2012). Family care-giving for ageing parents in Nigeria: Gender differences, cultural imperatives and the role of education. International Journal of Education and Ageing, 2(2), 139-154.

- Pace, R., Pluye, P., Bartlett, G., Macaulay, A. C., Salsberg, J., Jagosh, J., & Seller, R. (2012). Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 49(1), 47–53. [CrossRef]

- Peil, M. (1991). Family support for the Nigerian elderly. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 22(1), 85-100. [CrossRef]

- Population Reference Bureau. (2020). Countries with the oldest population in the world. https://www.prb.org/countries-with-the-oldest-populations/.

- Schulz, R., & Eden, J. (2016). Family caregiving roles and impacts. In R. Schulz & J. Eden (Eds.), Families caring for aging America (pp. 73-122). The National Academies Press.

- Sharma, N., Chakrabarti, S., & Grover, S. (2016). Gender differences in caregiving among family-caregivers of people with mental illnesses. World Journal of Psychiatry, 6(1), 7. [CrossRef]

- Shofoyeke, A. D., & Amosun, P. A. (2014). A survey of care and support for the elderly people in Nigeria. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(23), 2553–2563. [CrossRef]

- Tanyi, P. L., André, P., & Mbah, P. (2018). Care of the elderly in Nigeria: Implications for policy. Cogent Social Sciences, 4(1), 1555201. [CrossRef]

- Sidloyi, S. (2016). Elderly, poor and resilient: Survival strategies of elderly women in female-headed households: An intersectionality perspective. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 47(3), 379-396. [CrossRef]

- Togonu-Bickersteth, F., & Akinyemi, A. I. (2014). Ageing and national development in Nigeria: Costly assumptions and challenges for the future. African Population Studies, 27(2), 361-371. [CrossRef]

- Valentine, G. (2007). Theorizing and researching intersectionality: A challenge for feminist geography. The Professional Geographer, 59(1), 10-21. [CrossRef]

- Wahab, E.O. & U.C. Isiugo-Abanihe. (2010). Assessing the impact of old age security expectation on elderly persons’ achieved fertility in Nigeria. Indian Journal of Gerontology. 24(3): 357-378.

- Wahab, E. O., & Adedokun, A. (2012). Changing family structure and care of the older persons in Nigeria. International Union for the Scientific Study of Population, 25.

- Wan H. (2022). Increases in Africa’s older population will outstrip growth in any other world region. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2022/04/why-study-aging-in-africa-region-with-worlds-youngest-population.html#:~:text=But%2C%20by%202050%2C%20the%20older,and%20approximating%20that%20of%20Europe.

- Wiens J. A. (2016). Population growth. Ecological challenges and conservation conundrums. Essays and Reflections for a Changing World, 75(6), 914–933.

- Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(5), 546-553.

- World Health Organization. (2022). Ageing and health. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health#:~:text=By%202030%2C%201%20in%206,will%20double%20(2.1%20billion).

- Yankuzo, K. I. (2014). Impact of globalization on the traditional African cultures. International Letters of Social and Humanistic Sciences, 15, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Yenilmez, M. I. (2015). Economic and social consequences of population aging the dilemmas and opportunities in the twenty-first century. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 10(4), 735-752. [CrossRef]

| Themes | Sub-themes |

|---|---|

| Cultural Influences | High value on respecting and honoring elders Moral duty of younger family members to provide care and support. Filial piety and children's duty to care for and honor parents |

| Gender Differences | Women as primary caregivers in many households Female inclination to provide caregiving assistance. Challenges faced by adult daughters due to education and financial limitations |

| Family Dynamics | Primary responsibility for caregiving lies with the family. Intergenerational care transfer and reliance on younger family members Challenges in extended family system and changing family structures |

| Economic Factors | Financial limitations and scarce resources Coping strategies of elderly individuals to supplement support. Impact of migration, westernization, changing family structure, urbanization on care and support services |

| Challenges for Caregivers | Financial constraints Limited access to healthcare services Balancing multiple responsibilities demands Emotional and physical toll on caregivers |

| Government Policies and Support | Targeted social policies. Support care services for elderly individuals |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).