1. Introduction

Dr. Anouk W. Vaes and her collaborators at CIRO performed one of the largest systematic surveys of ME/CFS symptom patterns, applying clustering methods to patient-reported outcomes to identify recurring constellations of symptoms1. They used symptom surveys based on the DePaul Symptom Questionnaire version 2 (DSQ-2) from 337 patients to identify a total of 45 patient clusters, of which 13 were of size ≥ 10. We used the publicly available data of their final 13 clusters for analysis2.

While Vaes described each cluster, and noted some differences among symptom severity, an overall organizing principle was not proposed. Other methods have been used to group ME/CFS phenotypes, including by severity alone, or a combination of severity and symptoms, but no consensus has emerged on how to best group patients.

Our analysis suggests that the Vaes ME/CFS clusters can be organized into two overarching families defined by their relationship to PEM. This reduces the complexity of the cluster symptom intensities and highlights a subgroup within the Vaes clusters that has not been explicitly recognized in prior work. Once separated and profiled, this subgroup has characteristics that resemble fibromyalgia.

If this subgroup really is related to fibromyalgia, then the Vaes data, taken together with our analysis, may provide one of the first opportunities to quantitatively describe fibromyalgia-like patients within ME/CFS from a single, uniformly collected cohort. Otherwise, it may represent a distinct but as-yet uncharacterized subgroup worthy of further study. We will cover this in depth, below in

Section 3.

2. Visual Analysis of Symptom Domains

vs. PEM

The strong weight of PEM symptoms makes the Vaes dataset tricky to interpret if you only look at raw intensity, so instead we compared overall symptom levels to PEM severity. From this comparison we identified two groups of clusters that maintain their integrity across most symptom domains.

Because these analyses are exploratory and based on cluster-level data, the patterns described below should be interpreted as hypothesis-generating.

We will start by showing how the groups are most similar, then how they differ. We add an “all” category to gauge overall symptom severity to the original symptom domains. Our use of the terms “high-intensity” and “low-intensity” does not reproduce the clusters described by Vaes or others but reflects a new organization based on how symptom domains scale with PEM. Vaes used the DePaul symptom groupings which we keep as-is.

Notes: The DSQ-2 uses a single symptom for fatigue. Also, for the “Overall” chart we used the arithmetic mean instead of geometric mean for the Y axis. All other graphs in this study use geometric means exclusively. Shaded bands represent the 95% confidence interval of the linear models when used. While this section focuses on visual inspection, we provide more statistical analysis in

Appendix B.

2.1. Similarities

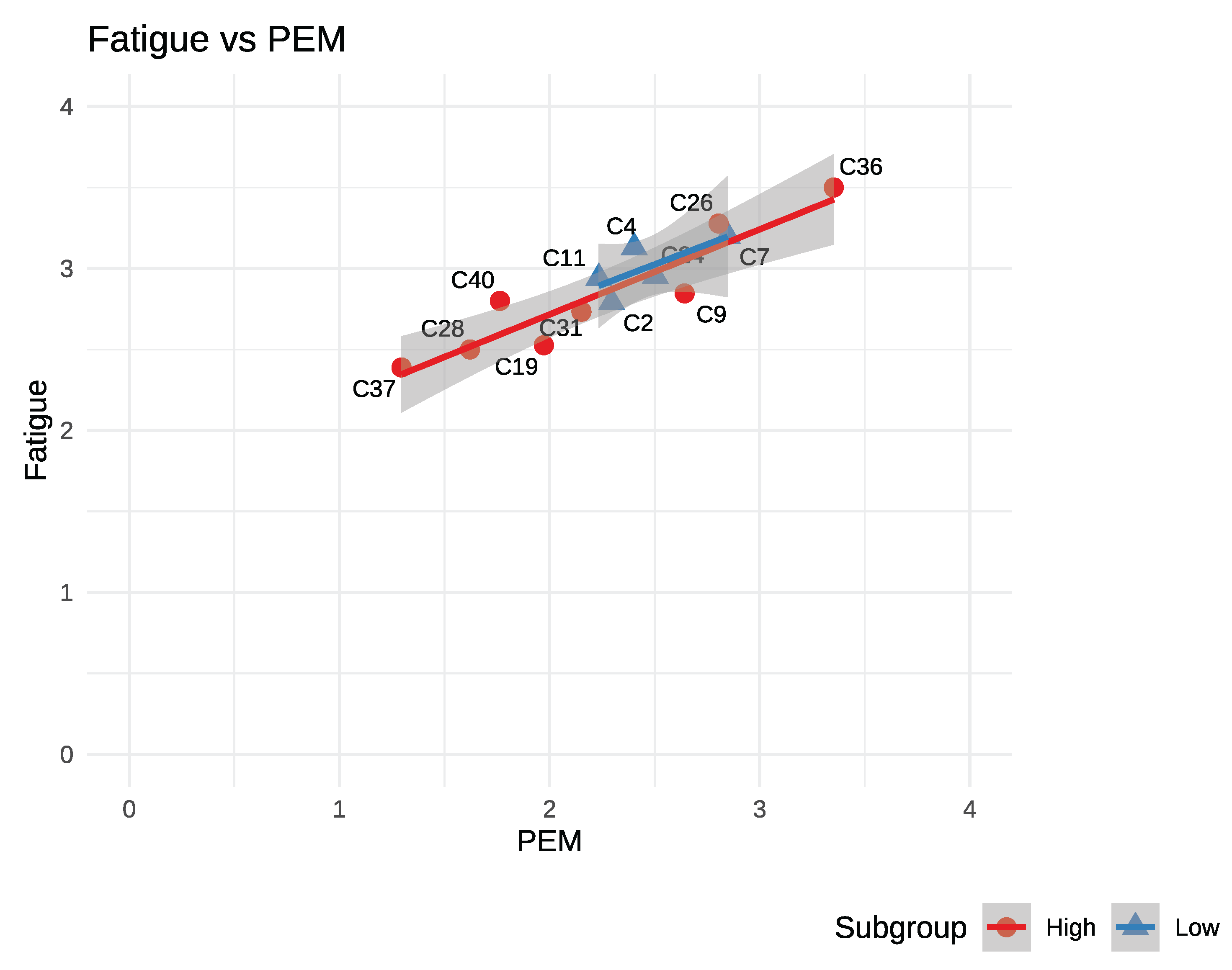

In terms of fatigue, the two groups overlap completely, as ME/CFS patient clusters are expected to. See

Figure 1, below. While the lines have a similar slope and offset we note the R² value is significantly weaker in the low-intensity group (0.54 vs. 0.86).

While fatigue shows complete overlap in our groups the next charts (

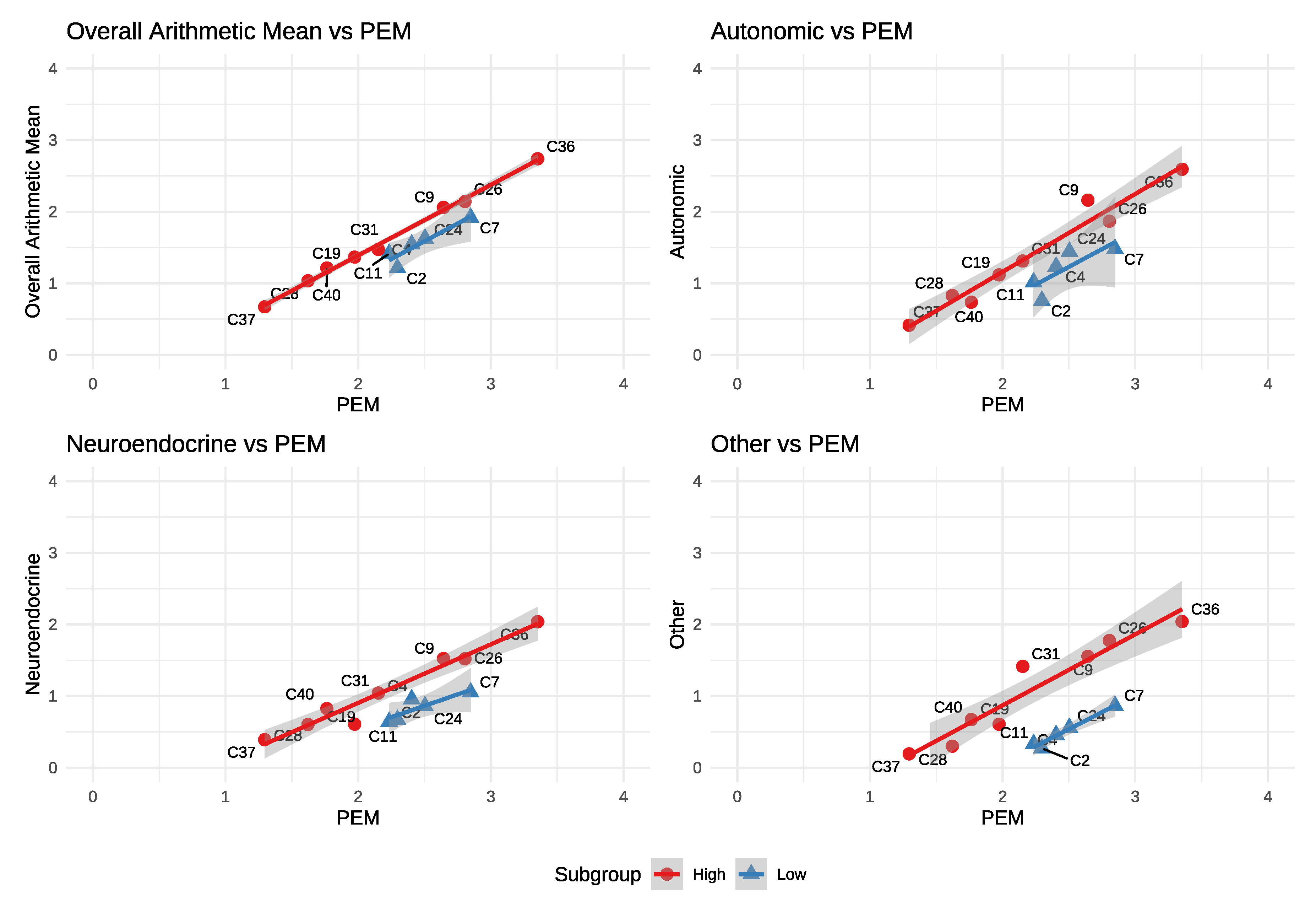

Figure 2) show how they stand out. In the first chart (top left) we compare the average of all symptoms to PEM. In this chart one can easily discern two tiers of clusters. One has a higher overall symptom burden at any given PEM level compared to the other and this relationship is where we derive the names for our groups: high and low-intensity.

Autonomic, Neuroendocrine and Other also follow a similar pattern: Parallel but lower than the high-intensity group.

We note that the limited range of PEM severity in the low-intensity group (~2.2 to 2.9) may have otherwise caused it to remain undetected.

Groupings: From visual inspection of the charts above we group clusters C9, C19, C26, C28, C31, C36, C37, C40 as high-intensity, C2, C4, C7, C11, C24 as low-intensity. We’ll keep these groupings for all plots that follow. The high and low groups are approximately 54.5% and 45.5% of the total cohort, respectively.

The last chart (Other vs. PEM) shows a markedly lower offset and is perhaps the most visibly obvious difference between the two groups. The two symptoms in ‘other’ are sensitivity to mold and vibration.

While the groups maintain integrity, the parallelism observed in the charts above does not hold in the next charts and suggests a more complex physiological cause for the differences.

2.2. Increasing Amplification vs. PEM

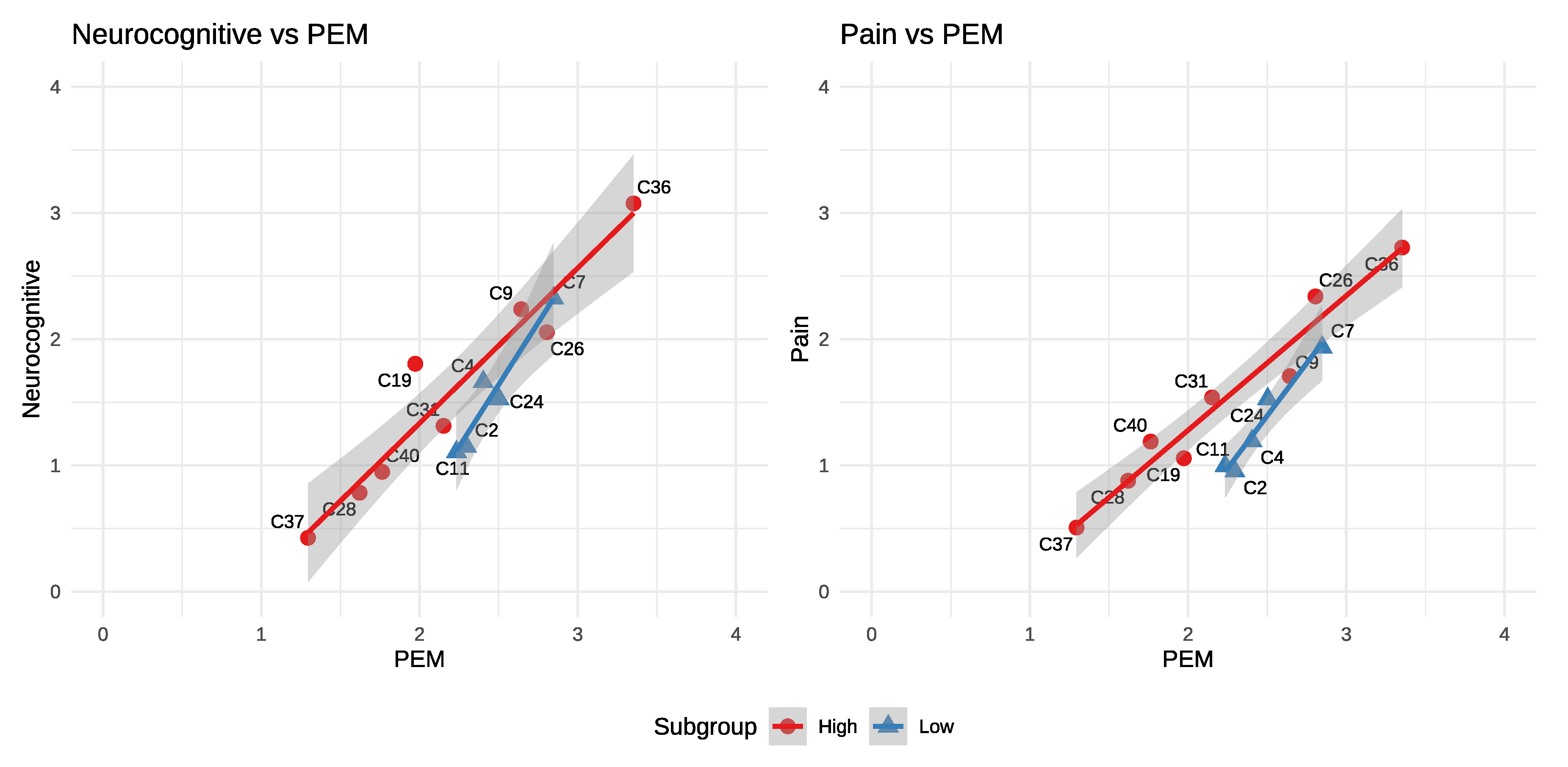

Pain and neurocognitive domains show that while the low-intensity group remains offset, symptom domain amplification is increased. As PEM increases to 3, C7 comes very close to the high-intensity line.

The two charts above, while not severe enough to claim this is fibromyalgia with PEM, begin to suggest it. We discuss this more fully in the Fibromyalgia–like group section.

2.3. Different Correlations to PEM

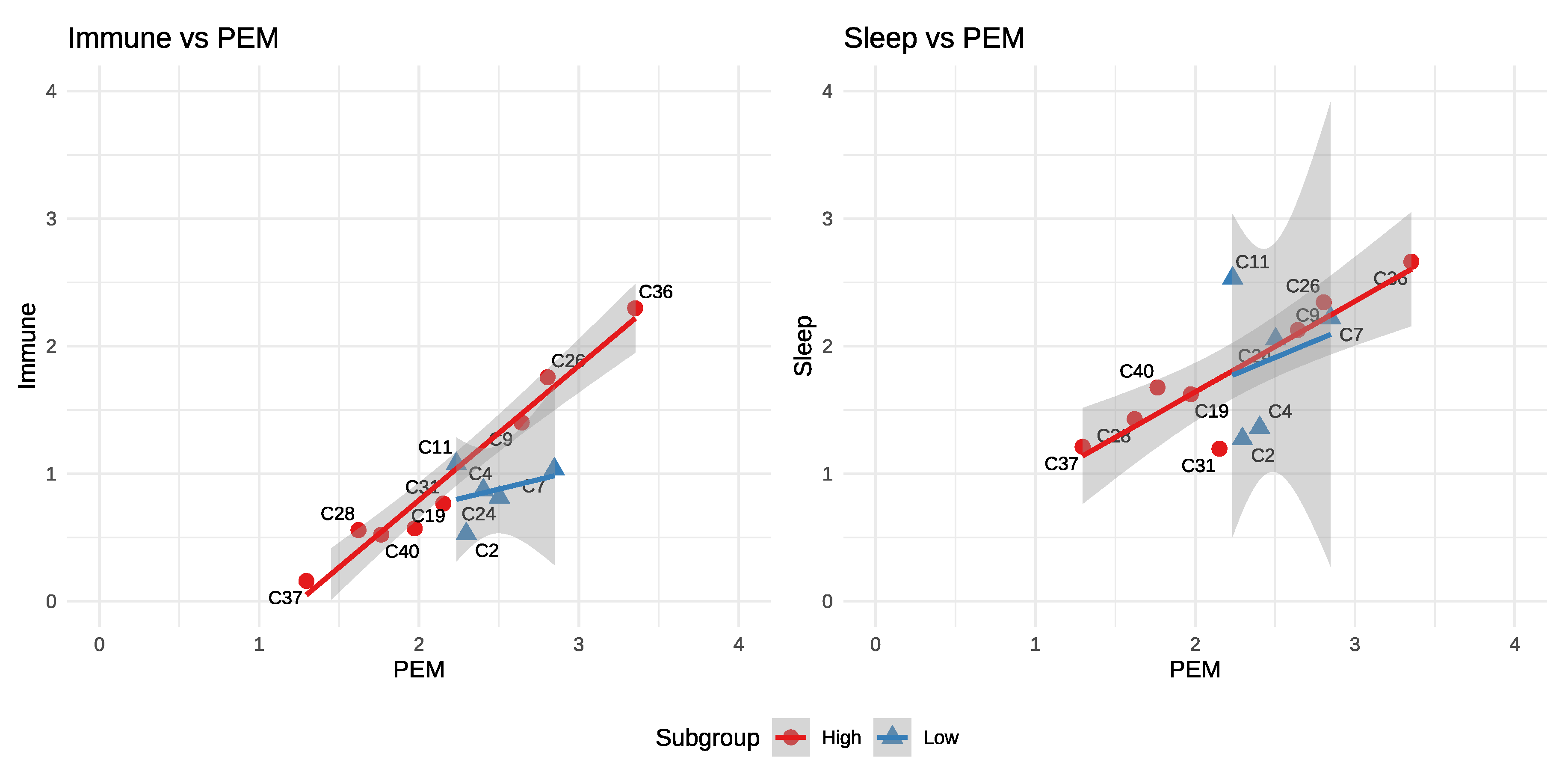

In all of the previous charts we’ve shown that both groups maintain a strong but distinct relationship to PEM. By contrast, the immune and sleep domains show little to no correlation with PEM severity in the low-intensity group. Notably, despite this lack of correlation, sleep disturbance can be pronounced in the low-intensity group.

2.4. Summary of Differences

High-intensity: Has a consistent amplification pattern: as PEM increases, all other symptom domains rise together.

Low-intensity: Presents a more selective profile. Pain, neurocognitive, and neuroendocrine symptoms escalate more rapidly with PEM, while sleep and immune symptoms show little or no correlation. The elevated neurocognitive and pain symptoms, together with variable sleep symptom intensity makes the low-intensity group more suggestive of fibromyalgia than the high-intensity group. Additionally, the low-intensity group is notably nestled in the middle of the overall PEM range which could allow it to hide among the other clusters if not actively searched for.

We summarize these differences in the table below.

Table 1.

Summary of Group Differences.

Table 1.

Summary of Group Differences.

| Feature |

High group |

Low group |

| Overall vs. PEM |

Higher |

Lower - esp. “other” |

| Fatigue |

R² - 0.86 |

Weaker R² - 0.54 |

| PEM range |

~1.3 – 3.4 |

Narrower ~2.2 – 2.9 |

| Neurocognitive |

Tracks PEM |

Elevated amplification |

| Pain |

Tracks PEM |

Elevated amplification |

| Immune |

Tracks PEM |

Flat at ~1 |

| Sleep |

Tracks PEM |

~1.4 – 2.5, but uncorrelated |

Symptom Severity: In terms of overall symptom range the two groups largely overlap. The high-intensity group, by symptom intensity alone, could be considered a superset of the low-intensity group. It is the differing relationships to PEM and the selective amplification of certain symptom domains in the low-intensity group that set the two groups apart.

3. Exploring the Fibromyalgia–like Subgroup

The question of whether we have identified a useful subgroup in the Vaes data is a separate debate, but based on implications in

Section 2.2 a discussion of whether the low-intensity group could be related to fibromyalgia is warranted. Vaes

1 described the selection criteria for their cohort as follows:

Almost 90% of the participants fulfilled the Fukuda case definition, compared to 80%, 59% and 39% fulfilling the IOM, CCC and ME-ICC case definitions, respectively. More than a quarter of the participants met the criteria for all four different case definitions, whilst 5% of the participants met none of the abovementioned case definitions,…

This seems like a potentially wide net and may help explain two potential subgroups which suggest a different pathophysiology. An examination of the proposed low-intensity subgroup shows it occupies a very narrow range of PEM intensity and then stops abruptly when PEM reaches ~2.9. We see no reason for a PEM-specific boundary but the charts in

Figure 3 suggest that our group is not PEM-limited but pain- and neurocognitive-limited within this dataset. In those charts, pain and neurocognitive symptoms trend upward and then the clusters stop at C7 just before they would cross the high-intensity group trend lines. This truncation could be due to diagnostic criteria that would classify these individuals as fibromyalgia when pain and neurocognitive scores are above the high-intensity lines.

Figure 3.

Pain and Neurocognitive vs. PEM.

Figure 3.

Pain and Neurocognitive vs. PEM.

Figure 4.

Immune and Sleep vs. PEM.

Figure 4.

Immune and Sleep vs. PEM.

This would align with published DSQ-2 studies showing that ME/CFS patients who meet fibromyalgia criteria exhibit amplified pain and more severe post-exertional malaise compared with ME/CFS alone3–5 and would also explain why our subgroup occupies such a narrow range of PEM scores compared to the overall cohort.

Table 2.

ME/CFS vs. Fibro.

Table 2.

ME/CFS vs. Fibro.

| Domain (DSQ / DSQ-PEM items) |

ME/CFS (no FM) |

ME/CFS + FM |

FM (alone) |

| Post-Exertional Malaise (PEM) |

Core feature; DSQ captures frequency &

severity well |

Higher PEM frequency/severity than ME/CFS alone

(incl. “General” and “Muscle” PEM factors) |

Not a defining

criterion of FM; DSQ-PEM shows variable/typically lower PEM signal vs

ME/CFS cohorts |

| Pain |

Common, variable; not primary diagnostic driver |

Higher

overall pain burden; amplifies illness severity |

Defining;

widespread musculoskeletal pain central to diagnosis |

| Neurocognitive |

Frequent (attention, memory, processing speed) |

Often

worse with FM comorbidity |

Present in many FM cohorts; DSQ-SF

cognitive items used in FM studies |

| Sleep |

Non-restorative sleep common |

Often worse with FM

comorbidity |

Common in FM, often prominent |

| Autonomic / Immune / Neuroendo |

Captured across DSQ domains;

heterogeneous patterns documented |

Can be more burdensome with

FM comorbidity |

Less emphasized in FM criteria; may appear but not

core |

It is possible that current pain and neurocognitive thresholds for a fibromyalgia diagnosis may focus too heavily on symptom severity to capture the nuanced patterns revealed by our subgroup analysis. If these groups are commingled, then properly separating the two groups may require a more complex approach that relies less on absolute pain scores and more on the ratio of symptom domain scores to PEM.

While the hypothesis that this subgroup is related to fibromyalgia is attractive, other explanations may also be true. At the very least, this data need direct comparison to fibromyalgia cohorts before it can be used to formally claim a fibromyalgia link.

4. Discussion

We have shown that the Vaes clusters can be organized into two subgroups defined by symptom domains relative to PEM, and that these subgroups remain consistent across most symptom domains.

We’ve also shown that grouping the Vaes clusters by their relationship to PEM simplifies this complexity at the domain and cluster levels, but this may not translate directly to grouping individual patients. Vaes1 provided cluster-specific summaries of standout symptoms; some of those align with our domain-based charts while others show a different emphasis, underscoring the challenge of reconciling symptom-level observations with domain-level analyses.

Although these charts look compelling, several cautions are warranted. This is a secondary analysis of patient clusters defined by symptom domains with small subgroup sizes (8 and 5 clusters). The original clustering methods of Vaes et al. may have obscured or exaggerated some relationships we show here. Moreover, visual inspection of the plots may suggest directional trends where none truly exist.

Despite these limitations, we believe further steps should be taken. Using the original patient scores could validate, refine, or repudiate these subgroups and possibly produce a short list of differentiating symptoms. If this proves useful then examining biological markers across these subgroups could help to reveal underlying pathophysiological differences. Additionally, using similar analysis to what we’ve done here with fibromyalgia and long-COVID could help clarify relationships among these overlapping conditions, or help redefine how we classify ME/CFS, or fibromyalgia.

5. Conclusion

Our secondary analysis suggests that the 13 clusters identified by Vaes can be organized into two broader structures defined by overall symptom intensity relative to PEM severity. These two groups remain coherent across symptom domains and display distinct, largely linear relationships with PEM. Although exploratory and limited to cluster-level data, these findings offer a reproducible framework for further research, specifically for validating these potential subgroups and exploring their clinical and biological relevance.

Author Contributions

Erik K. Squires conceived the study, performed the analysis, and wrote the manuscript. This work presents an original investigative method and resulting framework which were both developed and first reported by the author in this preprint.

Funding

This work received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

This paper could not exist without the foundational work of Dr. Anouk W. Vaes and her colleagues at CIRO, whose clustering study1 and publicly available cluster summary data2 provided the basis for our analysis. We are deeply grateful for their contribution to the field. Dr. Vaes had no role in the writing of this paper, and all errors or misinterpretations are the responsibility of the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethics Statement

This study reanalyzed publicly available reports and published symptom cluster data (Vaes 2023). No new patient data were collected.

Appendix A. Cluster Summary Data

We use the Vaes cluster spreadsheet2 exclusively as our data source. We use R for significant cleaning and transformation from Excel to CSV. After removing everything but the mean severity of the symptoms in the 13 clusters we:

Group each cluster by symptom domain and calculate geometric means for each symptom domain within each cluster.

Rotate the table

Add a new column, “all_mean” which is the arithmetic mean of all symptoms within each cluster.

Save this file as cluster_grouped_tidy.csv

This file is what we then used for our analysis, and the plots. We present the final data used below. Values were rounded and abbreviations used for formatting. See the Code Availability section for links to the code used to generate this file.

Table A1.

Cluster Summary Data with Geometric Means by Symptom Domain.

Table A1.

Cluster Summary Data with Geometric Means by Symptom Domain.

| cluster |

all_mean |

PEM |

fatigue |

Auto |

Immune |

NC |

NE |

pain |

other |

| C2 |

1.21 |

2.30 |

2.79 |

0.76 |

0.53 |

1.15 |

0.67 |

0.95 |

0.27 |

| C4 |

1.55 |

2.40 |

3.13 |

1.24 |

0.87 |

1.66 |

0.96 |

1.19 |

0.46 |

| C7 |

1.92 |

2.85 |

3.20 |

1.48 |

1.03 |

2.32 |

1.05 |

1.94 |

0.86 |

| C9 |

2.06 |

2.64 |

2.85 |

2.16 |

1.40 |

2.24 |

1.52 |

1.71 |

1.55 |

| C11 |

1.42 |

2.23 |

2.94 |

1.02 |

1.08 |

1.11 |

0.64 |

1.00 |

0.33 |

| C19 |

1.37 |

1.97 |

2.53 |

1.12 |

0.57 |

1.81 |

0.61 |

1.06 |

0.60 |

| C24 |

1.63 |

2.50 |

2.95 |

1.44 |

0.82 |

1.52 |

0.86 |

1.53 |

0.56 |

| C26 |

2.14 |

2.80 |

3.28 |

1.87 |

1.76 |

2.06 |

1.52 |

2.34 |

1.77 |

| C28 |

1.03 |

1.62 |

2.50 |

0.83 |

0.56 |

0.78 |

0.60 |

0.88 |

0.30 |

| C31 |

1.47 |

2.15 |

2.73 |

1.31 |

0.77 |

1.31 |

1.04 |

1.54 |

1.41 |

| C36 |

2.74 |

3.35 |

3.50 |

2.59 |

2.30 |

3.08 |

2.04 |

2.73 |

2.04 |

| C37 |

0.67 |

1.30 |

2.39 |

0.41 |

0.16 |

0.43 |

0.39 |

0.51 |

0.19 |

| C40 |

1.21 |

1.76 |

2.80 |

0.74 |

0.52 |

0.95 |

0.82 |

1.19 |

0.67 |

Appendix B. Statistical Analysis

In the body of the text, we used visual analysis to identify two subgroups of ME/CFS patient clusters defined by their symptom domain profiles relative to PEM severity. Here we present statistical analysis that may help clarify the data in the plots.

Given the exploratory nature of this study and the small number of clusters, these results should be interpreted as descriptive rather than confirmatory.

R² by Group

We compare the regression coefficient (R²) of the symptom domains in three levels:

Combined (all clusters)

High-intensity group

Low-intensity group

Table A2.

R² by Domain.

| Domain |

Combined R² |

High-intensity R² |

Low-intensity R² |

| All_mean |

0.91 |

1.00 |

0.84 |

| Autonomic |

0.79 |

0.96 |

0.62 |

| Fatigue |

0.84 |

0.86 |

0.54 |

| Immune |

0.78 |

0.96 |

0.11 |

| Neurocognitive |

0.85 |

0.92 |

0.93 |

| Neuroendocrine |

0.73 |

0.96 |

0.75 |

| Other |

0.52 |

0.92 |

0.96 |

| Pain |

0.81 |

0.95 |

0.95 |

| Sleep |

0.53 |

0.81 |

0.05 |

Table A2 shows that for almost every symptom domain, the high-intensity group has a higher R² than the combined group, which in turn has a higher R² than the low-intensity group. In some cases – such as neurocognitive, neuroendocrine, and Other – the combined R² is significantly weaker than either of the subgroups.

Leave-one-out Analysis

We discovered our two groups by visual analysis, but we can re-identify the set using leave-one-out analysis. In this analysis we go through each domain and examine what happens when we remove one cluster at a time. The goal is to identify which clusters, when removed, improve R² the most.

We summarize the mean R² differences, in order of greatest improvement, in

Table 2.

| Cluster |

Group |

Domains Improved |

Mean R² |

| C2 |

low |

9 |

0.0379 |

| C11 |

low |

9 |

0.0271 |

| C4 |

low |

8 |

0.0191 |

| C31 |

high |

7 |

0.0163 |

| C7 |

low |

5 |

0.0129 |

| C24 |

low |

8 |

0.0126 |

Of the top 6 clusters only C31 is not part of the low-intensity group. While this does not prove the existence of two subgroups it does support the idea that the members of the low-intensity group are, overall, responsible for most of the R² degradation in the combined group.

ANCOVA

We analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) to identify the domains which could be most statistically significant and discriminatory. We compare our two groups for each symptom domain. We arrange the results by descending F-statistic and show the p-value rounded to three decimal places.

| Domain |

F statistic |

p-value |

Significance |

| Other |

33.3 |

< 0.001 |

*** |

| Neuroendocrine |

11.6 |

0.007 |

** |

| Fatigue |

5.2 |

0.046 |

* |

| Autonomic |

3.8 |

0.08 |

. |

| Pain |

3.1 |

0.108 |

NA |

| Immune |

1.4 |

0.268 |

NA |

| All_mean |

1.0 |

0.33 |

NA |

| Sleep |

0.2 |

0.647 |

NA |

| Neurocognitive |

0.0 |

0.849 |

NA |

Table A1 shows agreement with the charts that Other, Neuroendocrine and Autonomic domains show the most significant offsets between the two groups. The high F-statistic and low p-value for Fatigue, however, do not agree with the regression lines. As we note earlier in

Section 2.1, the lines in

Figure 1 are nearly identical but R² is significantly weaker in the low-intensity group. The high F-statistic and P-value in the ANCOVA analysis for fatigue is most likely an artifact of the wide spread in the low-intensity group.

References

- Vaes, A.W.; et al. Symptom-based clusters in people with ME/CFS: An illustration of clinical variety in a cross-sectional cohort. Journal of Translational Medicine 2023, 21, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaes, A. W. & collaborators. Supplementary dataset (excel): Additional file 3: Table S1: 12967_2023_3946_MOESM3_ESM.xlsx. Journal of Translational Medicine, Springer Nature (2023). https://static-content.springer.com/esm/art%3A10.1186%2Fs12967-023-03946-6/MediaObjects/12967_2023_3946_MOESM3_ESM.

- Jason, L.A.; et al. The DePaul symptom questionnaire-2: A validation study. Fatigue: Biomedicine, Health & Behavior 2015, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManimen, S.L.; Jason, L.A.; Williams, Y.J. Post-exertional malaise in patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome with comorbid fibromyalgia. Fatigue: Biomedicine, Health & Behavior 2017, 5, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almenar-Pérez, E.; et al. MicroRNA profiles distinguish fibromyalgia, ME/CFS, and ME/CFS with fibromyalgia. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 28955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).