In this section, we present the experimental studies conducted by using the aforementioned testbed.

4.1. Experimental Configuration

To debug and optimize the algorithm, the following outlines the workflow of human posture recognition and assessment task. The Human Pose Detection (Pose Landmarker [

24]) task utilizes the

create_from_options function to initialize the task, while the

create_from_options function accepts the configuration option values that need to be processed.

Table 9 presents the parameter configurations along with their descriptions.

The Pose Landmarker task exhibits distinct operational logic across its various execution modes. In IMAGE or VIDEO mode, the task blocks the current thread until it has fully processed the input image or frame. Conversely, in LIVE STREAM mode, the task invokes a result callback with the detection outcomes immediately after processing each frame. If the detection function is called while the task is occupied with other frames, it simply ignores the new input frame. In this system, although the live stream from the webcam inherently aligns with the LIVE STREAM mode, the VIDEO mode is deliberately chosen to ensure detection accuracy and fairness in assessment calculations. This decision benefits from the multi-process design of the assessment algorithm subsystems. Even when the posture processing speed lags behind the data collection speed, this design guarantees that all image frames are processed. Additionally, the parallel operation of multiple sub-modules within the assessment algorithm subsystem plays a crucial role in maintaining real-time performance.

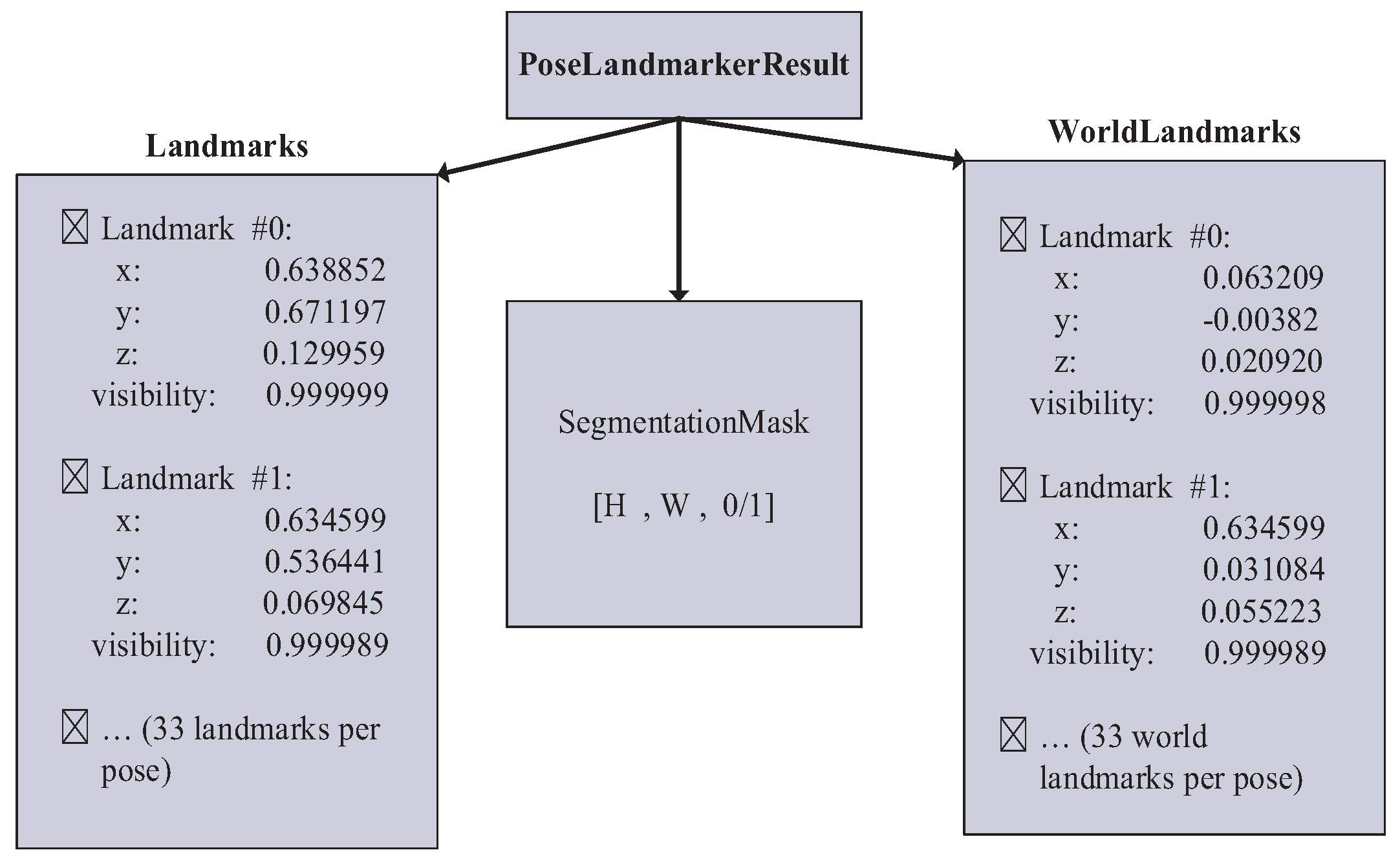

Each time the Pose Landmarker task executes a detection, it returns a

PoseLandmarkerResult object. This object contains the coordinates of each human body keypoint, providing essential data for subsequent analysis and assessment.

Figure 10 illustrates an example of the output data structure for the Pose Landmarker task. The output includes normalized coordinates (Landmarks), world coordinates (World Landmarks), and a segmentation mask for each detected human body.

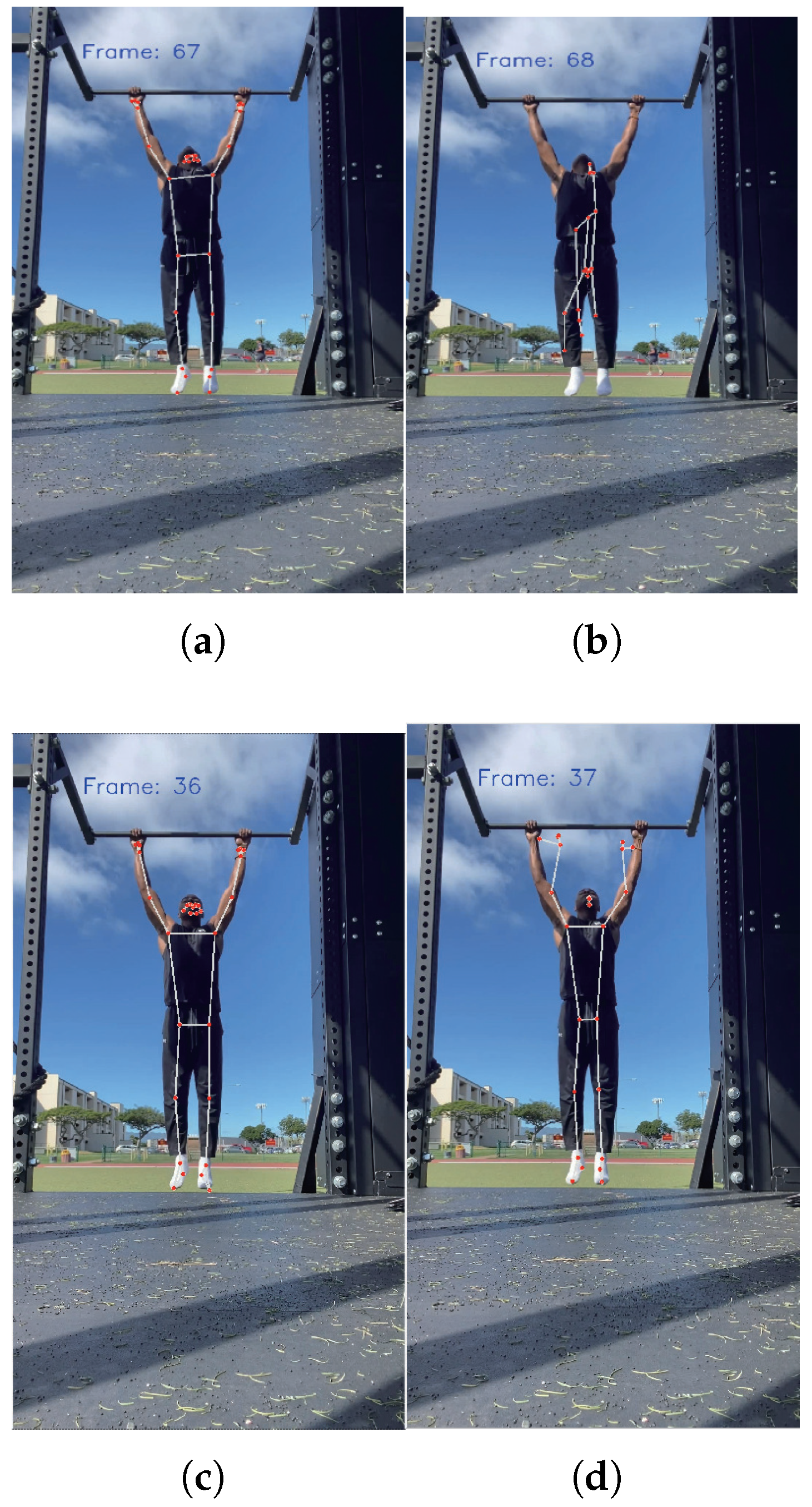

4.2. Pull-up Case

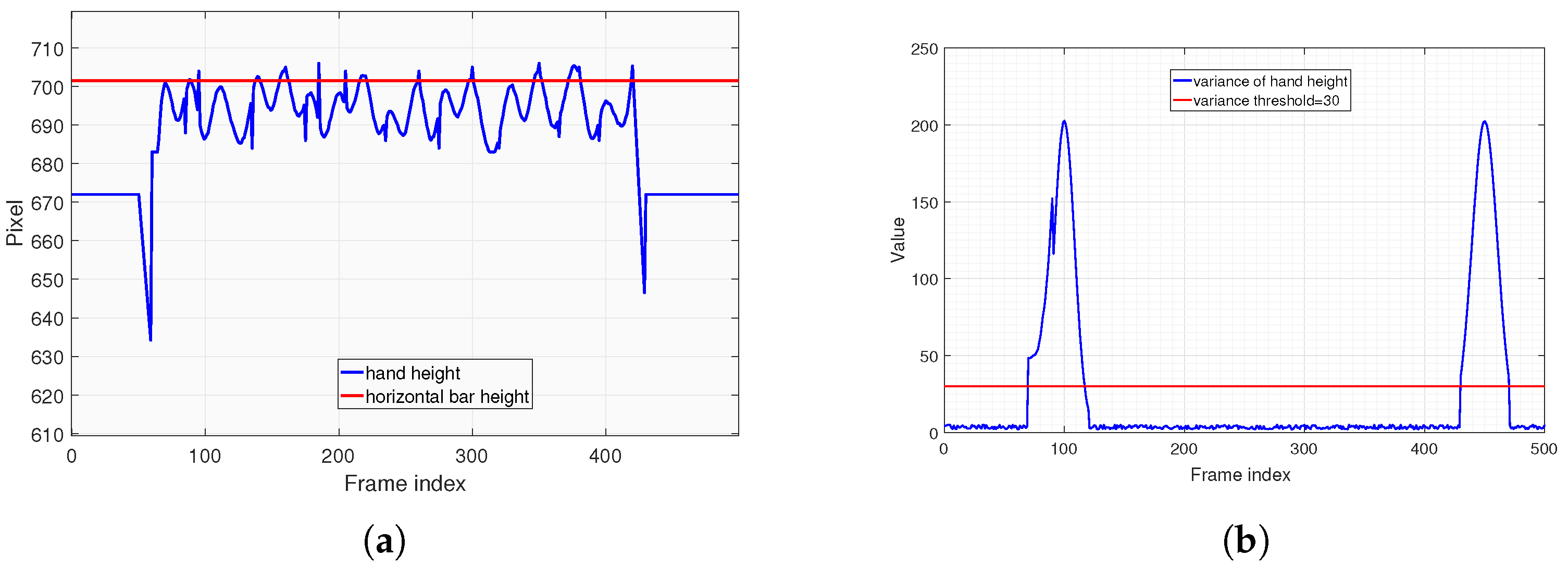

In

Figure 11(

a), the blue line represents the changes of hand height across video frames during pull-ups. It can be observed that the hand height changes slightly and remains stable during the initial and final stages. This stability occurs because the tester’s hands do not vary significantly when standing either before starting or after finishing the pull-up assessment. However, during the pull-up process, there are slight jitters and variations about hand coordinates, primarily influenced by minor hand movements and errors of body keypoints recognition. Particularly during the initial stage of pull-ups, the hand height experiences significant changes. The blue line in Fig.

Figure 11(

B) illustrates the variance of hand height values within each sliding window. It is evident that the variance remains small in frame intervals where the hands do not move significantly. The red line denotes the acceptable variance threshold (30 pixels, an empirical value selected based on the resolution of the subject’s video stream). Within the sliding window intervals that meet this variance threshold, we select the average hand height value from Fig.

Figure 11(

a) and take its maximum value (as indicated by the red line) as the height of horizontal bar.

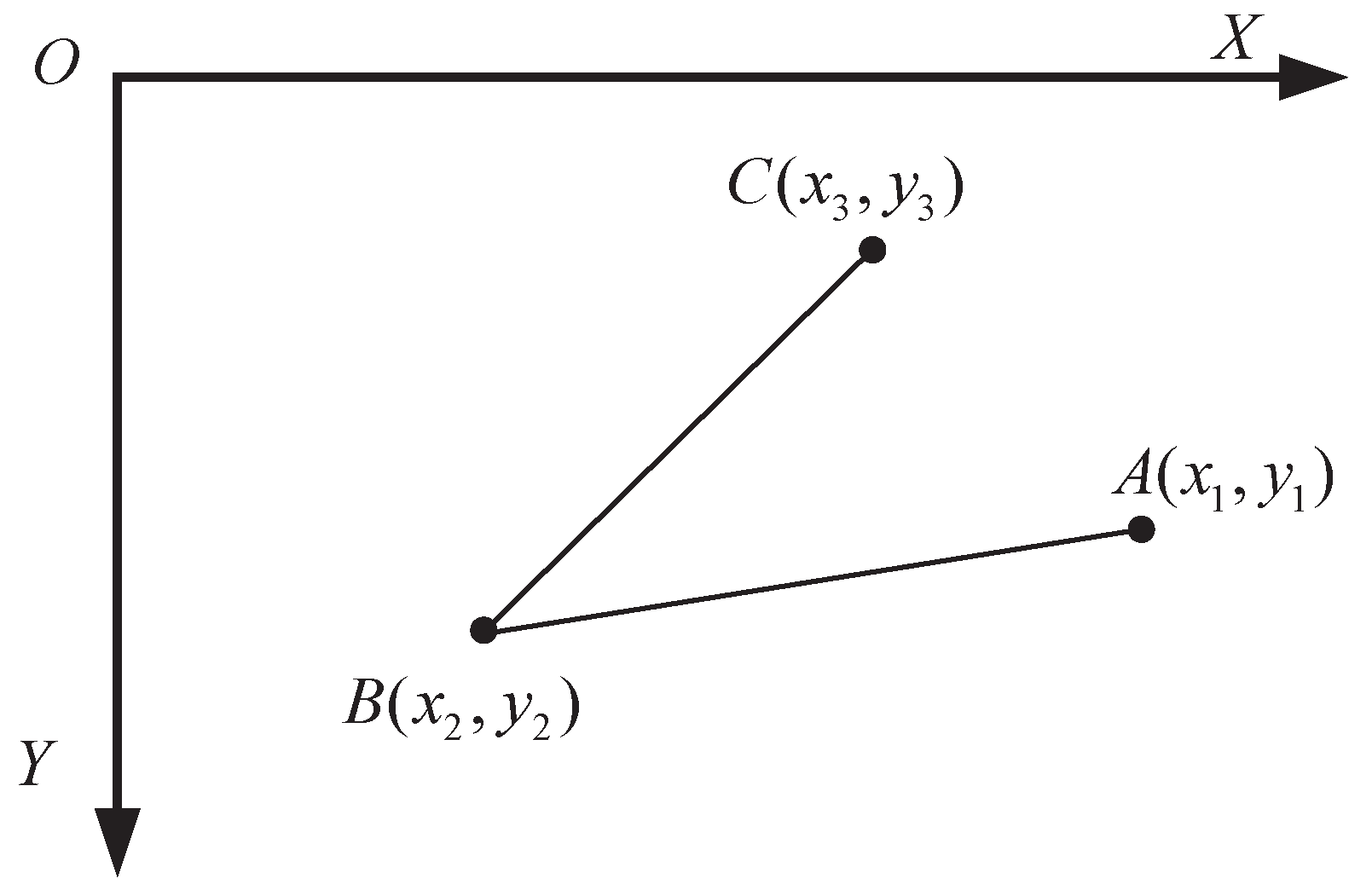

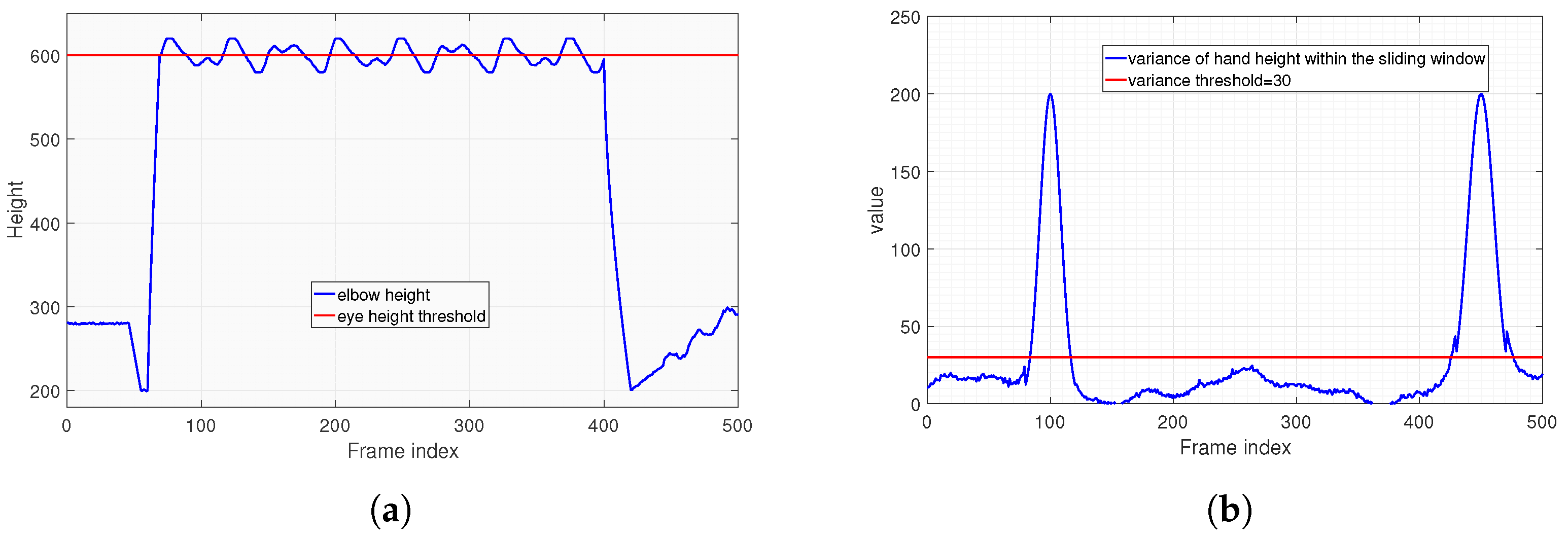

Similarly, the algorithm employs the same deductive logic to determine the eye height threshold, which will be used by the state machine judgment function

in

Table 4. Throughout the entire pull-up process, the elbow joint point displays similar data characteristics with the hand height in

Figure 11. The algorithm extracts the stable height value after the tester mounts the bar during the assessment. This value acts as the threshold that the eyes should remain below when descending to the low position of pull-up, which is referred to as the eye height threshold. The algorithm test results are presented in

Figure 12, and the deduction process will not be reiterated here.

Figure 13 presents the results of applying the frame-sequence-based joint correction and smoothing algorithm. To clearly demonstrate the execution process of the algorithm, the data results after the first-step correction are shown in

Figure 13(

a), while the final results after further smoothing following the correction are presented in

Figure 13(

b). It can be observed from

Figure 13(

a) that the errors caused by outliers are effectively suppressed after the correction. In

Figure 13(

b), after the step of smoothing, the jitter errors of the coordinates are also successfully eliminated. This demonstrates that the algorithm effectively optimizes the errors in the recognition process and restores the true motion trajectory, thus providing a solid foundation for the design of the subsequent assessment algorithm.

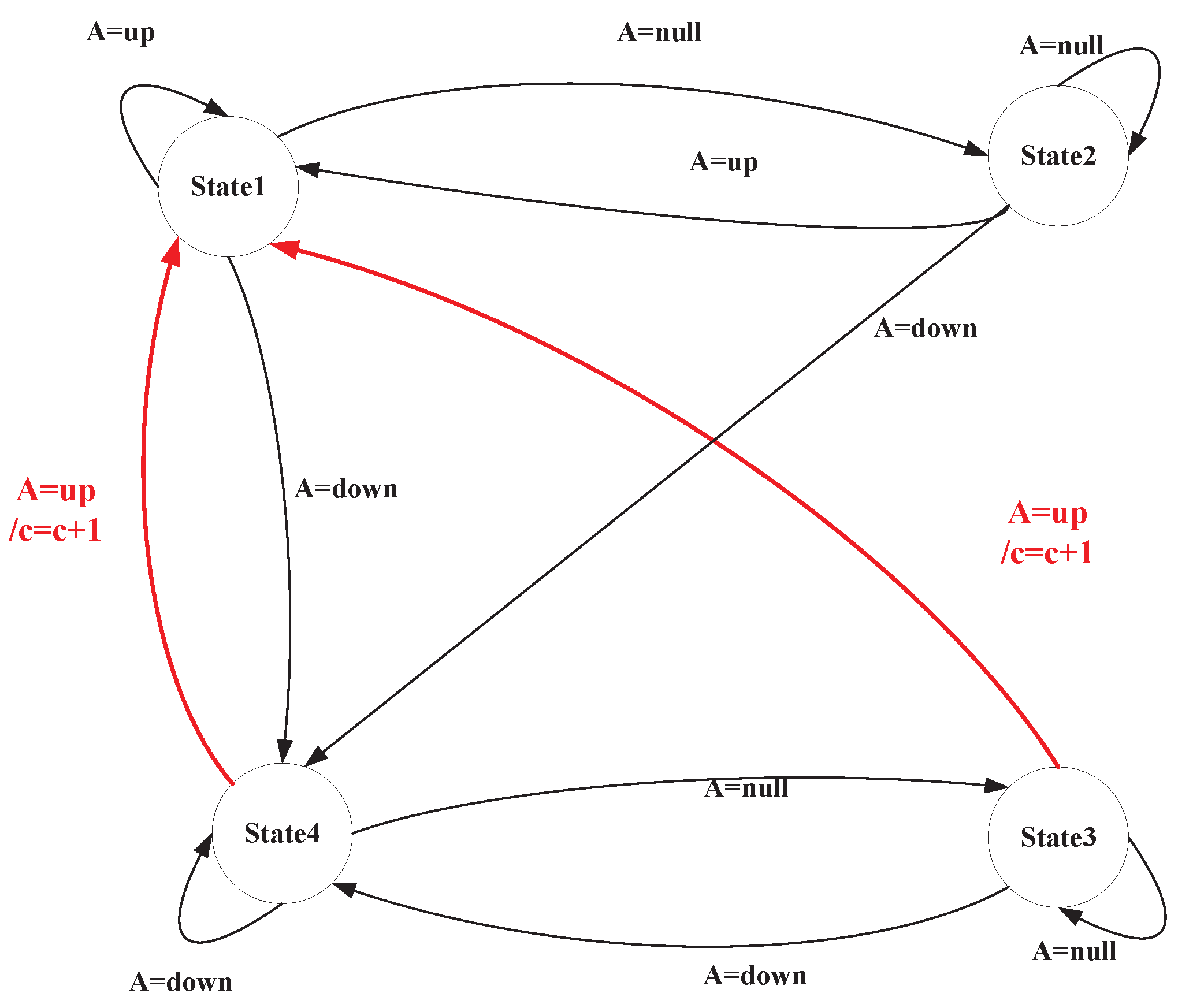

In the preceding sections, the assessment criteria for pull-ups have been analyzed in detail, and a corresponding algorithm has been developed based on these criteria. To verify the actual effectiveness of the designed algorithm, we conduct the following experimental validations.

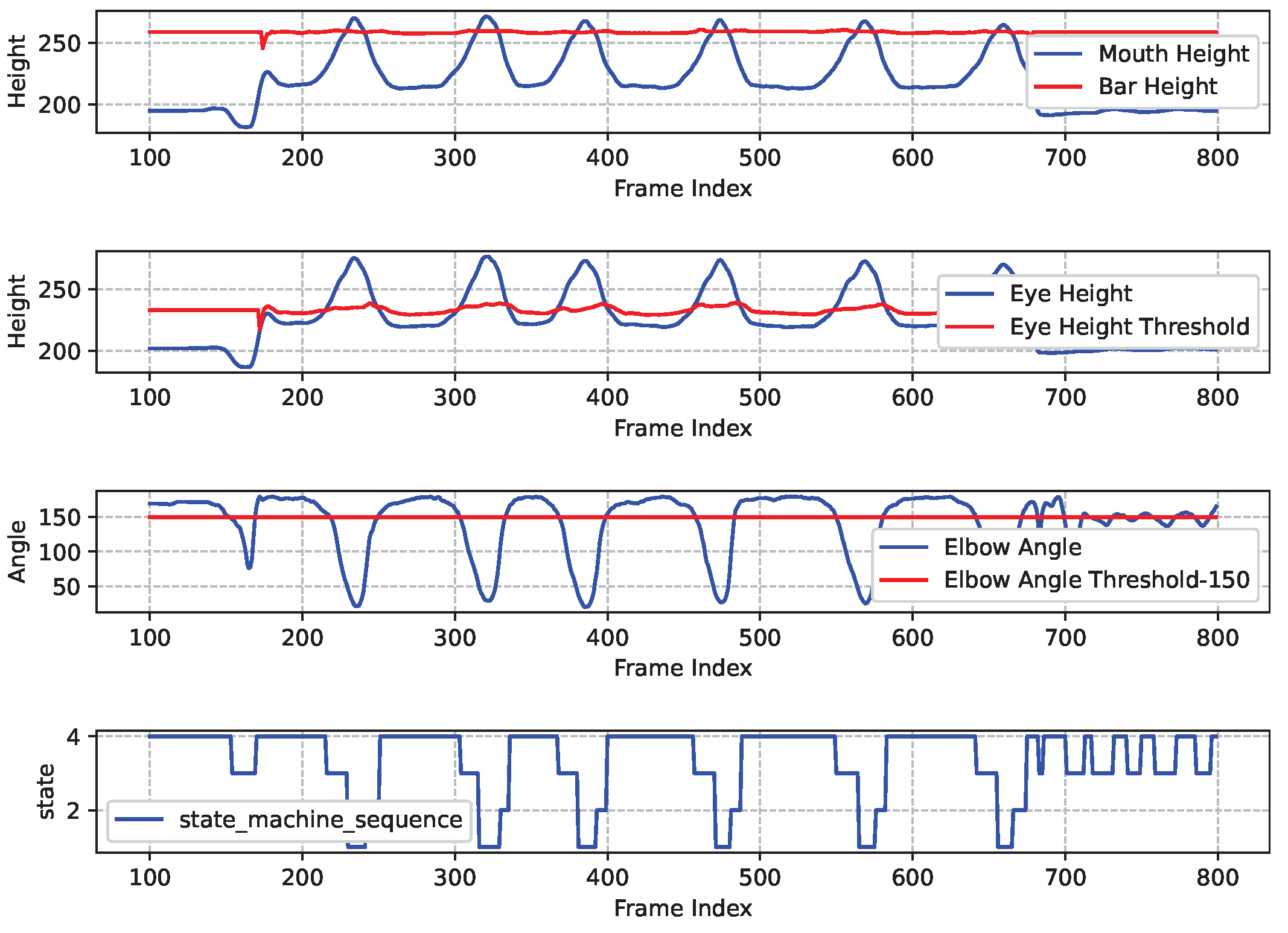

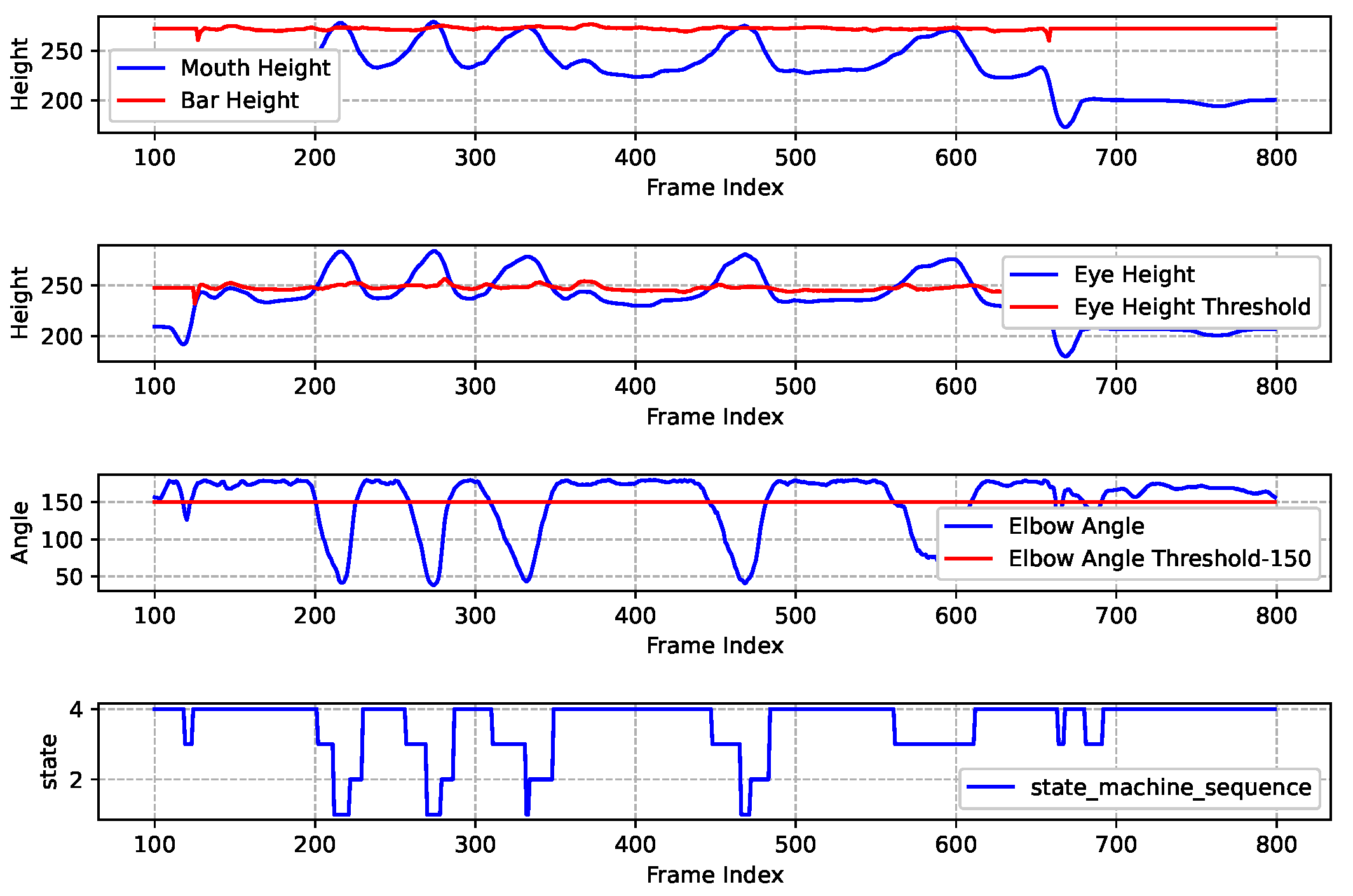

The data results graph from the standard pull-up experiment is shown in

Figure 14. The figure is divided into four sub-graphs from top to bottom, illustrating the variation of each key data point. The analysis of the experimental data is as follows.

The 1st Sub-graph: The blue line illustrates the height of the human mouth as the sequence of frames progresses, while the red line indicates the height of the horizontal bar as estimated by the horizontal bar height measurement algorithm. It is intuitively apparent that during a standard pull-up exercise, the curve representing the mouth’s height consistently intersects with the straight line denoting the height of the horizontal bar.

The 2nd Sub-graph: The blue line represents the variation of eye height throughout the frame sequence, while the red line indicates the estimated eye height threshold by

Figure 12. Similarly, the curve depicting eye height consistently intersects with the straight line representing the eye height threshold.

The 3rd Sub-graph: The blue line illustrates the variation of the angle of human elbow as the frame sequence progresses, while the red line represents the elbow angle threshold, which has been set at 150 degrees (an empirical value). This setting encourages the test-taker to keep their elbows fully extended when lowering to the low position.

The 4th Sub-graph: The blue line illustrates how the state machine varies as the frame sequence changes, allowing for observation of the overall state of human exercise and the logical counting process. Based on the sequence of the state machine in the 4th sub-graph, this experiment concludes that the test-taker performed 6 standard pull-up movements. Consequently, there were 6 transitions from State4 to State3 to State1 in the sequence.

Figure 15 shows the results of a pull-up assessment process that encounters multiple errors. The data indicates that only a few movements meets the standard assessment criteria. The main issues identified include: the mouth height not exceeding the horizontal bar during the upward pull and the eyes not being below the designated threshold height. Consequently, the final assessment score is determined to be 4, which corresponds to 4 sequences of "State4-State3-State1" in the state machine.

Then, we organized various test-takers to test the pull-up assessment algorithm, and the results are shown in

Table 10. Overall, the assessment algorithm demonstrates a relatively high accuracy rate among test-takers with high physical fitness levels. However, the recognition accuracy rate decreases slightly among ordinary college students and teachers. The overall accuracy rate of the algorithm is 96.6%, which indicates that the algorithm can effectively assess pull-ups in most cases.

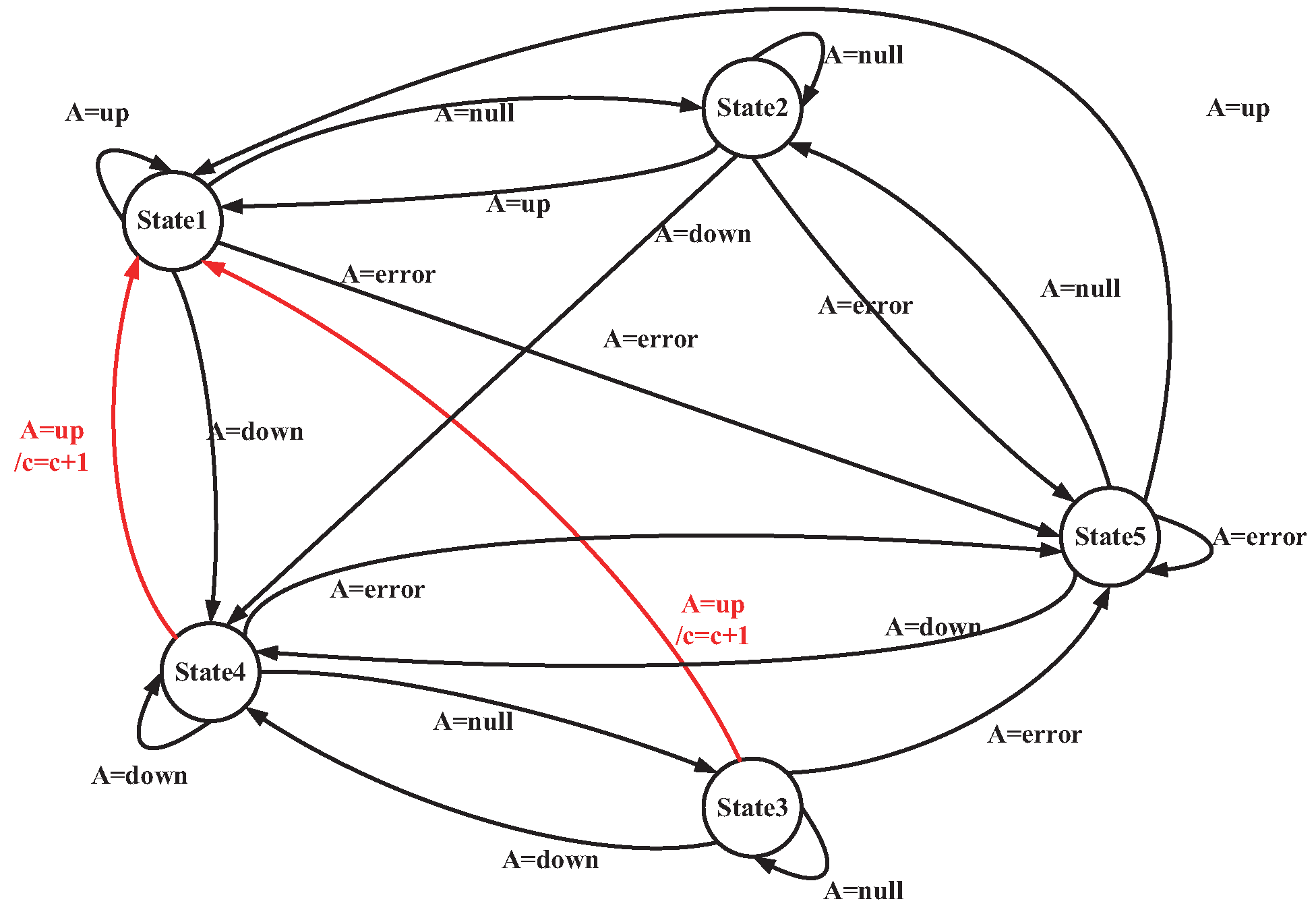

4.3. Push-up Case

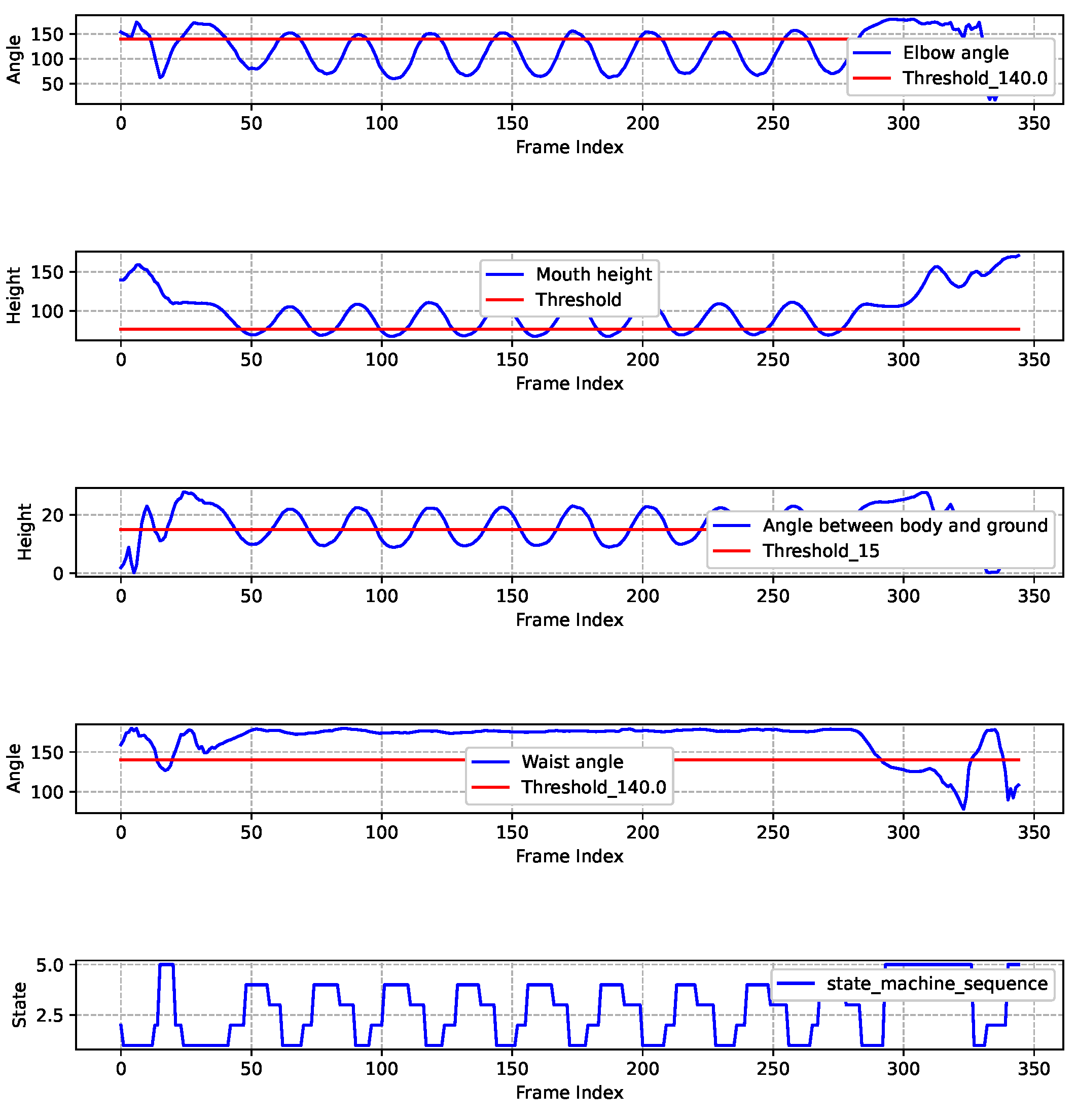

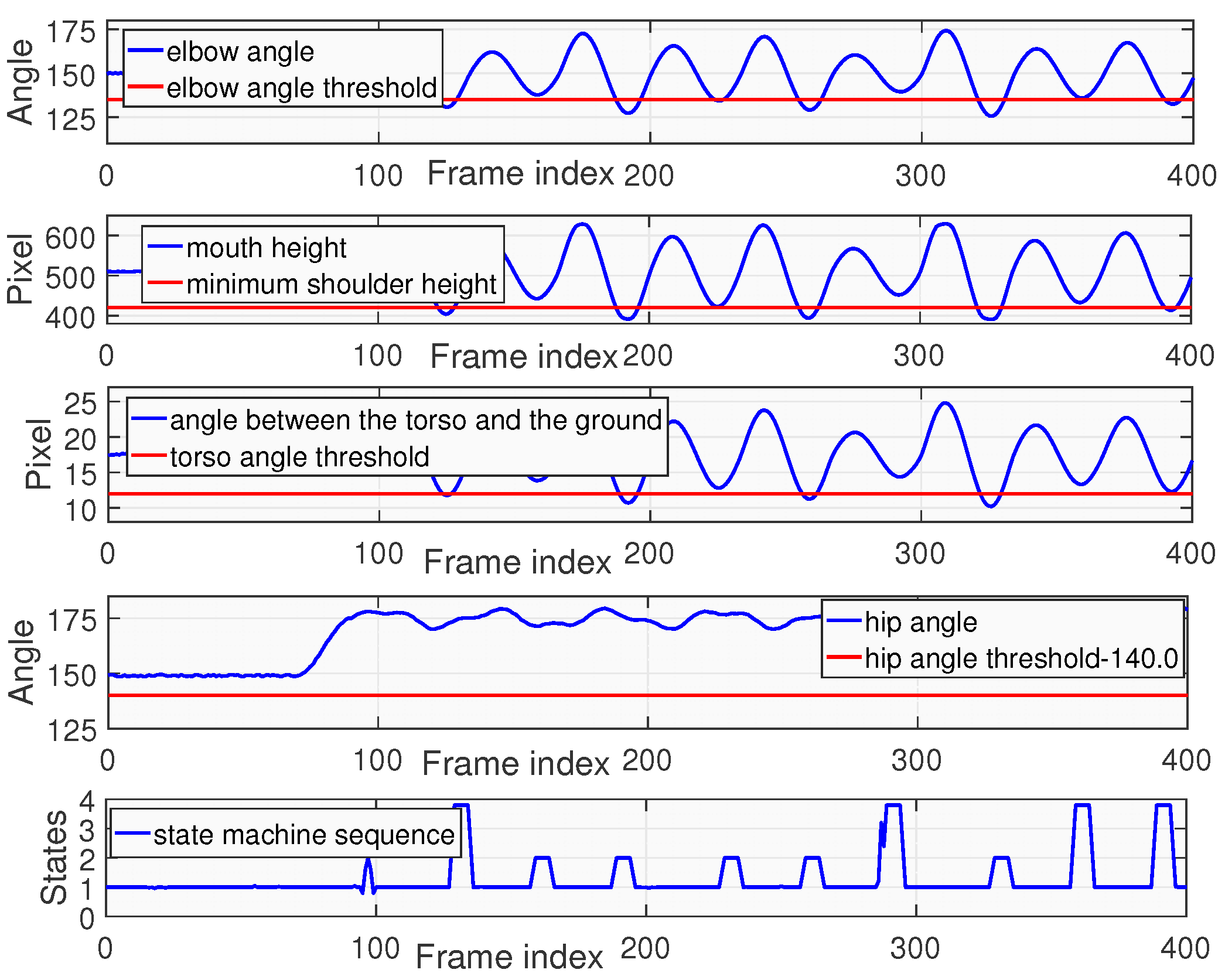

Figure 16 presents the results of a standard push-up experiment. It includes five subgraphs arranged from top to bottom, illustrating the changes of multiple key data points. The specific analysis is as follows.

The 1st Sub-graph: The blue line illustrates the variations of elbow angle of human body as the frame sequence progresses. The red line represents the elbow angle threshold which is set as 140 degrees. This empirically chosen value aims to prevent excessive bending of the elbow during the upward phase. This threshold can be adjusted at different actual conditions. When the blue line is above the red line, it indicates that the elbow angle meets the criteria for the high support position; otherwise, it does not fulfill the established standard.

Table 11.

Push-up Assessment Algorithm Accuracy Statistics.

Table 11.

Push-up Assessment Algorithm Accuracy Statistics.

| Tester |

Actual Repetitions/Rep |

Detected Repetitions/Rep |

Algorithm Counting Accuracy Rate /% |

| Ordinary Student |

23 |

21 |

91.0 |

| Teacher |

34 |

33 |

97.0 |

| PE Student 1 |

40 |

39 |

97.5 |

| PE Student 2 |

45 |

44 |

97.8 |

| Soldier |

50 |

50 |

100 |

| Summary |

192 |

187 |

97.4 |

The 2nd Sub-graph: The blue line illustrates the variation of mouth height, indicating the position of the tester’s mouth relative to the ground during push-ups. The mouth height fluctuates throughout the movement. The red line represents the minimum shoulder height throughout the entire push-up process, which can be different for different individuals. A necessary condition for entering the low support state during push-ups is that the mouth height must be lower than the minimum shoulder height.

The 3rd Sub-graph: The blue line illustrates the variation of the angle between torso and ground, while the red line indicates a threshold of 15 degrees.

The 4th Sub-graph: The blue line illustrates the variation of waist angle. The red line indicates the threshold which is set at 140 degrees. The purpose of this threshold is to ensure that the tester maintains a straight body.

The 5th Sub-graph: The blue line illustrates the changes of the state machine sequence. When the blue line of the state machine experiences a transition from State4 to State3 to State1, it signifies that the tester has successfully completed a standard push-up movement. During the movement, any non-compliant action will trigger State5. Finally, it can be observed from the figure that the result of this push-up assessment is 9.

Figure 17 shows the assessment results of non-standard push-up. In this experiment, the mouth height consistently failed to reach to the required threshold for the low-position state, and the torso angle also did not meet the standard. Therefore, in the state machine sequence, only 4 transitions from State4 to State3 to State1 happen. Thus, the final score of this tester is 4.