1. Introduction

For decades, the teaching of statistics in higher education has been dominated by a traditional, instructor-centered model. In this paradigm, knowledge is often treated as a static commodity, something to be transmitted from expert to novice through lectures, textbooks, and tightly structured exercises. As

Sperber and Wilson (

1986) observed, many students perceive knowledge as a product to be delivered, with the lecturer serving as the vehicle of transmission. Instruction, in this view, becomes a delivery mechanism, and “good teaching” is equated with clear exposition and exam preparation rather than deep engagement or conceptual understanding.

This transmissive model has been particularly entrenched in statistics education, where the complexity of abstract concepts, mathematical formalism, and software-based computation often leads instructors to adopt a didactic approach. Students are typically guided through a linear sequence of topics—descriptive statistics, probability, hypothesis testing, regression—each accompanied by formulae, worked examples, and problem sets. While this approach may foster procedural fluency, it frequently fails to cultivate statistical reasoning, critical thinking, or the ability to apply concepts in unfamiliar contexts

Loveland (

2014);

Tishkovskaya and Lancaster (

2012).

In response to these limitations, reform efforts have advocated for more active, student-centered pedagogies. Constructivist and inquiry-based approaches, for instance, emphasize the learner’s role in constructing meaning through exploration, collaboration, and reflection

Lee and Ban (2022);

Libman (2010). These methods have shown promise in enhancing engagement and conceptual understanding, yet their implementation remains uneven, and their effectiveness is often constrained by resource limitations, instructor preparedness, and curricular rigidity.

The recent emergence of generative artificial intelligence (genAI) tools such as ChatGPT, Julius AI, and Claude offers a new frontier for reimagining statistics education. These tools can generate code, simulate data, explain statistical procedures, and provide instant feedback, effectively acting as responsive learning partners. Early studies suggest that generative AI can support exploratory learning by enabling students to pose questions, test ideas, and iterate through problem-solving processes in real time

Hannah and Chernobilsky (2024);

Schwarz (2025).

This paper seeks to explore how genAI can be integrated into statistics education to support exploratory learning and foster deeper conceptual understanding. Specifically, it investigates how AI tools can be used not only to facilitate exploration of statistical concepts and coding practices, but also to promote curiosity, iteration, and critical thinking, key attributes of meaningful learning. The study is grounded in constructivist and inquiry-based learning theories and presents a series of proposed case studies that illustrate how AI can be used to scaffold student autonomy and engagement.

The central question guiding this inquiry is: How can generative AI be used to support exploratory learning in statistics education, and what pedagogical frameworks and practical strategies best facilitate its integration into teaching and learning? In addressing this question, the paper aims to fill a critical gap in the literature. While there is growing interest in the use of AI in education, few studies

Prandner et al. (

2025);

Schwarz (

2025);

Wahba et al. (

2024) have examined its role in fostering exploratory learning in statistics, particularly through theoretically grounded, practice-oriented scenarios.

By articulating a vision for AI-enhanced statistics education, this paper contributes to the evolving discourse on digital pedagogy and offers practical insights for educators seeking to harness the potential of generative AI in ways that are pedagogically sound, ethically responsible, and aligned with the goals of 21st-century learning.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Constructivist Foundations and Principles

The foundations of constructivist learning theory are deeply embedded in the history of educational thought, challenging the long-dominant behaviorist and information-processing paradigms. The intellectual roots of constructivism can be traced back to the work of several key figures who conceptualized learning not as a passive reception of information but as an active, meaning-making process. The most influential of these was the Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget, who through his extensive studies on child development, proposed that learners build mental structures, or "schemas", to make sense of the world

Piaget (

2013). His work introduced the concepts of assimilation (integrating new experiences into existing schemas) and accommodation (modifying existing schemas to incorporate new information), highlighting a continuous, individualized process of cognitive adaptation. A distinctly different, though equally influential, perspective was offered by the Soviet psychologist Lev Vygotsky, who emphasized the sociocultural dimensions of learning

Vygotsky (

1978).

In contrast to Piaget’s focus on the individual, Vygotsky’s social constructivism posited that higher mental functions are co-constructed through social interaction and dialogue, particularly with more knowledgeable others. His concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) introduced the idea of scaffolding, whereby a learner receives support to complete tasks that are just beyond their independent capability, a process intrinsically tied to culture and language. The synthesis of these ideas across the 20th century provided the theoretical bedrock for a student-centered approach to learning, moving away from the transmissive model where knowledge is simply delivered from instructor to student

Glasersfeld (

1995).

At its heart, constructivism rests on several fundamental principles that contrast sharply with traditional instructional methods. Firstly, learning is an active process. Knowledge is not passively absorbed but is actively built by the learner. This stands in direct opposition to the model observed by authors like

Barr and Tagg (

1995), where knowledge is viewed as a "commodity" to be transmitted. Secondly, prior knowledge is foundational. A learner’s existing beliefs, experiences, and cultural background form the essential foundation for all new learning. Effective instruction, therefore, must elicit and build upon this prior understanding. As argued by both

Ashburn and Floden (

2006);

Bransford et al. (

2000), ignoring or failing to address these preconceptions can lead to superficial learning or the reinforcement of misconceptions. Thirdly, learning is a social process. As

Vygotsky (

1978) demonstrated, dialogue, collaboration, and interaction with peers and educators are critical for refining and deepening understanding. Fourthly, learning is contextual. Knowledge is not a set of isolated, abstract facts but is inextricably tied to the context in which it was learned. Meaningful learning occurs when concepts are explored in authentic, real-world scenarios. Finally, motivation is integral to learning. Constructivist approaches typically foster intrinsic motivation by engaging learners in authentic, personally relevant tasks that stimulate curiosity and intellectual engagement

Dweck (

2006).

2.2. The Evolving Role of the Educator in a Constructivist Context

In the constructivist classroom, the educator’s role undergoes a significant transformation from that of a knowledge dispenser to a facilitator, guide, and orchestrator of learning experiences. Instead of delivering lectures, the instructor creates a rich learning environment that prompts inquiry, exploration, and collaboration. This shift involves several key responsibilities. The educator must first diagnose and address students’ prior knowledge, using formative assessment to uncover existing conceptions, including potential misconceptions. Second, they must design authentic, problem-based tasks that challenge students to apply concepts in meaningful ways. These tasks often serve as the catalysts for inquiry and knowledge construction. Third, the educator provides scaffolding to support students as they navigate complex challenges, offering guidance and resources at the right moment to help them advance through their Zone of Proximal Development

Vygotsky (

1978). This involves asking probing questions rather than simply providing answers. Finally, the constructivist educator fosters a collaborative learning community, encouraging students to learn from each other through discussion, peer teaching, and group projects. This shift from instructor-centered to student-centered pedagogy is central to reform efforts in statistics education

Cobb (

1999).

2.3. Examples of Constructivist Applications in Education

The principles of constructivism have been applied across various educational fields, leading to innovative pedagogical strategies. In general education, inquiry-based learning is a prime example, where students are encouraged to pose questions, investigate topics, and construct their own understanding through research and observation

Hmelo-Silver et al. (

2007). In problem-based learning, students work in groups to develop solutions to real-world problems, with the process of problem-solving serving as the core learning activity

Barrows (

1996). In the sciences, constructivist approaches often involve hands-on laboratory work where students design experiments and interpret their own data, moving beyond simple recipe-following

Driver et al. (

1994). Specifically within statistics education, constructivist reforms have promoted data-centric approaches, encouraging students to start with real-world questions and use data exploration to develop their understanding of statistical concepts, rather than beginning with abstract formulas

Cobb (

1999). Technology has long been used to support these approaches, from statistical software to online simulations, but generative AI offers a new, and more powerful, technological tool for facilitating this kind of exploratory, student-driven inquiry

Duzenlı (

2018).

2.4. Leveraging Generative AI for Exploratory Learning in Statistics Education

The emergence of genAI offers a novel and powerful opportunity to revitalize statistics education by providing an unprecedented capacity to support exploratory learning, in line with constructivist principles. Tools like ChatGPT and others can generate code, simulate data, explain statistical procedures, and provide instant feedback, acting as responsive, always-available learning partners. This capability directly addresses the limitations of traditional, transmissive pedagogy in statistics, which often fails to cultivate statistical reasoning and critical thinking

Garfield and Ben-Zvi (

2007);

Snee (

1993).

Specifically, genAI can be used in several ways to enhance exploratory learning in statistics education at the tertiary level.

Scaffolding Data Exploration

Students can use genAI to generate synthetic datasets based on specific criteria or explore patterns within existing data. For example, a student could ask Julius AI to "create a dataset simulating the relationship between study hours and exam scores, including some outliers." This allows for unconstrained experimentation and hypothesis-testing without the complexity of locating or cleaning real-world data.

Facilitating Code Generation and Debugging

For students learning statistical programming languages like R or Python, genAI can generate and explain code snippets for specific analyses. A student might prompt an AI with, "Write R code to perform a multiple regression analysis and visualize the residuals." This lowers the barrier to entry for coding, allowing students to focus on statistical interpretation rather than syntax memorization, thereby supporting a more exploratory, iterative coding process

Vukojičić and Krstić (

2023).

Engaging in Socratic Dialogue

genAI tools can be configured to act as an AI tutor that engages students in Socratic questioning, probing their understanding of statistical concepts. Rather than simply providing an answer, the AI can ask, "Why did you choose that particular hypothesis test?" or "What are the assumptions of this model, and why are they important?" This promotes metacognitive reflection and forces students to justify their reasoning

Fakour and Imani (

2025).

Simulating and Explaining Complex Concepts

Generative AI can create interactive simulations or vivid explanations of complex statistical ideas, such as the Central Limit Theorem or sampling distributions. Students could prompt an AI to "Explain the Central Limit Theorem using a story with examples," providing a personalized explanation tailored to their learning style.

These applications directly foster the constructivist principles of active learning, social learning (as a dialogue partner), and contextual learning. They empower students to be curious, ask questions, test ideas, and iterate, transforming them from passive consumers of statistical knowledge into active constructors of their own understanding

Vygotsky (

1978).

3. Cases

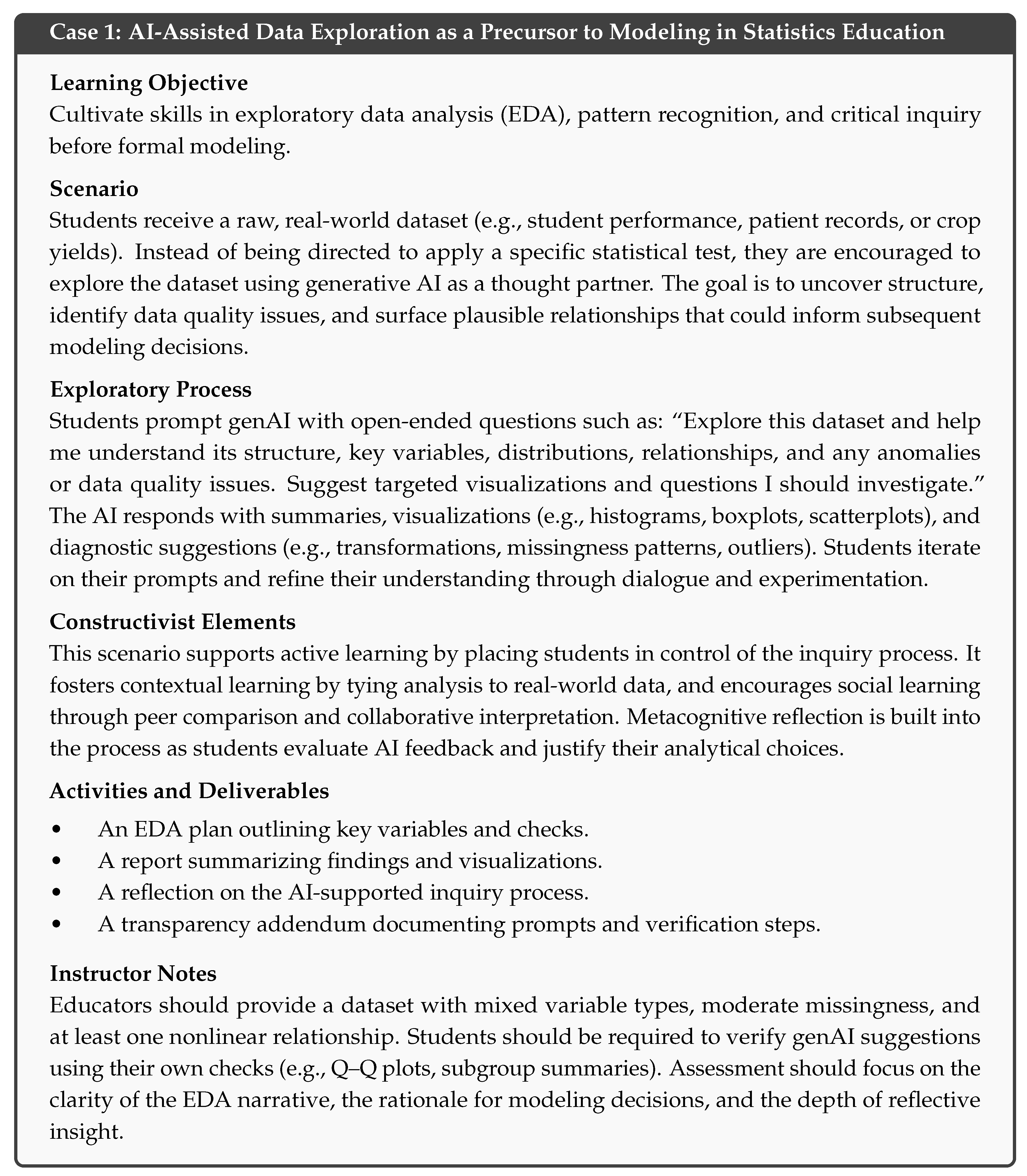

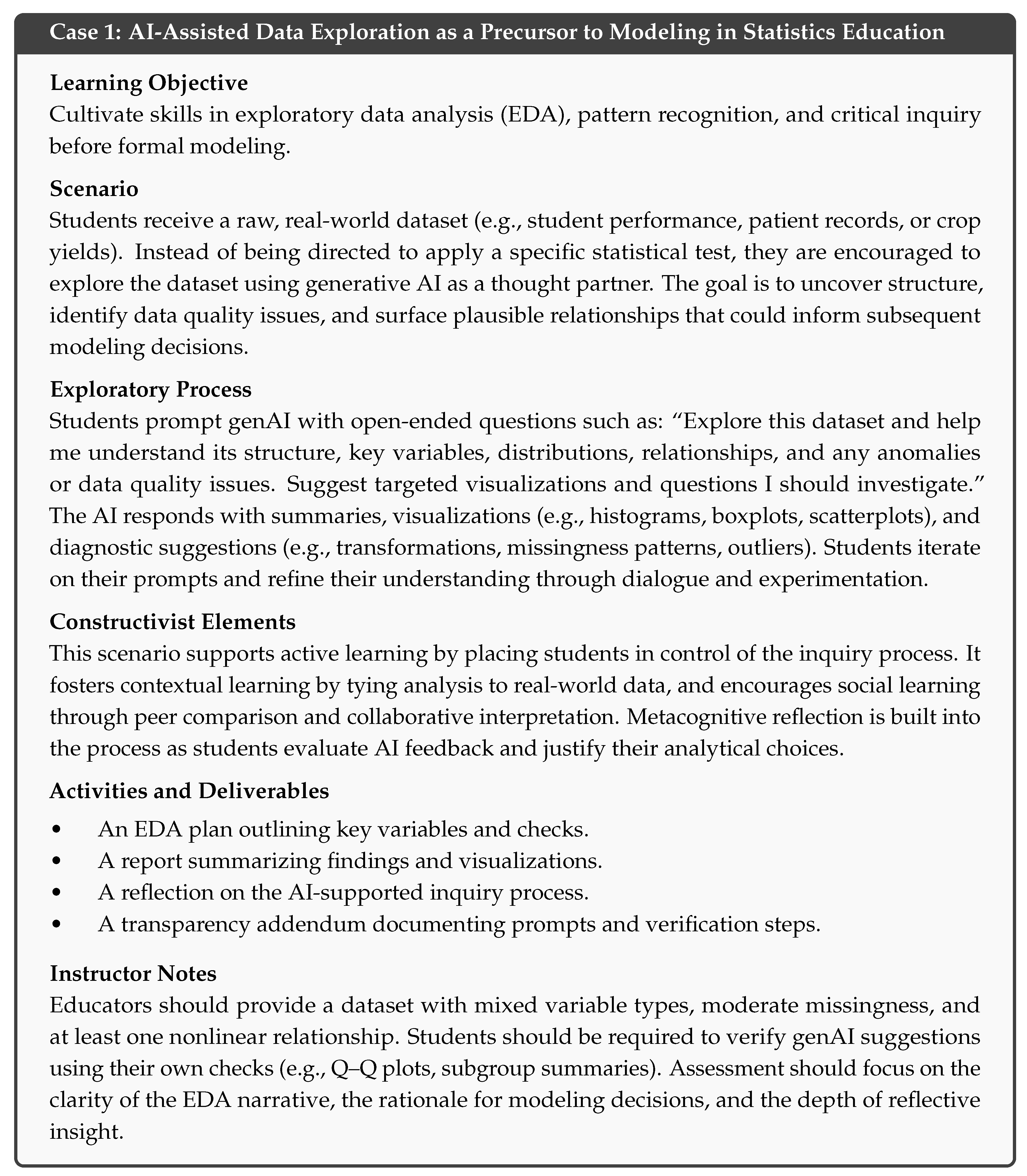

3.1. Case 1: AI-Assisted Data Exploration as a Precursor to Modeling in Statistics Education

The first scenario illustrates how generative AI can support exploratory data analysis as a foundational step in statistical modeling. It emphasizes student autonomy and inquiry before formal statistical procedures are introduced.

This case sets the stage for deeper reasoning by encouraging students to uncover structure and relationships in data. The next scenario builds on this by guiding students through statistical test selection using Socratic dialogue.

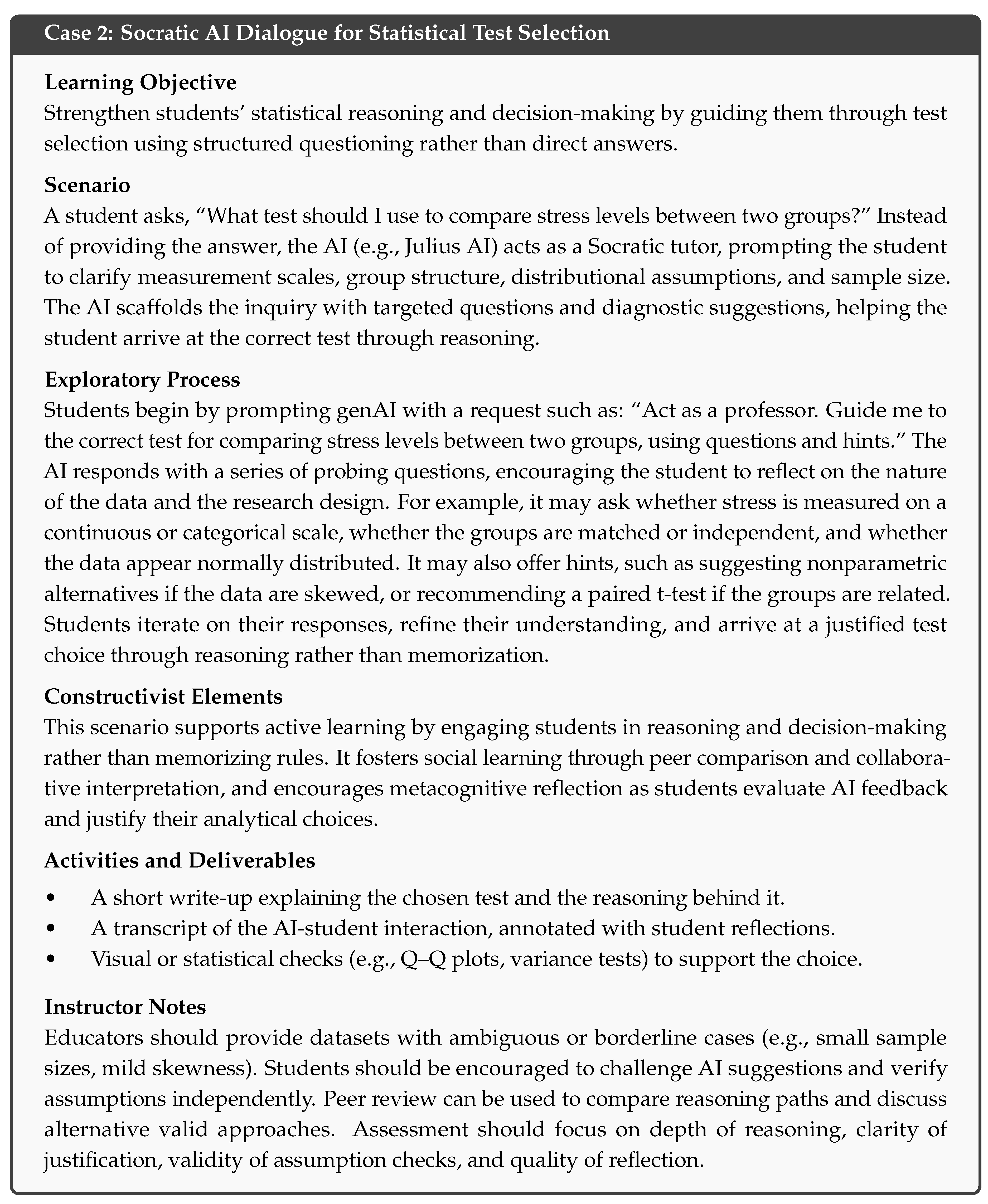

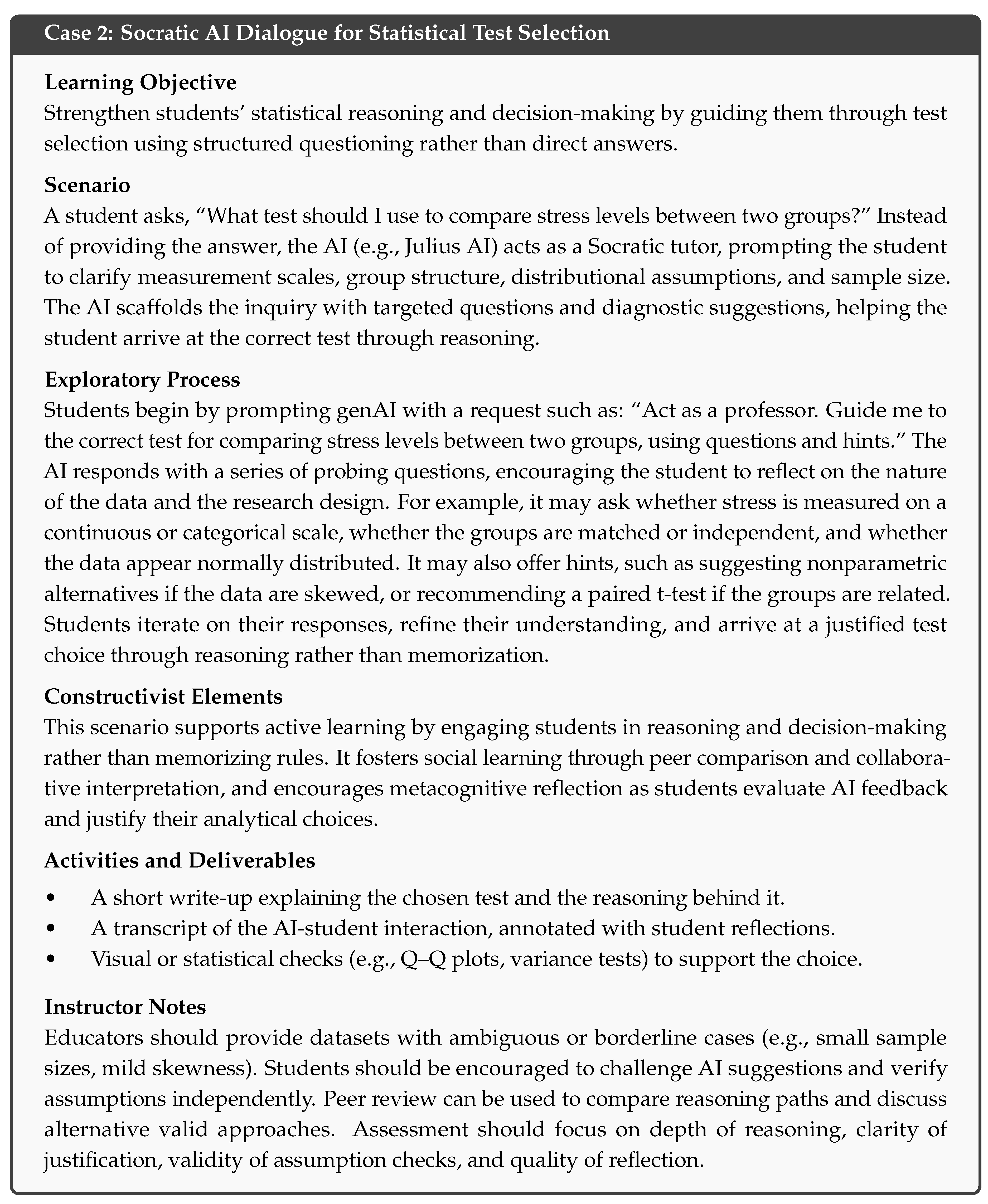

3.2. Case 2: Socratic AI Dialogue for Statistical Test Selection

Building on the exploratory mindset developed in Case 1, the second scenario shifts focus to statistical decision-making. It demonstrates how AI can scaffold reasoning through structured questioning.

By prompting students to justify their choices, this case fosters critical thinking and metacognitive awareness. The following scenario explores how AI can clarify abstract statistical concepts through personalized explanations.

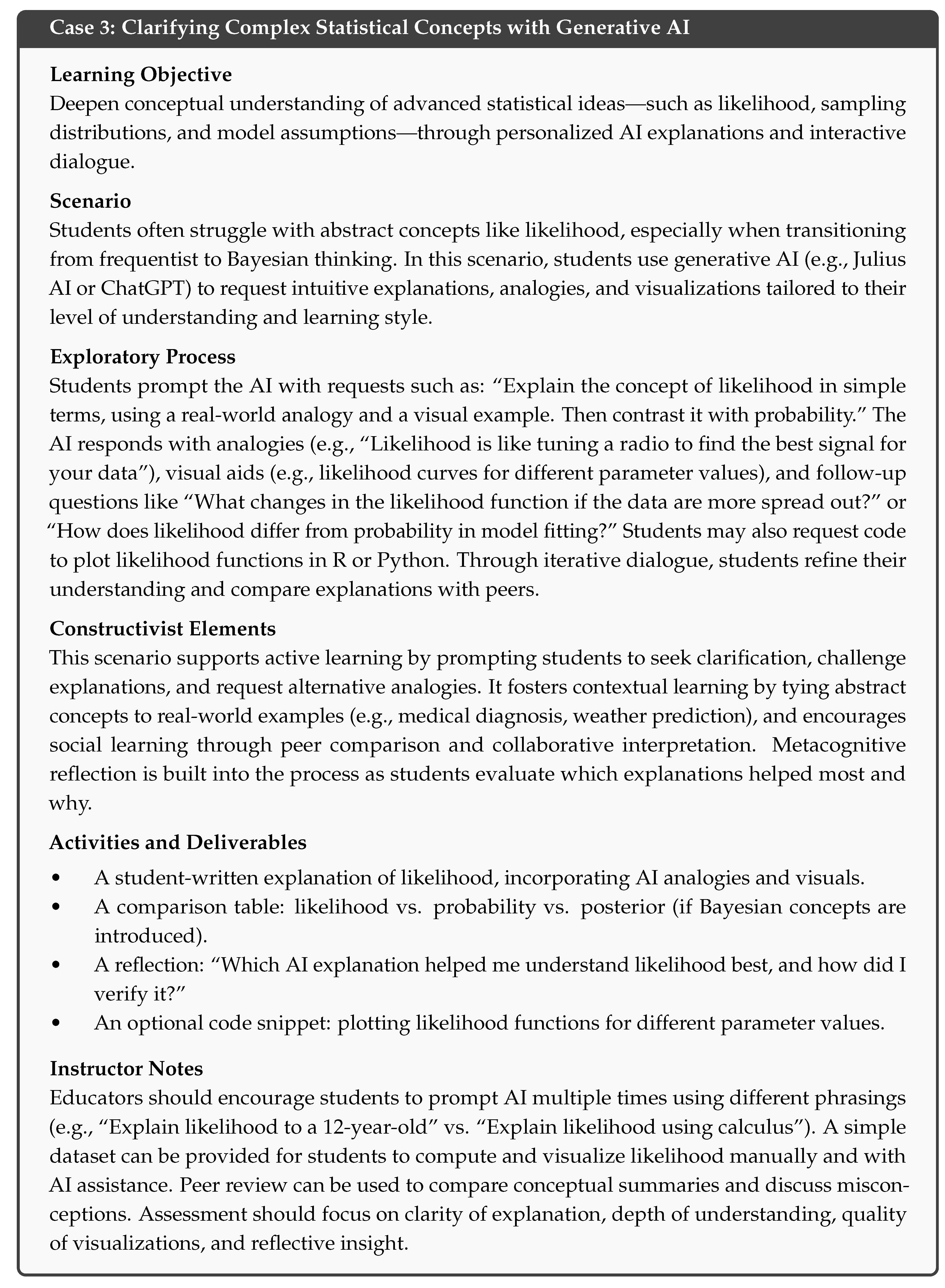

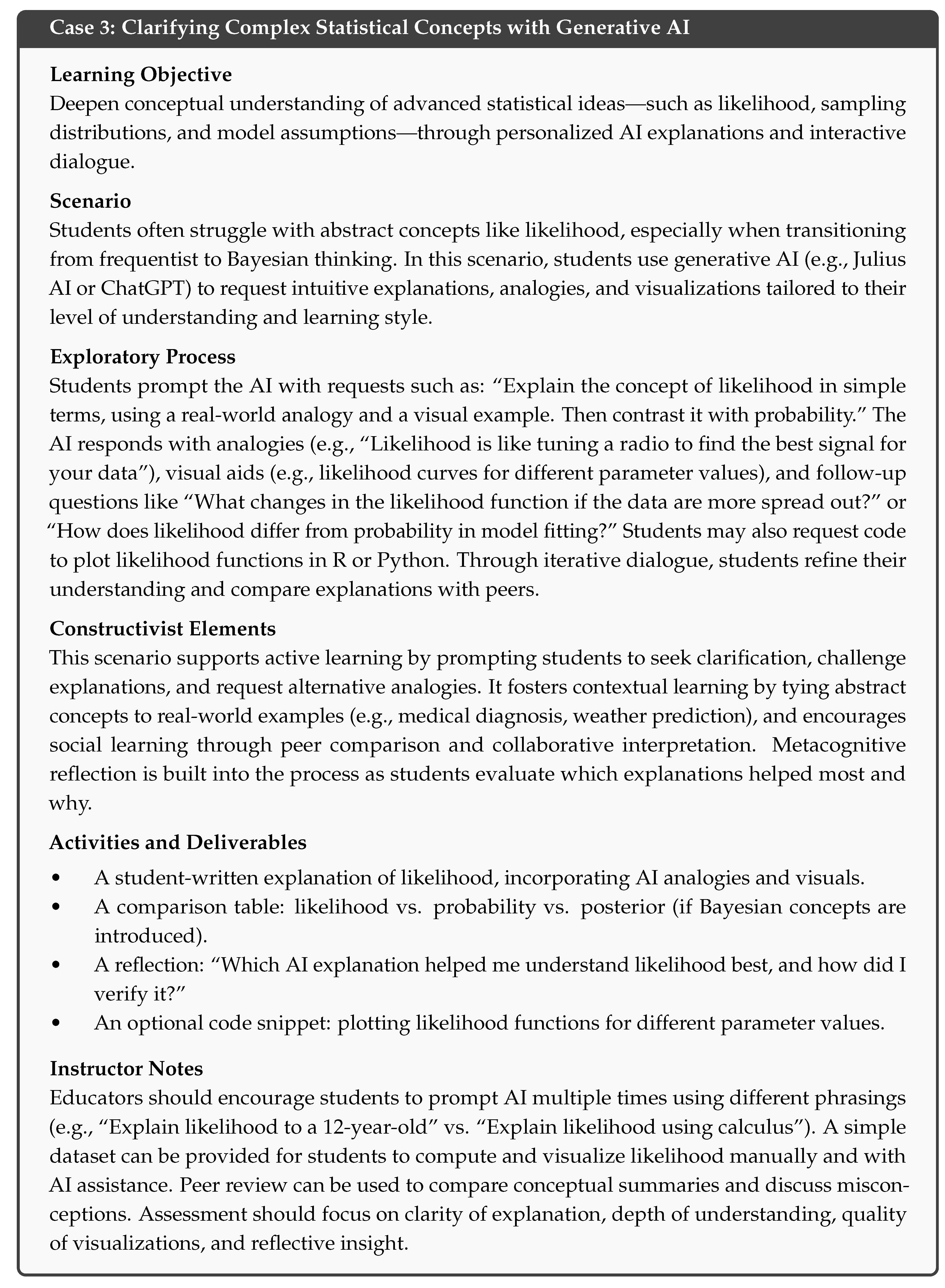

3.3. Case 3: Clarifying Complex Statistical Concepts with Generative AI

The third scenario addresses a common challenge in statistics education: grasping abstract concepts like likelihood and probability. It shows how AI can personalize explanations to support conceptual understanding.

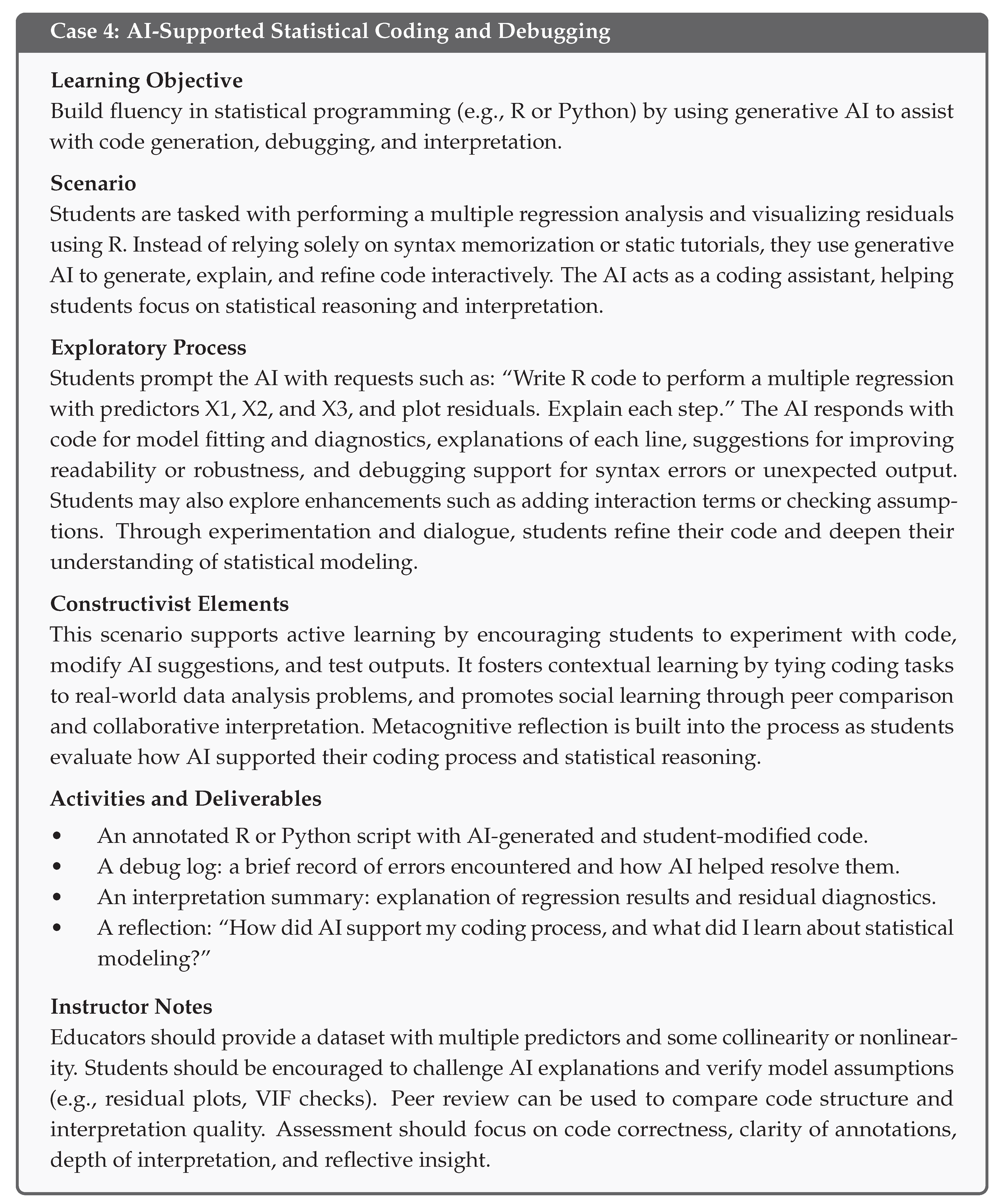

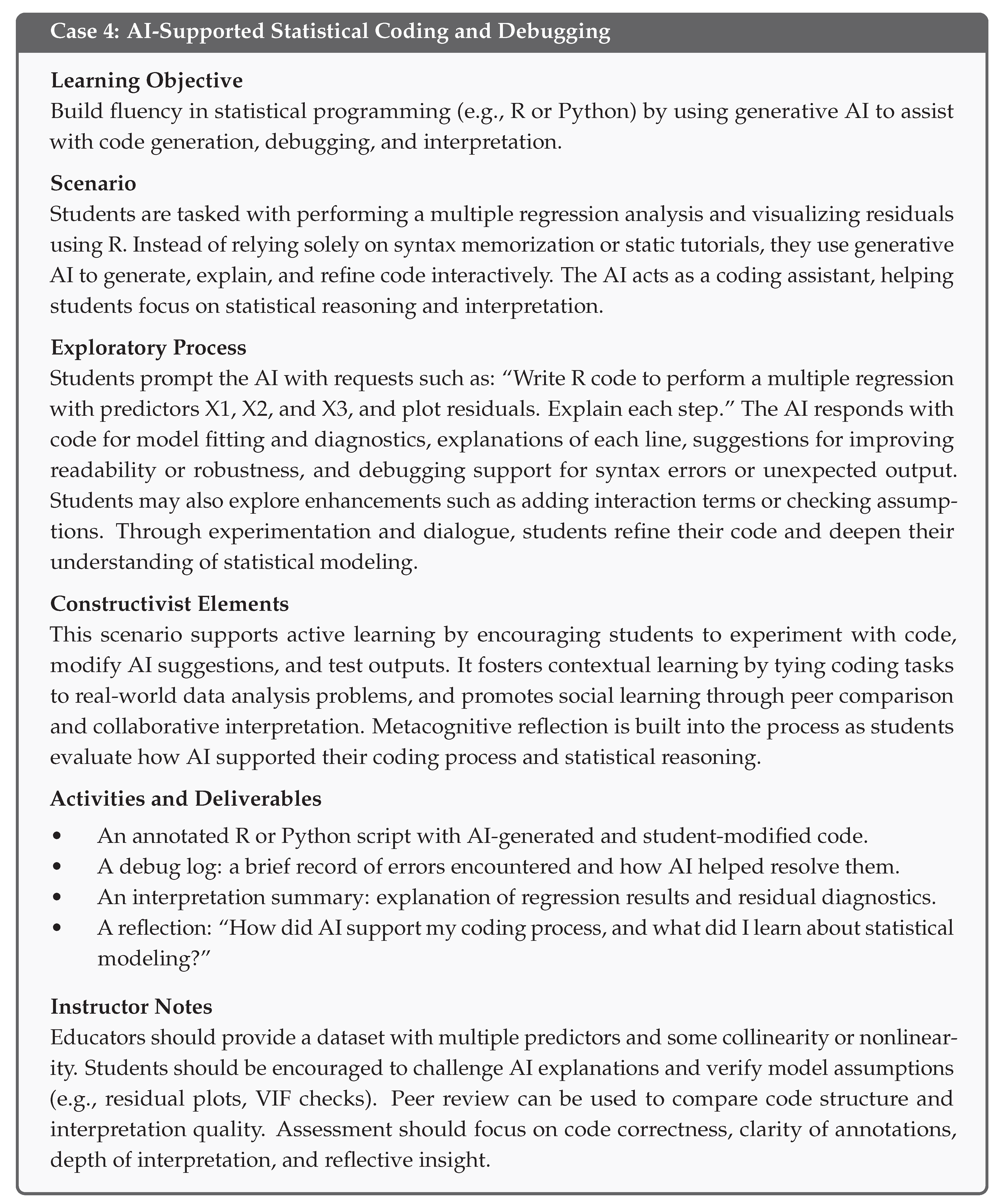

3.4. Case 4: AI-Supported Statistical Coding and Debugging

The fourth and final scenario emphasizes the role of AI in supporting statistical programming. It encourages students to engage with code iteratively and interpret results meaningfully.

Table 1 summarizes the four proposed case scenarios, highlighting the core student activities, intended learning outcomes, and the constructivist principles each scenario embodies. The table serves as a pedagogical map, illustrating how generative AI can be used to scaffold exploratory learning in statistics education. While no actual AI tools were deployed in practice, the scenarios are designed to simulate realistic interactions and prompting strategies that educators and students can adapt to their contexts. Each case aligns with key tenets of constructivism—active engagement, contextual relevance, social interaction, and reflective inquiry offering a flexible framework for integrating AI-enhanced learning into statistics curricula.

4. Discussion

The case scenarios presented in this paper illustrate how generative AI can be strategically integrated into statistics education to foster exploratory learning, consistent with the principles of constructivist pedagogy. Each scenario demonstrates a shift away from passive reception of knowledge toward active engagement, inquiry, and reflection—hallmarks of meaningful learning.

In the first case, students engage in exploratory data analysis with AI as a responsive partner. This aligns with Piaget’s notion of learners constructing knowledge through interaction with their environment and Vygotsky’s emphasis on scaffolding within the Zone of Proximal Development. The AI prompts students to examine distributions, identify anomalies, and consider transformations, thereby supporting cognitive adaptation and contextual understanding.

The second case exemplifies Socratic dialogue, where AI guides students through test selection by asking clarifying questions. This approach encourages metacognitive reflection and reinforces the constructivist view that learning is a process of sense-making rather than answer-seeking. Students are not merely told what to do; they are led to reason through the problem, fostering autonomy and deeper conceptual grasp.

In the third case, AI is used to demystify abstract statistical concepts such as likelihood. By offering analogies, visualizations, and tailored explanations, AI supports differentiated learning and helps bridge the gap between formal theory and intuitive understanding. This personalization of instruction reflects the constructivist emphasis on prior knowledge and individual meaning-making.

The fourth case highlights how generative AI can assist with statistical coding and debugging. Students use AI to generate, refine, and interpret code, allowing them to focus on higher-order thinking rather than procedural syntax. This supports the development of statistical reasoning and promotes iterative learning through experimentation and feedback.

These scenarios collectively underscore a transformation in the educator’s role. In the era of generative AI, the teacher becomes less of a content deliverer and more of a learning architect. Educators design tasks that leverage AI’s capabilities for simulation, explanation, and feedback, while guiding students in critically evaluating AI outputs. This shift requires instructors to foster ethical awareness, support reflective practice, and ensure that students remain active agents in their learning journey

Baidoo-Anu and Ansah (

2023).

Rather than grading rote answers, educators assess students’ reasoning, their ability to justify choices, and their engagement with AI as a tool for inquiry. This reimagined role aligns with the constructivist model of teaching as facilitation and mentorship, and it positions generative AI not as a replacement for human instruction but as a catalyst for deeper, more autonomous learning.

Although the case scenarios presented are grounded in theory and practical experience, they remain proposed frameworks rather than empirically tested interventions. Future studies should evaluate their effectiveness in real classroom settings, examining impacts on student engagement, conceptual understanding, and statistical reasoning. Additionally, the variability in AI model performance and student prompting skills may influence outcomes, warranting further investigation.

5. Conclusions

This paper has proposed a constructivist framework for integrating generative AI into statistics education, grounded in four rich case scenarios that illustrate how AI can support exploratory learning. By shifting the focus from procedural instruction to inquiry-driven engagement, these scenarios demonstrate how generative AI tools such as Julius AI and ChatGPT can act as responsive learning partners, scaffolding student autonomy, curiosity, and critical thinking.

The contributions of this paper are threefold. First, it offers a theoretically grounded rationale for using genAI in statistics education, rooted in constructivist principles. Second, it presents practical, classroom-ready case scenarios that educators can adapt to foster active, contextual, and reflective learning. Third, it reimagines the role of the educator, not as a dispenser of knowledge, but as a designer of AI-enhanced learning experiences and a mentor for critical inquiry.

These insights are particularly timely as higher education grapples with the pedagogical implications of AI. Rather than viewing genAI as a threat to traditional teaching, this paper positions it as a catalyst for pedagogical reform, one that empowers students to become active constructors of statistical understanding.

Future research should explore the empirical impact of these AI-enhanced strategies on student learning outcomes, engagement, and conceptual mastery. Longitudinal studies could investigate how students’ statistical reasoning evolves through repeated interactions with AI, and comparative studies could assess the effectiveness of different prompting strategies and AI models. Additionally, ethical considerations, such as data privacy, algorithmic bias, and the risk of over-reliance, warrant further investigation to ensure that genAI integration remains pedagogically sound and socially responsible.

As genAI becomes more embedded in education, ethical considerations must be addressed. Educators should guide students in critically evaluating AI outputs, recognizing potential biases, and ensuring data privacy. Over-reliance on AI tools may hinder independent thinking if not carefully scaffolded. Responsible integration requires transparency, verification, and a commitment to pedagogical integrity.

Financial Disclosure

None reported.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflict of interests.

Abbreviations

ANA, anti-nuclear antibodies; APC, antigen-presenting cells; IRF, interferon regulatory factor.

References

- Ashburn, Elizabeth Alexander and Robert E Floden. 2006. Meaningful learning using technology: What educators need to know and do. Teachers College Press.

- Baidoo-Anu, David and Leticia Owusu Ansah. 2023. Education in the era of generative artificial intelligence (ai): Understanding the potential benefits of chatgpt in promoting teaching and learning. Journal of AI 7(1), 52–62. [CrossRef]

- Barr, Robert B and John Tagg. 1995. From teaching to learning—a new paradigm for undergraduate education. Change: The magazine of higher learning 27(6), 12–26. [CrossRef]

- Barrows, Howard S. 1996. Problem-based learning in medicine and beyond: A brief overview. New directions for teaching and learning 1996(68), 3–12. [CrossRef]

- Bransford, John D, Ann L Brown, Rodney R Cocking, et al. 2000. How people learn, Volume 11. Washington, DC: National academy press.

- Cobb, Paul. 1999. Individual and collective mathematical development: The case of statistical data analysis. Mathematical thinking and learning 1(1), 5–43. [CrossRef]

- Driver, Rosalind, Hilary Asoko, John Leach, Philip Scott, and Eduardo Mortimer. 1994. Constructing scientific knowledge in the classroom. Educational researcher 23(7), 5–12. [CrossRef]

- Duzenlı, Hulya. 2018. Teaching in a digital age: Guidelines for designing teaching and learning for a digital age.

- Dweck, Carol S. 2006. Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random house.

- Fakour, Hoda and Moslem Imani. 2025. Socratic wisdom in the age of ai: a comparative study of chatgpt and human tutors in enhancing critical thinking skills. In Frontiers in Education, Volume 10, pp. 1528603. Frontiers Media SA.

- Garfield, Joan and Dani Ben-Zvi. 2007. How students learn statistics revisited: A current review of research on teaching and learning statistics. International statistical review 75(3), 372–396. [CrossRef]

- Glasersfeld, Ernst von. 1995. Radical constructivism: A way of knowing and learning. (No Title).

- Hannah, Lorin and Ellina Chernobilsky. 2024. Generative ai and statistical analysis: An exploratory study.

- Hmelo-Silver, Cindy E, Ravit Golan Duncan, and Clark A Chinn. 2007. Scaffolding and achievement in problem-based and inquiry learning: a response to kirschner, sweller, and. Educational psychologist 42(2), 99–107. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Jae Ki and Sun Young Ban. 2022. Teaching statistics with an inquiry-based learning approach.

- Libman, Zipora. 2010. Integrating real-life data analysis in teaching descriptive statistics: A constructivist approach. Journal of Statistics Education 18(1). [CrossRef]

- Loveland, Jennifer L. 2014. Traditional lecture versus an activity approach for teaching statistics: A comparison of outcomes. Utah State University.

- Piaget, Jean. 2013. The construction of reality in the child. Routledge.

- Prandner, Dimitri, Daniela Wetzelhütter, and Sönke Hese. 2025. Chatgpt as a data analyst: an exploratory study on ai-supported quantitative data analysis in empirical research. In Frontiers in Education, Volume 9, pp. 1417900. Frontiers Media SA.

- Schwarz, Joachim. 2025. The use of generative ai in statistical data analysis and its impact on teaching statistics at universities of applied sciences. Teaching Statistics 47(2), 118–128. [CrossRef]

- Snee, Ronald D. 1993. What’s missing in statistical education? The american statistician 47(2), 149–154. [CrossRef]

- Sperber, Dan and Deirdre Wilson. 1986. Relevance: Communication and cognition, Volume 142. Harvard University Press Cambridge, MA.

- Tishkovskaya, Svetlana and Gillian A Lancaster. 2012. Statistical education in the 21st century: A review of challenges, teaching innovations and strategies for reform. Journal of Statistics Education 20(2). [CrossRef]

- Vukojičić, Milić and Jovana Krstić. 2023. Chatgpt in programming education: Chatgpt as a programming assistant. InspirED Teachers’ Voice 2023(1), 7–13.

- Vygotsky, Lev S. 1978. Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes, Volume 86. Harvard university press.

- Wahba, Fatima, Aseel Omar Ajlouni, and Mofeed Ahmed Abumosa. 2024. The impact of chatgpt-based learning statistics on undergraduates’ statistical reasoning and attitudes toward statistics. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education 20(7), em2468. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Summary of Case Scenarios and Constructivist Alignment

Table 1.

Summary of Case Scenarios and Constructivist Alignment

| Case Scenario |

Student Activity |

Learning Objective |

Constructivist Principles |

| AI-Assisted Data Exploration |

Exploratory data analysis using AI-generated prompts and feedback |

Develop EDA skills and critical inquiry |

Active learning, contextual learning, metacognition |

| Socratic Dialogue for Test Selection |

Engaging in guided questioning to choose appropriate statistical tests |

Strengthen statistical reasoning and decision-making |

Social learning, metacognition, active learning |

| Clarifying Complex Concepts |

Requesting explanations, analogies, and visualizations for abstract ideas |

Understand concepts like likelihood and probability |

Personalized learning, contextual learning, reflection |

| Statistical Coding and Debugging |

Generating, modifying, and interpreting code with AI support |

Build fluency in R/Python coding and statistical interpretation |

Iterative learning, active learning, conceptual mentoring |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).