Submitted:

11 September 2025

Posted:

12 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Interfacial Bonding and Residual Stress of Single Splats

1.3. Structure of This Review

2. Characterization of the Bonding Strength in Single Splats

2.1. Tensile Test

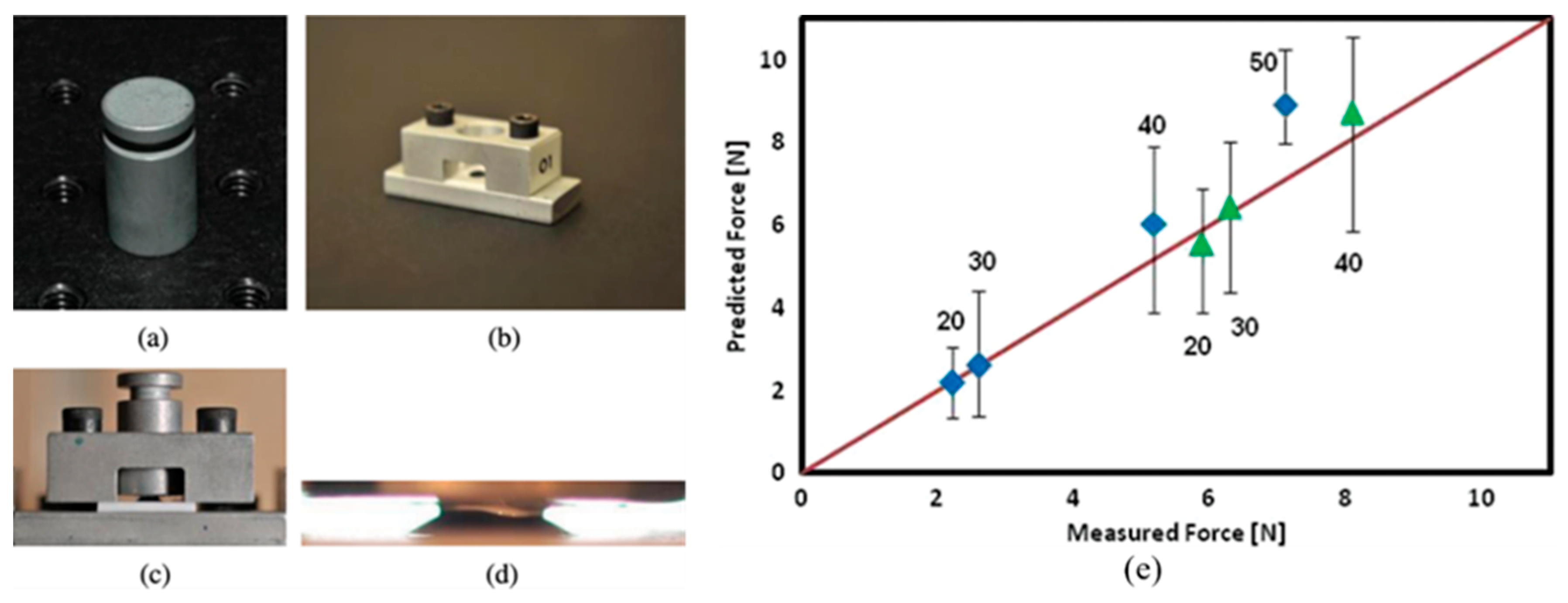

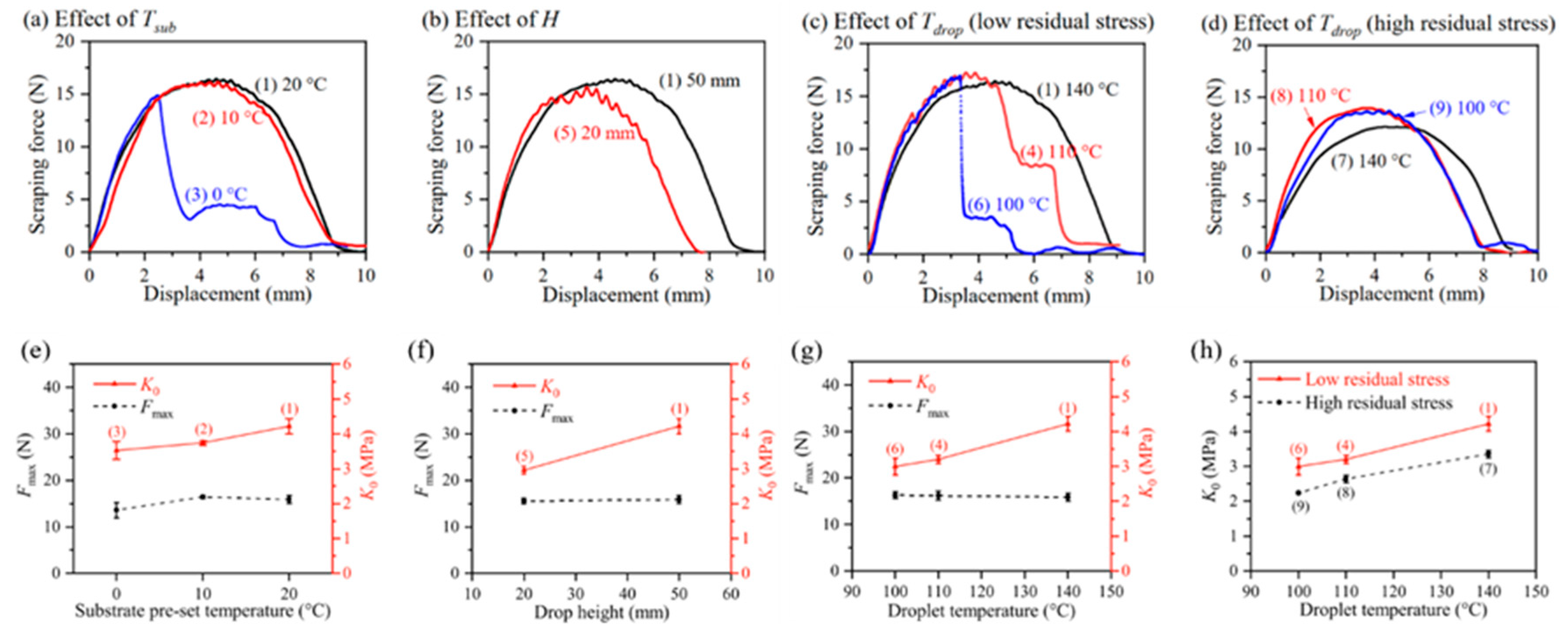

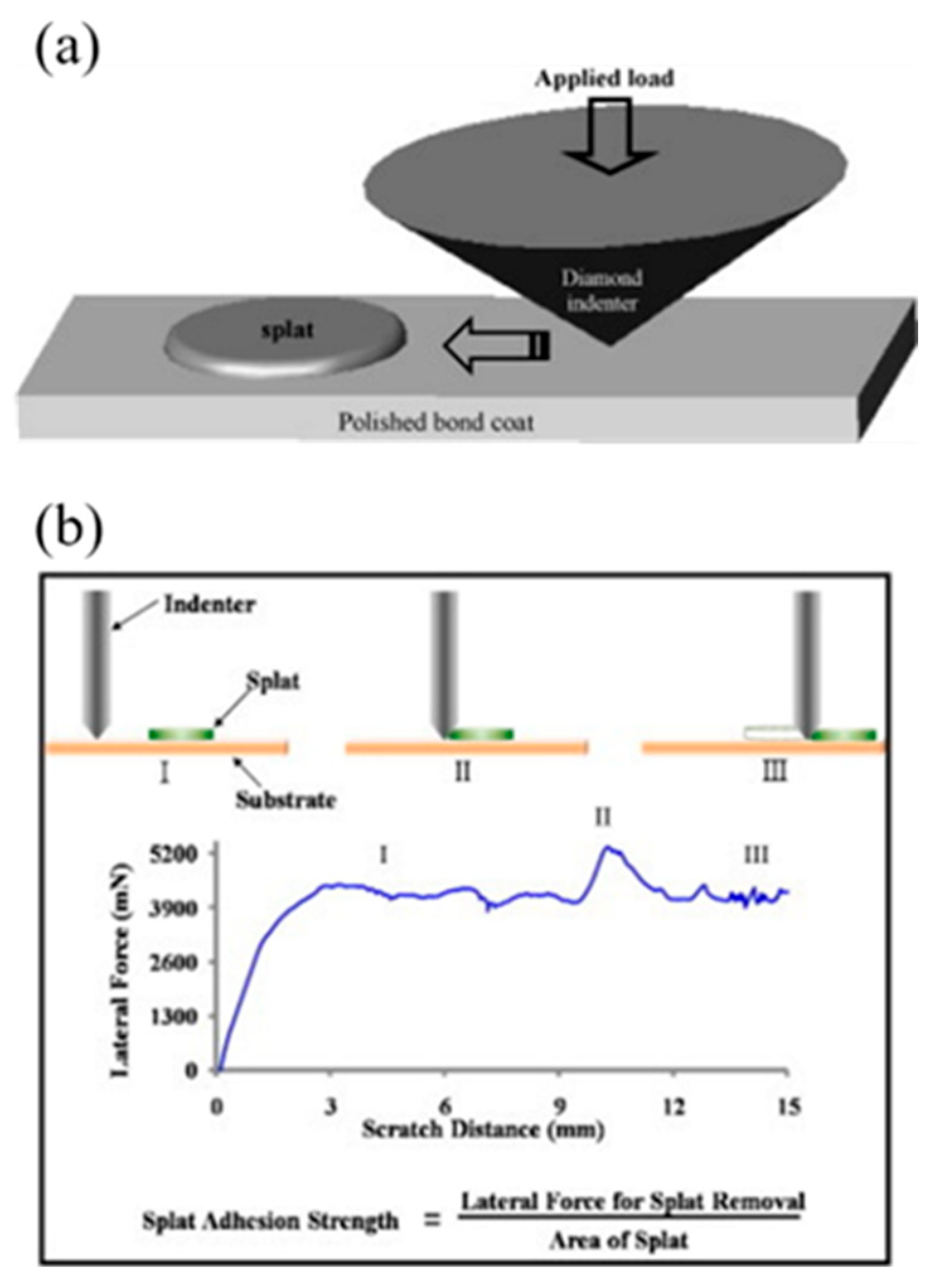

2.2. Scraping Test

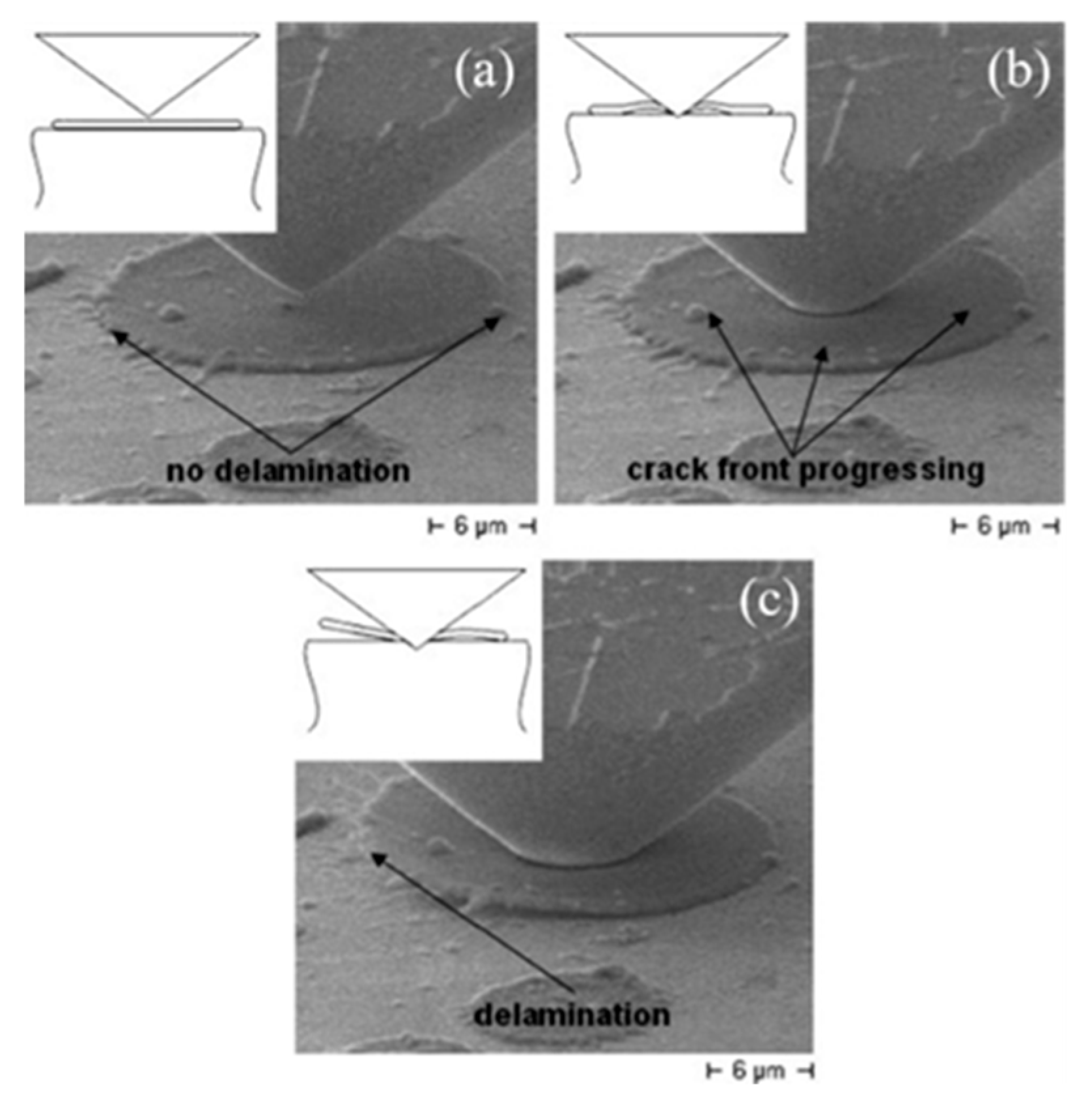

2.3. Indentation Test

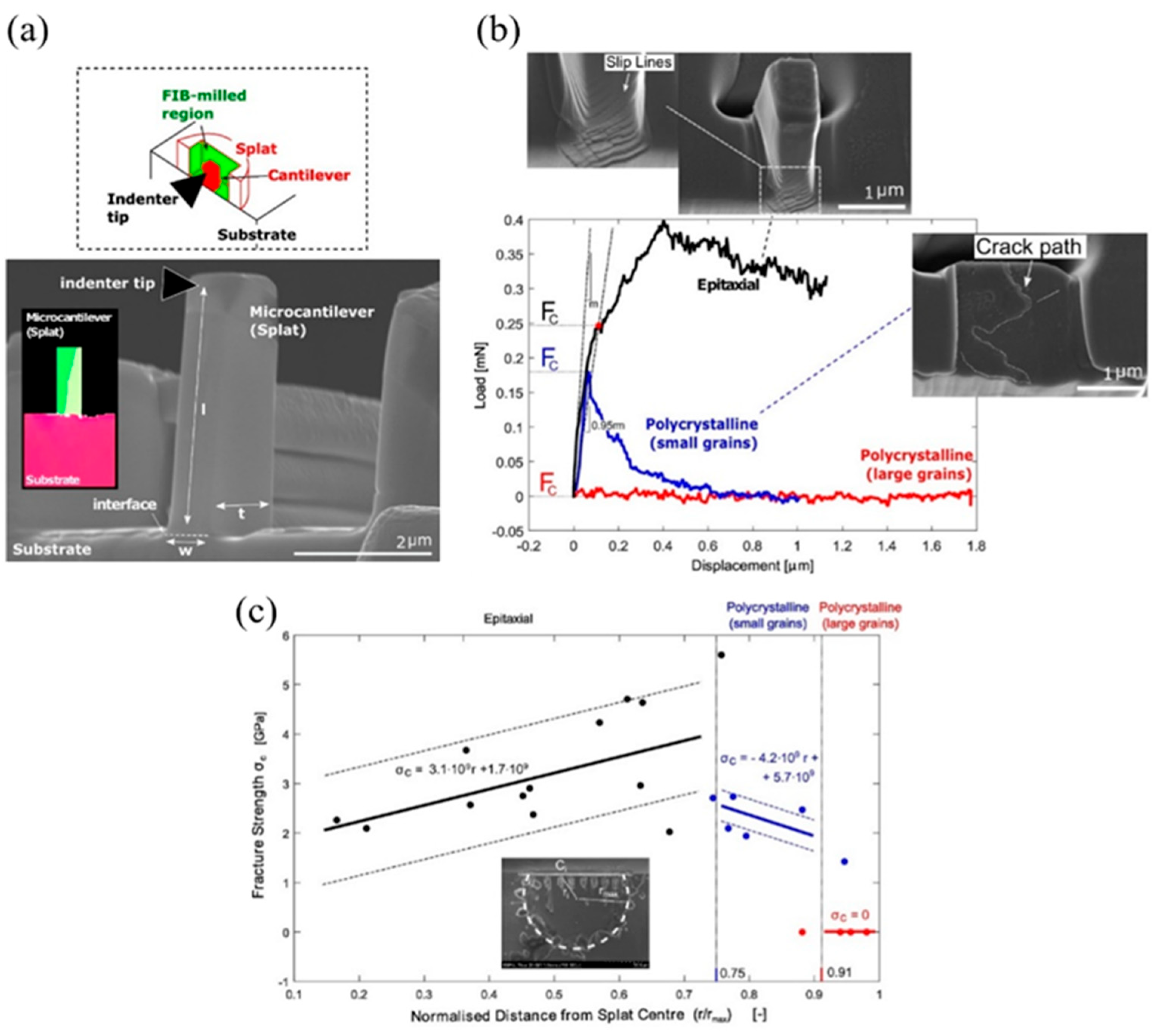

2.4. Focused Ion Beam-Milled Microcantilever Beam Bending Test

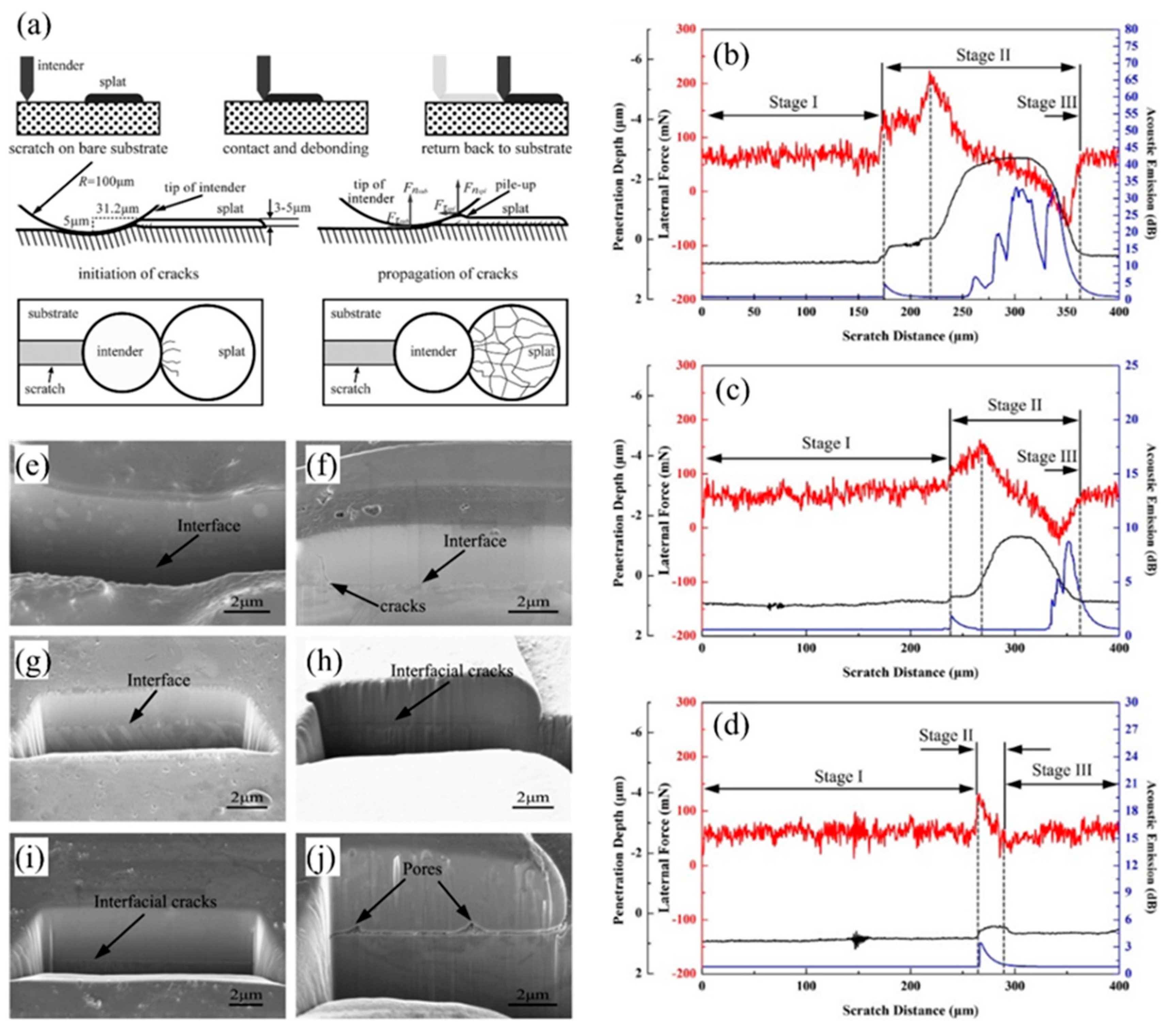

2.5. Scratch Test

2.6. Short Summary

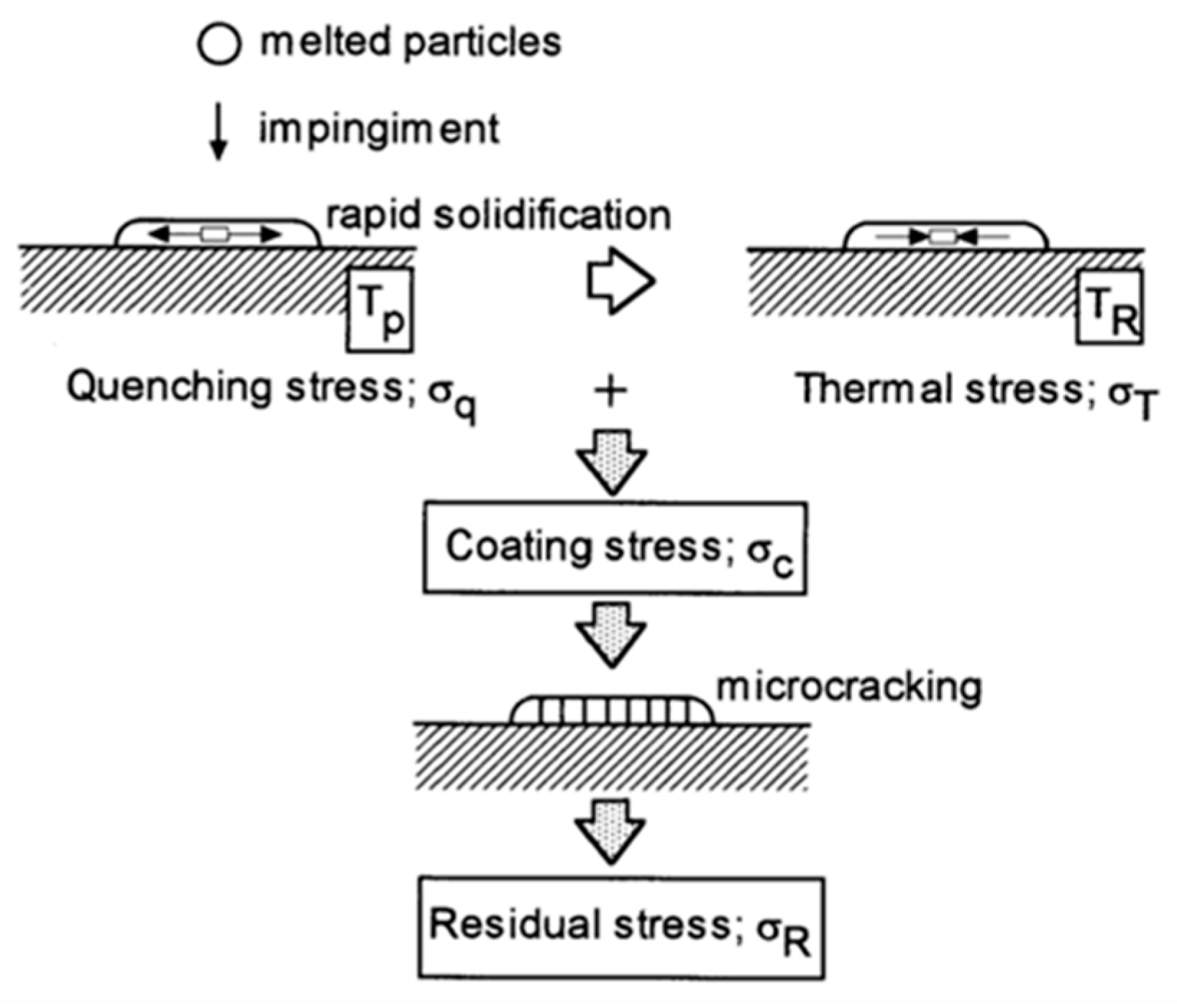

3. Characterization of the Residual Stress in Single Splats

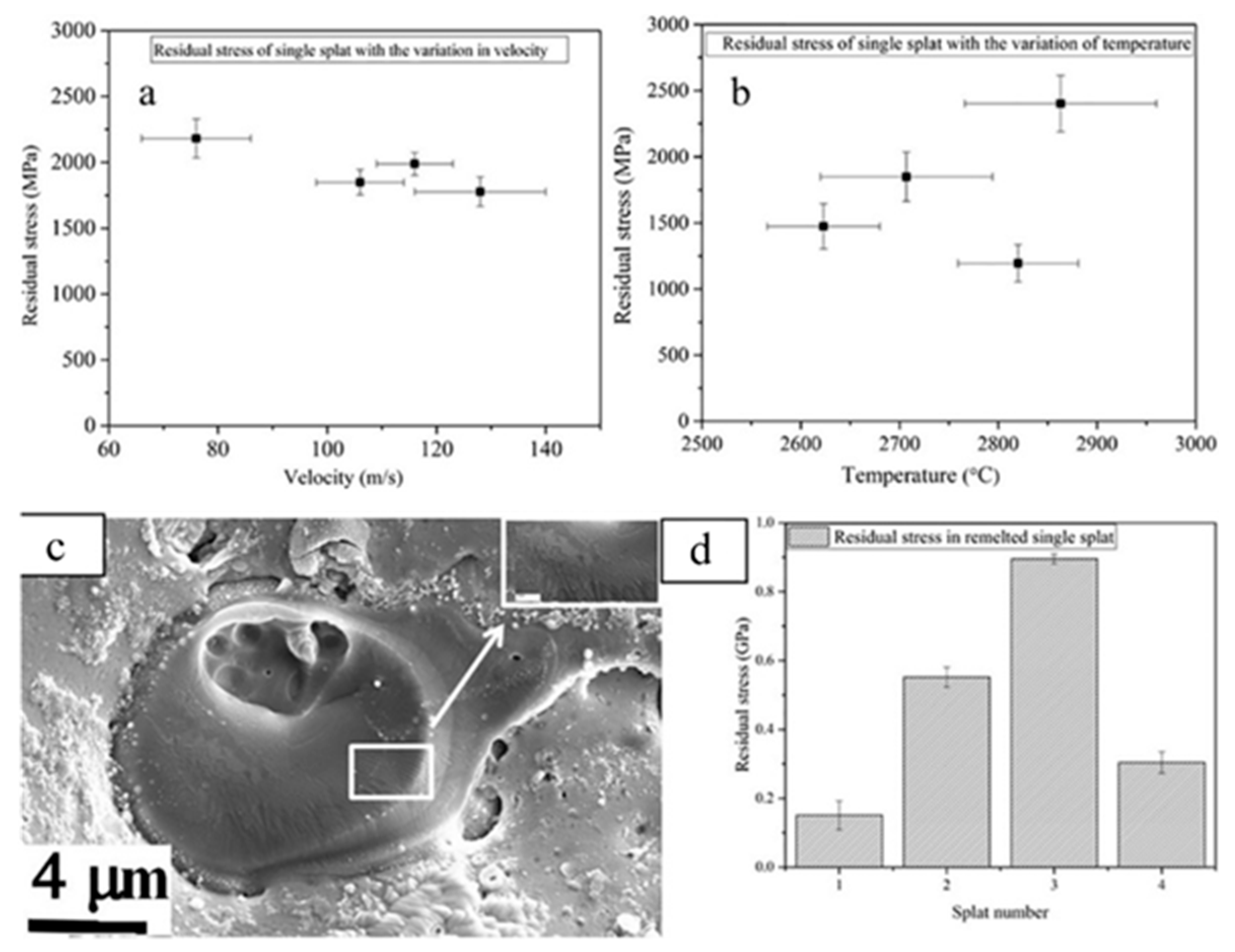

3.1. X-Ray Diffraction

3.2. Raman Spectroscopy

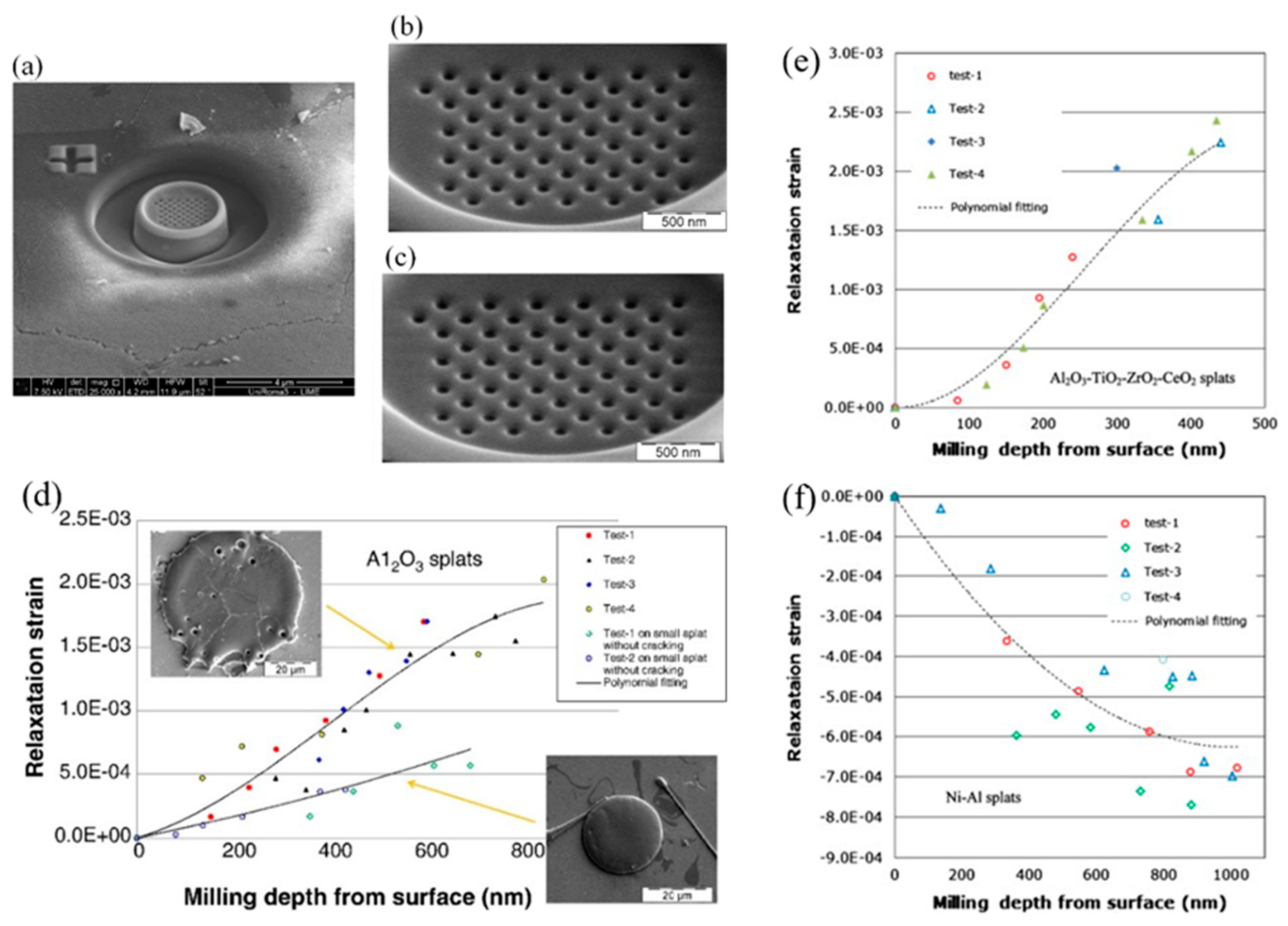

3.3. Focused Ion Beam–Digital Image Correlation

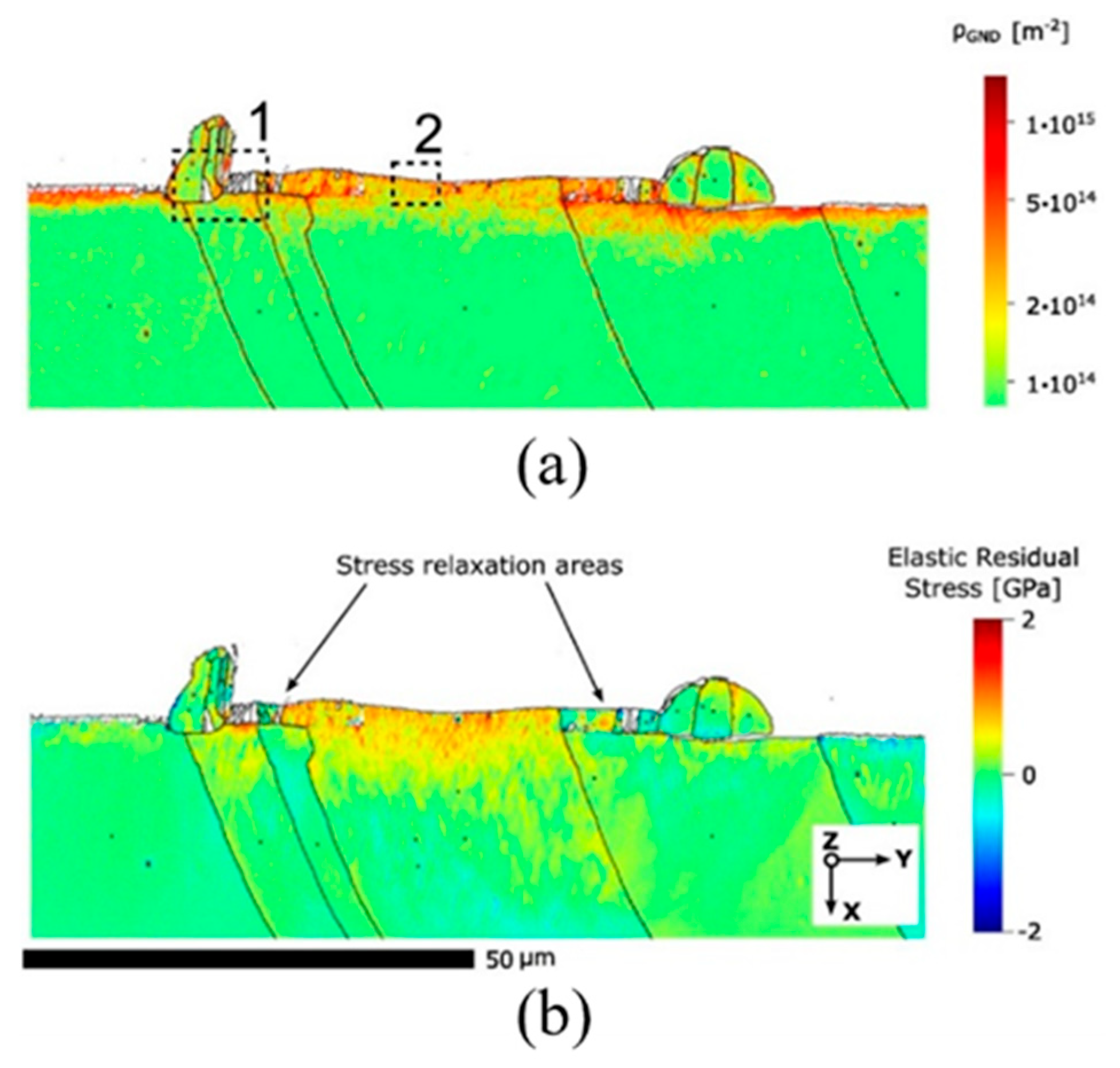

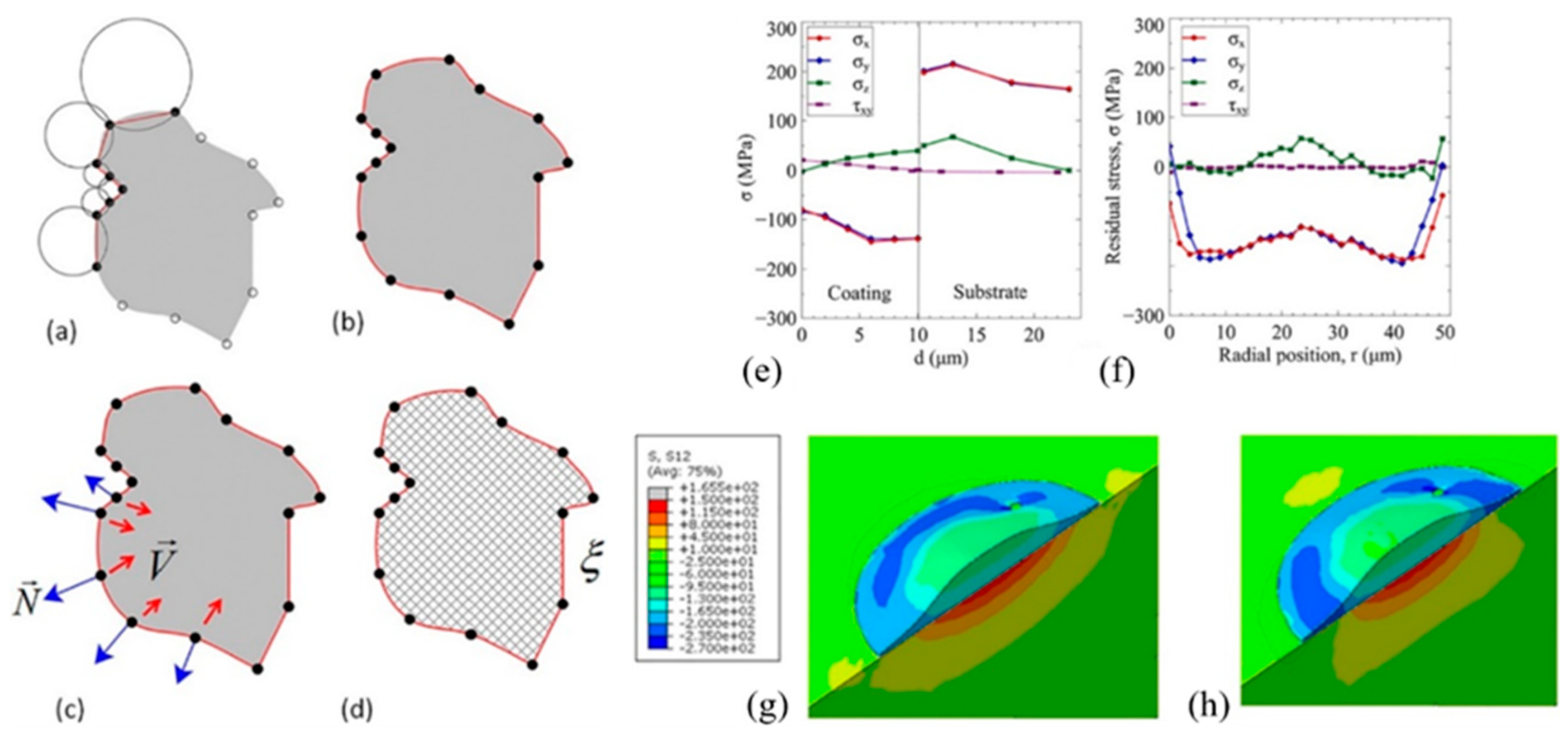

3.4. High-Resolution Electron Backscatter Diffraction via Cross-Correlation-Based Pattern Shift Analysis

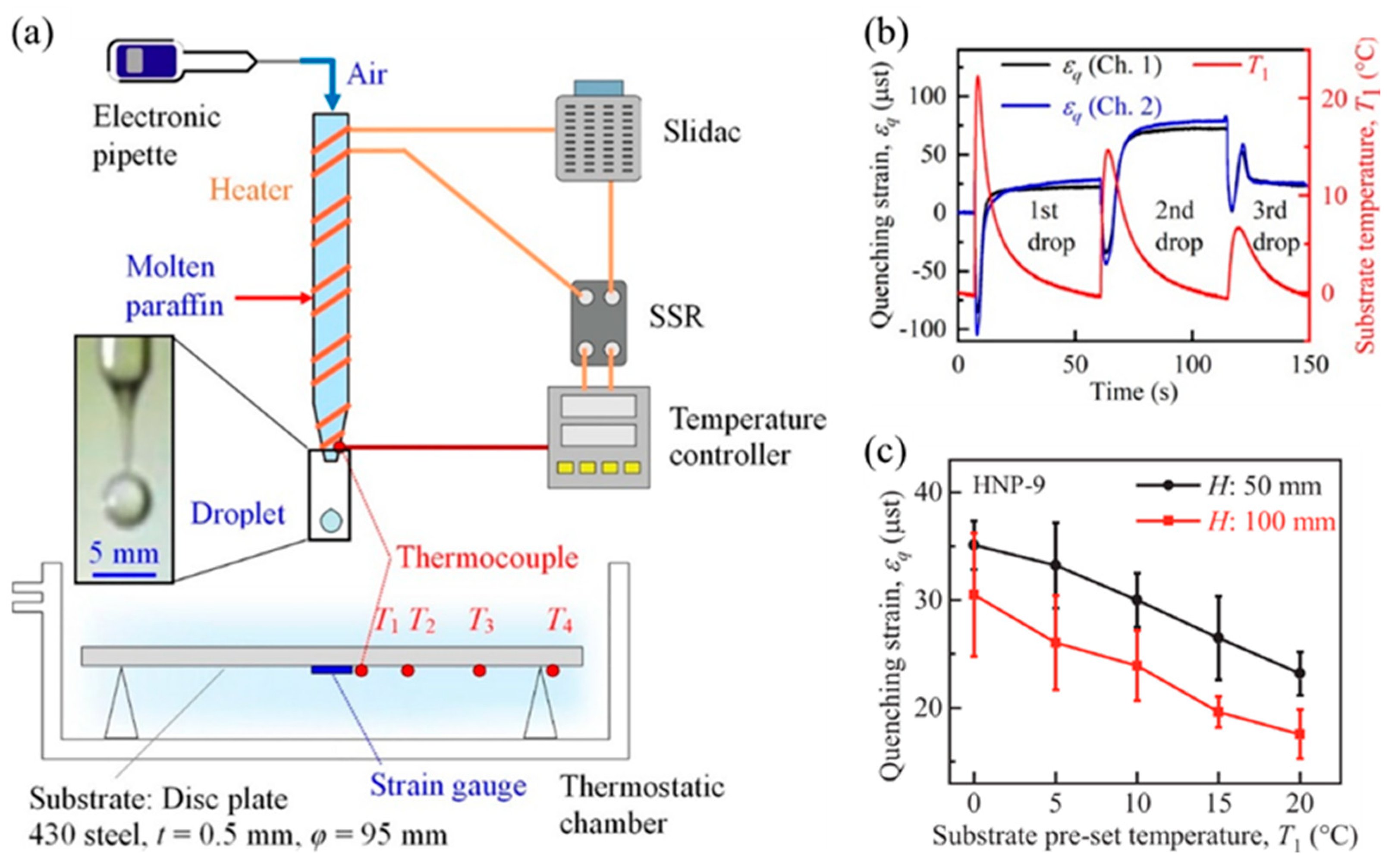

3.5. Strain Evolution Measured Using Strain Gauges

3.6. Short Summary

4. Analytical Models and Numerical Simulations of the Residual Stress in Single Splats

4.1. Analytical Models

4.2. Numerical Simulations

4.3. Short Summary

5. The Interplay of Bonding Strength and Residual Stress in Single Splats: Mechanisms and Control Strategies

5.1. Correlation Between Residual Stress and Interfacial Bonding Strength

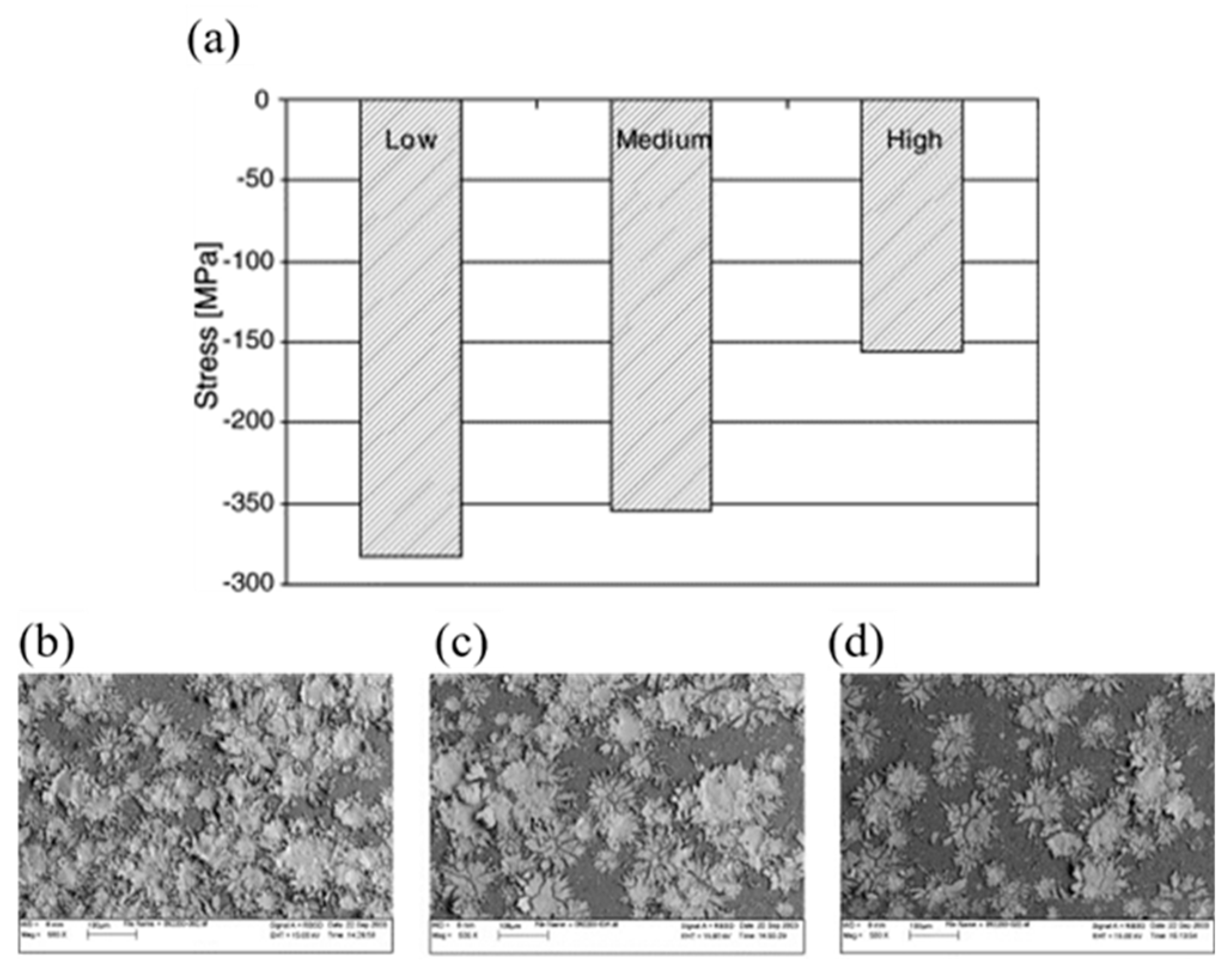

5.2. Factors Influencing Residual Stress of Single Splats

5.3. Strategies for Improving Interfacial Bonding

5.3.1. Optimizing the Substrate Preheating Temperature

5.3.2. Improving Particle Impact Velocity

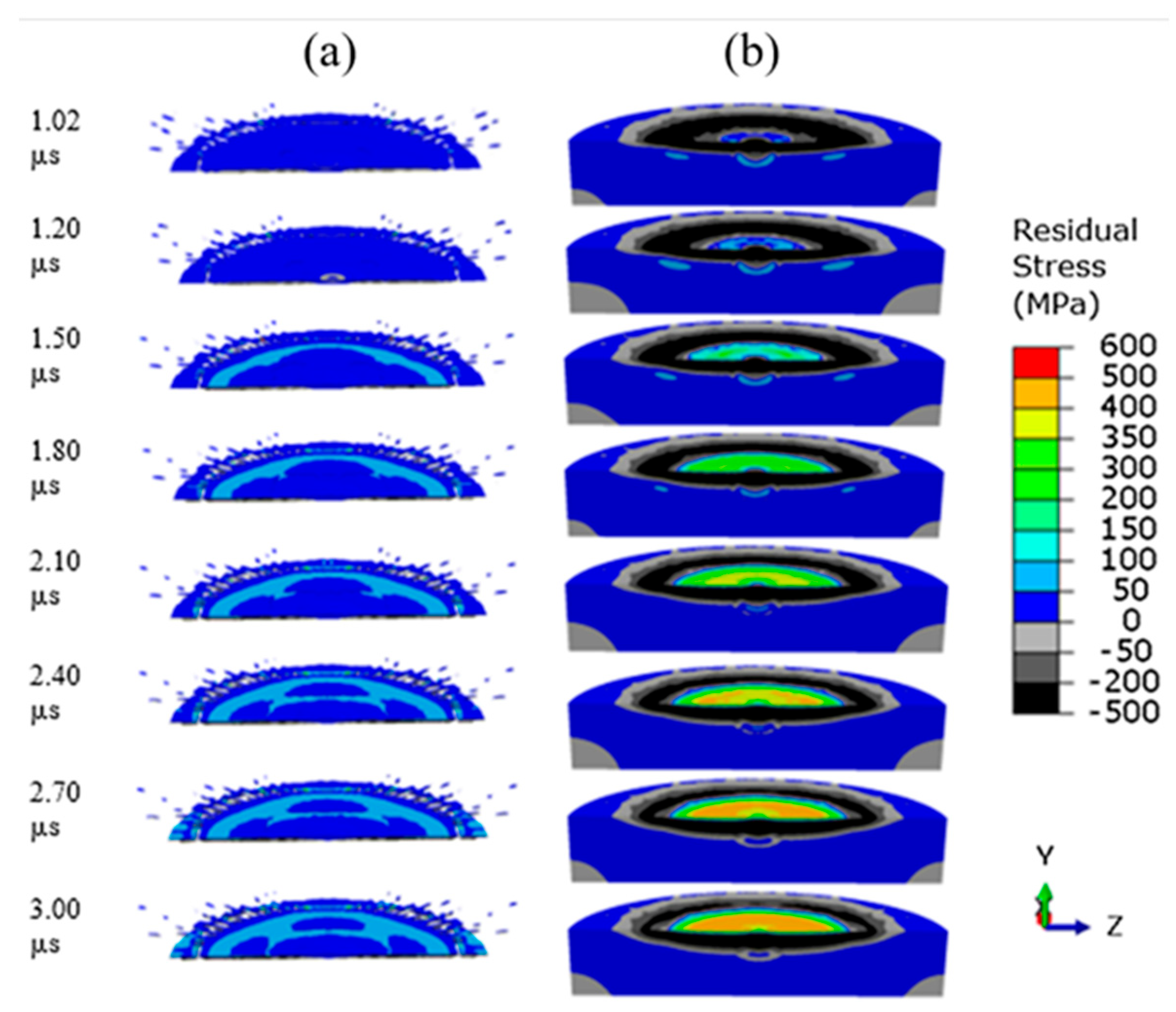

5.4. Role of Deposition Dynamics in Determining Mechanical Properties

5.5. Short Summary

6. Summary and Perspective

6.1. Summary

- Characterization of bonding strength: Various techniques have been employed to measure the bonding strength at the splat/substrate interface. The scratch test remains the most widely applied owing to its relative simplicity and sensitivity to interfacial adhesion. However, more refined approaches, such as tensile loading, indentation, scraping, and FIB-milled microcantilever bending, have been used to capture interfacial fracture behavior under different loading modes. These studies collectively reveal that bonding strength is significantly influenced by particle impact velocity, substrate preheating, and interfacial solidification dynamics. Enhanced bonding typically results from higher kinetic energy, increased interfacial temperature, and improved chemical or metallurgical bonding during rapid solidification.

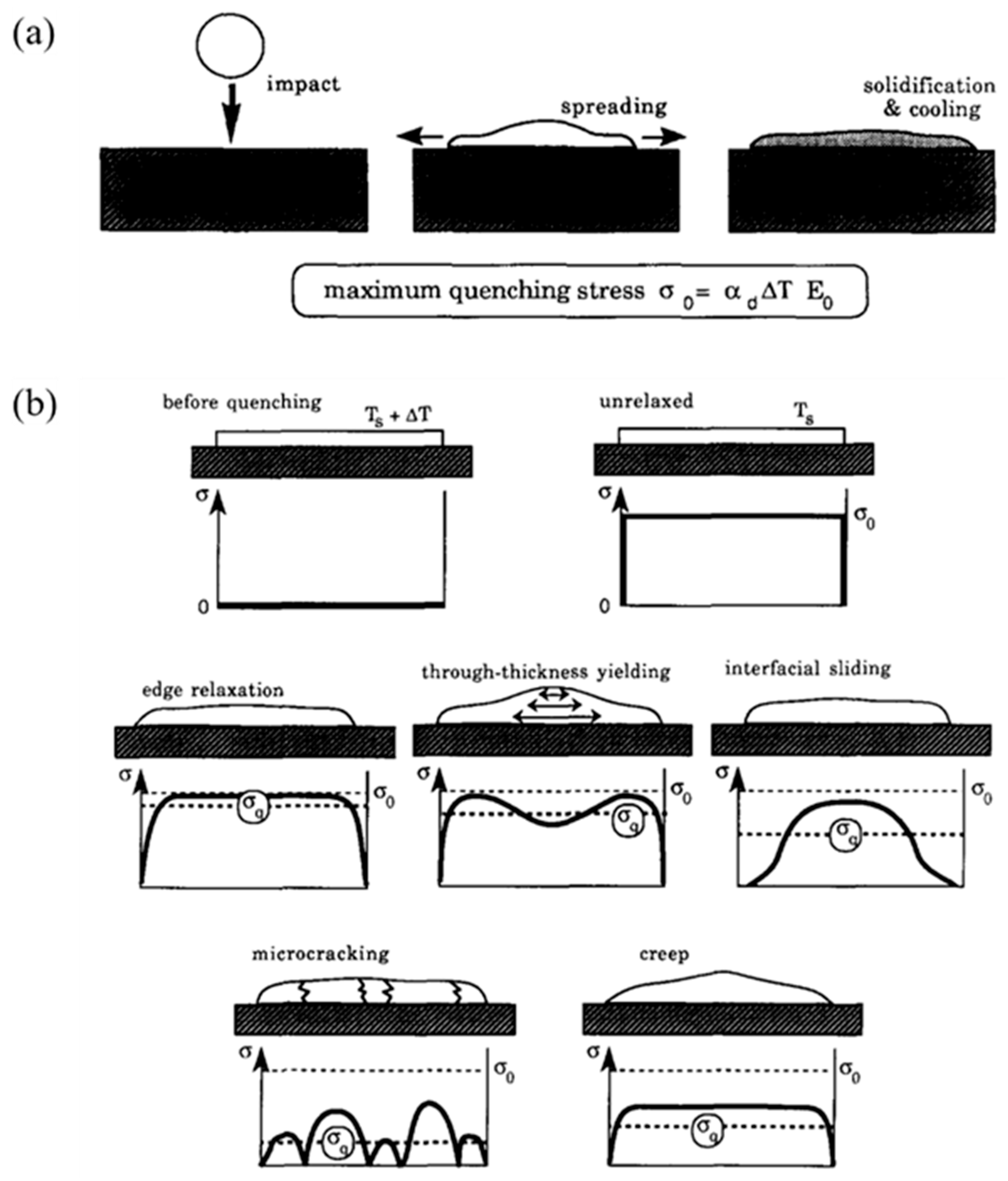

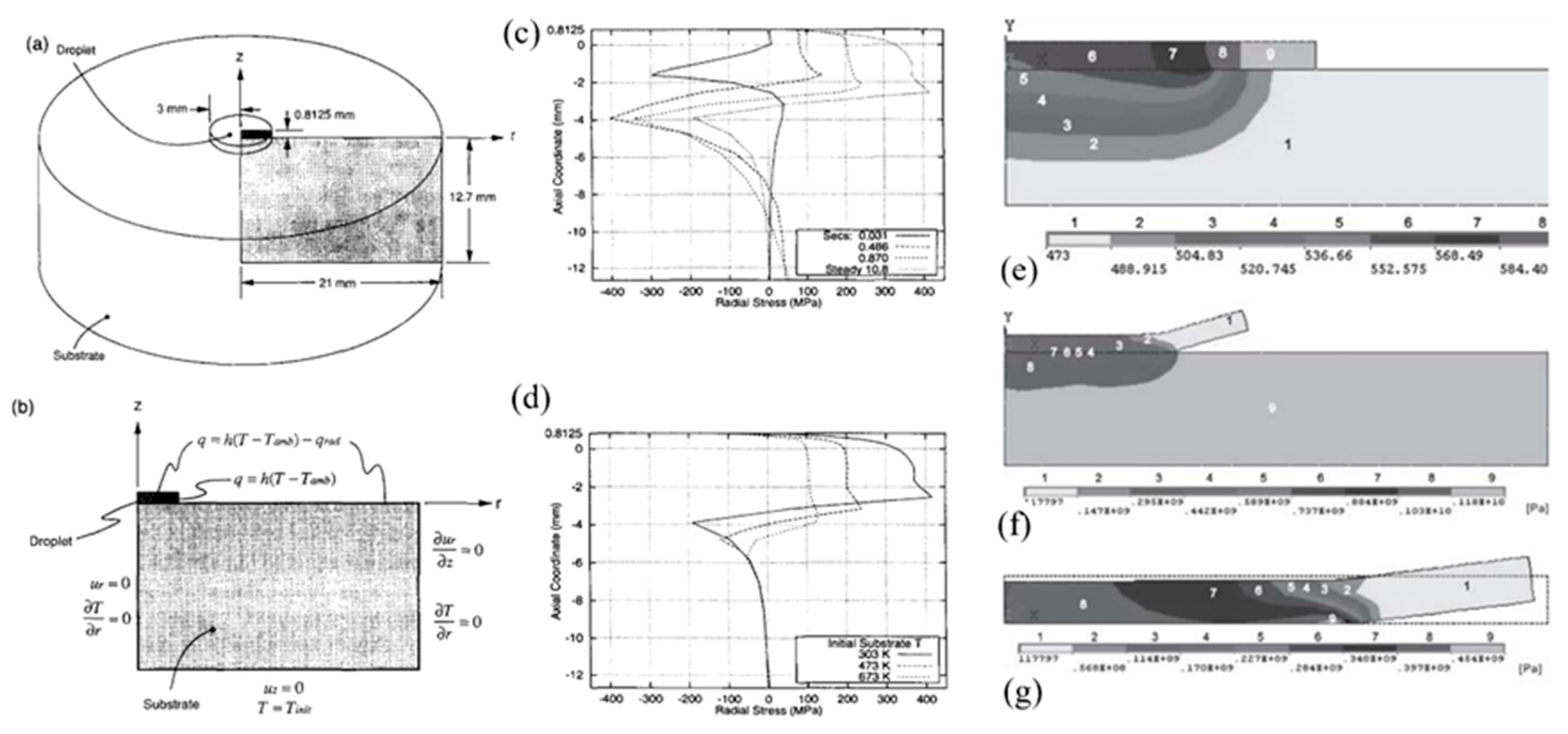

- Measurement and modeling of residual stress: Residual stress in single splats arises from thermal contraction during solidification and quenching, as well as mismatched thermal expansion between the splat and substrate during subsequent cooling. Experimental methods, such as XRD, micro-indentation, and curvature measurements, have enabled residual stress quantification, but in-situ techniques remain limited. FE simulations combined with thermal and mechanical modeling provide insight into transient stress evolution and distribution. These models have evolved to incorporate elastic, plastic, and time-dependent deformation mechanisms and increasingly use fluid dynamics outputs as initial conditions for mechanical simulations.

- Coupling of bonding strength and residual stress: Bonding strength and residual stress are interrelated through their dependence on splat formation dynamics. Residual tensile stress can weaken the interface by partially offsetting externally applied stress during testing, thereby reducing apparent adhesion strength. Conversely, stress relaxation mechanisms, such as cracking, interfacial debonding, plastic yielding, and edge curling, may alter the stress state. As a result, the mechanical stability of a splat is not only a function of initial bonding but also of the stress evolution and dissipation during cooling.

- Influence of deposition conditions: The mechanical outcomes of splats are governed by the interplay between particle velocity, temperature, substrate conditions, and material properties. Substrate preheating is particularly influential because it alters the cooling rate, quenching stress magnitude, and solidification front behavior. Furthermore, material-dependent properties, such as the thermal conductivity and CTE, control stress accumulation and relaxation behaviors across different splat–substrate systems.

6.2. Perspective

- The mechanisms governing splat–substrate bonding and stress development are strongly influenced by transient phenomena during impact and solidification. However, real-time observation of interfacial phase changes, temperature gradients, and bonding formation remains largely inaccessible. The development of in-situ detection techniques, such as high-speed imaging, high-speed thermal mapping, or electron microscopy with time-resolved capabilities, may provide unprecedented insight into interfacial processes at the sub-microsecond scale.

- Most current techniques for measuring bonding strength are either qualitative or subject to high variability because of the sample preparation and loading conditions. There is a critical need to establish standardized, reproducible methods for quantifying interfacial tensile and shear strength. This would not only improve comparability across studies but also enable more precise evaluation of the interfacial properties.

- Capturing the spatial and temporal evolution of residual stress during splat cooling remains a key issue. In-situ methods, such as DIC and laser-based strain mapping, combined with advanced modeling that accounts for inelastic deformation and stress relaxation, are essential for the accurate prediction of residual stress states. Furthermore, modeling frameworks should include imperfect bonding, interfacial sliding, and phase-dependent mechanical properties.

- A major gap in current computational approaches is the separation between fluid dynamics simulations (governing droplet spreading and solidification) and mechanical modeling (describing stress evolution). A unified multi-physics model that integrates hydrodynamics, heat transfer, phase transformation, and stress generation within a single simulation framework is highly desirable. Such a model is expected to enable the predictive design of deposition processes based on targeted mechanical outcomes at the splat scale.

Acknowledgments

References

- Chandra, S.; Fauchais, P. Formation of solid splats during thermal spray deposition. Journal of Thermal Spray Technology 2009, 18, 148–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, L.-M. Application of hardmetals as thermal spray coatings. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials 2015, 49, 350–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-J.; et al. The bonding formation during thermal spraying of ceramic coatings: a review. Journal of Thermal Spray Technology 2022, 31, 780–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovicova, E.; Schadler, L.S. Thermal spraying of polymers. International Materials Reviews 2002, 47, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathish, M.; Radhika, N.; Saleh, B. Duplex and composite coatings: a thematic review on thermal spray techniques and applications. Metals and Materials International 2023, 29, 1229–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorfman, M.R.; et al. Perspective: challenges in the aerospace marketplace and growth opportunities for thermal spray. Journal of Thermal Spray Technology 2022, 31, 672–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prashar, G.; Vasudev, H. Thermal sprayed composite coatings for biomedical implants: a brief review. Journal of Thermal Spray and Engineering 2020, 2, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitamura, J.; Tang, Z.; Mizuno, H.; Sato, K.; Burgess, A. Structural, mechanical and erosion properties of yttrium oxide coatings by axial suspension plasma spraying for electronics applications. Journal of Thermal Spray Technology 2011, 20, 170–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampath, S. Thermal spray applications in electronics and sensors: past, present, and future. Journal of Thermal Spray Technology 2010, 19, 921–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Niessen, K.; Gindrat, M. Plasma spray-PVD: a new thermal spray process to deposit out of the vapor phase. Journal of Thermal Spray Technology 2011, 20, 736–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, Regina MH Pombo, et al. “Comparison of aluminum coatings deposited by flame spray and by electric arc spray.” Surface and Coatings Technology 202.1 (2007): 172-179. [CrossRef]

- Picas, J.A.; Forn, A.; Matthäus, G. HVOF coatings as an alternative to hard chrome for pistons and valves. Wear 2006, 261, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lett, S.; et al. Residual stresses development during cold spraying of Ti-6Al-4V combined with in situ shot peening. Journal of Thermal Spray Technology 2023, 32, 1018–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moridi, A.; et al. Fatigue behavior of cold spray coatings: The effect of conventional and severe shot peening as pre-/post-treatment. Surface and Coatings Technology 2015, 283, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rein, M. Phenomena of liquid drop impact on solid and liquid surfaces. Fluid Dynamics Research 1993, 12, 61–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarin, A.L. Drop impact dynamics: splashing, spreading, receding, bouncing…. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics 2006, 38, 159–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josserand, C.; Thoroddsen, S.T. Drop impact on a solid surface. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics 2016, 48, 365–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dykhuizen, R.C. Review of impact and solidification of molten thermal spray droplets. Journal of Thermal Spray Technology 1994, 3, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.; Samanta, R.; Chattopadhyay, H. Droplet solidification: Physics and modelling. Applied Thermal Engineering 2023, 228, 120515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Sun, T.-P.; Gordillo, L. Drop impact dynamics: Impact force and stress distributions. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics 2022, 54, 57–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauchais, P.; et al. Knowledge concerning splat formation: an invited review. Journal of Thermal Spray Technology 2004, 13, 337–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; et al. Particle characterization and splat formation of plasma sprayed zirconia. Journal of Thermal Spray Technology 2006, 15, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobolev, V.V.; Guilemany, J.M. Flattening of droplets and formation of splats in thermal spraying: a review of recent work—part 1. Journal of Thermal Spray Technology 1999, 8, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobolev, V.V.; Guilemany, J.M. Flattening of droplets and formation of splats in thermal spraying: A review of recent work—Part 2. Journal of Thermal Spray Technology 1999, 8, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-J.; Yang, G.-J.; Li, C.-X. Development of particle interface bonding in thermal spray coatings: a review. Journal of Thermal Spray Technology 2013, 22, 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. Spray cooling heat transfer: The state of the art. International Journal of Heat and Fluid Flow 2007, 28, 753–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, S.; et al. A comprehensive review of modeling water solidification for droplet freezing applications. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2023, 188, 113768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolleddula, D.A.; Berchielli, A.; Aliseda, A. Impact of a heterogeneous liquid droplet on a dry surface: Application to the pharmaceutical industry. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science 2010, 159, 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Mudawar, I. Review of drop impact on heated walls. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 2017, 106, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khojasteh, D.; et al. Droplet impact on superhydrophobic surfaces: A review of recent developments. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 2016, 42, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, P.; Driscoll, M.M. “Drop impact dynamics of complex fluids: A review.” Soft Matter (2024).

- DelRio, F.W.; et al. The role of van der Waals forces in adhesion of micromachined surfaces. Nature Materials 2005, 4, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlowski, Lech. The science and engineering of thermal spray coatings. John Wiley & Sons, 2008.

- Kuroda, S.C.T.W.; Clyne, T.W. The quenching stress in thermally sprayed coatings. Thin Solid Films 1991, 200, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thouless, M.D.; Jensen, H.M. The effect of residual stresses on adhesion measurements. Journal of Adhesion Science and Technology 1994, 8, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tönshoff, H.K.; Seegers, H. Influence of residual stress gradients on the adhesion strength of sputtered hard coatings. Thin Solid Films 2000, 377, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Yung-Chin, and Edward Chang. “Influence of residual stress on bonding strength and fracture of plasma-sprayed hydroxyapatite coatings on Ti–6Al–4V substrate.” Biomaterials 22.13 (2001): 1827-1836. [CrossRef]

- Sampath, S.; Jiang, X. Splat formation and microstructure development during plasma spraying: deposition temperature effects. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2001, 304, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almohammadi, H.; Amirfazli, A. Droplet impact: Viscosity and wettability effects on splashing. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2019, 553, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes, Ramon SC, S. C. Amico, and A. S. C. M. d’Oliveira. “The effect of roughness and pre-heating of the substrate on the morphology of aluminium coatings deposited by thermal spraying.” Surface and Coatings Technology 200.9 (2006): 3049-3055. [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.-J.; et al. Critical bonding temperature for the splat bonding formation during plasma spraying of ceramic materials. Surface and Coatings Technology 2013, 235, 841–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani-Gangaraj, M.; et al. In-situ observations of single micro-particle impact bonding. Scripta Materialia 2018, 145, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Peng-fei, et al. “Influence of in-flight particle characteristics and substrate temperature on the formation mechanisms of hypereutectic Al-Si-Cu coatings prepared by supersonic atmospheric plasma spraying.” Journal of Materials Science & Technology 87 (2021): 216-233. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; et al. Formation of refined grains below 10 nm in size and nanoscale interlocking in the particle–particle interfacial regions of cold sprayed pure aluminum. Scripta Materialia 2020, 177, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, C.D.; et al. Impact induced metallurgical and mechanical interlocking in metals. Computational Materials Science 2021, 192, 110363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.; et al. Splat formation mechanism of droplet-filled cold-textured groove during plasma spraying. Applied Thermal Engineering 2020, 173, 115239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harfouche, M.M.; et al. Scratch adhesion testing of thick HVOF thermal sprayed coatings. Journal of Thermal Spray Technology 2024, 33, 1158–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kromer, R.; et al. Laser surface texturing to enhance adhesion bond strength of spray coatings–Cold spraying, wire-arc spraying, and atmospheric plasma spraying. Surface and Coatings Technology 2018, 352, 642–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; et al. Microstructure and indentation mechanical properties of plasma sprayed nano-bimodal and conventional ZrO2–8wt% Y2O3 thermal barrier coatings. Vacuum 2012, 86, 1174–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; et al. Investigation on interfacial fracture toughness of plasma-sprayed TBCs using a three-point bending method. Surface and Coatings Technology 2018, 353, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, K. Evaluation of the shearing strength of a WC-12Co thermal spray coating by the scraping test method. Coatings 2015, 5, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadvar, S.; Chandra, S.; Ashgriz, N. Adhesion of wax droplets to porous polymer surfaces. The Journal of Adhesion 2015, 91, 538–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.-K.; Lee, D.-B.; Cho, N.-S.i. Fiber/epoxy interfacial shear strength measured by the microdroplet test. Composites Science and Technology 2009, 69, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.A.; et al. A novel coating method using zinc oxide nanorods to improve the interfacial shear strength between carbon fiber and a thermoplastic matrix. Composites Science and Technology 2016, 134, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; et al. Flattening and solidification behavior of in-flight droplets in plasma spraying and micro/macro-bonding mechanisms. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2019, 784, 834–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.; et al. Adhesion strength of paraffin droplet impacted and solidified on metal substrate. Results in Physics 2022, 34, 105310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; et al. Wide-velocity range high-energy plasma sprayed yttria-stabilized zirconia thermal barrier coating—Part I: Splashing splat formation and micro-adhesive property. Surface and Coatings Technology 2024, 476, 130280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Ruiter, J.; et al. Dynamics of collapse of air films in drop impact. Physical Review Letters 2012, 108, 074505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balić, E.E.; et al. Fundamentals of adhesion of thermal spray coatings: adhesion of single splats. Acta Materialia 2009, 57, 5921–5926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.R.; Evans, A.G. An experimental study of the mechanisms of crack extension along an oxide/metal interface. Acta Materialia 1996, 44, 863–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanicchia, F.; et al. Residual stress and adhesion of thermal spray coatings: Microscopic view by solidification and crystallisation analysis in the epitaxial CoNiCrAlY single splat. Materials & Design 2018, 153, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matoy, K.; et al. A comparative micro-cantilever study of the mechanical behavior of silicon based passivation films. Thin Solid Films 2009, 518, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabiruddin, K.; Bandyopadhyay, P.P. Scratch induced damage in alumina splats deposited on bond coats. Journal of Materials Processing Technology 2011, 211, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshri, A.K.; Lahiri, D.; Agarwal, A. Carbon nanotubes improve the adhesion strength of a ceramic splat to the steel substrate. Carbon 2011, 49, 4340–4347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambagi, S.C.; Bandyopadhyay, P.P. Plasma sprayed carbon nanotube reinforced splats and coatings. Journal of the European Ceramic Society 2017, 37, 2235–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, K.K.; et al. Mechanical property and adhesion strength of carbon nanofillers reinforced alumina single splats using in-situ picoindentation and nanoscratch test. Ceramics International 2021, 47, 26800–26807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Shu-ying, et al. “Evaluation of adhesion strength between amorphous splat and substrate by micro scratch method.” Surface and Coatings Technology 344 (2018): 43-51. [CrossRef]

- Salimijazi, H.R.; et al. Study of solidification behavior and splat morphology of vacuum plasma sprayed Ti alloy by computational modeling and experimental results. Surface and Coatings Technology 2007, 201, 7924–7931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, M.; Wada, E.; Kishimoto, K. Residual stress analysis of ceramic thermal barrier coating based on thermal spray process. Journal of Solid Mechanics and Materials Engineering 2007, 1, 1251–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, F.; et al. Critical compressive strain and interfacial damage evolution of EB-PVD thermal barrier coating. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2020, 776, 139038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutter, M.; et al. Correlation of splat morphologies with porosity and residual stress in plasma-sprayed YSZ coatings. Surface and Coatings Technology 2017, 318, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matejicek, J.; Sampath, S.; Dubsky, J. X-ray residual stress measurement in metallic and ceramic plasma sprayed coatings. Journal of Thermal Spray Technology 1998, 7, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Jones, A.H. High-precision determination of residual stress of polycrystalline coatings using optimised XRD-sin2ψ technique. Surface and Coatings Technology 2010, 205, 1403–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, C.G. X-ray diffraction and the Bragg equation. Journal of Chemical Education 1997, 74, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Matejicek, J.; Sampath, S. Substrate temperature effects on the splat formation, microstructure development and properties of plasma sprayed coatings: Part II: case study for molybdenum. Materials Science and Engineering: A 1999, 272, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matejicek, J.; Sampath, S. Intrinsic residual stresses in single splats produced by thermal spray processes. Acta Materialia 2001, 49, 1993–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, A.; et al. An integrated study of thermal spray process–structure–property correlations: A case study for plasma sprayed molybdenum coatings. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2005, 403, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.; et al. Splat deposition stress formation mechanism of droplets impacting onto texture. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences 2024, 266, 109002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.; Brodard, P.; Bandyopadhyay, P.P. Raman spectroscopy assisted residual stress measurement of plasma sprayed and laser remelted zirconia splats and coatings. Surface and Coatings Technology 2019, 378, 124920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, P.-C.; Hsu, C.-S. High temperature corrosion resistance and microstructural evaluation of laser-glazed plasma-sprayed zirconia/MCrAlY thermal barrier coatings. Surface and Coatings Technology 2004, 183, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsunsky, A.M.; Sebastiani, M.; Bemporad, E. Focused ion beam ring drilling for residual stress evaluation. Materials Letters 2009, 63, 1961–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsunsky, A.M.; Sebastiani, M.; Bemporad, E. Residual stress evaluation at the micrometer scale: Analysis of thin coatings by FIB milling and digital image correlation. Surface and Coatings Technology 2010, 205, 2393–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastiani, M.; et al. Depth-resolved residual stress analysis of thin coatings by a new FIB–DIC method. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2011, 528, 7901–7908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastiani, M.; et al. High resolution residual stress measurement on amorphous and crystalline plasma-sprayed single-splats. Surface and Coatings Technology 2012, 206, 4872–4880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, A.J.; Meaden, G.; Dingley, D.J. High-resolution elastic strain measurement from electron backscatter diffraction patterns: New levels of sensitivity. Ultramicroscopy 2006, 106, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsenlis, A.; Parks, D.M. Crystallographic aspects of geometrically-necessary and statistically-stored dislocation density. Acta Materialia 1999, 47, 1597–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nye, J.F. Some geometrical relations in dislocated crystals. Acta Metallurgica 1953, 1, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kysar, J.W.; et al. Experimental lower bounds on geometrically necessary dislocation density. International Journal of Plasticity 2010, 26, 1097–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amano, A.; et al. Measurement of quenching strain in paraffin drop test modelling thermal spray process. Trans JSME 2017, 83, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, C.; et al. Quenching stress and fracture of paraffin droplet during solidification and adhesion on metallic substrate. Surface and Coatings Technology 2019, 374, 868–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.; Sakaguchi, M.; Inoue, H. Contribution of creep to strain evolution in a paraffin droplet during and after rapid solidification on a metal substrate. Surface and Coatings Technology 2020, 399, 126145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, T.; et al. Finite element analysis of residual stress in plasma-sprayed ceramic coatings. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part L: Journal of Materials: Design and Applications 2004, 218, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, R.K.; Beuth, J.L.; Amon, C.H. Thermomechanical modeling of molten metal droplet solidification applied to layered manufacturing. Mechanics of Materials 1996, 24, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, M.; Chandra, S.; Mostaghimi, J. Investigation of splat curling up in thermal spray coatings. Journal of Thermal Spray Technology 2006, 15, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardan, A.; Ahmed, R. Modeling the evolution of residual stresses in thermally sprayed YSZ coating on stainless steel substrate. Journal of Thermal Spray Technology 2019, 28, 717–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A.A.; Arif, A.F.M. A hybrid computational approach for modeling thermal spray deposition. Surface and Coatings Technology 2019, 362, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A.A.; et al. Splats formation, interaction and residual stress evolution in thermal spray coating using a hybrid computational model. Journal of Thermal Spray Technology 2019, 28, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamberov, G.; Kamberova, G.; Jain, A. “3D shape from unorganized 3D point clouds.” International Symposium on Visual Computing. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2005.

- Garland, M.; Zhou, Y. Quadric-based simplification in any dimension. ACM Transactions on Graphics (TOG) 2005, 24, 209–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyé, S.; Guennebaud, G.; Schlick, C. “Least squares subdivision surfaces.” Computer Graphics Forum. Vol. 29. No. 7. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2010.

- Kazhdan, M.; Hoppe, H. Screened Poisson surface reconstruction. ACM Transactions on Graphics (ToG) 2013, 32, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clyne, T.W.; Gill, S.C. Residual stresses in thermal spray coatings and their effect on interfacial adhesion: a review of recent work. Journal of Thermal Spray Technology 1996, 5, 401–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nairn, J.A. On the calculation of energy release rates for cracked laminates with residual stresses. International Journal of Fracture 2006, 139, 267–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Dillard, D.A.; Nairn, J.A. Effect of residual stress on the energy release rate of wedge and DCB test specimens. International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives 2006, 26, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimamoto, K.; Sekiguchi, Y.; Sato, C. The critical energy release rate of welded joints between fiber-reinforced thermoplastics and metals when thermal residual stress is considered. The Journal of Adhesion 2016, 92, 306–318. [Google Scholar]

- Godoy, C.; Souza, E.A.; Lima, M.M.; Batista, J.C.A. Correlation between residual stresses and adhesion of plasma sprayed coatings: effects of a post-annealing treatment. Thin Solid Films 2002, 420, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-C. Influence of residual stress on bonding strength of the plasma-sprayed hydroxyapatite coating after the vacuum heat treatment. Surface and Coatings Technology 2007, 201, 7187–7193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, P.; et al. Effects of residual stresses on interfacial adhesion measurement. Mechanics of Materials 2009, 41, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-C.; Chang, S.-Y.; Chang, C.-H. Effect of residual stresses on mechanical properties and interface adhesion strength of SiN thin films. Thin Solid Films 2009, 517, 4857–4861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okajima, Y.; Sakaguchi, M.; Inoue, H. A finite element assessment of influential factors in evaluating interfacial fracture toughness of thermal barrier coating. Surface and Coatings Technology 2017, 313, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.-W.; et al. Conditions and mechanisms for the bonding of a molten ceramic droplet to a substrate after high-speed impact. Acta Materialia 2016, 119, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, Yan-pu, et al. “Remelting and bonding of deposited aluminum alloy droplets under different droplet and substrate temperatures in metal droplet deposition manufacture.” International Journal of Machine Tools and Manufacture 69 (2013): 38-47. [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.-W.; et al. Epitaxial growth during the rapid solidification of plasma-sprayed molten TiO2 splat. Acta Materialia 2017, 134, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampath, S.; et al. Substrate temperature effects on splat formation, microstructure development and properties of plasma sprayed coatings Part I: Case study for partially stabilized zirconia. Materials Science and Engineering: A 1999, 272, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukumoto, M.; et al. Splash splat to disk splat transition behavior in plasma-sprayed metallic materials. Journal of Thermal Spray Technology 2007, 16, 905–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, R.-Q.; Koshizuka, S.; Oka, Y. Two-dimensional simulation of drop deformation and breakup at around the critical Weber number. Nuclear Engineering and Design 2003, 225, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Dianat, M.; McGuirk, J.J. A robust interface method for drop formation and breakup simulation at high density ratio using an extrapolated liquid velocity. Computers & Fluids 2016, 136, 402–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nykteri, G.; Gavaises, M. Droplet aerobreakup under the shear-induced entrainment regime using a multiscale two-fluid approach. Physical Review Fluids 2021, 6, 084304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, R.K.; et al. Numerical study of pore formation in thermal spray coating process by investigating dynamics of air entrapment. Surface and Coatings Technology 2019, 378, 124972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; et al. Numerical analysis on air entrapment during a droplet impacts on a dry flat surface. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 2017, 115, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, M.; et al. “Observations of nanoporous foam arising from impact and rapid solidification of molten Ni droplets.” Applied Physics Letters 90.25 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Tran, A.T.T.; et al. Effects of surface chemistry on splat formation during plasma spraying. Journal of Thermal Spray Technology 2008, 17, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.-Z.; et al. Improvement of interfacial bonding between plasma-sprayed cast iron splat and aluminum substrate through preheating substrate. Surface and Coatings Technology 2017, 316, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; et al. Effect of substrate temperature on the microstructure and interface bonding formation of plasma sprayed Ni20Cr splat. Surface and Coatings Technology 2019, 371, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; et al. Interface structure, mechanics and corrosion resistance of nano-ceramic composite coated steels. Applied Surface Science 2024, 669, 160525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chantelot, P.; Lohse, D. Drop impact on superheated surfaces: from capillary dominance to nonlinear advection dominance. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2023, 963, A2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanet, G.; et al. “Transient evolution of the heat transfer and the vapor film thickness at the drop impact in the regime of film boiling.” Physics of Fluids 30.12 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.; et al. Drop impact on superheated surfaces. Physical Review Letters 2012, 108, 036101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, C.; Ikeda, I.; Sakaguchi, M. Recoil and solidification of a paraffin droplet impacted on a metal substrate: Numerical study and experimental verification. Journal of Fluids and Structures 2023, 118, 103839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.; Ikeda, I.; Sakaguchi, M. Spreading dynamics associated with transient solidification of a paraffin droplet impacting a solid surface. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 2024, 228, 125672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Splat material | Substrate material | Method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wax | Teflon, polyethylene | Tensile | [52] |

| ZnO nanorods on carbon fibers | Thermoplastic matrix | Scraping | [54] |

| Epoxy resin | Single carbon fiber | Scraping | [53] |

| Thermoplastic matrix | Single carbon fiber | Scraping | [54] |

| ZrO2-8 wt.%Y2O3 | CoNiCrAlY bond coat + nickel-base superalloy |

Scraping | [55] |

| Wax | 430 stainless steel | Scraping | [56] |

| ZrO2-8 wt.%Y2O3 | Stainless steel | Scraping | [57] |

| Al2O3 | Stainless steel 304 | Indentation | [59] |

| CoNiCrAlY | Ni-based superalloy | FIB-milled microcantilever beam bending |

[61] |

| Al2O3 | Ni-based superalloy | Scratch | [63] |

| Al2O3 with multiwall carbon nanotubes | Steel | Scratch | [64] |

| Al2O3, TiO2 | C20 steel | Scratch | [65] |

| Carbon nanofiller-reinforced Al2O3 | AISI 1020 steel | Scratch | [66] |

| Fe-based amorphous alloy | AISI 1045 steel | Scratch | [67] |

| Splat material | Substrate material | Method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mo | Steel, Al | XRD | [75] |

| Mo | Stainless steel | XRD | [76] |

| Mo | Stainless steel | XRD | [77] |

| Mo | Stainless steel 304 | XRD | [78] |

| YSZ | NiCrAlY bond coat + 316 stainless steel substrate |

Raman spectroscopy | [79] |

| Ni−5wt.%Al | Stainless steel | FIB–DIC material removal | [83] |

| Ni−5wt.%Al, Al2O3, (Al2O3−13wt.%TiO2)−8wt.%ZrO2−8wt.%CeO2 |

Ni−5wt.%Al bond coat + stainless steel substrate | HR-EBSD | [61] |

| Wax | Stainless steel 430 | Reverse calculation from strain | [89] |

| Wax | Stainless steel 430 | Reverse calculation from strain | [90] |

| Wax | Stainless steel 430 | Reverse calculation from strain | [91] |

| Splat material | Substrate material | Deformation | Method | Code | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | - | Elastic | Elastic model | - | [34] |

| Mo | Stainless steel 304 | Elastic | Elastic model with correction coefficients | - | [78] |

| YSZ | Steel alloy | Elastic–plastic | SPH-FEM | ABAQUS/Standard + ABAQUS/Explicit | [96] |

| Mo | Stainless steel 304 | Elastic | VOF + FEM | FLOW-3D + ABAQUS | [78] |

| Carbon steel | Carbon steel | Elastic, creep | FEM | ABAQUS | [93] |

| Al alloy, Bi | Steel | Elastic | FEM | ANSYS | [94] |

| YSZ | Stainless Steel | Elastic–plastic | FEM | ABAQUS/Explicit | [95] |

| Wax | Stainless steel 430 | Elastic | FEM | ABAQUS/Standard | [90] |

| Wax | Stainless steel 430 | Elastic, creep | FEM | ABAQUS/Standard | [91] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).